Abstract

Background

There is an unmet need for treatment of long-term symptoms following COVID-19. Remdesivir is currently the only antiviral approved by the European Medicines Agency for hospitalised patients. Here, we report on the effect of remdesivir in addition to standard of care on long-term symptoms and quality of life in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 as part of the open-label randomised NOR-Solidarity trial (NCT04321616).

Methods

A total of 185 patients were included in the main trial, of which 118 (60%) were randomised to either remdesivir (n = 42; 36%) or a post-hoc defined control group composed of patients who received standard of care alone or standard of care with hydroxychloroquine (n = 76; 64%). Participants were given quality of life surveys to fill out to gauge their self-reported health over time (the COPD assessment test, the EQ-5D-5L and the RAND SF-36).

Results

Here we show that after three months, patients treated with remdesivir do not show significant improvements in stated health compared to those who were not. There are self-reported symptoms of fatigue [mean remdesivir group 2.6 (standard deviation 1.5) v control 2.1 (1.6), 95% confidence interval(CI) −1.17 to 0.15, p = 0.129], shortness of breath [3.0 (1.7) v 2.1 (1.8), 95% CI −1.53 to 0.16, p = 0.110] and coughing [1.8 (1.6) v 1.2 (1.5), 95% CI −1.3 to 0.33, p = 0.237] 3 months after randomisation assessed via the COPD Assessment Test.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that treatment with remdesivir during hospitalisation does not provide any clinically relevant long-term benefit.

Plain language summary

Remdesivir is a medicine that is used to treat people with COVID-19. It has been found to help people get better faster, but we did not know whether it also relieved them of long-term symptoms such as persistent coughing, fatigue, or shortness of breath. To research this, we randomly assigned hospitalised patients with COVID-19 to either remdesivir on top of their normal care, or only normal care, with or without hydroxychloroquine (a drug later found to have no effect on COVID-19). We then compared participant’s symptoms after 3 months. Our results show that there is probably no benefit of using remdesivir during hospitalisation for long-term symptom relief.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, was first identified in Wuhan, China in December 20191, and emerged as a global pandemic around January 20202. In response to this international threat, the World Health Organisation (WHO) mobilised its resources to recommend strategies for prevention and, as the pandemic progressed, identification of drugs that should be examined for their efficacy for treatment of this quickly evolving virus. The NOR-Solidarity trial was an independent add-on open-label randomised clinical trial to the WHO Solidarity trial, assessing the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine and remdesivir in addition to standard of care (SoC) (WHO Solidarity ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT04315948; NOR-Solidarity ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT04321616). The trial ended early (October 2020) for several reasons including lack of includable patients and low mortality. Further, an interim report from the main WHO Solidarity trial showed that there was little to no effect of the drug on patients with only mild disease. Remdesivir is now approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and is the recommended antiviral for hospitalised patients. It has been shown to benefit pre-hospitalised patients3 and in a recent individual patient meta-analysis (including data from WHO Solidarity4), a moderate benefit in hospitalised patients not on mechanical ventilation5. Conversely, hydroxychloroquine has not been shown to have any beneficial effects6.

In addition to clinical endpoints, NOR-Solidarity collected symptom scores from Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) 1 and 3 months after randomisation. These were not previously reported since the 90-day period had not yet expired for all patients prior to publication of the initial report. Herein we report the findings from analyses looking into the long-term effect of remdesivir on symptom scores and PROMs in subjects hospitalised for moderate or severe COVID-19; moderate disease was defined as 4–5 on the WHO COVID clinical progression scale, while severe disease was defined as 6–9 on this same scale7. These are secondary analyses and should be considered supplementary to the primary analyses8.

Here we show that after three months, patients treated with remdesivir do not show significant improvements in stated health compared to those who were not. A figure giving the main results can be viewed in the Supplementary Results (page S31).

Methods

Participating sites

Twenty-three hospitals, covering all 4 Regional Health Authorities in Norway, participated in NOR-Solidarity.

Inclusion criteria

The main criteria for inclusion were adult patients, 18 years and older, with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by PCR, admitted to the hospital ward or intensive care unit (ICU). Subjects (or legally authorised representative) provided informed consent prior to initiation of the study. Patients must have had no transfer anticipated within 72 hours to a non-study hospital. Also see Supplementary Methods: Inclusion Criteria in the supplementary information, Section 3.1, page S4.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were severe co-morbidity with life expectancy <3 months according to investigators assessment, ASAT/ALAT > 5 times the upper limit of normal, acute co-morbidity within 7 days before inclusion such as myocardial infarction, known intolerance to the available study drugs, pregnancy or breastfeeding, any reason why, in the opinion of the investigators, the patient should not participate, participation in a potentially confounding drug or device trial during the course of the study, a prolonged QT interval (>470 ms), already receiving any of the study drugs, and patients with psoriasis. Patients on concomitant medications which were part of the list of prohibited medications had to be excluded from the current study. Prohibited medications included haloperidol, carbamazepine, phenytoin, rifampin, phenobarbital, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, nevirapine, ritonavir and sodium valproate/valproic acid. Also see Supplementary Methods: Exclusion Criteria in the supplementary information, Section 3.2 and 3.3, page S4.

Informed consent

This study included patients who were seriously ill with COVID-19, and so both patients or their legally authorised representatives were able to provide informed consent prior to their inclusion in this open-label, randomised study. All possible efforts were made to obtain informed consent from the patient themselves prior to inclusion, but where a patient was not capable of signing an informed consent form, their legally authorised representative (the person designated by the hospital as able to make decisions on behalf of the patient while they were incapacitated) could sign on their behalf. The patient was asked to confirm their consent at the earliest possible point in their recovery. The ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were always adhered to.

Procedures

In the early stages of the trial, patients were randomly assigned to either the standard of care (SoC) of the local hospital, or SoC plus remdesivir or hydroxychloroquine (HCQ). Later, due to recommendations by the WHO and research showing hydroxychloroquine was not helpful for the treatment of COVID-198, patients were only randomised to SoC or SoC plus remdesivir. Due to the considerable evidence for the lack of efficacy of hydroxychloroquine, we only considered patients who were eligible for randomisation to the SoC + remdesivir arm and combined those who were randomised to SoC or SoC plus hydroxychloroquine into a single control group, hereafter termed SoC ± HCQ. More information about NOR-Solidarity and its procedures, protocol, and statistical analysis plan are provided in the primary publication8. Information about the interventions themselves is given in the supplementary information, Sections 4.1 and 4.2, page S4-5. For information on the randomisation procedure, please see the Supplementary Information, Section 5, page S5.

Outcomes

In our initial study, we looked at whether patients treated with standard of care plus remdesivir received any medical benefit from their treatment in comparison to a control group who received only standard of care, and we found that the remdesivir-treated patients did not receive any benefit over the control group8. Although these results were neutral, we still wanted to test whether the patients who received remdesivir received any longer-term benefits from their treatment in comparison to the control group who did not receive it. Three pre-specified primary endpoints were designated as self-reported symptoms of (i) fatigue, (ii) shortness of breath and (iii) coughing 3 months after randomisation as measured on the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Assessment Test (CAT). The primary outcomes were chosen as they relate to symptoms commonly indicative of post-acute sequelae SARS-CoV-2 infection (commonly termed long COVID)9, which has been shown to affect between 33%10 and 71.2%11 of patients10,11,12.

The secondary endpoints were 1) the three primary endpoints measured after 1 month, 2) the total CAT score from all 8 questions after 1 and 3 months, 3) the EQ-5D-5L index value after 3 months, and 4) the nine scale scores of the RAND 36-item health survey (SF-36) after 3 months.

Further details of the primary and secondary endpoints, including references to methodology, can be found in the statistical analysis plan (SAP) provided in the Supplementary Information (Section 7 page S14-S30). Statistical code used in the analysis may be obtained from the following repository: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HGRVP13.

Questionnaires

As noted above, this study used three separate questionnaires to collect patient-reported outcome information. The first, the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Assessment Test (CAT)14, was developed to monitor quality of life for patients with COPD and is not validated for COVID-19. However, it is a robust test that is able to help patients quantify fatigue, shortness of breath and coughing using a simple 0 (no symptom) to 5 (having the symptom all the time) scale. This test consists of 8 questions, the results of which were summed to provide a score between 0 and 40. This test was completed at months 1 and 3 post-inclusion to give a view of change in respiratory symptoms, specifically, over time.

The second test used was the standardised EQ-5D-5L15 which is used to determine overall health outcomes for 5 areas related to overall health (dimensions) where patients may make one of 5 potential choices (levels). The test was scored using the UK Time Trade-off value set and self-rated health on the EQ visual analogue scale (VAS 0-100) after 3 months, which gave a score off between 0 (the worst health imaginable) and 100 (the best health imaginable). This test was administered at month 3 post-inclusion.

The final test administered was the SF-3616, which is a 36-item survey of health in eight areas including physical and psychosocial concepts. This test was scored using the scoring rules version 1.0. Patients were given this test at month 3 post-inclusion.

Patients were given the test to complete on their own, with no intervention from any caregiver. The surveys were sent out and received using Viedoc17.

Statistics

For the primary analysis, no consideration of the required sample size was done.

Before performing any comparative analyses on the outcomes presented here, a PROM-specific SAP was written and approved. As these are supplementary analyses, there were no adjustments for multiple testing, and significant findings should not be interpreted conclusively. The efficacy of remdesivir was compared to concurrent controls randomised to either SoC alone or in combination with hydroxychloroquine.

All the analyses were done using randomised patients with at least one post-randomisation observation (full analysis set) using two-sample t-tests, and estimated differences between the groups are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Missing data due to death was imputed with worst outcome. Other missing data was handled by multiple imputation with chained equations (MICE) with age, sex, hospital duration, location after discharge, baseline WHO clinical progression, symptom duration before admission, viral load, c-reactive protein, and ferritin at baseline. Note that treatment was deliberately not part of the imputation model to provide conservative estimates. A post-hoc sensitivity analysis has been included, where missing data due to death have been multiply imputed according to the not-at-random fully conditional specification procedure18.

The seed of the multiple imputation was set to 20,230,518 (date of signing the SAP).

The following sensitivity analyses were performed: 1) same as primary but excluding patients randomised to hydroxychloroquine, 2) complete case analysis with t-test, and 3) complete case analysis with Mann-Whitney U test.

Subgroup analyses were performed for the primary endpoints according to the following subgroups: (1) WHO state at baseline (Moderate i.e. no or low-flow ventilation vs Severe i.e. high-flow or mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), (2) symptom duration at baseline (<7 days vs ≥7 days), (3) age at baseline (<60 vs ≥60 years), (4) viral load at baseline (<overall median vs ≥ overall median), (5) CRP at baseline (<overall median vs ≥ overall median), and (6) ferritin at baseline (<overall median vs ≥ overall median). The subgroup analysis was performed by an Analysis of Covariance model including a treatment / subgroup interaction term. Missing data was handled using MICE as it was for the primary endpoint.

The statistical analysis plan is shown in full in Section 7 of the supplementary information, pages S14-S30. All statistical analyses were done using R version 4.3.2 (R Foundation).

Ethical statement

The NOR-Solidarity trial was approved by the regional ethics committee (No. 118684) and by the Norwegian Medicines Agency (No. 20/04950-23) and is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (ID No. NCT04321616) and EudraCT (CTR No. 2020-000982-18). The trial was governed and monitored under legislation and regulations set out in the Declaration of Helsinki and ICH E6 (R2) Good Clinical Practice.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Participants

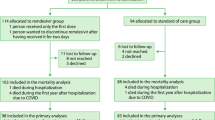

NOR-Solidarity began inclusion on 28 March 2020 and included a total of 185 patients, accounting for about one-fourth of all hospitalised patients in Norway, enrolling its final patient on the 4 October 2020. 67 patients were included before remdesivir was available as an active treatment; these 67 non-concurrent inclusions have been excluded from this study. Of the remaining 118 patients, 57 were randomised to SoC, 19 to SoC + hydroxychloroquine (hereinafter called SoC ± HCQ, n = 76) and 42 to SoC + remdesivir. These 118 participants had at least one post-randomisation observation and were included in the full analysis set. The patient flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Sex distribution was relatively equal for both groups with a higher number of men. The majority of patients were admitted to the ward with moderate disease. Generally, the groups were balanced between the treatments as seen in Table 1.

Outcomes

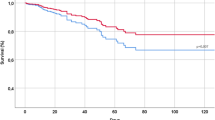

The primary outcomes, CAT fatigue, shortness of breath and coughing symptom scores at 3 months were numerically higher in the remdesivir group, but without reaching any indication of harm (Table 2). The confidence intervals indicate, however, that we can exclude any clinical benefit from remdesivir on the 3 months symptom scores. The sensitivity analyses presented in the Supplementary Results (Section 6, Page S5–S9) strengthen this conclusion.

The results of the secondary endpoints are detailed in Table 2. Again, the results are numerically in favour of the control group without reaching an indication of remdesivir being harmful to long-term quality of life. Sensitivity analyses are presented in the Supplementary Results (Section 6, Page S5).

Subgroup analyses

The subgroup analyses were performed using the subgroups as outlined in the Statistical Analysis section and presented in the Supplementary Results (Section 6.2, Page S6-S9). There were no indications of any treatment modifiers. A weak interaction signal was observed between long and short symptom duration at baseline.

Concomitant medication

An overview of concomitant medication is given in Table 1.

Discussion

These secondary analyses of the Nor-Solidarity trial focused on long-term symptom burden in COVID-19 clearly indicate that treatment with remdesivir during hospitalisation does not provide any clinically relevant long-term benefit. This is in line with the findings in Nevalainen et al. 19 who were unable to find any benefit of this anti-viral drug 1-year after randomisation. Our results complement these findings by filling the gap between time in-hospital and their one-year follow-up.

While these secondary analyses are without the ability to make conclusive claims both due to lack of adjustment for multiplicity and lack of power, it is interesting to observe the apparent lack of effect of remdesivir. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for total CAT is identified as a score of 220. Assuming equal weight of the items this translates to an item specific MCID of 2/8 = 0.25. The 95% confidence interval of CAT fatigue, shortness of breath and total score excludes a clinically relevant benefit of remdesivir as defined by the MCID. One possible explanation is that the patients were treated too late to effect any real change. Other trials have reported that patients who are treated early with remdesivir do better overall than patients treated later, and also better in moderate disease compared to severe disease21,22. Boglione et al. 22 in particular noted that patients who had undergone treatment with remdesivir were more likely to be doing better on the post-COVID-19 functional status scale (PCFS). However, their study was observational, including only patients with less severe disease. Therefore, it is possible that although the patients in this trial were hospitalised for primary COVID-19, the fact that they were admitted with moderate or even severe disease could point to the treatment being applied too late. The weak treatment interaction signal with respect to symptom duration at baseline may support this hypothesis, as indicated by results from recent studies using early treatment with the antiviral agent nirmatrelvir to prevent long COVID symptoms23,24.

The strength of our study is that we gathered data on long-term symptoms among a relatively large proportion of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 in Norway. Also, we were among the few studies who gathered long-term symptoms as prespecified in the trial protocol.

A major limitation was that the rate of missing data was high, reaching 15 out of 42 (35.7%) of the 3-month CAT scores in the remdesivir group and 23 out of 76 (30.2%) in the control group. Further, that we only followed the participants for 3 months, that the trial was not placebo controlled, and that it was not properly powered. We have adjusted for the missing data by applying a comprehensive and conservative primary approach using multiple imputations. Sensitivity analyses with other approaches to handling of missing data showed even stronger indications of lack of benefit of remdesivir. In our analyses we excluded four evenly distributed randomised participants; one was wrongly included, and three withdrew consent before any treatment could be given. We argue that these exclusions do not induce any bias since they withdrew so shortly after randomisation or did not belong to the target population. While 3 months is considered a long-term follow-up in this setting, it would have been even better if we had also repeated the measurements after 6 and 12 months. As well, since these are subjective measures, the symptom scores might have been influenced by the participant knowing the allocated treatment. The trial was performed in the early stages of the pandemic, and the findings may not be generalisable to the current status with different variants and vaccination use. Finally, while our outcomes were the best available when the protocol was written, they do not specifically capture the potential effect of the development of long COVID.

In conclusion, our findings do not support the use of remdesivir to lessen the long-term symptom burden of patients who have been hospitalised for COVID-19. Earlier treatment might have an impact on the efficacy of remdesivir, but this study was not designed to assess this hypothesis.

Data availability

The anonymised data are openly available via osf.io at the following URL: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HGRVP13.

Code availability

All computer code with a complete audit trail through GitHub is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HGRVP13.

References

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 395, 497-506 (2020).

World Health Organization. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation (WHO); 2020; 30 January 2020. Available at https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov).

Brown, S. M. et al. Consistent effects of early remdesivir on symptoms and disease progression across at-risk outpatient subgroups: treatment effect heterogeneity in PINETREE study. Infect. Dis. Ther. 12, 1189–1203 (2023).

World Health Organization Solidarity Trial Consortium. Remdesivir and three other drugs for hospitalised patients with COVID-19: final results of the WHO Solidarity randomised trial and updated meta-analyses [published correction appears in Lancet. 2022 Oct 29;400(10362):1512]. Lancet. 399, 1941–1953 (2022).

Amstutz, A. et al. Effects of remdesivir in patients hospitalised with COVID-19: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 11, 453–464 (2023).

Tang, W. et al. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with mainly mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019: open label, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 369, m1849 (2020).

WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection. A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research [published correction appears in Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;20(10):e250]. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, e192–e197 (2020).

Barratt-Due, A. et al. Evaluation of the effects of remdesivir and hydroxychloroquine on viral clearance in COVID-19: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 174, 1261–1269 (2021).

World Health Organization. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a delphi consensus, Accessed 14 March 2023 (World Health Organization, 2021).

Demko, Z. O. et al. Two-year longitudinal study reveals that long COVID symptoms peak and quality of life nadirs at 6-12 months postinfection. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 11, ofae027 (2024).

Kim, Y. et al. Long COVID prevalence and impact on quality of life 2 years after acute COVID-19. Sci Rep 13, 11207 (2023).

Sun C., Liu Z., Li S., Wang Y. & Liu G. Impact of Long COVID on Health-Related Quality of Life Among Patients After Acute COVID-19 Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study. Inquiry. (2024).

Olsen, I. C. & Barrat-Due, A. (2023) Nor-Solidarity: Patient Reported Outcome Measures paper, OSF. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HGRVP (Accessed: 07 October 2024).

CAT Assessment Test. www.catestonline.org. https://www.catestonline.org.

EuroQol. EQ-5D−5L. EuroQol. (2009). https://euroqol.org/information-and-support/euroqol-instruments/eq-5d-5l/.

RAND. 36-Item Short Form Survey from the RAND Medical Outcomes Study. Rand.org. (2019). https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form.html.

Viedoc - The New Standard in eClinical Data Management | Viedoc. Viedoc. (2023). Accessed 14 August 2024. https://www.viedoc.com.

Tompsett, D. M., Leacy, F., Moreno-Betancur, M., Heron, J. & White, I. R. On the use of the not-at-random fully conditional specification (NARFCS) procedure in practice. Stat. Med. 37, 2338–2353 (2018).

Nevalainen, O. P. O. et al. Effect of remdesivir post hospitalization for COVID-19 infection from the randomized SOLIDARITY Finland trial. Nat Commun 13, 6152 (2022).

Kon, S. S. et al. Minimum clinically important difference for the COPD Assessment Test: a prospective analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2, 195–203 (2014).

Beigel, J. H. et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - final report. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1813–1826 (2020).

Boglione, L. et al. Risk factors and incidence of long-COVID syndrome in hospitalized patients: does remdesivir have a protective effect? QJM 114, 865–871 (2022).

Xie, Y., Choi, T. & Al-Aly, Z. Association of Treatment With Nirmatrelvir and the Risk of Post-COVID-19 Condition. JAMA Intern. Med. 183, 554–564 (2023).

Bajema, K. L. et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 treatment with nirmatrelvir-ritonavir or molnupiravir among U.S. veterans: target trial emulation studies with one-month and six-month outcomes. Ann. Intern. Med. 176, 807–816 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Program of Clinical Therapy Research in the Specialist Health Services, Norway (Grant No. 2020201 to NOR-SOLIDARITY trial). Serology was completed using a grant from South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (Grant No. 10357) and with support from Oslo University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

P.A., A.M.D.R. and A.B.D. were responsible for the conceptualisation, methodology, acquisition of resources, supervision, and project administration. P.A., M.T., A.M.D.R., A.B.D. and T.K. were responsible for investigation. I.C.O. was responsible for conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, and writing (original draft preparation, review, and editing). T.P.B. was responsible for writing (original draft preparation, review, and editing), visualisation, and formal analysis. P.A., M.T., A.M.D.R., A.B.D., K.N.H. and T.K. were responsible for writing (review).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

None of the authors declare any competing interests. The formal sponsor, Oslo University Hospital, was not directly (other than as an employer of the study group) involved in any of the study stages including study design, data analysis or manuscript preparation.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Viet-Thi Tran, Guillaume Lingas and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patrick-Brown, T.D.J.H., Barratt-Due, A., Trøseid, M. et al. The effects of remdesivir on long-term symptoms in patients hospitalised for COVID-19: a pre-specified exploratory analysis. Commun Med 4, 231 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-024-00650-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-024-00650-4