Abstract

The rapid evolution of wearable and implantable electronics has driven the development of flexible magnetoelectronic devices that integrate mechanical adaptability with robust magnetic functionality. Significant progress has been achieved in areas such as flexible giant magnetoresistance sensors, magnetic tunnel junctions, anisotropic magnetoresistance devices, spin-orbit torque switching, and magnetostrictive energy harvesters. This paper reviews recent progress on the preparation method of flexible magnetic films, the strain-modulation on the physical properties of magnetic films, and existing flexible magnetoelectronic devices. Furthermore, we prospect future development trends in flexible magnetic films and devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

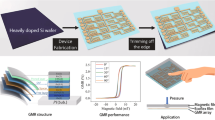

Magnetic films fabricated on rigid substrates have been widely used in various magnetoelectronic devices, including magnetic storage, magnetic sensors, and magnetic logic devices. With the rapid development of wearable devices, implantable electronics, and flexible display technologies, flexible electronic materials and devices has emerged as a new branch in electronics1,2,3,4. This trend has driven researchers to focus on flexible magnetoelectronic devices5,6, aiming to develop functional materials and devices that combine excellent magnetoelectric properties with mechanical flexibility, thereby meeting the demand for lightweight, bendable, and stretchable features in future intelligent electronic systems. Flexible spintronics not only retains the advantages of traditional spintronics that operates the degrees of freedom including charge, spin, orbital, and lattice, but also possesses the additional priority of flexibility. Flexible spintronics bridges the coupling between spintronics and mechanical properties. In 1992, Parkin et al.7 first demonstrated the sputter deposition of Co/Cu multilayers on Kapton, revealing that these films exhibit giant magnetoresistance effects comparable to films grown on silicon. This groundbreaking discovery proves the feasibility of fabricating spintronic devices on flexible substrates, paving the way for the development of bendable and conformable magnetic sensors and memory devices. When magnetic films deposited on flexible substrates are subjected to bending-induced stress from the substrate deformation, their crystal structure, magnetic domain arrangement, magnetic anisotropy, and electrical transport properties undergo significant modifications. Researchers can utilize these stress responsive characteristics to design and fabricate flexible magnetoelectronic devices including spin orbit torque devices8, anisotropic magnetoresistance devices9, giant magnetoresistance devices10, magnetic tunnel junction devices11 and energy harvesting devices12 (Fig. 1), etc.

Reproduced with permission8. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society, spin orbit torque. Reproduced with permission9. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature, anisotropic magnetoresistance. Giant magnetoresistance10, Copyright 2019, Springer Nature with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. Magnetic tunnel junction11, Copyright 2017, Springer Nature with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. Reproduced with permission12. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH, energy harvesting.

Here, we first introduce the sources of stress in flexible magnetic films, the fabrication techniques of flexible magnetic films and the parameters of commonly used flexible substrates. Subsequently, we summarize the regulation of crystal structure, magnetic anisotropy, and domain structure in flexible magnetic films under stress. This review synthesizes a body of the latest research in the flexible magnetic films and spintronic devices. It expands the discussion to include the influence of strain on skyrmions, two-dimensional magnetic materials and spin-orbit torque devices, an area not sufficiently covered in previous reviews. As a guide for the potential applications of flexible magnetic films, we provide an overview of various flexible magnetoelectronic devices. Finally, we summarize the current status and prospect future research directions.

Stress in magnetic films

The physical properties of magnetic thin films, such as magnetic anisotropy, coercivity, saturation magnetization, and domain structure, directly influence the performance of magnetoelectronic devices. For flexible magnetoelectronic devices, the key aspects are the preparation methods of the magnetic films and how stress can be used to modulate these physical properties. The sources of stress in magnetic films primarily include epitaxial strain and mechanical strain. Epitaxial strain usually arises from lattice mismatch. When a magnetic film grows on a substrate, the atomic layers of the magnetic film attempt to align with those of the substrate. If there is mismatch between the lattice constants of the magnetic film and substrate, the magnetic film suffers strain to accommodate the lattice spacing at the interface13. When the lattice constant of the magnetic film is greater than that of the substrate, the magnetic film experiences compressive stress, while tensile stress occurs if the magnetic film’s lattice constant is smaller. The magnitude of the stress depends on the degree of lattice mismatch. However, a larger mismatch can induce more defects in the magnetic film, increasing surface roughness, which is often unacceptable for magnetoelectronic devices. Moreover, the stress induced by epitaxial strain in the film is typically fixed after fabrication, which may hinder its application in certain flexible electronic devices.

To directly apply mechanical strain to magnetic thin films, they must be deposited on bendable substrates. As shown in Fig. 2, common deformation modes for inducing mechanical strain include upward/downward bending, uniaxial stretching, and wrinkling. During these deformations, the thin films experience tensile/compressive stresses, where the magnitude of stress (σ) depends on the strain (ε) and the Young’s modulus (E) of the film, following the relationship14:

Here, ts and tf denote the thicknesses of the flexible substrate and the magnetic film, respectively.

r is the bending curvature radius. For films subjected to uniaxial stretching, the induced strain can be expressed as15:

where L0 and L denote the unstretched and stretched lengths of the film, respectively. Moreover, it is possible to perform diffraction measurements to get the numerical values of stress. Some investigations have employed the X-ray diffraction (XRD) to measure lattice shifts in metallic films under strain16,17. The stress can be calculated by the following formula16:

where E is the Young’s modulus, ν is the Poisson’s ratio, d0 is the standard lattice constant, and d is the measured value. Wrinkle-induced strain patterns are typically generated using pre-stretched polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrates18,19. Metallic film is first deposited onto the pre-strained PDMS and subsequently released from the substrate, which procedure induces wrinkling into the metallic layer. The wavelength (Lw) of these wrinkles can be calculated by the following formula20:

Here, εpre and εres denote the pre-stretch strain and released strain of the PDMS substrate, respectively. The tf represents the total thickness of the metallic film. The critical strain threshold (\({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{c}}}\)) determines the onset of wrinkle formation. Wrinkles emerge only when the strain in the metallic film on PDMS exceeds this threshold. The \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{c}}}\) can be calculated using the following formula21:

Fabrication of flexible magnetic films

Flexible substrates

Flexible substrates, as the core supporting materials for flexible electronics, must balance mechanical flexibility, thermal stability, electrical insulation, and surface compatibility. For some spintronic devices, they must additionally meet demands such as low interfacial scattering and stable performance under controlled deformation. Current mainstream flexible substrates are organic polymers, including polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)22,23, polyimide (PI)8,24, PDMS17,25, polyethylene terephthalate (PEN)26,27, and polyethylene terephthalate (PET)28,29. These polymer substrates offer high bendability, lightweight properties, and low cost. Researchers have also explored mica (Mica)30,31 as a flexible substrate. Mica is a layered material with interlayer van der Waals bonding. Thin mica substrates (<100 μm thickness) can be obtained via mechanical exfoliation and exhibit excellent flexibility. To evaluate and compare the suitability of these flexible substrates for specific applications, key parameters must be considered. These include the melting point (Tm), the temperature at which a material transitions from solid to liquid; the glass transition temperature (Tg), the temperature at which a polymer changes from a hard/glassy state to a soft/rubbery state; Young's modulus (E), a measure of the stiffness of a material; and the maximum tolerable tensile and compressive stress, which indicates the maximum stress a material can withstand while being stretched or compressed before failure. A comparison of these parameters for different substrates is provided in Table 1.

Direct deposition

Depositing high quality magnetic material layers onto target flexible substrates is critical for fabricating flexible magnetic films and devices. Direct deposition involves growing source materials directly onto flexible substrates using techniques such as magnetron sputtering, electron beam evaporation, pulsed laser deposition (PLD), liquid-phase epitaxy (LPE), chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). To induce controllable stress in the magnetic films, researchers often pre-bend flexible substrates during growth. For example, Tang et al.32 deposited Co40Fe40B20 films via magnetron sputtering onto convex/concave-molded PET substrates (Fig. 3a). After deposition, the films are removed from the molds and flattened, inducing uniaxial compressive/tensile stresses. By adjusting the mold curvature, the Mr/Ms ratio of the Co40Fe40B20 films could be tuned. Some studies have directly deposited magnetic thin films on flat flexible substrates and subsequently applied tensile/compressive stresses through bending to modulate the physical properties of the magnetic films33,34. Li et al.22 deposited Co/Pt multilayers on flat PI substrates and then generated tensile and compressive stresses via the bending method illustrated in Fig. 3b, thereby modulating the magnetic domain structures and magnetic hysteresis loops of the films. Similarly, Melzer et al. 18. fabricated spin valve multilayers on Si/PDMS substrates (Fig. 3c). Random wrinkles formed within the spin valve during fabrication due to stress accumulation in the metallic buffer layer grown on PDMS. After delamination from Si, the spin valve devices could withstand tensile strains up to 40%. Mica substrates enable quasi-van der Waals epitaxial growth (Fig. 3d), where an interfacial layer forms between the substrate and deposited material. This interface layer interacts with the deposited material through directional bonds, promoting uniform epitaxial growth35. For instance, Liu et al.36 achieved van der Waals epitaxial growth of CoFe2O4 films on mica via PLD. Cross sectional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed no planar defects or grain boundaries at the CoFe2O4 mica interface (Fig. 3e).

a Schematic illustration of Co40Fe40B20 film deposition on convex/concave molds to induce tensile/compressive stresses. Reproduced with permission32. Copyright 2014, AIP Publishing. b Schematic diagrams for applying compressive stress, no stress, and tensile stress to the Co/Pt multilayers. Reproduced with permission22. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. c Fabrication process of stretchable magnetic films with random wrinkling and periodic fracture of the spin valve stack. Reproduced with permission18. Copyright 2012, Wiley-VCH. d Atomic interface of quasi-van der Waals epitaxial growth. Reproduced with permission35. Copyright 2017, Elsevier B.V. e Cross sectional TEM image of CoFe2O4 film grown on mica via van der Waals epitaxy. Reproduced with permission36. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

Researchers have achieved great success in fabricating flexible magnetic films. However, their application on flexible substrates still faces significant challenges, including poor interfacial adhesion, elastic mismatch, crack, and delamination during mechanical deformation. These factors affect the mechanical reliability and service life of flexible devices. These challenges are particularly evident under both tensile and peeling conditions. Merabtine et al. 37. investigated the damage evolution of Co₄₀Fe₄₀B₂₀ films deposited on Kapton under uniaxial tensile strain(Fig. 4a–d). They found that parallel cracks began to appear at strains exceeding ~2%, with crack density saturating at ~6% strain. Subsequently (>8% strain), buckling or blistering initiated at the edges of these cracks. The complex residual stress resulting from this crack distribution and blistering can affect the magnetic anisotropy of the films. Pandey et al. 38. discovered that during the peeling of Pt/Co and Pd/Co films, due to the extremely low adhesion energy (∼0.50 J/m² for Pt/Co and ∼0.20 J/m² for Pd/Co) between the film and the Kapton and the significant elastic mismatch, buckling, cracking, and blistering formed on the film surface (Fig. 4e–j). This structural damage alters the magnetic and electronic properties of the films. Future research could focus on developing better interface engineering strategies to enhance interfacial adhesion, suppress crack initiation, and reduce stress concentration, thereby enabling the fabrication of more robust flexible magnetoelectronic devices.

a–d Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) images of a CoFeB 20 nm-film obtained at different strain states (ε = 4–13%)37. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. e–g SEM images of flexible Pt/Co film before and after the peel test. h–j SEM images of flexible Pd/Co film before and after the peel test. Reproduced with permission38. Copyright 2025, IOP Publishing.

Indirect transfer

Indirect transfer refers to the process of first depositing magnetic films on rigid substrates, followed by releasing and transferring them to flexible substrates via physical or chemical methods. Commonly used sacrificial layers include MgO39, Sr3Al2O640,41,42, dextran15, and its derivatives. As shown in Fig. 5a–c, MgO sacrificial layers can be dissolved in 80 °C (NH4)2SO4 solution, while Sr3Al2O6 and dextran are water soluble. Lu et al.43 deposited Ca1.5Sr1.5Al2O6/SrRuO3 films on SrTiO3 substrates with [001], [110], and [111] orientations via PLD. Hydrolysis of the sacrificial Ca1.5Sr1.5Al2O6 layer enables the transfer of specific orientation SrRuO3 films to PDMS substrates (Fig. 5d). In another approach, Zhang et al.44 proposed a capillary assisted electrochemical delamination (CAED) method (Fig. 5e). Here, the anode and cathode are connected to a silicon wafer and an electrolyte solution, respectively. Anodic etching generates a gap between the PI film and silicon wafer, initiating capillary forces that drive the electrolyte into the Si/PI interface. This triggers electrochemical reactions until achieving complete delamination. Using CAED method, Li et al.24 successfully fabricated spin logic device on an ultrathin PI film (Fig. 5f).

a Dissolution of MgO sacrificial layer in (NH4)2SO4 solution. Reproduced with permission39. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. b Water soluble removal of Sr3Al2O6 sacrificial layer42. Copyright 2020, AIP Publishing with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. c Deionized water removal of dextran sacrificial layer. Reproduced with permission15. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society. d High quality single crystalline Sr3Al2O6 films obtained by dissolving the CaxSrxAl2O6 sacrificial layer43. Copyright 2022, AIP Publishing with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. e Schematic of the capillary assisted electrochemical delamination (CAED) process. Reproduced with permission44. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. f Schematic of flexible spin Hall device fabricated via the CAED method. Reproduced with permission24. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society.

Stress modulation on magnetic films

Effect of stress on the crystal structures of magnetic films

Mechanical deformation induces significant alterations in the crystalline structure of magnetic thin films due to the clamping effect. For example, Cao et al.45 fabricated bendable Cu/FeGa films (Fig. 6a). XRD spectra shows that the FeGa diffraction peak shifts towards higher angle under tensile stress. Under compressive stress, the peak first shifts towards higher angle and then towards lower angle. This is because tensile stress expands the lattice of the FeGa film along the applied stress direction. As the tensile stress increases, the contraction effect in the perpendicular direction becomes more pronounced, leading to an increase in the diffraction angle of the FeGa film. In contrast, when the FeGa film experiences a small compressive strain, the vertical direction of the film elongates, while the stress direction is compressed. As compressive strain increases, the atomic arrangement along the stress direction continues to compress, but in the perpendicular direction, it is further stretched, causing the overall lattice size of the film to increase. Zhang et al.39 observed a tetragonal distortion along the (100) direction in CoFe2O4 films on PI substrates during bending (Fig. 6b), while deformations along the (001) and (010) directions are the same. Shi et al.46 demonstrated that the positions of N atoms in Fe4N films grown on mica shift with bending curvature (Fig. 6c). Moreover, stress has a significant impact on the magnetic properties and electrical resistance of two-dimensional magnetic materials47,48,49,50. Xie et al.51 employed density functional theory (DFT) to reveal abrupt changes in interlayer magnetic coupling (ILMC) and magnetic anisotropy energy (MAE) of the van der Waals ferromagnet Fe₅GeTe₂ under strain. As shown in Fig. 6d, under 2–4% in-plane biaxial strain, the bond length between Fe5 atoms and adjacent Ge atoms changes significantly. The Te1-Fe5-Ge bond angle experiences slight perturbation within the 2–4% strain range. Similarly, Hu et al.52 investigated in-plane biaxial strain mediated magnetic tuning in monolayer Fe₃GeTe₂ (Fig. 6e). With increasing strain, the Fe1-Fe1 and Fe1-Fe3 bond lengths increase significantly, while the Fe1-Fe2 bond length decreases due to the Poisson effect. Additionally, the Fe1-Te-Fe1 and Fe1-Te-Fe3 bond angles increase with strain, while the Fe1-Ge-Fe2 bond angle decreases with increasing strain.

a Effects of tensile and compressive stress on the X-ray diffraction peaks of FeGa films. Reproduced with permission45. Copyright 2016, Springer Nature. b Schematic of the tetragonal distortion of CoFe₂O₄ films during bending. Reproduced with permission39. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. c Schematic showing the variation in the positions of N atoms in Fe₄N films with strain. Reproduced with permission46. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. d The variation of bond lengths and bond angles around Fe5 ion with in-plane strains. Reproduced with permission51. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. e Strain dependence of the distance and the Fe−Te(Ge)−Fe angle. Reproduced with permission52. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

Effect of stress on magnetic domains of magnetic films

When a magnetic thin film is subjected to external stress, a magnetoelastic coupling effect occurs, leading to corresponding strain in its crystal structure and the generation of magnetoelastic energy within the crystal. This magnetoelastic energy can be expressed by the following equation17,34:

The angle between magnetization and stress (σ) is represented by φ, and λ is the magnetostrictive coefficient of the material. As shown in Fig. 7, materials with a positive magnetostrictive coefficient (λ > 0) exhibit magnetization parallel to the stress direction (φ = 0° or 180°) when subjected to tensile stress (σ > 0). However, under compressive stress (σ < 0), the direction of magnetization becomes perpendicular to the tensile stress direction (φ = 90° or 270°). When λ < 0, the relationship between the direction of magnetization and stress is reversed compared to the above description. Researchers can effectively control the arrangement of magnetic domains in magnetic thin films through magnetoelastic coupling.

Dai et al.53 deposited FeGa films with stripe domains on pre-bent PET substrates. Due to the positive magnetostrictive coefficient of FeGa (λ > 0), when subjected to compressive stress, the internal stripe domains deflect perpendicular to the stress direction (Fig. 8a). While under tensile stress, the stripe domains deflect parallel to the stress direction (Fig. 8b). Zhang et al. utilized electron beam lithography to fabricate patterned nanotrenches on polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), and then deposited Ni films with a negative magnetostrictive coefficient (λ < 0). The stripe domains in these films are influenced by the unrelieved tensile stress along the y-direction of the nanotrenches, resulting in a perpendicular alignment to the nanotrenches (Fig. 8c)17. In contrast, stripe domains of Permalloy (λ > 0) film align parallel to the nanotrenches (Fig. 8d)54. While the studies vividly illustrate the profound influence of strain on in-plane magnetic domains, it is crucial to extend this discussion to systems with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (PMA), which are the cornerstone of modern spintronic applications. The modulation of out-of-plane magnetic domains and their dynamics by mechanical strain presents unique phenomena and opportunities55,56,57. Pandey et al.58 deposited a Ta/Pt/Co/Pt film with PMA on a PI and investigated the evolution of bubble domains under different strain states. As observed in Fig. 8e, the application of in-plane tensile strain significantly reduces the size of the bubble domains (b1, b2). This phenomenon is attributed to the increased coercive field of the film under tensile stress, which hinders domain wall propagation and consequently restricts domain expansion. In contrast, compressive stress induces negligible change in the coercive field, leading to minimal variation in bubble domain size (b1, b3). The distinct responses to tensile and compressive stress can be ascribed to their differential effects on the magnetic anisotropy energy of the film. This work demonstrates that the size and stability of magnetic domains in films with PMA can be reversibly and in situ modulated solely through controlled mechanical strain.

Reorientation of the stripe domains in FeGa films under compressive (a) and tensile (b) strain. Reproduced with permission53. Copyright 2020, IOP Publishing. The arrangement of stripe domains in Ni films (c) and Permalloy films (d) under tensile stress from PMMA nanotrenches. Reproduced with permission17. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. Reproduced with permission54. Copyright 2024, Elsevier. e Magnetic domain images of the Ta/Pt/Co/Pt film acquired by Magneto-optical Kerr microscope (MOKE) under different strain states and magnetic fields58. Copyright 2020, IOP Publishing with a Creative Commons CC-BY license.

Additionally, strain can also influence the formation and reversal of topological magnetic structures, such as skyrmions59,60,61. The Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI) is crucial for stabilizing skyrmions62,63,64. It is highly sensitive to lattice symmetry and atomic spacing. Mechanical strain directly perturbs these parameters, thereby providing a potent handle to manipulate the DMI strength. For example, Li et al.65 simulated the effect of strain on the DMI energy in Fe₃GeTe₂. As shown in Fig. 9a, applying −3% compressive strain in a Ge/Fe₃GeTe₂ heterostructure increased the DMI strength by more than 400% (from 0.25 meV to 1 meV). This DMI enabled efficient control of skyrmions with a size below 10 nm in Fe₃GeTe₂ under zero magnetic field. Gusev et al.66 investigated the effect of strain on the DMI in Ta/Pt/Co/Pt multilayer films. They observed that under compressive strain, Dx and Dy exhibit pronounced anisotropy (Fig. 9b). When the compressive strain increases beyond a critical value, the sign of Dy reverses while the sign of Dx remains unchanged. This distinctive behavior facilitates the formation of antivortex skyrmions67. Deger68 revealed through first-principles calculations that the DMI strength at the Co/Pt interface is highly sensitive to lattice strain (c/a). Applying approximately 7% tensile strain (c/a ≈ 1.1) can significantly enhance the DMI by up to 32% (Fig. 9c). The underlying mechanism originates from strain-induced modifications in interatomic distances, which lead to hybridization of dxy and dx²−y² orbitals, thereby modulating the spin-orbit coupling effect and consequently the DMI strength. Sapozhnikov et al.69 further investigated the effect of strain on the DMI in Co/Pt multilayer films. They observed the film’s magnetic domain structure transitioned from isotropic labyrinth domain to oriented stripe domain and zigzag domain after applying compressive strain. This transition was also attributed to the strong anisotropic of the DMI under compressive strain (Fig. 9d).

a The variation of DMI energy in Fe₃GeTe₂ with strain. Reproduced with permission65. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. b The DMI constant measured along the x (red) and y (blue) directions (Dx, Dy) as a function of applied strain for the Ta/Pt(1.1)/Co(1.2)/Pt(2) multilayers. Reproduced with permission66. Copyright 2020, American Physical Society. c The dependence of the total DMI coefficient on the ratio of lattice parameters for the Co(2)/Pt(2) film68. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. d The DMI constants (Dx, Dy) measured along the x (red) and y (blue) directions as a function of applied strain for the Co(0.7)/Pt(1.1) multilayers. Reproduced with permission69. Copyright 2022, American Physical Society.

These strain-induced modulations of the DMI in thin films can effectively control the generation and type of skyrmions. Yang et al.70 constructed a flexible multilayer film of Mica/Ta/CoFeB/TaOx/MgO/Ta, where tensile strain reduced the PMA and DMI energy of the film through inverse magnetostriction, resulting in a reduction in the size of skyrmions (Fig. 10a).

a Skyrmion observation via MOKE in Mica/Ta/CoFeB/TaOx/MgO/Ta films in both flat and bent states. Reproduced with permission70. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. b Distribution of magnetic domain, ɛxx, ɛxx,z, and ɛxx,x in the comparison with topography line profile. Reproduced with permission71. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH. c Magnetic domain evolutions in the field increasing process of [Pt/Co/Ta]10 grown on thin PI, mica, and thick PI. Reproduced with permission72. Copyright 2025, AIP Publishing. d Magnetic field-dependent MFM images of AZO/[Pt/Co/Ta]12 measured under a fixed strain73. The scale bar is 1 μm. Copyright 2025, AAAS with a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC license.

Jin et al.71 introduced gradient strain into the van der Waals ferromagnet Fe₃GaTe₂ by utilizing the wrinkled morphology generated on a PDMS substrate (Fig. 10b). In the wrinkled structure, the presence of strain gradient leads to an asymmetric evolution of magnetic domains in Fe₃GaTe₂ on either side of the wrinkle peaks. The region from valley to peak retains labyrinthine domains, while the region from peak to valley gradually transforms into skyrmions. This asymmetric evolution originates from the opposite signs of the in-plane strain gradient (εxx,x) on the two sides of the wrinkle peaks and valleys. This sign reversal results in the valley-to-peak region exhibiting larger PMA and DMI, while the peak-to-valley region exhibits smaller PMA and DMI. The roughness of flexible substrates also influences the formation of skyrmions in thin films. As shown in Fig. 10c, Qiu et al.72 investigated the influence of different flexible substrates on the formation and evolution of skyrmions in Pt/Co/Ta multilayers. Under an applied magnetic field of 450 Oe, a high density of skyrmions was observed on rough thick PI substrates, whereas only a limited number of skyrmions formed on the low-roughness thin PI and mica substrates. This is because these interface-induced effects (PMA and DMI) decrease on rough substrates due to the poor quality of the interfaces between the Co layers and heavy metal layers. Ding et al.73 integrated Pt/Co/Ta multilayers with a flexible azobenzene (AZO) liquid crystal film, utilizing ultraviolet/green light irradiation to induce isomerization of AZO, thereby generating uniaxial tensile strain on the material surface. As shown in Fig. 10d, the strain in the film increases with prolonged UV illumination time, and the magnetic field required for skyrmion formation varies under different strain conditions. This regulatory mechanism is attributed to strain-induced anisotropy modulation of the DMI (Dx ≠ Dy). This work provides a novel strategy for developing low-power, multi-state, optically controllable flexible spintronic devices.

Effect of stress on magnetic anisotropy of magnetic films

The influence of stress on the crystal structure and magnetic domains of magnetic films at the microscopic is bound to be reflected in the macroscopic magnetic properties of the films, with the most significant effect being the magnetic anisotropy of the films. Dai et al.74 deposited Fe81Ga19 films on concave and convex PET substrates. After releasing the films to a flat state, they were subjected to tensile and compressive stresses. When subjected to stress, the magnetization of the Fe81Ga19 films is deflected due to magnetoelastic coupling, which alters their in-plane magnetic anisotropy. As compressive strain increases from −0.09% to −0.26%, the remanence ratio Mr/Ms of the in-plane hard axis decreases from 0.52 to 0.28 (Fig. 11a). When tensile strain increases from 0.23% to 0.62%, the coercivity of the in-plane hard axis increases from 48 Oe to 89 Oe (Fig. 11b), indicating that stress can control the direction of the in-plane hard/easy axis of the magnetic films. Ben Mahmoud et al.75 used a Magneto-optical Kerr microscope (MOKE) to observe the in-situ changes in the hysteresis loops of Co and Ni78Fe22 films in the in-plane 0° and 90° directions under tensile stress (Fig. 11c). It is clearly demonstrated that the in-plane magnetic anisotropy of both films is enhanced under tensile stress. Notably, the enhancement in Co films is significantly stronger than in Ni78Fe22 films. And the hysteresis loop of the former shows a noticeable change in the 0° direction, while that of the latter changes significantly in the 90° direction. This is because the magnetostrictive coefficient of Ni78Fe22 is positive (~ +1.5 × 10−6) and smaller than that of Co (~ -1.4 × 10−5). Additionally, magnetic films with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (PMA) are crucial for the development of spintronic devices, and stress also plays a significant role in tuning the PMA61,76,77. Cheng et al.78 fabricated a (Co/Pt)5/BaTiO3 heterostructure on a PDMS substrate using Sr3Al2O6 as a sacrificial layer and compared the resonance field (Hr) of the heterostructure before and after removing the sacrificial layer, as well as under different bending radii (Fig. 11d). After releasing the substrate constraint, both the in-plane and out-of-plane Hr of the heterostructure decrease. This reduction arises from stress release reducing the residual internal stress and thereby adjusting the magnetic anisotropy field. During further bending, the in-plane Hr decreased by 217 Oe, while the out-of-plane Hr increased by 272 Oe. This suggests that the difference between the out-of-plane and in-plane Hr decreased significantly, indicating that the PMA of the heterostructure was weakened. When the sample returned to the flat state, the resonance field almost completely reverted to its initial value. This indicates that the changes in magnetic anisotropy induced by stress are highly reversible. This directional, reversible stress response opens new pathways for the development of tunable flexible devices based on the ferromagnetic resonance mechanism. Gokita et al.79 fabricated a Ta/Co20Fe60B20/MgO/Ta Hall bar with PMA on a flexible substrate (Fig. 11e). When the Hall bar is subjected to biaxial tensile strain increasing from 0% to 2%, its anomalous Hall loop becomes progressively flatter, indicating that its PMA decreased with the strain increasing. When the strain is gradually reduced, the anomalous Hall curve overlaps completely with that of corresponding strain during the increasing process, demonstrating that the strain induced PMA tuning is highly reversible.

The variation in the hysteresis loops of Fe81Ga19 films under (a) compressive stress and (b) tensile stress. Reproduced with permission74. Copyright 2013, AIP Publishing. c The surface and hysteresis loop changes of Co and Ni78Fe22 films under tensile stress Reproduced with permission75. Copyright 2023, AIP Publishing. d The variation in the resonance field of (Co/Pt)5/BaTiO3 heterostructures under tensile stress. Reproduced with permission78. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. e The anomalous Hall resistance curves of Co20Fe60B20 films under different biaxial tensile strains Reproduced with permission79. Copyright 2023, IOP Publishing.

In summary, a comparative analysis of the above studies reveals several overarching trends regarding strain-mediated control of magnetic anisotropy. The effect of uniaxial strain is dependent on the sign of the magnetostriction coefficient (λ). For materials with positive λ (e.g., NiFe, FeGa), tensile strain typically enhances the in-plane anisotropy along the strain direction, while compressive strain promotes anisotropy perpendicular to it. The inverse relationship holds for materials with negative λ (e.g., Co). For PMA systems, both tensile and compressive strains generally act to reduce the perpendicular anisotropy field, facilitating easier magnetization rotation towards the in-plane direction. The strain-induced modifications are largely reversible upon elastic deformation, which is crucial for reliable operation of flexible devices.

Flexible magnetic devices

Flexible giant magnetoresistance devices

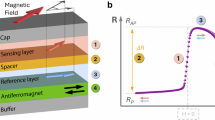

The giant magnetoresistance (GMR) effect is the first magnetoresistive phenomenon to achieve commercial application. It relies on multilayer structures composed of alternating ferromagnetic and nonmagnetic metallic layers80,81,82. When the magnetization directions of adjacent ferromagnetic layers change from parallel to antiparallel under an external magnetic field, spin electrons experience enhanced interfacial scattering, leading to a significant resistance change. The GMR ratio is typically expressed as:

In the formula, R0 and RH represent the resistances under zero field and saturating magnetic field, respectively. Current flexible sensors based on GMR multilayer designs exhibit high sensitivity and stability83,84. For instance, Makushko et al.85 developed a 120 × 120 mm2 grid shaped electronic skin using a synergistic design of Co/Cu multilayers and electrical magnetoresistive tomography (EMRT). This mesh structure provides 75% optical transparency and skin like breathability (Fig. 12a), addressing long-term wearability. The device maintains a stable magnetoresistive response (23% GMR ratio) even under 100% tensile strain (Fig. 12b), enabling robust human–machine interaction sensing applications (Fig. 12c).

a Scanning electron microscope image of the Co/Cu multilayer grid GMR sensor and a schematic of its application in smartphones using electrical magnetoresistive tomography (EMRT)85. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. b Variation of the GMR curves under biaxial and uniaxial tensile strains. c Interactive writing of the letter 'H' using grid GMR sensor and a pen with a permanent magnet NdFeB. d Change in GMR curves of the spin valve on a PI substrate with varying bending angles89. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. e Variation of GMR curves of the spin valve on PDMS/PI rigid islands under omnidirectional tensile stress. Reproduced with permission15. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society.

Beyond ferromagnetic/nonmagnetic multilayers, spin valves represent another kind of GMR-based device architecture. A spin valve typically comprises a pinned layer, a nonmagnetic metallic spacer, and a free layer18,86,87,88. The magnetization direction of the pinned layer is fixed by the antiferromagnetic material. The spacer layer is typically made of nonmagnetic metal and serves to transmit spin electrons without contributing to magnetic coupling. The magnetization direction of the free layer can freely switch in response to the external magnetic field. This structure endows spin valves superior magnetic sensitivity compared to multilayer GMR. Zhang et al.89 fabricated spin valve arrays on ultrathin PI substrates (Fig. 12d). These devices retained consistent magnetoresistance curves and a stable GMR ratio of 2.46% even when bent from 0° to 90°, owing to the ultra-thin PI substrate (0.97 μm thickness) prepared by CAED. Similarly, Pan et al.15 achieved stable GMR performance under extreme deformations by integrating rigid PI islands with an elastic PDMS substrate (Fig. 12e). The sensor maintained unaltered GMR curves and a maximum GMR ratio of ~8% even under 86% omnidirectional tensile strain, highlighting its potential for stretchable electronics. Finally, we compared the structures and GMR ratio of some existing flexible GMR sensors in Table 2.

To further extend the application potential of these devices, flexible GMR devices have been progressively integrated with thin-film transistors (TFTs) and CMOS circuits90,91. Researchers have demonstrated that flexible GMR devices exhibit excellent adaptability and compatibility with both flexible inorganic and organic electronics. For instance, Kondo et al92. integrated a GMR sensor array with amplification circuits on a 50 × 50 mm² parylene to develop an active magnetosensory matrix (MSM) system. As shown in Fig. 13a, this system enables non-contact motion capture and position sensing using only a tiny magnet worn on the finger. Figure 13b illustrates that the MSM consists of a 3 × 6 GMR sensor array, shift registers, current mirrors, and amplifiers, granting the system high sensitivity and the capability for real-time mapping of 2D magnetic field distribution. Münzenrieder et al.93 constructed an integrated magnetic sensing system on a 50 μm thick PI. As summarized in Fig. 13c, the system includes a GMR Wheatstone bridge, a differential operational amplifier based on IGZO (indium-gallium-zinc-oxide) thin-film transistors, and a high-current output power amplifier. This system achieves on-site signal conditioning and amplification, avoiding the noise and signal degradation issues associated with traditional flexible sensors that require long cables to connect to rigid circuits. It significantly enhances the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and system bandwidth. This research represents a pioneering fully flexible, high-gain, low-noise integrated magnetic sensing and signal conditioning system, advancing the development of flexible magnetic sensing technologies.

Flexible magnetic tunnel junction devices

The magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ) is a kind of magnetoresistive device based on quantum tunneling effects94. Its typical structure consists of two ferromagnetic layers with an inserted insulating layer95,96,97. There is little to no interlayer coupling between the two ferromagnetic layers in MTJ, and a small external magnetic field is sufficient to reverse the magnetization direction of the free layer, resulting in a significant change in tunneling resistance. Therefore, MTJ exhibits higher magnetic field sensitivity compared to GMR devices. The working principle of MTJ devices relies on the tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) effect. When the magnetization directions of the two ferromagnetic layers are parallel, the high probability of electrons tunneling through the insulating layer results in a low resistance. When the magnetization directions are antiparallel, the tunneling probability of electrons is significantly reduced, correspondingly the resistance increases. The TMR ratio can be calculated by the following formula:

Here, P1 and P2 denote the spin polarization rates of the pinned layer and free layer, respectively. With advancements in flexible electronics and MTJ devices, MTJ devices on flexible substrates are increasingly emerging98,99. Ota et al.100 fabricated CoFeB/MgO/CoFeB MTJ with Ta/Ru cap layers on PI and Si substrates, respectively. Comparative analysis of TMR ratios under varying annealing temperatures reveals a consistent increase in TMR with rising temperatures for both substrates (Fig. 14a). Notably, PI substrates exhibit significantly enhanced TMR performance compared to Si. This enhancement stems from high temperature annealing significantly improving the crystallinity of the CoFeB layers and lattice ordering of the MgO barrier. Such improvements facilitate coherent tunneling of spin electrons, thereby amplifying the TMR effect. Additionally, PI’s higher thermal expansion coefficient (the coefficients are 1.6 × 105/K and 2.6 × 106/K for the PI and Si at room temperature, respectively) induces uniaxial strain during post-annealing cooling. This strain generates magnetic anisotropy in the CoFeB layers. It increases the coercivity difference between the top and bottom ferromagnetic layers and sharpens the magnetization switching. These effects collectively enhance the TMR. Chen et al.11 deposited CoFeB/MgO/CoFeB multilayers on 150 μm-thick double side polished Si substrates, patterning them into MTJ pillars via standard UV lithography and ion milling. Subsequent deep trench plasma etching (SF₆ and Ar) thinned the Si substrate to 14 μm, enabling transfer onto flexible substrates (Fig. 14b). When the bending radius decreased from 30 mm to 5 mm, the parallel state resistance (RP) remained stable at 342.5 ± 1.5 Ω. While the antiparallel state resistance (RAP) fluctuated slightly from 638 Ω to 646 Ω, resulting in TMR ratios varying within 186 ± 6%. Under tensile strain, the magnetic anisotropy field of the free layer decreased, causing a slight shift in antiparallel magnetization distribution and an increase in RAP. Conversely, compressive strain raised the anisotropy field to reduce RAP. However, RP governed by the intrinsic electronic structure of the MgO barrier, remained stable due to preserved crystallinity during bending. This asymmetric strain dependent resistance modulation provides a physical foundation for designing highly sensitive flexible magnetic sensors while ensuring operational reliability under dynamic deformation. Furthermore, strain-mediated TMR modulation using piezoelectric materials like Pb(Mg₁/₃Nb₂/₃)₀.₇Ti₀.₃O₃ (PMN-PT) has been proven highly effective101,102,103. Sun et al.104 engineered vertical MTJ with easy-cone magnetic anisotropy in the free layer on PMN-PT substrates (Fig. 14c). PMN-PT is a kind of high-performance piezoelectric material, undergoes an electric field induced rhombohedral-orthorhombic phase transition, generating significant in-plane compressive and out-of-plane tensile strains. These strains propagate to the MTJ’s free layer via heterointerfaces, altering the easy-cone angle (Δθ) of magnetization. Applying ±10 kV/cm electric fields shifted Δθ by up to 31° (Fig. 14d), inducing a ~ 17% relative change in TMR (Fig. 14e). This approach circumvents risks associated with conventional voltage-controlled magnetic anisotropy (VCMA) techniques that apply high voltages directly to the barrier layer, significantly enhancing device reliability. We have also summarized the structure and TMR ratio of these flexible TMR devices in Table 3.

a TMR ratio versus temperature for MTJ on Si and PI substrates. Reproduced with permission100. Copyright 2019, AIP Publishing. b Schematic of the fabrication process for the Kapton/Si/MTJ device and the variation of magnetoresistance with bending radius11. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. c Schematic diagram of MTJ device on PMN-PT substrate104. Copyright 2024, AAAS with a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC license. d Variation of the easy- cone angle Δθ with the electric field. e Variation of MTJ resistance with the electric field.

Flexible anisotropic magnetoresistance devices

The Anisotropic Magnetoresistance (AMR) effect is the phenomenon where the electrical resistance of ferromagnetic materials changes with the angle between the magnetization direction and the current direction105. The strength of the AMR effect is typically expressed using the AMR ratio, which can be calculated using the following formula:

Here, \({\rho }_{\perp }\) is the resistivity when the current is perpendicular to the magnetization direction of the film, and \({\rho }_{{||}}\) is the resistivity when the current is parallel to the magnetization direction of the film. The planar Hall effect (PHE) has emerged as a highly sensitive and versatile sensing mechanism for AMR devices106,107. While the ordinary Hall effect measures the voltage developed perpendicular to both the applied current and magnetic field directions, the PHE is a manifestation of the anisotropic magnetoresistance in ferromagnetic materials. It generates an output voltage in the plane of the film but perpendicular to the current direction, exhibiting a characteristic dependence on the angle between the magnetization and the current flow. The output voltage (VPHE) is delivered as108,109:

where I is current applied along the long axis of the Hall bar, θ denotes the angle between the magnetization and current, and t is the thickness of the magnetic film. Meanwhile, researchers have begun exploring the application of AMR devices on flexible substrates for wearable devices110,111. Granell et al.112 fabricated a Permalloy Hall bar on a 6 µm thick PET substrate. Notably, a layer of SU-8 photoresist was pre-cured on the PET substrate to improve its surface roughness. As shown in Fig. 15a, the maximum sensitivity of the sensor in its flat state was 0.86 V/T. Even when bent to a 1 mm radius, the sensitivity remained at 0.63 V/T, demonstrating the good stability of this flexible AMR device. Özer et al.113 fabricated a NiFe/IrMn/Pt multilayer Hall bar on a PDMS/Kapton substrate. As shown in Fig. 15b, the AMR ratio increased as the device became more concave from its flat state, while the AMR ratio decreased as the device became more convex. After returning to the flat state, the AMR ratio showed a deviation from its initial value, which may be due to residual strain.

a Magnetoelectrical characterization of PET/SU-8/Permalloy sensors in the flat state and when bent to 1 mm112. Copyright 2019, Springer Nature with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. b AMR variations of PDMS/kapton/NiFe/IrMn/Pt devices under different curvatures. Reproduced with permission113. Copyright 2019, IEEE. c AMR and sensitivity variations of barber pole AMR sensors on different substrates. Reproduced with permission116. Copyright 2016, Wiley-VCH. d AMR and resistance variations of barber pole AMR sensors on Mylar foils with changing bending curvature. Reproduced with permission9. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature.

In addition to the AMR sensors shaped in Hall bar mentioned above, there is another type of AMR sensor based on the barber pole structure. The barber pole structure refers to sensors with periodic stripe and helical electrode designs, which enhance the AMR effect by optimizing the magnetic field distribution and current path. This structure consists of alternating inclined metallic stripe electrodes and magnetic film regions, with the geometry guiding the current direction to improve the magnetic field sensitivity114,115. Wang et al.116 fabricated barber pole AMR sensors composed of Permalloy stripes and inclined gold electrodes on three different substrates: SiO2/Si, PET + photoresist (PR), and PET (Fig. 15c). The PET + PR substrate features a spin coated photoresist smooth layer. The PR buffer layer optimizes the surface roughness of the flexible PET substrate, effectively enhancing the performance of the flexible AMR sensor. This approach achieves sensitivity and AMR ratios comparable to those of rigid substrates. Bermúdez et al.9 fabricated a barber pole AMR sensor with Permalloy stripes and gold electrodes at different tilt angles on 6 µm thick mylar foils (Fig. 15d). At a bending radius as small as 150 µm, the AMR effect of the sensor slightly decreased to 1.1% (from 1.4% in the flat state) but maintained high performance. The detection limit of the device is 50 nT, making it suitable for use as a flexible compass. These studies on flexible AMR devices provide significant technical support for the practical application of wearable magnetoelectronic devices. In Table 4, we summarize the materials and performance of these flexible AMR devices.

Printed and printable flexible magnetic devices

Printed and printable flexible magnetic devices refer to magnetoelectronic devices fabricated directly on flexible substrates using functional inks (such as magnetic materials and conductive materials) and manufacturing techniques like roll-to-roll117,118,119 and Inkjet printing111,120,121,122. This technology offers advantages such as low cost, large-area production, sustainability, and broad substrate compatibility. Xu et al.122 printed transparent magnetoresistive sensors on PET substrates using NiFe nanowire inks. As shown in Fig. 16a, the application of a magnetic field during the printing process enabled the aligned orientation and large-area uniform distribution of NiFe nanowires, significantly enhancing the transparency and performance of the sensors. The sensors exhibited excellent mechanical durability (Fig. 16c), the magnetoresistance response curves remained highly stable after 1000 repeated bending cycles, and the magnetoresistance ratio showed no significant degradation under different bending radii. From Fig. 16d, it can be observed that as the applied tensile strain gradually increased from 0% to 80%, both the switching field and the magnetoresistance ratio of the device underwent no notable changes. This remarkable stretchability primarily stems from the pre-introduced wavy structures in the NiFe nanowire. This approach provides a new technological pathway for the large-scale production of stretchable magnetoelectric devices.

a Schematic diagram of printed magnetic sensors using NiFe nanowires122. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. b Printed magnetic sensor network on PET substrate. c Variation in magnetoresistance response of sensors after bending cycles. d Changes in magnetoresistance response under different tensile strains.

Roll-to-roll is a continuous manufacturing process123,124,125 where flexible substrates are unwound from one roll, undergo processing steps such as ink coating, printing, drying, and curing, before being rewound into another roll. In recent years, researcher have integrated roll-to-roll technology with magnetron sputtering for large-scale manufacturing of flexible magnetoelectronic devices. Gupta et al.119 developed a roll-to-roll thin-film magnetron sputtering system (Fig. 17a) and utilized it to achieve large-area fabrication of Co/Cu multilayer GMR sensors on PET substrates. Figure 17b illustrates the specific process flow for depositing [Co/Cu]30 GMR multilayers on a 100-meter-long PET using this roll-to-roll system: beginning with the pristine PET web, the material is sequentially transported through cobalt and copper deposition chambers for alternating sputtering cycles, completing a total of 30 Co/Cu bilayers. As shown in Fig. 17c, the GMR ratios measured from four different sections of the 100-meter web were 38%, 40%, 34%, and 35%, respectively, demonstrating excellent and consistent performance uniformity across the entire length of the deposited GMR multilayers. This confirms the feasibility and stability of the roll-to-roll sputtering process for large area production of flexible magnetic devices.

a Schematic of the roll-to-roll thin-film magnetron sputtering system119. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. b Schematic of Co/Cu multilayer deposition process on the PET by roll-to-roll thin-film magnetron sputtering system. c GMR response at each 20 m along 100 m of the PET and M–H curve of [Co/Cu]30 multilayer.

Flexible spin orbit torque devices

Spin orbit torque (SOT) primarily arises from the spin Hall effect (SHE)126 and the Rashba-Edelstein effect127. The SHE refers to the phenomenon where the strong spin orbit coupling (SOC) of a heavy metal layer128,129 causes the current to split into two spin currents with opposite polarization directions in the perpendicular direction. The magnetic moments of the magnetic layers are reversed by the SOT. The Rashba-Edelstein effect is a SOC effect caused by structural inversion asymmetry, such as at interfaces or heterojunctions. When a material or interface lacks spatial inversion symmetry, the spin of the electrons is split perpendicular to their momentum direction, forming a spin polarized band structure. In recent years, research on flexible SOT devices has been growing130,131,132,133,134. Due to the lower thermal conductivity of flexible substrates, the magnetic moments in the overlying magnetic layers may be more easily reversed135,136. Wang et al. 137. deposited Ta/Pt/Co75Tb25/Ta multilayers on a PI substrate. Notably, the Pt layer in the film was sputtered at an oblique angle, breaking the spatial inversion symmetry along the y-direction, which is crucial for realizing magnetic moment reversal without an external magnetic field138. Both before and after bending, as well as during bending, the multilayer film can achieve magnetic moment reversal without an external magnetic field (Fig. 18a) and has a lower switching current density (4.9×106 A/cm2) compared to a rigid substrate139. The lower switching current density is due to the lower thermal conductivity of PI, which generates higher Joule heating, favoring magnetic moment reversal. Wang et al. 8. analyzed the effects of Joule heating generated by flexible substrates on the SOT switching current. They deposited Ta/Pt/Co/Ta multilayers on Kapton and SiO/Si substrates, respectively. By comparing the SOT switching curves, it was found that the reversal current on the Kapton substrate only requires 6.87 mA (Fig. 18b). This corresponds to a current density of 2.59 × 106 A/cm2, which is about 1/7 of that for the film on the Si/SiO substrate (1.79×107 A/cm2). This demonstrates the unique advantage of flexible SOT devices in SOT switching.

a Schematic of the Ta/Pt/Co75Tb25/Ta/PI film structure and the SOT switching curve under zero magnetic field. Reproduced with permission137. Copyright 2024, AIP Publishing. b Comparison of the SOT switching curves for Ta/Pt/Co/Ta films on SiO/Si and Kapton substrates. Reproduced with permission8. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society.

Flexible substrates not only reduce the SOT switching current density but also the stress they introduce can be used to tune the spin Hall angle of SOT devices. Hwee Wong et al. 140. deposited Pt/Co films on Kapton substrates and studied the significant immediate and lasting effects of tensile strain on the spin Hall efficiency (θeff) in flexible Pt/Co multilayers (Fig. 19a). When a 1.5% tensile strain was applied along the current direction, the θeff of the Pt layer increased from an initial value of 0.07 to 0.101. This enhancement is primarily attributed to the increased scattering due to lattice distortion caused by the strain. When strain was applied perpendicular to the current direction, no significant change in θeff was observed, due to the minimal effect of lattice distortion on electron scattering in the perpendicular direction. After removing the external strain, the enhanced θeff was retained at 78% (0.093), indicating that the persistent reconstruction of lattice defects or residual stress has an irreversible impact on the electronic transport properties. Liu et al.132 grew Ta/Fe/Pt multilayers on flexible mica substrates and achieved significant modulation of the θeff by applying in-plane compressive strain (Fig. 19b). When the current direction was parallel to the strain direction, the θeff increased significantly with strain. Specifically, under a compressive strain of 6.26%, the θeff increased from 0.12 in the unstrained state to 0.2, and this enhancement remained stable across frequencies (6–20 GHz). This phenomenon also indicates that strain enhances the contribution of skew scattering by modulating lattice distortion, thereby improving spin Hall efficiency. Furthermore, when the current direction was perpendicular to the strain direction, no significant change in the spin Hall angle was observed, which remained around 0.12. The stress-enhanced skew scattering mechanism provides important experimental support for strain engineering in flexible spintronic devices.

The studies discussed throughout this Section 5 demonstrate that the core performance metrics of flexible magnetoresistance devices exhibit remarkable resilience against mechanical deformation. The magnetoresistance ratios (GMR, TMR, AMR) and sensitivity of more devices remain largely stable under different strain. The small variations observed stem from strain-induced modifications of magnetic properties, which can shift device operating points or alter sensitivity. Furthermore, strain can be strategically leveraged to enhance device performance, such as the significant increase in spin Hall efficiency. In conclusion, the fundamental functionality of these devices proves to be highly reliable for different flexible applications.

Flexible energy harvesting devices

Energy harvesting devices are systems capable of capturing ambient micro-energy (e.g., mechanical vibration, thermal gradients, light, or electromagnetic radiation) and converting it into electrical power141,142,143,144. These devices hold significant potential for applications in the Internet of Things (IoT), wearable electronics, and wireless sensor networks, addressing limitations of conventional batteries such as finite lifespan and replacement challenges. Magnetostrictive materials exhibit dynamic reconfigurations of magnetic domains and domain walls under applied stress. Domain wall motion is crucial for magnetic memory applications, where information is stored in magnetic domains and retrieved by manipulating their positions145,146,147. The motion of domain walls can also be used in energy harvesting devices. Applied stress induces variations in domain walls, which are then converted into electrical voltage148,149,150. Bhatti et al.12 designed a magnetic microwire comprising a CoNi/FeCo/CoNi trilayer, where the FeCo layer exhibits high magnetostriction (~5.8 × 10−5). Under the application of compressive stress, the domain walls of originally oriented perpendicular to the microwire length gradually diminish. Eventually, magnetic microwire formed a single domain structure (Fig. 20a). This process is accompanied by significant changes in magnetic flux, which can be converted into electrical voltage using pickup coils. When exposed to a 3.7 kHz acoustic wave, the energy generated by the flux variation was effectively harvested through a coil positioned on the microwire (Fig. 20b). This successfully demonstrates its viability as an energy harvesting device. Kurita et al.151 sputtered a 0.1 mm-thick CoFe₂O₄ film onto an Fe-Co substrate (Fig. 20c). CoFe₂O₄ (negative magnetostriction) and Fe-Co (positive magnetostriction) form a composite where mechanical vibration generates strain gradients, amplifying dynamic magnetic flux changes. These flux variations induce measurable voltages in a pickup coil (Fig. 20d). Output voltage comparisons between Fe-Co/CoFe₂O₄ and Fe-Co/Ni plates under varying vibration frequencies demonstrate the former’s superior performance across most frequencies (Fig. 20e). Energy harvesting devices are driving the advent of a battery-free era. Breakthroughs in magnetostriction and magnetoelectric coupling technologies offer novel pathways for efficient low-frequency mechanical energy utilization.

a Variation of CoNi/FeCo/CoNi microwire domain walls under different stresses(0.47–3.78 GPa)12. The scale bar is 25 μm. Reproduced with permission12. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. b Voltage profile collected by CoNi/FeCo/CoNi microstrip within 2.4 ms under the influence of a 3.7 kHz acoustic wave. c Interface scanning electron microscopy and XRD spectra of Fe-Co/CoFe₂O₄ films151. Copyright 2023, Elsevier B.V with a Creative Commons CC-BY license. d Schematic illustration of the energy storage and information transmission tests. e Output voltage of Fe-Co/CoFe₂O₄ films and Fe-Co/Ni films at different frequencies.

Summary and outlook

The rapid advancement of flexible magnetic films and spintronic devices has provided critical technological support for the transition from traditional rigid electronics to wearable, bendable, and implantable systems. This review systematically explores the stress modulation mechanisms of physical properties in magnetic films, fabrication methods on flexible substrates and their diverse applications in magnetoelectronic devices. In stress modulation, mechanical strain significantly influences the crystal structure, magnetic domain alignment, and magnetic anisotropy of films through magnetoelastic coupling. By employing pre-strained substrates or periodic wrinkling designs, researchers can precisely control domain orientation and dynamic behaviors. In fabrication, the integration of direct deposition techniques and indirect transfer methods has enabled high quality magnetic films on flexible substrates. SOT devices leverage low thermal conductivity flexible substrates to reduce switching current density while enhancing spin Hall efficiency under strain. AMR and giant GMR sensors maintain high sensitivity even when bent, offering reliable solutions for electronic skins and human-machine interfaces. TMR in MTJs lays the foundation for low power memory and logic devices. Furthermore, dynamic magnetic flux variations induced by stress driven domain wall motion enable the conversion of mechanical vibrations into electrical energy, advancing battery-free IoT technologies.

Despite these advances, challenges persist in flexible magnetoelectronic devices. Most magnetic materials exhibit limited stress tolerance, necessitating the exploration of novel materials that combine mechanical robustness with optimized magnetoelectric properties. For emerging two- dimensional magnetic materials152 (e.g., Fe₃GaTe₂, Fe₃GeTe₂), their magnetic anisotropy energy and spin exchange coupling are highly strain-sensitive. While DFT studies have predicted strain-induced lattice and magnetic modifications51,52,153, experimental validation remains sparse. macroscopic or localized stress engineering of these materials could unlock new avenues for flexible spintronic devices. Finally, with the developments of machine learning and artificial intelligence, magnetoelectronic devices based on fully connected neural network (FCNN) are emerging137,154. Flexible integration of such devices to construct AI driven networks represents a promising frontier for the field.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Nathan, A. et al. Flexible electronics: the next ubiquitous platform. Proc. IEEE 100, 1486–1517 (2012).

Dahiya, R. E-Skin: from humanoids to humans. Proc. IEEE 107, 247–252 (2019).

Cañón Bermúdez, G. S. et al. Magnetosensitive E-skins for interactive devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2007788 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. A review on magnetic smart skin as human-machine interfaces. Adv. Electron. Mater. 10, 2300677 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Mechanically tunable magnetic and electronic transport properties of flexible magnetic films and their heterostructures for spintronics. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 9400–9430 (2021).

Pan, L. et al. Flexible magnetic sensors. Sensors 23, 4083 (2023).

Parkin, S. S. P. et al. Giant magnetoresistance in antiferromagnetic Co/Cu multilayers grown on kapton. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 31, L1246 (1992).

Wang, W. et al. Heat-assisted magnetization switching in flexible spin-orbit torque devices. Nano Lett. 24, 2003–2010 (2024).

Cañón Bermúdez, G. S. et al. Electronic-skin compasses for geomagnetic field-driven artificial magnetoreception and interactive electronics. Nat. Electron. 1, 589–595 (2018).

Ge, J. et al. A bimodal soft electronic skin for tactile and touchless interaction in real time. Nat. Commun. 10, 4405 (2019).

Chen, J. Y. et al. High performance MgO-barrier magnetic tunnel junctions for flexible and wearable spintronic applications. Sci. Rep. 7, 42001 (2017).

Bhatti, S. et al. Stress-induced domain wall motion in FeCo-based magnetic microwires for realization of energy harvesting. Adv. Electron. Mater. 5, 1800467 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. Current-controlled propagation of spin waves in antiparallel, coupled domains. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 691–697 (2019).

Hopcroft, M. A. et al. What is the young’s modulus of silicon?. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 19, 229–238 (2010).

Pan, L. et al. Omnidirectionally stretchable spin-valve sensor array with stable giant magnetoresistance performance. ACS Nano 19, 5699–5708 (2025).

Zhang, Y.-J. et al. Mechanical behaviors of quenched iron film sputtering deposited on glass substrate. Surf. Rev. Lett. 14, 879–884 (2007).

Zhang, J. et al. Spontaneous formation of ordered magnetic domains by patterning stress. Nano Lett. 21, 5430–5437 (2021).

Melzer, M. et al. Stretchable spin valves on elastomer membranes by predetermined periodic fracture and random wrinkling. Adv. Mater. 24, 6468–6472 (2012).

Zou, M. et al. Biaxially stretchable spin valves with stable magnetic sensing performance. IEEE Magn. Lett. 15, 1–5 (2024).

Xue, K. et al. Stabilizing high-frequency magnetic properties of stretchable CoFeB Films by Ribbon-patterned periodic wrinkles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 15014–15023 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Surface morphology and magnetic property of wrinkled FeGa thin films fabricated on elastic polydimethylsiloxane. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 102409 (2016).

Li, M. et al. Enhanced stress stability in flexible Co/Pt multilayers with strong perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Nano Lett. 23, 8073–8080 (2023).

Sheng, P. et al. Magnetoelastic anisotropy of antiferromagnetic materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 242403 (2019).

Li, M. et al. An ultrathin flexible programmable spin logic device based on spin-orbit torque. Nano Lett. 23, 3818–3825 (2023).

Cheng, W. J. et al. Stretchable spin valve with strain-engineered wrinkles grown on elastomeric polydimethylsiloxane. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 52, 095003 (2019).

Leppäniemi, J. et al. Far-UV annealed inkjet-printed In2O3 semiconductor layers for thin-film transistors on a flexible polyethylene naphthalate substrate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 8774–8782 (2017).

Ota, S. et al. A flexible giant magnetoresistive device for sensing strain direction. Nat. Electron. 1, 124–129 (2018).

Lei, T. et al. Tuning the ferromagnetic resonance frequency of microstructured permalloy film on flexible substrate. Phys. status solidi (RRL)-Rapid Res. Lett. 18, 2400081 (2024).

Tang, Z. et al. Thickness dependence of magnetic anisotropy and domains in amorphous Co40Fe40B20 thin films grown on PET flexible substrates. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 426, 444–449 (2017).

Xin, F. et al. Mechanically tuning magnetism and transport property in spin gapless semiconductor CoFeMnSi flexible thin film. J. Alloys Compd. 813, 152207 (2020).

Hou, W. et al. Low-voltage-manipulating spin dynamics of flexible Fe3O4 films through ionic gel gating for wearable devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 21727–21733 (2019).

Tang, Z. et al. Magneto-mechanical coupling effect in amorphous Co40Fe40B20 films grown on flexible substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 103504 (2014).

ChenX. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 505, 166750 (2020).

Dai, G. et al. Mechanically tunable magnetic properties of Fe81Ga19 films grown on flexible substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 122407 (2012).

Bitla, Y. et al. MICAtronics: a new platform for flexible X-tronics. FlatChem 3, 26–42 (2017).

Liu, H.-J. et al. Flexible heteroepitaxy of CoFe2O4/muscovite bimorph with large magnetostriction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 7297–7304 (2017).

Merabtine, S. et al. Origin of relationship between ferromagnetic response and damage in stretched systems. Sci. Rep. 8, 13695 (2018).

Pandey, E. et al. Impact of structural deformation on magnetic and electronic properties in flexible PMA thin films. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 58, 175003 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Flexible quasi-two-dimensional CoFe2O4 epitaxial thin films for continuous strain tuning of magnetic properties. ACS Nano 11, 8002–8009 (2017).

Han, K. et al. Enhanced metal–insulator transition in freestanding VO2 down to 5 nm thickness. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 16688–16693 (2021).

Pesquera, D. et al. Large magnetoelectric coupling in multiferroic oxide heterostructures assembled via epitaxial lift-off. Nat. Commun. 11, 3190 (2020).

Lu, Z. et al. Synthesis of single-crystal La0.67Sr0.33MnO3 freestanding films with different crystal-orientation. APL Mater. 8, 051105 (2020).

Lu, Z. et al. Cooperative control of perpendicular magnetic anisotropy via crystal structure and orientation in freestanding SrRuO3 membranes. npj Flex. Electron 6, 9 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Wafer-scale fabrication of ultrathin flexible electronic systems via capillary-assisted electrochemical delamination. Adv. Mater. 30, 1805408 (2018).

Cao, D. et al. Controllable magnetic and magnetostrictive properties of FeGa films electrodeposited on curvature substrates. Appl. Phys. A 122, 1–6 (2016).

Shi, X. et al. Bending strain-tailored magnetic and electronic transport properties of reactively sputtered γ'-Fe4N/muscovite epitaxial heterostructures toward flexible spintronics. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 12, 27394–27404 (2020).

Dai, Z. et al. Strain engineering of 2D materials: issues and opportunities at the interface. Adv. Mater. 31, e1805417 (2019).

Du, J. et al. Strain engineering in 2D material-based flexible optoelectronics. Small Methods 5, e2000919 (2021).

Peng, Y. et al. Medium-scale flexible integrated circuits based on 2D semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 15, 10833 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Strain-sensitive magnetization reversal of a van der Waals Magnet. Adv. Mater. 32, e2004533 (2020).

Xie, W.-Q. et al. Strain-induced interlayer magnetic coupling spike of the two-dimensional van der Waals material Fe5GeTe2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127, 17194–17200 (2023).

Hu, X. et al. Enhanced ferromagnetism and tunable magnetism in Fe3GeTe2 monolayer by strain engineering. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 12, 26367–26373 (2020).

Dai, G. et al. Stress tunable magnetic stripe domains in flexible Fe81Ga19 films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 53, 055001 (2020).

Zhao, L. et al. Artificial magnetic disclination through local stress engineering. Acta Mater. 265, 119579 (2024).

Eimer, S. et al. Perpendicular magnetic anisotropy based spintronics devices in Pt/Co stacks under different hard and flexible substrates. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 66, 122408 (2023).

Kim, J. et al. Bending strain-induced changes in perpendicular magnetic properties of Pt/Co/Pt films on flexible substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 102401 (2024).

Hassan, M. et al. Thin-film heterostructures based on Co/Ni synthetic antiferromagnets on polymer tapes: toward sustainable flexible spintronics. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 14, 51496–51509 (2022).

Pandey, E. et al. Strain engineered domain structure and their relaxation in perpendicularly magnetized Co/Pt deposited on flexible polyimide. Nano Express 1, 010037 (2020).

Hu, J.-M. et al. Strain-mediated voltage-controlled switching of magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. npj Comput. Mater. 4, 62 (2018).

Hu, J.-M. et al. Stability and dynamics of skyrmions in ultrathin magnetic nanodisks under strain. Acta Mater. 183, 145–154 (2020).

Matsumoto, H. et al. Control of magnetic anisotropy in a Co thin film on a flexible substrate by applying biaxial tensile strain. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 022406 (2021).

Heide, M. et al. Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction accounting for the orientation of magnetic domains in ultrathin films: Fe/W(110). Phys. Rev. B 78, 140403 (2008).

Zhang, Y. et al. Stable skyrmion bundles at room temperature and zero magnetic field in a chiral magnet. Nat. Commun. 15, 3391 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Above-room-temperature chiral skyrmion lattice and Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in a van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3-xGaTe2. Nat. Commun. 15, 4472 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Strain-driven zero-field near-10 nm skyrmions in two-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures. Nano Lett. 22, 7706–7713 (2022).

Gusev, N. S. et al. Manipulation of the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in Co/Pt multilayers with strain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 157202 (2020).

Camosi, L. et al. Anisotropic Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in ultrathin epitaxial Au/Co/W(110). Phys. Rev. B 95, 214422 (2017).

Deger, C. Strain-enhanced Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction at Co/Pt interfaces. Sci. Rep. 10, 12314 (2020).

Sapozhnikov, M. V. et al. Zigzag domains caused by strain-induced anisotropy of the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 105, 024405 (2022).

Yang, Q. et al. Voltage control of skyrmion bubbles for topological flexible spintronic devices. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 2000246 (2020).

Jin, S. et al. Strain gradient induced skyrmion in a van der waals magnet by wrinkling. Adv. Mater. 37, e2501935 (2025).

Qiu, S. et al. Magnetic skyrmions on flexible substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 126, 142404 (2025).

Ding, B. et al. Multistep skyrmion phase transition driven by light-induced uniaxial strain. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt2698 (2025).

Dai, G. et al. Controllable strain-induced uniaxial anisotropy of Fe81Ga19 films deposited on flexible bowed-substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 173913 (2013).

Ben Mahmoud, H. et al. Tensile properties of ferromagnetic nanofilms on stretchable substrates: Links between multi-cracking and magnetic properties. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 252401 (2023).

Gao, G. Q. et al. Strain-mediated magnetic properties of epitaxial cobalt ferrite thin films on flexible muscovite. EPL 123, 17002 (2018).

Ha, T. D. et al. Dynamical strain-driven phase separation in flexible CoFe2O4/CoO exchange coupling system. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 12, 46874–46882 (2020).

Cheng, Y. et al. Strain modulation of perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in wrinkle-patterned (Co/Pt)5/BaTiO3 magnetoelectric heterostructures. ACS Nano 16, 11291–11299 (2022).

Gokita, T. et al. Modulation of perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in CoFeB/MgO structure by an application of biaxial tensile strain. Appl. Phys. Express 16, 063001 (2023).

Binasch, G. et al. Enhanced magnetoresistance in layered magnetic structures with antiferromagnetic interlayer exchange. Phys. Rev. B 39, 4828 (1989).

Baibich, M. N. et al. Giant magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472 (1988).

Chen, Y. F. et al. Towards flexible magnetoelectronics: buffer-enhanced and mechanically tunable GMR of Co/Cu multilayers on plastic substrates. Adv. Mater. 20, 3224–3228 (2008).

Melzer, M. et al. Imperceptible magnetoelectronics. Nat. Commun. 6, 6080 (2015).

Karnaushenko, D. et al. High-performance magnetic sensorics for printable and flexible electronics. Adv. Mater. 27, 880–885 (2015).

Makushko, P. et al. Scalable magnetoreceptive e-skin for energy-efficient high-resolution interaction towards undisturbed extended reality. Nat. Commun. 16, 1647 (2025).

Uhrmann, T. et al. Magnetostrictive GMR sensor on flexible polyimide substrates. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 307, 209–211 (2006).

Matsumoto, H. et al. A flexible exchange-biased spin valve for sensing strain direction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 132401 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Magnetostrictive GMR spin valves with composite FeGa/FeCo free layers. AIP Adv. 6, 035206 (2016).

Zhang, J. et al. An ultrathin, rapidly fabricated, flexible giant magnetoresistive electronic skin. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10, 109 (2024).

Bao, B. et al. Active matrix flexible sensory systems: materials, design, fabrication, and integration. Adv. Intell. Syst. 4, 2100253 (2022).

Zhong, D. et al. High-speed and large-scale intrinsically stretchable integrated circuits. Nature 627, 313–320 (2024).

Kondo, M. et al. Imperceptible magnetic sensor matrix system integrated with organic driver and amplifier circuits. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay6094 (2020).

Münzenrieder, N. et al. Entirely flexible on-site conditioned magnetic sensorics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2, 1600188 (2016).

Julliere, M. Tunneling between ferromagnetic films. Phys. Lett. A 54, 225–226 (1975).

Kent, A. D. et al. A new spin on magnetic memories. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 187–191 (2015).

Bhatti, S. et al. Spintronics based random access memory: a review. Mater. Today 20, 530–548 (2017).

Yuan, Y. et al. Review on magnetic/nonmagnetic heterojunction interface effects on spintronic MTJ devices. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 39, 033001 (2024).

Amara, S. et al. High-performance flexible magnetic tunnel junctions for smart miniaturized instruments. Adv. Eng. Mater. 20, 1800471 (2018).

Loong, L. M. et al. Flexible MgO barrier magnetic tunnel junctions. Adv. Mater. 28, 4983–4990 (2016).

Ota, S. et al. Flexible CoFeB/MgO-based magnetic tunnel junctions annealed at high temperature (≥350°C).Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 202401 (2019).

Sun, Y. et al. Electric-field modulation of interface magnetic anisotropy and spin reorientation transition in (Co/Pt)3/PMN-PT heterostructure. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 9, 10855–10864 (2017).

Yu, G. et al. Strain-induced modulation of perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in Ta/CoFeB/MgO structures investigated by ferromagnetic resonance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 072402 (2015).

Chen, A. et al. Using dipole interaction to achieve nonvolatile voltage control of magnetism in multiferroic heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 33, e2105902 (2021).

Sun, W. et al. Electric field control of perpendicular magnetic tunnel junctions with easy-cone magnetic anisotropic free layers. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj8379 (2024).