Abstract

Molecular clustering of perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) is chain-length dependent, yet its biological consequences in crops remain unclear. The plants were hydroponically exposed to PFCA clusters at concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 μmol/L for 14 days, with untreated controls. To elucidate the underlying mechanisms, they were analyzed using atomic force microscopy, molecular dynamics simulations, and integrated omics approaches to examine how PFCA clustering affects bioaccumulation and metabolic disruption. The results indicate that longer-chain PFCA (C10) formed larger, more stable clusters (122–194 nm) than shorter chain (C4, 35–95 nm). C10 clusters exhibited 5.5-fold higher root accumulation but 50% reduced shoot translocation compared to C4 clusters. Metabolomics revealed 664 significantly altered metabolites for C10 versus 545 for C4, predominantly downregulated. Further proteomic evidence showed that C10 exposure induced a greater number of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) compared to C4, indicating broader protein-level disruption and more profound impairment of mitochondrial function. Most critically, C10 clusters severely impaired the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, reducing intermediates by up to 48% and downregulating associated enzymes. Molecular docking confirmed strong binding between PFCA clusters and metabolic enzymes (−6.3 to −6.4 kcal·mol⁻¹). These findings indicate that larger PFCA clusters are associated with greater phytotoxicity compared to smaller clusters, suggesting important implications for crop safety. Results highlight urgent needs for cluster-aware monitoring strategies and revised risk assessment frameworks accounting for aggregation phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) possess extraordinary chemical and thermal stability, contributing to their widespread distribution in various environmental media. Advanced mass spectrometry techniques have consistently detected PFAS in rainwater1,2, soil3, surface water, and groundwater4,5, frequently at concentrations exceeding safety thresholds established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the European Union (EU), for instance, the US EPA has set interim lifetime drinking water health advisories for PFOA and PFOS at 4 and 20 pg/L, respectively, while the EU annual average environmental quality standard (AA-EQS) for PFOS in inland surface waters is 0.65 ng/L6,7. Their resistance to degradation and high persistence present major challenges for remediation and exposure control, raising critical concerns about long-term ecotoxicity and human health risks8,9,10,11,12.

Recent studies have shown that organic contaminants can self-aggregate into molecular clusters, a phenomenon largely overlooked in toxicological evaluations. Pronounced phenanthrene clusters were first observed along intermediate polymeric lipid-rich layers in plant leaves using two-photon laser confocal scanning microscopy13,14, while single-molecule fluorescence microscopy captured the formation and dynamic behavior of perylene nanoclusters in aqueous environments at concentrations as low as 1 μM15,16. Molecular dynamics simulations further demonstrated that clustering of phthalate esters intensifies with increasing carbon chain length17. These findings underscore that many environmental contaminants occur as molecular clusters18, lowering the bioavailable (monomeric) fraction and altering fate/transport, thereby biasing monomer-based ecological risk estimates. Due to the structural features of PFAS—such as the low polarizability and weak dispersion forces of fluorine atoms, which promote strong F-F interactions (6.3–16.7 kJ·mol−1)19,20, as well as their tendency for hydrophobic interactions and interchain entanglement21,22, PFAS are primed for spontaneous cluster formation. However, most studies on PFAS environmental fate and toxicity have considered them only as monomers, overlooking the potential effects of clustering. Our recent study showed that smaller molecular clusters of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) exert greater toxicity on microbes than larger clusters, causing metabolic inhibition and increased oxidative stress23. These results suggest that PFAS clustering could similarly affect their toxicity and mobility along food chain pathways.

Monomeric PFAS primarily enter plants through apoplastic, symplastic, and transmembrane pathways, often facilitated by active transport mechanisms, such as aquaporins and ion transporters24,25,26. Chain length and functional group variations critically influence uptake efficiency27,28. In contrast, stable particulate pollutants—such as micro- and nanoplastics—penetrate plant tissues through physical permeation, endocytosis, or microdamage, with absorption constrained by particle size, surface charge, and cell wall barriers29,30,31,32. We hypothesize that PFAS clusters, spanning molecular and particulate dimensions, will adopt a hybrid uptake mechanism: smaller clusters may utilize transport proteins, while larger aggregates may enter via endocytosis or cell wall disruptions, potentially increasing accumulation risk. By integrating metabolomic analyses to probe alterations in energy metabolism and signaling pathways with proteomic profiling to identify key stress-regulatory proteins, we aim to construct a comprehensive regulatory network of plant responses to PFAS clusters33,34. While hydroponics isolates chemical drivers, the determinants of PFCA clustering, ionic strength, divalent cations, and dissolved organic matter, are ubiquitous in soil porewater and enriched in the rhizosphere, making the phenomenon directly pertinent to agricultural soils.

In this study, we therefore selected four perfluorocarboxylic acids—PFBA (C4), PFHxA (C6), PFOA (C8) and PFDA (C10)—to assemble clusters of distinct sizes and stabilities, which were first characterized by atomic force microscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. Using hydroponically grown Lactuca sativa as a model, we combined growth and physiological assays with integrated metabolomic and label-free proteomic analyses to trace how PFCA cluster size and chain length govern uptake routes (e.g., transporter-facilitated versus endocytotic entry), root-to-shoot translocation, and disruption of central metabolic pathways. By filling this critical knowledge gap in cluster-state PFAS toxicology, our work aims to deliver mechanistic insights essential for developing cluster-aware risk assessment frameworks and safeguarding leafy vegetables against complex PFAS contamination.

Results and discussion

Formation and stability of PFCA molecular clusters

AFM was used to directly observe the white blocky structures identified as molecular clusters as shown in Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1A and 2A. The height distribution shows that the height of PFCA molecular clusters increases with the chain length and concentration of PFCAs. At the same concentration, the height distribution in the histograms increases with the chain length as shown in Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. 1B and 2B. The average heights of clusters with different chain lengths were C4 (35–95 nm), C6 (60–100 nm), C8 (88–144 nm), and C10 (122–194 nm), respectively. Statistical analysis shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 indicates that the mean heights of long-chain clusters (C8 and C10) were significantly greater than those of short-chain clusters (C4 and C6). The distribution histograms confirmed that different chain lengths can produce clusters of different sizes at the same concentration. AFM height histograms and MD outputs jointly indicate that cluster size and molecular packing increase with chain length and concentration, consistent with a hydrophobicity-driven self-assembly mechanism (Fig. 1B, C; Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 2). These cluster-level metrics scale with chain length and coincide with the downstream plant responses described below.

A show the PFCA clusters with different chain lengths obtained on the surface of mica flakes. B show the histograms of the distribution of the heights of the PFCA clusters on mica, where the relative frequency (%) of clusters within defined height intervals is calculated with respect to the total measured height distribution. C show the F-atom density fields of PFCA molecular clusters of different sizes, representing the spatial density of fluorine atoms (g·cm⁻³). (The first to fourth rows in the image are as follows: PFBA clusters; PFHxA clusters; PFOA clusters; PFDA clusters).

Molecular dynamics simulations were used to simulate the interactions of PFCA clusters. Prior to the dynamic simulations, PFCA molecules were uniformly distributed in the simulation box. The number and proportion of PFCA clusters formed in the final state were calculated, and 60–100% of the PFCA molecules formed clusters (Supplementary Table 2). The F-density fields of different sized clusters in the equilibrium configuration are useful for observing the interactions of the PFCA clusters; the higher the F-density field, the closer the clusters are formed. As shown in Fig. 1C, Supplementary Figs. 1C and 2C at the same chain length, the higher the concentration the higher the density of the F-atom density field; at the same concentration, the longer the chain length of the molecule, the higher the density of the F-atom density field, thus, the formation of PFCA clusters is a concentration-driven and hydrophobic-driven phenomenon. This indicated that at higher concentrations, the collision frequency and chemical potential of PFCA molecules increase, promoting self-assembly to reduce system free energy through aggregation and cluster formation. Additionally, as the chain length increases, the hydrophobic tails of PFCA molecules become more pronounced, enhancing overall hydrophobicity. This promotes tighter molecular stacking through hydrophobic interactions, minimizing contact with water molecules35.

Complementing AFM, our MD results indicate that aggregation reduces the free energy of the system relative to the dispersed state, with stronger cohesive interactions at longer chain length. Qualitatively, this corresponds to a deeper free-energy minimum for C10 clusters compared with C4 under our media conditions, implying a larger energetic penalty to disrupt the aggregated state. Thus, within the modest fluctuations in ionic strength and mixing used here, cluster persistence across the exposure window is plausible, providing a mechanistic bridge between chain-length–dependent clustering and the observed uptake/physiological patterns.

Assessment of the physiological impacts of clustered PFCAs on Lactuca sativa: a multiscale analysis of stress responses, root uptake and accumulation, and in planta translocation

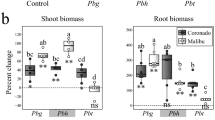

Exposure of Lactuca sativa to PFCA clusters revealed pronounced phytotoxicity that increased with chain length. At each concentration (1, 10, 100 µM), growth inhibition—quantified by reductions in fresh weight and plant height—became progressively more severe from C4 to C10 (Fig. 2A). Under 100 µM C10, fresh weight decreased by 55.9% and plant height by 27.1% relative to control, compared with 26.6% and 17.1% reductions under 100 µM C4 (Supplementary Table 3). Similarly, oxidative-stress markers and soluble-protein responses exhibited greater perturbations with increasing chain length: long-chain clusters (C8, C10) induced up to a 1.25-fold rise in leaf MDA content and a 2.23-fold increase in APX activity, whereas short-chain clusters (C4, C6) elicited only modest changes ( < 1.4-fold) (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that long-chain PFCA clusters impose significantly greater physiological stress and environmental risk to plants compared to short-chain clusters.

A show the effects of Lactuca sativa growth morphology. B show thechanges in physiological responses. C show the relationship between PFCA carbon chain length and translocation factor from root to shoot at three exposure concentrations. D show the relative proportion of PFCA bioaccumulation in roots and leaves under different chain length–concentration combinations.

Bioaccumulation patterns further underscore chain-length-mediated risk disparities. Root concentrations of PFCA clusters increased sharply with chain length (Fig. 2C), with C10 levels 5.5-fold higher than C4 at 100 µM. In contrast, leaf translocation factors declined from 0.4 (C4) to 0.03 (C10) (Data are presented as mean ± SD of three biological replicates to report variability across replicates, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.), reflecting limited upward mobility of long-chain clusters (Fig. 2D). Short-chain clusters thus present a greater risk of aerial-tissue exposure and potential trophic transfer, while long-chain clusters concentrate toxicity within root systems—posing heightened risks for root crops and soil microbiota. Consistent with the larger/denser clusters at longer chain lengths, root burdens increase from C4 to C10 while TF values drop markedly, indicating limited upward transport of long-chain clusters (Fig. 2C, D; Supplementary Fig. 5). Given that roots are the primary site reflecting the toxicity of long-chain clusters, and the practical feasibility of our hydroponic system, we selected root tissues for analysis to ensure the scientific rigor of our experimental design and the reliability of the data. To quantify translocation, shoot tissues were also measured alongside roots, enabling calculation of the TF. Consistent with a cluster-size constraint on xylem loading, TF decreased with increasing chain length whereas root burdens increased, which motivated a root-focused omics design to capture barrier-level responses with high signal-to-noise.

Mechanistically, the enhanced hydrophobic interactions and increased cluster size of long-chain PFCAs favor strong retention within the root apoplast and membrane interfaces, hindering xylem loading and systemic transport. This preferential root accumulation amplifies root-localized metabolic disruption—particularly of the TCA cycle and antioxidant networks—thereby elevating environmental risk under field conditions where long-chain PFCA clusters may persist in irrigation water. Collectively, these chain-length-dependent differences in phytotoxicity, bioaccumulation, and translocation underscore the necessity of incorporating PFCA cluster-state behaviors into environmental risk assessment frameworks.

Metabolomic profiling and co-occurrence network analysis of Lactuca sativa roots under PFCA molecular clusters stress

Non-targeted LC–MS analysis identified a clear, chain-length-and concentration-dependent shift in root metabolic profiles. Principal component analysis (Fig. 3A) separated all PFCA treatments from the control, with long-chain clusters (C8, C10) clustering farther from CK than short-chain clusters (C4, C6), indicating more profound perturbations (PC1 = 54.3%, PC2 = 17.5%).

A show the PCA analysis of differential metabolites in Lactuca sativa roots under PFCAs exposure. B show the schematic diagram of phytochemical level 1 classification of differential metabolites. C show the volcano plots of differential metabolites at a concentration of 100 uM, in which each point represents a metabolite. Here, log2(FC) represents the log2(fold change) of metabolite abundance between two groups. Metabolites up-regulated in the plots are labeled in red, down-regulated in blue, and metabolites without significant differences in gray. Significantly differential metabolites were defined as those with p < 0.05 (t-test) and VIP > 1 (from the OPLS-DA model). Co-occurrence network plots of differential metabolites under different stresses (D PFBA cluster, E PFHxA cluster, F PFOA cluster, and G PFDA cluster) with nodes denoting the metabolites, and links denoting correlations between metabolites.

Further plant chemical classification of the differential metabolites revealed significant changes in key metabolites such as lipids, terpenoids, and flavonoids, reflecting disturbances in membrane lipid structure and related signal transduction, while the defensive secondary metabolic network was activated, suggesting that plants respond to PFCAs stress through multi-level metabolic regulatory mechanisms (Fig. 3B). Combined with differential volcano plot analysis, at 100 μM, the number of significantly altered metabolites increased with carbon-chain length: C4_100 induced 545 changes (226 up, 319 down), C6_100 induced 572 (197 up, 375 down), C8_100 induced 578 (154 up, 424 down), and C10_100 induced 664 (65 up, 599 down) (Fig. 3C). Across all treatments, enriched pathways-spanning lipids, amino acids, carbohydrates, and signaling molecules-largely exhibited negative differential abundance scores, reflecting a net down-regulation of core metabolic activity under larger, more hydrophobic PFCA clusters.

To capture system-level metabolic reprogramming, co-occurrence networks were constructed for each chain length (Fig. 3D–G) based on log₁₀-transformed metabolite abundances, using Spearman correlations with edges retained only if adjusted p < 0.001 (Benjamini–Hochberg correction) and |r | ≥ 0.60 to reduce spurious associations36. Long-chain PFCA clusters (C8, C10) produced larger, denser networks with higher clustering coefficients and shorter average path lengths than short-chain treatments (C4, C6). Specifically, C8 and C10 networks contained more nodes and edges compared to C4, indicating engagement of broader metabolic modules. As chain length increased, positive correlations rose from ~60% (C4) to ~72% (C10), signifying strengthened synergistic interactions, while a modest increase in negative correlations suggested more pronounced antagonistic regulation among competing pathways. Lipids consistently occupied high-degree (hub) positions across all networks; under C10, lipid–lipid hubs formed a particularly tight module, whereas under C4, lipid connectivity was sparser. Amino acids and carbohydrate derivatives also displayed enhanced connectivity under long-chain stress, implying cross-pathway crosstalk to preserve energy and redox homeostasis. Metabolite co-occurrence network analysis further suggests that the observed nonlinearity in the total number of significantly altered metabolites (C4: 545 vs. C10: 664) reflects differential network-level responses of plant metabolism to PFCA chain length, with long-chain PFCAs inducing more systemic perturbations, resulting in a greater number of down-regulated metabolites (C10: 599 vs. C4: 319) but fewer up-regulated metabolites (C10: 65 vs. C4: 226) compared to short-chain counterparts.

Combined evaluation of quantitative changes (Fig. 3A–C) and topological insights (Supplementary Table 4) reveals that cluster-state PFCAs stress triggers a depth- and breadth-dependent reorganization of root metabolism. The tighter, more intricate co-occurrence networks under long-chain treatments suggest that Lactuca sativa roots mobilize multiple metabolite classes in a coordinated manner-likely reallocating carbon and reducing equivalents toward membrane maintenance, antioxidant defenses, and signaling. This network-level synergy appears aimed at mitigating severe perturbations to core energy metabolism, consistent with later observations of TCA cycle enrichment (Visual Interpretation of Chain Length-Dominated PFCAs Metabolic Interference Patterns in the Root).

Visual interpretation of chain length-dominated PFCAs metabolic interference patterns in the root

To further analyze the metabolic regulation mechanism of Lactuca sativa roots in response to PFCAs stress, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed for different metabolites (Fig. 4A). The results showed that three core pathways, namely, phytohormone signaling, pyrimidine metabolism, and ABC transporter protein, were significantly enriched in PFCA treatments of different chain lengths, and the Differential Abundance Score (DA Score) of these pathways were negative, which decreased with the increase of the length of carbon chains. This suggests that PFCAs, especially the long-chain form, may trigger strong metabolic inhibitory effects by interfering with phytohormone regulation, nucleic acid metabolism and transmembrane transport systems. In terms of the overall distribution of pathways, lipid metabolism pathways such as Glycerophospholipid metabolism, Sphingolipid metabolism, and α-Linolenic acid metabolism were the most frequently enriched, suggesting that membrane lipid remodeling and lipid signaling play an important role in the response of roots to PFCAs stress. This suggests that membrane lipid remodeling and lipid signaling play an important role in root response to PFCAs stress. These pathways are closely related to antioxidant regulation, nitrogen metabolism and signaling, suggesting that plants may regulate amino acid metabolism to alleviate stress-induced oxidative damage.

Comparing the enrichment pathways of the PFDA and PFBA treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. 7), we found that the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle) was significantly enriched in the long-chained treatment, while the short-chained group did not show a similar trend, and the enhancement of the TCA cycle as a core energy metabolism pathway might reflect the interference of long-chained PFCAs with mitochondrial function and the stresses of the plant in mobilizing carbon to maintain energy supply and metabolic reprogramming. This phenomenon also echoed the aforementioned trend of increasing complexity and pathway synergies in the metabolic co-occurrence network, further supporting the influence of the degree of PFCAs clustering on the depth of metabolic system interference. In addition, the number of enriched pathways significantly increased as the treatment concentration increased from 1 μM to 100 μM, involving multiple metabolic modules of lipids, amino acids, carbohydrates, and signaling molecules, suggesting that higher exposures triggered a wider range of metabolic perturbations.

It is worth noting that the DA values of the enriched pathways were generally negative in all comparisons (different chain lengths and different concentrations), suggesting that most of the key metabolites were down-regulated, the pathway visualization analysis in Fig. 4B also shows the same trend, reflecting the risk of inhibition of overall metabolic activity, remodeling of energy metabolism, and even physiological decline of the plant caused by the exposure of long-chain PFCAs at high concentrations. In conclusion, the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed the pattern of multiple pathways in response to PFCAs stress in Lactuca sativa roots, and the intensity of the response was positively correlated with the length and concentration of carbon chains. These results, together with the structural changes of the co-occurrence network, support the hypothesis that long-chained and large-cluster PFCAs can induce complex remodeling of plant metabolic systems.

Proteomic response to chain-length-dependent PFCA clusters

Label-free proteomic profiling revealed a clear separation between control and PFCA treatments in principal component analysis (Fig. 5A), indicating substantial proteome remodeling. Even at 1 µM, the number of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) rose with carbon-chain length (Fig. 5B), and this disparity became more pronounced at higher concentrations, underscoring that long-chain PFCAs (e.g., PFDA) elicit more extensive proteomic perturbations than short-chain analogues (e.g., PFBA).

A show the principal component analysis of proteins. B show the schematic diagram of the number of differential proteins for different treatments. C show the annotation of the subcellular localization of differential proteins for different treatments. D show the changes in GO pathway enrichment of differential proteins in Lactuca sativa roots.

Subcellular localization predictions indicate that differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) are primarily enriched in functional compartments such as the cytoplasm, mitochondria, chloroplasts, and extracellular regions. Notably, as carbon chain length and concentration increase, the proportion of protein abundance in the cytoplasm and mitochondria shows a slight increase. At 100 μM, the proportions of DEPs in mitochondria and the cytoplasm under PFBA (C4) were approximately 4.2% and 39%, respectively, whereas under PFDA (C10), the proportions were approximately 5.18% and 40%, respectively (Fig. 5C). This suggests that protein responses in the cytoplasmic metabolic and energy centers are more pronounced under PFCAs stress, while mitochondrial energy metabolism is more severely disrupted under long-chain cluster stress.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment for C10 DEPs highlighted response to oxidative stress, cellular respiration, protein folding, and transmembrane transport (Fig. 5D). The upregulation of the “oxoacid metabolic process” pathway in C10 involves the conversion of key metabolites in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, suggesting that long-chain PFCA may enhance the activity of TCA cycle-related enzymes, thereby promoting mitochondrial energy metabolism to counteract metabolic stress induced by exogenous compounds. Additionally, the upregulation of the “protein transport” pathway indicates that long-chain PFCA regulate intracellular protein transport and transmembrane distribution. Proteomic remodeling intensified with chain length, with C10 showing broader DEP changes and TCA/mitochondrial and antioxidant processes as key targets, consistent with cluster-mediated cellular stress.

In contrast, PFDA treatment resulted in significant downregulation of protein expression in pathways such as “passive transmembrane transport protein activity,” “reactive oxygen species metabolic process,” and “hydrogen peroxide metabolic process,” indicating that cells maintain redox homeostasis by inhibiting certain transmembrane transport channels and regulating the expression of reactive oxygen species metabolic enzymes, thereby preventing the accumulation of excessive oxidative damage.

Overall, these proteomic changes suggest that, compared to C4, long-chain C10, due to its stronger hydrophobicity and bioaccumulation properties, may exert more profound effects on cell membrane integration and mitochondrial function, leading to more significant metabolic remodeling and oxidative stress responses. These findings elucidate the chain-length-dependent phytotoxicity of PFCA in Lactuca sativa roots and identify mitochondrial and antioxidant pathways as key targets of PFCA-mediated stress.

Proteome-metabolome integration reveals key pathways under PFCA clusters stress

Procrustes analysis demonstrated a significant concordance between root metabolomic and proteomic profiles across PFCA treatments (p < 0.01). Combined ordination separated all PFCA-treated samples from the control along a gradient that intensified with carbon-chain length (Fig. 6A). Samples treated with 100 μM C10 clustered farthest from control, reflecting the most severe systemic perturbations. The joint analysis results show that the only significantly co-enriched pathway is the TCA cycle (Supplementary Fig. 10), emphasizing its central role in the physiological stress induced by cluster-state PFCA. Both metabolite (e.g., citrate, L-malic acid) and protein (e.g., fumarate hydratase) levels in the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation decreased under long-chain PFCA stress.

A show the multi-omics analysis revealed significant differences between the control group and different chain length PFCA-treated groups at the protein and metabolite levels. B show the molecular docking results indicated potential binding sites between PFBA, PFDA, and differentially expressed proteins. C show the analysis of metabolic-protein network remodeling and significantly enriched pathways (including the TCA cycle) revealed the response mechanism to cluster-state PFCA stress.

In silico docking of representative PFCA clusters to key enzymes with significant differences confirmed potential inhibitory interactions. PFBA (C4) bound to methyltransferase with a calculated affinity of –6.3 kcal·mol⁻¹, PFDA (C10) bound to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 with –6.4 kcal·mol⁻¹ (Supplementary Table 5). The aforementioned binding patterns reveal that cluster-state PFCAs can interfere with the normal functions of key enzyme proteins through specific binding, suggesting that they exert direct molecular-level regulatory effects on plant physiological processes.

Figure 6C shows a comprehensive mechanism diagram of the metabolic-protein network remodeling and its key response mechanisms under PFCA stress in a cluster state. Hydroponic experiments demonstrated that PFCA clusters were effectively absorbed by lettuce root systems, with significant responses observed in both the metabolome and proteome. Specifically, as the PFCA chain length and cluster size increase, the co-occurrence network among metabolites becomes more tightly interconnected, reflecting more complex metabolic regulatory interactions. Notably, the TCA cycle was significantly enriched in the joint metabolome-proteome analysis (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. S10). Within this pathway, the annotated metabolites showed a decreasing trend, while the enzymes were generally upregulated (Fig. 6C-c), indicating that the TCA cycle is a key pathway prioritized for regulation under cluster-state PFCA stress and plays a central role in reshaping energy metabolism and protein expression networks. This diagram not only reveals the mechanism by which cluster-state PFCA regulates plant adaptation to complex organic pollutants by reshaping energy metabolism and protein expression networks but also provides a molecular basis for future improvements in plant tolerance to pollutant stress.

PFCA molecular clustering represents a critical knowledge gap in environmental risk assessment that may reshape how we evaluate and regulate PFAS contamination. Current regulatory frameworks and safety thresholds are based exclusively on single-molecule toxicity models, completely overlooking aggregation phenomena that may occur widely in environmental systems. This oversight has profound implications for environmental protection and public health. The observed bioaccumulation and metabolic disruption induced by PFCA clusters of varying sizes suggest that current water quality standards may be insufficient to protect agricultural ecosystems, particularly in irrigation scenarios where moderate PFAS concentrations could promote the formation of clusters with diverse sizes. Root vegetables and leafy greens are particularly vulnerable food sources, as they may accumulate persistent PFCA clusters in edible tissues, with larger clusters potentially impairing nutritional quality through disruption of energy metabolism. Beyond agriculture, the size-dependent effects of PFCA clusters may extend to aquatic ecosystems, groundwater systems, and wastewater treatment processes, where current monitoring approaches could underestimate the bioavailability and impact of larger versus smaller clusters. The development of cluster-aware analytical methods and risk assessment frameworks is urgently needed to close this regulatory gap. Future priorities should include field validation studies across diverse environmental matrices, investigation of cluster formation kinetics under realistic environmental conditions, and development of remediation technologies specifically designed to target aggregated contaminant forms. Regulatory agencies must also consider revising water quality criteria and exposure assessment models to account for aggregation states, ensuring that environmental protection strategies are based on actual rather than theoretical contaminant behavior. A practical implication is that existing toxicity thresholds based on nominal PFAS concentrations cannot be assumed to have inadvertently ‘baked in’ aggregation effects, because aggregation is matrix- and protocol-dependent. Cluster-aware reporting (size distribution, fraction clustered, stability) and test design will improve cross-study comparability and the defensibility of health-protective criteria.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Standards of perfluorobutyric acid (PFBA, 98%, C4) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA, 98%, C8) were purchased from McLean Biochemical Technology Co; standards of perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA, 98%, C6) and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA, 98%, C10) were purchased from Aladdin Chemical Co. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade methanol (CH3OH) and acetonitrile (ACN) were purchased from SIGMA-ALDRICH (Shanghai, China). High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade 3-(bromoacetyl) coumarin (BrAC, > 95%) was purchased from Aladdin Chemical Co.

Experimental and theoretical evidence for the formation of PFCA molecular clusters

The shape and size of PFCA molecular clusters in aqueous solution were characterized using an atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker Multimode 8, Germany). PFCAs solutions (PFBA, PFHxA, PFOA, and PFDA) with methanol content of 0.5‰ and concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 µM were deposited on mica sheets. The lowest level (1 µM) represents typical environmental concentrations in water and soil, simulating mild pollution, while 10 and 100 µM reflect more heavily polluted or near-source conditions37,38,39,40. This range is below extreme levels used in plant toxicity studies but still allows us to examine plant accumulation, potential toxic effects, and localized clustering. All samples were imaged after 3 days of dehydration at room temperature41. Concentrations are reported in molar units to enable direct comparison on a molecular basis. The stability of PFCA molecular clusters was probed through MD simulations using the Forcite module in Materials Studio 2019. Simulation boxes were constructed using Amorphous Cell. These boxes contained a water-methanol solvent mixture and PFCA molecules42. Simulations employed the COMPASS II force field under an NVT ensemble, with electrostatic interactions treated using the Ewald summation method. The system was simulated at 298.0 K with Nosé temperature control for 1000 ps and a 1 fs timestep. The last 500 ps of the trajectories were analyzed to obtain the fluorine (F) atom density field and the mean square displacement (MSD)17,42.

PFCA exposure and accumulate in Lactuca sativa

The PFBA, PFHxA, PFOA, and PFDA standards were diluted to 1, 10, and 100 uM using half-strength Hoagland nutrient solution prior to the exposure experiment. The methanol volume in the exposure solution was maintained below 1‰ (v/v) to minimize co-solvent effects43, with an actual methanol content of 0.5‰. Lactuca sativa seedlings were harvested after 14 days of exposure in 1 L polypropylene containers containing the target compounds. Each treatment was replicated three times. Hydroponic exposure was conducted in an artificial climate chamber under a 23 °C/18 °C diurnal temperature cycle (12 h light/12 h dark), with white light at 15,000 lx, Hoagland nutrient solution at pH 6.0–6.5, and relative humidity maintained at 60–70%. Nutrient solutions, spiked with target compounds, were renewed every 5 days, and boxes were wrapped with aluminum foil to minimize microbial and algal growth. To minimize artefactual de-clustering while maintaining analytical feasibility, co-solvent content was capped at 0.5‰ (v/v) methanol and gentle mixing was used. The presence and size of clusters in the exposure media were confirmed by AFM at the tested concentrations (1–100 μM) and at media-renewal checkpoints; complementary MD simulations under the same solvent and concentration windows showed that 60–100% of molecules existed in clusters. These checks ensure that the observed phenotypes reflect bona fide cluster-state exposures rather than co-solvent-dispersed monomers.

The extraction and purification of PFCAs from Lactuca sativa roots and leaves were performed following previously reported methods, with minor modifications

Fresh Lactuca sativa leaves and roots were separately freeze-dried and ground into a fine powder. Approximately 0.04 g of leaf powder and 0.015 g of root powder were extracted with 5 mL of ACN/water (90:10, v/v) by ultrasonication (10 min) and centrifugation (8000 rpm, 10 min). The extraction was replicated three times, with the second extraction of C10-treated samples using pure ACN. The combined supernatants were concentrated under a gentle nitrogen stream (40 °C) to approximately 1 mL. The concentrated extracts were diluted with 9 mL of ultrapure water and applied to a WAX solid-phase extraction column (6 mL, 150 mg) preconditioned sequentially with 5 mL of methanol and 5 mL of ultrapure water. Target compounds were eluted sequentially with 4 mL of 0.1% ammonium methanol (ammonia/methanol, v/v) followed by 4 mL of methanol. The eluates were collected, concentrated to near dryness under a gentle nitrogen stream, and reconstituted in 1 mL of ACN44. They were vortexed (30 s), then derivatized with BrAC at 70 °C for 60 min, cooled, and filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane. Analysis was performed by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection (Shimadzu, Japan) using a Synersi C18 column (5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm I.D.) under gradient elution (flow rate, 1 mL/min; eluent A, 60% ACN; eluent B, 100% ACN). The gradient was held at 100% eluent A for 5 min, increased to 100% eluent B over 30 min, and re-equilibrated at 100% eluent A for 5 min. Fluorescence detection was set at an excitation wavelength of 306 nm and an emission wavelength of 420 nm, with an injection volume of 50 μL using an autosampler45,46.

Growth parameters, photosynthesis and antioxidant system

The height and fresh weight of roots and leaves was used to evaluate Lactuca sativa growth. Lactuca sativa roots were rinsed three times with ultrapure water, drained of surface water and weighed. Fresh Lactuca sativa leaves were collected after hydroponic exposure for the determination of photosynthetic pigments. Pigments were extracted using 95% ethanol (20 mL) in the dark at room temperature for 12 h until decolorization, and the extracts were adjusted to a defined final volume (25 mL). Absorbance was measured at 665, 649, and 470 nm, and the concentrations of chlorophyll a (Ca), chlorophyll b (Cb), and carotenoids (Car) were calculated according to the Lichtenthaler equations47,48. Fresh lettuce leaves and roots from the same treatments were used for the assessment of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity and malondialdehyde (MDA) content. Tissues were homogenized in the extraction buffer and centrifuged, and the resulting supernatants were kept on ice until analysis. APX activity and MDA content were quantified using commercial assay kits (Boxbio Science Technology, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Specifically, APX activity was determined by measuring the absorbance at 290 nm at 10 s and 130 s using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer, whereas MDA content was measured at 450, 532, and 600 nm using a microplate reader. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Non-targeted metabolomics analysis of Lactuca sativa roots

After 14 days of PFCA exposure, Lactuca sativa roots were washed with ultrapure water, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until extraction. Metabolites were extracted with methanol–water (4:1, v/v) containing L-2-chlorophenylalanine as an internal standard, and analyzed using a Thermo UHPLC-Q Exactive HF-X system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with an ACQUITY HSS T3 column. The detection was carried out in both positive and negative electrospray ionization modes over a mass range of 70–1050 m/z. Quality control samples, prepared by pooling aliquots of all samples, were injected at regular intervals to monitor instrument stability48. Raw data were processed using Progenesis QI (Waters Corp., USA) for peak detection, alignment, and normalization. Metabolites were annotated by searching the HMDB, Metlin, and Majorbio databases. Features with relative standard deviation (RSD) > 30% in QC samples were excluded, and the data matrix was normalized and log-transformed before statistical analysis. Multivariate analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), were performed using the R package “ropls” (Version 1.6.2) with 7-cycle interactive validation to assess model robustness. Significantly different metabolites were defined as those with a variable importance in projection (VIP) score from the OPLS-DA model greater than 1 and a p-value from Student’s t test below 0.05, and were subsequently subjected to pathway enrichment analysis using the KEGG database, with statistical evaluation performed in Python (scipy.stats). The data were analyzed through the free online platform of Majorbio Cloud platform (cloud.majorbio.com). The metabolomics data have been deposited to MetaboLights49 repository with the study identifier MTBLS12957.

Proteomic analysis of Lactuca sativa roots

All samples were removed in the frozen state and an appropriate amount of protein lysate was added. The supernatant was collected after grinding and shaking centrifugation; after that, the protein content was determined by BCA method, and the protein was verified by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis after quantification. Peptide separation was performed on a VanquishNeo (Thermo) chromatograph with a uPAC High Throughput column (75 μm×5.5 cm, Thermo, USA). The DIA raw data were imported into Spectronaut™ 19 software system for library analysis. All data were uploaded to the Meiji cloud platform (cloud.majorbio.com) for analysis.

Molecular docking

Select the difference protein 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate triphosphate--homocysteine methyltransferase (XP_023768024.1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 28 (XP_023733478.1) as receptor proteins, and predict the three-dimensional structure of the selected proteins based on Alpha fold. Molecular structure modeling and structural optimization of PFBA and PFDA were performed using Materials Studio to generate ligands. The receptor and ligands were preprocessed using PyMOL and then imported into AutoDock Vina 1.1.2 for molecular docking. Finally, specific conformations were visualized in PyMOL and Discovery Studio Visualizer.

Statistical analysis

The translocation factor (TF) is a quantitative measure used to evaluate the relative distribution and mobility of a contaminant; it reflects the efficiency with which a substance absorbed by the roots is translocated to the aboveground tissues. It was calculated according to the following formula50:

where Cshoot and Croot represent the concentrations of the contaminant in shoot (aerial part) and root tissues, respectively (expressed on a dry weight basis). Concentrations below LODs were replaced with a random number less than half of the LODs. Data were statistically processed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the least significant difference (LSD) test was performed using SPSS 27.0 software, with p < 0.05 as the significance of the difference in means. The figures were prepared using Origin 10.2 software, Adobe Illustrator 2021, chiplot (https://www.chiplot.online/), and Lianchuan Bio (https://www.lc-bio.com/).

Data availability

The metabolomics raw files, processed feature tables, and metadata have been deposited in MetaboLights under accession MTBLS12957. The remaining data are provided in the manuscript and the supplementary information files.

References

Zhang, K. et al. Review of trace organic chemicals in urban stormwater: concentrations, distributions, risks, and drivers. Water Res. 258, 121782 (2024).

Kali, S. E., Österlund, H., Viklander, M. & Blecken, G.-T. Stormwater discharges affect PFAS occurrence, concentrations, and spatial distribution in water and bottom sediment of urban streams. Water Res. 271, 122973 (2025).

Washington, J. W., Yoo, H., Ellington, J. J., Jenkins, T. M. & Libelo, E. L. Concentrations, distribution, and persistence of perfluoroalkylates in sludge-applied soils near Decatur, Alabama, USA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 8390–8396 (2010).

Ackerman Grunfeld, D. et al. Underestimated burden of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in global surface waters and groundwaters. Nat. Geosci. 17, 340–346 (2024).

Wang, Z., DeWitt, J. C., Higgins, C. P. & Cousins, I. T. A never-ending story of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)? Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 2508–2518 (2017).

Cousins, I. T., Johansson, J. H., Salter, M. E., Sha, B. & Scheringer, M. Outside the safe operating space of a new planetary boundary for per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 11172–11179 (2022).

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Lifetime drinking water health advisories for four perfluoroalkyl substances. U.S. EPA, 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/06/21/2022-13158/.

Ateia, M. & Scheringer, M. From “forever chemicals” to fluorine-free alternatives. Science 385, 256–258 (2024).

Key, B. D., Howell, R. D. & Criddle, C. S. Fluorinated organics in the biosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 31, 2445–2454 (1997).

Evich, M. G. et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment. Science 375, eabg9065 (2022).

Zheng, J. et al. Catalytic hydrolysis of perfluorinated compounds in a Yolk-Shell micro-reactor. Adv. Sci. 12, 2413203 (2025).

Bera, P. P., Horný, Ľ & Schaefer, H. F. Cyclic perfluorocarbon radicals and anions having high global warming potentials (GWPs): structures, electron affinities, and vibrational frequencies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 6692–6702 (2004).

Li, Q. & Chen, B. Organic pollutant clustered in the plant cuticular membranes: visualizing the distribution of phenanthrene in leaf cuticle using two-photon confocal scanning laser microscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 4774–4781 (2014).

Gong, P. et al. Persistent organic pollutant cycling in forests. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 182–197 (2021).

Guo, X., Jin, X., Lv, X., Pu, Y. & Bai, F. Real-time visualization of perylene nanoclusters in water and their partitioning to graphene surface and macrophage cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 7926–7933 (2015).

Kato, T., Kutsuna, T., Yabuuchi, K. & Mizoshita, N. Anisotropic self-aggregation of an anthracene derivative: Formation of liquid-crystalline physical gels in oriented states. Langmuir 18, 7086–7088 (2002).

Chen, Q., Zheng, J., Yang, Q., Dang, Z. & Zhang, L. Effect of carbon chain structure on the phthalic acid esters (PAEs) adsorption mechanism by mesoporous cellulose biochar. Chem. Eng. J. 362, 383–391 (2019).

Wild, E., Cabrerizo, A., Dachs, J. & Jones, K. C. Clustering of non-polar organic compounds in lipid media: evidence and implications. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 11699–11703 (2008).

Israelachvili, J. N. Intermolecular and Surface Forces (Academic Press, 2011).

Fu, K. et al. Understanding the selective removal of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances via fluorine–fluorine interactions: a critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 16669–16689 (2024).

Reichenbächer, K., Süss, H. I. & Hulliger, J. Fluorine in crystal engineering—“the little atom that could”. Chem. Soc. Rev. 34, 22–30 (2005).

Kumarasamy, E., Manning, I. M., Collins, L. B., Coronell, O. & Leibfarth, F. A. Ionic fluorogels for remediation of per-and polyfluorinated alkyl substances from water. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 487–492 (2020).

Zheng, S. et al. Elevated toxicity and high-risk impacts of small polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon clusters on microbes compared to large clusters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 224–233 (2024).

Miller, E. L., Nason, S. L., Karthikeyan, K. & Pedersen, J. A. Root uptake of pharmaceuticals and personal care product ingredients. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 525–541 (2016).

Wang, T.-T. et al. Uptake and translocation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) by wetland plants: tissue-and cell-level distribution visualization with desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (DESI-MS) and transmission electron microscopy equipped with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (TEM-EDS). Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 6009–6020 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Impact mechanisms of humic acid on the transmembrane transport of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in wheat at the subcellular level: the important role of slow-type anion channels. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 8739–8749 (2023).

Mei, W. et al. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in the soil–plant system: Sorption, root uptake, and translocation. Environ. Int. 156, 106642 (2021).

Adu, O., Ma, X. & Sharma, V. K. Bioavailability, phytotoxicity and plant uptake of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): a review. J. Hazard. Mater. 447, 130805 (2023).

Singh, N., Abdullah, M. M., Ma, X. & Sharma, V. K. Microplastics and nanoplastics in the soil-plant nexus: sources, uptake, and toxicity. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1613–1642 (2023).

Liu, Y., Guo, R., Zhang, S., Sun, Y. & Wang, F. Uptake and translocation of nano/microplastics by rice seedlings: evidence from a hydroponic experiment. J. Hazard. Mater. 421, 126700 (2022).

Luo, Y. et al. Quantitative tracing of uptake and transport of submicrometre plastics in crop plants using lanthanide chelates as a dual-functional tracer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 424–431 (2022).

Ding, J. et al. Exposure to heavy metal and antibiotic enriches antibiotic resistant genes on the tire particles in soil. Sci. Total Environ. 792, 148417 (2021).

Johnson, C. H., Ivanisevic, J. & Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics: beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 451–459 (2016).

Song, L. et al. A transcription factor hierarchy defines an environmental stress response network. Science 354, aag1550 (2016).

Sánchez-Iglesias, A. et al. Hydrophobic interactions modulate self-assembly of nanoparticles. ACS Nano 6, 11059–11065 (2012).

Wu, E. et al. Fatty acid metabolic impairment in soil microbes induced by PFAS: dependence on the fluorocarbon chain length, headgroups, and ether attached. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 5452–5462 (2025).

Liu, Z. et al. Risk assessment and source identification of perfluoroalkyl acids in surface and ground water: spatial distribution around a mega-fluorochemical industrial park, China. Environ. Int. 91, 69–77 (2016).

Moody, C. A. & Field, J. A. Determination of perfluorocarboxylates in groundwater impacted by fire-fighting activity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 2800–2806 (1999).

Moghadasi, R., Mumberg, T. & Wanner, P. Spatial prediction of concentrations of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in European soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 10, 1125–1129 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Phytotoxicity induced by perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate via metabolomics. J. Hazard. Mater. 389, 121852 (2020).

Kim, S., Ratchford, D. C. & Li, X. Atomic force microscope nanomanipulation with simultaneous visual guidance. ACS Nano 3, 2989–2994 (2009).

Zuo, X. et al. Inter-molecular interactions of phthalic acid esters and multi-stage sorption revealed by experimental investigations and computation simulations. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 134018 (2022).

Zhou, J. et al. Insights into uptake, translocation, and transformation mechanisms of perfluorophosphinates and perfluorophosphonates in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 276–285 (2019).

Xiang, L. et al. Determination of trace perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids in edible crop matrices: matrix effect and method development. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 8763–8772 (2017).

Poboży, E., Król, E., Wójcik, L., Wachowicz, M. & Trojanowicz, M. HPLC determination of perfluorinated carboxylic acids with fluorescence detection. Microchim. Acta 172, 409–417 (2011).

Ryu, H., Li, B., De Guise, S., McCutcheon, J. & Lei, Y. Recent progress in the detection of emerging contaminants PFASs. J. Hazard. Mater. 408, 124437 (2021).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Method. Enzymol. 148, 350–382 (1987).

Zhu, D. et al. Adaptive expression of phage auxiliary metabolic genes in paddy soils and their contribution toward global carbon sequestration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2419798121 (2024).

Yurekten, O. et al. MetaboLights: open data repository for metabolomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D640–D646 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. The fate of sulfonamides in the process of phytoremediation in hydroponics. Water Res. 198, 117145 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42277399, 42130711, 42477245, and 42307165).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.C.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, validation, writing-original draft; C.P.Z.: conceptualization, resources, supervision, writing-review & editing; P.F.W.: investigation, formal analysis, data curation, visualization; W.R.Z.: investigation, validation; S.Y.Z.: formal analysis, data processing, visualization; S.Y.W.: formal analysis, statistical analysis, writing-review & editing; J.H.D.: methodology, investigation (molecular docking), validation, writing-review & editing; M.W. formal analysis, investigation; H.Z.L.: resources, methodology development, validation, writing-review & editing; B.P.: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, project administration, supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Zhao, C., Wang, P. et al. Molecular clustering enhances perfluorocarboxylic acid bioaccumulation in lactuca sativa by disrupting the tricarboxylic acid cycle. npj Emerg. Contam. 2, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44454-025-00016-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44454-025-00016-y