Abstract

Multi-procedure robotic assembly requires robots to sequentially assemble components, yet traditional programming is labor-intensive and end-to-end learning methods struggle with vast task spaces. This paper introduces a one-shot learning from demonstration (LfD) approach that leverages third-person visual observations to reduce human intervention and improve adaptability. First, an object-centric representation is proposed to preprocess demonstrations of human assembly tasks via RGB-D camera. Then, a kinetic energy-based changepoint detection algorithm automatically segments procedures, enhancing the robot’s understanding of human intent. Third, a demo-trajectory adaptation-enhanced dynamical movement primitive (DA-DMP) method is proposed to improve the efficiency and generalization of motion skills. The integrated system uses visual feedback for closed-loop reproduction of multi-procedure assembly skills, validated on a real-world robotic assembly platform. Results show accurate sequence learning from a single demonstration, efficient motion planning, and a 93.3% success rate. It contributes to trustworthy and efficient human–machine symbiotic manufacturing systems, aligning with human-centered automation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of Industry 5.0’s human-centric manufacturing paradigm, industrial robots are increasingly required to possess more intuitive and user-friendly programming capabilities. This evolution enables robots to adapt agilely and efficiently to ever-changing and complex work environments, facilitating seamless human–robot collaboration without hindering productivity1,2,3. Assembly is one of the primary processes in the manufacturing industry, accounting for ~50% of total time and 30% of the total cost4. In the actual assembly process, a specific series of manipulations (e.g., picking and placing operations of particular parts) needs to be performed in a specific order, reflecting the long-horizon and multi-procedure characteristics of assembly tasks. To enable robots to complete such long-horizon assembly tasks, the key is making a sequence of decisions under given task conditions, deciding which part to pick and where to place it. Subsequently, picking the selected part in an unstructured environment with non-fixed poses and transferring it to the desired location is the next challenge when executing a particular decision. To tackle such tasks, manual programming with explicitly defined pre-and post-conditions could be an explainable and reliable solution. However, the performance of such explicit programming relies heavily on expert experience and carefully designed events.

With the recent advancements in AI, end-to-end robot learning5 has been investigated as a complementary method to manual programming to reduce human programming workload by endowing robots with the autonomy to learn specific skills6,7. However, robot learning remains an expensive method today, especially for long-horizon tasks, due to the large volume of data required and the time-consuming training phase8. Moreover, developing safe and reliable interaction mechanisms to avoid hardware damage during robot exploration necessitates expert intervention9.

Bridging the gap between manual programming and end-to-end robot learning, Learning from Demonstration (LfD) is regarded as a compromise approach10,11, which can transfer manipulation skills from human to robot via imitation. A key advantage of LfD is that it can enable subject-matter experts with limited robotics or programming knowledge to develop robot behaviors easily, fostering closer human–robot collaboration by maximizing their complementary skills. According to the categorization in the previous publication12, the paradigm of LfD includes kinesthetic teaching, teleoperation, and passive observation. Kinesthetic teaching13 is an intuitive way to teach robots by manual guidance via physical human–robot interaction with few teacher training requirements, studied in applications like polishing14, pick-and-place tasks15, etc. However, this approach requires specific robot hardware capabilities, such as torque sensors, to sense the physical force exerted by humans. Moreover, the demonstration quality of this approach relies on the user’s dexterity and smoothness, often necessitating post-processing even with experts12. Another teaching paradigm, teleoperation16, involves teaching robots via joystick, GUI, VR controller, etc., and is widely used for remotely demonstrating trajectory learning17, task learning18, grasping19, etc. Compared with kinesthetic teaching, teleoperation requires more training for teachers to become familiar with the remote controller interface. On the other hand, passive observation involves the robot remaining inactive during task demonstration, serving solely as a passive observer typically equipped with cameras or other optical tracking devices20. Passive observation stands out for teaching multi-procedure assembly tasks due to its ease of implementation and minimal training requirements for the demonstrator, who only needs to perform the entire task under the robot’s observation without tedious guidance or remote-control processes. This aligns with the human–machine symbiotic manufacturing paradigm, facilitating natural and efficient human–robot interactions.

This paper proposes a one-shot LfD approach for the long-horizon assembly tasks from third-person visual observation with minimal human intervention, advancing the human–machine symbiotic manufacturing system. First, we use an RGB-D camera to record a human performing the assembly task once as a single demonstration. Based on this, we propose an object-centric representation method that extracts the labels, pixel positions, and 3D poses of individual components in the product assembly, enabling the robot to perceive and understand the environment similarly to a human operator. Second, we introduce a kinetic energy-based automatic procedure segmentation algorithm to identify changepoints in the unsegmented long-horizon demonstration, extracting the procedural chain of the taught assembly task and enhancing the robot’s ability to interpret human intent. Third, we develop a demo-trajectory adaptation-enhanced dynamical movement primitive (DA-DMP) method to imitate task-specific motion skills from the segmented sub-task trajectories, allowing the robot to generalize and adapt the learned skills to new scenarios. By integrating these components, the robot employs visual feedback to achieve closed-loop reproduction of multi-procedure assembly skills, embodying an adaptive and interactive manufacturing system. The proposed method is validated on a physical robot performing a seven-part shaft-gear assembly task.

In robotics, learning from human demonstration (LfD) refers to the program technique that allows end-users to teach robots new skills without manual programming, which is a learning and generalization technique more than recording and playing10. According to the teaching paradigm, LfD can be categorized into kinesthetic teaching, teleoperation, and passive observation12. Kinesthetic teaching is characterized by ease of demonstration but lacks suitability for tasks with high degrees of freedom (DoFs); teleoperation is suitable for tasks with high DoFs but difficult to demonstrate; and passive observation offers ease of demonstration and is ideal for tasks with high DoFs, but may be challenging for mapping the demonstration to robot’s behavior12.

In recent years, considering the various advantages offered by these demonstration methods, many studies have been conducted combining them. Cheng et al.21 proposed a learning task and motion planning framework to solve long-horizon tasks (e.g., grasping a peg and inserting it into a hole) with neural object descriptors (NOD-TAMP). In their work, human teleoperation demonstrations for each procedure (with annotation) and RGB-D observations were collected and used to extract object trajectories via NOD. The proposed TAMP can combine skill segments from multiple demonstrations to maximize effectiveness and adapt to the new task settings. Freymuth et al.22 proposed a versatile skill imitation approach, named VIGOR, to facilitate generalization to novel task configurations using geometric behavioral descriptors (GBD). In this work, the teleoperated trajectories are transformed into GBD, and then a Gaussian mixture model policy is trained to generate versatile behavior trajectories. Rozo et al.23, focusing on e-bike motor assembly tasks, combined visual observation with kinesthetic teaching to learn object-centric skills by task-parametrized hidden semi-Markov models (TP-HSMMs). The learned skills are then reproduced with an online task execution method with Riemannian optimal control. Wang et al.24 proposed a hand-eye action network (HAN) to enable robots to imitate approximately human hand-eye coordination behaviors from teleoperated demonstrations with visual observation, which could improve the generalization of the learned skills in new conditions. As an extended study, Wang et al.25 proposed a long-horizon task hierarchical imitation learning framework called MimicPlay. In their work, the easy-to-record human demonstration videos were used to train the high-level planner to generate the latent plans in the long-horizon tasks, which were executed by the low-level policy learned by a technique similar to HAN. In these publications, the demonstration is a mixture of passive observation with teleoperation or kinesthetic, which relies heavily on human invention or additional training on the input interface for the teachers.

The assembly task involves multiple procedures, making visual passive observation advantageous in identifying the different operations of different parts during the teaching phase compared to the other two methods. In such a scope, Duque et al.26 proposed a trajectory generation method for a multi-part assembly task from visual demonstration, where the 3D trajectories of the human hand during the assembly process were tracked and then used to train a task-parametrized GMM model for planning the robot’s execution trajectories. In their work, the orientation of trajectory was not considered. Liang et al.27 proposed a hierarchical policy network for learning sensorimotor primitives of sequential manipulation tasks from visual demonstrations. In their work, an RGB-D camera was utilized to record a human performing the multi-objects manipulation task multiple times, and the 3D objects’ poses were tracked and used to train a hierarchical policy network to reproduce the manipulation skill. The high-level policy manages the objects of interest for each procedure, and the lower two policies are to decide the robot’s action. As an extended study, Liang et al.28 utilized dynamic graph CNNs (DGCNN) to achieve the category-level manipulation skills imitation, where the objects in demonstration and testing could be different. Hu et al.29 proposed a model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML) framework to teach the robot what to do and what not to do through positive and negative visual demonstrations. In their work, multiple demos were used to train a control policy via task-contrastive MAML. Xiong et al.30 proposed a learning-by-watch (LbW) approach to enable robots to physically imitate manipulating skills by watching human video, in which the human arm is translated into a robotic arm by image-to-image translation network for calculating the reward to train a reinforcement learning policy. These publications typically require an extended training process, which may pose challenges when deploying the learned skills to real robots for task execution. In our work, besides pre-training an object detection network without manual labeling, there is no need for an additional training process when handling the recorded demonstration, making our method easier to deploy into real manufacturing systems.

To improve the demo-efficiency of LfD and reduce the teacher’s effort, many papers on the few-shot imitation technique have been published in recent years that used a small amount of human demonstration to learn the instructed task. Du et al.31 used large-scale offline unlabeled robot execution data to pre-train a state-action embedding dataset and incorporated a few human demonstrations to retrieve similar transitions in the offline dataset for training a behavior cloning policy for a specific task. In their work, the pre-required offline data could be expensive for some robot scenarios. To learn the articulated object manipulating tasks, Fan et al.32 proposed a one-shot affordance learning method, where the demonstration includes the point cloud of the involved articulated object (e.g., dispenser, stapler, furniture, etc.) and the trajectory of the human hand while manipulating the object. Guo33 proposed a learning-from-a-single-human-demonstration method, processing RGBD videos to translate human actions to robot primitives and identifying task-relevant key poses of objects for kitchen tasks, like washing a bowel. Coninck et al.34 proposed a method that learns to grasp an arbitrary object from a single demonstration, where the operator guides the robot to the grasping position of a specific object while recording images from its wrist-mounted camera as the demonstration. The demonstration is then used to train a neural network that can generate grasp quality and angles under different poses of the same object as the demonstration.

In contact-rich tasks, Li et al.35 proposed an information augmentation technique to extract force information from the demonstration to improve the generalization of the learner policy. Wen et al.36 utilized a model-free 3D pose tracker to extract the object-centric, category-level representation from a single third-person visual demonstration for achieving category-level behavior cloning, where the 3D pose tracker provides online visual feedback for closed-loop control in skill reproduction. Although this work involves assembly processes, i.e., battery assembly and gear insertion, multi-procedure assembly tasks are not considered. Instead of solely using visual demonstration, Ren et al.37 combined kinesthetic teaching with visual observation of a single demonstration to teach the robot for category-level deformable 3D object manipulation tasks, including wearing-caps and hanging-caps tasks. This work mainly involved the imitation of object grasping poses and did not consider the impact of grasping uncertainty on the post-grasp execution trajectory, that is, the robot executes in an open loop after grasping. Vitiello et al.38 proposed a one-shot imitation learning method to transfer the robot’s end-effector trajectory in demonstration into a new scene where the object is in a novel pose estimated, in which the demonstration requires both teleoperation input and visual observation, and this work did not consider the multi-procedure, long-horizon tasks. Valassakis et al.39 proposed a demonstrate once, imitate immediately method (DOME), which is fundamentally based on an image-conditioned object segmentation network followed by a learned visual servoing network to enable the robot’s end-effector to mimic the same relative pose to the object observed during the demonstration. In DOME, a single demonstration is needed, which requires eye-in-hand visual observation, teleoperation, and kinesthetic teaching.

Existing literature on few-shot imitation learning primarily focuses on scenarios with single procedures or single objects, often neglecting the intricacies of multi-procedure, multi-object challenges. In contrast, our work combines the proposed automatic procedure segmentation algorithm with the DA-DMP method, which can effectively fill this gap. Overall, the key novel contributions of this work are summarized below:

-

(1)

A novel one-shot LfD pipeline for multi-procedure robotic assembly tasks: Our approach integrates object-centric representations, an automatic procedure segmentation algorithm, and a demo-trajectory-adapted DMP enhancement. This allows the robot to acquire task-level and motion-level skills through a single demonstration, significantly streamlining the teaching or programming workflow for multi-procedure robotic assembly and fostering efficient human–robot collaboration.

-

(2)

An object-centric representation method for third-person visual demonstrations in robotic assembly tasks: The proposed method eliminates interference from the background environment and execution subjects in the demonstration sample, focusing solely on the status of task-related objects (product components). This improves adaptability to changes in environmental setups and enhances the robot’s perception capabilities, aligning with the development of embodied AI with integrated sensory systems for interactive manufacturing.

-

(3)

An automatic procedure segmentation algorithm for long-horizon assembly tasks: Given the long-horizon characteristic of multi-procedure assembly tasks, task segmentation is crucial in decomposing unsegmented demonstrations into a sequence of procedures12. The proposed kinetic energy-based algorithm detects changepoints in the demonstration without any feature selection, threshold tuning, or human annotation, enabling the construction of a procedural chain for task-level planning and enhancing human-robot collaboration by understanding human intent.

-

(4)

A demo-trajectory adaptation-enhanced DMP method for efficient motion planning in novel environmental configurations: Compared with the original DMP planning method40, the proposed planner utilizes a trajectory transformation method that considers the specificity of the assembly task, enabling improved execution efficiency. This transformation allows the decoupling of a single sample and reusing it in new scenarios, offering a more sample-efficient LfD method for multi-procedure robotic assembly tasks and contributing to human-centered automation.

Results

In this section, we conducted a set of experiments and a case study to evaluate the proposed method. Firstly, the experimental setup is introduced in detail. Secondarily, the numerical results of the proposed procedure changepoints detection algorithm and DA-DMP learning are presented. Then, the case study on a real robot will also be presented to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method. Lastly, a discussion will be conducted regarding the obtained results.

Experimental setup

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1. The hardware includes a Microsoft Azure Kinect RGB-D camera, a Universal Robots UR5 robot mounted, a Robotiq FT-300s force/torque sensor, and a 2f-140 gripper. All the hardware interfaces are implemented in the robot operating system (ROS). The assembly objects are 3D-printed by the CAD files offered by theSiemens Robot Learning Challenge, labeled as baseplate, gear0, gear1, gear2, gear3, shaft1, and shaft2.

In the demonstration collection, we recorded the color-depth image streaming of the demonstrator executing this assembly task once at a frequency of 30 Hz, recording 1641 frames over a duration of 54.7 s. The collected images were fed into the trained YOLOX detector and the ICG 3D pose tracker, obtaining the proposed object-centric representation. The snapshots of the object-centric representation and the whole trajectories in pixel space and Cartesian space are shown in Fig. 2.

Procedure changepoints detection

After object-centric representation for the collected demonstration, the effectiveness of the proposed procedure changepoints detection algorithm is verified. According to the characteristics of the task scenario, we set the number of objects \(n=7\). And with minimal tuning effort, we simply set the threshold of assembly procedure \(\hat{t}=0.5\), and the mass of objects \({m}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}}=1\). The collected pixel-trajectories \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{1641\times 7\times 2}\) is input to the proposed Algorithm 1. The result is shown in Fig. 3 and Table 1. From the result, the segmented procedure derived from the detected changepoints can effectively cover all procedure intervals, and the proposed algorithm can correctly identify the objects of interest for each assembly procedure.

As for the performance comparison, we compare our method to the following five baselines: (1) Rbeast41, a Bayesian ensemble algorithm for changepoints detection and time series decomposition; (2) PELT42, an algorithm based on the selected cost function, where we carefully selected the mean-variance cost for the best performance; (3) Ruptures43, an algorithm library for off-line changepoints detection, where we carefully selected the radial basis function (RBF)-based method for the best performance; (4) BOCD44, an online Bayesian changepoints detection algorithm; (5) Fastsst45, a singular spectrum transformation (SST)-based detection method, where the threshold of anomaly score of the SST was carefully tuned for the best performance. In the implementation of all baselines, we took the pixel trajectories of the assembly objects as input, and the algorithms’ output is the changepoints in the input trajectories.

With the detected changepoints, we can segment the whole assembly task into procedures. Similar to the semantic segmentation task in the field of computer vision, we use mean intersection over union (mIoU), average accuracy, average precision, and average recall as the evaluation metrics for the involved methods. The result is shown in Table 2. In terms of the mIoU metric, our method achieves the highest score of 0.925, significantly surpassing other methods, which shows its superior overall accuracy of its segmentation result. From the accuracy metric, our method also achieved the best performance, highlighting its advantages in correctly identifying procedure intervals. As for the precision metric, PELT achieves the best performance, but its recall metric is lower, which indicates that it may miss certain procedure intervals. Conversely, our method achieves the highest recall value of 0.980, indicating superior coverage in all procedure segmentations.

Dynamical movement primitive learning

We selected the assembly procedure of shaft2 as the scenario for comparative experiments to validate the superiority of the proposed DA-DMP method over the original DMP method. First, based on the procedure segmentation result, we express the 3D pose trajectory of shaft2 relative to baseplate in the segmented demonstration procedure as 3-dimensional position trajectories and 4-dimensional quaternion orientation trajectories. These 7-dimensional trajectories are then used as the imitation demonstration for a Cartesian DMP. Through careful tuning, we set the number of the basis function \({N}_{{\rm{b}}{\rm{f}}}\) for this Cartesian DMP to 25, aiming to balance imitation efficiency and accuracy. After imitating the demonstration, to test the generalizability of learned movement primitive, as shown in Fig. 4, we align the new goal of the learned DMPs with the target of the demonstration. Then, we rotate the start point of the demonstration around the target’s z-axis in increments of 20° to generate 18 new starts for the learned DMPs. With these configurations, we execute the learned DMPs open loop with the same execution time as the demonstration.

The planned trajectories and their Cartesian components of DMP and the proposed DA-DMP are shown in Fig. 4, where the orientation components are expressed as Euler angles for better readability. Compared with the original DMP method, our method can better preserve the shape of trajectories in the demonstration through the proposed demonstration trajectory adaptation, thereby executing motion behaviors closer to the demonstration in new scene configurations, thus enhancing the generalization capability of DMP. For quantitative analysis and comparison, we computed the lengths of trajectories planned by both methods, as depicted in Fig. 5. It can be observed that, in contrast to the varying lengths exhibited by original DMP across different settings, our proposed method consistently presents shorter lengths in all settings, thus improving the efficiency of DMP.

Case study

To demonstrate the performance of the proposed method, we conduct a total of five case studies on a real robot, Universal Robots UR5, as shown in Fig. 1. For each case study, we randomly initiated the location of the assembly objects, as shown in Fig. 6.

According to the procedure chain and movement primitives learned from demonstration by the proposed procedure changepoints detection and DA-DMP, the robot reproduces the learned assembly skills by the proposed closed-loop execution with visual feedback presented in Algorithm 2. To ensure collision safety during task execution, we continuously monitor the external forces on the robot’s EEF using the FT-300s FT sensor. In our work, the potential collisions can be detected by assessing whether the change in external force exceeds a threshold of 10 N, prompting the robot to perform a post-collision reaction, releasing its gripper, to prevent hardware damage from rigid impacts. The snapshots of the robotic closed-loop execution are shown in Figs. 7–9. It can be found that the proposed method can handle uncertainties arising from object displacement during the grasping action. Furthermore, it incorporates the post-grasp poses of objects into account in the DA-DMP planning, thereby facilitating the success of the assembly task.

The planned trajectories by the proposed DA-DMP in each case study are shown in Fig. 10. It can be shown that the proposed DA-DMP can maintain the trajectory shape consistent with the demonstration to adapt to the changes of the environmental configuration.

The results of all five case studies are summarized in Table 3. In total, the task success rate reaches 93.3%. Specifically, it can be found that most procedures in the case studies were successfully completed, apart from procedure gear2 in Case 2 and procedure gear1 in Case 4. We observed that in these two failed cases, although the gears were successfully inserted into the shafts, their teeth failed to align with those of the other gears. These failures may be attributed to estimation errors in the 3D pose tracker for assembly objects.

Discussion

The findings from the result of the performance comparison can be listed as follows: (1) The proposed one-shot LfD method uses third-person visual passive observation and only requires a single demonstration, which can significantly reduce the workload and teaching difficulty for humans. In the image processing for representing the teaching demo, employing DT-based training data generation for object detection and CAD model-based 3D pose tracker can help eliminate manual labeling requirements, thereby minimizing human intervention. (2) The proposed procedure changepoints detection algorithm, based on general observations of multi-procedure assembly tasks, exhibits superior detection accuracy compared to baseline algorithms, which can accurately segment the demonstration into procedure segments with greater precision. Moreover, the algorithm requires minimal tuning and reflects the intention to minimize human intervention. (3) The proposed DA-DMP, compared to the original DMP, can adapt the single demo-trajectory to different environmental configurations, thereby enhancing the generalization and execution efficiency of learned movement primitives. (4) Using visual feedback to achieve closed-loop execution allows for compensating to some extent for the uncertainty in robot grasping action during assembly tasks in unstructured environments, thereby improving the success rate of skill reproduction.

The limitations of this work can be summarized as follows. The implemented 3D pose tracker relies on CAD models of assembly objects as priors, which is typically feasible for product assembly scenarios since the models of assembly objects are generally accessible during the product design stage. However, in scenarios where obtaining objects’ CAD models is challenging or where assembly objects belong to a certain category lacking fixed specifications, a model-free, category-level pose tracker may be more appropriate. Moreover, although we have designed a post-collision reaction mechanism to ensure safety in physical contact during robot execution, this mechanism may not be robust enough to handle task failures resulting from visual observation errors, as seen in the aforementioned failed cases. Introducing compliant control mechanisms could be a viable alternative to manage the process of physical interaction safely. Additionally, incorporating robot learning from exploration, such as reinforcement learning, to compensate for observation errors may also be a promising approach to address this issue.

Methods

In this section, we will first cover the preliminary aspects of this work, and then we will present details of our proposed framework and its technique as a solution.

Preliminaries

3D space transformation

In this work, the point in the 3D space is defined as\(\,{\boldsymbol{X}}=[{\begin{array}{ccc}x & y & z]\end{array}}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {{\rm{{\mathbb{R}}}}}^{3}\) and the homogeneous form \(\widetilde{{\boldsymbol{X}}}=[{\begin{array}{cccc}x & y & z & 1]\end{array}}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {{\rm{{\mathbb{R}}}}}^{4}\). The RGB-D image \({{\boldsymbol{I}}=[\begin{array}{cc}{{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{{\rm{c}}} & {{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{{\rm{d}}}\end{array}]}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{h\times w\times 4}\) captured from color depth camera with \(h\times w\) resolution is composed by 3-channels color information \({{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{{\rm{c}}}\) and depth information \({{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{{\rm{d}}}\). Assuming that the color image and depth image have already aligned, the pixel location of the image \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}=[{\begin{array}{cc}u & \nu ]\end{array}}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {{\rm{{\mathbb{R}}}}}^{2}\) can access RGB value \({\boldsymbol{c}}={{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{{\rm{c}}}({\boldsymbol{\rho }})\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) and depth value \({d}_{Z}={{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{{\rm{d}}}({\boldsymbol{\rho }})\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{1}\).

The intrinsic parameter of the camera is denoted as

where \({f}_{x}\) and \({f}_{y}\) are the focal length in the x-axis and y-axis direction, respectively; \({c}_{x}\) and \({c}_{y}\) are optical centers in the x-axis and y-axis direction, respectively.

Using the depth information and the intrinsic parameter, point’s location can be obtained by projecting from 3D space pixel to space by

Correspondingly, we use \({\boldsymbol{X}}={{\boldsymbol{\pi }}}^{-1}\left({\boldsymbol{\rho }}\right)\) to denote the project function from pixel space to 3D pixel space:

For the description of the task scenario in our work, we use \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{l}\) and \({\mathcal{C}}\) to denote the assembly components semantically labeled by \(l=\{1,2,\ldots ,| {\mathcal{O}}\}\) and the RGB-D camera, respectively. Plus, \({\mathcal{B}}\), \({\mathcal{E}}\), and \({\boldsymbol{q}}\) are denoted as the robot’s base, end-effector (EEF), and joints, respectively. In the following subsection, we will formulate the problem in robotic assembly tasks and present our proposed framework.

Dynamical movement primitives

Dynamic movement primitives (DMPs) is a method of trajectory control/planning proposed initially by Schaal46, which has been a popular trajectory imitation method in the case of LfD. First, we will briefly introduce the basic principles of DMP. The DMP is based on a point attractive system:

where \({\mathcal{y}}\) is the system state, \(g\) is the control goal, and \({\alpha }_{{\mathcal{y}}}\) and \({\beta }_{{\mathcal{y}}}\) are the gain terms which are familiar to the PD controller gain; \(f\) is the introduced nonlinear force term. In DMP, the \(f\) is modeled as the function of the canonical dynamical system \({\mathcal{x}}\) that has simple dynamics:

For scaling the velocity of the movement primitive, a temporal scaling term \(\tau\) can be added:

where we can slow down the system by setting \(\tau\) between 0 and 1, and speed it up by letting \(\tau\) > 1.

The nonlinear function \(f\) in Eq. (4) therefore can be defined as a function of the canonical dynamical system \(x\):

where \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{0}\) is the system initial state, \({\psi }_{i}=exp(-{h}_{i}{({\mathcal{x}}-{c}_{i})}^{2})\) is the ith Gaussian basis function with center \({c}_{i}\) and variance \({h}_{i}\); \({N}_{{\rm{bf}}}\) and \({\omega }_{i}\) is the number and weighting for the basis function \({\psi }_{i}\), respectively. By this modeling, the nonlinear \(f\) is a set of Gaussians activated as the canonical system of \(x\) to converge to its target. After defining the DMP-based point attractor dynamics, the next is to imitate a desired trajectory \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{{\rm{d}}}\) (i.e., the time series of trajectory from demonstration in our case) to generate trajectory when the goal changes. Given the demo \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{{\rm{d}}}\), we can calculate the force term by:

The solution of the weights of \({f}_{{\rm{d}}}\) can be obtained by locally weighted projection regression47:

where \({\boldsymbol{s}}=\left[\begin{array}{c}{{\mathcal{x}}}_{t0}(g-{{\mathcal{y}}}_{0})\\ \vdots \\ {{\mathcal{x}}}_{t{N}_{\mathrm{bf}}}(g-{{\mathcal{y}}}_{0})\end{array}\right]\), \({{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{i}=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}{\psi }_{i}\left({t}_{0}\right) & \ldots & 0\\ 0 & \ddots & 0\\ 0 & \ldots & {\psi }_{i}\left({t}_{n}\right)\end{array}\right]\). Then, applying this solution, we can obtain a new trajectory \(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{y}}=\{{{\mathcal{y}}}_{0},\ldots ,{{\mathcal{y}}}_{T}\}\) converge a given goal \(g\) by perform an open-loop rollout on the point attractive system Eq. (4).

The proposed framework

In an assembly task, we assume that the task contains at most \(\left|\boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}\right|=n\) assembly parts from a predefined set \(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}=\{{o}_{1},{o}_{2},\ldots ,{o}_{n}\}\) with semantic labels \({\boldsymbol{l}}=\{1,2,\ldots ,n\}\). To complete this assembly task, the robot needs to perform multiple pick-and-place actions sequentially in a specific order according to the assembly relation among the parts. Such a task is typical long-horizon manipulation in robotic applications. To complete a long-horizon manipulation task, making end-to-end planning would be difficult due to the large task space and the long-time scale. Alternatively, we can deploy a task-and-motion planner (TAMP) to solve this problem, where the entire task is divided into procedures with specific actions to complete it, and the planner makes decisions at both levels of task and motion.

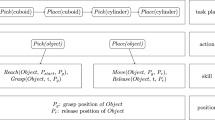

Specifically, for each procedure in an assembly task, the robot needs to make a hierarchical decision before commanding its actuators:

-

(1)

Choosing the target object to be manipulated, denoted as \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}\in \boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}\);

-

(2)

Choosing the object to which \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}\) will reach as a reference, denoted as \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }\in \,\boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}\),\(\,{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }\ne {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}\);

-

(3)

planning a trajectory \({{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}_{{\mathcal{E}}}\) of robot’s EEF (EEF) to make \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}\) reach a specific pose relative to \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }\), which is then executed by robot’s actuators (its joints).

To address the above problem, as shown in Fig. 11, we propose a framework for learning assembly skills from third-person visual demonstration with minimal human intervention. The proposed framework consists of the following phases: demonstration, representation, imitation, and reproduction.

To demonstrate how to assemble parts into a product, the human teacher performs the whole assembly task without any pause. An RGB-D camera \({\mathcal{C}}\) is mounted statically and records color/depth image sequence \({{{\boldsymbol{I}}}^{t}=[\begin{array}{cc}{{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{{\rm{c}}}^{t} & {{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{{\rm{d}}}^{t}\end{array}]}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {\mathcal{D}}\), \(t=\Delta t\cdot \{0,1,\ldots ,\left|I\right|-1\}\) with an interval of \(\Delta t\) from a third-person view as the demonstration sample \({\mathcal{D}}\). In this work, we aim at learning robotic assembly skills with one-shot imitation and minimal human intervention. Thereby, the human only needs to demonstrate the task once, and only a single unsegmented sequence of the recorded RGB-D image frames is needed.

To describe the recorded demonstration in the spatial-temporal domain, we propose an object-centric representation method based on the offline-trained object detector and 3D pose tracker. Through such representation, all the assembly parts \({o}_{l}\) are identified, labeled with \(l\), and located with pixel positions \({{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}^{{o}_{l}}={[\begin{array}{cc}{u}^{{o}_{l}} & {v}^{{o}_{l}}\end{array}]}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\). Sequentially, all parts’ 3D poses relative to the camera \({{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}^{{o}_{l}}\) are also estimated and tracked from the RGB-D frames. In the offline training of the object detector, to ease the human effort in manual annotation, we deployed a fully automatic labeling technique powered by digital twins (DT), which was able to generate a large training dataset of photorealistic and physically reasonable images.

After representing the demonstration, the next step is to learn the manipulation skill by imitating the human teacher. In this paper, we formalize such skill as a hierarchical structure, including a high (task)-level skill that focuses on procedure chaining and a low (motion)-level skill that handles the procedure-specific motion planning. To imitate the task-level skill, we propose an automatic changepoints detection algorithm for segmenting procedures from the unsegmented demonstration. From these segments, the procedure features which contain the semantic label of the manipulated part, \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}\), and the assemble-target part, \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }\), and their relative key pose \({{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }}^{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}}\). Concatenating all the procedures’ features, the procedure chain is then learned from the demonstration. For motion-level imitation, we propose an object-centric dynamical movement primitive (DMP) learning method using a novel trajectory adaptation technique for improving the efficiency in the new conditions of the procedures.

After imitation, the learned policy can be run to execute robotic assembly tasks in the skill-reproduction phase. In this phase, the robot not only receives the same observation as that in the demonstration phase (i.e., RGB-D image frames) but also its proprioception, including the position of its joints, EEF, etc. The execution process follows the steps: (1) inferring the procedure’s features (\({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}\), \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }\), and \({{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }}^{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}}\)) based on the learned procedure chain; (2) planning the object-centric trajectory \({{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}_{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}}\) based on the learned DMPs according to the inferred procedure; (3) planning a EEF’s trajectory \({{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}_{{\mathcal{E}}}\) to follow the planned trajectory using visual feedback based on online object-in-EEF tracking, which is then mapped into joint’s trajectory \({{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}_{{\boldsymbol{q}}}\) as the controller command by operational space controller (OSC).

Object-centric representation from third-person visual demonstration

Given a single, unsegmented visual demonstration for multi-procedure assembly task\(\,{{\boldsymbol{I}}}^{t}{\mathcal{\in }}\,{\mathcal{D}}\), to describe the demonstrated assembly task, we deploy an object-centric representation to extract the spatial–temporal information of the assembly parts, ignoring human-related information. The adoption of such a representation is based on our insight that no matter who performs the task (human or robot), the task-specific objects and their spatial-temporal relationship are constant. To do so, this work integrates an object detector and a 3D pose tracker to obtain the representation for each image frame of \({\mathcal{D}}\) in a 9-dimensional space, which refers to a 1D semantic label \(l\), a 2D pixel location \({{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}^{{o}_{l}}\), and a 3D pose (equal to 6 DoFs) \({{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}^{{o}_{l}}\). To establish such representation, as shown in Fig. 12, we design an offline learning pipeline of the object detector and a 3D pose tracker.

Yolox-based object detector

The object detector we deployed is based on Yolox48, which belongs to the single stage detector with real-time performance. The Yolox network is developed from the Yolo-v349 network by adding techniques, including Decoupled Head, Anchor free, SimOTA, etc. Overall, as shown in Fig. 12, the Yolox network can be divided into three parts: the backbone network, the neck network and the decoupled detection head, where it simultaneously predicts the class of the assembly parts, their pixel position via their bounding box (BBox) coordinates, and the intersection over union (IoU) between prediction and ground truth from an image.

To reduce the massive manual effort of data collection and annotation, we deployed a DT-based dataset generator via physics engine simulation and photorealistic rendering. The Yolox network, therefore, can be offline trained solely on a large amount of synthetic dataset. The proposed data generator is based on Blender, an open-source 3D creation software, and its workflow is shown in Fig. 13. No specific hypotheses or condition assumptions were set for the data generation process, including those related to lighting, cluttered backgrounds, or occlusions.

In the initialization phase, the intrinsic parameters (resolution, focal length, principal point, etc.) and the pose relative to the fixed world of the virtual camera are set to consistent with those of the real physical camera. The max simulation step is set to 60 (equal to 2 s), and the dataset size is set to 3 × 104. In the DT simulation resetting phase, the structural environment (e.g., the workbench) and the objects (including the assembly components, and other distracting objects acting as visual occlusion) are imported from the CAD files. To prevent physically unreasonable embedding of objects, the collision property of the environment and all objects is enabled. To improve the diversity of the dataset, the initial positions and the mass of all objects, as well as the environment gravity and lighting conditions, are all initialized randomly. In the data generation phase, the virtual camera captures the images generated from Blender render engine. The RGB images and the objects’ semantic masks, which can be obtained automatically from Blender’s ID Mask Node, are saved with a frequency of 30 Hz. The obtained objects’ semantic masks are used to compute their bounding boxes by simply finding the maximum and minimum values of the \({uv}\) pixel-axis.

ICG-based object 3D pose tracker

To track objects in 3D space and predicting their 3D poses, we deploy Iterative Corresponding Geometry (ICG)50, which is a state-of-the-art probabilistic tracker that combines region and depth features extracted from object geometry. The workflow of ICG is shown in Fig. 12. Firstly, combing the Yolox network’s output and the depth image, the object’s rough pose is then estimated. The basic idea behind the rough pose estimation is to project the predicted pixel position \({{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}^{{\rm{o}}}\) to 3D space to obtain the object’s translated position \({{\boldsymbol{t}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}^{{\rm{o}}}={[\begin{array}{ccc}x & y & z\end{array}]}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\), computed via Eq. (2); as for the rotational information \({{\boldsymbol{R}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}^{{\rm{o}}}\), we simply initialize the estimated orientation to coincide with the orientation of the workbench desktop.

Once the rough initial pose is given, a multi-modality pose refinement is deployed to continuously track the 3D pose in the subsequent RGB-D image sequences, where the current poses of objects are then updated by using Eq. (3) with the estimated relative pose in current frame to the pose in last frame. The pose refinement includes region modality and depth modality, whose geometry features are off-line extracted from sparse viewpoint of virtual camera.

For off-line geometry feature extraction, similar to Stoiber et al.51, the object’s CAD model is imported to render a large number of RGB-D images via virtual color-depth camera from a spherical-grid-based sparse viewpoint shown in Fig. 14. For every rendered RGB-D image, we randomly sample \({n}_{{\rm{r}}}\) object contour points and \({n}_{{\rm{d}}}\) surface points. These sampled points are then used to computed the norm vector \({{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{{\rm{r}}}={[\begin{array}{cc}{n}_{u} & {n}_{v}\end{array}]}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{2}\), \(||{{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{{\rm{r}}}||=1\) and \({{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{{\rm{d}}}={[\begin{array}{ccc}{n}_{x} & {n}_{y} & {n}_{z}\end{array}]}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\), \(||{{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{{\rm{d}}}||=1\). Note that the norm vectors of the contour points are projected in the pixel space, and those of surface points are in 3D points. With points and vectors, the object-in-camera pose are stored for each viewpoint. Given a rough initial pose, the stored information from the nearest viewpoint is retrieved to calculate the correspondence lines and correspondence points for pose refinement.

For pose refinement, let the estimated relative pose to be a pose variation vector \({\boldsymbol{\phi }}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{6}\). Given the extracted correspondence lines \({\boldsymbol{l}}\) and correspondence points \({\boldsymbol{P}}\), the posterior probability of \({\boldsymbol{\phi }}\) can be written as follows50:

where \({n}_{{\rm{r}}}\) and \({n}_{{\rm{d}}}\) are the number of the selected correspondence lines and correspondence points, respectively; \(p\left({\boldsymbol{\phi }}| {\omega }_{i},{{\boldsymbol{l}}}_{i}\right)\) is the posterior probability over a specific correspondence line \({{\boldsymbol{l}}}_{i}\) and its considered domine \({\omega }_{i}\); \(p\left({\boldsymbol{\phi }}| {{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{i}\right)\) is the posterior probability over a specific correspondence point \({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{i}\).

In the region-based modality, each correspondence line \({{\boldsymbol{l}}}_{i}\) cross the object contour on the point \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}={[\begin{array}{cc}u & v\end{array}]}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {{\rm{{\mathbb{R}}}}}^{2}\). Using the correspondence information, the energy function as the probability of \({\boldsymbol{\phi }}\) can be computed by

where \({\sigma }_{{\rm{r}}}\) is the introduced user-defined standard deviation; \(\sigma\) is the expected pixel-wise standard deviation; \({d}_{{\rm{r}}}({\boldsymbol{\phi }})\) is the line distance from the estimated contour points \({{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}^{{\prime} }\) to the correspondence center \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}\). The line distance is calculated by:

where \({\bar{{\boldsymbol{N}}}}_{{\rm{r}}}={\rm{m}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{x}}(|{n}_{{\rm{u}}}|,|{n}_{{\rm{v}}}|\,)/s\) is unscaled projection of the closest horizontal or vertical image coordinate with the user-defined scale parameter \(s\); \(\Delta r\in {\mathbb{R}}\) is the contour point offset in the pixel location. The estimated points \({{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}^{{\prime} }={\boldsymbol{\pi }}\left({\boldsymbol{X}}\left({\boldsymbol{\phi }}\right)\right)\) is the updated correspondence line center calculated by performing the 3D point transform and projection with pose variation \({\boldsymbol{\phi }}\) and camera intrinsic parameter using and Eq. (2).

In the depth-based modality, each selected surface point \({\boldsymbol{X}}={[\begin{array}{ccc}x & y & z\end{array}]}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {{\rm{{\mathbb{R}}}}}^{3}\) has its correspondence point \({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{i}={[\begin{array}{ccc}x & y & z\end{array}]}^{{\mathsf{T}}}\in {{\rm{{\mathbb{R}}}}}^{3}\). Using the correspondence information, the distance between \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{P}}\) along \({\boldsymbol{N}}\) can be calculated by:

where \({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{i}\left({\boldsymbol{\phi }}\right)\) is the transformed correspondence point using vector \({\boldsymbol{\phi }}\). Then, the probability of \({\boldsymbol{\phi }}\) from depth-based modality can be calculated by

where \({\sigma }_{{\rm{d}}}\) is the user-defined standard deviation scaled by the depth value from depth image \({d}_{Z}={{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{{\rm{d}}}({\boldsymbol{\pi }}({\boldsymbol{P}}))\).

Then, for maximizing the joint probability in Eq. (10), a Newton optimization method with Tikhonov regularization is used to calculate the estimated pose variation vector \(\widehat{{\boldsymbol{\phi }}}\). More details about the optimization procedure can be found in ref. 50. The tracking result of object 3D pose relative to the camera frame is then updated by Eq. (15).

Together with the Yolox detector and ICG tracker, the pixel- and 3D-space trajectories of all assembly objects in human demonstration are obtained. In the following section, the pixel-space trajectories are used for the task-level learning and the 3D-space trajectories are used for the motion-level learning.

Procedure chain extraction based on procedure changepoints detection

Given an unsegmented demonstration based on the previously proposed object-centric representation, breaking down the long-horizon, multi-procedure assembly task into a chain of procedure and then mimicking each procedure based on its characteristics is a more straightforward and deployable method12. To implement it, the changepoints of procedures should be detected as the starting and ending points for segmentations. Here we propose a kinetic energy-based automatic sub-tasks segmentation algorithm. The proposed algorithm is based on the following assumptions about the multi-procedure assembly task:

-

(1)

Each assembly procedure is accompanied by the accumulation of kinetic energy, with the objects of interest (i.e., \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}\) and \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }\)) occupying the dominant portion.

-

(2)

The kinetic energy of each assembly procedure should be maintained above a certain threshold for a period of time (such as greater than 0.5 s).

The first assumption is based on observations of assembly tasks, while the second assumption is derived from observations of the demonstrator’s behavior. Based on these assumptions, the proposed algorithm takes pixel trajectories of objects \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}={\{({u}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{1}},{v}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{1}}),\ldots ,({u}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{n}},{v}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{n}})\}}_{t=0:T}\) as input and outputs the changepoints for each procedure \({\boldsymbol{cp}}=\{({t}_{{\rm{start}},1},{t}_{{\rm{end}},1}),\,\ldots ,({t}_{{\rm{start}},n-1},{t}_{{\rm{end}},n-1})\}\), along with the objects of interest for each procedure \({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}}^{{\prime} }=\left\{\left({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,1},{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,1}\right),\ldots ,\left({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,n-1},{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,n-1}\right)\right\}\), where \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}\) is the target object to manipulate and \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,i}\) is the referenced object reached by \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}^{i}\) in the \(i{\rm{th}}\) procedure. The principle of the proposed algorithm is shown in Fig. 15, where \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{W}}}\) is the total kinetic energy of all objects, calculated by summing the kinetic energy per object \({\boldsymbol{W}}{| }_{t=0:T}={\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{W}^{{o}_{i}}{| }_{t=0:T}\). The object-wise kinetic energy is calculated by

Given a threshold \(\widehat{W}\), the kinetic energy trajectory \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{W}}}{| }_{t=0:T}\) can be binarized, where the interval with a value of 0 represents the stationary period, while 1 represents the active period. Subsequently, we can determine the changepoints of procedures based on the abrupt changes in the binarized trajectory. In this process, the rising edge of the trajectory is considered as the starting point of a procedure \({t}_{{\rm{s}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{t}},i}\), while the falling edge is considered as the ending point of a procedure \({t}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{d}},i}\). This approach enables to effectively identify transitions between different procedures in the assembly process, while trimming away the stationary states in demonstration trajectory. Based on the obtained start and end points, we can calculate the duration of the procedure. Considering the duration threshold on procedure \(\hat{t}\) as mentioned in the second assumption, we can determine if this segmentation meets this constraint. If not, the threshold \(\hat{W}\) can be further progressively adjusted until the condition is satisfied. Once the above conditions are met, we can identify the two objects with the highest accumulated kinetic energy within each recognized procedure interval. The one with the highest accumulation is labeled as \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}\), and the second-highest is labeled as \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }\). The above processes can be summarized in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1

Procedure changepoints detection algorithm for multi-procedure assembly task.

Parameter: Threshold for duration of assembly procedure \(\hat{t}\); a set of objects \(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}=\{{o}_{1},\ldots ,{o}_{n}\}\) and their mass \({\boldsymbol{m}}=\{{m}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{1}},\ldots ,{m}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{n}}\}\)

Input: Pixel trajectories of assembly objects \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}={\{({u}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{1}},{v}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{1}}),\ldots ,({u}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{n}},{v}^{{{\rm{o}}}_{n}})\}}_{t=0:T}\)

Output: Changepoints per assembly procedure \({\boldsymbol{c}}{\boldsymbol{p}}=\{({t}_{{\rm{s}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{t}},1},{t}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{d}},1}),\,\ldots ,({t}_{{\rm{s}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{t}},n-1},{t}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{d}},n-1})\}\)

Objects of interest per assembly procedure \({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}}^{{\prime} }=\left\{\left({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,1},{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,1}\right),\ldots ,\left({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,n-1},{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,n-1}\right)\right\}\)

Declare: \({\boldsymbol{cp}}\leftarrow []\); \({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}}^{{\prime} }\leftarrow []\); kinetic energy threshold \(\hat{W}=0\)

1. Calculate kinetic energy per object \({\boldsymbol{W}}={\left\{{W}^{{o}_{1}},\ldots ,{W}^{{o}_{n}}\right\}}_{t=0:T}\) using \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}\) by Eq. (16)

2. Calculate total kinetic energy \(\overline{{\bf{W}}}{|}_{t=0:T}={\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{W}^{{o}_{i}}{|}_{t=0:T}\)

3. for \(i\in \{1,\ldots ,\frac{\max \left(\bar{{\boldsymbol{W}}}\right)}{\min \left(\bar{{\boldsymbol{W}}}\right)}\}\) do

4. \(\hat{W}=i\cdot \min \left(\bar{{\boldsymbol{W}}}\right)\)

5. \({\boldsymbol{cp}}\leftarrow {\text{find}}{\_}{\text{changepoints}}({\bar{\boldsymbol{W}}},\widehat{W})\)

6. for \(j=1{;j}\, < \,n-1{;j}\leftarrow j+1\) do

7. if \({t}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{d}},j}-{t}_{{\rm{s}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{t}},j}\, < \hat{t}\) then

8. Reject the found changepoints and Continue to Line 3

9. end if

10. \({{\mathscr{O}}}_{+,j}\leftarrow \arg \mathop{max}\limits_{o\in \boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}}({\sum }_{t={t}_{{\rm{s}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{t}},j}}^{t={t}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{d}},j}}{{\boldsymbol{W}}|}_{t})\)

11. \({{\mathscr{O}}}_{\perp ,j}\leftarrow \arg \mathop{max}\limits_{o\in \boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}\backslash {{\mathscr{O}}}_{+,j}}({\sum }_{t={t}_{\mathrm{start},j}}^{t={t}_{\mathrm{end},j}}{{\boldsymbol{W}}|}_{t})\)

12. end for

13. \({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{O}}}^{{\prime} }\leftarrow \left\{\left({{\mathscr{O}}}_{+,1},{{\mathscr{O}}}_{\perp ,1}\right),\ldots ,\left({{\mathscr{O}}}_{+,n-1},{{\mathscr{O}}}_{\perp ,n-1}\right)\right\}\)

14. break for

15. end for

16. Return \({\boldsymbol{cp}}\), \({{\mathscr{O}}}^{+}\)

After identifying all the changepoints, the undivided demonstration trajectory is segmented into a certain number of procedures, thus extracting the demonstrated procedure chain. To extract procedure-specific feature for further motion-level planning, the 3D pose of tool relative to target at the end of the procedure, \({{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp }}^{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{+}}{| }_{t={t}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{d}}}}\,\), is retrieved from demo representation and stored as the goal pose during robot execution.

Demonstration trajectory adaptation-enhanced DMP learning

In assembly task, the trajectories of objects and the robot’s EEF are expressed in the Cartesian space, so the Cartesian version of DMP is used in our work. The Cartesian DMP handles orientation and position separately, where the orientation is represented as quaternion \({\boldsymbol{q}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{4}\) transformed from the rotation matrix \({\boldsymbol{R}}\), and the position vector is \({\boldsymbol{t}}={[\begin{array}{ccc}x & y & z\end{array}]}^{\top }\). Thereby, the state space of our Cartesian DMP has 7 dimensions. The position components are handled in the same way as the basic DMP presented in the last section. To make the dynamics system Eq. (11) work in the case of quaternion components, \({\mathcal{y}}\) is given as a quaternion, \(g-{\mathcal{y}}\) is given as the quaternion difference (expressed as rotation vector), and \(\dot{{\mathcal{y}}}\) and \(\ddot{{\mathcal{y}}}\) are given as the angular velocity and acceleration, respectively. More technical details about quaternion DMP can be found in ref. 52.

To align with the proposed object-centric representation for demonstration, we express the Cartesian trajectory in the object’s coordinate system, rather than that of robot’s EEF. That is: given the procedure features in ith procedure obtained from the algorithm presented in the section “Procedure chain extraction based on procedure changepoints detection”, the trajectories of the objects of interest, \({\,\left.{{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}^{o}\right|}_{{t}_{{\rm{start}},i}:\,{t}_{{\rm{end}},i}},o\in \left\{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i},{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,i}\right\}\), are retrieved from demonstration using the 3D pose tracker presented in the section “ICG-based object 3D pose tracker”. After the coordinate transformation, the object-centric trajectory is used as demonstration for Cartesian DMP imitation, i.e., \({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{y}}}^{{\mathcal{D}}}{\boldsymbol{\leftarrow }}{{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,i}}^{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}}{|}_{{t}_{\mathrm{start},i}:\,{t}_{\mathrm{end},i}}\)

Given the retrieved single demonstration, as shown in Fig. 16a, the original DMP, however, cannot handle the shape trajectory consistence well when a new start and goal are configured in the case of Cartesian space, which might reduce the efficiency of task execution and the generalization of the learned movement primitives. To address this issue, we propose a demonstration adaptation-enhanced DMP, named DA-DMP to transform the given trajectory to the new task configuration, whose principle is shown in Fig. 16b.

Assuming that the assembly direction is along with the Z axis, namely, along with the norm vector \({{\boldsymbol{n}}}_{z}={[\begin{array}{ccc}0 & 0 & 1\end{array}]}^{\top }{\rm{f}}\), with regard to the configuration in the demonstration (denoted as \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{0}\) and \(g\)) and the new task scenario (denoted as \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{0}^{{\prime} }\) and \({g}^{{\prime} }\)), we can first calculate the unit vectors of their XY-plane projections, \({{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{z}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{z}^{{\prime} }\), respectively by

Then, the rotation angle \({\phi }_{{rz}}\) and its rotation matrix \({{\boldsymbol{R}}}_{z}\left({\phi }_{{rz}}\right)\) that brings \({{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{z}\) to \({{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{z}^{{\prime} }\) can be calculated by

where the Z-axis rotation angle \({\phi }_{{rz}}=\arccos \left({{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{z}\cdot {{\boldsymbol{N}}}_{{\boldsymbol{z}}}^{{\prime} }\right)\). Applying \({{\boldsymbol{R}}}_{z}\left({\phi }_{{rz}}\right)\) to the demo trajectory \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{{\rm{d}}}\) by Eq. (19), the adapted trajectory to be imitated \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{{\rm{d}}}\) can be obtained. Thereby, regarding the new configuration of \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{0}^{{\prime} }\) and \({g}^{{\prime} }\), the adapted trajectory generated from the DMP of \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{{\rm{d}}}\) can be obtained by Eq. (20).

Closed-loop execution based on visual feedback

For reproduction the imitated skills from demonstration, we deploy the same object-centric representation during robot execution. In the process of robot assembly, the robot’s gripper to pick up parts and place them in specific positions. Typically, the robot’s grasping action lacks feedback mechanism, meaning that the gripper’s actions do not adjust with changes in the grasping state (often limited only by the grasping force). This results in uncertainties (e.g., object displacement) during the grasping action, leading to errors in the subsequent placing action of the object. To compensate for this uncertainty, we introduce visual feedback to incorporate the post-grasping pose of the object into the subsequent motion planning. The high-level procedure can be summarized in Algorithm 2.

Algorithm 2

Closed-loop execution for assembly task based on visual feedback

1. for \(i=\{1,\ldots ,n-1\}\) do

2. Take RGB-D image to recognize the 3D pose of \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}\);

3. Move robot to grasp \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}\);

4. Take RGB-D image to recognize the 3D poses of \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}\) and \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,i}\);

5. Make motion planning via the proposed DMP for object-centric trajectory \({{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}_{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,i}}^{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}}\);

6. Map the planned trajectory into EEF’s trajectory \({{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}_{{\mathcal{B}}}^{{\mathcal{E}}}\) and feed to the robot to execute.

Based on the procedure chain learned through task-level imitation as introduced in Section 3.4, the robot sequentially executes the procedures within the procedure chain.

For the execution process of the i-th procedure, the robot first recognizes the 3D pose of the object of interest \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}\). Subsequently, it moves to the grasping pose of \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}\), and then closes its gripper to grasp the assembly part. To determine the grasping pose of object, we utilize HandTailor53 to estimate the demonstrator’s hand pose at the detected start point \({t}_{{start},i}\) of each procedure, as shown in Fig. 17. Based on the estimation, we calculate the midpoint between hand’s joints 4 and 8 as the grasping point, which is then transformed to 3D space in the object’s frame using Eq. (3) to obtain the position for the grasping pose of the object, and we adopt the same orientation as that of the object. These grasping poses are processed and restored offline, thus during execution, the robot only needs to retrieve the corresponding grasping pose for each procedure, thereby improving efficiency.

After grasping the assembly part \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}\), the robot recognizes the 3D relative pose between the objects of interest as the start state of the proposed DMP planner, \({{\mathcal{y}}}_{0}^{{\prime} }={{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,i}}^{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}}\). Setting the goal as the pose at the end of the procedure in the demonstration, the proposed DMP planner will generate the object-centric trajectory \({{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}_{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{\perp ,i}}^{{{\mathcal{O}}}_{+,i}}\). By Eq. (21), the planned trajectory can be mapped into EEF’s trajectory \({{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}_{{\mathcal{B}}}^{{\mathcal{E}}}\), where the camera-in-base pose \({{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{\mathcal{B}}}^{{\mathcal{C}}}\) is a static transform obtained from hand-eye calibration, the objects-in-camera pose \({{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{\mathcal{C}}}^{o}\) is estimated from the tracker as introduced in Section 3.3.2, and the hand-in-base pose \({{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{{\mathcal{B}}\,}^{{\mathcal{E}}}\) is from the robot’s forward kinematics. After that, we use MoveIt! as the robot’s operational space controller to transform the planned EEF’s trajectory into joints’ trajectory \({{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}_{{\boldsymbol{q}}}\) which is then send to robot controller to execute.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

The code may be provided upon request.

References

Zafar, M. H., Langås, E. F. & Sanfilippo, F. Exploring the synergies between collaborative robotics, digital twins, augmentation, and industry 5.0 for smart manufacturing: a state-of-the-art review. Robot. Comput. -Integr. Manuf. 89, 102769 (2024).

Liu, D. et al. A skeleton-based assembly action recognition method with feature fusion for human–robot collaborative assembly. J. Manuf. Syst. 76, 553–566 (2024).

Gkournelos, C., Konstantinou, C. & Makris, S. An LLM-based approach for enabling seamless human–robot collaboration in assembly. CIRP Ann. 73, 9–12 (2024).

Jiang, J., Huang, Z., Bi, Z., Ma, X. & Yu, G. State-of-the-art control strategies for robotic PiH assembly. Robot. Comput. -Integr. Manuf. 65, 101894 (2020).

Liu, Z., Liu, Q., Xu, W., Wang, L. & Zhou, Z. Robot learning towards smart robotic manufacturing: a review. Robot. Comput. -Integr. Manuf. 77, 102360 (2022).

Zhang, X., Yi, D., Behdad, S. & Saxena, S. Unsupervised human activity recognition learning for disassembly tasks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 20, 785–794 (2023).

Aristeidou, C., Dimitropoulos, N. & Michalos, G. Generative AI and neural networks towards advanced robot cognition. CIRP Ann. 73, 21–24 (2024).

Ibarz, J. et al. How to train your robot with deep reinforcement learning: lessons we have learned. Int. J. Robot. Res. 40, 698–721 (2021).

Brunke, L. et al. Safe learning in robotics: from learning-based control to safe reinforcement learning. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 5, 411–444 (2022).

Billard, A. G., Calinon, S. & Dillmann, R. Learning from humans. In: Siciliano, B., Khatib, O. (eds) Springer Handb. Robot. Springer Handbooks. Springer, Cham 1995–2014 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32552-1_74 (2016).

Hernandez Moreno, V., Jansing, S., Polikarpov, M., Carmichael, M. G. & Deuse, J. Obstacles and opportunities for learning from demonstration in practical industrial assembly: a systematic literature review. Robot. Comput. -Integr. Manuf. 86, 102658 (2024).

Ravichandar, H., Polydoros, A. S., Chernova, S. & Billard, A. Recent advances in robot learning from demonstration. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 3, 297–330 (2020).

Akgun, B., Cakmak, M., Yoo, J. W. & Thomaz, A. L. Trajectories and keyframes for kinesthetic teaching: a human–robot interaction perspective. In Proc. seventh annual ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human–Robot Interaction 391–398 (ACM, 2012).

Wang, Y. et al. AL-ProMP: Force-relevant skills learning and generalization method for robotic polishing. Robot. Comput. -Integr. Manuf. 82, 102538 (2023).

Wang, Y. Q., Hu, Y. D., Zaatari, S. E., Li, W. D. & Zhou, Y. Optimised learning from demonstrations for collaborative robots. Robot. Comput. -Integr. Manuf. 71, 102169 (2021).

Liang, K. et al. A robot learning from demonstration method based on neural network and teleoperation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 49, 1659–1672 (2024).

Ge, D. et al. Learning compliant dynamical system from human demonstrations for stable force control in unknown environments. Robot. Comput. -Integr. Manuf. 86, 102669 (2024).

Scherzinger, S., Roennau, A. & Dillmann, R. Contact skill imitation learning for robot-independent assembly programming. In 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 4309–4316 (IEEE, 2019).

Whitney, D., Rosen, E., Phillips, E., Konidaris, G. & Tellex, S. Comparing robot grasping teleoperation across desktop and virtual reality with ROS reality. In Robotics Research: the 18th International Symposium (ISRR) 335–350 (Springer, 2019).

Li, J. et al. Okami: Teaching humanoid robots manipulation skills through single video imitation. In Proc. 8th Annual Conference on Robot Learning (2024).

Cheng, S., Garrett, C., Mandlekar, A. & Xu, D. NOD-TAMP: multi-step manipulation planning with neural object descriptors. In CoRL 2023 Workshop on Learning Effective Abstractions for Planning (LEAP). https://openreview.net/forum?id=DK7TbAS0Wz (2023).

Freymuth, N., Schreiber, N., Becker, P., Taranovic, A. & Neumann, G. Inferring versatile behavior from demonstrations by matching geometric descriptors. In Proc. 6th Conference on Robot Learning 1379–1389 (PMLR, 2022).

Rozo, L. et al. The e-Bike motor assembly: towards advanced robotic manipulation for flexible manufacturing. Robot. Comput. -Integr. Manuf. 85, 102637 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Generalization through hand-eye coordination: an action space for learning spatially-invariant visuomotor control. In 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 8913–8920 (IEEE, 2021).

Wang, C. et al. MimicPlay: long-horizon imitation learning by watching human play. In Proc. 7th Conference on Robot Learning 201–221 (PMLR, 2023).

Duque, D. A., Prieto, F. A. & Hoyos, J. G. Trajectory generation for robotic assembly operations using learning by demonstration. Robot. Comput. -Integr. Manuf. 57, 292–302 (2019).

Liang, J., Wen, B., Bekris, K. & Boularias, A. Learning sensorimotor primitives of sequential manipulation tasks from visual demonstrations. In 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 8591–8597 (IEEE, 2022).

Liang, J. & Boularias, A. Learning category-level manipulation tasks from point clouds with dynamic graph CNNs. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 1807–1813 (IEEE, 2023).

Hu, Z. et al. Learning from visual demonstrations via replayed task-contrastive model-agnostic meta-learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 32, 8756–8767 (2022).

Xiong, H. et al. Learning by watching: physical imitation of manipulation skills from human videos. In 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 7827–7834 (IEEE, 2021).

Du, M., Nair, S., Sadigh, D. & Finn, C. Behavior retrieval: few-shot imitation learning by querying unlabeled datasets. In Robotics: Science and Systems (2023).

Fan, R., Wang, T., Hirano, M. & Yamakawa, Y. One-shot affordance learning (OSAL): learning to manipulate articulated objects by observing once. In 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 2955–2962 (IEEE, 2023).

Guo, D. Learning multi-step manipulation tasks from a single human demonstration. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.15346 (2023).

Coninck, E. D., Verbelen, T., Molle, P. V., Simoens, P. & IDLab, B. D. Learning to grasp arbitrary household objects from a single demonstration. In 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 2372–2377 (IEEE, 2019).

Li, X., Baurn, M. & Brock, O. Augmentation enables one-shot generalization in learning from demonstration for contact-rich manipulation. In 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 3656–3663 (IEEE, 2023).

Wen, B., Lian, W., Bekris, K. & Schaal, S. You only demonstrate once: Category-level manipulation from single visual demonstration. In 18th Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS) (MIT Press Journals, 2022).

Ren, Y., Chen, R. & Cong, Y. Autonomous manipulation learning for similar deformable objects via only one demonstration. in Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 17069–17078 (IEEE, 2023).

Vitiello, P., Dreczkowski, K. & Johns, E. One-shot imitation learning: a pose estimation perspective. In Proc. 7th Conference on Robot Learning 943–970 (PMLR, 2023).

Valassakis, E., Papagiannis, G., Di Palo, N. & Johns, E. Demonstrate once, imitate immediately (DOME): learning visual servoing for one-shot imitation learning. In 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 8614–8621 (IEEE, 2022).

Ijspeert, A. J., Nakanishi, J., Hoffmann, H., Pastor, P. & Schaal, S. Dynamical movement primitives: learning attractor models for motor behaviors. Neural Comput. 25, 328–373 (2013).

Zhao, K. et al. Detecting change-point, trend, and seasonality in satellite time series data to track abrupt changes and nonlinear dynamics: a Bayesian ensemble algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 232, 111181 (2019).

Killick, R., Fearnhead, P. & Eckley, I. A. Optimal detection of changepoints with a linear computational cost. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 107, 1590–1598 (2012).

Truong, C., Oudre, L. & Vayatis, N. Selective review of offline change point detection methods. Signal Process. 167, 107299 (2020).

Niekum, S., Osentoski, S., Atkeson, C. G. & Barto, A. G. Online Bayesian changepoint detection for articulated motion models. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 1468–1475 (IEEE, 2015).

Ide, T. & Sugiyama, M. Anomaly Detection and Change Detection. Machine Learning Professional Series (Kodansha Ltd, 2015).

Schaal, S. Dynamic movement primitives-a framework for motor control in humans and humanoid robotics. In Adaptive Motion of Animals and Machines 261–280 (Springer, 2006).

Schaal, S., Atkeson, C. G. & Vijayakumar, S. Scalable techniques from nonparametric statistics for real time robot learning. Appl. Intell. 17, 49–60 (2002).

Ge, Z., Liu, S., Wang, F., Li, Z. & Sun, J. YOLOX: exceeding YOLO series in 2021. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2107.08430 (2021).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: an incremental improvement. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1804.02767 (2018).

Stoiber, M., Sundermeyer, M. & Triebel, R. Iterative corresponding geometry: Fusing region and depth for highly efficient 3d tracking of textureless objects. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 6855–6865 (2022).

Stoiber, M., Pfanne, M., Strobl, K. H., Triebel, R. & Albu-Schäffer, A. SRT3D: a sparse region-based 3d object tracking approach for the real world. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 130, 1008–1030 (2022).

Ude, A., Nemec, B., Petrić, T. & Morimoto, J. Orientation in cartesian space dynamic movement primitives. In 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 2997–3004 (IEEE, 2014).

Lv, J. et al. HandTailor: towards high-precision monocular 3d hand recovery. in Proc. 32nd British Machine Vision Conference (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 92367108), Hubei Provincial Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023BAB012), Wuhan East Lake High-tech Development Zone’s Leading the Charge with Open Competition Project (Grant No. 2023KJB215), and the Young Topnotch Talent Cultivation Program of Hubei Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Quan Liu: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, Supervision. Zhenrui Ji: Methodology, data curation, software, writing—original draft. Wenjun Xu: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review & editing, supervision. Zhihao Liu: Investigation, writing—review and editing. Lihui Wang: Writing—review and editing and Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Q., Ji, Z., Xu, W. et al. One-shot learning-driven autonomous robotic assembly via human-robot symbiotic interaction. npj Adv. Manuf. 2, 22 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44334-025-00030-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44334-025-00030-3