Abstract

Achieving effective decarbonization requires technological innovation and understanding of behavior. Drawing on an interdisciplinary workshop, this paper emphasizes integrating behavioral insights into climate policy design to ensure technical effectiveness, social acceptability, and equity. We propose a framework combining behavioral data, choice modeling, agent-based simulation, and optimization to assess policy impacts under deep uncertainty. Although focused on transport, the approach generalizes across sectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Designing and implementing actions for decarbonization necessitates a comprehensive understanding of human behavior. While technological advancements are essential, they alone cannot resolve the multifaceted challenges of eliminating greenhouse gas emissions. Behavioral change is also necessary, and achieving it requires the use of targeted interventions or behavior change strategies that address individual and contextual factors influencing decision-making. Effective decarbonization strategies must integrate behavioral insights pertaining to multiple actors, including individuals/households, businesses, and government organizations — all of whom experience uncertainty in their decision-making. Behavioral choices significantly influence final consumer demand, mobility patterns, energy choices, and the adoption and use of new technologies. For instance, promoting sustainable mobility behaviors requires not only the availability of ecofriendly transportation options but also the willingness of individuals to adopt and use these options. Understanding these behavioral aspects is critical for designing climate policies that are technically sound, socially acceptable, and balance the dual objectives of achieving zero carbon emissions while enhancing well-being and happiness.

Our workshop participants, authors of this paper, who include experts in transportation and energy research and have disciplinary backgrounds in engineering, economics, econometrics, environmental psychology, applied math and data collection, identified a range of strategies influencing climate mitigation actions, including technology development, policy and regulation, information and education, compensation and redistribution of the costs and benefits, as well as strategies that account for key aspects of behavior. One such aspect is behavioral heterogeneity. Individuals have different beliefs, preferences, needs, and constraints that will affect their responses to emissions mitigation measures. Other overarching behavioral factors include willingness to pay and public acceptance, and the role of emotions and seemingly “irrational” responses.

Designing decarbonization policies presents several significant challenges. The objective of achieving zero carbon emissions requires substantial changes in energy production, consumption, and overall societal behavior. Simultaneously, policies must account for adverse impacts on well-being and happiness, ensuring that transitions to low-carbon systems do not adversely affect quality of life, which is also important to secure public support. Additionally, minimizing the costs of new technologies and energy is crucial to make decarbonization economically viable and politically acceptable. Furthermore, forecasting and assessing the impact of individual and combined climate change mitigation actions is complicated by deep uncertainty. This uncertainty arises from various sources, including unpredictable technological advancements, variable economic conditions, complex human behavior and contextual factors, and uncertainties about how the climate system will develop. Deep uncertainty makes it challenging to predict long-term outcomes and to design robust policies that remain effective under a wide range of future scenarios. Therefore, policymakers must adopt flexible, adaptive approaches and continuously update their strategies based on new information and insights1,2.

This complexity is illustrated in Fig. 1, which is presented in two panels. In both panels, the x-axis represents the degree of decarbonization. The top panel shows the corresponding mitigation costs, while the bottom panel shows the associated level of well-being. In both cases, the shaded areas around the curves represent the uncertainty in the estimation of these indicators. Two examples are highlighted: integrated land-use planning (e.g., ref. 3), which achieves a relatively low degree of decarbonization at low cost while enhancing well-being, and electric vehicles (e.g., ref. 4), which contribute to a higher degree of decarbonization but at higher costs and with smaller well-being gains.

In both panels, the horizontal axis represents the degree of decarbonization. a The top panel reports mitigation costs, which rise nonlinearly as decarbonization increases. The light-blue shaded region around the curve indicates uncertainty in the estimated costs. b The bottom panel reports the associated level of well-being for two conceptual trajectories, each surrounded by a light-blue uncertainty band. In both panels, the orange-filled circles highlight the case of integrated land-use planning, which achieves a relatively low degree of decarbonization at low cost while enhancing well-being. The vermillion-filled circles highlight electric vehicles, which contribute to a higher degree of decarbonization but at higher costs and with smaller well-being gains.

While the figure is conceptual, its form is grounded in empirical and theoretical evidence on the cost-effectiveness and complexity of transport decarbonization measures. The steep initial rise in decarbonization effectiveness at low cost reflects well-documented findings from integrated land-use and transport planning, which can deliver substantial emission reductions alongside co-benefits such as improved public health, equity, and accessibility, often at relatively modest investment levels5. Similarly, investment in high-quality cycling infrastructure can increase cycling rates by 60–90% with moderate spending, reinforcing the steep early gains depicted6.

As costs increase toward more capital-intensive measures, the curve flattens, consistent with marginal abatement cost (MAC) curves in energy-system studies7. These curves typically result from ranking mitigation measures by cost-effectiveness, beginning with the lowest-cost options and progressing to those with higher unit costs. In the transport sector, this pattern reflects the greater technical, institutional, and behavioral challenges of deeper decarbonization, such as shifting entire vehicle fleets to zero-emission technologies or overhauling infrastructure networks.

We propose a methodological framework to help policymakers deal with uncertainty; design policies and regulations; understand public responses; and forecast the impact of policies and technologies on behavior, while identifying effective strategies for communicating these impacts to stakeholders.

The framework includes surveys of human behavior, choice models of technology and policy adoption, choice of energy sources, and consumption behavior. Bundles of decarbonization measures can then be evaluated using agent-based simulations where behavioral models predict the reactions by different stakeholders and the consequent reduction in emissions. We focus on decarbonization of the transport sector for the remainder of this paper; however, the framework we employ is applicable to other sectors as well.

While the framework is designed to support evidence-based policy design by anticipating behavioral responses and emissions outcomes, we recognize that decarbonization is ultimately embedded in broader societal and institutional contexts. Structural factors such as infrastructure provision, planning decisions, market dynamics, and regulatory environments shape both behavioral possibilities and technological pathways. Furthermore, the distributional impacts of climate policies and the processes through which they are designed raise important questions of justice, equity, and political legitimacy. Although these issues are not explicitly modeled within our framework, they can be partially addressed through the evaluation of distributional outcomes8 and the design of compensatory or reinvestment mechanisms. The framework is thus best understood as a decision-support tool that can inform policy within a wider governance process — one that must also account for questions of voice, representation, and institutional power.

Kaya identity for transport sector decarbonization

The Kaya identity9 is a simple generalized formula that expresses carbon emissions as the product of three factors.

The total CO2 emissions of the transport sector can be decomposed using the Kaya identity as follows:

where the sum runs over all transport modes m, E is the amount of energy consumed, and PKT stands for passenger kilometers traveled. Reducing the total CO2 emissions can therefore be achieved by addressing each of these three factors:

-

\({(\frac{{CO}_{2}}{E})}_{m}\) represents the fuel choice for mode m. This factor can be reduced through the adoption of energy carriers with a lower-carbon content, such as electricity, biofuels, synthetic fuels, or hydrogen. Importantly, this ratio needs to be evaluated on a lifecycle basis.

-

\({(\frac{E}{PKT})}_{m}\) represents mainly the technology choice for each mode m, indicating how efficiently energy is used per unit of transport activity. Enhancing fuel efficiency through technological advancements in vehicle design and improving traffic flows to minimize congestion leads to lower values of this factor. In theory, this factor also includes a behavioral element, that is, the occupancy level. However, multiple studies have shown that increasing vehicle occupancy is extremely challenging10,11. Still, supportive policies and measures that facilitate and encourage shared mobility — such as incentives for carpooling, improved ride-sharing platforms, and flexible mobility services that address concerns around convenience, privacy, and reliability — have the potential to create favorable conditions for individuals to adopt higher-occupancy travel behaviors.

-

PKTm reflects the total travel demand in passenger-kilometers of each mode, that is, travel behavior. Strategies to reduce this component involve promoting modal shifts to more fuel-efficient modes of transport, encouraging travel at different times of the day to avoid congestion, reducing the overall need to travel (e.g., through telecommuting or digital services), combining trips to improve efficiency, and supporting active mobility options such as cycling and walking, which do not rely on fuel consumption.

The Kaya identity provides a useful and intuitive decomposition of CO2 emissions into analytically tractable components. Its multiplicative structure highlights measurable factors — such as fuel carbon content, energy efficiency, and passenger-kilometers traveled — which make it a practical tool for organizing the various contributors to emissions. At the same time, it should be seen as one lens among many, offering a structured view of key drivers while not capturing the full complexity or societal dimensions of transport decarbonization.

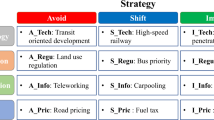

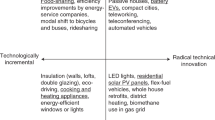

The Avoid-Shift-Improve (ASI) framework shares similarities with the Kaya decomposition in that both organize emissions drivers into distinct components12. In broad terms, “Avoid” corresponds to reducing travel demand, “Shift” to changes in mode and energy carrier, and “Improve” to technological efficiency and lower-carbon energy. ASI has clear strengths as a policy and communication framework: it aligns naturally with policy packages (e.g., demand management + modal alternatives + efficiency standards), helps highlight co-benefits (health, equity, safety), and is widely used by practitioners.

For the purposes of behavioral modeling, however, ASI’s categories are not strictly separable in decision processes. In discrete-choice terms, avoiding a trip (not traveling, teleworking, combining trips) often emerges from the same utility maximization problem as shifting mode, destination, or timing; both are shaped by the same constraints (time, budget, accessibility) and by expectations, perceptions, norms, and emotions. Treating Avoid and Shift as independent levers can therefore obscure substitution patterns. A behaviorally coherent operational distinction is between short-term responses (e.g., trip-level mode, route, timing) and long-term commitments (e.g., vehicle ownership, dwelling location, fuel/technology choice). Our Kaya-based framing accommodates this by tying short- and long-term decisions to the three multiplicative components of emissions and estimating them with microdata, while ASI remains valuable for structuring policy packages and stakeholder dialog.

Other related approaches — such as Low Energy Demand (LED) pathways13 or sufficiency strategies for climate mitigation—frame mitigation in terms of reducing energy demand through interdisciplinary perspectives on social change. While valuable for long-term visioning, the quantitative LED studies we are aware of typically abstract from explicit modeling of human behavior14. Similarly, sufficiency-oriented frameworks emphasize behavioral change but remain largely qualitative.

In contrast, our framework is explicitly methodological and model-based, designed to integrate behavioral realism — that is, the extent to which a model or framework faithfully represents the way people actually make decisions, adapt, and behave, rather than relying on oversimplified, stylized, or purely rational assumptions — into quantitative assessments. It therefore provides a concrete operationalization that complements these higher-level conceptual approaches, enabling a more detailed analysis of how behavioral dynamics influence mitigation outcomes.

Variations of the Kaya identity are widely applied in the climate mitigation literature. For example, Mc Collum and Yang15 employ it to analyze emissions pathways and associated mitigation options, Girod et al.16 use it to estimate the consumption level reductions required to meet climate targets, and Sharmina et al.17 apply it to track and assess mitigation progress across key sectors.

In this paper, we use the Kaya identity as a framing device to quantitatively represent the behavioral factors that influence its three right-hand-side components: carbon intensity of fuels, energy intensity of transport, and total transport activity. Our approach is explicitly data-driven and operationalized through econometric models and simulation tools. In this context, “behavior” encompasses the measurable decisions and actions of key actors in the transport system:

-

Individuals, whose travel choices vary with trip purpose, distance, party size and composition, household characteristics, socio-economic status, and social influence.

-

Transport providers, whose business models, network designs, fleet compositions, and operational strategies shape technology and fuel choices, and whose adoption of innovations is influenced by costs, performance, and market or policy uncertainty.

-

Governments and regulators, whose policies—such as infrastructure investment, regulation, information campaigns, education, pricing signals, and compensation or redistribution mechanisms—affect both individual and firm-level decisions.

These behaviors are modeled across different decision scales and time horizons, from day-to-day mode choice to long-term investment in low-carbon technologies. While our scope does not extend to all societal behaviors (e.g., political activism outside the transport sector), it captures the key behavioral mechanisms that can be quantified and modeled to explain changes in the Kaya identity’s components and, ultimately, CO2 emissions.

In the “Considerations in modeling human behavior” section, we discuss key considerations in modeling human behavior, including behavioral heterogeneity, social influences, and the introduction of new technologies. The “Government actions” section focuses on various government actions that can influence each factor in the Kaya identity. And in the “Methodological framework” section, we describe a comprehensive modeling and simulation framework that can be used by policymakers to design, test, and refine decarbonization strategies.

Considerations in modeling human behavior

Behavioral heterogeneity

The extent to which people engage in pro-environmental behavior varies, depending on individuals’ capacities and motivation to engage in the behavior18,19,20. Behavioral heterogeneity thus depends on contextual factors, differences in personal ability to act, and the motivation to act. Contextual factors include available infrastructure, technology, market design, price regimes, and regulations (we elaborate on these below). For example, individuals are more likely to drive an electric car if they have access to a fast and reliable charging infrastructure and when electric cars are affordable (e.g., via subsidies), and people can only use public transport when convenient public transport is available.

Differences in personal ability to act are another factor leading to behavioral heterogeneity. Perceived ability depends on personal characteristics such as education level, knowledge, income, and family situation. For example, perceived ability to act pro-environmentally will be higher when people have better knowledge of the causes and consequences of environmental problems, and understand how to mitigate these problems19. Income is also a key variable explaining behavioral heterogeneity. There is empirical evidence21 that lower-income groups in the USA consistently prioritize environmental protection over economic growth. Higher-income groups may also feel more able to act pro-environmentally22, particularly when such actions are financially costly. Indeed, many options, such as investments in home insulation or PV19, or adoption of electric vehicles23, are more accessible to higher-income individuals. Further, the family context can restrain some behaviors (e.g., people may need a car to pick up children after work).

The third motivation to act affects behavioral heterogeneity. People consider various costs and benefits of actions, and weigh these consequences differently depending on the values they endorse19. Values reflect general goals that people strive for in their lives, which affect how they weigh different costs and benefits of actions, and which choices they make24,25. Four types of values are particularly important to understand environmental choices: hedonic values (i.e., striving for pleasure, reducing effort), egoistic values (i.e., striving to enhance and secure one’s resources such as money and status), altruistic values (i.e., striving to enhance the well-being of others) and biospheric values (i.e., striving to protect nature and the environment26). In general, people with strong hedonic and egoistic values are less likely to act pro-environmentally, as doing so is oftentimes somewhat costly (e.g., buying an electric vehicle) or less comfortable (e.g, traveling by bus rather than by car). In contrast, stronger altruistic and particularly stronger biospheric values generally promote pro-environmental actions, as such actions benefit nature, the environment, and the well-being of others, including future generations.

People consider a range of individual, collective, social, and emotional costs and benefits when making decisions19,27. First, they are more likely to act pro-environmentally when such actions offer individual benefits at low cost28. Picard et al.29 show that the perceived costs and benefits of driving vary depending on whether individuals commute with their spouse or travel alone. Second, people are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behavior when they are concerned about environmental problems, feel a sense of responsibility to reduce them, and view themselves as supportive of the environment19. Fehr and Gächter30 demonstrate experimentally that many individuals are willing to punish free-riders in public goods games, even when doing so is personally costly and offers no material benefit. Third, social norms, i.e., the expectations and behaviors of others, can significantly influence individual choices. People tend to follow such norms to gain social approval, avoid disapproval, or because they believe it is the right thing to do19. For example, people are more likely to install solar panels when many neighbors already did so31. Fourth, people are more likely to act pro-environmentally when they anticipate that such actions will generate positive emotions, such as a sense of pleasure or moral satisfaction, and may avoid certain behaviors if they expect these to result in negative feelings25,32,33.

Our discussion indicates that many factors affect individual choices and the likelihood that people act pro-environmentally. These factors vary across individuals, explaining the heterogeneity in choice behavior. It is important to understand these different factors and their impacts on individual choices and behaviors, so that policies can be appropriately designed to mitigate climate change. Table 1 summarizes exemplary choices with respect to each of the Kaya identity-based factors that relate to the three components representing behavioral heterogeneity. Integrating these factors and choices into transport models would increase the representation of consumer and producer heterogeneity.

Technology adoption and infrastructure requirements

The introduction of new technologies can bring about challenges, such as increased demand for energy or travel (known as induced demand) and hidden economic, environmental, or social costs that may not be immediately apparent. These factors necessitate careful consideration to prevent unintended consequences.

For instance, while the rapid uptake of EVs is expected to reduce tailpipe emissions and, in most regions, is increasingly supported by growing shares of renewable electricity, the transition still raises important infrastructure and resource concerns. The additional electricity demand from EVs is unlikely to negate their emissions benefits unless it is met with carbon-intensive sources such as coal, which is increasingly rare in many countries34,35. However, a full transition to electrified transport could place significant strain on grid capacity and requires substantial investments in charging infrastructure36. Furthermore, it entails environmental and geopolitical risks linked to the extraction and processing of critical raw materials (e.g., lithium, cobalt, and rare-earth elements), as well as challenges associated with battery manufacturing and end-of-life management. Broader infrastructure considerations are thus essential when implementing decarbonization strategies, as they provide the physical and systemic foundation for supporting sustainable technologies and practices. Table 2 provides an example of propagating infrastructure requirements for each of the three Kaya identity factors.

Another challenge of innovative and sustainable infrastructure projects can be the time to impact, as these projects are influenced by a complex chain involving regulatory approvals, funding allocations, stakeholder consultations, and end-user behavior. For instance, the scalability of EV charging infrastructure hinges on industry partnerships and governmental support to expand access and adoption across diverse geographical regions37.

The uptake of any new technology, and the infrastructure accompanying it, typically begins with early adopters. Compared to early adopters, later adopters attach greater importance to perceived usefulness, affordability, accessibility, and policy incentives38. However, early adopters on their own are seldom enough to make something financially viable. To scale up, funding mechanisms are required, with initiatives ranging from private-public partnerships to support from charities and foundations such as the Solar Impulse Foundation, which advocates for sustainable solutions.

Finally, public willingness to pay for both the additional costs of using infrastructure (marginal costs) and the larger upfront investments (capital expenditures) is essential to ensure that innovative infrastructure projects are financially secure and can sustain themselves over time.

The time it takes for traditional infrastructure to have an impact (“time to impact”) can be shortened if it is designed to address an existing demand for public transportation or to encourage people to shift from using polluting cars to cleaner public transport. This is the case, for example, of the Crossrail project in London, or the Grand Paris Express intended to improve Paris accessibility and attractiveness, and to make the Paris region a polycentric city39,40. However, funding such large infrastructures also raises challenges.

Finally, uncertainties regarding the environmental and societal impacts of infrastructure projects necessitate careful consideration. Issues such as their effects on biodiversity and human communities, alongside local and global perceptions of these impacts, can spark social protests and influence decision-making (see Heathrow’s 3rd runway41,42, or the UK national grid upgrade43, or the local opposition to the Grand Paris Express project in the most productive agricultural lands around Paris44).

Government actions

Policies, programs, rules, and regulations enacted at all levels of government are obviously designed to influence the behavior of individuals, households, and business establishments as described in the following subsections.

Market-based policies

Market-based environmental policies encourage behavior change (in firms and/or individuals) through market signals by leaving economic agents a choice, as opposed to explicit regulatory directives or ‘command’ and ‘control’ regulation (technology-based or performance-based standards). Broadly, market-based policies include pollution charges and deposit-refund systems (e.g., carbon taxes enacted in European countries in the 1990s), tradable permits and cap-and-trade schemes (e.g., the U.S EPA’s 1986 Clean Air Act, which mandated an emission trading policy for ‘criteria’ pollutants; the EU ETS), subsidies to reduce pollution, and market barrier reductions (removing explicit or implicit barriers to market activity). As such, they can affect all factors forming the Kaya identity.

Although governments at all levels are starting to implement market-based instruments45,46, they have, in general, been slow to do so. A key challenge has been resistance from interest groups and the public for a variety of reasons. There is a legitimate concern that market-based instruments may lead to adverse distributional impacts, exacerbate existing inequalities, and give rise to environmental injustice. This is particularly problematic when the financial burden of such policies—such as carbon pricing or energy taxes—falls disproportionately on vulnerable groups, who often have fewer resources to absorb additional costs or adapt their behavior. These same groups are also frequently the most exposed to environmental risks, making them doubly disadvantaged by both economic and environmental harms. For example, a carbon tax often places a heavier burden on lower-income households, as they spend a larger share of their income on energy and everyday goods affected by the tax, especially before any compensation or revenue redistribution is applied47,48,49.

Market-based tools like carbon pricing and emissions trading have often been introduced too weakly to be effective. In many cases, carbon prices have been too low or pollution limits too loose to drive meaningful change46. Participation has sometimes been limited, and the expected cost savings have not materialized50. These outcomes are partly due to unrealistic assumptions about how people and companies behave, flaws in policy design, and the fact that many companies lack the internal capacity to take full advantage of these systems51.

The effectiveness of market-based policies strongly depends on how individuals and firms respond to price signals, making it especially important to understand and anticipate behavioral reactions, which are often uncertain and context-dependent. At the same time, generating accurate predictions about the likely impacts of the policy is critical in garnering public acceptance and underscores the role of behavioral models. For instance, the Stockholm congestion charging scheme is instructive; initial public skepticism changed after the scheme was introduced, largely due to the evident reduction in congestion52,53, and in environmental problems54.

Suitable approaches to address the dual challenge of anticipating behavioral responses and fostering public support (in the context of both environmental and congestion externalities) include recycling/dividend schemes to address welfare and distributional impacts, the use of behavioral modeling and optimization to design policies that account for likely public reactions, careful framing of policy instruments (for example, users in Stockholm were more receptive when the term “environmental charges” was used instead of “congestion charges”), and information campaigns. More broadly, no single policy instrument is likely to offer a complete panacea toward decarbonization, as no single instrument can address all barriers to change.

Table 3 provides two examples of market-based policy measures and their potential impact on each of the Kaya identity factors. As is visible, the impact of the two policies on travel behavior can lead to opposite directions.

Regulations

Regulations serve as policy tools that force behavioral change to address environmental challenges. They can be categorized into supply-oriented and demand-oriented approaches. Supply-oriented regulations, such as mandates for minimum sustainable aviation fuel mixes (affecting CO2/E in the Kaya identity), directly influence the composition and availability of products in the market by placing rules on the supplier. Demand-oriented regulations are placed on the end-user/consumer. Measures like establishing low-emission zones in urban areas, setting speed limits, or banning the use (rather than the production) of internal combustion engines are examples of policies designed to reduce emissions and improve air quality by prohibiting some types of targeted user behavior.

As with market-based policies, regulations can affect each factor of the Kaya identity. Regulations aiming at fuel specifications affect CO2/E, whereas those aiming at vehicle fuel economy impact E/PTK and PKT. However, in contrast to market-based measures, the lower marginal costs of driving associated with a more fuel-efficient vehicle can result in an increase in vehicle travel and thus traffic congestion, air pollution, and other externalities. For the industrialized world, this rebound effect was estimated to be around 12% in the short run, increasing to 32% in the long run55.

While regulations can be enacted quickly and have immediate legal effect, their environmental impact often unfolds gradually. First, considerable time is needed to build support among stakeholders and reduce public and political resistance. Once passed, the regulation must be aligned with existing legal frameworks and implemented in a way that meets all legislative requirements. Industries may also require a substantial lead-in time to adjust and comply with new standards. For example, if a regulation affects vehicle design, long fleet turnover times must be taken into account, meaning that the full environmental impact of such measures may not be realized for decades (e.g., ref. 56). Furthermore, behavioral adaptation must occur in response to the regulation, which also takes time. While these challenges are often associated with regulatory instruments, they also apply to other policy tools that aim to influence long-term technology choices, such as vehicle adoption, and should be considered when evaluating short-term versus long-term effectiveness. Skipping any of these steps risks undermining a regulation’s durability, early uptake, or overall impact.

Table 4 presents two examples of regulatory policy measures along with their impact on each of the Kaya identity’s factors. As with regulatory measures, depending on the implemented policy, the outcome on travel behavior can be fundamentally different.

Information and education

Providing information and education on the causes and consequences of environmental problems or on ways to reduce these problems generally increases people’s knowledge. However, it often does not encourage pro-environmental actions19, as people typically face other barriers to act as well. Indeed, informational strategies are especially effective when the targeted behavior is not very inconvenient or costly (in terms of money, time, effort, and/or social disapproval), and when individuals do not face important external constraints on behavior18.

Social influence approaches that communicate what other people do or think can encourage mitigation actions, as can social models of desired actions. For example, information on what others do or expect one to do, providing role models, and community approaches that promote behavior change from the bottom up can encourage pro-environmental actions19. Other interventions that utilize the social context are spreading awareness of environmental impacts through social media57, leveraging “social marketplaces” where people encourage each other in myriad ways58, or mobile app-based games to connect with communities59,60,61.

Information and education programs can complement and enhance the impact of regulatory and market-based measures by communicating the need for and the goals of these policies, and fostering understanding of their positive impacts18. For instance, explaining the rationale behind and positive impacts of carbon pricing can enhance public support and compliance with these measures. Hence, by integrating information campaigns with regulatory frameworks and market incentives, policymakers can reinforce the effectiveness of these policies, encouraging broader societal participation and support. Such integrative policies are likely to address multiple barriers to change, thereby catalyzing sustainable behavioral change.

Information and education campaigns can also support the introduction of cleaner technologies. For example, electric vehicles (EVs) illustrate how factors like drivetrain options, costs, and driving range can significantly influence consumer choices62. Awareness campaigns and educational efforts can play an essential role in disseminating information about these parameters, ensuring consumers can make informed decisions63. Additionally, marketing initiatives that highlight options like battery leasing for EVs can help inform consumers about ways to reduce upfront costs, thereby encouraging broader adoption64.

Table 5 presents the example of automobile CO2 emissions labeling and the potential consequences for each of the three Kaya identity factors.

Compensation and redistribution

A ‘just transition’ entails that climate change policies address the inequitable distribution of both the impacts of climate change and the costs and benefits of mitigation efforts. Marginalized and low-income populations — who are least responsible for past greenhouse gas emissions and have benefited the least from carbon-intensive economic development or decarbonization policies (such as subsidies or incentives mostly used by higher-income groups) — are often the most vulnerable to climate impacts and possess the fewest resources to adapt. It is also essential to consider the potential regressive effects of climate policies, particularly market-based instruments like carbon pricing, which can disproportionately burden low-income households and exacerbate existing social and economic inequalities, possibly leading to social protest such as the Yellow Vests crisis studied by Chamorel65. The political economy of a ‘just transition’ is complex. It involves questions of recognition — ensuring that the concerns and identities of all social groups are acknowledged and respected — alongside procedural justice, which relates to fair and inclusive decision-making processes, and distributive justice, which concerns the fair allocation of resources and responsibilities. It also requires attention to distributional outcomes, meaning the actual, measurable impacts of climate policies on income, ethnicity, gender, and other forms of inequality, both within and across countries66,67. For instance, transition-related job losses (for example, from the closure of coal mines, fuel and gas plants) are likely to be concentrated in areas and social groups that already have been affected by deindustrialization and globalization68. Ethnic inequalities arise when large-scale renewable energy infrastructure projects (e.g., hydroelectricity) or forest protection initiatives lead to forcible relocation and the loss of traditional livelihoods67,69.

Addressing distributional justice toward a just transition requires appropriate measures of compensation and redistribution. For instance, in the case of market-based policies such as a carbon tax or a congestion toll, this would involve dedicating or earmarking revenues in ways that benefit ‘losers’ (for example, lump-sum transfers have been adopted for the federal carbon tax in Canada46). Other compensation schemes for climate policies include environmental tax reforms that reduce labor taxation, green deal plans (investments in areas of the green economy that could stimulate job creation), place-based policies (a local targeted version of green deal plans that focuses on spatial inequalities induced by the green transition), and progressive green subsidies (i.e., to remove financial constraints for the poor and accelerate the adoption of green technologies)70. Public support for these policies tends to increase when revenues are used in ways perceived as fair and beneficial—for example, through direct rebates to households, investments in public services, or targeted support for vulnerable groups, rather than across-the-board tax cuts or general budget spending71.

However, there are several challenges associated with direct refunds and compensations. First, it is challenging to determine adequate compensation since it requires quantifying exactly the benefits and losses at the individual level. For this reason, achieving a Pareto improvement (where no individual is worse off) is often considered a near impossibility by economists46. Another challenge is that refunding schemes may create undesirable incentive effects (e.g., users trying to overstate losses) and open the door for strategic behavior that undermines efficiency gains from the policy46. Finally, administrative and transaction costs could be prohibitive, but these can conceivably be minimized through technology.

Empirical evidence further supports the need to target high-income behavioral patterns. For example, private jet emissions from wealthy individuals increased by 46% from 2019 to 2023, totaling 15.6 MtCO2 annually72. More broadly, the wealthiest 10% globally are responsible for 36–45% of total greenhouse gas emissions, with transport-related affluence being a key driver73.

Note that fully addressing the questions of justice and power in the context of transport decarbonization requires a level of theoretical and empirical elaboration that goes beyond the scope of this paper. As noted in the introduction, our focus is on providing a methodological framework to support the design and evaluation of decarbonization policies, particularly by anticipating behavioral responses and assessing distributional outcomes. While we discuss compensation and redistribution mechanisms, a comprehensive integration of structural inequalities, power asymmetries, and procedural justice into the modeling framework would require additional components — such as participatory processes, institutional analysis, and governance modeling — which are not developed here.

Joint effect of policies

When policies are designed in isolation, without considering the presence of other instruments, they may create distortions or even undermine their own objectives. For example, implementing congestion pricing without investing in adequate public transport alternatives may disproportionately penalize certain groups and reduce overall policy effectiveness.

Synergies and trade-offs often arise across sectors. Consider the interaction between transportation and energy systems: road pricing policies designed to manage congestion can influence the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), thereby affecting electricity demand and grid operations. Conversely, dynamic energy pricing alters the relative cost of EV use compared to conventional vehicles, with direct implications for travel demand and mode choice. Designing an optimal joint pricing framework that accounts for both transport and energy sectors can unlock co-benefits such as reduced congestion, smoother demand on the grid, and improved environmental outcomes.

Managing joint effects also requires avoiding contradictions and overlaps. Uncoordinated regulations can create uncertainty, discourage compliance, or impose excessive burdens on stakeholders. Effective coordination across government levels and sectors, combined with early stakeholder engagement, is critical to ensure coherent and credible policy packages.

Revenue recycling is another lever to strengthen complementarities. Using proceeds from carbon pricing or environmental fines to support low-income households, invest in renewable energy, or expand public transport can enhance both fairness and political acceptance74. Similarly, targeted investment in charging infrastructure for underserved peri-urban and rural areas, or in multifamily residences where private charging is limited, can mitigate inequities. Without such targeting, EV subsidies combined with energy demand management policies may disproportionately benefit high-income households who can afford residential battery storage systems, thus widening gaps in energy costs and access.

In summary, addressing the joint effects of policies calls for a holistic approach that explicitly considers cross-sectoral dynamics, distributional impacts, and institutional coordination. Policy mixes are not the exception but the rule: effective decarbonization depends on packages of complementary instruments that balance efficiency, equity, and feasibility. The methodological framework developed in this paper is designed to capture such interactions by quantifying behavioral responses to multiple instruments applied jointly rather than in isolation. By fostering synergies and minimizing conflicts, integrated policy packages can deliver more effective, equitable, and durable pathways toward transport decarbonization.

Public acceptability

The extent to which options are evaluated (un)favorably by the public plays an essential role in the implementability of proposed policy measures. Hence, it is critical to understand which factors affect the acceptability of policies, as this provides important insights into which strategies could be implemented to address public concerns. Four factors appear to affect public acceptability of options: perceived costs and benefits of options, distributive fairness, procedural fairness, and trust in responsible actors.

First, acceptability is higher when people believe options have more positive and fewer negative effects for self, others, or the environment19. Because of this, policies ‘rewarding’ pro-environmental actions are more acceptable than policy ‘punishing’ actions that increase environmental problems. Pro-environmental options and policies are evaluated as more acceptable when people strongly value the well-being of other people and the environment, when they are more concerned about environmental problems, and when they feel more responsible and capable of helping reduce these problems, probably because this increases the likelihood that people recognize and value the environmental benefits of options and policies19. Further, the more people are aware of environmental problems, the more strongly they prefer governmental regulation and behavior change rather than free-market and technological solutions75. Acceptability can increase when people experience that an option or a policy has more positive effects than they expected, which suggests that effective policy trials or being able to try out an option can build public support for sustainable options and policy19.

Second, public acceptability depends on how the costs and benefits of options and policies are distributed across groups (i.e., distributive fairness): sustainable options and policies are more acceptable when their costs and benefits are distributed equally across groups, and when vulnerable groups, future generations, and nature and the environment are protected25. Distributive fairness can be enhanced by compensation schemes, for example, by offering additional benefits to people who would be negatively affected by the proposed changes. For example, public acceptability of pricing policies is higher when redistributing revenues toward those affected74, and when earmarking revenues for environmental purposes25,26,76.

Third, public acceptability of sustainable options and policy depends on which decision procedures were followed, as reflected in perceptions of procedural fairness. The implementation of sustainable options and policies is perceived as more fair and acceptable when transparent procedures have been followed, when the public or public society organizations could participate in the decision-making, and when people feel that their interests and concerns have been taken seriously25.

Fourth, public support is higher when individuals trust responsible parties19. Trust in responsible parties is important as the general public typically does not have sufficient expertise or the capacity to understand all aspects of options, and thus needs to rely on the expertise and good intentions of agents who are responsible for designing and implementing the options. Public acceptability appears to more strongly depend on trust in the integrity of responsible actors (i.e., whether they are believed to be transparent and honest) than on the perceived competence of responsible actors77.

Policies and Kaya identity

To conclude this section on policies, the following lists present a selection of climate mitigation policies categorized according to the three components of the Kaya identity applied to the transport sector. Each policy aims to reduce total CO2 emissions by targeting either the carbon intensity of energy use (CO2/E), the energy efficiency of transport activity (E/PKT), or the overall travel demand (PKT).

\({(\frac{{CO}_{2}}{E})}_{m}\) — Fuel choice

-

Carbon taxes to shift demand toward lower-carbon energy sources.

-

Emissions trading systems (cap-and-trade) are used to limit total emissions from fuels.

-

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) mandates promote low-carbon aviation fuels.

-

Fuel specifications require cleaner energy carriers.

-

Subsidies for electric vehicles (EVs) to support low-carbon fuel adoption.

-

Public investment in renewable energy is funded through climate policy revenues.

-

Information campaigns promoting the adoption of lower-carbon fuels.

\({(\frac{E}{PKT})}_{m}\) — Technology choice

-

Fuel economy regulations require more efficient vehicles.

-

Emissions labeling for vehicles to inform technology choices.

-

Congestion pricing to improve traffic flow and reduce energy intensity.

-

Green deal plans to invest in efficient mobility technologies.

-

Place-based policies targeting energy-efficient infrastructure investments.

-

Progressive green subsidies to improve access to efficient technologies.

-

Education campaigns highlighting the cost and performance of clean technologies.

PKTm — Travel behavior

-

Low-emission zones restrict high-pollution travel in cities.

-

Speed limits and bans on internal combustion engine use.

-

Congestion tolls are used to discourage excessive car use in peak hours.

-

Modal shift incentives encourage the use of public or active transport.

-

Social influence campaigns promoting sustainable mobility norms.

-

Gamification and mobile apps to engage communities in behavior change.

-

Compensation schemes for low-income travelers affected by pricing policies.

-

Revenue recycling to support users affected by behavioral regulations.

-

Electric vehicle cost-sharing (e.g., battery leasing) to broaden adoption.

Methodological framework

The complexity of behavioral dimensions in response to climate change actions necessitates the design and development of decision-aid tools. These tools aim to assist policymakers in designing, optimizing, and anticipating the impacts of various measures. This section introduces a methodological framework for developing such tools that involves the collection of behavioral data and the design of a modeling framework.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the methodological framework integrates policy design, behavioral modeling, performance measurement, and optimization in a continuous, iterative process. This approach utilizes a diverse range of input data, including exogenous data such as energy prices and economic conditions78; behavioral data (including factors influencing behavior) collected through experiments and surveys (see “High-quality behavioral data” section); and a global typology of individuals and households representing different demographic, socio-economic, and geographic segments. This typology also represents the population of business establishments. Within such a typology, synthetic populations of individuals, households, and establishments with the same statistical properties of the actual populations can be created79,80.

The framework integrates policy design, behavioral modeling, performance measurement, and optimization in a continuous, iterative process. It uses a diverse range of input data, including exogenous information such as energy prices and economic conditions, behavioral data collected through experiments and surveys, and a global typology of individuals, households, and business establishments representing different demographic, socio-economic, and geographic segments. Within this typology, synthetic populations of individuals, households, and establishments can be generated that reproduce the statistical properties of the actual populations.

Behavioral models and simulation

The role of behavioral models and simulations is to predict individual and group responses at a disaggregate level. These models can simulate various scenarios to understand potential outcomes of the policy measures. They generate various numerical indicators that characterize the behavioral responses for each of those scenarios.

Individuals make numerous choices that are relevant for analyzing decarbonization policies. These choices pertain to their activities, travels, and energy consumption, among others. Some decisions are long-term, such as house location, the type of heating system, or vehicle ownership, while others are short-term, like travel mode and destination for specific activities. These decisions may be modeled simultaneously, as proposed by Pougala et al.81, Pougala et al.82, and Rezvany et al.83, or they may be modeled sequentially (e.g., ref. 84). An example of a behavioral modeling and simulation platform for urban transportation that adopts a sequential approach is shown in Fig. 384.

In the same spirit, Knapen et al.85 use an activity-based micro-simulation that generates travel schedules and uses them to estimate EV charging demand profiles across time and space. Additional simulation models incorporate Land Use and Transport Interactions (LUTI) to examine the long-term impacts of policies40.

The behavioral dimensions explicitly represented include:

-

Individual characteristics: Measurable variables about each individual, including age, income, gender, or health status.

-

Latent Characteristics: Individual characteristics—such as perceived costs and benefits of options and policies, attitudes, social norms, values, perceptions, and emotions—play an important role in shaping behavior. These include factors like skepticism, denial, or guilt, as well as perceptions of inequity, moral licensing (e.g., “I am already doing enough”), or overconfidence (e.g., “technology will solve everything”).

-

Implicit Choice Set: Various types of constraints, including resource constraints (e.g., availability of vehicles in a household), regulatory constraints (e.g., some destinations cannot be reached by carbonized modes of transportation, or heating systems with strong GHG emissions are forbidden), and contextual constraints (e.g., extreme weather, floods, earthquakes).

-

Utility Functions: These combine all the above variables to characterize the preferences of individuals.

The behavioral models are typically grounded in random utility theory86, while the simulation environment captures and propagates uncertainty by combining causal models and simulating their distribution across agents and outcomes.

The raw output of the simulation is an empirical distribution of detailed schedules, where all modeled choices made by each (synthetic) individual/household and establishment are explicitly represented.

The use of disaggregate simulation tools poses several challenges:

-

Behavioral assumptions: The underlying assumptions of rational decision-making and stable preferences may not always hold under real-world conditions. The integration of latent variables enables the explicit representation of bounded rationality, social influence, and evolving social norms27,87.

-

Model calibration: Calibrating behavioral models is complex, particularly due to the high dimensionality of parameters and limited observability of preferences88. Bayesian methods offer increased flexibility in fusing diverse data sources and managing uncertainty89,90.

-

Model validation: Validating disaggregate models is equally demanding, often requiring rich, high-resolution behavioral data91. Modern sources such as mobile phone location data92 are proving increasingly valuable in this regard.

-

Computational complexity: Large-scale agent-based simulations and the incorporation of deep uncertainty place significant demands on computational resources. This has motivated the development of efficient formulations and surrogate models to reduce simulation time while preserving model fidelity93,94.

-

Data requirements: Developing detailed behavioral models—whether using simultaneous or sequential structures—requires disaggregate data on individual and household decision-making processes, as well as establishment-level behaviors. These data needs are discussed further in the next subsection.

High-quality behavioral data

Multiple sources of data, including surveys and big data, can and should be used to develop and inform the behavioral models described in our methodological framework. Naturally, each type of data has inherent advantages and limitations. As such, these sources are best used in combination with one another through data fusion approaches.

In the transport field, recall-based travel surveys, which for many years have been the key source of travel and activity behavioral data, are being replaced or supplemented with advanced approaches that combine mobile sensing, the use of contextual data sources, such as transit network, POI and land-use data, and machine learning computational/inference techniques to obtain more accurate, complete, and richer human mobility and activity information (see, for example, ref. 95). When combined with app- or web-based user interfaces that enable participants to view, edit, and verify their travel timelines as well as provide additional details about their trips and activities, the data obtained provides a full storyline of how, when, and why people travel. Such approaches are increasingly being applied in household travel surveys (e.g., ref. 96) and other research programs to provide a rich, contextual understanding of how people interact with their environment, their mobility and activity patterns, and lifestyle choices. These methods can also be used to obtain detailed behavioral data from business establishments providing passenger and freight transport (see, for example, ref. 97 and ref. 98). Without such detailed behavioral data, we could not develop the kinds of models that were described in the previous section.

As with other types of surveys, these data collection methods require recruitment of samples of individuals, households, or business establishments to participate. Participants must be willing to have their personal data (e.g., location data) collected. Data privacy regulations, designed to protect personal data, can be complex and strict, posing challenges for data controllers and processors administering the surveys. Due to cost and time constraints, data collection typically involves relatively small samples (at least as compared to big data) and, in the past, has only been done intermittently, every few or several years. In today’s rapidly changing world, longitudinal data collection, which tracks behavioral dynamics and the factors influencing them over time, is also essential for understanding how and why habits and preferences evolve, and some transportation agencies are moving toward developing more continuous data collection programs.

Transportation agencies are also exploring how big data can be used to model travel behavior. Big data comes from a range of sources, including mobile devices and apps, connected vehicles, transit smart cards, smart road sensors, and geo-tagged social media posts (e.g., ref. 99). With its voluminous datasets and longitudinal nature, big data can be invaluable in revealing patterns of behavior across a wide range of domains, especially travel and mobility. The ability to use big data to monitor what people do when conditions change, e.g., during the COVID pandemic, can be extremely informative in modeling behavior (e.g., ref. 100).

However, a deficiency of big data is that it lacks sufficient detail and is missing variables with explanatory power. This lack of context (e.g., ref. 101) can lead to erroneous assumptions when solely using these data for decision-making and policy design. Another aspect of big data’s “thinness” is that, as with all data distributions, it may have a tail with very few observations, e.g., people who use public transit in a car-dependent city. While sampling plans for travel surveys are typically designed with stratification and oversampling to ensure representation, it may not be possible to oversample certain types of observations with big data, for which datasets are automatically generated.

Survey and big data, as described above, are revealed preferences (RP), meaning data derived from observed or reported actual behaviors and only pertaining to existing situations or conditions. To develop and optimize solutions that do not currently exist or to study attributes that are not captured in big data, stated preferences (SP) data are also required. RP data can be leveraged to develop context-specific SP surveys to allow researchers to test consumer reactions to new solutions, scenarios, and policies in a more realistic, informed manner. This combination of revealed and stated preferences ensures that new initiatives are grounded in actual behavior patterns, increasing their likelihood of success. These enriched datasets enable the development of personalized solutions tailored to individual needs and behaviors (e.g., ref. 102). For example, individuals with high price sensitivity to a carbon tax are more likely to adopt public transportation or active mobility solutions. Such personalized treatments are essential to motivating individuals to switch to sustainable solutions (e.g., ref. 103).

Given the strengths and limitations inherent in each type of data, the greatest potential for improving our ability to understand and predict behavior lies in the integration of different types of data in modeling and simulation systems104. For example, big data has the potential to be enriched with context through fusion with mobile sensing-based survey data, and small samples of survey data can be expanded by its integration with big data. It is incumbent upon researchers to develop effective data fusion approaches to take maximum advantage of the wealth of data available to ensure the optimal design of policies and initiatives related to transport decarbonization.

Indicators

The generated schedules can then be used to measure a wide variety of key indicators. By predicting the decisions of each (synthetic) individual in the population, it becomes straightforward to aggregate individual indicators to obtain their population-level counterparts. For instance, emissions can be derived from travel choices and participation in certain activities. Individual well-being is measured by the utility function within the framework, alongside variables such as health status. Costs are directly derived from the expenses associated with each decision related to activity participation and travel.

Optimization

These indicators then feed into the optimization phase, where sophisticated optimization techniques are employed to adjust policies and better achieve desired outcomes. The goal is to reconfigure the policies based on the performance of the indicators to enhance their overall effectiveness. This process often involves multi-objective optimization, where improving one indicator may inadvertently deteriorate another (as illustrated by Fig. 1).

For instance, increasing subsidy levels for electric vehicles could significantly boost their adoption, reducing emissions and contributing to environmental goals. However, this might also lead to increased government expenditure, affecting budget constraints and potentially limiting funds available for other crucial sectors like healthcare or education. Similarly, policies aimed at enhancing individual well-being through increased access to recreational activities might lead to higher emissions due to increased travel.

Balancing these competing objectives requires a careful and strategic approach. The concept of “Pareto optimality” can be employed to identify solutions that offer the best possible trade-offs between conflicting objectives. This concept is grounded in the principle of dominance. A policy P1 is said to dominate a policy P2 if no indicator associated with P1 is worse than the corresponding indicator for P2, and at least one indicator of P1 is strictly better than the corresponding indicator for P2. A policy is considered Pareto optimal if it is not dominated by any feasible solution.

Once policymakers are presented with the set of Pareto optimal solutions, they can evaluate the relative importance of each indicator and make informed decisions that align with broader societal goals. This approach contrasts with single-objective optimization, where the relative importance of each indicator must be established before any analysis, often in an arbitrary and non-transparent manner. Thanks to the multi-objective approach and the a posteriori weighting, the trade-offs are more transparent, allowing for a clearer understanding of the implications of each decision.

Policy measures

Policy measures aimed at reducing carbon emissions encompass strategies such as carbon pricing, subsidies for renewable energy, emission regulations, and infrastructure investments.

For example, implementing a carbon tax to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions is a prevalent policy approach.

In our methodological framework, each measure can affect various factors:

-

The value of variables in the utility function: For instance, a carbon tax increases the monetary cost of several options, altering the utility associated with different choices.

-

The set of constraints individuals face: For example, a policy restricting access to city centers for carbon-emitting transportation modes would influence the selection of destinations for certain activities.

-

Subjective aspects influencing decisions: For instance, a policy that includes transparent communication about the redistribution of carbon tax revenue might alter the public perception of the tax’s equity.

The whole process is iterative and dynamic, continuously refining policies based on real-time data and feedback. By leveraging these techniques, it is possible to create a balanced policy framework that maximizes overall benefits while minimizing negative impacts, ensuring a sustainable and equitable approach to societal development.

To illustrate, consider the implementation of a congestion charge in a city. The policy is first modeled to simulate commuter responses using travel survey data. The indicators monitored might include traffic volumes, emissions levels, public transport usage, and economic impacts on commuters. Optimization could involve adjusting the congestion charge rates and timings based on these indicators to balance traffic reduction with economic fairness. Throughout this process, inputs such as fuel prices, public transport availability, and travel patterns from GPS data are utilized, along with synthetic populations representing different commuter types.

By using this comprehensive framework, policymakers can design, test, implement, and refine decarbonization strategies effectively, ensuring they are both efficient and equitable.

Scientific challenges

The design, implementation, and application of such a framework are particularly challenging. We briefly discuss some of those challenges.

-

Deep Uncertainty: One of the primary methodological challenges in developing decarbonization policies is dealing with deep uncertainty. This refers to situations where the probabilities of future events are unknown, and the possible outcomes are numerous and varied. Traditional scenario planning, which involves creating a limited set of detailed scenarios, may not be sufficient to capture the full range of uncertainties. Scenario discovery, on the other hand, uses data-driven techniques to identify and explore a broader array of possible futures. For example, rather than just planning for best-case and worst-case scenarios, scenario discovery might reveal a spectrum of outcomes based on different combinations of policy measures, technological advancements, and societal behaviors105,106.

-

Disaggregate Policy-Sensitive Models: Another critical issue is the development of disaggregate policy-sensitive models that can accurately capture the causality of human activities. These models focus on individual or household-level behaviors and decisions, providing a granular understanding of how people respond to specific policies. There is a long tradition of such models in travel demand analysis107, where disaggregate choice models108 are used in micro-simulation tools109,110.

-

Multi-Scale Models: The integration of models across multiple scales is critical for a comprehensive understanding of the broader impacts of various policies. Multi-scale models synthesize data and insights from microscopic (individual or household level), mesoscopic (community or regional level), and macroscopic (national or global level) scales111,112. By leveraging these different scales, researchers can perform an in-depth analysis of how local actions accumulate to influence broader trends. For instance, a multi-scale model might combine local traffic data113 with regional air quality models114 and detailed time use data115.

-

Scalability: Scalability poses a significant methodological challenge: how to effectively apply microscopic models on a global scale116. Although microscopic models offer detailed insights, they are often computationally intensive and require vast amounts of data. Scaling these models globally necessitates innovative approaches, such as employing representative samples, leveraging parallel computing, and utilizing machine learning techniques. For instance, scaling an urban transportation model globally might involve selecting representative cities from various regions and extrapolating the results while considering regional differences in behavior and infrastructure.

-

Propagation of uncertainty: The primary role of simulation is to represent the propagation of uncertainty through complex systems. This involves generating empirical realizations of complex random variables, which are often defined on combinatorially intricate state spaces. Advanced techniques, such as variance reduction methods117 and Markov chain Monte Carlo methods118,119, can be particularly effective in this context.

The proposed framework is merely a high-level preliminary concept, and the list of challenges it presents is certainly much longer and more complex than outlined above.

In particular, future work should explore how such behavioral models can be embedded within broader governance frameworks. Rather than treating policies as isolated instruments, there is a need to model coordinated policy packages that align fiscal tools, regulatory mechanisms, and spatial accessibility measures into a cohesive system120. Embedding the agent-based simulation framework within participatory or adaptive governance is an important research avenue.

This research direction requires an interdisciplinary approach, involving collaboration among engineers, economists, computer scientists, psychologists, political scientists, climate experts, and other specialists. The richness of this field ensures it will fill the research agendas of numerous research teams.

Discussion

Addressing the global challenge of climate change demands an approach that integrates technological advancements, policy frameworks, and an in-depth understanding of human behavior. This paper emphasizes that decarbonization cannot be achieved solely through technological innovations but requires behavioral insights to design effective, equitable, and socially acceptable policies. The interplay of individual choices, societal norms, and systemic constraints is crucial in shaping responses to climate actions.

Through interdisciplinary collaboration and the contributions of experts across engineering, economics, psychology, and data science, we have outlined a methodological framework to guide policymakers in designing and implementing decarbonization strategies. This framework incorporates high-quality behavioral data, choice modeling, agent-based simulations, and optimization techniques to predict and evaluate the impacts of various climate actions. By addressing challenges such as deep uncertainty, behavioral heterogeneity, and multi-scale modeling, the framework provides a robust foundation for creating adaptive and effective climate policies.

Ultimately, the path to decarbonization requires integrating technical feasibility with behavioral realism and societal values. By fostering collaboration across disciplines and leveraging innovative methodologies, policymakers can craft strategies that not only achieve carbon neutrality but also enhance societal well-being, equity, and resilience in the face of a changing climate. This integrated approach ensures that the transition to a sustainable future is both effective and inclusive, addressing the diverse needs and challenges of global populations.

Behavioral change does not occur in a vacuum, however. Structural conditions — such as infrastructure design, market incentives, urban planning, and institutional norms — shape both the feasibility and desirability of low-carbon choices. System-level transformations are therefore necessary to remove barriers and create enabling conditions for sustainable mobility. Policies such as investments in public transport, regulations, subsidies, and infrastructure development play a key role, requiring coordinated efforts from governments, industry, and other influential actors.

We also acknowledge that climate change policies cannot be reduced to a binary choice between technological innovation and individual behavioral change. They are embedded in political, economic, and institutional contexts that shape both the demand and supply sides of the transport sector. Structural drivers—such as planning decisions, market incentives, and vested interests—often influence mobility patterns and technology uptake as much as, if not more than, consumer preferences. For example, London’s congestion charging scheme, introduced in 2003, demonstrated how regulatory pricing can substantially reduce traffic volumes and improve air quality while raising questions of public acceptability, distributional fairness, and revenue use52,54. By contrast, the 2018 French gilets jaunes protests65,121 were triggered by a planned fuel tax increase, illustrating how climate measures that overlook equity and rural mobility constraints can provoke political backlash and undermine long-term decarbonization strategies67,122. These cases highlight how the distributive consequences of climate action raise fundamental questions of justice and legitimacy—namely, who pays, who benefits, and who decides66. As emphasized in the broader sustainability transitions literature, climate mitigation should thus be understood not only in terms of efficiency and acceptability, but also as a governance challenge: one that requires aligning actors, coordinating sectors, and building durable political coalitions capable of sustaining long-term investment under shifting economic and electoral conditions123,124.

Another working group at the same symposium125, likewise emphasized that climate responsibility should not be framed as individual blame, but rather as a forward-looking collective obligation. They stressed that behavioral responses cannot be examined in isolation; instead, they must be situated within the political, institutional, and structural contexts that shape people’s capacity to act. From this perspective, sustainable choices depend less on individual willpower than on the social norms, infrastructures, regulatory and legal frameworks, and power relations that together enable or constrain them.

Our focus on the behavioral dimension is therefore not intended to shift responsibility to individuals, but rather to highlight the importance of aligning system-level change with human motivations. Understanding how people respond to evolving opportunities, constraints, and incentives remains crucial for ensuring that policy interventions are not only technically sound but also socially acceptable and politically feasible. The framework described in this paper is designed precisely to support this goal by integrating behavioral data and models into the evaluation and design of decarbonization strategies.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Lempert, R. J., Popper, S. W., Hernandez, C. C. & RAND Corporation. Transportation planning for uncertain times: a practical guide to decision making under deep uncertainty for MPOs https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/64646 (2022).

Lempert, R. et al. Meeting climate, mobility, and equity goals in transportation planning under wide-ranging scenarios. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 86, 311–323 (2020).

Tang, M. et al. Urban land use optimization prediction considering carbon neutral development goals: a case study of Taihu Bay Core area in China. Carbon Balance Manag. 19, 39 (2024).

Woody, M., Keoleian, G. A. & Vaishnav, P. Decarbonization potential of electrifying 50% of U.S. light-duty vehicle sales by 2030. Nat. Commun. 14, 7077 (2023).

Deweerdt, T. & Fabre, A. The role of land use planning in urban transport to mitigate climate change: a literature review. Adv. Environ. Eng. Res. 03, 033 (2022).

Fosgerau, M., Łukawska, M., Paulsen, M. & Rasmussen, T. K. Bikeability and the induced demand for cycling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2220515120 (2023).

Blackhurst, M. et al. Marginal abatement costs for greenhouse gas emissions in the United States using an energy systems approach. Environ. Res. Energy 2, 015012 (2025).

de Palma, A., Motamedi, K., Picard, N. & Waddell, P. Accessibility and environmental quality: inequality in the Paris housing market http://hdl.handle.net/10077/5950 (2007).

Kaya, Y. & Yokobori, K. Environment, Energy, and Economy: Strategies for Sustainability (United Nations University Press, Tokyo, Japan, 1997).

Klinich, K. D. et al. U.S. vehicle occupancy trends relevant to future automated vehicles and mobility services. Traffic Inj. Prev. 22, S116–S121 (2021).

Lowe, W. U. A. & Piantanakulchai, M. Investigation of behavioral influences of carpool adoption for educational trips –a case study of Thammasat University, Thailand. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 12, 100970 (2023).

Leroutier, M. & Quirion, P. Tackling car emissions in urban areas: Shift, avoid, improve. Ecol. Econ. 213, 107951 (2023).

Grubler, A. et al. A low energy demand scenario for meeting the 1.5 °C target and sustainable development goals without negative emission technologies. Nat. Energy 3, 515–527 (2018).

Creutzig, F. et al. Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 260–263 (2018).

McCollum, D. & Yang, C. Achieving deep reductions in US transport greenhouse gas emissions: scenario analysis and policy implications. Energy Policy 37, 5580–5596 (2009).

Girod, B., van Vuuren, D. P. & Hertwich, E. G. Global climate targets and future consumption level: an evaluation of the required GHG intensity. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 014016 (2013).

Sharmina, M. et al. Decarbonising the critical sectors of aviation, shipping, road freight and industry to limit warming to 1.5–2 °C. Clim. Policy 21, 455–474 (2021).

Steg, L. & Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 29, 309–317 (2009).