Abstract

Spin light-emitting diodes (spin-LEDs), which converts carrier spin information to optical polarization, are important for modern display application and future technologies including spin-based electronic circuits and quantum information science. Spin-LEDs operate through spin-polarized carrier injection, directly converting spin angular momentum into photon helicity. Recent advances in materials and mechanism understanding have significantly improved spin injection efficiency and device performance. This review discusses the fundamental principles and operation mechanisms of spin-LEDs, where we examine conventional spin injection approaches and their constraints. We then highlight the emerging role of chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS) in spin-LEDs, exploring how this novel mechanism could enhance circularly polarized electroluminescence efficiency and enable new device architectures. Finally, we provide perspectives on current challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Circularly polarized light (CPL) refers to photons in which the electric field vector rotates helically as it propagates, resulting in left- or right-handed circular polarization. Compared to other forms of light polarization, such as linear polarization, CPL offers greater potential due to the intrinsic angular momentum of photons, which enables the encoding of information beyond what is possible with linearly polarized light. The development of CPL sources plays an essential role in the modern display industry and future technologies including 3D display1,2, quantum computing and sensing3,4, information processing5,6,7, and chiral catalysis8,9.

Traditional approach for CPL generation mostly relies on a “top-down” method, where unpolarized photons are filtered and purified through optical components such as quarter-wave plates and polarizers. However, this method suffers from the inherent energy loss, complex infrastructure, and low sensitivity and resolution. Another strategy for CPL generation is through a “bottom-up” method, where materials or devices can directly produce CPL via photoexcitation or electrical excitation. Optical excitation gives rise to circularly polarized photoluminescence (CP-PL), while electrical excitation leads to circularly polarized electroluminescence (CP-EL). While substantial progress has been made in material design and mechanism understanding of CP-PL10,11,12,13, the development of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) capable of efficiently generating CP-EL has lagged significantly.

In contrast to CP-PL, CP-EL enables direct electrical generation of CPL, eliminating the need for external optical components and reducing energy losses associated with intermediate conversion steps. By directly converting electrical energy into CPL, CP-EL can maximize the energy efficiency, with the potential to convert 100% excitons into usable CPL14,15. Further, CP-EL allows for active electrical modulation of polarization states, making it a more practical choice for integrated photonic devices. These advantages make CP-EL a highly promising approach for real-world optoelectronic applications where tunability, scalability, and high efficiency are crucial.

There are generally two types of LEDs that generate CP-EL. One approach utilizes chiral materials as the emissive layer, where molecular chirality imprints the chirality into the excited state, leading to the CPL emission. LEDs that apply a chiral emissive layer to produce CP-EL are referred to as circularly polarized light-emitting diodes (CP-LEDs), or often circularly polarized organic light-emitting diodes (CP-OLEDs). This idea was initially explored by Peeters et al., who demonstrated the first CP-EL using a chiral polymer LED16, proving that molecular chirality alone could induce circular polarization in electroluminescence. Since then, significant progress has been made17.

The other approach employs spin-polarized carrier injection, where the angular momentum of injected carriers determines the polarization of electroluminescence. LEDs that rely on spin polarization injection to generate CP-EL are often referred to as spin-LEDs. These devices fall into the umbrella of spintronics as spin control and spin injection are crucial in their operation. In 1990, Datta and Das proposed a structure for injecting spin-polarized electrons into semiconductors18, laying the theoretical foundation for semiconductor spintronics. In 1999, Fiederling et al.19 demonstrated efficient spin injection from a dilute magnetic semiconductor (DMS) into a III-V semiconductor and successfully detected high circular polarization in the emitted light. Since then, significant progress has been made in optimizing spin injection efficiency, extending operational temperatures, and integrating new material platforms. Despite these advancements, conventional spin injection methods—such as ferromagnetic contacts—face challenges related to efficiency losses in spin injection20.

More recently, Beard’s group pioneered a promising new direction of spin-LED research21, which relies on a new mechanism, i.e., chirality-induced spin selectivity (CISS), to enable spin-LED function. Unlike traditional spin injection by using ferromagnetic injectors, the CISS effect allows for efficient spin polarization and injection without the need for external magnetic fields or ferromagnetic electrodes22, showing the potential to revolutionize spin-based optoelectronics.

This review aims to discuss the fundamental mechanisms that operate spin-LED, highlighting the key difference between spin-LED and CP-LED. We also summarized recent developments of spin-LED, where we examine conventional spin injection approaches and their constraints. Finally, we highlight the emerging role of CISS in spin-LEDs, exploring how this novel mechanism could enhance CP-EL efficiency and enable new device architectures.

Principles of spin-LEDs

Although both CP-LED and spin-LED can generate CP-EL, they possess distinct fundamental principles and operational mechanisms. It is thus essential to first distinguish these two approaches, CP-LED vs. spin-LED.

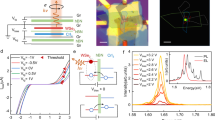

CP-LEDs generate CPL using chiral emissive materials (Fig. 1a). The recombination of unpolarized charge carriers occurs within the chiral emissive layer (typically organic), where the intrinsic chirality of the material induces asymmetry in radiative transitions (Fig. 1b). This innate asymmetry gives rise to CPL. The degree of circular polarization of emitted light is quantified by the dissymmetry factor (gCPL), which can be expressed as Eq.123.

a Schematic of a CP-LED device. b Dissymmetry in intensity of R- L-CPL emitted during the transition between quantum state i and j. gCPL is determined by TEDM(μ') and TMDM (m') within the chiral emissive material. c Schematic of a Spin-LED device. Mechanism CPL generation under d HH-LH degeneracy and e HH-LH non-degeneracy in Spin-LEDs. The transition probability (oscillator strength) from conduction bands to HH bands are 3 times of that to LH bands. [b is adapted from ref. 24. with permission].

Here, \(I\left({\sigma }^{+}\right)\) and \(I\left({{\rm{\sigma }}}^{-}\right)\) represents the intensities of right- and left- handed CPL. The value of gCPL can further be related to the transition dipole moment of a molecule. The terms μij and mij correspond to the transition electric dipole moment (TEDM) and transition magnetic dipole moment (TMDM) between states \(\left|i\right\rangle\) (ground) and \({|j}{\rm{\rangle }}\) (excited). The term θμm is the angle between TEDM and TMDM. From Eq. 1, the CPL generation in CP-LEDs is entirely dependent on the transition moments (μij and mij) and their spatial configuration within the chiral emissive layer (Fig. 1b)24. Importantly, the handedness and gCPL of CP-LEDs are independent of the spin polarization of charge carriers, relying solely on the chiral properties of the emissive material.

First reported in 1997 by Peeters et al.16, CP-LEDs have evolved into three main categories based on their emissive materials. Category 1: Chiral conjugated emissive polymers achieve CP-EL by incorporating chirality through side-chain modification16,25,26, main-chain chirality27, or chiral dopants28, offering high gCPL but limited to a 25% internal quantum efficiency (IQE) due to singlet-only emission. Category 2: Chiral metal complexes utilize heavy metals (e.g., Ir, Pt29, Zn30, Cu31) to enable near-unity intersystem crossing (ISC) via spin-orbit coupling (SOC), achieving 100% IQE but often exhibiting low gCPL. Lanthanide metals (e.g., Eu) enhance gCPL through f-f transitions but suffer from low quantum yields32. Category 3: Chiral thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules achieve 100% IQE without heavy metals by converting triplet excitons to singlets via reverse ISC, offering a better balance between efficiency and gCPL compared to the other two approaches33,34,35.

Spin-LEDs, on the other hand, generate CPL by injecting spin-polarized charge carriers into an achiral emissive layer (Fig. 1c). In general, spin-LEDs offer greater tunability, most notably the ability to electronically modulate the polarization direction of CPL compared to CP-LEDs36. Spin-LED normally consists of a ferromagnetic spin injector layer that can inject spin-polarized carriers and a semiconductor layer that can transfer the carrier spin angular momentum to photon angular momentum, i.e., CPL. Unlike CP-LEDs, spin-LEDs do not require chiral materials in the emissive layer. The helicity of emitted photons is directly determined by the spin state of recombining charge carriers. When electrons are injected from a ferromagnetic injector into a nonmagnetic semiconductor, they can retain their spin polarization over a certain distance (from 50 nm to 4 μm37,38,39), provided that spin injection is efficient, spin transport occurs without significant depolarization, and spin lifetime is sufficiently long (from 0.1 to 20 ns37,38,40).

It is important to note that not all semiconductors are capable of producing CP-EL when spin-polarized carriers are injected from spin injector contacts. In order to convert the spin angular momentum of carriers to photons, semiconductors in spin-LED need to possess spin-dependent optical transitions, which normally require a strong SOC and direct bandgap. Under the angular momentum conservation rule, the carrier spin information can then be transferred to the photon helicity. Below we use the traditional GaAs semiconductor as a model system to illustrate how spin polarized charge carriers can generate CP-EL. In GaAs with a zinc-blend structure, the conduction band is twofold degenerate at the center of the Brillouin zone, corresponding to spin-up and spin-down electrons (mj = ±1/2, where mj is magnetic angular momentum). The valence band is fourfold degenerate and consists of the heavy-hole (HH) and light-hole (LH) bands, which differ in their effective mass. Each valence band is twofold spin degenerate (mj = ±3/2, ±1/2). Radiative interband transitions follow selection rule Δmj = ±141. The polarization and intensity of light emitted during these transitions can be understood using the correspondence principle, where the magnetic angular momentums associated with specific transitions determine the polarization characteristics of the emitted light. The resultant possible optical transistions42 are summarized below and in Fig. 1d.

-

For transitions between the HH bands and the conduction bands, the recombination of a −1/2 electron with a −3/2 hole, and a +1/2 electron with a +3/2 hole, result in the light with opposite polarization directions (right hand σ+ and left hand σ-, respectively) in the plane perpendicular to the wave vector k.

-

In the case of the LH bands, transitions involving a −1/2 electron with a +1/2 hole, and a +1/2 electron with a −1/2 hole, also produce oppositely polarized light. However, transitions between electron and hole states with identical mj (e.g., +1/2 with +1/2 or −1/2 with −1/2) are forbidden by optical selection rules.

For consistency, we also use the same parameter, gCPEL, to define the quality of CP-EL. In spin-LEDs, we normally define the degree of circular polarization as DOCP, which relates with gCPEL as,

The DOCP value in spin-LED is directly related to the relative populations of the electron spin states and the degree of quantum confinement in semiconductors (if we exclude spin relaxation)43.

Where, 0.5 ≤ α ≤ 1, \(n\uparrow\) and \(n\downarrow\) are the relative population of the electrons with different spin states mj = +1/2 and mj = −1/2, respectively. The spin populations satisfy the conditions \(0\le {\rm{n}}\le 1\), and \(n\uparrow +{n}\downarrow \,=\,1\). Therefore, the maximum |DOCP|max equals to \(\alpha\), if spin relaxation is not considered. In the case of weak confinement (Fig. 1d), where the HH and LH bands are degenerate in energy, α = 0.5 due to the 3:1 ratio of transition probabilities favoring the HH sub-band over the LH sub-band (Fig. 1d). The maximum circular polarization |DOCP|max is 0.5 and the maximum attainable value of gCPEL in this case is 1.

In situations with strong quantum confinement, for example quantum wells or quantum dots, the HH-LH band degeneracy is lifted (Fig. 1e)44. The LH bands are at lower energy levels. In this case, only the HH bands participate in the radiative recombination process (Fig. 1e), and α is estimated to be 1. In this case, the maximum circular polarization |DOCP| is 1 and the maximum attainable value of gCPEL is 2 under the HH-LH non-degenerate condition43.

When spin relaxation is considered, the |DOCP| is also related to the spin injection efficiency (Pinj) through45,46

where F is a renormalization factor that quantifies the fraction of spin-polarized carriers that recombine radiatively before losing their spin polarization. F is defined as F = 1/(1 + τ/τs), where τ is the total carrier lifetime and τs is the spin lifetime of the semiconductors. The spin injection efficiency Pinj depends on the interface between the spin injector and the semiconductor. To achieve a high |DOCP|, it is critical to obtain a short total carrier lifetime, a long spin lifetime and a high spin injection efficiency. Below we introduce the most common strategies for spin polarization injection in spin-LEDs.

Mechanism of spin polarization in spin injectors

Dilute magnetic semiconductor (DMS)

DMS are semiconductors containing a small amount of magnetic dopants, such as Mn2+ (Fig. 2a)47. The low (dilute) concentration of magnetic dopant can introduce ferromagnetism in DMS48, which arise from half-filled 3d⁵ shell of localized Mn²⁺ ions, and their interaction with the conduction electrons of the semiconductor through exchange interactions. Well-known examples of DMS include Ga1-xMnxAs49, Cd1-xMnxSe50, where x is generally in the range of 0.01–0.1. Under an applied magnetic field, the conduction and valence bands of DMS split into Landau levels, which further split into spin-dependent sublevels, resulting in a large energy difference between spin-up and spin-down states (i.e., Giant Zeeman Effect). At sufficiently low temperatures, the energy splitting is so significant that only one spin state is populated, leading to a spin-polarized band structure (Fig. 2b)51. By injecting the spin-polarized electrons into a LED, these spin-polarized electrons can be utilized to emit CP-EL19,52. The highest reported DOCP was achieved using a ZnMnSe spin injector by Asshoff et al., who obtained a DOCP of 96% at 5 K under an external magnetic field of 6 T53. One of the major limitations of DMS materials is their low Curie temperature (Tc), which makes them unsuitable for practical applications at room temperature. Below Tc, the DMS remains in a ferromagnetic phase, enabling efficient spin polarization and spin injection in spin-LEDs. However, near or above Tc, other magnetic phases such as paramagnetic, antiferromagnetic, or chiral spin states may emerge. These phases lead to the injection of carriers with non-uniform or random spin polarization, ultimately resulting in an average circular polarization that approaches zero. For most traditional DMS materials, the Curie temperature is typically below 50 K. Although recent advancements have pushed the Curie temperature as high as 260 K in a new type of DMS (e.g., (Ba, K)(Zn, Mn)₂As₂54), this is still significantly lower than room temperature, limiting their usability in real-world devices.

a Schematic representation of a DMS. A non-magnetic semiconductor is doped with magnetic ions, introducing localized spin-polarized states. The exchange interactions between these spins induce ferromagnetic ordering, transforming the material into a DMS with tunable magnetic properties. b Representation of spin-polarized carrier transport in a DMS device, spin splitting in the band structure leads to asymmetric spin population under low temperature.

Ferromagnetic metals (FM)

Transition metal ferromagnets such as Fe46,55 (with ~45% spin polarization) and Co56 (~35–50%) offer high Curie temperatures (Tc > 1000 K)57, making them well-suited for practical applications. CoFe alloys58,59, and CoFeB36,45,60,61,62,63,64,65,66, which exhibit enhanced spin polarization (~50–70%)67, are widely used as spin injectors in spin-LEDs. Heusler alloys such as Co₂MnGe68, Co₂MnGa69, and Co₂FeSi70 are theoretically predicted to achieve 100% spin polarization. However, the experimentally measured DOCP from Heusler-based spin-LEDs remain lower than those achieved with transition metal-based counterparts. Up to now, the highest room temperature DOCP is reported to be 36% with CoFeB spin injector by Dainone et al.36. The pursuit of high spin polarization in FM is also closely linked to the development of two fundamental phenomena in spintronics.

Giant magnetoresistance (GMR)

Giant Magnetoresistance (GMR) is a phenomenon observed in metallic multilayers composed of alternating ferromagnetic and nonmagnetic layers. The effect arises from spin-dependent scattering of conduction electrons, which is influenced by the relative alignment of the magnetizations of the ferromagnetic layers. When the magnetizations are parallel, the majority-spin electrons encounter fewer scattering events, leading to a lower resistance. Conversely, in the antiparallel alignment, scattering increases, resulting in a higher resistance (Fig. 3)71.

Schematic illustration of spin-dependent electron transport in a ferromagnetic (F) and non-magnetic (NM) multilayered structure under parallel and antiparallel configurations. In the parallel configuration (left), the magnetizations of the F layers are aligned, allowing spin-polarized electrons to travel with minimal scattering, resulting in lower resistance. In the antiparallel configuration (right), alternating magnetization directions cause increased spin scattering, leading to higher resistance.

Spin-dependent scattering in ferromagnetic materials is governed by the asymmetry in the DOS at the Fermi level for spin-up and spin-down electrons. Majority-spin electrons, which correspond to the spin state with a higher DOS, experience a weaker scattering and show longer mean free paths. Minority-spin electrons, with lower DOS, encounter a stronger scattering, leading to shorter mean free paths. The spin dependent differential scattering effect enables significant changes in spin dependent electrical resistance.

Tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR)

Tunneling Magnetoresistance (TMR), first demonstrated by Julliere in 197572 and observed at room temperature by Miyazaki and Moodera71,73, occurs in magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs). An MTJ consists of two ferromagnetic layers separated by a thin insulating barrier. The resistance of this structure depends on the relative alignment of the magnetizations in the ferromagnetic layers: resistance is lower when the magnetizations are aligned parallelly and higher when they are antiparallelly.

The mechanism of TMR is governed by spin polarization at barrier/ferromagnet interface, where spin-up and spin-down electrons at the Fermi level have unequal densities of states74. This imbalance creates a preferential tunneling for one spin orientation. When a voltage is applied across the MTJ, electrons tunnel through the insulating barrier via quantum mechanical effects. In the parallel configuration, the alignment of the magnetizations of both ferromagnetic layers enhances the available density of states (DOS) for majority-spin electrons (occupied and unoccupied) in each layer, favoring efficient tunneling and resulting in a lower resistance (Fig. 4a). In the antiparallel configuration, majority-spin electrons in one layer correspond to minority-spin electrons in the other, leading to reduced tunneling probabilities and a higher resistance (Fig. 4b)71,73,75,76.

a Parallel configuration, where the magnetizations of the two FM layers (FM1 and FM2) are aligned, leading to lower resistance and higher tunneling probability for majority spin carriers. b Antiparallel configuration, where the magnetizations are opposite, increasing resistance and reducing tunneling efficiency due to the density of states (DOS) mismatch. The energy band diagrams below depict the spin-dependent DOS and tunneling probabilities for each configuration.

Spin Hall effect (SHE)

Despite the success of FM in polarizing electron spins, these injectors face significant challenges for practical applications in thin, portable spin-LEDs. Their reliance on external magnetic fields to manipulate the magnetization of ferromagnetic layers limits the utility in applications. A promising alternative is the Spin Hall Effect (SHE), first proposed by Dyakonov and Perel in 197177. They predicted that in materials with strong relativistic SOC, an unpolarized electrical current could generate a transverse spin current, enabling spin polarization without the need for an external magnetic field (Fig. 5a). There are two main mechanisms of the SHE, i.e., Extrinsic SHE and Intrinsic SHE. The extrinsic SHE arises from Mott scattering, where electrons with opposite spins scatter in opposite directions upon colliding with impurities in the material77. This spin-dependent scattering leads to the spin separation. The intrinsic SHE originates from the band structure of materials and is most prominent in systems with strong SOC and broken structural inversion symmetry78. In such systems, the Rashba spin-orbit interaction arises due to the lack of structural inversion symmetry, and induces spin-momentum locking, where the electron’s spin orientation is always aligned perpendicular to its momentum.

a Schematic representation of the SHE, where a charge current (Jc) induces a transverse spin current (Js), leading to spin accumulation at the edges of the material. b Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the SHE spin-LED device, showing a 1.5 μm channel with two light-emitting diodes (LED 1 and LED 2) used for CPL emission. A polarization current (Ip) is applied to control spin injection. c CP-EL spectra from LED 1 and LED 2 for opposite polarization currents (+Ip and −Ip), demonstrating spin-dependent light emission. [b, c are adapted from ref. 84. with permission].

When an electrical current is applied to the material, it drives the electrons through the system. As a result of spin-momentum locking, electrons with opposite spins are naturally deflected in the opposite directions as they move. This behavior is analogous to the Magnus force in classical mechanics, where the spin of a ball distorts its trajectory. In the SHE, this deflection causes spin-up electrons to accumulate on one edge of the material and spin-down electrons on the opposite edge, resulting in spin polarization along the lateral edges of the material (i.e., a spin current perpendicular to charge current). Traditionally, the SHE has been observed primarily in inorganic materials, as it typically requires strong SOC associated with heavy atoms. However, recent experimental and theoretical studies have predicted that the effective SOC in organic molecules can be enhanced through structural modifications, such as incorporating metal atoms like Cu and Al into the molecular framework79,80,81,82.

A major advantage of the SHE is that it does not require a ferromagnetic material to generate spin polarization, making it particularly promising for practical applications in spintronic devices. In 2005, Wunderlich et al.67 and Nomura et al.66 demonstrated the intrinsic SHE by constructing a micro-LED with a coplanar p-n junction in (Al,Ga)As/GaAs heterostructure incorporating a two-dimensional hole gases (2DHG, Fig. 5b)83,84. A p-channel current (Ip = 100 μA) applied along the x-direction deflected carriers with opposite spins to opposite edges of the 2DHG, creating spin polarization optically detected as CPL emitted from biased LEDs. The CPL’s polarization flipped when Ip was reversed. The device achieved 1% DOCP at room temperature without a magnetic field (Fig. 5c), but this remains the only reported use of SHE in spin-LEDs.

Electronically modulated polarization switching

One key advantage of spin-LEDs over CP-LEDs is the ability to electrically control the helicity of CPL. In spin-LEDs, polarization is determined by the spin states of injected carriers, rather than by the intrinsic chirality of the emissive layer, which is fixed and cannot be easily modulated externally. This capability is particularly significant for information processing, as conventional data transmission methods rely on intensity modulation—encoding information through the binary ON/OFF states of optical and electrical signals. In contrast, utilizing angular momentum modulation—switching between σ⁺/σ⁻ CPL states for information encoding presents the potential for substantially higher data transmission rates compared to intensity modulation. This advantage arises from the inherently faster transition dynamics of polarization states compared to intensity modulation85. Notably, birefringent spin lasers have already demonstrated polarization oscillation at speeds 10 times faster than those achieved through intensity modulation86.

The feasibility of dynamically controlling CPL polarization in spin-LEDs was first demonstrated by Nishizawa et al.87, who designed a device incorporating two electrodes with opposite spin polarizations—one injecting spin-up carriers and the other spin-down carriers—into a common emissive layer (Fig. 6a). By applying an alternating current between these electrodes, they successfully achieved CPL polarization switching at frequencies of up to 1 kHz.

a Schematic illustration of spin-LED device by Nishizawa et al. with dual spin-polarized electrodes enabling electrical control of CPL. By applying an alternating current between the two oppositely magnetized electrodes, the CPL helicity can be dynamically switched. b Schematic illustration of electrical control of CPL via the spin Hall effect. A pulsed current in the Hall-bar-shaped spin injector alters the magnetization direction, which in turn determines the polarization of the light emitted by the spin LED. [a is replotted from data in ref. 87].

However, this approach is inherently complex due to the requirement for two distinct spin-polarized electrodes and an alternating current drive. More recently, in 2024, Dainone et al. demonstrated an alternative method for electrically switching CP-EL polarization via magnetization control36. Their approach leverages the spin Hall effect, wherein a charge current pulse passing through a heavy metal generates a transverse spin current, with spin-up and spin-down carriers propagating in opposite directions perpendicular to the applied current. In their study, the spin current in tantalum (Ta) is sufficiently strong to induce magnetization switching in an adjacent ferromagnetic layer (CoFeB)88, thereby modulating the spin polarization of injected charge carriers (Fig. 6b). As a result, they achieved reversible CPL polarization switching, with gCPEL tunable between +0.23 and −0.25, all without the need for an external magnetic field. Under a small magnetic field, they can achieve an even larger CP-EL switching (gCPEL = ±62%). Their study represents a significant advancement in electrically controlled spin-LEDs.

Fundamental challenges

Table 1 summarizes the key advantages, main limitations and highest achieved spin polarization and DOCP of different spin polarization mechanisms. Although DMS injectors demonstrate high spin injection efficiency due to the ohmic contact on semiconductors19,43,53,89,90, their low Curie temperature prevents operation at room temperature. Despite the progress in spin polarization in FM and spin-dependent transport mechanisms such as GMR, TMR and SHE, a critical obstacle remains in their practical application through spin injection: the conductivity mismatch at the interface between ferromagnetic metals and semiconductors20. The significant difference in electrical conductivity between the two materials severely limits the efficiency of spin injection. Consequently, the efficiency of spin-LEDs based on ferromagnetic metals remains relatively limited.

Several strategies have been proposed to mitigate the conductivity mismatch, most notably by introducing Schottky barriers91,92,93 or thin tunneling barriers (Al2O356,94,95,96 or MgO46,58,60,62) at the interface between the metal and the semiconductor. Schottky barriers rely on the creation of a depletion region at the interface, which facilitates spin injection through quantum tunneling. These approaches provide partial solutions to the conductivity mismatch issue by eliminating direct contact of metal on semiconductor but fail to fully overcome their intrinsic limitations.

In addition, to achieve CPL emission in Faraday geometry (surface emitting) without applying an external magnetic field, the spin injector must possess perpendicular magnetic anisotropy63. This poses a challenge, as most ferromagnetic injectors exhibit in-plane magnetization. Special structure design should be taken into account to fabricate perpendicular magnetized spin injectors45,64,65,66.

Additionally, the tunneling barrier often requires sophisticated and expensive ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) fabrication, such as molecular beam epitaxy or sputtering62, which can increase costs and potentially compromise device performance. All these constraints create a strong incentive to explore alternative mechanisms.

Emergence of chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS)

Recently, Chiral-Induced Spin Selectivity (CISS), has emerged as a new paradigm for spin polarization at room temperature. CISS effect does not require the use of any ferromagnetic materials or external magnetic fields. More importantly, CISS materials can be semiconducting and form ohmic contact on semiconductors, thus eliminating the obstacle of conductivity mismatch.

The CISS effect enables spin manipulation through the interaction between electron spin and the chirality of materials. This effect is generally understood as a result from the electron motion in a chiral potential, which favors one spin orientation over the other97,98,99. In a chiral system, the symmetry of electron motion is broken, and the electron’s spin state becomes correlated with its momentum and the applied electric field. This occurs because spin, electron momentum, and the electric field direction are mutually orthogonal, causing spin polarization to emerge naturally in chiral materials. The handedness of the material determines the preferred spin orientation, generating an effective magnetic field that stabilizes one spin state while suppressing the opposite one100. This selective stabilization of spin is the hallmark of the CISS effect (Fig. 7a).

a Schematic illustration of CISS. When electrons move through a chiral potential field, they generate an effective magnetic field that acts on the electrons, stabilizing one spin direction. p is the pitch of chiral potential. b Energy distribution as photoelectrons injected (i) L, C-terminus connected, (ii) D, N-terminus connected, and (iii) D, C-terminus connected helical polyalanine films using a left (negative spin polarization; red, solid) or right circularly polarized laser (positive spin polarization; blue, dashed). Or linearly (no spin polarization; black, dotted) light. c Current–voltage curves of helical self-assembled polyalanine molecules monolayers (top) and its cluster (down) adsorbed on magnetic Au/Co/Au substrates. [a, b are adapted from ref. 113, and c is adapted from ref. 114. with permission].

The CISS effect has been widely observed in structured arrays of chiral organic molecules, including helicenes101,102, DNA103,104,105, oligopeptides106,107, proteins108,109 and polymers110,111,112, with reported spin polarization values ranging from 30 to 60%, depending on the specific molecular system, structure, alignment, and degree of order.

The spin filtering efficiency via the CISS effect is highly sensitive to molecular orientation, structural organization and alignment. For example, Naaman et al. demonstrated that the spin selectivity of poly-D-alanine varies based their relative orientation to a substrate (attached via C- or N-terminal) (Fig. 7b)113. Nguyen et al. found that self-assembled polyalanine arrays exhibited higher spin polarization (75%) compared to chiral polyalanine clusters (60%), highlighting the importance of structural order and molecular alignment in optimizing spin transport (Fig. 7c)114.

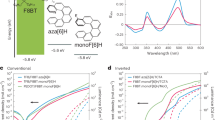

Observation of CISS in chiral metal-halide semiconductors

CISS also occurs in a variety of chiral self-assembled materials, including hybrid thin films composed of organic and inorganic layers (>99%)115, metal-organic frameworks formed by metal ions coordinated to organic linkers (MOFs, >99%)116, and metal-halide semiconductors comprised of periodic arrangement of metal-halide octahedra (MHSs) (>90%)22,117,118. Among these chiral materials, chiral MHSs, first reported by Billings et al. in 2017, have emerged as highly promising materials due to their unique chiroptical and spin-selective characters21,119, and outstanding optoelectronic properties120. Chiral MHSs typically adopt low-dimensional structures with a chemical formular of A₂BX₄ (2D) or ABX₃ (1D), where A represents a chiral organic cation, B is a divalent metal cation (e.g., Pb²⁺, Sn²⁺), and X is a halide anion (e.g., Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻)121,122. By selecting combinations of cation and anion, chiroptical properties such as circular dichroism (CD), circularly polarized luminescence, and spin selectivity via the CISS effect can be precisely controlled99. In 2D chiral MHS films, the metal–halide planes are oriented parallelly to the substrate, while the chiral organic molecules align perpendicularly, forming highly uniform, low-roughness layers. Their well-ordered structure enables efficient spin-polarized electron transport and can function as intrinsic spin filters through CISS without the need for magnetic components.

In 2019, Lu et al. first demonstrated that charge transport in 2D chiral (MBA)₂PbI₄ perovskites (MBA = methylbenzyl ammonium) (Fig. 8a) is highly spin dependent22. The spin transport property is directly dictated by the handedness of the organic ligands, achieving a spin polarization of up to 86% as shown by the difference in current in Fig. 8b, in which much higher current is measured when the tip is magnetized in the “up” direction versus that in the “down” direction. That is, carriers with their spin oriented parallel to the tip magnetization direction are preferentially transferred from the (R-MBA)2PbI4 film to the magnetized tip over those with antiparallel spin orientation. The opposite behavior is observed for the (S-MBA)2PbI4 film, where higher current is observed when the tip is magnetized in the down direction as compared to the up direction (Fig. 8c). Notably, this spin selectivity surpasses that observed in previously reported chiral self-assembled molecular arrays. Building on this work, Lu et al. reported in 2021 that 2D chiral (MBA)₂SnI₄ perovskites achieved a record 94% spin polarization123. Interestingly, the minimal variation in spin-polarized current between these two systems suggests that spin dephasing does not play a significant role in the MHSs. Instead, the exceptionally high spin polarization is primarily attributed to the spin-filtering effect induced by the oriented chiral organic molecules.

a Structure of 2D MHSs, (R/S-)methylbenzylammonium lead iodide (R/S-MBA)2PbI4. Current–voltage curves of chiral b (R-MBA)2PbI4 and c (S-MBA)2PbI4 thin films on a fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrate measured by a conductive-probe atomic force microscope. The difference in bias-dependent current indicate the highly spin selective for the chiral (MBA)2PbI4 thin films. [Adapted from ref. 22. with permission].

Demonstration of CISS in spin-LEDs

spin-LEDs based on a bilayer structure

Recognizing the potential of chiral MHSs for spintronic applications, Beard and coworkers developed the first CISS-enabled spin-LED in 2021, incorporating a 2D chiral (R/S-MBA)₂PbI₄ layer as the spin-injection layer (Fig. 9a)21. Specifically, the chiral MHS layer acts as a spin-polarization layer to generate spin-polarized holes. These holes are then transported into the non-chiral, light-emitting perovskite nanocrystal emissive layer, where they recombine with electrons. Notably, the handedness of the chiral MHS layer fully determines the polarization of the emitted CP-EL. Their spin injection efficiency of 86% significantly surpasses conventional spintronic injection methods. A key finding of their study is the direct correlation between \({g}_{{CPEL}}\) and the spin lifetime \({\tau }_{s}\) of the non-chiral emitting layer. When the CsPbI₃ nanocrystal emission layer was replaced with CsPb(Br₀.₁I₀.₉)₃ nanocrystals, the spin lifetime increased from 4 ps to 14 ps, leading to a 10 fold enhancement of \({g}_{{CPEL}}\) at room temperature.

a Schematic illustration of a spin LED device. using 2D chiral perovskite (R- or S-MBA)2PbI4 as spin filtering, non-chiral CsPbI3 nanocrystals as light-emitting layer; spin-polarized holes are injected at the interface. bPCP-EL of the CISS layer/mixed halide perovskite NC heterostructure. c The same 2D perovskite acts as a spin filter, allowing only spin-polarized holes (blue circles) to move through the LED and recombine in the AlGaInP multiple quantum well emitting CP-EL (yellow helix). d Circularly polarized transient absorbance determines the spin lifetime of carriers in the AlGaInP multiple quantum well. e DOCP of the CISS layer/Multiple quantum well structure. [a, b are adapted from ref. 21, c–e are adapted from ref. 119. with permission].

Subsequent demonstration were shown by Wang and coworkers, where 2D chiral perovskites were used to inject spin-polarized carriers to the CdSe/ZnS quantum dots layer, generating CP-EL124. Chiral metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) can also lead to spin injection in spin-LEDs125. Mustaqeem et al. integrated a chiral MOF layer with CdSe/ZnS quantum dots, where spin-polarized holes influence both the polarization direction and intensity of CP-EL, achieving a gCPEL of 12.24%.

Recently, Beard and coworkers utilized (R/S-MBA)₂PbI₄ to inject spin-polarized carriers to a commercially relevant (Al₀.₃₂Ga₀.₆₈)₀.₅In₀.₅P multiple quantum wells and successfully demonstrated efficient spin-LEDs at room temperature (Fig. 9b). A key advantage of this design is that it eliminates tunneling barriers at the perovskite/III–V semiconductor interface, ensuring efficient spin injection. In their device, spin-polarized carriers were successfully injected across the chiral perovskite/III–V interface, leading to the spin accumulation in the emitting layer. This results in a gCPEL of up to 0.3 ± 0.08. The enhanced gCPEL was attributed to the longer spin lifetime of (Al₀.₃₂Ga₀.₆₈)₀.₅In₀.₅P (τs = 100 ps) compared to their previous CsPb(Br₀.₁I₀.₉)₃ (τs = 14 ps) (Fig. 9c). Their study demonstrates that chiral hybrid perovskites can be directly integrated with traditional semiconductors, functioning as an integral part of the device stack. By incorporating chiral MHSs, conventional III–V LEDs, which are typically designed for light-charge conversion, can be transformed into devices that also enable spin-to-light conversion, significantly expanding their functionality119.

spin-LEDs based on a spin bulk-heterojunction (spin-BHJ)

In addition to the classical bilayer structure enabled by CISS effect, spin-LEDs can also be fabricated by a single-layer structure where spin transfer occurs within the emitting layer. For instance, Xiao and co-workers used core-shell MAPbBr₃ nanocrystals126 with a chiral perovskite shell as the emitting layer to fabricate green spin-LEDs. They proposed that the chiral shell enabled the injection of spin-polarized electrons into the achiral core, yielding a gCPEL of 2.16 × 10⁻³. Moon’s group improved this approach with CsPbBr₃ nanocrystals, reaching a higher gCPEL of 0.24127. Since the emissive layers in these reports are also chiral, it is unclear whether the circularly polarized luminescence stems from spin polarization within the emissive layer or is simply due to the chiral optical transitions or light propagation. That is, it is under debate if these should be categorized as “CP-LED” or “spin-LED”.

Recently, Lu and coworkers showed that an ultrafast spin transfer process occurs in quasi-2D chiral perovskites128. They proposed a spin bulk-heterojunction (spin-BHJ) concept when spin polarization and spin transfer occur within a chiral 2D/3D perovskite layer. They showed that an ultrafast energy and spin funneling process from 2D to 3D perovskites can generate spin-polarized excitons in 3D phase (Fig. 10b), giving rise to circularly polarized luminescence. The fabricated green spin-LEDs exhibited a gCPEL of 7.8×10⁻² at room temperature. By tuning the halide composition, the authors extended the emission wavelength to the near-infrared (NIR) region, achieving a maximum gCPEL of 1.48 × 10⁻² at room temperature129. Their works show that the performance of CP-EL is directly related to the spin transfer and spin lifetime of chiral perovskites, indicating the important role of spin states. Along this direction, several groups have further optimized quasi-2D perovskites for spin-LED applications. Xiao’s group developed mixed-ligand quasi-2D perovskites, achieving room-temperature CP-EL in green to deep blue region, and a maximum gCPEL value of 0.175130. Similarly, Yang’s group fabricated red-emissive spin-LED with engineered passivation, achieving a maximum gCPEL of around 4 × 10⁻³131. Wang and coworkers introduced chiral ionic liquids as additives in lead bromide-based achiral hybrid perovskites, resulting in spin-LEDs with a gCPEL value of 0.26132. While these LEDs devices can successfully generate high performance CP-EL, the exact mechanism and the underlying role of spin polarization and CISS effect require further investigation. Whether describing these LEDs as CP-LED or spin-LED remains to be further addressed.

a Schematic illustration of the structure of quasi-2D perovskite with n = 1-\(\infty\). b Illustration of the energy and spin funneling process, which transfers spin-polarized excitons from a 2D to a 3D perovskite phase. The CISS effect generates spin polarization in excitons within chiral 2D perovskites. These spin-polarized excitons are then sequentially transferred to thicker quasi-2D perovskite layers, acting as a funnel for both energy and spin between 2D and 3D phases. This process results in a long-lived spin polarization in the final state. [Adapted from ref. 128. with permission].

Future perspective

The development of spin-LEDs has advanced significantly in recent years, particularly with the integration of spin-Hall effect and CISS effect. The use of solution-processable chiral perovskites has enabled an efficient spin injection without the need for ferromagnetic electrodes, addressing a major limitation in conventional spin-LED devices. While the spin polarization in CISS spin-LEDs is determined by the fixed handedness of the chiral spin-polarizing layer, tunability can be realized by different chiral layers, giving rise to various degrees of spin polarization. In addition, recent studies show that the tailored chiral organic components can be used to construct chiral systems that can be controlled through external stimuli, such as light and/or temperature133,134, which may be further used to realize bi-polarization spin-LEDs.

However, critical challenges remain that must be overcome before spin-LEDs can be used in practical applications.

One of the primary challenges is maintaining spin polarization throughout the device. While chiral materials have demonstrated efficient spin injection, minimizing spin relaxation losses remains a key hurdle. Notably, despite the high spin polarization and injection efficiency, the gCPEL of the device is ultimately constrained by the spin lifetime in the emissive layer. Extending this spin lifetime through improved emissive layer design will be crucial for enhancing overall device performance.

Another major challenge is the stability and scalability of chiral spintronic materials. Many chiral perovskites, despite their promising optical and spin properties, suffer from environmental instability, which limits their long-term performance. Developing more stable material compositions and protective encapsulation strategies will be essential for integrating spin-LEDs into commercial devices. Additionally, current fabrication methods for chiral spin-LEDs are often limited to small-scale short-term demonstrations. Scalable production techniques must be developed to ensure compatibility with conventional semiconductor manufacturing.

In conclusion, while spin-LEDs based on CISS materials represent a breakthrough in spintronic optoelectronics, further research is needed to enhance device stability and ultimately increase both the efficiency and gCPEL of these devices. By addressing these challenges, the field can move closer to realize practical, high-performance spintronic light sources with real world applications.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Wang, Z. Y. Processable circularly polarized luminescence for the synthesis of chiral plasmonic nanoparticles. Adv. Opt. Mater. 13, 2402310 (2025).

Zhang, M. J. Processable circularly polarized luminescence material enables flexible stereoscopic 3D imaging. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi9944 (2023).

Service, R. F. Ultrafast lasers—lighting the way to a quantum computer. Science 292, 2412–2413 (2001).

Sherson, J. F. Quantum teleportation between light and matter. Nature 443, 557–560 (2006).

Li, W. Circularly polarized light detection with hot electrons in chiral plasmonic metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 6, 8379 (2015).

Zhou, K. H., Hu, X. Y., Chen, G. Y., Xu, D. D. & Xu, X. X. Circularly polarized photodetectors based on chiral moire stacking films of electrospun ZnO nanowires. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 8, 376–383 (2024).

Zhu, D. L. Organic donor-acceptor heterojunctions for high performance circularly polarized light detection. Nat. Commun. 13, 3454 (2022).

Han, D. X. Sequentially amplified circularly polarized ultraviolet luminescence for enantioselective photopolymerization. Nat. Commun. 11, 5659 (2020).

Hao, C. L. Circularly polarized light-enabled chiral nanomaterials: from fabrication to application. Nano Micro Lett. 15, 39 (2023).

Kumar, J., Nakashima, T. & Kawai, T. Circularly polarized luminescence in chiral molecules and supramolecular assemblies. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 3445–3452 (2015).

Tao, L. T., Zhan, H. M., Cheng, Y. X., Qin, C. J. & Wang, L. X. Enhanced circularly polarized photoluminescence of chiral perovskite films by surface passivation with chiral amines. J. Phys Chem. Lett 14, 2317–2322 (2023).

Yang, D., Duan, P. F., Zhang, L. & Liu, M. H. Chirality and energy transfer amplified circularly polarized luminescence in composite nanohelix. Nat. Commun. 8, 15727 (2017).

Nuzzo, D. Circularly polarized photoluminescence from chiral perovskite thin films at room temperature. ACS Nano 14, 7610–7616 (2020).

Li, M. & Chen, C. F. TADF-sensitized fluorescent enantiomers: a new strategy for high-efficiency circularly polarized electroluminescence. Chem. Eur. J. 28, 5–9 (2022).

Liao, X. J. Planar chiral multiple resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for efficient circularly polarized electroluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, 202217045 (2023).

Peeters, E. Circularly polarized electroluminescence from a polymer light-emitting diode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 9909–9910 (1997).

Deng, Y. J. Circularly polarized luminescence from organic micro-/nano-structures. Light Sci. Appl 10, 76 (2021).

Datta, S. & Das, B. Electronic analog of the electro-optic modulator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 56, 665–667 (1990).

Fiederling, R. Injection and detection of a spin-polarized current in a light-emitting diode. Nature 402, 787–790 (1999).

Schmidt, G., Ferrand, D., Molenkamp, L. W., Filip, A. T. & Wees, B. J. Fundamental obstacle for electrical spin injection from a ferromagnetic metal into a diffusive semiconductor. Phys. Rev. B 62, 4790–4793 (2000).

Kim, Y. H. Chiral-induced spin selectivity enables a room-temperature spin light-emitting diode. Science 371, 1129–1133 (2021).

Lu, H. P. Spin-dependent charge transport through 2D chiral hybrid lead-iodide perovskites. Sci. Adv. 5, eaay0571 (2019).

Schellman, J. A. Circular-dichroism and optical-rotation. Chem. Rev. 75, 323–331 (1975).

Kubo, H. Tuning transition electric and magnetic dipole moments: helicenes showing intense circularly polarized luminescence. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 686–695 (2021).

Geng, Y. H. Synthesis, characterization, and optical properties of monodisperse chiral oligofluorenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 8337–8347 (2002).

Nuzzo, D. High circular polarization of electroluminescence achieved self-assembly of a light-emitting chiral conjugated polymer into multidomain cholesteric films. ACS Nano 11, 12713–12722 (2017).

Yang, L. Doping-free circularly polarized electroluminescence of AIE-active chiral binaphthyl-based polymers. Chem. Commun. 54, 9663–9666 (2018).

Yang, Y., da Costa, R. C., Smilgies, D.-M., Campbell, A. J. & Fuchter, M. J. Induction of circularly polarized electroluminescence from an achiral light-emitting polymer via a chiral small-molecule dopant. Adv. Mater. 25, 2624–2628 (2013).

Fu, G. R. Efficient polymer light-emitting diodes (PLEDs) based on chiral [Pt(C∧N)(N∧O)] complexes with near-infrared (NIR) luminescence and circularly polarized (CP) light. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 13743–13747 (2019).

Chen, Y. H. Strong circularly polarized electroluminescence based on chiral salen-Zn(ii) complex monomer chromophores. Mater. Chem. Front 3, 867–873 (2019).

Zhou, Y. H. Circularly polarised photoluminescence and electroluminescence of chiral copper(i) dimers based on R/S-2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthalene ligands. J. Mater. Chem. C. 11, 1329–1335 (2023).

Zinna, F. Design of lanthanide-based OLEDs with remarkable circularly polarized electroluminescence. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 201603719 (2017).

Imagawa, T., Hirata, S., Totani, K., Watanabe, T. & Vacha, M. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence with circularly polarized luminescence characteristics. Chem. Commun. 51, 13268–13271 (2015).

Li, M., Wang, Y. F., Zhang, D., Duan, L. & Chen, C. F. Axially chiral TADF-active enantiomers designed for efficient blue circularly polarized electroluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 3500–3504 (2020).

Wang, Y. X. Circularly polarized electroluminescence of thermally activated delayed fluorescence-active chiral binaphthyl-based luminogens. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter 11, 26165–26173 (2019).

Dainone, P. A. Controlling the helicity of light by electrical magnetization switching. Nature 627, 783–788 (2024).

Hu, C. et al. Room temperature spin diffusion in (110) GaAs/AlGaAs quantum wells. Nanoscale Res Lett. 6, 149 (2011).

Dash, S. P., Sharma, S., Patel, R. S., de Jong, M. P. & Jansen, R. Electrical creation of spin polarization in silicon at room temperature. Nature 462, 491–494 (2009).

Wang, G. et al. Gate control of the electron spin-diffusion length in semiconductor quantum wells. Nat. Commun. 4, 2372 (2013).

Zucchetti, C. et al. Doping dependence of the electron spin diffusion length in germanium. APL Mater. 7, 101122 (2019).

Weisbuch, C. & Vinter, B. Quantum Semiconductor Structures: Fundamentals and Applications (Academic Press, 1991).

Meier, F. & Zakharchenia, B. P. Optical orientation (Elsevier Science Pub. Co, 1984).

Jonker, B. T. Robust electrical spin injection into a semiconductor heterostructure. Phys. Rev. B 62, 8180–8183 (2000).

Katsaros, G. Zero field splitting of heavy-hole states in quantum dots. Nano Lett. 20, 5201–5206 (2020).

Giba, A. E. Spin injection and relaxation in-doped (In, Ga)As/GaAs Quantum-dot spin light-emitting diodes at zero magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Appl 14, 034017 (2020).

Etou, K. Room-temperature spin-transport properties in an InGaAs quantum dot spin-polarized light-emitting diode. Phys. Rev. Appl 16, 014034 (2021).

Munekata, H. Diluted magnetic III-V semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 63, 1849–1852 (1989).

Jungwirth, T. Character of states near the Fermi level in (Ga,Mn)As: impurity to valence band crossover. Phys. Rev. B 76, 125206 (2007).

Ohno, H. (Ga,Mn)As: a new diluted magnetic semiconductor based on GaAs. Appl. Phys. Lett 69, 363–365 (1996).

Nazir, S. Spin-polarized structural, electronic, and magnetic properties of diluted magnetic semiconductors Cd1−xMnxS and Cd1−xMnxSe in zinc blende phase. J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 6022–6027 (2009).

Dietl, T. & Ohno, H. Dilute ferromagnetic semiconductors: physics and spintronic structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 187 (2014).

Ohno, Y. Electrical spin injection in a ferromagnetic semiconductor heterostructure. Nature 402, 790–792 (1999).

Asshoff, P., Merz, A., Kalt, H. & Hetterich, M. A spintronic source of circularly polarized single photons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 112106 (2011).

Peng, Y. A near room temperature curie temperature in a new type of diluted magnetic semiconductor (Ba,K)(Zn,Mn)2As2. Adv.Phys. Res 4, 240012 (2025).

Etou, K. et al. Efficient room-temperature operation of a quantum dot spin-polarized light-emitting diode under high-bias conditions. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 024055 (2023).

Lombez, L. Electrical spin injection into p-doped quantum dots through a tunnel barrier. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 081111 (2007).

Chrobok, G., Hofmann, M., Regenfus, G. & Sizmann, R. Spin polarization of field-emitted electrons from Fe, Co, Ni, and rare-earth metals. Phys. Rev. B 15, 429–440 (1977).

Jiang, X. Highly spin-polarized room-temperature tunnel injector for semiconductor spintronics using MgO (100). Phys. Rev.Lett 94, 056601 (2005).

Salis, G. et al. Temperature independence of the spin-injection efficiency of a MgO-based tunnel spin injector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 262503 (2005).

Lu, Y. MgO thickness dependence of spin injection efficiency in spin-light emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 152102 (2008).

Barate, P. Electrical spin injection into InGaAs/GaAs quantum wells: a comparison between MgO tunnel barriers grown by sputtering and molecular beam epitaxy methods. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 012404 (2014).

Barate, P. Bias dependence of the electrical spin injection into GaAs from Co-Fe-B/MgO injectors with different MgO growth processes. Phys. Rev. Appl 8, 054027 (2017).

Liang, S. Large and robust electrical spin injection into GaAs at zero magnetic field using an ultrathin CoFeB/MgO injector. Phys. Rev. B 90, 085310 (2014).

Tao, B. Electrical spin injection into GaAs based light emitting diodes using perpendicular magnetic tunnel junction-type spin injector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 152404 (2016).

Cadiz, F. Electrical initialization of electron and nuclear spins in a single quantum dot at zero magnetic field. Nano Lett. 18, 2381–2386 (2018).

Tao, B. Atomic-scale understanding of high thermal stability of the Mo/CoFeB/MgO spin injector for spin-injection in remanence. Nanoscale 10, 10213–10220 (2018).

Huang, S. X., Chen, T. Y. & Chien, C. L. Spin polarization of amorphous CoFeB determined by point-contact Andreev reflection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 242509 (2008).

Dong, X. Y. et al. Spin injection from the Heusler alloy Co2MnGe into Al0.1Ga0.9As∕GaAs heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 102107 (2005).

Hickey, M. C. et al. Spin injection between epitaxial Co2.4Mn1.6Ga and an InGaAs quantum well. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 252106 (2005).

Ramsteiner, M. et al. Co2FeSi/GaAs/(Al,Ga)As spin light-emitting diodes: competition between spin injection and ultrafast spin alignment. Phys. Rev. B 78, 121303 (2008).

Miyazaki, T. & Tezuka, N. Giant magnetic tunneling effect in Fe/Al2O3/Fe junction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 139, 231–234 (1995).

Zhang, X. D., Li, B. Z. & Pu, F. C. Theory of spin-polarized tunneling between ferromagnetic films. Phys. Lett. A 236, 356–359 (1997).

Moodera, J. S., Kinder, L. R., Wong, T. M. & Meservey, R. Large magnetoresistance at room-temperature in ferromagnetic thin-film tunnel-junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3273–3276 (1995).

Lewis, S. P., Allen, P. B. & Sasaki, T. Band structure and transport properties of CrO2. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10253–10260 (1997).

Höfener, C. Voltage and temperature dependence of the grain boundary tunneling magnetoresistance in manganites. Europhys. Lett. 50, 681–687 (2000).

Yuasa, S., Nagahama, T., Fukushima, A., Suzuki, Y. & Ando, K. Giant room-temperature magnetoresistance in single-crystal Fe/MgO/Fe magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 3, 868–871 (2004).

Dyakonov, M. I. & Perel, V. I. Current-induced spin orientation of electrons in semiconductors. Phys. Lett. A 35, 459–460 (1971).

Manchon, A., Koo, H. C., Nitta, J., Frolov, S. M. & Duine, R. A. New perspectives for Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Nat. Mater. 14, 871–882 (2015).

Oscillating spin Hall effect from polaron transport in organic chains. Phys. Rev. B. https://journals.aps.org/prb/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevB.106.144309.

Miao, Y. et al. Dynamical study of the spin Hall effect from interchain polaron hopping in organics. Phys. Rev. B 109, 014314 (2024).

Bandyopadhyay, S. Dominant spin relaxation mechanism in compound organic semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 81, 153202 (2010).

Nuccio, L. et al. Importance of spin-orbit interaction for the electron spin relaxation in organic semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 216602 (2013).

Nomura, K. et al. Edge-spin accumulation in semiconductor two-dimensional hole gases. Phys. Rev. B 72, 245330 (2005).

Wunderlich, J., Kaestner, B., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Experimental observation of the spin-Hall effect in a two-dimensional spin-orbit coupled semiconductor system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 047204 (2005).

Faria, P. E. Toward high-frequency operation of spin lasers. Phys. Rev. B 92, 075311 (2015).

Lindemann, M. Ultrafast spin-lasers. Nature 568, 212–215 (2019).

Nishizawa, N., Nishibayashi, K. & Munekata, H. A spin light emitting diode incorporating ability of electrical helicity switching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 111102 (2014).

Liu, L. Q. Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of tantalum. Science 336, 555–558 (2012).

Löffler, W. Electrical spin injection from ZnMnSe into InGaAs quantum wells and quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 783–788 (2006).

Ghali, M. Spin injection into a single self-assembled quantum dot in a pin II-VI/III-V structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 093110 (2007).

Zhu, H. J. Room-temperature spin injection from Fe into GaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 016601 (2001).

Hanbicki, A. T., Jonker, B. T., Itskos, G., Kioseoglou, G. & Petrou, A. Efficient electrical spin injection from a magnetic metal/tunnel barrier contact into a semiconductor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 1240–1242 (2002).

Dorpe, P., Roy, W., Motsny, V. F., Borghs, G. & Boeck, J. Efficient electrical spin injection in GaAs: a comparison between AlOx and Schottky injectors. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 22, 1862–1867 (2004).

Yokota, N. Room temperature spin injection into (110) GaAs quantum wells using Fe/x-AlOx contacts in the regime of current density comparable to laser oscillation. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 163905 (2015).

Van’t Erve, O. Comparison of Fe/Schottky and Fe/Al2O3 tunnel barrier contacts for electrical spin injection into GaAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 4334–4336 (2004).

Manago, T. & Akinaga, H. Spin-polarized light-emitting diode using metal/insulator/semiconductor structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 694–696 (2002).

Yang, S. H., Naaman, R., Paltiel, Y. & Parkin, S. S. P. Chiral spintronics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 328–343 (2021).

Naaman, R., Paltiel, Y. & Waldeck, D. H. Chiral molecules and the electron spin. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 250–260 (2019).

Lu, H., Vardeny, Z. V. & Beard, M. C. Control of light, spin and charge with chiral metal halide semiconductors. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 470–485 (2022).

Evers, F. Theory of chirality induced spin selectivity: progress and challenges. Adv. Mater. 34, e2106629 (2022).

Kettner, M. Chirality-dependent electron spin filtering by molecular monolayers of helicenes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 2025–2030 (2018).

Kiran, V. Helicenes—a new class of organic spin filter. Adv. Mater. 28, 1957–1962 (2016).

Ray, S. G., Daube, S. S., Leitus, G., Vager, Z. & Naaman, R. Chirality-induced spin-selective properties of self-assembled monolayers of DNA on gold. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 036101 (2006).

Xie, Z. Spin specific electron conduction through DNA oligomers. Nano Lett. 11, 4652–4655 (2011).

Göhler, B. Spin selectivity in electron transmission through self-assembled monolayers of double-stranded DNA. Science 331, 894–897 (2011).

Kumar, A. Chirality-induced spin polarization places symmetry constraints on biomolecular interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 2474–2478 (2017).

Banerjee-Ghosh, K. Separation of enantiomers by their enantiospecific interaction with achiral magnetic substrates. Science 360, 1331–1334 (2018).

Banerjee-Ghosh, K. Long-range charge reorganization as an allosteric control signal in proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20456–20462 (2020).

Wei, J. Examining the effects of homochirality for electron transfer in protein assemblies. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 6462–6469 (2023).

Mondal, A. K. Spin filtering in supramolecular polymers assembled from achiral monomers mediated by chiral solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 7189–7195 (2021).

Jia, L., Wang, C., Zhang, Y., Yang, L. & Yan, Y. Efficient spin selectivity in self-assembled superhelical conducting polymer microfibers. ACS Nano 14, 6607–6615 (2020).

Mondal, P. C. Chiral conductive polymers as spin filters. Adv. Mater. 27, 1924–1927 (2015).

Carmeli, I., Skakalova, V., Naaman, R. & Vager, Z. Magnetization of chiral monolayers of polypeptide: a possible source of magnetism in some biological membranes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 41, 761–764 (2002).

Nguyen, T. N. H. Cooperative effect of electron spin polarization in chiral molecules studied with non-spin-polarized scanning tunneling microscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter 14, 38013–38020 (2022).

Al-Bustami, H. Atomic and molecular layer deposition of chiral thin films showing up to 99% spin selective transport. Nano Lett. 22, 5022–5028 (2022).

Huizi-Rayo, U. An ideal spin filter: long-range, high-spin selectivity in chiral helicoidal 3-dimensional metal organic frameworks. Nano Lett. 20, 8476–8482 (2020).

Wang, Q. Spin selectivity in chiral hybrid cobalt halide films with ultrasmooth surface. Small Methods 6, 2201048 (2022).

Lu, Y. Highly efficient spin-filtering transport in chiral hybrid copper halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 23578–23583 (2021).

Hautzinger, M. P. Room-temperature spin injection across a chiral perovskite/III-V interface. Nature 631, 307–312 (2024).

Shamsi, J., Urban, A. S., Imran, M., Trizio, L. & Manna, L. Metal halide perovskite nanocrystals: synthesis, post-synthesis modifications, and their optical properties. Chem. Rev. 119, 3296–3348 (2019).

Li, X., Hoffman, J. M. & Kanatzidis, M. G. The 2D halide perovskite rulebook: how the spacer influences everything from the structure to optoelectronic device efficiency. Chem. Rev. 121, 2230–2291 (2021).

Ren, H., Wu, Y., Wang, C. & Yan, Y. 2D Perovskite nanosheets with intrinsic chirality. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 2676–2681 (2021).

Lu, H. Highly distorted chiral two-dimensional tin iodide perovskites for spin polarized charge transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13030–13040 (2020).

Wang, Q. Spin quantum dot light-emitting diodes enabled by 2D chiral perovskite with spin-dependent carrier transport. Adv. Mater. 36, e2305604 (2024).

Mustaqeem, M. Solution-processed and room-temperature spin light-emitting diode based on quantum dots/chiral metal-organic framework heterostructure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 202213587 (2023).

Ye, C., Jiang, J., Zou, S., Mi, W. & Xiao, Y. Core-shell three-dimensional perovskite nanocrystals with chiral-induced spin selectivity for room-temperature spin light-emitting diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 9707–9714 (2022).

Jang, G. Core-shell perovskite quantum dots for highly selective room-temperature spin light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 36, 2309335 (2024).

Yao, J. Efficient green spin light-emitting diodes enabled by ultrafast energy- and spin-funneling in chiral perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14157–14165 (2024).

Yao, J. Efficient spin-light-emitting diodes with tunable red to near-infrared emission at room temperature. Adv. Mater 37, e2413669 (2025).

Yan, X., Cao, R., Zhang, R., Gao, H. & Xiao, Y. Mixed-ligand chiral quasi-2D perovskites for standard and deep blue CP-LEDs. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 202410012 (2024).

Yang, C. H., Xiao, S. B., Xiao, H., Xu, L. J. & Chen, Z. N. Efficient red-emissive circularly polarized electroluminescence enabled by quasi-2D perovskite with chiral spacer cation. ACS Nano 17, 7830–7836 (2023).

Tang, J. Chiral ionic liquids enable high-performance room temperature single junction spin-light emitting diodes. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2401008 (2024).

Chen, P. et al. Chirality invertible superstructure mediated active planar optics. Nat. Commun. 10, 2518 (2019).

Deng, W.-F. et al. Inversion of molecular chirality associated with ferroelectric switching in a high-temperature two-dimensional perovskite ferroelectric. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 5545–5552 (2023).

Van Dorpe, P. et al. Very high spin polarization in GaAs by injection from a (Ga,Mn)As Zener diode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3495–3497 (2004).

Ikeda, S. et al. Tunnel magnetoresistance of 604% at 300K by suppression of Ta diffusion in CoFeB∕MgO∕CoFeB pseudo-spin-valves annealed at high temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 082508 (2008).

Holber, J. Spin Hall Angles in Solids Exhibiting a Giant Spin Hall Effect. BSc thesis, Brown University (2019).

Tao, X. et al. Self-consistent determination of spin Hall angle and spin diffusion length in Pt and Pd: the role of the interface spin loss. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat1670 (2018).

Ruixian, Z. et al. High spin Hall angle in BiSb topological insulator and perpendicularly magnetized CoFeB/MgO multilayers with metallic interfacial layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 072402 (2024).

Julliere, M. Tunneling between ferromagnetic films. Phys. Lett. A 54, 225–226 (1975).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong via the General Research Fund (16300123, 16302324), Collaborative Research Fund (C1055-23G), and NSFC-RGC Joint Research Scheme (N_HKUST616/24). Y.L. acknowledges the support by the French National Research Agency (ANR) SISTER (No. ANR-11-IS10-0001) and SOTspinLED projects (No. ANR-22-CE24-0006-01) and the support by EIC Pathfinder SpinDataCom project (No. 101184694).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was first written by K.T. Chang & W. Liang and revised by Y. Lu & H. Lu.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, K.T., Liang, W., Lu, Y. et al. Principles and advances in spin light-emitting diodes. npj Spintronics 3, 44 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00107-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00107-x