Abstract

Here, we investigate how the Norm Activation Model and Protection Motivation Theory factors shape migration decisions in response to flood risks. Using a cross-sectional survey and convenience sampling, we collected 345 responses, which were analysed utilizing the Smart-Partial Least Squares software. The findings reveal that awareness of environmental consequences influences the sense of environmental responsibility, as well as perceived severity and vulnerability. In turn, environmental responsibility influences self-efficacy and response efficacy. Furthermore, perceived severity and response efficacy influence the migration intentions, and average household income influences the association between response efficacy and migration intentions. Policymakers should focus on improving community resilience by considering socioeconomic factors and individual experiences in disaster risk management. Our study offers insights into the role of socioeconomic and psychological factors in flood-induced migration and contributes to both theoretical development and policymaking for disaster risk management in flood-prone regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Human migration in flood-vulnerable communities

As climate change intensifies the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, human migration has become a critical adaptation strategy for populations in flood-prone areas1. Flooding—particularly in urban regions—poses severe risks such as property damage, livelihood disruption, and displacement, especially where infrastructure is insufficient to manage these challenges2. As global temperatures rise and extreme weather events become more frequent, communities living in flood-prone regions face heightened risks to their safety, livelihoods, and well-being. In Southeast Asia, particularly in regions like Klang Valley, Malaysia, flooding is a recurrent and devastating phenomenon that forces communities to make life-altering decisions, including whether to stay or migrate. Rapid urbanization, high population density, and environmental vulnerabilities have increased flood risks owing to inadequate infrastructure and poor planning3,4. Therefore, migration is not merely an immediate response but a long-term adaptation reflecting community vulnerabilities5,6. However, migration decision is influenced by a complex set of factors, including environmental awareness, socioeconomic conditions, risk perceptions, and past experiences7,8,9,10. Given the urgency of this issue, understanding the factors that influence migration intentions in response to flood risks is critical for developing effective disaster risk management strategies11,12.

While migration in response to flooding has been a subject of interest, there is still a substantial gap in understanding the psychological and socioeconomic factors that drive migration decisions in flood-prone areas. To understand environmental behaviors and responses to threats, the Norm Activation Model (NAM) and Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) have both been widely used, yet their simultaneous application in flood-induced migration intentions remains largely unexplored. While PMT has been applied to investigate human mobility intentions in response to heat in urban Southeast Asia13. Further, study12 examined non-migration decisions in coastal Bangladesh, emphasizing the need to understand how diverse social and environmental contexts shape coping appraisals. Researchers applied PMT to assess flood-coping appraisals, exploring how factors such as social norms and networks influence flood preparedness in Germany and France14. Study employed the theory of planned behavior to understand flood-related adaptive behaviors15. Despite these insights, the existing research has typically analyzed these theories in isolation, overlooking the potential synergies that could enrich our understanding of the interconnections between awareness, responsibility, and efficacy beliefs. No study has integrated NAM with PMT in this context; this study fills that gap by examining how social norms and moral obligations shape non-migration decisions in flood-prone regions. Increased environmental awareness (AEC) acts as a precursor to fostering a stronger sense of environmental responsibility (AER). However, awareness alone does not necessarily elevate risk perception or self-efficacy, underscoring the need for further research on mediating or moderating factors influencing migration behaviors.

Additionally, a notable gap exists within the Malaysian context, where most research on migration intentions has centered on Western16, Asian17,18,19,20, and African21 contexts, with studies specifically focused on Malaysia remaining scarce. Earlier studies examined risk perception and coping strategies among flood victims in the Kuching Division of Sarawak7 and explored migration intentions related to heat13. The study investigated internal migration and urban development in Malaysia using the Migration Potential model, mapping migration distribution in the Klang Valley22. Though studies have touched upon the role of environmental risk perception in migration, these studies have often focused on spatial distribution or specific environmental factors rather than a comprehensive psychological and socioeconomic model13,22. Therefore, the current study is motivated by the need to understand why some Households in Klang Valley choose to migrate in response to flood risks while others choose to remain. This study justifies its exploration of psychological and socioeconomic factors by recognizing that migration decisions are not solely driven by flood risk but are also shaped by individual experiences, environmental awareness, and socioeconomic vulnerabilities11,12. While economic factors such as income and social networks are well-established drivers of migration23,24, the role of environmental awareness in shaping migration intentions remains underexplored. Integrating NAM and PMT provides a perspective on how environmental perceptions and socioeconomic conditions interact to influence migration decisions, highlighting the need for policies that incorporate both psychological insights and economic realities. Accordingly, this study uniquely integrates PMT and NAM to examine how perceived flood severity, self-efficacy, and environmental awareness influence migration intentions. Unlike previous studies that have used these theories independently13,14, this research explores how environmental perceptions and socioeconomic factors interact to shape migration behaviors in flood-prone areas. Additionally, by incorporating moderators such as past flood experience and average monthly income, this study provides a more nuanced understanding of how personal history and economic resources influence migration decisions in the context of flood risks.

The roles of past flood experience and average monthly income as moderators in the migration intention framework represent additional gaps in the literature. Although past experiences are recognized as influential in shaping environmental behaviors25, the specific mechanisms by which individual flood experiences affect migration intentions remain underexplored. Economic conditions, including income levels, meaningfully influence migration decisions, with higher average incomes in destination countries serving as a pull factor for potential migrants23,24. Yet, the impact of average monthly income on response efficacy and migration decisions requires further investigation. While the literature has acknowledged the influence of environmental experiences and economic factors on migration intentions, the specific mechanisms and interactions among these variables warrant a more in-depth examination. Understanding how past flood experiences and average monthly income serve as moderators in the migration intention framework can provide valuable insights for both policymakers and researchers. This study highlights the importance of a nuanced understanding of how socioeconomic conditions and lived experiences shape responses to flood risks, thereby extending current theoretical models and advancing the discourse on migration intentions. Accordingly, the main objectives of this study are:

-

To examine how psychological and socioeconomic factors influence flood-induced migration intentions.

-

To explore the moderating roles of past flood experience and average monthly income in shaping these migration intentions.

This study contributes to the literature by offering an integration of PMT and NAM to explain flood-induced migration intentions, an area that has not been extensively explored in existing research. By integrating psychological and socioeconomic factors, this study offers a comprehensive model that can inform policy and disaster management strategies. It also provides empirical evidence from Klang Valley, Malaysia, where studies on migration decisions in response to flood risks are scarce. Additionally, the important mediating pathways discovered in this study—particularly how AEC influences human migration intention (HMI) through intermediary constructs such as a sense of AER and response efficacy—underscore the cascading effects of environmental perceptions on migration behavior. These findings emphasize the importance of awareness, responsibility, and response efficacy, which suggests that migration decisions are driven by a combination of these factors rather than vulnerability alone. The findings will contribute to the development of adaptive migration strategies, helping policymakers design more effective interventions to address the challenges posed by climate-induced migration in flood-prone areas.

Summary of literature

The literature on flood-induced migration and environmental behavior has grown over the past few years, encompassing an array of psychological, socioeconomic, and environmental determinants. To understand this phenomenon, we conducted a comprehensive literature review, and the results are presented in the Supplementary Information Table S1. According to the findings, several studies have used PMT to explain how flood risk perceptions affect protective actions, such as migration decisions. Study revealed that individuals who perceived higher flood severity were more likely to engage in flood preparedness26, whereas perceived severity and self-efficacy were essential predictors of pro-environmental behavior27. Study investigates migration and displacement triggered by floods in the Mekong Delta, focusing on how environmental factors such as flood risk interact with local vulnerabilities and socioeconomic conditions to drive migration28. Earlier studies supported this by showing that individuals who have had past experiences with flooding are more vulnerable to perceiving future flood risks as severe, thus prompting protective actions such as migration29. Thus, the shaping effect of flood experience on risk perceptions and subsequent behavior is a dominant theme in literature.

Studies examined the role of environmental awareness and personal responsibility in pro-environmental behavior, citing how NAM explains the activation of personal norms for taking action30,31. Findings revealed that place attachment and social norms can effectively inhibit migration in hazard-prone areas31. However, unlike the earlier studies30,31, our study expands the scope of NAM by linking environmental awareness directly to migration intentions rather than to environmental actions such as recycling or local adaptation. Studies emphasize that economic resources, especially income, are fundamental determinants of migration decisions under environmental risk11,32. Findings revealed that individuals with higher incomes are more likely to migrate because they can afford to move to safe locations from high-risk areas, but the less wealthy may face major migration constraints, even if they perceive high flood risks32. In contrast, studies focused on social vulnerabilities and community-level interventions, showing how social and political processes influence migration behavior1,33. A study explored the role of place, out-migration, and community factors on disaster preparedness in flood-prone villages in Northwest China34. While such literature stresses the function of government support and community resilience in facilitating migration, it neglects the direct function of economic resources in migration choices, which is central to our study.

In addition, past flood experience has been proven to be a moderating factor in migration choice. Studies have shown that prior experience of floods considerably affects the way individuals assess future threats, and that individuals who have previously experienced severe floods are more likely to migrate when faced with the same threat26,29. Our study incorporates previous flood experience as a moderating variable, developing this literature and consolidating it by linking it with the psychological processes represented by PMT and NAM. Additionally, family income plays an important role in the feasibility of migration. The suggestion that income is a substantial moderator of migration decision is augmented by earlier studies11,32, where individuals with higher income are more likely to migrate, provided economic means. However, the moderating role of income in flood-risk perceptions and migration intentions has been explored less from the viewpoint of psychological theories, which is precisely the gap our study is about to address.

While the research studies are in consensus on several aspects, there are notable disparities in the direction of research. Specifically, psychological factors (e.g., perceived severity, vulnerability, and self-efficacy) are emphasized26,27, although these works explicitly address protective behaviors (e.g., flood preparedness) and not migration decisions. Our study fills this gap by examining how these factors influence migration intentions. While studies focus on social vulnerabilities and communal dimensions33, our study places greater focus on individual-level dimensions, such as economic resources and prior flood experience, which are often relegated to the margins of studies dealing with more social resilience or communal-oriented interventions. Most of the existing literature has examined economic and social vulnerabilities independently32, while our study differs by integrating psychological variables with socioeconomic variables (e.g., income and experience of flood) to provide an overarching explanatory model of migration behavior induced by floods. Our study contributes to the literature by integrating the PMT and NAM to explain flood-induced migration. Although previous studies have dealt with flood preparedness and adaptive behaviors, migration has seldom been explained by the collective framework of psychological theories. By incorporating flood-risk perceptions, personal responsibility, and socioeconomic moderators (e.g., previous flood experience and income), our study explains in greater depth what affects migration decisions in flood-risk areas.

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

This study offers a comprehensive explanation of the factors driving HMI in flood-prone areas by integrating NAM and PMT. NAM helps explain how moral considerations and personal norms motivate individuals to take action, while PMT highlights the cognitive and emotional processes that lead Households to assess flood risks and respond by migrating. Together, these theories capture both the moral and rational dimensions of migration decision-making, providing a holistic understanding of why Households in Klang Valley may choose to leave flood-prone areas.

The NAM serves as a theoretical framework for understanding pro-environmental behavior. It emphasizes the role of personal norms in motivating individuals to act in ways that benefit the environment35. The model posits that personal norms—defined as internalized standards of behavior that reflect an individual’s moral obligations—are crucial in determining whether individuals engage in prosocial actions, such as recycling or reducing energy consumption27,36,37. Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of the NAM across various contexts, including recycling, energy conservation, tourism, and agriculture. For instance, integrating NAM with the theory of planned behavior identified that personal norms—along with attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control—influence recycling intentions38. Similarly, a sense of moral obligation is a key driver for energy-saving practices36,37. In tourism, personal norms influenced tourists’ adoption of sustainable practices39. In agriculture, the NAM highlighted the role of personal norms in ethical decision-making related to environmental sustainability40,41. However, the NAM provides a robust framework for understanding the psychological mechanisms that underlie pro-environmental behavior. By focusing on the activation of personal norms, the NAM elucidates how awareness of consequences and a sense of responsibility can motivate individuals to act in environmentally beneficial ways. This model not only enhances our understanding of individual behavior but also informs the design of interventions aimed at promoting sustainable practices across various sectors.

Central to the NAM are three key constructs: AEC, AER, and personal norms. AEC refers to an individual’s understanding of the negative outcomes that may arise from inaction, while AER involves recognizing one’s role in contributing to these consequences36,42. When individuals are aware of the adverse effects of their actions and feel a sense of responsibility, they are more likely to activate their personal norms, which in turn motivates them to engage in pro-environmental behaviors27,30,43. This activation of personal norms is often seen as a moral obligation, leading individuals to prioritize collective interests over self-interest37,44.

AEC positively influences AER. This hypothesis posits that heightened awareness of environmental issues, such as the impacts of climate change and natural disasters, fosters a sense of responsibility among individuals. Individuals who recognize the severity of environmental degradation are more likely to engage in proactive behaviors, including migration from high-risk areas11,45. For instance, awareness of environmental risks can lead to increased community engagement in mitigation efforts, which suggests a direct correlation between AEC and AER11. Furthermore, individuals who feel responsible for their environment are more inclined to consider migration as a viable adaptation strategy when faced with environmental threats31,46.

AEC positively influences perceived severity. This hypothesis suggests that individuals who are more informed about environmental risks perceive these threats as more severe. Empirical evidence has supported this notion, demonstrating that awareness of climate-related hazards impacts how individuals assess the risks associated with environmental changes, such as flooding47,48. For example, individuals living in flood-prone areas who understand the potential for severe flooding are more likely to view such events as critical threats, thereby increasing their migration intentions29,48. This perception of severity can act as a catalyst for migration as individuals seek to protect themselves and their families from imminent dangers11.

AEC positively influences perceived vulnerability. This hypothesis asserts that increased AEC leads individuals to perceive themselves as more vulnerable to these threats. When individuals in vulnerable regions are informed about the environmental factors contributing to their risks, such as climate change and natural disasters, they often report a heightened sense of personal vulnerability29,49. This perceived vulnerability can influence migration intention as individuals may view relocation as a necessary step to enhance their safety and reduce exposure to environmental hazards31,46. The interplay between awareness and perceived vulnerability underscores the importance of education and information dissemination in shaping migration behaviors in response to environmental changes50. Based on the above explanation, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1-3. Awareness of environmental consequences positively influences ascription of environmental responsibility, perceived severity, and perceived vulnerability.

AER encapsulates the degree to which individuals perceive themselves as responsible for environmental issues, including flooding. This perception can enhance their self-efficacy, which refers to their belief in their ability to effectively manage and respond to these environmental challenges. When individuals acknowledge their role in environmental degradation, they are more likely to develop a proactive approach to mitigating these issues, thereby increasing their self-efficacy51,52. For instance, communities that integrate local knowledge into flood risk management not only enhance their understanding of flood dynamics, but they also empower individuals to take actionable steps, thereby reinforcing their self-efficacy52. Moreover, acknowledging personal responsibility often leads to a greater belief in one’s capabilities to enact change, which is a core component of self-efficacy. Households that feel a sense of responsibility toward their environment are likely to engage in preparedness measures, such as creating emergency plans or considering relocation to safer areas. This proactive behavior is rooted in their belief that they possess the necessary skills and resources to effectuate change51,53. The literature has supported this notion, suggesting that self-efficacy is a critical factor in motivating individuals to engage in behaviors that mitigate environmental risks, including migration as a response to flooding53.

In addition to self-efficacy, AER also positively influences response efficacy, which pertains to individuals’ beliefs regarding the effectiveness of their actions in addressing environmental threats. When Households in flood-prone areas accept responsibility for environmental consequences, they are more likely to trust that their actions—be it migration or community-based adaptation strategies—will yield positive outcomes54,55. This belief in the effectiveness of their responses is crucial as it motivates individuals to take the necessary actions to protect themselves and their families from flooding risks. Individuals who perceive their actions as effective are more inclined to engage in proactive behaviors, such as seeking out effective solutions to mitigate flood impacts54. Thus, the interplay between AER and response efficacy is vital in shaping the intentions of Households to migrate or adapt in response to environmental challenges. Accordingly, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H4-5. Ascription of environmental responsibility positively influences self-efficacy and response efficacy.

PMT primarily focuses on how individuals respond to fear-inducing information and how this influences their health-related behaviors56. This theory posits that when individuals perceive a considerable threat to their health, they engage in a cognitive appraisal process that leads to protective motivation. This motivation is influenced by two main components: threat appraisal and coping appraisal. Threat appraisal involves perceived severity and vulnerability to a threat, while coping appraisal focuses on the perceived efficacy of the recommended protective behavior and the individual’s self-efficacy in performing that behavior57,58.

Research has demonstrated the broad applicability of PMT across health and other behavioral contexts. PMT has been effective in predicting protective behaviors against diseases, such as schistosomiasis among adolescents59 and skin cancer across populations60,61. Constructs such as self-efficacy, response efficacy, and perceived response costs are key predictors of these behaviors. For instance, these constructs influenced sun protection behaviors among students62. PMT-based interventions have also successfully increased protective behaviors against skin cancer in diverse groups, including farmers and students60,63. This theory is effective in public health campaigns by combining threat severity with actionable advice58,61. Beyond health, PMT has been adapted for emerging issues, such as COVID-19 prevention64, and applied in organizational settings to understand compliance with information security policies65,66, which illustrates its versatility across disciplines. However, PMT provides a robust framework for understanding and predicting health-related behaviors in response to perceived threats. Its constructs facilitate the development of targeted interventions that can effectively promote protective behaviors across diverse populations and contexts.

PMT posits that individuals’ decisions to engage in protective behaviors are influenced by their appraisals of threats and coping strategies. This framework is particularly relevant in understanding how psychological factors such as perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, self-efficacy, response efficacy, and response cost shape migration intentions in the context of environmental threats such as flooding. Individuals who perceive flood risks as severe are more likely to consider migration aligns with PMT, which suggests that heightened awareness of potential losses can trigger protective intentions. When individuals recognize the severity of a threat, they are more likely to adopt protective behaviors, including migration67. However, this relationship may be moderated by external factors such as economic resources and support systems. For instance, even if individuals perceive a high risk, a lack of financial means or social support can hinder their ability to act on these intentions33,68. Thus, while perceived severity is a critical driver of HMI, it must be contextualized within the broader socioeconomic landscape.

A heightened sense of vulnerability to flooding, increasing migration intention is supported by PMT, which emphasizes the role of personal appraisal in motivating protective actions12. Individuals who feel their household or community is susceptible to flood events often experience increased urgency to relocate. Nonetheless, cultural and socioeconomic factors can complicate this relationship. For example, individuals may feel vulnerable yet choose to stay due to strong attachments to their land or community ties, which highlights the multi-dimensional nature of vulnerability12. This complexity underscores the need for interventions that consider both psychological and cultural dimensions of vulnerability.

Individuals with high self-efficacy regarding migration logistics are more inclined to migrate is consistent with PMT, which posits that self-efficacy influences the translation of risk perception into action69. Individuals who believe in their ability to manage the challenges associated with migration are more likely to act on their intentions. However, high self-efficacy alone may not suffice if external barriers, such as restrictive migration policies or financial constraints, exist33,68. Therefore, understanding self-efficacy in conjunction with structural realities is crucial for fostering adaptive migration behaviors.

Likewise, individuals being more likely to migrate if they believe it will effectively reduce flood risks is central to PMT. Response efficacy serves as a bridge between threat recognition and protective behavior70. Individuals who perceive migration as a viable solution to mitigate flood risks are more likely to consider it. However, this perception can be influenced by prior experiences, community narratives, and media portrayals, which can either enhance or diminish the belief in migration’s effectiveness12. This dynamic nature of response efficacy necessitates targeted communication strategies that highlight successful migration stories and effective coping strategies.

Perceived costs associated with migration deterring individuals from intending to migrate, even when they acknowledge flood risks, is well supported by PMT. High perceived costs—whether financial, social, or emotional—can act as considerable barriers to protective action33,70. However, these costs are often subjective and influenced by social networks and community ties. For instance, strong community support can mitigate perceived costs, while isolation can exacerbate them33,68. Therefore, interventions should aim to address these subjective dimensions of response cost to facilitate adaptive migration. Here are the hypothesis statements related to the PMT constructs:

H6. Perceived severity positively influences flood-induced human migration intention.

H7. Perceived vulnerability positively influences flood-induced human migration intention.

H8. Self-efficacy positively influences flood-induced human migration intention.

H9. Response efficacy positively influences flood-induced human migration intention.

H10. Response cost negatively influences flood-induced human migration intention.

The relationship between past flood experience, average monthly income, and flood-induced HMI is complex and multifaceted. Past flood experiences influence individuals’ psychological responses to flood risks, which in turn affect their migration intentions. Individuals with severe past flood experiences often exhibit heightened perceptions of flood severity and vulnerability, which can intensify their migration intentions. For instance, study found that individuals with more substantial flood experience are more likely to recognize the potential devastation floods can cause, leading to increased migration intentions due to heightened risk awareness71. This aligns with the earlier findings72 noted that severe flood events enhance people’s awareness of flooding risks, thereby influencing their decision-making processes regarding migration. Conversely, past flood experiences can also bolster self-efficacy and response efficacy, potentially reducing migration intentions. Individuals who have successfully navigated previous flooding events may develop a stronger belief in their ability to cope with future floods, thereby decreasing their likelihood of migrating. This phenomenon highlighted that resilience-building efforts often take precedence over migration in the aftermath of severe flooding, particularly among those who have experienced such events73. Moreover, the interplay between self-efficacy and response efficacy is crucial; individuals who feel capable of responding effectively to flood risks may be less inclined to migrate as they believe they can manage the situation without relocating74.

On the economic front, average monthly income serves as a critical moderator in the relationship between response efficacy, response cost, and HMI. Higher income levels can amplify the influence of response efficacy by providing individuals with the necessary resources to act on their migration intentions. For instance, individuals with higher average monthly income may have greater access to financial resources that facilitate relocation, thereby increasing their likelihood of migrating in response to perceived flood risks1. In contrast, those with lower incomes may face heightened perceived response costs, which can deter migration despite an awareness of the risks. This dynamic is illustrated that financial constraints impact individuals’ preparedness and willingness to act in the face of flood risks26. Integrating socioeconomic and experiential factors is essential for understanding the intricate decision-making processes behind human migration in flood-prone areas. The interplay between past flood experiences and economic resources shapes individuals’ perceptions of risk and their subsequent actions. Community resilience and the capacity for self-organization play vital roles in determining migration outcomes, particularly in areas frequently affected by flooding32. Accordingly, we illustrate the associated hypotheses as follows:

H11-14. Past (flood) experience interacts to moderate the relationship of perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, self-efficacy, and response efficacy with flood-induced human migration intention.

H15-16. Average monthly income interacts to moderate the relationship of response efficacy and response cost with flood-induced human migration intention.

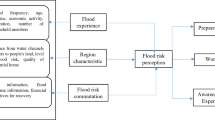

All associations hypothesized above are presented in Fig. 1 below.

Conceptual framework proposes that AEC influences AER (H1), perceived severity (H2), and perceived vulnerability (H3). Ascription of responsibility subsequently affects both self-efficacy (H4) and response efficacy (H5). These cognitive assessments then drive HMI through perceived severity (H6), vulnerability (H7), self-efficacy (H8), response efficacy (H9), and cost (H10). The framework highlights two key moderators: past flood experience (H11-14) and average monthly income (H15-16), shown by dotted arrows.

Results

Demographic details

As presented in Supplementary Information Table S2, the respondents are predominantly young, with the majority falling into the 26–35 age group (30.7%) and a notable presence in the 18–25 bracket (19.4%), reflecting a working-age population that may be more actively engaged in household decisions and community preparedness. The group is moderately educated, with 39.1% holding a diploma or technical school certificate and 28.1% having a secondary school education; this suggests that most are not highly specialized in fields that might involve advanced technical knowledge of flood risks. Employment levels are high, with 64.1% working full-time; this indicates a population that may face challenges balancing work commitments with flood preparedness efforts, particularly in lower-income brackets where resources for mitigation may be limited. The nearly even gender distribution and concentration of respondents in the 26–35 age range highlight a working-class group, likely active in household decision-making regarding flood preparedness. A considerable portion of the respondents (61.4%) earn below RM4000, which may limit their financial ability to invest in effective flood mitigation measures, making them more vulnerable to flood-related damages. Educational attainment is skewed toward diploma or secondary school qualifications, with only a small percentage holding a bachelor’s or higher degree; this suggests that this group may not possess the technical knowledge needed to fully understand and mitigate flood risks, which emphasizes the need for more targeted educational interventions. Most respondents have experienced flooding at least once in the past five years, with 67% reporting personal or property loss, particularly in vehicles and furniture; this reflects the substantial economic impact of flooding on these Households. However, despite this experience, gaps in flood preparedness and confidence remain. While 46.4% claim to know what to do in the event of a flood, a substantial number of respondents are either unsure or unprepared, which points to the need for enhanced public education on flood-response strategies. Additionally, although the majority are aware of living in flood-prone areas, nearly 38% are not, which indicates a serious gap in flood risk awareness. Low levels of community engagement further compound this issue, with only 16.5% actively involved in flood-mitigation efforts. This highlights the urgent need for stronger community-based programs and initiatives that can foster collective resilience. Despite the high level of concern about flood risks, as shown by 64.9% of respondents, the remaining portion exhibits neutrality or indifference, possibly owing to desensitization from repeated flood events or a lack of understanding of the risks.

Measurement model

The study’s evaluation of reliability and validity yielded robust results. For internal consistency, all constructs demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability. As shown in Table 1, Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.7 for all variables, with the lowest value being 0.715 for perceived severity, indicating a strong internal coherence within the model75. The highest Cronbach’s alpha was observed for the response efficacy construct at 0.925. Furthermore, composite reliability values for each construct also surpassed the recommended minimum of 0.7, with the lowest being 0.823 for perceived severity, confirming the model’s overall reliability75.

In terms of convergent validity, the average variance extracted for all constructs exceeded the benchmark of 0.5, which indicates that a substantial proportion of variance is explained by the constructs rather than by the measurement error75. Average variance extracted values ranged from 0.511 for AEC to 0.769 for past flood experience, demonstrating that the latent variables are unidimensional.

We verified discriminant validity using the Fornell-Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio. The square root of average variance extracted values exceeded the correlations between constructs (Supplementary Information, Table S3), supporting adequate discriminant validity76. Additionally, the Heterotrait-Monotrait values were below the threshold of 0.85 for all constructs (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1), confirming that the constructs are distinct and measuring different concepts75. Finally, item loadings for all constructs exceeded 0.5 (as presented in Supplementary Information, Fig. S2, and Table S3), reinforcing the model’s convergent validity. All items loaded more strongly on their respective constructs than on others, indicating high convergent effectiveness for reflective models. These outcomes confirming that the model demonstrates both reliability and validity. Furthermore, the variance inflation factors presented in Supplementary Information Table S4 confirm the absence of multicollinearity issues75.

Structural model

The results of the path analysis in Fig. 2 and Table 2 reveal the critical influence of environmental awareness and ascription of responsibility on migration intentions in flood-prone regions. Specifically, H1, which posits that AEC positively influences AER, is supported (β = 0.427, t = 9.853, p < 0.001). Similarly, H2 and H3, the effects of AEC on perceived severity (β = 0.184, t = 3.005, p < 0.001) and vulnerability (β = 0.149, t = 2.616 p < 0.01) are supported. Hypotheses H4 and H5, examining the relationship between AER and self-efficacy as well as response efficacy, are also supported, but with varying strengths. AER’s effect on response efficacy (β = 0.236, t = 4.139, p < 0.001) is notably stronger compared to its impact on self-efficacy (β = 0.103, p < 0.05). Hypothesis H6, which proposes that perceived severity positively impacts HMI, is supported (β = 0.259, t = 4.492, p < 0.001). However, hypothesis H7, addressing the influence of perceived vulnerability on HMI, is not supported (β = 0.008, t = 0.115, p > 0.05). Similarly, hypothesis H8, which examines the effect of self-efficacy on HMI, is also not supported (β = 0.085, t = 1.420, p > 0.05). Nonetheless, hypothesis H9, which posits that response efficacy positively affects HMI, is supported (β = 0.172, t = 2.902, p < 0.01). Finally, hypothesis H10, examining the impact of response cost on HMI, is not supported (β = 0.013, t = 0.285, p > 0.05).

Conceptual framework with findings shows that AEC influences AER (0.427***), perceived severity (0.184**), and perceived vulnerability (0.149**). Ascription of responsibility subsequently affects both self-efficacy (0.103**) and response efficacy (0.236***). These cognitive assessments then drive HMI through perceived severity (0.259***), vulnerability (not significant), self-efficacy (not significant), response efficacy (0.172**), and cost (not significant). The framework highlights two key moderators: past flood experience (not significant) and average monthly income (H15. −0.129*; H16. not significant), shown by dotted arrows. Path coefficients are shown with their significance levels: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (two-tailed tests). Non-significant paths are labeled NS (p ≥ 0.05).

The analysis of the moderating effects in Table 2 reveals important insights into the dynamics of flood-induced HMI. The direct association between past flood experience and HMI (β = 0.239, t = 2.829, p < 0.01) is positive and statistically significant. However, hypotheses H11–H14, which explore the moderating effects of past flood experience on the relationships between perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, self-efficacy, response efficacy, and HMI, are not supported. As for the direct association between average monthly income and HMI, it is positive and statistically significant. The moderating effect of average monthly income on response efficacy and HMI (H15. β = −0.129, t = 1.711, p < 0.05) is negative and statistically significant (Slop analysis presented in Fig. 3), indicating that the higher average monthly income weakens the association between response efficacy and HMI. However, the moderating effect of average monthly income on response cost and HMI (H16) is not statistically significant.

The analysis of indirect effects reveals several significant mediation pathways that illustrate the complex relationships influencing HMI in flood-prone areas. Specifically, the pathway from AEC to HMI through AER and response efficacy is significant (β = 0.017, t = 2.274, p = 0.012). This indicates that increased environmental awareness and a sense of responsibility enhance perceptions of effective responses, which in turn influence migration intentions. The pathway from AEC to response efficacy through AER (β = 0.101, t = 3.613, p < 0.001) and from AEC to self-efficacy via AER (β = 0.044, t = 1.752, p = 0.040) further supports the role of AER in shaping response perceptions and individual efficacy. Moreover, AER’s influence on HMI through response efficacy is also significant (β = 0.041, t = 2.399, p = 0.008), which highlights that a sense of responsibility coupled with confidence in response measures plays a vital role in driving migration intentions. Lastly, AEC’s influence on HMI via perceived severity is significant (β = 0.048, t = 2.704, p = 0.003). It implies that a stronger desire to move has taken shape due to the realization of the consequences of living in a high-risk area.

Coefficient of determination and the effect size

This study assessed the structural model’s effectiveness in explaining the phenomena under investigation, using the coefficient of determination (R²) as the primary measure of the model’s explanatory power. R² values provide an indication of explanatory capability, with thresholds of 0.75, 0.5, and 0.25 denoting substantial, moderate, and weak explanatory power, respectively75. The results of the structural model, as presented in Table 2, demonstrate a range of explanatory powers for different constructs. The coefficient of determination (R²) indicates that the model provides moderate explanatory power for HMI and related outcomes such as AER, response efficacy, and perceived severity. While the R² for HMI suggests that the model captures key factors such as perceived severity, response efficacy, and moderating variables such as past flood experience and average monthly household income, it also highlights the potential for including additional variables, such as psychological or social factors, to enhance predictive power. The f² effect sizes reveal medium to large effects for perceived severity and response efficacy on HMI, which emphasizes their central role in influencing migration decisions. In contrast, the smaller f² for perceived vulnerability and self-efficacy aligns with their limited contribution to the variance in migration intentions.

Predictive assessment

The PLS Predict analysis (presented in Supplementary Information Table S5) reveals that most indicators demonstrate satisfactory predictive relevance, as indicated by positive Q² values, suggesting the model’s capacity to predict the endogenous constructs. For instance, AER and HMI indicators show moderate to high Q² values, indicating that AER and flood-induced HMI are well predicted by the model. The comparison between PLS-SEM and other models (Indicator Average and Linear Model) highlights the superior performance of PLS-SEM in predicting constructs such as AER and HMI, with statistically significant differences in average loss values. The PLS-SEM demonstrates lower Root Mean Square Error and Mean Absolute Error values for several constructs (e.g., AER and response efficacy) compared to Indicator Average and Linear Model, confirming its enhanced predictive accuracy. However, some constructs, such as self-efficacy, show minimal or non-significant differences between models, indicating areas for further refinement. Overall, these findings validate the PLS-SEM model as an effective tool for predicting HMI in flood-prone areas, while also highlighting the need for continued improvement in specific constructs to further enhance its predictive power.

Discussions

The statistical findings of this study provide a comprehensive analysis of how environmental awareness and perceptions of responsibility influence flood-induced HMI. The results underscore several key relationships and offer critical insights into the underlying psychological and socioeconomic dynamics affecting migration decisions.

The significant and strong relationship between AEC and AER (H1) suggests that individuals who are more aware of the environmental impact of floods are more likely to perceive themselves as responsible for addressing these challenges. The result is consistent with previous studies11,45, underscoring that heightened environmental awareness tends to amplify the sense of personal responsibility. However, while AEC positively influences perceptions of perceived severity and vulnerability, the effects are moderate (β = 0.184 for perceived severity, β = 0.149 for vulnerability). This finding suggests that although awareness is a necessary condition for increasing responsibility, it may not be sufficient to significantly alter risk perceptions regarding floods.

Regarding hypotheses H2 and H3, the effects of AEC on perceived severity and vulnerability, respectively, the relatively modest beta values indicate that while awareness can prompt a sense of responsibility, it does not necessarily translate into heightened perceptions of severity or vulnerability. This highlights the complexity of environmental risk perception, suggesting that additional psychological or contextual factors might mediate or moderate these relationships. For instance, personal flood experience or socioeconomic factors could influence how individuals perceive the severity and vulnerability associated with flood risks, independent of their environmental awareness. Therefore, while hypotheses H2 and H3 are partially supported29,31,46, the results emphasize the need for a more nuanced understanding of how awareness translates into risk perceptions.

The significant associations between AER and self-efficacy (H4) as well as AER and response efficacy (H5) indicate that individuals who perceive themselves as responsible are more likely to believe they can effectively respond to flood risks, which aligns with the previous literature51,53,54, suggesting that responsibility enhances confidence in taking action. However, the relatively modest effect on self-efficacy suggests that while a sense of responsibility may enhance efficacy beliefs, it does not significantly boost one’s self-perception of their ability to act. This could be due to the complex nature of flood preparedness, which may require resources and skills beyond an individual’s perceived capacity, thus limiting their sense of self-efficacy despite their responsibility perception.

The analysis of factors affecting HMI reveals that certain psychological variables play a more substantial role in influencing migration decisions in flood-prone regions than others. Specifically, hypothesis H6, which proposes that perceived severity positively impacts HMI, is supported (β = 0.259, t = 4.492, p < 0.001). The strong and significant effect suggests that when individuals perceive the severity of floods as high, they are more likely to consider migration as a viable option to mitigate risk. This aligns with the existing literature highlighting that heightened risk perception drives proactive behavior, such as relocation, to avoid potential hazards33,68. However, while perceived severity significantly influences HMI, it represents just one dimension of the risk perception spectrum; this implies that severity alone may not encapsulate the full complexity of migration decisions.

Hypothesis H7, addressing the influence of perceived vulnerability on HMI, is not supported (β = 0.008, t = 0.115, p = 0.454). The non-significant relationship suggests that perceiving oneself as vulnerable to floods does not necessarily translate into an increased intention to migrate. This finding indicates that while individuals may recognize their exposure to risks, it does not always prompt them to take decisive actions such as migration. This outcome diverges from that of previous studies12, which prompts a need to explore why vulnerability perceptions do not trigger migration intent. Possible explanations could include a reliance on adaptive strategies, resilience factors, or an underestimation of flood risks despite acknowledged vulnerability.

Similarly, hypothesis H8, which examines the effect of self-efficacy on HMI, is also not supported (β = 0.085, t = 1.420, p = 0.078). The lack of a significant effect implies that confidence in one’s ability to handle flood-related challenges does not significantly influence migration decisions. While individuals may feel capable of taking actions to manage flood risks, this self-assurance does not necessarily translate into an inclination to relocate. The result highlights a potential gap in the literature where self-efficacy, despite its prominence in behavior change theories33,68, may not be as influential in contexts where external factors such as financial constraints, community ties, or governmental support systems play a larger role in migration decisions.

Hypothesis H9, which posits that response efficacy positively affects HMI, is supported (β = 0.172, t = 2.902, p = 0.002). This significant relationship indicates that individuals who believe in the effectiveness of available responses to flood risks are more likely to consider migration as a practical option. Although the effect is moderate, it emphasizes the importance of confidence in flood response measures and their potential to influence migration behavior. This finding supports previous research12 that links the perceived effectiveness of protective measures to increased willingness to undertake substantial behavior changes, such as migration. However, the moderate effect size suggests that while response efficacy plays a role, it may need to be reinforced by other factors such as social support or financial assistance to drive higher migration intentions.

Finally, hypothesis H10, examining the impact of response cost on HMI, is not supported (β = 0.013, t = 0.285, p = 0.388). The non-significant effect implies that perceived costs associated with migration or other response actions do not significantly deter individuals from migrating, contrary to the past studies33,68. This may suggest that in flood-prone regions such as Klang Valley, Malaysia, the decision to migrate is not heavily influenced by the perceived financial or social costs. Individuals may prioritize safety and long-term well-being over short-term costs, or they may be less sensitive to these costs owing to existing mitigation plans or government support.

The analysis of the moderating effects reveals important insights into the dynamics of flood-induced HMI. The direct association between past flood experience and HMI (β = 0.239, t = 2.829, p = 0.002) is positive and statistically significant. This result indicates that individuals with prior flood experiences have heightened migration intentions when they perceive floods as severe. This finding supports the notion that lived experiences reinforce the perceived threat, making individuals more likely to take proactive measures such as migration when they anticipate future risk. It highlights the critical role of experience-based knowledge in shaping behavioral responses to environmental threats, which may be more effective than information-based approaches alone.

Nonetheless, the non-significant moderation effects (HM11-HM14) suggest that while past flood experience strengthens the relationship between perceived severity and HMI, it does not significantly alter the effects of other psychological factors on migration decisions. This indicates that past experiences may be more critical in enhancing the salience of perceived severity than other psychological dimensions. Such results challenge existing theoretical models that assume uniformity in how past experiences interact with different psychological factors, which suggests that the influence of past experiences may be selective or context-specific.

Hypothesis H15, which examines the moderating effect of average monthly income on the relationship between response efficacy and HMI (presented in Table 2 and Fig. 3), is partially supported (β = −0.129, t = 1.711, p = 0.044). The negative moderation effect indicates that higher-income Households may be less inclined to migrate even if they believe in the effectiveness of flood response measures. This suggests that economic stability provides resources or alternatives that may reduce the urgency to migrate. Wealthier Households may have access to adaptive measures, such as reinforcing their homes or relocating temporarily, without committing to permanent migration. This finding highlights the crucial role of socioeconomic factors in moderating migration intentions and suggests that theoretical models must account for economic stability as a critical determinant influencing the migration decision-making process.

However, average monthly income does not significantly moderate the relationship between response cost and HMI (β = −0.011, t = 0.179, p = 0.429). This non-significant effect (H16) implies that the perceived costs associated with migration or other flood response actions do not vary substantially across income levels. This finding may indicate that, regardless of economic standing, individuals weigh the benefits and costs of migration similarly; this suggests that other factors, such as social networks or government support, might play more substantial roles in migration decisions than individual financial capacity alone. However, the decision to focus on the moderation of response efficacy and response cost was driven by previous studies, the understanding of the local research team, and input from grant examiners, particularly in relation to our theoretical framework, the PMT. In PMT, response efficacy and response cost are central to the decision-making process regarding protective behaviors, including migration decisions.

The findings of the indirect effect underscore the critical roles of environmental awareness and responsibility in indirectly influencing migration behavior. The significant pathway from AEC to HMI through AER and response efficacy indicates that increased environmental awareness and a sense of responsibility enhance perceptions of effective responses, which in turn influence migration intentions. The pathway from AEC to response efficacy through AER further supports the role of AER in shaping response perceptions and individual efficacy. Moreover, the significant influence of AER on HMI through response efficacy highlights that a sense of responsibility coupled with confidence in response measures plays a vital role in driving migration intentions. However, the insignificant pathways, for example, the pathway from AEC through vulnerability to HMI, indicate that while environmental awareness and responsibility perceptions are vital, vulnerability alone may not be sufficient to influence migration decisions.

Theoretical contributions

This study makes several significant theoretical contributions to the body of migration intentions as a response to environmental risks, particularly flood-prone areas. First, it contributes to the integration of the NAM and PMT, two well-established theories of environmental actions, through joint implementation in the context of flood-induced migration. Although these models have been applied independently to examine environmental actions and responses to threats at large, their joint application in the specific instance of migration intentions has been substantially under-researched. This study provides a more unified view of how individual perceptions of environmental risks and activation of normative motivations influence migration decisions.

The findings contribute to the theoretical understanding of environmental behavior by reinforcing the interconnectedness of awareness, responsibility, and efficacy beliefs. The significant relationship between AEC and AER supports the notion that increased environmental awareness is a fundamental precursor to fostering a stronger sense of environmental responsibility; this suggests that interventions aimed at enhancing responsibility should focus primarily on raising awareness. This study extends existing theories by demonstrating that awareness does not directly translate into higher risk perceptions or self-efficacy, which implies the presence of mediating or moderating factors.

The findings associated with the factors affecting HMI challenge and refine existing theoretical models of migration intention by highlighting the varying roles of psychological factors. The considerable influence of perceived severity and response efficacy underscores their importance in shaping migration behavior, suggesting that these factors may be more central than previously thought. Conversely, the non-significant effects of vulnerability, self-efficacy, and response cost prompt a re-evaluation of their relevance in the context of flood-induced migration.

The moderating effects of past flood experience and average monthly income provide valuable theoretical insights into the factors influencing flood-induced migration intentions. The findings highlight the selective impact of past experiences and economic stability on migration decisions, prompting a re-evaluation of how these contextual factors are integrated into theoretical models. Specifically, the significant effect of average monthly income on the association between response efficacy and HMI illustrates the need for socioeconomic dimensions in understanding migration behaviors. These insights refine the existing models by emphasizing that migration decisions are not solely based on psychological factors but are also influenced by individuals’ economic and experiential contexts. The significant mediation pathways contribute to theoretical models by demonstrating how AEC influences HMI through intermediary constructs such as AER and response efficacy. These insights emphasize the cascading effects of environmental perceptions, suggesting that migration behavior is shaped by a combination of awareness, responsibility, and response efficacy rather than vulnerability alone.

Overall, the evaluation of the model’s explanatory power further contributes to the theoretical landscape by showcasing its strengths and limitations, indicating the necessity for ongoing model refinement to integrate emerging variables and enhance explanatory capabilities. By integrating perception-based factors, contextual moderators, and environmental awareness, the study advances theoretical understanding and sets a foundation for future research in environmental behavior and migration intentions.

Practical implications

From a practical perspective, the insights of this study are essential for disaster management and urban planning, particularly in flood-prone areas such as Klang Valley, Malaysia. Public awareness campaigns need to target specific environmental consequences and emphasize individual responsibility to mitigate flood impacts. Such campaigns should also incorporate strategies to enhance self-efficacy, such as skill-building workshops and resource provision, to ensure that individuals feel both responsible and capable of taking preventive measures. Additionally, educational programs should be tailored to communicate the personal and long-term risks associated with flood exposure, ultimately influencing migration decisions and fostering proactive, sustainable behaviors. The results emphasize the importance of enhancing public perception of flood severity and response efficacy through targeted awareness campaigns and disaster preparedness programs. Policymakers and urban planners in flood-prone regions should focus on improving the visibility and effectiveness of flood mitigation strategies to boost public confidence. By strengthening the perceived effectiveness of response measures, authorities can potentially increase migration intent among at-risk populations, thereby reducing vulnerability and enhancing long-term community resilience.

These results of the moderating effect underscore the importance of tailoring policies to the specific experiences and economic realities of flood-affected populations. For lower-income Households that might lack the resources to migrate independently, governments and local authorities could implement financial support mechanisms, such as relocation grants or subsidized housing programs, to alleviate the economic burden of migration. Furthermore, urban planners and policymakers should prioritize the development of affordable, safer housing in less flood-prone areas to incentivize relocation and reduce long-term vulnerability. For those with past flood experiences, risk communication strategies could be personalized to leverage their awareness and promote pre-emptive migration, thereby improving community resilience and adaptive capacity. The findings of the mediation analysis suggest that disaster management policies should incorporate multifaceted interventions focusing not only on immediate response but also on long-term environmental education and community engagement. Integrating sustainable urban development strategies can further strengthen individual and collective resilience, ensuring that communities are better prepared for flood-related migration scenarios.

Ultimately, the findings call for a collaborative and integrated disaster preparedness and migration framework involving local governments, environmental agencies, and NGOs. Such efforts should prioritize community-based risk reduction initiatives, empowering residents to engage actively in risk assessment and mitigation, thereby ensuring policies are locally grounded and responsive to the needs of vulnerable populations.

Policy recommendations

To develop flood resilience, policymakers must prioritize crafting community-driven flood awareness campaigns that foster increased environmental stewardship and readiness for disasters, particularly among vulnerable populations that are less resilient or have experienced a flood before. Urban interventions must concentrate on the development of sustainable infrastructure, such as upgrading drainage systems, constructing flood barriers, and improving the development of green spaces for runoff facilitation and reducing flood risks, especially in densely populated areas. In addition, governments must also investigate targeted financial support for low-income Households, such as flood insurance, migration incentives, and subsidized resettlement plans, to make them more economically resilient against flood risk. Public-private partnerships can be used to build cheap housing in safer zones and community resettlement schemes to reduce the risks among residents settled in high-risk flood zones. These pragmatic recommendations are meant to augment disaster risk reduction activities so that flood-prone communities are in a better position to cope with increasing flood hazards and move sustainably when a need arises.

Limitations and future research directions

Despite the valuable insights gained from this study, several limitations should be acknowledged, which also offer avenues for future research. First, the study is geographically restricted to Households in flood-prone regions of Klang Valley, Malaysia. While this focus provides context-specific findings, the generalizability of the results to other regions remains limited. Future research could expand the geographic scope of similar studies to explore whether the factors influencing migration intentions differ across diverse environmental and cultural contexts. Second, the study primarily focuses on individual-level factors, while other potential influences such as social networks, community support, and government policies were not examined. Including these additional variables could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how collective and institutional factors shape migration decisions in response to environmental threats. Future studies could adopt a multi-level analysis to account for community and policy-level influences on migration behavior. Third, while this study used the NAM and PMT to explain migration intentions, it did not explore the potential influence of psychological factors such as emotional responses (e.g., fear, anxiety) and cognitive biases, which could play a crucial role in decision-making under environmental stress. Future research could incorporate these psychological dimensions to better understand the complexities of migration behavior in the face of environmental hazards.

Fourth, the cross-sectional nature of this study limits its ability to capture the dynamic and evolving nature of HMI over time. Longitudinal studies would be valuable in understanding how these intentions change as individuals gain more experience with flooding. Fifth, the study relied on self-reported measures, which can be subject to response bias, particularly in assessing sensitive topics such as migration intentions. Future research could employ mixed-method approaches, combining surveys with qualitative interviews or focus groups, to obtain more nuanced insights into the motivations and challenges Households face when considering migration owing to environmental threats. Sixth, while this study focuses on past flood experience and average monthly income as moderating variables influencing migration intentions, it is important to acknowledge that other potentially relevant factors, such as gender and education level, were not included in the research framework. Future research could build on these findings by incorporating gender and education level into the research framework to explore their moderating roles in flood-induced migration. Seventh, we tested the moderating effect of monthly income on some specific paths of our framework. Future research could explore the effect on additional paths, offering a more comprehensive understanding of how economic resources and psychological factors together shape migration intentions in response to flood risks. Finally, the insignificant moderating effects suggest further research is needed to investigate why past flood experience intensifies the impact of perceived severity but not other factors, such as vulnerability or self-efficacy, on migration behavior.

Conclusions

This study provides considerable insights into the factors influencing HMI among Households residing in flood-prone regions of Klang Valley, Malaysia. By integrating the NAM and PMT, this research highlights the critical roles of environmental awareness, perceived severity, and response efficacy in shaping migration behavior in response to environmental threats. The findings reveal that AEC and AER are crucial in fostering a sense of responsibility toward the environment, which indirectly influences migration intentions. Moreover, the strong influence of perceived severity and response efficacy on migration intentions underscores the importance of perceived threat and the belief in effective responses as key determinants of protective behaviors. The study also identifies the moderating effects of past flood experience and average monthly income, revealing how personal experiences and economic conditions shape individuals’ responses to environmental risks. These moderating variables offer important insights for policymakers and practitioners aiming to improve disaster preparedness and migration policies in flood-prone areas. While the model demonstrates moderate explanatory power, the results suggest that additional factors, such as social or psychological influences, could enhance the understanding of migration behavior in the face of environmental threats.

Methods

This empirical study employed a quantitative approach, utilizing a self-administered questionnaire within a cross-sectional design to investigate the factors influencing HMI. Quantitative data were collected from participants at a single point in time between May and July 2024. The Human Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia approved this study (Ref. No. JEP-2023-463). This study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from respondents who participated in the survey.

Participants and procedures

The population of this study is the Households living in flood-prone areas of Klang Valley in Malaysia. This group is selected because they are directly exposed to flood risks, making them the most relevant population to study migration intentions in response to flooding. Focusing on Households is appropriate since migration decisions are often made at the household level, where factors like income, social networks, and family dynamics play an important role7,8. Klang Valley is the heart of Malaysia’s industry and commerce and is centered in the federal territories of Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya, its adjoining cities and towns in the state of Selangor. The reason for selecting this area is because it is highly vulnerable to flooding, highly urbanized, and socioeconomically heterogeneous. Klang Valley is highly exposed to floods because of urbanization and inadequate infrastructure22, which presents a good setting for the study of flood-induced migration. Economic disparities and unequal access to population resources complicate migration decisions, with poorer regions being more susceptible to flood impacts7. While other regions have experienced research on migration intent17,18, there is limited research on Klang Valley, particularly regarding psychological and socioeconomic determinants of migration. Additionally, this study can assist in reinforcing local disaster prevention and coping mechanisms for floods in Malaysia’s flood-prone cities, with noteworthy policy implications for Malaysia77. The National Disaster Management Agency of Malaysia published a list of flood-prone regions, and from that list, we selected 21 residential areas from Klang, Kuala Lumpur, Hulu Langat, Petaling, Sepang, Gombak, and Kuala Langat. To determine the required sample size, this study used G-Power (with input parameters such as effect size of 0.15, power 1-β err Prob of 0.80, number of predictors: 9), which gives us a minimum required sample size of 114. However, we collected data from 345 respondents to account for the large population and overcome the constraints of a small sample size. The sample is representative of Households within flood-prone areas, capturing the diversity of socioeconomic backgrounds, flood-risk perceptions, and past experiences with floods.

This study used the convenience sampling method, which selects respondents based on their accessibility, as no official list of Households living in selected flood-prone areas in Klang Valley is publicly available. This sampling approach ensures that the study reflects the experiences and perceptions of residents directly affected by flood risks, thus making the findings highly relevant for policy recommendations and disaster management strategies tailored to the region. Utilizing this approach, we identified flood-prone neighborhoods and then selected Households within these areas based on their availability and willingness to participate. The research team collaborated with local community leaders, neighborhood associations, and authorities to establish access and build trust within the communities. We collected data by providing a self-administered questionnaire to Households in the selected residential areas. We were able to collect data from Households that were in the house during the visit and agreed to participate in the survey. Our study includes a range of income levels and flood experiences, ensuring that it accounts for the socioeconomic diversity of the population, which is crucial for understanding how these factors influence migration decisions in other regions4,7.

Participants voluntarily provided informed consent after being fully briefed on the study’s objectives, data usage, and their right to withdraw without consequence. Confidentiality was maintained by anonymizing all personal information and securing data access to authorized researchers only for academic purposes. To ensure cultural appropriateness and conceptual clarity, a professional translation service was engaged to adapt the questionnaire for distribution in Malaysia. The process involved initial translation from English to Malay, followed by a back-translation into English to ensure accuracy. The translated version was then reviewed by local experts for clarity and cultural relevance. To ensure quality, 10 social workers and community leaders residing in flood-prone areas reviewed the questionnaire, leading to revisions based on their feedback. Finally, a pilot test with 40 respondents further validated the instrument’s reliability and clarity before full-scale data collection. The pilot testing took place within one of the flooded areas of the Klang Valley, like in the regions to be used in the main survey. In our pilot testing, we intended to pilot-test the comprehensibility of the questionnaire, as well as possible response categories, and the overall continuity of the survey to ensure proper interpretation of questions. We also consulted on the duration required to complete the survey and adapted accordingly so that the survey was not overly time-consuming or complicated for the respondent.

Research materials

The hypotheses of this study were tested using a survey. All questions were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). AEC involves an individual’s understanding of the potential negative impacts that may occur due to a lack of action. The items used to measure AEC were adopted from earlier studies78,79. AER involves accepting an individual’s involvement in contributing to these consequences. AER was measured using items from earlier studies79,80. Perceived severity refers to an individual’s assessment of the seriousness of a threat or condition. Items for perceived severity were drawn from earlier studies81,82. Perceived vulnerability is an individual’s subjective evaluation of their likelihood of experiencing an environmental threat or condition. Perceived vulnerability was measured using four items adapted from earlier study82. Self-efficacy refers to the belief in one’s own capacity to tackle certain situations and was measured based on earlier studies81,83. Response efficacy refers to individuals’ perception of the effectiveness of their actions in mitigating environmental threats. The items for response efficacy were adapted from earlier studies81,83. Response cost refers to the perceived expenses or barriers associated with adopting a protective behavior or coping response. The items used to measure response cost were adopted from earlier studies81,83. For past (flood) experience, the items were taken from earlier studies84,85. HMI refers to the willingness or intention of individuals or Households to migrate from a flood-prone area in response to the perceived risks associated with flooding. The items for flood-induced HMI were adapted from earlier study86.

To assess potential common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The test revealed that a single factor accounted for 24.721% of total variance, well below the recommended threshold of 50% as outlined87. This indicates that common method bias is unlikely to be an important issue in this study. Additionally, we evaluated common method bias by performing a full collinearity assessment of all constructs88. As shown in Table 3, the variance inflation factor values for all variables ranged from 1.055 to 1.760, below the critical threshold89 of 3.3, which suggests the absence of common method bias.

To identify the most suitable data analysis approach for this study, an evaluation of multivariate normality was necessary. We used the Web Power online tool to assess multivariate normality90. The results of the multivariate normality test indicated that the p-values for Mardia’s multivariate skewness and kurtosis were both below 0.05, signifying non-normality. When satisfying the strict assumptions of traditional multivariate methods, such as the requirement for normally distributed data, is difficult or unrealistic, Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) becomes the preferred analytical technique. As a result, we selected PLS-SEM as the most appropriate method for assessing both the measurement and structural models in this research.

In this study, we performed data analysis using the PLS-SEM technique through SmartPLS 3.1 software. PLS-SEM, being a multivariate analysis tool, is particularly well suited for handling small datasets and non-normal data. PLS-SEM is a causal predictive method that does not necessitate the use of goodness-of-fit estimates for complex models involving composites88.

The data analysis procedure in this research comprised two main steps. First, we scrutinized the validity and reliability of the constructs in accordance with the recommended procedure75. Second, we tested assumptions and evaluated the structural model91. To derive model estimates reflecting the influence of exogenous constructs on endogenous ones, we utilized the results of the coefficient of determination (R²) and effect size (f²)75.

Availability of data and materials