Abstract

Background

The task of identifying patient subgroups with enhanced treatment responses is important for clinical drug development. However, existing deep learning-based approaches often struggle to provide clear biological insights. This study aims to develop a deep learning method that not only captures treatment effect differences among individuals but also helps uncover meaningful biological markers associated with those differences.

Methods

We introduce DeepRAB, a deep learning-based framework designed for exploring treatment effect heterogeneity by constructing individualized treatment rule (ITR). In addition, DeepRAB enables model interpretability by facilitating predictive biomarker identification. We evaluate its performance using simulated datasets that vary in complexity, treatment effect strength, and sample size. We also apply the method to the adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) clinical trial data, analyzing patient characteristics and treatment outcomes.

Results

In analyses of simulated data under various scenarios, our findings show the effective performance of DeepRAB for subgroup exploration, and its capability to uncover predictive biomarkers when compared to existing approaches. When applied to the real clinical trial data, DeepRAB demonstrates its practical usage in identifying important predictive biomarkers and boosting model prediction performance.

Conclusions

Our research provides a promising approach for subgroup identification and predictive biomarker discovery by leveraging deep learning. This approach may support more targeted treatment strategies in clinical research and enhance decision-making in personalized medicine.

Plain language summary

In order to improve healthcare, matching patients to effective treatment plans is needed. This study aims to find better ways to identify groups of patients who respond well to certain treatments. We develop a new method called DeepRAB, which uses artificial intelligence to find these patient groups and identify important biomarkers that can predict treatment response. We test DeepRAB using simulated data and real patient data from a clinical trial studying a skin condition called hidradenitis suppurativa. The results show that DeepRAB is successful in identifying meaningful patient groupings and performs better than existing methods. This new approach has the potential to help doctors choose the best treatment options for individual patients, making healthcare more personalized and effective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating, chronic systemic skin condition known for its severe and prolonged symptoms1,2,3. AbbVie Pioneer I & Pioneer II trials4 demonstrate significant treatment difference in achieving Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR)5 at 12 weeks (P-value = 0.003 and P-value < 0.001 for Pioneer I and Pioneer II, respectively.) in HS patients treated with Humira for 12 weeks. In 2015, the European Medicines Agency granted approval for the use of adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) to treat active moderate to severe HS in adults who had not responded to conventional therapies. There is a long-term treatment strategy included in the European Medicines Agency Summary of Produce Characteristics for Humira, which provides patients the opportunity to benefit from extended treatment beyond 12 weeks. This strategic extension is underpinned by successful identification of specific biomarkers associated with the heterogenous treatment effect of Humira that leads to successful subgroup identification4,5,6,7. In precision medicine, these biomarkers associated with treatment effect heterogeneity are often referred to as predictive biomarkers. For pharmaceutical development, the exploration and interpretation of predictive biomarkers is one of the most intriguing scientific questions. With respect to statistical modeling, the exploration and interpretation of predictive biomarker is closely connected with the causal inference due to its targeted association with treatment effects8. The fundamental challenge of causal inference lies in the unobservable nature of counterfactuals (the clinical outcome of a patient if he/she receives an alternative treatment). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop methods that combine traditional machine learning and causal inference frameworks for predictive biomarker identification and individualized treatment rule (ITR) exploration. Various existing methods have been proposed for this topic, including Meta-learning9, Q learning10,11 and D-learning12. Although these frameworks have been applied across various machine learning models for predictive biomarker identification, the exploration of Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) for this purpose is still in its early stages.

DNNs has shown success in handling complex biomarker-treatment response relationship, as well as in addressing diverse biomedical tasks, including genomics13, genome-wide association studies14 and promoters15. Meanwhile, some DNN-based causal inference methods aim to predict outcomes across multiple treatments and dosages16, yet they do not explicitly frame ITRs nor do they focus on biomarker selection. While DNNs have been employed in exploring ITR17, this method often take an indirect approach by being pre-trained on existing models. This limitation hampers their ability to directly evaluate predictive biomarkers. Other studies have explored DNN-based techniques for feature selection, such as Concrete Autoencoder (CAE)18. However, it should be noted that these methods can only be extended to the identification of prognostic biomarkers due to their specific focus on the relationship between covariates and disease outcomes instead of the relationship between individual treatment effects. Hence, the need for a DNN model to streamline predictive biomarker selection is pressing.

To tackle the aforementioned challenges, we introduce a DNN architecture called deep learning-based ranking method for subgroup and predictive biomarkers identification (DeepRAB). By utilizing the DNN’s capacity to approximate any continuous mappings, DeepRAB can potentially model complex biomarker–causal effect relationships (e.g., linear, non-linear, multi-level interactions, etc.). Furthermore, our approach integrates the A-learning technique into the loss function19,20, allowing for the direct estimation of ITRs. Unlike the non-transparent DNN models, our approach employs CAE techniques to select predictive biomarkers, rendering our model interpretable. Taken together, the DeepRAB procedure offers several distinctive features: (i) it enjoys the DNN properties, thereby achieving superior performance in capturing complex data representations; (ii) it demonstrates resilience even in the presence of weak effect signals; (iii) it exhibits robustness when detecting interactive treatment effects; (iv) it can handle both continuous and binary endpoints.

Our methods have been successfully applied to identify HS patient subgroups that exhibit varying responses to extended Humira treatment using biomarkers, clinical data, and demographic information. This application underscores the potential of DeepRAB in personalizing Humira treatments for patients. Additionally, we showcase the power of DeepRAB by demonstrating its superior performance compared to existing methods using simulated data. Overall, DeepRAB offers important implications not only for developing HS treatment strategy but also for the broader landscape of clinical drug development.

Methods

Cohort data set

The analysis population in this study comprised AbbVie PIONEER I (ClinicalTrials.gov numbers: NCT01468207) and II (ClinicalTrials.gov numbers: NCT01468233) patients who are re-randomized to either continuation of adalimumab weekly dosing or withdrawal from adalimumab (placebo) in period B after initial treatment of adalimumab weekly dosing for 12 weeks, Fig. 1. The proportion of female participants is 63.8% in PIONEER I and 67.8% in PIONEER II. The mean (standard deviation) age of participants is 37.0 (11.1) years in PIONEER I and 35.5 (11.1) years in PIONEER II. A total of 199 patients (99 continued adalimumab weekly dosing, 100 withdrawn from adalimumab weekly dosing) in period B on the integrated data from the two studies were included for this analysis. Based on the study team discussion, clinically relevant candidate biomarkers are included: % reduction in AN count at week 12, AN count at week 12, AN count at week 0, draining fistula count at week 0, draining fistula count at week 12, reduction in draining fistula count at week 12, abscess count at week 0, reduction in abscess count at week 12, Hurley stage at week 0, smoking status, abscess count at week 12, initial HiSCR responder status at week 12 and concomitant use of antibiotics.

In Period A, patients received induction dosing: 160 mg at Week 0, 80 mg at Week 2, and 40 mg starting at Week 4. Week-12 HiSCR responders entered Period B and continued treatment through Week 36 or until loss of response (defined as a \(\ge\)50% decrease in AN count gained between baseline and Week 12). Non-responders at Week 12 continued through at least Week 26, and up to Week 36. Re-randomization in Period B for patients initially treated with adalimumab was stratified by Week-12 HiSCR status and baseline Hurley Stage (II vs. III). Stratification in PIONEER I and II also considered concomitant antibiotic use. Patients could enter a multi-center, 60-week open-label extension (OLE) study following Period B. The design informs the modeling analysis by providing a framework for identifying treatment benefit subgroups based on response trajectories and baseline clinical features. HiSCR: Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response; AN: abscesses and inflammatory nodules; OLE: open-label extension; HS: hidradenitis suppurativa; LOR: loss of response. ew: every week; eow: every other week.

Ethics approval and informed consent

The two clinical trials included in this study are conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, applicable regulatory requirements, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocols (AbbVie protocol number M11-313; EudraCT number 2011-003400-20) are developed collaboratively by the investigators and the sponsor (AbbVie) and are approved by the independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each participating site. Written informed consent is obtained from all participants prior to enrollment, and this consent included permission for secondary analyses of data collected during the clinical trials. While the names of the specific review boards and institutions are not publicly disclosed in full, ethical oversight and site participation details are documented in the original publication of the trials4 and on file with the study sponsor (AbbVie).

Subgroup identification framework

We denote the observed data by {(Xi, Ai, Yi), \(i=1,\ldots ,n\)} consisting of \(n\) independent patients, where \({Y}_{i}\) denotes outcome, Xi and Ai represents covariate of biomarkers and treatment assignment for ith subjects. We adopt the Neyman-Rubin potential outcome framework in causal inference21,22. In this framework, only one of the potential outcomes can be observed, that is, \({Y}_{i}\) \(={\frac{1}{2}\left(\right.1+A}_{i}\))\({Y}_{i}(1)+\frac{1}{2}\)(\({1-A}_{i}\)) \({Y}_{i}(-1)\), where Yi (1) and Yi (-1) are the potential outcomes if the patient i receives a treatment \(({A}_{i}=1)\) and a control \(({A}_{i}=-1)\), respectively. Let (X, A, Y) denote identically distributed copies of observed data, the completely unspecified regression model is formulated as follows:

where \(Z\left(X\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left[E\left(Y|A=1,X\right)-E\left(Y|A=-1,X\right)\right]\) is a contrast function that reflects treatment effects given \(X\) and \(H\left(X\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left[E\left(Y|A=1,X\right)+E\left(Y|A=-1,X\right)\right]\) is a function that reflects the prognostics effect of \(X\). The estimator of \(Z\left(X\right)\) is our interest in subgroup identification, as it reflects treatment effect heterogeneity. Our goal is to estimate the treatment difference Z(X) as the metric for summarizing ITRs without the need to estimate \(H(\cdot ),\) then biomarker importance can be assessed based on their influence on \(Y\) only via \(Z(X)\). Nonetheless, it’s important to note that not all subgroup identification methodologies are designed to target \(Z(X)\); instead, certain methods might focus on deriving a useful transformation of \(Z(X)\)19,23.

We construct a personalized benefit scoring system, defined as \(f(X)\) with the following two properties: i) \(f(X)\) is monotone in the treatment \(Z\left(X\right)\); ii) it has a threshold value \(c\), such that when f(X) > c, it implies that the treatment is more effective than control. In this work, we consider \(c=0.\) Therefore\(,\) the sign {f(X)} can be used to construct optimal ITRs and predict which of two treatments will have a better outcome. When sign {f (X)} >0\(,\) patients are assigned to treatment group. The importance of each biomarker can be assessed regarding its contribution to the predictive modeling of ITRs. To ensure the identifiability of ITRs, we make following two assumptions by using the standard strong ignorability condition24,25,26: {\(Y\left(1\right)-\), \(Y\left(-1\right)\)} \(\perp\) \({A|X}\) and 0 < P(A = 1|X) < 1 for all \(x\).

DeepRAB model

We introduce a DNN-based method for estimating ITRs and identifying predictive biomarkers. DeepRAB is a nonlinear model designed to capture \(Z(X)\) using biomarkers values as inputs and disease outcomes as output. DeepRAB consists of three main components. First, it incorporates the A-learning approach19 into the loss function to optimize ITRs. Second, it features a biomarker selection layer within the encoder layer, which compresses the input into a lower-dimensional representation and selects the biomarkers with the most impact on Y through \(Z(X).\) The third component is a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) known as the hidden layers within decoder layer. These layers model potentially non-linear effects of the covariates.

Let us set the pre-fixed number of \(k\) nodes in the biomarker selection layer, the output of encoder layer, denoted by z(1), can be expressed as z(1) = B(0),Tx, where z(1) ∈Rk and B(0) ≡[βk(0),…βk(0)] ∈Rp×k. Here, \({z}_{i}^{(1)}\)=βi(0),Tx = x1 \({\beta }_{i1}^{(0)}+\ldots +{x}_{p}{\beta }_{{ip}}^{(0)}\) for \(i=1,\ldots ,k\) represents the output of the ith node. Notably, this layer is used to select a user-specified set of k biomarkers that are deemed to be the most informative for predicting \(f(X)\). To accomplish this, we adopt the feature selection technique proposed in Balın et al18. which involves generating a \(p\)-dimensional vector \({\beta }_{i}^{(0)}\) using:

where \({\beta }_{{ij}}^{\left(0\right)}\) corresponds to the \({jth}\) element in \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{i}^{\left(0\right)}.\) The vectors α and g are p-dimensional and training parameters, and all elements of α are strictly greater than zero, while all elements of g are drawn from a Gumbel distribution27. The temperature parameter \(T\) takes on positive values. In this way, we obtain \({{\mathrm{lim}}}_{T\longrightarrow 0}{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{i}^{\left(0\right)}={[{\mathrm{0,0}},\ldots {\mathrm{1,0,0}},\ldots ,0]}^{{{\rm{T}}}}\) with probability \(P=\frac{{\alpha }_{j}}{{\sum}_{t}{\alpha }_{t}}.\). We sample a \(k\times p\) dimensional matrix \({B}^{0}\) for each of the k nodes in a similar manner. As a result, each node in the biomarker selection layer outputs one selected biomarker, resulting in a total of \(k\) selected biomarkers.

The decoder layers take z(1) as the input and are composed of \(h-1\) hidden layers, where \(h\) is tunning parameters. The expressions for the outputs of each hidden layer, denoted by \({{\boldsymbol{\ d}}}^{(j)},{{\rm{where}}}\) \(j=1,..,h-1,\) can be formulated as follows:

where nj \({{\rm{and}}}\) ϕj denotes the number of nodes and activation function in jth hidden layer, respectively. Then, we can write output f (\(x\)):

where ϕh is the activation function which typically a logistic function for binary outcomes and linear function for continues outcomes. The loss function of the model is defined as follows:

where \({{\boldsymbol{\theta}}} \equiv ({W}_{1\times {n}_{h}}^{\left(h\right)},\,\ldots ,\,{W}_{{n}_{1}\times k}^{\left(1\right)},\,{{\boldsymbol{\ b}}}_{1\times 1}^{\left(h\right)},\ldots ,{b}_{{n}_{1}\times 1}^{\left(1\right)},{{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}} ,{{\boldsymbol{g}}})\) represents the training parameters, and π(X)=P(A=1│X) is propensity score. The sign {\(f(\widetilde{\theta },X)\)} is used to construct optimal ITRs. Of note, the function \(M\)(\(u,v\)) varies depending on the outcome Y. In the original work by Chen19, \(M\left(y,v\right)\) is required to meet the following conditions: 1) \(M\left(y,v\right)\) is convex in \(v\) and 2) \(V\left(y\right):= M\left(y,0\right)\) is monotone in \(y\). These requirements are sufficient for Fisher consistent subgroup identification11,28. In this work, we select \(M\left(y,v\right)\) as follows: M(u, v)=(u–v)2 for continuous outcomes and \(M\)(\(u,v\))\(=u\log \left(1+\exp \left(-v\right)\right)\) for binary outcomes. It can be readily verified that these choices fulfill both the convexity in \(v\) and the monotonicity in \(y\) conditions. A visual representation of the DeepRAB is presented in Fig. 2.

a A schematic illustration of the DeepRAB architecture, which includes an input layer, a biomarker selection layer implemented via a CAE, multiple hidden layers, and an output layer corresponding to ITR predictions. This structure enables both subgroup identification and predictive biomarker discovery. b A mathematical overview of the biomarker selection layer. The selection process is driven by the CAE, enabling end-to-end learning of the most informative biomarkers for treatment response. The equations shown reflect how features are selected during model training. ITR: individualized treatment rule; CAE: Concrete Autoencoder.

Propensity scores

The propensity scores π(Xi) is nuisance parameter and unknown in observational studies. However, in randomized trials, the propensity scores are often known. The special case is that \(\pi \left({X}_{i}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\),\({{\rm{for}}}\) all i=1,…,n, when the samples are subjected to a 1:1 randomization ratio. In non-randomized trials, we employ logistic regression to the data (\(X,A\)) to estimate \(\pi \left({X}_{i}\right)\).

Simulation framework

We consider three simulation scenarios: one involving linear functions and two involving nonlinear functions, introducing greater complexity to the data. For each scenario, we assess performance using two sample sizes, \(N=1000\) and \(N=400\), with the smaller sample size reflecting conditions commonly encountered in real datasets.

Simulation scenario I

We first consider a linear simulation design to generate data for a continuous outcome using the following model:

where ϵ~N(0,1) represents error terms, and covariate vector \(X=({{X}_{1},{X}_{2},\ldots {X}_{10}})^{{{\rm{T}}}}\) is generated from a multivariate normal distribution with a mean of 0, variance of 2, and pairwise correlations of 0.2 between each biomarker. The treatment assignment variable \(A\) is drawn from a Bernoulli \(\left(0.5\right)\) distribution, with \(A=0\) indicating subjects in the control group and \(A=1\) indicating subjects in the treatment group. Under this setting, \(({X}_{5},\ldots ,{X}_{10})\) are considered as noisy biomarkers, while \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) are regarded as predictive biomarkers. On the other hand, biomarkers \({X}_{3}\) and \({X}_{4}\) are considered as prognostic biomarkers. The constants β0 and β are the strength of prognostic and predictive effects, respectively.

For binary outcomes, we simulate the response \({Y}_{i}^{b}(A)\) ∼ Bernoulli (plogis(Yi (A))), and \({Y}_{i}^{b}(A)\) can be expressed as:

where plogis\((x)=\frac{1\;+\;\tanh (x/2)}{2}\), and all other settings remained consistent with those used for continuous outcomes.

Simulation scenario II

In this scenario, we consider a simulation design with quadratic functions. The outcome

\(Y\) is simulated from a nonlinear model:

We simulate covariates X and error terms as in Simulation Scenario I, and the binary outcomes are simulated using the same method as in Simulation Scenario I.

Simulation scenario III

In this design, we incorporate interactive terms within the indicator function, adding more complexity to the simulation. To simulate data for a continuous outcome, we use the following model:

All other settings remain consistent with those used in Simulation Scenarios I and II.

Baseline models

We consider four baseline models in our analysis. The causal forest (CF) is a nonparametric model that extends the classic random forest algorithm to estimate conditional average treatment Effects. It is implemented via R package “grf”29. The XGBoost with modified loss function (XGboostML) model is an adaptation of the XGBoost algorithm that integrates the A-learning loss function. It is implemented via our published R package “BioPred”30. We also employ two linear regression models: linear regression with modified outcomes31 (LRMO) and linear regression with modified covariates32 (LRMC), both utilizing Lasso regularization33. Of note, LRMO is only designed for continuous outcomes, while LRMC is suitable for binary outcomes. Both linear regression models are implemented by R package “glmnet”34 with lasso penalty.

Evaluating the performance of models

In the simulation settings where the ground truth is known, we consider the true treatment benefiting group for patients with \(\{{i|}{Y}_{i}\left(1\right) > {Y}_{i}\left(0\right)\}\). Thus, an individual’s label is set to 1 if Yi(1)>Yi (0) and to 0 otherwise. When we assess the model’s performance in subgroup identification, we use evaluation metric of area under the ROC Curve (AUC) for classifying true subgroup labels. Concretely, our model produces a score \(\hat{f}\left(X\right)\) that reflects the likelihood of a patient belonging to the treatment-benefiting subgroup. By varying the threshold on \(\hat{f}\left(X\right)\), we obtain distinct pairs of true positive and false positive rates, forming an ROC curve. We then compute the AUC by integrating under this curve, in line with the evaluation strategies outlined in prior studies7,19. Since XGboostML also incorporates an A-learning function into its loss, it follows the same approach as DeepRAB for computing the AUC. For other subgroup identification methods, the output is an estimated treatment effect. To compute the AUC in a similar way, we vary the decision boundary (i.e., the cutoff on the estimated treatment effect) and record the corresponding true positive and false positive rates against the known subgroup labels, thereby producing an ROC curve and an associated AUC.

To evaluate the model’s efficacy in identifying individual biomarkers, we rank the importance of each selected biomarker for each method. Specifically, for the tree-based models, CF and XGboostML, we derive importance scores using the variable_importance() function in the grf package and the predictive_biomarker_imp() function in the BioPred package. In the case of LRMO and LRMC, we base each biomarker’s ranking on the absolute magnitude of its corresponding coefficient. We consider the top two ranking biomarkers as identified biomarkers. We define detection rate as the frequency of each biomarker being chosen as one of the top two important features across \(N\) replications. Moreover, when we examine the model’s ability in detecting interactive biomarkers in simulation settings, we consider the model successfully picks out the interactive biomarker when two true biomarkers are detected as top two ranked biomarkers simultaneously for each replication.

Statistics and reproducibility

To optimize the performance of the DeepRAB, we have experimented with various tuning parameters including the learning rate (\(\eta\)), the number of layers (\(h\)) in decode layer, the dropout rate \(\delta\), the activation function ϕj, and the number of nodes (\({n}_{i},i=1,\ldots ,h\)) in each layer.

Optimizing these parameters solely based on the training dataset often leads to overfitting, where the algorithm performs well on the data but fails to generalize to other datasets. This issue is particularly pronounced when working with clinical datasets, which typically have small sample sizes. Therefore, it is a common practice in many machine learning algorithms to select values of tuning parameters using an independent validation dataset. When a validation dataset is not available, as is often the case in smaller clinical trials, cross-validation methods are employed. To address the overfitting problem, we have divided the entire dataset into training and test sets in an 8:2 ratio. We advocate determining the tuning parameters via \(K\)-fold cross-validation (CV) on the training data, recommending \(K=10\) for practical applications. The test set is reserved for final model evaluation after the optimal tuning parameters have been selected. The procedure for deriving the optimal tuning parameters is as follows: First, the training dataset is randomly split into 10 folds. DeepRAB is then trained on \(K\)-1 folds using different combinations of tuning parameters, and the error (A-learning loss) is estimated on the left-out fold. We calculate the average estimated errors on the left-out folds for each combination of tuning parameters. The best tuning parameters are identified through a grid search based on the smallest average errors.

Once the optimal tuning parameters are determined, we first re-train the entire training set (using both \(X\) and \(Y\)) to identify the predictive biomarkers. Next, we input the biomarkers \(X\) of the testing dataset into the optimized DeepRAB model to predict subgroup labels. In the simulation study, where the ground truth is known, we evaluate model performance using the AUC for classifying true subgroup labels. This tuning process ensures that DeepRAB is well-calibrated and minimizes the risk of overfitting, thereby enhancing its applicability in clinical settings. The detailed cross-validation procedure is illustrated in Fig. 3. Specifically, the Adam optimizer is utilized, \(\eta\) is selected from the set {0.01, 0.05, 0.001, 0.005}, \(h\) is chosen from {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}, \({n}_{i}\) is selected from {4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128}, \(\delta\) is drawn from {0.2, 0.4, 0.6}, and \({\phi }_{j}\) is chosen from ReLU, Leaky ReLU, Sigmoid and Tanh. In addition, we set the pre-fixed number \(k\) equal to the number of covariates. Regarding the initialization of the temperature (\(T\)), we followed the approach proposed by Abid et al.18 to ensure effective exploration of different feature combinations and avoid convergence to suboptimal solutions. We initialize \(T\) as \(T(e)=\) \({T}_{1}({T}_{2}/{T}_{1})\)e/E, where T (e) represents the temperature at epoch number \(e\), and \(E\) denotes the total number of epochs used for training the model. T1 and T2 are tuning parameters, typically set to high and low values, respectively. All other baseline models, along with their associated hyper-parameters, are optimized using the same approach. Each simulation scenario is repeated 1000 times to ensure a robust and reliable evaluation of model performance.

This schematic outlines the model evaluation framework for DeepRAB using 10-fold cross-validation. The dataset is randomly divided into 10 equal parts; in each iteration, DeepRAB is trained on 9 folds while the remaining fold is used for validation. This process is repeated for all folds across a grid of tuning parameter combinations. The average validation error is computed for each parameter setting, and the optimal set of parameters is selected based on the lowest average validation error.

For the adalimumab dataset, the optimal tuning parameters for DeepRAB were determined as follows: the learning rate (\(\eta\)) was set to 0.001, with two hidden layers (\(h=2\)). The first hidden layer contained \({n}_{1}=\)16 nodes, and the second hidden layer contained \({n}_{2}=\)8 nodes. Leaky ReLU was used as the activation function for each hidden layer, and a dropout rate (\(\delta\)) of 0.2 was applied to prevent overfitting. Training was initiated with 10 to 100 epochs, and validation loss was continuously monitored. Early stopping was also implemented to prevent overfitting.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

DeepRAB overview

DeepRAB has the potential to uncover complex, non-linear relationships between patients’ characteristics and treatment outcomes, even when the signal of effect is weak, given that DNNs have been shown to successfully learn good representations of high-dimensional data in many tasks35. We build DeepRAB through several stages, as conceptualized in Fig. 4a. DeepRAB comprises an input layer, encoder layer, decoder layer, and output layer. The encoder layer performs the biomarker selection, while the decoder layer serves for data reconstruction.

a Overview of DeepRAB’s input features and output predictions, including interpretation of model components for subgroup identification and biomarker selection; b The observed data contains information about patient biomarkers \({X}_{i}\), factual treatment \({A}_{i}\) and factual outcome \({Y}_{i}\). The ground truth causal effect of the treatment is defined as the difference between receiving the treatment \({Y}_{i}(1)\) and placebo \({Y}_{i}(-1)\); c The observed data for patients that have received treatment (orange) and patients that have not received the treatment (green) can be used to learn response surfaces for each treatment option and thus estimate the causal effect of the treatment \(Z(X).\) d Implementation of A-learning loss function in output layer to estimate the optimal ITR; e Biomarker selection layer identifying predictive biomarkers and ranking their importance; f Treatment recommendation for the new patient based on sign \(\{\hat{f}\left(X\right)\}\).

For simplicity, for patient \(i\) with biomarkers \({X}_{i}\), received treatment assignment \({A}_{i}\) \(\in\){-1,1}, we observed outcome Yi. The Neyman-Rubin potential outcome framework21,22 allow us to define two potential outcomes for the patient: \({Y}_{i}(-1)\) and \({Y}_{i}(1)\) representing the patient’s outcomes when they have received a control (\({A}_{i}\) \(=\) \(-1\)) and treatment (\({A}_{i}\) \(=\)1) respectively. Then, we write factual patient outcome as \({Y}_{i}=\frac{1}{2}({1+A}_{i})\) \({Y}_{i}(1)+\frac{1}{2}({1-A}_{i}){Y}_{i}(-1)\) (Fig. 4b). Our proposed DeepRAB formulates the conditional expectation as \(E\left(Y|X,A\right)=Z\left(X\right)A+H\left(X\right),\) where \(Z\left(X\right)=\frac{1}{2}[E\left(Y|A=1,X\right)-E\left(Y|A=-1,X\right)]\) is a contrast function that reflects treatment effects given \(X\) and \(H\left(X\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left[E\left(Y|A=1,X\right)+E\left(Y|A=-1,X\right)\right]\) is a function that reflects the main covariate effect of \(X\). In identifying subgroups of patients who may benefit from A differently, we are interested in estimating \(Z\left(X\right)\) (Fig. 4c), as it reflects heterogenous treatment effect (THE). To optimize ITR, we employ the A-learning loss function19 to quantify the monotonic transformation of \(Z(X)\), denoted as \(f\left(X\right)\) (Fig. 4d).

The importance of biomarkers is measured within the biomarker selection layer through the utilization of CAE18 (Fig. 4e). On the other hand, the new treatments are recommended for patients based on the sign of {\(\hat{f}(X)\)} (Fig. 4f). In contrast to non-transparent DNN with limited interpretability of \(X\), our proposed method ranks variables in \(X\) based on their influence on \(Y\) via \(Z(X)\) without necessitating the estimation of \(H(X)\). As a result, DeepRAB only selects predictive biomarkers and remains unaffected by prognostic biomarkers. Another important feature of DeepRAB is its capability to capture any non-linear representations within \(Z\left(X\right)\) by leveraging the flexibility of DNNs to approximate continuous mappings.

Comparative performance of DeepRAB and competing methods in Simulations I and II

We initiate our analysis with Simulation Scenario I, as detailed in the Methods section. To assess the performance of each method under varying conditions of predictive and prognostic effect strength, we use a range of \(\beta\) values from the set {0.1, 0.5, 0.7, 1, 2, 3}. Three prognostic effect sizes \({\beta }_{0}\,\)= {0, 1, 2} are also considered. Our initial evaluations are conducted with a sample size of \(N=1000.\) Figure 5 illustrates the AUC results for subgroup classification in Scenario I for continuous outcomes. We observe that the performance of each method improved as \(\beta\) increased. Furthermore, the proposed DeepRAB method consistently outperforms competing methods across all conditions. Figure 6 depicts the detection rate for each biomarker. First, all methods demonstrate the ability to detect true biomarkers even in the presence of high inter-biomarker correlation. Our proposed model achieves the highest detection rate for \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) when the \(\beta =0.1\). In other scenarios, baseline methods attain a 100% detection rate for biomarkers \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\), while DeepRAB identifies \({X}_{1}\) with slightly lower accuracy. Similar results are observed with a smaller sample size of \(N=400\) in Supplementary Fig. 1–2. As expected, the power of all methods to correctly identify subgroups diminished with the decrease in sample size. Overall, the relative performance of the methods remains consistent with the larger sample size results. The results for binary outcomes with sample sizes of \(N=1000\) and \(N=400\) presented in Supplementary Fig. 3–6, showing consistent findings.

a Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=0\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). b Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=1\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). c Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=2\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). CF: causal forest. XGboostML: XGboost with modified loss function. LRMO: linear regression with modified outcome.

a Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=0\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). b Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=1\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). c Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=2\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). CF: causal forest. XGboostML: XGboost with modified loss function. LRMO: linear regression with modified outcome.

In Simulation Scenario II, we augment the complexity of the dataset from Simulation Scenario I by incorporating quadratic terms. Performance metrics for subgroup and biomarker identification are detailed in Supplementary Fig. 7–14, which cover both continuous and binary outcomes at sample sizes of \(N=1000\) and \(N=400\), respectively. As anticipated, both LRMO and LRMC perform poorly due to the inclusion of non-linear terms. Our results further show that the ability of CF to identify true subgroups decreases as the \({\beta }_{0}\) increases. In contrast, DeepRAB demonstrates relatively minimal sensitivity to increasing prognostic effects. For instance, while CF and DeepRAB achieve comparable AUCs for binary outcomes with \(N=1000\) when \({\beta }_{0}=0\) and \(\beta =3\), CF’s performance lags behind DeepRAB when \({\beta }_{0}=2\) and β=3. Interestingly, XGBoostML, CF, and LRMC incorrectly classify prognostic biomarkers \({X}_{3}\) and \({X}_{4}\) as predictive for binary outcomes when the prognostic effect is strong. In practical scenarios, biomarkers typically exhibit a degree of both prognostic and predictive value36. Misclassifying a biomarker as predictive when it primarily holds prognostic effects is strongly undesirable, as it can entail financial and ethical consequences37. Our findings highlight that DeepRAB is useful for predictive biomarker discovery in the presence of strong prognostic biomarkers.

Next, we assess the ability of each method to detect interactive biomarkers in Simulation Scenario II. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes the detection rates for each method in continues outcomes. Notably, DeepRAB outperforms competing methods in scenarios with weak predictive effects. For instance, DeepRAB achieves a high detection rate of 74.1% for interactions \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) at (β0, β)= (0, 0.1) with a sample size of \(N=400\), whereas other methods show lower detection rates. However, under strong predictive effects, CF and XGboostML outperform DeepRAB in some cases. Detection rates for interactive biomarkers in binary outcomes are presented in Supplementary Table S2, showing similar trends. In summary, DeepRAB demonstrates comparable performance to baseline models in Simulations I and II. Although other methods achieve higher detection rates in certain scenarios, these results suggest that there is no single perfect model.

DeepRAB outperforms competing methods in simulation III

In this section, we examine a more complex simulation scenario involving interactive terms within the indicator function. Supplementary Figs. 15–18 presents the subgroup and biomarker detection performance in continuous outcomes with sample sizes of \(N=1000\) and \(N=400\). It appears that the proposed DeepRAB method outperforms the competing methods in all cases. Remarkably, even in scenarios with weak predictive signals (β=0.1, 0.5, 0,7), DeepRAB attains the highest AUC. In contrast, baseline models demonstrate lower AUC values. In scenarios with strong predictive effects (\(\beta\) = 2, 3), DeepRAB performs comparably to CF while outperforming other methods. In addition, it is evident that LRMO demonstrates the poorest performance among the evaluated methods, as predicted, due to its incapacity to capture non-linear functions.

Biomarker identification results demonstrate that DeepRAB achieves highest detection rate for biomarkers (\({X}_{1}\), \({X}_{2}\)) in the presence of weak predictive signals. While alternative methods such as XGboostML and CF perform well in identifying these biomarkers when \(\beta\) = 2, 3, with detection rates comparable to DeepRAB, but struggle when predictive signals are weaker (\(\beta\) = 0.1, 0.5, 0.7). These results highlight the robustness of DeepRAB in identifying predictive biomarkers at weak treatment effects, further reinforcing our initial hypothesis. In addition, we note that DeepRAB’s performance remains stable even in the face of strong prognostic signal interference, etc., \({\beta }_{0}\,\)= 1 or 2, whereas other models demonstrate reduced efficacy.

We now extend our evaluation to binary outcomes with sample size of \(N=1000\). Our findings echo the trends observed in the continuous outcome case, with DeepRAB emerging as the top-performing model (Figs. 7, 8). For instance, DeepRAB achieves a median AUC of 0.79 at \(\left({\beta }_{0},\beta \right)\) = (0,1), slightly better than CF with a median AUC of 0.76, demonstrates superior performance compared to XGboostML and LRMC when predictive signal is strong. Moreover, we assess the models’ performance under weak predictive effects. In these cases, DeepRAB has the highest median of AUC and outperforms other methods by a large margin. DeepRAB performs better than other methods in the detection of biomarkers (\({X}_{1}\), \({X}_{2}\)) across all settings. Similar results for a sample size of \(N=400\) are presented in Supplementary Fig. 19–20. Collectively, our findings underscore the superior adaptability of DeepRAB, particularly under conditions characterized by weak predictive effects and correlative biomarkers, while also acknowledging the comparable performance of competing methodologies such as XGBoost and CF under specific conditions.

a Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=0\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). b Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=1\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). c Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=2\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). CF: causal forest. XGboostML: XGboost with modified loss function. LRMC: linear regression with modified covariates.

a Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=0\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). b Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=1\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). c Prognostic effect \({\beta }_{0}=2\); predictive effects \(\beta =\{{\mathrm{0.1,0.5,0.7,1,2,3}}\}\). CF: causal forest. XGboostML: XGboost with modified loss function. LRMC: linear regression with modified covariates.

Lastly, the detection rates of interactive biomarkers for each method are presented in Supplementary Table S3-S4. Our results show that DeepRAB emerges as the top performer, with the exception of certain scenarios, such as when \(\left({\beta }_{0},\beta \right)=({\mathrm{0,3}})\) for binary outcomes with sample sizes of \(N=400\) and \(N=1000\), where CF achieves the highest detection rate. These findings suggest that DeepRAB is a promising tool for identifying interactions in complex data settings. Notably, all methods, except DeepRAB, exhibit difficulty in detecting non-linear interactions under weak predictive effect (\(\beta =0.1\)).

Null scenarios

To assess the model performance in null scenarios where no predictive biomarkers exist (β = 0), we have evaluated the AUC for subgroup identification across three simulation settings (I-III) for both continuous and binary outcomes with N = 1000. Specifically, we have created a ground truth by labeling a sample as positive (labeli=1) if Yi (1) > Yi (0) and negative labeli=0 otherwise. Both Yi (1) and Yi (0) include the same prognostic term plus independent \(N\left({\mathrm{0,1}}\right)\) \({{\rm{noise}}}\), \({{\rm{making}}}\) \(\Delta Y={Y}_{i}\left(1\right)-{Y}_{i}\left(0\right)\) is purely random. These results are detailed in Supplementary Fig. 21–23. Consistent with expectations, the subgroups identified by all methods resembled random selections, with each method achieving an average AUC of approximately 50%. This result confirms the hypothesis that, in the absence of true predictive effects, subgroup classification is equivalent to random chance.

Detection rates for identifying biomarkers are presented in Supplementary Fig. 24–26. When \(({\beta }_{0},\beta )=\left({\mathrm{0,0}}\right),\) all models exhibit similar detection rates for biomarkers, approximately 20%. For continuous outcomes, despite varying prognostic effects \(({\beta }_{0}={\mathrm{1,2}})\), the detection rates for all models remain near the theoretical threshold of 20%, reflecting the inclusion of 10 covariates and indicating that all models effectively guard against overfitting in scenarios without true predictive effects.

However, in the case of binary outcomes, methods such as CF and XGboostML show a higher detection rate for prognostic biomarkers \({{{\rm{X}}}}_{3}\) and \({{{\rm{X}}}}_{4}\) when the prognostic effect is strong. This result is unexpected, as these models are designed to detect predictive, rather than prognostic, biomarkers. Taken together, the results indicate that the selection rate for all biomarkers, including non-informative ones, remains approximately equal, suggesting that DeepRAB does not favor any particular biomarker in the absence of an underlying signal. This pattern reflects random feature selection under the null scenarios. The results for \(N=400\) show a similar pattern.

DeepRAB identifies predictive biomarkers associated with the heterogeneous treatment effect of Humira

Two double-blind, placebo-controlled pivotal studies, PIONEER I and II, similar in design and in enrollment criteria4,5, are conducted to evaluate the treatment effect of adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) for patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS), a painful, chronic inflammatory skin disease. Both studies are powered for the primary endpoint at the end of the initial 12-week double-blind period (Period A), which is the HiSCR38, defined as a reduction of ≥50% in inflammatory lesion count (sum of abscesses and inflammatory nodules, referred as AN count), and no increase in abscesses or draining fistulas when compared to baseline. The results of the two clinical trials shows significant treatment effect of adalimumab for HS patients and were published in Kimball et al. Specifically, clinical response rates at week 12 are significantly higher for patients receiving adalimumab weekly than for patients receiving placebo: 41.8% versus 26.0% in PIONEER I (P = 0.003) and 58.9% versus 27.6% in PIONEER II (P < 0.001). Per agreement with FDA, a subsequent 24-week randomized withdrawal period (Period B) is included in each study for exploratory purposes. Since HS is a chronic disease, the main objective of this period is to evaluate the long-term benefit of adalimumab to guide physicians and patients in managing HS beyond 12 weeks. We applied DeepRAB on responded patients who were re-randomized to either continuation of adalimumab weekly dosing or withdrawal from adalimumab (placebo) in period B after initial treatment of adalimumab weekly dosing for 12 weeks (Fig. 1, yellow shaded boxes in period B) to identify biomarkers for patients who can benefit from continued adalimumab treatment the most.

Given that the true nature of subgroup is unknown in real data applications, our primary goal is to identify predictive biomarkers that discern the most clinically appropriate patient groups for ongoing weekly dosing of adalimumab versus discontinuation. Secondly, our study involves a cohort of 199 patients, we have utilized our proposed CV technique across the entire dataset to address the limitations posed by the small sample size. The optimal tuning parameters used in the analysis are provided in the Methods section. Figure 9 shows the result of identified predictive biomarkers that can predict HS treatment benefit using four distinct methods. DeepRAB pinpoints the top two biomarkers: CHG_AN and AN12. Conversely, CF recognizes CHG_AN and AN0 as key biomarkers, whereas XGBoost highlights DFT_OBS_0 along with CHG_AN. LRMC identifies ITT2RFN and HISCR0 as the principal biomarkers. Remarkably, CHG_AN is consistently selected by DeepRAB, CF, and XGBoost among their top biomarkers, underscoring its potential relevance in assessing the benefits of continued adalimumab therapy. This finding aligns with prior studies6,7, which further validate CHG_AN as a key biomarker in this context. In contrast, LRMC fails to identify this well-validated biomarker. Furthermore, both DeepRAB and XGBoost recognize AN0 among their top ranked biomarkers, placing it in the top three and five positions respectively, highlighting its potential importance alongside CHG_AN. This result indicates that AN0 merits further investigation.

a DeepRAB. b XGboostML. c CF. d LRMC. XGboostML: XGboost with modified loss function; CF: causal forest; LRMC: linear regression with modified covariates; CHG_AN: % reduction in AN count at week 12; AN12: AN count at week 12; AN0: AN count at week 0; DFT_OBS_0: draining fistula count at week 0; DFT_OBS_12: draining fistula count at week 12; CHG_DFT_OBS: reduction in draining fistula count at week 12; ABT_OBS_0: abscess count at week 0; ABT_OBS_12: abscess count at week 12; CHG_ABT_OBS: reduction in abscess count at week 12; SMOKER: smoking status; STHUSTN: Hurley stage at week 0; ITT2RFN: initial responder status at week 12; HISCR0: HiSCR at week 0; STANHSN: concomitant use of antibiotics.

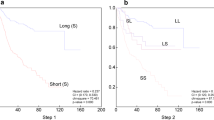

In the post-hoc subgroup analysis, we have employed Sequential-Batting (Seq-Batting)39 method to derive the signature of CHG_AN. Specifically, subjects are classified as subgroup-positive if the identified biomarker met the Seq-Batting threshold, and subgroup-negative otherwise. The overall HiSCR rates have been previously reported40. The proportion of patients achieving HiSCR by visit is reported in Supplementary Fig. 27. The identified signature-positive subgroup comprised of patients achieving at least 25% reduction in ANcount ( ≥ AN25) after the initial 12 weeks of treatment, named PRR population (partial responders and HiSCR responders). The subgroup results are presented in Fig. 10 are consistent with previously published regulatory documents. For example, the European Medicines Agency Summary of Product Characteristics (EMA SmPC) reports that among patients showing at least a partial response to weekly 40 mg adalimumab at Week 12, those who continued weekly dosing had a higher HiSCR rate at Week 36 compared to those who reduced to every-other-week dosing or discontinued treatment. Similarly, the Canada Product Monograph indicates that in patients achieving at least a 25% improvement in AN count at Week 12, HiSCR response rates at Week 24 were 57.1% for weekly dosing, 51.4% for every-other-week dosing, and 32.9% for placebo. At Week 36, the respective rates were 55.7%, 40.0%, and 30.1%.

a Proportion of patients in the PRR population achieving HiSCR at each study visit. b Proportion of patients in the NonPRR population achieving HiSCR at each study visit. PRR (Partial Responders and HiSCR Responders) are defined as patients with at least a 25% reduction in abscess and inflammatory nodule (AN) count after the initial 12 weeks of treatment; NonPRR includes all other patients.

Discussion

The identification of subgroups and predictive biomarkers plays an important role in shaping clinical decision-making processes. Traditional deep learning models examine the relationship between disease outcomes and patients’ characteristics without inherent feature selection capabilities. Although it is theoretically possible to build a DNN-based model for subgroup identification by incorporating Meta-learners, these approaches face several limitations. These methods encounter challenges regarding the interpretability of covariates, limiting their capability for feature selection. Moreover, their indirect execution of subgroup identification restricts concurrent biomarker and subgroup identification processes.

Our proposed DeepRAB model addresses this gap by being one of the first to concurrently perform subgroup identification and predictive biomarker selection. Although baseline comparisons are made against established subgroup analysis methods, there are currently no deep learning models that specifically tackle this dual task. Future research will include comparisons with state-of-the-art deep learning models as they become available.

When exercising predictive biomarkers identifications, no single method is universally optimal. We recommend applying a range of models to any given dataset, allowing for a more comprehensive analysis. Results can then be synthesized using a consensus approach, such as majority voting across models. While XGboostML and LRMC showed limitations in some simulations, additional analyses demonstrated that these models perform well under specific conditions. This indicates the importance of using multiple models to uncover robust biomarkers in real-world applications, where diverse methodologies can provide complementary insights. For instance, the consistent identification of CHG_AN by DeepRAB, CF, and XGboostML supports its relevance as a key biomarker for adalimumab therapy. In our simulations, we select the top two ranked biomarkers for each method, in line with the known relevance of exactly two biomarkers. However, in clinical practice, simply choosing a fixed number of features may be insufficient. Instead, it is crucial to collaborate closely with medical experts, cross-check findings against prior research, assess reproducibility using other methods, and ensure alignment with regulatory documents. These steps are essential to validate whether the identified biomarkers hold genuine clinical relevance.

In our adalimumab data analysis, preliminary exploratory steps such as correlation assessments (Supplementary Fig. 28) highlight that clinical covariates are considerably more complex than simulation-based models might indicate. Additionally, because no true subgroup labels or independent validation datasets are available (unlike in theoretical simulations), careful cross-validation is essential for ensuring the robustness of identified biomarkers across multiple algorithms. To address the constraints imposed by a small sample size, we applied our proposed CV approach to the entire dataset. Notably, our model successfully uncovers clinically meaningful biomarkers and corresponding subgroups that concur with regulatory documentation from the EMA SmPC and the Canada Product Monograph.

Given the exploratory nature of retrospective subgroup identification, careful interpretation of the results is required, particularly when considering regulatory approval or changes to clinical practice41. Successful subgroup identification, therefore, necessitates cross-disciplinary collaboration from trial design through to interactions with regulatory authorities. For instance, the study design must accommodate subgroup identification. In the case of HS example, consideration of natural disease fluctuation and the unknown response time course led to a clinical development program that deviated from the traditional randomized withdrawal trial design. Instead of re-randomizing only initial HiSCR responders, all patients entering Period B are re-randomized, enabling subgroup identification. Furthermore, independent validation using a dataset with a similar and appropriate design would be ideal for confirming these identified biomarkers and related subgroups. Finally, gaining support from regulatory agencies, payers, and clinicians often requires evidence beyond statistical modeling. The candidate biomarkers used in algorithms must be clinically relevant; the subgroup signature should be biologically plausible and easily identifiable by clinicians or patients. The success of the Humira HS example is also driven by the unmet medical need and impact of adalimumab treatment on patient outcomes.

Our DeepRAB method may hold promising potential for extension into neuroimaging modalities such as MRI, CT, and PET scans. Deep learning techniques have been successfully applied across diverse biomedical domains, including disease outcome prediction using MRI and PET, demonstrating their ability to handle the high dimensionality and complex patterns of imaging data42,43. While these results are encouraging, extending DeepRAB to imaging biomarkers would require incorporating layers designed to capture spatial hierarchies and patterns, such as convolutional layers commonly used in image-based models. We recognize that further development will be necessary to adapt DeepRAB for imaging data, and this represents an important direction for future work. Moreover, an extended application of the CAE in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) is explored14, motivating us to consider adapting similar techniques to apply DeepRAB to large-scale omics datasets. This adaptation could facilitate the identification of predictive genetic or proteomics biomarkers. Furthermore, recent studies indicate that domain randomization, in which variations in color, texture, lighting, and other factors are introduced during simulation, can train neural networks on simulated images that transfer to real images44. Adopting a similar strategy may help DeepRAB bridge the gap between simulated data and real-world clinical settings. Finally, future research could explore extending DeepRAB to accommodate time-to-event outcomes by adjusting the function \(M(u,v)\) to Cox proportional hazards loss function45.

It is essential to acknowledge certain limitations of DeepRAB. Firstly, in specific instances, DeepRAB might require more computational time compared to alternative methods, despite demonstrating superior performance based on empirical evidence. DeepRAB’s complexity, defined by factors such as the number of layers, nodes per layer, and learning rate, makes it more parameter-intensive than traditional models like LRMC or CF. However, this added complexity enables DeepRAB to capture non-linear relationships and intricate feature dependencies, offering a distinct advantage in handling complex data structures. Secondly, ongoing research efforts should focus on conducting further investigations into the identified biomarkers associated with adalimumab treatment. These endeavors are essential to ascertain the generalizability of DeepRAB across diverse clinical scenarios.

Overall, our research provides a promising approach for subgroup identification and predictive biomarker discovery by leveraging deep learning. Our application to HS clinical trial data demonstrates the method’s potential utility in real-world clinical research. By supporting more targeted treatment strategies, our approach may contribute to improved decision-making in personalized medicine.

Data availability

Company proprietary data used in this work was obtained from the following clinical trials (PIONEER I and PIONEER II with ClinicalTrials.gov numbers NCT01468207 and NCT01468233, respectively) is not available to share. The source data underlying Figs. 5–8, S1–S26, and Tables S1–S4 are available via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1549166546. For any questions or further inquiries regarding the data, readers are encouraged to contact the corresponding author.

Code availability

The code supporting the findings of this study are available at GitHub: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1549166546 For any questions or further inquiries regarding the code, readers are encouraged to contact the corresponding author.

References

Revuz, J. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 23, 985–998 (2009).

Jemec, G. B. Hidradenitis suppurativa. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 158–164 (2012).

Shlyankevich, J., Chen, A. J., Kim, G. E. & Kimball, A. B. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a systemic disease with substantial comorbidity burden: a chart-verified case-control analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 71, 1144–1150 (2014).

Kimball, A. B. et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 422–434 (2016).

Kimball, A. et al. HiSCR (Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response): a novel clinical endpoint to evaluate therapeutic outcomes in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from the placebo‐controlled portion of a phase 2 adalimumab study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 30, 989–994 (2016).

Huang, X., Li, H., Gu, Y. & Chan, I. S. Predictive biomarker identification for biopharmaceutical development. Stat. Biopharmaceutical Res. 13, 239–247 (2021).

Huang, X., Tian, L., Sun, Y., Chatterjee, S. & Devanarayan, V. Predictive signature development based on maximizing the area between receiver operating characteristic curves. Stat. Med. 41, 5242–5257 (2022).

Loh, W. Y., Cao, L. & Zhou, P. Subgroup identification for precision medicine: a comparative review of 13 methods. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 9, e1326 (2019).

Künzel, S. R., Sekhon, J. S., Bickel, P. J. & Yu, B. Metalearners for estimating heterogeneous treatment effects using machine learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 4156–4165 (2019).

Moodie, E. E., Chakraborty, B. & Kramer, M. S. Q‐learning for estimating optimal dynamic treatment rules from observational data. Can. J. Stat. 40, 629–645 (2012).

Qian, M. & Murphy, S. A. Performance guarantees for individualized treatment rules. Ann. Stat. 39, 1180 (2011).

Qi, Z., Liu, D., Fu, H. & Liu, Y. Multi-armed angle-based direct learning for estimating optimal individualized treatment rules with various outcomes. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 115, 678–691 (2020).

Eraslan, G., Avsec, Ž., Gagneur, J. & Theis, F. J. Deep learning: new computational modelling techniques for genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 389–403 (2019).

Liu, Z., Dai, W., Wang, S., Yao, Y. & Zhang, H. Deep learning identified genetic variants for COVID‐19‐related mortality among 28,097 affected cases in UK Biobank. Genet. Epidemiol. 47, 215–230 (2023).

Xiong, H. Y. et al. The human splicing code reveals new insights into the genetic determinants of disease. Science 347, 1254806 (2015).

Schwab P, Linhardt L, Bauer S, Buhmann JM, Karlen W. Learning counterfactual representations for estimating individual dose-response curves. In: Proc. the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence) (2020).

Falet, J.-P. R. et al. Estimating individual treatment effect on disability progression in multiple sclerosis using deep learning. Nat. Commun. 13, 5645 (2022).

Balın MF, Abid A, Zou J. Concrete autoencoders: Differentiable feature selection and reconstruction. In: International conference on machine learning). PMLR (2019).

Chen, S., Tian, L., Cai, T. & Yu, M. A general statistical framework for subgroup identification and comparative treatment scoring. Biometrics 73, 1199–1209 (2017).

Lu, W., Zhang, H. H. & Zeng, D. Variable selection for optimal treatment decision. Stat. methods Med. Res. 22, 493–504 (2013).

Rubin, D. B. Causal inference using potential outcomes: Design, modeling, decisions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 100, 322–331 (2005).

Rubin, D. B. Bayesian inference for causal effects: the role of randomization. Annals stat. 6, 34–58 (1978).

Huling, J. D. & Yu, M. Subgroup identification using the personalized package. J. Stat. Softw. 98, 1–60 (2021).

Imbens, G. W. & Wooldridge, J. M. Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. J. economic Lit. 47, 5–86 (2009).

Pearl J. Detecting latent heterogeneity. In: Probabilistic and Causal Inference: The Works of Judea Pearl) (2022).

Rolling CA. Estimation of Conditional Average Treatment Effects.). University of Minnesota (2014).

Gumbel EJ. Statistical theory of extreme values and some practical applications: a series of lectures. US Government Printing Office (1948).

Zhao, Y., Zeng, D., Rush, A. J. & Kosorok, M. R. Estimating individualized treatment rules using outcome weighted learning. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 107, 1106–1118 (2012).

Wager, S. & Athey, S. Estimation and inference of heterogeneous treatment effects using random forests. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 113, 1228–1242 (2018).

Liu, Z., Sun, Y. & Huang, X. BioPred: an R package for biomarkers analysis in precision medicine. Bioinformatics 40, btae592 (2024).

Hitsch GJ, Misra S. Heterogeneous treatment effects and optimal targeting policy evaluation. Available at SSRN 3111957, (2018).

Tian, L., Alizadeh, A. A., Gentles, A. J. & Tibshirani, R. A simple method for estimating interactions between a treatment and a large number of covariates. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 109, 1517–1532 (2014).

Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B: Stat. Methodol. 58, 267–288 (1996).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1 (2010).

Bengio, Y., Courville, A. & Vincent, P. Representation learning: a review and new perspectives. IEEE Trans. pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35, 1798–1828 (2013).

Ballman, K. V. Biomarker: predictive or prognostic? J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 33, 3968–3971 (2015).

Sechidis, K. et al. Distinguishing prognostic and predictive biomarkers: an information theoretic approach. Bioinformatics 34, 3365–3376 (2018).

Kimball, A. B. et al. HiSCR (Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response): a novel clinical endpoint to evaluate therapeutic outcomes in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from the placebo-controlled portion of a phase 2 adalimumab study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol Venereol. 30, 989–994 (2016).

Huang, X. et al. Patient subgroup identification for clinical drug development. Stat. Med. 36, 1414–1428 (2017).

Gulliver W, et al. Therapeutic response guided dosing strategy to optimize long-term adalimumab treatment in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: integrated results from the PIONEER phase 3 trials. In: Journal of the American Academy Of Dermatology). MOSBY-ELSEVIER 360 PARK AVENUE SOUTH, NEW YORK, NY 10010−11710 USA (2017).

Simon, R. M., Paik, S. & Hayes, D. F. Use of archived specimens in evaluation of prognostic and predictive biomarkers. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 101, 1446–1452 (2009).

Noor MBT, Zenia NZ, Kaiser MS, Mahmud M, Al Mamun S. Detecting neurodegenerative disease from MRI: a brief review on a deep learning perspective. In: Brain Informatics: 12th International Conference, BI 2019, Haikou, China, December 13–15, 2019, Proceedings 12). Springer (2019).

Domingues, I. et al. Using deep learning techniques in medical imaging: a systematic review of applications on CT and PET. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 4093–4160 (2020).

Tobin J, et al. Domain randomization for transferring deep neural networks from simulation to the real world. In: 2017 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS)). IEEE (2017).

Harrell J, Frank E, Harrell FE. Cox proportional hazards regression model. Regression modeling strategies: With applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis, 475–519 (2015).

Liu, Z. Simulation code and data for “Deep learning-based ranking method for subgroup and predictive biomarker identification in patients”. Zenodo (2025).

Acknowledgements

This article is sponsored by AbbVie. AbbVie contributed to the design, research, and interpretation of data, writing reviewing, and approving the content. Zihuan Liu, Yihua Gu and Xin Huang are employees of AbbVie Inc. All authors may own AbbVie stock. We thank AbbVie for Research Computing for guidance and use of the research computing infrastructure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zihuan Liu, Yihua Gu and Xin Huang conceived and oversaw this project. Zihuan Liu took the main responsibility for the execution of this project. Zihuan Liu, Yihua Gu and Xin Huang contributed to the data analysis. All authors made critical input to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Yuzhen Ding, Furui Liu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Gu, Y. & Huang, X. Deep learning-based ranking method for subgroup and predictive biomarker identification in patients. Commun Med 5, 221 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00946-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00946-z