Abstract

The 2023/24 El Niño ranks as the second strongest event in the twenty-first century thus far. The event exhibited a two-step warming tendency and two warming centers, which could not be explained by the heat content buildup. Here, by conducting observational analysis and model experiments, we show that the record-breaking pantropical warming in 2023 mitigated this El Niño and confined the warming to the eastern basin, and that a series of westerly wind bursts induced another warming center in the central equatorial Pacific toward the end of 2023. Yet the effects of pantropical forcing and wind bursts coincidentally offset each other, leaving the heat content buildup appearing as the primary cause of the 2023/24 El Niño. Our results not only confirm the essential role of equatorial ocean heat recharge for El Niño development, but also demonstrate the necessity of accounting for multi-scale interactions from a global perspective to predict El Niño.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the strongest interannual variability on Earth and has widespread impacts on global climate1,2. After a rare 3-year long La Niña, the tropical Pacific experienced a strong warm episode in 2023. El Niño conditions were officially declared to be present on June 8, 20233. After a steady development during summer and autumn, the event reached the strong El Niño category in December4,5. Along with the growth of the event, its worldwide impacts have also emerged. For example, the global mean temperature increased synchronously with the growth of this El Niño after April (Supplementary Fig. 1)6, and the warming trend was expected to persist into 20247,8.

The strength of the 2023/24 El Niño event aligned with our forecast conducted in March 20239. The consistency between the prediction and observations stems from the fact that the upper ocean heat content (HC) in the western equatorial Pacific was exceptionally high in the early months of 20239, and that the intensity of accumulated HC may serve as a precursor for ENSO 6–9 months in advance10,11. However, the buildup of HC is neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition for predicting the actual evolution of a specific El Niño event12. Other processes in the global tropics, ranging from synoptic to interannual time scales, may considerably modulate the pattern and magnitude of El Niño13,14. At the synoptic time scale, the westerly wind bursts (WWBs) occurring in the western-central equatorial Pacific have been suggested to be crucial in regulating El Niño by altering surface advection and oceanic waves along the equator15,16,17,18. At the interannual time scale, intense anomalies of sea surface temperature (SST) across the tropics have been found to play a pronouncing role in boosting strong El Niño events through remote forcing19. It has been reported that the SST anomalies in many areas outside of the equatorial Pacific ranked near the top of historical highs in 2023, and that a few sizable WWBs were observed in the equatorial Pacific in boreal autumn5. The extreme HC buildup and pantropical SST warming, along with the considerable WWB activities observed in 2023, offer an unprecedented opportunity to assess the relative contributions of various factors to El Niño prediction.

Results

2023/24 El Niño and its early warning

At the beginning of 2023, a huge amount of anomalous warm water was piled up in the western equatorial Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 2). With the eastward propagation of oceanic Kelvin waves, along with forcing from intraseasonal westerly anomalies in the western equatorial Pacific and cyclonic disturbance off Peru in March20, a strong coastal El Niño emerged near the South American coast (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 3). Although this coastal El Niño cannot explain the intensity of the 2023/24 El Niño, as shown by multi-model experiments in a recent study, it did precondition a basin-wide warming21. The tight atmosphere-ocean coupling during El Niño22 guarantees the growth of the warm anomalies in the eastern equatorial Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, the warm SST anomalies did not propagate to the central equatorial Pacific as expected under the strong atmosphere-ocean interaction23, but were restricted to the eastern equatorial Pacific. By October, the eastern equatorial Pacific warming started to decay, while another relatively weaker warm center emerged in the central equatorial Pacific (Fig. 1a). The delayed warming over the central-eastern equatorial Pacific led to a steady increase of the NINO3.4 index (Fig. 2a), a widely used measure of ENSO intensity (Methods). The maximum was found in December, and the average from November 2023 to January 2024 was ~1.91 °C, meeting the criteria of a strong El Niño event4. From January 2024, the equatorial Pacific began to be prevailed by basin-wide easterly anomalies and upwelling waves5, both of which contributed to the demise of this El Niño event (Figs. 1a, 2a).

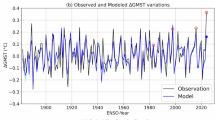

a Observations. b–d Experiments CESM-TP, CESM-TP + G, and CESM-TP + G + WWBs, respectively. For predictions, only values significant at the 95% confidence level are shown. Magenta line denotes March 1st, 2023 when prediction begins. Abbreviations: OBS observations, CESM Community Earth System Model, TP tropical Pacific, G global tropics, and WWBs westerly wind bursts. Unit is °C.

a–c Evolutions of NINO3.4 index in observations and experiments. Shading denotes one standard deviation among different ensemble members. Plotting style follows ENSO forecast released by the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current). d NINO3.4 index averaged from November 2023 to January 2024 (NDJ). Abbreviations: NETP northeastern tropical Pacific, SETP southeastern tropical Pacific, TIO tropical Indian Ocean, and TA tropical Atlantic. Unit is °C.

We predicted the upcoming of the 2023/24 El Niño using a state-of-the-art ENSO ensemble forecast system and the observational data up to February 20239. In that study, the forecast system was coupled only for the tropical Pacific and the high-frequency wind stress was largely truncated by an online low-pass filter18 during integration. As a result, the basic mechanism at work in our previous study9 was dictated by the classic ENSO theory, i.e., the low-frequency ocean-atmosphere interaction within the tropical Pacific24.

Here, we conduct a similar prediction, termed CESM-TP, in which atmosphere-ocean coupling is allowed only within the tropical Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 5a). To estimate possible influence from the WWBs observed in 2023, as will be shown later, high-frequency wind stress simulated by the model is not truncated in this study. However, since the intensity of model simulated WWBs are obviously weaker than observations (Supplementary Fig. 6), results from CESM-TP primarily reflect the influence from the initial HC buildup. As seen in Figs. 1b and 2a, the magnitude and general features of the 2023/24 El Niño are well predicted in CESM-TP, yet the spatial pattern of the prediction differs in detail from that observed. The discrepancy is presumably due to the fact that using HC buildup alone tends to predict a canonical El Niño in which surface warming spans the central-eastern equatorial Pacific17,25. The results suggest that the low-frequency coupling based solely on HC buildup, as used in our previous work9, cannot fully explain the underlying dynamics of the 2023/24 El Niño, and other factors outside of the equatorial Pacific at different time scales must have modulated the detailed structure of this El Niño.

Influence from outside of equatorial Pacific

The structure and magnitude of El Niño have been suggested to be considerably influenced by remote forcing caused by intense large-scale SST anomalies outside of the equatorial Pacific, mainly those in the northeastern tropical Pacific26,27,28,29,30, southeastern tropical Pacific31,32,33,34, tropical Indian Ocean35,36,37,38, and tropical Atlantic39,40,41,42. A set of pacemaker experiments is conducted to explore the extent to which SST anomalies in these areas influence the characteristics of the 2023/24 El Niño. Because this El Niño peaked in December, the pacemaker experiments are conducted by restoring model-simulated SST anomalies in specified areas from March to November 2023 to the observations while keeping other settings the same as CESM-TP (Supplementary Fig. 5). The difference between the pacemaker experiments and CESM-TP thus reflects the influence from SST anomalies in the specified areas to the 2023/24 El Niño.

We begin by analyzing the impact of SST anomalies in the northeastern tropical Pacific. Warm anomalies in this area have been found acting as a trigger and a maintainer of an El Niño, presumably through generating warm advection by westerly anomalies in the equatorial central Pacific26,29,30 and charging the off-equatorial subsurface temperature by westerly anomalies in the northeastern tropical Pacific28. While the averaged SST anomalies in the northeastern tropical Pacific in 2023 were close to zero (Fig. 3c), positive anomalies were observed from July to November (Fig. 3b). When SST anomalies in this area are used to force the model, termed CESM-TP + NETP, surface winds over the equatorial Pacific do not change significantly compared to CESM-TP (Supplementary Figs. 7a, 8a). However, a strong cyclonic circulation, along with significant upward motion and heavy precipitation, is induced north of the eastern equatorial Pacific (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Figs. 9a, 10a). Although these off-equatorial westerly anomalies do not influence the heat flux in the equatorial central-eastern Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 11a), they substantially increase subsurface temperature via the trade wind charging mechanism (Supplementary Figs. 12a, 13a). As a result, a stronger El Niño slightly exceeding the threshold of an extreme event4 is induced (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Figs. 14a, 15a), although the enhancement is not significant (Supplementary Fig. 16).

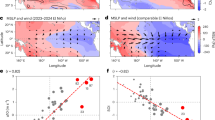

a SST (shading, unit of °C) and surface wind (vector, unit of m s−1) anomalies averaged from March to November 2023. Medium purple, blue violet, magenta, and dark cyan areas denote the northeastern tropical Pacific, southeastern tropical Pacific, tropical Indian Ocean, and tropical Atlantic, respectively. b Monthly evolution of regional averaged SST anomalies. c–f Yearly evolution of SST anomalies averaged from March to November. Texts in c-f indicate the ranking of SST anomalies in 2023 since 1979. Unit is °C.

Next, we examine the influence from the southeastern tropical Pacific. The SST anomalies in this area exhibited considerable warm anomalies in the early months of 2023 (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 3), with the average from March to November ranking as the 3rd warmest year in history (Fig. 3d). When the prediction system is forced by the SST anomalies observed in this area in 2023, termed CESM-TP + SETP, a much-intensified El Niño reaching the extreme category is generated (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Figs. 14b, 15b), yet the intensity is also not significantly different from that in CESM-TP (Supplementary Fig. 16). The heat budget analysis of the mixed-layer temperature anomaly indicates that the enhanced El Niño is mainly due to the eastward warm zonal advection (Supplementary Fig. 13b), which is further associated with equatorial westerly anomalies from October to December in CESM-TP + SETP (Supplementary Fig. 8b). It is worth noting that since the area where the strong 2023 coastal El Niño occurs is not included in this pacemaker experiment, the results from CESM-TP + SETP do not necessarily imply that the 2023 coastal El Niño played a trivial role in the 2023/24 El Niño21.

After analyzing the impacts of SST anomalies straddling the central-eastern equatorial Pacific, we proceed to examine the influence from the tropical Indian Ocean. It has been suggested that while a basin-wide warming in the tropical Indian Ocean tends to diminish El Niño by inducing easterly anomalies in the equatorial Pacific35,36,43, a dipole-like structure of SST anomalies, characterized by a warm center in the western and a cold center in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean44, generally enhances El Niño through intensifying the Walker Circulation38. In 2023, the tropical Indian Ocean exhibited strong basin-wide warm SST anomalies ranked as the historical high (Fig. 3e). When they are utilized to force the prediction system, termed CESM-TP + TIO, significant surface easterly anomalies in the western-central equatorial Pacific are found (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Fig. 8c). While these easterly anomalies do not significantly alter the Pacific Walker circulation and Hadley circulation (Supplementary Figs. 7c, 10c), they induce strong upwelling along the equatorial thermocline (Supplementary Fig. 12c). The associated cold surface advection and thermocline feedback contribute to a much-reduced El Niño (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 13c), especially after June when warm anomalies in the tropical Indian Ocean were strong (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Figs. 14c, 15c). This result differs from the prediction based on an idealized global ENSO model which indicated that the tropical Indian Ocean positively contributed to the 2023/24 El Niño45, presumably due to the underestimation of basin-wide warm SST anomalies in that study. It should be also noted that while a dipole-like pattern was observed in fall (Supplementary Fig. 3), it had minimal influence on the prediction, likely due to its late appearance and limited size in the eastern basin37.

The influence from the tropical Atlantic is then explored. Warm anomalies in the tropical Atlantic impact the El Niño mainly in two ways. Firstly, when warmings are within the equatorial Atlantic, they induce anomalous ascending motions over the Atlantic and anomalous descending motions over the central Pacific, resulting in an enhanced Walker Circulation over the western-central equatorial Pacific40. Secondly, when warmings are located in the North tropical Atlantic, they strengthen the trade winds in the western-central equatorial Pacific through triggering an anti-cyclonic large-scale circulation in the northern tropical Pacific41. In both cases, an El Niño is expected to be weakened by the anomalies easterlies in the western-central equatorial Pacific, and the warming should be confined to the eastern basin due to the anomalous westerlies in the eastern equatorial Pacific. The SST anomalies in the tropical Atlantic soared to record heights in 2023 (Fig. 3f), with the strength much greater than those in the southeastern tropical Pacific and the tropical Indian Ocean (Fig. 3b). When they are used to force the model, termed CESM-TP + TA, a Rossby-wave response in precipitation is found, manifested by stronger changes west of the tropical Atlantic compared to the east (Supplementary Fig. 9). The Pacific Walker and Hadley circulations are both strengthened (Supplementary Figs. 7d, 10d). The associated surface easterly anomalies not only induce latent heat flux lost from the equatorial Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 11d), but also lead to significant upwelling along the equatorial thermocline (Supplementary Fig. 12d). These two negative impacts, along with cold surface advection, contribute to the reduced SST anomalies in the central-eastern equatorial Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 13d). Accordingly, warm SST anomalies are confined to the eastern equatorial Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 15d), and the predicted El Niño is suppressed significantly even to the weak category4 (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Figs. 14d, 16).

Finally, we present the results from CESM-TP + G, where the observed SST anomalies in the aforementioned four areas outside of the eastern equatorial Pacific are utilized to force the model. The predicted NINO3.4 index in this experiment does not show the distinct peak observed in December and falls into the moderate category4 (Fig. 2b). In addition, strong warm SST anomalies are confined to the eastern equatorial Pacific (Fig. 1c), primarily attributed to the intense equatorial easterly anomalies forced by warming in the tropical Indian Ocean and Atlantic (Fig. 4e). The intense easterly anomalies also kindly explain why zonal wind stress simulated in CESM-TP, which excludes the impacts from outside of the equatorial Pacific, is systemically stronger than that seen in the observations before August (Supplementary Fig. 4). Note that even for CESM-TP + G, zonal wind stresses in the central equatorial Pacific area are still stronger than those in observations, implying that the model is likely to predict a stronger El Niño due to the systematic bias in simulating surface westerlies. Regardless of this difference, these model experiments suggest that while the SST anomalies straddling the eastern equatorial Pacific tended to enhance the 2023/24 El Niño, the extreme surface warmings in the tropical Indian Ocean and Atlantic caused a much-stronger cooling effect, resulting in a moderate El Niño characterized by a single warm center confined to the eastern Pacific.

Delayed warming caused by WWBs in fall

While predictions may suffer from the mean state biases and systematic errors, the distinct difference between the 2023/24 El Niño seen in observations and predicted in CESM-TP + G implies that processes other than pantropical SST forcing must be invoked in reality. The most likely candidate is the WWBs in the western-central equatorial Pacific, which benefit the equatorial Pacific warming significantly by triggering eastward warm advection and downwelling Kelvin waves16,17. A few sizable WWBs were observed in the western-central Pacific in 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 6), mainly in fall when the relatively weak warm center was found in the central equatorial Pacific (Fig. 1a). In contrast, WWB activities are severely underestimated in CESM-TP and CESM-TP + G (Supplementary Fig. 6). Two additional pacemaker experiments are conducted to assess how the WWBs observed in 2023 influences the 2023/24 El Niño (“Methods”).

Firstly, we add the WWB that observed in mid-May to CESM-TP + G. The prediction from this model setup, termed CESM-TP + G + WWB1, demonstrates that the May WWB barely influences the overall structure of the El Niño predicted without it (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Figs. 14e, 15e), presumably due to its moderate strength and transient impacts on ocean current and thermocline depth (Supplementary Figs. 17a, 18a). Then, we add WWBs that occurred in October, and November 2023 to CESM-TP + G. In this case, termed CESM-TP + G + WWB2, a suite of strong downwelling Kelvin waves along with eastward warm currents is excited in fall, followed by significant SST warming near the equatorial dateline (Supplementary Figs. 17b, 18b). The mechanism echoes the eastward stepwise expansion of the warm pool in response to surface westerlies proposed in previous studies46,47. When all the WWBs mentioned above are added to CESM-TP + G, termed CESM-TP + G + WWBs, the predicted El Niño is readjusted to align with the observations and that simulated in CESM-TP (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Figs. 17c, 18c), with the weak warming in the central equatorial Pacific from October to December well simulated (Fig. 1d). It’s clear that the delayed central Pacific warming, which was dynamically distinct from the eastern Pacific warming, prolonged the 2023/24 El Niño and contributed to the high consistencies in category, spatial pattern, and overall evolution of the 2023/24 strong El Niño between observations and CESM-TP + G + WWBs.

Discussion

The analyses presented here reveal that the 2023/24 strong El Niño was mainly contributed to by three factors. Firstly, the buildup of HC in the western equatorial Pacific in spring 2023 preconditioned a strong traditional El Niño, characterized by homogenous SST warming across the central-eastern equatorial Pacific, peaking toward the end of 2023. Secondly, the strong positive SST anomalies outside of the equatorial Pacific mitigated the equatorial Pacific warming and confined the El Niño to the eastern basin. Finally, the WWBs that occurred in the western-central equatorial Pacific in autumn caused another relatively weak warm center in the central equatorial Pacific in late 2023. Yet the latter two factors coincidentally offset each other, leaving the HC buildup appearing as the primary cause of the strong 2023/24 El Niño. Our results not only confirm that the equatorial ocean heat recharge is essential for El Niño growth, but also demonstrate that the multi-scale interactions from a global perspective should be taken into the account to understand and predict El Niño accurately45. The dependence of El Niño predictions on pantropical ocean and atmospheric conditions also highlights the importance of establishing and maintaining international projects for ocean observing developed by the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS)48 to achieve better observational data for climate research.

Methods

Data

The SST, wind, precipitation, and sea level pressure are obtained from the fifth generation European Centre for Medium–Range Weather Forecasts reanalysis (ERA5) covering the period from 1979 to present49, with a resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° (https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5). The ocean temperature and surface height utilized are from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS) reanalysis50, available since 1980 with a resolution of 0.33° × 1.0° (http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.godas.html). Simulations from 37 climate models involved in the 6th generation of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6)51 under the historical scenario in period 1900 to 2014 are also used (https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/).

Index and statistics

Anomalies are obtained by removing climatological seasonal cycle based on period 1980–2019. The NINO3.4 index is the regional averaged SST anomalies in the area spanning (170°W–120°W, 5°S-5°N). A WWB event in observations is defined as a westerly wind gust with a maximum zonal wind stress anomaly exceeding a threshold of 0.05 N m−2, a zonal extent of at least 10 degrees, and a duration of at least 2 days52,53,54. Because the anomalous zonal wind stress during the 2023/24 El Niño simulated in model experiments is systematically different from that in the observations (Supplementary Fig. 4), model-simulated WWBs identified based on a fixed threshold of strength could be strongly influenced by the systematic bias. To this end, we first subtract a 30-day running mean from the zonal wind stress simulated in models, and then apply the criteria used in observations to identify WWBs simulated in models.

For composite analysis, a value is deemed significant from zero if it reaches the 95% confidence level using the two tailed Student’s t-test. The regression coefficients used in this study are the two-sided Pearson correlation coefficients.

Heat budget analysis

The mixed-layer heat budget analysis is expressed as follows55,56:

where T denotes the mixed-layer temperature. \({Q}_{n{et}}\) represents the net surface heat flux, with positive values denoting downward flux into the ocean. The seawater density \(\rho\) is set to 1025 kg m−3, and the specific heat capacity of seawater at constant pressure \({c}_{p}\) is taken as 3940 J kg−1 °C−1. H is the monthly mixed-layer depth, defined as the depth at which the local buoyancy gradient reaches a maximum between the surface and any discrete depth57,58. u and v denote the zonal and meridional velocities averaged in the mixed-layer, respectively. Positive and negative value of \({w}_{H}+\frac{dH}{dt}\) denotes the entrainment and detrainment velocity, respectively. Only the entrainment velocities are used to calculate heat budget, as detrainment does not affect the mixed-layer temperature. \({T}_{H}\) represents the ocean temperature 5 meters below the mixed-layer depth. The first four terms on the right hand side denote heat flux (Qnet), zonal advection (Adv-u), meridional advection (Adv-v), and vertical advection (Adv-w), respectively. R denotes the residual term.

Model experiments

The ENSO ensemble prediction system employed in this study comprises the Community Earth System Model (CESM)59 and a data assimilation system. Compared to most of CMIP6 models, CESM performs well in simulating the climatological SST in the tropical Pacific, as well as the basic characteristics of ENSO such as variability, spatial pattern, and the Bjerknes feedback (Supplementary Figs. 19–22). The data assimilation system assimilates wind below 500 hPa and the ocean temperature in the upper 500 m provided by the ERA5 and GODAS datasets, respectively60. Random linear combinations of the first three leading relevant singular vectors61 of ocean temperature in the upper 200 m are utilized to generate 10 ensemble members, which are used to assess the influence of uncertainty in the upper ocean temperature on ENSO prediction. The ensemble prediction system predictes an El Niño with intensity close to observations when initialized in March 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 23). However, SST anomalies outside of the equatorial Pacific are not well reproduced. In particular, the model completely overlooks the record-breaking warm SST anomalies in the tropical Indian Ocean.

In CESM-TP, SSTs outside of the tropical Pacific are replaced by model climatology, and SSTs within the tropical Pacific are calculated by the model. This approach enables the truncation of remote forcing stemming from SST anomalies outside of the tropical Pacific. In CESM-TP + NETP, SSTs in the northeastern tropical Pacific are replaced by model climatology plus the observed SST anomalies from March to November, while SSTs elsewhere in the tropical Pacific are calculated by the model. Outside of these two areas, SSTs are replaced by model climatology during integration (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Similarly, we carry out CESM-TP + SETP, CESM-TP + TIO, and CESM-TP + TA. Abbreviated names used in model experiments include: TP (tropical Pacific), NETP (northeastern tropical Pacific), SETP (southeastern tropical Pacific), TIO (tropical Indian Ocean), and TA (tropical Atlantic). Their corresponding areas are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 5.

In CESM-TP + G run, SST anomalies in the northeastern tropical Pacific, southeastern tropical Pacific, tropical Indian Ocean, and tropical Atlantic are restored to the observations, and SSTs outside of the tropical Pacific are replaced by model climatology. In CESM-TP + G + WWB1, zonal wind stress associated with the WWB observed in May 2023 are added to model while keeping other settings the same as CESM-TP + G. CESM-TP + G + WWB2 is the same as and CESM-TP + G + WWB1, except that zonal wind stress associated with the WWBs observed in October, and November 2023 are added. In CESM-TP + G + WWBs, WWBs observed in May, October, and November 2023 are added to CESM-TP + G.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available online. The ERA5 data are available at https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5. The NECP GODAS reanalysis data are available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.godas.html. The CMIP6 data are available at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/. All these URL addresses are also listed in the Methods section. Datasets for the results are available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13952338.

Code availability

The analyses were performed using MATLAB (R2023a). The CESM source codes are publicly available at https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/releases. Codes for the results are available on GitHub at https://github.com/HRKsince1993/COMMSENV-24-1347.git.

References

Sarachik, E. S. & Cane, M. A. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation Phenomenon, Cambridge University Press, London, 384 (2010).

McPhaden, M. J., Santoso, A. & Cai, W. El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate. Wiley 528 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119548164 (2020).

A brief report released by the NOAA Climate Prediction Center declaring the 2023/24 El Niño conditions on June 8, https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_disc_jun2023/ensodisc.shtml (2023).

A reference defining ENSO strength category (https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/Niño-sst-indices-Niño-12-3-34-4-oni-and-tni).

A brief report of global ocean monitoring by the Climate Prediction Center, NCEP/NOAA released on February 9, https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/GODAS/ocean_briefing_gif/global_ocean_monitoring_2024_02.ppt (2024).

Li, K. et al. Record-breaking global temperature and crises with strong El Niño in 2023–2024. Innov. Geosci. 1, 100030 (2023).

A news from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) excepting the 2023/24 El Niño to fuel global temperature increases in 2024. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/el-Niño-expected-last-least-until-april-2024 (2023).

Jiang, N. et al. Enhanced risk of record-breaking regional temperatures during the 2023–24 El Niño. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–10 (2024).

Lian, T., Wang, J., Chen, D., Liu, T. & Wang, D. A strong 2023/24 El Niño is staged by tropical Pacific Ocean heat content buildup. Ocean-Land-Atmos. Res. 2, 0011 (2023).

Meinen, C. S. & McPhaden, M. J. Observations of warm water volume changes in the equatorial Pacific and their relationship to El Niño and La Niña. J. Clim. 13, 3551–3559 (2000).

Ramesh, N. & Murtugudde, R. All flavours of El Niño have similar early subsurface origins. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 42–46 (2013).

McPhaden, M. J. Playing hide and seek with El Niño. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 791–795 (2015).

Timmermann, A. et al. El Niño–Southern Oscillation complexity. Nature 559, 535–545 (2018).

Cai, W. et al. Pantropical climate interactions. Science 363, eaav 4236 (2019).

Harrison, D. E. & Vecchi, G. A. Westerly wind events in the tropical Pacific, 1986–95. J. Clim. 10, 3131–3156 (1997).

McPhaden, M. J. Climate oscillations: genesis and evolution of the 1997–98 El Niño. Science 283, 950–954 (1999).

Chen, D. et al. Strong influence of westerly wind bursts on El Niño diversity. Nat. Geosci. 8, 339–345 (2015).

Lian, T. & Chen, D. The essential role of early-spring westerly wind burst in generating the centennial extreme 1997/98 El Niño. J. Clim. 34, 8377–8388 (2021).

Wang, J. & Wang, C. Joint Boost to Super El Niño from the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. J. Clim. 34, 4937–4954 (2021).

Peng, Q. et al. The 2023 extreme coastal El Niño: atmospheric and air-sea coupling mechanisms. Sci. Adv. 10, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adk8646 (2024).

Tan, W. et al. On the divergent evolution of ENSO after the coastal El Niños in 2017 and 2023. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL108198 (2024).

Bjerknes, J. Atmospheric teleconnections from the equatorial Pacific. Mon. Wea. Rev. 97, 163–172 (1969).

Fedorov, A. & Philander, S. G. H. Is El Niño changing? Science 288, 1997–2002 (2000).

Jin, F. F. An equatorial ocean recharge paradigm for ENSO. Part I: conceptual model. J. Atmos. Sci. 54, 811–829 (1997).

Chen, D., Cane, M. A., Kaplan, A., Zebiak, S. & Huang, D. Predictability of El Niño over the past 148 years. Nature 428, 733–736 (2004).

Vimont, D. J., Wallace, J. M. & Battisti, D. S. The seasonal footprinting mechanism in the Pacific: implications for ENSO. J. Clim. 16, 2668–2675 (2003).

Chang, P. et al. Pacific meridional mode and El Niño - Southern Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, 1–5 (2007).

Anderson, B. T., Perez, R. C. & Karspeck, A. Triggering of El Niño onset through trade wind-induced charging of the equatorial Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1212–1216 (2013).

Amaya, D. J. et al. The North Pacific pacemaker effect on historical ENSO and its mechanisms. J. Clim. 32, 7643–7661 (2019).

Chu, Q., Lian, T., Hu, R., Feng, G. & Chen, D. The Pacific Meridional Mode influences ENSO by inducing spring-time near-equatorial TCs in the western North Pacific. J. Clim. 36, 7549–7561 (2023).

Min, Q., Su, J., Zhang, R. & Rong, X. What hindered the El Niño pattern in 2014? Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 6762–6770 (2015).

Imada, Y., Tatebe, H., Watanabe, M., Ishii, M. & Kimoto, M. South Pacific influence on the termination of El Niño in 2014. Sci. Rep. 6, 30341 (2016).

Zhu, J. et al. The role of off-equatorial surface temperature anomalies in the 2014 El Niño prediction. Sci. Rep. 6, 19677 (2016).

Hu, S. & Fedorov, A. V. Exceptionally strong easterly wind burst stalling El Niño of 2014. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 2005–2010 (2016).

Kug, J.-S. & Kang, I.-S. Interactive feedback between ENSO and the Indian Ocean. J. Clim. 19, 1784–1801 (2006).

Ohba, M. & Ueda, H. An impact of SST anomalies in the Indian Ocean in acceleration of the El Niño to La Niña transition. J. Meteor. Soc. Jap. 85, 335–348 (2007).

Annamalai, H., Kida, S. & Hafner, J. Potential impact of the tropical Indian Ocean–Indonesian Seas on El Niño characteristics. J. Clim. 23, 3933–3952 (2010).

Lian, T., Chen, D., Tang, Y. & Jin, B. A theoretical investigation of the tropical Indo-Pacific tripole mode. Sci. China Earth Sci. 57, 174–188 (2014).

Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. et al. Are Atlantic Niños enhancing Pacific ENSO events in recent decades? Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L20705 (2009).

Ding, H., Keenlyside, N. S. & Latif, M. Impact of the equatorial Atlantic on the El Niño Southern Oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 38, 1965–1972 (2012).

Ham, Y.-G. et al. Sea surface temperature in the north tropical Atlantic as a trigger for El Niño/Southern Oscillation events. Nat. Geosci. 6, 112–116 (2013).

Polo, M., Martin-Rey, M., Rodriguez-Fonseca, B., Kucharski, F. & Mechoso, C. R. Processes in the Pacific La Niña onset triggered by the Atlantic Niño. Clim. Dyn. 44, 115–131 (2015).

Dong, L. & McPhaden, M. J. Unusually warm Indian Ocean sea surface temperatures help to arrest development of El Niño in 2014. Sci. Rep. 8, 2249 (2018).

Saji, N. H., Goswami, B. N., Vinayachandran, P. N. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the tropical Indian Ocean. Nature 401, 360–363 (1999).

Zhao, S. et al. Explainable El Niño predictability from climate mode interactions. Nature 630, 891–898 (2024).

Kessler, W. S., McPhaden, M. J. & Weickmann, K. M. Forcing of intraseasonal Kelvin Waves in the equatorial Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 10,613–10,631 (1995).

Shin, N., Kug, J., McCormack, F. S. & Holbrook, N. J. The double-peaked El Niño and its physical processes. J. Clim. 34, 1291–1303 (2021).

WMO. Implementation plan for the global observing system for climate in support of the UNFCCC. WMO Tech. Doc. WMO/TD-1219, GCOS-92, 145 (2004).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Saha, S. N. et al. The NCEP climate forecast system. J. Clim. 19, 3483–3517 (2006).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the coupled model intercomparison project phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Seiki, A. & Takayabu, Y. N. Westerly wind bursts and their relationship with intraseasonal variability and ENSO. Part I: Statistics. Mon. Wea. Rev. 135, 3325–3345 (2007).

Puy, M., Vialard, J., Lengaigne, M. & Guilyardi, E. Modulation of equatorial Pacific westerly/easterly wind events by the Madden–Julian oscillation and convectively-coupled Rossby waves. Clim. Dyn. 46, 2155–2178 (2016).

Chiodi, A. M. & Harrison, D. E. Observed El Niño SSTA development and the effects of easterly and westerly wind events in 2014/15. J. Clim. 30, 1505–1519 (2017).

Stevenson, J. W. & Niiler, P. P. Upper ocean heat budget during the Hawaii-to-Tahiti shuttle experiment. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 13, 1894–1907 (1983).

Kim, S. B., Lee, T. & Fukumori, I. Mechanisms controlling the interannual variation of mixed layer temperature averaged over the Niño-3 region. J. Clim. 20, 3822–3843 (2007).

Large, W. G., Danabasoglu, G., Doney, S. C. & Mcwilliams, J. C. Sensitivity to surface forcing and boundary layer mixing in a global ocean model: annual-mean climatology. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 27, 2418–2447 (1997).

Smith, R. & Coauthors: The parallel ocean program (POP) reference manual ocean component of the community climate system model (CCSM) and community earth system model (CESM). [Available online at https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/cesm1.0/pop2/] (2010).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The Community Earth System Model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Song, X. S. et al. A new nudging scheme for the current operational climate prediction system of the National Marine Environmental Forecasting Center of China. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 41, 51–64 (2022).

Kleeman, R., Tang, Y. & Moore, A. The calculation of climatically relevant singular vectors in the presence of weather noise. J. Atmos. Sci. 60, 2856–2868 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFF0805300), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42227901, 42376014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. Hu analyzed the data and conducted the model experiments. T. Lian conceived the study, supervised the work, and wrote the manuscript. T. Liu, J. Wang and X. Song contributed to interpreting the results. H. Chen provided the CMIP6 data. D. Chen jointly supervised the work and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, R., Lian, T., Liu, T. et al. Predicting the 2023/24 El Niño from a multi-scale and global perspective. Commun Earth Environ 5, 675 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01867-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01867-w

This article is cited by

-

The 2023/24 El Niño event exhibited unusually weak extratropical teleconnections

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Atypical warming pattern of strong 2023-24 El Niño boosts global temperatures to new 1.5 °C record

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Emergent multiscale dynamics in photonic neurons with dual feedback

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Toward skillful forecasting of super El Niño events using a diffusion-based westerly wind burst parameterization

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Strong 2023–2024 El Niño generated by ocean dynamics

Nature Geoscience (2025)