Abstract

Organisms have to adapt to changes in their environment. Cellular adaptation requires sensing, signalling and ultimately the activation of cellular programs. Metabolites are environmental signals that are sensed by proteins, such as metabolic enzymes, protein kinases and nuclear receptors. Recent studies have discovered novel metabolite sensors that function as gene regulatory proteins such as chromatin associated factors or RNA binding proteins. Due to their function in regulating gene expression, metabolite-induced allosteric control of these proteins facilitates a crosstalk between metabolism and gene expression. Here we discuss the direct control of gene regulatory processes by metabolites and recent progresses that expand our abilities to systematically characterize metabolite-protein interaction networks. Obtaining a profound map of such networks is of great interest for aiding metabolic disease treatment and drug target identification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Metabolites as regulators of gene expression

Organisms must rapidly adapt to environmental changes to survive. They maintain cellular homeostasis by adjusting cellular functions in response to external conditions. Metabolites, which are closely linked to the environment, provide a direct connection between external factors and cellular behavior. Across all domains of life, organisms have evolved various mechanisms to sense metabolites and adjust their cellular programs accordingly. For adaptation to occur, metabolite sensing must lead to changes in metabolic pathway activities. These pathways, comprising interconnected chemical reactions catalyzed by enzymes, are responsible for producing and consuming metabolites essential for cellular functions. The activity of these pathways can be regulated in two primary ways: by adjusting the abundance of metabolic enzymes through gene expression and by directly modifying the activity of these enzymes.

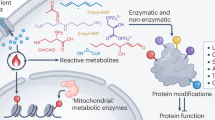

A well-established mechanism for regulating enzyme activity is through allosteric interactions, where a molecule distinct from the enzyme’s substrate induces a conformational change, thereby influencing the enzyme’s function1. This form of regulation, known as allostery, allows one ligand to control a protein’s function, which in turn affects the protein’s interaction with other biomolecules, such as DNA, RNA, or another protein2. In addition to allosteric regulation by transient interactions, metabolites can also influence proteins through post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation, methylation, O-GlcNAcylation or acetylation3. These covalent chemical tags, derived from metabolites, are linked to metabolite availability and can significantly impact gene expression4.

The mechanisms that link metabolic changes to gene expression, however, generally differ between bacteria and eukaryotes in terms of complexity and directness. In bacteria, metabolites often exert a direct influence on RNA and DNA-binding proteins that initiate gene expression changes. For example, bacterial transcription factors can often physically bind metabolites5, as can RNA riboswitches—molecular switches within RNA molecules that bind small metabolites and alter gene expression in response6. Eukaryotic organisms, on the other hand, typically rely on more complex and indirect mechanisms due to the packaging of their genomes in chromatin. In these cells, changes in intracellular metabolite concentrations often affect gene expression through intermediary steps, such as the regulation of epigenetic marks—covalent modifications of histone proteins and nucleic acids4,7. These marks serve as intermediate messengers that translate metabolic states into changes in gene expression. Nevertheless, eukaryotic cells also possess metabolite-sensing transcription factors, such as those in the nuclear receptor family, which can respond immediately to metabolic signals8.

This level of regulation of gene expression by metabolites, that involves transient interactions with gene regulatory proteins, represents one of the most immediate and specific mechanisms for linking metabolism to gene expression. These interactions are reversible and dynamic, allowing cells to quickly adapt to fluctuating metabolic conditions. In this review, we will explore the specific mechanisms of how transcriptional and translational processes are allosterically regulated by small molecule metabolites, and discuss methods available for discovering novel regulatory pathways through the study of metabolite-protein interactions.

Metabolic regulation of the human nucleus: linking metabolites to chromatin function

In human cells the genome is sequestered within the nucleus, an organelle that physically separates the DNA tightly packed in the form of chromatin. This compartmentalization raises the critical question of how are metabolite levels regulated within the nucleus? One possibility is that metabolites can freely diffuse from the cytoplasm into the nucleus through nuclear pores, maintaining a concentration equilibrium between these compartments9. However, emerging evidence suggests that the nucleus may function as a metabolically distinct compartment10,11. Some metabolic enzymes are known to localize within the nucleus, where they directly influence nuclear processes12,13,14,15 playing a role in mammalian zygotic genome activation16 or the regulation of stem cell pluripotency17.

For instance, the enzyme ATP-citrate lyase, which converts acetate and Coenzyme A into Acetyl-CoA, and TCA cycle-related enzymes provide substrates for crucial nuclear reactions, including histone acetylation18,19 and DNA demethylation20. Moreover, metabolic enzymes can bind to chromatin at specific loci, as in the case of the one-carbon metabolic enzyme C1-tetrahydrofolate synthase MTHFD121 and of the adenosylhomocysteinase AHCY22. When bound to specific genomic regions, these enzymes can locally facilitate metabolic processes that drive epigenetic reactions. For example, the acyl-CoA synthetase ACSS2 locally produces Acetyl-CoA for H3 acetylation, promoting the expression of lysosomal and autophagy genes23.

Once metabolites enter the nucleus, they influence gene expression in two key ways. First, they control epigenetic processes by regulating the deposition and removal of epigenetic marks on histones and nucleic acids7,24. These modifications, orchestrated by epigenetic writers, readers, and erasers, play a pivotal role in governing genome functions such as replication, recombination, and transcription25 (Fig. 1). Second, metabolites can physically bind chromatin-associated proteins, acting as alternative substrates, products, or regulators. For instance, inositol phosphate metabolites bind chromatin remodelers like the SWI/SNF complex, modulating their activity26. Inositol phosphate metabolites also bind DNA repair enzymes to stimulate double-strand break repair27,28. ATP and lactate interact with proteins such as the barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF)29 and the anaphase-promoting complex (APC)30, influencing DNA binding and mitotic progression (Fig. 1). These direct, transient interactions enable rapid and dynamic regulation of chromatin structure and function in response to metabolic changes.

Small molecule metabolites derived from exogenous sources or cellular chemical reactions regulate genome function, such as epigenetic modifications, chromatin remodeling and DNA repair. Metabolites can also act on the transcriptional machinery by affecting the translocation of nuclear receptors, by regulating DNA binding of transcription factors or by reconfiguring the interactome of transcription factors and co-regulator complexes. Key pathways include: (1) DNA-binding modulation—metabolites influence transcription factors, altering the DNA-binding capacity of the transcription factors IRF6, CLOCK1 and HIF3A for instance. (2) Interactome reconfiguration—the availability of metabolites modulates the interaction between transcription factors and co-regulators as well as between subunits of co-regulator complexes, affecting transcriptional outcomes. For instance, binding of thyroid hormones to the thyroid hormone receptor promotes binding of co-activators and suppresses co-repressor binding. (3) Chromatin remodeling—metabolite-regulated chromatin remodelers, which for example are regulated by inositol-phosphates, reposition nucleosomes, thereby affecting gene accessibility. (4) Chromatin modifications and DNA repair—metabolic enzymes localized in the nucleus contribute substrates for histone modifications and DNA repair processes. (5) Nuclear metabolism—certain metabolic enzymes are localized within the nucleus, providing essential intermediates for epigenetic modifications and other nuclear functions, such as the Acyl-CoA synthetase ACSS2 which locally produces Acetyl-CoA. (6) Translocation and exogenous molecules—the translocation of metabolites into the nucleus occurs via nuclear pores, while nuclear receptors respond to exogenous molecules, such as hormones and vitamins, linking external signals with nuclear functions.

Regulation of transcription by metabolites

Transcription factors are the class of proteins with the most direct influence on gene expression. The regulation of transcription factors by metabolites establish a crucial link between metabolism and gene regulation. In human cells only a limited number of transcription factors are known to be metabolite-regulated, including those from the nuclear receptor superfamily, the basic helix-loop-helix PER-ARNT-SIM (bHLH-PAS) family and the sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) family (Table 1). The nuclear receptor superfamily, with 48 members, is the most common class of ligand-regulated transcription factors. These proteins typically share a domain structure comprising an unstructured N-terminal domain, a DNA-binding zinc finger domain, a hinge region, and a ligand-binding domain31. Nuclear receptors bind to lipophilic molecules like steroid hormones, vitamin D, or fatty acids. Ligand binding can lead to various functional outcomes, including translocation to the nucleus and interaction with co-regulators, which modulate transcription (Fig. 1).

For example, steroid hormone receptors are stabilized by binding to hormones such as glucocorticoids, androgen or progesterone, which release the receptors from cytosolic chaperones, enabling their translocation to the nucleus32. In the nucleus, these receptors bind to hormone response elements on target genes, profoundly influencing chromatin structure and transcription to regulate biological functions such as reproduction and metabolism8,33. In contrast, thyroid hormone receptors bind to DNA in their ligand-unbound state, and ligand binding induces a switch from recruiting transcriptional repressors to activators34, affecting energy metabolism and behavioral phenotypes such as exploration35.

Beyond nuclear receptors, other transcription factors in humans are regulated by metabolites. For instance, members of the bHLH-PAS transcription factor family, such as CLOCK1, NPAS2 and HIF3A have PAS domains that can sense various small molecules like heme36, carbon monoxide37 or lipids38,39, influencing dimerization and DNA binding. The CLOCK1-BMAL1 and NPAS2-BMAL1 transcription factor complexes bind NAD(H)/NADP(H) in their DNA-binding domains, with the redox state modulating their transcriptional activity40. Additionally, the human interferon-regulatory factor 6 (IRF6), binds glucose via its DNA-binding domain, with glucose influencing IRF6’s ability to dimerize and bind DNA, thereby activating an epidermal differentiation program in keratinocytes41. Similarly, the C2H2 zinc finger MTF-1 senses metal ions with its zinc finger domain, regulating metal homeostasis genes42,43.

Transcription factors that sense metabolites through direct binding are intrinsically regulated by small molecules. Others, however, are more indirectly regulated by physically interacting with metabolite-sensing proteins, such as post-transcriptional modifiers44, proteases45 or E3 ligase complexes46. For instance, HIF1a, a bHLH-PAS transcription factor is hydroxylated in an oxygen-dependent manner. Under normoxic conditions, hydroxylation directs HIF1A for degradation, whereas in hypoxia reduced hydroxylation allows HIF1A to accumulate, translocate to the nucleus and activate hypoxia response genes47. Similarly, the metabolite itaconate regulates the transcription factor NRF2 by inhibiting its degradation, leading to the activation of anti-inflammatory programs in macrophages46 (Fig. 2A). Transcription factors like SREBP1/2 are regulated by proteolytic release and translocation from the endoplasmic reticulum membrane under low sterol conditions (Fig. 2B), while translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus of the Mondo transcription factors (ChREBP and MondoA) is regulated by carbohydrates, modulating lipid biosynthesis45,48 and energy metabolism gene expression49,50 respectively.

A The metabolite itaconate inhibits KEAP1 preventing degradation of NRF2 which activates genes responsible for an anti-inflammatory response. KEAP1 Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1, NRF2 nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, Ub ubiquitin. B SCAP proteolytically releases a transcriptionally active fragment of SREBP1 under low sterol conditions which subsequently translocates to the nucleus regulating the expression of lipid biosynthesis genes. ER endoplasmic reticulum, SREBP1 sterol regulatory-element binding protein, SCAP SREBP cleavage-activating protein, SRE sterol response element.

Once in the nucleus and bound to DNA, transcription factors can recruit co-regulators that either repress or activate transcription through chromatin remodeling or chemical modification or by directly engaging the transcriptional machinery. These co-regulators typically assemble in complexes with transcription factors through protein-protein interactions which can be modulated by metabolites51. For instance, CTBP1 represses transcription by inhibiting histone acetyltransferases, and this activity is regulated by NADH, linking cellular energy levels to transcriptional regulation52,53. Similarly, the metabolic enzyme GAPDH’s role in transcriptional activation is regulated by the NAD/NAD(H) ratio, which modulates its incorporation into the OCA-S complex, affecting the expression of histone genes during the cell cycle54. Additional examples include the co-repressor TRIM28, which is regulated by lactate (Tian et al.55), and the histone deacetylase HDAC3 whose interaction with co-repressors is stabilized by inositol phosphates56.

Once transcribed, RNA molecules undergo post-transcriptional processing steps, such as splicing, nuclear export, and translation. The question remains: Can metabolites also influence these processes?

Crosstalk between RNA function and metabolism

RNA molecules play crucial roles in sensing and regulating metabolic processes within the cell. One way this occurs is through riboswitches, which are specific RNA structures that respond to metabolite binding to regulate transcription, translation, and alternative splicing. Typically located in the 5’ untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNAs, riboswitches consist of a ligand-binding aptamer and juxtaposed RNA sequences that are important for translation initiation such as the Shine-Dalgarno sequence or translation termination sequences57. When a ligand binds a riboswitch, it induces an RNA conformational change that affects the accessibility of the adjacent regulatory RNA sequences, often serving as a feedback mechanism in metabolic pathways58. For instance, the E.coli thiM mRNA, which encodes a metabolic enzyme involved in thiamine phosphate biosynthesis, carries a riboswitch that binds the co-factor thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP). Upon TPP binding the thiM riboswitch changes conformation impeding ribosome binding, thus linking TPP levels to expression of thiamine phosphate biosynthesis genes59 (Fig. 3A). Although more than 55 riboswitch classes have been identified, only one has been found in eukaryotes, the TPP riboswitch class, and none in vertebrates60, raising the question: How do eukaryotes integrate metabolic signals into their post-transcriptional gene regulation programs?

Metabolites can affect translation by binding to riboswitches. A Binding of the metabolite thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) to the thiM riboswitch induces a conformational change masking the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD) inhibiting ribosome binding and translation initiation. B RNA molecules can inhibit metabolic enzymes such as the glycolytic enzyme ENO1 which is relevant for mESC differentiation. C Metabolites can allosterically regulate RNA-binding proteins. Unsaturated lipids allosterically inhibit RNA binding of MSI1 which leads to the translational down-regulation of the lipid biosynthesis enzyme SCD and to changes in lipid metabolism. mESC mouse embryonic stem cells, MSI1 Musashi 1, SCD steaoryl-Coa desaturase 1.

Metabolic enzymes binding RNA

One answer lies in the discovery of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that are regulated by metabolites. For example, the iron-regulatory protein 1 (IRP1), which binds RNA in response to iron levels, regulates iron homeostasis in eukaryotes. IRP1 binds to specific RNA structures in the UTRs of mRNAs encoding iron metabolism proteins, adjusting their expression in response to iron scarcity. Interestingly, IRP1 is also a cytoplasmic homolog of the mitochondrial enzyme aconitase, exemplifying a “moonlighting” function where a metabolic enzyme also serves as an RBP61. This dual function—as metabolite- and RNA-interactor—is not unique to IRP1; other metabolic enzymes also facilitate crosstalk between metabolism and RNA function62,63,64,65,66. By regulating the RNA-binding activity of these enzymes, metabolites can influence the stability or translation of target RNAs. For instance, in T-cell activation, a metabolic switch modulates the RNA-binding activity of GAPDH, controlling the translation of an immune cytokine67 and the autoregulation of thymidylate synthase expression68. Additionally, RNA molecules can regulate the activity of metabolic enzymes, a phenomenon known as “riboregulation”63. An example of this occurs in glycolysis, where RNA inhibits the catalytic activity of enolase, playing a significant role in cell differentiation69 (Fig. 3B).

Advances in RNA-binding protein capture techniques combined with proteomics have revealed that many more metabolic enzymes bind RNA across various species, both in cell culture models and tissues70,71,72,73,74. These proteomics-based studies provide evidence for RNA binding of more than 40% of all metabolic enzymes75. These findings raise important questions: How do these enzymes interact with RNA? Do they bind specific RNA sequences, or is their binding nonspecific? And what are the cellular functions of these interactions? Initial studies mapping RNA-binding regions in proteins have shown that metabolic enzymes tend to interact with RNA near their active sites, often through nucleotide-binding domains such as the Rossmann fold76,77. However, understanding the biochemical details of these interactions requires structural insights. Recently, the structure of the metabolic enzyme SHMT1 bound to RNA was resolved, confirming its interaction with RNA close to its active site78.

Modulation of canonical RNA binding protein activity by metabolites

Canonical RNA-binding proteins, which typically have well-characterized RNA-binding domains, are increasingly recognized as potential metabolite sensors79. For example, Musashi 1 (MSI1), a well-known RBP, was found to have its RNA-binding activity allosterically inhibited by fatty acids, which in turn affects the translation of lipid biosynthesis genes80 (Fig. 3C). Similarly, other metabolites such as UDP-glucose and ATP have been shown to regulate the activity of canonical RBPs like HuR81, FUS82,83, CIRBP84, TDP-4385, and HNRNPA186 with these interactions impacting processes such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition81 and the formation of phase condensates84.

In addition to these examples, the amino acid arginine has been found to interact with the RNA-binding protein RBM39, which controls the expression of metabolic genes in liver cancer cells, thereby promoting tumor formation87. Arginine also interacts with RNA-binding proteins involved in mRNA splicing, such as RNA helicases88, although the impact of this interaction on gene expression is not fully understood. In general, the interactions between RNA-binding proteins and metabolites can play a significant role in splicing regulation89. For example, glucose binds to the ATP-binding site of the RNA helicase DDX21, inhibiting its ability to form homodimers. This leads to the incorporation of DDX21 into splicing complexes involved in epidermal differentiation90, further emphasizing the emerging role of splicing as a target for metabolic regulation.

Interestingly, RNA-binding domains in proteins like HuR and CIRBP play a crucial role in metabolite interactions. The RRM domain in HuR binds UDP-glucose, preventing RNA interaction and altering gene expression81. Similarly, ATP binds to CIRBP’s RRM domain, competing with RNA in vitro84. However, it remains unclear how common it is for metabolites to bind directly to canonical RNA-binding domains or other regions in RBPs. Clarifying these structural details is crucial for understanding how RNA-binding domains and other RBPs regions integrate metabolic signals and influence post-transcriptional processes. This understanding also has significant implications for drug development. Several compounds have been designed to modulate RNA-binding protein interactions91,92. For instance, inhibitors targeting the RNA-binding protein HuR, such as the small molecule MS-444, prevent HuR from binding to its RNA targets, which has shown promise in reducing tumor growth in certain cancers93 and small molecule modulators of splicing, such as Risidiplam that has been approved for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy94. These examples highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting RNA-binding proteins and their interactions with metabolites or RNA.

Methods for characterizing metabolite-protein interactions

There are well-established methods for systematically profiling protein-protein, nucleic acid-protein, and drug-protein interactions. However, profiling metabolite-protein interactions remains particularly challenging, due to key differences in their chemical properties. Metabolite-protein interactions often have low affinity, which complicates detection. Additionally, the chemical diversity of metabolites makes designing a universal profiling strategy difficult. Furthermore, their small size makes them hard to modify while retaining activity. Therefore, effective methods must capture low-affinity interactions, be agnostic to metabolite chemistry, and avoid the need for modification. Recently, several tools have been developed that meet these criteria (also reviewed here95,96,97,98,99). Here, we provide an update on the most recent developments (Fig. 4).

Summary of metabolite-protein interaction profiling technique categorized in protein-centric, metabolite-centric and interactome-wide approaches. MIDAS mass spectrometry integrated with equilibrium dialysis for the discovery of allostery systematically, NMR nuclear magnetic resonance, AP-MS affinity purification-mass spectrometry, DARTS drug affinity responsive target stability, LiP-MS limited-proteolysis coupled to mass spectrometry, CETSA cellular thermal shift assay, TPP thermal proteome profiling, Tm melting temperature, PROMIS protein-metabolite interaction using size selection, LC-MS/MS liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, AI artificial intelligence, SIMMER systematic identification of meaningful metabolic enzyme regulation.

Pull-down strategies have been effective for characterizing protein-protein100 and drug-protein interactions101,102, but are less commonly used for interrogating metabolite-protein interactions. This is partly due to the difficulty of immobilizing small and chemically diverse metabolites. However, photo-immobilization using diazirine photochemistry has addressed some of these challenges103,104. Upon UV irradiation, diazirines convert into carbenes, which readily insert into C-H bonds and other chemical groups105, allowing metabolites to be immobilized without prior modification. This method has been used to profile the interactomes of natural products and co-factors in both human and E. coli proteomes, showing FAD binding of a subset of human RNA-binding proteins106. While this approach enhances metabolite-centric pull-downs, it still relies on metabolite immobilization. Alternatively, protein tagging allows for the enrichment of proteins via affinity purification, with bound metabolites identified through LC-MS/MS107. However, this approach still requires modification of the protein bait into a fusion protein with an affinity tag.

Modern chemical proteomics workflows now focus on individual metabolites and their interactomes within the entire proteome. These methods exploit the principle that metabolite binding alters the biophysical properties of proteins. One such change is the shift in protein melting temperature when a ligand binds. The cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) was first introduced to measure ligand-induced shifts in protein thermal stability108. This approach has since been adapted for use with mass spectrometry-based proteomics for protein quantification in techniques like thermal proteome profiling (TPP)109 or thermal stability profiling110. TPP has been successfully applied to map the ATP-protein interactome29 and the lactate-protein interactome discovering its role in the regulation of the anaphase-promoting complex30. Moreover, TPP has identified metal-binding proteins in lysates111,112 and allowed the detection of changes in metabolite-protein interactions in living cells113. Ligand binding also affects protein structural states, which can be detected through proteolysis using broad-spectrum proteases. Ligand-bound proteins are more resistant to proteolysis, a principle exploited in techniques like drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS)114 and limited proteolysis coupled to mass spectrometry (LiP-MS)115. Chemical footprinting techniques further assess conformational changes by detecting alterations in the chemical reactivity of solvent exposed amino acid side chains116.

These chemoproteomics approaches have been used in various studies to map metabolite-protein interactomes, such as central carbon metabolites in E. coli117 and glycolytic metabolites in mammalian cell lysates55 and for profiling the ATP interactome in yeast118,119. While TPP generally provides insights into a larger fraction of the human proteome, LiP-MS and chemical footprinting offer spatial resolution, pinpointing specific protein regions involved in metabolite binding. Since chemical proteomics methods provide insights into the interactome of a single metabolite, profiling multiple metabolites is time-consuming and costly. However, advances in high-throughput proteomics are making large-scale mapping of metabolite-protein interactions increasingly feasible120,121,122,123.

Mapping metabolite-protein interactions on a large scale is possible, though it often involves analyzing one recombinant protein at a time using mass spectrometry-based metabolomics124 or nuclear magnetic resonance125,126. One notable technique is MIDAS (Mass spectrometry integrated with equilibrium dialysis for the discovery of allostery systematically), which has been used to discover allosteric regulators of enzymes involved in human carbohydrate metabolism127. MIDAS works by using equilibrium dialysis: a library of 401 metabolites is added to two chambers separated by a dialysis membrane. One chamber contains the purified protein, which is too large to diffuse across the membrane. Metabolites can equilibrate freely between the chambers, but those that bind to the protein accumulate in the protein-containing chamber. This allows researchers to identify metabolite-protein interactions by comparing the metabolite concentrations between the two chambers using mass spectrometry124,127. While MIDAS is effective for screening large numbers of metabolites, it is limited to proteins that can be purified with high purity. Another method, PROMIS, does not require protein purification and instead uses size-exclusion chromatography followed by proteomics and metabolomics analyses to infer metabolite-protein interactions128.

In contrast to purely experimental approaches, structural bioinformatics and artificial intelligence (AI) offer new ways to predict metabolite-protein interactions. Advances such as RoseTTAFold ALL-Atom129 and AlphaFold 3130 provide frameworks for predicting interactions across proteomes. Although these AI-based methods have shown promise, they require further experimental validation.

All methods discussed here infer metabolite-protein interactions from biochemical and biophysical experiments or computational models. However, these approaches are often limited as they do not manipulate metabolite levels in vivo. The complexity of living cells or organisms makes it challenging to separate effects due to metabolite-protein interactions from downstream events. Instead, combining -omics technologies and mathematical modeling can help disentangle these effects131, as demonstrated in studies that predict the protein metabolite network from measurement of metabolite levels and transcription factor activity132,133.

Future perspective

While significant progress has been made in understanding how metabolism influences gene expression, a comprehensive overview of the crosstalk between metabolism and the proteome in human biology remains elusive. Throughout this review, we have highlighted numerous examples demonstrating that such a link exists, explored the underlying mechanisms, and discussed how pervasively metabolites regulate multiple layers of gene expression—including transcription8,40,41,46,48, RNA splicing89, and translation79,80. In bacteria, much more is known about the metabolome-proteome network. For example, approximately 30% of the 300 transcription factors in E. coli5 are allosterically regulated by metabolites, whereas in humans, only around 3% of the 1,600 transcription factors have been shown to engage in similar interactions134. This difference reflects the fundamentally distinct regulatory landscapes of bacteria and humans. In prokaryotes, the absence of compartmentalization, chromatin packaging, and epigenetic mechanisms allows for a more direct and immediate integration of metabolic signals into gene regulation. In humans, mechanisms such as epigenetic modifications, though crucial for gene regulation, tend to be more indirect compared to the small molecule regulation of transcription factors in bacteria. However, despite these differences, the basic logic of metabolite-induced modulation of DNA binding and protein-protein interactions is conserved across species. This suggests that metabolite-sensing transcription factors may also be more widespread in humans than currently recognized, with many yet to be discovered.

In addition, recent work has highlighted the intricate link between metabolism and translation, revealing how metabolic pathways not only provide energy for protein synthesis but also regulate the selectivity and efficiency of the translational machinery. For example, metabolic states, such as nutrient availability, can directly influence mRNA translation through pathways like mTOR and AMPK, which modulate key initiation factors79. Furthermore, metabolites themselves can act as signaling molecules, altering translational control to meet the demands of cellular physiology.

Technological advances now enable systematic searches for these regulatory interactions using a combination of experimental and computational approaches. We speculate that mapping the human metabolite-protein interactome in greater detail will reveal novel pathways linking metabolism to gene expression via gene regulatory proteins, such as metabolite-controlled transcription factors, chromatin remodelers, splicing regulators, and RNA-binding proteins. These interactions will likely have allosteric effects on protein functions, influencing nucleic acid binding, enzymatic activity, protein translation or protein-protein interactions. Therefore, it is essential not only to profile metabolite-protein interactions but also to investigate their impact on broader biomolecular networks.

Taken together, understanding these interactions will provide new insights into the complex regulatory networks that integrate metabolism with gene expression, potentially uncovering novel therapeutic targets in diseases where metabolism and gene regulation are dysregulated.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ACSS2:

-

Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase 2

- AHCY:

-

Adenosylhomocysteinase

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- AMPK:

-

AMP-activated protein kinase

- APC:

-

Anaphase promoting complex

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- BAF:

-

Barrier-to-autointegration factor

- bHLH-PAS:

-

Basic helix-loop-helix PER-ARNT-SIM

- BMAL1:

-

Basic helix-loop-helix ARNT-like protein 1

- bZIP:

-

Basic leucine zipper

- CETSA:

-

Cellular thermal shift assay

- ChREBP:

-

Carbohydrate response element binding protein

- CIRBP:

-

Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein

- CLOCK:

-

Circadian locomotor output cycles kaput

- CoA:

-

Coenzyme A

- CTBP1:

-

C-terminal binding protein 1

- DARTS:

-

Drug affinity responsive target stability

- DDX21:

-

DEAD box protein 2

- ENO1:

-

Enolase 1

- FAD:

-

Flavin adenine dinucleotide

- FUS:

-

RNA-binding protein FUS

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceradehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HDAC3:

-

Histone deacetylase 3

- HNRNPA1:

-

Heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1

- HIF1a:

-

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha

- HIF3a:

-

Hypoxia-inducible factor 3 alpha

- HuR:

-

Hu-antigen R

- IRF6:

-

Interferon-regulatory factor 6

- IRP1:

-

Iron-regulatory protein 1

- KEAP1:

-

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- LC-MS/MS:

-

Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry

- LiP-MS:

-

Limited-proteolysis coupled to mass spectrometry

- mESC:

-

Mouse embryonic stem cells

- MLX:

-

Max-like protein X

- MIDAS:

-

Mass spectrometry integrated with equilibrium dialysis for the discovery of allostery systematically)

- MSI1:

-

Musashi 1

- MTHFD1:

-

C-1-tetrahydrofolate synthase

- MTF-1:

-

Metal regulatory transcription factor 1

- mTOR:

-

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- NAD:

-

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NADP:

-

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NMR:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- NPAS2:

-

Neuronal PAS domain protein 2

- NRF2:

-

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- OCA-S:

-

Oct-1 coactivator in S-phase

- PROMIS:

-

Protein-metabolite interaction using size selection

- PTM:

-

Post-translational modification

- RBP:

-

RNA-binding protein

- RRM:

-

RNA-recognition motif

- SCAP:

-

SREBP cleavage-activating protein

- SCD:

-

Steaoryl-Coa desaturase 1

- SHMT1:

-

Serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1

- SIMMER:

-

Systematic identification of meaningful metabolic enzyme regulation

- SRE:

-

Sterol response element

- SREBP:

-

Sterol regulatory element binding protein

- SWI/SNF:

-

Switch/sucrose non-fermentable

- TCA:

-

Tricarboxylic acid

- TDP-43:

-

TAR DNA-binding protein 43

- TPP (Metabolite):

-

Thiamin pyrophosphate

- TPP (Method):

-

Thermal proteome profiling

- TRIM28:

-

Transcription intermediary factor 1 beta

- TRIM/RBCC:

-

Emerging tripartite motif/N-terminal RING finger/B-box/coiled-coil

- UTR:

-

Untranslated region

References

Monod, J., Changeux, J. P. & Jacob, F. Allosteric proteins and cellular control systems. J. Mol. Biol. 6, 306–329 (1963).

Fenton, A. W. Allostery: an illustrated definition for the ‘second secret of life’. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 420–425 (2008).

Figlia, G., Willnow, P. & Teleman, A. A. Metabolites regulate cell signaling and growth via covalent modification of proteins. Dev. Cell 54, 156–170 (2020).

Dai, Z., Ramesh, V. & Locasale, J. W. The evolving metabolic landscape of chromatin biology and epigenetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-0270-8 (2020).

Ledezma-Tejeida, D., Schastnaya, E. & Sauer, U. Metabolism as a signal generator in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 28, 100404 (2021).

Pavlova, N., Kaloudas, D. & Penchovsky, R. Riboswitch distribution, structure, and function in bacteria. Gene 708, 38–48 (2019).

Reid, M. A., Dai, Z. & Locasale, J. W. The impact of cellular metabolism on chromatin dynamics and epigenetics. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 1298–1306 (2017).

Scholtes, C. & Giguère, V. Transcriptional control of energy metabolism by nuclear receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 750–770 (2022).

Wente, S. R. & Rout, M. P. The nuclear pore complex and nuclear transport. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000562 (2010).

Boon, R. Metabolic fuel for epigenetic: nuclear production meets local consumption. Front. Genet. 12, 768996 (2021).

Boon, R., Silveira, G. G. & Mostoslavsky, R. Nuclear metabolism and the regulation of the epigenome. Nat. Metab. 2, 1190–1203 (2020).

Boukouris, A. E., Zervopoulos, S. D. & Michelakis, E. D. Metabolic enzymes moonlighting in the nucleus: metabolic regulation of gene transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci. 41, 712–730 (2016).

Kourtis, S. et al. Comprehensive chromatome profiling identifies metabolic enzymes on chromatin in healthy and cancer cells. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.06.570368 (2023).

Kafkia, E. et al. Operation of a TCA cycle subnetwork in the mammalian nucleus. Sci. Adv. 8 https://www.science.org (2022).

Li, X., Egervari, G., Wang, Y., Berger, S. L. & Lu, Z. Regulation of chromatin and gene expression by metabolic enzymes and metabolites. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 563–578 (2018).

Nagaraj, R. et al. Nuclear localization of mitochondrial TCA cycle enzymes as a critical step in mammalian zygotic genome activation. Cell 168, 210–223.e11 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Nuclear localization of mitochondrial TCA cycle enzymes modulates pluripotency via histone acetylation. Nat. Commun. 13, 7414 (2022).

Wellen, K. E. et al. ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science324, 1076–1080 (2009).

Sutendra, G. et al. A nuclear pyruvate dehydrogenase complex is important for the generation of Acetyl-CoA and histone acetylation. Cell 158, 84–97 (2014).

Traube, F. R. et al. Redirected nuclear glutamate dehydrogenase supplies Tet3 with α-ketoglutarate in neurons. Nat. Commun. 12, 4100 (2021).

Sdelci, S. et al. MTHFD1 interaction with BRD4 links folate metabolism to transcriptional regulation. Nat. Genet. 51, 990–998 (2019).

Aranda, S. et al. Chromatin capture links the metabolic enzyme AHCY to stem cell proliferation. Sci. Adv. 5, 1–14 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Nucleus-translocated ACSS2 promotes gene transcription for lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy. Mol. Cell 66, 684–697.e9 (2017).

Suganuma, T. & Workman, J. L. Chromatin and Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87, 27–49 (2018).

Millán-Zambrano, G., Burton, A., Bannister, A. J. & Schneider, R. Histone post-translational modifications—cause and consequence of genome function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 563–580 (2022).

Shen, X., Xiao, H., Ranallo, R., Wu, W. H. & Wu, C. Modulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes by inositol polyphosphates. Science 299, 112–114 (2003).

Hanakahi, L. A., Bartlet-Jones, M., Chappell, C., Pappin, D. & West, S. C. Binding of inositol phosphate to DNA-PK and stimulation of double-strand break repair. Cell 102, 721–729 (2000).

Hanakahi, L. A. & West, S. C. Specific interaction of IP6 with human Ku70/80, the DNA-binding subunit of DNA-PK. EMBO J. 21, 2038–2044 (2002).

Sridharan, S. et al. Proteome-wide solubility and thermal stability profiling reveals distinct regulatory roles for ATP. Nat. Commun. 10, 1155 (2019).

Liu, W. et al. Lactate regulates cell cycle by remodeling the anaphase promoting complex. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05939-3 (2023).

Weikum, E. R., Liu, X. & Ortlund, E. A. The nuclear receptor superfamily: a structural perspective. Protein Sci. 27, 1876–1892 (2018).

Pratt, W. B., Galigniana, M. D., Morishima, Y. & Murphy, P. J. M. Role of molecular chaperones in steroid receptor action. Essays Biochem. 40, 41–58 (2004).

Aranda, A. & Pascual, A. Nuclear Hormone Receptors and Gene Expression. Physiol. Rev. 81, 1269–1304 (2001).

Grøntved, L. et al. Transcriptional activation by the thyroid hormone receptor through ligand-dependent receptor recruitment and chromatin remodelling. Nat. Commun. 6, 7048 (2015).

Hochbaum, D. R. et al. Thyroid hormone remodels cortex to coordinate body-wide metabolism and exploration. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.07.041 (2024).

Freeman, S. L. et al. Heme binding to human CLOCK affects interactions with the E-box. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19911–19916 (2019).

Dioum, E. M. et al. NPAS2: A gas-responsive transcription factor. Science298, 2385–2387 (2002).

Diao, X. et al. Identification of oleoylethanolamide as an endogenous ligand for HIF-3α. Nat. Commun. 13, 2529 (2022).

Wu, D., Su, X., Potluri, N., Kim, Y. & Rastinejad, F. NPAS1-ARNT and NPAS3-ARNT crystal structures implicate the bHLH-PAS family as multi-ligand binding transcription factors. Elife 5, e18790 (2016).

Rutter, J., Reick, M., Wu, L. C. & McKnight, S. L. Regulation of clock and NPAS2 DNA binding by the redox state of NAD cofactors. Science293, 510–514 (2001).

Lopez-Pajares, V. et al. Glucose modulates transcription factor dimerization to enable tissue differentiation. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.28.518222 (2022).

Laity, J. H. & Andrews, G. K. Understanding the mechanisms of zinc-sensing by metal-response element binding transcription factor-1 (MTF-1). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 463, 201–210 (2007).

Günther, V., Lindert, U. & Schaffner, W. The taste of heavy metals: gene regulation by MTF-1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1823, 1416–1425 (2012).

Fong, G. H. & Takeda, K. Role and regulation of prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Cell Death Differ. 15, 635–641 (2008).

Wang, X., Sato, R., Brown, M. S., Hua, X. & Goldsteln, J. L. SREBP-1, a membrane-bound transcription factor released by sterol-regulated proteolysis. Cell 77, 53–62 (1994).

Mills, E. L. et al. Itaconate is an anti-inflammatory metabolite that activates Nrf2 via alkylation of KEAP1. Nature 556, 113–117 (2018).

Weidemann, A. & Johnson, R. S. Biology of HIF-1α. Cell Death Differ. 15, 621–627 (2008).

Eberlé, D., Hegarty, B., Bossard, P., Ferré, P. & Foufelle, F. SREBP transcription factors: master regulators of lipid homeostasis. Biochimie 86, 839–848 (2004).

Postic, C., Dentin, R., Denechaud, P. D. & Girard, J. ChREBP, a transcriptional regulator of glucose and lipid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 27, 179–192 (2007).

Havula, E. & Hietakangas, V. Glucose sensing by ChREBP/MondoA-Mlx transcription factors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 640–647 (2012).

Shi, Y. & Shi, Y. Metabolic enzymes and coenzymes in transcription—a direct link between metabolism and transcription? Trends Genet. 20, 445–452 (2004).

Kim, J. H., Cho, E. J., Kim, S. T. & Youn, H. D. CtBP represses p300-mediated transcriptional activation by direct association with its bromodomain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 423–428 (2005).

Kumar, V. et al. Transcription corepressor CtBP Is an NAD + -regulated dehydrogenase. Mol. Cell 10, 857–869 (2002).

Zheng, L., Roeder, R. G. & Luo, Y. S Phase activation of the histone H2B promoter by OCA-S, a coactivator complex that contains GAPDH as a key component. Cell 114, 255–266 (2003).

Tian, Y. et al. Chemoproteomic mapping of the glycolytic targetome in cancer cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-023-01355-w (2023).

Watson, P. J., Fairall, L., Santos, G. M. & Schwabe, J. W. R. Structure of HDAC3 bound to co-repressor and inositol tetraphosphate. Nature 481, 335–340 (2012).

Serganov, A. & Patel, D. J. Molecular recognition and function of riboswitches. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 22, 279–286 (2012).

Roth, A. & Breaker, R. R. The structural and functional diversity of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 305–334 (2009).

Serganov, A., Polonskaia, A., Phan, A. T., Breaker, R. R. & Patel, D. J. Structural basis for gene regulation by a thiamine pyrophosphate-sensing riboswitch. Nature 441, 1167–1171 (2006).

Kavita, K. & Breaker, R. R. Discovering riboswitches: the past and the future. Trends Biochem. Sci. 48, 119–141 (2023).

Hentze, M. W. & Kühn, L. C. Molecular control of vertebrate iron metabolism: mRNA-based regulatory circuits operated by iron, nitric oxide, and oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93, 8175–8182 (1996).

Castello, A., Hentze, M. W. & Preiss, T. Metabolic enzymes enjoying new partnerships as RNA-binding proteins. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 26, 746–757 (2015).

Hentze, M. W., Castello, A., Schwarzl, T. & Preiss, T. A brave new world of RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 327–341 (2018).

Hentze, M. W. & Preiss, T. The REM phase of gene regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 35, 423–426 (2010).

Curtis, N. J. & Jeffery, C. J. The expanding world of metabolic enzymes moonlighting as RNA binding proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 49, 1099–1108 (2021).

Wegener, M. & Dietz, K.-J. The mutual interaction of glycolytic enzymes and RNA in post-transcriptional regulation. RNA 28, 1446–1468 (2022).

Chang, C. H. et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell 153, 1239 (2013).

Chu, E. et al. Autoregulation of human thymidylate synthase messenger RNA translation by thymidylate synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 8977–8981 (1991).

Huppertz, I. et al. Riboregulation of Enolase 1 activity controls glycolysis and embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mol. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2022.05.019 (2022).

Beckmann, B. M. et al. The RNA-binding proteomes from yeast to man harbour conserved enigmRBPs. Nat. Commun. 6, 10127 (2015).

Queiroz, R. M. L. et al. Comprehensive identification of RNA–protein interactions in any organism using orthogonal organic phase separation (OOPS). Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 169–178 (2019).

Trendel, J. et al. The human RNA-binding proteome and its dynamics during translational arrest. Cell 176, 391–403.e19 (2019).

Urdaneta, E. C. et al. Purification of cross-linked RNA-protein complexes by phenol-toluol extraction. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–17 (2019).

Perez-Perri, J. I. et al. The RNA-binding protein landscapes differ between mammalian organs and cultured cells. Nat. Commun. 14, 2074 (2023).

Caudron-Herger, M., Jansen, R. E., Wassmer, E. & Diederichs, S. RBP2GO: a comprehensive pan-species database on RNA-binding proteins, their interactions and functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D425–D436 (2021).

Castello, A. et al. Comprehensive identification of RNA-binding domains in human cells. Mol. Cell 63, 696–710 (2016).

Nagy, E. & Rigby, W. F. C. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase selectively binds AU-rich RNA in the NAD + -binding region (Rossmann fold). J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2755–2763 (1995).

Spizzichino, S. et al. Structure-based mechanism of riboregulation of the metabolic enzyme SHMT1. Mol. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2024.06.016 (2024).

Biffo, S., Ruggero, D. & Santoro, M. M. The crosstalk between metabolism and translation. Cell Metab. 36, 1945–1962 (2024).

Clingman, C. C. et al. Allosteric inhibition of a stem cell RNA-binding protein by an intermediary metabolite. Elife 3, 1–26 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. UDP-glucose accelerates SNAI1 mRNA decay and impairs lung cancer metastasis. Nature 571, 127–131 (2019).

Kang, J., Lim, L., Lu, Y. & Song, J. A unified mechanism for LLPS of ALS/FTLD-causing FUS as well as its modulation by ATP and oligonucleic acids. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000327 (2019).

Kang, J., Lim, L. & Song, J. ATP binds and inhibits the neurodegeneration-associated fibrillization of the FUS RRM domain. Commun. Biol. 2, 223 (2019).

Zhou, Q. et al. ATP regulates RNA-driven cold inducible RNA binding protein phase separation. Protein Sci. 30, 1438–1453 (2021).

Dang, M., Lim, L., Kang, J. & Song, J. ATP biphasically modulates LLPS of TDP-43 PLD by specifically binding arginine residues. Commun. Biol. 4, 714 (2021).

Dang, M., Li, Y. & Song, J. Tethering-induced destabilization and ATP-binding for tandem RRM domains of ALS-causing TDP-43 and hnRNPA1. Sci. Rep. 11, 1034 (2021).

Mossmann, D. et al. Arginine reprograms metabolism in liver cancer via RBM39. Cell 186, 5068–5083.e23 (2023).

Geiger, R. et al. L-Arginine modulates T cell metabolism and enhances survival and anti-tumor activity. Cell 167, 829–842.e13 (2016).

Cui, H., Shi, Q., Macarios, C. M. & Schimmel, P. Metabolic regulation of mRNA splicing. Trends Cell Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2024.02.002 (2024).

Miao, W. et al. Glucose dissociates DDX21 dimers to regulate mRNA splicing and tissue differentiation. Cell 186, 80–97.e26 (2023).

Wu, P. Inhibition of RNA-binding proteins with small molecules. Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 441–458 (2020).

Childs-Disney, J. L. et al. Targeting RNA structures with small molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-022-00521-4 (2022).

Campagne, S. et al. Structural basis of a small molecule targeting RNA for a specific splicing correction. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 1191–1198 (2019).

Ratni, H., Scalco, R. S. & Stephan, A. H. Risdiplam, the first approved small molecule splicing modifier drug as a blueprint for future transformative medicines. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 12, 874–877 (2021).

Diether, M. & Sauer, U. Towards detecting regulatory protein-metabolite interactions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 39, 16–23 (2017).

Li, S. & Shui, W. Systematic mapping of protein–metabolite interactions with mass spectrometry-based techniques. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 64, 24–31 (2020).

Venegas-Molina, J., Molina-Hidalgo, F. J., Clicque, E. & Goossens, A. Why and How to Dig into Plant Metabolite-Protein Interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 26, 472–483 (2021).

Zhao, T. et al. Prediction and collection of protein–metabolite interactions. Brief. Bioinform 00, 1–10 (2021).

Kurbatov, I., Dolgalev, G., Arzumanian, V., Kiseleva, O. & Poverennaya, E. The knowns and unknowns in protein–metabolite interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 4155 (2023).

Cho, N. H. et al. OpenCell: endogenous tagging for the cartography of human cellular organization. Science 375, eabi6983 (2022).

Klaeger, S. et al. The target landscape of clinical kinase drugs. Science 358, eaan4368-18 (2017).

Lechner, S. et al. Target deconvolution of HDAC pharmacopoeia reveals MBLAC2 as common off-target. Nat. Chem. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-022-01015-5 (2022).

Kanoh, N. et al. Immobilization of natural products on glass slides by using a photoaffinity reaction and the detection of protein-small-molecule interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 5584–5587 (2003).

Kanoh, N., Honda, K., Simizu, S., Muroi, M. & Osada, H. Photo-cross-linked small-molecule affinity matrix for facilitating forward and reverse chemical genetics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 3559–3562 (2005).

Ford, F., Yuzawa, T., Platz, M. S., Matzinger, S. & Fülscher, M. Rearrangement of dimethylcarbene to propene: study by laser flash photolysis and ab initio molecular orbital theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 4430–4438 (1998).

Prokofeva, P. et al. Merits of diazirine photo-immobilization for target profiling of natural products and cofactors. ACS Chem. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.2c00500 (2022).

Li, X., Gianoulis, T. A., Yip, K. Y., Gerstein, M. & Snyder, M. Extensive in vivo metabolite-protein interactions revealed by large-scale systematic analyses. Cell 143, 639–650 (2010).

Molina, D. M. et al. Monitoring drug target engagement in cells and tissues using the cellular thermal shift assay. Science 341, 84–87 (2013).

Savitski, M. M. et al. Tracking cancer drugs in living cells by thermal profiling of the proteome. Science 346, 1255784–1255784 (2014).

Huber, K. V. M. et al. Proteome-wide drug and metabolite interaction mapping by thermal-stability profiling. Nat. Methods. 12, 1055–1057 (2015).

Zeng, X. et al. Discovery of metal-binding proteins by thermal proteome profiling. Nat. Chem. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-024-01563-y (2024).

Locke, T. M. et al. High-throughput identification of calcium regulated proteins across diverse proteomes. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.18.575273 (2024).

Mateus, A. et al. The functional proteome landscape of Escherichia coli. Nature 588, 473–478 (2020).

Lomenick, B. et al. Target identification using drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21984–21989 (2009).

Feng, Y. et al. Global analysis of protein structural changes in complex proteomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1036–1044 (2014).

Son, A., Pankow, S., Bamberger, T. C. & Yates, J. R. Quantitative structural proteomics in living cells by covalent protein painting. Methods Enzymol. 679, 33–63 (2023).

Piazza, I. et al. A map of protein-metabolite interactions reveals principles of chemical communication. Cell 172, 358–372.e23 (2018).

Geer, M. A. & Fitzgerald, M. C. Characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATP-Interactome using the iTRAQ-SPROX Technique. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 27, 233–243 (2016).

Tran, D. T., Adhikari, J. & Fitzgerald, M. C. StableIsotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)-based strategy for proteome-wide thermodynamic analysis of protein-ligand binding interactions. Mol. Cell Proteom. 13, 1800–1813 (2014).

Bian, Y. et al. Robust, reproducible and quantitative analysis of thousands of proteomes by micro-flow LC–MS/MS. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–12 (2020).

Messner, C. B. et al. Ultra-fast proteomics with Scanning SWATH. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-021-00860-4 (2021).

Stewart, H. I. et al. Parallelized acquisition of orbitrap and astral analyzers enables high-throughput quantitative analysis. Anal. Chem. 95, 15656–15664 (2023).

Kaspar-Schoenefeld, S. et al. High-throughput proteome profiling with low variation in a multi-center study using dia-PASEF. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.29.596405 (2024).

Orsak, T. et al. Revealing the allosterome: systematic identification of metabolite–protein interactions. Biochemistry 51, 225–232 (2012).

Diether, M., Nikolaev, Y., Allain, F. H. & Sauer, U. Systematic mapping of protein-metabolite interactions in central metabolism of Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 15, e9008 (2019).

Nikolaev, Y. V., Kochanowski, K., Link, H., Sauer, U. & Allain, F. H. T. Systematic identification of protein-metabolite interactions in complex metabolite mixtures by ligand-detected nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry 55, 2590–2600 (2016).

Hicks, K. G. et al. Protein-metabolite interactomics of carbohydrate metabolism reveal regulation of lactate dehydrogenase. Science 12 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abm3452 (2023).

Veyel, D. et al. PROMIS, global analysis of PROtein-metabolite interactions using size separation in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 12440–12453 (2018).

Krishna, R. et al. Generalized biomolecular modeling and design with RoseTTAFold All-Atom. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adl2528 (2024).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Haas, R. et al. Designing and interpreting ‘multi-omic’ experiments that may change our understanding of biology. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 6, 37–45 (2017).

Lempp, M. et al. Systematic identification of metabolites controlling gene expression in E. coli. Nat. Commun. 10, 4463 (2019).

Hackett, S. R. et al. Systems-level analysis of mechanisms regulating yeast metabolic flux. Science 354, aaf2786 (2016).

Lambert, S. A. et al. The human transcription factors. Cell 172, 650–665 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.P. and M.H. wrote the main manuscript text and M.H. prepared Figs. 1–4 and Table 1. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hornisch, M., Piazza, I. Regulation of gene expression through protein-metabolite interactions. npj Metab Health Dis 3, 7 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44324-024-00047-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44324-024-00047-w

This article is cited by

-

Riboflavin-PLGA nanoparticles enhance the effectiveness of the pyruvate carboxylase inhibitor ZY-444 in targeting lipogenesis in colon and breast cancer

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

FOXA2 sensitizes endometrial carcinoma to progestin-mediated conservative therapy by triggering PR transcriptional activation

Oncogene (2025)

-

Physiological and transcriptomic analyses reveal temperature-dependent regulation of stress response, protein synthesis and metabolic reprogramming in juvenile mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi) under simulated transport

Fish Physiology and Biochemistry (2025)