Abstract

Background

Long-COVID immunopathogenesis involves diverse factors. We longitudinally characterize hospitalized COVID-19 patients, examining the role of SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and inflammation in immune dysregulation.

Methods

Hospitalized patients are evaluated during acute infection (T0), 3 months post-symptom onset (T1), and 3 years if symptoms persisted (T2). Immune profile includes characterization of SARS-CoV-2-specific/non-specific T/B cells (flow cytometry) and antibodies (ELISA, neutralization, ADCC). RNAemia and cytokines are quantified (RT-PCR, cytometric beads array) and correlated. Statistics: non-parametric cross-sectional, longitudinal and correlation analyses.

Results

Here we show 48 hospitalized individuals during acute COVID-19, 38 exhibit early persistent symptoms (EPS+) 3 months post-symptoms onset, 10 do not (EPS−). Groups are comparable for age, sex, co-morbidities. The EPS+ shows fatigue, dyspnoea, anosmia/dysgeusia, diarrhea, chronic pain, mnestic disorders. Over time, they show a reduction of neutralization ability and total SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells, with increased total CD4 TEMRA, and failure to increase RBD-specific B cells and IgA+ MBCs. EPS+ patients show higher levels of T0-IFN-γ + CD4 TEMRA, T1-IL-2 + CD4 TEM and T1-TNF-α + CD4 cTfh. In EPS+, baseline SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia positively correlates with CD4 TEMRA, follow-up SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia with ADCC. Among 38 EPS+ individuals at T1, 33 are evaluated 3 years after infection, 5 are lost at follow-up. 10/33 EPS+ show long-term symptoms (late persistent symptoms, EPS + LPS+), whereas 23/33 fully recover (EPS + LPS−). Antibodies, RNAemia, and cytokines show no differences between/within groups at any time point.

Conclusions

Early persistent symptoms are associated with multi-layered SARS-CoV-2-specific/non-SARS-CoV-2-specific immune dysregulation. The shift towards non-Ag-specific TEMRA and ADCC trigger in EPS+ may relate to SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia. Early immune dysregulation does not associate with long-term persistent symptoms. Further research on SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and early immune dysregulation is needed.

Plain language summary

After COVID-19 resolution, many individuals continue experiencing symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive issues, which limit their daily activities. The causes of persistent symptoms remain unclear, but poor immune control of infection is plausible. Our research examined two key elements in driving poor immune control, including the presence of virus in the blood and inflammation. For severely ill, hospitalized, unvaccinated individuals with long-lasting symptoms beyond three months after infection, our findings show a weak immune response against the virus that causes COVID-19. The presence of the virus in the blood may contribute to this issue. Understanding these mechanisms moves us closer to finding better treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than three years into the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and decisive progresses have been made to understand the immunopathogenic mechanisms underlying disease severity in order to obtain effective preventive, as well as therapeutic measures to control SARS-CoV-2 infection and acute disease1. However, a variable proportion of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 show symptoms that persist beyond the acute phase of disease (i.e. long-COVID). Even though there is still some debate on how the pathological continuum of symptoms after acute COVID-19 should be defined2, it appears to be characterized by a multitude of clinical manifestations, affecting multiple organs, with a variable impact on daily life. Symptoms may include fatigue, shortness of breath, anosmia/dysgeusia, diarrhea, chronic pain, and cognitive dysfunction3,4,5,6. Female sex or older age are among the risk factors6,7,8,9. Despite the long-COVID heterogeneity in terms of study population, timing, methods, and parameters under study, its incidence is estimated to be approximately 10-15% of infected individuals10,11, and even higher for hospitalized patients.

Soon after the beginning of the pandemic, immune dysregulation emerged as a hallmark of some recovered COVID-19 individuals. Unfortunately, the lack of detailed reports on persistent symptoms hampered the identification of underlying biological mechanisms. To date, in light of the current definitions, hypotheses have emerged so far and include viral persistence12, dysbiosis13,14, autoimmunity15, long-lasting tissue damage12,13,16,17,18,19,20, complement dysregulation21, thrombosis22, CNS cell activation23, and reactivation of latent viruses24. The heterogeneity of mechanisms may depend on the different types of clinical manifestation, the need for hospitalization, the time passed since recovery, or viro-immunological marker. For instance, if we consider the results by focusing on the need for hospitalization, different outcomes across studies emerge. In non-hospitalized subjects, individuals with persistent symptoms do not show differences in SARS-CoV-2-specific cellular immunity or exhibit high levels of functional memory cells25,26, whereas in hospitalized individuals those with persistent symptoms were featured by a lower SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral response27. In mixed cohorts, i.e. composed of hospitalized and non-hospitalized subjects, fewer CD8 T cells expressing the tissue homing β7 integrin, higher levels of IFN and activated immune cells were shown in those with persistent symptoms28,29.

Interestingly, early virus-host kinetics may be a crucial determinant of long-COVID development. Indeed, individuals with a delayed viral clearance, increased respiratory viral burden, or lower IgA secretory responses during the acute phase are more likely to develop long-COVID30,31,32,33. The SARS-CoV-2 persistence in various anatomical districts is now a well-recognized factor34, but how it is entwined with immune dysregulation in long-COVID development needs further assessments.

Therefore, we comprehensively immune profile longitudinal samples from a cohort of unvaccinated, acutely ill, hospitalized COVID-19 subjects and evaluate SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia as well as peripheral cytokines as possible pathogenetic mechanisms underlying immune dysregulation in long-COVID development. Results from this study show that individuals with persistent symptoms 3 months from symptoms’ onset have a multi-layered dysregulated SARS-CoV-2-specific and non-SARS-CoV-2-specific immune responses, with SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia possibly associated with humoral dysregulation.

Methods

Study population

Hospitalized patients with a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (positive RT-PCR nasopharyngeal swab) were consecutively enrolled at the Clinic of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, San Paolo Hospital, ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Milan, Italy, between March and October 2020 (i.e. T0). Disease severity during the acute phase of disease was defined by the highest level of respiratory support required during hospitalization (no oxygen therapy required, low or high-flow oxygen therapy, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) and orotracheal intubation (OTI). After the acute phase, patients were followed up at the Outpatient Clinic three months from symptoms onset (i.e. T1). T1 follow up visits were conducted in person and included: a comprehensive medical evaluation by an Infectious Disease Specialist, the administration of standardized questionnaires for symptoms’ assessment, and blood sample collection for routine tests and viro-immunological analyses. Questionnaires included the following symptoms: fever, fatigue, muscle/joint/bone pain, gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, gastric pain), dyspnea, chest pain, cough, attention/memory disorders. For this study, which focuses on inflammation and immune responses as biological markers, individuals presenting only psychological symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, mood disorders, or sleep disorders) were excluded. The two study groups were matched for age, sex and severity of disease during the acute phase to minimize bias in the interpretation of the analyses and potential confounding factors. Peripheral blood samples for plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) separation were collected at T0 and T1. Plasma samples were stored at −80 °C, while PBMC in liquid nitrogen, both preserved until processing. Finally, participants with persistent symptoms at T1, were further evaluated via telemedicine 3 years (i.e. T2) after the acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, using the same standardized questionnaires (Fig. 1).

In hospitalized unvaccinated COVID-19 individuals, clinical data, plasma and PBMCs samples were collected during the acute disease (i.e. T0). A median of 3 months from symptoms onset (i.e. T1), clinical data, plasma and PBMCs samples were collected and the cohort was stratified according to symptoms persistence in individuals who did not show early persistent symptoms (i.e. EPS−, n = 10), and individuals who showed early persistent symptoms (i.e. EPS+, n = 38). A median of 3 years from symptoms’ onset (i.e. T2), clinical data were retrieved from a total of 33 EPS+ individuals and the group was stratified according to symptoms persistence in EPS+ individuals showing late persistent symptoms a median of 3 years from symptoms onset (i.e. EPS + LPS+, n = 10), and EPS+ individuals who resolved symptoms (i.e. EPS+LPS−, n = 23). EPS early persistent symptoms, LPS late persistent symptoms. Created with Biorender.

Ethics

All relevant ethical regulations were followed and the study was approved by the following Institutional Ethics Committee: Comitato Etico ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo (2020/ST/049, 2020/ST/049_BIS, 11/03/2020), and the Ethics Committee of CHUM (19.381, approved on 28 February 2022); written informed consent was obtained from participants for data collection, follow-up visits, and blood sample collection. All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Symptoms evaluation

All patients underwent a comprehensive medical evaluation at each visit to assess the presence of persistent or newly onset symptoms. Standardized questionnaires were employed to assess clinical status and were compiled by patients with the assistance of an Infectious Diseases specialist. Symptoms and comorbidities were collected using a condensed version of the post-COVID-19 WHO Case Report Form (CRF), which includes a comprehensive list of conditions associated with long-COVID. Chronic fatigue was assessed using the Fatigue Numerical Rating Scale and the Fatigue Severity Scale. The Fatigue Numerical Rating Scale characterizes the severity of fatigue over the past 24 h on a 0–10 scale, while the Fatigue Severity Scale consists of nine statements, each scored from 0 to 7, assessing fatigue symptoms over the past week. Shortness of breath was investigated using the Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnea Scale, which lets patients self-assess severity on a scale from 1 to 5.

SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies

Total RBD-specific antibodies were determined by an in-house ELISA and expressed as area under the curve (AUC)35. Briefly, high-binding 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) were coated with 3 µg/ml of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 RBD (Creative Diagnostics) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After 1 h blocking with PBS-2% BSA at 37 °C, plasma was serially diluted in duplicates, and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The following biotinylated antibodies were used: goat anti-human kappa and lambda light chain for total antibodies (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.), rabbit monoclonal anti-human IgM and IgA (Abnova), mouse anti-human IgG1 (BD Biosiences) and IgG3 (Southern Biotech); followed by avidin-HRP (ThermoFischer Scientific) for 30 min at RT. The detection was carried out with 1 × 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine and quenched with 1 M H2SO4. A total of 7 pre-pandemic plasma controls were included. Additionally, the RBD-specific monoclonal antibody (Human Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD Monoclonal antibody, Creative Diagnostics) was included as positive control. Optical density (OD) was measured with Ensight (PerkinElmer) at 450 nm and 650 nm.

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) assay

Parental CEM.NKr CCR5+ cells were mixed at a 1:1 ratio with CEM.NKr-Spike cells, stained for viability (AquaVivid; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a cellular dye (cell proliferation dye eFluor670; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subsequently used as target cells36,37,38,39. Overnight-rested PBMCs were stained with another cellular marker (cell proliferation dye eFluor450; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and used as effector cells. Stained effector and target cells were mixed at a 10:1 ratio. Plasma from COVID-19+ individuals (1/500 dilution) was added to the appropriate wells. Plates were centrifuged for 1 min at 300 g, and incubated at 37 °C for 5 h before being fixed. Since CEM.NKr-Spike cells express GFP, ADCC activity was calculated as follow: [(% of GFP+ cells in Targets plus Effectors)−(% of GFP+ cells in Targets plus Effectors plus plasma)]/(% of GFP+ cells in Targets) × 100 by gating on transduced live target cells. A total of 7 pre-pandemic plasma controls were included. Samples were acquired with LSRII cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data analysis performed using FlowJo v10.5.3 (Tree Star).

Neutralization assay

293T cells were transfected with the lentiviral vector pNL4.3 R-E- Luc (NIH AIDS Reagent Program) and a plasmid encoding for D614G Spike glycoprotein. Two days post-transfection, cell supernatants were harvested. For neutralization assay, 293T-ACE2 target cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well (Perkin-Elmer) 24 h before infection. Pseudoviral particles were incubated with plasma dilutions (1/50; 1/250; 1/1250; 1/6250; 1/31250) for 1 h at 37 °C and added to the target cells followed by 48 h incubation at 37 °C. Cells were lysed with 30 µL of passive lysis buffer (Promega) followed by one freeze-thaw cycle. An LB942 TriStar luminometer (Berthold Technologies) was used to measure luciferase activity after the addition of 100 µL of luciferin buffer and 50 µL of 1mM d-luciferin potassium salt (Prolume). A total of 7 pre-pandemic plasma controls were included.

Immunophenotyping of B cells

In a subgroup of COVID-19 individuals, B cells were enriched from previously frozen PBMCs by immunomagnetic negative selection according to the manufacturer’s instructions (EasySep Human B Cell Enrichment Kit and EasySep magnet, STEMCELL) to retain non-B cells. Untouched B cells were eluted and washed in PBS-2% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-1mM EDTA. Overnight rested B cells were stained with Viobility Fixable Dye (Miltenyi Biotec) for 15 min at RT. An RBD-tetramer solution was prepared for the identification of RBD-specific B-cells by mixing 0.75uL of Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 RBD (HEK)-Biotin (Miltenyi Biotec) with 0.6uL of Streptavidin-PE (Miltenyi Biotec) and 1.5uL of Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 RBD (HEK)-Biotin (Miltenyi Biotec) with 1.2μL of Streptavidin-PE-Vio770 (Miltenyi Biotec) in a buffer containing PBS-0.5% BSA-2mM of EDTA for 15min at RT. Therefore, 5μL of RBD-Biotin-Streptavidin-PE and 10μL of RBD-Biotin-Streptavidin-PE-Vio770 were added to the Abs mix (Supplementary Table 1). Cells were stained for 20min at RT in the dark and acquired with the FACSymphony A5 (BD Biosciences) (CST 5-Blue 2-Red 3-Violet). A total of 7 individuals collected before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic were included as controls. Data were analyzed using FlowJo 10.7.2 (BD Biosciences). The gating strategy is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1.

T cell Immunophenotype and SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell response

In a subgroup of COVID-19 individuals, SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells were determined by means of two complementary flow cytometry methodologies, i.e. activation-induced marker assay (AIM) and intracellular cytokine staining (ICS), integrated within a unique panel. Briefly, cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed and 1.5 × 106 cells were plated in complete RPMI containing 10% human serum supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine. After 3 h resting, PBMCs were stimulated with a pool of 15-mer peptides (1 μg/mL) covering the immunodominant sequence domain of the Spike (S), the complete sequence of the Nucleocapsid (N), and the complete sequence of the Membrane (M) proteins (PepTivator SARS-CoV-2, Miltenyi Biotec). Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB) (1 µg/mL) was used as positive control, while unstimulated controls received equivalent volume of sterile H2O. All conditions were left for 20 h at 37 °C, with addition of 1x GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) for the last 4 h to allow intracellular cytokine detection. The staining was performed as follow: viability staining (15 min, RT) (Viobility Fixable Dye, Miltenyi Biotec), surface antigens staining (20 min, RT), fixation/permeabilization (Cytofix/Cytoperm, BD Biosciences), and intracellular cytokines staining (30 min, RT) (Supplementary Table 1). Unspecific activation in unstimulated controls was subtracted from stimulated samples to account for specific activation. Immunophenotype was assessed evaluating the frequency of cells in the unstimulated control expressing the surface markers. A total of 7 individuals collected before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic were included as controls. Samples were acquired using FACSymphony A5 (BD Biosciences) (CST 5-Blue 2-Red 3-Violet), and data were analyzed using FlowJo 10.7.2 (BD). The gating strategy is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Plasmatic SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR

Viral RNA was extracted from 140 µl of thawed plasma by using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN), and quantified by real-time PCR using the COVID 19 HT Screen (Clonit, Italy). The 2019-nCoV_N Positive Control plasmid (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.) was used for absolute quantification, a non-template condition was used as negative control, and the RPP30 quantification for RNA extraction quality assessment. The assay was run in duplicate on the Bio-Rad CFX96™ platform.

Cytometric bead array

Plasmatic cytokines (IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-17A, and TNF- α) and chemokine (GM-CSF) were quantified with the Human MACSPlex Cytokine 12 Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, thawed plasma samples were diluted 1:4 with assay diluent and incubated for 2 h with the MACSPlex Cytokine 12 Capture Beads, followed by 1 h incubation with the MACSPlex Cytokine 12 Detection reagent. Samples were resuspended in 0.3 ml of assay buffer, acquired on a FACSVerse™cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowLogic v8 (Inivai Technologies).

Statistics and reproducibility

Descriptive statistics on demographics for both groups, i.e. EPS− vs EPS+, are provided in Table 1. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, two-tailed, was used for longitudinal analyses to assess immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection during the acute phase and at follow-up evaluations in both groups. Mann–Whitney U test, two-tailed, was used for cross-sectional analyses to compare study groups at both time points. Medians, interquartile ranges (IQR), and individual points are reported in the text and/or in the figures. Spearman’s correlation test was used to correlate SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia as well as cytokines with immune responses. Data were analyzed and graphed with GraphPad Prism 10.0.2, and p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Study population

Forty-eight unvaccinated patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were hospitalized and consecutively enrolled in this study between March and October 2020 (i.e. T0). After hospital discharge, patients were followed up at the post-COVID-19 Outpatient Clinic of the Clinic of Infectious Diseases, San Paolo Hospital, Milan, at a median of 3 months (IQR 3-4) from symptoms onset (i.e. T1) (Fig. 1). At T1, 38/48 (79%) subjects complained of symptoms compatible with long-COVID (i.e. EPS+ group), whereas 10/48 (21%) subjects did not (i.e. EPS− group). Virologic clearance occurred a median on 29 days from hospital admission (IQR 14-33) in the EPS− group, and 31 days (IQR 24-46) in the EPS+ group (p-value = 0.134). As shown in Table 1, at hospital admission, EPS+ and EPS− groups displayed comparable co-morbidities and similar symptoms, except for dyspnoea, which was more common in EPS+ group. Most individuals presented a radiological evidence of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia (94.7% in the EPS+ and 90% in the EPS−), and maximum oxygen requirements were comparable between the two groups. Regarding clinical presentations, within the EPS+ group, 27 (71.1%) presented fatigue, 16 (42.1%) dyspnoea, 4 (10.5%) anosmia/dysgeusia, 3 (7.9%) diarrhea, 11 (28.9%) pain, and 12 (31.6%) mnestic disorders (Table 1). All viro-immunological parameters detailed below were carried out at both T0 and T1. Furthermore, 33/38 EPS+ patients (87%) were followed up 3 years after acute phase (i.e. T2, IQR 2.9-4.2), while 5 (13%) were lost at follow up. A total of 10/33 (30%) individuals presented persistent symptoms (i.e. late persistent symptoms, EPS + LPS+), whereas 23/33 (70%) EPS subjects achieved full recovery (i.e. EPS + LPS−) (Table 1) (Fig. 1). One EPS+ patient died, and clinical data from 4 EPS+ individuals were unavailable for T2 evaluation (Table 1).

SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral response

First, we assessed the magnitude and functionality of SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral responses, focusing on spike-specific humoral responses. The magnitude was assessed by anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) total antibodies (Abs), whilst functionality by means of the ability to neutralize pseudoviral particles carrying the SARS-CoV-2 D614G glycoprotein (Neutralization, ID50) or to mediate Fc-effector functions as measured with an antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC, %) assay.

A significant increase of total RBD-specific Abs and of their ability to induce ADCC over time was observed in EPS− but not in EPS+ subjects (Fig. 2a, b). This resulted in a trend towards higher levels of RBD-specific total Abs in the EPS+ vs EPS− at T0 (2.2, 1.2–3.5 IQR, vs 1.2, 0.7–2.5 IQR, p-value = 0.08, in EPS+ and EPS−, respectively). Likewise, whereas EPS− individuals increased over time also their ability to neutralize free pseudoviral particles, EPS+ subjects showed a striking decrease (Fig. 2c). Finally, the levels of the above-mentioned SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral responses in both groups appeared to be higher than the pre-pandemic healthy controls, further highlighting the specificity of such responses.

a Total anti-RBD antibodies expressed as AUC. b SARS-CoV-2-specific ADCC expressed as percentage. c SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralizing activity expressed as half maximal inhibitory plasma dilution (ID50). Red/blue dots: individual values; red/blue lines connecting median values at T0 and T1; longitudinal analyses (T1 compared to T0): Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P values in red/blue); cross-sectional analyses (at each time point): Mann–Whitney U test (P values in black); EPS− (T0, T1): n = 10, 10; EPS+ (T0, T1): n = 37 (ADCC and ID50) or 38 (Abs); dotted lines: median of 7 pre-pandemic healthy controls. Statistical significance at p-value < 0.05.

B cells immunophenotypes

We next assessed whether the humoral impairments observed in the EPS+ group mirrored an altered pool of total RBD-specific B cells or a defective maturation of B cells.

Analysis of the maturation profile of total B cells (CD3-CD19+), based on CD21 and CD27 expression, showed similar kinetics and levels in both groups, with a significant increase of classical memory B cells (classical MBCs) (Fig. 3a, b), vis-à-vis a trend towards decreased activated MBCs. The seemingly lower levels of naïve B cells at baseline in the EPS− group did not reflect statistical significance most likely due to the high data spread. The majority of antibody-secreting cells [CD20-CD38+ cells, encompassing plasmablasts (PBs) and plasmacells (PCs)] did not express CD138 suggesting a predominance of PBs40(Supplementary Fig. 3a–c).

a Proportion of naïve B cells (CD21+CD27-), activated memory B cells (MBCs) (CD21-CD27+/-), and classical MBCs (CD21+CD27+) expressed within the total of non-antibody secreting B cells (CD19+CD3-CD20-CD38+/−). b Frequency (%) of classical MBCs (CD21 + CD27+). c Proportion of total MBCs (activated and classical) expressing IgM (IgD-IgM+) or IgD (IgD+IgM−), and IgG or IgA within the pool of IgD-IgM- MBCs. d Frequency (%) of total MBCs (activated and classical) expressing IgA (IgD-IgM-IgG-IgA+). e Frequency (%) of RBD-specific (RBD-Biotin-Streptavidin-PE-Vio770+RBD-Biotin-Streptavidin-PE+) B cells expressed on the total of B cells (CD3-CD19+). f Frequency (%) of total MBCs (activated and classical) expressing CD24. Stacked graphs: descriptive graph showing the proportions within each group at each time point, statistics is shown in the dot-plots; red/blue dots: individual values; red/blue lines connecting median values at T0 and T1; longitudinal analyses (T1 compared to T0): Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P values in red/blue); cross-sectional analyses (at each time point): Mann–Whitney U test (P values in black); EPS− (T0, T1): n = 7, 10; EPS+ (T0, T1): n = 10, 10; dotted lines: median of 7 pre-pandemic healthy controls. Statistical significance at p-value < 0.05.

We next assessed BCRs class-switching, which is associated to BCR affinity maturation, a crucial step in high-affinity neutralizing antibodies41. Similar kinetics of unswitched IgD+ MBCs, pre-switched IgM+ MBCs and switched IgG+ MBCs were observed in the two groups40 (Fig. 3c). However, whereas the EPS− group showed a significant increase over time of class-switched IgA+ MBCs, the EPS+ group did not (Fig. 3d). Additionally, a trend towards increased percentages of RBD-specific B cells over time was observed only in the EPS− (Fig. 3e).

Finally, given the emerging role of the metabolic regulator CD24 on memory B cells, mostly in unswitched and resting B cells42,43,44,45, we evaluated CD24 in this cohort. Despite no statistically significant changes, the fact that the majority of MBCs expressed CD24+ may align with the high proportion of IgD+ and IgM+ MBCs observed in both groups (Fig. 3f).

Altogether, while not showing coarse B cells maturation defects, individuals showing early persistent symptoms fail to increase the pool of IgA+ class-switched MBCs as well as total RBD-specific B cells, in the backdrop of similar trends of classical and activated MBCs expressing CD24. Importantly, the levels of the different B cells subpopulations appeared to be comparable to those of the pre-pandemic healthy controls, further highlighting the lack of B cells maturation defects.

T cell immunophenotypes

The analysis of the maturation profile of CD4 T cells, based on CD45RA and CCR7 expression, included naïve, central memory (TCM), effector memory (TEM), and effector memory T cells re-expressing CD45RA (TEMRA). Similar kinetics and levels were shown in both groups, except for a trend towards increased levels of CD4 TEMRA observed only in the EPS+ group (Fig. 4a, b, Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). Similarly, no differences in the kinetics nor in the levels of circulating T follicular helper cells (cTfh, CXCR5+) and regulatory T cells (TREG, CD25 + CD127−) were observed (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e). We next evaluated the degree of exhaustion and senescence by means of PD-1 and CD57 expression. The frequency of CD4 T cells expressing at least one of the two markers did not significantly differ between groups at both time points, nor their kinetics, except for an increase of PD-1-CD57 + CD4 TEMRA cells in EPS− only (Fig. 4c, d). Furthermore, the proliferative potential did not seem to vary according to the presence of persistent symptoms (Supplementary Fig. 5a–e). Finally, we evaluated whether CD4 T cells of individuals with early persistent symptoms showed a skewing towards Th1 (CXCR3 + CCR6−), Th2 (CXCR3-CCR6−) or Th17 (CXCR3-CCR6+) phenotypes46,47,48,49. Interestingly, Th1 subtypes increased in both groups, except for TEMRA which remained constant in the EPS+ group while increasing in the EPS− (Fig. 4e, f, Supplementary Fig. 6). Additionally, despite similar kinetics of Th2 CD4 subsets in both groups, the levels appeared to be slightly higher in the EPS+ at both time points, reaching statistical significance for cTfh at T0 (Fig. 4g).

a Proportion of naïve T cells (CCR7+CD45RA+), central memory TCM (CCR7+CD45RA-), effector memory TEM (CCR7-CD45RA-), and effector memory re-expressing CD45RA TEMRA (CCR7-CD45RA+) expressed within the pool of total CD4 T cells (CD3+CD4+). b Frequency (%) of CD4 TEMRA (CCR7-CD45RA+). c Proportion of exhausted (CD57-PD1+), senescent (CD57+PD1-), and double-positive (CD57+PD1+) CD4 TEMRA. d Frequency (%) of senescent CD4 TEMRA (CD57+PD1-). e Proportion of CD4 TEMRA with a Th1 (CCR6-CXCR3+), Th2 (CCR6-CXCR3-) or Th17 (CCR6+CXCR3-) phenotype. f Frequency (%) of CD4 TEMRA with a Th1 phenotype. g Percentage of CD4 TEMRA with a Th2 phenotype. h Proportion of naïve T cells (CCR7+CD45RA+), central memory TCM (CCR7+CD45RA-), effector memory TEM (CCR7-CD45RA-), and effector memory re-expressing CD45RA TEMRA (CCR7-CD45RA+) expressed within the pool of total CD8 T cells (CD3+CD8+). Stacked graphs: descriptive graph showing the proportions within each group at each time point, statistics is shown in the dot-plots; red/blue dots: individual values; red/blue lines connecting median values at T0 and T1; longitudinal analyses (T1 compared to T0): Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P values in red/blue); cross-sectional analyses (at each time point): Mann–Whitney U test (P values in black); EPS− (T0, T1): n = 6, 8; EPS+ (T0, T1): n = 11, 11; dotted lines: median of 7 pre-pandemic healthy controls. Statistical significance at p-value < 0.05.

Overall, the trend of significant CD4 TEMRA increase over time, observed exclusively in the EPS+ group did not mirror heightened senescence or exhaustion, nor proliferation potential or Th1/Th2/Th17 skewing. Finally, the maturation profile of CD4 T cells did not appear to be different than the pre-pandemic healthy controls.

The analysis of the maturation profile of CD8 T cells showed similar maturation profiles over time characterized by increased CD8 TEMRA, and decreased naïve CD8 T cells, with no significant differences between groups at both time points (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 7a–d). Exhaustion and senescence did not significantly differ between groups at both time points nor between time points in each group (Supplementary Fig. 8). Overall, a decrease over time of PD-1 + CD57− and of PD-1 + CD57+, as well as an increase of PD-1-CD57 + CD8 T cells were observed in both groups (Supplementary Fig. 8). We next evaluated whether such subsets were endowed with a higher cytotoxic or proliferative potential by means of PRF and Ki67 expression, respectively. A trend of PRF + CD8 TEMRA and TEM cells increase over time was observed in both groups reaching statistical significance in EPS− and EPS+ individuals, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 9). Finally, we assessed whether CD8 T cells of the EPS+ were characterized by a different cellular polarization. The levels of effector CD8 T cells with a Tc1, Tc2 or Tc17 phenotype did not differ between groups at both time points, nor their kinetics (Supplementary Fig. 10). Overall, the levels of CD8 TEMRA with a Tc1 phenotype decreased over time only in the EPS+ group, whereas the levels of TCM with a Tc17 phenotype decreased in both groups, reaching statistical significance in EPS+ (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Therefore, the changes observed in CD8 effector T cells phenotypes do not appear to be related to early persistent symptoms. However, the EPS+ group showed a reduction over time of CD8 TEMRA Tc1, and a predominance of Tc2 phenotype in the CD8 T subpopulations even though still comparable to pre-pandemic healthy controls.

SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses

We next assessed the magnitude and functionality of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell response by means of TCR stimulation-induced markers upregulation to identify Ag-specific non-polarized cytokine-independent cells (i.e. co-expression of CD69 and CD137, AIM assay50,51), and of Th1-cytokines production upon SARS-CoV-2 re-challenge (i.e. IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, ICS assay).

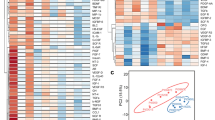

Overall, the pool of total Ag-specific CD4 T cells (CD69 + CD137+) declined over time in both groups, even though the trend appeared emphasized in EPS+ subjects, reaching significance for TEM and TCM (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the downward trend did not reflect any striking differences in the percentages of Th1-cytokine-producing SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells (Fig. 5), except for higher levels of IFN-γ + CD4 TEMRA at T0, and of IL-2 + TEM as well as TNF-α cTfh at T1 in the EPS+ group. Overall, the CD8 T cell response was lower than CD4 T cell response, with no major differences in the magnitude nor in type 1 functionality. In particular, a rise of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8 TEMRA producing IFN-γ and TNF-α was observed in both groups reaching statistical significance in the EPS+ (Supplementary Fig. 11).

a Frequency (percentage, %) of SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells within the pool of CD4 cTfh, TEMRA, TCM, TEM, and TREG, as determined by AIM assay (CD69+CD137+). b Proportion of cytokine (TNF-α, IFN-α, IL-2)-producing SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 cThf, TEMRA, TCM, TEM, and TREG CD4 T cells. Red/blue dots: individual values; red/blue lines connecting median values at T0 and T1; longitudinal analyses (T1 compared to T0): Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P values in red/blue); cross-sectional analyses (at each time point): Mann–Whitney U test (P values in black). Statistical significance at p-value < 0.05; EPS− (T0, T1): n = 6, 8; EPS+ (T0, T1): n = 11, 11; dotted lines: median of 7 pre-pandemic healthy controls; pie-charts: proportion of cytokine-producing CD4 T cells expressed as percentage within the pool of cThf, TEMRA, TCM, TEM, and TREG.

Therefore, in our cohort, the EPS+ group did not show striking impaired SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses, except for a marked reduction over time of total SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells in the backdrop of higher levels of IFN-γ + CD4 TEMRA at T0 and IL-2 TEM as well as TNF-α cTfh at T1. The SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses of both groups appeared to be higher than pre-pandemic healthy controls, further highlighting the specificity of such responses.

SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and immune dysregulation

When considering the entire cohort, a slight and yet significant decrease in median SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia was observed (T0, 3.63 log10(copies/mL), 3–4 IQR, vs T1, 3.6 log10(copies/mL), 2.9-3.8 IQR, p-value = 0.03) (Fig. 6a). However, when stratifying for persistent symptoms at 3 months after symptoms onset, no differences were observed in the kinetics nor in the levels between groups (Fig. 6a).

a SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia expressed as log10(copies/mL); Spearman’s correlation between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral response at T0 in the overall cohort (b), at T1 in the overall cohort (c), at T0 in EPS- individuals (d), at T1 in EPS- individuals (e), at T0 in EPS+ individuals (f), and T1 in EPS+ individuals (g). Red/blue dots: individual values; red/blue lines connecting median values at T0 and T1; longitudinal analyses (T1 compared to T0): Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P values in red/blue); cross-sectional analyses (at each time point): Mann–Whitney U test (P values in black); EPS− (T0, T1): n = 9, 9; EPS+ (T0, T1): n = 38, 38; heatmap of correlations: number in each cell represent the r value, asterisk represents statistically significant r value. Statistical significance at p-value < 0.05.

Although SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia did not seem to be directly linked with persistent symptoms 3 months after symptoms onset, we explored whether it was associated with humoral dysregulation. Interestingly, when considering the entire cohort, no significant correlations were observed between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and any of the humoral parameters at both time points (Fig. 6b, c). However, when stratifying according to persistent symptoms, different patterns emerged: at T1 EPS+ patients showed a positive correlation between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and ADCC (T1: r = 0.36, p-value = 0.03), whereas the EPS− showed an opposite trend (T1: r = -0.53, p-value = 0.1) (Fig. 6d–g).

Likewise, while in the entire cohort, no significant correlations were observed between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and cellular immune parameters (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b), when stratifying for early persistent symptoms, total CD4 TEMRA positively correlated with SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia only in the EPS+ group (T0: EPS+: r = 0.86, p-value = 0.02; EPS−: r = -0.54, p-value = 0.3) (Supplementary Fig. 12c–f).

Therefore, while baseline SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia appears to be associated with total CD4 TEMRA in EPS+ subjects, SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia was associated with ADCC at follow-up.

Cytokine milieu and immune dysregulation

When considering the entire cohort, an overall decrease overtime of peripheral cytokines was observed, reaching statistical significance for IFN-α and IL-6, and such downward trend did not change when stratifying for early persistent symptoms (Fig. 7a, b, Supplementary Fig. 13). As expected, the levels of the peripheral cytokines, except for IL-4, appeared to be higher in both groups compared to pre-pandemic healthy controls. Interestingly, the link between peripheral cytokines and immune markers measured in this study did not seem to be associated with persistent symptoms 3 months from symptoms’ onset (Fig. 7c–h, Supplementary Fig. 14).

a IFN-α peripheral concentration expressed in pg/mL. b IL-6 peripheral concentration expressed in pg/mL; Spearman’s correlation between peripheral cytokines and SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral response at T0 in the overall cohort (c), at T1 in the overall cohort (d), at T0 in EPS- individuals (e), at T1 in EPS- individuals (f), at T0 in EPS+ individuals (g), and T1 in EPS+ individuals (h). Red/blue dots: individual values; red/blue lines connecting median values at T0 and T1; longitudinal analyses (T1 compared to T0): Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P values in red/blue); cross-sectional analyses (at each time point): Mann–Whitney U test (P values in black); EPS− (T0, T1): n = 9, 10; EPS+ (T0, T1): n = 10, 10; heatmap of correlations: number in each cell represent the r value, bold-underlined number in each cell represents statistically significant r value; dotted lines: median of 7 pre-pandemic healthy controls. Statistical significance at p-value < 0.05.

The above-mentioned data suggest that peripheral inflammation is not associated with persistent symptoms 3 months from symptoms onset, nor to long-COVID-related immune dysfunction or SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia in our cohort.

Early viro-immunological markers associated with late persistent symptoms

We finally aimed to assess whether EPS+ individuals with 3 years persistent symptoms (i.e. EPS + LPS+) showed different levels of SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia, peripheral cytokines and SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral responses during both the acute disease (i.e. T0) and/or 3 months from symptoms onset (i.e. T1) compared to EPS+ individuals who resolved symptoms 3 years from symptoms onset (i.e. EPS + LPS−).

Interestingly, compared to EPS + LPS-, EPS + LPS+ subjects did not show different trajectories in the levels of RBD-specific Abs, neutralizing activity nor ADCC, nor different levels at both time points compared to EPS + LPS− individuals (Fig. 8a). Similarly, the trajectories of peripheral cytokines of EPS + LPS+ individuals mirrored those of the EPS + LPS− group, with no significant differences in cytokine levels between the two groups at either time points (Fig. 8b).

a SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral responses in EPS+ subjects who resolved symptoms 3 years from symptoms onset (i.e. EPS + LPS−) and EPS+ individuals who showed persistent symptoms (i.e. EPS + LPS+). Solid line/filled square: SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies; dashed line/open square: ADCC activity of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies; dashed line/open circle: Neutralizing activity of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies. b SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and peripheral cytokines in EPS+ subjects who resolved symptoms 3 years from symptoms onset (i.e. EPS + LPS−) and EPS+ individuals who showed persistent symptoms (i.e. EPS + LPS+). Dashed lines: SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia; solid lines: cytokines. Longitudinal analyses (T1 compared to T0): Wilcoxon signed-rank test; cross-sectional analyses (at each time point): Mann–Whitney U test. *Statistical significance at p-value < 0.05.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, we assessed humoral and cellular responses during both the acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and the recovery phase in a cohort of hospitalized, unvaccinated COVID-19 individuals who showed symptoms compatible with long-COVID a median of 3 months after symptoms onset as compared to a matched group who did not. We also explored the role of SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and peripheral inflammation as potential underlying pathogenetic mechanisms.

The prevalence of long-COVID is estimated to be between 5–80% depending on the study populations, case definitions, available data, as well as time of follow-up52. Our cohort is featured by individuals infected during the first wave of the pandemic, not vaccinated or previously infected, acutely ill and hospitalized, therefore the prevalence of long-COVID in our cohort may be slightly higher compared to other studies. Importantly, only 30% of them still showed persistent symptoms compatible with long-COVID a median of 3 years after symptoms. Albeit similar for age, sex, comorbidities, type and length of symptoms during acute COVID-19, EPS+ patients were characterized by a dysregulated SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral response. In particular, despite constant levels of SARS-CoV-2-specific Abs and ADCC, EPS+ patients showed a decline over time in the ability to neutralize free viral particles, suggesting either a specific functional dysregulation or a different Ig subclass polarization. Our findings confirm and extend previous studies showing lower levels of positive neutralizing Abs27 or similar levels of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG53 in individuals developing long-COVID at 12 or 9 months. Furthermore, the observed trend of elevated baseline levels of RBD-specific Abs in EPS+ individuals aligns with previous findings suggesting that critically ill patients exhibit extrafollicular B cell activation54. This activation correlated with a significant expansion of antibody-secreting cells and the early production of high concentrations of SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralizing antibodies. However, these patients still experienced severe COVID-19, indicating that an early humoral response alone was insufficient to resolve the disease. Furthermore, the absence of germinal centers in the spleens and lymph nodes of individuals who succumbed to COVID-19 has been documented55. Our findings build on these observations, suggesting that acutely ill, hospitalized COVID-19 patients with persistent symptoms 3 months after onset may exhibit a robust early extrafollicular response which was not sufficient to control the disease at 3 months. Indeed, this response did not seem to be followed by a proper maturation of the humoral response, as evidenced by the lack of a significant increase in antibody levels over time and a marked decline in neutralizing capacity. Interestingly, these spike-specific humoral alterations did not seem to be associated with the persistence of symptoms compatible with long-COVID three years after symptoms onset. However, this study did not evaluate the role of non-Spike-specific humoral responses, which may also play a crucial role in long-COVID development.

Interestingly, we additionally showed that EPS+ individuals failed to increase the pool of total RBD-specific B cells and of total IgA+ MBCs in the backdrop of increased trend of classical MBCs, suggesting that an upstream dysregulation may potentially affect the downstream production of functional Abs. This is further supported by the fact that in EPS− individuals the increase of classical MBCs goes in parallel with the increase of total RBD-specific Abs, ADCC, neutralization, RBD-specific B cells, and total IgA+ MBCs. Despite the contribution of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA+ MBCs within the pool of total IgA+ MBCs could not be assessed in our cohort, the importance of MBCs as well as of IgA+ responses have already been shown. Indeed, Newell K.L. and collaborators studied non-hospitalized individuals at 3 months from symptoms onset. They observed a negative correlation between symptoms duration and the expansion of MBCs56. Furthermore, a study of individuals with mild disease evaluated 3 months from symptoms onset, who did not have long-COVID, showed an expansion of RBD-specific MBCs, mainly classical and enriched for IgG+ MBCs57. During acute disease, IgA dominates the early neutralizing response vis-à-vis an expansion of IgA+ PBs with mucosal homing potential58, and individuals with an early, robust mucosal secretory IgA in oral fluid are more likely to quickly clear the virus and resolve symptoms59. Therefore, the increase of total IgA+ MBCs together with total RBD-specific B cells observed only in EPS− individuals may reflect a correct development of mucosal immunity, which is necessary to clear the virus and resolve symptoms.

Furthermore, EPS+ individuals increased over time the pool of total highly differentiated effector CD4 TEMRA, even without signs of enhanced exhaustion, senescence nor different proliferation potential. Altogether, these findings suggest a T-cell receptor-independent increase of bystander CD4 T cells, which could potentially impact immune responses during and beyond SARS-CoV-2 infection. For instance, bystander activated CD4 T cells can increase susceptibility to autoimmune disease in murine models60,61, as well as CD8 T cells can contribute to liver injuries during acute hepatitis A infection62. Moreover, we have not found differences in the levels of total SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells nor of SARS-CoV-2-specific cytokine-producing T cells between groups, except for higher levels of IFN-γ-producing CD4 TEMRA at baseline and of IL-2-producing CD4 TEM as well as TNF-α cTfh at T1 in EPS+ as well as a reduction over time of total SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells. Despite some studies showed lower cytokine-producing T responses in individuals developing long-COVID28,53, a study on unvaccinated individuals evaluated at 1 year, both hospitalized and non-hospitalized, did not find differences in the backdrop of increased TEMRA cells26,27. Therefore, while individuals developing long-COVID do not exhibit significant defects in SARS-CoV-2-specific functional T cells, they may struggle to sustain a consistent pool of antigen-specific cells over time as they attempt to generate cytokine-producing effector cells.

Even though SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia is a useful correlate of disease severity in the acute phase35,63,64,65,66, the biological meaning behind the enduring detection of RNA viral fragments and its association with clinical outcomes in the long term are still under debate. For instance, in moderate/mild individuals, a higher percentage of initially RNAemic patients developing long-COVID 1-3 months from symptoms onset was observed67, or an association of RNAemia was found only with certain types of clinical manifestations19.

Indeed, the viral clearance mainly assessed in the respiratory tract appeared to be a crucial aspect in long-COVID development as a longer time of SARS-CoV-2 clearance was associated with long COVID development in various studies mainly focused on respiratory samples30,31,33. These data, associated with the above-mentioned involvement of mucosal immunity59, suggests that the interplay between mucosal immunity and viral clearance is strongly linked to long-COVID development. These parameters may follow a different kinetics in peripheral circulation. Indeed, in the present study, despite the time of viral clearance from the blood did not differ, SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia seemed to differently impact immune responses in the two groups. In particular, SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia positively correlated with total CD4 TEMRA during acute disease and with SARS-CoV-2-specific ADCC at follow-up exclusively in EPS+ individuals. Therefore, the detection of circulating viral genome fragments may have different implications according to long-COVID development. In particular, in EPS+ individuals, after an initial overall immune activation, there might be persistent infected cells in undefined anatomical districts which perpetuate tissue damage by Fc-mediated effector functions. In stark contrast, the neutralization ability, which shrank only in the EPS+ group, was not correlated with RNAemia supporting the importance of tissue damage after acute disease in the pathogenesis of long-COVID and leaving the question of the inability to control viral replication over time unanswered. Our results extend recent data from Cervia-Hasler C. and colleagues, who, by demonstrating an imbalanced terminal complement complex (TCC) formation and elevated tissue injury markers in the blood of subjects with long-COVID, suggested complement deposition as an additional mechanism of tissue damage in long-COVID development21.

Finally, despite inflammation was shown to be associated to long-COVID development in some studies11, we and others did not find such an association12. These data may be related to the fact that the entire cohort was severely ill during acute disease, hence inflammation may have already been equally triggered.

In conclusion, our study offers an overview of the percentages of key B and T cell subpopulations, with a primary focus on SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral and cellular immunity up to 3 months from symptoms onset. Therefore, the involvement of other biological mechanisms in the development of long-COVID cannot be excluded in this study68. Additionally, while we were unable to detect statistical differences in the cross-sectional analysis for most of the markers, most likely due to the sample size, the longitudinal analysis captured the evolution over time, revealing different patterns in the two groups. Indeed, differences in trajectories may reflect the ability to mount and sustain different responses. In particular, we demonstrated that acutely ill hospitalized unvaccinated COVID-19 patients, showing symptoms compatible with long-COVID three months from symptoms onset, feature a dysregulated multi-layered SARS-CoV-2- and non-SARS-CoV-2-specific immune response. This was in contrast to similar acutely ill hospitalized unvaccinated COVID-19 patients who did not show persistent symptoms 3 months from symptoms onset. In particular, the EPS+ group drastically reduces over time the neutralization potential and the pool of total SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in the backdrop of increased total TEMRA, and show higher levels of cytokine-producing effector CD4 cells. At the same time, they fail to increase over time the pool of total RBD-specific B cells and IgA+ MBCs. Our data do not support an association of SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia, nor of peripheral inflammation, with the immune signature of EPS+. However, SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia appears to initially trigger a shift towards non-SARS-CoV-2-specific total terminally differentiated T cells, and secondly towards tissue damage mediated by Fc-mediated effector functions. The complex interplay between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia, viral persistence and immune dysregulation in the pathogenesis of long-COVID requires further evaluation, particularly in light of other pathogenic mechanisms that have been identified.

References

Rovito, R. et al. Hallmarks of severe COVID-19 pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 13, 912336 (2022).

Lippi, G., Henry, B. M., Favresse, J. & Plebani, M. Addressing standardized definitions of post-COVID and long-COVID. Clin. Chem. Lab Med. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0390 (2023).

Soriano, J. B. et al. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, e102–e107 (2022).

Nalbandian, A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 27, 601–615 (2021).

Huang, Y. et al. COVID symptoms, symptom clusters, and predictors for becoming a Long-Hauler looking for clarity in the Haze of the pandemic. Clin. Nurs. Res. 31, 1390–1398 (2022).

Bai, F. et al. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 28, 611.e619–611.e616 (2022).

Thompson, E. J. et al. Long COVID burden and risk factors in 10 UK longitudinal studies and electronic health records. Nat. Commun. 13, 3528 (2022).

Whitaker, M. et al. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms in a community study of 606,434 people in England. Nat. Commun. 13, 1957 (2022).

Dennis, A. et al. Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a prospective, community-based study. BMJ Open 11, e048391 (2021).

Sudre, C. H. et al. Author Correction: attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat. Med. 27, 1116 (2021).

Davis, H. E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M. & Topol, E. J. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 133–146 (2023).

Swank, Z. et al. Persistent circulating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike is associated with Post-acute Coronavirus Disease 2019 Sequelae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, e487–e490 (2023).

Liu, Q. et al. Gut microbiota dynamics in a prospective cohort of patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Gut 71, 544–552 (2022).

Su, Q., Lau, R. I., Liu, Q., Chan, F. K. L. & Ng, S. C. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome and gut dysbiosis linger beyond 1 year after SARS-CoV-2 clearance. Gut 72, 1230–1232 (2023).

Rojas, M. et al. Autoimmunity is a hallmark of post-COVID syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 20, 129 (2022).

Ambrosino, P. et al. Clinical assessment of endothelial function in convalescent COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis with meta-regressions. Ann. Med. 54, 3234–3249 (2022).

Son, K. et al. Circulating anti-nuclear autoantibodies in COVID-19 survivors predict long COVID symptoms. Eur. Respir. J. 61, https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00970-2022 (2023).

Peluso, M. J. et al. Chronic viral coinfections differentially affect the likelihood of developing long COVID. J. Clin. Invest. 133, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI163669 (2023).

Su, Y. et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell 185, 881–895.e820 (2022).

Merad, M., Blish, C. A., Sallusto, F. & Iwasaki, A. The immunology and immunopathology of COVID-19. Science 375, 1122–1127 (2022).

Cervia-Hasler, C. et al. Persistent complement dysregulation with signs of thromboinflammation in active Long Covid. Science 383, eadg7942 (2024).

Taquet, M. et al. Acute blood biomarker profiles predict cognitive deficits 6 and 12 months after COVID-19 hospitalization. Nat. Med. 29, 2498–2508 (2023).

Radke, J. et al. Proteomic and transcriptomic profiling of brainstem, cerebellum and olfactory tissues in early- and late-phase COVID-19. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 409–420 (2024).

Klein, J. et al. Distinguishing features of long COVID identified through immune profiling. Nature 623, 139–148 (2023).

Fang, H. et al. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms minimally impact the development of SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity. Viruses 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/v13050916 (2021).

Galán, M. et al. Persistent overactive cytotoxic immune response in a spanish cohort of individuals with Long-COVID: identification of diagnostic biomarkers. Front Immunol. 13, 848886 (2022).

García-Abellán, J. et al. Immunologic phenotype of patients with long-COVID syndrome of 1-year duration. Front. Immunol. 13, 920627 (2022).

Santa Cruz, A. et al. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 is characterized by diminished peripheral CD8. Nat. Commun. 14, 1772 (2023).

Phetsouphanh, C. et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 23, 210–216 (2022).

Antar, A. A. R. et al. Long COVID brain fog and muscle pain are associated with longer time to clearance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from the upper respiratory tract during acute infection. Front. Immunol. 14, 1147549 (2023).

Pozzi, C. et al. Association between duration of SARS-CoV-2 positivity and long COVID. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77, 1531–1533 (2023).

Ozonoff, A. et al. Features of acute COVID-19 associated with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 phenotypes: results from the IMPACC study. Nat. Commun. 15, 216 (2024).

Ghafari, M. et al. Prevalence of persistent SARS-CoV-2 in a large community surveillance study. Nature 626, 1094–1101 (2024).

Peluso, M. J. et al. Plasma-based antigen persistence in the post-acute phase of COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00211-1 (2024).

Rovito, R. et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and dysregulated immune response in acutely ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 12, 19658 (2022).

Anand, S. P. et al. Longitudinal analysis of humoral immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Spike in convalescent individuals up to 8 months post-symptom onset. Cell Rep. Med. 2, 100290 (2021).

Beaudoin-Bussières, G., Richard, J., Prévost, J., Goyette, G. & Finzi, A. A new flow cytometry assay to measure antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against SARS-CoV-2 Spike-expressing cells. STAR Protoc. 2, 100851 (2021).

Tauzin, A. et al. A single dose of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine BNT162b2 elicits Fc-mediated antibody effector functions and T cell responses. Cell Host Microbe 29, 1137–1150.e1136 (2021).

Tauzin, A. et al. Strong humoral immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 Spike after BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination with a 16-week interval between doses. Cell Host Microbe 30, 97–109.e105 (2022).

Sanz, I. et al. Challenges and opportunities for consistent classification of human B cell and plasma cell populations. Front Immunol. 10, 2458 (2019).

Weisel, F. & Shlomchik, M. Memory B cells of mice and humans. Annu Rev. Immunol. 35, 255–284 (2017).

Mensah, F. F. K. et al. CD24 expression and B cell maturation shows a novel link with energy metabolism: potential implications for patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front. Immunol. 9, 2421 (2018).

Armstrong, C. W. et al. B cell experiments explore the role of CD24, CD38, and energy metabolism in ME/CFS. Front. Immunol. 14, 1178882 (2023).

Sanz, I., Wei, C., Lee, F. E. & Anolik, J. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of human memory B cells. Semin. Immunol. 20, 67–82 (2008).

Claireaux M. et al. Deep profiling of antigen-specific B cells from different pathogens identifies novel compartments in the IgG memory B cell and antibody-secreting cell lineages. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.19.572339 (2023).

Gosselin, A. et al. Peripheral blood CCR4+CCR6+ and CXCR3+CCR6+CD4+ T cells are highly permissive to HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 184, 1604–1616 (2010).

Figueiredo, M. M. et al. T follicular helper cells regulate the activation of B lymphocytes and antibody production during Plasmodium vivax infection. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006484 (2017).

Becattini, S. et al. T cell immunity. Functional heterogeneity of human memory CD4+ T cell clones primed by pathogens or vaccines. Science 347, 400–406 (2015).

Korn, T., Bettelli, E., Oukka, M. & Kuchroo, V. K. IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 485–517 (2009).

Grifoni, A. et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell 181, 1489–1501.e1415 (2020).

Cannons, J. L. et al. 4-1BB ligand induces cell division, sustains survival, and enhances effector function of CD4 and CD8 T cells with similar efficacy. J. Immunol. 167, 1313–1324 (2001).

Cabrera Martimbianco, A. L., Pacheco, R. L., Bagattini, Â. & Riera, R. Frequency, signs and symptoms, and criteria adopted for long COVID-19: a systematic review. Int J. Clin. Pr. 75, e14357 (2021).

Meisinger, C. et al. Post-COVID-19 fatigue and SARS-CoV-2 specific humoral and T-cell responses in male and female outpatients. Front. Immunol. 13, 902140 (2022).

Woodruff, M. C. et al. Extrafollicular B cell responses correlate with neutralizing antibodies and morbidity in COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1506–1516 (2020).

Kaneko, N. et al. Loss of Bcl-6-expressing T follicular helper cells and germinal centers in COVID-19. Cell 183, 143–157.e113 (2020).

Newell, K. L. et al. Switched and unswitched memory B cells detected during SARS-CoV-2 convalescence correlate with limited symptom duration. PLoS ONE 16, e0244855 (2021).

Rodda, L. B. et al. Functional SARS-CoV-2-specific immune memory persists after mild COVID-19. Cell 184, 169–183.e117 (2021).

Sterlin, D. et al. IgA dominates the early neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abd2223 (2021).

Pisanic, N. et al. Early, robust mucosal secretory immunoglobulin A but not immunoglobulin G response to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike in oral fluid is associated with faster viral clearance and coronavirus disease 2019 symptom resolution. J. Infect. Dis. 231, 121–130 (2025).

van Aalst, S., Ludwig, I. S., van der Zee, R., van Eden, W. & Broere, F. Bystander activation of irrelevant CD4+ T cells following antigen-specific vaccination occurs in the presence and absence of adjuvant. PLoS ONE 12, e0177365 (2017).

Lee, H. G. et al. Pathogenic function of bystander-activated memory-like CD4. Nat. Commun. 10, 709 (2019).

Kim, J. et al. Innate-like cytotoxic function of bystander-activated CD8. Immunity 48, 161–173.e165 (2018).

Jacobs, J. L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Viremia is associated with COVID-19 severity and predicts clinical outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab686 (2021).

Fajnzylber, J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat. Commun. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19057-5 (2020).

Augello, M. et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia, skewed T cell responses, inflammation, and severity in hospitalized COVID-19 people living with HIV. iScience 27, 108673 (2024).

Brunet-Ratnasingham, E. et al. Integrated immunovirological profiling validates plasma SARS-CoV-2 RNA as an early predictor of COVID-19 mortality. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj5629 (2021).

Ram-Mohan, N. et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and postacute sequelae of COVID-19. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 9, ofab646 (2022).

Perumal, R. et al. Biological mechanisms underpinning the development of long COVID. iScience 26, 106935 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the patients who agreed to participate in this research. Our special thanks also go to the physicians and at the Clinic of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine at San Paolo Hospital in Milan, and laboratory personnel whose role in the conduct of the study was crucial. We also acknowledge the EuCARE Study group, whose members are reported in the Supplementary Information. This work was supported by a grant from the EuCARE Project under Grant Agreement No 101046016, which is part of the European Union´s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme. This work was partially supported by the following funding: CIHR operating Pandemic and Health Emergencies Research grant #177958 to A.F.; Italian Ministry of Health “Bando Covid-19” (COVID-2020-12371640 to D.M.); Ricerca Corrente” funding from Italian Ministry of Health to IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital. A.F. is the recipient of the Canada Research Chair on Retroviral Entry no. RCHS0235 950-232424; G.B-B. is the recipient of FRQS and IRSC (RN497587-494246) PhD fellowships; V.C. and S.F. are recipients of fellowships awarded from the Experimental Medicine Ph.D. program at the University of Milan; A.T. was supported by a MITACS Elevation postdoctoral fellowship. The purchase of a FACS Symphony A5 was defrayed in part by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health (Agreement 82/2015). The authors acknowledge support from the University of Milan through the APC initiative and the Department of Health Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

R.R. designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, designed the figures, and wrote the manuscript; V.B. performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data; N.C. flow cytometry panel design and samples acquisition on FACSymphony A5; V.C. flow cytometry panel design and samples acquisition on FACSymphony A5; S.F. flow cytometry panel design and samples acquisition on FACSymphony A5; J.M. flow cytometry panel design, samples acquisition on FACSymphony A5 and critically revised the manuscript; C.D.V. flow cytometry panel design and samples acquisition on FACSymphony A5; F.B. enrolled patients and critically revised the manuscript; G.B.B. performed the ADCC assay and critically revised the manuscript; A.T. performed the neutralization assay and critically revised the manuscript; M.A. data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript; C.T. data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript; A.S. critical revision of the manuscript; E.B. critical revision of the manuscript; S.M. data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript; A.F. data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript; S.D.B. data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript; D.M. data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript; G.M. conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

This manuscript has been previously reviewed at another Nature Portfolio journal. The manuscript was considered suitable for publication without further review at Communications Medicine.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rovito, R., Bono, V., Coianiz, N. et al. Multi-layered deep immune profiling, SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and inflammation in unvaccinated COVID-19 individuals with persistent symptoms. Commun Med 5, 155 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00832-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00832-8