Abstract

This review summarizes key virological parameters of SARS-CoV-2, the clinical spectrum of COVID-19, antiviral options, resistance, and the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 during the first four years of the pandemic. It draws on evidence that has been continuously updated throughout the pandemic by the interdisciplinary working group ‘SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostics and Evolution’ at Robert Koch Institute (RKI), Germany’s national public health institute. We describe basic SARS-CoV-2 characteristics and highlight notable virus variants from 2020 to mid-2023. During this period, the nationwide collection of SARS-CoV-2 genomes provided a substantial resource for monitoring viral lineage frequencies and mutations. We summarize this dataset to underscore the importance of virological surveillance in the context of public health and pandemic preparedness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2) is a coronavirus (genus: Betacoronavirus, subgenus: Sarbecovirus) identified in early 2020 as the causative agent of COVID-191. Coronaviruses are widely distributed among mammals and birds. They are classified in the Coronaviridae family of RNA viruses (realm: Riboviria, order: Nidovirales, suborder: Cornidovirineae), in which the large subfamily Orthocoronavirinae includes four genera: Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma-, and Deltacoronavirus. Because of their capacity for homologous recombination, coronaviruses can relatively easily expand their host range and overcome cross-species boundaries2. The seven known human pathogenic coronaviruses (HCoV) fall into two genera: Alphacoronavirus (HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63) and Betacoronavirus (HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-OC43, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2). The viruses HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1, and HCoV-OC43 are known as seasonal or endemic coronaviruses and primarily cause mild colds. However, in early childhood, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals, severe cases of pneumonia can occur3. SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 have only recently spilt over from animal reservoirs to humans4. Infections with these “emerging pathogens” can cause severe disease with fatal outcomes.

Betacoronaviruses are membrane-enveloped RNA viruses and form virions approximately 60-140 nm in diameter with large (20-25 nm long) surface glycoproteins (spikes)5 (Fig. 1). They have a single-stranded RNA genome of positive polarity that is about 30 kilobases long, making it one of the largest genomes of all known RNA viruses. The genome encodes 29 proteins, including 16 non-structural, four structural, and nine accessory proteins which are involved in various steps of the virus’ life cycle6. The non-structural proteins are responsible for RNA replication. The structural proteins are the spike glycoprotein (S), the envelope small membrane protein (E), the membrane protein (M), and the nucleoprotein (N). The S, E, and M proteins are incorporated into the viral membrane that envelops the nucleocapsid, which is composed of the N protein and the viral genome3. The S (or spike) protein is responsible for entering the host cell and consists of two subunits. The S1 subunit contains the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD), which binds to the host cell receptor, and an amino-terminal (N-terminal) domain (NTD). The RBD contains the receptor-binding motif (RBM), which, together with the NTD, is the main target of neutralizing antibodies7. After host cell receptor binding, the S2 subunit mediates the fusion of the viral envelope and host cell membrane and the subsequent viral RNA release into the cytoplasm7. Neutralizing antibodies directed against epitopes on the RBD and the NTD inhibit cell entry of the virus and are one of the strongest available correlates of vaccine-induced protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection8,9,10. Thus, many vaccines utilize exclusively the spike protein as antigenic component11,12,13. SARS-CoV-2, like SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63, engages the transmembrane angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) of host cells as a receptor, enabling subsequent entry into the host cell7: The spike protein of the virus attaches to the ACE2 receptor on the host cell and undergoes proteolytic activation. This activation involves cleavage at the S2’ site, facilitated by TMPRSS2 on the cell surface or by endosomal cathepsins within the cell. This process transitions the spike protein into a metastable state, allowing the viral and host cell membranes to fuse and initiate infection14,15. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are co-expressed at high levels in the nasal epithelium, which may explain the efficient spread and shedding of SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract16. High ACE2 density has been reported not only in the respiratory tract but also, for example, on enterocytes, vascular endothelial cells, renal epithelium, and myocardial cells17,18,19,20,21. Histopathological studies have demonstrated SARS-CoV-2 organ tropism for the lung, intestine, kidney, heart, and the central nervous system (CNS) (see22,23,24,25,26).

A Schematic of the SARS-CoV-2 virion showing the lipid bilayer envelope containing membrane (M) and envelope (E) proteins, spike (S) proteins with subunits S1 and S2, and the nucleocapsid (N) protein bound to the positive-sense single-stranded RNA (ssRNA (+)) genome. The spike protein engages the host ACE2 receptor and is primed by TMPRSS2. B Genome organization of SARS-CoV-2 (~29,800 bp), including open reading frames ORF1a and ORF1b encoding nonstructural proteins (NSP1–16), structural proteins (S, E, M, N), and accessory proteins. The spike (S) protein is further divided into domains, including signal peptide (SP), N-terminal domain (NTD), receptor-binding domain (RBD) with receptor-binding motif (RBM), subdomains (SD1, SD2), fusion peptide (FP), heptad repeats (HR1, HR2), transmembrane domain (TM), and cytoplasmic tail (CT). Cleavage sites for furin and TMPRSS2 are indicated. The figure combines published information and was adapted accordingly from refs. 253,254,255,256. Figure elements in A were created with BioRender.com.

In contrast to pre-Omicron variants, SARS-CoV-2 variants of the Omicron complex tend to use the endosomal entry pathway mediated by cathepsins L/B, rather than the membrane (ACE2) entry pathway mediated by TMPRSS227,28. Cathepsins are located in the endosome and the cleavage of cathepsin occurs endosomally when the virus-ACE2 complex is internalized via clathrin-mediated endocytosis into the late endolysosomes15.

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with the advent of extensive global sequencing and data-sharing capabilities. This created an unprecedented opportunity to monitor the adaptive evolution of a respiratory RNA virus in near real-time on a global scale. It allowed us to monitor the virus while it developed the capacity to circulate in the human population and transmit among individuals with prior immunological exposure29,30.

A comprehensive understanding of the challenges posed by SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, requires close collaboration among virologists, bioinformaticians, clinicians, epidemiologists, and public health experts. At Robert Koch Institute, the national public health institute of Germany, an interdisciplinary team has continuously reviewed evidence on several critical aspects of COVID-19, including diagnostic and clinical features as well as viral evolution throughout the first years of the pandemic. This review outlines data obtained from 2020 to 2023 as a result of these concerted efforts, emphasizing evolutionary aspects, especially the rise of virus variants such as the Omicron complex and their impact from a public health perspective. It provides data to illustrate the ongoing need for robust surveillance systems to detect changes in respiratory virus circulation, guiding clinical and public health decisions.

SARS-CoV-2 variant nomenclature

Based on their mutation profiles, SARS-CoV-2 genetic variants are classified into clades as provided by efforts such as Nextclade31, or into lineages by systems such as Pangolin32, which also considers epidemiological criteria including localized and temporally clustered occurrences. The terms “lineage” and “variant” are used interchangeably and both refer to viruses which differ in genome sequence by several mutations. A “sublineage” is a lineage descendant, i.e., it harbors the same mutations as the “parental lineage” in addition to its distinct mutations. Eventually, all lineages (or variants) with their sublineages are placed in a large genealogy of SARS-CoV-2, which is maintained by the Pangolin community32.

The effects of specific mutations on the phenotypic properties of the virus, such as transmissibility, virulence, or immunogenicity, are subject to intense investigations, as a firm understanding will allow more reliable estimates of the risks posed by emerging variants [summarized in refs. 33,34]. If these properties of the virus change, then the term “strain” is used to differentiate this new variant from the others.

WHO classifies variants of SARS-CoV-2 based on their potential impact on global health and, thus, the degree of surveillance efforts required for each variant35,36. A Variant Under Monitoring (VUM) is a SARS-CoV-2 variant with genetic changes potentially affecting viral characteristics that shows early signs of growth (transmission) advantage, necessitating increased monitoring. A Variant of Interest (VOI) features genetic alterations that affect viral properties, demonstrating a growth advantage in multiple WHO regions or significant epidemiologic impact, signaling a threat to global health. The highest risk is assigned to a Variant of Concern (VOC), which not only meets VOI criteria but additionally leads to higher disease severity, affects COVID-19 epidemiology significantly, or markedly reduces vaccine protection against severe disease requiring major public health interventions.

Throughout the pandemic, the WHO has categorized five SARS-CoV-2 variants as VOCs: B.1.1.7, B.1.351, P.1, B.1.617.2, and B.1.1.52937,38. In line with the simplified WHO supplementary nomenclature, these are also called Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron according to Greek letters in the order of discovery35. The characteristics of the pre-Omicron VOCs and the Omicron complex are described in more detail in Boxes 1–4.

Until March 2023, all Omicron sublineages within the Omicron complex were classified as VOCs. However, this automatic inheritance of the parental VOC designation limited the ability to categorize specific Omicron sublineages and sub-sublineages as VOC/VOI/VUMs themselves. Therefore, this classification system did not provide the resolution needed to differentiate new and phenotypically distinct sublineages from other variants, including the parental Omicron lineages (e.g. BA.1, BA.2). To better track the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants, the WHO announced on March 15, 2023, that notable Omicron sublineages could be classified as VUM or VOI, rather than being grouped under the Omicron VOC label36. The original Omicron parent lineage (B.1.1.529) was de-escalated and is now classified as a “formerly circulating VOC” along with Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta. Consequently, current Omicron variants lack the VOC label, even though they are not considered less dangerous than the B.1.1.529 parent lineage. The purpose of “resetting” the naming system was to enable appropriate naming and tracking of future sublineages that may be even more dangerous than the currently circulating ones. The declaration of a variant as VOC is still reserved for significant SARS-CoV-2 variants that are given a Greek letter name (e.g., Alpha, Delta, Omicron).

Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 evolution

Several factors, including the intrinsic mutation rate, virus and host biology, infection rates and selection pressures that have changed (and continue to vary) over the course of the pandemic, contribute to the evolution of the virus. Changes in the viral genome occur during the replication of RNA viruses in an infected host and can be transferred to the viral progeny, which are then subject to the immune selection pressure of their respective hosts. Although the RNA polymerase of coronaviruses has a rudimentary proofreading function that reduces such replication errors, SARS-CoV-2 can still accumulate a significant number of nucleotide polymorphisms. Additionally, recombination may occur when two genetically distinct viruses infect the same cell. However, within-host evolution of the virus does not directly translate into an observable between-host evolution39. Due to the short infectious period of SARS-CoV-2 (a few days)40, immunocompetent individuals typically transmit virus particles with minimal genetic variation compared to the initial infection. Outbreak genetic analyses have revealed that virus genomes obtained from transmission pairs (i.e., SARS-CoV-2 cases with an epidemiological link suggesting direct transmission) are identical for most pairs41,42,43. This attribute of SARS-CoV-2 biology contributes to the fact that the evolutionary rate of the virus is orders of magnitude lower than would be expected given its RNA polymerase error rate. However, high infection rates, or a prolonged course of infection may accelerate the overall rate of evolution despite the low rate of within-host evolution44. Importantly, infections that persist for months, occasionally observed in the context of immunocompromised individuals (so-called: long-shedders), may result in a vast array of mutant viruses with new capabilities45,46,47. While some of these highly evolved variants may be transmitted47, ongoing debate surrounds the extent to which long-term infections, particularly in immunocompromised patients, contribute to directed virus evolution46,48,49,50,51,52. This aspect remains a critical area of study in understanding the ability of the virus to adapt53.

Evolutionary rates and mutations

The evolutionary rate, or substitution rate, measures how fast detectable mutations accumulate in a viral population. Unlike the mutation rate, which includes all new mutations, the evolutionary rate focuses on those reaching significant frequencies44. Evolutionary rates vary among genes, in part due to heterogeneous selection pressures. Indeed, for SARS-CoV-2 evolutionary rates vary not only by genomic region but also by phase of the pandemic44. Here, Fig. 2A provides insight into the evolutionary rates over different SARS-CoV-2 genomic regions, based on over 8.5 million viral genomes obtained between January, 2020 and June, 202354,55,56,57 (for more details see Supplementary Text T1): During the first year of the pandemic, only few amino acid substitutions became fixed, indicating an overall low evolutionary rate. The two amino acid substitutions that did gain rapid predominance in early 2020, S D614G and, as part of the same haplotype, RdRp P323L (encoded by ORF1a/b) were associated with more transmissions, potentially reflecting adaptation to the human host58. In subsequent years, with rising case and transmission numbers, many more amino acid substitutions have accumulated.

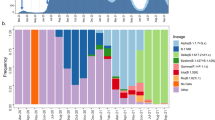

Amino acid (aa) substitutions shown here have exceeded a frequency of 70% in at least one calendar week (see Supplementary Text T1 for details). A The global view is based on more than 8.5 million genomes from GISAID and illustrates the relative occurrence of mutations within selected viral genes over time. Note that genes, signified by the vertical bar to the left are not depicted to scale; i.e., the density of amino acid substitutions accumulated over the spike gene ( ~ 3600 nt) is considerably higher than that accumulated over ORF 1a/b (>15,000 nt). B Mutation frequencies within the spike gene, resulting in amino acid replacements during any given calendar week, are depicted for the German genomic surveillance data set; to avoid sampling bias, only those 360,800 genomes were included that had been marked as “randomly sampled” by the submitter (see Supplementary Methods for detailed explanation). The abundance of selected major lineages circulating in Germany between the end of 2020 and April 2023 is visualized at the top of the heatmap. Data used for this visualization is part of the German SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance data set collected from the German Electronic Sequence Data Hub (DESH)59, published at ref. 60.

The viral gene accumulating the highest number of nonsynonymous mutations relative to its length was the spike gene. This implies that the evolutionary rate increased over the course of the pandemic and was highest over the spike gene. In other words, this SARS-CoV-2 gene evolved the fastest, particularly once widespread infections and vaccination campaigns led to the development of population immunity. A more detailed view into the rapid accumulation of spike amino acid substitutions is provided in Fig. 2B, which visualizes a portion of the German SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance dataset59,60. The observation that the spike gene has the highest evolutionary rate comes as no surprise: the spike protein is the target of all neutralizing antibodies induced by vaccines and infection. Mutations in the spike gene can confer resistance to neutralization by vaccine- or infection-induced immune responses (“immune evasion”, “immune escape”), facilitating breakthrough infections and transmissions from immunized individuals61. Higher immune selection pressure (due to the global increase in population immunity) promotes antigenic drift in the spike gene, enhancing immune escape. The high structural plasticity of the Spike RBD is particularly conducive to the emergence of escape variants62. Moreover, Spike amino acid changes can influence viral infectivity and replication capacity, e.g. by increasing ACE2 receptor affinity and the ability for ACE2-independent cell entry63,64. This contrasts with the loss of structural stability of the spike trimer associated with some amino acid exchanges65,66. The balance of these factors determines the evolution of the Spike protein, a dynamic and complex process where transmissibility and immune escape are the ultimate determinants of positive selection.

The Omicron variant, which reached global predominance shortly after its emergence in late November 202167, has continuously evolved since and is divided into many sublineages68. Despite their genetic diversity, these sublineages display convergent evolution in the Spike protein (mutations independently acquired at the same positions), promoting the emergence of variants that are capable of evading population immunity69,70,71. Figure 3 depicts the spike proteins of selected Omicron sublineages, the index virus, and the pre-omicron VOCs, highlighting the variant-specific spike amino acid changes.

The receptor-binding domain (RBD) and N-terminal domain (NTD) locations are indicated. Red spots indicate non-synonymous mutations calculated with a mutation frequency of over 70% in genomes of the corresponding lineage based on 8.6 million GISAID samples (see Supplementary Text T1 for details). Here, the 3D structure of the S protein (PDB: 7SBO) was plotted using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC.

By the end of 2022, the spreading dynamics of sublineages with new escape properties varied from region to region, reflecting the increasing complexity of the global immunity landscape. For example, the closely related Omicron-BA.4/BA.5 variants initially displayed slower spread in many European countries than in South Africa. A plausible explanation is that, unlike in South Africa, many people in Europe were infected with Omicron-BA.2 before the arrival of BA.4/5. Omicron-BA.2 displays high antigenic similarity with Omicron-BA.4/5. Therefore, after a pronounced Omicron-BA.2 wave, it can be assumed that population immunity against Omicron-BA.4/BA.5 reaches high levels. Thus, the course of waves with new (sub-)variants depends on which variants have dominated the preceding waves at a given time in a given region61.

While the Spike protein is arguably most relevant to the adaptive evolution of the virus in humans, mutations in other genomic regions are also selected (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S1). They may affect, for example, non-structural proteins such as NSP6, potentially counteracting the host’s innate immune response. However, the functional effects of these mutations remain to be fully characterized29,72,73,74.

Recombination

Recombination is the exchange of genetic material between genomes, for example, of different SARS-CoV-2 variants. This process is crucial to the evolution of the virus as it can increase genetic variation and thus lead to novel selection advantages. Recombination events occur quite frequently in betacoronaviruses75,76,77,78,79. A prerequisite is a simultaneous infection event of a host cell with two different viral variants. During replication, portions of the parental genetic material of the two variants combine with each other so that the progeny viruses carry hybrid genomes. Betacoronavirus recombinants may differ in phenotype from their parental lineages and may outperform them in terms of replicative fitness80. Therefore, detection of recombinant variants requires close monitoring in SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance. At the same time, it also poses technical challenges: samples with a true recombinant virus must be distinguished from patient material containing coinfecting viruses that have not recombined, from contaminations, and from sequencing or genome reconstruction errors81.

Because recombination requires coinfection of the same cell with two genetically distinct viruses, it is most likely to occur when multiple viral lineages co-circulate and when viral prevalence is high78. Given the ongoing genetic diversification of SARS-CoV-2 and its wide transmission in the population, the discovery of recombinant viruses has become increasingly common79,82. This is consistent with the co-circulation of different viral lineages (e.g., leading to recombination between Delta and Omicron, or different Omicron-BA.2 sublineages) and the intensity of genomic surveillance that enables such detections. Pangolin lineages starting with the letter “X” have been established for several recombinants and their offspring, for example, XD (Delta x Omicron-BA.1), XE (BA.1 x Omicron-BA.2), XF (Delta x Omicron-BA.1), and XBB (Omicron-BJ.1 x Omicron-BA.2.75*). However, in the Pangolin system each letter combination is limited to three virus generations, after which a new letter combination is assigned to subsequent descendant lineages32. Because letter selection is random and based on availability, tracing the relationships between lineages and sublineages can be complicated.

Chronology of variant evolution

Low diversity and one adaptive change

The first mutation with a clear impact on the epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 was an amino acid substitution in the spike protein (S) [S:D614G; i.e., aspartic acid (D) in position 614 is substituted by glycine (G)]. Viral variants harboring the D614G substitution were rare at the onset of the pandemic but expanded rapidly in early 2020, becoming globally dominant by March 202058 (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Figs. S1, S2). It was initially debated whether this sharp increase was due to a fitness advantage of 614 G variants, leading to their natural selection, or to a founder effect, where 614 G variants initiated, by sheer chance, most transmissions in multiple locations44,83. Subsequent comprehensive studies demonstrated an intrinsic transmission advantage, i.e., that the D614G substitution represented indeed an adaptive change that was naturally selected (see Box 1 for details and references). In January 2025, S:D614G was present in 99.2% of sequenced viruses in the international GISAID data.

Rise of the VOCs

Apart from the expansion of D614G, little sequence diversity and evolution were observed during the first year of the pandemic (Fig. 3). This was partly due to limited sequencing efforts, resulting in undersampling (Supplementary Fig. S3), but also because at that time a broad range of public health measures was in place to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 through unvaccinated populations worldwide, resulting in overall low case numbers40,44,84,85,86. However, as cases rose and genomic surveillance efforts were increased at the end of 2021, several virus variants displaying high sequence divergence and clear signals of an epidemiologic growth advantage emerged. The WHO coined the term Variant of Concern (VOC) in 2020, then defined as a virus variant with altered phenotype characteristics demonstrated to adversely affect epidemiology (especially transmissibility), clinical presentation (especially pathogenicity), or the effectiveness of countermeasures such as diagnostics, vaccines, or therapeutics87.

The first VOCs to emerge were B.1.1.7 (later designated as Alpha), B.1.351 (Beta), and P.1 (Gamma). These variants were initially termed 501Y.V1, 501Y.V2, and 501Y.V3 because they shared the S:N501Y substitution, which increases affinity to the ACE-2 receptor, thereby enhancing viral fitness88,89,90,91. Alpha displayed intrinsic higher transmissibility, Beta and Gamma were immune evasive. The spread of Beta and Gamma remained largely constrained to world regions that had seen high transmission levels during the first year of the pandemic92,93,94. There, the ability to evade the broad population immunity established through rampant infections turned out to be an evolutionary advantage for SARS-CoV-2, opening the evolutionary niche of reinfection44. In many other world regions, Alpha, with a reproduction number exceeding that of the index virus by 50-100%95, quickly became the predominant variant, driving a major surge of infections, severe illness, and death96,97,98,99,100.

In 2021, Alpha was displaced by Delta, the fourth variant declared a VOC, which emerged in India. With an R0 of 6-7101, Delta was intrinsically more transmissible than Alpha. The S:L452R, T478K, and P681R substitutions, which influence the affinity and cleavability of the spike, contributed to Delta’s increased transmissibility (see Box 2). In addition, this VOC was moderately immune evasive, transmitting efficiently through hosts that had been previously infected. Delta’s higher replication rates and more pronounced capacity to induce syncytium formation in airway cells translated to greater severity, increasing hospitalization and ICU admission rates. Delta became the dominant variant worldwide in June 2021 (Fig. 2A). Notably, the national vaccination campaigns in some countries, such as Germany, contributed substantially to decelerating the nascent Delta wave emerging in the summer of 202159.

Emergence and dominance of Omicron marked a watershed moment in the pandemic

At the end of 2021, the emergence of a new lineage prompted a swift, global response, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of the genomic surveillance systems that had been implemented during the pandemic. The variant B.1.1.529, subsequently designated as Omicron, rapidly increased in the South African genome surveillance, a piece of information immediately shared with public health agencies worldwide67. Due to the new variant’s concerning constellation of mutations and the pronounced growth (transmission) advantage observed in a country with a high level of population immunity, it was quickly declared as a new VOC102, prompting increased surveillance measures and risk assessment studies worldwide. This facilitated the rapid accumulation and synthesis of epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory experimental data that enabled a comprehensive assessment of the growth advantage of Omicron and the mechanisms underpinning it. Neutralization assays showed that the immune evasion displayed by Omicron was profound (albeit not complete), and its magnitude resembled an antigenic shift in the risk assessment framework of influenza viruses103,104,105,106,107. Consistent with these wet-lab data, integrated genomic and epidemiologic surveillance data demonstrated a propensity for infection of immunologically experienced individuals who had either been vaccinated or previously infected108,109. Moreover, high-validity tissue culture models indicated that Omicron had altered its host cell tropism to infect cells in the upper respiratory tract preferentially, enabling intrinsically more efficient person-to-person transmission63,110. Over the next months, it became gradually apparent that clinical, epidemiological, and genomic data lined up with these ex vivo data, at least for immunologically healthy and vaccinated adults. Omicron infections were associated with lower severity than infections with the previous VOCs. Although case counts reached record levels due to the numerous transmissions, ICU admissions and deaths did not exceed the levels that many countries experienced during the preceding Delta waves. While efficient suppression of Omicron transmissions is possible and has been demonstrated, e.g., in health care settings111,112, the reports on milder illness, the increasing vaccination rates, the overall pandemic fatigue, and the perception that containment of Omicron was not feasible led several countries to ease public health restrictions, often at the peak of the first Omicron wave. Healthcare systems in those countries were strained severely but were not overwhelmed and many countries transitioned to “living with COVID” mitigation policies. Thus, the emergence of Omicron may be viewed as a watershed moment. While mitigation policies may imply the absence of any transmission control, several measures aimed to curb the spread of COVID-19 were maintained (i.e., “vaccine plus” strategies), based on the long-term morbidity associated with COVID-19, the unknown impact of repeated SARS-CoV-2 infections, and the fact that elderly and immunologically compromised individuals remain vulnerable to severe acute illness.

The Omicron complex

Omicron became globally dominant (frequency > 50% on GISAID) in January 2022 and has since then effectively displaced all other lineages. BA.2 was the first Omicron sublineage to predominate worldwide. BA.4 and BA.5 have identical S-Proteins that, relative to BA.2, contain three amino acid changes (L452R, F486V, and R493Q) and one deletion (del 69-70). L452R, F486V, and del 69-70 enhance infectivity while L452R and F486V increase resistance to neutralizing antibodies. R493Q, a reversion, is thought to restore receptor affinity which is compromised by F486V in some experimental models. The combination of these mutations led to an effective transmission advantage for BA.5, which became globally dominant in the 2022 summer113,114,115.

The BA.5 wave was succeeded by a “variant soup” of co-circulating Omicron sublineages, with regional differences in prevalence. These sublineages convergently acquired mutations at key residues in the spike receptor-binding domain (RBD), including R346, L452, N460, and F486. Mutations like L452R and F486S enhanced immune evasion, including resistance to monoclonal antibodies such as Bebtelovimab and Tixagevimab, while R346T and N460K improved ACE2 binding and infectivity113,115,116,117,118,119. Thus, by altering the antigenicity and ACE2 affinity of the spike, these adaptations increased the effective fitness (Rᴇ) of Omicron sublineages. Among them, BQ.1.1 and XBB emerged as the fittest, co-circulating globally until the end of 2022, when BQ.1.1 was outcompeted by XBB.1.5. Compared to its parental XBB lineage, XBB.1.5 carries the F486P substitution, which confers similar immune evasion and increased ACE2 affinity82,115,120. Further information on Omicron sublineages that emerged later is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Over 56% of SARS-CoV-2 lineages and sublineages with sequence data available on GISAID (accessed January 29, 2025) descend from the parental Omicron lineages BA.1, BA.2, BA.3, BA.4, and BA.5 (including their sublineages), constituting the Omicron complex. Lineages within the Omicron complex continue to genetically diversify in an incremental adaptive process marked by convergent evolution of advantageous mutations. Many of these mutations are located on the spike and enable escape from the humoral immunity induced by previous variants, including earlier Omicron variants70. This contrasts the “saltatory” evolution observed with the historic emergence of VOCs. On the other hand, SARS-CoV-2 is known to persistently replicate in individuals with chronic infection46,50,121,122. Moreover, Delta and other de-escalated VOCs continue to circulate in animal reservoirs123. Thus, highly divergent lineages may continue to evolve but cannot be immediately detected via genomic surveillance for some time. A conceivable scenario is that one such lineage acquires characteristics that enhance human-to-human transmission, giving rise to a new VOC.

Genomic surveillance in the context of public health activities

Genomic surveillance has played an essential role in tracking SARS-CoV-2 since the onset of the pandemic and enabled a deeper understanding of the virus’s spread and evolution, thus has been fundamental in shaping effective public health measures and interventions43,59,67,92,93,95,124,125,126,127,128. Over the pandemic, many countries implemented extensive testing and sequencing programs that facilitated the identification of cases and a high-resolution genomic surveillance both temporally and spatially. However, after WHO declared that COVID-19 is an established and ongoing health issue which no longer constitutes a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on 5th May 2023129, these activities have seen a noticeable decline. Medium-scale genomic surveillance systems often operate at a lower resolution, while effectively capturing essential aspects of the viral population dynamics and infection patterns. This can result in delayed detection of virus variants with unique phenotypes, primarily due to the limitations imposed by smaller sample sizes. Thus, the future intensity of SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance will be modified to a less comprehensive but flexible set up, aiming to balance the needs and costs of genomic surveillance against the burden of the disease. It is important to note and consider that the virus continues to evolve in a population with widespread immunity, often without causing severe illness130. However, accurately assessing the disease burden is challenging due to the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 and the factors influencing its spread44,62. The most effective surveillance integrates epidemiological and clinical patient data with virus’ genetic information in a timely manner. The genomic surveillance system still in place in Germany, operational since 2020, utilizes a nationwide network of laboratories (IMSSC2) and centralized sequencing at Robert Koch Institute; virus genomic data is to be complemented with clinical-epidemiological data provided by local health authorities59. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 is being integrated within the existing surveillance systems for acute respiratory infections with high public health impact (Influenza, RSV): Syndromic and virological surveillance is conducted through Germany’s national sentinel system, which covers both Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) and ambulatory Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI), providing a comprehensive view of acute respiratory illnesses85,131,132,133. These crucial surveillance instruments provide opportunities to correlate clinical symptoms or severity with different virus types and to identify and potentially isolate viruses with unusual phenotypic characteristics134. Thus, they are key in identifying and characterizing virus variants with distinctive traits, such as pronounced immune evasion, increased virulence, or reduced vaccine effectiveness. Facilitating prompt and focused research into the virulence and public health implications of newly emerging variants using these tools will be pivotal in guiding data-driven public health strategies. This includes making informed decisions about vaccine formulations and other intervention measures to effectively combat emerging viral threats and where such surveillance systems can make a strong contribution. These surveillance tools typically focus on a representative selection of symptomatic individuals. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided an opportunity to enhance these well-established monitoring systems with wastewater surveillance. Despite several experimental and bioinformatic challenges, wastewater surveillance is considered an overall promising complementary surveillance tool, as it provides virus information on asymptomatic infections and may enable early trend detection and population-scale monitoring135. However, this instrument does usually not allow for virus isolation or assessment of viral phenotypes. As a complementary system, wastewater surveillance represents a broad approach to track viral prevalence and trends across communities.

Variant risk assessment by integration of virological, clinical-epidemiological, and genomic data

For public health purposes, assessing the risk posed by a new variant is of the utmost importance.

Whenever a new variant shows evidence of faster spread, i.e., an epidemiological growth advantage, this may be due to viral characteristics that favor transmission, i.e., a true transmission advantage or chance136. The public health risk emanating from the variant requires careful evaluation, the extent of which depends on the certainty of the observed growth advantage36. In the first stage, risk assessment involves confirmation of faster spread in different geographic regions as well as bioinformatic analysis, especially of the spike region, for mutations that might affect transmission efficiency61. Sequence analyses should be complemented by laboratory experimental characterization of the new variant’s virological phenotype. These experiments, performed in selected in vitro and in vivo models, assess the new variant’s growth characteristics, immunoevasive properties, and pathogenicity (virulence) under tightly controlled conditions. In addition, high-throughput assays have been developed to define more precisely epitopes of neutralizing antibodies and quantify the phenotypic effects of virtually any mutation of the spike protein, including those not yet observed in circulating variants137,138. Another essential part of variant risk assessment are epidemiological analyses to assess the clinical severity of the associated illness, which, combined with the growth advantage estimate, help to evaluate the risk of healthcare systems being strained or even overwhelmed by the new variant. Risk assessment analyses are most accurate when they are based on integrated clinical and genomic data126,127,139,140.

Clinical presentation

Acute illness

Symptomatic acute SARS-CoV-2- infection manifests with nonspecific symptoms after an incubation period of 4.2 days on average for the Omicron variant which is shorter than for infections with the Delta variant141,142. While the phase of active virus replication and shedding in the respiratory tract is very short in most patients, severely immunocompromised patients may exhibit prolonged viral persistence143,144.

The clinical presentation varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic or mild upper respiratory symptoms (predominantly) to interstitial pneumonia, which may take a severe clinical course and be complicated by Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)145. Symptoms of a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection are non-specific (e.g. headache, fever and myalgia, sore throat, rhinitis) and are similar to other respiratory viral infections146,147. However, the leading symptoms appear to be somewhat related to the virus variant. For example, a sore throat is more likely observed in Omicron infection than in Delta infection141. A relatively specific COVID-19 symptom is an impairment of smell or taste148,149. However, depending on the study, there are often contradictory data about the association of this symptom with virus variants. While some studies report that changes in sense of smell and taste occurred more frequently with the Delta variant than with the Alpha variant, other studies suggest that this was a more typical symptom of the Alpha variant150,151,152. It seems that in addition to the increase in the frequency of sore throats, a decrease in smell or taste impairment is also typical in those infected with Omicron150,153. The correlation of headaches also appeared to decrease in studies with the evolution of the virus and was no longer significant with Omicron154,155,156. The proportion of asymptomatic infections and of non-severe COVID-19 cases is also reported to be significantly higher for Omicron than for Delta157; in addition to lower intrinsic virulence of Omicron, this trend may also be influenced by the generally higher population immunity present during the Omicron era.

However, all the aforementioned differences reported in some studies do not allow a reliable diagnosis of COVID-19 or even differentiation of virus variants based on the symptom constellation. The only way to identify a case with certainty is to test for specific antigens or RNA. To date, all variants have been detectable with the established diagnostic assays.

Severe COVID-19 manifests initially by cough and hypoxaemia due to interstitial pneumonia158 and may result in sepsis-like symptoms and organ failure. This is consistent with the widespread expression of the ACE2 receptor in numerous human tissues. SARS-CoV-2 can infect cells in various organ systems beyond the respiratory tract, resulting in a broad spectrum of sometimes severe extrapulmonary manifestations and complications159,160,161,162. Underlying pathomechanisms include: (i) cytolysis, i.e., direct damage to host cells by the replicating virus, (ii) a dysregulated, exuberant immune response that can lead to a life-threatening cytokine storm163, (iii) organ-specific inflammatory responses159,164,165,166,167, and (iv) endothelial damage which may be associated with dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin system and may cause, e.g., thrombo-embolic complications168,169. In addition to thromboembolic complications, other cardiovascular manifestations such as myocarditis, arrhythmias or myocardial infarction can also occur as a result of SARS-CoV-2 infection170,171,172. Acute kidney failure and several neurological manifestations such as stroke are also observed173,174,175,176,177. The involvement of other organ systems can lead to a complete picture of multi-organ failure and determine the outcome178,179.

During the initial phase of the pandemic, severe courses of COVID-19 were observed in a significant number of cases, even among young and previously healthy individuals, providing a rationale for implementing society-level measures to curb the spread of SARS-CoV-2. A meta-analysis showed that infections with the Delta variant had the highest severity. However, the hospitalization rate (but not the need for intensive care nor fatality rate) was higher for the Beta variant180.Currently, severe illness primarily affects individuals who are immunocompromised or have other predisposing conditions that put them at risk for severe illness, including advanced age181. This shift can be attributed to at least two factors: (i) most individuals have acquired immunity against the virus, protecting them not necessarily against asymptomatic or symptomatic infection but against severe clinical course182,183,184, and (ii) practically all infections are meanwhile caused by Omicron variants, generally considered of lower intrinsic pathogenicity than previously circulating variants27,110,185,186,187, even though this has been controversially discussed188,189,190,191. Thus, although widespread vaccination has successfully reduced the burden of severe COVID-19 disease in the general population, additional efforts will continuously be needed to protect the vulnerable.

A rare clinical manifestation observed in children following COVID-19 is Pediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome (PIMS), also known as Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C). This post-acute complication is associated with a dysregulated immune response after acute SARS-CoV-2-infection. It is hypothesized that this condition may be due to viral persistence leading to excessive activation of T-cells192,193. More recent data suggests that during the Omicron wave, both the frequency and severity of MIS-C have decreased, which may be due to the properties of Omicron or a potential protective effect of vaccination194,195,196,197.

Late complications

Long COVID and post-COVID condition

Most COVID-19 patients recover within several days to weeks after infection. However, a significant number of individuals report various persistent or new physical or neurocognitive symptoms, even after an initial recovery from the acute SARS-CoV-2-infection. These include fatigue, exercise intolerance, malaise, dyspnea, orthostatic dysregulation, and neurocognitive dysfunction198,199,200,201. These sequelae can be prolonged, experienced as severely debilitating, and negatively impact daily functioning and quality of life. If such symptoms persist or recur and cannot be otherwise explained, they are referred to as Long COVID (beginning four weeks after acute infection) and post-COVID-19 condition (beginning 12 weeks after acute infection)202.

During or after COVID-19, neurocognitive symptoms may develop, including “brain fog”, memory loss, impaired consciousness, and confusion (so-called “neuro-COVID”)203,204,205,206. Whether these clinical sequelae are related to the radiographically observed structural brain changes observed after COVID-19207,208,209 has not yet been conclusively determined.

The available data may indicate that infection with the Omicron variant leads to fewer long-lasting COVID symptoms compared to earlier variants. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the decline in the incidence of long-term effects of COVID-19 in subsequent SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the increase in pre-existing immunity in the population over the course of the pandemic or changes in the pathogenicity of the virus210,211. The influence of reinfection as well as the vaccination status and timing must also be considered when interpreting the data210,211. However, the risk of post-COVID syndrome remains significant even in vaccinated individuals who have contracted SARS-CoV-2 in the Omicron era. Fatigue appears to be the most common post-COVID-19 symptom regardless of the SARS-CoV-2 variant212.

Other long-term sequelae

In addition, there is evidence that organ-specific complications213 and new-onset chronic non-communicable diseases214 may occur as long-term consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection, even in individuals who were vaccinated and/or did not experience severe illness214,215,216,217. Emerging data suggest an increased risk for cardiovascular events, such as stroke, heart attack, arrhythmia, myocarditis, and heart failure218, as well as diabetes219,220, renal failure221, and psychiatric disorders222,223. The risk of postacute COVID-19 sequelae has been shown to be substantial even among vaccinated individuals who infected during the period of Omicron predominance211.

Relationship of viral mutations to clinical presentation and severity

Pathogen genetic variation can impact virulence, which is an important determinant of clinical severity. Due to the significant influence of many other factors, including host immunity / vaccination status, age, and individual predisposition including the vascular system, it is challenging to assess pathogen virulence (or changes thereof) based on clinical signs and severity even when disease severity may be compared for SARS-CoV-2 variants co-circulating in a given population during the same time period72. It is similarly difficult, if not more so, to assess the impact of specific mutations on SARS-CoV-2 virulence based on severity data alone. Nevertheless, several amino acid substitutions that may affect acute disease severity have been identified based on clinical-epidemiological evidence.

A significant correlation with a higher viral load was found for the substitutions R203K and G204R in the N protein and S:D614G. However, although higher viral load is considered predictive of morbidity and mortality224,225, a statistically significant association could not be proven for these mutations226. A 382-nucleotide deletion that truncates open reading frame 7b (ORF7b) and eliminates ORF8 correlates with reduced clinical severity227. Notably, any ORF8 knockout appears to be associated with milder illness228. The P25L substitution in ORF3a has the potential to contribute to immune evasion and enhanced virulence, and has been linked to higher case fatality rates226. For the nt14408 mutation in RdRp, a higher single-nucleotide variant frequency was observed in severe cases226. The 11,083 G > U mutation has been associated with asymptomatic cases226,227. For mutations in ORF1ab and in the N gene, an association with asymptomatic outcomes has been described, found to be particularly strong for the co-occurring ORF1ab substitutions R6997P and V30L226. For mutations in NSP6, as well as other nonstructural proteins, an association with adverse clinical outcomes has been described229.

The differences between the variants in terms of acute clinical presentation and severity have prompted numerous investigations using in vitro and animal models to elucidate the role of specific mutations. The severe disease outcomes of the Delta variant are attributed to its enhanced replicative capacity and increased syncytium formation (fusogenicity) in the lung. Key mutations driving these features have been identified in the spike protein and include the L452R and P681R substitutions230 (see Box 2). In contrast, the reduced pathogenicity of Omicron variants is explained by their propensity for upper (rather than lower) respiratory tract replication and diminished syncytium formation; these features have been linked primarily to the Omicron spike. Mutations near the furin cleavage site (P681H, H655Y, and N679K) and the S1 C-terminus (T547K and H655Y) render the Omicron spike less fusogenic and less efficiently cleaved, suggesting it is a key determinant of the attenuated phenotype28,110,231,232. While most investigations have focused on spike protein mutations, a growing body of evidence suggests that non-spike mutations also impact SARS-CoV-2 virulence226,227,229, including animal experimental data indicating that mutations in NSP 14, envelope, and membrane proteins reduce the neuropathogenicity of Omicron233. NSP6 mutations modulate Omicron virulence74,231; and ORF8 mutations modulate lung inflammation as well as disease severity231,234.

With respect to the symptomatology of Long COVID, no single SARS-CoV-2 mutation has been definitively tied to specific Long COVID manifestations. However, some but not all studies indicate that variant-specific trends exist (reviewed in ref. 235): Omicron variants have been associated more frequently with gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal complaints and less frequently with cardiopulmonary and neuropsychiatric symptoms than pre-Omicron variants, although these findings are not entirely consistent in the literature235,236,237,238,239,240.

Antiviral therapeutic options and resistance

Protease and polymerase inhibitors are employed as early direct antiviral therapy. Monoclonal antibodies, widely used for antiviral therapy during the first two years of the pandemic, currently have limited role in the treatment and prevention of COVID-19. This is because all viruses in circulation are Omicron variants, which are known for their significant immune evasion leading to decrease and even complete loss of the effectiveness of the licensed monoclonal antibodies (all of which were developed based on pre-Omicron variants)104,241,242,243,244,245. For pre-exposure prophylaxis, a new antibody has been approved, which is effective against XBB.1.5, XBB.1.16, XBB.2.3 and BA.2.86, but not against VOC carrying the F456L substitution246. In addition to antivirals, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agents such as corticosteroids and IL-6 receptor antagonists, are available for the treatment of moderate to severe COVID-19 pneumonia requiring respiratory support.

Direct antiviral therapy inhibits viral replication and should be administered in the early phase of infection, also known as the “replicative phase”. Unlike monoclonal antibodies, which target the viral spike protein, these antivirals are not impacted by the presence of Spike gene mutations. However, antiviral resistance may evolve during treatment: Random transcription errors during viral RNA synthesis may result in inhibitor-specific point mutations in the therapeutic target proteins, which are selected if the virus replicates under continuous therapeutic pressure, thus giving rise to antiviral-resistant variants. Notably, a single amino acid substitution may suffice to render the virus less sensitive or resistant to an antiviral. As of today, four years after the first antiviral compounds were approved for COVID-19 therapy, resistance mutations are rare, occur mostly in laboratory settings, and have a worldwide prevalence of less than 1%247,248,249. Box 5 provides detailed information on the direct antiviral therapeutics currently approved for treating COVID-19.

Conclusions and perspectives

This article summarizes relevant data accumulated during the first four years (2020 – 2023) of the COVID-19 pandemic in the context of a “Working Group for Diagnostic and Evolution” on the causative agent, SARS-CoV-2, at Robert Koch-Institute, the German Public Health Institute. This has been done with the aim to underline the importance of virologic surveillance under the public health perspective and with respect to pandemic preparedness in future. The insights and data presented, while rooted in the German context, reflect broader virological and public health principles that are applicable across countries. The knowledge gained from these experiences can inform global strategies for surveillance and pandemic preparedness.

Thanks to substantial advances in sequencing of infective agents and the expansion of global data sharing initiatives, the scientific community has been able to detect and track the evolution of a newly introduced respiratory virus at unprecedented resolution and speed. However, it is still not possible to make reliable predictions about the long-term evolution of a new agent like SARS-CoV-2, which may continue to follow drift-like changes within the Omicron complex, but which could also be impacted by shift-like events, leading to new Variants of Concern (VOCs) that emerge for example from persistently infected humans or animal reservoirs. The genetic diversity of viruses, and hence also SARS-CoV-2, increases with the number of infections in both human and animal populations. This heightened genetic diversity benefits the virus, enabling rapid adaptation and the emergence of VOCs. Significant shifts resulting in VOCs have historically originated from chronically infected, immunocompromised human hosts44,49,121,250,251. Whether future SARS-CoV-2 VOCs will be derived primarily from Omicron or from phylogenetically divergent lineages, which may continue to evolve not only in animal reservoirs but also, potentially, in chronically infected humans, is currently uncertain44,62. The virulence of such future VOCs can also not be predicted62. Notably, it does not necessarily correlate with transmissibility, which is the virus’ key driver of positive selection.

As the virus continues to evolve, ongoing surveillance and research are crucial to understanding the impact of both spike and non-spike mutations on disease severity and clinical presentation. Research is ongoing to determine the impact of non-spike mutations on viral phenotype and pathogenicity. These mutations may affect viral replication, evasion of the innate immune response, and tissue tropism, potentially influencing disease outcomes. The specific mechanisms by which many of these mutations affect pathogenicity are still being investigated. Identification of key mutations linked to virologic properties will facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of infection and aid in the development of antiviral treatments252.

Currently, SARS-CoV-2 circulation appears to trigger epidemiological surges at a higher frequency than that of influenza waves. This is likely due to rapid viral evolution and antigenic drift, indicating that SARS-CoV-2 has not yet evolved a clear pattern of seasonality. It is uncertain if and when the frequency of these waves will decrease in the future as population immunity becomes broader and more robust. It is similarly unclear whether or when the S protein of the virus will reach its evolutionary limits and constraints.

Therefore, it remains challenging to predict the evolutionary trajectory of SARS-CoV-2, including its potential for rapid adaptation and the emergence of new VOCs. Continuous in-depth surveillance that integrates genomic, clinical, epidemiologic, and virologic data obtained from various sources, including humans and animals as well as wastewater samples, enabling a fact-based risk assessment, is a public health imperative, which may inform timely interventions and the adaptation of vaccine formulation.

Data availability

DESH genome identifiers, intermediate data files, and scripts for visualizations are available at the Open Science Framework under https://osf.io/9r4ws. All used GISAID data are available through the GISAID identifier “EPI_SET_240415ce” and the corresponding https://doi.org/10.55876/gis8.240415ce. A corresponding Supplementary Table is provided (Supplementary Table S2).

Change history

30 December 2025

In the original version of the article, the affiliations ‘Genome Competence Center (MF1), Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany’ and ‘Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany’ were listed twice. This has now been corrected in the article.

References

Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 536–544 (2020). The Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, a specialized panel of experts dedicated to the classification and nomenclature of coronaviruses designated the new coronavirus responsible for COVID-19 as SARS-CoV-2.

Graham, R. L. & Baric, R. S. Recombination, reservoirs, and the modular spike: mechanisms of coronavirus cross-species transmission. J. Virol. 84, 3134–3146 (2010).

Fehr, A. R. & Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 1282, 1–23 (2015).

Cui, J., Li, F. & Shi, Z. L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 181–192 (2019).

Laue, M. et al. Morphometry of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 particles in ultrathin plastic sections of infected Vero cell cultures. Sci. Rep. 11, 3515 (2021).

Bai, C., Zhong, Q. & Gao, G. F. Overview of SARS-CoV-2 genome-encoded proteins. Sci. China Life Sci. 65, 280–294 (2022).

Steiner, S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 biology and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 206–225 (2024).

Khoury, D. S. et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 27, 1205–1211 (2021). First study demonstrating that in vitro neutralization levels are significantly correlated with immune protection against SARS-CoV-2, and thus allow to predict the efficacy of vaccines as they are being developed.

Enjuanes, L. et al. Development of protection against coronavirus induced diseases. A review. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 380, 197–211 (1995).

Liu, L. et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies against multiple epitopes on SARS-CoV-2 spike. Nature 584, 450–456 (2020). Landmark study reporting the isolation of multiple SARS-CoV-2-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies and revealing the epitopes of nineteen potent mAbs with potential for clinical development as therapeutic or prophylactic agents.

Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 403–416 (2021).

Polack, F. P. et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2603–2615 (2020).

Heath, P. T. et al. Safety and efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1172–1183 (2021).

Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271–280.e278 (2020).

Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 3–20 (2022). Review on the structural and cellular mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into host cells, focusing on the spike protein’s interactions with the ACE2 receptor, the roles of various proteases, and the implications for vaccines, antibodies, and other therapeutics.

Sungnak, W. et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat. Med. 26, 681–687 (2020).

Zou, X. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front. Med. 14, 185–192 (2020).

Hikmet, F. et al. The protein expression profile of ACE2 in human tissues. Mol. Syst. Biol. 16, e9610 (2020).

Varga, Z. et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 395, 1417–1418 (2020).

Hamming, I. et al. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 203, 631–637 (2004).

Ziegler, C. G. K. et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell 181, 1016–1035.e1019 (2020).

Puelles, V. G. et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 590–592 (2020).

Tavazzi, G. et al. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur. J. Heart Fail 22, 911–915 (2020).

Xiao, F. et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology 158, 1831–1833.e1833 (2020).

Chertow, D. e. a. SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence throughout the human body and brain. Research Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1139035/v1 (2022).

Stein, S. R. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence in the human body and brain at autopsy. Nature 612, 758–763 (2022). A study involving complete autopsies of 44 COVID-19 patients, revealing wide distribution of SARS-CoV-2 across the body, including the brain, with evidence of viral persistence up to 230 days post-symptom onset, despite minimal inflammation or direct viral damage outside the respiratory tract.

Meng, B. et al. Altered TMPRSS2 usage by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron impacts tropism and fusogenicity. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04474-x (2022).

Qu, P. et al. Determinants and mechanisms of the low fusogenicity and high dependence on endosomal entry of Omicron subvariants. mBio 14, e0317622 (2023).

Kistler, K. E., Huddleston, J. & Bedford, T. Rapid and parallel adaptive mutations in spike S1 drive clade success in SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe 30, 545–555.e544 (2022). This study revealed that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (in particular the S1 subunit) is the primary focus of rapid adaptive evolution, with a high mutation rate suggesting significant antigenic drift, and identified other important mutations, particularly in the Nsp6 protein.

Neher, R. A. Contributions of adaptation and purifying selection to SARS-CoV-2 evolution. Virus Evol. 8, veac113 (2022).

Hadfield, J. et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 34, 4121–4123 (2018). Nextstrain provides a comprehensive platform combining a viral genome database, bioinformatics tools, and interactive visualizations for real-time tracking of pathogen evolution and spread, integrating diverse data types for public health use: thus being of utmost importance for tracking SARS-CoV-2 evolution throughout the pandemic.

Rambaut, A. et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 1403–1407 (2020). Introduction of the Pangolin nomenclature, a rational and dynamic naming system for SARS-CoV-2 that focuses on active and spreading lineages, which is being used by research groups and public health agencies worldwide.

Harvey, W. T. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 409–424 (2021).

Alm, E. et al. Geographical and temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 clades in the WHO European Region, January to June 2020. Euro Surveill. 25 https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.32.2001410 (2020).

World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ (2021).

World Health Organization. Updated working definitions and primary actions for SARS-CoV-2 variants. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/updated-working-definitions-and-primary-actions-for--sars-cov-2-variants (2023).

Oh, D.-Y. et al. SARS-CoV-2-Varianten: Evolution im Zeitraffer. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 118, A-460/–B-388 (2021).

World Health Organization. WHO Team Emergency Response (WRE), COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update (2021).

Lythgoe, K. A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 within-host diversity and transmission. Science 372 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg0821 (2021).

van der Toorn, W. et al. An intra-host SARS-CoV-2 dynamics model to assess testing and quarantine strategies for incoming travelers, contact management, and de-isolation. Patterns2, 100262 (2021).

Baumgarte, S. et al. Investigation of a limited but explosive COVID-19 outbreak in a German secondary school. Viruses 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/v14010087 (2022).

Scholl, M. et al. Bus riding as amplification mechanism for SARS-CoV-2 transmission, Germany, 2021(1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 30, 711–720 (2024).

Gu, H. et al. Genomic epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 under an elimination strategy in Hong Kong. Nat. Commun. 13, 736 (2022).

Markov, P. V. et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 361–379 (2023). Comprehensive review of SARS-CoV-2 evolution with a focus on mechanisms generating genetic variation while also discussing future evolutionary scenarios.

Choi, B. et al. Persistence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an Immunocompromised Host. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2291–2293 (2020).

Chaguza, C. et al. Accelerated SARS-CoV-2 intrahost evolution leading to distinct genotypes during chronic infection. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 100943 (2023).

Gonzalez-Reiche, A. S. et al. Sequential intrahost evolution and onward transmission of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Commun. 14, 3235 (2023).

Lustig, G. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunosuppression evolves sub-lineages which independently accumulate neutralization escape mutations. Virus Evol. 10, vead075 (2024).

Ghafari, M., Liu, Q., Dhillon, A., Katzourakis, A. & Weissman, D. B. Investigating the evolutionary origins of the first three SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Front. Virol. 2 https://doi.org/10.3389/fviro.2022.942555 (2022).

Harari, S. et al. Drivers of adaptive evolution during chronic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Med. 28, 1501–1508 (2022).

Marques, A. D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution during prolonged infection in immunocompromised patients. mBio 15, e0011024 (2024).

Ghafari, M. et al. Prevalence of persistent SARS-CoV-2 in a large community surveillance study. Nature 626, 1094–1101 (2024).

Machkovech, H. M. et al. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection: significance and implications. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00815-0 (2024). Review on persistent SARS-CoV-2 infections, which highlights that their potential of going unrecognized, of contributing to tissue reservoirs thereby requiring new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, and of generating new virus variants that can evade immunity poses significant clinical and public health challenges.

Khare, S. et al. GISAID’s role in pandemic response. China CDC Wkly. 3, 1049–1051 (2021).

Shu, Y. & McCauley, J. GISAID: global initiative on sharing all influenza data—from vision to reality. Euro Surveill. 22 https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.13.30494 (2017).

Elbe, S. & Buckland-Merrett, G. Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID’s innovative contribution to global health. Glob. Chall. 1, 33–46 (2017).

Focosi, D., Maggi, F., McConnell, S. & Casadevall, A. Very low levels of remdesivir resistance in SARS-COV-2 genomes after 18 months of massive usage during the COVID19 pandemic: a GISAID exploratory analysis. Antivir. Res. 198, 105247 (2022).

Korber, B. et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell 182, 812–827.e819 (2020). This paper noted for the first time that the SARS-CoV-2 variant with the Spike protein change D614G became globally dominant, likely due to a fitness advantage; it underscored the need for ongoing genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2.

Oh, D. Y. et al. Advancing precision vaccinology by molecular and genomic surveillance of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in Germany, 2021. Clin. Infect. Dis. 75, S110–S120 (2022).

Robert Koch-Institut. SARS-CoV-2 Sequenzdaten aus Deutschland (2023-06-16). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8046538 (2023).

Raharinirina, N. A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution on a dynamic immune landscape. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08477-8 (2025). This paper presents a mechanistic model predicting SARS-CoV-2 variant dynamics based on the virus’s evolution to evade antibody-mediated neutralization in a population with varied immune histories due to global inequalities in vaccine distribution and infection-prevention measures.

Telenti, A., Hodcroft, E. B. & Robertson, D. L. The evolution and biology of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a041390 (2022).

Peacock, T. P. et al. The SARS-CoV-2 variant, Omicron, shows rapid replication in human primary nasal epithelial cultures and efficiently uses the endosomal route of entry. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.31.474653 (2022).

Magnus, C. L. et al. Targeted escape of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro from monoclonal antibody S309, the precursor of sotrovimab. Front. Immunol. 13, 966236 (2022).

Arruda, H. R. S. et al. Conformational stability of SARS-CoV-2 glycoprotein spike variants. iScience 26, 105696 (2023).

Gobeil, S. M. et al. Effect of natural mutations of SARS-CoV-2 on spike structure, conformation, and antigenicity. Science 373 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi6226 (2021).

Viana, R. et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature 603, 679–686 (2022). First description of the genomic profile and early transmission dynamics of the Omicron variant.

Roemer, C. et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution in the Omicron era. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 1952–1959 (2023).

Cao, Y. et al. Imprinted SARS-CoV-2 humoral immunity induces convergent Omicron RBD evolution. Nature 614, 521–529 (2023).

Cao, Y. et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron infection. Nature 608, 593–602 (2022).

Ito, J. et al. Convergent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants leading to the emergence of BQ.1.1 variant. Nat. Commun. 14, 2671 (2023).

Carabelli, A. M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 162–177 (2023).

Thorne, L. G. et al. Evolution of enhanced innate immune evasion by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 602, 487–495 (2022).

Bills, C. J. et al. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 variant nsp6 enhance type-I interferon antagonism. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 12, 2209208 (2023).

Bobay, L. M., O’Donnell, A. C. & Ochman, H. Recombination events are concentrated in the spike protein region of Betacoronaviruses. PLoS Genet. 16, e1009272 (2020).

Corman, V. M. et al. Rooting the phylogenetic tree of middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus by characterization of a conspecific virus from an African bat. J. Virol. 88, 11297–11303 (2014).

Garvin, M. R. et al. Rapid expansion of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern is a result of adaptive epistasis. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.03.454981 (2021).

Jackson, B. et al. Generation and transmission of interlineage recombinants in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Cell 184, 5179–5188.e5178 (2021).

Bolze, A. et al. Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron co-infections and recombination. Med 3, 848–859.e844 (2022).

Schroeder, S. et al. Functional comparison of MERS-coronavirus lineages reveals increased replicative fitness of the recombinant lineage 5. Nat. Commun. 12, 5324 (2021).

Kreier, F. Deltacron: the story of the variant that wasn’t. Nature 602, 19 (2022).

Tamura, T. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 XBB variant derived from recombination of two Omicron subvariants. Nat. Commun. 14, 2800 (2023).

Lauring, A. S. & Hodcroft, E. B. Genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2-what do they mean?. JAMA 325, 529–531 (2021).

Oh, D. Y., Bottcher, S., Kroger, S. & von Kleist, M. [SARS-CoV-2 transmission routes and implications for self- and non-self-protection]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 64, 1050–1057 (2021).

Oh, D. Y. et al. Trends in respiratory virus circulation following COVID-19-targeted nonpharmaceutical interventions in Germany, January - September 2020: analysis of national surveillance data. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 6, 100112 (2021).

von Kleist, M. et al. Abwägung der Dauer von Quarantäne und Isolierung bei COVID-19. Epid. Bull. 39, 3–11 (2020).

World Health Organization. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update (Suppl. 25 February 2021), Special Edition: Proposed working definitions of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Interest and Variants of Concern. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-weekly-epidemiological-update (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. The N501Y spike substitution enhances SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission. Nature 602, 294–299 (2022).

Prüß, B. M. Variants of SARS CoV-2: mutations, transmissibility, virulence, drug resistance, and antibody/vaccine sensitivity. Front. Biosci.27, 65 (2022).

Starr, T. N. et al. Deep mutational scanning of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain reveals constraints on folding and ACE2 binding. Cell 182, 1295–1310.e1220 (2020). Comprehensive mutational analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD) reveals that while most mutations reduce protein expression and ACE2 binding, some enhance ACE2 affinity, including at critical interface residues, offering insights for vaccine and therapeutic design, though these affinity-enhancing mutations have not been selected in current pandemic strains.

Zahradnik, J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant prediction and antiviral drug design are enabled by RBD in vitro evolution. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 1188–1198 (2021).

Tegally, H. et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature 592, 438–443 (2021).

Faria, N. R. et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abh2644 (2021).

Sabino, E. C. et al. Resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil, despite high seroprevalence. Lancet 397, 452–455 (2021).

Volz, E. et al. Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature 593, 266–269 (2021).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid increase of a SARS-CoV-2 variant with multiple spike protein mutations observed in the United Kingdom. ECDC Threat Assessment Brief (2020).

Davies, N. G. et al. Increased mortality in community-tested cases of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7. Nature 593, 270–274 (2021). Clinical-epidemiological analysis indicating that the Alpha variant is associated with a significantly higher risk of death, suggesting it may cause more severe illness.

Challen, R. et al. Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study. BMJ 372, n579 (2021).

Paul, P. et al. Genomic surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating in the United States, December 2020-May 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 70, 846–850 (2021).

Dhanasekaran, V. et al. Air travel-related outbreak of multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants. J. Travel Med. 28 https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taab149 (2021).

Burki, T. K. Lifting of COVID-19 restrictions in the UK and the Delta variant. Lancet Respir. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00328-3 (2021).

World Health Organization. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern (2021).

Cele, S. et al. Omicron extensively but incompletely escapes Pfizer BNT162b2 neutralization. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04387-1 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04388-0 (2021).

Planas, D. et al. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04389-z (2021).

Schmidt, F. et al. Plasma neutralization properties of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2119641 (2021).

Rossler, A., Riepler, L., Bante, D., von Laer, D. & Kimpel, J. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant neutralization in serum from vaccinated and convalescent persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 698–700 (2022).

Collie, S., Champion, J., Moultrie, H., Bekker, L. G. & Gray, G. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 Vaccine against Omicron Variant in South Africa. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2119270 (2021).

Pulliam, J. R. C. et al. Increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection associated with emergence of Omicron in South Africa. Science 376, eabn4947 (2022).

Hui, K. P. Y. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant replication in human bronchus and lung ex vivo. Nature 603, 715–720 (2022).

Baker, M. A. et al. Rapid control of hospital-based severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Omicron clusters through daily testing and universal use of N95 respirators. Clin. Infect. Dis. 75, e296–e299 (2022).