Abstract

Climate change, import restrictions, and global conflicts are significantly impacting brewing raw material supply and costs. To shield the malting and brewing industries from these disruptions, alternative crops to barley must be explored. Rice presents a promising option, yielding twice as much per hectare as barley and showing greater climate resilience. Monte Carlo simulations estimated the economic and agronomic impact of using rice for malting. While rice malt is more expensive to produce, it remains an attractive gluten-free alternative. Beer brewed from 100% rice malt costs 33% more than barley-based beer but reduces acreage requirements by 50–67%. Using rice malt as an adjunct can lower production costs by 2–12%. This methodology can estimate malting costs for other grains and locations. Unlike barley, rice is widely cultivated, this work highlights the future competitiveness of rice as a viable malting material for countries reliant on unstable barley imports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change, import restrictions, and global conflict pose a significant threat to the malting and brewing industries. Barley yield is projected to drop by 17%1 by 2050 and higher temperatures are negatively impacting barley quality leading to increased protein and higher gelatinization temperatures2. Malting barley must meet strict quality standards (e.g., < 13% protein content, 95 + % germination)3 and if these criteria are not met, barley is downgraded to feed barley which commands a significantly lower market value. Despite barley being cultivated in many places (Fig. 1A), it is important to mention that these statistics do not differentiate between malting and feed barley and this means that malting barley production is even likely lower than shown on Fig. 1A.

In North America, high quality malting barley is mostly grown in colder climates (e.g., northern areas of the United States and Canada)4. To combat the impact of rising temperature on barley quality5, barley production is moving further north into Canada. Additionally, unpredictable weather conditions and lower feed barley prices drive farmers to switch to less risky crops. For example, in the USA barley had a drop in production (27%) and acreage (23%) from 2023 to 2024 (Table S1)6. Therefore, to brew all-malt beers (e.g., Pils, lager, ales) countries like the USA (Fig. 1C) will need to import barley malt from more temperate regions (Fig. 1D). This shift in acreage can create increased price variability as tariffs and currency fluctuation also have an impact on raw material costs.

While winter barley and climate-resilient barley varieties offer potential solutions to these challenges, winter barley presents some quality challenges and breeding new barley varieties requires significant time7,8. Therefore, it is crucial for the malting and brewing industries to have alternative (malted) starch sources. Studies have shown that sorghum9, corn10, millet11, intermediate wheatgrass12, and rice13,14,15,16,17,18,19 can be malted. Malting is the controlled germination of cereal, separated into three main steps: steeping (i.e., alternate periods of wet and dry rests), germination (i.e., controlled growth), and kilning (i.e., drying)3,20,21. From an industrial perspective, millet and intermediate wheatgrass production and yield are significantly lower than barley and likely unable to meet industry demand (Table 1). While corn has the highest yield, corn is not ideal for malting due to high lipid content and undesired flavors22. Sorghum, likewise, has inherent undesirable aromas that must be mitigated to achieve beers with consumer-accepted flavor profiles23. Amongst these cereals, rice emerges as the most promising malting alternative as rice has higher yield than barley ( ~ 2–3x, Table 1), good malting qualities18, neutral flavor15, and long grain rice has a comparable cost to malting barley (Table 1).

Rice is a tropical grain cultivated globally24 which thrives especially in warmer regions such as the southern USA24,25, tropical and subtropical countries (Fig. 1B)26. Previous research suggests that rice yields are less vulnerable to climate change26, with estimated declines ranging from 3% to 10% by 210027. California grows mostly short and medium grain rice for export market, therefore the average price of rice (short, medium, and long grain rice) in the US ($441/t) is higher than long grain rice ($374/t) and medium grain rice excluding California ($410/t).

Rice is traditionally processed into white rice through post-harvest steps that include dehulling to produce brown rice, followed by milling and polishing28. Kernels may break during processing and receive different denominations based on the size: head rice (HR, whole kernels), second heads (SH, large broken kernels) and brewer’s rice (BR, small broken kernels) are defined as 100–75%, 75–50%, and < 25% of the whole kernel length, respectively24. BR provides a cost-effective extract (i.e., fermentable sugar) material for the brewing industry24 and is a reutilization of a by-product from the milling industry. However, using BR has its drawbacks, including a short shelf-life29, no endogenous enzyme activity for starch breakdown, higher gelatinization temperature than the optimum temperature for barley amylases, lower free amino nitrogen (FAN) compared to barley malt28,30 and no hull for filtration. To overcome these issues, BR has to be used relatively quickly and often requires an extra vessel (cereal cooker) to easily pre-gelatinize rice starch prior to utilization in the brewing process28. Additionally, there are a number of processing steps that need to be considered if 30 + % of the extract comes from milled rice such as the addition of an exogenous source of amino nitrogen which needs to be added for a healthy fermentation, the additional of rice hulls which are is added to aid in wort filtration, and the reliance on exogenous enzymes for starch breakdown (saccharification)28,30. These challenges make BR capital-intensive and prevent small craft breweries from utilizing this material. Alternatives to overcome these issues are pre-gelatinized rice (e.g., flaked rice) and rice malt. While pre-gelatinized rice requires only a single vessel28 it is more costly and has a questionable shelf-life.

Rice malt, on the other hand, overcomes most of these challenges. Rice malt contains sufficiently high amount of FAN to conduct healthy fermentation18, has enough endogenous enzymatic activity for self-saccharification19, and can be used in a single vessel. Additionally, the presence of hull protects the bran from oxidation, extends the shelf-life of the raw material, and aids in filtration. Moreover, recent research has shown that rice malt can have novel brewing properties17,18,19 (e.g., wort colors varying from pale yellow to reddish, enzymatic profile, etc.) while also being gluten-free.

When proposing a transition or addition of a novel product into the food industry, several factors must be considered, including the supply of raw materials, the technology required to process them, flavor profiles, and the costs of the raw materials and final products31. In this analysis, we evaluated the economic and agricultural feasibility of producing rice malt and brewing beer with it, either as a base malt compared to barley or as an adjunct alongside traditional milled rice products (e.g., brewer’s rice, second heads, and head rice). To predict these costs and impacts, Monte Carlo simulations were employed, integrating data from scientific research (e.g., extract, malting losses) and surveys (e.g., yield, production, harvested area, raw materials, and utilities costs). Ultimately, this study 1.) underscores the potential of rice malt as a viable brewing ingredient and 2.) provides a supplemental file (Supplementary Data) which can be used by scientists and industry members to redo this analysis with other novel grains and/or locations.

Results

Barley malt holds global importance as the primary raw material in brewing after water, with a global trade value of $4.75 billion in 202232. The increasing frequency of extreme drought/heat events not only affects grain yield and quality, but also beer production and quality, ultimately driving up beer prices1. The top barley malt importing countries were Brazil ($715 M), Mexico ($371 M), USA ($280 M), Japan ($261 M), and Vietnam ($238 M)32. The USA, Brazil, and Mexico rank among the top beer-producing countries globally33 following China (Fig. 1C). This imbalance in beer production and barley malt net trade (Fig. 1D), combined with the large amount of rice grown in these countries (Fig. 1B), highlights the potential for the utilization of rice malt. For example, malting barley comprises about 75% of the USA barley production34, with estimated average harvested area of ~734,000 ha and output of ~2.87 million t (Table 1, ~12% moisture). The domestic malting barley production in the USA is insufficient to supply the internal demand of the American brewing industry of ~2.38 million t of barley malt35 (~4% moisture, ~10.5% malting loss)3,35, which leads to a ~ 18% net importation of barley malt (Fig. 1D).

To investigate if rice could serve as a replacement for barley the agronomical values of rice and barley were compared (Table 1). In the USA, long grain rice (LGR) had an average yield of 8.23 t/ha (Table 1), slightly below the average in Arkansas (8.38 t/ha), the largest USA rice producing state. This yield is more than 2.5x the yield of barley per hectare (3.28 t/ha). Field tests in Arkansas revealed an even higher yield for pureline long grain rice (PLR) (9.18 t/ha), with hybrid long grain rice (HLR) achieving the highest yield (10.76 t/ha). As a result, hybrid rice acreage has expanded significantly, accounting for 53.8–73.5%36 of Arkansas total acreage in recent years. The state’s average LGR production reached 3.8 million tons which is comparable to the nation’s total production of feed and malting barley combined. Medium grain rice (MGR) is typically grown under contract for specific value-added uses and, therefore, covers a limited area of 81,000 ha. Despite a lower yield (8.15 t/ha) compared to LGR, MGR still outperforms barley.

Next, the costs associated with malting production were simulated (Table 2) to investigate if there was a price parity for processing. Jonesboro, AR, was chosen as the location for the malt production cost simulations as the bulk of rice production occurs in Northeastern Arkansas. For the simulations it was assumed that a working malt house equipped with a steep-germination and kiln (SG&K) unit for malting with a capacity of 4 t per batch was available. Although previous studies have optimized malting protocols for rice3,15,18, generally rice requires longer steeping, germination, and kilning times than barley (Table S2). However, it is important to note that the malting procedure could be further improved for individual varieties of rice as interest in rice malt grows. Based on the current ‘optimal’ malting procedures, the simulated malt house could produce 56 annual batches of rice malt and 67 batches of barley malt (Table S2). Calculations were performed as previously described37 and the costs associated with malting rice were ~20% higher than barley malt (Table 2). This was a result of the increased time spent on operations which led to lower throughput and ultimately higher fixed costs (i.e., labor & non-operational costs).

Then the price of the final product was simulated to investigate the economic feasibility of rice malt compared to barley malt (Table 3). The simulated cost of raw materials was not different for malting barley and LGR ( ~ $353−374/t, p < 0.05, Tables 1 and 3), while MGR had the highest cost ($410/t, p < 0.05). Based on previous research, the costs were also estimated for the best-known rice malting cultivars (i.e., highest extract and lowest malting loss): pureline long grain rice (PLR), hybrid long grain cultivar (HLR), and medium grain rice (PMR). The estimated costs (i.e., raw material costs + processing costs) of rice malt (PLR, HLR, PMR) per ton of malt were not statistically different between each other (~$1068−1104/t, p < 0.05), but higher than barley malt (BM, $909/t, p < 0.05) and milled rice (BR, SH, HR) ($561−$821/t). Based on literature values, malting barley has the lowest malting loss (10.5% dry-matter, d.m.)3, followed by MGR (12.6% d.m.), and LGR varieties ( ~ 15% d.m)18. The higher malting losses for rice resulted in an additional ~2−5% increase in the price per ton (Table 3) compared to barley. However, the prices between barley malt (BM) and rice malts shared the same price values in ~20−25% of the simulations.

To estimate the brewing value of the rice malt, the price of per ton of extract was then determined (Table 3). Previous research has shown that rice malt ( ~ 63–73% w/w extract), barley malt ( ~ 81.4% w/w extract), and milled rice ( ~ 85% w/w extract) yield different extracts during the brewing process. Price per ton was then normalized for extract for further comparisons. Generally, the price per extract is a decisive factor for brewers and is calculated by dividing the malt or adjunct (i.e., supplemental source of carbohydrates than the barley malt) price by the extract yield of malt or adjunct. Milled rice had the lowest price per ton of extract ($660–966/t), followed by BM ($1000/t), PLR, PMR, LGR, HLR, and MGR (Table 3). The top rice malting cultivars had significantly lower price per ton of extract than the average LGR or MGR (p < 0.05). This reinforces the importance of identity protecting rice varieties in contracting rice acreage for malting purposes and potentially highlights the importance of malting qualities as alternative rice breeding targets.

The costs of producing beer (i.e., 10 hL batch of a 5% ABV beer) with rice malt and barley malt were then estimated to assess the impact on brewers who choose to implement this material (Table 4). The brewing cost of all-malt beers (Table 4) followed the order of price per extract (Table 3). BM produced the most affordable all-malt beer ($162), while rice malts were approximately 30% more expensive. HLR obtained the highest production cost among the rice varieties tested ($198). However, rice malt could also be used like milled rice as a supplemental source of starch. It was estimated that when using 40% rice malt in a grist bill in comparison to using milled rice the production cost decreased by 1.5–16%. This was largely related to cutting brewing aids (e.g., rice hulls, enzyme, FAN, boiling) which are needed when using milled rice.

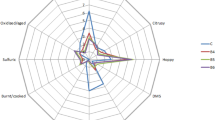

Finally, the land usage needed to produce the equivalent extract from rice malt and barley malt was evaluated to investigate the acreage needed to supply the malting and brewing industries (Fig. 2). Interestingly, paddy rice field yield exceeded malting barley (Fig. 2A) and compensates for rice’s lower extract and higher malting losses. What this means is that rice yields roughly 1.9 to 2.8 times more extract per hectare than barley (Fig. 2B) and that significantly less acreage would be needed to supply the equivalent amount of extract as malt (Fig. 2C), and LGR would require 66% of the current acreage to supply the same amount of extract as barley does with 85% (Fig. 2D). The higher yield of extract per hectare would provide a reduction of 50–67% of land usage for the same amount of extract.

Agronomic yield (A) and yield per extract (B) of barley and rice.Equivalent harvested area (C) and percentage of rice and barley harvested area required to supply the same amount of extract (fermentable sugars) from the current production of barley malt from the malting industry (D). It was considered a malt production of 2.38 mi t and all extract from barley malt being provided from either malting barley (USA, red), pureline long grain rice (AR, black), hybrid long grain rice (AR, green), pureline medium grain (AR, blue), average long grain rice (AR, gray line; USA, dashed gray) and medium (AR, purple line; USA dashed purple), or milled rice (AR, dotted black). Results are from supplementary equations (SE) 49–51 in Supplementary Information. Figures were generated using Microsoft Office 365 (Excel and Powerpoint).

Discussion

Barley is grown throughout the world (Fig. 1A); however, most of the world’s production is used for feed with only 13–25%5,38 meeting the requirements to be processed into malt. Due to the need for temperate climate conditions, malting barley is mostly grown in the European Union, Russia, North America, and Australia. Most tropical and subtropical countries (e.g., Brazil, Mexico, and African countries) need to import barley malt to produce beer (Fig. 1D).

Based on caloric intake rice is the single most important cereal in the world39,40. Due to this rice is produced in almost every country and the field yield is two times more than barley. This means that half of the land is needed to produce the same amount of grain/extract. To put this in perspective, if the brewing and malting industry switched to 100% rice, 114% of the current long grain rice acreage in Arkansas (i.e., a 14% increase) or 66% of the total USA LGR current acreage would account for the total malting barley acreage (Fig. 2D). This illustrates the capacity of long grain rice agriculture to match/ absorb the current extract demand from barley malt production with limited inputs. Hybrid and pureline acreage in Arkansas could also be contracted/ increased to meet barley malt demand as rice cultivars are identified with high malting quality (with increases of 57% or 123% in current acreage needed to meet 100% barley demand respectively). The demand for food and other materials will continue to increase as the population is projected to reach 10 billion in 206441. This will intensify land usage debates and drive deforestation to expand agricultural areas. Being able to grow more extract on less land will be extremely advantageous. Future studies should focus on rice breeding to reduce methane emissions, rice cultivation methods that require less water (e.g., furrow irrigated or alternate wet and drying), agricultural practices (e.g., straw management, soil management), and could increase yields to accommodate this change in agriculture. Also, like what is currently done with barley, new rice varieties can be bred to improve malting qualities (i.e., higher extract) and this could further decrease the required production area.

As shown, the main factors which influence malting production costs are raw material and utility costs. As seen the raw material costs contribute a significant part of the malting costs in the craft level ( ~ 40%), LGR and barley had a more stable price per ton over the course of this study than MGR (Table 1 & S3), shown by the half the standard deviation. Regional factors (such as climate, energy costs, etc.) have a direct influence on production costs. In Jonesboro, the estimated costs for heating rice during colder months were greater as higher temperatures are needed for germination (Table 2). However, in warmer climates, higher ambient temperatures may impart lower heating costs for rice and may be offset by the costs needed to cool barley during germination, as well as potentially lower rice prices compared to barley. The analysis tool provided in the Supplementary Data can be utilized to simulate these findings under a variety of conditions. It is worth mentioning that this study was modeled based on a craft malthouse with SG&K equipment in the USA and using local prices for raw materials. Results are expected to differ from location to location, malthouse size, and/or system (e.g., floor malting). Further studies are needed to optimize malting conditions for specific rice varieties (e.g., steep water reutilization, germination times, use of gibberellic acid, required final moisture, etc.) and could reduce malt losses as well as increase throughput and production. Increased throughput would lower the fixed costs per batch (machinery and labor), which is the highest discrepancy between rice and barley. Overall, simulations showed that the final cost of rice malt would be ~17% higher than barley malt (Table 3). Notably, in 3% of the simulations the price of rice malt and barley malt were equivalent. The cost of rice malt could be further optimized using breeding through the identification genetic traits leading to higher extract. However, when considering gluten-free (GF) malt alternatives, rice malt is extremely competitive. GF malts are often several times more expensive than barley malt42. Generally, to be considered competitive in cost GF malts should not be more than ~2x in cost than traditional malting barley43. GF beers are experiencing rapid growth, with annual revenue increasing by over 16%44. GF beers provide a chance for people who follow GF diet to consume beer and/or non-alcoholic beer45. To ensure safety and prevent cross-contamination, the use of dedicated GF malts, malthouses, and breweries is essential. All-malt rice beers could be produced to offer GF beer and GF non-alcoholic beers at a lower price compared to traditional GF alternatives, while additionally eliminating flavor defects17. The costs of all-rice malt beers were on average ~30% higher than barley with cost overlap occurring in 15% of the simulations. Although an increase of 30% is significant, the use of rice offers future security and competitiveness for maltsters and brewers. This is because lower fluctuations in price have been traditionally observed for rice (Table 1), rice requires less land to grow the same amount of extract (Fig. 2D), and rice could help to avoid sudden changes in price due to tariffs/import taxes or climatic events. For instance, a tariff over malting barley producing countries (e.g., Canada, Russia, or Australia) and/or a decrease in barley production and/or quality, could increase barley prices and amplify the number of simulations in which rice is competitive. Based on these results and looking forward to a global economy which is more constrained in trade and facing a hotter climate, rice is poised to increase its competitiveness with barley.

The addition of adjuncts/ supplemental sources of fermentable extract such as milled rice and corn is a strategy typically employed by larger breweries to achieve desired flavor profiles and manage costs. This strategy is not commonly employed by craft breweries due to the lack of equipment needed to boil the adjunct for gelatinization/ starch utilization. In 2022, the beer adjunct market was valued at over ~$55 billion, with unmalted rice representing 20%46. If brewers adapted rice malt instead of milled rice the simulated costs in brewing a 40%-adjunct beer would potentially decrease ~2–12% (Table 4). This decrease is because milled rice requires exogenous enzyme and rice hulls for mashing, and nitrogen supplementation47 for healthy fermentations, whereas rice malt would reduce some of these inputs since it is self-saccharifying, is hulled, and has protein/FAN level similar to barley18. The implications of this finding could be vast considering the environmental goals and millions of liters of beer produced by large multinational breweries48,49,50,51. Furthermore, without the need to pregelatinize, as rice malt is self-saccharifying, craft breweries could utilize this material in their facilities. However, to fully elucidate the potential of using rice malt in brewing, future research also needs to investigate the consumer acceptance of beer made with these novel products as well as to compare these products against the performance of current products on the market.

Numerous breweries are enacting sustainability initiatives with goals to reduce their emissions between 30% and 50%48,49,50,51. Raw material procurement and transportation account for ~40% of the greenhouse gases in the brewing process. Rice has a higher global warming potential (GWP) than barley, ranging from 0.23 to 5.55 t CO2e/t grain (CO2-equivalent, CO2e) (Table 1)52,53,54,55,56,57,58, compared to barley’s 0.26–0.57 t CO2e/t grain52,59,60,61,62. The GWP for rice has a relatively wide range due to the variety grown63, location, soil, production method (e.g., flooded, alternate wet and drying, or furrow irrigated), and agricultural practices (e.g., straw management, application of inhibitor of fumarate reductase and/or ethanol). One of the main reasons for the high GWP of rice is methane emissions53,58. Generally, rice is cultivated under flooded conditions, which allows for anaerobic methanogenic microbes to produce methane, which sharply increases CO2e40. Methane emissions can then be mitigated by choosing varieties that have low fumarate secretion and high ethanol secretion and/or applying fumarate reductase inhibitors and ethanol can lower methane emissions by up to 70% during growing season63. Increase in rice yield also decreases GWP by 38–55%40. Post-harvest agricultural practices like rice straw management and keeping the soil dry during off season are also vital to avoid decomposition of organic material and can reduce rice GWP by up to 41%40,64,65. Overall, if rice agriculture continues to make improvements, rice malt could provide locally sourced raw material for countries reliant on barley importation, reducing transportation inputs, and helping breweries to achieve their sustainability goals. However, only a life cycle analysis could evaluate to the full extent of this transition which is outside the scope of the study.

In conclusion, rice emerges as a valuable alternative, as climate challenges continue to threaten traditional barley-growing regions. The use of rice malt would not only help meet the USA malting demands but would also provide the opportunity for countries that have little or no malting barley production to produce malt with locally grown crops. Rice is globally available and using local materials minimizes costs and CO2 emissions related to shipping overseas, import taxes, and risks from currency and market fluctuations. These aspects may ultimately provide a sustainable solution, mitigate risks, and ensure stable production for the brewing industry. The shift could position rice as a malting grain for brewing, especially for breweries interested in sustainable alternatives and efficient land use. Additionally, this manuscript provides an analytical tool (Supplementary Data) to help assess the economic viability of alternative grains by conducting similar analyses, opening opportunities to diversify and shield the malting industry.

Methods

Data collection

This study used publicly available yearly agronomical data (yield, harvest area, and production) between 2013 and 2023 for barley, long grain rice, and medium grain rice in Arkansas and in the United States (or USA excluding California for medium grain rice) from the USDA (Table 1 and Table S1 in Supplementary Information)6, along with yield for hybrid or pureline long and medium grain rice from the Arkansas Rice Cultivar Testing36 (Supplementary Data – RD Grain Agri Data) between 2013 and 2023. Monthly received prices for malting barley, rough long grain rice, and medium grain rice (Supplementary Data – RD Grain Prices), as well as weekly price for milled rice (brewers’ rice, second heads, and head rice) for 2022 and 2023 were obtained from the USDA6,66 and price values were adjusted to 2024 by inflation using yearly averages (Tables S3, S4, and Supplementary Data – RD Milled rice prices)67. Extract values from barley cultivars were obtained from the American Malting Barley Association68, barley malting loss from Yin3; rice extract and malting losses from Guimaraes et al.18 (Table S5 and Supplementary Data – Malting Parameters) and malt house model from Paul37 for estimating malting costs (Supplementary Data: Malt Cost – Barley – SGK, Malt Cost – Rice – SGK, Malt Cost – Barley – Process, and Malt Cost – Rice – Process). The location for this model was Jonesboro, Arkansas, USA, and used monthly data for electricity prices69, natural gas70, and water costs from City Water & Light Jonesboro (Supplementary Data – RD Utilities)71; and daily temperature from the U.S. Climate Data72 (Supplementary Data – RD Temperature). Conversion factors were presented in Table S6.

Malting costs

Monte Carlo Simulations (MCS) were performed using the Excel add-in tool @Risk (Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA) and statistical analyzes used Excel 365 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and the simulation results are in Supplementary Data – Data. Daily temperatures and milled rice extract were considered triangular distribution between the minimum value and the maximum value, other parameters followed a normal distribution. The supplementary equations (SE) 1-33 & SE54–62 were used for malting cost calculations are in the Supplementary Information. Barley and rice moisture after harvest were considered 12% and 15%, respectively, and malt final moisture was 4% for both cereals3,36. It was assumed that furnace efficiency and heat recovery of the malt house were 75% and 125%, respectively37. The average of each malting parameter (Table S2) and utilities (Table S7) used in the simulations. The results of the simulations were separated into steeping (Table S8) where the grain is hydrated; germination (Table S9); kilning (Table S10); and other operational costs, labor & non-operational costs, and total malting costs (Table S11). The major results from each step were shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Data – Malt Cost – Barley SGK, Malt Cost – Rice SGK, Malt Cost – Barley Process, Malt Cost – Rice Process, and Malting Costs.

Cost per extract

Cost per extract is the cost per unit of extract in the beer. Extract is a major variable in brewing as extract has a strong influence on the amount of raw material used and the alcoholic strength of the final beverage. Cost per extract was calculated based on the price per ton of cereal, the extract in its malted or milled form, and malting loss if applicable (Table 3) using SE 34–36. The results were shown in Supplementary Data – Pricing.

Brewing costs

As malt is normally used in the brewing industry, the cost to make 5% alcohol by volume (ABV) was estimated using 100% malt for all-malt beers as well as 60% barley malt and 40% adjuncts (e.g., rice malt or milled rice). The assumptions taken for this calculation were that a 10 hL (1000 L) of a 12 oP wort would be produced, enough for a 5% ABV, and brewhouse efficiency (i.e., capacity of the brewing process to extracts available fermentable sugars) was 90%. The values were chosen as they represent common lager beer (American adjunct lager style) production, like most mainstream brands. The volume of water; mashing regime, brewing aids (if applicable), hops, etc. were considered constant for all trials as they are recipe-dependent and are not standardized in any way. For the scope of this study, the cost of malting and brewing aids (enzymes, rice hulls, FAN, and boiling) were included for analysis. The equations to calculate the amount and costs of malt needed to brew beer (SE 37 & 38) takes into consideration the brewhouse efficiency, density of the wort, and final volume, as well as moisture (4% for malt, 12% for milled rice), extract of the grain used, and the percentage of that grain to the grist (all-mats brews were 100% barley malt or rice malt, adjunct brews were 60% barley malt, 40% rice malt or milled rice as adjunct) (SE 39-48). The parameters used for 100% malt were presented in Table S12 and the results and calculations are in Tables 4 and S13, and Supplementary Data – Brewing costs; and the parameters and results of 40% adjunct are presented in Tables S14 and S12, respectively.

Agronomic impacts

Finally, to evaluate the impact of using this novel malt from an agronomical perspective, the yield of extract in the field was calculated and the area necessary to supply the demand of extract from malt for each grain. The yield of extract in the field is the amount of extract that can be produced per hectare of land. The yield of extract was calculated according to SE 49 using multiple parameters (Tables 1, 3, S1, and S15) and results were shown in Fig. 2, Table S16 using SE 65, and Supplementary Data – Agronomic impacts. The equivalent harvest area to produce extract from malt was calculated according to SE 50 & 51 and is the amount of land required to produce the same extract as is produced from barley malt by the malting industry. For this, the malt production was considered to be 2.38 million tons35 per year, and yields, moisture contents, malting losses and milling loss were taken into account (Tables 1, 2, and S2, and Supplementary Data – Agronomic impacts and malt production).

Data Availability

All data used for analysis in current study are provided in the supplemental information and data files.

References

Xie, W. et al. Decreases in global beer supply due to extreme drought and heat. Nat. Plants 4, 964–973 (2018).

Ramanan, M., Nelsen, T., Lundy, M., Fox, G. P. & Diepenbrock, C. Effects of genotype and environment on productivity and quality in Californian malting barley. Agron. J. 115, 2544–2557 (2023).

Yin, X. S. Malt: Practical Brewing Science (American Society of Brewing Chemists, 2021).

Tableau Public. Commodity Costs and Return: Crops. https://public.tableau.com/views/U_S_CommodityCostsandReturns/CommodityCostsandReturns?:showVizHome=no (2024).

Izydorczyk, M. S. & Edney, M. Cereal Grains Ch. 9 (Woodhead Publishing, 2017).

United States Department of Agriculture – National Agricultural Statistics Service. QuickStats. https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/ (2025).

Morrissy, C. P. et al. Continued Exploration of Barley Genotype Contribution to Base Malt and Beer Flavor Through the Evaluation of Lines Sharing Maris Otter® Parentage. Journal of the Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 80, 201–214 (2022).

Looseley, M. E. et al. Association mapping of malting quality traits in UK spring and winter barley cultivar collections. Theor. Appl. Genet. 133, 2567–2582 (2020).

Del Pozo-Insfran, D, Hernandez-Brenes, D, Urias-Lugo, D, Hernandez-Brenes, C & Saldivar, S. O. S. Effect of Amyloglucosidase on Wort Composition and Fermentable Carbohydrate Depletion in Sorghum Lager Beers. J. Inst. Brew. 110, 124–132 (2004).

Flores-Calderón, A. M. D., Luna, H., Escalona-Buendía, H. B. & Verde-Calvo, J. R. Chemical characterization and antioxidant capacity in blue corn (Zea mays L.) malt beers. J. Inst. Brew. 123, 506–518 (2017).

Zarnkow, M. et al. The Use of Response Surface Methodology to Optimise Malting Conditions of Proso Millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) as a Raw Material for Gluten-Free Foods. J. Inst. Brew. 113, 280–292 (2007).

Marcus, A. & Fox, G. Malting and Wort Production Potential of the Novel Grain Kernza (Thinopyrum intermedium). Journal of the Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 81, 308–318 (2023).

Ceppi, E. L. M. & Brenna, O. V. Brewing with Rice Malt — A Gluten-free Alternative. J. Inst. Brew. 116, 275–279 (2010).

Mayer, H. et al. Development of an all rice malt beer: A gluten free alternative. LWT 67, 67–73 (2016).

Ceccaroni, D., Marconi, O., Sileoni, V., Wray, E. & Perretti, G. Rice malting optimization for the production of top-fermented gluten-free beer. J. Sci. Food Agric. 99, 2726–2734 (2019).

Ceccaroni, D. et al. Specialty rice malt optimization and improvement of rice malt beer aspect and aroma. LWT 99, 299–305 (2019).

Moirangthem, K., Jenkins, D., Ramakrishna, P., Rajkumari, R. & Cook, D. Indian black rice: A brewing raw material with novel functionality. J. Inst. Brew. 126, 35–45 (2020).

Guimaraes, B. P. et al. Investigating the Malting Suitability and Brewing Quality of Different Rice Cultivars. Beverages 10, 16 (2024).

Mayer, H., Marconi, O., Regnicoli, G. F., Perretti, G. & Fantozzi, P. Production of a Saccharifying Rice Malt for Brewing Using Different Rice Varieties and Malting Parameters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 5369–5377 (2014).

Kunze, W. Technology Brewing & Malting. (Versuchs- u. Lehranstalt f. Brauerei, 2019).

Brissart, R., Malting Technology (Carl, 2000).

Bogdan, P. & Kordialik-Bogacka, E. Alternatives to malt in brewing. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 65, 1–9 (2017).

Tuhanioglu, A., Lafontaine, S. & Ubeyitogullari, A. Enhancing the aroma of white whole sorghum flour using supercritical carbon dioxide. Future Foods 8, 100253 (2023).

Mitchell, C. R. Starch Ch. 13 (Academic Press, 2009).

Nalley, L. et al. The Production, Consumption, and Environmental Impacts of Rice Hybridization in the United States. Agron. J. 109, 193–203 (2017).

Challinor, A. J. et al. A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 287–291 (2014).

Zhao, C. et al. Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9326–9331 (2017).

Marconi, O., Sileoni, V., Ceccaroni, D. & Perretti, G. The Use of Rice in Brewing (InTech, 2017).

Saikrishna, A., Dutta, S., Subramanian, V., Moses, J. A. & Anandharamakrishnan, C. Ageing of rice: A review. J. Cereal Sci. 81, 161–170 (2018).

Schubert, C. et al. The Role of Adjunct Milled Rice, Barley Malt, and different Koji Variations in Alcoholic and Non-Alcoholic Beer Production. Brew. Sci. 77, 107–117 (2024).

Siegrist, M. & Hartmann, C. Consumer acceptance of novel food technologies. Nature Food 1, 343–350 (2020).

The Observatory of Economic Complexity. The trade Data You Need, When You Need It. https://oec.world/en (2024).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT: Food and agriculture data. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (2024).

Agricultural Marketing Research Center. Barley Profile. https://www.agmrc.org/commodities-products/grains-oilseeds/barley-profile (2022).

Esslinger, H. M. Handbook of brewing: processes, technology, markets (Wiley-VCH, 2009).

Hardke, J., Sha, X. & Bateman, R. J. Arkansas Rice Research Studies 2023. https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wordpressua.uark.edu/dist/3/599/files/2024/08/705_BR_Wells_Arkansas_Rice_Research_Studies_2023.pdf (2024).

Paul, A. Craft Malting Technology: Key Considerations for Capital & Operational costs. in 2018 Craft Malt Conference https://craftmalting.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Craft-Malting-Technology-Key-Design-Considerations-for-Capital-Operational-Costs-Adam-Paul.pdf (2018).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Barley, Malt, Beer in Agribusiness handbook (FAO, 2009). https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/tci/docs/AH3_BarleyMaltBeer.pdf

Bin Rahman, A. N. M. R. & Zhang, J. Trends in rice research: 2030 and beyond. Food Energy Secur 12, e390 (2023).

Qian, H. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation in rice agriculture. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 716–732 (2023).

Vollset, S. E. et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 396, 1285–1306 (2020).

Cela, N. et al. Gluten-Free Brewing: Issues and Perspectives. Fermentation 6, 53 (2020).

Craft Maltsters Guild. Malting & brewing gluten-free grains https://craftmalting.com/video/webinar-malting-brewing-gluten-free-grains/ (2017).

Statista. Worldwide gluten-free beer market value in 2017, with a forecast for 2018 to 2025. https://www-statista-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/statistics/1239711/global-gluten-free-beer-market-size-forecast/ (2021).

Yang, D. & Gao, X. Progress of the use of alternatives to malt in the production of gluten-free beer. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 2820–2835 (2022).

S&S Insider. Beer Adjuncts Market Size, Share & Segmentation by Type (Unmalted Grain, Potatoes, sugar, cassava, and other), by form (Liquid, Dry), by Regions and Global Forecast 2023-2030 https://www.snsinsider.com/reports/beer-adjuncts-market-4047 (2023).

Dlamini, B. C., Taylor, J. R. N. & Buys, E. M. Influence of ammonia and lysine supplementation on yeast growth and fermentation with respect to gluten-free type brewing using unmalted sorghum grain. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 55, 841–850 (2020).

Diageo. Accelerating to a low carbon world: Our net-zero carbon strategy. https://www.diageo.com/~/media/Files/D/Diageo-V2/Diageo-Corp/esg/sustainability/carbon/accelerate-to-a-low-carbon-world-our-net-zero-carbon-strategy-october-2022.pdf (2024).

Duvel M. Brewing for Tomorrow: Sustainability report 2023. https://www.duvelmoortgat.com/uploads/images/Duvel-Moortgat-Sustainability-report-2023.pdf (2023).

Kirin Holdings Co., L. Environmental Report 2024. https://sustainabilityreports.com/reports/kirin-holdings-co-ltd-2024-integrated-report-pdf/ (2024).

Sapporo Holdings Ltd. Sapporo Holdings Integrated Report 2023. https://www.sapporoholdings.jp/en/ir/library/factbook/ (2024).

CarbonCloud. Food supply chain emissions - in one platform. https://carboncloud.com/ (2024).

Nalley, L., Popp, M. & Fortin, C. The Impact of Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Crop Agriculture: A Spatial-and Production-Level Analysis. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 40, 63–80 (2011).

Shin, K. et al. Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Emission Estimates Across Countries, Products, and Global Trade Routes. in 2024 Annual Meeting, Agricultural and Applied Economics Association https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/343962/files/29095.pdf (2024).

Nalley, L. L. et al. Comparative economic and environmental assessments of furrow- and flood-irrigated rice production systems. Agric. Water Manag. 274, 107964 (2022).

Fertitta-Roberts, C., Oikawa, P. Y. & Darrel Jenerette, G. Evaluating the GHG mitigation-potential of alternate wetting and drying in rice through life cycle assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 653, 1343–1353 (2019).

Nunes, F. A., Seferin, M., Maciel, V. G., Flôres, S. H. & Ayub, M. A. Z. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions from rice production systems in Brazil: A comparison between minimal tillage and organic farming. J. Clean. Prod. 139, 799–809 (2016).

Coltro, L., Marton, L. F. M., Pilecco, F. P., Pilecco, A. C. & Mattei, L. F. Environmental profile of rice production in Southern Brazil: A comparison between irrigated and subsurface drip irrigated cropping systems. J. Clean. Prod. 153, 491–505 (2017).

Rajaniemi, M., Mikkola, H. & Ahokas, J. Greenhouse gas emissions from oats, barley, wheat and rye production. Agron. Res. 9, 189–195 (2011).

Tricase, C., Lamonaca, E., Ingrao, C., Bacenetti, J. & Lo Giudice, A. A comparative Life Cycle Assessment between organic and conventional barley cultivation for sustainable agriculture pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 3747–3759 (2018).

Tidåker, P. et al. Estimating the environmental footprint of barley with improved nitrogen uptake efficiency—a Swedish scenario study. Eur. J. Agron. 80, 45–54 (2016).

Niero, M. et al. Eco-efficient production of spring barley in a changed climate: A Life Cycle Assessment including primary data from future climate scenarios. Agric. Syst. 136, 46–60 (2015).

Jin, Y. et al. Reducing methane emissions by developing low-fumarate high-ethanol eco-friendly rice. Molecular Plant 18, 333–349 (2025).

Pathak, H. & Wassmann, R. Introducing greenhouse gas mitigation as a development objective in rice-based agriculture: I. Generation of technical coefficients. Agric. Syst. 94, 807–825 (2007).

Smith, P. et al. Greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 789–813 (2008).

United States Department of Agriculture – Agricultural Marketing Service. Weekly National Rice Summary. https://www.ams.usda.gov/market-news/national-grain-reports (2024).

CoinNews. Current US Inflation Rates: 2000-2024. https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/current-inflation-rates/ (2024).

American Malting Barley Association. Recommended Varieties. https://ambainc.org/recommended-varieties.php (2024).

FindEnergy. Craighead County, Arkansas Electricity Rates & Statistics. https://findenergy.com/ar/craighead-county-electricity/ (2024).

U.S. Energy Information Administration. Natural gas. https://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/hist/n3035ar3m.htm (2024).

CWL. Commercial/Industrial Information. https://jonesborocwl.org/services-offered/commercial-industrial-services (2024).

U.S. Climate Data. Weather Alerts: Daily normals Jonesboro - Arkansas. https://www.usclimatedata.com/climate/jonesboro/arkansas/united-states/usar0304#google_vignette (2024).

Acharya, P., Ghimire, R., Paye, W. S., Ganguli, A. C. & DelGrosso, S. J. Net greenhouse gas balance with cover crops in semi-arid irrigated cropping systems. Sci. Rep. 12, 12386 (2022).

The Land Institute. Annual Kernza® perennial grain: supply report. https://kernza.org/wp-content/uploads/2023-Kernza-Supply-Report.pdf (2023).

Sustain-A-Grain. Kernza® Perennial Whole Grain. https://www.sustainagrain.com/store/p/dehulled-kernza-perennial-grain-50-lbs (2025).

Tautges, N., Detjens, A. & Jungers, J. Kernza® Grower Guide. https://cropsandsoils.extension.wisc.edu/files/2023/08/Grower-guide_final.pdf (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Foundational Knowledge of Plant Products program, project award no. 13960138, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bernardo P. Guimaraes: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Lawton L. Nalley: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review. Scott R. Lafontaine: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guimaraes, B.P., Nalley, L.L. & Lafontaine, S.R. Evaluating the costs of alternative malting grains for market adaptation: a case study on rice malt production in the U.S. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 19 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00060-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00060-6