Abstract

Aging is associated with a progressive decline in tissue function and regenerative capacity, partly due to genomic instability, one of the hallmarks of aging1,2. Genomic instability encompasses DNA damage and the accumulation of somatic mutations in post-zygotic cells, yet the specific impact of these mutations on age-related tissue dysfunction remains poorly understood. To address this, we developed a mouse model in which genomic instability was induced specifically in muscle progenitor cells3 through targeted deletion of the Msh2 (ref. 4) and Blm5 genes. This allowed us to assess how elevated DNA damage and somatic mutations, from single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) to structural variants, affect muscle regeneration following injury. These mice exhibited impaired muscle regeneration, characterized by smaller muscle fibers, reduced muscle mass gain and decreased grip strength. Importantly, similar muscle deficits were observed in a second mouse model where somatic mutations were elevated with less substantial DNA damage. These findings provide evidence that the accumulation of somatic mutations can potentially compromise the function of somatic cells, contributing to the aging phenotype in skeletal muscle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Old age is a major risk factor for diseases such as cancer, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and neurodegeneration. Aging is linked to reduced tissue function and regeneration1, with genomic instability, marked by accumulating somatic mutation, being a key hallmark1,2. These mutations, arising from replication errors or DNA repair defects, are not inherited but lead to tissue mosaicism2. Although genome instability and DNA damage have been characterized in aging6,7,8,9, the functional role of somatic mutation accumulation in age-related tissue decline and age-related diseases beyond cancer remains less explored10,11.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) studies have shown that somatic mutations accumulate with age in human skeletal muscle progenitor cells12 and other tissues13,14,15,16, with similar observations in most tumor types17,18. Differentiated cells often carry even higher mutation loads13,19, highlighting the underestimated extent of age-related somatic mutagenesis. Although we previously showed that high mutation burden impairs satellite cell (SC) function in vitro12, in vivo evidence for the role of somatic mutations in muscle tissue function remains limited.

Aged human cells, including SCs, show structural genetic variations such as chromosomal aberrations, SNVs and short insertions/deletions (InDels)12,13,15. To model this, we generated muscle somatic mutator (MSM) mice by deleting the DNA repair genes Msh2 and Blm specifically in SCs. Msh2 deficiency, linked to Lynch syndrome, leads to increased SNVs, InDels, and chromatin breaks4,20,21,22,23, though patients do not show muscle impairment24. Locomotor defects have only been shown in Msh2-deficient mice in correlation with altered neuron firing25. Blm mutations, which cause Bloom syndrome, increase chromosomal instability and structural genetic variations without affecting muscle development5,21,26,27. To study the effects of increased somatic mutations in SCs, we deleted Msh2 and Blm and then induced SC-driven muscle regeneration following injury. Expanded recombined SCs led to impaired muscle regeneration and reduced strength. To try to separate the effect of somatic mutations from those of DNA damage, we created a second model with Msh2 deletion alone, which induced SNVs and InDels with less substantial DNA damage. This model replicated the MSM phenotype, supporting a somatic mutation driven effect on muscle regeneration. In summary, our strategy offers a framework to study the functional impact of somatic mutations in diverse cell types and their potential role in tissue dysfunction.

Generation of the MSM model

We created the MSM mouse model by combining a Pax7-driven tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase3 with floxed Msh24 and Blm5 alleles. Recombination was induced postnatally (weeks 7–9) specifically in SCs, which drive muscle regeneration5,28,29. To enhance mutagenesis and assess SC function in response to increased DNA damage and somatic mutations, we subjected each mice to three consecutive BaCl2 induced injury-regeneration cycles in the right tibialis anterior (TA) muscle (Fig. 1a). The contralateral left TA functioned as uninjured muscle control. Mice carrying only the Pax7-driven Cre recombinase and not deficient for Msh2 and Blm, were also subjected to injury-regeneration cycles in the right TA (referred to as control mice). TAs were analyzed after the third cycle.

a, Schematic representation of the experimental setup. Created in BioRender. Eriksson. M (2025). https://BioRender.com/qb882vw. b, Hematoxylin-eosin TA staining after three regeneration cycles. The right TA is regenerated muscle, and the uninjured left TA is the control (Ctrl). c, Quantification of fibers with centralized nuclei in non-injured and regenerated TA (control n = 9, MSM n = 9); Ctrl-non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 1 ×10−13; MSM-non-inj. vs MSM-Regen. P = 1 ×10−13. d, Msh2 and Blm allele recombination quantification in non-injured and regenerated TA of MSM mice (non-injured n = 3, regenerated n = 3); Msh2 recombination: non-inj. vs Regen. P = 0.0047; Blm recombination: non-inj. vs Regen P = 9.89 ×10−5. e, Msh2 and Blm immunofluorescence of non-injured and regenerated TA. f, Quantification of Msh2-positive nuclei in non-injured and regenerated TA (control n = 4, MSM n = 3) and Blm-positive nuclei in non-injured and regenerated TA (Control n = 3, MSM n = 3); Msh2 expression: Ctrl vs MSM P = 8.07×10−10; Blm expression: Ctrl vs MSM P = 9.13 × 10−10. g, Picro Sirius Red staining of non-injured and regenerated TA. h, Quantification of Picro Sirius Red-stained muscle in non-injured and regenerated TA (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9); Ctrl-Non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 0.1269; MSM-non-inj. vs MSM-Regen. P = 0.0120. i, Pdgfrα immunofluorescence of non-injured and regenerated TA. j, Quantification of Pdgfrα-positive cells in non-injured and regenerated TA of control mice (Non-injured TA n = 4, regenerated TA n = 4) and MSM mice (Non-injured TA n = 3, regenerated TA n = 4) Ctrl-Non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 0.8625; MSM-non-inj. vs MSM-Regen. P = 0.5965. k, Pax7 immunofluorescence of non-injured and regenerated TA. l, Quantification of Pax7-positive nuclei in non-injured and regenerated TA (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9); Ctrl-Non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 0.8868; MSM-non-inj. vs MSM-Regen. P = 0.7465. m, Ki67 immunofluorescence of non-injured and regenerated TA. n, Quantification of Ki67 positive nuclei (Control-non-inj n = 6, Control-regen n = 9, MSM-non-inj n = 9, MSM-regen n = 9); Ctrl-Non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 0.3449; MSM-non-inj. vs MSM-Regen. P = 0.3900. Panels b and g scale bars indicate 100 μm; panels e, i, k and m scale bars indicate 20 μm. Statistical tests used in c, f, h, j, l and n were one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey multiple comparison test (d, unpaired t-test, two tailed). * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Graphs in c, d, f, h, j, l and n present data as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). Arrowheads in i, k and m indicate positive nuclei/cells.

Successful Msh2 and Blm recombination in MSM skeletal muscle

To assess regeneration, we quantified the number of fibers with centralized nuclei in the right TA, a hallmark of regenerated muscle (Fig. 1b). Control and MSM mice showed, on average, 80.8% and 76.9% of fibers with centralized nuclei, respectively, whereas the uninjured left TA contained virtually none, confirming right TA regeneration after injury (Fig. 1c). To evaluate Msh2 and Blm deletion, we measured allele recombination in non-injured and regenerated muscle. Although the average percentage of recombined alleles was 1.72% for Msh2 and 1.92% for Blm in non-injured TA, it increased to 13.33% for Msh2 and 16.43% for Blm in regenerated MSM muscle (Fig. 1d), indicating successful SC targeting and expansion. Immunofluorescence confirmed this, with Msh2 and Blm signals dropping from 79.6% and 81.5% stained centralized nuclei in control mice regenerated muscle, to 11.4% and 11.6% stained centralized nuclei in MSM mice regenerated muscle (Fig. 1e,f).

Reduced TA regeneration efficiency in MSM mice after injury

We examined muscle regeneration in control and MSM mice. In controls, connective tissue, typically elevated during regeneration3, returned to baseline in regenerated TA. By contrast, MSM mice showed persistently elevated collagen in regenerated TA compared to non-injured TA, indicating impaired repair (Fig. 1g,h). To determine if this was due to sustained fibroadipogenic progenitor (FAP)30,31 expansion, we performed Pdgfrα staining30,31. FAP numbers were similar in non-injured and regenerated TA across both groups (Fig. 1i,j), suggesting fibrosis in MSM mice is not due to chronic FAP accumulation. After the final regeneration cycle, Pax7 staining showed similar SC frequencies in MSM and control mice (0.8 to 1.3%, on average), consistent with basal quiescent levels (~1%)32 in both non-injured and regenerated TA (Fig. 1k,l). Ki67 staining also revealed no difference in proliferating cells between groups (Fig. 1m,n), suggesting no changes in basal SCs proliferative status and that regeneration had ceased.

Increased mutations and genomic instability in MSM muscle

To confirm increased somatic mutations in the MSM model, we performed deep WGS of regenerated muscle. MSM mice showed a 1.61-fold increase in the number of SNVs compared to control mice (Fig. 2a). Structural variant analysis also revealed more large deletions in MSM compared to control mice muscle, consistent with Blm deletion27 (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Data 1). 53BP1 immunofluorescence showed elevated double-strand breaks (DSBs) in MSM-regenerated muscle (Fig. 2b,c), supporting increased DNA damage33. Additionally, regenerated MSM muscles had more for phosphorylated RPA-positive (S4/S8) cells, a marker of single-stranded DNA, present during DSB repair34 (Fig. 2e,f). Both markers were enriched in centralized nuclei of MSM muscle fibers (Fig. 2d,g).

a, Barplot of the number of somatic single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) in by WGS of representative histological samples of regenerated TA from control, MSM and Msh2-deficient mice. The measurement was performed on downsampled data (n = 3). b, 53BP1 immunofluorescence of regenerated TA. Arrows indicate 53BP1-positive nuclei that are enlarged in the below pictures. Transmitted detection was used to visualize myogenic fibers. c, Quantification of 53BP1-positive cells in regenerated TA (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.0039, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.6368. d, Quantification of 53BP1-positive centralized myonuclei in regenerated TA (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.0001, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.1845. e, Phospho-RPA32 (phospho S4 + S8) immunofluorescence of regenerated TA. Arrowheads indicate one phospho-RPA32 (phospho S4 + S8)-positive and one negative nuclei that are enlarged in the below pictures. Transmitted detection was used to visualize myogenic fibers. f, Quantification of phospho-RPA32 (phospho S4 + S8)-positive nuclei in regenerated TA (Control n = 4, MSM n = 4, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.0131, MSM vs Msh2-def. P = 0.0061. g, Quantification of phospho-RPA32 (phospho S4 + S8)-positive centralized myonuclei in regenerated TA (Control n = 4, MSM n = 4, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.0187, MSM vs Msh2-def. P = 0.0087. Panel b scale bar indicates 100 μm; panel e scale bar indicates 20 μm. Statistical tests used in c, d, f and g: one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Graph a presents a single representative value for each group. Graphs in c, d, f and g present data as mean ± s.d.

Accumulation of somatic mutations in Msh2-deficient muscle

To try to separate persistent DNA damage effects from those of somatic mutations, we generated a second mouse model with Pax7-specific deletion of Msh2 (hereafter “Msh2-deficient”), which leads to SNV and InDel accumulation but not structural variants3,4. After three injury-regeneration cycles, Msh2-deficient mice muscles resembled MSM histologically, with 60.7% of fibers containing central nuclei (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). 21.7% of Msh2 alleles were recombined (Extended Data Fig. 1c), and only 10% of centralized nuclei were Msh2-positive, compared to 79.6% in control mice regenerated muscle (Extended Data Fig. 1d,e).

Msh2-deficient mice showed a 2.77-fold increase in SNVs compared to controls (Fig. 2a), with no increase in SVs (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Data 1). Consistent with this, there was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of 53BP1-positive cells, suggesting that the elevated DSBs in MSM muscle might be mostly linked to Blm deletion (Fig. 2b–d). Phosphorylated RPA levels also remained unchanged (Fig. 2e–g), indicating minimal activation of mismatch repair (MMR), nucleotide excision repair or base excision repair34.

Msh2-deficient mice showed no changes in connective tissue or FAP frequency after the last regeneration cycle, similar to controls and unlike MSM mice (Extended Data Fig. 1f–i). The number of Pax7-positive cells returned to baseline, with no active proliferation detected (Extended Data Fig. 1j–m).

Somatic SNV-associated genes related to muscle regeneration

WGS analysis detected 828, 692 and 2,127 somatic variants in regenerated TA from control, Msh2-deficient, and MSM mice, respectively (Supplementary Data 2), with similar genomic distributions across groups (Fig. 3a). We found 35 exonic SNVs affecting the protein sequence (Supplementary Table 1). We used MutPred235 on the 20 missense SNVs, and 5 were predicted as likely deleterious (Supplementary Table 1). Thirteen of the 35 exonic mutations occurred in genes related to muscle biology, including Rpsa, Gmpr, Npm1, Pnkd and Nhp2l1 (refs. 36,37,38,39,40). The alternative allele frequencies of these SNVs ranged from 8.5% to 19%, indicating their presence in a substantial fraction of cells (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 3b). Pcm1 staining41 showed that about 25.4% of nuclei (range: 13–32%) belonged to muscle fibers (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b), suggesting these mutations may be present in newly formed fibers, although their presence in other cell types proliferating during regeneration cannot be excluded36,42.

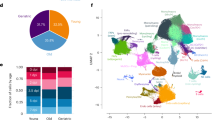

a, Graphic representation of the genomic distribution of somatic variants identified from non-downsampled control, Msh2-deficient and MSM mice. b, Distribution of alternate allele frequency of 13 somatic variants on exons of protein coding gene. The central line of the boxplot represents the mean value of the data. The edges of the box correspond to the 25th (Q1) and 75th percentile (Q3). The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles, and points beyond whiskers are outliers. c, Cell types derived by reanalyzing single-cell transcriptome dataset of regenerating muscle of an injured mice from the study published by De Micheli et al.42 d, Distribution of cells from non-injured (Day 0) and days post-injury (Day 2, Day 5 and Day 7) in individual clusters obtained from single-cell transcriptome analysis. e, Expression of protein coding genes associated with somatic variants visualized using UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection). f, Expression of protein coding genes associated with somatic variants from control, Msh2-deficient and MSM myogenic cells. The circle size represents percentage of cells in which corresponding gene is expressed and the color gradient represents average expression level in individual clusters or corresponding cell types. NK, natural killer.

To explore links between somatic variants and an impaired muscle phenotype, we analyzed the function of the mutated genes using a published scRNA-seq dataset of muscle regeneration following injury42. Cell clusters from injured muscle (up to Day 7 post-injury) were identified (Fig. 3c,d), and gene expression compared between non-injured (Day 0) and injured time points (Days 2, 5 and 7). Notably, Npm1 and Rpsa, both frequently mutated in our data (Supplementary Table 1), were highly expressed in SCs at Days 2, 5 and/or 7 (Fig. 3e,f and Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). Previous studies showed Npm1 degradation is required for early myogenesis in murine myoblasts37. Rpsa, which interacts with laminins, was previously identified as the top differentially expressed gene in SCs and as a key regulator of SC activation during aging36. Gmpr, mutated specifically in MSM mice, showed higher expression in mature muscle cells36,40, whereas Pnkd, also mutated in MSM mice, was enriched in SCs (Fig. 3f). Notably, missense Pnkd mutations are linked to movement disorders with prolonged muscle contractions38,43,44,45. We tried to match genes carrying somatic mutations with our previous work on somatic mutations in human aged SCs12, but no overlaps were found between the studies. A potential explanation for this was the limited amounts of cells analyzed in the previous study. In summary, our data reveal several SNVs that could impair muscle regeneration and function, though further studies are needed to confirm this.

Reduced regeneration and strength in MSM and Msh2-def mice

Previous work showed that increased mutation burden impairs SC proliferation and differentiation in vitro12. To assess functional effects in vivo, we analyzed muscle tissue from the cellular to the organ level. Given the role of senescence in tissue dysfunction1,26, we stained for p16 and found increased p16-positive cells in MSM mice, especially in centralized nuclei, whereas levels were unchanged in Msh2-deficient muscles (Fig. 4a–c). This suggests a DSB-linked senescence response in MSM mice not present in Msh2-deficient mice. However, Lamin B1 staining did not indicate a statistically significant increase in senescence induction in MSM or Msh2-deficient regenerated muscles (Extended Data Fig. 4a b). Regenerated muscle fibers remained smaller in MSM mice, whereas control mice achieved a normal size (Fig. 4d,e), suggesting defective muscle regeneration in MSM (Fig. 4d,e). A similar myofiber size reduction was observed in Msh2-deficient mice (Fig. 4d,e). Importantly, no size differences were seen in contralateral, non-injured muscles, indicating that the DNA repair deficiencies in SCs affected regeneration following injury regeneration and SC propagation (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b).

a, p16 immunohistochemical staining of regenerated TA. Arrowheads indicate examples of p16-positive nuclei. b, Quantification of p16-positive cells in regenerated TA (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.1616, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.6654. c, Quantification of p16-positive centralized nuclei in regenerated TA (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.0122, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.9907. d, Graphs displaying the size distribution of regenerated fibers across the different groups. Curves illustrate the Gaussian distribution of fiber sizes. Arrows show the shift towards smaller fibers in MSM and Msh2-deficient mice (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3). e, Graph showing the average cross-sectional area of regenerated fibers (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.04606, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.0277. f, Graph showing the difference in TA weight gain due to hypertrophy (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.0244, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.0959. g, Graph showing the fold change of normalized grip strength (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.0024, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.0250. Panel a scale bar indicates 100 μm; panel d scale bar indicates 20 μm. Statistical tests used in b, c, e, f and g: one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001 Graphs in b, c, e, f, and g present data as mean ± s.d. Graph d presents data only as mean for clearer presentation.

Our strategy to study increased somatic mutation accumulation focused on SCs of the TA muscle. However, we asked whether the regeneration defect extended to whole-muscle function. Hypertrophy is normally seen after injury regeneration3 and although there was muscle weight gain in the MSM mice it was lower than in the controls (Fig. 4f). Finally, lower-than-control grip strength in MSM mice throughout the experiment showed that muscle with increased somatic mutations had reduced grip strength (Fig. 4g). Grip strength was mostly reduced after the last cycle of regeneration compared to the previous two cycles, when the number of induced somatic mutations is expected to peak (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Msh2-deficient mice showed similarly reduced muscle mass and strength (Fig. 4f,g and Extended Data Fig. 5c), indicating functional impairment at the organ level.

To confirm that the observed phenotype depended on SC propagation to muscle fibers, we analyzed control, MSM and Msh2-deficient mice that did not undergo injury. Recombination rates were low (1.92% and 1.72%, respectively; Fig. 1d), indicating minimal regeneration. Thus, only SCs and possibly a few regenerated muscle fibers, at most, will harbor more somatic mutations. The right TA from these mice did not show statistically significant changes in the number of centralized nuclei (Extended Data Fig. 5d,e), collagen deposition (Extended Data Fig. 5f,g) and total number of SCs (Extended Data Fig. 5h,i) suggesting that growth or activity alone did not impair regeneration in the absence of injury. Grip strength in uninjured MSM and Msh2-deficient mice was similar to uninjured controls, indicating that widespread propagation of mutation-bearing SCs during regeneration is required to impair muscle regeneration (Extended Data Fig. 5j).

Discussion

This study models excessive somatic mutation accumulation during postnatal skeletal muscle regeneration. Using two in vivo mouse models, we show that elevated genomic instability and somatic mutation burden impair muscle regeneration and reduce muscle strength.

Both MSM and Msh2-deficient mice exhibited similar phenotypes, including reduced muscle fiber cross-sectional area, lower hypertrophy and lower grip strength. However, MSM mice showed additional regeneration defects, notably increased collagen deposition in regenerated muscle. Although chronic FAP expansion can contribute to fibrosis30,31, Pdgfrα staining revealed no change in FAP numbers between uninjured and regenerated TA. Further studies are needed to determine the cause of the higher collagen deposition in MSM mice, such as altered FAP differentiation or disrupted signaling between myofibers, extracellular matrix, and FAPs.

Both models accumulated excessive SNVs, but only MSM mice accumulated large SVs. Interestingly, Msh2-deficient mice had a higher SNV load (2.77x versus 1.61x in MSM). One possible explanation for this could be that SVs in MSM mice lead to the loss of cells with excessive mutations. The lower SNV count also correlates with lower Msh2 recombination efficiency in MSM mice (13.33%) compared to Msh2-deficient mice (21.65%).

MSM mice showed higher levels of DSB and single-stranded DNA, consistent with the Blm deletion inducing the occurrence of large SVs. Msh2-deficient mice showed impaired muscle regeneration and reduced muscle strength comparable to the MSM model, but with less pronounced DNA damage. Low levels of DNA damage were expected in the Msh2-deficient mice, as the function of the Msh2 protein is to recognize mismatched base-pairs during DNA replication46. Without Msh2, mismatches remain undetected and eventually become mutations. Although Msh2 also participates in additional repair pathways (that is, nucleotide excision repair and base excision repair)47, which could have been a source of additional DNA damage, staining of phosphorylated RPA (S4/S8) suggested there was no substantial DNA damage in Msh2-deficient mice. Msh2-deficient mice showed no increase in p16 or Lamin B1-related senescence in regenerated muscle, indicating senescence wasn’t a main factor in reduced regeneration and strength. Overall, these findings support that somatic SNVs accumulation can impact tissue dysfunction.

By integrating somatic mutation data from our mice and reanalyzing publicly available single-cell data on muscle regeneration42, we mapped 13 exonic SNVs to genes related to muscle biology. Although their allele frequencies were consistent with the myonuclei proportion in muscle tissue (13–32%), these somatic mutations could have potentially occurred in other cell types in the muscle. Particularly during muscle regeneration, FAPs and immune cells expand substantially36,42, and extensive DNA replication could generate more mutations independently of the Blm and Msh2 knock-out. Mutations in muscle fibers likely arose from clonal SC expansion during regeneration. Mutations neutral to SC proliferation may impair subsequent SC differentiation or reduce muscle strength, whereas others could give SCs a growth advantage, disrupting the balance needed for effective regeneration. The 13 exonic SNVs affect muscle-related genes expressed during regeneration, suggesting a role in impaired repair. However, detecting the full spectrum of somatic mutations in a tissue is still challenging, particularly with bulk analysis, which detects clonally expanded mutations2,48,49. Hence, additional undetected deleterious mutations likely contributed to the phenotype.

Our study provides experimental evidence that somatic mutation accumulation in post-zygotic cells can contribute to muscle aging phenotypes. It highlights the role of somatic mutations in age-related diseases and a consequent impact of donor age on progenitor cell fitness for transplantation. This model could be applied to other cell types, to explore somatic mutation effects on tissue function and maintenance.

Methods

Ethical approval

Animal studies were approved by Linköping’s regional animal research ethical review board (Dnr. ID 215, Dnr. ID 04483-2023). All procedures were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines and regulations.

Experimental mice

All experimental mice from this study belonged to the C57BL/6 J strain. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free animal facility at the Karolinska Institutet (Campus Flemingsberg, Sweden) and maintained in a 12 h light/dark cycle, at 20–22 °C temperature and 50–65% air humidity. Pax7CreERT2 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and were published before3. Msh2LoxP mice were a kind gift from W. Edelmann4. Blmtm4Ches mice were a kind gift from A. J. R. Bishop5. All three transgenic lines were crossed to obtain the MSM mice that genotyped heterozygous for Pax7CreERT2, homozygous for Msh2LoxP and homozygous for Blmtm4Ches (n = 9; 5 females, 4 males). The Msh2-deficient group of animals was heterozygous for Pax7CreERT2 and homozygous for Msh2LoxP (n = 3; 2 females, 1 male). The control mice group was heterozygous for Pax7CreERT2 and didn’t carry any Msh2LoxP or Blmtm4Ches alleles (n = 9; 5 females, 4 males).

Muscle injury and Cre activation were performed as described by Murphy et al.3. Briefly, muscle injury was induced by injecting 25 µl of 1.2 % BaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich) in saline into the right TA muscle. The left TA served as the non-injured control. Three consecutive 28-day muscle injury and regeneration cycles were performed by inducing muscle injury on days 0, 28 and 56 (Fig. 1a). During each of the cycle each mouse received an intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 mg of tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) per gram of body weight dissolved in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich) on the 4th and 3rd day before the injury, on the same day as the injury, and on the two following days. The goal of the repeated tamoxifen injections was to maximize the number of SCs that were recombined. A weekly tamoxifen injection was also given for the following three weeks before the start of the next muscle injury and regeneration cycle. These number of tamoxifen injections were previously shown to induce recombination in over 95% of SCs3, a number that would maximize the number of recombined myofibers upon regeneration. The grip strength test was performed before the first and for 6 weeks after the end of the last regeneration cycle. We used an in-house developed grip strength meter based on a conventional 25 N force meter (Sauter) to measure the grip strength of hind two legs. A group of non-injured control (n = 3; 3 males), MSM (n = 6, 3 females, 3 males) and Msh2-deficient (n = 3; 3 males) mice underwent the same experimental procedure and were used as additional controls to assess skeletal muscle strength when somatic mutations were limited to SCs in a context of aging. All mice were aged 7-9 weeks at the start of the experiment. The average of the last 4 grip strength measurements was compared to the first measurement before the first injury. Body weight was used for normalization. The experiment lasted for 15 weeks, and mice were euthanized on day 100 by administering an overdose of isoflurane (Baxter). Right and left TA were carefully removed, weighed with an analytical balance, and halved; one part was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and the other fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde (Merck).

Genotyping was performed using the following primers:

-

Pax7CreERT2 mice: forward primer 5′-GCTGCTGTTGATTACCTGGC-3′, reverse primer 1 5′-CTGAGACAGGACCG-3′ and reverse primer 2 5′-CAAAAGACGGCAATATGGTG-3′.

-

Msh2LoxP mice: Msh2 forward 5′-TACTGATGCGGGTTGAAGG-3′, Msh2 reverse: 5′-AACCAGAGCCTCAACTAGC-3′.

-

Blmtm4Ches mice: Blm forward 5′-AACCTGCTTCAGCTAGGAGCTTCC-3′, Blm reverse 5′-TGGGACCGAATTGCTTCAACAACG-3′.

Tissue processing and histology

Fixed TA samples were embedded in paraffin and cut into 4 μm sections. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed according to established procedures and used for fiber cross-sectional area analysis. At least 100 fibers per sample were quantified, using “Polygon selection” followed by “Analyze” and “Measure” commands in ImageJ. For regenerated samples, only areas with fibers presenting centralized nuclei were included in the measurements. Detection of collagen was performed by Picro Sirius Red staining. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and incubated with 0.1% Picro Sirius Red stain for 20 min and then counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. The percentage of collagen in the tissue was calculated by selecting the red-stained portion of each image using Adobe Photoshop, deleting all non-red pixels, converting the resulting image to Bitmap format and quantifying the selected pixels with ImageJ “Analyze particles” function.

Immunostaining

Muscle sections (4 μm) were deparaffinized and subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval. Blocking was performed with normal goat/donkey serum and/or mouse-to-mouse blocking reagent (Scytek). Primary antibodies were applied to specimens, followed by overnight incubation. Primary antibodies used were: rabbit anti-Msh2 (1:500, ab70270, Abcam), to validate the Msh2 deletion, rabbit anti-Blm (1:100, ab2179, Abcam), to validate the Blm deletion, mouse anti-Pax 7 (1:100, DSHB) to identify SCs, mouse anti-Pcm1 (1:100, sc-398365, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to detect nuclei specifically from myofibers, rat anti-PDGFRα (1:150, 14-1401-82, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to detect fibroadipogenic progenitors, rabbit anti-53BP1 (1:1,500, ab36823, Abcam) to detect DNA damage, rabbit anti RPA32/RPA2 (phospho S4 + S8, 1:100, ab87277, Abcam) to detect single-stranded DNA, rabbit anti-Ki67 (1:150, ab15580, Abcam), to detect proliferative cells, and rabbit anti-p16 (1:400, M-156, sc1207, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit anti-LaminB1 (1:500, ab16048, Abcam), both to mark senescent cells. Sections were then incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 568, donkey anti-rabbit (1:500, #A10042); Alexa Fluor 647, goat anti-mouse (1:500, #A21236); Alexa Fluor 647, goat anti-rabbit (1:500, #A21245); Alexa Fluor 488, goat anti-rat (1:500, #A11006). For immunohistochemistry, vectastain ABC kit (ABC Elite, Vector Laboratories) and DAB solution (Dako) were used for enzymatic detection. The secondary antibody was Biotin-goat anti rabbit (1:2,000, 656140, Invitrogen) Tissue sections were counterstained with either Mayer’s hematoxylin (Histolab) or DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For each staining, the percentage of positive nuclei per sample was obtained by manually scoring 200–600 DAPI-positive nuclei from three different images. Centralized and non-centralized nuclei were manually evaluated. Quantifications were done in a double-blind fashion.

Image acquisition

Histological and immunohistochemistry imaging was achieved using the Nikon Eclipse E1000 microscope (Nikon Corporation) coupled to the Nikon digital sight DS-Fi2 camera. Immunofluorescence imaging was performed on a Nikon A1R and A1+ single point scanning confocal, using the NIS Elements software (Nikon Corporation), and imaging with a ×20 air objective. For each sample, we acquired large images of 2×2 tiles, which were stitched in one final image. We also captured Z-stacks over 8 planes, with 1.5 um separation between adjacent sections. Maximum intensity projection (MaxiIP) images were generated from the Z-stacks and analyzed. To detect centralized nuclei we used Transmitted Detection pictures to identify the fiber structure. Analysis of confocal images were performed using NIS elements Viewer, NIS Elements AR v5.42.02 and QuPath 0.5.1 (ref. 50). Immunofluorescence images were blinded.

DNA isolation for recombination analysis and sequencing

We used low tissue input for the DNA extraction. Twelve 50 µm sections of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded regenerated TA samples were cut and DNA was extracted using Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions for DNA purification from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue. For use as reference for identification of somatic mutations, DNA was also extracted from frozen spleen samples of the respective mice using the same kit according to manufacturer’s instructions for DNA purification from tissue.

Recombination analysis

Analysis of recombined alleles was performed using the QX200 droplet digital PCR system (Bio-Rad). PCR reactions were set up using 2x QX200 EvaGreen Mix (Bio-Rad), forward and reverse primers and template DNA and ran according to manufacturer’s instructions. 10 ng of sample DNA was used per well and run in two replicate wells. Primers were designed to be specific for the Msh2 and Blm recombined alleles (Msh2 forward: 5′-TACTGATGCGGGTTGAAGG-3′, reverse: 5′-GGCAAACTCCTCAAATCACG-3′, previously published11; Blm forward: 5′-TCAATGGCAAAAATAGGGAGGGTTG-3′, reverse: 5′-TGGGACCGAATTGCTTCAACAACG-3′). Recombined allele counts were normalized against Egfr allele (Egfr forward: 5′-CCACAGCTGAAAATGCAGAG-3′, reverse: 5′-CCTCACCATGAGGCAAACTT-3′). The data from ddPCR were analyzed using QuantaSoft v.1.6.

Sequencing

WGS was performed on DNA extracted from skeletal muscle and spleen from injured control, MSM and Msh2-deficient mice (n = 3). Because somatic mutations remain challenging to detect2,48, we used bulk-tissue WGS to identify clonally expanded mutations, rather than measuring the somatic mutation burden of individual cells. Sequencing was performed by the National Genomics Infrastructure in Stockholm, Sweden, and the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform in Uppsala, Sweden. From the spleen, sequencing libraries were prepared from 1 μg DNA using the TruSeq PCR-free DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina Inc.) targeting an insert size of 350 bp. The library preparation was performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. From the skeletal muscle, libraries were prepared from 50 ng of DNA using the SMARTer ThruPLEX DNA-seq Prep Kit (Takara Clontech) according to the manufacturers’ protocol. The libraries were sequenced on HiSeqX, paired-end 150 bp read length, v2.5 sequencing chemistry.

Somatic mutation detection from downsampled data

Fastq files were aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm10, GRCm38) using BWA51 0.7.17-r1188 with default parameters. Alignments were sorted and indexed using SAMtools 0.1.19 (ref. 52). The average coverage was 42X. Analysis of the sequencing data revealed differences in coverage between the samples. Downsampling was necessary to be able to compare the proportion of detectable somatic mutations between the different samples due to a difference in coverage between the samples. BAM files were therefore randomly downsampled to the lowest coverage using SAMtools (46X for muscle, 29X for the spleen). For every sample, duplicated reads were marked using Picard (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/, v2.10.3-SNAPSHOT). Local realignment around InDels was performed and the two samples from the same individual mouse were aligned together to improve variant calling using the Genome Analyzer Toolkit v3.4.0 (GATK)53. Variants were called using the somatic mode of three somatic callers: GATK-MuTect2 (v.4.1.1.0)54, Strelka2 (v.2.9.3)55 and Varscan2 (v.2.3.7)56 with skeletal muscle as tumor and spleen as normal. Annotations were done using snpEff_4.2 (ref. 57) and VEP Ensembl58. Somatic variants detected by all three somatic variant callers were subjected to post-process filtering. Variants that had minimum 15X read depth in spleen and skeletal muscle, minimum five alternative allele depth in the skeletal muscle, and a statistically significant difference between the spleen read count and the skeletal muscle read count (P < 0.05, Fisher exact test) were considered somatic variants. All recurrent variants were excluded from the analysis. For SV detection, DELLY2 was used with default parameters59. We also excluded SNVs from lab strains using dbSNP142 from the mouse genome project.

Somatic mutation detection from non-downsampled data

To identify somatic variants, the above analysis and filtering were also performed on non-downsampled data, so the amount of information for each individual population (control, Msh2-deficient, and MSM mice) would be maximized. Using Varscan2, we selected somatic variants that had at least 10X coverage in spleen samples, 5X coverage in skeletal muscle samples for the alternative allele and a P < 0.05. Additionally, variants from Varscan2 were selected only if also detected by GATK-MuTect2 and Strelka2 variant callers. We also excluded SNVs from lab strains using dbSNP142 from the mouse genome project. Using snpEFF, the obtained variants were annotated to find SNV-associated genes. MutPred2 (ref. 35) was used to predict the pathogenicity of missense variants. For SV detection, DELLY2 was used with default parameters59.

Single-cell transcriptome analysis of skeletal muscle regeneration

The single-cell transcriptome (scRNA-seq) data from Chromium 10X generated by De Micheli et al.42 was reanalyzed by maintaining the same parameters specified in the published study. We used Seurat 3.2.0 (ref. 60) and performed shared nearest neighbor clustering with 0.4 resolution to reproduce the optimal clusters. We used uniform manifold approximation and projection to visualize the individual clusters and the gene expression profiles. The markers representing individual clusters were predicted using the “FindAllMarkers” function from the Seurat package. The expression of SNV-associated genes was verified in the scRNA-seq dataset.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses of the experimental results from the mice were performed using the following parametric tests: unpaired t-test, one-way and two-way ANOVA with Tukey or Bonferroni´s multiple comparisons test. The data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. We used similar sample sizes to those reported in previous publications. These sample sizes were sufficient to test our hypothesis and perform statistical analysis. In addition, obtaining the different genotypes was challenging due to the use of triple transgenics and the attempt to have equal gender distributions within the sample groups. In addition, we always aim to follow the 3 Rs for animal research (refine, replace and reduce). The experiments were not randomized. Data collection was not performed blind to the conditions of the experiment. Blinding was used for immunofluorescence analysis. No animals or data points were excluded from the analysis. For the single-cell RNA-sequencing data, the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used, using the Benjamini Hochberg method for adjusting P values for multiple testing. Experimental replicates are biological. Graphs were plotted as mean ± standard deviation using GraphPad Prism software version 8.0.2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw data have been deposited to NCBI and can be accessed using BioProject ID PRJNA793847 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject”. The data can be accessed directly via: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA793847

The single-cell data derive from a previous study39 and were previously deposited in GEO with the accession number GSE143437. Mouse reference genome assembly GRCm38 (mm10) was used, obtained from the Genome Reference Consortium (GRC) release December 2011. dbSNP142 from the mouse genome project was used for SNP removal. All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript or are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: an expanding universe. Cell 186, 243–278 (2023).

Vijg, J. & Dong, X. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Somatic Mutation and Genome Mosaicism in Aging. Cell 182, 12–23 (2020).

Murphy, M. M., Lawson, J. A., Mathew, S. J., Hutcheson, D. A. & Kardon, G. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Dev. Camb. Engl. 138, 3625–3637 (2011).

Kucherlapati, M. H. et al. An Msh2 conditional knockout mouse for studying intestinal cancer and testing anticancer agents. Gastroenterology 138, 993–1002.e1 (2010).

Chester, N., Babbe, H., Pinkas, J., Manning, C. & Leder, P. Mutation of the murine Bloom’s syndrome gene produces global genome destabilization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 6713–6726 (2006).

Perez, K. et al. DNA repair-deficient premature aging models display accelerated epigenetic age. Aging Cell 23, e14058 (2024).

Schumacher, B., Pothof, J., Vijg, J. & Hoeijmakers, J. H. J. The central role of DNA damage in the ageing process. Nature 592, 695–703 (2021).

Vermeij, W. P. et al. Restricted diet delays accelerated ageing and genomic stress in DNA-repair-deficient mice. Nature 537, 427–431 (2016).

He, Y. et al. Metabolomic analysis of dietary-restriction-induced attenuation of sarcopenia in prematurely aging DNA repair-deficient mice. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 15, 868–882 (2024).

Franco, I. & Eriksson, M. Reverting to old theories of ageing with new evidence for the role of somatic mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 645–646 (2022).

Franco, I., Revêchon, G. & Eriksson, M. Challenges of proving a causal role of somatic mutations in the aging process. Aging Cell 21, e13613 (2022).

Franco, I. et al. Somatic mutagenesis in satellite cells associates with human skeletal muscle aging. Nat. Commun. 9, 800 (2018).

Franco, I. et al. Whole genome DNA sequencing provides an atlas of somatic mutagenesis in healthy human cells and identifies a tumor-prone cell type. Genome Biol. 20, 285 (2019).

Welch, J. S. et al. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell 150, 264–278 (2012).

Blokzijl, F. et al. Tissue-specific mutation accumulation in human adult stem cells during life. Nature 538, 260–264 (2016).

Hoang, M. L. et al. Genome-wide quantification of rare somatic mutations in normal human tissues using massively parallel sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 113, 9846–9851 (2016).

Milholland, B., Auton, A., Suh, Y. & Vijg, J. Age-related somatic mutations in the cancer genome. Oncotarget 6, 24627 (2015).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Clock-like mutational processes in human somatic cells. Nat. Genet. 47, 1402–1407 (2015).

Brazhnik, K. et al. Single-cell analysis reveals different age-related somatic mutation profiles between stem and differentiated cells in human liver. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax2659 (2020).

Meier, B. et al. Mutational signatures of DNA mismatch repair deficiency in C. elegans and human cancers. Genome Res. 28, 666–675 (2018).

Volkova, N. V. et al. Mutational signatures are jointly shaped by DNA damage and repair. Nat. Commun. 11, 2169 (2020).

van Oers, J. M. M. et al. The MutSβ complex is a modulator of p53-driven tumorigenesis through its functions in both DNA double strand break repair and mismatch repair. Oncogene 33, 3939 (2013).

Smith, J. A., Waldman, B. C. & Waldman, A. S. A role for DNA mismatch repair protein Msh2 in error-prone double-strand-break repair in mammalian chromosomes. Genetics 170, 355–363 (2005).

Georgiou, D., Monje-Garcia, L., Miles, T., Monahan, K. & Ryan, N. A. J. A focused clinical review of Lynch syndrome. Cancer Manag. Res. 15, 67–85 (2023).

Diouf, B. et al. Msh2 deficiency leads to dysmyelination of the corpus callosum, impaired locomotion, and altered sensory function in mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 30757 (2016).

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 153, 1194 (2013).

Wang, Y., Smith, K., Waldman, B. C. & Waldman, A. S. Depletion of the Bloom syndrome helicase stimulates homology-dependent repair at double-strand breaks in human chromosomes. DNA Repair 10, 416–426 (2011).

Sambasivan, R. et al. Pax7-expressing satellite cells are indispensable for adult skeletal muscle regeneration. Dev. Camb. Engl. 138, 3647–3656 (2011).

Lepper, C., Partridge, T. A. & Fan, C.-M. An absolute requirement for Pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. Dev. Camb. Engl. 138, 3639–3646 (2011).

Molina, T., Fabre, P. & Dumont, N. A. Fibro-adipogenic progenitors in skeletal muscle homeostasis, regeneration and diseases. Open Biol. 11, 210110 (2021).

Flores-Opazo, M. et al. Fibro-adipogenic progenitors in physiological adipogenesis and intermuscular adipose tissue remodeling. Mol. Aspects Med. 97, 101277 (2024).

Bosnakovski, D. et al. Prospective isolation of skeletal muscle stem cells with a Pax7 reporter. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio 26, 3194–3204 (2008).

Schultz, L. B., Chehab, N. H., Malikzay, A. & Halazonetis, T. D. p53 binding protein 1 (53BP1) is an early participant in the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks. J. Cell Biol. 151, 1381–1390 (2000).

Maréchal, A. & Zou, L. RPA-coated single-stranded DNA as a platform for post-translational modifications in the DNA damage response. Cell Res. 25, 9 (2014).

Pejaver, V. et al. Inferring the molecular and phenotypic impact of amino acid variants with MutPred2. Nat. Commun. 11, 5918 (2020).

De Micheli, A. J., Spector, J. A., Elemento, O. & Cosgrove, B. D. A reference single-cell transcriptomic atlas of human skeletal muscle tissue reveals bifurcated muscle stem cell populations. Skelet. Muscle 10, 19 (2020).

Cammas, A. et al. Destabilization of nucleophosmin mRNA by the HuR/KSRP complex is required for muscle fibre formation. Nat. Commun. 5, 4190 (2014).

Shen, Y. et al. Mutations in PNKD causing paroxysmal dyskinesia alters protein cleavage and stability. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 2322 (2011).

Johnson, A. N., Mokalled, M. H., Valera, J. M., Poss, K. D. & Olson, E. N. Post-transcriptional regulation of myotube elongation and myogenesis by Hoi Polloi. Dev. Camb. Engl. 140, 3645 (2013).

Sommerville, E. W. et al. Identification of a novel heterozygous guanosine monophosphate reductase (GMPR) variant in a patient with a late-onset disorder of mitochondrial DNA maintenance. Clin. Genet. 97, 276–286 (2020).

Winje, I. M. et al. Specific labelling of myonuclei by an antibody against pericentriolar material 1 on skeletal muscle tissue sections. Acta Physiol. 223, e13034 (2018).

De Micheli, A. J. et al. Single-cell analysis of the muscle stem cell hierarchy identifies heterotypic communication signals involved in skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Rep. 30, 3583–3595.e5 (2020).

Chen, D.-H. et al. Presence of alanine-to-valine substitutions in myofibrillogenesis regulator 1 in paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia: confirmation in 2 kindreds. Arch. Neurol. 62, 597–600 (2005).

Ghezzi, D. et al. Paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia is caused by mutations of the MR-1 mitochondrial targeting sequence. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 1058–1064 (2009).

Stefanova, E. et al. Clinical characteristics of paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia in Serbian family with Myofibrillogenesis regulator 1 gene mutation. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 21, 2010–2015 (2006).

Edelbrock, M. A., Kaliyaperumal, S. & Williams, K. J. Structural, molecular and cellular functions of MSH2 and MSH6 during DNA mismatch repair, damage signaling and other noncanonical activities. Mutat. Res. 0, 53–66 (2013).

Bellacosa, A. Functional interactions and signaling properties of mammalian DNA mismatch repair proteins. Cell Death Differ. 8, 1076–1092 (2001).

Dou, Y., Gold, H. D., Luquette, L. J. & Park, P. J. Detecting somatic mutations in normal cells. Trends Genet. TIG 34, 545 (2018).

Gawad, C., Koh, W. & Quake, S. R. Single-cell genome sequencing: current state of the science. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 175–188 (2016).

Bankhead, P. et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 16878 (2017).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Cibulskis, K. et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 213–219 (2013).

Kim, S. et al. Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nat. Methods 15, 591–594 (2018).

Koboldt, D. C. et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 22, 568–576 (2012).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6, 80 (2012).

McLaren, W. et al. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 122 (2016).

Rausch, T. et al. DELLY: structural variant discovery by integrated paired-end and split-read analysis. Bioinformatics 28, i333–i339 (2012).

Hao, Y. et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 293–304 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Lundin for his help with bioinformatic analysis, O. Pajonk for his technical assistance and all the participants of the CIMED network for muscle physiology for constructive discussions. We thank M. Bergö and F. Pietrocola for their comments on the manuscript.

We acknowledge support from the National Genomics Infrastructure in Stockholm and the SNP&SEQ Platform in Uppsala, funded by Science for Life Laboratory, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the Swedish Research Council. We acknowledge SNIC/Uppsala Multidisciplinary Center for Advanced Computational Science for assistance with massively parallel sequencing and access to the UPPMAX computational infrastructure and the Live Cell Imaging core facility/Nikon Center of Excellence at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, supported by the KI infrastructure council.

M.E. is supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the European Research Council (Advanced grant 2022-101097871), the Swedish Cancer Foundation and Center for Innovative Medicine (CIMED). P.V. is supported by the Loo and Hans Osterman Foundation for Medical Research and the Gun and Bertil Stohne Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.V. and M.E. came up with the concept and designed the study. L.G.M. designed the experiments for the revision. P.V., L.G.M., M.B., F.S, G.R. and I.F. performed the experimental work. S.S, H.T.H., D.P. and P.C. performed bioinformatics analysis. P.V., L.G.M., S.S., H.T.H., M.B., F.S., G.R., I.F. and M.E. analyzed and interpreted the data. P.V. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors critically revised the manuscript. P.V. and M.E. obtained the funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Aging thanks Vahab Soleimani, Jan Vijg and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Characterization of regeneration in Msh2-deficient TA.

(a) Hematoxylin-eosin staining of non-injured and regenerated TA after 3 cycles of injury and regeneration. (b) Quantification of fibers with centralized nuclei in non-injured and regenerated TA (Control n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Ctrl-non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 2.3e-14; Msh2-def. non-inj. vs Msh2-def. Regen. P = 2.8e-14. (c) Quantification of Msh2/Blm recombination in regenerated TA after 3 regeneration cycles (n = 3; P = 0.0005). (d) Msh2 immunofluorescence of regenerated TA. (e) Quantification of Msh2-positive centralized nuclei in regenerated TA (Control n = 4, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs Msh2-def P = 5.8e-07. (f) Picro Sirius Red staining of non-injured and regenerated TA after 3 regeneration cycles. (g) Quantification of Picro Sirius Red-stained muscle in non-injured and regenerated TA (Control n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Ctrl-Non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 0.0311; Msh2-def. non-inj. vs Msh2-def. Regen. P = 0.4906. (h) Pdgfrα immunofluorescence of non-injured and regenerated TA. (i) Quantification of Pdgfrα-positive cells in non-injured and regenerated TA after 3 cycles of regeneration (Control n = 4, Msh2-def. n = 3); Ctrl-Non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 0.8669; Msh2-def. non-inj. vs Msh2-def. Regen. P = 0.7195. (j) Pax7 immunofluorescence of non-injured and regenerated TA. (k) Quantification of Pax7-positive cells in non-injured and regenerated TA after 3 regeneration cycles (Control n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Ctrl-Non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 0.7764; Msh2-def. non-inj. vs Msh2-def. Regen. P = 0.9846. (l) Ki67 immunofluorescence of non-injured and regenerated TA. (m) Quantification of Ki67 positive cells in non-injured and regenerated TA after 3 cycles of injury and regeneration (Control-non-inj n = 6, Control-regen n = 9, Msh2-def-non-inj n = 3, Msh2-def-regen n = 3) Ctrl-Non-inj. vs Ctrl-Regen. P = 0.4816; Msh2-def. non-inj. vs Msh2-def. Regen. P = 0.9924. Panels a and f scale bars indicate 100 μm; panels d, h, j and l scale bars indicate 20 μm. Statistical test: c and e: unpaired t-test two tailed; b, g, i, k and m: one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test. Graphs b, c, e, g, i, k, and m present data as mean ± SD. Note: for panels a, b, d–m the control images and control quantifications correspond to those in Fig. 1b, c, e–m. h, j, l Arrows indicate positive nuclei/cells.

Extended Data Fig. 2 MSM mice accumulate more SVs than control and Msh2-deficient mice.

Quantification of somatic structural variants (SVs) in skeletal muscle cells by WGS of representative histological samples of regenerated TA from control, MSM and Msh2-deficient mice. Analysis was performed both on downsampled data (a) and non-downsampled data (b). BND = interchromosomal translocation, DEL = deletion, INV = inversion.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Somatic variants and corresponding genes related to muscle regeneration.

(a) Pcm1 immunofluorescence of regenerated TA. (b) Quantification of Pcm1-positive nuclei in regenerated TA (Control n = 3, MSM n = 4, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.5898, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.5022. (c) Expression of protein coding genes associated with somatic variants visualized in uninjured (Day 0) and post-days of injury (Day 2, 5, and 7) using UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection). (d) Boxplots with expression levels of protein coding genes associated with exonic somatic variants in Day 0, Day 5, and Day 7 in muscle associated cell types. The central line of the boxplots represents the mean value of the data. The edges of the boxes correspond to the 25th (Q1) and 75th percentile (Q3). The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles, and points beyond whiskers are outliers. P-values were determined using the Wilcoxon test and are denoted by *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, **** <0.0001, ns is non-significant and the p-values are adjusted for multiple testing correction by Benjamini Hochberg method Panel a scale bar indicates 20 μm. Panel b was analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test. Graph b presents data as mean ± SD.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Measurement of muscle fiber atrophy.

(a) Lamin B1 immunofluorescence of regenerated TA. Arrows indicate Lamin B1-positive and negative nuclei that are enlarged in the side pictures. Transmitted detection was used to visualize myogenic fibers. (b) Quantification of Lamin B1-positive centralized myonuclei in regenerated TA (Control n = 4, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.6948, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.2721. Panel a scale bar indicates 20 μm. Statistical test: b: one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test. Graphs b presents data as mean ± SD.

Extended Data Fig. 5 No abnormal myofiber sizes in non-injured TA from MSM and Msh2-deficient mice.

(a) Graphs displaying the size distribution of fibers across the different groups after 3 regeneration cycles in the contralateral non-injured TA. Curves illustrate the Gaussian distribution of fiber sizes. Double arrows show no shift in fiber size in MSM and Msh2-deficient mice compared to controls (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3). (b) Graph showing average cross-sectional area of fibers after 3 regeneration cycles regeneration in the contralateral non-injured TA (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.9844, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 9665. (c) Graph showing the fold change of normalized grip strength after every cycle of injury/regeneration in control, MSM and Msh2-deficient mice (Control n = 9, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.0048, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.0030. (d) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of non-injured right TA obtained from non-injured mice. (e) Quantification of centralized nuclei from non-injured right TA obtained from non-injured mice (Control n = 3, MSM n = 3, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.2104, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.1842. (f) Picro Sirius Red staining of non-injured right TA. (g) Quantification Picro Sirius Red-stained muscle connective tissue from non-injured right TA obtained from non-injured mice (Control n = 3, MSM n = 3, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.3673, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.9907. (h) Pax7 immunofluorescence of right non-injured TA obtained from non-injured mice. (i) Quantification of Pax7-positive cells in right non-injured TA obtained from non-injured mice (Control n = 3, MSM n = 3, Msh2-def. n = 3), Control vs MSM P = 0.1105; Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.4106. (j) Graph showing the fold change of normalized grip strength in uninjured mice after 3 cycles of injury and regeneration in non-injured (Control n = 3, MSM n = 9, Msh2-def. n = 3); Control vs MSM P = 0.3580, Control vs Msh2-def. P = 0.7917. Statistical test: b, e, g, i, j: one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test; C: two-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test. Graph a presents data only as mean without SD for clearer presentation. Graphs b, c, e, g, i, j present data as mean ± SD. Panels d and f scale bars indicate 100 μm; panel H scale bar indicates 20 μm.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data 1

VCF files from both the downsampled and non-downsampled analysis containing all structural variation data.

Supplementary Data 2

VCF files from the non-downsampled analysis containing all detected SNVs.

Supplementary Table 1

Table containing all exonic SNV and additional information, such as type of mutation, allele frequency or MutPred2 score.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Raw data and statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Raw data and statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Raw source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Raw data and statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Raw data and statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Raw data and statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Raw data and statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Raw data and statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Raw data and statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vrtačnik, P., Merino, L.G., Subhash, S. et al. Induced somatic mutation accumulation during skeletal muscle regeneration reduces muscle strength. Nat Aging 5, 1739–1749 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-025-00941-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-025-00941-y

This article is cited by

-

The hidden cost of somatic mutations on skeletal muscle regeneration

Nature Aging (2025)