Abstract

Integrated transport hubs require reliable, fine-grained forecasts of crowd distribution to safeguard operations and sustainable urban mobility. We present Group Evolution Mechanism Embedded Network (GEME-Net), a passenger flow distribution forecasting architecture that fuses multimodal data, including video-derived counts, digital twin-based mobility chains, and railway/metro operations information, via multi-graph spatial representations and event-aware temporal modules, with a distilled lightweight student model for deployment. In a real-world case at Shanghai Hongqiao, GEME-Net consistently outperforms statistical, convolutional, recurrent, graph-based and Transformer baselines across MAE, RMSE and WMAPE, while retaining inference latency compatible with near-real-time use. Ablations indicate that schedule encoding and event-driven frequency enhancement, together with learned long-range and community graphs, are principal contributors to accuracy. By coupling operational signals with spatial semantics, our approach improves hub-scale situation awareness and short-horizon decision support, offering a practical route to resilient crowd management without asserting broader societal or policy impacts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amid the intensifying global warming and environmental pollution, the pursuit of sustainable transportation solutions has become an urgent priority. Multimodal public transportation systems, integrating buses, subways, railways and other modes, offer a viable path for reducing carbon emissions, alleviating urban congestion and promoting sustainable urban development1. Compared with traditional single-mode systems, multimodal transport significantly enhances travel efficiency2, reduces environmental burdens3, and plays a vital role in addressing climate change and advancing sustainability. Integrated transport hubs serve as the core nodes of multimodal transportation networks. These hubs connect various transport modes within and between urban regions, ensuring the seamless daily mobility of residents and travelers4. As crucial anchors of urban transport systems, they greatly facilitate commuter, tourist, and business travel by optimizing transfer experiences and improving service accessibility5, thereby encouraging greater public transit utilization.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, an integrated transport hub is defined as a comprehensive infrastructure connecting multiple transport services, typically encompassing railway, metro, bus, and airport nodes. By providing a unified platform for intermodal connectivity, such hubs enable efficient and convenient transfers for daily travelers. However, the operation of these hubs faces several significant challenges:

-

(1)

Crowd and safety: With the convergence of multiple transport modes, integrated transport hubs are often required to handle enormous volumes of passenger traffic. During peak hours, concentrated inflows may lead to severe crowding, exceeding the hub’s designed capacity and posing serious challenges to operational efficiency and passenger safety.

-

(2)

Complex passenger composition and spatiotemporal distribution. Passenger flows within hubs are composed of heterogeneous groups, including commuters, tourists, and business travelers. At the same time, hubs typically integrate a variety of non-transportation services, such as retail, dining, and leisure facilities, leading to increased heterogeneity in passengers’ spatial travel behavior. The overlap of different travel purposes and transportation modes results in complex passenger flow generation patterns and spatial-temporal distributions. This diversity increases the difficulty of accurate prediction and real-time management, presenting significant operational challenges.

-

(3)

There is no clear quantitative method yet for assessing the impact of public transport operations on passenger flow fluctuations. Despite the heterogeneity of travel within a given space, passenger behavior within a hub is still largely constrained by the operational dynamics of public transport as departure time approaches. Therefore, it is necessary to propose expressions that can quantify regional passenger flow fluctuations and multi-modal transport operational dynamics. Effectively modeling and accurately predicting these evolving patterns remain major technical and practical challenges.

To address the aforementioned challenges, it is essential to gain a deeper understanding of individual passenger behaviors within the hub’s spatial environment. At the same time, integrating multimodal data, such as multi-angle surveillance video within the infrastructure, ticketing records, and public transportation operational data, enables the construction of more accurate passenger flow prediction models. Given the need for real-time demand forecasting in order to optimize hub operations, it is also crucial to develop lightweight predictive models that can deliver fast and reliable forecasts at low computational cost, thereby supporting dynamic and responsive management.

Passenger flow forecasting, as a classic time-series prediction problem, can generally be categorized into traditional statistical methods and machine learning-based approaches. Early studies often relied on parametric models, such as Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) models6,7,8 and historical average models (HA)9. However, these methods face substantial limitations when dealing with the complex and nonlinear dynamics of passenger flows, restricting their applicability in real-world scenarios10. During the same period, some researchers turned to computer-based simulation approaches. These include macroscopic dynamic models11,12 and microscopic individual-based behavioral models13,14,15, which simulate the dynamic evolution of crowds over time by scheduling agents’ movements within virtual environments. While such simulations help capture basic structural patterns of flow and provide short-term demand estimations, they face challenges similar to those of parametric models. Essentially, simulation methods rely on parameterized assumptions about individual passenger behavior16 or macroscopic flow dynamics. As a result, they struggle to accurately reflect the complex relationships between traveler movement, spatial layout of facilities, and external events in transport hubs, often leading to significant discrepancies between predicted and actual flow patterns.

The application of machine learning has introduced new perspectives to the task of accurate passenger flow forecasting. Algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM)17,18, k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)19,20, and Kalman Filtering21 have been employed to predict passenger volumes, achieving improvements in forecasting accuracy. However, these models are limited in their ability to capture spatial features and long-term temporal dependencies inherent in time-series data, making them unsuitable for simultaneous forecasting across multiple spatial regions. Emerging deep learning techniques have become powerful tools for improving forecasting performance. In 2015, the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network was first introduced into the field of traffic flow prediction22. Since then, a wide range of deep learning models based on architectures such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)23,24, Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)25,26, and LSTM27,28 have been proposed for passenger flow forecasting. Subsequent research recognized that regions within a transport network are not independent entities. Accordingly, many studies incorporated traffic network topologies into their model inputs and employed graph-based neural network modules, such as Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)29,30, Graph Attention Networks (GAT)31,32, and Graph Transformer models33 to jointly model temporal and spatial dependencies, thereby further enhancing predictive accuracy. However, several limitations remain in current research on passenger flow distribution forecasting in transport hubs. First, most existing models focus on coarse-grained metrics such as total inflow and outflow volumes at stations34,35,36, with limited attention paid to how the intra-station spatial distribution of flows affects overall operational efficiency. Second, although spatial information has been widely incorporated into predictive models, the modeling of spatial networks is often based solely on the physical layout of the facility37,38 or pre-defined activity routes39. This approach neglects the spatiotemporal correlations between non-adjacent areas and fails to account for actual passenger behavioral patterns, limiting the model’s ability to capture the complex, dynamic relationships across functional areas within the hub. Considering external factors influencing passenger flow fluctuations is also indispensable. Although existing prediction models incorporate and quantify the impact of weather27, social media10, and other information on passenger flows, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy, they lack deep exploration and quantification of external data, such as transportation operational information, which undoubtedly drives individual passenger travel behaviors. Consequently, these models have not yet established a modeling framework that captures the association mechanisms between passenger flow fluctuations and public transportation operational information.

In recent years, the introduction of the Transformer architecture40 has brought a new paradigm to the design of passenger flow forecasting models. By leveraging multi-head attention mechanisms, Transformer networks are capable of adaptively capturing multi-scale temporal dependencies in time-series data while simultaneously modeling spatial–temporal correlations. These capabilities have established Transformer-based models as the state-of-the-art in the forecasting domain. Transformer-based approaches41,42 have effectively addressed key limitations of traditional deep learning models, such as the difficulty in integrating spatial and temporal features and modeling long sequences. Specifically, the global self-attention mechanism at the core of Transformers inevitably incurs substantial computational overhead, which limits their suitability for real-time applications where fast inference is essential. As predictive models are increasingly expanded and deployed in real-time public transportation systems, keeping a balance between model complexity and predictive performance remains a critical challenge.

Building upon the limitations identified in existing studies, we position our work as a methodological and empirical contribution to hub-scale passenger flow forecasting. First, we design a regression-informed Train-Schedule Effect Encoding and an Event-Driven Frequency-Enhanced Module (TSEE and EDFEM) that translates timetable-driven influence into sparse attention masks and frequency-enhanced features, improving the predictive model’s responsiveness and learning capacity regarding the short-term impact of event-induced volatility. Second, utilizing mobility chain data from VR behavioral experiments as input, we propose a graph construction strategy driven by topological features. This approach generates three spatial correlation graphs, integrating diverse spatial association patterns derived from the mobility network’s topological structure. This enables a fine-grained representation of the non-local correlations and evolution mechanisms underlying spatial passenger flows. Third, leveraging the fusion of operational data of the integrated transportation hub and spatial correlation graphs constructed above, we propose a robust and generalizable passenger flow distribution forecasting model, named Group Evolution Mechanism Embedded Network (GEME-Net). The model accounts for multiple dimensions of external factors—including passenger behavior, facility layout, and operational events—and embeds spatial-temporal features to enhance its adaptability to heterogeneous passenger groups and diverse spatial settings. GEME-Net addresses the shortcomings of traditional approaches in accurately predicting passenger dynamics under complex and variable conditions.

In terms of practical value for improving the operational efficiency of public transportation and enhancing passenger travel experience, our research offers several key contributions. Specifically, we employ knowledge distillation techniques to transfer knowledge from a complex deep learning model (teacher model) to a lightweight model (student model). This approach reduces computational costs while maintaining stable and reliable predictive performance. As a result, the distilled model could meet the practical requirements of real-time management and dynamic control in integrated transport hubs, where high efficiency and fast inference are essential for responsive operational decision-making.

Methods

Data sources

For empirical validation of our prediction framework, this study selects the Hongqiao Station located in Minhang District, Shanghai, China, as the case study site. The Shanghai Hongqiao Integrated Transport Hub spans a total area of over 1.3 million square meters, with the main waiting hall covering ~11,340 square meters and capable of accommodating up to 10,000 passengers simultaneously. The hub is seamlessly connected to Shanghai Hongqiao International Airport, as well as Shanghai Metro Lines 2, 10, and 17, and the city’s road transportation network. The floor plan and functional area of Hongqiao Station’s layout scheme are illustrated in Fig. 2.

The multimodal input data used in this study consist of three main branches: (1) time-series data of passenger flow distributions, (2) passenger mobility chain datasets, and (3) public transport operational information linked to railway infrastructure.

These datasets are sourced respectively from: (1) monitoring video data distributed throughout the hub infrastructure; (2) behavioral experiments conducted within a digital twin representation of the hub; (3) the Electronic Ticketing Management System (ETM).

First, monitoring video data was extracted from the station monitoring system for August 10, 2024, covering the period from 7:00 to 20:00, the operational hours during which the infrastructure is open to passengers. The video data were collected from 18 predefined areas located across the waiting hall level and the commercial level. To process this data, we developed an Automated Passenger Counting (APC) system. The system segments input surveillance videos from each zone into 10-second intervals, and then utilizes the Baidu AI Platform’s automatic passenger counting API (https://ai.baidu.com/tech/body/num) to detect and count individuals within predefined spatial regions. Finally, time-aligned passenger counts from all zones are aggregated to generate the spatiotemporal passenger flow distribution dataset \({X}_{N,{T}_{h}}^{p}\) used in this study.

where \({X}_{N,{T}_{h}}^{p}\in {R}^{{T}_{h}\times N}\) represents the collection of passenger flow data for \(N\) functional areas over \({T}_{h}\) historical time steps. \({x}_{N,t}^{p}\) represent the passenger flow data for area \(N\) at time \(t\).

Second, to capture the complete mobility chains of passengers within the hub space, we constructed a high-fidelity digital replica of Shanghai Hongqiao Station, including all vertical levels and the connecting corridors to metro station exits and the airport transfer passages. Behavioral experiments conducted within digital representations of public spaces have been proven effective in studying pedestrian wayfinding strategies43. The digital environment was developed following a three-layer framework: Physical Layer → Input/Output Layer → Digital Layer, as illustrated in the “Digital Scenario Layer” module of Fig. 3.

In October 2024, we recruited 60 graduate students (35 male, 25 female; aged 21–30, average age 24.3) to take part in a behavioral experiment based on the digital environment. Prior to the experiment, each participant completed a questionnaire that collected demographic information (e.g., gender, age, previous railway travel experience) and habitual behaviors (e.g., whether they typically collect tickets or shop during waiting periods). Participants who reported such non-mandatory behaviors were assigned optional task nodes (e.g., ticketing, shopping) in the digital scenario, allowing their behavior in the virtual environment to realistically reflect their real-world travel habits. In the main experiment, each participant was asked to complete six independent wayfinding tasks. At the beginning of each task, the system randomly assigned an entry gate and a target boarding gate corresponding to a specific train, simulating realistic multimodal transfer scenarios. Each trial ended once the participant reached the assigned boarding gate.

During the experiment, participants’ movements were recorded at a frequency of 1 second, resulting in a total of 420 valid trajectory sequences.

We treated the transfer counts between regional pairs as count variables and examined their distributional characteristics to estimate the minimum sample size required for the study. The overall transfer frequency histogram (Fig. 4) shows a pronounced right-skewed distribution. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (statistic = 0.457, p < 0.001) rejected the Poisson distribution. We therefore compared Poisson, mixed Poisson, and negative binomial models, using the minimum AIC criterion for model selection, and found that the negative binomial model (AIC = 1626.6) provided a significantly better fit. Accordingly, the negative binomial distribution was adopted to characterize the transfer counts. This result confirms the heavy-tailed property, where a small number of high-frequency transfers dominate the overall transfer pattern. Based on this, we assumed that the typical transfer probability corresponds to the contribution ratio of highly correlated regional pairs and used the top 10% of high-transfer pairs as the estimation benchmark. The theoretical minimum sample size was then calculated using the standard single-population proportion formula44 \(\bar{n}={Z}_{\alpha /2}^{2}\cdot p\cdot (1-p)/{E}^{2}\), with a 95% confidence level (\({Z}_{\alpha /2}=1.96\)) and an error margin E = ± 5%. The resulting minimum sample size was 322, indicating that the 420 activity-chain records obtained from behavioral experiments in this study meet the required threshold.

Each trajectory sequence contains the 3D spatial coordinates and corresponding timestamps t’ of a participant i’s position \({p}_{i}({t}^{{\prime} })=\{{x}_{i}({t}^{{\prime} }),{y}_{i}({t}^{{\prime} }),{z}_{i}({t}^{{\prime} })\}\) in the digital environment. Subsequently, we applied a region-matching function \({\delta }_{m}^{i,n}\) to identify and record the sequence and timing t’ of area n’s entries during each participant’s activity. These entries were mapped to a predefined set of bounded spatial regions \({R}_{m}^{n},{{\rm{ {\mathcal R} }}}_{m}\{{R}_{m}^{n}|k=1,2,\ldots ,{A}_{m}\},{{\rm{ {\mathcal R} }}}_{m}\), denoted as a collection of functional zones within the station, each defined by a number of \({A}_{m}\) known set of vertex coordinates in the facility layout.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, each participant’s activity sequence was encoded based on the order in which they entered functional areas, starting from their initial entry into the station environment. By sequentially labeling the identified regions according to the first time of entry, we constructed a set of mobility chains \({{\rm{ {\mathcal L} }}}_{T}\) that represent the ordered spatial trajectories of passengers within the hub.

The public transportation operational data used in this study include: (1) railway timetables connected to the hub, (2) urban rail transit (URT) timetables, and (3) ticketing records extracted from the Railway ETM during the study period. All three datasets were resampled to align with the temporal resolution of the passenger flow data, enabling seamless integration into the forecasting model.

Exploratory characterization of Hongqiao hub’s mobility network

To study the topological characteristics of passenger collective mobility networks from a macroscopic perspective, this research integrates the set of mobility chains obtained from prior behavioral experiments in a digitalized hub scenario. We transform the mobility chains into a directed weighted mobility network, where the weight on edge i to j equals the number of times region j follows i in the sequences. The average clustering coefficient and the average shortest path length are calculated as key indicators to characterize the network’s “small-world” properties, aiming to explore the spatial aggregation of regions induced by collective passenger activities. A randomized reference network is constructed as a baseline for comparison, and based on the small-world model proposed by Watts and Strogatz45, the overall small-world characteristics of the mobility network are quantitatively evaluated. The results show that the network’s average clustering coefficient (for each node in the network, the ratio of the actual number of connections between neighboring nodes to the possible number of connections) is \(C=0.63\), and short average path length is \(L=2.58\) (which is a topological distance considering one unit for each edge connecting two nodes), the global small world coefficient (the clustering degree and average shortest path length of the network are compared to the corresponding values in the random graph of the same size. The larger the value, the stronger the small-world property of the network is \({\sigma }_{g}=1.88\), yielding a high global small-world coefficient. This indicates that the network exhibits significant small-world properties, with strong local clustering among functional areas. Furthermore, for the undirected version of the activity network, node-level metrics including degree centrality, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality are calculated. The top 10 functional areas ranked by degree centrality are listed in Table 1. Among them are areas 8, 10, 11, 15, and 20, which include waiting areas and commercial zones near metro transfer corridors, exhibiting high centrality and playing crucial roles in both connectivity and mediating flows across the network. These areas are thus key to hub operations and passenger flow guidance.

The study further applies the Greedy Modularity Algorithm46 for community detection within the activity network. The algorithm first treats each node as an individual community. Then repeatedly selects the pair of nodes whose merger maximally increases the network’s modularity and immediately merges them into the same community. Each identified community subnetwork is then analyzed separately for small-world characteristics, enabling the identification of localized small-world structures. As shown in Fig. 6, the visualization of highly cohesive subnetworks reveals a clear pattern of “transport mode homogeneity” in community divisions. That is, nodes representing functional areas within the same community (indicated by the same color) tend to serve passengers arriving via the same mode of transportation. As observed in Table 2, areas within a single community, such as ticketing zones and commercial areas near metro transfer corridors—form subnetworks with high transition probabilities and significantly higher internal edge densities compared to inter-community connections. This structural pattern unveils the functional stratification of station interior space, where passengers associated with different transport modes self-organize into topologically distinct subsystems within the network.

This process, at the macroscopic level, reveals that the mobility network of passengers arriving via multi-modal transportation within the hub exhibits a significant spatial clustering effect. Simultaneously, at the microscopic level, it provides deeper insights into the spatial interaction characteristics among specific functional areas within the hub.

Causal association between operational information and flow fluctuations

To verify and quantify the strength of correlation between passenger flow fluctuations within different functional areas and the occurrence of public transportation operational events, this study employs Granger causality tests47 to assess the statistical significance of the relationship between operational events and regional passenger flow dynamics. Furthermore, a multiple linear regression model is constructed to establish causal regression relationships. By recording the occurrence of operational events at time step \(t\), the regression coefficients are used to capture the direct contribution of each event type to passenger volume changes in each area. These coefficients serve as indicators of the causal association strength between operational events and passenger flow variations.

where, \(\beta ,\gamma\) denote the regression coefficient measuring the direct contribution of an operational event (railway train departure \({E}_{t}\), metro train arrival \({U}_{t}\)) to passenger volume in a given area, and \({\varepsilon }_{n,t}\) represent the random error term. If \({\beta }_{e,d,n} > 0\)(when the coefficient is less than 0, it is uniformly treated as 0), the operational event is considered to have a Granger causal relationship with passenger flow in area \(n\), indicating that the event can statistically explain future fluctuations in that area’s flow. Additionally, \(C{V}_{n,t-d}\,=\frac{{\sigma }_{s}({X}_{n,t-d:t}^{p})}{{\mu }_{s}({X}_{n,t-d:t}^{p})+\varepsilon }\) denotes the coefficient of variation of passenger volume in area \(n\), calculated over a fixed lag window of length \(l\). It is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation \({\sigma }_{s}\) to the mean \({\mu }_{s}\) within the window and is used to capture local fluctuation characteristics of passenger flow in the area.

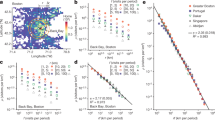

The results indicate that the average regression coefficient of railway train departure events on station-wide passenger flow fluctuations is 62.5% higher than that of metro train arrival events. As shown in Fig. 6a, b, railway departures exert a stronger and more sustained impact on passenger flow variations in different areas of the station compared to metro arrivals. The scatter plot in Fig. 6c further demonstrates that the causal strength remains positively correlated with network distance, suggesting that the influence of railway departures extends broadly across spatial regions. Furthermore, as the departure time approaches, the further away from the ticket gate, the greater the intensity of passenger flow fluctuations. In contrast, the association map for metro arrivals (Fig. 6d) shows no significant trend, indicating that their impact is highly localized. We attribute this phenomenon to the differences in the spatiotemporal propagation patterns between the two types of operational events:

Railway train departures and metro arrivals differ markedly in the intensity, synchronization, and spatial propagation of passenger flow shocks within integrated transport hubs. Railway departures trigger high-intensity shocks strongly synchronized with collective passenger behaviors, manifesting as densely clustered crowds near waiting halls and ticket gates as departure times approach, with single-event inflows ranging from 102 to 10³ passengers. These intense and synchronized flows generate chain-like fluctuations propagating widely along highly coupled pathways identified through small-world network analysis, often reaching distant, functionally distinct areas such as commercial and dining zones. In contrast, metro arrivals occur more frequently but involve smaller passenger volumes (typically between 101 to 102) and induce rapid passenger dispersal due to varied individual travel routes. Consequently, their impacts remain spatially localized within subnetworks such as concourses and transfer corridors, without significant long-range interactions, consistent with the small-world functional network’s characteristic of forming spatially distinct communities with limited inter-community coupling.

To further verify the relationship between the strength of regional passenger flow fluctuations and the distance from the event occurrence area, defined as the metro exit or the ticket gate associated with the departing railway train at the current time, we conducted correlation tests (Pearson test) and linear fitting based on the scatter plots in Fig. 7c, d. The results reveal a significant positive correlation between passenger flow fluctuations and railway train departure events, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.8395 and a high goodness-of-fit in the linear regression (\(p=0.0059 < 0.05\), \({R}^{2}=0.9405\)). This indicates that the impact of railway departures on the intensity of regional passenger flow fluctuations increases with increasing spatial distance. In contrast, for metro train arrival events, the correlation between passenger flow fluctuations and distance is not statistically significant (\(p=0.33411 > 0.05\)), and the linear regression exhibits a low goodness-of-fit (\({R}^{2}=0.4892\)). This supports the conclusion that metro-induced flow variations are localized and do not exhibit a clear spatial decay pattern. Table 3 summarizes the linear regression results for both event types.

a shows the railway departure event, and b shows the metro train arrival event. Scatterplot of correlation strength of passenger flow fluctuations versus network distance from the event area. c, d show the distance and strength of association of the region with railway train ticket gates and metro exit lanes, respectively. Distance and correlation data are normalized separately in order to keep the indicators on the same scale.

Optimization strategies for passenger flow forecasting modeling

Based on the previous analysis, we propose two modeling optimizations for passenger flow prediction: graph construction and transit event encoding. Previous studies have shown that considering multiple spatial dependencies in passenger flow prediction tasks can help improve prediction accuracy10. Consequently, we constructed three types of spatial correlation graphs, namely the collective activity long-range correlation graph \({G}_{c}\), the regional spatial clustering correlation graph \({G}_{r}\) and the activity intensity correlation graph \({G}_{a}\). These graphs are used to model the long-range coupling characteristics between regions in the activity network (the passenger-activity network’s average clustering coefficient is markedly higher than that of a random graph of the same size, while its average shortest-path length is comparable to the random baseline. As a result, functional zones that appear far apart can typically be reached through only two or three transfers, forming cross-area “long-range coupling” shortcuts), the strong correlation between passenger flows in adjacent regions within a community (community testing results reveal the spatial activity homogeneity of passengers traveling by the same mode of transport, indicating a high degree of correlation between passenger flow dynamics between adjacent nodes within the same community), and the similarity in passenger flow fluctuations between non-adjacent regions with similar service functions (within each community, the nodes generally include a mix of functional areas such as ticketing zones, commercial areas, and waiting halls, rather than clusters of homogeneous functions. This reflects a high degree of similarity in the spatiotemporal utilization of hub resources, leading to similar intensities of passenger activity over time).

For the construction of graph \({G}_{c}\), we propose a Temporal-Aware Skip-Gram semantic model, which extends the traditional Skip-Gram48 by introducing a direction-sensitive, dynamic sampling window. This allows the model to capture unidirectional transitions and temporal constraints in passenger movements within the hub via learning semantic associations derived from passenger mobility chains. By inputting the set of passenger mobility chains \({{\rm{ {\mathcal L} }}}_{T}\), edges are constructed between nodes with high co-occurrence frequency, enabling the model to learn functional semantic associations and long-distance spatial dependencies beyond the physical topology. The size of the dynamic window is jointly determined by a base size (to prevent overfitting from an overly small window) and a function modulated by a distance-sensitivity coefficient.

where \({w}_{t}({v}_{r,c})\) indicates the sliding window size with \({v}_{r,c}\) as the target node. \({w}_{base}\) denotes the base window size(set its value to the average length of the mobility chain), \({\min }_{j > c}{D}_{c,j}\) is the minimum Euclidean distance between the target node \({v}_{r,c}\) and a future node \({v}_{r,j},j > c\) (appearing after central node \({v}_{r,c},c < m\), r is the mobility chain number) in the mobility chain, and \({\eta }_{T}\) is the distance sensitivity coefficient expressed as an exponential function. By treating the future node within the sliding window as the context node, the model samples temporal co-occurrence relationships between the target node and context nodes. Only future nodes are sampled to respect directionality. To achieve this goal, the \({d}_{v}\) dimensional feature vector for each node’s spatial characteristics is learned by minimizing the negative log-likelihood loss \({{\rm{L}}}_{SG}\) between the target node and context node. Finally, the cosine similarity between these feature vectors is used to quantify the spatial correlation between areas.

In constructing \({G}_{r}\), the study employs PageRank centrality49 and Dijkstra-based distance decay to reconstruct the influence range of physically neighboring functional areas in the mobility network. This approach can identify node pairs that are both physically close and have strong flow interaction, leading to the construction of the regional spatial clustering correlation graph \({G}_{r}\).

where \(P{R}_{i}\) represents the PageRank score of node i. The computational process can be described as a damped random walk on a directed graph, where each step involves a uniform transition along outgoing edges with a certain probability, and a random jump to any node with the remaining probability. The steady-state visitation probability at each node ultimately constitutes its PageRank score. \({k}_{d}(j)\) denotes the degree of node j. \({D}_{ij}\) is the shortest route length calculated by Dijkstra’s algorithm between nodes i and j. Our objective is to assign greater weight to links connecting nodes with higher PageRank (those connected to more nodes) and their neighboring nodes (those with shorter distances), thereby emphasizing high-throughput neighboring pairings. The edge set (binary variable) \({E}_{r}\) is constructed based on the actual physical topology. We consider area i and j to be topologically directly connected if there is no need to reach region j from area i through other areas.

Graph \({G}_{a}\) is constructed based on two key temporal features of each node, stepwise rate of passenger flow change (the first-order difference of passenger flow between successive time steps) and global trend of variation. These are derived from the original passenger flow time series for each region. A moving average filter50 is applied to extract trend components, and a high-pass filter is used to isolate high-frequency fluctuations. To eliminate sequence-similarity errors caused by phase shifts arising from sequence fluctuations, thereby accommodating passenger-flow sequences from different regions that share the same shape but are time-misaligned, the dynamic time warping (DTW) algorithm51 is employed to compute the combined similarity (weighted sum of similarity between two trends across areas) between areas. The similarity is then used to assign edge weights between nodes in \({G}_{a}\).

To explicitly embed the impact of public transportation operational events into the passenger flow prediction model, this study designs an Event-Driven Spatio-Temporal Focus Module (EDSFM) including Train-Schedule Effect Encoding (TSEE) and Event Driven Sparse Attention. Based on previously estimated multivariate regression coefficients quantifying the influence of operational events on regional flow fluctuations, TSEE models the shock effects of both railway and urban transit (metro) train arrivals/departures as well as railway ticketing information. This module enables the model to incorporate the dynamic impact of operational schedules on passenger flow variations across functional areas.

where \({\alpha }_{e},e\in \{1,2\}\) denotes the influence weights of two types of events on different areas. \({E}_{t}\) for the number of railway train departures and \({U}_{t}\) for the number of urban rail arrivals (discrete variable). These weights are the mean values of the full-period regression coefficients obtained by Granger causal analysis for the corresponding events in the nth area. \(\bar{P}\) represents the average number of tickets sold per train on a given day, used for normalization. \({\tau }_{e},e\in \{1,2\}\) is the duration of the event’s influence, these values are set as 30 minutes and 15 minutes according to empirical observations of transit operations. \({t}^{{\prime} }\) is the timestamp of the event, and \({d}_{n}\) denotes the topological distance between area \(n\) and the event location. An exponential decay term is introduced in the formula to model the temporal attenuation of the event’s impact.

Forecasting problem definition

We define the passenger flow prediction problem addressed in this study before introducing the prediction architecture. The task can be stated as follows: given the passenger flow matrix \({X}_{N,{T}_{h}}^{p}\in {R}^{{T}_{h}\times N}\) over \({T}_{h}\) historical periods, the multi-type spatial association graphs \({\mathscr{G}}\) including \({G}_{c},{G}_{r}\) and \({G}_{a}\) the public transportation operation data \(P{T}^{{T}_{h}\times 3}\), the goal is to learn a mapping function \(f(\cdot )\) to predict the passenger flow vector \({X}_{N,{T}_{h}+tf}^{p}\) in each area for the future time period \(tf\).

Re-parameterized convolution embedding

The architecture of the proposed GEME-Net is illustrated in Fig. 8, adopting an encoder-decoder framework composed of multiple sub-layers. At the initial stage, a re-parameterized convolutional embedding layer52 is applied to transform the raw temporal passenger flow data from multiple regions into dense vector representations. This step captures fine-grained temporal fluctuations and spatiotemporal dependencies, serving as the input features to the encoder. During the re-parameterized convolutional embedding process, the passenger flow distribution data \({X}_{N,{T}_{h}}^{p}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{T}_{h}\times N}\) is mapped into a 3D tensor \({X}^{{\prime} }\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{1\times {T}_{h}\times N}\) and the original convolutional kernel weights \({W}_{rc}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{C}_{out}\times {C}_{in}/{g}_{r}\times {k}_{rc}\times {k}_{rc}}\) are initialized as an all-zero tensor. Here, \({C}_{in}\) and \({C}_{out}\) denote the number of input and output channels, \({g}_{r}\) is the number of groups, and \({k}_{rc}\) is the kernel size. These weights are learned via gradient updates during training. Next, kernel domain unfolding is applied: the convolutional kernels are flattened into 2D local convolutional feature maps \({W}_{rc}^{flatten}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{1\times {N}_{k}\times {k}_{rc}\times {k}_{rc}},{N}_{k}={C}_{out}\cdot {C}_{in}\) for each spatial group. A kernel-space convolution \({k}_{m}\times {k}_{m}\) is then performed over these maps to learn intra-kernel structures in Eq. (10). To reduce noise and improve stability, depthwise separable convolution is used, enabling adaptive smoothing of the raw weights while reducing \(O(N\cdot {k}_{rc})\) computational complexity. In the weight reassembly stage, the original kernel \({W}_{rc}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{C}_{out}\times {C}_{in}\times {k}_{rc}\times {k}_{rc}}\) is fused with the learned structural kernel \({\hat{W}}_{rc}\) via element-wise addition to produce the final kernel \({W}_{rc}^{final}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{C}_{out}\times ({C}_{in}/{g}_{r})\times {k}_{rc}\times {k}_{rc}}\) in Eq. (11). This final kernel is then used in standard convolution to extract temporal dynamic features from the input, as shown in in Eq. (12).

where \({\theta }_{rc}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{({C}_{out}\cdot {C}_{in})\times 1\times {k}_{rc}\times {k}_{rc}}\) denotes the kernel-space mapping weights. The original input \({X}_{N,{T}_{h}}^{p}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{T}_{h}\times N\times 1}\) is ultimately embedded into a high-order spatial representation \({Z}_{rc}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{C}_{out}\times {T}_{h}\times N}\). This efficient re-parameterized convolution process reduces parameter overhead while enhancing the model’s ability to decouple multi-scale temporal features, thereby providing a robust foundational representation for the subsequent encoder’s feature learning.

The overall framework adopts an encoder-decoder architecture, where both the encoder and the decoder consist of multiple identical sub-layers. The figure illustrates the structure of a single submodule within the encoder and decoder, while the ellipsis “…” indicates the sequential stacking of multiple identical modules.

Encoder

The encoder consists of a projection layer, composed of a causal temporal convolution and a linear transformation, followed by stacked residual-connected encoder layers. Each encoder layer integrates four core components: the Multi-Scale Retention Rate Attention module explicitly models temporal dependencies across multiple time scales, focusing on local patterns while suppressing noise from distant time steps; the Event-Driven Frequency-Enhanced Module emphasizes learning from specific passenger flow frequency fluctuations induced by public transportation events, enhancing the model’s responsiveness to short-term event-driven changes; the Spatial-Temporal Adaptive Multi-Graph Convolution Network (ST-AMGCN) dynamically constructs adaptive adjacency matrices to capture complex and evolving spatial dependencies, enabling flexible spatiotemporal representation; and the Cross-Modal Self-Attention (CMSA) module performs deep alignment and cross-attention between spatial and multi-scale temporal features, facilitating efficient integration of multimodal information. The outputs from all modules are fused through CMSA and passed through a fully connected layer to generate the encoder’s final output, which is then fed into the decoder.

Event‑driven frequency‑enhanced module

The Event-Driven Frequency-Enhanced Module consists of two sequential submodules: Event-Aware MOE-Decomposition (EA-MOE) and Event-Driven Frequency-Enhanced Attention (ED-FEA). EA-MOE performs explicit temporal decomposition, stabilizing trend extraction and mitigating overfitting caused by abrupt event-induced fluctuations. ED-FEA then employs spectral gating masks to enhance periodic signals associated with transit events, enabling downstream attention mechanisms to focus directly on short-term, high-amplitude variations driven by those events. EA-MOE takes as input the historical passenger flow data \({X}_{N,{T}_{h}}^{p}\in {R}^{{T}_{h}\times N}\) and public transit event data \(PT\) on the same time scale. A multi-scale sliding average pooling is applied along the temporal axis to extract trend features \({T}_{E}^{(m)}\) at different scales, producing five expert-specific trend representations in Eq. (13). Simultaneously, \(PT\) is embedded via a fully connected layer into a low-dimensional event feature vector, which is then processed by another fully connected layer to generate gating weights for each expert in Eqs. (14) and (15). These weights are used to fuse expert trends into a unified, event-aware trend representation in Eq. (16). This is then concatenated with the original input \({X}^{{\prime} }\) and passed through a \(1\times 1\) convolution to integrate features. Finally, a residual connection between the fused output and the original input is applied to produce the final output \({Y}_{EA}\) of the EA-MOE module, as shown in Eq. (17)

where \(m\) represents the sliding average indices at five time scales, used to capture smoothed trends over 5 min, 10 min, 20 min, 40 min, and 60 min intervals, thereby identifying event pulse patterns of varying widths. \({{\rm{K}}}_{e}\) denotes the expert averaging pool size, and \({M}_{e}\) is the number of experts, set to 5. \({W}_{1},{W}_{2}\) are learnable parameter matrix. \({s}_{e}\) is an intermediate variable \({z}_{e}\) generated by a fully connected layer from the event embedding, representing the initial weight scores for each expert. Through this process, the module explicitly separates routine trends from event-driven passenger flow fluctuations in the temporal domain.

ED-FEA further refines event-related periodic features. The feature \({Y}_{EA}\) is first flattened along temporal and spatial dimensions into a sequence \({X}_{flat}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{({T}_{h}\times N)\times {C}_{emb}}\), and each sequence is transformed via Real Fast Fourier Transform53 (RFFT) to obtain its frequency-domain representation \({X}_{f}\). In the frequency domain, the module computes the magnitude of each frequency component to capture underlying periodic patterns in passenger flow data. It then concatenates this frequency amplitude vector with the event embedding vector \({s}_{e}\) and feeds the result into a fully connected network to generate a frequency-band gating mask \({M}_{FEA}\). This mask dynamically controls which frequency components are amplified or suppressed, allowing the model to selectively enhance event-relevant frequencies while attenuating irrelevant ones. The enhanced frequency representation \({X}_{f}^{enh}\) is then transformed back into the time domain using inverse RFFT (IRFFT), yielding the event-enhanced spatiotemporal feature sequence \({\tilde{X}}_{f}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{({T}_{h}\times N)\times {C}_{emb}}\).

where \({\text{Re}}{X}_{f}\) and \({\text{Im}}{X}_{f}\) denote the real and imaginary parts of the complex frequency spectrum tensor \({X}_{f}\), respectively, with \({j}_{e}\) as the imaginary unit. Following frequency enhancement, the feature \({\tilde{X}}_{f}\) is projected into query \({Q}_{FEA}\), key \({K}_{FEA}\), and value \({V}_{FEA}\) representations for the multi-head self-attention mechanism.

where \({H}_{F}\) represents the number of attention heads, and \(\sqrt{{d}_{f}}=\frac{{C}_{emb}}{{H}_{F}}\) denotes the scaled dot-product. Through this attention mechanism, the model explicitly captures fine-grained spatiotemporal dependencies among event-enhanced passenger flow features. The output is then passed through a linear projection layer, resulting in the final module output \({Y}_{FEA}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{T}_{h}\times N\times {C}_{emb}}\).

Multi‑scale retention rate attention

Given that passenger flow data is a typical time series, its short-term fluctuations, such as peak periods or unexpected events, often exhibit strong local temporal correlations. While traditional linear projections in attention mechanisms can capture global patterns, they are limited in modeling localized temporal structures. In Multi-Scale Retention Rate Attention (MSR-Atte), instead of applying standard linear projections for generating the query \({Q}_{MSR}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{T}_{h}\times N\times {C}_{p}}\) and key \({K}_{MSR}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{T}_{h}\times N\times {C}_{p}}\) the model uses causal convolutional projections along the channel dimension with output size \({C}_{p}\). Using a fixed kernel size \({k}_{msr}\) causal convolution slides along the temporal axis to explicitly capture retentive correlations with the previous \({k}_{msr}-1\) time steps, while preserving temporal causality. Meanwhile, the value tensor is still derived via linear projection, retaining the global temporal feature information. This design ensures that, after computing attention weights, the mechanism integrates both short-term dependencies and long-term trends effectively.

where \({W}_{MSR,Q}^{({k}_{1})}\) and \({W}_{MSR,K}^{({k}_{1})}\) is the learnable parameter of temporal convolution kernel. \({Z}_{r}=\sigma (Con{v}^{(1\times 1)}([{Z}_{rc}||{Y}_{FEA}]))\) is the passenger flow matrix higher-order embedding tensor and frequency domain enhanced temporal features obtained after splicing by a one-dimensional point-by-point convolution operation. is the time convolution kernel parameter.

Inspired by the retention mechanism in RetNet54, we introduce a logarithmically spaced decay rate for each attention head \({h}_{m}\), controlling the retention strength of historical dependencies at different temporal scales. This design enables the model to simultaneously learn multi-scale temporal patterns ranging from minute-level to hour-level cycles within a single forward pass. Specifically, given the query \({Q}_{MSR}\) and key \({K}_{MSR}\) representations, MSR-Atte maps the feature dimension \({C}_{p}\) into \({H}_{MSR}\) multi-head subspaces. Each attention head is assigned a distinct temporal memory window, determined by a log-uniform partition of the time axis in the logarithmic domain, ensuring diversity in temporal focus. Finally, the outputs from all heads are concatenated to form a composite temporal representation, capturing multi-period temporal dependencies with fine-to-coarse semantic granularity. This process can be formulated as follows:

where \({u}_{{h}_{m}}\) is a normalization coefficient used to position the kth attention head within a linear interval, facilitating subsequent interpolation in the logarithmic domain to generate decay rates, thereby enabling the effective memory window of each head to expand geometrically. \((n,m)\) is the integer index along the sequence dimension. When \(n\ge m\), the query time is either after or exactly at the key time, ensuring attention values are retained and subjected to exponential decay to enforce strict temporal causality. \(\tilde{Q}\) and \(\tilde{K}\) represent the tensor forms of the original query and key, which help achieve smoother extrapolation over long sequences. These are element-wise multiplied (Hadamard product) with the decay matrix to compute decayed attention scores, which are then matrix-multiplied with the values \({V}_{MSR}\) to obtain the causal influence matrix across time steps within the respective scale window for each head. Finally, the outputs from all heads are concatenated to form the composite temporal semantic tensor \(M{H}_{MSR}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{C}_{p}\times {T}_{h}\times N}\), capturing multi-scale periodic temporal dependencies.

Spatial-temporal adaptive multi-graph convolution network

The study proposes a spatial-temporal adaptive multi-graph convolutional network (ST-AMGCN) to capture the complex, dynamic spatiotemporal relationships among passenger flows across multiple regions within a transport facility. The architecture is illustrated in Fig. 9. Unlike conventional adaptive graph convolution methods, ST-AMGCN integrates a temporal dynamic weighting module, where an LSTM encodes both the temporal embedding \({E}_{t}\) and recent historical passenger flow data to generate time-dependent weights \({\beta }_{t}\). This allows the model to adaptively adjust the spatial dependencies between nodes as time progresses. The input passenger flow matrix \({X}^{{\prime} }\) is first projected into an intermediate feature space via 2D convolution, producing \({A}_{{\bf{1}}},{A}_{2}\). These projected features are used to compute a learned dynamic adjacency matrix \({A}_{adapt}\). This matrix is modulated by the dynamic weight and a set of static adjacency matrices \({A}_{static}^{(i)}\in {M}_{subsets}=\{{A}_{static}^{(c)},{A}_{static}^{(r)},{A}_{static}^{(a)}\}\) derived from predefined spatial correlation graphs, resulting in the final dynamic spatiotemporal adjacency matrix \({A}_{st}\). This matrix is then element-wise combined with the node features (passenger flows) and passed through multi-layer graph convolutional operations. The outputs from different subgraphs are concatenated to produce \({X}_{out}\), capturing complex dynamic interactions and spatial dependencies among regions.

In the equation, the temporal embedding feature \({E}_{t}\) is obtained by embedding one-hot vectors of the original temporal attributes—specifically second-level (the finest statistical granularity), minute-level, and hour-level features via a linear layer. And \({h}_{t},{c}_{t}\) denote the encoding of sequence information at the current time step and the long-term memory unit, respectively. \({W}_{te},{b}_{te}\) are the learnable weight matrix and bias of the fully connected layer. \((i)\) represents the subgraph index, and \({S}^{l-1}\) denotes the input feature matrix for the \((l-1)\)th input. \({W}_{g}^{l-1}\) is the learnable parameter matrix of that layer.

Cross-modal self-attention

The spatio-temporal features obtained from preceding modules are fused in this component to fully exploit the complementary spatial and temporal information embedded in passenger flow data. As shown in Fig. 10, the architecture of this module is designed to efficiently integrate multi-modal information. Compared to existing cross-modal attention networks55, CMSA performs fusion on a shared spatial grid, integrating deep features from space \({X}_{G}\), time \({X}_{R}\), and position within a unified attention framework. This design allows parallel attention modeling strictly on the spatial plane, significantly reducing computational overhead. The CMSA_s submodule models cross-location spatial attention, explicitly capturing dynamic inter-regional dependencies. In parallel, CMSA_t focuses on temporal features extracted by MSR-Atte, learning interactions across different time scales. Finally, the module incorporates spatial position embeddings \({X}_{SP}\), and concatenates the outputs of CMSA_s and CMSA_t. A point-wise 1×1 convolution is applied to fuse spatial, temporal, and positional information, yielding the final cross-modal fused representation \({Y}_{CMSA}\).

Decoder

The decoder module is composed of multiple identical decoder layers stacked via residual connections, and concludes with two fully connected layers to generate short-term passenger flow forecasts for all regions. The decoder’s core function is to build upon the spatiotemporal features extracted by the encoder, further incorporating event-driven signals and spatiotemporal fluctuations of regional flows to establish causal relationships. These causal dependencies are used to generate attention masks, enabling a sparse attention mechanism that enhances the precision of flow prediction for target regions. A multi-head cross-attention mechanism then integrates the encoder’s spatiotemporal representations into the decoder. Unlike the Event-Driven Frequency-Enhanced Module, which embeds transit operations into the underlying frequency structure of the sequence via expert gating and band selection, the Event-Driven Spatial-Temporal Focusing Mechanism directly imposes event impact in the spatial domain. This mechanism modulates attention weights in the decoder based on causal influence, enabling local incremental adjustments to better capture region-specific flow variations.

In the decoder module, the event impact tensor \({I}_{t}\) calculated from formula (8), which quantifies the influence of events at each time step, is first passed through a linear projection to generate a normalized attention mask matrix \({\tilde{E}}_{{h}_{e}}\). Subsequently, a sparse attention mechanism is constructed, allowing the event-induced passenger flow response patterns to be explicitly injected into the spatiotemporal feature aggregation process.

where \({W}_{e},{b}_{e}\) denote the learnable weight matrix and bias vector, respectively. During the attention computation, when an element in the event-based mask \({\tilde{E}}_{{h}_{e}}\) approaches 0, the corresponding row \(i\) in the attention score matrix is assigned as \(-\infty\), effectively forcing its softmax output to approach zero, thereby preventing attention allocation. Additionally, for each token, a causal mask \({M}_{gc}(i,e),i=t\cdot N+n\) is used to determine whether the token’s associated region has any significant causal events. If not, the entire row in the attention matrix is masked, ensuring that no attention is distributed to non-event-related areas.

Next, the Multi-Head Attention mechanism adopts a standard multi-head self-attention structure, where the queries are derived from the output of the preceding Event-Driven Sparse Attention module, while the keys and values come from the encoder’s spatiotemporal representations. The high-dimensional features output from the stacked decoder layers are then flattened and passed through two fully connected layers, yielding the predicted passenger flow \({X}_{n,ts+tf}^{p}\) across \(N\) areas for the next \(tf\) time steps. During training, the model optimizes the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss, measuring the accuracy of short-term passenger flow distribution forecasts within the facility space.

Model knowledge distillation

Although GEME-Net, as the teacher model, achieves accurate predictions by integrating multiple modules to capture spatiotemporal passenger flow features and public transport operation events, it also introduces a large parameter scale and substantial computational overhead, which hinders low-latency deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. To address this, we adopt knowledge distillation by using the pre-trained GEME-Net as the teacher model to construct and train a student model with reduced complexity and latency, thereby lowering parameter size and computational cost while retaining as much predictive accuracy as possible.

The student model is implemented as a lightweight MLP, in which low-rank linear layers are combined with a shared bottleneck layer to capture the associations between key priors—such as event-driven dynamics and multi-scale temporal patterns—and passenger flow fluctuations distilled from the teacher model. Its training process and network architecture are illustrated in Fig. 11. Specifically, the historical passenger flow tensor \({X}_{N,{T}_{h}}^{p}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{T}_{h}\times N\times 1}\) is first flattened and normalized through a LayerNorm layer, and then embedded into a \({d}_{h}\) dimensional feature tensor \({W}_{S}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{({T}_{h}\times N)\times {d}_{h}}\) via two low-rank fully connected layers (first projected into a lower-dimensional intermediate space of size \({r}_{h1}\) and then mapped to a \({d}_{h}\) dimensional feature). The embedded features are subsequently passed through a shared-weight bottleneck layer, where the same set of low-rank linear weights is invoked twice. This design approximates the passenger flow features \({W}_{S}\) as a low-rank factorization \({U}_{S}{V}_{S},{U}_{S}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{({T}_{h}\times N)\times {r}_{h2}},{V}_{S}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{r}_{h2}\times {d}_{h}}\), reducing the parameter size from \({T}_{h}N{d}_{h}\) to \({T}_{h}N{r}_{h2}+{r}_{h2}{d}_{h}\), while the shared bottleneck further lowers computational complexity without sacrificing nonlinear expressiveness. The final features are projected through a linear layer to generate the student model’s multi-region passenger flow predictions \({y}_{S}\). During training, the student model is optimized against the teacher’s outputs \({y}_{T}={X}_{n,ts+tf}^{p}\) using a composite regression distillation loss (smooth L1 loss and cosine similarity loss) so as to align both the magnitude of passenger flows and the proportional distribution across regions with the teacher model, thereby updating the student parameters.

where \({\alpha }_{d}\) denotes the weighting coefficient of the two loss terms in the overall distillation loss, which is set to 0.5 in this study to balance their contributions to the final results.

Results

Model configurations and evaluation metrics

During the experiments, the dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio. The batch size was set to 16. All models were implemented using PyTorch 1.13.1, Tensorflow 2.6.0 and Python 3.8.0, and trained/evaluated on a GeForce RTX 3060 Ti GPU. The Adam optimizer was used, with a learning rate of 0.0001 for the teacher model and 0.001 for the student model. A regularization coefficient of 1 × 10−4 was applied to reduce overfitting. Model generalization was evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation, with 200 epochs per fold. The mean squared error (MSE) loss function was used for training. In terms of evaluation metrics, this study adopts a set of widely recognized indicators for assessing passenger flow prediction performance, including Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Weighted Mean Absolute Percentage Error (WMAPE). These metrics are used to comprehensively evaluate the model’s prediction accuracy and stability across different scenarios.

where \({\hat{y}}_{n,t}\) and \({y}_{n,t}\) denote the predicted and actual passenger flow values for area \(n\) at time step \(t\).

Since our model incorporates improved multi-head attention mechanisms to learn and fuse multimodal data within the hub, we evaluated the impact of the number of attention heads across different attention types on predictive performance, as shown in Fig. 12. The results indicate that the number of heads is a critical factor influencing both accuracy and complexity, with the largest effect observed for the sparse attention used to integrate public transport operation times. Event-driven frequency-enhanced attention in Fig. 12a. shows the next most pronounced effect, suggesting that modeling exogenous factors has a greater impact on capturing passenger flow fluctuations than further refining temporal autocorrelation learning. Moreover, the stronger variability in prediction metrics caused by sparse attention compared with event-driven frequency-enhanced attention demonstrates that hard-masked exogenous variable modeling is more effective than soft modulation via frequency gating. However, the drawback of hard coding lies in increased computational complexity, as illustrated in Fig. 12f. We also examined the effect of embedding dimension on prediction performance, where Fig. 12e shows that the best accuracy is achieved at a dimension of 32, which is therefore adopted throughout the experiments. The list of model hyperparameters is shown in Table 4.

a The effect of event-driven frequency-enhanced attention head counts. b The effect of multi-scale retention rate attention head counts. c The effect of sparse attention head counts. d The effect of multi head self attention head counts. e The effect of hidden dimensions in encoder. f Parameter scales of different types of attention mechanisms.

Comparison and analysis of prediction results

We next provide a detailed comparison of the prediction error metrics of the proposed model against those of established baseline models. In our experiments, we selected seven representative baseline models, including:

-

ARIMA: a statistical model widely used for time-series forecasting. In our experiments, the lag order, differencing order, and moving average order were set to 2, 1, and 1 respectively.

-

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM): This network consists of two hidden layers and one fully connected layer. Each hidden layer contains 128 neurons.

-

Convolutional LSTM (ConvLSTM): The prediction model consists of three hidden layers and one fully connected layer, with each layer containing 8 filters and performing convolution operations using 3×3 convolution kernels.

-

Convolutional Neural Network (2D CNN): Comprised of two convolutional layers and one fully connected layer, with 32 and 64 filters respectively and a kernel size of 3×3.

-

ST-ResNet56: A model that uses residual convolution to capture spatiotemporal features of passenger flow. In our experiments, we used only three residual convolution branches and omitted the original module for extracting weather features. Other network parameters remained consistent with the original paper.

-

Transformer40: The traditional Transformer model consists of three encoder and decoder layers. Each layer uses 8-head multi-head attention, and the feature embedding dimension is set to 64.

-

Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks (ST-GCN)57: A network that models spatiotemporal features of passenger flow using graph convolution and temporal gated causal convolution layers. Its structure comprises nine spatiotemporal convolutional units, using convolution kernels of size 3×3.

-

Informer41: An improved Transformer network with the same attention mechanism parameters and layer configuration as the standard Transformer.

To ensure a fair and reproducible comparison, all models share the same input, train/validation/test split and pre-processing pipeline (Z-score scaling fitted on the training dataset). Exogenous features are provided to architectures that can accept them (Graph input: ConvLSTM, ST-ResNet and ST-GCN, public transport operational information: Transformer and Informer. The self-attention in the baseline model was redesigned as a sparse attention module to ensure the incorporation of exogenous variables. While for univariate statistical baselines (ARIMA and LSTM), exogenous inputs are disabled by design, and we report multi-step recursive forecasts with an identical train process.

Table 5 presents the prediction accuracy comparison across all models. The results demonstrate that GEME-Net significantly outperforms all baseline models in terms of MAE, RMSE, and MAPE. Specifically, compared to the traditional time-series model LSTM, GEME-Net achieves improvements of over 12.6% (MAE), 9.1% (RMSE), and 19.45% (MAPE). When compared to the Transformer-based state-of-the-art model Informer, GEME-Net still yields performance gains of over 6.6%, 14.6%, and 14.4% improvement in the same metrics. When the time granularity of the passenger flow data increases from 10 s to 30 s, the performance gap between GEME-Net and the baseline models widens. Furthermore, the comparison between the teacher and student models indicates that, although the student model experiences a minor decrease in prediction accuracy, knowledge distillation enables a substantial compression of the model size, reducing the parameter storage from 6.86 MB in the teacher model to only 0.16 MB in the student model. This substantially lowers computational overhead. Moreover, the student model built on multi-layer perceptron and multi-layer convolutional structures achieves accuracy comparable to Transformer-based models (with the same hyperparameters, such as the number of attention heads and embedding dimensions as the teacher model, the parameter size of Transformer-based models is 3.51 MB). These findings confirm that GEME-Net, through knowledge distillation, effectively balances predictive performance and computational efficiency, making it well-suited for deployment in real-world resource-constrained environments.

To more intuitively demonstrate the predictive performance of our proposed model, we extract the actual and predicted passenger flow values for different functional areas, as illustrated in Fig. 13. The results show that GEME-Net achieves a high degree of alignment between predicted and actual values, with particularly strong performance during peak flow periods. Visual inspection of Fig. 8 reveals that GEME-Net can accurately capture peak flows across both high- and low-traffic areas, maintaining low prediction error rates at peak times. Notably, in high-demand regions, GEME-Net exhibits superior predictive accuracy, with significantly reduced errors, further confirming its effectiveness in handling large-scale passenger flow variations.

a Passenger flow in ticketing area (area 5). b Passenger flow in waiting area (area 10). c Passenger flow in check-in area (area 11). d Passenger flow at the airport arrival entrance (area 12). e Passenger flow in the eastern commercial area (area 14). f Passenger flow in the western commercial area (area 17).

The comparative analysis between the teacher and student models indicates that the teacher model consistently achieves lower prediction errors and more accurately captures subtle variations and peak flows. This reflects its stronger capacity to learn complex patterns and data dependencies. In contrast, although the student model exhibits slightly higher prediction errors, it still effectively captures the overall trends and major fluctuations in passenger flow. More importantly, it offers a significant advantage in computational efficiency, with a parameter size comparable to Transformer models, making it well-suited for lightweight deployment scenarios.

We conducted an ablation study to examine the sensitivity of passenger flow prediction to different input graphs and optimization modules. As shown in Table 6, removing the graph \({G}_{c}\) led to increases of 3.13% (RMSE), 7.38% (MAE), and 5.31% (WMAPE). Excluding the regional spatial clustering graph \({G}_{r}\) resulted in smaller error increases of 2.79%, 1.58%, and 1.61%, respectively. This indicates that \({G}_{c}\) has a greater impact on model performance, with the MAE increasing most significantly. Moreover, replacing \({G}_{c}\) with the physical topology graph (GEME-Net with \({G}_{p}\)) caused a further drop in prediction accuracy. This highlights the importance of capturing semantic and temporal information embedded in long-range mobility chains, which are more effective than raw physical topology for learning spatial dependencies. Among all modules, removing the EDSFM had the largest negative impact, increasing errors by 8.03% (RMSE), 9.39% (MAE), and 5.03% (WMAPE). These results underscore the effectiveness of incorporating public transit operational information and confirm the central role of EDSFM in the prediction framework. Specifically, by dynamically integrating causal features of transit events, EDSFM significantly enhances short-term prediction accuracy under event-driven flow fluctuations.

Discussion

This study explores the evolution mechanism of passenger flow distribution within integrated transportation hubs. Based on multimodal data fusion and the reconstruction of passenger mobility chains, we developed a novel passenger flow prediction model named GEME-Net. Specifically, this research uncovers how passenger flow fluctuations in different areas within an integrated multimodal infrastructure are significantly impacted by public transportation and reveals the topological characteristics of passenger mobility networks. Additionally, we propose a deep learning prediction framework that incorporates spatial semantic relationships and public transportation event encoding. Overall, the study integrates real-time multimodal transport data (railway and metro) with spatiotemporal passenger behavior features, and comprehensively applies techniques from behavioral analysis, spatial modeling, and deep learning to effectively uncover dynamic patterns of passenger movement under multimodal transport events. These insights provide methodological support for operators to implement adaptive real-time management strategies—such as targeted crowd dispersion and flexible scheduling, thereby enhancing the urban transport system’s responsiveness to dynamic mobility demands.

The detailed application process can be conceived as follows: firstly, high-precision monitoring sensor systems deployed in various functional areas within the hub dynamically capture real-time passenger flow and spatial distribution data, integrating operational information from multiple transportation modes, including railways, subways, buses, and flight schedules. Subsequently, this real-time data is transmitted to a central database, cleaned and integrated through data pre-processing modules, and then used as input for the GEME-Net prediction model. The model quickly processes this input to generate real-time predictions of future passenger flow distributions at a regional level (prediction time of teacher model: 6.87 s, student model: 1.41 s, Transformer: 4.97 s on validation set). These results are directly interfaced with the hub’s operational management platform, enabling instant visualization and alerting. When significant fluctuations or crowding trends are predicted, the system automatically triggers an early-warning mechanism, sending real-time alerts to relevant departments. Based on these insights, operational managers can implement precise passenger guidance, dynamically adjust facility resources (such as temporarily opening additional entrances or adjusting the operating hours of commercial facilities), and redeploy staff, significantly enhancing passenger flow management efficiency and safety assurance within the hub.

The application of knowledge distillation provides significant advantages to our prediction model. On one hand, knowledge distillation effectively reduces the number of model parameters and computational load, facilitating rapid, lightweight predictive responses during real-world deployments, thereby lowering reliance on computational resources. On the other hand, transferring knowledge from the teacher model to the student model allows the student model to maintain relatively high accuracy while significantly enhancing computational efficiency. The practical significance of this method is particularly pronounced in emergency response scenarios, allowing rapid deployment on terminals or edge devices, supporting managers in making efficient real-time decisions, thus greatly enhancing the agility and practicality of predictive responses.

Compared to traditional methods based on physical topology for spatial correlation, this research employs digital hub scenarios and behavioral experiments to reconstruct passenger spatial mobility chains, offering significant theoretical advantages. Traditional methods often struggle to capture nonlinear and diverse actual passenger activity paths, whereas digital scenarios combined with behavioral experiments can more finely characterize individual choices and collective interaction behaviors within space. Although the proposed method requires additional behavioral experiment data collection through digital twin environments, resulting in higher data acquisition costs compared to baseline models. This additional effort significantly enhances model performance. We also acknowledge that the behavioral dataset underpinning our mobility-chain reconstruction comprises 420 trajectories, sufficient for the present analyses yet still modest and future work will develop more efficient, scalable protocols to collect and reconstruct large-scale hub travel processes. Moreover, the value of the digital twin approach extends beyond improved predictive accuracy; it also supports long-term strategic functions such as spatial planning, operational optimization, and emergency response simulation, thereby playing a vital role in sustainable transport management. For example, establishing a digital hub could preemptively simulate and evaluate the impacts of temporary spatial layout adjustments on passenger behaviors. The method proposed in this study allows managers to anticipate potential impacts of layout changes, thereby promoting refined and advanced management of public transportation.

However, several limitations remain in this study. First, the current prediction framework has not yet fully incorporated real-time data from urban road traffic and flight operations, which may constrain its accuracy in forecasting overall flows across the integrated transport system. Future work will aim to include these data sources to enhance the model’s holistic forecasting capabilities. Second, this study characterizes the Hongqiao hub’s activity network and observes a small-world–like organization. We emphasize that this finding is case-specific: network structure in transport hubs is shaped by local layout, functional area, and operational practices. Future work should replicate the analysis across multiple hubs of varying sizes and service mixes, and across temporal regimes.

Data availability

The data generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available for legal/ethical reasons.

Code availability

The code developed for this study can be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Mohan K. M., Timme, M. & Schröder, M. Efficient self-organization of informal public transport networks. Nat. Commun. 15, 4910 (2024).

Yu, C. et al. Multi-layer regional railway network and equitable economic development of megaregions. npj. Sustain. Mobil. Transp. 2, 3 (2025).

Ma, C., Peñasco, C. & Anadón, L. D. Technology innovation and environmental outcomes of road transportation policy instruments. Nat. Commun. 16, 4467 (2025).

Wen, X., Si, B., Xu, M., Zhao, F. & Jiang, R. A passenger flow spatial–temporal distribution model for a passenger transit hub considering node queuing. Transport. Res. Part C. Emerg. Technol. 163, 104640–104640 (2024).

Auad-Perez, R. & Van Hentenryck, P. Ridesharing and fleet sizing for on-demand multimodal transit systems. Transport. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol. 138, 103594 (2022).

Van Der Voort, M., Dougherty, M. & Watson, S. Combining kohonen maps with arima time series models to forecast traffic flow. Transport. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol. 4, 307–318 (1996).

Kumar, S. V. & Vanajakshi, L. Short-term traffic flow prediction using seasonal ARIMA model with limited input data. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 7, 21 (2015).

Yang, H. et al. A network traffic forecasting method based on SA optimized ARIMA–BP neural network. Comput. Netw. 193, 108102 (2021).

Yang, H.-F., Dillon, T. S., Chang, E. & Phoebe Chen, Y.-P. Optimized configuration of exponential smoothing and extreme learning machine for traffic flow forecasting. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 15, 23–34 (2019).

Zhang, S., Zhang, J., Yang, L., Wang, C. & Gao, Z. COV-STFormer for short-term passenger flow prediction during COVID-19 in urban rail transit systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 25, 3793–3811 (2023).

Hoogendoorn, S. P., van Wageningen-Kessels, F., Daamen, W., Duives, D. C. & Sarvi, M. Continuum theory for pedestrian traffic flow: local route choice modelling and its implications. Transport. Res. Proc. 7, 381–397 (2015).

Zanariah, A. R., Mustafa, M., Ashaari, Y. & Sadullah, A. F. M. Modeling pedestrian behavior in rail transit terminal. Appl. Mech. Mater. 567, 742–748 (2014).

Helbing, D. & Molnár, P. Social force model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 51, 4282–4286 (1995).