Abstract

Background

Real-world medical environments such as oncology are highly dynamic due to rapid changes in medical practice, technologies, and patient characteristics. This variability, if not addressed, can result in data shifts with potentially poor model performance. Presently, there are few easy-to-implement, model-agnostic diagnostic frameworks to vet machine learning models for future applicability and temporal consistency.

Methods

We extracted clinical data from EHR for a cohort of over 24,000 patients who received antineoplastic therapy within a distinct year. The label of this study are acute care utilization (ACU) events, i.e., emergency department visits and hospitalizations, within 180 days of treatment initiation. Our cross-sectional data spans treatment initiation points from 2010–2022. We implemented three models within our validation framework: Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), Random Forest (RF), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost).

Results

Here, we introduce a model-agnostic diagnostic framework to validate clinical machine learning models on time-stamped data, consisting of four stages. First, the framework evaluates performance by partitioning data from multiple years into training and validation cohorts. Second, it characterizes the temporal evolution of patient outcomes and characteristics. Third, model longevity and trade-offs between data quantity and recency are explored. Finally, feature importance and data valuation algorithms are applied for feature reduction and data quality assessment. When applied to predicting ACU in cancer patients, the framework highlights fluctuations in features, labels, and data values over time.

Conclusions

The work in this study emphasizes the importance of data timeliness and relevance. The results on ACU in cancer patients show moderate signs of drift and corroborate the relevance of temporal considerations when validating machine learning models for deployment at the point of care.

Plain language summary

With the growing use of routinely collected clinical data, computational models are increasingly used to predict patient outcomes with the aim to improve care. However, changes in medical practices, technologies, and patient characteristics can lead to variability in the clinical data that is collected, reducing the accuracy of the results obtained when applying the computational model. We developed a framework to systematically evaluate clinical machine learning models over time that assesses how clinical data and computational model performance evolve, ensuring safety and reliability. We used our model on people with cancer undergoing chemotherapy and were able to predict emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Implementing frameworks such as ours should enable the accuracy of computational models to be assessed over time, maintaining their ability to predict outcomes and improve care for patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHR) offers a rich, longitudinal resource for developing machine learning (ML) models to improve healthcare delivery and patient outcomes1. Clinical ML models are increasingly trained on datasets that span many years2. This holds promise for accurately predicting complex patient trajectories and long-term outcomes, but it necessitates discerning relevant data given current practices and care standards.

A fundamental principle in data science is that the performance of a model is influenced not only by the volume of data but crucially by its relevance. Particularly in non-stationary real-world environments, more data does not necessarily result in better performance3. Selecting the most relevant data, however, often requires careful cohort scoping, feature reduction, and knowledge of how data and practices evolve over time in specific domains. This is further complicated by temporal variability, i.e., fluctuations of data quality and relevance for current-day clinical predictions, which is a critical concern for machine learning in highly dynamic environments4,5.

Clinical pathways in oncology evolve rapidly, influenced by factors such as emerging therapies, integration of new data modalities, and disease classification updates (e.g., in the AJCC Cancer Staging System)6,7,8. This leads to i) natural drift in features, because therapies previously considered standard of care become obsolete; and ii) drift in clinical outcomes, e.g., because new therapies might reduce the number of certain adverse events (AE) like hospitalizations due to anemia, while giving rise to autoimmune-related AEs4,5,9,10,11. These shifts in features, patient outcomes, and their joint distribution are often amplified at scale by EHR systems. For example, the introduction of new diagnostic tests and therapies frequently necessitates updated data representations, coding practices (e.g., due to billing and insurance policies), or data storage systems12,13. This is exemplified by the switch of ICD-9 to ICD-10 as coding standard in 2015, leading to a series of model (re)validation studies14,15,16. Finally, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to care disruption and delayed cancer incidence, is a primary example for why temporal data drifts follow not only gradual, incremental, and periodic/seasonal patterns, but can be sudden12,17.

Together, these temporal distribution shifts, often summarized under ‘dataset shift’18, arise as a critical concern for the deployment of clinical ML models whose robustness depends on the settings and data distribution on which they are originally trained4. This raises the question about which validation strategies ensure that models are thoroughly vetted for future applicability and temporal consistency, ensuring their safety and robustness.

In the literature, it is increasingly recognized that training a model once before deployment is not sufficient to ensure model robustness, requiring local validation and retraining strategies19,20,21. Existing frameworks, therefore, frequently focus on drift detection post deployment21,22. Other strategies integrate domain generalization and data adaptation strategies to enhance temporal robustness23. There is a rising number of tools that harness visualization techniques to understand the temporal evolution of features24. However, there is a lack of comprehensive, user-friendly, frameworks that look at the dynamic progression of features and labels over time, analyze data quantity-recency trade-offs, and seamlessly integrate feature reduction and data valuation algorithms for prospective validation—elements that are most impactful when combined synergistically.

This study introduces a model-agnostic diagnostic framework designed for temporal and local validation. Our framework encompasses four domains, each shedding light on different facets of temporal model performance. We systematically implement each element of this framework by applying it to a cohort of cancer patients under systemic antineoplastic therapy. Throughout this study, the framework enables identifying various temporally related performance issues. The insights gained from each analysis provide concrete steps to enhance the stability and applicability of ML models in complex and evolving real-world environments like clinical oncology.

Methods

Study design and population

This retrospective study identifies patients from a comprehensive cancer center at Stanford Health Care Alliance (SHA) using EHR data from January 2010 to December 2022. SHA is an integrated health system, which includes an academic hospital (Stanford Health Care [SHC]), a community hospital (ValleyCare Hospital [ValleyCare]), and a community practice network (University Healthcare Alliance [UHA]). The study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. This study involved secondary analysis of existing data, and no human subjects were recruited; therefore, the research was deemed exempt from requiring informed consent (Protocol #47644).

The unit of analysis of this cohort study is individual patients. We construct a dataset using dense, i.e., highly detailed, and high-dimensional, electronic health records (EHR, Epic System Corp) from a comprehensive cancer center. Eligible patients were diagnosed with a solid cancer disease, and received systemic antineoplastic therapy, i.e., immuno-, targeted, endocrine and/or cytotoxic chemotherapy, between January 1, 2010, to June 30, 2022. We excluded patients who were below the age of 18 on the first day of therapy, were diagnosed with a cancer disease externally, or had a hematologic or unknown cancer disease.

Time stamps and features

Each patient record had a timestamp (index date) corresponding to the first day of systemic therapy. This date was determined using medication codes and validated using the local cancer registry (gold standard). The feature set was constructed using demographic information, smoking history, medications, vitals, laboratory results, diagnosis and procedure codes, and systemic treatment regimen information. To standardize feature extraction, we used EHR data solely from the 180 days preceding the initiation of systemic therapy (index date) and used the most recent value recorded for each feature. This provides an efficient, straightforward approach with minimal assumptions, while allowing balanced patient representation since patients with longer and more complex medical history are more accurately represented in EHR systems. We included the 100 most common diagnosis and medication codes, as well as the 200 most prevalent procedure codes from each year. All categorical variables in the feature matrix were one-hot encoded, indicating whether a specific demographic information, tumor type, procedure, diagnosis code, medication type etc. was applied or administered in the past 180 days. This approach produced a feature matrix where each row represents a single patient. If multiple records for a feature existed, the last value was carried forward (LVCF) or, if a value was missing fully for 180 days, imputed using the sample mean from the training set. We further implemented a k-nearest neighbor-based (KNN) imputation approach for k = 5, 15, 100, 1000, which was fit on the training data and applied to both the training and the test data.

Labels and censoring

The labels for this study are binary. Positive labels (y = 1) were assigned if two criteria were met. First, an acute care event (ACU), meaning emergency department visit or hospitalization, occurred between day 1 and day 180 following the index date. We disregarded events on day 0 (index date) to avoid contamination from in-patient therapy initiations. Second, the ACU event was associated with at least one symptom/diagnosis as defined by CMS’ standardized list of OP-35 criteria for ACU in cancer patients25. To ensure this window was set correctly, the index date was compared against the therapy start date in the local tumor registry (gold standard) and observations were removed if the start date in the EHR deviated more than 30 days from the start date in the registry. To address censoring and identify patients treated elsewhere (i.e., presenting only for second opinion), patients were only included if they (i) had at least five encounters in the two years preceding the index date (no left-censoring), and (ii) had at least 6 encounters under therapy, i.e., in the 180 days following the index date.

Model training and evaluation

For each experiment, the patient cohort was split into one or multiple training and test sets. Hyperparameters were optimized using nested, 10-fold cross-validation within the training set. The hyperparameters from the model with the best performance were then used to refit the model on the entire training set. The model’s performance was evaluated on two separate independent test sets; one emanated from the same time period (internal validation) as the training data (90:10 split), and the other originated from subsequent years, constituting a prospective independent validation set. To guarantee balanced representation of each year in the sliding window as well as retrospective incremental learning experiments, i.e., set-ups in which models are trained on moving blocks of years (see below), we sampled a fixed number (n = 1000) of training samples from each year. For all remaining experiments, the data within the training and test sets were utilized in their entirety, without any sampling, encompassing the full scope of data for the selected time period. To ensure universality of the framework, model performance was evaluated using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC), with 95%-bootstrapped confidence intervals (CI).

Model selection and diagnostic framework

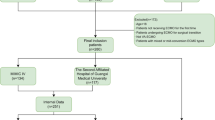

Our framework consists of four steps (Fig. 1), each addressing a distinct issue related to temporal/local validation. The first experiment performs a single split on the data to divide the longitudinal dataset into a ‘retrospective’ training and ‘prospective’ validation cohort. We trained three machine learning models suitable for predicting acute care events in settings with a sparse feature matrix: logistic Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO)26, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)27, and Random Forest (RF)28. Based on this experiment, we select the model with the highest AUROC and short run time for use in subsequent experiments.

The figure shows the framework for prospective and local validation and success metrics for different stages. The model-agnostic framework (a) depicts a sequence of experiments that researchers and practitioners can follow to validate a prediction model prospectively before clinical deployment. Each part addresses a separate analysis, including 1. assessment of model performance upon splitting time-stamped data into retrospective training and prospective validation cohorts; 2. temporal evolution of patient outcomes and patient characteristics, ranked by feature importance; 3. longevity of model performance and assessment of trade-offs between the quantity of training data and its recency; and 4. estimated impact of feature reduction and algorithmic data selection strategies. The presence of red flags (b) highlights potential risks/failure modes. Each red flag warrants further investigation and potential application-specific mitigation.

The second experiment (Fig. 1, Evolution of Features and Labels over Time), examines trends in the incidence of systemic therapy initiations and acute care events (labels), stratified by event type in each month. The third experiment (Fig. 1, Sliding Window, Model Longevity, and Progression Analysis) interrogates performance longevity/robustness as well data quantity-recency trade-offs. This is achieved through two sub-experiments. First, the model is trained on a moving three-year time window, and its performance is then analyzed as the temporal gap (between the last time stamp in the train set and the first time stamp in the test set) widens. Second, we perform a progression analysis that emulates the real-world implementation of the model: the model is implemented from the outset, and its performance is shown both without retraining and with annual retraining using the cumulative data available up to each year.

The final experiment (Fig. 1, Temporally Validated Feature Selection and Data Valuation) estimates the impact of strategies to select features and training samples most valuable for creating a temporally robust model.

Shapley values and feature reduction

To inspect the evolution of features most important to the model’s predictions over time, we calculated Shapley values using ‘TreeExplainer’ from the Python package ‘SHAP’29. For feature reduction in the final part of the framework, we used scikit-learn to calculate the importance of each feature (to identify the features most important to the model’s performance). Models were trained on data from 2010 to 2020 and tested on data from 2021, and permutations were repeated 50 times. We then removed features with negative permutation importance due to their putative negative impact on performance. Feature removal was halted once the features had an importance value of 0. We finally used a second held-out test set from 2022 to evaluate performance on a future test set.

Data valuation and elimination

For the data valuation and reduction, we used a Random Forest classifier and data valuation algorithms implemented in the Python package ‘OpenDataVal’30. First, the following algorithms were compared using recursive datum elimination (RDE): KNNShapley 31, Data-Oob32, Data Banzhaf33, and Leave-One-Out (control). We employed proportional sampling from each class (with and without ACU event) when removing datapoints, as changes in the class (im)balance commonly affect model performance34. We subsequently used the best-performing algorithms from the point-removal experiments to calculate the data value averages for each year and removed the lowest-ranking training years. The residual data set was used to retrain the model and tested on the second held-out independent prospective test set from 2022 (for illustration, see Fig. 1, Temporally Validated Feature Selection and Data Validation). All analyses were performed using the computational software Python (version 3.9.18) and R (version 4.3.1).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

We identify a total of 24,077 cancer patients who are eligible for the study. Figure S1 shows the cohort scoping strategy and exclusion criteria for identifying cancer patients undergoing anti-neoplastic therapy. The feature set includes a total of 1050 variables including demographics, medications, vitals, laboratory results, diagnoses and procedures, and systemic treatment regimen information. Among all patients, 5227 (21.71%) had an acute care event within 180 days after the index date, with 4097 (17.02%) hospital admissions and 1958 (8.13%) emergency department (ED) visits. Patients are on average 61.12 (SD = 14.49) years of age, predominantly female (55.4%), white (57.4%), and non-Hispanic (87.28%). The majority of patients received intravenous systemic therapy (57.48%). Table 1 shows the labels and baseline patient characteristics for the retrospective (2010–2018) and prospective (2019–2022) cohorts resulting from a single, temporal data split.

Prospective validation upon single data split

To assess the temporal stability of an ML model on retrospective data (Fig. 2), we perform a single data split and partition the dataset into a ‘retrospective’ training and ‘prospective’ validation cohort. We hypothesized that performing a single temporal data split is effective in assessing the capability of historical data from earlier periods in sustaining model performance on future time intervals. The results indicate the performance metrics of the classification model when trained on historical data up to 2018 and hypothetically implemented at the point of care in 2019. Patients who start antineoplastic therapy between 2010 and 2018 are grouped into the retrospective cohort, whereas patients starting therapy after December 2018 are assigned to the prospective validation cohort (Fig. 1). We subsequently select three classification models based on their capacity for outcome prediction from a sparse feature matrix: logistic Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Random Forest (RF). All models were then trained in four configurations (Fig. 2a–d) and tested on held-out test sets from either the same time period or a future validation cohort. The results from training and validation on the retrospective cohort (Fig. 2a) show an Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) of 0.81 [0.79, 0.82] for the LASSO, 0.80 [0.79, 0.82] for the XGBoost and 0.80 [0.79, 0.81] for the RF. When testing these models on the prospective cohort (Fig. 2b) performance decreases slightly, with an AUROC of 0.76 [0.76, 0.77] for the LASSO, 0.78 [0.78, 0.79] for the XGBoost and 0.78 [0.78, 0.79] for the RF. This performance is also slightly lower than when training and testing the models on the prospective cohort (Fig. 2c, LASSO: 0.81 [0.79, 0.82]; XGBoost: 0.81 [0.79, 0.83]; and RF: 0.80 [0.78, 0.82]) as well as data from the entire time span between 2010–2022 (Fig. 2d, LASSO: 0.78 [0.77, 0.79]; XGBoost: 0.79 [0.78, 0.80]; and RF: 0.79 [0.78, 0.80]). Since repeating all subsequent experiments for each classifier is impractical, we proceeded with the RF as our preferred model because of its high performance in the prospective validation experiment and shorter training time (Fig. 2b).

The violin plots highlight the performance of three machine learning models on held-out test sets in terms of Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC). Error bars show 95%-bootstrapped confidence intervals. Panel a shows model performance on retrospective cohort, i.e., when models are trained and tested on data from the same time period (2010–2018). The second panel (b) highlights performance when testing on future data (2019–2022). The last two panels (c and d) show performance when training and testing on most recent data (2019–2022) or when training the models on the full time span (2010–2022). The gray arrows indicate from which periods the train and held-out test set emanate.

Evolution of features and labels over time

Since a decrease in performance can be due to temporal changes in features, labels, or their joint distribution, we first analyzed the evolution of features and labels over time. We hypothesized that if there was, for example, a sudden drift post-2015 (switch from ICD9 to ICD10), this could motivate including mostly data from the period post-2015 in the training set. To assess shifts in clinical outcomes, we first calculated the ratio of acute care events (labels) over the incidence of therapy initiations in each month (Fig. 3a). The results show that this ratio fluctuates slightly but remains overall stable. Most acute care events take place in the first 50 days after initiating chemotherapy (Fig. 3b). Pain, anemia, fever, and nausea are proportionally the most important diagnoses underlying acute care utilization (Fig. 3c) during 2010–2018 and more recent years (2019–2022). Except for anemia, there is no quantitative difference larger than 5 percentage points in the proportional frequency of diagnoses associated with ACU between the two time periods.

The smoothed line plot in panel a show the ratio of acute care events (ACU) over therapy initiations between January 2010 and June 2022. The smoothed line plot in panel b shows the time to event from therapy initiation, with the mean-normalized number of events on each day after therapy initiation (index date) on the y-axis. The incidence of emergency department (ED) visits and admissions is highest in the first 50 days following therapy initiations. The bar plot (panel c) shows the share (frequency in percent) of diagnosis groups associated with acute care utilization, plotted separately for the retrospective cohort from 2010–2018 (blue) and the prospective validation cohort from 2019–2022 (red).

To further investigate the projection of features over time, we built on a previously reported approach24 to create a heatmap that shows the evolution of features between 2010 and 2022 (Fig. 4). Such heatmaps provide an intuitive and effective visualization to screen features for their overall variability and longevity, as well as to eliminate obsolete features—those that were previously influential but may be irrelevant for a current model due to discontinued use. We reasoned that understanding feature evolution is important, as data gathering is expensive and unused features might harm model performance5. Since displaying all features is impractical and the screening of more important features should be prioritized, we further refine this approach by combining it with Shapley value-based feature reduction. Shapley values are a model-agnostic approach to measure the importance of each feature for prediction based on their average marginal contribution35. To illustrate this approach, we select the top 15 features using the Shapley values from training the RF on a retrospective cohort (2010–2014). The heatmap displays large variations for almost all top features. For example, the variable that records the intention in which a therapy is administered (‘Therapy Goal Curative’) is frequently used from 2010–2015 and 2018–2022, but barely used during 2015–2018. Similarly, the distribution of the results from the lab test for serum albumin shifts to higher means after 2019. Among the top 15 features, antineoplastic therapy- and laboratory results-related features are most frequent.

The heatmap shows the evolution of the top 15 features (ranked by Shapley values), standardized, and organized into monthly segments. Feature importance is determined using the training set and evolution is monitored beyond this period (white vertical line). For illustration, the white rectangle depicts the row-normalized average albumin serum result of patients initiating systemic therapy in April 2015. Changes in color saturation depict variations in the standardized means (continuous variables) and frequencies (binary variables) of a feature and thus highlight shifts in practices, usage of procedure/diagnosis/laboratory units or distributions of the patient population. Features that transition to dark purple hue indicate their diminishing usage and potential discontinuation (categorical variables) or that the mean has decreased (continuous variables).

Sliding window, model longevity and progression analysis

As a third step in our framework, we interrogated the performance of the prediction model on different training and test periods to assess model longevity/robustness as well as potential trade-offs between data quantity and data recency. This is achieved through two sub-experiments (Fig. 5). First, the model is trained on a moving three-year time window and its performance is then analyzed as the temporal gap between train and test set widens (Fig. 5a). Second, we perform a progression analysis that emulates the real-world implementation of the model: the model is implemented from the outset and its performance is shown both without retraining and when retrained annually using the cumulative data available up to but excluding the test set year (Fig. 5b). The results from the sliding window experiment highlight that depending on which years (fixed training sample size, n = 3000) the model is trained, performance on the future test sets varies considerably, ranging between AUROCs of 0.64 and 0.76. Rows with overall dark purple hue highlight training years that lead to comparatively poor performance. The heatmap further reveals that, except for training on 2013–2015, all models perform as good or better on test data from 2022 than the two years before (2020–2021).

The heat maps show different permutations of training and test sets to assess model robustness or degradation over time. Performance is evaluated using Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC). The color-coding shows the model performance for each training-validation pair. For the sliding window experiment (a), the model is trained on a moving three-year data span (vertical axis) and then evaluated as the temporal gap between training and validation years widens (horizontal axis, longevity analysis). The progression analysis (b) simulates a scenario where the model is implemented from the outset, with annual retraining using all available data up to that point, and prediction on a single future year. This approach mimics the real-world process of continuously updating the model as new data emerges each year. Specifically, the triangle heatmaps in a and b offer three readings: first, the values on the diagonal display model performance on the year directly following the training period; second, moving along the horizontal axis highlights changes in model performance as the temporal gap between training and test years widens; third, moving along the vertical axis depicts how model performance is influenced when training the model on increasingly more recent years, but testing on the same data from a single future year. The final heatmap (c), shows the incremental learning in the reverse direction, i.e., when adding a fixed set of 1000 training samples from each previous year.

The results from the real-world progression analysis show that adding training years at the beginning leads to higher performance on most test years (vertical reading). At later stages, model performance does not necessarily increase when adding more recent data. For example, model performance on test data from 2022 is comparable for the models trained on the full data from 2010–2019 versus the model trained on full data from 2010–2021. Finally, the experiment of reverse incremental learning (Fig. 5c), i.e., when adding a fixed number of data points (n = 1000) from each previous year retrospectively, shows that the model benefits from integrating more recent data. When adding data from 2013 (vertical reading), performance drops considerably for almost all models.

Temporally validated feature selection and data valuation

Finally, we hypothesized that if features and training points were affected by a shift or particularly noisy, those could be addressed using feature reduction and data valuation algorithms. Particularly, since adding 2013 as a training year results in a considerable performance drop, we hypothesized that the average data value of this year as well as those during the COVID-19 pandemic would be much lower than those of feature years. In this final experiment, we develop a ‘denoising’ strategy that would allow us to selectively narrow down an extensive dataset like ours to temporally robust feature and training sets, while ensuring robust performance on future data. This is achieved in two steps (Fig. 6).

The heatmap in a displays the normalized datum values averaged for each month after calculation by KNNShapley and Data-Oob on each training datum from 2010 and 2020 and tested on data from 2021. Bins with green hues depict months with, on average, the most valuable training data for predicting on the prospective cohort. Red hue indicates that a month is composed of at least some training data that is less valuable when training a model. b shows the ranked data values group by each year, based on the data valuation algorithms KNN-Shapley and Data-Oob for training examples between 2010 and 2020. Data values are converted to rank space for comparability. Error bars denote 95%-bootstrapped confidence intervals. c shows performance evolution under recursive feature elimination based on permutation importance in terms of Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) with 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals (shading). The dashed line displays the point at which all features with negative signs are removed. This process is repeated three times.

First, we perform data valuation with validation on a prospective test set using four data valuation algorithms (Supplementary Fig. S2), including KNNShapley 31, Data-Oob32, Data Banzhaf33, and Leave-One-Out (control). Data valuation algorithms enable placing an importance value for model performance, evaluated on a held-out test set, on each datapoint in the training set30. To select the top-performing data valuation algorithm, we first perform recursive data pruning for each algorithm separately on data from the training period (2010–2020). For all data valuation algorithms, we use the full feature set. From the comparison of all four data valuation algorithms, we identify the KNNShapley and Data-Oob as the top-performing algorithms (Supplementary Fig. S2), which are then used for data valuation on a held-out prospective test set (2021). The heatmap in Fig. 6a displays the normalized data values averaged for each month resulting from KNNShapley and Data-Oob algorithms. The color coding shows strong consistency between both methods. Months with lower data value averages are mainly observed for earlier time periods in the training data. Fig. 6b shows the yearly data value averages determined by the algorithms KNNShapley and Data-Oob for training examples between 2010 and 2020 and the prospective validation set from 2021. The data value averages show a sharp decline for years before 2014. Based on this result, we train our final model (Fig. 6d) on training data from 2014–2020.

Second, we use permutation importance to determine feature importance among our set of 1050 features. Specifically, permutation importance shuffles a single column (or feature) to measure how important that feature is for predicting a given outcome28. When used on a model trained on retrospective data (2010–2020) and tested on future, held-out data (here 2021), permutation importance is a model-agnostic approach to identify features that truly maintain model performance on future data. In the presence of correlation, the approach can further be combined with hierarchical clustering based on the Spearman rank-order correlations. In our study, we train a Random Forest on data from 2010–2020 and used the year 2021 as a first held-out test set. We subsequently perform stepwise (n = 10) recursive feature elimination (Fig. 6c). We then remove all features with negative signs, i.e., without importance for future test data. We repeat this experiment three times, each time removing all features with negative signs. This results in a subset of 405 features. Fig. 6c shows the impact on performance when recursively removing features ranked by permutation performance and at random.

Finally, the model is retrained on the reduced feature set with data from 2014–2020 and tested on the second held-out test set from 2022 that is independent of all previous data valuation and feature selection (for approach, see Fig. 1). Supplementary Fig. S3 shows comparable performance of all three models (LASSO, XGBoost, and RF) in three configurations: when trained i) on full data, ii) upon data pruning, i.e., after removing the years with the lowest data value averages (2010–2013), and iii) upon data pruning and permutation importance-based feature reduction. Supplementary Fig. S4 shows no clear performance differences between models using a k-nearest neighbor (KNN)-based imputation when trained and tested on held-out data from 2010–2018, as well as tested prospectively on data from 2019–2022.

Discussion

Our study advances a diagnostic framework aimed at identifying and adjusting for temporal shifts in clinical ML models, crucial for ensuring their robust application over extended periods. This approach, developed through analyzing over a decade of data in oncology, emphasizes the difficult balance between the advantage of leveraging historical data and the disadvantage of including data of diminishing relevance due to changes in medical practice and population characteristics over time. By focusing on the temporal dynamics of clinical data, our framework promotes the development of models that are robust and reflective of current clinical practices, thereby enhancing their predictive accuracy and utility in real-world settings. This is accomplished by delineating a framework comprising essential domains, readily applicable yet frequently overlooked or omitted in local validation processes32. This methodology not only enables inspection of temporal shifts in data distributions but also provides an approach for the validation and implementation of clinical predictive models, ensuring they remain effective and relevant in rapidly evolving medical fields—especially when deployed at the point of care.

The work in this study emphasizes the importance of data timeliness and relevance and advocates for a data-centric approach with rigorous prospective local validation, followed by strategic feature and data selection for model training36,37,38. This is critical to improve data quality, reduce the need for complex architectures, and train ML models with the data that reflect contemporary clinical protocols and patient demographics38,39. This approach allows researchers to apply a models of their choice within the framework. The results from the feature evolution and incremental learning experiments show that relevance of data is as important as its volume. Simply increasing the volume of data, i.e., including more data from the past, does not necessarily enhance performance. This challenges some traditional beliefs that accumulating larger datasets guarantees improved accuracy40,41,42.

The swift progress in fields like oncology, highlighted by breakthroughs in immunotherapies, illustrates how an entire treatment landscape can experience multiple paradigm shifts within a single decade. Thus, relying on extensive historical data spanning 10 to 15 years can result in a model that is narrowly tuned to non-representative, old care episodes, thereby degrading its real-time applicability and performance. In highly dynamic clinical settings, the need for heightened vigilance in identifying data that remain relevant under current practices and care standards becomes paramount39. This complexity is exacerbated as individuals frequently move between various healthcare systems and providers.

Developing a nuanced understanding of how outcomes, features, and health practices evolve over time is critical for selecting the most relevant data for ML models. This is an increasingly important challenge that has been widely acknowledged across fields and is addressed in many dimensions by this framework3,43,44. Models trained on historical data often experience performance deterioriation45, a phenomenon that underscores the necessity for periodic retraining or updating20,21,45. As shown in the sliding window experiment, the suitability of certain training years over others can be a decisive factor for the model’s success when deployed at the point of care39. This is relevant beyond baseline model training as the question of how and when models should be retrained, once deployed, has received much attention in recent years20,21.

The potential for data to become outdated implies a trade-off between the recency and the volume of data, prompting researchers to prioritize more recent datasets. However, some treatment regimens and patient distributions may remain stable for extended periods, rendering data from a broader timespan applicable for model training. Thus, identifying the date beyond which data becomes irrelevant for training ML models is a key challenge46. Understanding patterns of drift is also relevant for data processing steps such as imputation. If drift is strong but gradual, using a KNN approach with small k might be advantageous as the imputation is likely to rely primarily on (more recent) neighbors that are less affected by drift. In contrast, when there is moderate gradual drift combined with severe, temporary drift, we might want to increase k. Using a larger number of neighbors from more distant years will then be used for imputation and can offset more recent (and potentially sudden) trends. Imputation approaches are particularly important if missingness affects many variables. In this study, more than half of the features were curated using procedure and diagnosis codes, which are prone to high levels of missingness due to shifts in medical practices and coding standards. This highlights the need for an effective imputation strategy in medical applications.

Detecting pivotal junctures poses an intricate task, especially in extensive data sets and without historic knowledge of the data. By methodically evaluating model performance and data relevance, we delineate a strategic cut-off point for the inclusion of training data in such highly dynamic environments. While one might instinctively consider excluding data from 2015 and before due to the known transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding standards, our findings reveal a notable decline in data values and in performance in the incremental learning experiment in 2013. Overall, training the model on older data still yields reasonable performance on future test years. This may be due to the presence of many stable features (with low variation) as illustrated in the heatmap, moderate baseline drift, and/or model robustness. Moreover, sudden external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic may introduce drift in more recent data. This may result in additional variability that offsets the relative benefits of adding more recent data to the training process. This research shows that older data can still yield strong model performance, reducing the need for frequent retraining.

Moreover, the utilization of incremental learning techniques also enables us to understand the actual impact of sudden events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, on model performance. The average data value for training data in 2020 exhibited a moderate decrease compared to the peak values observed in the preceding years of 2017–2019. Our framework, thus, offers the advantage to contrast data values and performance during periods of drift with those outside such periods (e.g., just before or after the pandemic). The known care disruption and delayed (cancer) incidence under the COVID-19 pandemic can strongly affect model performance in many areas30. Detecting performance issues and quantifying the value of data during such periods provides more clarity on how to address such years, i.e., whether to remove them as a potential safeguard against model overfitting on unique, non-recurring distributions39.

In addition to external shocks, novel therapies can suddenly lead to changes in the distribution of clinical outcomes, adverse events, and patient demographics. This corroborates the need for local validation strategies that also monitor more recent data and explains why simply excluding old data might not always be enough. Our framework supports the need for adaptive model training and offers the potential to design more nuanced model (re)training schemes for clinical machine learning as well as other disciplines.

Our application included several outcomes (ED visits and hospital admissions), tumor types (and thus diseases), disease stages, and data types (e.g., ranging from demographic data to treatment-specific information), and an extended time span for sudden and gradual temporal drift. This complex and multifaceted application was intentional to allow for easy adaptation to less complex scenarios, promoting generalizability.

Our study further advances the management of acute care utilization (ACU) in cancer patients under systemic therapy and demonstrates that ML models effectively discriminate between patients with ACU within 180 days of initiating systemic therapy and those without. Identifying individuals at high risk for acute care use is increasingly recognized in the literature as clinically important for reducing mortality, enhancing the quality of care, and lowering cost47. In this study, we illustrate the methods by which algorithms can undergo local and prospective validation, a crucial step in facilitating their transition to clinical application and bridging the gap between the development and implementation of models48.

The study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. Our cohort was a population from Northern California and, despite the inclusion of diverse practice sites, may not be generalizable to other populations. While our framework is designed to be a generalizable local validation strategy, its broader utility across various medical domains, data environments, and care settings is yet to be demonstrated. Oncology represents a noisy, highly variable data environment, which is well-suited for studying time-related performance aspects of clinical machine learning models. Extending the framework to other domains, data types (e.g., imaging or genome sequencing data), and care settings with seasonal influences (e.g., infectious diseases) may require additional adjustments to account for different clinical contexts and domain-specific data sources40,42,46.

This framework provides a stepwise approach for prospective validation and leverages data valuation methods to assess temporal drift. Our framework combines a suite of visualization approaches with temporally validated feature reduction and data selection strategies. This offers a strategy to select the most pertinent training data from datasets spanning over a decade30,46. Understanding when relevant drifts occur and which data to select for model training is a challenge that is critical beyond the field of oncology. For example, models to predict cardiovascular outcomes for patients with hypertension might be affected by drift that is caused by the change in hypertension diagnosis criteria (>130/80 mmHg) in 201749. Such changes in diagnostic criteria are likely to result in a shift in the baseline characteristics of patients diagnosed with hypertension and can thus affect model performance. By showcasing the framework’s utility across diverse domains, we will gain further evidence of its broader applicability and generalizability.

Data availability

Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, the data supporting this study cannot be made publicly available as they contain protected health information (PHI). Researchers interested in collaboration or further inquiries may contact the corresponding author. The source data for the final plots are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15344733.50.

Code availability

Code and scripts for visualization are available at https://github.com/su-boussard-lab/temporal-validation-ml50 and at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15344733.50.

References

Han, R. et al. Randomised controlled trials evaluating artificial intelligence in clinical practice: a scoping review. Lancet Digit Health 6, e367–e373 (2024).

Morin, O. et al. An artificial intelligence framework integrating longitudinal electronic health records with real-world data enables continuous pan-cancer prognostication. Nat. Cancer 2, 709–722 (2021).

Doku, R., Rawat, D. B. & Liu, C. Towards federated learning approach to determine data relevance in big data. in 2019 IEEE 20th international conference on information reuse and integration for data science (IRI) 184–192 (IEEE, 2019).

Lu, J. et al. Learning under concept drift: A review. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 31, 2346–2363 (2018).

Finlayson, S. G. et al. The clinician and dataset shift in Artificial Intelligence. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 283–286 (2021).

Elmore, J. G. et al. Concordance and reproducibility of melanoma staging according to the 7th vs 8th Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. JAMA Netw. Open 1, e180083 (2018).

Sharma, P. et al. Immune checkpoint therapy-current perspectives and future directions. Cell 186, 1652–1669 (2023).

Boehm, K. M., Khosravi, P., Vanguri, R., Gao, J. & Shah, S. P. Harnessing multimodal data integration to advance precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 22, 114–126 (2022).

Martins, F. et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16, 563–580 (2019).

Magee, D. E. et al. Adverse event profile for immunotherapy agents compared with chemotherapy in solid organ tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann. Oncol. 31, 50–60 (2020).

Quinonero-Candela, J., Sugiyama, M., Schwaighofer, A. & Lawrence, N. D. Dataset shift in machine learning (MIT Press, 2008).

Nestor, B. et al. Feature robustness in non-stationary health records: caveats to deployable model performance in common clinical machine learning tasks. in Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference 381–405 (PMLR, 2019).

Agniel, D., Kohane, I. S. & Weber, G. M. Biases in electronic health record data due to processes within the healthcare system: retrospective observational study. BMJ 361, k1479 (2018).

Kusnoor, S. V. et al. A narrative review of the impact of the transition to ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM/PCS. JAMIA Open 3, 126–131 (2020).

Khera, R., Dorsey, K. B. & Krumholz, H. M. Transition to the ICD-10 in the United States: An Emerging Data Chasm. JAMA 320, 133–134 (2018).

Carroll, N. M. et al. Performance of cancer recurrence algorithms after coding scheme switch from International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision to International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision. JCO Clin. Cancer Inf. 3, 1–9 (2019).

Han, X. et al. Changes in cancer diagnoses and stage distribution during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA: a cross-sectional nationwide assessment. Lancet Oncol. 24, 855–867 (2023).

Moreno-Torres, J. G., Raeder, T., Alaiz-Rodríguez, R., Chawla, N. V. & Herrera, F. A unifying view on dataset shift in classification. Pattern Recognit. 45, 521–530 (2012).

Ji, C. X., Alaa, A. M. & Sontag, D. Large-scale study of temporal shift in health insurance claims. in Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning 243–278 (PMLR, 2023).

Guo, L. L. et al. Systematic review of approaches to preserve machine learning performance in the presence of temporal dataset shift in clinical medicine. Appl Clin. Inf. 12, 808–815 (2021).

Davis, S. E., Greevy, R. A. Jr, Lasko, T. A., Walsh, C. G. & Matheny, M. E. Detection of calibration drift in clinical prediction models to inform model updating. J. Biomed. Inf. 112, 103611 (2020).

Subasri, V. et al. Diagnosing and remediating harmful data shifts for the responsible deployment of clinical AI models. medRxiv, 2023.2003. 2026.23286718 (2023).

Guo, L. L. et al. Evaluation of domain generalization and adaptation on improving model robustness to temporal dataset shift in clinical medicine. Sci. Rep. 12, 2726 (2022).

Saez, C., Gutierrez-Sacristan, A., Kohane, I., Garcia-Gomez, J. M. & Avillach, P. EHRtemporalVariability: delineating temporal data-set shifts in electronic health records. Gigascience 9, giaa079 (2020).

Services, T.C.f.M.M. 2023 Chemotherapy Measure Updates and Specifications Report (10/03/23). (The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://qualitynet.cms.gov/outpatient/measures/chemotherapy/methodology).

Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B: Stat. Methodol. 58, 267–288 (1996).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (2016).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Jiang, K., Liang, W., Zou, J. Y. & Kwon, Y. Opendataval: a unified benchmark for data valuation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 36, 28624–28647 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2023).

Jia, R., et al. Efficient task-specific data valuation for nearest neighbor algorithms. In Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 12, 1610–1623 (2019).

Kwon, Y. & Zou, J. Data-oob: Out-of-bag estimate as a simple and efficient data value. In International Conference on Machine Learning 18135-18152 (PMLR, 2023).

Wang, J. T. & Jia, R. Data banzhaf: A robust data valuation framework for machine learning. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics 6388-6421 (PMLR, 2023).

He, H. & Garcia, E. A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 21, 1263–1284 (2009).

Lundberg, S.M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 4768–4777 (2017).

Jakubik, J., Vössing, M., Kühl, N., Walk, J. & Satzger, G. Data-centric artificial intelligence. Business & Information Systems Engineering 66, 507–515 (2024).

Mazumder, M., et al. Dataperf: Benchmarks for data-centric ai development. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 36, 5320–5347 (2023).

Northcutt, C. G., Athalye, A. & Mueller, J. Pervasive Label Errors in Test Sets Destabilize Machine Learning Benchmarks. In 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2021) (2021).

Subbaswamy, A. & Saria, S. From development to deployment: dataset shift, causality, and shift-stable models in health AI. Biostatistics 21, 345–352 (2020).

Kelly, C. J., Karthikesalingam, A., Suleyman, M., Corrado, G. & King, D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 17, 195 (2019).

Teno, J. M. Garbage in, Garbage out-words of caution on big data and machine learning in medical practice. JAMA Health Forum 4, e230397 (2023).

Wiens, J. & Shenoy, E. S. Machine learning for healthcare: on the verge of a major shift in healthcare epidemiology. Clin. Infect. Dis. 66, 149–153 (2018).

Liang, W. et al. Advances, challenges and opportunities in creating data for trustworthy AI. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 669–677 (2022).

Pandl, K. D., Feiland, F., Thiebes, S. & Sunyaev, A. Trustworthy machine learning for health care: scalable data valuation with the Shapley value. In Proceedings of the Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning 47–57 (2021).

Wu, Y., Dobriban, E. & Davidson, S. Deltagrad: Rapid retraining of machine learning models. In International Conference on Machine Learning 10355–10366 (PMLR, 2020).

Van Calster, B., Steyerberg, E. W., Wynants, L. & van Smeden, M. There is no such thing as a validated prediction model. BMC Med. 21, 70 (2023).

Alishahi Tabriz, A. et al. Trends and Characteristics of potentially preventable emergency department visits among patients with cancer in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2250423 (2023).

Li, R. C., Asch, S. M. & Shah, N. H. Developing a delivery science for artificial intelligence in healthcare. NPJ Digit Med 3, 107 (2020).

Whelton, P. K. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 71, e13–e115 (2018).

Schuessler, M., Fleming, S., Meyer, S., Seto, T. & Hernandez-Boussard, T. Diagnostic framework to validate clinical machine learning models locally on temporally stamped data. (GitHub, 2025, https://github.com/su-boussard-lab/temporal-validation-ml).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Sc., S.F., and T.H-B. designed the research. M.Sc., T.H-B., and S.F. developed the methods. M.Sc. and T.S. extracted the data and performed chart reviews for ascertaining the labels and the cohort scoping. M.Sc. and S.M. designed the graphics. M.Sc. analyzed the data, created and collated the graphics, and designed the illustrations of the framework. M.Sc. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors interpreted the results and reviewed the manuscript. T.H-B. provided support, guidance and leadership for the project and oversaw the research process. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR003142. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other institutions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Ravi Parikh and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [Peer review reports are available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schuessler, M., Fleming, S., Meyer, S. et al. Diagnostic framework to validate clinical machine learning models locally on temporally stamped data. Commun Med 5, 261 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00965-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00965-w

This article is cited by

-

Diagnostic framework to validate clinical machine learning models locally on temporally stamped data

Communications Medicine (2025)