Abstract

Lipid nanoparticle (LNP) components can impact the safety and immunogenicity of mRNA vaccines. Here we examine the mechanisms contributing to the performance of mRNA-LNP vaccines by exploring the impact of nucleoside modifications and LNP components on translational efficiency, innate immune activation, and immunogenicity. Our data reveals several molecular and immunological parameters affected by nucleoside modification including a synergistic effect of the mRNA and ionizable lipid composition on the immune activation triggered by the mRNA-LNP formulation. Our results indicate changes in the LNP composition, independent from whether the mRNA is modified or unmodified, caused differential expression of genes associated with innate and antiviral immunity. We believe these findings offer valuable insights into mRNA vaccine function and offer strategies for enhancing vaccine efficacy and reducing the reactogenicity of next generation mRNA vaccines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

mRNA vaccines have revolutionized the field of immunization by harnessing the power of genetic information to stimulate robust immune responses against infectious diseases1,2. mRNA technology enables production of antigens within the human body, triggering an immune response and conferring protection against specific pathogens. Since the authorization and successful deployment of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19, there has been a surge of interest and research focused on optimizing their efficacy, safety, and practicality3,4,5.

While preclinical data generated over the past years indicate that unmodified mRNA vaccines elicit a robust immune response to pathogens6,7, recent clinical trial data have suggested that vaccine candidates using a modified mRNA have an advantage in delivering a reduced reactogenicity profile7,8. RNA behaves as a pathogen-associated molecular pattern and is recognized by TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, RIG-I and MDA-5 in a sequence- and structure-dependent manner leading to innate immune activation and associated reactogenicity7. It is well known that certain ribonucleoside modifications can reduce the activation of cellular RNA sensors6. Thus, replacement of uridine with naturally occurring derivatives like pseudo-uridine (Ψ) and N1-methyl-pseudouridine (m1ψ) may limit innate immune detection and activation of type 1 interferons, resulting in reduced inflammation and potentially enhanced translation of the encoded protein8.

Despite the use of m1ψ in currently licensed vaccines, moderate to high innate immune responses including antiviral and type 1 interferon signaling after primary immunization followed by amplified inflammatory responses characterized by an increased frequency of circulating inflammatory monocytes and elevated sera IFNg levels post-secondary immunization have been reported9,10. LNP components, with the ionizable amino/cationic lipid being its most critical constituent for facilitating the intracellular delivery of polynucleic acids11,12, are known to be immunogenic and can induce inflammatory signaling cascades13,14,15. LNPs can behave as adjuvants activating pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) expressed by antigen presenting cells. The ionizable lipid has been shown to promote IL-6 cytokine production, a factor that plays a role in the activation of antigen-specific CD4 follicular helper T cells and germinal center B cells16. Some LNPs have also been reported to stimulate TLR2 and TLR4 leading to NF-kB activation17. Moreover, LNP particle size, charge and chemistry can affect activation of immune cells and complement as well as induce inflammation17.

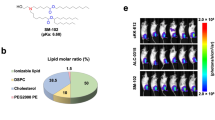

To better understand cellular responses to mRNA vaccines, we examined the translation efficiency, immunogenicity and tolerability of different mRNA vaccines using in vitro and in vivo models. To elucidate the mechanisms underlying improved performance of nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines, we compared unmodified uridine (UNR) and N1-methylpseudouridine (m1ψ)-modified (MNR) non-replicating mRNA encoding hemagglutinin (HA) from influenza viruses. HA antigens from five different strains of influenza A/Wisconsin/588/2019 (Wisconsin HA), A/Tasmania/503/2020 (Tasmania HA), B/Washington/02/2019 (Washington HA) and B/Austria/1359417/2021 (Austria HA) were tested in vitro, and the H3N2 influenza strain A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016 (Sing16 HA) was selected as our model antigen for immunization studies in mice and non-human primates (NHPs) (Supplementary Table 2). Sing16 HA mRNA was delivered using different LNP formulations comprised of OF-02, cKK-E10, and SM-10218,19,20. We selected cKK-E10, OF-O2, and SM-102 LNPs because these ionizable lipids have been extensively characterized in the literature, and their LNP formulations have been evaluated in clinical trials, providing a robust benchmark for comparison in terms of efficacy, safety, and translational relevance.

Results

Modification of mRNA can result in an increase in protein expression in vitro

To assess the impact of mRNA modification and LNP formulation on HA protein expression, mRNA encoding Sing16 HA in either a UNR or MNR format was formulated as OF-02, cKK-E10, or SM-102 LNPs (Supplementary Table 1) and transfected in primary human myoblast (HSKM) and primary human dendritic cells (hDCs) at different doses. Protein expression was measured by immunofluorescence imaging (IF) in HSKM cells (Fig. 1a), and by flow cytometry in hDCs (Fig. 1d) at 24 h post-transfection. Representative flow cytometry plots for measuring HA protein expression were shown in Fig. 1c. In both cell types and across multiple doses, the m1ψ MNR mRNA conferred significantly higher target protein expression compared to UNR mRNA for cKK-E10 and OF-02 LNPs. However, for the SM-102 formulation cell type-specific differences in protein expression between UNR and MNR mRNAs were observed. While MNR mRNA trended toward higher HA protein expression in dendritic cells with SM-102, UNR mRNA showed a higher protein expression in HSKM and there was no difference in cell viability (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 6). These results suggest that the choice of ionizable lipid and target cell type can result in differences in protein expression.

a Graph represents mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of hemagglutinin (HA) protein expression of 1 μg or 10 μg of Sing16 HA mRNA-LNPs transfected per million cells, determined using IF 24 h post-transfection in primary human myoblast (HSKM) cells. b Graph represents the percentage of viable hDCs transfected with 5 μg of Sing16 mRNA-LNPs determined using flow cytometry 24 h following transfection. c Representative flow cytometry plots for determining HA protein expression in hDCs are shown. d Graph represents the percentage of Sing16 HA positive cells following transfection of hDCs with 5 μg of Sing16 HA mRNA-LNP, determined using flow cytometry 24 h post-transfection. P-value determined by unpaired T-test analysis. N = 3 experimental replicates and 6 replicates in each experimental repeat for figures a, b and d. e Graph represents mean MFI of HA protein from HSKM cells transfected with 1 μg/million cells of mRNA OF-02 LNP encoding four different strains: A/Wisconsin, A/Tasmania, B/Washington and B/Austria detected with strain-specific primary antibody. n = 3 experimental replicates with n = 8 replicates for each experimental repeat. P-values were determined by unpaired T-test analysis. N = 3 independent donor samples. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001.

In addition to Sing16 HA, we tested the expression of HAs from 4 other influenza strains- Wisconsin, Tasmania, Washington and Austria in the presence or absence of the m1ψ modification and formulated as OF-02 LNPs (Fig. 1e). As previously observed for Sing16 HA mRNA, MNR Wisconsin HA strain demonstrated a higher expression than UNR while Tasmania HA showed comparable expression between UNR and MNR. Washington HA and Austria HA results were considered inconclusive due to higher dsRNA levels. Overall, our data suggests that incorporation of chemically modified nucleosides such as N1-methylpseudouridine can increase protein production in mRNA vaccines although the extent of increase can depend on the impurities, sequence context and delivery.

Both unmodified and modified mRNA-LNPs can cause global translational repression in vitro

To assess the impact of mRNA modification on global cellular translation, we performed a puromycin incorporation assay which measures the total amount of active translation in the cell by quantifying the amount of puromycin incorporated into growing polypeptide chains (Fig. 2a). HSKM cells were transfected with either UNR or MNR Sing16 HA mRNA delivered as OF-02 or cKK-E10 LNPs and cultured for 20 h. Cells were then treated with puromycin to label all actively translating polypeptides, after which proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and puromycin incorporation measured by blotting with an anti-puromycin antibody (Fig. 2b). Untreated cells showed a strong incorporation of puromycin that was abolished by treatment with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide. Transfection with both UNR and MNR mRNA at the lowest doses tested showed translational inhibition by ~58% with both LNPs (Fig. 2c), indicating transfection with mRNA in general impacts cellular translation. At all dose levels MNR showed higher global translation levels than UNR, with MNR LNPs demonstrating 40% and 46% higher translation levels with cKK-E10 and OF-02 LNPs, respectively. The increase in the differential observed over the dose response curve further supports that UNR mRNA has a stronger effect on global translation repression. Further, OF-02 LNPs exhibited greater translational repression than cKK-E10 at all dose levels.

Puromycin incorporation assay to measure global cellular translation by western blot. a Mechanism and workflow for puromycin incorporation assay by western blot. b Western blot image using anti-puromycin (green) and anti-actin (red) antibodies. Cells were transfected with unmodified and modified Sing16 HA mRNA-LNPs over a dose response curve from 1.25–10 µg/million cells. c Quantification % translational inhibition calculated from puromycin signal across the entire lane. Maximum inhibition from Cycloheximide control indicating 100% translational inhibition. Two-way Anova with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test was performed. p > 0.05, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001.

Both unmodified and modified mRNA-LNPs induced antiviral responses in vitro

To determine the effect of UNR and MNR on the global transcriptome, Sing16 HA mRNA delivered as OF-02, cKK-E10 or SM-102 LNPs were used to transfect HSKM cells, and the transcriptome was analyzed at 1, 4, and 24 h post-transfection. Across all LNPs, the transcriptome exhibited a high degree of induced differential response relative to the buffer controls (Fig. 3a, top). The top 50 upregulated genes globally across conditions showed a strong antiviral response signature, inclusive of genes such as the OAS family, MX1, and the IFIT family (Fig. 3a, bottom). To validate that antiviral associated genes were a key axis of response and elucidate other axes of differentiation amongst lipids, gene set variation analysis (GSVA) was performed using MSigDB module C5 (Gene Ontology [GO]) ( ~ 8000 genesets) to calculate enrichment scores across genesets per sample. From this, a principal component analysis (PCA) was calculated using the top variable genesets (n = 1527), where PC1 and PC2 explained 77.2% and 7.7% of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 3b). This PCA based on GSVA-derived enrichment scores shows clear axes of separation of the buffer and SM-102 LNP from cKK-E10 and OF-02 LNPs across PC1 and PC2 (Fig. 3b) confirming previous findings that uptake and protein expression can be dependent on cell type and that SM-102 LNPs may not deliver mRNA efficiently to muscle fiber in a murine model21. To assess the signatures driving the clustering, top genesets correlating with the principal components were selected based on the magnitude of the rotation component of the PCA per geneset. PC1-associated signatures showed a clear positive enrichment of processes associated with protein translation, such as the GO protein binding, modification, and metabolic process genesets (Fig. 3b, bottom), while PC2 showed an enrichment for immune-related processes, including the GO cytokine receptor binding, response to virus, cell death, and IL-1 response genesets (Fig. 3b, left). While OF-02 LNP showed a stronger antiviral signature with UNR at the 4 h time-point, with SM-102 this was not observed until 24 h post-transfection, and cKK-E10 showed little differentiation of UNR vs. MNR at any time-point across top PC1/PC2 associated signatures. The difference in gene expression profiles for OF-02 and SM-102 could be a result of differences in cell uptake kinetics and composition variance, ultimately leading to different amounts of mRNA being delivered to the cell. These results show that in addition to the modification of mRNA, the delivery vehicle has an impact on the global transcriptional profile of the cells.

a Waterfall plot showing each gene’s maximum induction across any condition shown by log2 fold change relative to buffer (top), with the top 50 upregulated genes by absolute max log2 fold change highlighted (bottom). b Principal component analysis (PCA) was constructed using enrichment scores of top variable genesets (n = 1517) calculated by gene set variation analysis (GSVA). Samples are shown as dots on the main plot. Waterfall plots are shown adjacent to Principal components 1 (PC1 [bottom]) and 2 (PC2 [left]) of the aggregated GVSA scores for top genesets (named at right).

Modification of mRNA had a moderate impact on functional antibody titers

To evaluate whether the increase in protein expression observed in MNR formulations could result in an increase in functional antibody titers, UNR and m1ψ MNR Sing16 HA-LNPs were evaluated in BALB/c mice with 0.08, 0.4 or 1 μg mRNA-LNP administered intramuscularly in a two-dose regimen, 3 weeks apart. LNPs prepared with ionizable lipids OF-02, cKK-E10 and SM-102 were evaluated for functional antibody responses as measured by hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers against the homologous A/Singapore/ INFIMH160019/2016 H3N2 strain (Fig. 4). There were no significant differences in HAI titers between UNR and MNR at all dose levels of OF-02 and SM-102 LNPs. However, significantly higher HAI titers (p < 0.05) were observed with MNR cKK-E10 as compared to equivalent dose levels of UNR cKK-E10 at 0.08 μg and 1 μg doses. To check the impact of mRNA modification on local reactogenicity, we recorded reactions at the injection site. There were no significant differences in the site of injection reactions between the UNR and MNR groups. However, there was an apparent increase in edema and erythema scores compared to the unmodified treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. 3). While our data showed tendency of higher reactogenicity with unmodified mRNA, consistent with published nonclinical and clinical studies on mRNA-LNP vaccines22, it is important to acknowledge that dsRNA contamination can be a confounding factor.

BALB/c mice (n = 8 per group) were immunized twice intramuscularly (IM), 3 weeks apart with 1, 0.4, and 0.08 μg of different Sing16 HA mRNA-LNP formulations. Serum titers were measured by hemagglutinin inhibition assay (HAI) against homologous A/Singapore/INFIMH160019/2016 H3N2 Influenza virus strain and geometric mean titers were graphed for a Sing16 HA-OF-02, b Sing16 HA-cKK-E10 or c Sing16 HA-SM-102 LNPs.

To further evaluate immunogenicity of the mRNA formulations, a dose range of 15, 45, and 135 μg of UNR and MNR Sing16 HA-cKK-E10 and Sing16 HA-SM-102 were tested in NHPs with two doses administered intramuscularly at 4-week intervals. Robust HAI titers were induced in all treatment groups with titers peaking between Days 42-56 (Fig. 5). Peak antibody responses were recorded at 135 μg for SM-102 LNP (log10 HAIt / HAI0 = 2.51) and at 45 μg for cKK-E10 LNP (log10 HAIt / HAI0) = 2.26) (Supplementary Fig. 1) and the impact of m1ψ modification was somewhat variable between the two LNPs. For cKK-E10, significantly higher antibody titers were recorded on Days 28 (p < 0.001), 56 (p < 0.05), 90 (p < 0.001) and 180 (p < 0.001) in the MNR treatment groups at the 45 μg dose (Supplementary Fig. 1). Beyond Day 56, antibody titers in the 45 μg and 135 μg cKK-E10 MNR groups were maintained, indicating potential persistence of functional antibodies in NHPs after modified mRNA vaccine-based immunization. For the SM-102 treatment group, titers elicited by MNR formulations were significantly better than UNR in the 135 μg group at Days 14 and 42 (p < 0.05, logFC = 0.75 and 0.7, respectively). On Days 28 and 56, MNR-induced titers were still better than UNR, but did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.33 and 0.08; logFC = 0.25 and 0.45, respectively in Supplementary Fig. 1). Unlike what was observed for MNR cKK-E10, the titers induced by the 135 μg dose of MNR SM-102 formulations were somewhat lower on Day 90 (p = 0.08; logFC = −0.45) possibly indicating a weaker persistence of antibody titers for MNR SM-102 (Supplementary Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Overall, the benefit of m1ψ modification was less apparent with the SM-102 formulation, where the MNR formulation induced significantly higher neutralizing antibody titers than the UNR only at the 135 μg dose on Days 14 and 42. As a marker of systemic inflammation, we measured C reactive protein (CRP) serum levels in vaccinated NHPs. Supplementary Fig. 4 shows that induction of CRP was transient, peaking at Day 2 and reduced to baseline by Day 7 for all treatments. Importantly, modification of mRNA was not sufficient to reduce induction of CRP following vaccination and empty LNP also increased CRP levels in NHPs.

Cynomolgus macaques (n = 4–6 per group) were immunized at Day 0 and Day 28 by intramuscular route with 135, 45, or 15 μg of different mRNA-LNP formulations encoding for the H3-HA protein from the A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016 strain of influenza. Serum titers taken over the course of 1 year were measured by hemagglutinin inhibition assay (HAI) against homologous A/Singapore/INFIMH160019/2016 H3N2 Influenza virus strain and geometric mean titers were graphed for the following mRNA-LNPs: a Sing16 HA-cKK-E10 15 μg, b Sing16 HA-cKK-E10 45 μg, c Sing16 HA-cKK-E10 135 μg, d Sing16 HA-SM-102 15 μg, e Sing16 HA-SM-102 45 μg, f Sing16 HA-SM-102 135 μg.

The impact of mRNA modification on induction of inflammatory cytokines is species-dependent

To better understand the impact of mRNA modification on innate immune responses, serum cytokines and chemokines were assessed in mice (Fig. 6a) and NHPs (Fig. 6b). Mice were immunized with UNR and MNR versions of Sing16 HA delivered with either OF-02, cKK-E10 or SM-102 LNPs while NHPs were immunized with UNR and MNR versions of Sing16 HA delivered with either cKK-E10 or SM-102 LNPs.

a BALB/c mice (n = 8 per group) were immunized twice intramuscularly, 3 weeks apart with 1 μg of either UNR or MNR Sing16 HA-OF-02, Sing16 HA-cKK-E10 or Sing16 HA-SM-102 lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). Mice were bled pre-study and 24 h post-priming. Cytokine analysis was performed using Milliplex mouse cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead panel as described in methods. Cynomolgus macaques (n = 4-6 per group) were immunized at Day 0 and Day 28 by IM route with 135 μg of either UNR or MNR Sing16 HA-cKK-E10 or Sing16 HA-SM-102 LNPs. Blood was taken at 6-days pre-study (baseline), and 2-days post each administration. Samples were analyzed for b serum cytokine levels by Luminex and c whole blood transcriptomic analysis; volcano plots were made for select cytokines/chemokines of interest.

In mice, induction and upregulation of cytokines such as IFNγ, IL-1a, IP10, VEGF, MIP1b and IL-5 was similarly detected in both the UNR and MNR LNP vaccinated mice regardless of the lipid used in the formulation (Fig. 6a). However, OF-02 showed higher upregulation of cytokines, including IL-6, GCSF, IL-2 and IP10 than cKK-E10 and SM-102 LNPs. Overall, RNA modification did not substantially reduce these serum cytokine levels compared to unmodified mRNA. Similar observations were reported by others23 wherein m1ψ modification of mRNA not only did not impact the serum cytokine profile in mice but also did not impact in vivo protein expression, immunogenicity or induction of liver enzymes alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase23. On the contrary, in NHPs, higher cytokine induction was demonstrated in UNR LNP vaccinated animals when compared to the MNR LNP cohort. Cytokines such as IFNγ, IFNα, and MCP1 were higher with UNR LNP compared to MNR LNP immunized animals, while other cytokines, such as TNFα (cKK-E10), IL-1RA and GCSF (SM-102) were still significantly induced in MNR LNP-immunized NHPs (Fig. 6b). An enhanced cytokine induction response after the second vaccine administration was demonstrated in the cKK-E10 cohort, a phenomenon which has been previously observed24,25. For instance, at the 135 µg dose, UNR cKK-E10 induced a 2-fold increase in IFNγ at Day 2 which was further enhanced following the second administration to an 8-fold increase at Day 30, whereas UNR SM-102 induced a 2-fold increase of IFNγ at both Day 2 and Day 30 following the second administration. Similarly, UNR cKK-E10 induced a 16-fold rise in IFNα at Day 2 which was enhanced by the second administration to 32-fold at Day 30, as compared to UNR SM-102 which induced a 32-fold and 16-fold rise in IFNα at Day 2 and Day 30, respectively.

Transcriptional signatures of mRNA vaccination in NHPs

The sensitivity of existing cytokine assays and their specificity to NHPs could have an impact on our ability to accurately detect subtle changes in sera cytokines. To address these concerns as well as investigate the impact of mRNA modification on the transcriptional signatures of mRNA vaccination, we next performed bulk mRNA sequencing on whole blood drawn from NHPs treated with cKK-E10 or SM-102 LNP formulations made with UNR and MNR formats of Sing16 HA at pre-study and 2 days post primary immunization. Confirmation of the serum cytokine and chemokine findings was done by interrogating differential expression of cytokine and chemokine genes taken at Day 2 compared to pre-immunization. In concurrence with the sera cytokine findings, a significant dose- and LNP-dependent increase in cytokine genes in UNR formulations was observed, which was mostly abrogated by m1ψ-modification (Fig. 6c). This includes the gene encoding for IL1RA (IL1RN) which was observed in NHP sera after immunization (Fig. 6b). A strong dose-dependent upregulation of genes encoding for chemokines such as CCL8 and CXCL10 was also noted, as previously reported to be induced by mRNA-based vaccines24. Comparing the serum cytokines (Fig. 6b) with the cytokine gene expression profile (Fig. 6c), we also observed a trend that the inflammatory cytokine profile of SM-102 appeared less impacted by m1ψ-modification as compared to cKK-E10, highlighting the potential impact of LNP selection as a driver of proinflammatory cytokine responses. Of note, CXCL10 protein was not detectable in the serum, supporting the inclusion of multiple technologies of varying sensitivities and specificities for biomarker discovery work.

As mRNA vaccines are likely to impact many aspects of the immune response beyond cytokine induction, we next assessed the global impact of UNR and MNR formulations on differential gene expression. Administration of mRNA vaccines, regardless of formulation, resulted in a substantial induction of differentially expressed genes in NHPs (Fig. 7). PCA analysis details a dramatic separation between pre- and post-vaccination for unmodified mRNA-LNP formulations, unlike those containing modified mRNA where greater overlap was observed between transcriptional profiles for formulations of both ionizable lipids (Fig. 7a). In general, both LNPs induced similar transcriptome profiles, with UNR being a stronger inducer of differentially expressed genes compared to modified mRNA (Fig. 7b). Although there was a diminished impact on differential gene expression in animals treated with both MNR formulations compared to UNR, it is of note that the magnitude of this impact was LNP-dependent, with more significantly upregulated genes observed in animals immunized with modified mRNA formulated in SM-102 compared to cKK-E10 (509 vs 75 genes, respectively; Fig. 7b). Substantiating the influence of LNP selection on the transcriptional modulatory potential of m1ψ-modification, we conducted a concordance analysis between the gene expression profiles induced by UNR and MNR formulated in SM-102 and cKK-E10 and found the profiles to largely be concordant for SM-102 (r = 0.8659) unlike the relationship observed with cKK-E10 (r = 0.2917; Fig. 7c).

a Principal-component analysis (PCA) of transcriptomes generated prior to and after vaccination (Day 0 and Day 2). The variation in the global gene expression profiles of the top 500 most variable genes is shown. Principal components 1 (PC1) and 2 (PC2) are shown, which represent the greatest biologically relevant variation in gene expression. b Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) comparing Day 2 and Day 0 for each lipid nanoparticle and dose evaluated. DEGs are defined as genes with p < 0.05 and log2 fold change (logFC) of more than 2 or less than -2. Up-regulated and down-regulated genes are indicated in red and blue respectively and non-significant genes are indicated in gray. c Concordance analysis of logFC between unmodified and modified mRNA in ckk-E10 and SM102 LNPs. Concordant and discordant genes are magenta and cyan, respectively.

Consistent with the observations in HSKM cells treated with UNR and MNR Sing16 HA (Fig. 3b), amongst the top canonical pathways activated in NHPs following mRNA vaccination were genes associated with pattern recognition receptors, interferon signaling and the role of PKR in interferon induction (Fig. 8). Induction of genes associated with PKR signaling and interferon signaling was greatly reduced by mRNA modification, with a larger impact observed when mRNA was formulated in cKK-E10 LNP compared to SM-102. When examining the potential influence of LNP composition on the impact of mRNA modification, we observed a greater reduction in expression of genes associated with the PKR signaling cascades (e.g., OAS1, DDX58, STAT1) and interferon signaling (e.g., MXI, IFI6, IFIT3) in MNR formulated in cKK-E10 than SM-102 (Fig. 8b). Interestingly, genes associated with the interferon response continued to be induced by MNR formulations, irrespective of whether the mRNA was formulated with cKK-E10 or SM-102 LNPs (Fig. 8b). Further experiments were carried out with empty LNP (cKK-E10) to investigate if transcriptional responses seen could be due to the LNP delivery vehicle alone. Our data showed that certain pathways, such as those associated with phagosome formation, are induced following administration of empty LNPs, indicating that the LNP delivery system alone can activate specific innate immune pathways (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a The heatmap depicts overrepresentation of canonical pathways enriched in whole blood of non-human primates following a 135 μg dose of mRNA-LNP (cKK-E10 and SM-102) vaccines. The color of each cell refers to the -log10 (p-value) and indicates the significance of the pathway enrichment (see color key). The color bar below the heatmap denotes the mRNA modification class (UNR: blue; MNR: red). b The heatmap depicts the top canonical pathways enriched following mRNA vaccination. The color of each cell refers to the log2 fold change of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) composed within the pathway (see color key). Genes with a log2 fold change of more than 1 and a p-value of < 0.05 were selected for the representation. Violin plots were prepared for each of the selected pathway heatmaps to provide a visual reference of the difference in median DEG expression between treatments (quartiles as well as minima and maxima bounds are shown).

To further compare in vitro findings to those observed in NHP, we next assessed genes associated with protein translation and degradation. Figure 9 shows a heatmap of a representative subset of these genes for NHPs vaccinated with 135 μg of Sing16 HA-cKK-E10 or Sing16 HA-SM-102 in UNR or MNR mRNA formats. In concurrence with in vitro findings (Fig. 3b), there was strong upregulation of 2’, 5’-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) family genes, including the OAS activated RNASEL, in NHP immunized with UNR formulations, with less pronounced upregulation observed in the MNR-treated group, indicating differences in the IFN-induced antiviral activity between the two mRNA formats. The expression of STAT2 48 h post-immunization revealed the ongoing transcription of IFN-induced genes, suggesting a common intracellular antiviral response to both UNR and MNR mRNA formats. Several genes known to contribute to mRNA degradation were heightened in the UNR group, including XRN1, XRN2, and certain LSM1-7 subunit genes associated with mechanisms leading to cytoplasmic RNA decay26. Additionally, two genes that code for pivotal translation initiation inhibitors EIF2AK2 (a dsRNA-dependent kinase impeding ternary complex turnover)27 and EIF4EBP1 (which competitively hinders the cap binding protein by blocking its eIF4G binding site)28 were upregulated. A more pronounced downregulation was observed in UNR-immunized NHP for various ribosomal proteins of both large and small subunits along with numerous translation initiation factors, including eIF4 components, the gamma subunit of the eIF2 ternary complex, and the alternative ternary complex eIF2A. Our RNA sequencing data indicated that mRNA modification-dependent transcriptional signatures were present in NHP blood, with UNR mRNA-LNPs inducing stronger activation of interferon-stimulated genes and other innate immune pathways compared to MNR mRNA-LNPs. Attenuation of innate immune activation with m1ψ modification was consistent with reduced translational repression. These findings provide strong, physiologically relevant evidence that the differential effects of mRNA modification on translation and immune sensing observed in HSKM cells are recapitulated in vivo in a complex immune milieu.

Heatmap providing a set of genes representative of the translation and mRNA degradation pathways in the whole blood collected from non-human primates 2 days post-immunization. Heatmap color scale represents log2 fold change of Day 2 over pre-immunization (baseline) levels. Hierarchical clustering was performed using the Euclidean distance measurement.

Discussion

mRNA-based vaccines have exhibited significant promise as evidenced by the clinical success of COVID-19 vaccines29,30,31. Substituting uridine with 5-methylcytidine or N1-methylpseudouridine is known to preserve antigen expression by preventing the activation of innate immune mechanisms that compromise mRNA stability and translation32. While it is also well known that the use of modified mRNA resulted in a reduction in the innate and antiviral immunity, improvements in mRNA purification and the removal of dsRNA contaminants have also led to improvement in protein expression for unmodified mRNA underscoring the importance of purification in modulating RNA immunogenicity21,33,34. Additionally, ionizable amino lipids, crucial for intracellular delivery11 can also stimulate innate immune response to the degree that they function effectively as vaccine adjuvants35,36. We coupled preclinical animal models with in vitro cell culture systems to understand the biological activity of mRNA vaccines with an aim to enhance expression, immunogenicity, and improve the safety profile of next-generation mRNA vaccines. Our work demonstrates the possibility of using preclinical data to model and select effective mRNA vaccine designs that could potentially de-risk clinical studies.

A major determinant of mRNA vaccine performance is the efficient translation of mRNA by ribosomes as each mRNA copy can produce multiple polypeptides based on their respective polysome valency37,38. While our protein expression data delineates mRNA modification- and lipid-dependent effects in vitro, other variables such as codon usage, GC content, impurities and secondary structure can all interplay with the effects of chemical modification possibly resulting in differential translation efficiency, altered mRNA stability, or differences in cellular signaling. We have attempted to further evaluate mechanistic drivers of mRNA-LNP performance for one sequence using in vivo models. Future works are needed to systematically evaluate all variants in vivo to elucidate how immune activation and tissue-specific translation influence these outcomes.

Higher induction of anti-viral genes OAS, MX1 and IFIT in cells treated with UNR Sing16 HA mRNA as compared to MNR was observed (Fig. 3a). This supports previous reports that m1ψ-modified mRNA improves stability and reduces innate immune response activation, leading to enhanced protein expression39. Interestingly, findings from Melamed et al. demonstrated that modified mRNA in cKK-E12 LNPs showed the least difference in enhancing mRNA translation and reducing innate immunogenicity similar to our results with the same LNP formulation when compared to the other formulations used. PCA based on GSVA-derived enrichment scores resulted in a clear separation of the buffer/SM-102 from cKK-E10/OF-02 across PC1 and PC2 at 4 h post-transfection (Fig. 3b), possibly due to differential uptake kinetics for SM-102. In concurrence with our in vitro findings, higher levels of genes that lead to translational repression were observed in UNR Sing16 HA-vaccinated NHPs (Fig. 9). In addition to PKR, which inhibits translation upon the delivery of exogenous RNA40, vaccination with unmodified mRNA-LNPs led to strong upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes, particularly the OAS family and RNASEL, compared to modified mRNA-LNPs. This indicates more robust activation of antiviral pathways and RNA degradation mechanisms in the UNR group, consistent with increased translational repression. The upregulation of STAT2 and other IFN-induced genes in both UNR and MNR groups demonstrates that both mRNA formats can trigger innate immune responses, but the response is more pronounced with UNR mRNA. The specific increase in genes like XRN1, XRN2, and LSM1-7 in the UNR group further supports the conclusion that unmodified mRNA is more susceptible to degradation and translational repression in vivo. As expected, MNR vaccination resulted in less downregulation of ribosomal proteins and translation factors and reduced upregulation of translational inhibitors EIF2AK2 and eIF4E-BP1 (Fig. 9). Additionally, mTOR and AKT41,42, both key regulators of global translation, were downregulated in the UNR-treated NHP.

Innate immune cells, crucial for defending against pathogens, utilize PRRs such as TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, RIG-I, and MDA-5 to detect foreign RNA. Our study of the impact of N-1methylpseudouridine modification on the production of early innate cytokines demonstrated species-dependent cytokine induction with improved responses in NHPs, but not in mice. While both mice and NHPs produced detectable IFNγ after immunization with mRNA vaccines, consistent with published findings9, only NHPs showed an improved response upon mRNA modification (Fig. 6). Interestingly, there was also minimal impact of mRNA modifications on immunogenicity in murine models for all LNPs tested. This may be due to species-specific differences in PRR expression/localization or immune response kinetics. Mice have a high tolerance to inflammatory stimuli via upregulation of anti-inflammatory IL-1RA which may partially explain the minimal impact of mRNA modification on inflammatory cytokine signatures43. A complimentary explanation may be that the cytokine signature observed in mice after administering the mRNA vaccine is partly due to effects of the LNP itself and thus is minimally impacted by mRNA modifications. Indeed, Chen et al. showed induction of several of the same cytokines (G-CSF, IL-2, IL-6, MIP1b, MCP1, IFNγ) when immunizing mice with empty LNPs44. In NHPs, MCP1 and IFNα were also induced after immunization with UNR Sing16 HA mRNA but substantially reduced by mRNA modification. Confirming previous in vitro observations from human PBMCs43, the production of IL-1RA on both the gene and protein level (Fig. 6b, c) was detectable in NHPs immunized with MNR Sing16 HA mRNA delivered in SM-102. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that mRNA modification can reduce the induction of innate cytokines, and these changes occur in a species- and LNP-dependent manner that necessitates careful experimental planning and data interpretation. T cell and B cell priming after mRNA vaccination have described to occur primarily in the draining lymph nodes, where antigen-presenting cells present vaccine-derived antigens to lymphocytes, initiating adaptive immune responses45 and the composition of LNPs and the chemical structure of the mRNA payload are both critical in shaping the early innate immune environment and the efficiency of antigen expression in these lymph nodes. Both LNP composition and mRNA chemistry are critical in determining the magnitude and quality of early innate activation and antigen expression in draining lymph nodes after mRNA vaccination and these early events can be highly predictive of the subsequent antibody and T cell response. Optimizing LNP and mRNA design to balance innate activation with efficient antigen expression is thus essential for improving mRNA vaccine performance.

Our data also highlights the differential effect of the LNP composition on immune activation. In NHPs, the UNR SM-102 formulation showed increased expression of interferon-regulated genes when compared to the cKK-E10 LNP (Fig. 8). Transcriptome analysis indicated that SM-102 formulations upregulated ISGs, which play a role in blocking viral replication and propagation46. Inflammasome pathways were more upregulated by SM-102 formulations compared to cKK-E10 as indicated by increased expression of IL-18, IL-1, IL-12, TRAF6, and others47,48. Previous literature suggests that certain LNP formulations, particularly those encapsulating mRNA, can act as built-in adjuvants during mRNA vaccination by engaging innate immune receptors such as the NLRP3 inflammasome, TLRs, and MDA-5, which can lead to the production of cytokines including IL-1β, IFN-γ, and IL-649. However, evidence for uniform activation of these pathways by all LNP types, especially empty LNPs, remains limited. Our data demonstrated that the modification of mRNA was able to silence the innate immune signatures more efficiently with cKK-E10 than with SM-102 LNP highlighting differential impacts of LNP design on vaccine performance. However, the bioactivity of an LNP-encapsulated mRNA may not necessarily be predicted based on the sum of its parts due to interdependencies among the components5. For example, the structural and compositional rearrangement of mRNA-LNPs are affected by their microenvironment, which can affect their biodistribution50, while the sequence, size and shape of RNA nanoparticles are known to have differential effects on immunogenicity51. Whether these effects are species-dependent or if they impart differences to long-term memory responses or to diversity of B cell receptor repertoire remains to be determined. The use of a multimodal framework spanning the biological and immunological hierarchy with in-depth characterization of vaccine components will be pivotal for optimal vaccine design. These studies aimed to provide a better understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that provoke immune responses from each customized vaccine to achieve a beneficial balance between immunogenicity and reactogenicity.

Methods

mRNA-LNP preparation and characterization

Full-length codon optimized non-replicating mRNAs from A/Singapore/INFIMH160019/2016 Influenza virus H3 Hemagglutinin (Sing16 HA) and four other influenza strains, A/Wisconsin/588/2019 (Wisconsin HA), A/Tasmania/503/2020 (Tasmania HA), B/Washington/02/2019 (Washington HA) and B/Austria/1359417/2021 (Austria HA), were synthesized enzymatically using unmodified (UNR) or m1Ψ-modified (MNR) ribonucleotides. GenBank accession number(s) for the nucleotide sequence(s) used are described in Supplementary Table 2. mRNA transcripts were synthesized by in vitro transcription employing SP6 RNA polymerase with a plasmid DNA template encoding the desired gene using modified or unmodified nucleotides. The resulting Qiagen column (RNeasy Maxi Kit (12) Cat. No. / ID:75162) purified precursor mRNA was processed further for an enzymatic addition of a 5’ Cap structure (Cap 1) and a 3’ poly (A) tail before purification. All mRNA preparations were analyzed for purity, integrity, and percentage of Cap1 before storage at −20 °C. All mRNA preparations had > 95% of 5‘ Cap1 and showed a single homogenous peak on capillary electrophoresis with % RNA integrity >77% (Supplementary Table 1). The double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) levels were measured using a validated sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. A dsRNA ladder (New England Biolabs, N0363S) as reference and the mouse monoclonal anti-dsRNA IgG2a (clone K1) to capture the dsRNA were used. Our data aligned with published findings that nucleoside-modified mRNA significantly reduces dsRNA content compared to unmodified mRNA6. Overall, the dsRNA levels in our mRNA preparations were in the same range as previously described reference clinical benchmarks53.

mRNA-LNP formulations were prepared by appropriate mixing solutions of mRNA and lipid mixture. Three types of cationic lipids were used for this study: OF-02 (synthesized at Sanofi), cKK-E10 (synthesized at Sanofi) and SM-102 (synthesized at Organix Inc.) lipid. All three LNP formulations had comparable lipid /mRNA ratio with the total lipid amount per mg of mRNA in the range of 21-24 mg/ml. Key LNP components (molar ratios) for DMG-PEG2k: Cholesterol:helper lipid were 1.5:50:38.5:10 for OF-O2 & cKK-E10 and 1.5:40:28.5:30 for SM-102. Briefly, an ethanolic solution of a mixture of lipids (ionizable lipid, helper lipid, cholesterol, and polyethylene glycol-lipid) at a fixed lipid and mRNA ratio were combined with an aqueous buffered solution of target mRNA at an acidic pH under controlled conditions to yield a suspension of uniform LNPs54. Upon ultrafiltration and diafiltration into a suitable diluent system, the resulting nanoparticle suspensions were diluted to final concentration, filtered, and stored frozen at −80 °C until use. The total mRNA encapsulated in the LNP was measured by the RiboGreen™ assay and was used to calculate the representation of the different mRNAs used. mRNA cap % was measured using Agilent 1290 Infinity II UHPLC/ 6530 QTOF with MassHunter B.09.00 (Agilent Technologies). The mRNA-LNP formulations were also characterized for size, percentage encapsulation and were stored at −80 °C at 1 mg/mL until further use. LNP size, polydispersity measurements were performed on Zetasizer 7.11 (Malvern Panalytical) and % encapsulation was determined with RiboGreen assay measured using Spectramax M5 with SoftMax Pro 5.4 (Molecular Devices).

mRNA-LNP formulations were prepared by mixing the various lipid components with mRNA under controlled conditions and at fixed ratios. All mRNA-LNPs exhibited ≥ 90% encapsulation with uniform hydrodynamic radius ranging from 95-120 nm and a polydispersity index of 0.106 to 0.12 for cKK-E10, 0.084 – 0.1 for OF-02, and 0.116 to 0.145 for SM-102 LNPs.

Mammalian cell culture and transfection

Primary human skeletal muscle myoblasts were obtained from Lonza (Cat. No. CC-2580) and thawed and expanded following vendor recommendations. Briefly, cryopreserved cell stocks were thawed into SkGM-2 complete media (Lonza, Cat. No. CC-3245). Media was replaced 24 h after thawing and every 48 h thereafter. Cells were expanded/passaged to P6, at which point they were seeded on 24-well culture plates pre-coated with Collagen 1 at a density of 24,000 cells/cm2 in 1 mL of culture media. The next day, media in each well was replaced with 0.5 mL of fresh media before transfection mixes were prepared. The cells were transfected at doses mentioned in the figure legends(1 μg to 10 μg of mRNA-LNPs transfected per million cells), followed by immunofluorescence imaging or puromycin assays as described below. For RNA-Seq, the cells were transfected at 2 µg of formulated RNA/million cells. For each treatment, 50 µL of transfection mix was added to the culture before an additional 0.5 mL of media was added to thoroughly distribute the transfection mixture before plates were returned to the incubator for 1, 4, or 24 h. At each collection time-point, media was aspirated, and cultures were lysed on-plate using 350 µL of RLT buffer (Qiagen Cat. No. 79216) and immediately transferred to 1.5 mL tubes and stored at −80 °C.

Human peripheral blood-derived immature dendritic cells (hDC) were purchased from STEMCELL Technologies (Cat. No. 200-0370, Lot Nos. 2401405007; 2401419004; 2311403010). Thawed cells were added into pre-warmed culture media (RPMI media supplemented with 1% v/v penicillin/streptomycin and 10% v/v HI-FBS) and allowed to rest at 37 °C for 3–4 h. Cells were pelleted at 500 × g/5 min, decanted, and resuspended to one million viable cells/mL. LNP formulated mRNA test article was diluted in the storage buffer. hDCs were transfected with 5 μg/million cells in a U-bottom 96-well plate in 100 μl media. After gentle mixing, the plate was placed in a 37 °C incubator for 24 h before downstream flow cytometry analysis.

Immunofluorescence

LNP transfected HSKM cells were washed twice with PBS (Corning; Cat. No 21-040-CV). Cells then were fixed in situ with 4% paraformaldehyde (Thermo Scientific; Cat. No AAJ61899AK) for 10 min at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with 0.004% Digitonin (Thermo Scientific; AC407565000) in PBS for 20 min. Cells were washed thrice with PBS, blocked with 10% goat serum (Gibco; 16210-072) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with Flu anti-H3 (H3N2) antibody (Immuno-Technology; Cat. No IT-003-004M2, 1:200 dilution), CL-1000117 antibody for Wisconsin (Sanofi generated, 10 ng/µL), CL-1000476 antibody for Tasmania (Sanofi generated, 0.5 ng/µL), CL-1000928 antibody for Washington and Austria (Sanofi generated, 20 ng/µL) in 10% goat serum, at 4 °C overnight.

Next day, cells were washed thrice with PBS and incubated with goat anti-mouse AlexaFluor™ 647 -conjugated secondary antibody (Abcam; Cat. No. AB150115, 1:1000 dilution) or goat anti-human AlexaFluorTM 647-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Cat. No A21445, 1:1000) in 0.1% BSA in PBS, supplemented with Hoechst (Invitrogen; R37165) counterstaining dye for 1 h at room temperature. Secondary antibody mixture was washed with PBS and imaged in 200 µl PBS using a Revvity Opera Phenix cell imaging multimode reader. Fluorescence was quantitated using the Harmony imaging software as mean fluorescence intensity of Alexa647 signal.

Flow cytometry

Monocyte derived human dendritic cells (hDCs) were centrifuged at 1500 RPM for 5 min and the supernatant removed 24 h post-transfection. Cells were washed with 200 µl of staining buffer BioLegend, (Cat. No. 420201) and primary antibody (anti-H3) Immune Technology (Cat. No. IT-003-004M2) was diluted to 10 µg/mL in staining buffer (1:100). 100 µl of diluted antibody was added to cells and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. The cells were washed with 100 µL staining buffer per well. The cells were stained with secondary antibody (anti-mouse-PE) 2 µg/mL (1:250) Southern Biotech (Cat. No. 1030-09) and LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Near-IR Dead Cell Stain Kit (1:1000) Invitrogen (Cat. No. L34976). The cells were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C, protected from light. After incubation the cells were washed and 200 µL of fixation buffer was added. The cells were incubated for 10 min at 4 °C, washed and run on a Cytek Aurora. The expression of HA and iMFI was determined using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

Puromycin incorporation assay

HSKM cells were plated the day before transfection at 0.25 million cells/well in 6-well plates. Cells were transfected with 2-fold dose curves of UNR and MNR Sing16 mRNA formulated in cKK-E10 or OF-02 LNPs from 10 µg/million cells to 1.25 µg/million cells. 20 h post-transfection control cells were treated with 100 µg/ml cycloheximide for 2 min at 37 °C. All cells were then treated with 10 µg/mL puromycin for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were harvested and lysed in 125 µL RIPA buffer with 1X HALT protease inhibitors. 15 µL of protein sample were combined with 5 µL of NuPAGE LDS sample buffer with reducing agent and incubated at 85 °C for 5 min. Samples were run on 8-16% SDS-PAGE at 185 V for 75 min and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes with a Biorad TransBlot Turbo system. Blots were blocked with 5% milk in tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h at room temperature, then stained overnight with mouse anti-puromycin antibody (12D10) and Licor rabbit anti-actin in 1% milk in TBS with Triton™ X-100 (TBST) overnight at 4 °C. Blots were washed 3 times for 5 min each with TBST then secondary stained with Licor donkey anti-mouse 800 and goat anti-rabbit 680 for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were washed 4 times for 5 min each with TBST then scanned on a Licor Odyssey imager.

Immunogenicity in mice and serological evaluation in NHP

For immunogenicity studies, n = 8/treatment group of female BALB/c mice (Mus musculus) were immunized with 50 μL of vaccine via the intramuscular (IM) route in the quadriceps under isoflurane anesthesia. Mice were administered on the right hind leg on Day 0 and on the left on Day 21. Blood was collected from mice via submandibular bleeds pre-study and Day 21 and by a terminal cardiac puncture on Day 35. Blood samples were collected into SST™ tubes and allowed to clot for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were centrifuged for 5–10 min and serum was stored at −80 °C until evaluated by HAI for antibody titers.

Naive male and female Mauritius origin cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) were selected from the Sanofi NHP colony at the NIRC. Animals weighed > 2 kg and were > 2 years of age at the start of the studies. Per NIRC SOPs, all animals underwent a pre-study health assessment performed by a licensed veterinarian, which included a complete blood count and clinical chemistry analysis before being cleared for entry into the study. NHPs were randomized (stratified randomization approach based on age, body weight, and sex by biostatistician) into groups of 4–6 per treatment group, were generally housed in pairs whenever possible and acclimated for at least 6 days prior to the start of the study. All NHPs were immunized with a dose of 0.5 mL of vaccine via the intramuscular (IM) route in the right forelimb on Day 0 and the left forelimb on D28 while under 10 mg/kg ketamine HCl /1 mg/kg acepromazine sedation. NHPs were bled using femoral venipuncture for serum collection while under anesthesia on Days -6, 2, 7, 14, 28, 30, 35, 42, 56, 90, 180, and 365 using to BD Vacutainer SST gel tubes. Serum was separated by centrifuging the tubes at room temperature for 10 min and the serum was aliquoted into labeled cryovials (0.5 mL/vial) and stored at ≤ -20 °C until use. Select serum sample timepoints were evaluated in the HAI assays for antibody titers and others were used to measure serum cytokine levels. The selection of the 48-h timepoint in our study was primarily influenced by two factors: first, restrictions imposed by animal ethics protocols, which limited the frequency and volume of blood sampling permissible in NHPs; and second, our intention to harmonize sampling schedules with those used in parallel clinical trials to enhance the translational relevance of our findings.

Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay

HAI assays were performed as previously described55 using the A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016 (H3N2) virus stocks produced in embryonated chicken eggs by Microbiologics. Receptor destroying enzyme (RDE) was used to treat sera samples at a one-to-three serum: RDE ratio and incubated overnight in a 37 °C water bath. The RDE was inactivated by a 30 min incubation at 56 °C samples were brought up to a final dilution of 1/10 by the addition of 6 parts 0.5% turkey red blood cells (tRBCs). After a 45 min incubation at room temperature, the samples were centrifuged to pellet the tRBCs and the RDE-treated sera samples were transferred to fresh tubes.

HAI assays were performed in V-bottom 96-well plates by adding 4 hemagglutination units per 25 μL (HAU/25 μL) of virus to 25 μL RDE-treated sera samples that have been 2-fold serially diluted across the plate. 50 μL of tRBCs were then added to the plate and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The HAI titer was recorded as the highest serum dilution that completely inhibits hemagglutination.

Cytokine profiling using Luminex

Mice were bled pre-study to obtain a baseline sample and then bled 24 h post-priming. NHPs were bled pre-study to obtain a baseline sample and then bled 48 h post-priming and 48 h post-boosting. Blood samples were collected into SST tubes and centrifuged 5–10 min to separate the serum, which was stored at −80 °C until use. For mice, cytokine analysis was performed using a Milliplex mouse cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead kit (Cat. No. MCYTMAG-70K-PX32) following manufacturer’s protocol. For NHPs, cytokine analysis was performed using a Procarta NHP cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead kit (Cat. No. EPX370-40045-901) following manufacturer’s protocol. Pre-study baseline levels were subtracted from post-priming (mice and NHPs) and post-boosting (NHPs only) levels, processed to determine log2 fold change, and graphed.

Gene expression profiling using Transcriptomics

RNA-seq extraction and library generation

Total RNA was extracted from whole blood NHP samples collected in PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes (Qiagen, BD Diagnostics) pre- and 2 days post-immunization using the MagMAX™ for Stabilized Blood Tubes RNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen) on an automated KingFisher Flex System (Thermo Scientific). The quality and yield of RNA were assessed on the 4200 TapeStation System (Agilent) and NanoDrop™ Eight Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Sequencing libraries were then prepared using the Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero Plus kit and sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 Sequencing System (Illumina) using the S4 Reagent Kit v1.5 (200 cycles).

Bulk RNA-seq processing

The bcl files were demultiplexed using Illumina’s bcl2fastq software. The fastq files were processed using Array Studio software (Qiagen) and aligned to the cynomolgus Macaque CynoWashU2013 reference genome with the WashUGene2017512 gene model. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using the Limma-Voom method, which transforms the raw read counts into log-counts per million (log-CPM) and models the mean-variance relationship of the data.

RNA-seq pathway analysis

To test for enrichment of biological pathways, the differentially expressed genes for each treatment contrast were analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software program (Qiagen), which reports enrichment as p-values from Fisher’s exact test.

Statistical analyses

A linear mixed model was used to account for the repeated measurements for each subject over time. The dependent variable, expressed as the change of HAI titers from baseline in log10 scale, was modeled separately for each LNP in the mouse study. The fixed effects included nucleoside modification type, time, dosage, and their interaction terms. For the NHP study, the model was expanded to include both the specific LNP and its interaction with the aforementioned factors, facilitating an evaluation of the LNP specific nucleoside modification effects at different dosages and time-points. For non-responders, an arbitrary minimum value of 5 HAI units was attributed. All analyses were done on R v4.2.3®.

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were carried out in compliance with all pertinent US National Institutes of Health regulations and were conducted with approved animal protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at BIOQUAL Inc. Rockville, MD (IACUC Number: 21-14) and New Iberia Research Center, University of Louisiana Lafayette (NIRC) (IACUC Number: 2020-8733-013). Housing and handling of animals were performed in accordance and compliant with the standards of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, the Animal Welfare Act as amended, and the Public Health Service Policy. The studies adhered strictly to applicable Standard Operating Procedures of BIOQUAL and NIRC approved IACUC protocol. Euthanasia was performed in accordance with standard procedures. For mice, the terminal blood collection was carried out using isoflurane anesthesia. Once the animal ID was confirmed, the animal was placed into the induction chamber. The vaporizer was turned on, and the O2 flow meter was set to a minimum of 1 L/min. The vaporizer was adjusted to ≤4% for anesthesia (or higher if needed), to ensure the animal was properly anesthetized. The depth of anesthesia was verified via toe pinch. After the terminal bleed, the animals were euthanized through deep anesthesia (with isoflurane administered at 5%) followed by a secondary euthanasia method (either thoracotomy and/or cervical dislocation). This process ensured that the animals were humanely euthanized and that the necessary samples were collected in line with the study protocol.

NHP studies were performed at the NIRC. Treatment of NHPs was in accordance with standard operating procedures at NIRCs, which adhere to the regulations outlined in the United States Department of Agriculture Animal Welfare Act (9 CFR, Parts 1, 2 and 3) and the conditions specified in The Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals52.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the article. GenBank accession codes for protein and mRNA sequence for influenza hemagglutinins used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table 2. The RNA sequencing data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE303153 (GEO Accession viewer). Any specific information on NHP transcriptome and unique reagents can further be obtained upon request.

References

Gu, Y., Duan, J., Yang, N., Yang, Y. & Zhao, X. mRNA vaccines in the prevention and treatment of diseases. MedComm (2020) 3, e167 (2022).

Jain, S., Venkataraman, A., Wechsler, M. E. & Peppas, N. A. Messenger RNA-based vaccines: past, present, and future directions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 179, 114000 (2021).

Chaudhary, N., Weissman, D. & Whitehead, K. A. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 817–838 (2021).

Watson, O. J. et al. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1293–1302 (2022).

Bitounis, D., Jacquinet, E., Rogers, M. A. & Amiji, M. M. Strategies to reduce the risks of mRNA drug and vaccine toxicity. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-023-00859-3 (2024).

Karikó, K., Buckstein, M., Ni, H. & Weissman, D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 23, 165–175 (2005).

Kobiyama, K. & Ishii, K. J. Making innate sense of mRNA vaccine adjuvanticity. Nat. Immunol. 23, 474–476 (2022).

Karikó, K. et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol. Ther. 16, 1833–1840 (2008).

Arunachalam, P. S. et al. Systems vaccinology of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in humans. Nature 596, 410–416 (2021).

Rosenblum, H. G. et al. Safety of mRNA vaccines administered during the initial 6 months of the US COVID-19 vaccination programme: an observational study of reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and v-safe. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 802–812 (2022).

Hafez, I. M., Maurer, N. & Cullis, P. R. On the mechanism whereby cationic lipids promote intracellular delivery of polynucleic acids. Gene Ther. 8, 1188–1196 (2001).

Hassett, K. J. et al. Optimization of Lipid Nanoparticles for Intramuscular Administration of mRNA Vaccines. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 15, 1–11 (2019).

Connors, J. et al. Lipid nanoparticles (LNP) induce activation and maturation of antigen presenting cells in young and aged individuals. Commun. Biol. 6, 188 (2023).

Lonez, C., Vandenbranden, M. & Ruysschaert, J. M. Cationic liposomal lipids: from gene carriers to cell signaling. Prog. Lipid Res. 47, 340–347 (2008).

Lonez, C., Vandenbranden, M. & Ruysschaert, J. M. Cationic lipids activate intracellular signaling pathways. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64, 1749–1758 (2012).

Alameh, M. G. et al. Lipid nanoparticles enhance the efficacy of mRNA and protein subunit vaccines by inducing robust T follicular helper cell and humoral responses. Immunity 54, 2877–2892.e2877 (2021).

Vlatkovic, I. Non-Immunotherapy Application of LNP-mRNA: Maximizing Efficacy and Safety. Biomedicines 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9050530 (2021).

Dong, Y. et al. Lipopeptide nanoparticles for potent and selective siRNA delivery in rodents and nonhuman primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3955–3960 (2014).

Fenton, O. S. et al. Bioinspired alkenyl amino alcohol ionizable lipid materials for highly potent in vivo mRNA delivery. Adv. Mater. 28, 2939–2943 (2016).

Buschmann, M. D. et al. Nanomaterial delivery systems for mRNA vaccines. Vaccines 9, 65 (2021).

Hassett, K. J. et al. mRNA vaccine trafficking and resulting protein expression after intramuscular administration. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 35, 102083 (2024).

Rohde, C. M. et al. Toxicological assessments of a pandemic COVID-19 vaccine-demonstrating the suitability of a platform approach for mRNA vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020417 (2023).

Kauffman, K. J. et al. Efficacy and immunogenicity of unmodified and pseudouridine-modified mRNA delivered systemically with lipid nanoparticles in vivo. Biomaterials 109, 78–87 (2016).

Polack, F. P. et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med 383, 2603–2615 (2020).

Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med 384, 403–416 (2021).

Houseley, J. & Tollervey, D. The many pathways of RNA degradation. Cell 136, 763–776 (2009).

Wek, R. C. Role of eIF2alpha kinases in translational control and adaptation to cellular stress. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 10 https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a032870 (2018).

Haghighat, A., Mader, S., Pause, A. & Sonenberg, N. Repression of cap-dependent translation by 4E-binding protein 1: competition with p220 for binding to eukaryotic initiation factor-4E. EMBO J. 14, 5701–5709 (1995).

Barbier, A. J., Jiang, A. Y., Zhang, P., Wooster, R. & Anderson, D. G. The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 840–854 (2022).

Lee, I. T. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a phase 1/2 randomized clinical trial of a quadrivalent, mRNA-based seasonal influenza vaccine (mRNA-1010) in healthy adults: interim analysis. Nat. Commun. 14, 3631 (2023).

Carvalho, T. mRNA vaccine effective against RSV respiratory disease. Nat. Med 29, 755–756 (2023).

Schoenmaker, L. et al. mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability. Int J. Pharm. 601, 120586 (2021).

Clark, N. E. et al. Removal of dsRNA byproducts using affinity chromatography. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 36 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2025.102549 (2025).

Nelson, J. et al. Impact of mRNA chemistry and manufacturing process on innate immune activation. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz6893 (2020).

Pizzuto, M. et al. Cationic lipids as one-component vaccine adjuvants: a promising alternative to alum. J. Control Release 287, 67–77 (2018).

Bernard, M. C. et al. The impact of nucleoside base modification in mRNA vaccine is influenced by the chemistry of its lipid nanoparticle delivery system. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 32, 794–806 (2023).

Roy, B. & Jacobson, A. The intimate relationships of mRNA decay and translation. Trends Genet 29, 691–699 (2013).

Svitkin, Y. V. et al. N1-methyl-pseudouridine in mRNA enhances translation through eIF2α-dependent and independent mechanisms by increasing ribosome density. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 6023–6036 (2017).

Melamed, J. R. et al. Lipid nanoparticle chemistry determines how nucleoside base modifications alter mRNA delivery. J. Control Release 341, 206–214 (2022).

Cesaro, T. & Michiels, T. Inhibition of PKR by viruses. Front Microbiol. 12, 757238 (2021).

Heberle, A. M. et al. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR regulation by stress. Mol. Cell Oncol. 2, e970489 (2015).

Roux, P. P. & Topisirovic, I. Signaling pathways involved in the regulation of mRNA translation. Mol. Cell Biol. 38 https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.00070-18 (2018).

Tahtinen, S. et al. IL-1 and IL-1ra are key regulators of the inflammatory response to RNA vaccines. Nat. Immunol. 23, 532–542 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Lipid nanoparticle-mediated lymph node-targeting delivery of mRNA cancer vaccine elicits robust CD8(+) T cell response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2207841119 (2022).

Lee, Y. et al. Immunogenicity of lipid nanoparticles and its impact on the efficacy of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. Exp. Mol. Med 55, 2085–2096 (2023).

Yang, E. & Li, M. M. H. All about the RNA: interferon-stimulated genes that interfere with viral RNA processes. Front Immunol. 11, 605024 (2020).

Alcorn, J. F. et al. Differential gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from children immunized with inactivated influenza vaccine. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 16, 1782–1790 (2020).

Lee, H. K. et al. Robust immune response to the BNT162b mRNA vaccine in an elderly population vaccinated 15 months after recovery from COVID-19. medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.08.21263284 (2021).

Lee, Y., Jeong, M., Park, J., Jung, H. & Lee, H. Immunogenicity of lipid nanoparticles and its impact on the efficacy of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 2085–2096 (2023).

Sebastiani, F. et al. Apolipoprotein E binding drives structural and compositional rearrangement of mRNA-containing lipid nanoparticles. ACS Nano 15, 6709–6722 (2021).

Guo, S. et al. Size, shape, and sequence-dependent immunogenicity of RNA nanoparticles. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 9, 399–408 (2017).

Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Available at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/guide-for-the-care-and-use-of-laboratory-animals.pdf (2011).

Whitley, J. et al. Development of mRNA manufacturing for vaccines and therapeutics: mRNA platform requirements and development of a scalable production process to support early phase clinical trials. Transl. Res. 242, 38–55 (2022).

DeRosa, F. et al. Improved efficacy in a fabry disease model using a systemic mRNA liver depot system as compared to enzyme replacement therapy. Mol. Ther. 27, 878–889 (2019).

Chivukula, S. et al. Development of multivalent mRNA vaccine candidates for seasonal or pandemic influenza. npj Vaccines 6, 153 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support from our Flu project team at Sanofi, and particularly Maryann Giel-Moloney for generously providing us with critical reagents and viral stocks for performing HAI assays. We also want to thank the veterinary research staff, especially Dr. Emily Romero and Jason E. Goetzman, for their exceptional support of the in vivo phase of the NHP study at New Iberia Research Center, LA. We would like to thank Dr. Anpu Wang, Sanofi for helping with evaluating dsRNA content in our mRNA preparations. We would also like to thank the BIOQUAL Inc. staff, particularly Swagata Kar and Laurent Pessaint for their support of the in vivo phase of the mouse study. Finally, we thank our internal reviewer, Jean-Sebastien Boulduc for support in finalizing the manuscript. We thank the Innovation Communication Group, especially Nicola Donelan and Jessica Martin, for their editorial support of this manuscript. This research work was funded by Sanofi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hillary Danz, Allison Dauner and Shraddha Sharma have contributed to the conception of the study design, execution, and authoring of manuscript. Bin Lu, Mona Motwani, Ana Kume, Azadeh Bahadoran and Janhavi Nadkarni were involved in conducting in vivo studies and analyzing the immunological readouts, Mihaela Babiceanu and Andrew Kettring have performed the NGS studies and transcriptome analysis. Alisa Zhilin-Roth, Robert Jordan Ontiveros, Omkar Chaudhary, and Nicholas Clark have conducted in vitro protein expression and mRNA translation studies and written the respective sections with help from Eric Reyes, Catherine Khoo, Kara Gilbert. Christina Lee, Wei Zong, Alex Shumate, and Robert Amezquita have supported data analysis and visualization. Shrirang Karve, Anusha Dias, Monica Wu, Xiaobo Gu, Yanhua Yan have supported mRNA and LNP preparation. Frank DeRosa and Daniel Anderson have been expert consultants. Brian Schanen has supervised studies and reviewed the manuscript. Sudha Chivukula conceived, and supervised the studies, compiled, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors proofread and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The research is funded by Sanofi. Hillary Danz, Allison Dauner, Shraddha Sharma, Mihaela Babiceanu, Nicholas Clark, Robert Jordan Ontiveros, Robert Amezquita, Mona Motwani, Bin Lu, Alisa Zhilin-Roth, Eric Reyes, Catherine Khoo, Ana Kume, Azadeh Bahadoran, Janhavi Nadkarni, Omkar Chaudhary, Christina Lee, Wei Zong, Andrew Kettring, Alex Shumate, Shrirang Karve, Anusha Dias, Monica Wu, Xiaobo Gu, Yanhua Yan, Frank DeRosa, Brian Schanen and, Sudha Chivukula are employees of Sanofi and may hold stock in the company. Daniel Griffith Anderson receives research funding from Sanofi, is a Founder of oRNA Tx and receives compensation and equity from Combined Therapeutics.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Danz, H., Dauner, A., Sharma, S. et al. Synergistic effect of nucleoside modification and ionizable lipid composition on translation and immune responses to mRNA vaccines. npj Vaccines 10, 212 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01263-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01263-1