Abstract

Projections of climate change impacts on crop production vary across crops, study areas, and shared socioeconomic pathways indicating a need for higher specificity and regional relevance. Here, we confirmed in silico, future climate warming generally increased soybean yield and yield stability, decreasing the drought stress by mid-century, particularly in the western areas of the Northeast China. The declining yield coefficient-of-variation was mostly caused by both increases in mean yield and decreases in yield standard deviation. The random forest algorithm identified the reduction in the growing degree days during vegetative growth period was the main factor driving higher soybean yields. The increases in rainfall during reproductive growth period and decreases in its coefficient-of-variation would help reduce soybean drought stress and yield coefficient-of-variation in the future. This study highlights regional specific positive impacts of climate change, useful to inform policy and stakeholders to increase preparedness along value chains under expected future climates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The expected increase in global population, living standards, and associated climate change are intertwined with the food and energy security outcomes of hundreds of millions of people1,2. Climate change strongly affects crop production driven by warming temperatures, variable precipitation patterns, increases of frequency and intensity of extreme climate events, and elevated CO2 concentrations3,4,5. Understanding how climate change impacts future crop production holds great significance in meeting increasing food and energy demands1,6.

Process-based crop models are able to reproduce complex interactions between environmental factors, management practices, and crop growth and yield, and can help inform expected changes in yield and yield stability7. Coupled with projected climate data from general circulation models (GCMs), crop models have been used to capture the potential impacts of future climate change on crop production3,5. Results predominantly show that climate warming will reduce average crop yields at the global scale, however, some increases are expected for the higher latitudes3,5,6. Yield projections under climate change are highly heterogeneous across study areas and crops, though influenced by the combination of crop model, GCM, and simulated period8,9. A recent global meta-analysis indicated there was limited information on the effects of climate change on soybean yield compared with maize, rice, and wheat8,10. Large scale studies provide valuable insights to address climate challenges, however, assessments at reduced spatial scale might be needed to capture specific combinations of climate, soil, crop, and management, to inform more resilient agricultural systems in changing climate11. Climate change impacts not only the expected mean crop yield but also the yield stability12,13. The latter is a crucial risk indicator of crop production, which is often overlooked in evaluating climate change impacts14. To date, the expected impact of climate change on soybean yield variability has been rarely reported.

To adapt to the impacts of climate change on crop growth, the relationship between crop yield and change in climate-related factors (temperature, precipitation, solar radiation, and CO2) has been explored in previous studies5,9,15. Although there remains uncertainty, given the complex non-linear relationships between these factors5,9. Machine learning algorithms are capable of evaluating potential non-linear relationships among variables and perform better than conventional linear regression models8,16. Nevertheless, the response of yield stability to change in climate-related factors is not well understood14.

Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) is the main source of protein in animal feed and vegetable oil, and so it plays a key role in global food security. China is the fourth largest soybean producer in the world, producing 20.3 million tonnes soybean with a harvest area of 10.2 million ha in 2022 (http://www.stats.gov.cn/). Of those, Northeast China is responsible for over 40% of total soybean production17. Due to favorable climate and fertile soil18,19, Northeast China is the main rainfed soybean producing area in China. Water availability, as well as the frequency and intensity of drought events, affect regional soybean yield and its stability8,14,20. The region is regarded as most susceptible to climate change, with a rapid warming trend surpassing both global and national averages21,22. Meanwhile, the spatiotemporal change in precipitation brings both risk and opportunity for rainfed soybean production18. However, precise information as to where, how, and to what extent water availability and soybean yield change under future climate scenarios has not been available in the Northeast China.

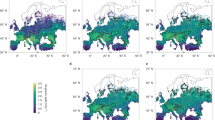

In this study, we quantify the expected impacts of projected climate change on soybean production across five subregions of Northeast China (Fig. 1). A combination of a process-based crop model and a machine learning algorithm was used to perform our study (Supplementary Fig. 1). The specific objectives were to (1) investigate future climate change impacts on climate resources and impacts on soybean phenology; (2) project changes in soybean drought stress, yield, and yield stability under climate change; (3) identify the key climatic factors driving changes in these variables. The expected outcome is that the scalling down predictions to regional levels can better inform more relevant and actionable pathways to more resilient soybean production systems under variable and changing climates.

The region can be divided into five subregions: Xinganling, Sanjiang Plain, Songliao Plain, Changbaishan, and Liaodong based on climatic and socioeconomic conditions. The cropland raster is provided by Data Center for Resources and Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.resdc.cn). The values into right small figures indicate the expanding acreages of soybean planting region due to climate change (unit: 105 ha).

Results

Crop model evaluation and simulation framework

After calibration, the CROPGRO-Soybean model simulated satisfactorily soybean development, growth and yield across the Northeast China (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Text). The validated model was used to simulate soybean growth and yield for each site under baseline (1991–2020) and future periods (2021–2050) (34,080 site-year simulations in total), and interpolated to explore regional results (Supplementary Fig. 1). The three emission scenarios and five GCMs were considered in our study. In the latest Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6), the shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) were proposed by integrating socioeconomic and energy-emissions-land use scenarios23. The SSP1-2.6 represents a relatively optimistic trend for human development in which sustainable practices would be increasingly applied with a global average radiative forcing level of 2.6 Wm-2 in 2100. The SSP2-4.5 represents a central pathway in which trends continue historical patterns with an intermediate forcing level of 4.5 Wm-2 in 2100. The SSP5-8.5 represents a relatively pessimistic pathway in which energy and fossil-based would be intensively used to produce a high radiative forcing level of 8.5 Wm-2 in 2100. The three scenarios widely involved characteristics of climate change in the future, thus were used in our research and hereafter named the low, medium, and high emission scenarios. Results from various GCMs were averaged to reduce uncertainty of projections. Based on simulations, the random forest model was constructed to identify key climate drivers in change in soybean drought stress (the degree to soybean is limited by natural precipitation, Methods), yield, and yield stability.

Projected change in soybean phenology and major climatic resource

The tested climate change scenarios consistently reduced soybean vegetative growth duration (from sowing to flowering), with the highest absolute change of 3.6 d (p < 0.05) under the high emission scenario (Fig. 2). The shorter reproductive growth duration (from flowering to maturity) in future climates was observed for most sites, but reproductive growth duration was prolonged in certain sites compared with baseline period. For the whole growth period, a similar shortening trend was found by 2050 in the Northeast China, ranging from 3.0 d to 4.3 d, being more evident under the high emission scenario (p < 0.01). In term of annual changes, the duration of soybean whole growth period showed more rapidly decreasing trends across the Northeast China under future climates (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1).

a Vegetative growth period (VGP). b Reproductive growth period (RGP). c Whole growth period (WGP). The simulated results for future climate are ensemble means of the five general circulation models, including GFDL-ESM4, IPSL-CM6A-LR, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MRI-ESM2.0, and UKESM1.0-LL. The difference in means between future scenario and baseline is evaluated by Student’s T test, * and ** indicate significance at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, ns indicates not significant.

All GCMs projected higher mean maximum temperature, mean minimum temperature, and total precipitation, yet lower mean solar radiation during soybean growth period in the future (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). In more detail, mean maximum and minimum temperatures significantly increased by 0.8–1.5 °C and 1.0–1.3 °C (p < 0.01) among various scenarios, respectively, with higher increases under the higher emission scenario. Total precipitation is projected to increase by 40.8–61.3 mm, with the highest increase for the low emission scenario. Projected decreases in solar radiation were greater under the high emission scenario, ranging 0.4–0.6 MJ m-2. Compared with baseline period, the mean maximum and minimum temperatures and solar radiation showed the greater annual increasing rate under all future scenarios, but the slighter increases for total precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 2).

a Mean maximum temperature (Tmax). b Mean minimum temperature (Tmin). c Total precipitation (Pr). d Mean solar radiation. The simulated results for future climate are ensemble means of the five general circulation models, including GFDL-ESM4, IPSL-CM6A-LR, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MRI-ESM2.0, and UKESM1.0-LL. The difference in means between future scenario and baseline is evaluated by Student’s T test, * and ** indicate significance at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, ns indicates not significant.

Projected change in soybean drought stress

Soybean yield was strongly limited by precipitation, especially in western regions of the Northeast China (Fig. 4a). The drought stress was between 14% to 32% among subregions, and 27% for whole region under baseline climate (Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, future soybean would experience less water stress across the Northeast China (Fig. 4b–d and Supplementary Fig. 6). All scenarios showed a similar spatial pattern of declining drought stress, but the magnitude varied among them, with larger decreases in western regions. At the subregional level, the most evident declines were observed in Liaodong subregion, with averages of 10.2–12.2% by mid-century (Fig. 5a). Overall, the soybean drought stress of the Northeast China declined particularlly under low emission scenario (10.4%), followed by high (8.7%) and medium (6.7%) emission scenarios compared with baseline period.

a Drought stress under the baseline (1991–2020). b Change under the low emission scenario. c Change under the medium emission scenario. d Change under the high emission scenario. The simulated results for future climate (2021–2050) are ensemble means of the five general circulation models, including GFDL-ESM4, IPSL-CM6A-LR, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MRI-ESM2.0, and UKESM1.0-LL.

a Drought stress. b Yield. c Yield CV. I, Xinganling suberegion; II, Sanjiang plain; III, Songliao plain; IV, Changbaishan suberegion; V, Liaodong subregion, NFR, Northeast China. Box boundaries indicate the upper and lower quartiles, bars in boxes indicate the 50th percentiles, the circles indicate the mean values, and whiskers below and above the box indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles, respectively. In each box, there are 5 predictions with from five general circulation models in the region under future climates.

Projected change in soybean yield and yield stability

Soybean yield showed an increasing trend from northwestern to southeastern regions, with a mean of 3.63 t/ha under baseline period across the Northeast China (Fig. 6a). Among subregions, soybean yields ranged between 2.89 t/ha to 4.11 t/ha, with the lowest value in Xinganling subregion (Supplementary Table 3). All climate change scenarios increased soybean yield, though particularly in the western and northern regions (Fig. 6b–d and Supplementary Fig. 7). Yield changes were different across the different subregions, while small variances were found among three climate scenarios. Yield change was projected to increase by 34.2–46.4% in the Xinganling subregion under future scenarios. Comparably, the smallest increases, i.e., 12.2–15.8%, were observed in the Changbaishan subregion (Fig. 5b). Overall, the projected soybean yield across the Northeast China would increase by 23.4%, 19.4%, and 24.5% under low, medium, and high emission scenarios, respectively. Compared with baseline period, the annual increasing rate of soybean yield across the Northeast China was greater under future scenarios, with the rapidest increase under the high emission scenario (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 4).

a Yield under the baseline (1991–2020). b Yield change under the low emission scenario. c Yield change under the medium emission scenario. d Yield change under the high emission scenario. e Yield CV under the baseline. f Yield CV change under the low emission scenario. g Yield CV change under the medium emission scenario. h Yield CV change under the high emission scenario. The simulated results for future climate (2021–2050) are ensemble means of the five general circulation models, including GFDL-ESM4, IPSL-CM6A-LR, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MRI-ESM2.0, and UKESM1.0-LL.

An increasing trend in soybean yield coefficient-of-variation (CV) was observed from southeast to northwest under baseline climate, i.e., more stable soybean yields in southeast regions (Fig. 6e). Yield CV ranged from 0.21 to 0.51 among subregions, and 0.39 for the Northeast China (Supplementary Table 3). All scenarios projected a decrease in yield CV by mid-century (Fig. 6f–h and Supplementary Fig. 9). Substantial declines in yield CV were observed in the western and northern parts of the Northeast China under the low and high forcing scenarios. Xinganling had the largest decreases in yield CV, while the smallest decreases were observed for the Changbaishan subregion (Fig. 5c). For the whole Northeast China, soybean yield CV was projected to reduce by 0.10–0.13 under future climates, indicating yield stability would increase in the future.

The change in yield CV was linked to changes in soybean mean yield and standard deviation (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 5–7). The soybean mean yield increased in 93.0–96.6% of simulated sites under future scenarios, while the standard deviation decreased in 62.8–75.5% of all sites across the Northeast China (Table 1). In sites where yield CV decreased, 62.3–74.1% of sites were dominated by the increasing mean yield and decreasing standard deviation. About 10.1–18.3% of sites were observed increasing trends in yield CV in the future, CV change was mainly due to increases in yield standard deviation.

Key driving factors and their response relationships

Pearson correlation analysis showed that soybean yield significantly correlated with yield CV and drought stress (p < 0.001) (Fig. 7). Regions with high yield had high yield stability, i.e. less climate risk, and less yield loss induced by rainfall limitation. This explained the results in the Changbaishan subregion (Figs. 4a, 6a, e). Thus, a positive correlation was found between yield CV and drought stress.

a Soybean yield and yield CV. b Soybean yield and drought stress. c Yield CV and drought stress. I, Xinganling suberegion; II, Sanjiang plain; III, Songliao plain; IV, Changbaishan suberegion; V, Liaodong subregion. The solid lines are linear least-squares fit lines, and shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence interval of fit lines. The ** indicate significance of correlation coefficients (r) at the p < 0.01 level based on Student’s t-test, and p values indicate significance of linear of the regression based on F-test.

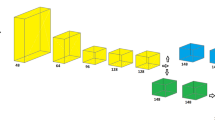

The fine-tuned random forest models performed well in explaining the future changes in soybean drought stress, yield, and yield stability across the Northeast China, with R2 of 0.52–0.57 (Fig. 8 and Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). Model performances on each subregion also had relative high R2, with 0.53–0.75, 0.58–0.78, and 0.55–0.75 for the three dependent variables (Supplementary Figs. 12–14).

a Variable importance of climatic factors in projected changes in drought stress. b Variable importance of climatic factors in projected changes in soybean yield. c Variable importance of climatic factors in projected changes in yield CV. d Partial dependence plots of top important variables affecting change in drought stress. e Partial dependence plots of top important variables affecting yield change. f Partial dependence plots of top important variables affecting change in yield CV. The optimized parameters and coefficient of determination (R2) of various models are also shown in the figure, including the number of trees in the forest (ntree), the number of variables tried at each node (mtry), and the minimum number of observations in each of terminal node (nodesize). V, vegetative growth period; r, reproductive growth period. In a–c, top 10 variables are only shown in the figures, and corresponding full names of the abbreviation are shown in Table 2.

Random forest model identified the total precipitation during reproductive growth period was the largest contributor for change in soybean drought stress across the Northeast China, with a relative importance of 58.6% (Fig. 8a). The soybean drought stress decreased with increasing precipitation during reproductive period under future climates, then reached a plateau when increase in precipitation was above 130 mm (Fig. 8d). The climatic factor was also the most important variable affecting change in drought stress in Songliao Plain and Liaodong subregion, while various major factors were for the other three subregions (Supplementary Fig. 12).

The growing degree days showed relative higher importance in explaining yield change across the Northeast China (Fig. 8b). The growing degree days during vegetative growth period was the most important drivers in yield increase, with importance score of 65.6%, followed by the total precipitation during reproductive growth period. Soybean yield increase tended to be larger in regions characterized by decreasing growing degree days during vegetative growth period relative to the baseline period (Fig. 8e). Additionally, the vapor pressure deficit and solar radiation were important climate drivers to yield increase at subregion level (Supplementary Fig. 13).

The related variables of total precipitation during reproductive growth period were the major influential factors driving change in yield CV across the Northeast China (Fig. 8c). The CV of total precipitation during reproductive growth period had the highest importance (33.5%). When it decreased under climate change, yield CV exhibited substantial declines, after then, the magnitude gradually reduced (Fig. 8b). The factor generally contributed most to yield CV declines at subregion level, and similar response curves were observed, except for Xinganling subregion (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Discussion

Coupled with updated future climate data, the well-validated CROPGRO-Soybean model was used to project change in soybean drought stress, yield, and yield stability across the Northeast China by the middle of the 21st century. Then, random forest model was built to explore response mechanism of soybean drought stress, yield, and yield CV to changes in climate drivers. The multi-GCMs ensemble ensures accuracy and robustness of our projections. These results could be beneficial to develop adaptive strategies for resilient soybean production under climate change in the Northeast China and other similar soybean production regions around the world.

Climate warming can be expected to expand the potential area of soybean planting. The northern boundary shifted northwards with the largest changes under the high emission scenario (Fig. 1). The expanding area was 0.72 × 105, 1.56 × 105, and 1.98 × 105 ha under low, medium, and high emission scenarios, respectively. This stemmed from improvements in thermal resources in high-latitude regions22. Our results again validated the importance of assessing changes in both land availability and yield for future crop production under the changing climates24. Except for thermal indexes used in this study, other climatic factors and technological developments can also affect the spatial distribution of cropping system25. The expansion in potential area of soybean planting was supported by increase in soybean climate suitability under climate change in the Northeast China19,26. When planting soybean in these new regions, projected yields under future climates were lower than the average for the entire Northeast China (Supplementary Fig. 15), and faced higher climate risks (higher yield CV). This might be explained by that the constant soybean maturity groups and related managements were used in our simulations. Therefore, adaptation strategies, such as advancing planting dates and using longer variety cycles, in rotations with maize, should be considered to mitigate climate risks and increase resilience of soybean production in future study18,27.

In our simulations, the soybean yield projected to generally increase under future climate change (Fig. 6b–d and Supplementary Fig. 8). Different from the negative effect on average soybean yield at global scale3,6, this highlighted spatial heterogeneity of climate change impact on crop yield and importance of studies conducted at smaller spatial scale informed by local knowledge and growing conditions8. Similar positive effects of climate change on soybean were demonstrated in Southern Brazil13, the US Corn Belt28, and Argentina29. In the high-latitude Northeast China, the temperature during soybean growth period is below the optimal threshold under baseline condition30,31 (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). The higher temperature would increase soybean photosynthesis rate, particularly for the rate of pod addition and rate of individual seed growth32, thus produce higher yield in the future9,27. The mean maximum temperature of soybean growth period still is below the temperature threshold (30 °C) by 2050 even under the high emission scenario33 (Supplementary Fig. 5). With continuous increase in temperature, soybean might suffer heat stress and yield loss in the Northeast China after the middle century9,18 (Supplementary Fig. 5). The larger precipitation reduces impacts of drought on rainfed soybean growth and biomass accumulation under future climates20. Elevated CO2 increases soybean photosynthesis and dry matter accumulation and decreases leaf stomatal conductance to reduce the negative impact of drought on rainfed soybean growth13,34. The positive effects of elevated CO2 are more significant when the rising temperature is below the soybean optimum temperatures35. The decreasing solar radiation results in reductions in soybean yield36, although in our results, increases in temperature, precipitation, and CO2 concentration more positively affected soybean yields under the future climate scenarios. In terms of increasing magnitude of soybean yield, our estimates were slightly higher than previous studies9,27. This could be explained by that they considered impacts of extreme climatic events and crop pests and diseases on soybean yield; however, the complex interactions were not captured well by the CROPGRO-Soybean model in this study37,38. Soybean yield CV and drought stress projected to have substantial declines in the Northeast China under future scenarios (Figs. 4b–d and 6f–h). Our previous study suggested that precipitation during soybean growth period above 500 mm could satisfy water requirement of soybean growth in the Northeast China17. Compared with baseline, more sites reached the precipitation threshold under future climates (Fig. 3c), thus, decreasing drought stress on soybean production.

Projected changes in the drought stress, yield, and yield CV for entire Northeast China exhibited very slight differences across various scenarios (Fig. 5). This was driven by similar climatic conditions, regardless of maximum and minimum temperatures, precipitation, solar radian, and CO2 concentration across three scenarios before 2050 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Bhattarai et al. 28 reported consistent soybean yield changes were projected under future various emission scenarios in the US Corn Belt before 2050, while yield changes varied across emission scenarios at the end of the century. Thus, the time of future climate data is also essential to be mentioned when climate change impacts are reported. Within the Northeast China, spatial heterogeneity still caused great differences in projected results among various subregions in the future (Fig. 5). Our results indicated regions with low yield, high yield CV, and high drought stress under baseline generally tended to experience larger change under future climate scenarios (Figs. 4 and 6). Projected impact of future climate on crop growth and yield depended on not only future changes in climate factors, such as temperature, precipitation, and solar radiation but also their values under baseline scenario8,14. Compared with other subregions, Xinganling subregion had poorer climate conditions for soybean growth under baseline period (Supplementary Fig. 4). The improvement in temperature and precipitation would cause significant changes in soybean yield and yield stability in the subregion under future climates30. Liaodong subregion experienced more frequent drought in soybean growth period than other regions of the Northeast China under baseline condition39, therefore, enough precipitation reduced most regional yield loss induced by water deficit in the future (Fig. 5a). Our simulations showed wide range of variation across GCMs under the future period (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figs. 6–9), thus the selection of GCM would caused substantial impacts on evaluation and conclusions. Previous studies reported the GCM is one of main sources of uncertainty in climate change projection on crop yield4,9, and highlighted the multi-GCMs ensemble is effective pathway to reduce the uncertainty and imporve relsults reliability13,40.

Crop yield change under climate warming was together driven by climate (temperature, precipitation, radiation, and CO2), soil, and adaptive practices8,14. The present study identified that projected increases in soybean yield were mainly driven by change in the growing degree days during vegetative growth period (Fig. 8b). The growing degree days is a crucial index measuring thermal condition and drives soybean phenology development and yield formation in CROPGRO-Soybean model13,41. Climate warming accelerates soybean development32, shortening the vegetative period more than the reproductive period (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Although temperature increased in the future, the decreases in growing degree days during the vegetative period were observed in most sites due to largely shortening vegetative growth duration (Supplementary Fig. 16). We found these sites had larger decreases in the growing degree days during the vegetative period, accompanied by smaller reduction and even increases in the normalized photothermal quotient during reproductive stages under future climates (Supplementary Fig. 16). The normalized photothermal quotient is an integrated metric by solar radiation, ambient temperature, and vapor pressure deficit42, reflecting the crop ability of resource capture. The higher value referred as higher yield potential. This further validated that the reduction in growing degree days in the vegetative period is closely associated with yield increases under future climates. Recent studies highlighted that temperature change is an important driver for soybean yield change18,31,43. In the Northeast China, soybean is mainly cultivated under rainfed system, thus, soybean yield is closely limited by precipitation20. Our results indicated the total precipitation during the reproductive period was secondly important factor driving yield increases (Fig. 8b). The its increases effectively mitigated the drought stress of rainfed soybean system (Fig. 8d), and was important to yield improvement under future scenarios38. At the subregion level, spatial differences in climate condition and climate change caused that various climate drivers were identified for each subregion. Most major driving factors described climate change in soybean reproductive period (Supplementary Fig. 13), which is the most sensitive period of soybean growth to weather disruptions16,44. Our results suggested again the importance of reproductive growth period on soybean yield change. The CV of precipitation is crucial driver of rainfed yield stability12,14,45, especially in reproductive growth period (Fig. 8c). The decreasing CV of precipitation caused more stable soybean yield in the future, which was also validated by random forest models based on subregional data except for Xinganling subregion (Supplementary Fig. 14).

This study firstly examines changes in soybean drought stress, yield, and yield stability under future climates across the Northeast China using process-based crop model. However, there are still several uncertainties inherent in climate impact assessment. First, short duration extreme weather events such as heat strokes and excessive rainfall, are major factors affecting crop yield and yield stability, and most crop models yet do not capture the impacts of extreme climates well37. Secondly, the effects of climate change on the incidence of weeds, pests and diseases were also ignored here. Thirdly, the crop model can also be a main source of uncertainty on simulated crop yields4. The CROPGRO-Soybean was the only model used in the present study, which might bring some deviation in results. Multi-crop model ensemble and advanced machine algorithms should be considered to reduce the uncertainties in future work.

Conclusions

The present study projected the future changes in soybean drought stress, yield, and yield stability, and key climate drivers in these changes across the Northeast China by the middle century. Multi-GCMs ensemble showed future climate change increased temperature and total precipitation but decreased solar radiation during soybean growth period. The tested climate change scenarios significantly reduced soybean whole growth period by shortening vegetative growth periods compared with the baseline simulations. Soybean yield increased by 19–24% across the Northeast China under future climate scenarios, accompanied by decreasing trends of 0.10 to 0.13, and 7% to 10% in yield CV and drought stress, respectively. The decreases in yield CV was mainly driven by the increasing mean yield and decreasing standard deviation. Xinganling subregion had substantial improvement in yield and yield stability, although caution is recommended when plating soybean in new regions. The growing degree days during vegetative growth period was the most important factor driving yield increases. The total precipitation during reproductive growth period and its CV were the most critical factor driving decreases in drought stress and yield CV, respectively. Our findings suggest likely positive impacts of climate change on crop production and provide valuable references for developing resilient agriculture and dealing with future climate change.

Methods

Study region

The main soybean planting area in China, the Northeast China, was selected for this study. The region encompasses the northeast part of Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, Jilin, and most parts of Liaoning province, with a total area of 89.8 million ha. It is located between longitudes 119° and 136° East and between latitudes 40° and 54° North, and its climate is characterized as temperate semi-humid. The region can be divided into five subregions: Xinganling, Sanjiang Plain, Songliao Plain, Changbaishan, and Liaodong based on climatic and socioeconomic conditions20. The annual accumulated temperature above 10 °C decreased from 1441–3883 °C⋅d with increasing latitude over 1981–202017. Presently, the low ambient temperatures of the northern part of the Xinganling subregion is the main limitation of soybean production. The potential distribution areas of soybean cropping system were identified under the different climate scenarios (Fig. 1), using the thresholds for annual accumulated temperature above 10 °C (1900 °C·d) and continuous days with mean temperature above 10 °C (115 d) under a guarantee rate of 80% as in Pan et al. 46.

Climate and soil data

Historical climate data (1991–2020) for 74 meteorological stations were acquired from the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System (http://cdc.cma.gov.cn/) (Fig. 1). The dataset included daily mean, maximum, and minimum temperature, precipitation, sunshine hours, and wind speed. To drive the CROPGRO-Soybean model, sunshine hours was converted into solar radiation using the Ångström equation47.

Future daily climate data (2021–2050) were obtained from the Intersectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP)48. Five general circulation models (GCMs) were considered structurally independent and represented the range of equilibrium climate sensitivity across the full Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) ensemble: GFDL-ESM4, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MRI-ESM2-0, IPSL-CM6A-LR, and UKESM1-0-LL4. The dataset was bias-adjusted using the quantile mapping approach and the GSWP3-W5E5 dataset49. Three forcing scenarios were considered in this study: low (SSP1-2.6), mid (SSP2-4.5), and high (SSP5-8.5) climate responses to CO2 concentration, respectively. Projected climate data included mean, maximum, and minimum temperature, precipitation, solar radiation, and wind speed. The annual atmospheric CO2 concentration was derived for three emission scenarios from ISIMIP23 (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Soil data, including proportion of clay and silt, bulk density, pH, soil organic matter, total nitrogen, cation exchange capacity, wilting point, filed capacity, and saturation in different soil layers were extracted from the Global Soil Profile Database for Crop Modeling Applications with 1 km resolution50 (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/).

Simulating soybean growth and productivity

The CROPGRO-Soybean model41, embedded within Decision Support System for Agrotechnology Transfer – DSSAT version 4.7.551, is driven by daily climate data, soil data, crop management data to simulate soybean growth and yield in our study. The soil profile of each site was selected from the nearest grid of global soil database. To capture full genotype × environment × management interactions, five representative soybean cultivars were selected for various maturity groups across the Northeast China52 (Supplementary Fig. 18). The genetic parameters of cultivars were calibrated and validated using the GLUE tool53. Details of the model validation are described in a previous study17, and related data and results also are shown in the Supplementary Table 8, Supplementary Figs. 2 and 19, and Supplementary Text. Soybean sowing date was extracted from China’s major crop growing period atlas54 (Supplementary Fig. 20), and other agricultural practices, such as row space, sowing depth, and planting density, were accessed through local agronomists (Supplementary Table 9). The validated model was used to simulate soybean phenology and water-limited potential yield for 71 sites (excluding 3 sites outside the potential planting region) across the Northeast China (Fig. 1). The initial soil water content at sowing was reset to 75% of field capacity to ensure seed germination and early root establishment55. Except for climate data, soil profile and crop management practices at each site were kept constant for the simulation period (1991–2050) using the ‘Seasonal’ module of DSSAT model. The model was run from at least 10 days before sowing to maturity for each year. To better estimate evapotranspiration56, the Penman-Monteith equation was used in our simulation57. We turned off nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, chemicals, and diseases modules. Yield was converted into 13% moisture content.

Assessing the impacts of future climate change on soybean production

To assess the impacts of climate change, we generated 34,080 simulations, i.e., 71 sites × 30 years of climatology, plus, 71 sites × 30 years × 5 GCMs × 3 emission scenarios. Based on the database, the duration of soybean vegetative growth period (from sowing to flowering), reproductive growth period (from flowering to maturity), and whole growth period (from sowing to maturity), and major climatic indicators during soybean growth season were calculated. Drought stress of rainfed soybean, i.e., the degree to soybean is limited by precipitation, was referred to the relative potential yield gap without and with water limited conditons58. Soybean potential yields were averaged with 30 year outputs for each site under baseline and future periods, then were used to quantify the change in drought stress (Eq. 1). Compared with baseline, the relative difference in yield was calculated to investigate impact of future climate change. Yield coefficient-of-variation (CV) was used to quantify yield stability by the Eq. 214. The lower yield CV, the higher stability and lower climate risk of soybean yield. The absolute change in yield CV was measured for three future scenarios than baseline period. Additionally, the changes in mean yield and yield standard deviation were used to untangle the reasons behind the change in yield CV. The soybean drought stress, yield, and CV at the station scale were interpolated to entire soybean planting region and averaged at the regional level using the Kriging method and zonal statistics tool in ArcGIS 10.6. Final estimates in future periods were based on multi-GCMs mean to constrain uncertainty of projections.

where Yp and Yw were the 30-year mean potential yield without and with water limitation, respectively. Yp was also simulated using validated CROPGRO-Soybean model. σ and µ are standard deviation and mean of soybean yield for each period.

Identifying key drivers affecting future soybean production

Random forest models were trained to (i) identify the major climatic factors driving change in soybean drought stress, yield, and yield CV, and (ii) quantify how dependent variables respond to the most important drivers. Random forest is a non-parametric machine learning algorithm that performs well handling complex and non-linear relationships in datasets59. The absolute changes of average and CV of the nine climatic factors during soybean vegetative and reproductive periods were computed as candidates for each site-GCM-scenario relative to baseline period (Table 2). Here, changes in soybean drought stress under future scenarios were driven by change in average of the nine climatic factors and CO2 concentration (Eq. 3). Similarly, the random forest model between yield change and climatic factors was developed as Eq. 4. For change in yield CV, the change in CV of each climate factor was also included in the model (Eq. 5).

where \(\Delta\) is absolute change under future climates than baseline period; Clim is the nine climate factors in Table 2; v is vegetative growth period; and r is reproductive growth period.

To prevent from model overfitting, the number of variables was reduced by recursive feature elimination. The strategy applied the backward selection technique to eliminate least important variables without losing model accuracy based on coefficient of determination (R2) and root mean squared error (Supplementary Fig. 10). The 10-fold cross-validation with three repeats was used to enhance the effectiveness and robustness of the variable elimination process. This was implemented using the “rfe()” function of the caret R package60. Secondly, the fitted model on the reduced variables was fine-tuned using the grid-search approach to optimize specific hyperparameters of model: (i) the number of trees in the forest (ntree ranging from 500–2000 at 100 intervals), (ii) the number of variables tried at each node (mtry between 1 to n, i.e., the number of variables), and (iii) the minimum number of observations of each terminal node (nodesize ranging from 5–20% of total observations at two percent intervals). The best hyperparameters combination was selected based on the greatest R2 of models using the “train()” function of the caret R package (Supplementary Fig. 11). Then, the fine-tuned model was constructed based on the reduced variables and optimal hyperparameters with 10-fold cross-validation, and performance of model was evaluated with R2. The relative importance of each climate driver was evaluated based on the out-of-bag regression prediction error (%IncMSE) with the “importance()” function of the iml R package59. The most important climatic driver was used to quantify specific effect size on the dependent variable using partial dependency plot created by the pdp R package. All analysis was conducted in R version 4.3.261.

Data availability

The future climate scenario data (2021–2050) are available from the Intersectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (https://data.isimip.org/). The soil data are available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/.

References

Naylor, R. L. The Evolving Sphere of Food Security Illustrated edition, Vol. 398 (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Pastor, A. V. et al. The global nexus of food–trade–water sustaining environmental flows by 2050. Nat. Sustain. 2, 499–507 (2019).

Lesk, C., Rowhani, P. & Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature 529, 84–87 (2016).

Jägermeyr, J. et al. Climate impacts on global agriculture emerge earlier in new generation of climate and crop models. Nat. Food 2, 873–885 (2021).

Rosenzweig, C. et al. Assessing agricultural risks of climate change in the 21st century in a global gridded crop model intercomparison. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3268–3273 (2014).

Zhao, C. Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9326–9331 (2017).

Lobell, D. B., Schlenker, W. & Costa-Roberts, J. Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science 333, 616–620 (2011).

Abramoff, R. Z. et al. Adaptation strategies strongly reduce the future impacts of climate change on simulated crop yields. Earth Future 11, e2022EF003190 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Integrating machine learning and environmental variables to constrain uncertainty in crop yield change projections under climate change. Eur. J. Agron. 149, 126917 (2023).

Hasegawa, T. et al. A global dataset for the projected impacts of climate change on four major crops. Sci. Data 9, 58 (2022).

Bracho-Mujica, G. et al. Effects of changes in climatic means, variability, and agro-technologies on future wheat and maize yields at 10 sites across the globe. Agric. For. Meteorol. 346, 109887 (2024).

De Vos, K. et al. Rice availability and stability in Africa under future socio-economic development and climatic change. Nat. Food 4, 518–527 (2023).

Figueiredo Moura da Silva, E. H. et al. Impact assessment of soybean yield and water productivity in Brazil due to climate change. Eur. J. Agron. 129, 126329 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Future climate change significantly alters interannual wheat yield variability over half of harvested areas. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 094045 (2021).

Lobell, D. & Asner, G. Climate and management contributions to recent trends in US agricultural yields. Science 299, 1032 (2003).

Goulart, H. M. D., van der Wiel, K., Folberth, C., Boere, E. & van den Hurk, B. 2023. Increase of simultaneous soybean failures due to climate change. Earth Future 11, e2022EF003106 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Prospects for soybean production increase by closing yield gaps in the northeast farming region, china. Field Crops Res. 293, 108843 (2023).

Xu, Q. et al. Assessing climate change impacts on crop yields and exploring adaptation strategies in northeast china. Earth Future 12, e2023EF004063 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Modeling climatically suitable areas for soybean and their shifts across china. Agric. Syst. 192, 103205 (2021).

Yin, X. et al. Impacts and adaptation of the cropping systems to climate change in the northeast farming region of china. Eur. J. Agron. 78, 60–72 (2016).

Piao, S. et al. The impacts of climate change on water resources and agriculture in China. Nature 467, 43–51 (2010).

Yang, X. et al. Adaptation of agriculture to warming in northeast china. Clim. Change 84, 45–58 (2007).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The scenario model intercomparison project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model. Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Wang, B. et al. Australian wheat production expected to decrease by the late 21st century. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 2403–2415 (2017).

Li, S. et al. Changes in planting methods will change the potential distribution of rice in south china under climate warming. Agric. For. Meteorol. 331, 109355 (2023).

Feng, L., Wang, H., Ma, X., Peng, H. & Shan, J. Modeling the current land suitability and future dynamics of global soybean cultivation under climate change scenarios. Field Crops Res. 263, 108069 (2021).

Guo, S. et al. Adapting crop land-use in line with a changing climate improves productivity, prosperity and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Agric. Syst. 217, 103905 (2024).

Bhattarai, M. D., Secchi, S. & Schoof, J. Projecting corn and soybeans yields under climate change in a corn belt watershed. Agric. Syst. 152, 90–99 (2017).

Casali, L., Herrera, J. M. & Rubio, G. Modeling maize and soybean responses to climatic change and soil degradation in a region of south america. Agron. J. 113, 1381–1393 (2021).

Zhang, J., Liu, Y. & Dai, L. Agricultural practice contributed more to changes in soybean yield than climate change from 1981 to 2010 in Northeast China. J. Sci. Food Agric. 102, 2387–2395 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Genetic progress battles climate variability: drivers of soybean yield gains in china from 2006 to 2020. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 43, 50 (2023).

Boote, K. J., Prasad, V., Allen, L. H., Singh, P. & Jones, J. W. Modeling sensitivity of grain yield to elevated temperature in the DSSAT crop models for peanut, soybean, dry bean, chickpea, sorghum, and millet. Eur. J. Agron. 100, 99–109 (2018).

Schlenker, W. & Roberts, M. J. Nonlinear temperature effects indicate severe damages to U.S. crop yields under climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15594–15598 (2009).

Rogers, A., Ainsworth, E. A. & Leakey, A. D. B. Will elevated carbon dioxide concentration amplify the benefits of nitrogen fixation in legumes? Plant Physiol. 151, 1009–1016 (2009).

Vara Prasad, P. V., Allen, L. H. & Boote, K. J. Crop responses to elevated carbon dioxide and interaction with temperature. J. Crop Improv. 13, 113–155 (2005).

Liu, Y. & Dai, L. Modelling the impacts of climate change and crop management measures on soybean phenology in china. J. Clean Prod. 262, 121271 (2020).

Schewe, J. et al. State-of-the-art global models underestimate impacts from climate extremes. Nat. Commun. 10, 1005 (2019).

Guo, S. et al. Impacts of mean climate and extreme climate indices on soybean yield and yield components in northeast china. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 156284 (2022).

Shi, W., Wang, M. & Liu, Y. Crop yield and production responses to climate disasters in china. Sci. Total Environ. 750, 141147 (2021).

Wang, B. et al. Pathways to identify and reduce uncertainties in agricultural climate impact assessments. Nat. Food 5, 550–556 (2024).

Boote, K. J., Jones, J. W., Batchelor, W. D., Nafziger, E. D. & Myers, O. Genetic coefficients in the cropgro-soybean model: links to field performance and genomics. Agron. J. 95, 32–51 (2003).

Rodriguez, D. & Sadras, V. O. The limit to wheat water-use efficiency in eastern Australia. I. Gradients in the radiation environment and atmospheric demand. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 58, 287–302 (2007).

Ortiz-Bobea, A., Wang, H., Carrillo, C. M. & Ault, T. R. Unpacking the climatic drivers of US agricultural yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 064003 (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. Soybean yield variations and the potential of intercropping to increase production in china. Field Crops Res. 291, 108771 (2023).

Webber, H. et al. Diverging importance of drought stress for maize and winter wheat in Europe. Nat. Commun. 9, 4249 (2018).

Pan, T., Zhang, D. & Zhang, W. The climatic regionalization of soybean in northeast China. Soybean Science 2, 1–13 (1983).

Angstrom, A. Solar and terrestrial radiation. Report to the international commission for solar research on actinometric investigations of solar and atmospheric radiation. Q. J. Roy. Meteorol. Soc. 50, 121–126 (1924).

Warszawski, L. et al. The inter-sectoral impact model intercomparison project (ISI–MIP): project framework. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3228–3232 (2014).

Lange, S. Trend-preserving bias adjustment and statistical downscaling with ISIMIP3BASD (v1.0). Geosci. Model. Dev. 12, 3055–3070 (2019).

Han, E., Ines, A. V. M. & Koo, J. Global High-Resolution Soil Profile Database for Crop Modeling Applications. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/1PEEY0 (2015).

Jones, J. W. et al. The DSSAT cropping system model. Eur. J. Agron. 18, 235–265 (2003).

Song, W. et al. Precise classification and regional delineation of maturity groups in soybean cultivars across china. Eur. J. Agron. 151, 126982 (2023).

He, J., Jones, J. W., Graham, W. D. & Dukes, M. D. Influence of likelihood function choice for estimating crop model parameters using the generalized likelihood uncertainty estimation method. Agric. Syst. 103, 256–264 (2010).

Mei, X., Liu, Q. & Yan, C. China’s Major Crop Growing Period Atlas (ed. Mei, et al.) 129–140 (Zhejiang Science and Technology Press, 2016).

Justino, L. F. et al. Assessment of economic returns by using a central pivot system to irrigate common beans during the rainfed season in central Brazil. Agric. Water Manage. 224, 105749 (2019).

Sau, F., Boote, K. J., Bostick, W. M., Jones, J. W. & Mínguez, M. I. Testing and improving evapotranspiration and soil water balance of the DSSAT crop models. Agron. J. 96, 1243–1257 (2004).

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D. & Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration—guidelines for computing crop water requirements—FAO irrigation and drainage paper 56. FAO 300, D05109 (1998).

Aramburu Merlos, F. et al. Potential for crop production increase in Argentina through closure of existing yield gaps. Field Crops Res. 184, 145–154 (2015).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Probst, P., Wright, M. N. & Boulesteix, A. L. Hyperparameters and tuning strategies for random forest. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 9, e1301 (2019).

R Core Team. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/ (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1500202) and the China Scholarship Council (202306350123).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. and Q.C. conceived and designed the study; J.Z., Y.W., and M.Z. prepared model input data; J.Z., D.R., P.D., and Z.T. performed the simulations, data processing, and analysis; J.Z. wrote the first draft, while other co-authors have contributed in improving the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

We would like to declare that Prof. Daniel Rodriguez is currently serving as an editor for this journal. To maintain transparency and ensure the integrity of the peer review process, Daniel Rodriguez has not been involved in the editorial or decision-making processes of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, J., Wang, Y., Zhao, M. et al. Anticipated changes in soybean drought stress and yield stability under future climates in Northeast China. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 14 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00053-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00053-5

This article is cited by

-

Yield gaps in soybean: causes and pathways for increasing yield in smallholder farming from Northeast China

Agronomy for Sustainable Development (2025)