Abstract

Accurate estimation of terrestrial ecosystem respiration (TER) is essential for refining global carbon budgets. Current large-scale TER models rely on empirical structures derived from site-scale observations, often driven solely by hydrothermal factors. However, incorporating ecosystem-scale information is critical for more accurate large-scale TER modeling. Such ecosystem-scale variables have not been well parameterized, since the mechanisms by which they affect TER remain unclear. To address this gap, here we developed a Causality constrained Interpretable Machine Learning model for TER estimation (named “CIML-TER”) which consider the ecosystem-scale information. CIML-TER exhibited higher estimation accuracy (reducing relative mean absolute error by approximately 15%) and overcame the “artificial discontinuities” phenomenon of traditional models. Meanwhile, we quantitatively revealed that although environmental factors, such as temperature and water, were still the dominant drivers of TER (contributing ~44.15% of global TER variability), biotic factors (e.g., vegetation structure, ~25.91%) and spatiotemporal variation factors (e.g., land cover and phenology, ~29.94%) were also critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Terrestrial ecosystem respiration (TER) was the primary carbon flux from terrestrial ecosystems to the atmosphere, including autotrophic respiration by plants and heterotrophic respiration from decomposition by soil organisms1,2. Fluctuations in TER can alter net carbon exchange processes, subsequently affecting the effectiveness of carbon sequestration3. Therefore, accurately quantifying the dynamics of global TER is crucial for understanding the impacts of climate change on terrestrial carbon balance4,5, which can further inform policy development and help the implementation of nature-based solutions6,7.

The terrestrial ecosystem respiration estimation models can be roughly divided into three main categories8,9: semi-empirical models, pure empirical models, and machine learning models. (1) Semi-empirical models take the relationships between respiration rates and temperature as the core, such as the Q1010,11, Lloyd & Taylor12 and Arrhenius13 models. These models are the most widely used tools for TER estimation, and can independently estimate TER from site to global scales, or be integrated as respiration modules within process models, like Community Land Model (CLM) and Breathing Earth System Simulator (BESS)14,15,16. Although their exponential-like functions are derived from thermodynamic theories (van’t Hoff equation), their parameters require recalibration to improve estimation accuracy in practical applications, hence being semi-empirical. (2) Pure empirical models are established on the several variables related to TER, often focusing on a single factor like soil moisture, gross primary productivity, or vegetation indices17,18,19. These models employ various functional forms (e.g., linear, quadratic or logistic), since the relationship to TER is different across variables. Recently, Tagesson et al.5 developed a LGS-Reco product by applying the most suitable empirical model for each pixel to generate global TER estimates. (3) Machine learning methods can be used to optimize traditional models’ parameters or directly estimate TER. For instance, Lu et al. 20 modified the traditional Lloyd & Taylor model by incorporating vegetation indices and employed machine learning techniques to optimize its parameters. Alternatively, machine learning methods can also be used to model complex, nonlinear relationships between multiple input data and TER, directly generating global TER estimates21,22,23,24, such as the Random Forest (RF) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) methods. However, machine learning models are often criticized for lacking physical mechanisms, and their long-term variability can be sensitive to variable selection and model design5.

Ecosystem respiration involves complex interactions between physical and biochemical factors, with the autotrophic and heterotrophic components of TER responding distinctly to ecosystem properties and environmental variables. Consequently, the mechanisms underlying TER exhibit significant regional variability, contributing to large uncertainties in existing estimation methods25. The mainstream TER models, which are fundamentally based on temperature response functions, only incorporate temperature and moisture as driving factors8,16,26. These models are essentially upscaled applications of site- or single-component observational experience12,27. Their parameters require recalibration with flux observations across regions (or plant functional types) to minimize errors for large-scale applications11. However, it is increasingly evident that ecosystem-scale TER estimation must account for additional factors beyond hydrothermal variables, such as non-photosynthetic vegetation cover and the spatial distribution of leaves. These ecosystem-scale information are crucial, since they are related to light transformation processes (e.g., the daytime inhibition of TER) and detailed descriptions of vegetation components (e.g., green and senescent leaves), which can ultimately influence the ecosystem-scale carbon budget28,29,30. However, it remains a challenge to parameterize such ecosystem-scale information into TER models. This difficulty arises from the limited availability of in situ observations about ecosystem properties and the incomplete understanding of how the ecosystem-scale drivers affect TER. While some process models, like Terrestrial Carbon Flux (TCF) and Forest Ecosystem Carbon Budget Model for China (FORCCHN), attempted to address this issue by separately calculating each component’s respiration rates31,32, they highly relied on some simplified assumptions to partition carbon pools. Specifically, they roughly set the ecosystem background (e.g., allocation strategies, tree spacing) based solely on leaf area index (LAI) and coarse discrete land classification data, which cannot fully capture the heterogeneity and the continuous variations of natural ecosystems.

Recently, the interpretable machine learning (IML) framework is expected to facilitate the fusion of such ecosystem-scale information and help to clarify the relationships between ecosystem-scale variables and TER, thereby contributing to the development of process models. For instance, the combination of tree-based models (e.g., eXtreme Gradient Boosting, also called XGBoost33) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) tools34. XGBoost is particularly effective in capturing complex, non-linear relationships within tabular data and has been proven to outperform deep learning models in these contexts35. Moreover, SHAP has a solid theoretical foundation in game theory and can ensure that the global interpretations of model are consistent with the local explanations of samples36. These IML frameworks have been widely used in geographical sciences, especially in attribution analyses37,38,39. For example, researchers have employed XGBoost to investigate the relationships between environmental factors and vegetation greenness, and applied SHAP to interpret the influence and variability of contributing factors over time and space39. Moreover, incorporating causal constraints into training processes can enhance both the interpretability and accuracy of machine learning models. For instance, Yuan et al.40 applied causal information, derived from the PCMCI method41,42, as prior references to modify the weights of model parameters during training process. Their approach improved the estimates of wetland methane emissions43, revealing the underestimated response of methane emission to temperature in previous research. In summary, it is expected to improve the TER estimation accuracy by applying the Causality constrained Interpretable Machine Learning (CIML) framework, which can not only enhance model accuracy but also provide insights into the sensitivity and spatiotemporal variability of ecosystem properties’ effect on TER.

Therefore, this study aims to improve global TER estimation accuracy and deepen the understanding of its spatiotemporal variations by incorporating crucial ecosystem-scale information (e.g., clumping index, non-photosynthetic vegetation cover and phenology) into model construction. Following the causality constrained interpretable machine learning framework, we established a satellite-based TER model called “CIML-TER” and used it to elucidate the effect of various driving factors on large-scale TER estimation, consequently revealing their regional differences. These insights are expected to inform and support future developments of TER process models.

Results

Model construction and estimation accuracy

The Causality constrained Interpretable Machine Learning model for Terrestrial Ecosystem Respiration estimation (CIML-TER; all the abbreviation can refer to Supplementary Table 1) was established based on the XGBoost framework which was constrained by the causal effects derived from PCMCI+. By systematically synthesizing the previous research about TER estimation, we divided the relevant variables into three groups (Supplementary Fig. 1) for model construction: environmental conditions, biotic factors (e.g., vegetation structure) and spatiotemporal variations (e.g., differences in phenology and land cover). Specifically, we firstly ran the PCMCI+ method on site-scale datasets (see “Site data”) and got the causal effect of each input variable on TER. Secondly, these causal effects were used as reference weights to guide the tree generation process of XGBoost model (see more details in “Modelling TER” and Supplementary Fig. 2). Thirdly, we ran the CIML-TER model globally (monthly, 2001–2020, 0.05°) and concurrently evaluated its estimation accuracy with two other mainstream TER products (Fluxcom and LGS-Reco, see “Other TER products” and “Model evaluation”). Finally, we used the SHAP tool to interpret the relationships between input variables and TER inside, including variables’ feature importance and corresponding regional differences, as well as their sensitivity.

CIML-TER performed well in the accuracy evaluation experiment, with higher R2 and lower Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in both FLUXNET and ABCflux datasets. Since the final estimates of CIML-TER were the mean of all folds’ outputs, thus partial estimates were derived from the training data, resulting in that the overall performance was obviously better than that of the test set (Fig. 1a, b, the overall and test set MAE were 13.359 and 24.051 g C·m−2·month−1, respectively). Notably, the Fluxcom product similarly relies on partial site data for model training, and the LGS-Reco product also requires partial site data to determine empirical model coefficients. Therefore, this can be considered as a relatively fair comparison among three TER products (Fig. 1a, c, d). Specifically, CIML-TER outperformed Fluxcom and LGS-Reco products in terms of accuracy and mitigated the issue of “high-value underestimation”, showing a slope more closed to 1 (Fig. 1a, c, d). Additionally, CIML-TER obviously improved the TER estimation accuracy in the high latitudes of northern hemisphere. Specifically, the CIML-TER MAE on the test set was 17.308 g C·m−2·month−1, whereas the overall MAE of Fluxcom and LGS-Reco were 19.658 and 22.068 g C·m−2·month−1, respectively. In other words, the model performance of Fluxcom and LGS-Reco (red color in Fig. 1c, d) were even worse than the lower bound of CIML-TER (red color in Fig. 1b) in high-latitude regions. Meanwhile, this result also showed that CIML-TER can achieve acceptable accuracy when even applied in regions with totally spatiotemporal heterogeneity (Fig. 1b), exhibiting a relatively higher generalization ability.

a The overall performance of causal XGBoost model; b the performance of causal XGBoost model on test dataset; c the overall performance of Fluxcom product; d the overall performance of LGS-Reco product. The gray points mean the monthly TER estimation for all site-month samples, and the solid gray lines are corresponding regression lines. The colored points with black outlines are averaged results of each site, in which the blue and red parts represent FLUXNET and ABCflux, respectively. The dashed black lines show the 1:1 relationship.

CIML-TER generally achieved superior accuracy across all vegetation types. Specifically, CIML-TER exhibited higher R2 and lower MAE, rMAE in all vegetation types (Fig. 2), except for CSH.CIML-TER particularly improved the estimation accuracy of TER in forest types. For example, the rMAE of CIML-TER in EBF was approximately 10%, representing a reduction of ~20% (~40 g·C·m−2·month−1) compared to that of Fluxcom and LGS-Reco. Furthermore, with the inclusion of high-latitude flux observations, CIML-TER also performed better in tundra types (TWE、GRT、BWE、SBV、SHT in Fig. 2). For instance, the rMAE of CIML-TER in SHT was only ~15%. In addition, although all TER products showed relatively better accuracy in CSH than in other biomes (Fig. 2), it need to be cautious to consider such nice performances due to the limited number of flux sites with CSH labels. Moreover, CIML-TER was better able to reflect the real TER dynamics observed at the flux sites (Supplementary Fig. 3). For the EBF and DBF sites, CIML-TER can capture the relatively high TER fluxes during the peak period of a growing season, whereas such TER fluxes of Fluxcom and LGS-Reco were underestimated or saturated. Moreover, CIML-TER also effectively captured the TER dynamics in low-biomass regions; for instance, it accurately replicated the relatively low TER fluxes during the peak period of a growing season in the northern peatlands and sparse vegetation (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 3, BWE and SBV). In contrast, Fluxcom and LGS-Reco tended to overestimate such TER fluxes. Additionally, CIML-TER can depict more complex dynamics of TER (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 3, SAV and GRA) rather than simple sinusoidal periodic variations, due to the more comprehensive consideration of factors relevant to TER.

a R2, b MAE, c rMAE. EBF evergreen broad-leaf forest, ENF evergreen needle-leaf forest, DBF deciduous broad-leaf forest, DNF deciduous needle-leaf forest, MF mixed forest, WSA woody savanna, SAV savanna, CSH closed shrub, OSH open shrub, GRA grassland, CRO cropland, WET wetland, TWE tundra wetland, GRT graminoid tundra, BWE boreal wetland or peatland, SBV sparse boreal vegetation, SHT shrub tundra. These biome types come from labels of flux sites.

Global patterns of TER

CIML-TER exhibited a similar global pattern of TER to that of Fluxcom and LGS-Reco, displaying high values in low latitudes and low values in high latitudes (Fig. 3). The total estimates of all three TER products were relatively consistent in the middle and high latitudes, but displayed great differences in the low latitudes. Specifically, the spatial variations between CIML-TER and Fluxcom were generally similar, although the TER estimates of Fluxcom were obviously lower than those of CIML-TER. As for LGS-Reco, its TER estimates in the subtropical latitudes of northern hemisphere were relatively align with those of CIML-TER, whereas such estimates became saturated around the equator (Fig. 3d).

The spatial pattern of CIML-TER was more representative of the real world. Based on the detailed spatial pattern comparison across several typical regions, we evaluated their performance in characterizing the internal differences within a single PFT, as well as the spatial variations in transition zones (Fig. 4). In the region of interest (ROI) 1, Amazon Forest, CIML-TER depicted detailed internal differences within the EBF type (Supplementary Fig. 4), whereas the estimates of both Fluxcom and LGS-Reco products were relatively homogeneous. Similarly, for the ROI 3 region, East Asia, CIML-TER distinguished the differences between subtropical EBF and temperate EBF (Fig. 4, ROI 3). In addition, the spatial variation of CIML-TER was more realistic. It effectively described the gradual transition of TER between different land cover types, since it did not rely on the discrete one-hot codes of PFTs as inputs (e.g., Fluxcom) or separately set parameters according to coarse classification maps with discrete labels (e.g., LGS-Reco). For example, in the ROI 1 and 2 regions, the results of LGS-Reco showed clear boundaries between PFTs. Moreover, although Flxucom performed relatively better than LGS-Reco in the transition zones, its calculation modes on the both sides of boundaries were still quite different, leading to a clear boundary between SAV and EBF in the ROI 2 region (middle Africa, Supplementary Fig. 4). On the contrary, the gradual transition of TER between EBF and SAV was well depicted in CIML-TER, reflecting the gradually continuous variations of biomes between different land cover types. As for the ROI 4 and 5 regions (North America and Europe), which have the largest number of flux sites, there was no great difference among all three TER products in terms of spatial patterns and estimates.

The inter-annual variation trend of CIML-TER differed from those of other TER products (i.e., Fluxcom and LGS-Reco), which was reflected in the total variation rate and the spatial pattern. For the inter-annual variation results of all TER products, regions exhibiting increasing and decreasing trends of TER concurrently existed, while these regions were not consistent across all products (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). Meanwhile, in both CIML-TER and LGS-Reco estimates, the area of regions with significant increasing trends of TER was larger than that of regions exhibiting significant decreasing trends, displaying a global increasing trend of TER. In contrast, the TER estimates of Fluxcom showed a slightly global decreasing trend. As for the spatial pattern, regions with inter-annual increasing trends of TER in CIML-TER were primarily distributed in the high latitudes of northern hemisphere where the other products detected less significant variation trends of TER (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). Moreover, the results of CIML-TER showed relatively strong increasing trends of TER in southern China, western India and parts of tropical EBF, while regions exhibiting decreasing trends were mainly located in the Amazon Forest and the eastern Canadian boreal forest. Additionally, CIML-TER revealed that the TER of EBF showed a generally increasing trend, despite the existence of significant decreasing trends in certain EBF regions. In contrast, the TER of EBF displayed generally decreasing trends in the Fluxcom and LGS-Reco products (Fig. 6). Notably, we found that the inter-annual increasing rate of TER in permafrost was much higher than that in EBF (about 5 times for the relatively value, Fig. 6), and the increasing rate of TER in the core regions of permafrost (continuous and discontinuous permafrost) was slightly higher than that in the edge regions (sporadic and isolated permafrost).

a Theil–Sen trend, b relative Theil–Sen trend. These figures only show the region with significant trend (Mann–Kendall trend test, p < 0.05), and the region with non-significant trend or no data is plot in gray color. The frequency histogram is located at each figure’s lower left corner. For the trend maps of Fluxcom and LGS-Reco products, see Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6.

a Theil–Sen trend, b relative Theil–Sen trend. The mean slope value is calculated through area-weighted averaging method (only including pixels with significant Mann–Kendall trend, see Fig. 5), and the error bar means the area-weighted standard error (SE). The evergreen broad-leaf forest region is derived from MCD12 v061. Specifically, we selected pixels of which the “EBF” label never changes between 2001 and 2020 as the final region. In addition, the permafrost map we used here is from Obu et al.98.

Key drivers for TER variations

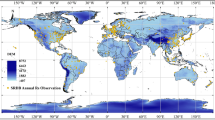

Based on the interpretable machine learning framework, we found that variables related to vegetation structure, component and phenology, which are often not well parameterized in traditional TER estimation models, were also key factors influencing large-scale TER. The global pattern of relative |SHAP| value showed that the environmental conditions were still the dominant drivers of TER (most of the areas in Fig. 7 are in red-like colors, especially in savanna, India and the high latitudes of northern hemisphere), which contributed about 44.15% (standard deviation (SD) = ±11.1%, range from 3.51 ~ 82.45%) of global TER variability. Meanwhile, the biotic factors, which describe the ecosystem-scale information such as physical structures and components, played a crucial role (regions with green-like colors in Fig. 7) in the middle- or low-latitude regions with high biomass (e.g., EBF), low biomass (e.g., desert steppe) or high elevation (e.g., the Rocky Mountains). Biotic factors contributed about 25.91% (SD = ±9.8%, range from 1.34 ~ 68.52%) of global TER variability. Finally, the spatiotemporal variation factors, which describe detailed differences of land cover and phenology across pixels, were also important drivers of TER and played a dominant role in croplands (e.g., the corn belt of USA and the croplands in middle Europe, regions with blue-like colors in Fig. 7). The spatiotemporal variation factors contributed about 29.94% (SD = ±7.2%, range from 2.96 ~ 78.53%) of global TER variability. In addition, for each individual input variable (Supplementary Fig. 7), the nighttime LST was averagely the most important driver of TER, contributing approximately 30-40% TER variability across the world. The SOC30 variable (i.e., the 30–50 cm SOC) contributed the most TER variability among all three depths of SOC variables (about 15-30% in the high latitudes of northern hemisphere). Moreover, LAI is the most dominant variable among all biotic factors, contributing about 20–30% TER variability in middle and low latitudes. The AreaNIRv variable, representing the one-year accumulated value of NIRv, contributed the highest TER variability among all spatiotemporal variation factors (with contribution rates near 35% in some regions, e.g., the corn belt of USA and the North China Plain).

The contribution rate of each group is integrated by corresponding input variables’ relative |SHAP| values on each pixel. The red, green and blue colors represent the influencing variables of environmental conditions (daytime and nighttime LST, LSWI and SOC at 0, 30, 50 cm), biotic factors (LAI, CI, PV, NPV, BS and NIRv) and temporospatial variations (SCVTG, representing the spatial continuous differences of vegetation type and phenology), respectively.

The SHAP dependency plots quantified each individual input variable’s effect on TER, as well as corresponding sensitivity. As the daytime and nighttime LST increased, TER kept stable when LST was below 0 °C and started to increase when LST was above 0 °C (Fig. 8a, b). Meanwhile, both SHAP dependency plots of daytime and nighttime LST showed unimodal shapes, peaking at around 20–30 °C. As for NIRv, the proxy of Gross Primary Productivity (GPP), TER kept stable when NIRv was below 0.08 and then turned into a sustained increase with increasing NIRv (Fig. 8c). TER continuously increased with increasing LAI (Fig. 8d) and decreased with increasing CI (Fig. 8f). Furthermore, TER was relatively stable when the PV cover was below 50%, whereas it then converted to increase with increasing PV cover and peaked at around 75% (Fig. 8e). TER generally increased with increasing AreaNIRv, although such relationship was non-linear (Fig. 8g). Since the SOC input data are temporally stable, the SHAP dependency results of SOC actually showed their spatial different effects on TER (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Fig. 8h). Specifically, the TER process would get inhibited in regions with high SOC0 (SOC at 0–10 cm), and the regions with about 50 g kg−1 SOC30 (SOC at 30–50 cm) would lead to higher positive response for TER.

Notably, only the variables with relatively greater effects on TER were displayed here, and the complete SHAP dependency results can refer to Supplementary Fig. 8. The numbers along the y-axis represent the SHAP-values for TER and indication of response in the variable. The red dashed lines indicate SHAP-values of zero, where the response of TER is nonchanging. Solid dark blue lines denote response in TER as the predictor variables undergo change. The background light blue color represents low point density, and the dark red color donates high point density.

In summary, the influencing variables—environmental conditions (i.e., LST, LSWI and SOC), biotic factors (i.e., LAI, CI, PV, NPV, BS and NIRv), and spatiotemporal variations (i.e., the shape of annual vegetation index time line)—are all key drivers of TER. Meanwhile, our results highlighted the crucial role of vegetation structure and phenology on TER, since the general contribution of environmental conditions on TER was below 50%. Additionally, each variable’s effect on TER varied differently over space, resulting in great regional differences of TER-related estimation mechanisms.

Discussion

Model performance

CIML-TER obviously improved the TER estimation accuracy, compared with the similar TER products, partly due to the more adequate flux observations. Not only the Fluxcom and LGS-Reco datasets that were compared in this study5,22, but also the other similar TER products24 or models11, they all rely on the FLUXNET dataset (or a subset) for model construction and parameter calibration. However, the spatial distribution of FLUXNET sites is uneven, particularly lacking flux observations in regions with low biomass or in high latitudes. Therefore, theoretically, the CIML-TER should achieve higher estimation accuracy, since it integrated additional long-term in situ observations and encompassed a broader range of land cover types. This was proven by its superior performance in the site-scale accuracy evaluation (Fig. 1) and the more realistic global spatiotemporal patterns (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition, we found that the estimation accuracy of similar TER products got greatly decreased when applied on the ABCflux dataset (Fig. 1), resulting in a relatively lower overall accuracy than that of their original studies (e.g., the R2 of LGS-Reco was 0.65 in its original study, but here is 0.40). In summary, the integration of in situ observations from two flux networks had achieved further information complementarity, obviously enhancing the TER estimation accuracy in the high latitudes of northern hemisphere.

CIML-TER also had strong generalization abilities due to the causality constrained interpretable machine learning framework and the utilization of SCVTG variables. This study leveraged the feature importance derived from PCMCI+41,42 as prior references for model training, which efficiently modulated model’s physical and causal structures (Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). Additionally, we followed Zhu et al.’s44 advice to avoid using discrete classification data in model construction. Instead, we employed a set of numerical variables derived from the dimensionality reduction of vegetation index time series (i.e., SCVTG) to depict the continuous variation of vegetation types and phenology across pixels. Specifically, the traditional PFT data provide oversimplified labels of land cover, which is primarily designed to facilitate human understanding. However, these finite labels fail to describe the spatial continuous variation of land cover, causing great differences in environmental and ecosystem properties within regions sharing the same PFT label. This limitation was especially evident in our comparison experiment across key ROIs (Fig. 4); the products using discrete land cover data would show obvious boundaries in the TER result. Moreover, this limitation likely explained the lower accuracy of similar TER products on the ABCflux dataset. Specifically, the MCD12 land cover data45, commonly used in carbon flux models, does not include a dedicated label for tundra types. Consequently, the low-latitude savanna and high-latitude (or high-elevation) shrub tundra are assigned the same label (e.g., SAV or WSA), which compromises model accuracy. Additionally, the sparse distribution of flux sites in high-elevation and high-latitude regions exacerbates this issue. The calculation mode sharing the same land cover label would be more weighted towards subregions with more flux sites, limiting their generalization ability. On the other hand, the discrete land cover data (e.g., MCD12) was originally derived from vegetation index time series46, but it lost too much information in order to facilitate human understanding. The SCVTG, a set of numerical variables, used in this study was derived from a moderate information compression process to retain more information of a time series44. In other words, the numerical variables were key signals designed to offer detailed descriptions for estimation models instead of setting several calculation modes by discrete labels to facilitate human understanding. In addition, the spatial pattern comparison of TER in North America and Europe (Fig. 4, ROI 4 and 5) further illustrated the difference in the generalization ability between CIML-TER and the other products (i.e., Fluxcom and LGS-Reco). In North America and Europe, all three products had similar TER estimates, since the flux sites are spatially concentrated in such places and all three products essentially used the flux data to support model training or parameter calibration. However, for regions with sparse site distribution, the CIML-TER model exhibited better spatiotemporal dynamics and higher generalization ability (Fig. 4, ROI 1 to 3). As for the estimation uncertainty of CIML-TER, the standard deviation was generally higher in low-latitude regions (Supplementary Fig. 11a) due to the high biomass and complex vegetation structures in such regions. However, the estimation uncertainty of CIML-TER was more obvious in regions with high elevation or desert in terms of the relative value of standard deviation (Supplementary Fig. 11b).

CIML-TER can effectively capture variations in temperature response sensitivity across vegetation types. Specifically, the temperature response curves exhibited distinct shapes across vegetation types, according to the SHAP values for daytime and nighttime LST (Supplementary Fig. 12). Interestingly, samples for some types did not often cluster along a single, well-defined curve. Instead, they showed a relatively dispersed distribution in the TER-LST space, displaying multiple curve shapes (e.g., WET and GRA in Supplementary Fig. 12). This indicated that even within regions or sites accurately labeled with the same PFT, significant internal differences can persist. Furthermore, while the temperature response curves for most vegetation types follow traditional exponential forms, the unimodal curves are evident in the daytime TER-LST relationships of certain vegetation types, such as DBF, WSA, SAV, OSH, CRO, and WET (Supplementary Fig. 12).

The roles of vegetation structure and phenology on TER

Vegetation structure can regulate terrestrial ecosystem respiration (TER) by influencing carbon allocation, energy exchange processes, and microbial activity. The LAI enhances light interception by the canopy, thereby driving seasonal variations in TER through autotrophic respiration47 (Fig. 9a, e). Our results revealed the nearly linear positive relationship between LAI and TER (Fig. 8), which also support some studies that use LAI to simulate the “reference ecosystem respiration” (Rref) parameter within the Q10 or Arrhenius frameworks26. The CI, which quantifies the spatial distribution of foliage, is well-known in modulate canopy radiation and can indirectly promote TER through the enhancement of canopy light-use efficiency48 (which can increase GPP). However, our results also detected CI’s unique effects on TER, although its magnitude was relatively smaller than that of LAI. Specifically, the CI showed a general negative relationship with TER (Fig. 8f and 9b, f). We think this phenomenon may be related to the daytime inhibition of TER29. Based on the canopy radiative transfer simulation models, it is demonstrated that lower CI values (indicating a more clumping distribution of leaves) can reduce the total canopy radiation absorption and the shoot-level irradiance at the top of the canopy49, which may mitigate the daytime inhibition of ecosystem respiration in some degree. The ratio of PV to NPV and BS cover further mediates TER by balancing carbon inputs and outputs. High PV coverages usually mean higher GPP50 and autotrophic respiration, and this positive effect on TER was relatively larger than that of CI (Fig. 9c, g). Unlike the PV coverage, the relationships between NPV and TER are relatively complex and remain unclear due to the uncertainty of NPV (e.g., data source, definition). Based the NPV data derived from spectral mixture analysis, we found out that although the NPV generally showed no obvious effect on TER (Supplementary Fig. 8p), such effects were important in specific plant functional types (Fig. 9d, h). Specifically, the relationship between NPV and TER were relatively simpler in ENF and GRA, but were more complex in EBF, DBF, MF and OSH (Fig. 9d, h). For instance, after the peak of growing season in ENF (northern hemisphere), as the decrease of PV and the increase of NPV, the SHAP values of NPV got to the peak which may mean the soil respiration pulse induced by the increasing litters, and such positive effect of NPV on TER was then gradually suppressed as the decreasing temperature. As for NIRv, the robust proxy of GPP, it showed a stable relationship with TER when its value is above 0.08. This result can partly support Waring’s hypothesis51, which suggested that the Net Primary Production (NPP):GPP ratio generally tends to be stable52,53. However, our results suggested that this proportional relationship may not be stable in low-GPP situations (Fig. 8c), given the linear relationship between NIRv and GPP.

Besides the seasonal dynamic of variables representing vegetation structure that mentioned above, phenology can also regulate TER through the length of growing season. Within the variables of SCVTG, the AreaNIRv is the one-year accumulated value of daily NIRv, which is widely used as a proxy of GPP or biomass54,55, and our results suggested higher AreaNIRv would lead to higher TER (the significant positive Pearson coefficients between TER and AreaNIRv in Supplementary Fig. 13), especially in EBF. However, such relationships were relatively less obvious in the tundra ecosystems (relatively lower values of Pearson coefficients), partly due to the lower contribution ratio of autotrophic respiration in those high-latitude ecosystems56,57. Additionally, in theory, the longer growing season usually means more autotrophic respirations, but our results revealed such effects were different among plant functional types (Supplementary Fig. 13). For instance, for all three LXX variables of SCVTG (i.e., L25, L50 and L75), only the L25 showed significant positive relationships with TER in CSH and OSH, which means the TER of shrub land was more sensitive to the whole length of growing season. Alternatively, the longer time spans with high NIRv (i.e., L50 and L75), representing less disturbances during growing season (e.g., short-term droughts), were significantly important for higher TER in CRO and DNF (Supplementary Fig. 13), rather than the whole length of growing season (i.e., L25). However, it is still a challenge to analyze the effect of vegetation phenology on TER, since the high inconsistency among different remote sensing-based phenological metrics58 and the diverse physical meanings between satellite-based and ground-observed phenology59. In general, we generally quantified the effect of phenology on TER (Figs. 7, 9, Supplementary Figs. 8 and 13) and highlighted its role in future TER modelling.

Global TER estimates

Global annual CIM-TER budgets ranged between 117 and 125 Pg C (Fig. 10), higher than the estimates of Fluxcom and LGS-Reco5,22,23, but located in the middle of the estimates of mainstream process models (Fig. 10). Notably, the RS version of Fluxcom has a higher spatial resolution (0.0833°) compared to the RS + METEO version (0.5°), with slightly lower mean estimates. Specifically, for the site scale, the RS version is averagely 0.1 g C·m−2·day−1 lower than the RS + METEO version23, leading to a global TER budget of only 83 Pg C for the Fluxcom RS version—approximately 10 Pg C less than the RS + METEO version16. Previous research has suggested that global annual TER should be in the range of ~100–110 Pg C21. For instance, the global TER estimate of Yuan et al.11 derived from Q10 function was 103 Pg C and that of Ai et al.60 was 95 Pg C. However, these previous studies lacked information describing the ecosystem-scale properties (e.g., vegetation structure, component and phenology), resulting in significantly underestimation of TER, especially in the EBF regions (Figs. 3, and 4). In addition, Lai et al.61 used carbonyl sulfide as an indicator and estimated global GPP at around 159 Pg C, much higher than the typical 120–140 Pg C from earth system models62,63, highlighting potential underestimations of GPP in tropical EBF regions. Therefore, given the global net ecosystem change is relatively a small value (~0–10 Pg C), the range of ~100–110 Pg C may largely underestimate the global TER. In summary, the global TER budgets of CIML-TER (excluding deserts, water, ice and snow regions) aligned well with the existing mainstream standards and suggest a global NEP within 10 Pg C when combined with the earth system model GPP estimates, which was also consistent with the conclusion of Global Carbon Budget3,63. Importantly, since existing process models are highly dependent on the discrete land cover data, our CIML-TER can further provide more detailed and realistic spatiotemporal dynamics, which can support the development of future process models.

CIML-TER revealed a global increasing trend of TER with a rate of 0.9%·yr−1 (approximately 1.08 Pg C·yr−1), which was higher than the rate detected by Fluxcom and LGS-Reco products but aligned closely with the rate observed in process models (Fig. 10). While the Fluxcom product, often used as a benchmark for carbon flux evaluation64, failed to capture long-term carbon flux variability, CIML-TER successfully depicted the inter-annual variation of TER. This is attributed to the utilization of PCMCI+ and continuous descriptions of spatiotemporal variations44. In addition, CIML-TER’s increasing rate was roughly twice higher than that of LGS-Reco. This discrepancy arises from LGS-Reco’s reliance on the single variable-driven model structure. In other words, although LGS-Reco integrated several single variable-driven models, each pixel’s estimate ultimately depends on only one of these models, which limits its ability to fully capture TER variations and leads to saturation issues. In contrast, CIML-TER incorporated multiple variables, especially concurrently considering the limitations related to temperature and substrate availability—key constraints parameterized in process models. This variable design also explains the similarity in global increasing rates of TER between CIML-TER and process models. Additionally, the temperature response sensitivities of CIML-TER displayed unimodal patterns in several vegetation types (Supplementary Fig. 12). These unimodal patterns were consistent with the advanced Macromolecular Rate Theory (MMRT) theory8,65, which offered a more accurate description of the enzyme-mediated biochemical reactions compared to traditional models like Q10, Lloyd & Taylor and Arrhenius. Therefore, CIML-TER results can also inform and refine temperature response functions in process models, optimizing their predictive capabilities.

Regions with significant inter-annual variation trends identified by CIML-TER were consistent with the conclusions of relevant research. For instance, CIML-TER detected a relatively high increase of TER across the subtropical EBF regions of southern China (Fig. 5), which was not detected in similar products. This result aligned with the increasing trend of GPP and tree coverage in such regions62,66. The autotrophic respiration domain the variability of TER in the subtropical EBF regions, given the autotrophic respiration takes a larger part of TER in such biomes57,67. Furthermore, the atmospheric deposition supplies large amounts of nitrogen to Asian subtropical forests68, which can stimulate tree growth69 but alter soil respiration slightly or limit soil respiration70. Additionally, although all three TER products detected the inter-annual decreases in EBF regions, their extents differed. Fluxcom and LGS-Reco displayed widespread decreasing TER trends across EBF regions (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6), whereas CIML-TER found that these decreases were mainly distributed in the Amazon Forest. CIML-TER also demonstrated that the overall variation trend of TER in EBF regions was increasing. Such results matched the biomass loss patterns in Amazon linked to deforestation and subsequent degradation71, predominantly on the southern and eastern edges. Additionally, CIML-TER detected decreasing TER trends in parts of the Canadian boreal forest, consistent with the more severe forest cover loss observed in that region72,73. Finally, CIML-TER identified widespread increasing TER trends across the global tundra, while similar products only captured this trend sporadically (e.g., in Siberia, Supplementary Fig. 5). These findings of CIML-TER were supported by the in situ observations in tundra74,75, attributing the increase of TER to the Arctic amplification effect and warming soils across the pan-Arctic region.

Limitations and prospects

Current soil data with low temporal resolution partly limits the estimation accuracy of existing TER models. TER includes autotrophic respiration of plants and heterotrophic respiration from decomposition by soil organisms. However, the lack of soil data with high spatiotemporal resolution makes the model hard to capture the variation of soil properties and corresponding effects on TER. Additionally, the soil respiration takes a relatively larger proportion of TER in the pan-Arctic region56,57, which means the uncertainties caused by this temporally stable SOC data would lead to greater effects on TER estimation in those high-latitude ecosystems. Meanwhile, it was demonstrated that the dynamics of soil nitrogen and moisture are critical predicters of TER in tundra ecosystems75. Therefore, the estimation accuracy of CIML-TER on ABCflux (only contains sites of the pan-Arctic region) remained lower than that on FLUXNET (mainly contains sites of the temperate region), although CIML-TER had greatly improved the TER estimation accuracy in the high latitudes of northern hemisphere. In general, complementing more detailed soil information into TER estimation models is expected to further improve the estimation accuracy.

In addition, the flux observation data in this study still exhibit a sparse and uneven spatial distribution, although we had integrated the FLUXNET and ABCflux in this study. Given the flux observations are almost the only direct way to evaluate and validate carbon flux models, researchers need to enhance collaboration and share more flux observations with the academic community. This effort can further fill the observation gaps of some land cover types (especially for low-biomass regions) and increase the representativeness of estimation models.

As for the mechanism of respiration estimation, the unimodal function based on MMRT theory is supposed to be the future direction to optimize existing process models. Furthermore, incorporating ecosystem-scale relevant variables (e.g., vegetation structure, component and phenology) into future estimation models is also crucial. Specifically, Niu et al.8 demonstrated that most of the TER temperature response curves (e.g., Q10, Arrhenius and MMRT) are special cases of the van’t Hoff equation. Moreover, their work used the Community Atmosphere Biosphere Land Exchange (CABLE) model76 and showed that the existing process models with strictly monotonically increasing temperature response functions struggled to replicate the widespread thermal optimality of TER. They suggested replacing traditional oversimplified temperature response functions with MMRT to better elucidate the thermodynamic properties of enzymes involved in respiration. We also agreed with that opinion but found that the temperature response sensitivity differed between day and night (Supplementary Fig. 12), and the detected optimal temperatures of TER (Topt) were much lower than those observed in laboratories for single components8,77. For instance, the organization-level Topt of respiration is about 40–60 °C8,18 (e.g., leaf level). Future work should explore the cause of the Topt gap between ecosystem and organization levels. Understanding this gap can clarify the influencing process between ecosystem and environment (e.g., inhibition of daytime respiration29) and the interactions among ecosystem components, ultimately aiding in the parameterization of such ecosystem-scale effects in TER estimation models. In summary, researchers need to notice that temperature is not always the dominant influencing factor for TER estimation across the world (Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. 7). Other variables that provide detailed descriptions of ecosystem-scale information (e.g., clumping index, NPV) and spatiotemporal variations (e.g., phenology) should also be considered in future model constructions.

Conclusions

We integrated variables that detailedly describe ecosystem-scale information and continuous spatiotemporal variations into TER estimation. Specifically, we used a causality constrained interpretable machine learning framework (PCMCI + , XGBoost, SHAP) and established a TER estimation model called “CIML-TER”. Based on the CIML-TER model, we generated high-accuracy global monthly TER estimates at a spatial resolution of 0.05° during 2001–2020. Meanwhile, the influence of different drivers on TER were quantitatively depicted through the SHAP tools, subsequently revealing their diverse spatial patterns. The main conclusions of this study are as follows:

-

1)

CIML-TER significantly improved the estimation accuracy of TER in the high latitudes and EBF regions, demonstrating strong generalization abilities on the global scale and effectively reflecting the naturally continuous variations of TER in the transition zones of different land cover types.

-

2)

The global TER budgets estimated with CIML-TER (excluding deserts, water, ice and snow regions) ranged from 117 to 125 Pg C, exhibiting a generally increasing inter-annual variation trend (0.9%·yr−1) during 2001–2020.

-

3)

Substantial regional variability existed in the influence of different drivers on TER. Beyond hydrothermal factors (contributing ~44.15 ± 11.1% of global TER variability), biotic factors (25.91 ± 9.8%) and spatiotemporal variation factors (29.94 ± 7.2%) were also critical. Future developments of TER modules in earth system models should incorporate these ecosystem-scale variables alongside traditional hydrothermal factors.

Methods

Site data

In this study, site-month data from two flux observation networks (FLUXNET 2015 and ABCflux) were used in model construction and accuracy assessment. FLUXNET 2015 is a standardized ensemble dataset of regional flux networks (e.g., AmeriFlux, AsiaFlux) and provides observations of 212 flux sites at different temporal resolutions (hourly, daily, monthly, and annually). ABCflux is also a standardized ensemble dataset of flux observations focusing on the pan-Arctic region, which provides monthly flux data from 244 sites. Incorporating the ABCflux dataset can greatly address the data gap of FLUXNET in regions with sparse vegetation or high latitudes, which would help to further reduce model estimation errors. In this study, the monthly TER flux observations (“RECO_NT_VUT_REF” in FLUXNET and “reco” in ABCflux) were used to support model construction and accuracy evaluation. We conducted quality controls on these flux observations based on following principles: (1) Each site-month sample should pair with high-quality remote sensing data; (2) samples with low-quality labels for TER were excluded (samples with “NEE_QC” below 0.75 or with “-9999” label). Finally, we obtained a dataset containing 20,622 site-month samples from 304 sites (see Supplementary Table 2 and 3 for details of flux sites) during 2001 to 2020 (samples after 2015 are all from ABCflux). In addition, we converted the unit of TER in FLUXNET from g C·m−2·day−1 to g C·m−2·month−1 through the days of each month, guaranteeing the unit consistency between two flux datasets.

Model input data

By systematically synthesizing the previous research about TER estimation (see Supplementary Table 4), we found that soil and air temperature, moisture, vegetation productivity, soil type and soil organic carbon (SOC) have all been identified as important drivers of TER5,22,78. We divided the relevant variables into three groups (Supplementary Fig. 1) based on prior knowledge and previous publications: (1) The first group represents environmental conditions, including hydrothermal factors and soil properties; (2) biotic factors, the second group, contain variables describing ecosystem-scale information of each pixel, such as leaf area index (LAI), clumping index (CI) and non-photosynthetic vegetation cover (NPV); (3) the third group is related to spatiotemporal variations, which describe the differences of vegetation types and phenology across pixels.

We selected part of traditional variables according to previous studies (see Supplementary Table 4), which included daytime and nighttime land surface temperature79 (LST, MOD11A1 v061, daily, 1 km), leaf area index80 (LAI, MOD15A2H v061, 8-day, 500 m), NIRv index81 (calculated from MCD43A4 V061, daily, 500 m), land surface water index (LSWI, calculated from MCD43A4 V061) and SOC82 (SOC0, SOC10, SOC30, OpenLandMap, temporally stable, 250 m). Notably, previous studies commonly used EVI as the proxy of GPP. However, we chose to use NIRv here, because NIRv has a stronger correlation with GPP83 and TER (see Supplementary Fig. 14).

Nonetheless, the traditional variables mentioned above do not provide a comprehensive picture of the factors affecting ecosystem-scale TER, particularly lacking variables related to ecosystem structures (e.g., vegetation structures) and detailed descriptions about spatiotemporal differences. It has been known that the ratio of photosynthetic to non-photosynthetic vegetation (the horizontal vegetation structure) can alter the rate of carbon and nutrient uptake, latent and sensible heat exchange and surface albedo, subsequently influencing ecosystem respiration84. Previous studies have tried several ways to consider the seasonal dynamics information in TER or other carbon fluxes estimation, such as the extremes or amplitudes of vegetation index time series4,23. However, such variables reflecting the annually mean status of each pixel cannot provide reliable information on long-term variability. Therefore, the machine learning models, represented by Fluxcom, exhibited poor performance in terms of inter-annual variability16,64. For this issue, Zhu et al.44 developed a set of continuous numerical variables that vary annually by downscaling (so called “pooling”) the time series of vegetation index (see Supplementary Fig. 15), which can quantitatively describe the differences of vegetation type and phenology across pixels. This variable set is called as “seasonal characteristics of vegetation types and growth” (SCVTG) and contain 9 numeric variables (Vtop, Vbottom, V75, V50, V25, L75, L50, L25 and AreaNIRv), which are derived from the smoothed upper envelope (Savitzky-Golay filtering) of VI time series. Specifically, the Vxx (Vtop, Vbottom, V75, V50, V25) variables are the quantiles of daily vegetation index value with a relatively special definition and the Lxx (L75, L50, L25) variables are the spans between two dates of key points of which value equal the quantiles mentioned above. Additionally, the AreaNIRv variable represents the one-year accumulated value of daily vegetation index. Compared with traditional discrete PFT labels, SCVTG can describe the differences within regions with the same PFT labels. Moreover, SCVTG was proven to be a viable alternative to PFT data in machine learning-based GPP modelling, which can concurrently ensure estimation accuracy and inter-annual variability44. Therefore, we applied the SCVTG to describe the continuous variations of vegetation type and phenology across pixels. Furthermore, we used the GFVCP dataset (8-day, 500 m) derived from spectral mixture analysis85,86 to represent horizontal vegetation components (the relatively coverage of bare soil, non-photosynthetic vegetation and photosynthetic vegetation). In addition, the data describing leaf distribution (clumping index data from CAS-CI, 8-day, 500 m) derived from BRDF models87,88 were concurrently integrated into the TER estimation framework.

Finally, all the gridded data mentioned above were temporally aggregated to the monthly scale through the median value of each month and spatially resampled to 0.05°.

Other TER products

To evaluate the performance of our new TER estimation model, we downloaded gridded TER data from Fluxcom22,23 and LGS-Reco datasets5. Fluxcom is an ensemble flux product that integrates estimation results from various machine learning methods. It contains two ensemble versions, the RS version (0.0833°, 8-day) and the RS + METEO (0.5°, daily) version. We used the RS version in this study, given its relatively higher spatial resolution. The Fluxcom RS data was resampled to 0.05° via the bilinear method, and its unit (g C·m−2·day−1) was converted to monthly accumulated values (g C·m−2·month−1) through the days of each month. LGS-Reco is an ensemble product (0.05°, daily) that integrates several pure empirical models. This product is highly dependent on the classification maps of vegetation types, since it specifically selected the most suitable empirical model for each pixel based on the land cover label. It is demonstrated that LGS-Reco can reflect the long-term trends of TER variations. In addition, we also collected the estimates of global total TER from several process models (e.g., TRENDY, BESS)16 to quantitatively compare the global carbon budgets of all TER products. Notably, all gridded data were aggregated into a monthly scale.

Modelling TER

We employed the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) method, a tree-based machine learning algorithm, to construct the TER estimation model (the hyperparameters of XGBoost can refer to Supplementary Table 5). The tree-based models have been widely used in carbon budget-related research, such as the random forest and model tree ensemble methods21,23, which have been proven to perform well in extending the site-scale experience to the regional or global-scale applications89. XGBoost is a decision tree-based model, but unlike traditional decision trees, XGBoost uses gradient boosting to iteratively train decision trees, which has strong nonlinear fitting capabilities and is widely used to model complex relationships between target and environmental variables33,90. In this study, the 10-fold cross validation method was used to train and validate CIML-TER model, concurrently guaranteeing that the training and test sets did not share the same flux sites. The generalization ability was assessed through a comparison experiment on the test dataset (the integration of 10 folds’ test sets). The final estimation results of the CIML-TER model were the mean of all folds’ outputs (Supplementary Fig. 1). Meanwhile, the training process of each fold was carried out for 20 times to ensure the stability of final estimates (the random seed is different in each round).

We took the feature importance derived from causal inference techniques as prior references in the model training process. The causal inference methods represented by the PCMCI family (PCMCI, PCMCI+, LPCMCI, etc.) are highly robust and can retain high performance even with high-dimensional data41,91. These methods were widely used in ecological and geographical research, such as detecting remote correlations between climate modes or interpreting changes in surface energy flux92,93,94, since they can deal with the confounding causal links between variables. Specifically, it regulated the generation process of each decision tree during the training process of XGBoost and made soft constraints on model structure. The PCMCI-derived variable importance served as references of variable weights in model training, which adjust the probability of each variable to be selected as a candidate for the nodes of each decision tree. This approach ensured that variables with stronger causal effects on TER were more likely to be used as nodes in each decision tree of XGBoost. It also maintained the ability of capturing data patterns, since the final selection of whether a variable can be a node still depends on the gradient boosting algorithm and the statistical metrics of information entropy. Moreover, it can also reduce the risk of misjudging the dominant driver, since both the causal information and XGBoost algorithm-related statistical metrics are merged in model structure. Finally, the Causality constrained Interpretable Machine Learning model for TER estimation in this study is abbreviated as “CIML-TER”.

In addition, we also analysis the how the causal effect derived from PCMCI+ modulate the model structure of XGBoost (Supplemetary Figs. 8 and 9). Specifically, For the physical model structure, we used the “weight” parameter of XGBoost model to quantify the effect of adding causal constraints. The “weight” parameter means the number of times that a variable was selected as a node in XGBoost trees. Hence, it is easy to compare the physical structures between baseline and causal XGBoost models via their differences on each variable’s normalized “weight” parameter. In addition, we used the SHAP tool to derive the feature importance of each input variable, representing the causal structure of model. We then compared it with the causal effects derived from PCMCI. In theory, the causal structure of the causality guided XGBoost model should be more similar to the causal effect derived from PCMCI+.

Model evaluation

We evaluated the model performance in terms of estimation accuracy and spatiotemporal variation. Specifically, we conducted several accuracy comparison experiments based on flux observations (FLUXNET, ABCflux) and other TER products (Fluxcom, LGS-Reco). These evaluations were carried out at three scales: site-month, site (i.e., the mean aggregation of all site-month samples at each site) and PFT (PFT labels were from flux network records). Meanwhile, the mean absolute error (MAE), relatively mean absolute error (rMAE) and coefficient of determination (R2) were used as accuracy metrics to quantitatively assess model performance. MAE is a widely used accuracy metric which can more stably reflect the overall error level of the estimation and will not cause large fluctuations in the evaluation results due to individual extreme outliers.

Where the N represent the number of samples, \({y}_{i}\) means the TER estimate of sample i, \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) means the true observed TER of sample i, and \(\bar{y}\) donates the mean of all observation values of TER.

In addition, the 2001–2015 (the intersected period) averages of all TER products (CIML-TER, Fluxcom and LGS- Reco) were used to qualitatively compare the spatial pattern. Moreover, the Mann–Kendall and Theil–Sen trend tests were applied to quantify the inter-annual variation trends of global TER in all products. The Mann–Kendall method can judge whether the data shows a significant trend, and the Theil–Sen trend test can provide a specific slope value of variation trend. This non-parametric trend detection methods are widely used in geosciences, such as identifying vegetation greening or browning95. Furthermore, since the flux sites for model training and evaluation in previous studies are mostly located in temperate regions, the TER of evergreen broadleaf forest and permafrost often showed relatively higher uncertainties. Therefore, we also compared the spatial consistency of regions exhibiting significant TER variation trends among all three products, and quantified their inter-annual variation trends in such key biomes (evergreen broadleaf forest and permafrost) through area weighted statistics.

Driver analysis

The SHAP tool was used to characterize the influence of each input variable on TER, which is based on solid game theories96 and can enhance the interpretability of machine learning models. SHAP can ensure that the global interpretations of model are consistent with the local explanations of each sample. It quantitatively explains how each input variable affects the final output. Specifically, positive SHAP-values show that a feature increases the response variable, while negative values show that a feature serves to decrease the response. The absolute value reflects the magnitude of the feature’s impact on the prediction. However, the calculation of SHAP is extremely time-consuming. Consequently, most previous studies only used site-scale data to run the SHAP tool39 rather than the gridded data, avoiding the computational burden. To overcome this challenge, we employed GPU acceleration to reduce the computation time. On a platform equipped with a single RTX 4080 graphics card, computing SHAP values for each monthly gridded data cost approximately 30 minutes. This approach enables us to quantify the contribution rates of influencing factors on TER and subsequently map their global spatial patterns, since the global-scale gridded input data were used to run the calculation of SHAP. Notably, we normalized the mean |SHAP| values of each pixel to evaluate the spatial difference of each variable’s contribution on TER. For each pixel, the calculation way was based on the following:

where SHAPi,j stands for the SHAP value of feature i for the jth sample; N is the number of samples; and M is the total number of features.

Uncertainty analysis

We evaluated two kinds of uncertainties in this study: the uncertainty of final model estimates, and the sensitivity of each input variable. Specifically, we used the standard deviation of 10-fold models’ estimates to quantified the uncertainty of model outputs. Given the randomness of machine learning models, this method can provide robust results about the fluctuations in model estimates across different regions, and it is also widely used in the field of carbon flux modelling and quantitative remote sensing24. Additionally, we used the dependency results derived from each variable’s SHAP values to reveal how could the different values of an input variable influence the final TER estimate. This SHAP-based dependency results of model input variables are also widely used in explain variables’ sensitivity and the relationship between predicters and target variable39,97.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The CIML-TER data and partial supplementary information are available on figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27634203). These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: The CAS-CI data used in this study are available from National Earth System Science Data Center of China (https://www.geodata.cn/thematicView/modisCI.html). The vegetation fractional data are available from Global Vegetation Fractional Cover Product (https://map.geo-rapp.org/). The flux observations are downloaded from FLUXNET 2015 (https://fluxnet.org/) and ABCflux (https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1934). The MODIS data and SOC data are download from Google earth engine.

References

Le Quéré, C. et al. Trends in the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Nat. Geosci. 2, 831–836 (2009).

Hashimoto, S., Ito, A. & Nishina, K. Divergent data-driven estimates of global soil respiration. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–8 (2023).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4811–4900 (2022).

Jägermeyr, J. et al. A high-resolution approach to estimating ecosystem respiration at continental scales using operational satellite data. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 1191–1210 (2014).

Tagesson, T. et al. Increasing global ecosystem respiration between 1982 and 2015 from Earth observation-based modelling. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 33, 116–130 (2023).

Dusenge, M. E., Duarte, A. G. & Way, D. A. Plant carbon metabolism and climate change: elevated CO2 and temperature impacts on photosynthesis, photorespiration and respiration. New Phytol 221, 32–49 (2019).

Keith, H. et al. Evaluating nature-based solutions for climate mitigation and conservation requires comprehensive carbon accounting. Sci. Total Environ. 769, 144341 (2021).

Niu, S. et al. Temperature responses of ecosystem respiration. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 559–571 (2024).

Lees, K. J., Quaife, T., Artz, R. R. E., Khomik, M. & Clark, J. M. Potential for using remote sensing to estimate carbon fluxes across northern peatlands – A review. Sci. Total Environ. 615, 857–874 (2018).

Luo, Y. & Zhou, X. CHAPTER 10 - Modeling Synthesis and Analysis. In: Soil Respiration and the Environment (eds. Luo, Y. & Zhou, X.) 215–246 (Academic Press, 2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012088782-8/50010-3 (2006).

Yuan, W. et al. Redefinition and global estimation of basal ecosystem respiration rate. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 25, GB4002 (2011).

Lloyd, J. & Taylor, J. A. On the temperature dependence of soil respiration. Funct. Ecol. 8, 315–323 (1994).

Arrhenius, S. Über die Dissociationswärme und den Einfluss der Temperatur auf den Dissociationsgrad der Elektrolyte. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 4U, 96–116 (1889).

Jones, C. D., Cox, P. & Huntingford, C. Uncertainty in climate–carbon-cycle projections associated with the sensitivity of soil respiration to temperature. Tellus B 55, 642–648 (2003).

Huntzinger, D. N. et al. Evaluation of simulated soil carbon dynamics in Arctic-Boreal ecosystems. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 025005 (2020).

Li, B. et al. BESSv2.0: A satellite-based and coupled-process model for quantifying long-term global land–atmosphere fluxes. Remote Sens. Environ. 295, 113696 (2023).

Janssens, I. A. et al. Productivity overshadows temperature in determining soil and ecosystem respiration across European forests. Glob. Change Biol. 7, 269–278 (2001).

Heskel, M. A. et al. Convergence in the temperature response of leaf respiration across biomes and plant functional types. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 3832–3837 (2016).

Cruz-Paredes, C., Tájmel, D. & Rousk, J. Can moisture affect temperature dependences of microbial growth and respiration?. Soil Biol. Biochem. 156, 108223 (2021).

Lu, R. et al. Improving the spatial and temporal estimation of ecosystem respiration using multi-source data and machine learning methods in a rainfed winter wheat cropland. Sci. Total Environ. 871, 161967 (2023).

Jung, M. et al. Global patterns of land-atmosphere fluxes of carbon dioxide, latent heat, and sensible heat derived from eddy covariance, satellite, and meteorological observations. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 116, G00J07 (2011).

Jung, M. et al. Scaling carbon fluxes from eddy covariance sites to globe: synthesis and evaluation of the FLUXCOM approach. Biogeosciences 17, 1343–1365 (2020).

Tramontana, G. et al. Predicting carbon dioxide and energy fluxes across global FLUXNET sites with regression algorithms. Biogeosciences 13, 4291–4313 (2016).

Nathaniel, J., Liu, J. & Gentine, P. MetaFlux: Meta-learning global carbon fluxes from sparse spatiotemporal observations. Sci. Data 10, 440 (2023).

Yu, P. et al. Global Pattern of Ecosystem Respiration Tendencies and Its Implications on Terrestrial Carbon Sink Potential. Earths Future 10, e2022EF002703 (2022).

Migliavacca, M. et al. Semiempirical modeling of abiotic and biotic factors controlling ecosystem respiration across eddy covariance sites. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 390–409 (2011).

Davidson, E. A., Savage, K. E. & Finzi, A. C. A big-microsite framework for soil carbon modeling. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 3610–3620 (2014).

Guerschman, J. P. et al. Assessing the effects of site heterogeneity and soil properties when unmixing photosynthetic vegetation, non-photosynthetic vegetation and bare soil fractions from Landsat and MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 161, 12–26 (2015).

Keenan, T. F. et al. Widespread inhibition of daytime ecosystem respiration. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 407–415 (2019).

Kulmala, L. et al. Inter- and intra-annual dynamics of photosynthesis differ between forest floor vegetation and tree canopy in a subarctic Scots pine stand. Agric. For. Meteorol. 271, 1–11 (2019).

Yan, X. & Zhao, J. Establishing and validating individual-based carbon budget model FORCCHN of forest ecosystems in China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 27, 2684–2694 (2007).

Kimball, J. S. et al. A Satellite Approach to Estimate Land–Atmosphere CO2 Exchange for Boreal and Arctic Biomes Using MODIS and AMSR-E. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 47, 569–587 (2009).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (2016).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1705.07874 (2017).

Grinsztajn, L., Oyallon, E. & Varoquaux, G. Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on tabular data? Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2207.08815 (2022).

Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning. (Lulu. com, 2020).

Kim, M., Brunner, D. & Kuhlmann, G. Importance of satellite observations for high-resolution mapping of near-surface NO2 by machine learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 264, 112573 (2021).

Sim, S. & Im, J. Improved Ocean–Fog Monitoring Using Himawari-8 Geostationary Satellite Data Based on Machine Learning With SHAP-Based Model Interpretation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 16, 7819–7837 (2023).

Yan, Y. et al. Climate-induced tree-mortality pulses are obscured by broad-scale and long-term greening. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 912–923 (2024).

Yuan, K. et al. Causality guided machine learning model on wetland CH4 emissions across global wetlands. Agric. For. Meteorol. 324, 109115 (2022).

Runge, J., Nowack, P., Kretschmer, M., Flaxman, S. & Sejdinovic, D. Detecting and quantifying causal associations in large nonlinear time series datasets. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau4996 (2019).

Runge, J., Gerhardus, A., Varando, G., Eyring, V. & Camps-Valls, G. Causal inference for time series. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 487–505 (2023).

Yuan, K. et al. Boreal–Arctic wetland methane emissions modulated by warming and vegetation activity. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 282–288 (2024).

Zhu, W., Zhao, C. & Xie, Z. An end-to-end satellite-based GPP estimation model devoid of meteorological and land cover data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 331, 109337 (2023).

Zhao, C., Zhu, W., Guo, H., Chen, L. & Xie, Z. The impact of Arctic climatic and terrestrial environmental changes on primary industry: A review. Acta Geogr. Sin. 77, 2838–2861 (2022).

Friedl, M. A. et al. MODIS Collection 5 global land cover: Algorithm refinements and characterization of new datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 168–182 (2010).

Chen, J. M. et al. Vegetation structural change since 1981 significantly enhanced the terrestrial carbon sink. Nat. Commun. 10, 4259 (2019).

Chen, J. M. et al. Effects of foliage clumping on the estimation of global terrestrial gross primary productivity. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB1019 (2012).

Walcroft, A. S. et al. Radiative transfer and carbon assimilation in relation to canopy architecture, foliage area distribution and clumping in a mature temperate rainforest canopy in New Zealand. Agric. For. Meteorol. 135, 326–339 (2005).

Xiao, X. et al. Satellite-based modeling of gross primary production in an evergreen needleleaf forest. Remote Sens. Environ. 89, 519–534 (2004).

Waring, R. H., Landsberg, J. J. & Williams, M. Net primary production of forests: a constant fraction of gross primary production?. Tree Physiol 18, 129–134 (1998).

Collalti, A. & Prentice, I. C. Is NPP proportional to GPP? Waring’s hypothesis 20 years on. Tree Physiol 39, 1473–1483 (2019).

He, Y., Piao, S., Li, X., Chen, A. & Qin, D. Global patterns of vegetation carbon use efficiency and their climate drivers deduced from MODIS satellite data and process-based models. Agric. For. Meteorol. 256–257, 150–158 (2018).

Campos, I. et al. Mapping within-field variability in wheat yield and biomass using remote sensing vegetation indices. Precis. Agric. 20, 214–236 (2019).

Box, E. O., Holben, B. N. & Kalb, V. Accuracy of the AVHRR vegetation index as a predictor of biomass, primary productivity and net CO2 flux. Vegetatio 80, 71–89 (1989).

Cahoon, S. M. P. et al. Limited variation in proportional contributions of auto- and heterotrophic soil respiration, despite large differences in vegetation structure and function in the Low Arctic. Biogeochemistry 127, 339–351 (2016).

Hashimoto, S. et al. Global spatiotemporal distribution of soil respiration modeled using a global database. Biogeosciences 12, 4121–4132 (2015).

Gong, Z., Ge, W., Guo, J. & Liu, J. Satellite remote sensing of vegetation phenology: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens 217, 149–164 (2024).

Dronova, I. & Taddeo, S. Remote sensing of phenology: Towards the comprehensive indicators of plant community dynamics from species to regional scales. J. Ecol. 110, 1460–1484 (2022).

Ai, J. et al. MODIS-Based Estimates of Global Terrestrial Ecosystem Respiration. J. Geophys. Res Biogeosci. 123, 326–352 (2018).

Lai, J. et al. Terrestrial photosynthesis inferred from plant carbonyl sulfide uptake. Nature 634, 855–861 (2024).

Zheng, Y. et al. Improved estimate of global gross primary production for reproducing its long-term variation, 1982–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2725–2746 (2020).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2023. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 5301–5369 (2023).

Hu, Z. et al. Decoupling of greenness and gross primary productivity as aridity decreases. Remote Sens. Environ. 279, 113120 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. Evidence for widespread thermal optimality of ecosystem respiration. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1379–1387 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Maximum carbon uptake potential through progressive management of plantation forests in Guangdong Province, China. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 1–9 (2025).

Piao, S. et al. Forest annual carbon cost: a global-scale analysis of autotrophic respiration. Ecology 91, 652–661 (2010).

Yu, G. et al. High carbon dioxide uptake by subtropical forest ecosystems in the East Asian monsoon region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 4910–4915 (2014).

Quinn Thomas, R., Canham, C. D., Weathers, K. C. & Goodale, C. L. Increased tree carbon storage in response to nitrogen deposition in the US. Nat. Geosci. 3, 13–17 (2010).

Bowden, R. D., Davidson, E., Savage, K., Arabia, C. & Steudler, P. Chronic nitrogen additions reduce total soil respiration and microbial respiration in temperate forest soils at the Harvard Forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 196, 43–56 (2004).

Fawcett, D. et al. Declining Amazon biomass due to deforestation and subsequent degradation losses exceeding gains. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 1106–1118 (2023).

Potapov, P., Hansen, M. C., Stehman, S. V. & Loveland, T. R. & Pittman, K. Combining MODIS and Landsat imagery to estimate and map boreal forest cover loss. Remote Sens. Environ. 112, 3708–3719 (2008).

Guindon, L. et al. Missing forest cover gains in boreal forests explained. Ecosphere 9, e02094 (2018).

Commane, R. et al. Carbon dioxide sources from Alaska driven by increasing early winter respiration from Arctic tundra. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 5361–5366 (2017).

Maes, S. L. et al. Environmental drivers of increased ecosystem respiration in a warming tundra. Nature 629, 105–113 (2024).

Kowalczyk, E. A. et al. The CSIRO Atmosphere Biosphere Land Exchange (CABLE) model for use in climate models and as an offline model. CSIRO Mar. Atmospheric Res. Pap. 13, 42 (2006).

Duffy, K. A. et al. How close are we to the temperature tipping point of the terrestrial biosphere?. Sci. Adv. 7, eaay1052 (2021).

Schubert, P., Eklundh, L., Lund, M. & Nilsson, M. Estimating northern peatland CO2 exchange from MODIS time series data. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 1178–1189 (2010).

Wan, Z., Hook, S. & Hulley, G. MODIS/Terra Land Surface Temperature/Emissivity Daily L3 Global 1 km SIN Grid V061. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD11A1.061 (2021).

Myneni, R., Knyazikhin, Y. & Park, T. MOD15A2H MODIS/Terra Leaf Area Index/FPAR 8-Day L4 Global 500 m SIN Grid V006. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD15A2H.006 (2015).

Schaaf, C. & Wang, Z. MODIS/Terra+Aqua BRDF/Albedo Nadir BRDF Adjusted Ref Daily L3 Global - 500 m V061. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD43A4.061 (2021).

Hengl, T. & Wheeler, I. Soil organic carbon content in x 5 g / kg at 6 standard depths (0, 10, 30, 60, 100 and 200 cm) at 250 m resolution. Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2525553 (2018).

Badgley, G., Field, C. B. & Berry, J. A. Canopy near-infrared reflectance and terrestrial photosynthesis. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602244 (2017).

Guerschman, J. P. et al. Estimating fractional cover of photosynthetic vegetation, non-photosynthetic vegetation and bare soil in the Australian tropical savanna region upscaling the EO-1 Hyperion and MODIS sensors. Remote Sens. Environ. 113, 928–945 (2009).

Hill, M. J. & Guerschman, J. P. The MODIS Global Vegetation Fractional Cover Product 2001–2018: Characteristics of Vegetation Fractional Cover in Grasslands and Savanna Woodlands. Remote Sens 12, 406 (2020).

Hill, M. J. & Guerschman, J. P. Global trends in vegetation fractional cover: Hotspots for change in bare soil and non-photosynthetic vegetation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 324, 107719 (2022).