Abstract

Background

Due to waning immunity and emerging variants, protection following primary intramuscular Covid-19 vaccinations is decreasing, so health agencies have been proposing heterologous booster vaccinations. Here, we report immunogenicity and safety evaluation of heterologous booster vaccination with an intranasal, adenovirus vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (BBV154) in healthy adults, who were previously primed with two doses of either Covaxin® or Covishield™. We compare results with use of a homologous booster vaccination combination.

Methods

This was a randomized, open-label phase 3 trial conducted to evaluate immunogenicity and safety of a booster dose of intranasal BBV154 vaccine or intramuscular EUA approved Covid-19 vacines in India. Healthy participants of ≥18 years age with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, who received two doses of Covaxin® or Covishield™ at least 6 ± 1 months earlier were enrolled. The primary outcome was the neutralising antibody titers against wild-type virus using a plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT50). Other outcomes measured were humoral (IgG), mucosal (IgA) and cell mediated responses. The protocol was registered #NCT05567471 and approved by National Regulatory Authority (India) #CTRI/2022/02/039992.

Results

In this phase 3 trial, a total of 875 participants were randomized into 5 Groups in a ratio of 2:1:2:1:1 to receive either booster dose of BBV154 or Covaxin or Covishield. Based on per-protocol population, at Day 56, neutralization antibody titres were 564.1 (479·1, 664·1), 578.1 (436·9, 764·9), 655.5 (533·3, 805·8), 625.4 (474·7, 824·0), 650.1 (519·7, 813·1) for Group 1 to 5 respectively. This study was conducted, whilst the Omicron variant was prevalent. There were varying levels of severity of infection across different study sites with varied baseline antibody titers. Consequently, the average neutralization (PRNT50) antibody titers are similar across all Groups on day 56 and exhibited large differences within the Group, depending on the study site. All booster vaccinations are well tolerated and reported no serious adverse events; in particular, study participants boosted with BBV154 had significantly fewer solicited local adverse events than those primed and boosted with Covishield.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate that impact of booster across different cohorts is governed by infection status of the individual and geographical diversity, thus necessitating large cohorts, well distributed studies before Covid-19 booster effects are interpreted.

Plain language summary

We undertook a clinical trial to compare the booster dose effect of two currently used COVID vaccines (Covaxin® or Covishield™), with a newly developed intranasal COVID vaccine. The booster dose was given 6 months after two initial doses of COVID vaccines. We measured levels of antibodies, which are proteins that help the body to identify and destroy the SARS-CoV-2 virus following vaccination. The effect on antibodies was similar for all vaccination groups, whilst with the new vaccine there were fewer adverse events. This data, combined with the ease of administration, confirms that our new intranasal vaccine is safe and effective and can therefore be included in vaccination programs for COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since early 2020, millions of people have been infected with SARS-CoV-21. The global rollout of Covid-19 vaccines has played a critical role in reducing pandemic spread, disease severity, hospitalizations, and deaths2. However, current licensed Covid-19 vaccines are all designed for intramuscular (IM) immunization, and these vaccines failed to block SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission partially due to the lack of mucosal immunity3,4. Furthermore, current vaccines are reported to have diminished efficacy against emerging VOCs even after three-dose schedules5, highlighting the need for effective heterologous booster vaccinations. Evidence from previous studies suggest that the heterologous boosting with vector-based or mRNA vaccines, to subjects primed with inactivated vaccines is well tolerated and elicits superior immune responses compared with homologous vaccine boosters6,7. In addition, there is an urgent need to adopt next-generation Covid-19 vaccine strategies that meet the challenges of VOCs and the limited durability of first-generation vaccine-induced immunity. Several publications reported that mucosal boost strategies may offer promising results, when compared to intramuscular route of administration8. A recent study of heterologous boosting with an orally administered aerosolized Ad5-nCoV was found to be safe and highly immunogenic in adults primed with two doses of CoronaVac compared with a homologous booster dose of CoronaVac9.

In this context, Bharat Biotech (BBIL) developed BBV154, a chimpanzee adenovirus-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine encoding a prefusion-stabilized spike protein, formulated for intranasal delivery. Preclinical virus challenge studies performed earlier in K18-hACE2 transgenic mice showed superior immunity after a single intranasal dose of BBV154 compared with one or two intramuscular immunizations of the same dose of the same vaccine10. Additionally, one intranasal dose of BBV154 prevented upper and lower respiratory tract infection and inflammation by SARS-CoV-2 in highly susceptible K18-hACE2 transgenic mice, Syrian golden hamsters & rhesus macaques10,11,12. Intranasal administration of two doses of BBV154 also induced high neutralization antibody titers and salivary IgA binding titers, compared to intramuscular administration of COVAXIN, in Phase 3 clinical trial, and met the predefined superiority criterion13.

Here, we report the findings on immunogenicity and safety of intranasal BBV154 as a heterologous booster in participants, who were previously primed with two doses of licensed intramuscular Covid-19 vaccine in a phase 3 controlled, randomized, open-label trial. Wherein, we also compared data of BBV154-boosted subjects with heterologous (Covishield, followed by Covaxin boosting) and homologous booster vaccinations of Covishield and Covaxin. Our findings show similar immunological responses, in both homologous and heterologous series, with a significant enhancement of T cell memory and IgG/IgA secreting plasma B cells in intranasal booster dose.

Methods

Trial design and participants

The study was a randomized, open-label, multicentre trial to evaluate the immunogenicity and safety of a booster dose of intranasal BBV154 vaccine with homologous and heterologous booster doses of Covaxin or Covishield in healthy male and nonpregnant female volunteers across nine hospitals. The trial was approved (CTRI/2022/02/039992) by the National Regulatory Authority (India) and the respective Ethics Committees (Supplementary Table 1) and was conducted in compliance with all International Council for Harmonization (ICH) Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocol was registered on clinicaltrials.gov: NCT05567471.

Healthy participants were ≥18 years of age with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, who received a full Covid-19 vaccine regimen (two doses) available (Covaxin® and Covishield™) under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) at least 6 ± 1 months earlier were enrolled between 26 February 2022 to 30 March 2022. Proof and date of vaccination was confirmed from the electronic Covid-19 certificate generated by the CoWIN app—the digital vaccination tracker in India. Other inclusion criteria includes enrolled participants should remain in the study area for the entire duration of the study, not participating in another clinical trial at any time during the study period, and being willing to allow their biological samples to be stored for future research. For a female participant of child-bearing potential, they needed to plan to avoid becoming pregnant (use of an effective method of contraception or abstinence) from the time of study enrollment until at least 4 weeks after the vaccination. All participants were screened for eligibility based on their health status, including their medical history, vital signs, and physical examination results, and were enrolled after providing signed and dated informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: Participants with known history of COVID-19 infection; women of child-bearing potential (either by a positive serum pregnancy test during screening within 45 days of enrollment or positive urine pregnancy test within 24 h of administering of vaccine; having temperature >38.0 °C (100.4 °F) or having symptoms of an acute self limiting illness such as an upper respiratory infection or gastroenteritis within 3 days prior to vaccination; medical problems because of alcohol or illicit drug use during the past 12 months; receipt of an experimental agent (vaccine, drug, device, etc.) within 60 days before enrollment or expects to receive an investigational agent during the study period; receipt of any licensed vaccine within four weeks before enrollment in this study; known sensitivity to any ingredient of the study vaccines, or a more severe allergic reaction and history of allergies in the past; receipt of immunoglobulin or other blood products within the three months prior to vaccination in this study; immunosuppression because of an underlying illness or treatment with immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs or use of anticancer chemotherapy or radiation therapy within the preceding 36 months; long-term use (>2 weeks) of oral or parenteral steroids (glucocorticoids) or high dose inhaled steroids (>800 mcg/day of beclomethasone dipropionate or equivalent) within the preceding six months (nasal and topical steroids are allowed); any history of anaphylaxis in relation to vaccination; history of any cancer or history of severe psychiatric conditions likely to affect participation in the study; a bleeding disorder (e.g., factor deficiency, coagulopathy or platelet disorder, or prior history of significant bleeding or bruising following IM injections or venepuncture); any other serious chronic illness requiring immediate hospital specialist supervision; and any other condition that, in the opinion of the investigator, would jeopardize the safety or rights of a volunteer participating in the trial or would render the subject unable to comply with the protocol.

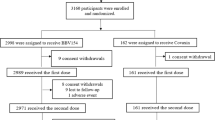

Trial participants were randomized 2:1:2:1:1 into five unequal groups using block size of seven (Fig. 1); Group 1 consisted of Covaxin recipients (n = 250) boosted with intranasal BBV154; in Group 2, Covaxin recipients (n = 125) received a Covaxin booster; in Group 3, Covishield recipients (n = 250) received an intranasal BBV154 booster; in Group 4, Covishield recipients (n = 125) received a Covaxin booster, and in Group 5, Covishield recipients (n = 125) received a Covishield booster. Sclin Soft Technologies, a contract research organization, did the randomization, data management, statistical analysis, and report writing.

Trial vaccines

BBV154 (Bharat Biotech, Hyderabad, India) is an intranasal chimpanzee Adenovirus-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine encoding a prefusion-stabilized spike (Wuhan) protein. Each dose of BBV154 was formulated in 0·5 mL. For administration, a sterile disposable dropper was fixed on top of the opened vaccine vial, the participant was instructed to lie down with the head slightly tilted back and the chin facing the ceiling, and 0.25 mL (4 drops) of vaccine were administered into each nostril. The participant was asked to remain lying down for 30 s to ensure the proper spread of the vaccine at the mucosal site.

Covaxin (Bharat Biotech, Hyderabad, India), is an intramuscular whole-virion inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. The vaccine strain, NIV-2020-770 contains the D614G mutation, which is characterized by an aspartic acid to glycine shift at amino acid position 614 of the spike protein14,15,16. Each 0.5 mL dose contains 6 µg of virus antigen formulated with Algel-IMDG, an imidazoquinoline class molecule that is a Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7/8 agonist (IMDG) chemisorbed onto Algel.

Covishield [ChAdOx1, manufactured by Serum Institute of India Pvt Ltd, Pune, India] is an injectable chimpanzee Adenovirus-based SARS-CoV-2 encoding a wild-type spike protein vaccine17. All vaccines were stored at 2–8 °C and required no on-site reconstitution.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the neutralizing antibody titer against wild-type virus using a plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT50) at Bharat Biotech. Secondary outcomes were humoral (IgG), mucosal (IgA) and cell-mediated responses and the number and percentage of participants with solicited local and systemic reactogenicity within 2 h and seven days after vaccination. The unsolicited adverse events were recorded within 28 days after vaccination. Exploratory outcomes were cross-neutralization antibody titers against variants (VOCs).

Procedures

On Day 0, following the baseline blood draw, participants in the BBV154 groups (Group 1 & 3) received intranasal vaccine and those in the Covaxin (Group 2) and Covishield groups (Group 5) received intramuscular injections of the respective vaccines. Participants in Group 4, who had two shots of Covishield, received Covaxin as a heterologous booster. Participants, investigators, study coordinators, and study-related personnel, were aware of the treatment group allocation (excluding the sponsor). Participants were observed for 30 min post-vaccination to assess the immediate reactogenicity, and then recorded solicited local and systemic reactions and body temperature daily for 7 days with telephone calls to ensure compliance. Any unsolicited adverse events were reported by the participants throughout the study. Study investigators graded adverse events according to the severity score (mild, moderate, or severe) and whether they were related or not related to the investigational vaccine, as predefined in the Protocol (Supplementary Data 2). All the participants attended follow-up visits for blood draws up to day 56 and for safety assessments up to 6 months, and the trial was completed.

Immunogenicity analyses

Blood samples were collected from all sites on Day 0, 28, and 56, but subset of saliva samples were collected from one site at Day 0, 28, and 56 (St. Theresa Hospital, Hyderabad), considering the delay in sample processing from the other sites. All serum and saliva samples were analysed in a blinded manner at Bharat Biotech. Neutralizing antibody titers against live ancestral (Wuhan) and Omicron sublineage (BA.1, BA.2, BA.2.1.2, and BA.5) SARS-CoV-2 were determined by validated PRNT50 assay18,19. IgG and IgA responses in serum and secretory IgA in saliva against the spike (S1) protein of SARS-CoV-2 were assessed as secondary outcomes by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and are expressed as geometric mean titers (GMTs).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from blood, collected on Days 0, 28, and 56 from consented participants at four sites (St. Theresa Hospital, Hyderabad; Vagus Super Speciality Hospital, Bangalore; ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Faridabad, Haryana; All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi); 40 participants each in Groups 1 and 3 and 20 participants each in Groups 2, 4 and 5. In order to isolate good-quality PBMCs and to reduce the expected delays in the sample process, blood samples were collected from selected sites. PBMCs collected at all time points were used for the evaluation of cell-mediated immunity (both T and B cells) by ELISpot and AIM (activation induced marker) assays at Immunitas Biosciences (Bangalore, India) in a blinded manner. Details of all assay methods are in the Supplemental Methods p.16–p.18.

Statistical analysis

Based on previous data, we assumed a standard deviation of log10 (titer) of 0.4 for BBV154 and 0.6 for Covaxin and Covishield. BBV154 was considered non-inferior to Covaxin and Covishield as a booster if the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the ratio of GMTs at Day 56 (GMT for BBV154 boost/GMT for Covaxin or ChAd-Ox- boost) had a lower bound ≥2/3. With sample sizes for analysis of 236 for BBV154 and 118 for Covaxin and Covishield and a true underlying GMT ratio of 1, each comparison had approximately 82% power to show non-inferiority. Assuming ~5% loss in each group due to withdrawal, loss to follow-up, etc., we enrolled 250 study participants in each of the groups receiving a BBV154 as booster dose and 125 in each of the Covaxin and Covishield booster groups. Sample size estimation was performed using PASS 13 software (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah, USA).

Safety endpoints are described as group frequencies (%). GMTs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for immunological endpoints. For continuous variables (below 20 observations), medians and IQRs are reported. CI estimation for the GMT was based on log10 (titer) and the assumption that log10 (titer) was normally distributed. GMT ratios for the Wuhan strain compared to an Omicron lineage across all groups were evaluated by a two-sided paired t-test on log10 (titer). Comparisons of GMT ratios for pairs of Omicron lineages used two-sided two-sample t-tests, if PRNT50 for the two lineages was evaluated for the same subset of participants, and two-sided paired t-tests if PRNT50 for the two lineages was evaluated for different subsets of participants. ANOVA and t-tests were also used in comparisons of other antibody endpoints. Statistical analysis of cell-mediated responses were performed using Graph-Pad Prism software. ANOVA (Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons) was performed to compare the CMI responses at different time points (day 0, 28, and 56) within each group. Further, all five vaccine groups were compared at individual time points by ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons). p values estimated by normal approximation with no continuity correction. Proportions of study participants with adverse events were compared using χ2 tests and, if significant, score tests with p value adjusted for multiple comparisons20. P values ≤0·05 (two-sided when sidedness was relevant) were considered statistically significant. This preliminary report contains results regarding immunogenicity and safety outcomes (captured on days 0 to 56). Descriptive and inferential statistics were performed using SAS 9·2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and NCSS 2021 (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah, USA).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

We enrolled 875 participants across the five study groups, of whom 868 participants were retained through the day 180, accounting for 99.2%. Mean age was 35.1 ± 12.5 (SD) years, and there were almost twice as many women (64.6%) than men (35.4%) enrolled, but demographic characteristics of participants were similar across the five study Groups (Table 1).

Humoral immune response

Neutralization antibody titers against Wuhan strain

Baseline humoral responses to the ancestral (Wuhan) strain, 6 ± 1 months after priming with two immunizations of either Covaxin and Covishield, were similar when measured either in terms of neutralization titers or ELISA IgG binding antibody titers (Supplementary Table 2). GMTs (PRNT50) at Day 0 were 289·6 and 388·7 in the two Covaxin-primed Groups (Groups 1 and 2), and 372·2, 320·9, and 451·6 in the three Covishield-primed groups (Groups 3–5). By Day 56, the GMT increased to 564·1 (95% CI: 479.1, 664.1) in the Covaxin group boosted with intranasal BBV154 and 578.1 (436.9, 764.9) after a homologous Covaxin booster (Table 2). In Groups 3–5, primed with Covishield, the GMT after intranasal BBV154 was 655.5 (533.2, 805.7), similar to the 625.4 (474.7, 824.0) in the heterologous Covaxin booster group and the 650.1 (519.7, 813.1) in the heterologous Covishield group. For mean log10 (titer) at both Day 0 and Day 56, there were no significant differences among the groups by ANOVA (p = 0.60 for Day 0 data, p = 0.79 for Day 56 data).

Moreover, the ratios of Day 56 PRNT GMT after intranasal BBV154 boost to GMT after Covaxin or Covishield boost, with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were 0.98 (0.72, 1.32) for Group 1 compared to Group 2, 1.05 (0.74, 1.49) for Group 3 compared to Group 4, and 1.01 (0.72, 1.41) for Group 3 compared to Group 5. Thus, with regard to Day 56 PRNT, the intranasal BBV154 boost was non-inferior to both the Covaxin boost and Covishield boost. Further, since the upper limit of the 95% CI was <1.50 in all cases, intranasal BBV154 boost and Covaxin boost, as well as intranasal BBV154 boost and Covishield boost, were statistically equivalent. At both Day 0 and Day 56, there were no significant differences among the groups by analysis of variance (ANOVA) on log10 (titer)(p = 0.60 for Day 0 data, p = 0.79 for Day 56 data (Table 2).

Further, to evaluate the impact of pre-existing antibodies, the same PRNT50 data was analyzed for all subjects using three mutually exclusive categories (PRNT50 at day 0, ≤10; ≥10 and ≤100, and >100), to classify sites based on likely Omicron infection status prior to vaccination. The results are given in Table 2. Statistical analysis (Mann–Whitney U-test, paired) revealed that PRNT50 titers were significantly increased from day 0 to 56 in all five Groups in the first two categories [(i) <10, (ii) ≥10 and ≤100)]; Whereas in the third category (>100 titer at baseline), where the level of infection is high at baseline, showed statistically significant decrease in titers from day 0 to 56 in all Groups, except in Group 3.

Neutralization antibody titers against Omicron lineages

In addition to PRNT50 titers against the Wuhan strain, PRNT50 titers at Day 56 were also generated against Omicron lineages BA.1, BA.2, BA.2.1.2, and BA.5 for randomly selected, small numbers of samples. Group-wise PRNT50 GMTs at Day 56 against each Omicron lineage are shown in Supplementary Table 3. For each lineage, differences among the five Groups in mean log10 (titer) at Day 56 were not statistically significant by ANOVA (p = 0.98 for BA.1, 0.72 for BA.2, 0.97 for BA.2.12, and 0.50 for BA.5). For the five Groups combined, the Day 56 GMT was much higher for BA.1 (1193.4) than for BA.2 (137.2), BA.2.12 (91.2), and BA.5 (132.1). GMT was significantly higher for BA.1 than for Wuhan (p < 0.0001). For the other Omicron lineages, the Day 56 GMT was lower than for Wuhan (p < 0.0001 for BA.2, p < 0.0001 for BA.2.12, and p = 0.05 for BA.5). Among the Omicron lineages, GMT was significantly higher at Day 56 for BA.1 than for BA.2, BA.2.12, and BA.5 (p < 0.0001 for each comparison). None of the pairwise differences among the other Omicron lineages were statistically significant.

Serum antibody (IgG/IgA) binding titers

GMTs of binding serum antibody anti-spike IgG, RBD-specific IgG and N-protein IgG (ELISA) at Day 0 were not significantly different in Groups 1 to 5 by ANOVA on log10 (titer) (p = 0.72, 0.83, and 0.55, respectively (Supplementary Table 4). In addition, there were no significant differences between Groups primed with Covaxin or Covishield by paired t-test on log10 (titer) (p = 0.68, 0.79, and 0.88, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). Over the entire study population, GMTs against spike protein and RBD showed a modest increase at Day 28 and GMT against N-protein showed a modest decrease. However, there were marked increases at Day 56 relative to Day 0 that were statistically significant for all three (p < 0.0001 for anti-spike and RBD, p = 0.0003 for N-protein by paired t-test on log10 (titer). GMT ratios (Day 56 to Day 0) ranged from 2.36 to 3.17 for Groups 1 to 5 for spike-specific IgG, 1.92 to 2.71 for RBD-specific IgG, and 1.09 to 1.41 for N-protein (Supplementary Table 4). Differences among Groups were not significant by ANOVA on log10 (titer) for spike-specific IgG (p = 0.56), RBD-specific IgG (p = 0.37), or N-protein (p = 0.64).

Mucosal immune response

GMTs of binding serum antibody anti-spike IgA titers GMTs (ELISA) at Day 0, Day 28, and Day 56 were not significantly different in Groups 1–5 by ANOVA on log10 (titer) (p = 0.71, 0.43, and 0.86, respectively) (Table 3). GMTs for Covaxin-primed participants and Covishield-primed participants were also not significantly different (p = 0.60, 0.13, and 0.50, respectively. Day 56 vs Day 0 serum anti-spike IgA titers GMT ratios were 2.68, 2.75, 2.61, 2.31, and 1.93 for groups 1–5, respectively (Table 3). These GMT ratios were not significantly different by ANOVA on log10 (titer) (p = 0.55).

Binding secretory (salivary) antibody anti-spike IgA (sIgA) titers were measured at Day 0 and Day 28, in a subset (n = 98) of study participants (Table 3). Differences among groups 1–5 in GMT at Day 0 were not statistically significant by ANOVA on log10 (titer) (p = 0.97). GMT at Day 28 ranged from 7.3 (Group 5) to 25.0 (Group 4) and was highest in the Covaxin-boosted groups (2 and 4); in this relatively small sample, however, the differences among groups were not significant by ANOVA (p = 0.40) (Table 3).

A smaller subset of saliva samples (n = 56) were analyzed for total saliva spike-specific IgA titers (Table 3). GMT at Day 0 varied from 14.3 (Group 1) to 53.8 (Group 4), but in this small sample the differences among groups were not statistically significant by ANOVA on log10 (titer) (p = 0.13). On Day 28, GMT varied from 20.2 (Group 2) to 41.5 (Group 4); the differences among groups were not significant (p = 0.89) (Table 3).

Cell-mediated immune response

Spike-specific (ancestral, n = 74 & Omicron, n = 82) IFNγ secreting T cells were measured at Days 0, 28, and 56. At baseline (Day 0), mean (95% CI) spike-specific (ancestral) IFNγ secreting T cells per million PBMCs were similar, and not significantly different by Mann–Whitney test (p = 0.26) in Covaxin or Covishield primed subjects (Supplementary Fig. 1). Further, the mean (95% CI) of spike-specific (ancestral) IFNγ secreting T cells at Day 0 were 68.8 (29.4, 108.2), 59.1 (28.0, 90.2), 114.9 (71.0, 158.9), 64.4 (17.5, 111.3), and 31.8 (0.8, 62.8) in Groups 1 to 5, respectively and the differences by the group were not significant by Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s correction for multiple comparison, but significant between Group 3 and Group 5 (p = 0.015) suggestive of high baseline T cell responses in Group 3 compared to Group 5. The mean (95% CI) of IFNγ secreting T cells increased on Day 56 in all groups to 160.4 (80.7, 240.1), 100.8 (53.3, 148.4), 155.1 (68.0, 242.3), 186.2 (70.7, 301.7), and 108.4 (60.6,156.2) in Groups 1 to 5, respectively. The increase of IFNγ secreting T cells from Day 0 to 56 was significant in Group 5 (p < 0.05), by Friedman test with Dunn’s correction for multiple comparison, but not in all other groups. IFNγ T cell responses were also observed against the Omicron variant, when PBMCs were stimulated with an Omicron-specific spike protein. Omicron-specific IFNγ T cell responses were non-significant across all groups, both at Day 0 & 56, by Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s correction for multiple comparison. However, the increase of IFNγ T cell responses from day 0 to 56 is significant in Group 5 (p < 0.001), but non-significant across all groups. Further, to understand the pre-existing immunity due to natural infection, MNS-specific IFNγ secreting T cells were also measured against ancestral and Omicron-specific MNS peptide pools across all groups. Overall baseline MNS-specific IFNγ secreting T cell responses were significantly higher in Group 3, compared to Group 1 & 5 (ancestral) and Group 5 (Omicron). But at Day 56, the differences were non-significant across all Groups. Statistically significant increases in MNS-specific IFNγ T cell response were observed at Day 56 over baseline (Day 0) only in Group 5 (homologous Covishield booster recipients), for both ancestral and Omicron-specific peptide pools (Friedman test; Dunn’s-adjusted p = 0.011 and 0.003, respectively) (Fig. 2 and Supplementay Data 1).

Scatter plots representing T and B cell responses against Ancestral and Omicron strains analysed by ELISPOT assay. SARS-CoV-2-specific IFNγ secreting T cells were measured upon stimulation of PBMCs with a ancestral Spike, b Omicron Spike, c Ancestral MNS, and d Omicron MNS; Similarly, IgG/IgA-secreting plasmablasts were measured upon stimulation of PBMCs with [(e, g)] ancestral whole-virion inactivated antigen and [(f, h)] Omicron Spike (S1) protein. Statistical analysis was performed in Graph-Pad Prism software. ANOVA (Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons) was performed to compare the CMI responses at different time points (day 0, 28, 56) within each group Further, all five vaccine groups were compared at individual time points by ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons). There were no significant differences between time points within each group, as well as among the groups, unless otherwise indicated with asterisk/son dotted line (“---” Kruskal–Wallis test) and solid line (“−” Friedman test). SFU indicates spot-forming units. “n” represents the number of samples analysed per group. Each dot represent single data point; Horizontal line represent mean with bars for 95% CI (confidence intervals).

SARS-CoV-2 recall responses were demonstrated by the evaluation of AIM+ Omicron-specific CD4+ or CD8+ T cell memory phenotype distributions in 70 individuals at Days 0, 28, and 56. Persistence of AIM+ Omicron-specific CD4+ T/ CD8+ T cell recall responses were comparable at baseline in Covaxin-primed and Covishield-primed individuals (p = 0.80) by Mann–Whitney U-test (Supplementary Fig. 2) and it is observed to be same across all the five Groups at baseline (Kruskal–Wallis test; Dunn’s correction for multiple comparison). However, there was a non-significant increase in the AIM+ CD4+ T cell phenotype population at Day 56 in all groups except in Group 2, where the increase was observed at Day 28. In contrast, a non-significant decrease of spike (Omicron) specific CD8+ T cell phenotype was observed in all Groups on Day 56, compared to Day 28 or 0; whereas in Group 3, the decrease from Day 0 to Day 56 is significant (Dunn’s-adjusted p = 0.04) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The AIM+ Omicron-specific CD4+ T cell population was more pronounced towards TCM (CCR7+CD45RA−) and TEM (CCR7−CD45RA−) phenotypes compared with the CD4+ CCR7− CD45RA+ (TEMRA) phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 3) in all Groups; with a significant increase of TCM phenotype in BBV154-boosted subjects in Covishield primed subjects. In contrast, the AIM+ Omicron-specific CD8+ T cell population predominantly expressed the TEMRA phenotype at Day 0 and Day 28. Interestingly, BBV154 boosted subjects (Covaxin or Covishield primed) showed a significant increase in TCM phenotype distribution. Moreover, the frequency of CD8+ TEM phenotype distribution significantly increased from Day 0 or 28 to day 56 across all groups. It is noteworthy to mention again that T cell memory response was found to be similar across all groups at baseline.

We also detected B cells that could be developed into SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG/IgA-secreting plasmablasts in PBMCs of a subset of vaccinated individuals (n = 83) at Days 0, 28 and 56 (Fig. 2). At Day 0, IgG-secreting plasmablasts against ancestral or Omicron significantly high in Covishield Group compared to Covaxin Group (Supplementary Fig. 4). At individual Group analysis of before and after administration of booster dose, we found that IgG secreting cells increased significantly in Group 1 & 2 against the ancestral strain by Day 56, whereas non-significant increase in other Groups. Against the Omicron variant, these levels were almost comparable across all time points and across all Groups, except in Group 2, where there is a significant increase on Day 28, compared to day 0 (p = 0.004). Interestingly, IgA-secreting plasmablasts were increased significantly on Day 28/56 in Covaxin-boosted subjects (Group 1 & 2) against both ancestral and Omicron variants and did not occur in any other Groups against either Ancestral or Omicron antigen. Notably, IgA-producing plasmablasts were higher at baseline/Day 28 in Covishield group 5 and further reduced on Day 56. Homologous Covaxin-boosted subjects also showed significantly higher IgG producing plasmablats, whereas BBV154 boosted in Covishield primed subjects showed non-significant increase in IgA-producing plasmablasts on day 28 against both ancestral and omicron (Fig. 2).

We also measured Ancestral or Omicron -specific memory B-cell (MBC) responses by ELISpot in both Covaxin-primed and Covishield-primed groups against ancestral or Omicron and the IgG secreting MBC responses are significant in Covishield Group, but not IgA-secreting MBC responses (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Safety

No deaths, hospitalizations, or serious adverse events had been recorded to date, nor any symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections through telephonic follow-up or site visit to the site investigators up to the cut-off on Day 180. After the booster doses, one or more solicited local adverse reactions were reported by 3/250 (1.2%), 10/125 (8.0%), 4/250 (1.6%), 9/125 (7.2%), and 12/125 (9.6%) of participants in Groups 1 to 5, respectively, and by 38/837 (4.3%) of the total study population (Table 4). The differences in percentages of participants with a local adverse event among the five Groups were statistically significant by χ2 (p < 0.0001); Group 5 had a significantly higher percentage than Groups 1 and 3 by pairwise multiple comparison score tests. Solicited systemic adverse reactions were reported by 13/250 (5.2%), 9/125 (7·2%), 15/250 (6·0%), 8/125 (6.4%), and 14/125 (11.2%) of participants in groups 1 to 5, respectively (Table 4); differences among Groups were not significant (p = 0.27 by χ2 test). The most frequently reported solicited adverse event were injection site pain and fever (Table 4). Similarly, there were few unsolicited adverse events (Supplementary Table 5), and the percentages of participants in the five Groups reporting one or more unsolicited adverse event were not significantly different (p = 0.90). Adverse events were generally mild and resolved within 24 h of onset.

Discussion

We report findings from a phase 3 heterologous booster trial, a large cohort-based and geographically diverse study, involving an intranasal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (BBV154) as a heterologous booster dose administered to Covaxin or Covishield-primed subjects, as well as homologous and heterologous boosting of Covaxin and Covishield-primed subjects. Vaccine induced humoral responses to the ancestral (Wuhan) strain were similar across all Groups at a macro level of data analysis. However, vaccine induced immune response is dependent on the status of infection of the subjects before boosting and the baselines titers21,. These baseline titers varied from the clinical site, which is, of course, depending on the seroprevalence of that geographical region22 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Although, the overall GMTs at Day 56 seemed to have similar across all Groups, further, the dissection of data to observe the vaccine induced immune response based on baseline titers or seroprevalence at Day 0 were discussed in the subsequent paragraph.

The booster dose of the intranasal BBV154 to Covaxin-primed subjects elicited a higher Day 56 geometric mean immune response in participants, who had less baseline titers ((i) <10; (ii) between ≥10 and ≤100). A similar trend was observed in Covaxin-boosted subjects, to Covishield-primed subjects. However, participants, who had high baseline titers (>100), did not show any difference on day 56, compared to day 0, as the antibody levels might have been reached to plateau at the baseline itself. Thus, these findings demonstrate that booster impact across large cohorts is primarily governed by the infection status of the individual22. Statistical comparison of PRNT50 between day 0 and day 56, at all three categories, showed a significant increase of neutralization antibodies from day 0 to 56, in the first two cut-offs; whereas, in the third cut-off category, a significant decrease was noticed, indicating that the level of vaccine-induced response would depend on the baseline titers (Table 2). Similarly, vaccine induced spike and RBD specific binding IgG titers are high in BBV154 boosted subjects as well as in Covaxin boosted in Covishield-primed participants, compared to homologous booster recipients (Groups 2 & 5).

Both Covaxin and Covishield showed similar T cell responses at baseline against both ancestral and Omicron, with persistent T cell memory, 6 ± 1 months post 2 doses, and this trend continued even after booster dose (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2), except an increase in CD8+ effector or central memory phenotype on day 56, across all Groups; notably, higher level of statistical significance in BBV154 boosted subjects (Covaxin-primed), was observed indicating the positive impact of BBV154 as booster dose. Homologous Covaxin-primed subjects and Covaxin-primed followed by BBV154 boosted subjects also showed a significant increase in vaccine-induced plasma B cell response by secreting significant levels of IgG-secreting plasmablasts, compared to other Groups. Especially, significant IgA-producing plasmblasts in Covaxin-primed and BBV154 boosted subjects corroborate with a pronounced increase of salivary IgA responses. However, Covishield-primed followed by BBV154 boosted subjects, did not show significant vaccine-induced response, perhaps, this could be due to high baseline titers, corroborated with the presence of high MNS-specific IFNγ responses (Fig. 2) and significant IgG/IgA-secreting Plasmablasts in Covishield Group against Ancestral and Omicron (Supplementary Fig. 4)

In addition, the cross-reactivity of Covishield immune sera against BBV154 was analysed using serum samples (n = 69) from Group 5, 28 days post booster dose (these subjects were primed with two doses of Covishield and boosted with a third dose of Covishield). Covishield immune sera displayed little cross-reactivity against the BBV154 vector (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting that BBV154 booster in Covishield recipients will not have pre-existing immunity issue23.

BBV154 was well tolerated, with significantly lower reactogenicity events and no serious adverse events. After a booster dose of BBV154, the most common solicited adverse event was headache. All adverse events were mild and resolved within 24 h of onset. No significant safety differences were observed between the intranasal, BBV154, and intramuscular, Covaxin and Covishield groups. In both of the heterologous intranasal groups (Groups 1 and 3), the combined incidence rates of local and systemic adverse events are strikingly better than the rates for other homologous and heterologous injectable licensed SARS-CoV-2 vaccine platform7,18,24,25,26. However, other vaccine studies enrolled different populations and employed varying approaches to measure adverse events.

Intramuscularly (IM) injected Covid-19 vaccines predominantly elicit circulating spike-specific B and T cells and prevent severe disease development with limited mucosal protection27,28. This minimal protection, especially in the upper airways where viral transmission and replication occur, may lead to the risk of transmission of the virus from vaccinated individuals, thus leading to continuous emerging variants of concern and breakthrough infections. Therefore, effective booster vaccination strategies should not be restricted to a single route of administration of vaccine. In addition to injectable vaccines, mucosal booster vaccination is needed to reinforce the robust sterilizing immunity in the respiratory tract against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Omicron sub-lineages8. By producing both mucosal (protection at the site of infection) and systemic immunity (antibody formation), an intranasal (IN) vaccine may offer the potential to be efficacious against disease and infection, which may corroborate reduced transmission.

Many countries have initiated the administration of homologous or heterologous booster doses to vaccinated populations that have completed primary vaccination series. The objective of a booster dose is to protect against severe disease, hospitalization, and death due to breakthrough infections caused by SARS-CoV-2 variants. Several clinical studies have demonstrated that heterologous prime-boost vaccination with Covid-19 vaccines from multiple platforms could be more effective than homologous regimen9,29,30. Further, a heterologous route of vaccine delivery may provide several advantages over the conventional intramuscular route of vaccination against respiratory diseases. Intramuscular priming to elicit a long-lived systemic IgG response followed by an intranasal booster could result in a qualitatively and quantitatively better immune response, including induction of IgA responses and tissue-resident memory cells in the upper and lower respiratory tracts8. Moreover, secretory IgA responses are considered to be valuable for the protection against SARS-CoV-2 and for vaccine efficacy31. Accordingly, heterologous booster immunization with an aerosolized Ad5-nCoV in CoronaVac-primed adults was found to be safe and highly immunogenic, and elicited significantly higher concentrations of neutralizing antibodies than a homologous third dose of CoronaVac9. Similarly, intranasal adenovirus immunization in intramuscular mRNA-primed mice showed high levels of mucosal neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineage BA.1.128.

Intranasal vaccines offer several advantages over parenteral immunization. For example, ease of administration, non-invasiveness, high-patient compliance and suitability for mass vaccination. Further, robust balanced immune response along with mucosal immune responses induced by the intransal vaccines made them effective vaccine approach to counter the Covid-19 pandemic32.

This was the India’s largest homologous and heterologous booster study with geographical diversity study conducted at a time of rapid increase of Covid-19 cases (between February to June 2022), due to the emergence of Omicron, during third wave. Especially, the BA.1 variant was more prevalent in India between December 2021 and January 2022, just before the clinical trial was initiated21. Therefore, neutralization antibody titers against BA.1 were significantly high compared to PRNT50 titers against Wuhan, unlike other reported articles, where neutralization antibody titers were less against Omicron lineages compared to Wuhan, predicted to be due to neutralization escape22,33,34,35,36,37. Whereas the less neutralization antibody titers against other Omicron lineages (BA.2, BA2.1.2, and BA.5), compared to Wuhan, are very much inline with reported literature22,33,34,35,36,37.

Hence, based on seroprevalence data obtained from the Ministry of Health, Government of India, clinical trial sites were categorized as high, moderate, and low (Supplementary Fig. 5). Accordingly, baseline (day 0) neutralization titers were different across various sites. Two months after administering a booster, titers increased approximately twofold globally, considering all sites. For brevity, when PRNT50 titers of sites with high and low infection rates were analysed, high GMT ratios were observed with 55% seroconversion at sites with low infection rates; conversely, sites with high infection rates showed less GMT ratio of PRNT50 titers with fourfold seroconversion is only 3%, indicating the impact of seroprevalence on booster vaccination (Supplementary Table 6). Similar results were found when anti-N-antibody titers analysed at high and low infection sites against ancestral strains, indicating the varied occurrence of natural infection across the geographical sites. But, the Omicron-specific N-antibody titers have not shown a significant difference. Perhaps, due to less sample size or sample testing against B.1.1.529, as opposed to BA.1, which was more prevalent at the time of clinical trial initiation (Supplementary Table 6). Thus, the geographical heterogeneity due to seroprevalence played a key role in elucidating the booster effect. In contrast, we previously conducted a phase 2 trial where participants primed with Covaxin (28 days post first dose) and boosted with Covaxin (third dose), 6 months later displayed a ~30-fold rise in neutralizing antibodies38, during which prevailing infections were low. Similarly, in phase 2 heterologous clinical study (CTRI/2021/08/035993) conducted earlier, during August and September 2021, where the infection rate was also low, both homologous (Covaxin vs Covaxin; BBV154 vs BBV154) and heterologous combination with Covaxin (BBV154 followed by Covaxin; Covaxin followed by BBV154) induced 14 to 24-fold higher neutralization antibody titers compared with baseline (Supplementary Table 7). However, the same homologous booster group in this heterologous phase 3 trial (Group 2—Covaxin: Covaxin: Covaxin), demonstrated only a 2.5-fold increase from baseline titers 319.6 (GMTs, 95% CI 242.1, 421.7), 6 months post 2-doses. This difference of variation in GMT ratio reflects the time at which the clinical trial started and the level of hybrid immunity occurred post natural boosting through natural exposure to circulating variants. Thus, these prior infections seem to have impacted vaccine-induced mucosal responses, as the magnitude of saliva IgA response in any of the homologous or heterologous groups was not significant, except in BBV154 recipients, with a slightly higher mucosal response. Possibly, these results would have implications on the ability of BBV154 to block infection and forward transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the community, depending on the severity of the infection. However, in this trial, no Covid-19 cases were reported from any Group, no illness visits were scheduled, and routine SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing was not conducted. The results reported here do not permit efficacy assessments and there is a need to evaluate the effectiveness and impact on transmission in further studies. Due to the ubiquitous nature of SARS-CoV-2 making it difficult to access a naïve population, these would probably have to be done in a controlled human infection model (CHIM).

Evaluation of safety outcomes and vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) will require post-marketing safety surveillance in a larger population, and follow-up study results are required to establish immunogenicity in children and the elderly.

In conclusion, booster doses with either BBV154, Covaxin or Covishield showed similar immunological responses, and also all vaccines showed neutralization against VOCs. Most importantly, this data demonstrates that geographical diversity and seroprevalence played a dominant role in determining the booster dose impact. However, BBV154 boosted subjects showed significant enhancement of T cell memory and IgG/IgA-secreting plasma B cells. Thus, BBV154 as a booster has the advantage over the other vaccines in terms of inducing strong B & T cell memory response, ease of administration, and excellent safety profile.

Data availability

BBV154 is a chimpanzee adenoviral-vectored SARS-CoV-2 intranasal vaccine encoding a prefusion-stabilized spike protein with two proline substitutions in the S2 subunit (GenBank: QJQ84760.1). The data generated in this study are included in this article and in Supplementary Tables 2–7. The source data for Fig. 2 is in Supplementary Data 1. Information about the grading scale on adverse events is included in Supplementary Data 2. The study protocol, statistical analysis plan, and individual participant (de-identified) data, along with an informed consent form, will be made available upon a direct request to the corresponding author with an appropriate research proposal. After consideration and the approval of such a proposal, data will be shared through a secure online platform.

References

Ayoub, H. H. et al. Estimates of global SARS-CoV-2 infection exposure, infection morbidity, and infection mortality rates in 2020. Glob. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloepi.2021.100068 (2021).

Zheng, C. et al. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 114, 252–260 (2022).

Ong, S. W. X., Chia, T. & Young, B. E. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and vaccine escape, from Alpha to Omicron and beyond. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 16, 499–502 (2022).

Madhi, S. A. et al. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1885–1898 (2021).

Tuekprakhon, A. et al. Antibody escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 from vaccine and BA.1 serum. Cell 185, 2422–2433 e2413 (2022).

Zuo, F. et al. Heterologous immunization with inactivated vaccine followed by mRNA-booster elicits strong immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Nat. Commun. 13, 2670 (2022).

Costa Clemens, S. A. et al. Heterologous versus homologous COVID-19 booster vaccination in previous recipients of two doses of CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccine in Brazil (RHH-001): a phase 4, non-inferiority, single blind, randomised study. Lancet 399, 521–529 (2022).

Lund, F. E. & Randall, T. D. Scent of a vaccine. Science 373, 397–399 (2021).

Li, J. X. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of heterologous boost immunisation with an orally administered aerosolised Ad5-nCoV after two-dose priming with an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in Chinese adults: a randomised, open-label, single-centre trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 10, 739–748 (2022).

Hassan, A. O. et al. A single-dose intranasal ChAd vaccine protects upper and lower respiratory tracts against SARS-CoV-2. Cell 183, 169–184 e113 (2020).

Bricker, T. L. et al. A single intranasal or intramuscular immunization with chimpanzee adenovirus-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine protects against pneumonia in hamsters. Cell Rep. 36, 109400 (2021).

Hassan, A. O. et al. A single intranasal dose of chimpanzee adenovirus-vectored vaccine protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection in rhesus macaques. Cell Rep. Med. 2, 100230 (2021).

Singh, C. et al. Phase III Pivotal comparative clinical trial of intranasal (iNCOVACC) and intramuscular COVID 19 vaccine (Covaxin®). npj Vaccines 8, 125 (2023).

Ganneru, B. et al. Th1 skewed immune response of whole virion inactivated SARS CoV 2 vaccine and its safety evaluation. iScience 24, 102298 (2021).

Yadav, P. D. et al. Full-genome sequences of the first two SARS-CoV-2 viruses from India. Indian J. Med. Res. 151, 200–209 (2020).

Sardar, R., Satish, D., Birla, S. & Gupta, D. Integrative analyses of SARS-CoV-2 genomes from different geographical locations reveal unique features potentially consequential to host-virus interaction, pathogenesis and clues for novel therapies. Heliyon 6, e04658 (2020).

Watanabe, Y. et al. Native-like SARS-CoV-2 Spike glycoprotein expressed by ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/AZD1222 vaccine. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 594–602 (2021).

Ella, R. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBV152: interim results from a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, phase 2 trial, and 3-month follow-up of a double-blind, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 950–961 (2021).

Ella, R. et al. Efficacy, safety, and lot-to-lot immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (BBV152): interim results of a randomised, double-blind, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 398, 2173–2184 (2021).

Agresti, A., Bini, M., Bertaccini, B. & Ryu, E. Simultaneous confidence intervals for comparing binomial parameters. Biometrics 64, 1270–1275 (2008).

Vadrevu, K. M. et al. Persistence of immunity and impact of third dose of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine against emerging variants. Sci. Rep. 12, 12038 (2022).

Hornsby, H. et al. Omicron infection following vaccination enhances a broad spectrum of immune responses dependent on infection history. Nat. Commun. 14, 5065 (2023).

Croyle, M. A. et al. Nasal delivery of an adenovirus-based vaccine bypasses pre-existing immunity to the vaccine carrier and improves the immune response in mice. PLoS ONE 3, e3548 (2008).

Mulligan, M. J. et al. Phase I/II study of COVID-19 RNA vaccine BNT162b1 in adults. Nature 586, 589–593 (2020).

Folegatti, P. M. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 396, 467–478 (2020).

Xia, S. et al. Effect of an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 on safety and immunogenicity outcomes: interim analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA 324, 951–960 (2020).

Azzi, L. et al. Mucosal immune response in BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine recipients. EBioMedicine 75, 103788 (2022).

Tang, J. et al. Respiratory mucosal immunity against SARS-CoV-2 after mRNA vaccination. Sci. Immunol. 7, eadd4853 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of heterologous versus homologous prime-boost schedules with an adenoviral vectored and mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Com-COV): a single-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 398, 856–869 (2021).

Sapkota, B. et al. Heterologous prime-boost strategies for COVID-19 vaccines. J. Travel Med. 29, taab191 (2022).

Wang, Zijun et al. Enhanced SARS-CoV-2 neutralization by dimeric IgA. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabf1555 (2021).

Mendonca, S. A., Lorincz, R., Boucher, P. & Curiel, D. T. Adenoviral vector vaccine platforms in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. NPJ Vaccines 6, 97 (2021).

Sarkar, A. et al. The relative prevalence of the Omicron variant within SARS-CoV-2 infected cohorts in different countries: a systematic review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2212568 (2023).

Cele, S. et al. Omicron extensively but incompletely escapes Pfizer BNT162b2 neutralization. Nature 602, 654–656 (2022).

Schmidt, F. et al. Plasma neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 599–601 (2022). Feb 10.

Bowen, J. E. et al. Omicron spike function and neutralizing activity elicited by a comprehensive panel of vaccines. Science 377, 890–894 (2022).

Bellusci, L. et al. Antibody affinity and cross-variant neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1, BA.2 and BA.3 following third mRNA vaccination. Nat. Commun. 13, 4617 (2022).

Hachmann, N. P. et al. Neutralization escape by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 86–88 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank the principal and co-principal investigators, study coordinators, and healthcare workers involved in this study. We express our gratitude to Dr. Sivasankar Baalasubramaniam from ImmunitasBio Private Limited, Bangalore, and Dr. Nimesh Gupta, National Institute of Immunology, New Delhi, who assisted with cell-mediated response analyses. We appreciate the guidance from Dr. William Blackwelder on sample size estimation and statistical analysis planning. Drs. Yuvraj Dnyanoba Jogdand, Amarnath Reddy Kowkuntla, Vinay Aileni, and Ms. Sandya Rani, Aparna Bathula, Akhila Kunta of Bharat Biotech participated in protocol design and clinical trial monitoring. We thank Drs. Raju Dugyala, Usha Praturi, Soumya Neelagiri, Krishna Shilpa Palem, Sony Kadiam, Ishani Lahiri, Niharika Pentakota, and Gayathri Kudupudi for performing serum or saliva binding antibody assays, PBMCs isolation for cell-mediated assays and data compilation. Keith Veitch (Keithveitch Communications, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) provided editorial guidance for the manuscript. This vaccine candidate could not have been developed without the efforts of Bharat Biotech’s Manufacturing, Quality Control teams. All authors would like to express their gratitude to all frontline healthcare workers during this pandemic. This work was supported and funded by the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC), Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. BT/CS0019/CS/01/20 Dt.12.04.2021 and Bharat Biotech International Limited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors met the International Committee for Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship. K.M.V. and B.G. primarily contributed to the data interpretation and manuscript preparation, while R.E. and S.P. reviewed the manuscript. B.G. lead the immunogenicity experiments. K.S. generated neutralization antibody titers by PRNT assay. SRe was the study coordinator for the clinical trial and assisted with designing the protocol and generating the study report. K.M.V. was responsible for overall supervision of the project and review of the final paper. All principal investigators (A.V.R., A.S.B., C.S.G., J.S.K, A.P.S., C.S., A.K.P., S.K.K., and S.K.R.) were involved in conducting the clinical trial.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest. K.M.V., B.G., S.R.C., K.S., R.E., and S.P. are employees of Bharat Biotech, with no stock options or incentives. A.V.R., A.R.B., C.S.G., J.S.K., A.P.S., C.S., A.K.P., S.K.K., and S.K.R. were principal investigators representing the study sites. Authors from Bharat Biotech and Principal Investigators had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The study sponsor had no role in biostatistical analysis and in writing the report, which was done by the Contract Research Organization (CRO). CRO is responsible for unblinding. K.M.V. and S.R.C. from Bharat Biotech, and the contract research organization had full access to the data in the study, after unblinding.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Karina Pasquevich, Delphine Sterlin and Didac Macia for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [Peer review reports are available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akula, V.R., Bhate, A.S., Gillurkar, C.S. et al. Effect of heterologous intranasal iNCOVACC® vaccination as a booster to two-dose intramuscular Covid-19 vaccination series: a randomized phase 3 clinical trial. Commun Med 5, 133 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00818-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00818-6

This article is cited by

-

Nasal drop booster shows strong immune response against COVID

Nature India (2025)