Abstract

Land subsidence is a slow-moving hazard with adverse environmental and socioeconomic consequences worldwide. While often considered solely a coastal hazard due to relative sea-level rise, subsidence also threatens inland urban areas, causing increased flood risks, structural damage and transportation disruptions. However, spatially dense subsidence rates that capture granular variations at high spatial density are often lacking, hindering assessment of associated infrastructure risks. Here we use space geodetic measurements from 2015 to 2021 to create high-resolution maps of subsidence rates for the 28 most populous US cities. We estimate that at least 20% of the urban area is sinking in all cities, mainly due to groundwater extraction, affecting ~34 million people. Additionally, more than 29,000 buildings are located in high and very high damage risk areas, indicating a greater likelihood of infrastructure damage. These datasets and information are crucial for developing ad hoc policies to adapt urban centers to these complex environmental challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The slow and gradual sinking of Earth’s surface—land subsidence—is a present and growing hazard with costly environmental, social and economic impacts on urban centers1,2,3,4. Globally, the narrative of sinking cities has drawn widespread attention to rapidly sinking coastal areas, such as Jakarta, Bangkok, Venice and New Orleans1,5,6,7. However, beyond these vulnerable coastal cities, a broader spectrum of major cities worldwide, including inland metropolises such as Mexico City, Beijing and Tehran, are experiencing major subsidence at rates that necessitate immediate attention due to their potential impacts on infrastructure8,9,10,11. Even modest rates of urban subsidence can profoundly impact the structural integrity of buildings, roads, bridges and dams12. Over time, these incremental changes may accumulate, magnifying vulnerabilities within urban systems, notably exacerbating existing flood risks with impacts on urban livability3,13,14. Moreover, the anthropogenic drivers of subsidence, including groundwater extraction and the loading effect of urban development15,16, are likely to intensify as cities continue to grow and climate change exacerbates environmental stresses. The compounding effect of climate change and urban population and socioeconomic growth emerges as a critical concern, potentially accelerating subsidence rates and transforming previously stable urban areas into vulnerable zones1,17,18. Specifically, climate-induced droughts and the increasing demand for freshwater resources are likely to exacerbate the risk of subsidence, projecting a future where an increasing number of cities may face major challenges in subsidence management.

Historically, land subsidence in the United States has been documented to affect more than 17,000 square miles in 45 states19. A systematic literature review identifies documented cases in more than 50 cities nationwide (Supplementary Table 1). Notable subsiding regions and cities across the United States include the Houston–Galveston area in Texas14; Phoenix in Arizona20; the Las Vegas Valley in Nevada21; the Mississippi Delta in Louisiana22; major cities on the East Coast of the United States, such as Hampton Roads in Virginia and Charleston in South Carolina12; and Alaska19. In the Houston–Galveston area, long-term groundwater mining and oil and gas extraction have resulted in subsidence rates of up to 2 inches (5 cm) per year in certain areas. Similarly, the Phoenix metropolitan area and Las Vegas Valley have recorded yearly subsidence rates of up to 3.5 inches (9 cm). The Mississippi Delta is experiencing subsidence rates greater than 1 cm per year, exacerbated by reduced sediment deposition due to levees and dams. Glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA) and anthropogenic activities on the US East Coast are causing subsidence at variable rates, reaching up to 5 mm per year in some cities. In Alaska, permafrost thawing has induced subsidence at variable rates, with some areas experiencing changes of up to 0.4 inches (1 cm) per year.

The widespread, geographically diverse and multifactorial nature of subsidence in the United States presents challenges for infrastructure resilience, urban planning and environmental management, necessitating the monitoring of spatiotemporal patterns and rates of land elevation changes. In situ point-based observations, such as global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) and leveling, provide accurate measurements of subsidence extent and rates but have limited spatial resolution2,7. Recent studies employing statistical models and machine learning have provided insights into the spatial extent of land subsidence in the United States and globally23,24. However, these models often lack the spatial resolution necessary to capture localized, fine-scale land motion variations, which are crucial for assessing urban vulnerabilities3. These challenges and the resulting lack of detailed high-resolution data may impede the implementation of targeted subsidence mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Satellite-based observations via interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) overcome these challenges and can be assimilated in global models and complement point observation datasets. This study systematically observes land elevation changes across the 28 most populous US cities. Our analysis leverages Sentinel-1 SAR datasets at ~28-m resolution and mm-level precision to address the need for high-resolution and accurate subsidence monitoring. Collectively, the population of these cities constitutes about 12% of the total US population and includes all US metropolises with populations exceeding 600,000 people (Supplementary Table 2). Using the dataset of land elevation changes, we evaluate the hazards associated with differential settlement and assess the associated risks to infrastructure across these cities. The implications of these analyses are manifold: from the immediate need for infrastructural adaptation to promote sustainable urban development in the face of escalating environmental pressures to the long-term imperatives of groundwater management.

Subsidence hotspots and spatial variability in US cities

We estimate the spatial pattern of land subsidence in 28 urban cities across the United States using advanced multitemporal SAR interferometric analysis of Sentinel-1 A/B C-band satellites (Methods). The SAR datasets include 3,500 acquisitions obtained in ascending orbit between 2015 and 2021. Using these datasets, we generate a spatial map (resolution of ~28 m) of the temporal deformation of the ground in the line-of-sight (LOS) of the satellite. Assuming a uniform horizontal deformation, we fit and remove a plane from the LOS displacements. Next, we projected the corrected LOS velocity measurements in the vertical direction to obtain vertical displacement (that is, subsidence or uplift). The vertical velocities for each city are referenced to the IGS14 global reference frame, ensuring consistency with global vertical land motion (VLM) standards (Methods).

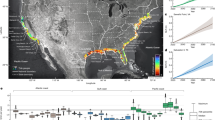

On average, 25 out of the 28 US cities are experiencing sinking (negative VLM) at varying rates (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Figs. 1–3 and Supplementary Table 2). Specifically, in nine of the 25 sinking cities (New York, Chicago, Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, Columbus, Seattle and Denver), we find area-weighted average subsidence (calculated by weighting subsidence rates by the spatial extent of sinking areas; Methods) greater than 2 mm per year. Several cities in Texas—the fastest-growing state in the United States—including Houston, Fort Worth and Dallas, exhibit the highest measured subsidence rates among all cities, with average subsidence rates exceeding 4 mm per year. However, it is essential to highlight that vertical land deformation often varies spatially within cities, and subsidence (or uplift) hotspots can be found in cities experiencing overall average uplift (or subsidence) (Fig. 1b,f and Extended Data Figs. 1j,l and 3d). From an urban risk perspective, the cities with the greatest spatial variability may experience the greatest hazard to urban infrastructure, as discussed in the later section.

a, The average rate of VLM for 28 US cities as evaluated in this study. Each circle is color-coded to the respective average VLM for each city (Supplementary Table 2). b–f, Spatially varying VLM for New York, NY (b); Las Vegas, NV (c); Seattle, WA (d); Houston, TX (e) and Washington, DC (f). The location of each city is highlighted in a. Positive VLM (green–purple colors) indicates uplift, and negative VLM (yellow–orange–red colors) indicates subsidence. LGA, LaGuardia Airport, NY. Individual VLM maps for all 28 cities are shown in Extended Data Figs. 1–3. National and state boundaries in a are based on public domain vector data by World DataBank (https://data.worldbank.org/) generated in MATLAB. Background images in b–f from streets-dark ESRI, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

In every city, at least 20% of the area is sinking (that is, VLM < 0), and in 25 out of the 28 cities, at least 65% is sinking (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 3). We estimate that a total land area of 17,900 km2 is sinking across these 28 US cities (Fig. 2b). The cities with the most widespread subsidence in the United States, with about 98% of the cities’ area affected include Chicago, Dallas, Columbus, Detroit, Fort Worth, Denver, New York, Indianapolis, Houston and Charlotte (Fig. 2a). In five cities—New York, Chicago, Houston, Dallas and Fort Worth—at least 10% of the city area is sinking at a rate exceeding 3 mm per year (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 3). Among these, Dallas, Fort Worth and Houston exhibit the highest proportion of sinking areas, with over 70% of their land area experiencing subsidence at this rate. Houston—the fastest-sinking city out of the 28 most populated US cities—has 42% of its land area subsiding faster than 5 mm per year and 12% subsiding faster than 10 mm per year (Supplementary Table 3). While not accounting for a major share of the city area, most cities have localized zones where the land is sinking faster than 5 mm per year (Fig. 2a). For example, notable subsidence greater than 5 mm per year is observed in several areas in LaGuardia Airport, New York (Fig. 1b); Northgate and Los Prados, Las Vegas (Fig. 1c); East Potomac Park, Washington, DC (Fig. 1f); northern part of Treasure Island and areas adjacent to Islais Creek, San Francisco (Extended Data Fig. 2e); and Long Beach, Los Angeles (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

a, The percentage of each city affected by subsidence. The warming of the colors from yellow (subsidence > 0 mm per year) to red (subsidence > 1 cm per year) is indicative of increasing subsidence. b, The total subsiding area (blue bars) and subsiding population (green bars) for each city. Supplementary Table 3 summarizes the proportion of each city affected by each subsidence level and the affected area and population.

To estimate the population exposed to urban subsidence, we utilized the 2020 US census data for each city. Our estimates show that about 33.8 million people (greater than the current population of Texas: ~30 million) or 10% of the total US population currently reside on sinking land across the 28 US cities (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 3). In addition, 4.7 million (including residents of New York; Los Angeles; Houston; Dallas; Washington, DC; Columbus and so on) and 1.1 million (including residents of Houston, Los Angeles, Fort Worth, Las Vegas and Dallas) people are exposed to subsidence greater than 3 and 5 mm per year across US cities, respectively (Fig. 2b). Eight cities (New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Houston, Philadelphia, San Antonio and Dallas) account for over 60% of the total subsiding population, with the population exposed to subsidence exceeding 1 million people in each city (Supplementary Table 3). New York City alone accounts for 26% of the total subsiding population, with the other seven cities making up 5–8% of the population residing on subsiding land (Supplementary Table 3). Notably, these eight cities with subsidence exceeding 3 mm per year have experienced more than 90 flood events since 2000 (ref. 25), and ongoing land subsidence may exacerbate the flood hazards, particularly due to the expected climate-change-induced increases in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events3,26,27.

Fingerprints of urban subsidence

Both natural and anthropogenic-driven processes at various scales contribute to land subsidence in urban cities across the United States19. In cities such as New York; Philadelphia; Washington, DC; Denver; Indianapolis; Columbus; Detroit; Nashville; Chicago and Portland, contemporary rates of GIA are a dominant factor driving regional land elevation loss, which can vary from 1 to 3 mm per year (refs. 3,12,28,29; Extended Data Fig. 4). Regional variability in the VLM observed in cities along the western coast of the United States, such as Seattle, Portland and San Francisco, may be influenced by tectonic activities associated with the active plate margins and/or sediment compaction30. Whereas natural processes influence urban land subsidence in the United States, most of the sinking land results from human-driven activities, with 80% of the subsidence associated with groundwater withdrawals19. This extraction–subsidence relationship is based on the principle of effective stress (total stress minus pore-fluid pressure)31. When groundwater is pumped from an aquifer, the pore-fluid pressure decreases, leading to a decline in the hydraulic head, reflected by lower water levels in groundwater wells. This decrease in pore-fluid pressure increases the effective stress (for constant total stress), causing compaction of susceptible aquifer systems (for example, fine-grained material) that leads to land subsidence at the surface2,31,32.

To assess the impact of groundwater extraction on urban subsidence across the 28 US cities, we obtained a county-level dataset of estimated groundwater withdrawals from principal aquifers (Methods). Comparisons of the average VLM for 32 counties hosting these cities showed no significant linear correlation between groundwater withdrawal rates and surface elevation changes at a regional scale (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, this lack of correlation does not necessarily preclude a relationship but rather highlights the complexity of subsidence mechanisms. Aquifer properties, including volume, connectivity, diffusivity and spatial extent, probably influence the response of land surface elevation to groundwater extraction. Consequently, the effects of anthropogenic processes (that is, groundwater withdrawal) on subsidence may be highly localized, varying based on hydrogeological conditions and heterogeneous withdrawal patterns. To better understand the local context, we obtained the time series of groundwater data across 13 cities (representing ~46% of the 28 cities) from the US Geological Survey (Methods) and estimated the depth to groundwater-level trends for 90 wells (27 confined aquifers, 42 unconfined aquifers and 21 unknown aquifers) using Theil–Sen regression (Methods). The trends show groundwater-level decline in 24%, 53% and 47% of the confined, unconfined and unknown aquifer systems, respectively, at rates between 0.01 and 3.4 m per year. Some wells also showed increased groundwater levels at an average rate of 0.2 ± 0.3 m per year, suggesting variability in groundwater trends across the different aquifer systems. Note that the groundwater trends are estimated for the period of the VLM data (2015–2021) and may not reflect the long-term trends in groundwater levels across the United States33.

To investigate the impact of localized groundwater-level changes on VLM, we compared the groundwater-level rates with the average non-GIA VLM rates from InSAR pixels within a 50-m radius of the well locations. The analysis shows narrow variances and a poor correlation for unknown (ρ = 0.13) and unconfined (ρ = 0.43) aquifers (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 5). In contrast, we observe a strong correlation of 0.87 between the vertical deformation and changes in the groundwater levels within the confined aquifer systems (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 5). This linear relationship (R2 = 76%) suggests that 76% of the observed variation in non-GIA subsidence (or uplift rates) across the cities are associated with changes in groundwater levels within the confined aquifers (Fig. 3a). Also, a decrease (or an increase) in the groundwater levels drives corresponding subsidence (or uplift) in the land above the wells. However, we acknowledge the following caveats: (1) because of the variability in aquifer characteristics across different cities, broad estimates using a single slope value are not feasible, (2) this interpretation does not extend to every location but is only valid within the spatially limited 13 cities explored, (3) we note the existence of some discrepancies between the trends in groundwater-level changes and the VLM rates. For example, in 24% (or 19%) of the confined aquifers in cities such as Memphis; Washington, DC; New York; Houston and San Diego, we note subsidence (or uplift) corresponding to a decline (or increase) in groundwater levels (Fig. 3a). However, 12 wells show subsidence despite increased groundwater levels, suggesting delayed compaction following a period of decline34.

a, Linear regression analysis of groundwater-level trends and VLM across 13 US cities. The blue, yellow and red lines are the regression lines for confined, unconfined and unknown aquifers, respectively. b, Correlation between time series of VLM and changes in groundwater levels for confined, unconfined and unknown aquifers. Each square represents a single well in the respective city. ND, wells with no data, where the wells are more than 50 m away from an InSAR pixel. c, Probability curves showing the likelihood of vertical displacement exceeding −1 mm (that is, displacement < −1 mm) in response to groundwater-level changes in confined aquifers across 5 US cities: New York; Washington, DC; Houston; Memphis and San Diego. Groundwater levels have been normalized across cities to account for variations in well depths. The dashed black vertical line represents the probability of exceeding −1 mm displacement at half the maximum groundwater decline observed in each city (P[VLM < −1|nGWL = −0.5], where nGWL refers to the normalized groundwater level). d, Comparison of groundwater level and InSAR displacement for wells in Houston, New York and San Diego. The location of the wells for each city is summarized in Supplementary Table 7.

Furthermore, we compared the temporal dynamics of groundwater levels and vertical deformation for the different well locations. Using lagged Pearson correlation coefficient (ρ) analysis, we found a higher correlation (ρ = 0.5 ± 0.2) between the time series of the VLM and groundwater-level changes in the confined aquifers (Fig. 3b,d). A t-test of significance at an alpha value of 0.01 also showed that the obtained correlation is statistically significant (p value = 0.00). However, we find a lower correlation for the unconfined aquifers (ρ = 0.2 ± 0.3) and the unknown aquifers (ρ = 0.1 ± 0.2) (Fig. 3b), which were statistically insignificant (p value = 0.02). The exception are some wells in San Diego that lie above the confined wells (Fig. 3b,d). Therefore, we suggest that changes in the pore pressure, and consequently the stress acting on the aquifer matrix, control the temporal dynamics of vertical deformation of confined aquifers and, in a few cases, the unconfined aquifers15,35,36.

To investigate the dependence of surface elevation changes on human-induced groundwater fluctuations, we modeled the subsidence–groundwater decline relationship using a copula framework (Methods). We applied five different copula functions (Gaussian, t, Clayton, Frank and Gumbel) to model the dependence structure in wells with the highest positive correlation in five cities with confined aquifer layers: New York; Washington, DC; Houston; Memphis and San Diego. Using the best-fitting copula function for each well, we calculated the conditional probability of cumulative displacement exceeding a threshold of −1 mm (that is, displacement < −1 mm) as a function of groundwater-level changes (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Figs. 2–6). The distinct shapes of the curves reflect differences in how groundwater use modulates VLM across the studied cities (Fig. 3c). All curves indicate a higher conditional probability (or likelihood) of subsidence when groundwater levels decline below the long-term mean. However, the sensitivity of subsidence to hydraulic changes varies across cities. The steeper probability curves for New York and San Diego, and their relatively higher probability for land subsidence under negative groundwater-level changes, reflects a greater dependence of subsidence on groundwater-level decline. In contrast, the gradual slope and relatively lower maximum amplitude for respective conditional probabilities in Washington, DC, and Houston indicates that land elevation in these cities is less sensitive to hydraulic changes within the confined layers. Furthermore, we find a moderate to high probability (>50%) for subsidence exceeding 1 mm in New York, Memphis and San Diego if groundwater levels decline to half the lowest measured levels (Fig. 3c). These differences may be influenced by local geological conditions (for example, aquifer structure, aquifer material properties) or human interventions (for example, historical extraction rates). For example, in San Diego’s high-permeability alluvial aquifer system (San Diego Formation), rapid pressure equilibration due to high hydraulic diffusivity leads to a faster deformation response of the land surface to groundwater depletion. In contrast, Washington, DC’s fractured Piedmont bedrock aquifer exhibits subdued subsidence responses due to low diffusivity, which slows pressure equilibration. Such geological heterogeneity, compounded by human factors such as historical extraction rates, explains why cities such as San Diego experience greater subsidence risks during groundwater decline compared to systems with slower hydraulic feedback. These results help us to identify the fingerprint of anthropogenic land subsidence in several US cities, offering crucial insights into the localized impacts of human activities on subsidence in these cities.

Risk of urban subsidence to US infrastructure

One of the most harmful yet less visible effects of urban land subsidence is the potential damage to buildings, foundations and infrastructure, primarily caused by differential land motion37,38. Unlike flood-related subsidence hazards, where risks manifest only when high rates of subsidence lower the land elevation below a critical threshold13,14, subsidence-induced infrastructure damage can occur even with minor changes in land motion12,37. The latent nature of this risk means that infrastructure can be silently compromised over time, with damage only becoming evident when it is severe or potentially catastrophic. This risk is often exacerbated in rapidly expanding urban centers.

To investigate the hazards to buildings associated with land subsidence across the 28 US cities, we estimated the angular distortion (β), strain between two adjacent points due to differential settlement over a given 25-year period39 (Methods). On the basis of previous studies37,38 and standard geotechnical engineering practices40,41, we categorized the angular distortion hazard into four levels: low (β < 0.02°), medium (0.02° ≤ β < 0.04°), high (0.04° ≤ β ≤ 0.12°) and very high (β > 0.12°). We estimate that a total land area of 12,000; 862; 138 and 1.3 km2 are affected by low, medium, high and very high angular distortion, respectively (Extended Data Figs. 3, 6 and 7 and Supplementary Table 4). Although the high and very high-hazard zones affect only about 1% of the total land area in the 28 cities (Supplementary Table 4), these areas represent critical zones within the urban landscape where the structural integrity of infrastructure may be compromised37,39,40. Generally, angular distortion over 0.06° (high and very high-hazard zones) is likely to cause the development and/or propagation of structural deterioration, such as the fracturing and cracking of infrastructure, depending on the type of building or infrastructure37,38,40. Additionally, we find that 31.9% and 51.8% of high- and very high-hazard zones occur in areas experiencing uplift (Extended Data Fig. 8), emphasizing that infrastructure angular distortion hazards are primarily associated with differential land motion and not subsidence hotspots42.

Next, we evaluated the risk to the buildings associated with urban differential subsidence using a risk matrix. The risk matrix associates angular distortion hazards with building densities as an indicator for the risk likelihood to buildings in five classes: very low, low, medium, high and very high (Methods). Overall, we assessed the risk for a combined 5.6 million buildings across all cities. Our analysis shows that across the cities, the risk to buildings is generally low, with the majority (>99%) of the buildings classified as low to medium risk (Fig. 4, Extended Data Figs. 3, 9 and 10, and Supplementary Table 4). The high and very-high-risk areas include more than 29,000 buildings from the 28 US cities (Fig. 4i). In terms of the ratio of high and very-high-risk buildings to the total buildings in each city, San Antonio (1 in 45), Austin (1 in 71), Fort Worth (1 in 143) and Memphis (1 in 167) have the highest proportions (Supplementary Table 4). Additionally, San Antonio, Austin and Houston contribute more than 82% of the buildings at very high risk, having 1,515; 706 and 376 buildings, respectively.

a–h, Spatial risk maps of buildings in New York (a), Seattle (b), Detroit (c), Memphis (d), Fort Worth (e), Austin (f), Houston (g) and San Antonio (h). The risk maps for all cities are shown in Extended Data Figs. 3, 9 and 10. The risks are categorized into five classes: very low (VL), low (L), medium (M), high (H) and very high (VH). i, Distribution of buildings exposed to different risk levels in each city. Note that the bars only show the H and VH risk categories. Supplementary Table 4 summarizes the distribution of risks for each city. Background images in a–h from streets-dark ESRI, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

However, it is crucial to recognize that the occurrence of buildings in high and very-high-risk zones does not immediately imply failure. Other considerations, such as the soil type, foundation materials, construction materials, construction practices, building type, building age, building maintenance or existing hazards (for example, seismic hazards, extreme weather events and flooding) are important for assessing the overall risk to buildings38,40,41. Nevertheless, these high and very-high-risk zones in the cities indicate areas where subsidence-derived stressors may unfavorably tilt buildings and other infrastructure towards the higher end of the risk spectrum. Within the context of a socioeconomic framework, quantitative spatial hazard/risk information are essential in urban planning and land-use zoning, helping local policymakers to identify areas where new development should proceed or be restricted due to existing risk levels37.

Addressing urban land subsidence

How can we effectively respond to urban land subsidence? Is it possible to prevent cities from sinking? While there is no panacea for urban land subsidence, effective responses generally involve mitigation and adaptation, akin to strategies for addressing climate change6 (Fig. 5).

Framework for responding to land subsidence risks. The framework is divided into four key components: Assess (this study), Action (mitigation and adaptation), Engage, and Implement and monitor. The arrows show the flow and interconnection between different components highlighting a cyclical and iterative approach to managing land subsidence. Icon credits: money transfer from Iconduck under a Creative Commons license CC0; remainder from SVG Repro: cracked buildings, trees, tall buildings, stakeholder meeting, seminar, seminar nerd head under a Creative Commons license CC0; grass under a Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0; clipboard under an MIT license. The managed aquifer recharge inset figure was inspired by Dillon et al.46.

A crucial first step is identifying location-specific drivers as anthropogenic causes can be mitigated, whereas subsidence caused by natural processes often necessitates adaptation3,4,6 (Fig. 5). However, separating these drivers is challenging as multiple subsidence mechanisms are sometimes superimposed at a singular location2. For example, natural sediment compaction in many coastal and delta cities is compounded by upstream dam construction, sand mining, excessive groundwater withdrawal and hydrocarbon extraction, accelerating subsidence rates43,44. In other non-coastal urban cities, where GIA or tectonics processes drive subsidence, anthropic activities such as infrastructural loading and groundwater exploitation contribute to subsidence. In these areas, targeted mitigation through strategic dam planning, managed aquifer recharge and resource extraction policies may be useful to control, pause or even reverse subsidence despite the existing background rates6,44,45,46. To be effective, proposed mitigation solutions must be technically viable and aligned with community needs, balancing the trade-offs between subsidence risks and resource access47.

When mitigation is insufficient, adaptation measures tailored to address the local vulnerabilities become essential to minimize impacts3,6. For example, in coastal cities where land subsidence amplifies sea-level rise impacts (for example, Houston; San Diego; Washington, DC; Boston; New York), sustainable adaptation may involve protection, accommodation, retreat and advance47. Cities with pluvial and fluvial flooding risks (for example, Memphis, Philadelphia, Chicago, Columbus, Charlotte, Indianapolis and Los Angeles)48 may require new and upgraded structural protection, raised land, improved drainage systems and green infrastructure6,48,49. For cities susceptible to subsidence-induced infrastructure hazards, such as the cities highlighted in this study, adaptation efforts should focus on retrofitting existing infrastructure, integrating subsidence sensitivity into construction codes, limiting infrastructure loading and enhanced monitoring of critical infrastructure6,37,38,50 (Fig. 5).

Ultimately, a robust and sustainable mitigative and adaptive framework should encompass continuous monitoring, stakeholder collaboration and flexible mitigation and adaptive management plans that evolve with changing conditions (Fig. 5). Regardless of the pathway a city chooses, any effective mitigation and adaptation effort must be targeted to the dominant subsidence driver in each city, proportional to local vulnerabilities, and incorporate a multifaceted approach.

Methods

Selection criteria for US cities and population dataset

This study focused on the 28 most populous US cities as defined by the 2020 US census data. The combined population of the 28 cities is 39 million people (Supplementary Table 2), representing ~12% of the current US population. Geographically, the cities were selected from 19 different states; the only states with more than one city are Texas (six cities), California (four cities) and Tennessee (two cities). Among the 28 cities, 11 are coastal, eight are riparian and nine are inland cities. Coastal cities, which are located directly along the coast or are subject to tidal influences and sea-level rise, include New York, NY; Los Angeles, CA; Houston, TX; Philadelphia, PA; San Diego, CA; Jacksonville, FL; San Francisco, CA; Seattle, WA; Washington, DC; Boston, MA; and Portland, OR. Riparian cities situated close to rivers include San Antonio, TX (San Antonio River); Austin, TX (Colorado River); Columbus, OH (Scioto River); Indianapolis, IN (White River); Nashville, TN (Cumberland River); El Paso, TX (Rio Grande); Detroit, MI (Detroit River) and Memphis, TN (Mississippi River). Inland cities, not situated along the coast or near major rivers include Chicago, IL; Phoenix, AZ; Dallas, TX; San Jose, CA; Fort Worth, TX; Charlotte, NC; Denver, CO; Oklahoma City, OK and Las Vegas, NV. Note that Houston, TX (Buffalo Bayou); Philadelphia, PA (Delaware River) and Washington, DC (Potomac River), are situated close to major rivers and not directly on the coast but are considered coastal due to the influences of tides on the rivers and sea-level-rise impacts on these cities. Of the 28 US cities, 13 are among the 20 fastest-growing cities in the United States, with population increases between 10% and 26% from 2010 to 2020 (ref. 51), indicative of urban population expansion and infrastructure development trends in recent years. A literature review conducted for the 28 cities analyzed here shows that prior vertical land motion (VLM) studies exist for only 11 cities (predominantly coastal), highlighting a systematic lack of spatially resolved datasets for inland and riparian cities nationwide (Supplementary Table 1).

To estimate the population for each US city, we used the 2020 open-access topologically integrated geographic encoding and referencing (TIGER) system demographic and economic data from the US Census Bureau52. This dataset provides detailed population estimates for each city, subdivided into census blocks.

SAR analysis

To generate high spatial resolution maps of VLM for the 28 US cities, we applied advanced multitemporal wavelet-based interferometric synthetic aperture radar (WabInSAR) algorithm53,54,55 to 2,512 SAR images acquired in ascending orbit of Sentinel-1 A/B satellites between 2015 and 2021 (Supplementary Table 5). To this end, we generated ~400 sets of high-quality interferograms for each city (12,311 total interferograms) using the GAMMA software56 within a maximum temporal baseline of 700 days and a perpendicular baseline of 500 m. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio and enable precise and detailed observations of surface deformation, we applied a multi-looking factor of 12 × 2 in the range and azimuth directions, respectively, to obtain an average ground resolution of ~28 m. We performed accurate co-registration of the SAR images using the satellite’s precise ephemeris data, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 30-m Digital Elevation Model and an enhanced spectral diversity algorithm57. We discarded pixels from the distributed scatterers with a coherence of less than 0.7 and permanent scatterers with amplitude dispersion of more than 0.3, following Lee and Shirzaei55. Next we employed a modified 2D minimum cost flow phase unwrapping algorithm to estimate absolute phase changes of the sparse retained (that is, elite) pixels in each interferogram54,58. The unwrapped interferograms are corrected for the effect of orbital error59, topography-correlated atmospheric phase delay and spatially uncorrelated topography error by applying a suite of wavelet-based filters53. We applied a reweighted least squares optimization to estimate the time series and rate of land motion along the satellite’s line of sight (LOS) for each pixel, using a zero-velocity local reference point selected from stable areas outside the city boundary.

We assume most horizontal motions are of a spatially smooth pattern that can be estimated and removed using a polynomial. This is a valid assumption because there are no active faults within study areas, and no major earthquakes occurred within the study period to affect the observed LOS velocities. Thus, the remainder of the LOS signal is mainly due to vertical deformation. We projected the corrected LOS velocity for each pixel (LOSi) in the vertical direction to obtain the VLM following equation (1):

where cos θi is the local incidence angle for each pixel. The obtained VLM is with reference to the local reference point for each city. To transform the VLM from a local to a global reference frame, we employed a global VLM model60 and applied an affine transformation to align the VLM rates to the IGS14 global reference frame61,62. Extended Data Figs. 1–3 show the final VLM maps in the IGS14 reference frame for the 28 cities63.

To examine the quality of our results, we evaluated the standard deviation associated with the LOS velocities and validated the VLM rates by comparing them with global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) data. The spatial maps for all cities indicate that the standard deviation values are below 1 mm per year, suggesting high precision measurements (Supplementary Figs. 7–9). To validate the accuracy of the VLM rates, we compared the global VLM rates with observations from 154 GNSS stations in 28 cities obtained from the Nevada Geodetic Laboratory64. The comparison shows an 88% correlation (R2 value), with a mean difference of 0.1 mm per year and a standard deviation of 1.1 mm per year (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Subsidence exposure analysis

To estimate exposure to subsidence, we use the area-weighted average subsidence rate, which better represents the spatially heterogeneous nature of land subsidence across cities. Unlike a simple average, which treats all locations equally, this approach ensures that larger subsiding areas contribute more to the final estimate, minimizing bias from localized hotspots with extreme rates.

To this end, each city was divided into a grid of spatial units, each with a corresponding VLM rate. The area-weighted average subsidence rate \(\left({\bar{S}}_\mathrm{w}\right)\) was calculated using equation (2):

where Si is the VLM rate (mm per year) and Ai is the area (km2). This method ensures that subsidence estimates reflect the total affected area (for example, widespread sinking zones), rather than being skewed by localized hotspots (small areas with extreme rates).

To quantify the population exposed to urban subsidence, we used the 2020 census data to estimate the population affected by various subsidence rates. For each census block, we classified the population as exposed to subsidence based on the calculated median subsidence rate for the InSAR pixel in the census block. We classified the subsidence rates (mm per year) into five categories in order of increasing subsidence hazard severity: VLM ≥ 0 (not exposed to subsidence), −3 ≥ VLM < 0, −5 ≥ VLM < −3, −10 ≥ VLM < −5 and VLM < −10. Figure 2 shows the estimated population exposure for the 28 US cities.

Infrastructure risk analysis

Infrastructure risk has emerged as a critical concern in the United States due to both historical and recent building failures. A synthesis of collapsed buildings in the United States documented 225 incidences of building collapse between 1989 and 2000 (ref. 65). While maintenance deficiencies, extreme events, construction and design errors are identified as the major causes of these collapses, about 2% of the collapsed buildings were directly attributable to subsidence-related issues, including foundation and soil settlement. Furthermore, another 30% (60 out of 225) of these failures were classified as having unknown causes. More recently, three building failures were reported in Miami, FL (June 2021); New York City, NY (April 2023) and Davenport, IA (May 2023), resulting in over 100 casualties66. The risk to infrastructure depends on intrinsic hazards, including the type of construction material age and maintenance state of the infrastructure; extrinsic hazards, such as soil type and foundation materials; and subsidence-related hazards, such as relative rotations, horizontal strain, total and differential settlement37,38,39,67. Often, a combination of these factors can compromise the integrity of infrastructures over time, increasing the risk of failure. Given the long-term and prevalent nature of subsidence hazards in US cities, along with their latent nature, it is probable, even expected, that land subsidence may have played an underrecognized role in past infrastructure failures. In this study, we focus on this subsidence-related hazard in major US urban cities and their impact on urban infrastructure and property37,38,39.

To estimate the risk to infrastructure due to land subsidence in US cities, we used a risk matrix, which associates the severity of a hazard with the exposure and vulnerability of the elements at risk. Here we adopt the risk matrix, which combines differential settlement hazard with the building densities to produce varying risk levels for each city categorized as very low—VL, low—L, medium—M, high—H and very high—VH37,38,67,68 (Supplementary Fig. 11). The hazard associated with differential settlement was evaluated by calculating the angular distortion (β), defined by equation (3) as the ratio of the differential settlement (Δδ) of adjacent pixels (28 m) to their horizontal distance (l).

The calculated β values were classified into four hazard severity levels: low (β < 0.02°), medium (0.02° ≤ β < 0.04°), high (0.04° ≤ β ≤ 0.12°) and very high (β > 0.12°) based on predefined criteria following geotechnical engineering standards for allowable settlements on buildings and previous studies37,38,39,40. The hazard categories indicate the likelihood of structural damage, ranging from aesthetic issues (for example, cracks, uneven floors and misaligned doors and windows) to extensive structural failures (for example, foundation settling and collapse of buildings)37,38,40,68. The total land area affected by differential subsidence hazards in US cities is summarized in Supplementary Table 4, and the spatial maps for β are shown in Extended Data Figs. 3, 6 and 763.

Whereas we adopt this commonly applied differential settlement hazard categorization, it is important to note that the critical threshold for angular distortion (βcrit) varies based on the type of construction materials, foundation type and soil properties. For example, brick-bearing walls or buildings with steel or reinforced concrete frames may tolerate βcrit up to 0.19° before structural damage occurs40,41,69,70, whereas brick walls, beams and columns or encased steel frames exhibit moderate to severe damage at β greater than 0.38° (refs. 40,71). In contrast, structures built on sand or soft clay may fail at much lower thresholds (β > 0.02°)39. To assess cumulative impacts, we assumed a linear rate of VLM over a 25-year period, consistent with short-term subsidence projections in urban environments2,38. However, we note the lack of spatially resolved building damage data in US cities, which limits our ability to cross validate or directly correlate identified high-hazard/high-risk zones with documented structural damage. Future studies should address this gap by integrating high-resolution building footprint datasets to compute β or other infrastructure hazard evaluation metrics (for example, deflection ratios and relative building rotation) at the scale of individual buildings. Pairing these data with geotechnical classifications (for example, soil type, bedrock depth) and foundation engineering metadata (for example, friction piles, raft or bedrock-anchored designs) would enable structure-specific risk assessments. Despite this limitation, our analysis offers a structured framework for highlighting areas of potential concern and prioritizing zones within cities for further localized investigations that could validate these risk assessments and guide targeted mitigation efforts.

For the building densities, we extracted the building base outline developed by Microsoft72. The building footprint database was created using a semantic segmentation pixel recognition scheme and polygonization, which accurately delineates the shape and size of buildings for each US city. For an 80-m grid, we assigned each grid a classification of low (building densities < 518), medium (518 ≥ building densities < 3,300) and high (building densities ≥ 3,300) housing densities (in housing units per km2) based on the 2020 urban areas density thresholds proposed by the US Census Bureau73. Figure 4 and Extended Data Figs. 3, 9 and 10 show the spatial risk maps created by combining the building density and β. Supplementary Table 4 summarizes the number of buildings for each risk category in the US cities.

Groundwater extraction and groundwater-level dataset

For the groundwater extraction data, we obtained estimates of groundwater withdrawal from aquifers available on a county basis for 32 counties relevant to this study74,75. The dataset includes groundwater withdrawal estimates from 66 principal aquifers and other non-principal aquifers during 2015 for various categories by different uses (public supply, domestic, irrigation, thermoelectric power, industrial, mining, livestock and aquaculture water use). A summary of the 32 counties and the categorized groundwater use is provided in Supplementary Table 6.

To estimate the change in groundwater level in the US cities, we collected 90 time series of daily water level measurements from the US Geological Survey (USGS)76. The groundwater data were available for 13 cities, including 27 confined aquifers, 42 unconfined aquifers and 21 wells with no aquifer labels, termed unknown aquifers (Supplementary Table 7). The location, depths and aquifer types for the groundwater wells are summarized in Supplementary Table 7. We used Theil–Sen regression slopes (equation (4)), which provides a robust estimation of the median slope of the data, to calculate the rate of change in groundwater level \(\left(\frac{{\mathrm{d}h}}{{\mathrm{d}t}}\right)\) for the same time period as the InSAR time series (2015–2021):

where h and t are the groundwater levels and times, respectively77,78.

To evaluate the relationship between groundwater-level changes and changes in land motion, we averaged the non-glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA) VLM rates from InSAR pixels within a 50-m radius of the well locations and compared them with the \(\frac{{\mathrm{d}h}}{{\mathrm{d}t}}\) for each groundwater well. Only 46 of the 90 wells were located within a 50-m radius of the InSAR pixels and could be compared with the VLM rates. To estimate the non-GIA VLM rates, we used the ICE-6G-D GIA model29 to estimate and exclude the GIA contributions at the InSAR pixels for each US city. The distributions of groundwater-level changes and VLM rates across different aquifer types shows a narrow variance (σ = 0.2 m per year for groundwater-level changes, σ = 0.06–0.3 mm per year for VLM) and a near-zero cluster value for the unknown and unconfined aquifers (Extended Data Fig. 5). In contrast, confined aquifers exhibit broader distributions (σ = 1.1 m for groundwater-level changes, σ = 0.4 mm per year for VLM), indicative of a spatially heterogeneous response and a fit informed by the range of data distribution rather than a few extreme values or clustered data points. To assess the degree of correlation between the temporal dynamics of groundwater levels and vertical deformation, we computed the lagged correlation matrix between the detrended time series of the groundwater level and the VLM data, given by equation (5):

where ρ(k) is the Pearson correlation coefficient at lag k, Xi and Yi are the time series of groundwater level and VLM data at time i, respectively, and \(\bar{X}\) and \(\bar{Y}\) are the mean values. The correlation coefficient (ρ) ranges from −1 to 1, indicating a perfect positive to a perfect negative correlation. For each time series, we presented the maximum lagged correlation value.

To estimate the bivariate dependence of VLM on groundwater levels in US cities, we statistically modeled their joint probability using copula functions. We applied the Multivariate Copula Analysis Toolbox79. Here we focused our analysis on wells with the highest positive correlation in five cities (New York; Washington, DC; Houston; Memphis and San Diego) with confined aquifer layers. For each city, we tested five different copula functions—Gaussian, t, Clayton, Frank and Gumbel—and estimated the parameter values for each copula within a 95% confidence interval using Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulations. To determine the best fit, we ranked copula models based on multiple goodness-of-fit criteria, including maximum likelihood, Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The best-fit copula for each city was selected based on the lowest BIC value. The best-fit copula varied by city, reflecting differences in dependence structures. The full ranking (Akaike Information Criterion/BIC) is detailed in Supplementary Table 8. Next, using the optimal copula model’s type and parameter values, we resampled a bivariate dataset of 100,000 members, which reflects the statistical dependence structure between VLM and groundwater levels as captured by the copula model, and mapped the generated copula samples back to their original data ranges (that is, VLM and groundwater levels).

To validate the copula model performance, we qualitatively and quantitatively compared the empirical data against simulations from both the best- and worst-performing copula models (Supplementary Figs. 2–6). For each city, we juxtaposed the original groundwater level and VLM data with resampled data generated from the best-fit (blue points and lines, for example, t copula in New York) and worst-fit (green points and lines, for example, Gumbel copula in New York) copula models. The marginal distributions highlight disparities in their ability to replicate observed patterns, with the best-performing copula for each city aligning more closely with the empirical data, while the worst-performing models exhibit systematic deviations, particularly in tail regions (Supplementary Figs. 2–6). The reconstructed time series further illustrates this contrast, as the best-performing model (ρ = 0.3–0.9) captures groundwater–VLM temporal trends compared to the poorly fitting alternative (ρ = 0.1–0.5) (Supplementary Figs. 2–6).

From the resampled dataset, we evaluated the conditional probability of VLM occurring under varying groundwater levels as P(VLM|GWL = x. We then integrated the total conditional probability of subsidence exceeding −1 mm (that is, VLM < −1 mm) as P(VLM < −1|GWL = x for each value of groundwater levels, normalized between minimum and maximum values (Fig. 3c).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The VLM rate, angular distortion and risk datasets for the 28 US cities are available through the Virginia Tech repository at https://doi.org/10.7294/27606942. The supplementary table for this paper is accessible at https://doi.org/10.7294/27606942. The Sentinel-1 data used in this study are publicly available from the Alaska Satellite Facility and can be accessed at https://asf.alaska.edu/. The population dataset is available from the US Census Bureau at https://www.census.gov/. The groundwater data can be obtained from USGS at https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/gw.

Code availability

The WabInSAR algorithm version 5.6 used to perform the SAR analysis is available at https://www.eoivt.com/software.

References

Herrera-García, G. et al. Mapping the global threat of land subsidence. Science 371, 34–36 (2021).

Shirzaei, M. et al. Measuring, modelling and projecting coastal land subsidence. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 40–58 (2021).

Ohenhen, L. O. et al. Disappearing cities on US coasts. Nature 627, 108–115 (2024).

Nicholls, R. J. & Shirzaei, M. Earth’s sinking surface. Science 384, 268–269 (2024).

Chaussard, E., Amelung, F., Abidin, H. & Hong, S.-H. Sinking cities in Indonesia: ALOS PALSAR detects rapid subsidence due to groundwater and gas extraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 128, 150–161 (2013).

Erkens, G., Bucx, T., Dam, R., de Lange, G. & Lambert, J. Sinking coastal cities. Proc. Int. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 372, 189–198 (2015).

Wu, P.-C., Wei, M. & D’Hondt, S. Subsidence in coastal cities throughout the world observed by InSAR. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098477 (2022).

Cigna, F. & Tapete, D. Land subsidence and aquifer-system storage loss in central Mexico: a quasi-continental investigation with Sentinel-1 InSAR. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098923 (2022).

Khorrami, M. et al. Groundwater volume loss in Mexico City constrained by InSAR and GRACE observations and mechanical models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101962 (2023).

Ao, Z. et al. A national-scale assessment of land subsidence in China’s major cities. Science 384, 301–306 (2024).

Haghshenas Haghighi, M. & Motagh, M. Uncovering the impacts of depleting aquifers: a remote sensing analysis of land subsidence in Iran. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk3039 (2024).

Ohenhen, L. O., Shirzaei, M. & Barnard, P. L. Slowly but surely: exposure of communities and infrastructure to subsidence on the US East Coast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA Nexus 3, pgad426 (2024).

Shirzaei, M. & Bürgmann, R. Global climate change and local land subsidence exacerbate inundation risk to the San Francisco Bay Area. Sci. Adv. 4, eaap9234 (2018).

Miller, M. M. & Shirzaei, M. Land subsidence in Houston correlated with flooding from Hurricane Harvey. Remote Sens. Environ. 225, 368–378 (2019).

Galloway, D. L. & Burbey, T. J. Review: regional land subsidence accompanying groundwater extraction. Hydrogeol. J. 19, 1459–1486 (2011).

Parsons, T. The weight of cities: urbanization effects on Earth’s subsurface. AGU Adv. 2, e2020AV000277 (2021).

Nicholls, R. J. et al. A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change and coastal flood exposure. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 338–342 (2021).

He, C. et al. Future global urban water scarcity and potential solutions. Nat. Commun. 12, 4667 (2021).

Galloway, D. L., Jones, D. R. & Ingebritsen, S. E. (eds) Land Subsidence in the United States 1182 (USGS, 1999).

Miller, M. M. & Shirzaei, M. Spatiotemporal characterization of land subsidence and uplift in Phoenix using InSAR time series and wavelet transforms. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 5822–5842 (2015).

Amelung, F., Galloway, D. L., Bell, J. W., Zebker, H. A. & Laczniak, R. J. Sensing the ups and downs of Las Vegas: InSAR reveals structural control of land subsidence and aquifer-system deformation. Geology 27, 483–486 (1999).

Törnqvist, T. et al. Mississippi Delta subsidence primarily caused by compaction of Holocene strata. Nat. Geosci. 1, 173–176 (2008).

Hasan, M. F. et al. Global land subsidence mapping reveals widespread loss of aquifer storage capacity. Nat. Commun. 14, 6180 (2023).

Davydzenka, T., Tahmasebi, P. & Shokri, N. Unveiling the global extent of land subsidence: the sinking crisis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL104497 (2024).

National Flood Insurance Program (FEMA, 2023); https://www.fema.gov/national-flood-insurance-program

Nicholls, R. J. & Cazenave, A. Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science 328, 1517–1520 (2010).

Sweet, W. V. et al. Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States: Updated Mean Projections and Extreme Water Level Probabilities Along U.S. Coastlines NOAA Technical Report NOS 01 (NOAA, 2022).

Karegar, M. A., Dixon, T. H. & Engelhart, S. E. Subsidence along the Atlantic coast of North America: insights from GPS and late Holocene relative sea level data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 3126–3133 (2016).

Peltier, W. R., Argus, D. F. & Drummond, R. Comment on “an assessment of the ICE-6G_C(VM5a) glacial isostatic adjustment model” by Purcell et al. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 123, 2019–2028 (2018).

Bürgmann, R., Hilley, G., Ferretti, A. & Novali, F. Resolving vertical tectonics in the San Francisco Bay Area from permanent scatterer InSAR and GPS analysis. Geology 34, 221–224 (2006).

Terzaghi, K. Principles of soil mechanics, IV—settlement and consolidation of clay. Eng. News Rec. 95, 874–878 (1925).

Eggleston, J. & Pope, J. Land Subsidence and Relative Sea-Level Rise in the Southern Chesapeake Bay Region No. 1392 (USGS, 2013).

Jasechko, S. et al. Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally. Nature 625, 715–721 (2024).

Shirzaei, M., Ojha, C., Werth, S., Carlson, G. & Vivoni, E. R. Comment on “short-lived pause in Central California subsidence after heavy winter precipitation of 2017” by K. D. Murray and R. B. Lohman. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav8038 (2019).

Ojha, C., Werth, S. & Shirzaei, M. Groundwater loss and aquifer system compaction in San Joaquin Valley during 2012–2015 drought. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124, 3127–3143 (2019).

Ghobadi-Far, K., Werth, S., Shirzaei, M. & Bürgmann, R. Spatiotemporal groundwater storage dynamics and aquifer mechanical properties in the Santa Clara Valley inferred from InSAR deformation over 2017–2022. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105157 (2023).

Cigna, F. & Tapete, D. Present-day land subsidence rates, surface faulting hazard and risk in Mexico City with 2014–2020 Sentinel-1 IW InSAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 253, 112161 (2021).

Ohenhen, L. O. & Shirzaei, M. Land subsidence hazard and building collapse risk in the coastal city of Lagos, West Africa. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF003219 (2022).

Burland, J. B. & Wroth, C. P. Settlement of Buildings and Associated Damage (Building Research Establishment, 1975).

Skempton, W. & Macdonald, D. H. The allowable settlements of buildings. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. 6, 727–768 (1956).

Bjerrum, L. Allowable settlements of structures. Proc. Eur. Conf. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 2, 135–137 (1963).

Ye, S. et al. A novel approach to model earth fissure caused by extensive aquifer exploitation and its application to the Wuxi Case, China. Water Resour. Res. 54, 2249–2269 (2018).

Bagheri-Gavkosh, M. et al. Land subsidence: a global challenge. Sci. Total Environ. 778, 146193 (2021).

Kondolf, G. M. et al. Save the Mekong Delta from drowning. Science 376, 583–585 (2022).

Holzer, T. L. State and local response to damaging land subsidence in United States urban areas. Eng. Geol. 27, 449–466 (1989).

Dillon, P., Pavelic, P., Page, D., Beringen, H. & Ward, J. Managed Aquifer Recharge: An Introduction Waterlines Report Series No. 13 (Australian National Water Commission, 2009).

Oppenheimer, M. et al. in Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects (eds Field, C. B. et al.) 1039–1099 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Bates, P. D. et al. Combined modeling of US fluvial, pluvial, and coastal flood hazard under current and future climates. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR028673 (2021).

Quagliolo, C. et al. Pluvial flood adaptation using nature-based solutions: an integrated biophysical-economic assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 902, 166202 (2023).

Siriwardane-de Zoysa, R. et al. The ‘wickedness’ of governing land subsidence: policy perspectives from urban Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE 16, e0250208 (2021).

Fastest growing cities. Exploding Topics https://explodingtopics.com/blog/fastest-growing-cities (2024).

TIGER/Line Shapefiles and TIGER/Line Files (US Census Bureau, 2020); https://www.census.gov/geographies/mapping-files/time-series/geo/tiger-data.2020.html

Shirzaei, M. & Bürgmann, R. Topography correlated atmospheric delay correction in radar interferometry using wavelet transforms. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L01305 (2012).

Shirzaei, M. A wavelet-based multitemporal DInSAR algorithm for monitoring ground surface motion. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 10, 456–460 (2013).

Lee, J.-C. & Shirzaei, M. Novel algorithms for pair and pixel selection and atmospheric error correction in multitemporal InSAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 286, 113447 (2023).

Werner C. et al. Gamma SAR and interferometric processing software. In Proc. ERS-Envisat Symposium (2000).

Shirzaei, M., Bürgmann, R. & Fielding, E. J. Applicability of Sentinel-1 terrain observation by progressive scans multitemporal interferometry for monitoring slow ground motions in the San Francisco Bay Area. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2733–2742 (2017).

Costantini, M. A novel phase unwrapping method based on network programming. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 36, 813–821 (1998).

Shirzaei, M. & Walter, T. R. Estimating the effect of satellite orbital error using wavelet-based robust regression applied to InSAR deformation data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 49, 4600–4605 (2011).

Hammond, W. C., Blewitt, G., Kreemer, C. & Nerem, R. S. GPS imaging of global vertical land motion for studies of sea level rise. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2021JB022355 (2021).

Ohenhen, L. O., Shirzaei, M., Ojha, C. & Kirwan, M. L. Hidden vulnerability of US Atlantic coast to sea-level rise due to vertical land motion. Nat. Commun. 14, 2038 (2023).

Blackwell, E., Shirzaei, M., Ojha, C. & Werth, S. Tracking California’s sinking coast from space: implications for relative sea-level rise. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba4551 (2020).

Ohenhen, L. et al. Land Subsidence Risk in US Metropolises (University Libraries, Virginia Tech, 2024); https://doi.org/10.7294/27606942

Blewitt, G., Hammond, W. C. & Kreemer, C. Harnessing the GPS data explosion for interdisciplinary science. Eos 99, EO104623 (2018).

Hadipriono, F. C. & Wardhana, K. Study of recent building failures in the United States. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 17, 151–158 (2003).

Aghayere, A. 4 recent building collapses raise concerns about America’s aging infrastructure. Finance & Commerce https://finance-commerce.com/2024/01/4-recent-building-collapses-raise-concerns-about-americas-aging-infrastructure/ (2024).

Cigna, F. & Tapete, D. Satellite InSAR survey of structurally-controlled land subsidence due to groundwater exploitation in the Aguascalientes Valley, Mexico. Remote Sens. Environ. 254, 112254 (2021).

Fernández-Torres, E., Cabral-Cano, E., Solano-Rojas, D., Havazli, E. & Salazar-Tlaczani, L. Land subsidence risk maps and InSAR based angular distortion structural vulnerability assessment: an example in Mexico City. Proc. Int. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 382, 583–587 (2020).

Boscardin, M. & Cording, E. Building response to excavation-induced settlement. J. Geotech. Eng. 115, 1–21 (1989).

Day, R. Differential movement of slab-on-grade structures. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 4, 236–241 (1990).

Wood, R. H. The stability of tall buildings. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. 11, 69–102 (1958).

Microsoft USBuildingFootprints. Github https://github.com/Microsoft/USBuildingFootprints/ (2013).

Ratcliffe, M. Redefining Urban Areas Following 2020 Census (US Census Bureau Geography Division, 2022); https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2022/12/redefining-urban-areas-following-2020-census.html

Lovelace, J. K., Nielsen, M. G., Read, A. L., Murphy, C. J. & Maupin, M. A. Estimated Groundwater Withdrawals from Principal Aquifers in the United States, 2015 USGS Circular 1464 (USGS, 2020); https://doi.org/10.3133/cir1464

Dieter, C. A. et al. Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2015 USGS Circular 1441 (USGS, 2018); https://doi.org/10.3133/cir1441

Groundwater Data for the Nation (USGS, 2024); https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/gw

Theil, H. A rank-invariant method of linear and polynomial regression analysis. Indag. Math. 12, 386–392 (1950).

Sen, P. K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 63, 1379–1389 (1968).

Sadegh, M., Ragno, E. & AghaKouchak, A. Multivariate copula analysis toolbox (MvCAT): describing dependence and underlying uncertainty using a Bayesian framework. Water Resour. Res. 53, 5166–5183 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Defense, and S.W., M.S. and K.G.-F. are partially funded by National Aeronautics and Space Agency (#80NSSC21K0061).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.O.O., M.S. and G.Z. conceptualized the study. L.O.O., M.S., J.L., N.S. and F.O. created the figures. L.O.O. and M.S. wrote the first draft of the paper with contributions from J.L. and S.W. Proposal generation and funding acquisition were carried out by M.S. and S.W. The analysis, writing reviews and editing were carried out by L.O.O., M.S., G.Z., J.L., S.W., G.C., M.K., N.S., F.O., K.G.-F., S.F.S., J.-C.L., A.T. and S.Z.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cities thanks Francesca Cigna, Tom Parsons and Shengli Tao for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Spatial Vertical Land Motion (VLM) for 12 Most Populated US Cities.

Spatially varying VLM for (a) New York, NY, (b) Los Angeles, CA, (c) Chicago, IL, (d) Houston, TX, (e) Phoenix, AZ, (f) Philadelphia, PA, (g) San Antonio, TX, (h) San Diego, CA, (i) Dallas, TX, (j) San Jose, CA, (k) Austin, TX, (l) Jacksonville, FL. Positive VLM (green-purple hues) indicates elevation gain (uplift), while negative VLM (yellow-orange-red hues) indicates elevation loss (land subsidence). Background images: streets-dark ESRI, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Spatial Vertical Land Motion (VLM) across 12 US Cities.

Spatially varying VLM for (a) Fort Worth, TX, (b) Columbus, OH, (c) Indianapolis, IN, (d) Charlotte, NC, (e) San Francisco, CA, (f) Seattle, WA, (g) Denver, CO, (h) Washington, DC, (i) Nashville, TN, (j) Oklahoma City, OK, (k) El Paso, TX, (l) Boston, MA. Positive VLM (green-purple hues) indicates elevation gain (uplift), while negative VLM (yellow-orange-red hues) indicates elevation loss (land subsidence). Background images: streets-dark ESRI, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Spatial Vertical Land Motion (VLM), Angular Distortion Hazards, and Risk for US Cities.

Spatially varying VLM for (a) Portland, OR, (b) Las Vegas, NV, (c) Detroit, MI, (d) Memphis, TN. Spatially varying angular distortion hazard for (e) Portland, OR, (f) Las Vegas, NV, (g) Detroit, MI, (h) Memphis, TN. The angular distortion hazard is estimated using Eq. (3). Risk of infrastructure damage for (i) Portland, OR, (j) Las Vegas, NV, (k) Detroit, MI, (l) Memphis, TN. The risk of infrastructure damage is created using the risk matrix in Supplementary Fig. 11. Background images: streets-dark ESRI, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

Extended Data Fig. 4 The Influence of Glacial Isostatic Adjustment (GIA) on Urban Subsidence in US Cities.

The GIA data is derived from the ICE-6G-D model29. National and state boundaries are based on public domain vector data by World DataBank (https://data.worldbank.org/) generated in MATLAB.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Relationship Between Groundwater Trends and Vertical Land Motion (VLM) Across US Cities.

Plot of groundwater level trends and VLM for 13 US cities, with confined, unconfined, and unknown aquifers represented by blue, yellow, and red markers, respectively. The density plots along the axes, color-coded to the aquifer type, illustrate the distributions of groundwater trends and VLM rate. This figure expands on Fig. 3a to highlight the dataset’s distribution.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Spatial Angular Distortion for 12 Most Populated US Cities.

Spatially varying angular distortion hazard for (a) New York, NY, (b) Los Angeles, CA, (c) Chicago, IL, (d) Houston, TX, (e) Phoenix, AZ, (f) Philadelphia, PA, (g) San Antonio, TX, (h) San Diego, CA, (i) Dallas, TX, (j) San Jose, CA, (k) Austin, TX, (l) Jacksonville, FL. The angular distortion hazard is estimated using Eq. (3). Background images: streets-dark ESRI, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Spatial Angular Distortion across 12 US Cities.

Spatially varying angular distortion hazard for (a) Fort Worth, TX, (b) Columbus, OH, (c) Indianapolis, IN, (d) Charlotte, NC, (e) San Francisco, CA, (f) Seattle, WA, (g) Denver, CO, (h) Washington, DC, (i) Nashville, TN, (j) Oklahoma City, OK, (k) El Paso, TX, (l) Boston, MA. The angular distortion hazard is estimated using Eq. (3). Background images: streets-dark ESRI, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Influence of Subsidence on Infrastructure Risks.

Comparison of the vertical land motion (VLM) versus adjacent VLM and the associated risk for US cities.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Estimated Risk to Infrastructure 12 Most Populated US Cities.

Risk of infrastructure damage for (a) New York, NY, (b) Los Angeles, CA, (c) Chicago, IL, (d) Houston, TX, (e) Phoenix, AZ, (f) Philadelphia, PA, (g) San Antonio, TX, (h) San Diego, CA, (i) Dallas, TX, (j) San Jose, CA, (k) Austin, TX, (l) Jacksonville, FL. The risk of infrastructure damage is created using the risk matrix in Supplementary Fig. 11. Background images: streets-dark ESRI, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Estimated Risk to Infrastructure across 12 US Cities.

Risk of infrastructure damage for (a) Fort Worth, TX, (b) Columbus, OH, (c) Indianapolis, IN, (d) Charlotte, NC, (e) San Francisco, CA, (f) Seattle, WA, (g) Denver, CO, (h) Washington, DC, (i) Nashville, TN, (j) Oklahoma City, OK, (k) El Paso, TX, (l) Boston, MA. The risk of infrastructure damage is created using the risk matrix in Supplementary Fig. 11. Background images: streets-dark ESRI, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–11.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–8.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1–4

Source data for Fig. 1a.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohenhen, L.O., Zhai, G., Lucy, J. et al. Land subsidence risk to infrastructure in US metropolises. Nat Cities 2, 543–554 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00240-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00240-y

This article is cited by

-

Building damage risk in sinking Indian megacities

Nature Sustainability (2025)

-

Present-day land subsidence risk in the metropolitan cities of Italy

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Sinking cities: how China is moving subsidence research forward

Nature (2025)