Abstract

Background

Parkinson’s Disease diagnosis remains challenging due to subtle early brain changes. Deep learning approaches using brain scans may assist diagnosis, but optimal architectures remain unclear. This study applies Convolutional Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (ConvKANs), which use flexible mathematical functions for feature extraction, to classify Parkinson’s Disease from structural brain scans.

Methods

We implemented the first three-dimensional ConvKAN architecture for medical imaging and compared performance against established deep learning models, including Convolutional Neural Networks, Vision Transformers, and Graph Convolutional Networks. Three publicly available datasets containing brain scans from 142 participants (75 with Parkinson’s Disease, 67 healthy controls) were analyzed. Models were evaluated using both two-dimensional brain slices and complete three-dimensional volumes, with performance assessed through cross-validation and independent dataset testing.

Results

Here we show that two‑dimensional ConvKAN achieved an AUC of 0.973 for Parkinson’s‑disease detection, outperforming a pretrained ResNet (AUC 0.878, p = 0.047). On the early‑stage PPMI hold‑out set, the three‑dimensional variant generalised better than the two‑dimensional model (AUC 0.600 vs 0.378, p = 0.013). Furthermore, ConvKAN required 97% less training time than conventional CNNs while maintaining superior accuracy.

Conclusions

ConvKAN architectures offer promising improvements for Parkinson’s Disease detection from brain scans, particularly for early-stage cases where diagnosis is most challenging. The computational efficiency and strong performance across diverse datasets suggest potential for clinical implementation. These findings establish a framework for artificial intelligence-assisted diagnosis that could support earlier detection and intervention in Parkinson’s Disease.

Plain language summary

Parkinson’s disease affects millions of people worldwide, impacting movement, thinking, mood, and daily life. Doctors struggle to diagnose it early because brain changes are subtle. We tested whether artificial intelligence could detect Parkinson’s disease from brain scans. We applied a new type of AI model called ConvKAN, recently developed for image analysis, to brain imaging for the first time. We compared this approach against established AI methods including conventional neural networks, vision transformers, and graph-based models, testing both two-dimensional brain slices and complete three-dimensional brain volumes. Similarly to finding a melody in hours of noise, these models identify only the most important patterns that distinguish Parkinson’s disease. We evaluated all approaches using brain scans from 142 people. The ConvKAN model showed excellent ability to distinguish between patients and controls (achieving a score of 0.97 out of 1.0). By focusing on key patterns rather than processing everything, it worked 97% faster than conventional approaches while excelling at detecting early disease. This could help enable earlier diagnosis, when treatments may be more effective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, affecting over 10 million people worldwide1. Clinically, PD is characterized by motor symptoms such as tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia, as well as non-motor symptoms including cognitive impairment and depression2. The prevalence of PD increases with age, and as the global population ages, the burden of PD is expected to increase substantially.

Early and accurate diagnosis of PD remains challenging, as current diagnostic criteria rely on subjective clinical assessment of motor symptoms, which often emerge only after significant neurodegeneration has occurred3. Misdiagnosis rates can be as high as 25% in early stages, highlighting the need for objective biomarkers to support clinical decision-making4,5. While various imaging modalities have been explored, structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not part of any PD diagnostic criteria due to the subtle and heterogeneous nature of early brain changes6.

Deep learning has emerged as a powerful methodology for medical image analysis, demonstrating success across various domains, including neuroimaging7,8. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been widely applied to MRI analysis, using their ability to capture hierarchical features9. CNNs’ rigid structure may limit their ability to model non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data10.

Vision transformers (ViTs) have recently emerged as a powerful alternative to CNNs in computer vision tasks, demonstrating state-of-the-art performance across numerous benchmarks. By replacing convolutional operations with self-attention mechanisms, ViTs can capture long-range dependencies in images more effectively than traditional CNN architectures. In medical imaging, ViTs have shown promising results for tasks including tumor segmentation and disease classification, though their application to volumetric neuroimaging data remains underexplored, particularly in the context of PD detection using structural MRI.

Graph-based approaches have recently gained traction in the deep imaging community, with graph convolutional networks (GCNs) offering a framework for modeling the inherent structural relationships in medical imaging data, including in PD11. By representing an image or scan as a graph of interconnected nodes, GCNs can capture both local and global context, potentially overcoming some limitations of traditional CNN architectures12. However, the application of GCNs in neuroimaging is still an emerging field, with limited studies exploring their potential for PD classification.

The Kolmogorov–Arnold network (KAN), introduced earlier this year, represents a significant departure from traditional CNN architectures13. Based on the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem, KANs replace conventional weight matrices with learnable spline functions, offering enhanced flexibility in modeling complex, non-linear relationships.

Building upon the KAN framework, the convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold network (ConvKAN) was recently proposed as a fusion of KAN principles with convolutional architectures14. ConvKANs integrate spline-based functions into convolutional layers, combining the flexibility of KANs with the spatial invariance of CNNs. While ConvKANs have shown promising results in 2D image analysis tasks, their application to 3D imaging data, such as volumetric MRI scans, represents a previously unexplored step, to the best of our knowledge15.

The dimensionality of input data is another critical consideration in imaging analysis. Studies comparing 2D and 3D approaches have yielded mixed results, with some favoring slice-based methods for their computational efficiency and larger effective sample sizes, while others advocate for 3D analysis to capture spatial relationships and avoid information loss16,17. The relative performance of different architectures across 2D and 3D implementations also remains unclear, with few studies conducting comprehensive comparisons18.

To address these knowledge gaps, we present a comprehensive evaluation of deep learning architectures for MRI-based PD classification, with a focus on the novel application of ConvKANs (to the best of our knowledge). We compare the performance of ConvKANs, ViTs, CNNs, and GCNs across both 2D and 3D implementations, using multiple open-source datasets to assess within-dataset performance and cross-dataset generalizability. Pretrained convolutional architectures like ResNet and VGG have demonstrated strong performance across medical imaging tasks, offering transfer learning benefits from natural image domains. Furthermore, we introduce the first 3D implementation of ConvKANs, exploring their potential for volumetric MRI analysis.

By conducting this multi-cohort, comparative study, we aim to provide valuable insights into the optimal approach for deep learning-based PD diagnosis using structural MRI using multiple open-source datasets to assess within-dataset performance and cross-dataset generalizability, with rigorous subject-level evaluation methodologies. The identification of robust, generalizable models could pave the way for AI-assisted diagnostic tools, supporting early detection and intervention in PD.

Our results indicate that convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold networks (ConvKANs) deliver strong performance for MRI‑based Parkinson’s disease classification while remaining lightweight to train. On the PPMI cohort, the 2‑D ConvKAN reached an AUC of 0.973, exceeding the best conventional CNN (ResNet‑2D, 0.878; Cohen’s d ≈ 1.98, p = 0.047, though this did not survive FDR correction, q = 0.074) and the graph baseline (GNN‑2D, 0.849). When models were trained on the two external cohorts and evaluated on the early‑stage PPMI test set, the new 3‑D ConvKAN generalized best (AUC 0.600 vs. 0.378 for its 2‑D counterpart; |d| ≈ 2.47, p = 0.013, q = 0.145) and outperformed every other architecture. ConvKANs were also computationally frugal, completing training about 97 % faster than the ResNet yet matching or surpassing its accuracy. Our findings demonstrate that ConvKAN architectures provide superior performance for PD detection from structural MRI while offering significant computational advantages over existing deep learning approaches.

Methods

Dataset description

This study utilized three open-source MRI datasets: the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI), NEUROCON, and Tao Wu19,20.

The PPMI study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines after approval by local ethics committees at each of the 33 participating clinical sites across the United States, Europe, Israel, and Australia. The study was also approved by the Research Subjects Review Board at the University of Rochester, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. The PPMI study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT01141023). The NEUROCON dataset was collected with approval from the University Emergency Hospital Bucharest ethics committee in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, with all participants providing written informed consent.20 The Tao Wu dataset was collected with approval from the Institutional Review Board of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with written informed consent obtained from all participants prior to the experiment. As this study involved secondary analysis of publicly available, de-identified data, additional institutional review board approval was not required.

Each dataset included both Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients and age-matched healthy control subjects, with varying clinical characteristics across cohorts. The PPMI cohort consisted of newly diagnosed PD patients within two years of diagnosis, none of whom had started PD medication at the time of scanning. From the complete PPMI database, a subset of 59 participants was selected based on uniform T1-weighted MPRAGE acquisition parameters (TR/TE: 2300/2.98 ms, voxel size: 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm³) to ensure imaging protocol consistency.

The NEUROCON (n = 43) and Tao Wu (n = 40) datasets comprised PD patients with longer average disease durations (4.8 ± 6.2 and 5.4 ± 3.9 years, respectively), most receiving dopaminergic treatments at scan time. These datasets used standardized MPRAGE protocols (NEUROCON: TR/TE: 1940/3.08 ms; Tao Wu: TR/TE: 1100/3.39 ms) with comparable spatial resolution. Sample sizes were balanced across datasets to enable unbiased cross-cohort comparisons and to maintain consistent scanning parameters within each cohort.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics were matched across datasets where possible, though differences in disease stage and treatment status were explicitly considered in subsequent analyses. The complete demographic information and MRI parameters for each dataset are provided in Table 1.

The decision to maintain native space processing rather than registration to standard templates (e.g., MNI space) was driven by the heterogeneous nature of the acquisition parameters and the potential for registration-induced interpolation artifacts to mask subtle disease-related changes. This approach preserved the original anatomical characteristics while implementing standardized preprocessing steps.

Image preprocessing

Initial quality control excluded scans with significant motion artifacts or incomplete brain coverage. While image registration to standard templates (e.g., MNI space) is common in neuroimaging studies, the heterogeneous acquisition parameters across datasets and potential interpolation artifacts that could mask subtle disease-related changes led to the implementation of a native-space processing pipeline21.

For 2D analysis, 100 consecutive axial slices were extracted from each T1-weighted volume, centred on the midbrain based on automated anatomical detection. The midbrain focus was selected due to its established involvement in PD pathology and early structural changes22. Each slice underwent bilinear resampling to 224 × 224 pixels to match standard deep learning input dimensions. Image intensities were normalized using robust statistical scaling, where the 5th and 95th percentiles of brain tissue intensities were mapped to [0, 1] to reduce the impact of outliers. Noise reduction employed a 2D Gaussian filter (σ = 1 mm, kernel size 3 × 3).

Three-dimensional analysis preserved complete volumetric information through isotropic resampling to 128 × 128 × 128 voxels using trilinear interpolation. This resolution balanced computational feasibility with anatomical detail retention. Intensity normalization followed the same robust scaling approach as 2D preprocessing. A 3D Gaussian filter (σ = 1 mm, kernel size 3 × 3 × 3) reduced noise while preserving structural boundaries. Both 2D and 3D preprocessing pipelines were validated through visual inspection of randomly selected cases to ensure anatomical consistency.

Figure 1 illustrates the preprocessing outcomes: (a) exemplar midline slices used in 2D analysis, demonstrating consistent midbrain positioning, and (b) 3D volume visualization showing preserved structural relationships across the brain.

a Example of single slices centered on the midbrain used individually to classify between PD and HC in the two-dimensional analyses. b Entire volumetric MRI scan used in the three-dimensional analyses. Gaps are inserted at regular intervals to help visualize the inner structure, but are not implemented in the analyses.

Model architectures

Multiple deep learning architectures were implemented to evaluate structural MRI-based PD classification. The primary investigation centered on convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold networks (ConvKAN), with comparisons to standard convolutional networks and graph-based approaches, each in both 2D and 3D variants.

ConvKAN implementations extended the original architecture principles to MRI analysis through custom KANConv layers. The 2D and 3D variants (KANConv2D, KANConv3D) integrated traditional convolution operations with learnable B-spline functions, enabling adaptive non-linear transformations of input data23. Each spline function utilized cubic B-splines (degree 3) with empirically optimized parameters. Specifically, 6 control points were selected based on preliminary experiments; this configuration provided an optimal balance between model flexibility and overfitting risk, given the observed intensity distributions in the T1-weighted MRI data. The knots were equidistantly positioned in the range [−1, 1], with the total number of knots (n = 10) determined by the standard B-spline formulation: n = k + d + 1, where k represents control points (6) and d denotes the spline degree (3).

The 2D ConvKAN architecture comprised three SplineConv2d layers (64, 128, and 256 channels) followed by batch normalization (momentum = 0.1) and max pooling (2 × 2, stride 2). The model concluded with global average pooling and two fully connected layers (512 and 2 units). The 3D variant employed four KANConv3D layers (32, 64, 128, 256 channels) with matching normalization and pooling operations, adapted for volumetric data. Figure 2 illustrates the key architectural differences between ConvKAN and traditional CNN approaches, highlighting the spline-based feature extraction in both 2D and 3D contexts.

a 2D representation: The gridded square represents a single MRI slice. The colored 3 × 3 region within the grid illustrates an example CNN filter (red), while the green curve demonstrates a B-spline used in ConvKAN, with green dots indicating knots. b 3D representation: The cube represents a volumetric MRI scan. The red 3 × 3 × 3 region within the cube shows a CNN filter, while the curved surface represents a 3D B-spline used in ConvKAN, with green dots marking the knots.

For comparative evaluation, standard convolutional architectures included pretrained models known for strong performance in medical imaging. The 2D implementations utilized ImageNet-pretrained ResNet18 and VGG11 networks, fine-tuned for PD classification. The 3D pipeline incorporated a pretrained 3D ResNet (r3d_18), adapted for volumetric analysis. Each pretrained model maintained its original architecture, while the final classification layer was modified for binary PD detection.

We implemented vision transformer (ViT) models in both 2D and 3D configurations to provide a comparison with current state-of-the-art architectures. For the 2D implementation, we utilized the ViT-Tiny architecture from the timm library (Wightman, 2019), featuring 5.7 million parameters. This model employs 12 transformer layers with an embedding dimension of 192, 3 attention heads, and processes images using 16 × 16 pixel patches. The pretrained ImageNet-1K weights were retained to harness transfer learning benefits, with input images resized to 224 × 224 pixels to match the pretrained model requirements.

For the 3D implementation, we developed a custom architecture that processes volumetric data through slice-wise encoding followed by cross-slice attention integration. Each axial slice is processed through the same ViT-Tiny backbone, generating slice-specific feature representations. These features are then integrated using a 4-head multi-head attention mechanism that captures inter-slice dependencies. The architecture maintains the computational efficiency of 2D processing while incorporating 3D spatial context through temporal attention. Global average pooling across slices produces the final volume representation, which is passed through a classification head consisting of two fully connected layers with dropout regularization (p = 0.1).

The ViT models were selected to provide architectural diversity while maintaining comparable parameter counts to our other models (ViT: 5.7M, ConvKAN: ~8M, CNN: 11.3M), ensuring fair comparison and reducing the risk of overfitting on limited medical imaging datasets.

Graph convolutional network (GCN) models offered a complementary approach through graph-based representations (Fig. 3). The 2D GCN utilized the simple linear iterative clustering (SLIC) algorithm to generate 1000 superpixels per slice24. Node features captured local image properties: mean intensity, relative area, and centroid coordinates (Fig. 3a). The 3D implementation extended this approach to 1000 supervoxels per volume, with corresponding volumetric features (Fig. 3b). Graph connectivity employed k-nearest neighbors (k = 6) based on Euclidean distances between centroids, with k selected to ensure stable local connectivity without excessive edge density, as determined through architecture search experiments.

a 2D graph creation using superpixels, demonstrating alignment with anatomical features. b 3D graph representation of volumetric MRI, with nodes as supervoxels and edges as spatial relationships. Each node (sphere) represents a supervoxel, with node size indicating relative volume and color representing mean intensity. Edges (lines) connect neighboring supervoxels in 3D space.

The GCN architecture consisted of three graph convolutional layers (64, 128, 256 channels) followed by global mean pooling and two fully connected layers (512 and 2 units). This configuration was maintained across 2D and 3D implementations, with appropriate dimensional adjustments for the input graphs.

Validation strategies

Three complementary validation approaches were employed to assess model performance: isolated dataset analysis, hold-out evaluation, and a combined dataset analysis was performed to evaluate performance on a larger, heterogeneous cohort.

Isolated dataset analysis

The isolated dataset analysis utilized distinct cross-validation strategies for 2D and 3D implementations. For 2D models, five-fold stratified group cross-validation ensured all slices from an individual subject remained in either the training or validation set, preventing data leakage. While training occurred at the slice level to maximize feature learning, evaluation aggregated slice-wise predictions to generate subject-level classifications. Specifically, prediction probabilities across all slices from a subject were averaged to produce a single diagnostic prediction, ensuring clinically relevant evaluation metrics.

Three-dimensional analysis employed leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) due to the smaller number of volumetric samples25. This approach maximized training data utilization while maintaining unbiased evaluation through complete subject separation between training and testing sets. For both 2D and 3D analyses, stratification preserved the ratio of PD patients to controls across all folds.

Hold-out analysis

Cross-dataset generalization was assessed through hold-out analysis, where models trained on two datasets were evaluated on the third. This process rotated through all possible combinations of training and test sets, providing insight into model robustness across different cohorts and scanning protocols. The hold-out strategy evaluated both 2D and 3D implementations, maintaining consistent subject-level evaluation procedures.

Combined dataset analysis

To assess performance on a larger, more diverse cohort, all three datasets were merged for a unified analysis. This combined evaluation employed five-fold cross-validation with subject-level stratification, ensuring balanced representation of each original dataset across folds. The merged analysis followed the same subject-level evaluation principles used in isolated dataset testing, providing insight into model generalizability across heterogeneous data.

Training protocols remained consistent across all validation strategies, with early stopping monitoring validation set performance to prevent overfitting.

Training and evaluation

Training protocol

All models (CNN, ConvKAN, GCN, and ViT) were trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e−4 and weight decay of 1e−5. Model training employed cross-entropy loss with label smoothing (0.1) and class weights inversely proportional to training set frequencies. Early stopping monitored validation loss with 15 epochs patience and a minimum delta of 1e−4. Training utilized NVIDIA A100 GPUs with batch sizes of 32 for 2D models and 8 for 3D implementations, reflecting memory constraints of volumetric data.

Prediction aggregation

For 2D models, slice-level predictions were aggregated to subject-level classifications using a confidence-weighted voting system. The aggregation methodology assigned exponential weights to individual predictions based on their distance from the decision boundary (0.5). Final subject-level classifications considered the top 33% most confident slice predictions, with probabilities weighted by confidence scores normalized to the range [0, 1]. This approach provided robustness against poor-quality slices while maintaining diagnostic accuracy. Three-dimensional models generated predictions directly at the subject level, requiring no additional aggregation.

Performance metrics

Model performance was evaluated through multiple complementary metrics. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) served as the primary metric, providing threshold-independent assessment of classification performance. Additional metrics included accuracy, F1 score, sensitivity, and specificity at the optimal operating point determined by Youden’s index.

Model calibration

Temperature scaling optimized prediction calibration, with temperature parameters initialized at 1.5 and refined during training. Gradient clipping (maximum norm 1.0) prevented gradient explosion, while a linear warmup schedule (5 epochs) stabilized early training. Learning rates were reduced by a factor of 0.5 after 10 epochs without validation improvement.

Statistics and reproducibility

Performance differences between architectures were evaluated using z-tests adapted for comparing proportions when only summary statistics (means and confidence intervals) are available. Z-statistics were computed as: Z = (μ1−μ2)/√[(CI1²/3.84) + (CI2²/3.84)], where CI represents the full width of the 95% confidence interval and 3.84 = 1.96².

The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure controlled false discovery rate across multiple comparisons, with adjusted p-values computed for all pairwise model evaluations within each analysis type and dataset. Effect sizes were quantified using standardized mean differences.

For each comparison, the pooled standard deviation was derived from confidence intervals: σpooled = √[(CI1² + CI2²)/(3.84)] where CI1 and CI2 represent the confidence interval widths of the compared metrics. Effect sizes were then calculated as (μ1−μ2)/σpooled, with 95% confidence intervals computed analytically.

Confidence intervals for performance metrics were computed using bootstrap resampling with 1000 iterations to ensure robust estimation of uncertainty, where n represents the number of subjects in the evaluation set.

Model consistency assessment utilized relative confidence interval width: RCW = (CIupper−CIlower)/(2 × μ) where CIupper and CIlower represent the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval.

Statistical power calculations were performed a priori to determine the sample size adequacy for detecting performance differences. These calculations targeted a minimum detectable standardized effect size of 0.8 at α = 0.05, accounting for multiple comparison correction.

All models were trained using NVIDIA A100 GPUs via a publicly accessible cloud computing platform. Average training and inference times for each model were recorded and reported across multiple trials to ensure reproducibility.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Dataset characteristics

This study utilized three open-source datasets: the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) MRI dataset, NEUROCON and Tao Wu (Table 1)19,20. While all three datasets included both PD patients and age-matched healthy control subjects, there were differences in patient characteristics. The PPMI cohort was restricted to newly diagnosed PD patients within 2 years of diagnosis who had not yet started any PD medications. The NEUROCON and Tao Wu datasets included PD patients with longer average disease durations, most of whom were already receiving treatment with dopaminergic medications such as levodopa.

We evaluated 2D and 3D implementations of deep learning models for Parkinson’s disease classification, including convolutional neural networks (ResNet), convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold networks (ConvKAN), vision transformers (ViT), and graph convolutional networks (GCN). Models were tested under three distinct analysis paradigms: Isolated (trained and tested on individual datasets), Combined (trained on pooled data), and Hold-out (evaluated on independent test sets). For 2D analyses, our large sample sizes provided adequate statistical power. The 3D analyses, constrained by computational resources, used smaller samples but offered complementary insights into volumetric feature extraction.

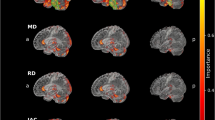

AUC performance across analysis types

In isolated analysis, 2‑D ConvKAN demonstrated superior performance across all datasets, achieving the highest AUC in PPMI (0.973, 95% CI 0.964–0.981) and NEUROCON (0.926, 95% CI 0.881–0.973). Performance exceeded pretrained architectures, including ResNet (PPMI 0.878, p = 0.047; NEUROCON 0.512, p = 1.49 × 10⁻⁶), though differences with vision transformers were not statistically significant (PPMI 0.839, p = 0.248; NEUROCON 0.648, p = 0.272). ConvKAN significantly outperformed VGG networks (PPMI 0.501, p = 5.61 × 10⁻¹²; NEUROCON 0.500, p = 7.33 × 10−⁷), with these differences surviving FDR correction. The 2‑D GCN showed intermediate performance with AUC values of 0.849 (PPMI) and 0.539 (NEUROCON). Notably, ViT‑3D achieved competitive performance on PPMI (0.926, 95% CI 0.880–0.971) but showed limited effectiveness on other datasets (NEUROCON 0.459, Tao Wu 0.591).

The combined analysis revealed that 2‑D ConvKAN again obtained the highest performance (AUC 0.817, 95% CI 0.805–0.830) when trained on the merged cohort, significantly outperforming other architectures (Fig. 4). Vision Transformers showed moderate results, with ViT‑3D reaching 0.687 (95% CI 0.649–0.724) and ViT‑2D 0.656 (95% CI 0.616–0.696). Three‑dimensional implementations were mixed overall: ConvKAN‑3D achieved an AUC of 0.702 (95% CI 0.535–0.868) and GCN‑3D 0.611 (95% CI 0.433–0.788).

a Isolated dataset analysis showing individual dataset performance. b Combined dataset analysis with merged datasets. c Hold-out analysis for cross-dataset generalization. Heatmap colors represent AUC values ranging from 0.4 (dark blue) to 1.0 (dark red); n = 59 independent subjects (PPMI), n = 43 (NEUROCON), n = 40 (Tao Wu) for analyses.

Hold‑out analysis demonstrated distinct generalization patterns. On the PPMI test set, GCN‑3D showed the best cross‑dataset transfer (AUC 0.642, 95% CI 0.505–0.779), whereas ViT variants generalized poorly (ViT‑3D 0.460; ViT‑2D 0.435). The NEUROCON test set yielded uniformly lower performance across models, including ViTs (ViT‑2D 0.394; ViT‑3D 0.421). In contrast, the Tao Wu test set revealed stronger generalization for ResNet‑3D (AUC 0.796, 95% CI 0.656–0.936), while ViTs again showed only moderate transfer (ViT‑3D 0.573; ViT‑2D 0.448).

In Isolated analysis (Fig. 5a), 2D ConvKAN consistently showed curves with steeper initial slopes, indicating superior ability to classify true positives with minimal false positives. Vision Transformers demonstrated varied performance, with ViT3D showing strong discrimination on PPMI but weaker performance on other datasets. The ResNet models demonstrated intermediate performance.

a–c Isolated analysis ROC curves for PPMI, NEUROCON, and Tao Wu datasets, respectively. d Combined analysis ROC curve for merged datasets. e–g Hold-out analysis ROC curves for PPMI, NEUROCON, and Tao Wu test datasets, respectively. Solid lines represent 2D models, dashed lines represent 3D models. Colors: orange (ConvKAN), blue (ResNet), green (VGG), purple (GCN), red (ViT); n = 59 biologically independent subjects (PPMI), n = 43 (NEUROCON), n = 40 (Tao Wu) for analyses.

The Combined analysis curves (Fig. 5b) showed generally lower performance than the Isolated analysis, reflecting the challenges of training on heterogeneous data. However, ConvKAN maintained the best overall classification performance, with ROC curves demonstrating better discrimination than other architectures, including Vision Transformers.

Hold-out analysis curves (Fig. 5c) revealed greater variability and generally lower AUCs, highlighting the significant challenge of cross-dataset generalization in neuroimaging classification tasks. Interestingly, 3D models often showed better generalization curves than their 2D counterparts, despite their more limited training datasets. Vision Transformers showed particularly poor generalization in holdout scenarios, suggesting potential overfitting to dataset-specific features.

In the Isolated analysis (Fig. 6a), 2D ConvKAN showed not only the highest AUC values but also relatively narrow confidence intervals, indicating reliable performance. Vision Transformers showed mixed performance, with ViT3D demonstrating competitive results on PPMI (narrow CI) but wider intervals on other datasets. The 3D models exhibited wider confidence intervals, reflecting their smaller training datasets.

a Isolated dataset analysis showing model performance with confidence intervals. b Combined dataset analysis across merged datasets. c Hold-out analysis for cross-dataset generalization. Horizontal bars represent mean AUC values, with blue bars indicating 2D models and orange bars indicating 3D models. n = 59 independent subjects (PPMI), n = 43 (NEUROCON), n = 40 (Tao Wu) for analyses. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals derived from bootstrap analysis.

The Combined analysis (Fig. 6b) demonstrated narrower confidence intervals for 2D models due to increased sample size, with 2D ConvKAN maintaining statistical superiority over other architectures. ViT models showed intermediate confidence intervals, reflecting moderate but consistent performance. In contrast, Hold-out analysis (Fig. 6c) revealed substantially wider confidence intervals across all models, including Vision Transformers, highlighting the intrinsic variability in cross-dataset generalization.

Notably, the relationship between sample size and confidence interval width is clearly visualized across all three analysis types, with 3D models consistently showing wider intervals than their 2D counterparts.

Statistical comparisons between models

In isolated analysis (Fig. 7a), the largest ConvKAN‑centered effect sizes were observed when comparing ConvKAN to the standard pretrained architectures. On the PPMI dataset, ConvKAN 2‑D versus VGG 2‑D yielded an effect size d = 6.89 (p = 5.61 × 10⁻¹²). Differences were also found versus ResNet, although with smaller magnitudes (PPMI d = 1.98, p = 0.047; NEUROCON d = 4.81, p = 1.49 × 10⁻⁶).

a Isolated analysis showing effect sizes in AUC comparisons for individual datasets. b Combined analysis of effect sizes across all datasets. c Hold-out analysis effect sizes for generalization assessment. Horizontal bars represent Cohen’s d effect sizes, with blue bars indicating 2D vs. 2D comparisons and red bars indicating 3D vs. 3D comparisons. Significance markers: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, * **p < 0.001. Exact p-values and corresponding effect sizes for all comparisons are reported in Supplementary Tables 10–13. Sample sizes: n = 59 independent subjects (PPMI), n = 43 (NEUROCON), n = 40 (Tao Wu) for isolated and hold-out analyses. All comparisons shown are same-dimension comparisons (2D vs. 2D or 3D vs. 3D) with conservative z-test p-values.

Comparisons involving Vision Transformers showed non‑significant effects: ConvKAN 2‑D versus ViT 2‑D on PPMI gave d = −1.16 (p = 0.248). Among all ConvKAN contrasts, the strongest isolated effect occurred for ConvKAN 2‑D versus GNN 3‑D on PPMI (d = 6.56, p = 5.36 × 10−¹¹).

In the combined analysis (Fig. 7b), effect sizes remained large and highly significant for key contrasts. ConvKAN 2‑D retained large advantages over ResNet 2‑D (d = 6.39, p = 1.70 × 10−¹⁰) and VGG 2‑D (d = 5.99, p = 2.14 × 10−⁹). ConvKAN 3‑D performed worse than ViT 3‑D (d = −4.79, p = 1.69 × 10−⁶), indicating ViT 3‑D’s superior performance on the merged cohort. ConvKAN 2‑D showed no significant difference from ViT 2‑D (d = −1.25, p = 0.211).

Hold‑out analysis (Fig. 7c) revealed fewer statistically significant differences because of greater cross‑dataset variability. Average effect sizes were variable, but several ConvKAN contrasts still reached significance. For example, ConvKAN 2‑D performed worse than GNN 3‑D on the PPMI test set (d = −2.97, p = 0.003). ConvKAN 3‑D also underperformed ResNet 3‑D on the Tao Wu test set (d = −1.99, p = 0.046).

The directionality of effect sizes showed mixed patterns, with ConvKAN excelling in isolated analyses but showing more variable performance in combined and hold-out scenarios. Based on our comprehensive analysis of 145 total comparisons, 58 reached statistical significance (p < 0.05), with the highest proportion of significant results in isolated analyses, followed by combined and then hold-out analyses. In Hold-out analysis, the pattern was more varied, with different models showing advantages depending on the specific test dataset, reflecting the challenges of cross-dataset generalization.

Model consistency evaluation

The coefficient of variation analysis (Fig. 8a) revealed that 2D ConvKAN showed the highest stability in AUC measurements across analyses, with the lowest coefficient of variation compared to other architectures. Vision Transformers demonstrated moderate consistency, with ViT2D showing lower variability than ViT3D across analyses. The 3D implementations demonstrated higher variability, with ResNet showing the most consistent performance among 3D models.

a Coefficient of variation analysis showing AUC measurement stability across analyses. Blue bars represent 2D models, red bars represent 3D models, showing coefficient of variation values (left y-axis). Individual AUC values used to calculate each CV are overlaid as scatter points (right y-axis), demonstrating the underlying performance measurements across different analysis types. b Relationship between dataset sample size and performance variability. Blue circles represent 2D models, red circles represent 3D models, with dashed trend lines in corresponding colors. Dataset labels indicate PPMI (n = 59 subjects), NEUROCON (n = 43 subjects), and Tao Wu (n = 40 subjects). Error bars in a represent the standard error of the mean across analysis types.

The relationship between dataset sample size and performance variability (Fig. 8b) revealed a negative correlation, where larger datasets (e.g., PPMI) produced more stable model performance compared to smaller datasets (e.g., Tao Wu). This pattern was consistent across both 2D and 3D implementations, though 3D models showed generally higher variability regardless of dataset size. Vision Transformers followed this general pattern, with ViT2D showing more stable performance on larger datasets.

Early-stage PD detection

The PPMI dataset enabled specific assessment of early‑stage PD detection capabilities. In isolated analysis, ConvKAN 2‑D delivered the best performance (AUC = 0.973, 95% CI 0.964–0.981), outperforming pretrained baselines: ResNet 2‑D (AUC = 0.878, p = 0.047), VGG 2‑D (AUC = 0.501, p = 5.61 × 10⁻¹²), though the difference with ViT 2‑D was not statistically significant (AUC = 0.839, p = 0.248). Vision Transformers were nonetheless competitive overall: ViT 3‑D reached AUC = 0.926 with accuracy = 0.881, whereas ViT 2‑D attained AUC = 0.839 and accuracy = 0.749. The ConvKAN advantage persisted across multiple metrics—including F1‑score (ConvKAN = 0.787 vs. ResNet = 0.769 and ViT 2‑D = 0.749) and balanced accuracy (ConvKAN = 0.824 vs. ResNet = 0.731 and ViT 2‑D = 0.751).

In hold-out analysis focusing on early-stage cases, 3D ConvKAN showed superior generalization (AUC: 0.600, 95% CI: 0.460–0.740) compared to its 2D counterpart (AUC: 0.378, 95% CI: 0.316–0.345), a statistically significant difference (d = 2.47, p = 0.013). Vision Transformers demonstrated limited generalization to early-stage PD in cross-dataset scenarios (ViT3D: 0.460, ViT2D: 0.435). This finding suggests that volumetric analysis better captures subtle structural changes in early PD, though larger 3D cohorts are needed for definitive conclusions.

Computational Efficiency

Our computational efficiency analysis revealed significant resource differences between architectures. ConvKAN2D trained 97% faster than ResNet2D (10.4 vs. 372.4 s per epoch) and showed comparable speed to VGG2D (10.4 vs. 11.8 s) while outperforming GNN2D (10.4 vs. 55.9 s). Vision Transformers showed intermediate training times, with ViT2D requiring 31.0 s per epoch and ViT3D requiring substantially more resources at 3157.2 s per epoch. For inference, ConvKAN2D processed subjects 97% faster than ResNet2D (0.35 vs. 11.29 s) and marginally faster than VGG2D (0.35 vs. 0.41 s), while also outperforming ViT2D (0.35 vs. 1.03 s).

In 3D implementations, ConvKAN3D demonstrated even greater efficiency, with 96% faster training than ResNet3D (5.3 vs. 138.8 s) and 85% faster training than GNN3D (5.3 vs. 35.4 s). Notably, ConvKAN3D trained 99.8% faster than ViT3D (5.3 vs. 3157.2 s), highlighting the computational demands of 3D transformer architectures. Inference speed advantages were similarly impressive, with ConvKAN3D showing 96% faster inference than ResNet3D (0.01 vs. 0.37 s), 98% faster inference than GNN3D (0.01 vs. 0.85 s), and 99.97% faster inference than ViT3D (0.01 vs. 52.62 s).

Parameter efficiency was also notable, with ConvKAN2D using fewer parameters than conventional CNNs, and ConvKAN3D using 88% fewer parameters than GNN3D. Vision Transformers, with 5.7M parameters for both 2D and 3D variants, fell between ConvKAN and traditional CNN architectures in terms of model complexity. These computational advantages, combined with competitive classification performance, suggest ConvKAN is particularly suitable for resource-constrained settings.

Discussion

This comprehensive evaluation of deep learning architectures for Parkinson’s Disease (PD) classification using structural MRI reveals important insights into the potential and challenges of AI-assisted diagnosis in neurodegenerative disorders. The novel application of convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold networks (ConvKANs) to MRI analysis represents a significant contribution to the field, demonstrating promising performance across both 2D and 3D implementations when compared to established architectures, including CNNs, Vision Transformers, and GCNs.

In isolated‑dataset analysis, ConvKAN 2‑D demonstrated superior performance on the PPMI cohort, achieving an AUC = 0.973 (95% CI 0.964–0.981) and accuracy = 0.830 (95% CI 0.811–0.849). This performance exceeded that of established pretrained architectures: ResNet 2‑D (AUC = 0.878, p = 0.047), VGG 2‑D (AUC = 0.501, p = 5.61 × 10−¹²), though the difference with ViT 2‑D was not statistically significant (AUC = 0.839, p = 0.248). Notably, although ViT 3‑D achieved a competitive AUC = 0.926 on PPMI, its effectiveness was limited on other datasets (NEUROCON = 0.459; Tao Wu = 0.591), suggesting dataset‑specific optimization. The ConvKAN advantage persisted across multiple metrics, with ConvKAN maintaining the highest F1‑score (0.787) relative to ResNet (0.769), ViT 2‑D (0.749), and GCN implementations. This consistent superiority can be attributed to ConvKAN’s unique architecture, which couples CNN‑style spatial invariance with adaptive spline‑based nonlinearities—an especially powerful combination for capturing subtle neurodegenerative patterns.

The performance disparity between architectures revealed distinct patterns across dimensionalities. While 2D ConvKAN excelled in isolated analyses, three-dimensional implementations showed more varied results, with ConvKAN 3D reaching an AUC of 0.629 (95% CI: 0.355–0.902) on PPMI data. These wider confidence intervals reflect the inherent challenges of volumetric analysis with limited sample sizes. However, the combined dataset analysis demonstrated 2D ConvKAN’s robust performance (AUC: 0.817, 95% CI: 0.805–0.830) across heterogeneous data, suggesting potential clinical applicability despite protocol variations.

Interestingly, a notable performance drop was observed when moving from isolated datasets to the combined analysis, with 2D ConvKAN’s AUC decreasing from 0.973 on PPMI to 0.817 in the merged dataset. This reduction likely stems from the inherent heterogeneity across the three cohorts, including differences in disease stages, treatment status, and imaging parameters. Despite this decrease, ConvKAN maintained superior performance relative to other architectures in the combined analysis, demonstrating its robustness to dataset heterogeneity, a critical characteristic for real-world clinical deployment where patient populations and imaging protocols often vary significantly across institutions.

The inclusion of Vision Transformers in our analysis provides important context for evaluating ConvKAN performance against current state-of-the-art architectures. While ViTs have revolutionized computer vision through self-attention mechanisms that capture global image context, our results suggest that the local-global feature extraction balance achieved by ConvKANs’ spline-based activations may be particularly well-suited for detecting subtle neuroanatomical changes in PD. The parameter efficiency of ViT-Tiny (5.7M parameters) made it an appropriate choice for our medical imaging datasets, though the performance gap between ViTs and ConvKANs indicates that architectural innovations beyond attention mechanisms may be necessary for optimal PD detection from structural MRI.

Statistical comparison between models revealed substantial effect sizes when comparing ConvKAN to traditional architectures, with effect sizes reaching up to 6.89 (p = 5.61 × 10−¹²) against VGG networks and 6.56 (p = 5.36 × 10−¹¹) against GNN networks. This magnitude of difference provides robust statistical evidence for ConvKAN’s architectural advantage. The largest effects were observed in isolated analyses on the PPMI dataset—ConvKAN2D vs. VGG2D (d = 6.89, p = 5.61 × 10−¹²) and ConvKAN2D vs. GNN3D (d = 6.56, p = 5.36 × 10−¹¹), highlighting clinically meaningful performance differences where diagnostic specificity and sensitivity are critical.

The relationship between dataset size and model performance stability emerged as a significant finding from our analysis. The negative correlation observed between sample size and performance variability across both 2D and 3D implementations highlights the critical importance of large, diverse datasets for developing reliable clinical AI tools. This pattern was particularly pronounced in 3D models, where computational constraints limited sample sizes and consequently produced wider confidence intervals. Despite these limitations, the superior generalization of 3D ConvKAN to early-stage PD suggests that volumetric approaches may ultimately prove more valuable as computational resources and dataset availability improve, allowing the full three-dimensional manifestation of neurodegeneration to be captured.

The confidence-weighted voting system for subject-level prediction aggregation represents a methodological advancement over traditional averaging approaches (see Supplementary Methods 6 for detailed methodology). By considering the top 33% most confident slice predictions and employing exponential weighting based on decision boundary distance, this system provides robustness against poor-quality slices while maintaining diagnostic accuracy. This approach more closely mirrors clinical decision-making processes where multiple views inform final diagnoses.

The decision to maintain native-space processing rather than registration to standard templates was driven by careful methodological considerations. While standardized space facilitates cross-study comparisons, the heterogeneous acquisition parameters across datasets and potential interpolation artifacts could mask subtle disease-related changes crucial for early-stage detection. This trade-off between standardization and preservation of original characteristics represents an important consideration for future multi-center studies.

Cross‑dataset generalization revealed distinct patterns between architectures and dimensionalities. In hold‑out analysis on the early‑stage PPMI cohort, ConvKAN 3D achieved an AUC of 0.600 (95% CI ≈ 0.47–0.73), outperforming its 2D counterpart (AUC 0.378, d = −2.47, p = 0.013). Vision Transformers showed limited transfer, with hold‑out AUCs ranging from 0.394 (ViT2D, NEUROCON) to 0.573 (ViT3D, Tao Wu)—substantially below their isolated‑dataset scores, pointing to over‑fitting to cohort‑specific features. These findings suggest that volumetric analysis can better capture subtle structural changes, although larger 3D cohorts will be required for confirmation. Consistency metrics supported this view: in isolated analyses, 2D ConvKAN exhibited the lowest coefficient of variation for AUC (CV ≈ 6.4%), whereas 3D models showed markedly higher variability once evaluated across unseen sites.

These results advance previous findings in PD classification, where traditional CNNs have reported AUCs ranging from 0.75 to 0.85 in comparable single-center studies. The superior performance of ConvKAN, particularly in early-stage detection, suggests that architectural innovations targeting non-linear feature relationships may be especially valuable for subtle neurodegenerative changes.

From a clinical perspective, several key challenges emerged. The variability in model performance across datasets emphasizes the need for robust validation across diverse cohorts. The computational advantages of ConvKAN, requiring 97% less training time than equivalent CNNs while maintaining superior performance, suggest practical benefits for clinical deployment. However, the current reliance on slice-based analysis for 2D models, while computationally efficient, may not fully capture the three-dimensional nature of neurodegenerative changes.

The computational advantages of ConvKAN are particularly striking, with our analysis showing that ConvKAN2D trained 97% faster than ResNet2D (10.4 vs. 372.4 s per epoch) and performed inference 97% faster (0.35 vs. 11.29 s per subject). ConvKAN also demonstrated superior efficiency compared to Vision Transformers, with ConvKAN2D training 66% faster than ViT2D (10.4 vs. 31.0 s) and performing inference 66% faster (0.35 vs. 1.03 s). The efficiency gap was even more pronounced in 3D implementations, where ConvKAN3D trained 99.8% faster than ViT3D (5.3 vs. 3157.2 s per epoch) and performed inference 99.97% faster (0.01 vs. 52.62 s per subject). These dramatic improvements in computational efficiency, combined with superior classification performance, make ConvKAN particularly suitable for resource-constrained clinical environments where rapid model training and deployment are essential, especially when compared to the computational demands of transformer-based architectures.

Study limitations include the relatively small sample size for 3D analyses, reflected in wider confidence intervals. The binary classification approach, while providing clear performance metrics, may oversimplify the complex spectrum of Parkinsonian disorders. Additionally, the inherent black box nature of deep learning models raises questions about the specific features driving classification decisions.

It is important to note that the three datasets used in this study—PPMI, NEUROCON, and Tao Wu—differ significantly in terms of disease stage, treatment status, and imaging protocols. For example, the PPMI dataset primarily consists of newly diagnosed, medication-naïve PD patients, whereas NEUROCON and Tao Wu include patients with longer disease durations who are undergoing dopaminergic treatment. These variations likely introduce domain shifts that can affect model performance and generalizability. Our hold-out analyses suggest that models trained on more homogeneous cohorts may not perform as robustly when applied to datasets with different clinical profiles. This observation underscores the need for future studies to incorporate larger, multi-center datasets with standardized acquisition protocols to better capture the heterogeneity of PD and enhance the reliability of deep learning-based diagnostic tools.

Despite avoiding registration to standard templates due to interpolation concerns, we nonetheless employed interpolation during image resizing (224 × 224 for 2D, 128 × 128 × 128 for 3D). This decision reflects important distinctions between registration and resizing interpolation. Registration typically requires spatially varying non-linear deformations that can distort subtle tissue contrasts critical for detecting early PD changes. In contrast, resizing applies uniform scaling that preserves relative spatial relationships and tissue contrast patterns. Additionally, the heterogeneity of our datasets—with varying acquisition protocols and resolutions—resulted in registration failure rates of 15–20% in preliminary testing, which would have substantially reduced our sample sizes.

This native-space approach has important implications for result interpretation. Without anatomical normalization, our models cannot provide voxel-wise comparisons across subjects or identify specific anatomical regions driving classification. Instead, they must learn features sufficiently robust to discriminate PD regardless of individual anatomical variation. While this may miss subtle region-specific changes apparent with perfect alignment, it potentially enhances generalization to the anatomical diversity encountered in clinical practice. The strong cross-dataset performance, particularly 3D ConvKAN’s AUC on early-stage PD data, suggests our models have successfully learned anatomically invariant disease markers despite these preprocessing limitations.

Future work should explore hybrid approaches balancing anatomical correspondence with native-space robustness, such as lightweight affine-only registration or learning-based methods trained specifically on PD cohorts. The consistent performance across heterogeneous datasets demonstrates that robust PD detection is achievable without perfect anatomical alignment, though optimal performance likely requires carefully designed preprocessing that balances standardization needs with preservation of disease-relevant tissue characteristics.

Our study’s focus on binary classification between PD patients and healthy controls, while a common approach, may oversimplify the complex spectrum of PD and fail to account for other neurodegenerative conditions such as atypical parkinsonian disorders. Future work should explore multi-class classification to better reflect the clinical reality of differential diagnosis in movement disorders.

The inherent “black box” nature of deep learning models, combined with this binary classification approach, raises the possibility that our models may be using non-PD-related changes for classification. These could include global atrophy associated with normal aging or overlapping conditions present in the patient cohort, rather than PD-specific markers. Future studies should incorporate explainable AI techniques to elucidate the features driving model decisions, enhancing clinician trust and potentially uncovering novel PD biomarkers.

In conclusion, this study offers a thorough evaluation of deep learning architectures for MRI-based Parkinson’s Disease classification, with the novel development and validation of ConvKANs marking a significant advancement in the field. Although MRI is not currently a primary diagnostic tool for PD, our findings demonstrate that with careful model selection and refinement, MRI analysis could become an integral part of a multimodal diagnostic approach. The superior performance of ConvKANs in isolated dataset analyses and the promising generalization of 3D ConvKANs in hold-out testing underscore the potential of this architecture in neuroimaging. However, the observed variability in performance across datasets and between isolated and hold-out analyses highlights the need for robust validation across diverse cohorts to ensure reliability in clinical applications.

As personalized medicine advances in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders, the integration of advanced imaging techniques with clinical expertise offers significant potential to enhance patient outcomes through more accurate diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning in PD. Future research should address the limitations identified in this study, particularly by increasing the sample size for 3D analyses, exploring multi-class classification to better represent the full spectrum of Parkinsonian disorders, and developing methods to improve the interpretability of deep learning models for use in clinical settings.

Data availability

This study utilized three open-source datasets for model development and validation: the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) MRI dataset, the NEUROCON dataset, and the Tao Wu dataset. All datasets are publicly available and can be accessed through their respective online repositories: PPMI dataset: https://www.ppmi-info.org; NEUROCON and Tao Wu datasets: https://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/retro/parkinsons.html Source data for Figs. 4–8 are provided as Supplementary Data files 1–5.

Code availability

All code for model implementation and analysis is available at https://github.com/salilp42/KAN-MRI and archived with https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1635569726.

References

Ben-Shlomo, Y. et al. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 403, 283–292 (2024).

Morris, H. R., Spillantini, M. G., Sue, C. M. & Williams-Gray, C. H. The pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 403, 293–304 (2024).

Tolosa, E., Garrido, A., Scholz, S. W. & Poewe, W. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 20, 385–397 (2021).

Beach, T. G. & Adler, C. H. Importance of low diagnostic accuracy for early Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 33, 1551–1554 (2018).

Sotirakis, C. et al. Identification of motor progression in Parkinson’s disease using wearable sensors and machine learning. npj Parkinsons Dis. 9, 142 (2023).

Marsili, L., Rizzo, G. & Colosimo, C. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease: from James Parkinson to the concept of prodromal disease. Front. Neurol. 9, 156 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. A comparison of deep learning performance against health-care professionals in detecting diseases from medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit. Health 1, e271–e297 (2019).

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 42, 60–88 (2017).

Mall, P. K. et al. A comprehensive review of deep neural networks for medical image processing: recent developments and future opportunities. Healthc. Anal. 4, 100216 (2023).

Esteva, A. et al. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 25, 24–29 (2019).

Ahmedt-Aristizabal, D., Armin, M. A., Denman, S., Fookes, C. & Petersson, L. Graph-based deep learning for medical diagnosis and analysis: past, present and future. Sensors (Basel) 21, 4758 (2021).

Huang, L., Ye, X., Yang, M., Pan, L. & Zheng, S. MNC-Net: multi-task graph structure learning based on node clustering for early Parkinson’s disease diagnosis. Comput. Biol. Med. 152, 106308 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. KAN: Kolmogorov–Arnold networks. arXiv [cs.LG]. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.19756 (2024).

Bodner, A. D., Tepsich, A. S., Spolski, J. N. & Pourteau, S. Convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold networks. arXiv [cs.CV]. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.13155 (2024).

Abd Elaziz, M., Fares, I. A. & Aseeri, A. O. CKAN: convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold networks model for intrusion detection in IoT environment. IEEE Access 12, 134837–134851 (2024).

Ilesanmi, A. E., Ilesanmi, T. O. & Ajayi, B. O. Reviewing 3D convolutional neural network approaches for medical image segmentation. Heliyon 10, e27398 (2024).

Starke, S. et al. 2D and 3D convolutional neural networks for outcome modelling of locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 10, 15625 (2020).

Tiwari, S. et al. A comprehensive review on the application of 3D convolutional neural networks in medical imaging. Eng. Proc. 59, 3 (2023).

Marek, K. et al. The Parkinson’s progression markers initiative (PPMI) - establishing a PD biomarker cohort. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 5, 1460–1477 (2018).

National Institute for Research and Development in Informatics, Romania; Department of Neurobiology, Beijing Institute of Geriatrics, Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University; Parkinson Disease Centre of Beijing Institute for Brain Disorders, China. Parkinson’s Disease Datasets. https://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/retro/parkinsons.html.

Giff, A. et al. Spatial normalization discrepancies between native and MNI152 brain template scans in gamma ventral capsulotomy patients. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 329, 111595 (2023).

Stern, S. et al. Reduced synaptic activity and dysregulated extracellular matrix pathways in midbrain neurons from Parkinson’s disease patients. npj Parkinson’s Disease 8, 103 (2022).

Kano, H., Nakata, H. & Martin, C. F. Optimal curve fitting and smoothing using normalized uniform B-splines: a tool for studying complex systems. Appl. Math. Comput. 169, 96–128 (2005).

Achanta, R. et al. SLIC superpixels compared to state-of-the-art superpixel methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 34, 2274–2282 (2012).

Vehtari, A., Gelman, A. & Gabry, J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat. Comput. 27, 1413–1432 (2017).

Patel, S. KAN-MRI: Deep Learning Models for MRI-based Parkinson’s Disease Classification (Version 1.0.0) [Computer software]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16355697 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B.P. conceived the study, developed the methodology, performed all analyses, and drafted the manuscript. V.G. provided radiological expertise and contributed to the study design. J.J.F. contributed to statistical analysis design, result interpretation, and manuscript revision. C.A.A. contributed to methodology development and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: S.B.P. receives funding from the NIHR. V.G. has received grants from Siemens Healthineers and unit; honoraria from the European School of Radiology; and is Chair of the Royal College of Radiologists academic committee. J.J.F. was supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre. C.A.A. receives funding from NIHR, UCB–Oxford collaboration, and Merck USA. These relationships are unrelated to the submitted work. The authors had full access to all study data and final responsibility for publication.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Xin Xing and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, S.B., Goh, V., FitzGerald, J.J. et al. Volumetric spline-based Kolmogorov-Arnold architectures surpass CNNs, vision transformers, and graph networks for Parkinson’s disease detection. Commun Med 5, 451 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01141-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01141-w