Abstract

Background:

Transthoracic echocardiography remains the primary non-invasive method for assessing cardiac function in clinical practice. However, technical challenges in acquiring accurate apical 4-chamber-long-axis (A4CLAX) views have historically limited mouse studies to left ventricle (LV) assessment using parasternal short-axis (SAX) M-mode imaging.

Methods:

To overcome this limitation, we developed an A4CLAX imaging approach for mice and performed a comparative analysis with established echocardiographic methods to assess cardiac function in healthy mouse hearts. To evaluate the utility of A4CLAX in detecting disease progression, we longitudinally monitored cardiac function of C57BL/6 N mice (male and female) following severe transverse aortic constriction (TAC), using both long-axis biplane (LAX-BP) and conventional SAX M-mode assays.

Results:

Here we show that LAX-BP echocardiography demonstrates volumetric accuracy comparable to cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and detects significant LV functional decline within the first week post-TAC–changes that are not clearly captured by M-mode imaging. Importantly, A4CLAX further enables clinically relevant Doppler assessments, allowing detection of mitral valve regurgitation, restrictive filling patterns, and desynchronized valve motion. It also facilitates right ventricle (RV) functional evaluation and improved atrial visualization, revealing progressive enlargement of the left atrial (LA) and left atrial appendage (LAA) associated with worsening diastolic function.

Conclusions:

The A4CLAX imaging approach provides clinically comparable, comprehensive echocardiographic evaluation in murine models and offers improved sensitivity for detecting subtle changes in cardiac performance during disease progression.

Plain language summary

Echocardiography is a non-invasive imaging method commonly used to check heart function in people. However, it has been hard to get clear echocardiographic images of all heart chambers in mice. We imaged mouse hearts from a different direction in healthy mice and in a disease model that mimics heart pressure overload. Our method provided more accurate and detailed information than traditional techniques. It also allowed us to detect heart problems early, including valve issues and changes in heart chamber size and function. Our imaging method could be used to study heart disease and test treatments in mice, ultimately improving treatments for people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small animal models, particularly transgenic mice, are extensively utilized in cardiovascular research. Accurately assessing cardiac performance in these models is essential for precise phenotyping of genetic variants and evaluating therapeutic interventions. For over two decades, the evaluation of systolic and diastolic functions in experimental cardiovascular disease models has relied extensively on echocardiography, due to its favorable cost and ease of use compared to other modalities, such as cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging. The parasternal short-axis (SAX) M-mode assays is commonly used in basic research with assumption of a spherical shape for the LV, a simplification that may compromise accuracy, especially in diseased hearts1. Scientists have made significant strides in enhancing the precision of murine echocardiography, including the adoption of single-plane analysis from parasternal long-axis B-mode (PLAX) assays2, PLAX speckle tracking3,4,5, consecutive short-axis views6, or a modified SAX-biplane Simpson method incorporating PLAX with multiple short-axis views2,7,8.

The long-axis biplane Simpson’s method remains the most used and recommended method for echocardiographic volumetric assessment of the LV in human9,10. The LV length is measured from the apical point to the mitral valve ring bisector; these volume measurements require tracing the interface between the LV cavity and compacted myocardium. Consequently, the biplane Simpson’s calculation necessitates clear two-dimensional echocardiographic images from two monoplanes of apical long-axis 2- and 4-chamber views. Although the PLAX 2-chamber view is frequently used in murine echocardiography, acquiring clear on-axis apical 4-chamber view in mice remains challenging despite significant efforts11,12.

Recently, we have developed an imaging approach that consistently captures high-quality apical 4-chamber-long-axis (A4CLAX) views of the mouse heart. We combined this with PLAX (2-chamber) images to create a modified Simpson’s method, termed the long-axis biplane (LAX-BP) assay. This LAX-BP method yields CMR-comparable assessments of LV volumetric parameters, including end diastolic (EDV) and end systolic (ESV) volumes, in both wildtype and miR1-mutated transgenic mouse hearts13.

In this study, we first conducted a comparative analysis between the A4CLAX approach and established echocardiographic approaches to assess cardiac function in healthy mouse hearts. We applied A4CLAX to a widely used heart disease model––transverse aortic constriction (TAC)––to evaluate its sensitivity in detect subtle changes in the LV and monitor the progression of heart diseases in mice. Moreover, we explored how the superior A4CLAX imaging technique facilitates many holistic and clinically comparable echocardiography analyses in mouse hearts, including assessments of the right ventricle (RV), atria, and hemodynamics of the atrioventricular valves. Our studies demonstrate that the A4CLAX method provides clinically comparable and comprehensive evaluation of cardiac function in murine models.

Methods

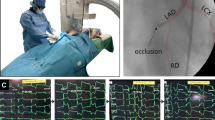

Transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery

Adult C57BL/6 N mice were purchased from the Charles River and housed in a temperature-controlled environment under an alternating 12-h light/dark cycle at the Ohio State University (OSU). All animal handling procedures adhered strictly to the guidelines approved by the OSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under the protocol 2019A00000085.

This study compares two methods within the same group of animals. A sample size of six animals was determined to be sufficient to achieve statistical significance, based on the following parameters: a statistical power of 0.80, a type I error probability (α) of 0.05, a standard deviation of 8%, and an expected mean difference of 10%. Accordingly, 6 male and 6 female mice (10 weeks old) were used in the comparison studies in healthy heart.

Additionally, six male and six female adult mice (10 weeks old) were used in the TAC model to induce LV pressure overload. In brief, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (2.5%), intubated, and ventilated using a respirator (120 breaths per minute; 0.1 ml tidal volume). A midline sternotomy was performed to expose the aorta, and a 7-0 Prolene suture was placed around the aorta distal to the brachiocephalic artery. The suture was tightened using a blunted 28-gauge needle next to the aorta to standardize the degree of constraint; the needle was then removed and the chest was closed. Buprenorphine-ER was administered preoperatively, and meloxicam was given postoperatively to minimize pain and discomfort. The success of TAC surgery was confirmed by observing restricted blood flow through the aortic arch using color doppler echocardiography imaging (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Conventional murine echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed using a Vevo 3100 system (FUJIFILM VisualSonics) with an MX550D transducer. We had conducted traditional echocardiography of mouse heart as described previously14. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2.0% isoflurane in oxygen and placed on a heated pad. During echocardiography imaging, the isoflurane concentration was adjusted as needed to maintain anesthesia while keeping the heart rate above 400 bpm, ensuring physiological relevance. Parasternal long-axis images were taken with the aortic outflow tract in plane to maintain consistency of PLAX image acquisition and were subsequently used as a guidance view for finding the optimal orientation of parasternal short-axis (SAX) view images, as well as to be used for the LAX-BP approach outlined below. Parasternal SAX images at the level of the papillary muscles, used for M-mode analysis, were obtained to determine the left ventricular chamber diameter at end-diastole (LVDD), anterior (LVAW) and posterior wall thickness (LVPW) in both systole (s) and diastole (d). Fractional shortening (FS), ejection fraction (EF), stroke volume (SV), and cardiac output (CO) of the LV were calculated from the analyses of parasternal SAX M-mode measurements.

Following PLAX image acquisition, three parasternal SAX images were obtained at the mid-papillary (mid-ventricular) level, apical, and basal levels. These four 2D images were then analyzed using Vevo Lab software (FUJIFILM VisualSonics) to assess cardiac function based on the short-axis Simpson’s biplane (SAX-BP) method2.

A4CLAX view imaging approach and LAX-BP assessments

For A4CLAX view imaging, anesthetized mice were placed on a heated echocardiography platform. Under the mouse’s upper abdominal area, a 1 cm diameter soft support was positioned to elevate the back, to allow for better subcostal probe access and orienting the long axis of the heart towards the left subcostal region of the thoracic cavity. The platform was then tilted to a 40-degree angle, utilizing gravity to amend heart configurations and situation in the chest cavity due to the elevated chest, thus bringing it closer to the diaphragm and subsequently the transducer probe allowing for improved image clarity. Recording was conducted using an MX550D transducer to capture the A4CLAX view via subcostal imaging. Precise adjustment of the transducer is essential to ensure it aligns directly with the heart’s axis (Fig. 1). While this subcostal recording approach should generally obtain images of all four chambers with relative ease (Supplemental Videos 1 and 2), several key landmarks must be met to guarantee accurate A4CLAX view acquisition: (1) Full longitudinal length of both the LV and RV must be visible, including the apex; (2) The mitral annulus and mitral valves must be included within the plane; (3) The motion of the RV tricuspid annulus should be in view, however it’s important to note that tissue echo shadowing can sometimes obscure the tricuspid valve, posing visualization challenges.

The A4CLAX view diagram shows key landmarks of all four chamber of the heart–left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV), left atrium (LA), and right atrium (RA)–including ① LV apex, ② mitral valve and annulus, and ③ tricuspid annulus and valve. The parasternal long-axis (PLAX) view was taken with ① clear LV apex as well as ④ aortic outflow (AO) tract. The parasternal short-axis (PSAX) view was taken perpendicular to PLAX view needs visualization of LV and RV as well as papillary muscles at the mid papillary level for consistent image acquisition. The PSAX view representative image also includes M-mode recording plane placement at mid-papillary level.

To assess the volumetric parameters using LAX-BP approach, the Vevo LAB software (FUJIFILM VisualSonics) were utilized to quantify the monoplane volumes from LV tracings in both the PLAX and A4CLAX views that were subsequently used in the modified Simpson’s LAX-BP calculation. In brief, using the Vevo LAB software, the LV was traced from the mitral annulus to the apex along the LV wall in A4CLAX view, and from the aortic valve to the apex in the PLAX viewing plane (Supplementary Fig. 2). Visualization of wall movements aids in precise placement of the LV trace. The average LV volumes at the end of systole (ESV) and diastole (EDV) were calculated from each monoplane by the Vevo LAB software, resulting in two sets of values: 1) PLAX-ESV and PLAX-EDV, 2) A4CLAX-ESV and A4CLAX-EDV. Consequently, we formulated equations to derive the LAX-BP-ESV and LAX-BP-EDV values.

The LAX-BP-ESV and LAX-BP-EDV values were then utilized to estimate other volumetric parameters, such as EF, SV, and CO.

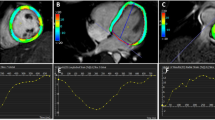

CMR imaging validation study

An MRI validation study was performed on a 11.7-T (500 MHz) MR microimaging system comprising a vertical magnet of bore size 30 mm (Bruker Biospin, Ettlingen, Germany). Quadrature-driven birdcage coils with inner diameters of 25 mm were used to transmit/receive the NMR signals. Briefly, mice were anesthetized in an anesthetic chamber using 1.5% isoflurane in oxygen. Mice were imaged using a 30-mm1H-imaging probe after scouting for long- and short-axis orientation of the heart, using a k-space segmented cardiac-triggered and ECG gated FLASH sequence. Cine MR images with 6 to 9 contiguous short-axis slices (slice thickness 1 mm) were acquired, comprising between 20 and 31 frames per cardiac cycle (echo time of 1.43 ms, repetition time of 4.6 ms, 2 averages per slice, matrix size of 256 × 256, and a field of view of 2.56 cm, giving an inplane resolution of 100 × 100 µm). Finally, a single, long-axis, cine dataset was acquired. Total time for an MRI study was around 90 min. Six healthy mice (3 male and 3 female) and four TAC mice (3 male and 1 female) with moderately impaired cardiac function 4 weeks post-TAC were initially used for MRI validation; however, one female TAC mouse died during MRI imaging.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M, with “n” indicating the number of distinct biological samples. Randomization was not performed because the study compared two imaging approaches within the same animals. Statistical significance of differences in means was estimated using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t tests with multiple testing adjustments conducted in GraphPad Prism version 10.1.0 for macOS (GraphPad Software). A p < 0.05 indicates a statistical significance.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Methodological comparisons of LAX-BP with other echocardiographic approaches

To understand the newly developed LAX-BP approach, we assessed cardiac function in a cohort of normal mice (11 males and 7 females) using several established echocardiography approaches: parasternal SAX M-mode, PLAX, short-axis Simpson’s biplane (SAX-BP)2,7,8, as well as the newly developed A4CLAX and LAX-BP approaches. We compared their assessments of key LV functional parameters, including EDV, ESV, EF, SV, and CO.

In the comparison between newly developed A4CLAX and LAX-BP approaches, no significant difference were observed between male and female mice. Our analysis also revealed no significant difference between M-mode and SAX-BP measurements. However, both M-mode and SAX-BP consistently produced significantly higher values for all LV function parameters compared to the LAX-BP method (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1).

Cardiac function assessed by LAX-BP in normal mice (11 males and 6 females) was compared with other established methods, including parasternal M-mode (M-mode), short-axis Simpson’s biplane (SAX-BP), parasternal long-axis (PLAX), and apical 4-chamber long-axis (A4CLAX). Left ventricle function parameters evaluated include heart rate (HR, a), end-diastolic volume (EDV, b), end-systolic volume (ESV, c), ejection fraction (EF, d), stroke volume (SV, e), and cardiac output (CO, f). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t tests with multiple testing adjustments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns indicates no significance. Supplementary Table 1 provides the detailed statistical analyses.

Furthermore, PLAX assessments of EDV, ESV, SV, and CO were significantly higher than those obtained by A4CLAX, likely reflecting synchronized but distinct contractile dynamics between the posterior/anterior walls (PLAX plane) and septal/lateral walls (A4CLAX plane). Importantly, the LAX-BP approach captures contraction dynamics from both planes, providing a more comprehensive and reliable assessment of LV function.

A4CLAX echocardiography effectively monitors the LV pathological progression in TAC mouse hearts

We next investigated whether A4CLAX approach can effectively reveal cardiac pathological progression using TAC mouse model. In this study, one female mouse did not survive the TAC surgery and two mice (1 male and 1 female) died in the second- or third-week post-surgery, leading to their exclusion from further analysis. As a result, complete measurements of cardiac performance were obtained from 5 male and 4 female TAC mice. Compared to pre-operation (Pre-Op) measurements, the thickness of LV anterior (LVAW) and posterior (LVPW) walls significantly increased over time, particularly within the first week post-surgery (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 2). Specifically, the LVAW at diastolic phase was increased from 0.789 ± 0.040 mm to 0.969 ± 0.064 mm (week1, p = 0.026 vs. Pre-Op) and 1.005 ± 0.067 mm (week 4, p = 0.026 vs. Pre-Op, p = 0.712 vs. week 1); the LVPW at diastolic phase changed from 0.612 ± 0.043 to 0.763 ± 0.050 mm (week 1, p = 0.025 vs. Pre-Op) and 0.812 ± 0.059 mm (week 4, p = 0.008 vs. Pre-Op, p = 0.559 vs. week 1). Consistently, a significant increase of the LV diameter at diastolic (LVDD, Fig. 3a) and systolic phases also rapidly occurred from week 1 to week 4. These results indicate that TAC-induced hypertrophic remodeling rapidly occurred within the first week.

a The LV internal diameter at end-diastole (LVDD) and diastolic (-d) thickness of LV anterior (LVAW) and posterior (LVPW) walls were measured in TAC mice pre-operation (Pre-Op), and at 1 (1WK) and 4 weeks (4WK) post-TAC surgery using PSAX M-Mode assays. b, c With comparable heart rates maintained among all anesthetized TAC mice (n = 9), LV function, including heart rate (HR), ejection fraction (EF), stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), end-diastolic volume (EDV), and end-systolic volume (ESV), of TAC mice (n = 9) was evaluated before and after surgery with both PSAX M-mode and the LAX-BP echocardiogram. d CMR validation in 3 TAC mice at 4 weeks post TAC showed that LAX-BP and CMR provided comparable assessments, while M-mode significantly overestimated both EDV and ESV. e Bland-Altman plot assays for EDV and ESV in 6 normal (empty circles) and 3 TAC (filled squares) mice showed that LAX-BP exhibits a higher agreement with CMR, compared to M-mode. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t tests with multiple testing adjustments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 ****P < 0.0001 versus the Pre-Op group; #P < 0.05 versus TAC-1WK group; & & &P < 0.001 & & & &P < 0.0001, M-mode vs. LAX-BP, NS indicates no significance. Supplementary Table 2 provides the detailed statistical analyses.

Leveraging the clarity of A4CLAX images of mouse hearts (Supplemental Videos 1 and 2), we developed a modified Simpson’s LAX-BP approach for detailed volumetric assessments of LV function. To determine if LAX-BP is more sensitive than the traditional parasternal SAX M-mode approach to detect subtle changes during the pathological progression in diseased hearts, we applied both methods to monitor LV function in TAC mice at comparable heart rates. Both LAX-BP and M-mode assessments showed significant changes of LV function from week 1 to week 4 post-TAC, while the assessments of M-mode were notably higher than that of LAX-BP assay (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 2).

The parasternal SAX M-mode assays demonstrated that TAC hearts underwent a gradual and consistent remodeling process, with a steady decrease in LV volumetric parameters such as EF, SV, and CO over time (Fig. 3b). In contrast, LAX-BP assays revealed a sharp decline in EF within the first week post-surgery (30.22 ± 2.48% at week 1 vs. 51.33 ± 2.82% Pre-Op, p = 0.0001), followed by a slower decline by week 4 (23.30 ± 3.72%, p < 0.0001 vs. Pre-Op, p = 0.089 vs. week 1). This pattern was evident in the LV SV and CO, which decreased significantly in the first week but then relatively stabilized between week 1 and week 4 in TAC mice. Given that these mice underwent a severe 28 G TAC procedure, the resulting pressure overload likely triggered a rapid initial LV response, followed by a slower progression in functional deterioration. This LAX-BP observation aligns with the rapid hypertrophic remodeling progression of LV wall thickness illustrated in Fig. 3a.

LV EDV and ESV values estimated by M-mode were significantly higher than those obtained with the LAX-BP approach, despite both approaches detecting an increase in LV volume post-TAC. M-mode was less sensitive, showing only an average increase of 7.31 µl in EDV and 13.36 µl in ESV within the first week post-TAC, whereas LAX-BP detected substantially larger changes–18.37 µl in EDV and 22.00 µl in ESV (Fig. 3c). This discrepancy in capturing LV volumetric changes likely contributes to differences in the overall accuracy of echocardiography approaches.

To further assess this, we evaluated LV volume in six normal and three TAC mice using LAX-BP, parasternal SAX M-mode echocardiography, and CMR. The M-mode approach consistently overestimated LV volumes in both healthy and diseased hearts. In TAC mice, M-mode significantly overestimated LV EDV (122.50 ± 8.71 µl vs. 89.00 ± 3.22 µl by CMR, p = 0.019) and ESV (90.90 ± 4.41 µl vs. 63.67 ± 6.33 µl by CMR, p = 0.028) in TAC mouse hearts, whereas LAX-BP produced measurements closely aligned with CMR (Fig. 3d). This overestimation by M-mode also led to inflated values for SV and CO (Fig. 3b). Similar results were observed in myocardial infarction (MI) mice, where M-mode overestimated EDV, ESV, SV, and CO compared to LAX-BP, although no significant difference between the methods was found in EF (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 3).

We further evaluated the overall agreement between the two echocardiographic approaches and CMR using Bland-Altman analysis. LAX-BP demonstrated strong concordance with CMR, with minimal bias (5.72 µl for EDV and 6.85 µl for ESV) and low variability–– substantially smaller than the bias observed with M-mode (29.02 µl for EDV and 17.55 µl for ESV) (Fig. 3e). In summary, our findings demonstrate that LAX-BP echocardiography provides LV volumetric measurements that closely align with CMR, supporting its accuracy in both normal and diseased mouse hearts.

A4CLAX echocardiography enables clinically comparable assessments of atrioventricular hemodynamics and mitral valvule regurgitation

Doppler imaging, including pulsed wave, tissue, and color Doppler, is widely recommended in clinic practice for visualizing blood flow patterns and assessing hemodynamics and valvular function9,10. In contrast to parasternal SAX views15 and foreshortened 4-chamber views7,11 previously adapted for doppler assessments in basic cardiovascular research, the A4CLAX view provides clear visualization of the mitral valve leaflets and lateral annulus in mouse hearts, allowing for more consistent sample gate placement for Doppler analyses.

Using this view, we conducted pulsed wave Doppler imaging from the apical 4 chamber perspective in a clinically relevant format (Fig. 4a). The A4CLAX imaging plane is aligned with the direction of blood flow, and the Doppler sample gate was adjusted to run parallel to the long axis of the LV, ensuring optimal alignment between the imaging plane/gate angle and mitral inflow direction. Color Doppler further enhanced visualization by clearly depicting blood flow directionality and may be used to refine angle correction for pulsed wave Doppler acquisition.

a Diagram and waveform recordings of A4CLAX-view Pulsed Wave Doppler (PWD) of the mitral valve (MV) in mouse hearts (n = 4) illustrate data from pre-operation (Pre-Op), 1-week (1WK) and 4-week (4WK) post-TAC surgery, highlighting ejection time (ET), early and late diastolic MV inflow velocity (E and A waves), E/A ratio, E wave deceleration, and E wave deceleration time, showing high LV filling patterns. b Speckle tracking-based strain analyses from both PLAX and A4CLAX views (n = 8) revealed a rapid decrease in LV wall strain in TAC mice as early as 1WK post-TAC. c Diagram and A4CLAX-view Tissue Doppler (TD) images at the mitral annulus (n = 4) show changes in early and late diastolic myocardial tissue motion peak velocity (E’ and A’ waves) and E/E’ ratio, suggesting LV stiffening. d Color Doppler images and diagrams of cardiac cycle blood flow pre- and post-TAC, demonstrating diastolic turbulent inflow and mitral regurgitation in TAC mice. e Calculations of MV pressure half time (PHT) and MV Area (n = 4), consistent with MR seen in color doppler. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t tests with multiple testing adjustments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, versus the Pre-Op group; #P < 0.05, versus the 1WK group. Supplementary Table 4 provides the detailed statistical analyses.

Pulsed wave Doppler analysis showed a significant increase in mitral valve ejection time (ET) from 41.28 ± 0.44 ms to 53.26 ± 2.07 ms at 4 weeks post-TAC (n = 4, p = 0.0015) (Fig. 4a). This prolongation suggests that increased afterload due to aortic constriction, combined with progressive LV decompensation, delays blood ejection from the LV. Additionally, TAC mice exhibited an early rise in the mitral valve inflow E wave velocity and a reduction in A wave velocity during the first week post-surgery, resulting in a significant increase in the E/A ratio–from 1.19 ± 0.12 to week 1 1.81 ± 0.18 (n = 4, p = 0.043 vs. Pre-Op) and week 4 1.71 ± 0.11 (p = 0.036 vs. Pre-Op). This was accompanied by a marked increase in E wave deceleration (E-Dec) and a significant shortening of E wave deceleration time, indicating restrictive filling (Supplementary Table 4). Consistently, speckle tracking-based strain analyses from both PLAX and A4CLAX views showed a rapid reduction in LV wall strain in TAC mice, particularly within the first week post-TAC (Fig. 4b). This early shift toward restrictive filling and diastolic dysfunction aligns with the significant decline in LV function observed by LAX-BP echocardiography (Fig. 3b).

We also conducted tissue Doppler imaging in a clinical format by assessing the LV lateral mitral annulus in the A4CLAX view (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Table 4). This analysis revealed a significant reduction in the peak velocity of late diastolic myocardial tissue motion (A’), decreasing from 29.70 ± 2.44 mm/s at Pre-Op baseline to 15.35 ± 3.62 mm/s at 4wk post-TAC (n = 4, p = 0.0223). In contrast, early diastolic myocardial motion peak velocity (E’) showed no significant change. As a result, the E/E’ ratio significantly increased from 25.78 ± 2.68 to 33.68 ± 1.43 (p = 0.0473) over the four-week progression, indicating elevated LV filling pressure and suggesting emerging diastolic dysfunction in the hypertrophic heart.

Additionally, trans-mitral color Doppler imaging in the A4CLAX view clearly visualized forward blood flow into the LV during diastole and out to the aorta during systole in pre-TAC mouse hearts. In TAC mice, a greater degree of turbulent diastolic inflow was observed (Fig. 4d), likely associated with elevated early filling E velocities, as revealed by pulsed wave Doppler (Fig. 4a). As early as one-week post-TAC, color Doppler detected backflow into the left atrium during LV systole, indicating the onset of mitral valve (MV) regurgitation (Fig. 4d).

Concurrently, pressure half time (PHT) measured by pulsed wave Doppler was significantly decreased at one-week post-TAC and remained relatively stable thereafter. As a result, the calculated MV area, derived from PHT, was significantly increased in TAC mice at one-week post-surgery (46.00 ± 5.47 mm2 vs. 25.46 ± 3.69 mm2 Pre-Op, p = 0.032), consistent with the presence of MV regurgitation identified via color Doppler (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Table 4).

In summary, A4CLAX echocardiography effectively captured the rapid progression of LV remodeling in TAC mouse hearts. These results highlight the capability of the A4CLAX technique to perform clinically relevant Doppler assessments, enabling precise evaluation of atrioventricular hemodynamics and mitral valve function in mouse models.

A4CLAX echocardiography enables clinical evaluations of RV function in TAC mice

In addition to assessing LV function, we explored the utility of the A4CLAX view for evaluating right heart function in mice. Although the current Vevo LAB software does not include a dedicated protocol for RV analysis, we adapted the LV tracing tool to assess the RV. Specifically, we traced the RV from the lateral and medial tricuspid annulus to the apex during both diastole and systole. Fractional area change (FAC) was calculated using the formula: [Area Diastole – Area Systole)/Area Diastole] x 100. At 4 weeks, we observed a non-significant increase in both systolic and diastolic RV areas (Fig. 5a). There was also a declining trend in RV-FAC, although this change did not reach statistical significance.

a A4CLAX Echocardiography measures RV function (n = 6), showing an increasing trend in RV area during systolic and diastolic phases and a declining trend in RV Fractional Area Change (FAC) from pre-operation (Pre-Op) to 1-week (1WK) and 4-week (4WK) post-TAC surgery. b TAC mice exhibited an increasing trend in Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE, n = 6) c Speckle tracking-based strain analyses from the A4CLAX views highlighted synchronized RV wall movements (contraction and relaxation) in pre-Op mice and asynchronous movements in TAC hearts. The RV free wall strain of TAC mice significantly decreased over time (n = 3, p = 0.0095 versus the Pre-Op group). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t tests with multiple testing adjustments.

To perform a tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) assay, primarily used to assess overall RV longitudinal function, we created an anatomical M-mode recording section using A4CLAX view images. In the Vevo LAB software, the M-mode recording line was positioned over the RV, crossing the lateral RV annulus towards the apical aspect, and aligned parallel to the annulus movement (normally toward the apex). The TAPSE assay was conducted by measuring the absolute annular distance traveled from diastole to systole. We observed a non-significant increase in TAPSE among TAC mice, rising from 0.785 ± 0.078 mm to 0.964 ± 0.055 mm 4 weeks post-surgery (n = 5, p = 0.051) (Fig. 5b). This trend may be attributed to the enlargement of the RV lumen.

We also utilized speckle tracking-based strain analysis to study RV function in the A4CLAX view images and identified regional desynchrony in the RV free wall movement in TAC mice. The RV free wall longitudinal strain (RVFWLS) assay, which necessitates exceptionally clear imaging of the entire RV free wall, has been shown to be more sensitive than RV-FAC and TAPSE in detecting RV dysfunction in clinical settings16. With advanced A4CLAX imaging, we successfully conducted the RVFWLS assay in TAC mice, observing a significant decrease in RVFWLS from 14.09 ± 2.82% to 6.25 ± 1.40% at week 1 (n = 3, p = 0.056), and further to 2.19 ± 0.69% at week 4 (p = 0.0095, Fig. 5c). These findings confirm that RV remodeling in response to the TAC-induced pulmonary hypertension begins as early as the first week post-surgery, resulting in progressive RV dysfunction.

A4CLAX echocardiography identifies asynchronous movements between the ventricular chambers in mice

Using 2-dimensional speckle tracking, we further assessed regional contractile synchronicity along the septal and lateral walls of both LV and RV. Typically, septal wall motion is integral to LV contraction and relaxation, whereas RV contraction relies heavily on the RV free wall and longitudinal annular motion. During the diastolic phase, marked by mitral valve opening, the LV lateral wall and septum move outward from the LV lumen, exhibiting radial relaxation vectors in healthy hearts. As a result, RV speckle tracking strain demonstrated synchronized movements, with velocity vectors of the RV free wall and the septal wall aligned in the same direction throughout the cardiac cycle in Pre-Op mice (Fig. 6a, Supplemental Video 3).

a Diagrams and speckle tracking illustrate synchronous movement of the right (RV) and left ventricles (LV) wall in pre-operation (Pre-Op) mice. Two distinct desynchrony phenotypes in the ventricle chambers were observed 4 weeks (4WK) post-TAC: regional LV wall desynchronization (b) and ventricular chamber asynchrony (c), highlighting altered cardiac dynamics in TAC mice.

In TAC mice, two distinct patterns of desynchrony between RV and LV contraction were noted. In one phenotype, despite normal RV free wall relaxation, the septal wall moved towards the LV lumen during diastole, indicating LV dyssynchronization (Fig. 6b, Supplemental Video 4). Another phenotype showed asynchronous RV and LV movements, with the RV free wall contracting during LV diastole (Fig. 6c). As RV free wall contraction makes up the largest component to RV function, this asynchronous diastolic movement increased the RV pressure during what would be diastole, resulting in a delayed opening of the tricuspid valve. Echocardiographic recordings and ECG traces confirmed that tricuspid valve opening occurred only after the P-Wave, indicating that right atrial contraction was required for complete tricuspid valve opening (Supplemental Video 5).

A4CLAX approach enhances atrial echocardiographic assessments in mice

The A4CLAX echocardiography method clearly enables visualization of the left atrium (LA), including the left atrial appendage (LAA), allowing for detailed assessment of atrial remodeling in TAC-mice. In TAC mice, LA area significantly increased as early as one-week post-surgery, particularly during the diastolic phase, expanding from 4.98 ± 0.43 mm2 at Pre-Op baseline to 9.22 ± 1.30 mm2 at one week (n = 6, p = 0.044), and to 11.04 ± 1.81 mm2 at four weeks post-TAC (p = 0.0069 vs. Pre-Op, Fig. 7a). Concurrently, LA FAC significantly declined over time, suggesting elevated LA pressure and impaired atrial compliance (Supplementary Table 5).

a A4CLAX Echocardiography evaluates LA function (n = 6), demonstrating a significant increase in LA area during systolic and diastolic phases, along with a marked decline in LA Fractional Area Change (FAC) from pre-operation (Pre-Op) to 1-week (1WK) and 4-week (4WK) post-TAC surgery. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus the Pre-Op group; Supplementary Table 5 provides the detailed statistical analyses. b Significantly dilated LAA is highlighted by green traces. c LAA pulsed wase Doppler successfully captured sinus rhythm blood flow in mouse hearts. Four distinct waves were identified by aligning the waveform peaks with the ECG tracings. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t tests with multiple testing adjustments.

Consistent with these findings, A4CLAX imaging also revealed significant enlargement of the LAA in TAC hearts (Fig. 7b). To further evaluate LAA function, we performed pulsed wave Doppler analysis using the A4CLAX view (Fig. 7c). The LAA Doppler waveform showed clear sinus rhythm blood flow patterns, with waveform peaks aligning well with ECG tracings. This allowed us to identify key phases of atrial function, including (1) LAA contraction wave, (2) LAA filling wave, (3) negative systolic reflection wave, and (4) early diastolic LAA outflow wave. Together with LV and RV echocardiography assessments, these LA and LAA assays provide a comprehensive picture of cardiac function and disease progression in mouse models.

Additionally, the A4CLAX approach can be adapted to assess right atrial (RA) function. While the RA is partially visible in standard A4CLAX images, improved visualization was achieved by slightly adjusting the probe angle to focus on the right heart and correctly align the imaging plane using the tricuspid valve leaflets as a landmark. Representative images of the RA during diastole and systole are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, which can be used to evaluate RA function, including fractional area change.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that the A4CLAX approach significantly improves the capabilities of echocardiography for assessing cardiac function and detecting subtle pathological changes in mouse hearts. LAX-BP assays achieve CMR-comparable accuracy in evaluating LV volume in diseased mouse hearts. Furthermore, A4CLAX echocardiography extends beyond LV assessments to sensitively detect dysfunction in the atrial, right ventricle, and atrioventricular valves, providing detailed insights into pathological progression in mouse models of cardiovascular diseases. In clinical practice, the transition from simple M-mode echocardiography to more advanced imaging techniques took approximately two to three decades, from the 1950s to the 1980s17. It is reasonable to expect that the development of this A4CLAX approach will trigger a similar transition from simple M-mode echocardiography to clinically matched comprehensive assessments in mouse hearts. This will enable detailed evaluation of the morphology and functional performance of LV, RV, atria, and valves in mice.

Transthoracic echocardiography remains the primary non-invasive tool for clinical assessment of cardiac function and is routinely used to evaluate the morphology and hemodynamics of the LV and RV, as well as atrial and valvular function9,10. In cardiovascular research using mouse models, however, parasternal SAX M-mode echocardiography is commonly employed to estimate the hemodynamic functions of LV, based on an assumption of LV sphere-morphology. This assumption poorly reflects the heart’s longitudinal structure and raises concerns about the accuracy of parasternal SAX M-mode in assessing cardiac performance, especially in diseased mouse models.

While adaptations such as single-plane PLAX-view analysis2 and PLAX speckle tracking assays3,4,5 have improved measurement accuracy, these mono-plane assays still capture only a single dimension of cardiac motion. Methods involving consecutive short-axis views6 and SAX-BP with incorporated PLAX view2,7,8 were developed to offer more precise assessments. However, our studies found no significant difference between M-mode and SAX-BP in evaluating cardiac function in healthy mice. Moreover, like CMR, these multi-consecutive view echocardiographic techniques are time-consuming and often impractical for basic research, where large cohorts of mice must be evaluated efficiently. These limitations help explain the continued widespread use of parasternal SAX M-mode for estimating LV function in mouse models, despite its recognized shortcomings.

Significant effort has been invested with limited progress in acquiring an on-axis 4-chamber view of the mouse heart11,12, which is required for the most practical and clinically recommended biplane Simpson’s method for echocardiographic LV volume assessment9,10. To address the anatomical challenges posed by cardiac orientation within the dome-shape thoracic cavity of mice, we implemented a modified imaging setup: using a soft support to elevate the back, tilting the platform at a 40-degree angle, and aligning the probe with the heart’s long-axis via a subcostal approach (Fig. 1). These adjustments led to the development of a A4CLAX imaging technique and the LAX-BP method, a modified Simpson’s assay, from A4CLAX and PLAX images of mouse hearts. During the development of this A4CLAX technique, we compared LAX-BP and the conventional parasternal SAX M-mode assays with the gold standard CMR assay in a cohort of adult normal mice. Our findings indicated that LAX-BP method could accurately evaluate LV volumes, including EDV and ESV, whereas M-mode assessments tended to overestimate these values, leading to inflated calculations of other functional parameters (e.g., SV and CO)13. Compared to the gold standard of CMR, LAX-BP Bland-Altman plot assays have demonstrated comparable accuracy in assessing LV volume in both normal and diseased (e.g., TAC) mouse hearts. Indeed, LAX-BP assays revealed rapid pathological LV remodeling in TAC mice that primarily occurred in the first week post-surgery. This was evidenced by significant and swift decline in LV function (Fig. 3b), increased LV wall thickness (Fig. 3a), LV restrictive filling (Fig. 4a), enlarged LA size and reduced LA FAC (Fig. 7a). These results are consistent with clinical observations of restrictive filling patterns18, thus showing that TAC-induced reduction in LV compliance and diastolic function, as well as severe increase in LV/LA pressure gradient occurred rapidly after surgery. In contrast, parasternal SAX M-mode assessments failed to capture this dynamic progression, only detecting LV volumetric functional parameter decline over a gradual and continuous process, although a rapid pathological progression of LV wall thickening was revealed by parasternal SAX M-mode. In summary, LAX-BP provides accurate LV functional evaluation and sensitively detects subtle changes of heart systolic pumping function, including EF, SV, and CO parameters, during the pathological progression of TAC hearts.

Adapted from clinical recommendation for Doppler assays, tissue Doppler from the parasternal SAX view has previously been used to measure endocardial and epicardial systolic velocities in mice15. Pulsed wave Doppler was also conducted using foreshortened apical 4-chamber view images to evaluate the diastolic function of mouse hearts7,11, in which the measured flow movement has a certain misaligned angle from the true blood flow in the heart. The inaccuracy concern of prior approaches has been resolved by A4CLAX echocardiography, which allows for pulsed wave Doppler assays to be conducted with perfect alignment with the direction of mitral and tricuspid blood flow. Similar to previous findings on TAC mice19,20,21, pulsed wave Doppler in A4CLAX images revealed a rapid pathological progression in LV of TAC mice, evidenced by significant changes in the E/A ratio, E wave deceleration and deceleration time, and distinct restrictive filling pattern, which are consistent with the pathological remodeling of LV wall thickness and significant diastolic dysfunction as early as one week post-TAC.

Color Doppler using PLAX B-mode image has historically been applied to study the hemodynamics in the LV22, RV23, and the aortic flow24 in mice. The PLAX view color Doppler provides a good angle to assess the flow through the LV outflow tract and is crucial for evaluating hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and aortic dilation or aneurysm. Importantly, the A4CLAX echocardiography provides an in plane horizontal cross-section of all four chambers, thus the A4CLAX view color Doppler assays can not only study the blood filling and emptying patterns of both the left and right sides of mouse hearts, but remarkably can better evaluate the hemodynamic function and patterns of mitral and tricuspid valves and identify the severity of regurgitation. Indeed, A4CLAX echocardiography detected higher presence of turbulent diastolic inflow in the LV of TAC mice (Fig. 4d) and mice with genetic mutations13; while detecting mitral valve regurgitation in diseased TAC hearts. A4CLAX echocardiography also enables estimation of MV area in mice, providing valuable insight into pathological valve remodeling in diseased hearts; however, further comprehensive quantification methods are needed for fully validate this approach.

In the clinic, pulsed wave Doppler of left atrial appendage has been employed as an indicator of diastolic function25, to assess the risk of thrombus formation26, and to predict maintenance of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation patients27,28. In our study, A4CLAX echocardiography revealed dramatically enlarged LA and LAA in TAC mice and successfully identified 4 waveforms of LAA blood flow with sinus rhythm cardiac cycles using LAA pulsed wave Doppler. This showcases the significant potential of the A4CLAX technique for use in atrial fibrillation studies involving mouse models.

RV examinations are recommended for all comprehensive clinical echocardiographic studies9,10. Due to the technical challenge of acquiring apical 4 chamber view in mice, however, clinically utilized RV assessments were previously not feasible in preclinical mouse models. In the past, mouse RV function has been evaluated using parasternal SAX M-mode, PLAX-B mode, and color Doppler imaging23. The A4CLAX technique now enables clinically comparable RV assessments during diastole and systole phases, including RV FAC, TAPSE29, as well as RVFWLS–a more sensitive marker for detecting RV dysfunction in clinical settings16. Notably, current software limitations sometimes prevent accurate speckle tracking of wall movement near the annulus; therefore, RV speckle tracking analysis is restricted to approximately the upper two-thirds of the RV wall. While further optimization is needed, our RV analyses at 4 weeks post-TAC revealed pathological trends, although RV FAC and TAPSE didn’t show statistically significant dysfunction. Importantly, RVFWLS assay using A4CLAX views revealed a significant decline in RV function as early as one week post-TAC. This early dysfunction may reflect rising pulmonary pressure, consistent with the progression of pulmonary hypertension as a secondary consequence of the TAC procedure19,20,21.

Before the development of A4CLAX methodology for the mouse heart, the measurement of murine LA function was typically performed using speckle-tracking echocardiography from a modified PLAX window30 and foreshortened apical 4-chamber views31. However, clinical LA echocardiography assessments are conducted from the A4CLAX view, which offers complete visualization of the LA and is necessary for a thorough evaluation of LA size, shape, and function9,10. Similarly, our A4CLAX approach revealed dramatic changes in LA morphology (e.g., size and shape) and a significant decline in LA FAC of TAC mice, mainly occurring in the first week post-surgery, which is consistent with the pathological progression of LV remodeling.

Since all chambers of the mouse heart are clearly visualized in A4CLAX views, the synchronization of chamber movements can now be studied for the first time, as far as we are aware, in mice using echocardiography. Using this method, we successfully identified distinct asynchrony patterns between the LV and RV movements. Notably, in one TAC mouse with lower chamber asynchrony phenotype, A4CLAX echocardiography revealed that the tricuspid valve only fully opened following the ECG P-wave of atrial contraction, showing a delayed opening of the tricuspid valve. This type of research is now possible in mouse hearts using the distinct capabilities of the A4CLAX technique.

Overall, the innovative A4CLAX technique significantly facilitates the implementation of more comprehensive clinical echocardiography assessments in basic cardiovascular research using mouse models. These clinically matched assessments will significantly improve the translational applications of discoveries from numerous basic research studies utilizing mouse models.

Data availability

All echocardiographic data analyzed in this study are publicly available through Data Dryad (Dataset https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.wdbrv161r)32.

References

Sosnovik, D. E. & Scherrer-Crosbie, M. Biomedical imaging in experimental models of cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 130, 1851–1868 (2022).

Heinen, A. et al. Echocardiographic analysis of cardiac function after infarction in mice: validation of single-plane long-axis view measurements and the Bi-Plane simpson method. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 44, 1544–1555 (2018).

Bauer, M. et al. Echocardiographic speckle-tracking based strain imaging for rapid cardiovascular phenotyping in mice. Circ. Res. 108, 908–916 (2011).

Bhan, A. et al. High-frequency speckle tracking echocardiography in the assessment of left ventricular function and remodeling after murine myocardial infarction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circulatory Physiol. 306, H1371–H1383 (2014).

Sturgill, S. L., Shettigar, V. & Ziolo, M. T. Antiquated ejection fraction: basic research applications for speckle tracking echocardiography. Front. Physiol. 13, 969314 (2022).

Dawson, D. et al. Quantitative 3-dimensional echocardiography for accurate and rapid cardiac phenotype characterization in mice. Circulation. 110, 1632–1637 (2004).

Russo, I. et al. A novel echocardiographic method closely agrees with cardiac magnetic resonance in the assessment of left ventricular function in infarcted mice. Sci. Rep. 9, 3580 (2019).

Rutledge, C. et al. Commercial 4-dimensional echocardiography for murine heart volumetric evaluation after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound. 18, 9 (2020).

Lang, R. M. et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 28, 1–39.e14 (2015).

Galderisi, M. et al. Standardization of adult transthoracic echocardiography reporting in agreement with recent chamber quantification, diastolic function, and heart valve disease recommendations: an expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 18, 1301–1310 (2017).

Schnelle, M. et al. Echocardiographic evaluation of diastolic function in mouse models of heart disease. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 114, 20–28 (2018).

Richards, D. A. et al. Distinct phenotypes induced by three degrees of transverse aortic constriction in mice. Sci. Rep. 9, 5844 (2019).

Kacira, E. et al. Long-axis biplane echocardiography sensitively detects the progressing functional deterioration of mouse heart. Circ. Heart Fail. 17, e011046 (2024).

Yang, D. et al. MicroRNA-1 deficiency is a primary etiological factor disrupting cardiac contractility and electrophysiological homeostasis. Circ. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. e012150. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.123.012150 (2023).

Sebag, I. A. et al. Quantitative assessment of regional myocardial function in mice by tissue Doppler imaging: comparison with hemodynamics and sonomicrometry. Circulation. 111, 2611–2616 (2005).

Inciardi, R. M. et al. Right ventricular function and pulmonary coupling in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 82, 489–499 (2023).

Fraser, A. G., Monaghan, M. J., van der Steen, A. F. W. & Sutherland, G. R. A concise history of echocardiography: timeline, pioneers, and landmark publications. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 23, 1130–1143 (2022).

Masutani, S., Little, W. C., Hasegawa, H., Cheng, H. J. & Cheng, C. P. Restrictive left ventricular filling pattern does not result from increased left atrial pressure alone. Circulation. 117, 1550–1554 (2008).

Deng, H., Ma, L. L., Kong, F. J. & Qiao, Z. Distinct phenotypes induced by different degrees of transverse aortic constriction in C57BL/6N Mice. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 641272 (2021).

Mohammed, S. F. et al. Variable phenotype in murine transverse aortic constriction. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 21, 188–198 (2012).

Tannu, S., Allocco, J., Yarde, M., Wong, P. & Ma, X. Experimental model of congestive heart failure induced by transverse aortic constriction in BALB/c mice. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 106, 106935 (2020).

Shekhar, A., Aristizabal, O., Fishman, G. I., Phoon, C. K. L. & Ketterling, J. A. Characterization of vortex flow in a mouse model of ventricular dyssynchrony by plane-wave ultrasound using hexplex processing. IEEE Trans. Ultrason Ferroelectr. Freq Control. 68, 538–548 (2021).

Cheng, H. W. et al Assessment of right ventricular structure and function in mouse model of pulmonary artery constriction by transthoracic echocardiography. J. Vis. Exp. e51041. https://doi.org/10.3791/51041 (2014).

Patten, R. D., Aronovitz, M. J., Bridgman, P. & Pandian, N. G. Use of pulse wave and color flow Doppler echocardiography in mouse models of human disease. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 15, 708–714 (2002).

Medrano, G. et al. Left atrial volume and pulmonary artery diameter are noninvasive measures of age-related diastolic dysfunction in mice. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 71, 1141–1150 (2016).

Garcia-Fernandez, M. A. et al. JL. Left atrial appendage Doppler flow patterns: implications on thrombus formation. Am. Heart J. 124, 955–961 (1992).

Wang, Y. C. et al. Identification of good responders to rhythm control of paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation by transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Cardiology. 104, 202–209 (2005).

Di Salvo, G. et al. Atrial myocardial deformation properties predict maintenance of sinus rhythm after external cardioversion of recent-onset lone atrial fibrillation: a color Doppler myocardial imaging and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiographic study. Circulation. 112, 387–395 (2005).

Berglund, F., Pina, P. & Herrera, C. J. Right ventricle in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart. 106, 1798–1804 (2020).

Zhang, M. J. et al. Atrial myopathy quantified by speckle-tracking echocardiography in mice. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 16, e015735 (2023).

Colazzo, F. et al. Murine left atrium and left atrial appendage structure and function: echocardiographic and morphologic evaluation. PLoS ONE10, e0125541 (2015).

Dataset https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.wdbrv161r; (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Small Animal Imaging Shared Resource at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center and Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, Columbus, OH for the CMR validation study. The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grant number P30 CA016058. This research was supported by the Start-up Fund from The Ohio State University (OSU) (to J.D.F.), funding provided by the OSU President’s Research Excellence Accelerator award (to J.D.F.), and grants from the National Institutes of Health (grants NIH-R01HL139006 to I.D. and J.D.F., R21OD031965 to J.D.F. R01AG060542 to M.Z. R01HL148103 to Y.H. R01HL171689, R01 HL156652 and R01 HL165751 to T.J.H.) and American Heart Association 24IPA1267153 and 24TPA1285242 (to J.D.F.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.K.: study design, echocardiography data acquisition and analysis of TAC mice, manuscript writing, and revision. M.F.O.: echocardiography data acquisition and analysis of healthy mice. N.H.T. echocardiography data acquisition and analysis of MI mice. S.L.S. and M.T.Z.: speckle tracking strain analysis. X.X. and T.J.H.: mouse TAC and MI surgery. Y.H. scientific discussion, data interpretation and analysis. I.D.: scientific discussion and data interpretation, J.D.F.: study design, overall project supervision, manuscript writing and revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: A PCT application on the A4CLAX echocardiography method was filed on May 16, 2024. Applicant: ohio state innovation foundation. Inventors: Jidong Fu and Ege Kacira. Application number: PCT/US2024/029579. Status of application: published. The application covers all features of the A4CLAX approach, including functional analysis of the ventricles, atria, and valves using A4CLAX views, including LAX-BP, speckle tracking-based strain analysis, and color Doppler and tissue Doppler.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Daria De Giorgio and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kacira, E., Oueis, M.F., Tamimi, N.H. et al. Advanced 4-chamber echocardiography techniques enable clinically matched precise characterization of heart disease progression in mice. Commun Med 5, 325 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01036-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01036-w