Abstract

Macrocyclization is crucial in natural product biosynthesis for enhancing molecular rigidity and stability. Although thioesterase-mediated macrolactonization or macrolactamization is the predominant mechanism in type I polyketide synthases, here we report an alternative macrocyclization mechanism in which nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2)-like enzymes catalyse a tandem stereoselective Michael addition and Knoevenagel condensation to construct a tetrahydrofuran-fused macrocyclic carbocycle. Genome mining identified a family of NTF2-like proteins that share this tandem cyclization capability. X-ray crystal structures complexed with substrate mimics and structure-based mutagenesis reveal that a lysine residue forms an iminium intermediate with the terminal aldehyde to enable cyclization, while an aspartic acid acts as a general base to mediate proton transfers. Structures capturing distinct states, from linear precursor to precyclization, provide direct insight into the ring-closure process. This work elucidates an iminium-catalysed tandem cyclization mechanism, expanding the known catalytic repertoire of NTF2-like enzymes and highlighting the potential of iminium-based biocatalysis in natural product biosynthesis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Crystal structures of AkaM, SacM, CatM, MicM, SacM–3, SacM–6b, CatM–6b and CatM–W86A–6a have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 9IQ3, 9IQ7, 9IQ5, 9IQD, 9IQK, 9IQL, 9IQM and 9IQN, respectively.

References

Kopp, F. & Marahiel, M. A. Macrocyclization strategies in polyketide and nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 735–715 (2007).

Lu, J., Li, Y., Bai, Z., Lv, H. & Wang, H. Enzymatic macrocyclization of ribosomally synthesized and posttranslational modified peptides via C–S and C–C bond formation. Nat. Prod. Rep. 38, 981–992 (2021).

Vinogradov, A. A., Yin, Y. & Suga, H. Macrocyclic peptides as drug candidates: recent progress and remaining challenges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 4167–4181 (2019).

Itoh, H. & Inoue, M. Comprehensive structure–activity relationship studies of macrocyclic natural products enabled by their total syntheses. Chem. Rev. 119, 10002–10031 (2019).

Martí-Centelles, V., Pandey, M. D., Burguete, M. I. & Luis, S. V. Macrocyclization reactions: the importance of conformational, configurational, and template-induced preorganization. Chem. Rev. 115, 8736–8834 (2015).

Horsman, M. E., Hari, T. P. A. & Boddy, C. N. Polyketide synthase and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase thioesterase selectivity: logic gate or a victim of fate?. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 183–202 (2016).

Czekster, C. M., Ludewig, H., McMahon, S. A. & Naismith, J. H. Characterization of a dual function macrocyclase enables design and use of efficient macrocyclization substrates. Nat. Commun. 8, 1045 (2017).

Chekan, J. R., Estrada, P., Covello, P. S. & Nair, S. K. Characterization of the macrocyclase involved in the biosynthesis of RiPP cyclic peptides in plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6551–6556 (2017).

Lee, J., McIntosh, J., Hathaway, B. J. & Schmidt, E. W. Using marine natural products to discover a protease that catalyzes peptide macrocyclization of diverse substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 2122–2124 (2009).

Li, K., Condurso, H. L., Li, G., Ding, Y. & Bruner, S. D. Structural basis for precursor protein-directed ribosomal peptide macrocyclization. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 973–979 (2016).

Hegemann, J. D., Zimmermann, M., Xie, X. & Marahiel, M. A. Lasso peptides: an intriguing class of bacterial natural products. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1909–1919 (2015).

Haslinger, K., Peschke, M., Brieke, C., Maximowitsch, E. & Cryle, M. J. X-domain of peptide synthetases recruits oxygenases crucial for glycopeptide biosynthesis. Nature 521, 105–109 (2015).

Holding, A. N. & Spencer, J. B. Investigation into the mechanism of phenolic couplings during the biosynthesis of glycopeptide antibiotics. ChemBioChem 9, 2209–2214 (2008).

Aldemir, H. et al. Carrier protein-free enzymatic biaryl coupling in arylomycin A2 assembly and structure of the cytochrome P450 AryC. Chemistry 28, e202104451 (2022).

Nanudorn, P. et al. Atropopeptides are a novel family of ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides with a complex molecular shape. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208361 (2022).

He, B.-B. et al. Bacterial cytochrome P450 catalyzed posttranslational macrocyclization of ribosomal peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311533 (2023).

Nam, H. et al. Exploring the diverse landscape of biaryl-containing peptides generated by cytochrome P450 macrocyclases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 22047–22057 (2023).

Hu, Y. et al. P450-modified ribosomally synthesized peptides with aromatic cross-Links. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27325–27335 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. P450-modified multicyclic cyclophane-containing ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202314046 (2024).

Belin, P. et al. Identification and structural basis of the reaction catalyzed by CYP121, an essential cytochrome P450 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 7426–7431 (2009).

Schramma, K. R., Bushin, L. B. & Seyedsayamdost, M. R. Structure and biosynthesis of a macrocyclic peptide containing an unprecedented lysine-to-tryptophan crosslink. Nat. Chem. 7, 431–437 (2015).

Clark, K. A. & Seyedsayamdost, M. R. Bioinformatic atlas of radical SAM enzyme-modified RiPP natural products reveals an isoleucine–tryptophan crosslink. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17876–17888 (2022).

Nguyen, H. et al. Characterization of a radical SAM oxygenase for the ether crosslinking in darobactin biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 18876–18886 (2022).

Nguyen, T. Q. N. et al. Post-translational formation of strained cyclophanes in bacteria. Nat. Chem. 12, 1042–1053 (2020).

Sydor, P. K. et al. Regio- and stereodivergent antibiotic oxidative carbocyclizations catalysed by Rieske oxygenase-like enzymes. Nat. Chem. 3, 388–392 (2011).

Ohashi, M. et al. Biosynthesis of para-cyclophane-containing hirsutellone family of fungal natural products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 5605–5609 (2021).

Dorival, J. et al. Insights into a dual function amide oxidase/macrocyclase from lankacidin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 9, 3998 (2018).

Zhang, G. et al. Mechanistic insights into polycycle formation by reductive cyclization in ikarugamycin biosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 4840–4844 (2014).

Ding, W. et al. Biosynthetic investigation of phomopsins reveals a widespread pathway for ribosomal natural products in Ascomycetes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3521–3526 (2016).

Ye, Y. et al. Unveiling the biosynthetic pathway of the ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide ustiloxin B in filamentous fungi. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8072–8075 (2016).

Hudson, G. A., Zhang, Z., Tietz, J. I., Mitchell, D. A. & van der Donk, W. A. In vitro biosynthesis of the core scaffold of the thiopeptide thiomuracin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 16012–16015 (2015).

Tian, Z. et al. An enzymatic [4 + 2] cyclization cascade creates the pentacyclic core of pyrroindomycins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 259–265 (2015).

Hashimoto, T. et al. Biosynthesis of versipelostatin: identification of an enzyme-catalyzed [4 + 2]-cycloaddition required for macrocyclization of spirotetronate-containing polyketides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 572–575 (2015).

Li, B. et al. Structure and mechanism of the lantibiotic cyclase involved in nisin biosynthesis. Science 311, 1464–1467 (2006).

Zhu, H. et al. AvmM catalyses macrocyclization through dehydration/Michael-type addition in alchivemycin A biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 13, 4499 (2022).

Mydy, L. S. et al. An intramolecular macrocyclase in plant ribosomal peptide biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 530–540 (2024).

Igarashi, Y. et al. Akaeolide, a carbocyclic polyketide from marine-derived Streptomyces. Org. Lett. 15, 5678–5681 (2013).

Nakashima, T. et al. Mangromicins A and B: structure and antitrypanosomal activity of two new cyclopentadecane compounds from Lechevalieria aerocolonigenes K10-0216. J. Antibiot. 67, 253–260 (2014).

Zhou, T. et al. Biosynthesis of akaeolide and lorneic acids and annotation of type I polyketide synthase gene clusters in the genome of Streptomyces sp. NPS554. Mar. Drugs 13, 581–596 (2015).

Goranovic, D. et al. Origin of the allyl group in FK506 biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14292–14300 (2010).

Zhang, H.-B. et al. Construction of BIBAC and BAC libraries from a variety of organisms for advanced genomics research. Nat. Protoc. 7, 479–499 (2012).

Li, S., Du, L. & Bernhardt, R. Redox partners: function modulators of bacterial P450 enzymes. Trends Microbiol. 28, 445–454 (2020).

Zou, Y. Z. et al. Crystal structures of phosphite dehydrogenase provide insights into nicotinamide cofactor regeneration. Biochemistry 51, 4263–4270 (2012).

Bullock, T. L., Clarkson, W. D., Kent, H. M. & Stewart, M. The 1.6 angstroms resolution crystal structure of nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2). J. Mol. Biol. 260, 422–431 (1996).

Eberhardt, R. Y. et al. Filling out the structural map of the NTF2-like superfamily. BMC Bioinf. 14, 327 (2013).

Kim, S. W. et al. High-resolution crystal structures of Δ5-3-ketosteroid isomerase with and without a reaction intermediate analogue. Biochemistry 36, 14030–14036 (1997).

Nakasako, M., Motoyama, T., Kurahashi, Y. & Yamaguchi, I. Cryogenic X-ray crystal structure analysis for the complex of scytalone dehydratase of a rice blast fungus and its tight-binding inhibitor, carpropamid: the structural basis of tight-binding inhibition. Biochemistry 37, 9931–9939 (1998).

Arand, M. et al. Structure of Rhodococcus erythropolis limonene-1,2-epoxide hydrolase reveals a novel active site. EMBO J. 22, 2583–2592 (2003).

Sultana, A. et al. Structure of the polyketide cyclase SnoaL reveals a novel mechanism for enzymatic aldol condensation. EMBO J. 23, 1911–1921 (2004).

Zhang, B. et al. Enzyme-catalysed [6 + 4] cycloadditions in the biosynthesis of natural products. Nature 568, 122–126 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Biosynthesis of sordarin revealing a Diels–Alderase for the formation of the norbornene skeleton. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205577 (2022).

Drulyte, I. et al. Crystal structure of the putative cyclase IdmH from the indanomycin nonribosomal peptide synthase/polyketide synthase. IUCrJ 6, 1120–1133 (2019).

Niwa, K. et al. Biosynthesis of polycyclic natural products from conjugated polyenes via tandem isomerization and pericyclic reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13520–13525 (2023).

Trotter, E. W., Collinson, E. J., Dawes, I. W. & Grant, C. M. Old yellow enzymes protect against acrolein toxicity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 4885–4892 (2006).

Yamauchi, Y., Hasegawa, A., Taninaka, A., Mizutani, M. & Sugimoto, Y. NADPH-dependent reductases involved in the detoxification of reactive carbonyls in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 6999–7009 (2011).

Dess, D. B. & Matrin, J. C. A useful 12-I-5 triacetoxyperiodinane (the Dess–Martin periodinane) for the selective oxidation of primary or secondary alcohols and a variety of related 12-I-5 species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 7277–7287 (1991).

He, B.-B. et al. Enzymatic pyran formation involved in xiamenmycin biosynthesis. ACS Catal. 9, 5391–5399 (2019).

Minami, A. et al. Allosteric regulation of epoxide opening cascades by a pair of epoxide hydrolases in monensin biosynthesis. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 562–569 (2014).

Ye, Q. et al. Construction and coexpression of a polycistronic plasmid encoding carbonyl reductase and glucose dehydrogenase for production of ethyl (S)-4-chloro-3-hydroxybutanoate. Bioresour. Technol. 101, 6761–6767 (2010).

Ahrendt, K. A., Borths, C. J. & MacMillan, D. W. C. New strategies for organic catalysis: the first highly enantioselective organocatalytic Diels−Alder reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 4243–4244 (2000).

Kennedy, C. R., Lin, S. & Jacobsen, E. N. The cation–π interaction in small-molecule catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12596–12624 (2016).

Yamada, S. Cation−π interactions in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 118, 11353–11432 (2018).

Bruner, S. D., Norman, D. P. & Verdine, G. L. Structural basis for recognition and repair of the endogenous mutagen 8-oxoguanine in DNA. Nature 403, 859–866 (2000).

Wlodawer, A. et al. Carboxyl proteinase from Pseudomonas defines a novel family of subtilisin-like enzymes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 8, 442–446 (2001).

Robinson, A. C., Castañeda, C. A., Schlessman, J. L. & García-Moreno, E. B. Structural and thermodynamic consequences of burial of an artificial ion pair in the hydrophobic interior of a protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 11685–11690 (2014).

Lehwess-Litzmann, A. et al. Twisted Schiff-base intermediates and substrate locale revise transaldolase mechanism. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 678–684 (2011).

Sautner, V. et al. Converting transaldolase into aldolase through swapping of the multifunctional acid–base catalyst. Biochemistry 54, 4475–4486 (2015).

Xu, G. C. & Poelarends, G. J. Unlocking new reactivities in enzymes by iminium catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202203613 (2022).

Erkkilä, A., Majander, I. & Pihko, P. M. Iminium catalysis. Chem. Rev. 107, 5416–5470 (2007).

MacMillan, D. W. C. The advent and development of organocatalysis. Nature 455, 304–308 (2008).

Sun, Z. et al. Iminium catalysis in natural Diels–Alderase. Nat. Catal. 8, 218–228 (2025).

Du, Y. L. & Ryan, K. S. Pyridoxal phosphate-dependent reactions in the biosynthesis of natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 36, 430–457 (2019).

Gefflaut, T., Blonski, C., Perie, J. & Willson, M. Class I aldolases: substrate specificity, mechanism, inhibitors and structural aspects. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 63, 301–340 (1995).

Sheng, X. & Himo, F. Enzymatic Pictet–Spengler reaction: computational study of the mechanism and enantioselectivity of norcoclaurine synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 11230–11238 (2019).

Pfeiffer, M. & Nidetzky, B. Reverse C-glycosidase reaction provides C-nucleotide building blocks of xenobiotic nucleic acids. Nat. Comm. 11, 6270 (2020).

Ren, D., Lee, Y. H., Wang, S. A. & Liu, H.-W. Characterization of the oxazinomycin biosynthetic pathway revealing the key role of a nonheme iron-dependent mono-oxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 10968–10977 (2022).

Zhou, Z. & Roelfes, G. Synergistic catalysis in an artificial enzyme by simultaneous action of two abiological catalytic sites. Nat. Catal. 3, 289–294 (2020).

Yu, M. Z. et al. An artificial enzyme for asymmetric nitrocyclopropanation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes-design and evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401635 (2024).

Garrabou, X., Wicky, B. I. M. & Hilvert, D. Fast Knoevenagel condensations catalyzed by an artificial Schiff base-forming enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6972–6974 (2016).

Leveson-Gower, R. B., Zhou, Z., Drienovská, I. & Roelfes, G. Unlocking iminium catalysis in artificial enzymes to create a Friedel–Crafts alkylase. ACS Catal. 11, 6763–6770 (2021).

Akey, D. L. et al. Structural basis for macrolactonization by the pikromycin thioesterase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 537–542 (2006).

Tsai, S.-C. et al. Crystal structure of the macrocycle-forming thioesterase domain of the erythromycin polyketide synthase: versatility from a unique substrate channel. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14808–14813 (2001).

Blankenstein, J. & Zhu, J. P. Conformation-directed macrocyclization reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 1949–1964 (2005).

Luo, M. & Wing, R. A. An improved method for plant BAC library construction. Methods Mol. Biol. 236, 3–20 (2003).

Bierman, M. et al. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene 116, 43–49 (1992).

Winter, G. et al. DIALS as a toolkit. Protein Sci. 31, 232–250 (2022).

Agirre, J. et al. The CCP4 suite: integrative software for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 79, 449–461 (2023).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Lebedev, A. A. & Isupov, M. N. Space-group and origin ambiguity in macromolecular structures with pseudo-symmetry and its treatment with the program Zanuda. Acta Crystallogr. D 70, 2430–2443 (2014).

Murshudov, G. N. et al. REFMAC 5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D 67, 355–367 (2011).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Powell, H. R., Battye, T. G. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O. & Leslie, A. G. W. Integrating macromolecular X-ray diffraction data with the graphical user interface iMosflm. Nat. Protoc. 12, 1310–1325 (2017).

Yu, F. et al. Aquarium: an automatic data-processing and experiment information management system for biological macromolecular crystallography beamlines. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 52, 472–477 (2019).

Adams, P. D., Mustyakimov, M., Afonine, P. V. & Langan, P. Generalized X-ray and neutron crystallographic analysis: more accurate and complete structures for biological macromolecules. Acta Crystallogr. D 65, 567–573 (2009).

Acknowledgements

H.M.G. acknowledges funding support from the NSFC (82525108, 22193071, 22437003, W2412037 and 22377051), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20253010 and BF2025075), Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZDYF2023SHFZ107), Fundamental and Interdisciplinary Disciplines Breakthrough Plan of the Ministry of Education of China (JYB2025XDXM507) and the Fundamental Research Fund for the Central Universities (14380205). B.Z. acknowledges funding support from the NSFC (22277051) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20220123). We thank beamlines BL02U1, BL10U2 and BL19U1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for assistance with the X-ray data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.L., B.Z. and H.M.G. conceived the idea for the study and designed the experiments. C.L.L., C.Y.Y. and Z.J.W. performed fermentation, compound isolation, chemical synthesis and all biochemical studies. B.Z., A.Z. and A.L. performed crystallization and solved all the structures. S.Y.W. and Z.Y.Y. assisted in NMR and MS data measurement and analysis. Y.I. and R.X.T. contributed materials and equipment. C.L.L, B.Z. and H.M.G. wrote the manuscript. B.Z. and H.M.G. supervised the work. All authors discussed the results and analysed the data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Synthesis thanks Robin Teufel and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Thomas West, in collaboration with the Nature Synthesis team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

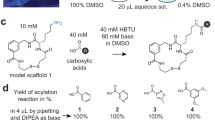

Extended Data Fig. 1 HPLC analysis of DMP oxidation reactions of 6a and 6b.

6a, 6b accumulated in ΔakaM mutant strain were probably derived from the reduction of 5a and 5b, by an endogenous reductase. DMP oxidation of 6a, 6b were carried out to obtain corresponding aldehyde products 5a and 5b. DMP: Dess–Martin periodinane.

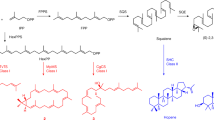

Extended Data Fig. 2 Biochemical evidences of Michael addition catalysed by AkaM or its homologues.

Standard of 5b obtained from DMP oxidation of 6b (i); standard of 5a obtained from DMP oxidation of 6a (ii); standard of 8 (iii); HPLC analysis of non-enzymatic products 5 generated in AkaP1-catalysed reaction, which is conducted in an optimized condition (iv); high-revolution HPLC analysis of one-pot enzymatic reactions of AkaP1 and AkaM or its homologues (v-x).

Extended Data Fig. 3 In vitro kinetic studies of AkaM with different substrates.

a, In vitro enzymatic activity assays of AkaM using 5a as substrate. b, In vitro enzymatic activity assays of AkaM using 5b as substrate. n = 3 replicates and data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Crystal structures of NTF2-like proteins and characterized enzymatic reactions.

a, Crystal structures of AkaM, SacM, CatM and MicM. b, The superimposed image of the four homologues. c, Representative crystal structures of NTF2-like proteins, including NgnD, SdnG, SnoaL, and tKSI. d, Diverse enzymatic reactions catalysed by NTF2-like proteins.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Highly conserved residues in these NTF2-like proteins.

a, Residues surround the K113 and distance between K113, W31, and D101. b, Residues around K113 are highly conserved across these NTF2-like proteins. c, Residues located at the side of active tunnel in AkaM. d, Residues located at the side of active tunnel in CatM. e-f, The two different geometries of active side tunnel in AkaM and CatM. The AkaM, SacM, CatM, and MicM are shown in green, wheat, lime, and light blue, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Crystal structures of SacM in complex with substrate analogue 3 and 6b.

a, Close-up active site view of SacM-3. Compound 3 and the surrounding residues within 4 Å are shown in cyan and wheat, respectively. The polder (omit) electron density map of 3 (contoured at 3.0 σ) is displayed in grey mesh. b, Close-up view of the active site in SacM-6b. Compound 6b and the surrounding residues within 4 Å are shown in light pink and wheat, respectively. The polder (omit) electron density map of 6b (contoured at 3.0 σ) is shown in grey mesh. Compounds 3 and 6b are coloured as cyan and light pink, respectively, while SacM is shown in wheat.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Comparation of CatM-6b, CatM-W86A-6a and SacM-3 crystal structures.

a, Overlay of CatM-6b (lime) and CatM-W86A-6a (light blue). The two flexible loop regions are highlighted by red circles. b, the overlay of CatM-6b and CatM-W86A-6a shows a steric clash between W86 and ligand 6a. c, The crystal structure of CatM-W86A-6a. No water molecule was built within 4 Å of ligand 6a, by Phenix. d, The crystal structure of SacM-3. One water molecule was built in the active cavity by Phenix, which may function as general base for the deprotonation of key lysine. Similar water molecules were also observed in crystal structures of AkaM, SacM, CatM, MicM and SacM-6b.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Experimental methods, Supplementary Tables 1–15 and Figs. 1–111.

Supplementary Data

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 23.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for HPLC analysis.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for HPLC analysis.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for enzymatic reaction analysis.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Source data for HPLC analysis.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Source data for HPLC analysis.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Source data for kinetic analysis.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, C.L., Zhang, B., Yuan, C.Y. et al. Structural and mechanistic insights into iminium-catalysed macrocyclization by nuclear transport factor 2-like enzymes. Nat. Synth (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-025-00989-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-025-00989-z