Abstract

Glaucoma is a leading cause of blindness, featuring elevated intraocular pressure and consequential optic nerve damage1. While elevated intraocular pressure is due to impaired ocular fluid outflow through both the trabecular meshwork (TM) and the lymphatic-like Schlemm’s canal (SC) endothelium, the mechanism by which SC endothelium regulates fluid outflow in cooperation with the TM in healthy and glaucomatous conditions remains unclear. Here we create a human ocular fluid outflow on-chip, composed of a three-dimensional lymphatic or SC endothelium surrounded by TM and draining interstitial fluid. Using the system, we recapitulate steroid-induced glaucoma, characterized by decreased fluid outflow and tightened SC endothelial junctions. We further reveal that the glaucoma phenotypes are induced by an ALK5/VEGFC-mediated SC endothelial dysfunction in the presence of TM. The ocular fluid outflow on-chip provides a unique platform for bridging traditional in vitro and in vivo models of ocular lymphatic physiology and disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of blindness in the world1. Elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) stands as the most prevalent risk factor for glaucoma because sustained high IOP can damage retinal ganglion cells that propagate visual stimuli to the brain. Although steroids are widely used in clinics for treating inflammation-related ocular conditions, such as allergic conjunctivitis, uveitis, dry eye syndrome and general eye infections, a common side effect of steroids is elevated IOP and increased risk of glaucoma with unclear mechanisms.

Aqueous humor (AH) outflow occurs through the TM and SC pathway, which is often impaired in glaucoma and leads to elevated IOP as described in Fig. 1a; however, examining TM–SC interactions has been challenging in conventional animal models where the biological and biophysical factors are tightly coupled, making it difficult to isolate and control those factors. To address the challenge, in vitro models of TM2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, SC11,12,13 or both TM and SC14 have been developed; however, these previous in vitro models have not fully recapitulated the native architecture of three-dimensional (3D) SC endothelium surrounded by TM, and more notably, they could not examine the AH outflow mechanisms through the juxtaposed 3D multicellular structure.

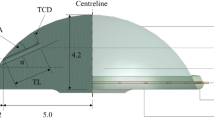

a, IOP is regulated by AH outflow through the TM and SC. This schematic was created in BioRender. b, A schematic of the microfluidic device and steps for generating the TM–SC double-layered channel structure. The M-shaped needle guide plays a role in keeping different-sized needles centered in a reproducible manner. c, Immunostaining of the TM cells and LECs in the device using phalloidin (actin, red) and anti-CD31 antibodies (yellow). Actin-rich TM cells surround the rudimentary lymphatic endothelium. Images shown are representative of three independent experiments that yielded similar results. d, A schematic procedure of the ocular fluid outflow experiment to determine the average outflow rate. We pressurized the acellular channel with excess medium, and the differential pressure between the two channels induced fluid transport to the cellular channel. Fluid collected by the cellular channel accumulated in the connected reservoirs and was collected for analysis of the flow rate. e, Average flow rate after DEX treatment (1 μM) for 7 days in TM + LEC coculture or LEC monoculture in the ocular fluid outflow on-chip (n = 7, 6, 8 and 8 chips, respectively). f, VE-cadherin/CD31/actin staining of the cells before and after DEX treatment (1 μM) in the TM + LEC coculture or the LEC monoculture. g, Zoomed in VE-Cad images in the TM + LEC coculture or the LEC monoculture with or without DEX. h, LEC junction widths before and after DEX treatment (1 μM) in the TM + LEC coculture or the LEC monoculture (n = 10, 10, 8 and 8 fields of view (FOVs) in 7, 6, 8 and 8 chips, respectively). Experiments described in e–h were performed using commercially available TM cells (ScienCell). Scale bars, 50 μm (b,c), 100 μm (f) and 25 μm (g). All data are presented as mean ± s.d. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test (two-sided) (e,h). Exact P values are shown (e,h).

To address the limitations, we created a human ocular fluid outflow on-chip, composed of a 3D lymphatic-like SC endothelium that is surrounded by TM cells and drains interstitial ocular fluid (Fig. 1b). The device consists of a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) housing and two parallel cylindrical channels embedded in a 3D collagen hydrogel (extracellular matrix (ECM) region) (Fig. 1b). To enable the appropriate multicellular architecture of TM and SC, an M-shaped needle guide was created by using soft lithography processes (Extended Data Fig. 1). The M-shaped needle guide enabled the introduction of two needles of different sizes into the device to reproducibly build up a double-layered cellular channel structure. In brief, we created a channel within collagen by inserting a needle (diameter 400 μm) and casting collagen on top of it (Fig. 1b, Step 1). Then, the needle was removed, and we created a TM cell layer by inserting a smaller needle (250 μm) and introducing TM cell suspension in collagen gel to the space between the larger channel and the smaller needle (Fig. 1b, Step 2). The TM cells we used were characterized by their morphology and marker expression, such as dexamethasone-induced myocilin upregulation (Extended Data Fig. 2)15. After completing the TM-containing collagen layer, we removed the smaller needle and seeded SC endothelial cells suspended in medium in the smaller channel (Fig. 1b, Step 3). Given that SC cells are lymphatic-like endothelial cells expressing lymphatic endothelial markers Prox1 and vascular endothelial growth factor 3 (VEGFR3), and respond to a lymphangiogenic growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGFC)16,17,18, we tested human lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) in the SC channel, as a proof of concept. To ensure the robustness of our findings, we subsequently confirmed key results using primary human SC endothelial cells, as detailed in Fig. 3. We also confirmed the identity of the cells used in our study through immunofluorescence staining for key markers of LECs, SC cells and TM cells19,20. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 3, LECs expressed the lymphatic endothelial marker (Prox1), while SC cells selectively expressed nephronectin (NPNT) and ITGA9, known SC markers, confirming their distinct identity. For TM validation, we assessed TIMP3, Myocilin, Versican and Angpt1, which are known as TM cell markers, and these markers were highly expressed in TM cells compared to other endothelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 3). After seeding the cells, we introduced luminal shear stress by putting the device on a rocking platform for 2–3 days. After that, we examined the TM-LEC structure via immunofluorescence by staining the devices with phalloidin and anti-CD31 antibodies to visualize actin-rich TM cells and CD31-positive LECs. The 3D rendered and cross-sectional images showed that TM cells (red) nicely covered the endothelium (yellow) (Fig. 1c).

Using the device as an ocular fluid outflow on-chip required evaluating the interstitial AH outflow through the double-layered cellular channel. To accomplish this, we pressurized the acellular channel, and the differential pressure between the two channels induced interstitial fluid transport to the cellular channel. Fluid outflow through the cellular channel accumulated in the connected reservoirs and was collected to calculate the fluid outflow rate (Fig. 1d). The outflow rate was determined by dividing the total outflow volume by the product of the time duration and the surface area of the TM–SC channel. The measured flow rate (average flow velocity) ranged between 1.5–2 μm s−1, which is physiologically relevant, as it closely approximates the AH outflow rate in the human eyes (average flow velocity 2.8–5.7 μm s−1) (the mathematical details are in Methods, Ocular fluid outflow assay)21,22,23. To examine the impact of interstitial flow on cell identity in the coculture, we conducted Transwell-based experiments to analyze gene expression changes under these different conditions. Our qPCR analysis confirmed that the identity of LECs and TM cells were not significantly affected by the interstitial flow in the coculture conditions (Extended Data Fig. 4); however, we revealed that coculture of SC cells and TM cells under interstitial flow enhanced SC expression of lymphatic endothelial markers, such as Prox1 and VEGFR3, highlighting the roles of interstitial flow and TM–SC interactions in maintaining SC endothelial cells to be more lymphatic-like (Extended Data Fig. 4). Moreover, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging of SC cells and LECs with or without TM cells revealed the formation of giant vacuole-like structures in the TM-cocultured conditions, resembling those observed in SC endothelium in vivo (Extended Data Fig. 5).

Given that steroids are widely used in treating inflammation-related ocular conditions, but undesirably elevate IOP and increase the risk of glaucoma, dexamethasone (DEX), a synthetic glucocorticoid that simulates steroid conditions, was tested in our model. In the coculture (TM + LEC) condition, DEX, at the concentration of 1 μM for 7-day exposure, markedly decreased fluid outflow, compared to the dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle (Fig. 1e, left). As controls, we tested LEC monoculture without TM cells, observed that fluid outflow was lower than that in the coculture, and did not see any significant changes after DEX treatment (Fig. 1e, right). Additionally, we examined the TM cell monoculture without LECs and found no significant change in fluid outflow with DEX treatment (Extended Data Fig. 6). Notably, both TM cells and LECs were required to accurately model steroid-induced glaucoma. We next examined the junctional structures of the endothelial cells in the devices via immunofluorescence using anti-VE-cadherin (VE-Cad) antibodies, anti-CD31 antibodies and phalloidin to visualize adherens junctions in CD31+ endothelium, surrounded by actin-rich TM cells (Fig. 1f). In the coculture, we discovered tightened and thickened endothelial adherens junctions after DEX treatment, compared to DMSO controls (Fig. 1f, left). LEC monoculture conditions showed more elongated junctions than the coculture conditions, with no significant changes by DEX treatment (Fig. 1f, right). We zoomed in on the VE-Cad images (Fig. 1g) and analyzed the endothelial junction widths (Fig. 1h). While the healthy coculture group showed thinner junctions, the DEX-treated coculture group displayed thicker LEC junctions (Fig. 1g,h). LEC monoculture showed elongated and more compact junctions. Taken together, our ocular fluid outflow on-chip recapitulated steroid-induced glaucoma, requiring both TM cells and LECs.

To begin to characterize what signaling pathways might be involved in glaucoma formation in our human ocular fluid outflow on-chip model, we screened potential targets for glaucoma using a machine-learning tool, NicheNet, that can identify ligands that are expressed in glaucoma based on single-cell RNA sequencing data from healthy and diseased tissues20,24. The NicheNet identified vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, also known as VEGFA), TGF-β, interleukin (IL)-6 and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) as the top four ligands in glaucoma (Extended Data Fig. 7). Among them, the TGF-β pathway has been studied in glaucoma, focusing on TM, evidenced by the higher TGF-β expression and stiffer TM in the glaucomatous condition than in the healthy condition25,26. Nonetheless, it is currently unknown whether TGF-β plays a role in SC endothelium and its outflow function in glaucoma. We tested SB431542 (10 μM), a TGF-β receptor (TGFβR) inhibitor, in our human ocular fluid outflow on-chip model (Fig. 2a). DEX (1 μM) treatment showed impaired fluid outflow in the model compared to DMSO controls, here, the SB431542 (10 μM) treatment normalized the fluid outflow rate (Fig. 2a). We assessed the cellular structures via immunofluorescence by staining the cells with anti-VE-Cad antibodies (Fig. 2b) and phalloidin (Extended Data Fig. 8), observing that DEX-treated group showed thicker LEC junctions, compared to DMSO controls, while the SB431542 treatment made the LEC junctions normalized to the control level (Fig. 2b,c).

a, Average outflow rate after DEX treatment (1 μM) with or without the TGF-β receptor inhibitor (SB431542, 10 μM) in the TM + LEC coculture chip (n = 7, 6 and 6 chips, respectively). b, VE-Cad/4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) images after DEX treatment with or without SB431542 treatment. c, LEC junction widths after DEX treatment with or without SB431542 (n = 10, 11 and 11 FOVs in 7, 6 and 6 chips, respectively). d, IOP measured in the steroid (DEX)-induced mouse glaucoma model with or without TGF-β receptor inhibitor treatment (SB431542, 10 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. injection, n = 5 mice). e, Prox1 (a lymphatic-like SC endothelial marker) and VE-Cad (an adherens junction marker) staining of mouse SC endothelium in the steroid-induced glaucoma model with or without SB431542 treatment. f, Junction widths of the SC endothelium in the steroid-induced glaucoma models with or without SB431542 treatment in vivo (n = 5 mice). Experiments described in a–c were performed using commercially available TM cells (ScienCell). Scale bars, 25 μm (b) and 20 μm (e). All data are presented as mean ± s.d. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (two-sided) (a–d,f). Exact P values are shown in a,c,d,f.

To investigate the potential efficacy of TGF-β receptor (TGFβR) inhibition in vivo, we tested SB431542 in an established mouse model of steroid-induced glaucoma (Fig. 2d–f)27. Glaucoma was induced by periocular injection of dex-21-acetate (20 μl, 10 mg ml−1), a less soluble form of dexamethasone (DEX), which can slowly release DEX locally over weeks27. DMSO was injected as a control. We measured IOP in mouse eyes using the TonoLab rebound tonometer (Colonial Medical Supply) after the dex-21-acetate/DMSO injection. After 7 days, dex-21-acetate-treated mice showed significantly higher IOP than DMSO-treated controls (Fig. 2d). On day 7, we started treating half of the dex-21-acetate-treated mice with SB431542 (10 mg kg−1 day−1, intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection), and measured IOP every 2 days for 6 days (Fig. 2d). On day 13, dex-21-acetate-treated mice showed a higher IOP than DMSO controls, whereas SB431542-treated mice markedly decreased IOP against the dex-21-acetate treatment (Fig. 2d, bottom). On day 13, the mice were killed and their eyes were collected and stained with anti-VE-Cad and anti-Prox1 antibodies to visualize adherens junctions in the Prox1-positive SC endothelium. We showed that SC junctions became thicker in the DEX-treated condition compared to the DMSO controls; here, SB431542 treatment normalized the SC junctions to the control level (Fig. 2e). We further analyzed SC junction widths and confirmed junction tightening in DEX and its normalization by SB431542 in vivo (Fig. 2f). Taken together, TGFβR inhibition reverses DEX-induced glaucoma phenotypes in vitro and in vivo.

While these results suggested a promising avenue of the TGFβR inhibition for treating glaucoma, it remained unclear how DEX-treated conditions could assemble SC endothelial junctions in the presence of TM cells through TGFβR. It is known that VEGFR3 is expressed in SC cells, which enables the cells to respond to a lymphangiogenic growth factor, VEGFC16. Given that SC cells only express VEGFA, but not VEGFC20, and the VEGFC–VEGFR3 axis helps lymphatic junction buttoning and fluid outflow28,29, we hypothesized that VEGFC expression in TM cells is affected by DEX, which impacts SC junctions and fluid outflow. To test this hypothesis, we first examined VEGFC expression in TM cells with or without DEX, showing that VEGFC expression in TM decreased by DEX treatment (1 μM) in the Human Angiogenesis Arrays (Extended Data Fig. 9) and ELISA (Fig. 3a). Here, SB431542 treatment partially recovered the VEGFC expression in TM (Fig. 3a). Next, we sought to determine whether inhibiting VEGFR3, the receptor of VEGFC, affects the SC junction assembly and AH outflow under DEX/SB431542-treated conditions (Fig. 3b). To confirm our LEC-based findings, authenticated primary human SC endothelial cells30 were employed in our ocular fluid outflow on-chip devices, and the devices were treated with MAZ51, a VEGFR3 kinase inhibitor, with or without DEX and SB431542 (Fig. 3b). In the DEX (1 μM)-treated TM + SC condition, the SB431542 treatment (10 μM) normalized the impaired outflow; however, notably, additional MAZ51 (20 μM) treatment diminished the therapeutic effect of the SB431542 (Fig. 3b). To validate this finding in vivo, mouse glaucoma was induced by periocular injection of dex-21-acetate (20 μl, 10 mg ml−1)27. DMSO was injected as a control. On day 7, we started treating one-third of the dex-21-acetate-treated mice with only SB431542 (10 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. injection), and another one-third of the dex-21-acetate-treated mice with both SB431542 (10 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. injection) and MAZ51 (10 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. injection), maintaining these treatments for 6 days and measuring IOP every 2 days (Fig. 3c). On day 13, dex-21-acetate-treated mice showed a higher IOP than DMSO controls, while SB431542-treated mice normalized IOP against the dex-21-acetate injection; however, co-treatment of the glaucomatous group with SB431542 and MAZ51 could not normalize IOP against the dex-21-acetate injection, diminishing the therapeutic effect of the SB431542 (Fig. 3c, right). We further examined mouse SC junctions by immunostaining with anti-VE-Cad and anti-Prox1 antibodies. In vivo SC junctions became thickened in the DEX-treated condition compared to DMSO controls; however, while the DEX effect was reversed by SB431542 treatment, co-treatment of MAZ51 and SB431542 abolished the therapeutic effects of the SB431542 (Fig. 3d), further confirmed by analyzing SC endothelial junction widths (Fig. 3e).

a, ELISA-based examination of VEGFC expression in TM cells with or without DEX and SB431542 (n = 9 wells). b, Ocular fluid outflow on-chip models using human TM and SC cells. To validate the roles of VEGFR3 and TGF-β receptor signaling in DEX-induced glaucoma, the average flow rate after dexamethasone treatment (DEX, 1 μM) with or without TGF-β receptor inhibitor (SB431542, 10 μM) and VEGFR3 kinase inhibitor (MAZ51, 20 μM) was obtained (n = 12, 19, 20 and 19 chips, respectively). c, IOP measured in the steroid-induced mouse glaucoma model with or without SB431542 (10 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. injection) or MAZ51 (10 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. injection) treatments (n = 5 mice). d, Prox1 and VE-Cad staining of mouse SC endothelium in the steroid-induced glaucoma model with or without SB431542 or MAZ51 treatments. e, Junction widths of mouse SC endothelium in the steroid-induced glaucoma model with or without SB431542 or MAZ51 treatments (n = 7, 11, 10 and 13 FOVs in five mice). f, VEGFC expression in TM cells with ALK4, ALK5 or ALK7 knockdown under DEX or DMSO treatment (n = 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 3 and 6 wells, respectively). g, Average flow rate of fluid outflow in TM + SC coculture models using wild-type SC cells and silenced TM cells with ALK4, ALK5, or ALK7 siRNAs under DEX or DMSO treatment (n = 14, 14, 21, 18, 18, 14, 18 and 17 chips, respectively). Experiments described in a,f were performed using commercially obtained TM cells (ScienCell); experiments described in b,g were performed using both commercial TM cells (ScienCell) and primary TM cells isolated from donor eyes (Stamer laboratory). Scale bars, 25 μm (d). All data are presented as mean ± s.d. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (two-sided) in a–c,e; using unpaired two-sided Student’s t-tests in f,g. Exact P values are shown in a–c,e–g.

While these results suggest that SC junctions can be regulated by TGFβR and VEGFR3 signals in TM and SC, SB431542 can target multiple TGFβRs, including ALK4, ALK5 and ALK7. To determine the exact TGFβR that might be responsible for the regulation of VEGFC expression in TM cells, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of ALK4, ALK5 and ALK7 in TM cells (Extended Data Fig. 10). We measured VEGFC expression in TM cells with either ALK4, ALK5 or ALK7 knockdown under the DEX condition (Fig. 3f). In the control group of scrambled siRNA, DEX treatment downregulated VEGFC expression in TM cells. Similarly, in both ALK4 and ALK7 knockdown groups, DEX treatment downregulated VEGFC; however, the ALK5 knockdown group showed no change in VEGFC expression in the presence of DEX (Fig. 3f), demonstrating that steroid-treated TM cells downregulate VEGFC through ALK5. We next performed the fluid outflow experiment in our human ocular fluid outflow on-chip model using those knocked-down TM cells and wild-type SC cells (Fig. 3g). In the control group of scrambled siRNA treatment, DEX impaired fluid outflow. Similarly, in both ALK4 and ALK7 knockdown groups, DEX treatment significantly delayed fluid outflow; however, the ALK5 knockdown group showed no change in fluid outflow in the presence of DEX (Fig. 3g). Taken together, steroid-treated TM cells downregulate VEGFC expression through ALK5, and the lack of VEGFC affects SC cells through VEGFR3, impairing SC junctions and fluid outflow.

To further validate the role of ALK5 in vivo, we performed intracameral injections of ALK5 siRNA into the anterior chamber of mouse eyes to specifically knock down ALK5 expression in the anterior chamber angle. The ALK5 knocked-down group showed reduced ALK5 expression in TM regions, as evidenced by immunofluorescent signal and quantification (Fig. 4a,b). Next, we performed glaucoma experiments on wild-type versus ALK5 knockdown mice with DEX treatment. In the steroid-induced glaucoma model, ALK5 knockdown significantly lowered IOP compared to the control siRNA-treated group (scramble), demonstrating the roles of ALK5 in steroid-induced ocular hypertension (Fig. 4c). We further assessed AH mouse VEGFC levels using ELISA in those groups and found that ALK5 knockdown restored VEGFC secretion against DEX treatment to the level comparable to the nonsteroid (DMSO) controls, supporting our in vitro findings that ALK5 suppresses VEGFC expression in TM cells under DEX exposure (Fig. 4d). Immunostaining of mouse SC endothelium revealed that ALK5 knockdown mitigated the DEX-induced tightening of endothelial junctions, as indicated by VE-Cad staining (Fig. 4e). Quantitative analysis confirmed that SC junction widths were restored to control levels by ALK5 inhibition (Fig. 4f). These results provide strong in vivo evidence that ALK5 mediates steroid-induced SC endothelial dysfunction by downregulating VEGFC expression in TM cells, contributing to impaired AH outflow and elevated IOP.

a, siRNA-mediated knockdown of ALK5 in vivo. Immunofluorescent staining of ALK5, Prox1 and DAPI 48 h after intracameral injection of scramble or ALK5 siRNA. b, Quantification of ALK5 signal normalized by DAPI (n = 8 and 11 FOVs in five mice, respectively). c, IOP measured in the steroid-induced mouse glaucoma model with or without ALK5 knockdown (n = 10 mice). d, AH mouse VEGFC concentration with or without ALK5 knockdown under DEX or DMSO treatment (n = 10, 9, 10 and 10 mice, respectively). e, Prox1 and VE-Cad staining of mouse SC endothelium in the steroid-induced glaucoma model with or without ALK5 knockdown. f, Junction widths of mouse SC endothelium in the steroid-induced glaucoma model with or without ALK5 knockdown (n = 8, 4, 6 and 5 mice, respectively). Scale bars, 100 μm (a) and 25 μm (e). All data are presented as mean ± s.d. Statistical comparisons were performed using unpaired two-sided Student’s t-tests in b; using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (two-sided) in c,d,f. Exact P values are shown in b–d,f.

In this study, we created a 3D biomimetic human ocular fluid outflow on-chip model that contains a 3D lymphatic-like SC endothelium covered by TM cells, which can examine ocular fluid outflow. Using the system, we recapitulated steroid-induced glaucoma and unveiled a previously unrecognized ALK5/VEGFC mechanism in regulating SC endothelial junctions and ocular fluid outflow in steroid-induced glaucoma. Our study highlights that neither TM nor SC can independently form fluid outflow resistance in steroid-induced glaucoma, but both cell types, layered in a juxtaposed manner, are required for properly modeling the normal physiology of ocular fluid outflow as well as glaucoma.

Our human ocular fluid outflow on-chip model offers insights into the impact of TGF-β signaling on TM–SC crosstalk and SC junctional defects by a mechanism of a noticeable decrease in VEGFC expression in TM cells via ALK5, tightening SC junctions through VEGFR3 to impair fluid outflow under steroid conditions. While our findings establish the ALK5/VEGFC pathway as the key regulator of the AH outflow in steroid-induced glaucoma, we acknowledge that glaucoma is a heterogeneous disease with multiple subtypes, including primary glaucoma (open-angle and angle-closure) and secondary glaucoma (such as pseudoexfoliation glaucoma and neovascular)31,32. Further studies are needed to explore the broader applicability of the platform in different glaucoma subtypes. Meanwhile, other critical signaling pathways in glaucoma, such as angiopoietins/Tie2 and Tie1 (refs. 30,33,34), FOXC2 (ref. 35) and leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2)36 are guaranteed for future investigations using the system for drug candidate screening and development. Our work emphasizes how recapitulating appropriate multicellular architectures of TM and SC can enable the investigation of the ocular fluid outflow mechanisms and provide a unique platform for drug screening and mechanistic studies of ocular lymphatic physiology and dysfunction.

Methods

Study design

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with relevant ethical regulations and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cornell University (protocol number 2025-0010). For the in vivo experiments, power analyses were performed to estimate the minimum animal group size based on the results observed in preliminary studies. The 6-week-old C57BL/6J wild-type female mice were used for the glaucoma experiments. Although glaucoma is generally not considered sex-related, we opted to use only female mice in our experiments to minimize potential sources of variability: male mice are prone to fighting and psychological stress, which have been shown to significantly influence IOP37. Animals were randomly assigned to control and treatment groups, and all the experimenters were double-blinded. All experimental sample numbers (biological replicates) are indicated in the figure legends. Mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled, AAALAC-accredited animal facility at Cornell University, with a 12-h light–dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 and off at 19:00), ambient temperature maintained at 20–24 °C and humidity at 40–60%.

Cell culture

Three cell strains of human TM cells were either purchased from ScienCell or isolated from donated human eyes (Stamer laboratory)27. Specifically, the experiments in Figs. 1e–h, 2a–c and 3a,f and Extended Data Figs. 2, 6 and 8–10 were conducted using commercially available TM cells; the experiments in Figs. 3b,g and Extended Data Figs. 3–5 were performed using both commercial TM cells and primary TM cells isolated from donor eyes. Commercially obtained TM cells were cultured in Trabecular Meshwork Cell Medium (ScienCell), and TM cells isolated from donor eyes (Stamer laboratory) were cultured in 5 mM low-glucose DMEM (Gibco) with 10% high-quality fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus 1× penicillin–streptomycin–glutamine (PSG; Gibco). Primary human dermal LECs, isolated and characterized by Y. K. Hong (USC)38 were kindly donated. Human LECs were used to initially model SC endothelium, given that SC cells are ocular hybrid blood/lymphatic endothelium expressing lymphatic endothelial markers (Prox1 and VEGFR3)16,17,18. LECs were grown in EGM-2MV medium (Lonza). Key findings in LECs were confirmed using primary human SC endothelial cells, which were isolated and characterized using established methods (Stamer laboratory)39,40. Primary human SC cells were cultured in 5 mM low-glucose DMEM (Gibco) with 10% high-quality FBS plus 1× PSG (Gibco). In all experiments, TM cells were used in passage 4, LECs were used in passage 7 and SC endothelial cells were used in passage 3. All the cells were maintained in standard tissue culture incubators at 37 °C with 95% humidity and 5% CO2.

Microfluidics

The ocular fluid outflow on-chip device was fabricated using a soft lithography method, consisting of two parallel cylindrical microchannels in the 3D collagen hydrogel. To keep the TM layer uniform in all regions, surrounding the lymphatic- or SC channel, we created an M-shaped needle-guiding pattern located in the needle-guiding region (Fig. 1b). The two small support bins keep the small needle centered, but will not affect large needles as they can be easily deformed. Such an M-shaped channel involves a complex overhanging structure, which is difficult to fabricate using traditional lithographic methods. Hence, we used the ‘sandwich method’ to fabricate the pattern from upside down. The M-shaped needle-guiding pattern consists of three SU-8 layers: the topmost wide layer, the middle layer with the supporting bins, and the bottom narrow layer (Extended Data Fig. 1). All the photo masks of the three layers were designed with L-edit computer-aided design software (v.15, Tanner EDA by Mentor Graphics Corp.) and engraved on 5-inch-chromium masks by a laser pattern generator (DW2000, Heidelberg Instruments). To fabricate the M-shaped SU-8 pattern with a sandwich method, we created the pattern upside down in a ‘pattern wafer’ and then transferred it to another ‘mold wafer’. In the pattern wafer, we first coated a 17-nm-thick sacrificial layer of OmniCoat on a silicon wafer. Then, we created the ‘W’ shape pattern (the upside down of the ‘M shape’ shape) layer by layer using a 300-μm-thick layer of SU-8 2150 (the topmost wide layer) and two 100-μm-thick layers of SU-8 2100 (the middle layer with supporting bins and the bottom narrow layer, respectively). Simultaneously, a 50-μm-thick layer of SU-8 50 was coated and flood-exposed on the mold wafer. Afterward, the mold wafer and pattern wafer were joined together facing each other, and experienced post-exposure baking (PEB). After PEB, SU-8 patterns on the two wafers were bound together. The OmniCoat sacrificial layer was removed with alkaline developer MF319, and the remaining (uncrosslinked) SU-8 materials were removed with the SU-8 developer so that all patterns were transferred right-side up to the mold wafer. The surface of the fabricated mold wafer was treated by a monolayer of FOTS ((tridecafluoro1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl)-trichlorosilane) through the molecular vapor deposition system (MVD 100, Applied MicroStructure) to prevent polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) adhesion to the wafer and SU-8 structures during PDMS casting. All SU-8 photoresists, OmniCoat and developers were purchased from Kayaku Advanced Materials and were UV-exposed using an ABM Manual Mask Aligner (ABM-USA). PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning, DC2065622) was mixed with a curing agent, provided in the Sylgard 184 PDMS kit, at a 10:1 weight ratio (base:curing agent) and cured on a silicon master wafer overnight at 80 °C. Then, the PDMS was removed from the wafer and trimmed. Reservoir and collagen entries were made with 6-mm and 2-mm biopsy punches (Integra), respectively. The device was assembled by bonding the PDMS gasket on top of a glass coverslip with plasma etching and overnight incubation at 80 °C. The nanofabrication was performed in the Cornell NanoScale Facility (CNF).

Cell seeding in microfluidics

The devices were plasma etched and treated with 0.01% poly-l-lysine (Sigma, P8920) for 1 h, followed by 1% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, 16310) for 30 min and then rinsed three times with sterile water, and incubated overnight in sterile water at room temperature. The next day, large steel acupuncture needles (0.40 × 50 mm, Hawato) were sterilized with 70% ethanol and 1 mg ml−1 BSA-coated (Sigma), then introduced into the devices as a scaffold of a ‘casting method’. The needle-inserted devices were air-gun dried and UV sterilized for 30 min. Collagen type I (Corning, 356236) was buffered with PBS, and titrated to a pH of 8.0 with NaOH (Sigma), yielding a final concentration of 2.5 mg ml−1, which was pipetted into the microfluidic devices and polymerized for 1 h at 37 °C. Cell growth medium was then added to the devices overnight, and needles were carefully removed to create 400-μm diameter channels in the collagen gel. After overnight incubation with a cell growth medium, the devices were seeded with TM cells. In brief, enzymatically dislodged (0.05% trypsin/EDTA, Gibco) TM cells were resuspended at 2 × 106 cells per ml in 3.3 mg ml−1 collagen type I and 50 μl of cell suspension was introduced into the right-side reservoirs. Then, sterilized and BSA-coated smaller steel acupuncture needles (0.25 × 50 mm, Hawato) were inserted into the right-side channel, introducing the cell suspension into the right-side channel, and the device was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Afterward, TM medium was added to the devices. The small needles were carefully removed after overnight incubation, and human LECs or human SC cells were seeded the day after. Enzymatically dislodged (0.05% trypsin/EDTA, Gibco) endothelial cells were resuspended at 2 × 106 cells per ml in full medium and 100 μl of cell suspension was introduced into the right-side channel of the device via the media reservoirs that are connected to the right-side channel, allowing cells to adhere to the collagen matrix for 10 min before washing with growth medium. The devices were incubated on a rocking platform in a humidified tissue culture incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C), replenishing culture medium daily.

Ocular fluid outflow assay

After culturing cells in the device for 2–3 days on a rocking platform, we introduced higher hydraulic pressure to the left-side media reservoirs connected to the left-side acellular channel to measure the ocular fluid outflow in the device. Having 50 μl of medium in both channels with equal volumes (25 μl left, 25 μl right), we additionally added excess medium to the left side of the channel, making a 7-mm fluid height difference between the two channels. During the outflow experiment, the devices were put on the rocking platform to maintain luminal shear flow in the channels. After 12 h, fluid in the left-side reservoirs and the right-side reservoirs was gathered, and the average outflow rate was calculated by dividing the total outflow volume by the product of the time duration and the surface area of the TM–SC channel. The measured flow rate (average flow velocity) ranged between 1.5–2 μm s−1, which is physiologically relevant, as it closely approximates the AH outflow rate in the human eyes (average flow velocity 2.8–5.7 μm s−1). According to Yan et al.21, the average width of the human SC is approximately 233.0 ± 34.6 μm. Lewczuk et al.22 reported that the perimeter of the canal is approximately 36–40 mm. Assuming an average perimeter of 38 mm, we can estimate the total outflow surface area:

The average AH flow rate in the human eye is reported to be 1.5–3.0 μl min−1 (ref. 23), which is 0.025−0.05 μl s−1.

To calculate the average outflow velocity v, we divide the volumetric flow rate Q by the cross-sectional outflow area A:

So, the estimated average flow velocity across the SC wall is approximately 2.8–5.7 μm s−1.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescent staining and imaging of the ocular fluid outflow on-chip devices, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, 15710) in EBM2 (Lonza, CC-3156) for 1 h at room temperature. Fixed devices were permeated with PBST (0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 45 min at room temperature and then blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) in PBS overnight at 4 °C. For cell marker gene analysis, cells (LEC, SC and TM cells) cultured on cover glass were processed using a regular staining protocol for fixation, permeabilization and blocking. For both setups, primary antibodies detecting Prox1 (Angiobio, 11-002P, 1:100 dilution), VE-Cad (Santa Cruz, sc9989, 1:100 dilution), CD31 (Invitrogen, PA5-143217, 1:100 dilution), pMLC (Cell Signaling, 3671L, 1:100 dilution), myocilin (Santa Cruz, sc137233, 1:100 dilution), Angpt1 (R&D Systems, MAB923-SP, 1:100 dilution), NPNT (Santa Cruz, sc393033, 1:100 dilution), ITGA9 (R&D Systems, PA5-27771, 1:100 dilution), TIMP3 (Abcam, ab39184, 1:100 dilution) and Versican (Abcam, ab177480, 1:100 dilution) were incubated in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. After incubation with primary antibodies, the samples were washed for 24 h in PBS at 4 °C. Secondary antibodies (all from Life Technologies, 1:500 dilution), phalloidin (Life Technologies, A22287, 1:200 dilution) and DAPI (Sigma, 1:500 dilution) were subsequently incubated in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C in the dark. The secondary antibodies, phalloidin, and DAPI were washed for 24 h in PBS at 4 °C in the dark to remove the fluorescent background before confocal microscopy. Confocal images were acquired with an inverted Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica). With the images we obtained, we performed the maximum z-projections and 3D rendering and adjusted for brightness and contrast using ImageJ41.

NicheNet cellular interaction analysis

Based on the R studio platform, NicheNet was used to determine the ligands underlying the permeability-associated expression changes in glaucoma. This algorithm took two different inputs: single-cell RNA-seq data of normal TM and SC cells20,24, and the list of permeability-related genes (obtained from GeneCards database). Output ligands were prioritized by their predicted activity and paired with genes according to their regulatory potential. Relevant code and data can be found in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/lurenhaothu/Nichenet-analysis-TM-SC-glaucoma.

Mouse steroid-induced glaucoma model

The mouse steroid-induced glaucoma model was described previously27. An 80 mg ml−1 dexamethasone 21-acetate (dex-21-acetate, Sigma, D1881) stock solution was prepared by dissolving 80 mg of dex-21-acetate powder in 1 ml of DMSO and stored at −20 °C. Before injection, the dex-21-acetate stock was diluted in PBS to form a 10 mg ml−1 stock solution for injection. For periocular injection, a 31-gauge insulin needle (Butler Schein Animal Health, 55956) was used. The lower eyelid was retracted, and the needle was inserted through the conjunctival fornix. Dex-21-acetate or DMSO vehicle (20 μl) was injected over the course of 10–15 s. At day 7 of dex-21-acetate or DMSO treatment, parts of animals were treated with SB431542 (10 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. injection), or both SB431542 (10 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. injection) and MAZ51 (10 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. injection) for additional 6 days. Throughout the experiments, IOP was measured in anesthetized mice using a TonoLab rebound tonometer (Colonial Medical Supply) every other day between 10:00 and 14:00.

Whole-mount staining and 3D imaging of mouse Schlemm’s canal

After killing animals, the mouse eyes were dissected and the whole mount was stained using the protocol previously described42. We placed the collected eyes in a 10-cm tissue dish filled with TBS under a dissecting microscope and removed conjunctiva and connective tissues using fine scissors and forceps. Then, we cut the optic nerves that emerged from the globe with scissors, made an incision from the optic nerves to the center of the cornea, and removed the lower one-third of the sclera. The lens and retina were also removed from the sclera opening. After dissection, we fixed the eyes by immersing them in 4% fresh-made PFA at 4 °C for 1 h in a 24-well plate. After washing excess PFA with PBS three times, we blocked the eyes with 10% heat-inactivated goat serum (Abcam) diluted in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 (TX-100) blocking buffer for 30 min with gentle mixing at room temperature. Primary antibodies detecting VE-cadherin (BD Biosciences, 555289, 1:50 dilution) and Prox1 (Angiobio, 11-002P, 1:50 dilution) were incubated in a blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. After incubation with primary antibodies, the samples were washed with 2% heat-inactivated goat serum diluted in PBS with 0.2% TX-100 washing buffer three times for 15 min each time at room temperature. Secondary antibodies (all from Life Technologies, 1:100 dilution), were subsequently incubated in a blocking buffer for 1 h at 4 °C in the dark. The secondary antibodies were then washed in washing buffer three times, for 15 min each in the dark to remove the fluorescent background before confocal microscopy. After staining, we placed the eyes on clean microscope slides with a drop of TBS and used fine scissors to make a series of cuts through the sclera toward the limbus and a similar series of cuts from the center of the cornea toward the limbus under the dissection microscope. Such cuts enabled us to unroll the eye and flatten it against the slide, with the inner surface facing upwards. We then used tissue paper to slowly aspirate TBS from the surface of the slide, gently placed a drop of mounting medium onto the slide, and covered it with a cover glass. Confocal images were acquired with an inverted Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica). With the obtained images, we performed maximum z-projections and brightness and contrast adjustments using ImageJ41.

Quantification of endothelial junction widths

We quantified LEC and SC endothelial junction width in vitro based on VE-Cad staining images with ImageJ41. In brief, we used the segmented line tool to draw lines that are equal to the junction width and measured their length using the ‘Measure’ function. To quantify SC endothelial junction width in vivo, we developed a custom Python script that automates measurements from VE-Cad immunofluorescence images. The algorithm first generates a binary mask by applying a custom intensity threshold to distinguish VE-Cad-positive junctions from the background. It then randomly selects points within the VE-Cad-positive regions and measures the junction width by determining the shortest path through the point across the junction structure, defined as the minimum sum of distances to the first VE-Cad-negative regions on either side. For both methods, ten fields of view were randomly chosen and masked from each sample for quantification. The Python script is available at https://github.com/lurenhaothu/Junction-Measurement.

ELISA and antibody array kit analysis

TM-conditioned medium was collected for ELISA and antibody array kit analysis. In brief, TM cells in passage four were cultured in T75 flasks and treated with DEX or DMSO. After the treatments, TM cells were incubated with 5 ml basal medium for 48 h to collect secretome. Then, the conditioned medium was collected for a VEGFC ELISA kit (R&D System, DVEC00), TGF-β1 ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher, BMS249-4A), Profiler Human Angiogenesis Array kit (R&D System, ARY007) or Human TGF β Array kit (RayBiotech, AAH-TGFB-2-4). Mouse AH was collected immediately after killing, with approximately 4 μl of AH obtained from each eye. To meet the volume requirements for ELISA analysis, AH samples from two eyes within the same experimental group were combined and diluted fivefold to a final volume of 40 μl. VEGFC concentrations were measured using the Mouse VEGFC ELISA kit (Novus Biologicals, NBP2-78893). Each of the assays followed the protocols provided by the assay manufacturers.

siRNA-based in vitro knockdown

For siRNA transfection, TM cells were seeded in T75 flasks and incubated for 24 h. Control (scrambled) siRNA, ALK4 siRNA (Thermo Fisher, 4390824), ALK5 siRNA (Thermo Fisher, AM51331) or ALK7 siRNA (Thermo Fisher, 1299001) was mixed with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, 13778150). The siRNA-reagent complex was added to the cell culture to achieve a final siRNA concentration of 20 nM. Western blot analyses, ELISA and fluid outflow tests were performed using TM cells 24 h after the transfection.

siRNA-based knockdown in mouse anterior chamber

We performed the siRNA-based knockdown in the mouse anterior chamber based on the protocol described previously43,44. Mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane at 1 l min−1 and pupils were dilated with 2.5% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine eye drops. Then, a 250-μm acupuncture needle (Hawato) was used to puncture the cornea. Immediately after puncture, 2 μl of air was injected into the anterior chamber with a 10-μl Hamilton syringe to seal the cornea and prevent AH leakage, and 1.5 μl of PBS containing 1 μg of ALK5 siRNA (Thermo Fisher, 4457298) was injected immediately afterwards with the same syringe. Contralateral eyes received an identical injection of 1.5 μl PBS containing scramble siRNA. The ALK5 knockdown treatment will be combined with DEX treatment to investigate the impact of ALK5 in steroid-induced glaucoma.

Western blot analysis

Confluent TM cells in a six-well plate were rinsed with cold PBS three times, then lysed in cold Pierce IP Lysis Buffer (Thermo Fisher, 87788) with 1× protease inhibitor cOmplete ULTRA Tablets (Roche). Lysates were incubated on ice for 5 min before clarification at 14,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. Clarified lysates were equalized for protein content using Protein Assay Dye Reagent (Bio-Rad, 5000006). The lysate was mixed with 1× Laemmli SDS-Sample Buffer (Boston BioProducts, BP-111R) and then boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. The lysate proteins were fractionated by SDS–PAGE using 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gel (Bio-Rad, 4561094), 1× Tris/glycine/SDS running buffer (Bio-Rad, 1610732) in the Mini-PROTEAN Tetra Vertical Electrophoresis Cell (Bio-Rad, 1658004) at 150 V. The fractionated proteins in the gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using Trans-Blot Turbo RTA Mini 0.45-µm LF PVDF Transfer kit (Bio-Rad, 1704274) and the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer Starter System (Bio-Rad, 170-4155A). After protein transfer, the nitrocellulose membrane was rinsed with 1× TBST (Cell Signaling, 9997) and blocked with EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad, 12010020) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies and secondary antibodies (diluted in EveryBlot Blocking Buffer) included anti-GAPDH antibody (Cell Signaling, 5174s, 1:2,000 dilution), anti-ALK4 antibody (RayBiotech, 144-05453-50, 1:2,000 dilution), anti-ALK5 antibody (Abcam, ab51871, 1:2,000 dilution), anti-ALK7 antibody (EMD Millipore, 09-158, 1:2,000 dilution), HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Cell Signaling, 7074, 1:2,000 dilution), HRP-link anti-rat IgG antibody (Cell Signaling, 7077, 1:2,000 dilution) and HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG antibody (Cell Signaling, 7076, 1:2,000 dilution). The protein bands were visualized by a 5-min membrane exposure to SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher, PI34577A) and chemiluminescent HRP was detected using an Amersham Imager 600 (CCD-based, GE Healthcare, 29083461). Western blot images were adjusted for brightness and contrast using ImageJ41.

Transwell coculture system

A six-well Transwell system (Corning, CLS3450) was used for the coculture of TM cells with either LECs or SC cells. To seed cells on both sides of the Transwell membrane, the inserts were placed upside down and 1 ml of LEC or SC cell suspension (5 × 105 cells per ml) was carefully added to the underside of the membrane. The inserts were incubated upside down at 37 °C for 1 h to allow cell attachment. Afterward, the inserts were placed back into the wells, and TM cells were seeded on the top side of the membrane. For static culture conditions, 2.6 ml of medium was added to the bottom chamber and 1.5 ml to the top chamber, as recommended by the manufacturer. For interstitial flow conditions, 1 ml of medium was added to the bottom chamber and 3 ml to the top chamber to establish a pressure-driven flow. Based on our observations, equilibrium between the chambers was achieved after 48 h. To maintain interstitial flow conditions, the medium was refreshed every 24 h for three consecutive days.

qPCR analysis of gene expression in the Transwell coculture system

To analyze gene expression in the Transwell coculture system, TM and SC/LEC cells were detached from the membrane separately using trypsin. Total RNA was then isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and RNA purity was verified by measuring the 260:280 ratio. Reverse transcription was performed using the qScript Ultra SuperMix (Quantabio), followed by qPCR using PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) on a QuantStudio Pro 7 system (Biotechnology Resource Center, Cornell University). Primer sequences used for target genes are detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

SEM imaging in the Transwell coculture system

Samples from the Transwell coculture system were fixed with Karnovsky’s fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde) for 1 h at room temperature. Following fixation, the samples were washed three times with PBS. The membrane was carefully cut from the Transwell insert and stained with 2% osmium tetroxide (Sigma, 75632) for 1 h. After three additional washes with distilled water, the samples were dehydrated through an ethanol gradient of 30%, 50%, 70%, 90% and two changes of 100%, with each step lasting 10 min. The samples were then incubated in a 50% hexamethyldisilazane (Sigma, 440191) and 50% ethanol mixture for 10 min, followed by 100% HMDS for another 10 min and air-dried in a fume hood. The dried samples were imaged using a Zeiss LEO 1550 field emission scanning electron microscope, with the support of the Cornell Center for Materials Research.

Statistics

Independent two-sample populations were compared using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test with a normal distribution assumption. For group analyses, one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s honestly significant difference tests were used to compare the mean values. All P values were two-sided, and *P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All information regarding the sample sizes was included in the figure legends. Key experiments were independently repeated three times as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel. All data points on the graphs represent average values, and error bars depict the s.d.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All raw data (for example, numerical data and uncropped scans of blots and gels) for the main figures and extended data figures are available alongside the published article as Source Data.

Code availability

Custom codes used for the NicheNet ligand analysis and the SC cell junction analysis are available on GitHub (NicheNet ligand analysis at https://github.com/lurenhaothu/Nichenet-analysis-TM-SC-glaucoma; and junction analysis at https://github.com/lurenhaothu/Junction-Measurement).

Change history

26 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-025-00730-1

References

Weinreb, R. N., Aung, T. & Medeiros, F. A. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA 311, 1901–1911 (2014).

Torrejon, K. Y. et al. Recreating a human trabecular meshwork outflow system on microfabricated porous structures. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 110, 3205–3218 (2013).

Torrejon, K. Y. et al. TGFβ2-induced outflow alterations in a bioengineered trabecular meshwork are offset by a rho-associated kinase inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 6, 38319 (2016).

Bouchemi, M. et al. Effect of benzalkonium chloride on trabecular meshwork cells in a new in vitro 3D trabecular meshwork model for glaucoma. Toxicol. In Vitro 41, 21–29 (2017).

Osmond, M., Bernier, S. M., Pantcheva, M. B. & Krebs, M. D. Collagen and collagen-chondroitin sulfate scaffolds with uniaxially aligned pores for the biomimetic, three dimensional culture of trabecular meshwork cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 114, 915–923 (2017).

Sacca, S. C. et al. An advanced in vitro model to assess glaucoma onset. ALTEX 37, 265–274 (2020).

Waduthanthri, K. D., He, Y., Montemagno, C. & Cetinel, S. An injectable peptide hydrogel for reconstruction of the human trabecular meshwork. Acta Biomater. 100, 244–254 (2019).

Tirendi, S. et al. A 3D model of human trabecular meshwork for the research study of glaucoma. Front. Neurol. 11, 591776 (2020).

Bikuna-Izagirre, M. et al. Nanofibrous PCL-based human trabecular meshwork for aqueous humor outflow studies. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 9, 6333–6344 (2023).

Li, H. et al. A tissue-engineered human trabecular meshwork hydrogel for advanced glaucoma disease modeling. Exp. Eye Res. 205, 108472 (2021).

Dautriche, C. N. et al. A biomimetic Schlemm’s canal inner wall: a model to study outflow physiology, glaucoma pathology and high-throughput drug screening. Biomaterials 65, 86–92 (2015).

Pedrigi, R. M., Simon, D., Reed, A., Stamer, W. D. & Overby, D. R. A model of giant vacuole dynamics in human Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 92, 57–66 (2011).

Wheeler, E. L. et al. Building an organ-on-chip model of the inner wall endothelium of Schlemm’s canal. Invest. Ophth. Vis. Sci. 64, 3490 (2023).

Singh, A. et al. Glaucomatous trabecular meshwork cells induce Schlemm’s canal cell pathobiology in a biomimetic 3D ECM hydrogel co-culture model. Invest. Ophth. Vis. Sci. 64, 5077 (2023).

Keller, K. E. et al. Consensus recommendations for trabecular meshwork cell isolation, characterization and culture. Exp. Eye Res. 171, 164–173 (2018).

Aspelund, A. et al. The Schlemm’s canal is a VEGF-C/VEGFR-3-responsive lymphatic-like vessel. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 3975–3986 (2014).

Truong, T. N., Li, H., Hong, Y. K. & Chen, L. Novel characterization and live imaging of Schlemm’s canal expressing Prox-1. PLoS ONE 9, e98245 (2014).

Park, D. Y. et al. Lymphatic regulator PROX1 determines Schlemm’s canal integrity and identity. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 3960–3974 (2014).

Keller, K. E., Bradley, J. M., Vranka, J. A. & Acott, T. S. Segmental versican expression in the trabecular meshwork and involvement in outflow facility. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 5049–5057 (2011).

Thomson, B. R. et al. Cellular crosstalk regulates the aqueous humor outflow pathway and provides new targets for glaucoma therapies. Nat. Commun. 12, 6072 (2021).

Yan, X. et al. Schlemm’s canal and trabecular meshwork in eyes with primary open angle glaucoma: a comparative study using high-frequency ultrasound biomicroscopy. PLoS ONE 11, e0145824 (2016).

Lewczuk, K., Jablonska, J., Konopinska, J., Mariak, Z. & Rekas, M. Schlemm’s canal: the outflow ‘vessel’. Acta Ophthalmol. 100, e881–e890 (2022).

Wang, W., Qian, X., Song, H., Zhang, M. & Liu, Z. Fluid and structure coupling analysis of the interaction between aqueous humor and iris. Biomed. Eng. Online 15, 569–586 (2016).

Browaeys, R., Saelens, W. & Saeys, Y. NicheNet: modeling intercellular communication by linking ligands to target genes. Nat. Methods 17, 159–162 (2020).

Oikawa, K. et al. Aqueous humor TGF-β2 and its association with intraocular pressure in a naturally occurring large animal model of glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 64, 18 (2023).

Tellios, N. et al. TGF-β induces phosphorylation of phosphatase and tensin homolog: implications for fibrosis of the trabecular meshwork tissue in glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 7, 812 (2017).

Patel, G. C. et al. Dexamethasone-induced ocular hypertension in mice: effects of myocilin and route of administration. Am. J. Pathol. 187, 713–723 (2017).

Hong, S. P. et al. Distinct fibroblast subsets regulate lacteal integrity through YAP/TAZ-induced VEGF-C in intestinal villi. Nat. Commun. 11, 4102 (2020).

Jannaway, M. et al. VEGFR3 is required for button junction formation in lymphatic vessels. Cell Rep. 42, 112777 (2023).

Kim, J. et al. Impaired angiopoietin/Tie2 signaling compromises Schlemm’s canal integrity and induces glaucoma. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 3877–3896 (2017).

Hase, K. et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor-C in the trabecular meshwork of patients with neovascular glaucoma and primary open-angle glaucoma. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10132977 (2021).

Igarashi, N. et al. Aqueous autotaxin and TGF-βs are promising diagnostic biomarkers for distinguishing open-angle glaucoma subtypes. Sci. Rep. 11, 1408 (2021).

Thomson, B. R. et al. Angiopoietin-1 is required for Schlemm’s canal development in mice and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 4421–4436 (2017).

Du, J., Thomson, B. R., Onay, T. & Quaggin, S. E. Endothelial tyrosine kinase Tie1 is required for normal Schlemm’s canal development-brief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 42, 348–351 (2022).

Ujiie, N. et al. Differential roles of FOXC2 in the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal in glaucomatous pathology. Life Sci. Alliance https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa.202201721 (2023).

Yan, X. et al. VIP induces changes in the F-/G-actin ratio of Schlemm’s canal endothelium via LRRK2 transcriptional regulation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61, 45 (2020).

Abe, R. Y. et al. Can psychologic stress elevate intraocular pressure in healthy individuals? Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 3, 426–433 (2020).

Choi, D. et al. Laminar flow downregulates Notch activity to promote lymphatic sprouting. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 1225–1240 (2017).

Stamer, W. D., Roberts, B. C., Howell, D. N. & Epstein, D. L. Isolation, culture, and characterization of endothelial cells from Schlemm’s canal. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 39, 1804–1812 (1998).

Burke, A. G., Zhou, W., O’Brien, E. T., Roberts, B. C. & Stamer, W. D. Effect of hydrostatic pressure gradients and Na2EDTA on permeability of human Schlemm’s canal cell monolayers. Curr. Eye Res. 28, 391–398 (2004).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Thomson, B. R. & Quaggin, S. E. Morphological analysis of Schlemm’s canal in mice. Methods Mol. Biol. 1846, 153–160 (2018).

Cassidy, P. S. et al. siRNA targeting Schlemm’s canal endothelial tight junctions enhances outflow facility and reduces IOP in a steroid-induced OHT rodent model. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 20, 86–94 (2021).

Bogner, B. et al. Capsid mutated adeno-associated virus delivered to the anterior chamber results in efficient transduction of trabecular meshwork in mouse and rat. PLoS ONE 10, e0128759 (2015).

Acknowledgements

R.L., A.M.K. and E.L. were supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL165135; CA279560). W.D.S. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (EY022359; EY005722) and the BrightFocus Foundation. We thank K.M. Perkumas (Duke University) for the isolation and characterization of primary human SC cells. We thank Y.K. Hong (University of Southern California) for providing primary human LECs. The graphical schematic in Fig. 1a was created using BioRender (https://BioRender.com/n454oc3). This work was performed in part at the CNF, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (grant NNCI-2025233).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.L. and E.L. conceived the study and designed the experiments. R.L. performed most of the experiments and data analysis with additional help from A.M.K. R.L. and E.L. wrote the paper. R.L., W.D.S. and E.L. edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.L. and E.L. are listed as inventors on a pending patent application related to the microfluidic device presented in this study (application number: 63/780,557; status: US provisional application filed). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cardiovascular Research thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 SU-8 soft lithography fabrication procedure to prepare the M-shaped needle guide.

The M-shaped needle guide pattern was firstly fabricated upside down on the pattern wafer on top of a sacrificial layer and then transferred to the mold wafer by performing post-exposure baking (PEB) together and removing the sacrificial layer.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Characterization of TM cells.

a, Myocilin images of TM cells with or without DEX treatment (DEX concentration: 0.1 and 1 μM). b, Quantification of myocilin signal normalized by DAPI (N = 4). c, Western blot of myocilin with or without DEX treatment. Commercially obtained TM cells (ScienCell) were used in this experiment. Scale bars (a) = 100 μm. All data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (two-sided). An exact p-value is shown in the figure b.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Characterization of LEC, SC, and TM cells using immunostaining for key markers.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed to assess marker expression in lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), Schlemm’s canal (SC) cells, and trabecular meshwork (TM) cells. (Left panel) Markers shared by LECs and SC cells, including Prox1 and ITGA9, as well as the SC-specific marker nephronectin (NPNT). (Right panel) TM-related markers, including TIMP3, Myocilin, Versican, and Angpt1. Myocilin, Versican, and Angpt1 are highly expressed in the juxtacanalicular tissue (JCT) region of the TM. Fluorescence intensity for each marker, normalized by the DAPI signal, is quantified in the corresponding bar graphs (N = 4). The TM panel represents images of commercial TM cells, while the quantification includes both commercial and isolated TM cells. Scale bars = 100 μm. All data are presented as mean ± SD.

Extended Data Fig. 4 qPCR analysis of gene expression in LEC, SC, and TM cells under different culture conditions with or without interstitial flow.

a, Heatmap showing mRNA expression levels of key markers in LECs, SC cells, and TM cells under monoculture (mono) and coculture (co) conditions, with and without interstitial flow. Gene expression levels were quantified by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH. b, qPCR quantification of mRNA expression for selected markers across different conditions (N = 4 wells). Both commercial and isolated TM cells were tested to ensure reproducibility of the findings. All data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (two-sided). Exact p-values are shown in the figure b.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Ultrastructural analysis of LEC and SC cell morphology in monoculture and coculture conditions.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of (a, b) lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) and (c, d) SC cells under monoculture (mono) and coculture (co) with TM cells. Both commercial and isolated TM cells were tested to ensure reproducibility of the findings. Red arrows: giant vacuole-like structures. Scale bars = 5 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Monoculture of TM cells in the microfluidic device.

The monoculture of TM cells showed morphological changes, but the flow rate was not significantly affected by DEX treatment. a, Confocal images of monoculture of TM cells with DEX and the vehicle (DMSO). b, The flow rate was not significantly altered by DEX treatment (N = 6 chips). Commercially obtained TM cells were used in this experiment. Scale bars (a) = 100 μm. All data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons were performed using unpaired two-sided Student’s t-tests. An exact p-value is shown in the figure b.

Extended Data Fig. 7 NicheNet analyses of TM-SC interactions.

Potential ligands expressed by TM cells were prioritized by predicted ligand activity (blue box), and corresponding ligand expression is listed to its right; Permeability-related gene expressions in SC cells are listed at the top; In the middle is the correlation between the TM ligands and SC target genes.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Ocular fluid outflow on-chip device after DEX treatment with or without SB431542 treatment.

VE-Cadherin and F-actin (phalloidin) staining of the ocular fluid outflow coculture device after DEX treatment (1 μM) with or without SB431542 treatment (10 μM). Commercially obtained TM cells were used in this experiment. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Percent change in angiogenesis-related factor expression in TM cells after DEX treatment.

TM-conditioned medium was collected for Antibody Array Kit Analysis. TM cells were treated with DEX or DMSO. After the treatments, TM cells were incubated with a 5 mL basal medium for 48 h to collect secretome. Then, the conditioned medium was collected and analyzed using the Profiler Human Angiogenesis Array Kit (N = 2 wells). Commercially obtained TM cells were used in this experiment. All data are presented as mean ± SD.

Extended Data Fig. 10 siRNA-mediated knockdown of ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7 in TM cells.

a, Western blot of ALK4 and housekeeping gene GAPDH of TM cells at 48 h after ALK4 siRNA and negative control siRNA transfection. b, Western blot of ALK5 and housekeeping gene GAPDH of TM cells at 48 h after ALK5 siRNA and negative control siRNA transfection. c, Western blot of ALK7 and housekeeping gene GAPDH of TM cells at 48 h after ALK7 siRNA and negative control siRNA transfection. Commercially obtained TM cells were used in this experiment.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

Primer sequences used in qPCR reactions.

Source data

Source Data all main figures

Statistical source data of main figures.

Source Data for Extended Data Figures

Uncropped blot images for extended data figures.

Source Data for Extended Data Figures

Statistical source data of extended data figures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, R., Kolarzyk, A.M., Stamer, W.D. et al. Human ocular fluid outflow on-chip reveals trabecular meshwork-mediated Schlemm’s canal endothelial dysfunction in steroid-induced glaucoma. Nat Cardiovasc Res 4, 1066–1076 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-025-00704-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-025-00704-3

This article is cited by

-

Glaucoma discovery on a chip

Nature Cardiovascular Research (2025)