Abstract

Underwater acoustics plays a vital role in climate science, marine ecosystems, environmental monitoring, mineral exploration, and oceanography. Accurate underwater sound speed data is crucial for acoustic modeling and applications such as sonar systems. However, limited data and computational constraints hinder real-time, high-resolution mapping of three-dimensional sound speed fields. We present an integrated approach that combines remote sensing, machine learning, and underwater acoustics to estimate sound speed across vast ocean regions. By analyzing sea surface temperature and salinity from satellite observations, we use machine learning to rapidly and accurately predict 3D underwater sound speed. Incorporating spatial and temporal variables enables detailed, real-time mapping. Validation against in-situ profiles and Argo float data confirms the model’s accuracy across seasons, regions, and timeframes. This approach advances underwater sound speed prediction beyond traditional limits. Acoustic propagation modeling further demonstrates the potential of our model for applications in underwater detection, communication, and noise analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

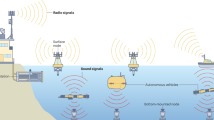

Underwater sound propagation1,2,3,4,5,6,7 is crucial for imaging and communication systems in the ocean, as electromagnetic waves do not transmit well in water. The characteristics of sound propagation are determined by the sound speed distribution, which varies spatially and temporally due to changes in temperature and salinity. Accurate sound speed distribution is essential for predicting underwater sound propagation1,8,9,10,11,12, which is critical for designing and implementing sonar systems. Real-time, accurate 3D sound fields can greatly improve the performance of underwater detection, navigation, communication systems.

Direct measurement of underwater sound speed, though possible with instruments like Acoustic Doppler Velocimeters, is often limited to specific times and locations. Alternatively, empirical sound speed formulas use in-situ measurements of salinity, temperature, and pressure (CTD data) to calculate sound speed13,14,15,16,17, but these methods require extensive ocean surveys, which are costly and time consuming. Consequently, the sound speed fields obtained from these measurements are limited.

Data assimilation techniques aim to address the challenge of limited in-situ measurements by integrating sparse observations with model data, such as those from the Modular Ocean Data Assimilation System18. However, these methods face challenges, including selecting an appropriate assimilation radius. Choosing a too-small radius can lead to inaccuracies, while a too-large one may oversimplify the data. Consequently, these techniques may not always fully capture the complexity of the ocean environment.

Acoustic tomography offers another method for estimating 3D sound speed by using sound waves of a source and receiver network to infer sound speed profiles (SSPs)19,20,21,22. However, this technique has limitations, including restricted spatial resolution and depth range (typically limited to 2–3 km), and it can be affected by interference from biological and man-made sources. Additionally, the matched-field inversion techniques used in acoustic tomography to address data scarcity by employing an array of hydrophones are less effective in large or complex ocean environments23,24,25.

High-resolution 3D ocean circulation models, like the Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean project26, provide an alternative to direct in-situ CTD measurements. While these models offer comprehensive 3D sound speed fields, they are less suitable for real-time applications due to high computational demands and potential delays.

Machine learning (ML), especially deep learning, offers significant advantages over traditional methods in addressing real-time and high-resolution challenges in underwater acoustics. These models can excel in capturing complex, nonlinear relationships among environmental parameters such as temperature, salinity, and pressure27, crucial for underwater applications. Unlike methods reliant on linear assumptions, ML models utilize large datasets and neural networks to achieve high accuracy and real-time capabilities28. They can dynamically integrate diverse data sources, like satellite imagery, enhancing adaptability to environmental changes and improving efficiency in real-time applications. Consequently, ML has superior performance over traditional algorithms in underwater acoustics, leading to improved prediction accuracy and efficiency, especially for real-time and high-resolution tasks27,29.

This study proposes to rapidly predict global ocean sound speed in near real-time using sea surface temperature (SST) and salinity data. By leveraging satellite observations and ML algorithms, the approach aims to overcome the limitations of traditional methods, providing efficient, real-time predictions for applications requiring immediate data. The model is trained using inputs such as time, depth, location (longitude, latitude), SST, and surface salinity (Fig. 1A), covering different months, days, and hours. Initially, it is trained with in-situ CTD data to compute sound speed (Fig. 1A). Once trained, the model can predict sound speed using near real-time satellite data (Fig. 1B), eliminating the need for costly and geographically limited in-situ measurements. This method enables rapid prediction of 3D sound speed fields, advancing underwater acoustics through the effective use of ML.

A Training Phase: The model learns from input parameters including month, depth, latitude, longitude, surface temperature, and surface salinity, along with sound speed data derived from Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth (CTD) measurements. These sound speed values are used to establish relationships between the inputs and the target output. B Prediction Phase: The model applies the learned relationships from the training phase to predict underwater sound speed using the same input parameters but without the need for CTD data.

In our model, the training utilizes data inputs covering different hours and times to catch the relationship of sound speed with specific times and locations. Besides this, the month has been added as an additional input to assist in catching up on the influence of the season on the sound speed. Utilization of the month as a direct input of the model should not be confused with a time-averaged model. Our model makes a prediction of sound speed values, which is real-time since the prediction is based on the updated inputs of the sea surface data at specific hours and times.

Our model’s ability to predict sound speed has been rigorously validated using datasets spanning the training time window, beyond it, and across diverse seasons and locations, demonstrating accurate, real-time, high-resolution 3D sound speed mapping. While specific regions showed lower prediction accuracy, these were addressed with region-specific models. Further analysis indicated the model’s suitability for underwater acoustic applications, particularly involving low- to mid-frequency sources such as detection, communication, and noise propagation. Additionally, this study showcased sound speed prediction using satellite observations, highlighting the model’s versatility and its potential for integration into various underwater contexts, with detailed results supporting these findings.

Results

For a comprehensive understanding of our methodology, including the data sources, ML models, evaluation metrics, and detailed model comparisons, refer to the Materials and Methods section in the supplementary materials. We employed two advanced models—Deep Neural Network (DNN) and K-nearest Neighbor (KNN)—to predict underwater sound speed based on surface data. Standard evaluation metrics, specifically Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and R-squared (R2) scores, were used to assess the performance of these models. Our analysis revealed that the KNN model outperformed the DNN model, leading us to select KNN for subsequent analyzes.

Table 1 provides an overview of the datasets used for both training and prediction. Our analysis utilized three primary datasets: (1) the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE) dataset, which includes ~29 million data instances collected from 1992 to 1998 (see Fig. 3A)30; (2) WOA dataset, which offers monthly averaged data from 2004 to 2023 with a 1° × 1° horizontal resolution down to 2000 m depth31; and (3) the Physical Oceanography Distributed Active Archive Center (PODAAC), which provides daily updates on satellite-observed SST32 and salinity33.

In addition to predictions based on satellite data (Table 1), other predictions incorporated temperature and salinity at zero depth from the CTD data within the datasets as surface inputs to train and forecast sound speed fields. These predictions were then compared with sound speed calculated from CTD data at various depths within the datasets (See the “Methods” section for details about the calculation).

Insights into model performance

We start from interpreting the physics behind the effectiveness of our model in predicting underwater sound speed based on sea surface data. To do this, we analyzed the correlation between surface sound speed and sound speed at various depths using CTD data from the 2015 WOA31. This analysis evaluated correlation values from the surface to depths of up to 2000 m for both March and September (Fig. 2), representing summer and winter seasons, respectively.

The high correlation values observed in the upper 500 m (Fig. 2) indicate a strong influence of surface parameters on sound speed in this region. This finding predicts our model’s ability to accurately capture the vertical SSP based on surface conditions, which is crucial given that temperature and salinity, both of which vary at the surface, predominantly influence sound speed in the upper ocean. The results demonstrate the model’s proficiency in leveraging surface data for accurate sound speed predictions in these upper layers.

As depth increases, correlation values decrease (Fig. 2), suggesting that surface conditions have a diminished influence on sound speed. In deeper regions, pressure becomes the dominant factor affecting sound speed. Here, the model relies on historical data patterns to predict sound speed, effectively managing the complexities associated with deeper ocean profiles. By integrating historical data, the model should maintain robust predictive accuracy even in deeper regions where surface parameters are less relevant.

With these results, our model should effectively use surface parameters for sound speed predictions in the upper ocean while adapting to the stable pressure influences in deeper waters, ensuring comprehensive prediction capabilities across varying ocean depths.

Prediction within the training time window

We trained our model using 80% of the WOCE dataset30 and ensure robust performance evaluation by employing a 5-fold cross-validation (see Supplementary). Figure 3A shows a map of the CTD data collection locations for the WOCE dataset. We then predicted sound speed values for 5 million data instances from the remaining 20% of the data reserved for testing. Figure 3B shows an illustrative example of one predicted SSP, which closely aligns with the CTD-calculated values, demonstrating the model’s potential applicability.

A Map showing the locations where CTD data were collected for the WOCE dataset. B Sound speed profile in the North Pacific at 150°W longitude and 30°N latitude, comparing calculated (solid line) and predicted (dashed line) sound speed values. C Error distribution heatmap, where the color intensity indicates the number of predictions falling within specific error ranges. D Variation of Mean Absolute Error (MAE) with depth, illustrating the model’s accuracy across different depths.

To further evaluate the model’s efficacy, we conducted a detailed error analysis by comparing the predicted sound speed values with those calculated using CTD data. We categorized prediction errors into bins across different depth ranges. The symmetry in the heatmap (Fig. 3C) suggests an equal likelihood of positive and negative errors, with a sharp peak indicating consistent model performance and minimal significant outliers. The error distribution heatmap (Fig. 3C) reveals the greatest dispersion near the surface (0–1000 m), where the ocean exhibits significant variability, with error magnitudes ranging from −12 to 12 m/s, and over 99% of errors within ±0.5 m/s. The mean absolute error (Fig. 3D) shows a depth-dependent variation, peaking at 0.16 m/s around 100 m and then stabilizing at greater depths, consistent with the heatmap analysis.

Overall, the results show a trend of improving prediction accuracy with depth. The model faces challenges in the upper ocean, where wind and ocean interactions introduce greater variability, but it performs better in the deep ocean, where pressure predominantly influences sound speed. However, those large-magnitude errors predominantly found at shallow depths are infrequent, highlighting the model’s overall effectiveness in sound speed prediction, at least within the training time window.

Prediction beyond the training time window

Our model was trained using in-situ CTD data from the WOCE dataset, collected between 1990 and 199830. A key question is whether this model, trained on historical data, can accurately predict SSPs beyond this period. To investigate this, we applied our model to predict sound speed using the WOA dataset31, which provides monthly averaged data on temperature and salinity for specific depths, latitudes, and longitudes. We compared these predictions with SSPs derived from CTD data within the WOA dataset in 2015.

We examined SSPs at various latitudes along 150° West longitude in January to assess the model’s ability to replicate latitude-dependent underwater sound speed variations. The model’s predictions (dashed lines) closely align with SSPs calculated from CTD data in the WOA (solid lines) (Fig. 4A). The model effectively captured key relationships, such as higher sound speed values at lower latitudes corresponding to warmer surface temperatures and lower sound speed values at higher latitudes associated with cooler temperatures. It also accurately predicted minimal variations in sound speed across different latitudes in deep ocean regions. These results demonstrate the model’s capability to reproduce the dependence of sound speed on latitude, validating its predictive accuracy and its ability to generalize beyond the training data.

A Variations in sound speed profiles at 150°W longitude across four different latitudes in January, with colors denoting: blue for 15°S, red for 15°N, black for 55°N, and magenta for 60°S. B Seasonal variations in the Atlantic Ocean at 39°W and 54°N, with blue representing March and red representing September. C Seasonal variations in the Indian Ocean at 83°E and 40°S, with blue representing March and red representing September. D A comparison of sound speed fields along a meridional cross-section at 150°W longitude in January.

We analyzed predictions for March and September 2015, representing winter and summer in the northern hemisphere (and vice versa in the southern hemisphere), to evaluate the model’s ability to capture seasonal variations in sound speed. We focused on the North Atlantic, a region known for significant seasonal fluctuations. Comparison of calculated profiles using monthly averaged CTD data from the WOA dataset with our model’s predictions (Fig. 4B) showed strong agreement. The model accurately reflected expected seasonal patterns, demonstrating lower surface sound speeds in March (winter) and higher values in September (summer), consistent with typical temperature variations. The predictions also maintained consistency in deeper ocean regions across seasons, underscoring the model’s reliability in capturing surface variability and deep-water stability.

Expanding our analysis to the southern hemisphere, we tested the model’s predictions for the Indian Ocean, focusing on inverse seasonal trends compared to the northern hemisphere. The model predictions successfully mirrored established seasonal trends of sound speed in the southern hemisphere (Fig. 4C). Results accurately reflected higher sound speed values associated with warmer surface temperatures in March (summer) and lower values due to colder temperatures in September (winter), demonstrating the model’s consistency across different global regions.

These comprehensive analyzes (Fig. 4A–C) validate our model’s predictive capabilities across different latitudes and seasons beyond the training period. Figure 4D further compares our model’s forecast with the CTD-derived sound speed field along a meridional cross-section at 150°W longitude for January 2015. The results underscore our model’s precision and reliability in predicting global sound speed distributions, highlighting its significant potential for practical applications in ocean acoustics.

The model’s predictive accuracy is bolstered by its ability to interpret the relationships between sound speed and key environmental parameters, such as temperature, salinity, and pressure. The variation of these environmental parameters over the years or decades within the same seasons is not as profound as the seasonal variation within a year. The seasonal variations are pronounced enough to significantly change sound speed. By effectively capturing these seasonal fluctuations, the model adeptly manages smaller interannual changes, enabling it to make accurate predictions even beyond its initial training period. In other words, given the model’s ability to capture the strong seasonal variations in sound speed, it appears not surprising that the ML model demonstrates proficiency in predicting ocean sound speed beyond its training period. By integrating robust historical datasets like WOCE, the model incorporates these parameters into its framework, allowing it to leverage long-term temperature trends for informed predictions. Its adaptability is crucial, as it identifies recurring patterns and integrates both seasonal and long-term climate trends for effective generalization. This integration ensures the model’s relevance and accuracy, providing reliable predictions even in scenarios beyond its primary training scope.

Global predictions

We evaluated our model’s global performance using the WOA31 datasets for March and September 2015, representing winter and summer in the northern hemisphere. This analysis compared model-predicted sound speeds with those derived from CTD data across ~19 million data points at a 1° × 1° resolution, as defined by the WOA dataset. This global assessment provides a broad view of the model’s accuracy across diverse ocean conditions and locations.

Depth-based heatmaps of prediction errors for March and September 2015 (Fig. 5A, B) reveal that the model maintains accuracy throughout the water column, with more pronounced errors near the surface (0–500 m) due to complex dynamics in the upper ocean. Despite some increased error dispersion at shallower depths, there is no significant rise in error with depth, reflecting reliable performance even in deeper waters. The symmetric distribution and peak near zero indicate consistent model performance with few significant outliers. These results for predictions beyond the training periods align with those in Fig. 3C for predictions within the training period, further validating the model’s performance across different datasets and temporal scales.

Top panels: A, B show depth-based heatmaps of prediction errors for March and September 2015, with the color spectrum from blue to red indicating error frequency, and gray areas representing fewer than 50 predictions. Bottom Panel: C presents the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) as a function of depth for March (blue) and September (red) 2015.

In the heatmaps (Fig. 5A, B), over 95% of errors fall within ±20 m/s, with error magnitudes ranging from −60 to 60 m/s. The MAE distribution across depths (Fig. 5C) peaks at around 8 m/s between 0 and 200 m and decreases with depth, consistent with the depth-based heatmaps. Compared to predictions within the training period (Fig. 3C), these global predictions beyond the training period show a larger error range due to expanded data coverage and temporal extrapolation. Despite these challenges, the model’s performance in capturing seasonal variations over all depths validates its robustness across diverse oceanographic conditions throughout the year.

To evaluate the model’s global performance, we calculated the MAE for each location and averaged it across all depths. Contour plots for March (Fig. 6A) and September (Fig. 6B) show MAE distribution across latitudes and longitudes, with most of the world’s oceans exhibiting low errors within 8 m/s (as indicated by the blue shading). The plots also highlight regions with notably higher errors (marked by red squares), reflecting the model’s challenges in dynamic regions or areas with limited data. These are regions:

-

(I)

The Arctic region near Greenland and Iceland (area 1 in Fig. 6) shows errors as high as 38 m/s. This large error is due to variable temperature and salinity profiles resulting from seasonal sea ice dynamics and limited training data34. Climate change impacts, such as accelerated ice melt and shifting ocean currents–factors not fully captured by historical data35—further exacerbate prediction errors. These complexities contribute to an unpredictable environment, challenging the model’s accuracy in this region.

-

(II)

The North Atlantic near the United States and Canada (area 2 in Fig. 6) exhibits significant errors influenced by the Gulf Stream’s warm water transport and strong currents36. Coastal regions generally show higher errors due to rapidly changing environments.

-

(III)

The Mediterranean Sea (area 3 in Fig. 6) shows increased errors due to its complex water masses, seasonal variations, and high evaporation rates37.

-

(IV)

A small area in the South Pacific Ocean (area 4 in Fig. 6) displays high errors, potentially due to localized oceanographic phenomena and insufficient training data.

-

(V)

The Japan Sea (area 5 in Fig. 6) shows errors up to 51 m/s, influenced by the Kuroshio current and complex oceanographic features38.

These factors, including encountering unfamiliar oceanic conditions and long-term changes, highlight the model’s limitations and the need for ongoing refinement and potential region-specific adjustments.

Regional model

Our examination of the global model’s performance across various marine environments identified certain limitations in specific oceanic regions. For example, in the Arctic region near Greenland and Iceland (area 1 in Fig. 6), insufficient training data (Fig. 7A) likely contributed to a significant increase in error, with a maximum MAE of 35 m/s (Fig. 7B).

To address the challenges posed by data scarcity in specific areas, we developed a regional model. This model, trained with inputs similar to the global model, uses CTD data to calculate sound speed as its target while incorporating surface data. For training, we utilized the 2004 World Ocean Atlas (WOA) dataset, focusing exclusively on the Arctic region with a horizontal resolution of 1° × 1°, and comprising ~380,000 data instances (Fig. 7C).

The regional model significantly improved performance, reducing the maximum prediction error from 35 m/s to 13 m/s in the Arctic region (Fig. 7D). This result highlights the advantages of using regional models with more focused datasets to tackle specific environmental challenges, particularly in regions where global models may fail to capture intricate local oceanographic details.

However, while the reduction from 35 m/s to 13 m/s is notable, the remaining maximum error of 13 m/s is still somewhat higher than the average MAE of 5 m/s achieved with the global model. This residual error underscores the ongoing challenge posed by the Arctic’s complex ocean dynamics for achieving precise sound speed predictions.

Influence of prediction error on underwater sound propagation

To evaluate the impact of sound speed prediction errors on underwater sound propagation, we used the Bellhop ray tracing module in Python, a well-established tool for ocean acoustic modeling39. Our analysis focused on transmission loss (TL), which measures the reduction in acoustic signal strength over distance and provides insights into sound propagation in the ocean11. We examined TL at 200 Hz and 15 kHz to represent low- and middle-frequency underwater sound waves. Low-frequency waves (200 Hz) generally travel longer distances with less attenuation, while middle-frequency waves (15 kHz) experience greater attenuation and, consequently, more TL. Therefore, we used a 50 km range for the low-frequency scenario, while for the mid-frequency scenario, a 20 km range was selected.

We selected a location in the South Atlantic (6°E longitude, 11°S latitude) where the prediction error was close to the depth-averaged MAE (Fig. 5E), providing a representative scenario. Our analysis involved a sound source at 840 m depth (where sound speed is minimal) in March 2015. We used the SSP predicted by our ML model (Fig. 8A) to simulate TL for both a 200 Hz source (Fig. 8B) and a 15 kHz source (Fig. 8C). For comparison, we also used the SSP derived from CTD data in the WOA (Fig. 8D) for TL simulations (low-frequency in Fig. 8E, mid-frequency in Fig. 8F). The TL results illustrate how acoustic energy is distributed over distance and depth, revealing areas of high and low TL due to interference patterns.

Top Row: A Predicted sound speed profile Cmodel with input values (red dots) and interpolated profile (blue line). B Transmission loss for a 200 Hz source based on the predicted profile. C Transmission loss for a 15 kHz source based on the predicted profile. Middle Row: D Sound speed profile Cdata from CTD data. E Transmission loss for a 200 Hz source using the CTD profile. F Transmission loss for a 15 kHz source using the CTD profile. Bottom Row: G Differences in sound speed between predicted and CTD profiles (Δc = cmodel − cdata). H Transmission loss differences for the 200 Hz source. I Transmission loss differences for the 15 kHz source.

Discrepancies between predicted and actual SSPs (Fig. 8G), ranging from −2 to 10 m/s, can affect propagation paths and TL patterns. Differences in TL simulations based on predicted versus actual SSPs for both low-frequency (Fig. 8H) and mid-frequency (Fig. 8I) show that TL differences generally fall within ±3 dB (light green color). Only a few areas exhibit larger TL variations, indicated by reddish or blue colors. These larger differences are typically observed near ray caustics or regions with path interference, where TL is highly sensitive to input parameters.

The model’s consistent performance across frequencies, with TL discrepancies generally within ±3 dB, suggests its effectiveness for various acoustic applications, including naval assessments, oceanographic surveys, and studies of anthropogenic noise impacts, particularly for low to mid-frequency sources. However, it may not be suitable for applications requiring TL accuracy beyond ±3 dB, high-frequency acoustics (above 1000 kHz) without further validation, or complex environments with rapid oceanographic changes or intricate bathymetry. For such critical applications, it is advisable to use this model in conjunction with advanced propagation tools or in-situ measurements to improve accuracy.

Satellite data-based predictions

Our ML approach leverages near real-time SST and sea surface salinity (SSS) data from remote sensing satellites to predict underwater sound speed. This methodology overcomes the limitations of traditional in-situ measurements, which are often expensive and geographically constrained, by providing high-resolution, three-dimensional sound speed predictions for any location and time. Such real-time capabilities are not available with traditional in-situ data, which is typically limited to specific years.

To illustrate the high-resolution mapping capabilities of our model, we utilized sea surface parameters from the PODAAC, which provides daily updates on satellite-observed surface conditions. For example, we used SST32 (Fig. 9A) and SSS33 (Fig. 9B) data for November 8, 2023, as inputs to our model to predict sound speed variations at a depth of 50 m globally (Fig. 9C). The results show higher sound speeds near the equator and lower sound speeds in polar regions as expected, demonstrating the correctness of the model.

Unlike traditional 3D ocean circulation models, which face challenges with real-time data delivery due to high computational demands, our ML approach offers rapid predictions for specific coordinates and depths. While 3D ocean circulation models provide valuable insights, our ML-based model has significant potential to enhance sound speed predictions, especially for applications requiring timely data.

Discussion

Our research introduces a machine-learning model for predicting underwater SSPs using surface data and spatial information. Trained and validated on the WOCE and WOA datasets, the KNN model outperformed the DNN model in capturing local sound speed variations and handling nonlinearities, with over 99% of prediction errors within ±0.5 m/s during the training period. The strong correlation between surface and depth-specific sound speeds validates our approach, particularly in the upper 500 m, where temperature and salinity are significant. As depth increases, the model’s reliance on historical data becomes crucial, demonstrating its adaptability from surface-influenced to pressure-dominated regions.

The model demonstrates robust generalization across different seasons and periods, extending beyond the training time window. The ML model’s predictive strength in ocean sound speed is largely attributed to its ability to capture the strong dependency of sound speed on temperature, particularly its sensitivity to seasonal variations, which are more significant than interannual changes. The model effectively extrapolates beyond its training data by integrating relationships among key environmental factors such as salinity and pressure and leveraging robust historical datasets like WOCE. Its adaptability in recognizing patterns allows it to adjust to climatic fluctuations, ensuring reliable and accurate predictions of underwater SSPs across various temporal and spatial contexts, even beyond its initial training period, thereby maintaining its relevance in ocean acoustics.

Our model offers computational efficiency and rapid predictions compared to traditional 3D ocean circulation models. The model’s rapid, real-time prediction capability stems from its exceptional adaptability to various temporal granularities of input data. It is designed to provide flexible sound speed forecasts across different temporal scales, such as monthly and daily averages, ensuring precise and reliable predictions. This adaptability enables the model to cater to a wide range of oceanographic applications by tailoring its predictions to the data’s temporal characteristics. As a result, the model efficiently generates consistent and robust 3D sound speed estimates, supporting diverse oceanographic initiatives and delivering accurate sound speed projections under various environmental conditions.

Since the model adapts seamlessly to the granularity of the input data, it aligns its outputs accordingly. For instance, when provided with monthly average data, the model forecasts monthly average sound speeds (Fig. 4). It accurately predicts daily sound speeds when updated with daily satellite data (Fig. 9C). Given adequate input data, similar predictions are possible for even finer temporal granularity, such as hourly estimates. This flexibility underscores the model’s robust performance across diverse temporal and spatial resolutions, making it a valuable asset for a wide variety of oceanographic applications, ensuring precise and reliable sound speed estimates under varying data conditions.

The model excels at identifying anomalies and can be retrained with new datasets to maintain accuracy across diverse marine environments. Performance varied with depth, improving in deeper waters and with mean absolute error peaking at around 8 m/s in the upper ocean, where wind mixing, wave dynamics, and surface currents are prevalent. Regional and seasonal differences, especially in data-scarce areas like the Arctic, highlight the need for region-specific adjustments and more frequent data collection. Our Arctic regional model reduced the maximum prediction error from 35 m/s to 13 m/s, indicating that similar approaches could enhance sound speed mapping in other complex marine regions.

The relationship between global and regional models is critical for improving underwater sound speed prediction across varying marine environments. Global models serve as a robust foundational dataset that informs regional models, facilitating the identification of local anomalies and enhancing prediction accuracy through localized training. Although both models use the same input parameters, regional models benefit from high-resolution local data, adapting effectively to specific areas’ complex dynamics for greater predictive accuracy, whereas global models, being generalized, may miss localized phenomena. Integrating both modeling approaches and utilizing region-specific datasets creates a comprehensive framework that employs global data while customizing predictions to the nuanced regional conditions. This approach leads to more accurate and reliable sound speed estimations in diverse oceanic locations and addresses unique environmental challenges in targeted marine regions.

Integrating our model with acoustic propagation simulations highlights its practical value. Comparison of TL patterns with CTD data shows reliable projections, with TL differences generally within ±3 dB. This result suggests the model is suitable for a series of underwater applications involving low to mid-frequency sources, such as underwater detection, communication, and noise propagation. Although there are variations near ray caustics, the model remains accurate for underwater acoustic assessments.

Despite its strengths, the model’s error margin, while small compared to the average seawater sound speed of about 1500 m/s, can be significant to some applications that require high accuracy, for example, accurate underwater positioning systems. Underwater positioning systems use acoustic signals to track the location of underwater objects. In this scenario, acoustic travel time is extracted from acoustic signals and combined with sound speed to estimate the distance to the object. Therefore, a better sound speed model can significantly improve the position accuracy. Considering an object located about 15 km away (yielding a one-way acoustic travel time of 10 s), a 10 m/s sound speed error from our model will lead to a distance estimation error of 100 m, which is about only 1% of the total distance of 15 km. This estimation error is good for most applications unless higher accuracy is required. The model may not be suitable for high-frequency acoustics or rapidly changing oceanographic environments. For these applications, combining this model with advanced propagation tools or in-situ measurements is recommended for enhanced accuracy.

Future research should focus on: (i) developing adaptive modeling techniques for regional and dynamic conditions, (ii) integrating real-time data to improve predictions, (iii) combining global and local prediction strategies, (iv) integrating physical oceanographic principles with ML, and (v) including additional parameters such as current velocities and seabed characteristics to improve accuracy.

Conclusion

In summary, while our model represents a significant advancement in sound speed prediction, it highlights the complexities of oceanographic modeling. Continued interdisciplinary collaboration between oceanographers, data scientists, and acoustic experts is essential for refining predictive tools and understanding global ocean dynamics and underwater acoustics. Comparative analysis with authoritative data sources, such as NOAA or Navy forecasts, will be crucial for bridging gaps in real-time acoustic modeling and aligning our model with practical marine applications.

Methods

Data sets

The primary dataset for model training and testing is sourced from the WOCE30, which was collected from 1990 to 1998 as part of the World Climate Research Program. This dataset includes in-situ measurements of key climate-related variables such as temperature, salinity, and depth, gathered using various instruments on a fleet of research vessels. These vessels covered the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Southern Oceans, stopping approximately every 60 km for data collection. Our model utilizes the CTD data along with corresponding location and time information from 294 cruises.

For model validation beyond the training dataset, we use the WOA31 dataset, maintained by the National Oceanographic Data Center (NODC). The WOA includes extensive oceanographic data from ARGO floats, covering a spatial resolution of 1° by 1° and including parameters such as temperature, salinity, nutrients, and oxygen content. It spans the upper 2000 m of the ocean but excludes some high-latitude regions. By integrating historical data from various sources, the WOA provides a dynamic overview of the ocean’s state, serving as a crucial benchmark for assessing our model’s accuracy and reliability.

Preprocessing of data sets

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of our machine-learning model for predicting oceanic SSPs, we undertook comprehensive preprocessing of the WOCE raw data, which initially comprised ~29 million records. The first significant step in preprocessing involved addressing missing values, as they can severely impact the performance of ML algorithms. Rows with null values were systematically identified and removed. This approach was chosen over imputation (which estimates missing values based on available data) to maintain dataset integrity and avoid introducing biases.

In parallel, we employed rigorous methods to identify and remove outliers to enhance the overall quality of the dataset. A 95% confidence interval was established based on the distribution of the dataset, which served as a benchmark for detecting outliers. This was complemented by the use of box plots for visual validation. Specifically, data points exceeding 1.5 times the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles were classified as outliers and subsequently removed. This dual methodology ensured the systematic removal of erroneous records while preserving legitimate variations within the data, resulting in around 2 million records being discarded. Consequently, the refined dataset consists of ~27 million records.

Following the cleanup process, each record in the refined dataset included critical oceanographic parameters, such as location (longitude and latitude), time (month), depth, salinity, temperature, SSS, and SST. We performed the necessary conversions and computations to enhance data utility: depth values were converted to pressure using the function gsw.pfromz(depth, latitude), and sound speed was calculated utilizing the equation provided by the gsw.soundspeed(SA, CT, p) function from the Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater 2010 (TEOS-10)40.Cyclic parameter conversions were applied to account for the cyclical nature of variables such as month and longitude. For compatibility with ML algorithms, the dataset was normalized using the standard scaler functionality from the scikit-learn Python package, which standardizes feature ranges and improves model performance and convergence.

For model training, we allocated 80% of the refined dataset while the remaining 20% was reserved for testing the model’s generalization capabilities. We employed a 5-fold cross-validation technique to assess the model’s performance across various data subsets. This approach provides a robust estimate of the model’s efficacy and aids in mitigating overfitting, ultimately ensuring that the model remains applicable for real-world scenarios.

Models and training

Our study employs two advanced models to handle high-dimensional, nonlinear data for predicting sound speed: the DNN and the KNN. These models are selected to leverage their strengths in interpreting nonlinear associations within the complex marine environment.

The DNN, characterized by multiple layers, is adept at discerning complex, non-linear associations among varied inputs and outputs. Training of the DNN network utilized the backpropagation algorithm for effective learning and adaptation to data patterns. Hyperparameter optimization, essential for maximizing performance, was performed using the Keras tuner package’s random search function to evaluate various combinations of hyperparameters (number of layers, nodes per layer, learning rate). The objective was to minimize the MAE, chosen for its efficacy in predicting marine environmental behavior. This fine-tuning process improved the DNN model’s ability to capture complex dynamics and accurately represent nonlinear relationships within the data. The architecture of the DNNs model is showcased in Supplementary Fig. 1.

The KNN model, chosen for its simplicity and interpretability, complements the DNN approach. This supervised ML algorithm leverages the entire training dataset without requiring learning weights or predefined functions. It assumes that similar instances are close to each other and predicts based on the majority class among k nearest neighbors. We optimized the KNN model’s performance by experimenting with different ’k’ values to determine the optimal number of nearest neighbors for predictions. RMSE was used as the evaluation metric during training to assess prediction error magnitude. Additionally, the Euclidean distance function was used to calculate instance distances, enhancing the model’s ability to capture underlying patterns in underwater sound speed data.

The model training process and the selection of the best model for further investigation are detailed in the supplementary material. Learning curves for the DNN model training and the K-NN model training are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. Additionally, scatter plots in Supplementary Fig. 3 and statistical metrics in Supplementary Table 1 illustrate the strengths and weaknesses of each model.

Data availability

The oceanographic data that support the findings of this study are publicly available from the following sources: Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth (CTD) measurements from the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) repository, including the WOCE Global Data Resource (accession number NODC-WOCE-GDR, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/archive/accession/NODC-WOCE-GDR); CTD data from the WOA (accession number NCEI-WOA18, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/archive/accession/NCEI-WOA18); and SST and salinity data from the PODAAC with 10.5067/GHOST-4RM02 and https://doi.org/10.5067/SMP10-4U7CS. These datasets are freely accessible and can be retrieved by the public.

Code availability

The Python codes used for this work are available at https://zenodo.org/records/1492650641.

References

Consortium, T. A. Ocean climate change: comparison of acoustic tomography, satellite altimetry, and modeling. Science 281, 1327–1332 (1998).

Muir, T. G. & Bradley, D. L. Underwater acoustics: a brief historical overview through world war ii. Acoust. Today 12, 40–48 (2016).

Kuperman, W. A. & Lynch, J. F. Shallow-water acoustics. Phys. Today 57, 55–61 (2004).

Vigness-Raposa, K. J., Scowcroft, G., Morin, H. & Knowlton, C. Underwater acoustics for everyone. Acoust. Today 10, 30–41 (2014).

Lurton, X. An Introduction to Underwater Acoustics: Principles and Applications (Springer-Verlag, 2002).

Brekhovskikh, L. M. & Lysanov, Y. P. Fundamentals of ocean acoustics. in Modern Acoustics and Signal Processing 3rd edn (Springer, 2006).

Medwin, H. Sounds in the Sea: From Ocean Acoustics to Acoustical Oceanography (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Ballard, M. S., Frisk, G. V. & Becker, K. M. Estimates of the temporal and spatial variability of ocean sound speed on the new jersey shelf. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 135, 3316–3326 (2014).

Lin, Y.-T., Porter, M. B., Sturm, F., Isakson, M. J. & Chiu, C.-S. Introduction to the special issue on three-dimensional underwater acoustics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 146, 1855–1857 (2019).

Duda, T. F. et al. Multiscale multiphysics data-informed modeling for three-dimensional ocean acoustic simulation and prediction. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 146, 1996–2015 (2019).

Colosi, J. A. & Rudnick, D. L. Observations of upper ocean sound-speed structures in the north pacific and their effects on long-range acoustic propagation at low and mid-frequencies. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 148, 2040–2060 (2020).

Touret, R. X., Liu, G., McKinley, M., Bracco, A. & Sabra, K. G. On the role of vertical resolution for resolving mesoscale eddy dynamics and the prediction of ocean sound speed variability. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 153, A5–A11 (2023).

Chen, C. & Millero, F. J. Speed of sound in seawater at high pressures. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 62, 1129–1135 (1977).

Leroy, C. C., Robinson, S. P. & Goldsmith, M. J. A new equation for the accurate calculation of sound speed in all oceans. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 124, 2774–2782 (2008).

Lovett, J. R. Merged seawater sound-speed equations. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 63, 1713–1718 (1978).

Wilson, W. D. Equation for the speed of sound in sea water. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 32, 1357 (1960).

Wong, G. S. K. & Zhu, S. Speed of sound in seawater as a function of salinity, temperature, and pressure. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 97, 1732–1736 (1995).

Fox, D. N. et al. The modular ocean data assimilation system. Oceanography 15, 22–28 (2002).

Munk, W. & Wunsch, C. Ocean acoustic tomography: a scheme for large scale monitoring. Deep Sea Res. Part A. Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 26, 123–161 (1979).

Munk, W. Ocean Acoustic Tomography (Springer, 2006).

Elisseeff, P., Schmidt, H. & Xu, W. Ocean acoustic tomography as a data assimilation problem. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 27, 275–282 (2002).

Jin, J. et al. Machine learning approaches for ray-based ocean acoustic tomography. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 153, 1698–1709 (2023).

Gerstoft, P. & Gingras, D. F. Parameter estimation using multifrequency range-dependent acoustic data in shallow water. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 99, 2839–2850 (1996).

Jiang, Y.-M. & Chapman, N. R. The impact of ocean sound speed variability on the uncertainty of geoacoustic parameter estimates. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 2881–2895 (2009).

Huang, C.-F., Gerstoft, P. & Hodgkiss, W. S. Effect of ocean sound speed uncertainty on matched-field geoacoustic inversion. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123, EL162–EL168 (2008).

ECCO Consortium, Fukumori, I. et al. ECCO Central Estimate (Version 4 Release 4). Retrieved from https://ecco.jpl.nasa.gov/drive/files/Version4/Release4 (2021).

Niu, H., Li, X. & Zhang, Yea Advances and applications of machine learning in underwater acoustics. Intell. Mar. Technol. Syst. 1, 8 (2023).

Kelleher, J. D. & Tierney, B. Data science. in Essential Knowledge (MIT Press, 2018).

Bishop, C. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning 1st edn (Springer, 2007).

WOCE Data Products Committee. NODC standard product: world ocean circulation experiment (WOCE) global data resource (GDR), versions 1–3, on CD-ROM and DVD. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/archive/accession/NODC-WOCE-GDR (2002).

Boyer, T. P. et al. World ocean atlas 2018. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/archive/accession/NCEI-WOA18 (2018).

NASA/JPL. GHRSST level 4 OSTIA global historical reprocessed foundation sea surface temperature analysis produced by the UK meteorological office. https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/dataset/OSTIA-UKMO-L4-GLOB-REP-v2.0 (2023).

IPRC/SOEST, U. O. H. Multi-mission optimally interpolated sea surface salinity 7-day global dataset v1 http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/datadoc/oisss.php (2021).

Oldenburg, E. et al. Sea-ice melt determines seasonal phytoplankton dynamics and delimits the habitat of temperate atlantic taxa as the arctic ocean atlantifies. ISME Commun. 4, ycae027 (2024).

Stroeve, J. C. et al. The arctic’s rapidly shrinking sea ice cover: a research synthesis. Clim. Change 110, 1005–1027 (2011).

Bower, A. S. & von Appen, W.-J. Interannual variability in the pathways of the north atlantic current over the mid-atlantic ridge and the impact of topography. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 38, 104–120 (2008).

Colin, C. et al. Changes in the intermediate water masses of the mediterranean sea during the last climatic cycle-new constraints from neodymium isotopes in foraminifera. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA004153 (2021).

Fang, X. et al. Behavior of water mass beneath the tsushima warm current in the japan sea. Water 12, 2184 (2020).

Porter, M. B. & Bucker, H. P. Gaussian beam tracing for computing ocean acoustic fields. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 82, 1349–1359 (1987).

Sarraf, P. B. & Menu, A. Thermodynamic equation of seawater 2010 http://www.teos-10.org/ (TEOS-10, 2010).

Madiligama, M. Code for model training for manuscript (leveraging satellite observations and machine learning for real-time underwater sound speed estimation) (2025).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge Dr. Karim Sabra for his invaluable discussions and insights.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Feiyun Wu and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Zhuo Zhang] and [Miranda Vinay and Rosamund Daw]. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Madiligama, M., Zou, Z. & Zhang, L. Leveraging satellite observations and machine learning for underwater sound speed estimation. Commun Eng 4, 126 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00459-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00459-6

This article is cited by

-

Leveraging satellite observations and machine learning for underwater sound speed estimation

Communications Engineering (2025)