Abstract

The unprecedented evolution of educational technologies has transformed the learning landscape, creating distinct experiences in offline and online learning environments (OLE). However, little attention has been given to exploring students’ identities in the online learning context and how they can influence academic trajectories, limiting the development of a holistic understanding of the nature, effects, and areas of improvement in students’ identity formation in OLE. This study aims to investigate how students’ identity subcomponents differ among offline and OLE students via propensity score matching (PSM) in China, which allows us to find a doppelganger to estimate the counterfactual situation for making causal inferences in tandem with averting selection bias. Then, the study further examines how students’ identities affect motivation for learning achievement through OLS regression. PSM results indicate that goal-directedness, interpersonal relation, and self-acceptance were lower in students’ identity construction in OLE. Besides, all students achievement motivation shows that agency positively affects all students. Regarding the online learning environment, students’ agency and proactivity show negative effects on motivation. In contrast, goal-directedness indicates positive effects compared to the offline course students. Reflecting on these findings, this study offers instructional and online technology development implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ubiquitous access to digital technologies has dramatically changed the tertiary education landscape. In particular, it is undeniable that the lockdowns and the enforced closures of educational institutions due to the COVID-19 outbreak led many universities to adopt various practices and strategies of online learning to make their education delivery flexible and accessible to meet students' needs along with the in-class instruction. Higher education delivery modes are increasingly transitioning traditional face-to-face classes into entirely online, blended, or web-facilitated courses to meet the needs of diverse student populations. Consequently, there is a growing interest in exploring students’ online identities (Arfini et al., 2021; Daher & Awawdeh Shahbari, 2020).

From a sociocultural perspective, learning, knowledge, and identity are firmly interrelated; learning and knowledge construction are affected by contexts and cultures. Learning in this equation involves processes of identity formation; students not only acquire knowledge and skills but also become distinct learners in a unique learning community and environment (Cousin & Deepwell, 2005). It should also be noted that an individual student’s identity is ‘fluid’ rather than ‘static’ since it is socially constructed in a given context (Rogoff & Lave, 1984; Khalid, 2019). Considering that online classes are a social community like any other social group, to exist, interaction and participation among individuals is needed. One can hypothesize that via these interactions, students can generate new aspects of self, and therefore, new identities in online learning environments (OLE) emerge (Arfini et al., 2021; Delahunty et al., 2014). In this regard, Bati and Atici (2014) presented the term ‘Identity 2.0’, which they consider crucial for the new types of identities in online socialization. They revealed that students create and perceive different identities in their online learning practice. Similarly, Oztok et al. (2012) confirmed that individuals’ different identities significantly influence their online learning practices compared to offline learning.

Despite growing attention paid to understanding students’ perspectives and experiences of online learning and their identities within OLE, there has been a paucity of empirical research thoroughly examining the phenomenon of online identity. Existing research on students’ identity construction online mainly examines how individuals build their self-image online, particularly on social networking sites (Chen, 2017; Qin & Lowe, 2021); for instance, individuals tend to create their online identity with the disclosure of intimate information and the use of various web-based resources but rarely associate the learning context. Moreover, there is limited research that examines the differences between students’ identities in offline and OLE and how students’ identities in OLE affect academic trajectories, such as learning motivation.

This study, therefore, aims to examine whether online identity differences influence students’ learning achievement motivation and reveal the factors that make online and offline identities different and whether there is a significant difference in the impact of those factors depending on the learning environment (online versus offline). Although identifying factors that can predict online and offline identity may shed insights regarding effectively managing identities in online and offline learning contexts, these cross-contextual factors have been underexplored. Furthermore, examining the difference in the effects of those factors interplay between online and offline learning environments on learning achievement motivation may provide a comparative understanding of issues and difficulties in managing identities offline and online. Therefore, the findings of this study can provide meaningful implications for designing and implementing both online instruction and technology in an OLE that can promote positive identity development for students.

Literature reviews

Theoretical development of identity

The concept of identity has evolved significantly through various theoretical frameworks. Social Identity Theory (SIT) (Tajfel & Turner, 1978) is foundational, positing that individuals derive a sense of self from their group memberships, significantly influencing their behavior and perceptions. SIT underscores the role of social categorization in forming self-identity, which leads to in-group favoritism and out-group discrimination. It emphasizes the importance of in-group and out-group dynamics in shaping individual self-concept and social interactions (Hodson & Earle, 2017). SIT elucidates how students’ affiliations with various groups (e.g., class, school, peer groups) influence their self-concept and behaviors. Positive group dynamics and a strong sense of belonging can enhance students’ engagement and academic performance, whereas negative dynamics can adversely affect their self-esteem and learning outcomes (Hu et al., 2024).

Psychological theories are crucial for understanding college student identity formation during their critical developmental stage. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory provides a comprehensive framework for examining the multiple layers of influence on identity development, including microsystem (direct interactions), mesosystem (interactions between settings such as school and home), exosystem (larger social structures like education and culture), and macrosystem (sociocultural contexts) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). This theory highlights the interconnectedness of various environmental systems in shaping identity, particularly relevant for college students navigating transitions between adolescence and adulthood. The self-affirmation theory further complements this discussion by emphasizing how individuals actively affirm their identities through purposeful actions and thoughts (Steele, 1988). This perspective aligns with the developmental challenges confronting college students as they seek to establish a coherent sense of self in diverse social contexts. In addition, Erikson (1968)’s theory of lifespan development posits that at each developmental stage, individuals develop a new virtuous quality and identity by confronting and resolving conflicts. Building upon Erikson’s theory, Adams and Marshall (1996) highlight that identity development is not innate within one individual; identity occurs within socio-psychological processes. These theoretical perspectives have laid the groundwork for understanding how identity is constructed and maintained within different social contexts. In educational settings, the self-identity stage involves forming meaningful relationships with peers and mentors, which supports psychological well-being and academic success (Britt et al., 2022). Understanding these developmental stages helps educators create environments that foster self-exploration and supportive relationships (Li et al., 2024).

In recent years, the Reasoned Action Approach (RAA) has extended the understanding of identity by incorporating self-identity as a significant predictor of intentions and behavior. The RAA framework integrates attitudes, perceived norms, and perceived behavioral control to explain how identity influences behavior, especially in health-related contexts (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2009). Additionally, the Self-Acceptance and Identity Construction Model suggests that self-acceptance mediates the relationship between values and identity expression, emphasizing the role of self-acceptance in authentic identity presentation in both offline and online environments (Edwards et al., 2019), indicating that higher levels of self-acceptance lead to more authentic and consistent identity expression. This model highlights that direct interactions provide immediate feedback and validation in offline settings, enhancing self-acceptance. Conversely, in OLE, the lack of face-to-face interaction can challenge self-acceptance, emphasizing the need for strategies that support students’ authentic self-expression in digital contexts (Wu & Carroll, 2024).

The identity development concept is a multifaceted process that has garnered significant attention in psychological and educational research. According to Lieberman & Schroeder (2020) and Hu et al. (2015), the digital age has introduced new dimensions to how individuals construct their identities, particularly among adolescents. Livingstone (2008) accentuates the role of digital media in identity formation and underscores both the opportunities for self-expression and the risks associated with negative feedback online. Patti et al. (2011) further explore how social media influences adolescents’ self-concept and identity development, while Davis (2012) examines the impact of digital communication on self-identity clarity. These theoretical frameworks emphasize that digital environments offer unique opportunities for self-exploration but also pose challenges related to authenticity and self-presentation. Borlee et al. (2024) note that online learning communities can foster identity shifts, transforming students from passive “knowledge receivers” into active “knowledge creators” or collaborative partners in the learning process. Conversely, challenges such as technology anxiety and difficulties in peer interaction may lead some students to adopt roles as “class observers” or isolated learners, as noted by Gillett-Swan (2017) and Davidson (2015).

Differences in students’ identity in offline and OLE

In contrasting student identities between offline and online learning environments, it becomes evident that each context offers distinct experiences. Many studies highlight significant differences in how students form and maintain their identities offline versus OLE. Studies found that students in online learning environments often experience greater autonomy but may struggle with feelings of isolation compared to their offline counterparts (Hew et al., 2023; Li et al., 2022). This isolation can negatively impact their self-acceptance and academic motivation. Other studies have shown that online learning environments can enhance certain aspects of identity, such as agency and goal-directedness, due to online courses’ flexibility and self-paced nature (Mairitsch et al., 2023). However, these environments also require students to be more proactive and self-regulated, which can be challenging for those who lack strong self-efficacy (Liao et al., 2024). There is a lack of scrutiny of the differences in students’ identities offline and in OLE among those dimensions of identity. It is imperative to examine whether there is any difference in each dimension of students’ identity to guide future instructional practices to support students’ identity in OLE.

Factors that influence identity formation

Existing literature shows five key factors that influence identity formation. First, self-acceptance involves recognising and accepting all aspects of oneself, including strengths and weaknesses (Dignan, 1965; Marsh & Martin, 2011; Tetzner et al., 2017). It is a fundamental aspect of self-concept and involves a realistic and subjective awareness of one’s attributes. Self-acceptance is crucial for psychological well-being, allowing individuals to embrace their authentic selves and maintain a positive self-image despite challenges (de Vaate et al., 2020). This concept is particularly relevant in offline and online environments, where individuals may face different pressures and expectations (Arıcak et al., 2015).

According to identity theory, agency reflects a person’s ability to achieve internalized goal states represented in identity standards despite changing or opposing environmental conditions. Therefore, agency is the capacity of individuals to act independently and make their own free choices, encompassing self-efficacy, self-regulation, and goal setting (Tsushima & Burke, 1999). This concept is crucial for understanding how individuals navigate their personal and academic lives, taking the initiative, and making decisions aligning with their goals and values (Mairitsch et al., 2023).

Goal-directedness refers to an individual’s ability to set, pursue, and achieve personal goals. It compasses planning, commitment, and perseverance—essential for successful identity formation and personal development (Dignan, 1965). Theoretical perspectives highlight that goal-directedness links to a clear sense of what one stands for and where one is going, reflecting self-assertion and the drive to achieve personal aspirations. This component of identity is vital for academic and personal success, as it guides individuals in pursuing meaningful objectives (Zhu et al., 2024a).

Proactivity is the tendency to take initiative and act in advance to achieve goals rather than reacting to events after they happen (Tsushima & Burke, 1999). It is an essential trait for adapting to and shaping one’s environment, involving anticipatory actions and taking control of situations. Proactivity is critical in educational and personal contexts, enabling individuals to effectively prepare for and navigate potential challenges (Zhu et al., 2024b). This concept underscores the importance of being forward-thinking and self-motivated in achieving success (Su et al., 2024).

Interpersonal Relations pertain to how individuals interact, communicate, and build relationships with others. Healthy interpersonal relations are crucial for identity development, providing a supportive environment for self-expression and acceptance (Arıcak et al., 2015; Dignan, 1965). Positive relationships with peers, mentors, and family members can enhance an individual’s sense of belonging and self-worth, integral to building a strong and coherent self-identity (Zhou et al., 2023).

Identity and achievement motivation

Another stream of prior research has shown that students’ identity in offline and OLE has a positive correlation with achievement motivations, which is defined as an individual’s desire to perform and accomplish difficult tasks, overcome obstacles, and reach a higher goal or seek success by winning competition with others in task performance (Wigfield et al., 2021). Studies by Eccles et al. (2004) explore how academic self-identity influences students’ motivation and performance, emphasizing the importance of a positive academic identity for educational success. Academic self-identity measures the aspect of an individual’s self-concept that relates to their academic abilities and achievements (Kristie-Lee et al., 2023). Motivation is the process that initiates, guides and sustains goal-oriented behaviors. Martin and Dowson (2009) focus on the motivational psychology of education, emphasizing the role of self-identity in driving students’ engagement and persistence in academic tasks. Similarly, Marsh and Martin (2011) investigated the relationship between academic self-concept and achievement, demonstrating that a positive academic self-identity links to higher academic performance. Recent findings extend this understanding to online learning environments, highlighting how self-identity interacts with digital learning experiences to impact student motivation and engagement (Bonfiglio et al., 2024; Jones & Norman, 2022).

Like identity has numerous sub-components, the literature also discusses key components of achievement motivations such as risk-taking, future time orientation, personal responsibility, self-efficacy, task-orientedness, and the interplay between identity and academic achievement. First, risk-taking is the willingness to engage in behaviors that involve uncertainty and potential adverse outcomes in pursuit of goals. It is a key component of achievement motivation because it involves the readiness to face uncertainty and take calculated risks to achieve success (Sagie et al., 1996). This construct highlights the importance of being willing to step out of one’s comfort zone and embrace challenges as opportunities for growth. As highlighted in recent educational research, fostering a culture that supports risk-taking and views failure as a learning opportunity is crucial for promoting creativity and innovation in students (Huo et al., 2023).

Second, future time orientation refers to how individuals consider and plan for future outcomes when making decisions. It reflects prioritizing long-term goals over immediate rewards for sustained achievement and personal development (Tongfei et al., 2022; Tsushima & Burke, 1999). Future time orientation is linked to goal-setting and perseverance, guiding individuals to achieve meaningful and long-term objectives (Lai et al., 2024).

Third, personal responsibility involves taking ownership of one’s actions and consequences, including a commitment to personal and ethical standards. It is a core component of self-regulation and ethical behavior, influencing individuals’ goals and achievements (Tongfei et al., 2022; Tsushima & Burke, 1999). Personal responsibility is crucial for maintaining integrity and accountability in personal and academic contexts, fostering a sense of control and agency in one’s life (McGrath et al., 2023).

Fourth, self-efficacy is the belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations. This concept, introduced by Bandura (1977), significantly influences motivation, as individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in challenging tasks and persist in the face of difficulties. Self-efficacy is foundational for achieving high performance and overcoming obstacles, playing a critical role in personal and academic success (Li et al., 2022; Liao et al., 2024).

Fifth, task-orientedness focuses on completing tasks efficiently and effectively, emphasizing achievement and performance. This construct links to goal-directedness and the ability to prioritize tasks, manage time effectively, and achieve high-performance standards (Sagie et al., 1996). Task-oriented individuals are driven by a clear sense of purpose and dedication to their work as an impetus for academic and professional success (Kim et al., 2024).

Research gaps and research questions

The literature review builds our understanding of the definition of identities and how identities are socially constructed; thus, students may have different identities offline and OLE. Furthermore, existing literature reveals the association between identity and achievement motivation. However, several research gaps remain. Existing studies often focus on specific aspects of identity, such as self-acceptance or agency. Still, there is a lack of comprehensive research examining how all sub-components of identity (i.e., agency, self-acceptance, goal-directedness, and proactivity) interact and differ between offline and online environments. Furthermore, while many studies have explored the impact of identity on academic achievement, there is limited research on how the current status of OLE influences students’ achievement motivation, including risk-taking, future time orientation, personal responsibility, and self-efficacy.

In examining the role of identity in academic achievement, it is crucial to recognize the multifaceted nature of identity and its varying expressions across different contexts. The selected subcomponents of identity—agency, self-acceptance, goal-directedness, and proactivity—are identified based on their relevance to academic success. However, it is discernible that these components may not be exhaustive or universally applicable, as cultural and individual differences can influence the significance of other aspects of identity. While existing literature highlights the association between identity and achievement motivation, there is a lack of comprehensive research on how these subcomponents interact and differ offline versus OLE. This gap is significant because understanding these interactions can provide valuable insights into the unique challenges and opportunities in OLE for identity formation. Future studies should aim to explore these dynamics more thoroughly. Further, the impact of OLE on students’ achievement motivation has been underexplored, particularly in areas such as risk-taking, future time orientation, personal responsibility, and self-efficacy. These aspects are crucial for academic success and adaptability, making them a ripe area for further investigation. When researching these factors, educators and policymakers can better support students navigating diverse learning environments. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the following two research questions:

RQ1. What is the difference between each sub-component (agency, self-acceptance, goal-directedness, and proactivity) of students’ identity in offline and OLE?

RQ2. How does student identity and OLE status quo relate to achievement motivation (risk-taking, future time orientation, personal responsibility, self-efficacy)?

Methodology

Data collection

This study targeted students enrolled in a seven-week Design Thinking and Research (LIF003) course between 1 November and 13 December 2023 at an international joint-ventured (Sino-British) research-led university based in Suzhou, China. This course was a part of elective liberal arts courses offered to every undergraduate student, without academic year and major/degree restriction. The class was an hour-long lecture and an hour-long group activity-based workshop built around the design thinking process and held twice a week for seven weeks (i.e., a 28 h course in total), delivered offline and online for flexible attendance. Those who signed up for the class online could only attend the course via the University’s online learning and teaching platform. This study received ethical approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board on September 9th, 2022 and informed consent from all participants via online survey in December 2023.

The survey consisted of 4 sections: participation consent, demographic information, identity questionnaire, and achievement motivation. The survey questionnaires regarding students’ identity consisted of the following five sub-components: 10 items for agency, nine self-acceptance items, eight goal-directedness items, nine proactivity items, and seven interpersonal relation items adapted from Marsh & Martin (2011), Edwards et al. (2019), and Simons (2020) and modified to match the context of this paper. Meanwhile, the achievement motivation questionnaires were adapted from Elliot et al. (2017), Gutiérrez-Braojos (2015), and Li et al. (2022). They included three items for each variable (risk-taking, future time orientation, personal responsibility, self-efficacy, task-orientedness) and slightly revised to consort the analysis context. The study employed a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly Disagree = 1, Strongly Agree = 5) questionnaire. Appendix 1-2 displays a detailed survey questionnaire.

The survey was conducted between 14 ~ 21 December 2023 after completing the coursework, targeting all students enrolled in the course regardless of learning environment. On the last day of the lecture, students were given a choice from either an online or paper survey to respond. All students voluntarily chose to participate in an online survey. In case of selection bias or self-perception may arise, we delivered the instructions on the last day of the class to consider their learning environment and reminded them while answering the survey. We also stressed the corresponding learning environment in the survey questionnaire by stating “during the offline course,” for offline students, “for the online course,” for online students. In the survey, students were asked to check their attendance type (i.e., offline or OLE) and responded to the same questionnaires. A total of 334 valid survey responses were retrieved for the analyses without any missing values. The demographic information shows that 88 students (26.3%) had participated in the class online, while 246 (73.7%) attended offline. Among them, 110 (32.9%) were male and 224 (67.1%) were female students, and their ages ranged from 18 to 28, with a mean age of 21.30. The average daily digital device usage for academic purposes was 203.2 min, lower usage than for non-academic purposes, 238.1 min (see Appendix 3).

Data procedure and analyses

Propensity score matching (PSM)

The gold standard in estimating treatments, exposures, and interventions on outcomes (hereafter treatments) is employing randomized controlled trials, to averts confounded status of the baseline characteristics of the collected data (Austin, 2011). Hence, the estimations of treatment effects on outcome can be ensured by directly comparing the treated and untreated (controlled) subjects (Greenland et al., 1999). However, the widespread use of nonrandomized data (i.e., surveys) has engendered selection bias that can influence the baseline characteristics of the subjects. Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983) introduced a conceptual statistical tool called a propensity score to draw valid causal inferences using observational data. The simple concept of propensity score methods is to find a doppelganger (i.e., control group; counterfactual) mimicking the treated subject (i.e., treatment group; factual) by matching the baseline characteristics of a subject. Propensity score methods help reveal ‘what would have occurred to those who received treatment if they had not?’

PSM estimates the average treatment effect (ATE) and the average treatment effect for the treated (ATT). The former estimates the average causal effects at the population level, whereas the latter focuses on the average causal effects on the subject who received the treatment. The researchers must decide whether the ATE or the ATT is of greater interest and suitable for the research context. For instance, if the researchers investigate the effects of English as a second language (ESL) writing programs, the ATT reveals the effects of the specific subject pool with non-native English speakers. On the other hand, if the researchers are interested in English writing programs for all school students, the ATE may be of greater interest than ATT.

Data analyses

The study examines the difference between students’ identity offline and OLE (RQ1), using an experimental approach in a natural setting. However, as an individual cannot appear online and offline (the counterfactual situation) at the same time, the natural environmental conditions cannot be fulfilled. For instance, students who took the course online could only attend the course through an online platform, so those students did not show up in offline lectures until the end of the course. As stated above, survey data may cause selection bias. Propensity Score Matching (PSM) was adopted to address potential selection bias (i.e., researchers’ selection of which student to attend OLE) from observational data (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983) and to draw convincing causal inferences (Lanza et al., 2013). The basic concept of PSM is to estimate the conditional probability of an observation value receiving treatment by considering the probable vector covariates and the confounding variables (Everitt & Skrondal, 2002).

PSM allows us to investigate the treatment effects of students’ identity in OLE, which means we can analyze if students in OLE have higher identity scores in terms of agency, self-acceptance, goal-directedness, and proactivity compared to the counterfactual circumstance. As mentioned above, the students in OLE are impossible to be in offline situations; hence, PSM seeks students offline having similar characteristics, the vector covariates, from the offline participant pool, discovering a doppelganger for students in OLE to reveal the identity differences in different learning environment. For the analysis, we divided the sample into two groups: the binary form of treatment variable ‘OLE,’ either student in OLE coded as OLE = 1 (the treated group) or offline as OLE = 0 (the control group).

To discover a doppelganger, the tallied propensity scores of the control group were utilized to match with the students in the treated group. The propensity scores based on the confounding variables (covariates) help address the investigation’s selection bias for further analyses, such as comparing the sub-component score differences (dependent variables) between two groups of students in different learning environments.

PSM analyzes the average treatment effect on the treated observations (ATT) as the treatment effects that estimate the sub-component differences of the population-level average effect. In this regard, ATT unveils the student-level average impact students in OLE in this paper. The second term of the following function indicates the counterfactual estimation of the treated group since ATT reveals the sub-component differences between the treated group and the virtual stance of the counterfactual circumstance of the same group by using resembling counterfactual samples.

To evaluate the group matching, we examined the covariate balance test in tandem with the balance plot – the density distribution of the propensity scores – to validate the satisfactory level of overlap necessary for doppelganger matching of the treated and control groups. The covariate balance test aims to reduce bias caused by confounders and ensure that treated and control groups are comparable for estimating treatment effects. In addition, we examined the variables using a 5-point Likert scale for their reliability, and identity sub-component (dependent) variables indicate a satisfactory level above the threshold of 0.70 (Cortina, 1993) (see Table 1).

In addition, the study employed ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis to reveal the causal relationship by using 3 models. Model 1 is a baseline model that consists of all samples to see the general effects of students’ identity variables on the achievement motivation variable. Then, the study conducted Model 2 that encompasses OLE as another independent variable to verify whether any different result occurs. Lastly, Model 3 consists of OLE as a moderator on the relationship between students’ identity and achievement motivation variables. In assessing the impact of students’ identity on achievement motivation (RQ2), among five achievement motivation variables, only risk-taking (CA = 0.72) and future time orientation (CA = 0.76) fulfilled the threshold of the reliability test, as shown in Table 2. Thus, the study eliminated personal responsibility (CA = 0.52), self-efficacy (CA = 0.37), and task-orientedness (CA = 0.43) for further analysis. The possible reason for reliability failure in three variables may be attributed to the cultural differences, since a significant portion of concepts were developed based on the Western questionnaires that may not align with Eastern cultural aspects. This limitation needs further assessment in future studies since this research is exploratory.

Results

PSM results

The treated group (students in OLE) consists of 88 students, whereas 246 students attended lectures offline, as shown in Table 3. The propensity scores of the two groups were compared to validate the PSM. First, research to assess whether the covariates are well matched in distributions, a covariate balance test (see Table 4) was conducted on continuous covariates (i.e., age, aca_hr, naca_hr). The results demonstrated a satisfactory level in meeting thresholds for standardized differences (less than 0.10; Normand et al., 2001) and variance ratio (close to 1.0 and between 0.5–2.0; Rubin, 2001). Then, as shown in Fig. 1, the balance plot portrays the different propensity scores of each group on the left side matched on the right side, which showed the score difference between groups dramatically diminished, indicating a satisfactory matching level for valid estimation of counterfactual observation for ATT.

The ATT of students’ identity in OLE (i.e., agency, self-acceptance, goal-directedness, proactivity, interpersonal relation) are summarized in Table 5. The results show that the students in OLE demonstrate 0.32 points lower in goal-directedness (p < 0.01); interpersonal relations of students in OLE exhibit 0.25 points lower (p < 0.05); and self-acceptance also shows 0.19 points lower (p < 0.05) compared to the students in offline lecture. These results indicate that goal-directedness, interpersonal relations, and self-acceptance contribute to composing the students’ identity, and students in OLE need to be taken care of by the instructors.

OLS regression results

For the estimation of the achievement motivation (i.e., risk-taking and future time orientation variables) effects, gender, age, the average digital device usage hour for academic purposes (aca_hr), and the average digital device usage hour for non-academic purposes (naca_hr) were used as control variables, In OLE, we employed five components of students’ identity and interactions and students’ identity components for independent and interactive variables in OLS regressions.

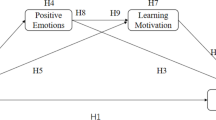

The achievement effects on risk-taking as an achievement motivation (see Table 6 and Fig. 2), the baseline of OLS regression estimation (Model 1; R2 = 0.42) shows that only agency (β = 0.719, p ≤ 0.001) has statistical effects, but when OLE comes in as another independent variable (Model 2; R2 = 0.42), OLE (β = -0.1385, p < 0.05), agency (β = 0.727, p ≤ 0.001), and goal-directedness (β = 0.147, p < 0.1) show statistical significance. Our final model (Model 3; R2 = 0.44) indicates that agency (β = 0.795, p ≤ 0.001) and proactivity (β = 0.250, p < 0.1) have statistical effects as a whole class. These results explain that all students in the course consider agency and proactivity as crucial motivation factors for achieving good grades. However, when it comes to interaction terms of OLE (i.e., 0=offline, 1=online) the findings reveal the moderating effects of OLE (Model 3) with five sub-components of students’ identity, agency (β = -0.3231, p ≤ 0.05) and proactivity (β = -0.37, p < 0.1) unraveled the negative relationship, while goal-directedness (β = 0.2793, p < 0.1) showed positive. These results suggest that students’ achievement motivations are 28 points higher in goal-directedness but 32 points and 37 points lower, respectively, in agency and proactivity for those who take courses online.

The achievement motivation effects on future time orientation (see Table 7), the baseline of OLS regression estimation (Model 1; R2 = 0.35), shows that only agency (β = 0.7088, p ≤ 0.001) has statistically significant effects as a whole class. Model 2 (R2 = 0.35) and Model 3 (R2 = 0.35) also show the statistical significance of the agency of all students (β = 0.7101, p ≤ 0.001; β = 0.7581, p ≤ 0.001, respectively). However, no moderation effect of OLE in Model 3 was found, indicating no difference between the two learning environments. In addition, Weak but still statistical significance of the average digital device usage hour for academic purposes (aca_hr) on future time orientation is revealed in all models (β = 0.0004, p < 0.1; β = 0.0004, p < 0.1; β = 0.0005, p < 0.1, respectively). Although these OLS models contribute to the literature, a discreet interpretation of the results is necessary as the effect size (R²) of the model is comparatively low.

Discussion

First, the study revealed that students in OLE show lower scores in goal-directedness, interpersonal relations, and self-acceptance compared to students in the offline class. Emerging evidence presents several concerns regarding students’ online learning experience during COVID-19, including depression and learning anxiety (Lee et al., 2021), decreased learning motivation (Bączek et al., 2021) alongside increased learning burdens (Niemi & Kousa, 2020), and limited collaborative learning opportunities (Lau & Jong, 2022). Consequently, a range of regulation competencies, including self-, co-, and shared regulation, are increasingly essential to students’ learning process, experience, and academic success in OLE (Lau & Jong, 2022). Accordingly, recent studies explore the use of emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) to support students’ regulated learning by analyzing and interpreting individual student’s regulation behaviors (Noroozi et al., 2019) as well as offering support that scaffolds complex regulated learning processes in OLE (Molenaar, 2022; Kim et al., 2025). Drawing on existing research, we recommend that online learning tool developers support students’ different modes of regulation during online learning processes through an in-depth understanding of the nature of online instruction and the position of students, instructors, and technologies. For instance, Jin et al. (2023) suggested that the degree of AI intervention should be adjusted according to the degree of the learner’s activeness; AI should take a more proactive role in supporting students regulated learning for those with low activeness, whereas AI should gradually decrease its intervention for the learners with higher activeness. Such interactive features and scaffolded feedback of AI could help students to build active learner identity and agency, taking an active role in their learning in OLE, by directing their learning tasks and goals, helping them clarify and elaborate their understanding of tasks during the learning process in OLE, and even analyzing and evaluating the quality of learning tasks and performance, their learning experiences (Jin et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2025).

Second, this study confirmed that students’ agency significantly and positively influences risk-taking and future time-orientedness of achievement motivation although personal responsibility, self-efficacy, and task-orientedness were discarded probably due to cultural differences. Earlier literature highlights that the affordances of internet technologies can create a learning space where students can safely test, experiment, fail, learn from failure, and iterate toward success (Cho et al., 2015). These promote foreground personal traits (e.g., adaptability, independent thinking skills, etc.) and contextual components for creative risk-taking and productive failure (Henriksen et al., 2021). Nonetheless, it should also be highlighted that online learning is not practical for every student. Studies have shown that an OLE that is freer and more open induces an increased risk of irrelevant features, which may detract from student learning and can be less beneficial than in-classroom instruction, especially for students with a lower level of agency (Blau & Shamir-Inbal, 2017). In line with this, Taub et al. (2020) found that students’ agency relates to their problem-solving behaviors in OLE, showing that students with more agency exhibit more self-regulated learning behaviors and express feeling more interested in the tasks compared to students with low or no agency as they are not able to exert control over their learning. It is necessary to include direct instruction/strategies (e.g., set specific learning goals and strategies to attain these goals, ongoing reflection) to activate students’ agency in the online learning curriculum. Earlier studies have also highlighted that students’ perceptions and the effectiveness of online learning can be improved by integrating agency training into the intervention (Lai & Hwang, 2016; Wang, 2011).

Furthermore, it was worth noting that students’ use of digital devices is significantly and positively related to their future time-orientedness and achievement motivation in online learning environments. These findings echo prior research highlighting that the effectiveness of technology for educational outcomes depends on how people use it, not simply having access to technology (Bavelier et al., 2010; Comi et al., 2017). Caton et al. (2022) report that students who effectively use technology for academic purposes, not for entertainment, such as reading articles, searching for specific information, and manipulating the available tools and technology to solve problems, have a higher level of cognitive flexibility, which allows students to face new and unexpected conditions in the online environment, restructure their knowledge adaptively as they navigate, select and incorporate new information into new knowledge. In this regard, it is crucial to foster students’ digital literacy and the ability to transfer personal digital technology use skills to educational practice to lead them to sort the information presented online effectively, (de)construct and synthesize new knowledge, and achieve learning goals. Authentic problem-based learning activities could be helpful to enhance students’ digital literacy. Students can improve their use of technology to adequately solve problems and develop deep knowledge in the learning domain (Caton et al., 2022; Cho et al., 2015).

Conclusion

While traditional offline learning environments have long been the norm, providing students with direct, face-to-face interactions that shape their academic and social identities, the rise of OLEs introduces new dynamics where digital interactions and virtual classrooms redefine the educational experience. Understanding these identity differences is paramount as it influences students’ engagement, motivation, and overall academic success. This study examined the differences between students’ identities in offline and OLE via PSM and how students’ identities affect learning achievement motivation through ordinary least squares regression. The study findings revealed that goal-directedness, interpersonal relation, and self-acceptance were lower in students’ identity construction in OLE. In addition, agency, OLE, and the higher average digital device usage for academic purposes have shown statistically significant impacts on achievement motivations. By exploring the nuances of student identity in both offline and OLE contexts, the study offers implications for developing effective pedagogical strategies that cater to the diverse needs of students, ensuring a more inclusive and supportive educational environment.

The study, however, has some limitations that future research should consider. First, this study examined students’ identity in the Chinese context. Thus, the study recommends cultural sensitivity when applying implications and contextualizing the research in other countries with different educational cultures and systems. More research in varying contexts is needed to examine and validate students’ identity in OLE and its association with motivation achievement, other learning attitudes, behaviors, or performance. Second, this study relies on students’ self-report responses to questionnaires, which may cause sampling bias. Hence, rigorous research methods, such as qualitative interviews or longitudinal studies, can be considered to cross-check current findings to reduce the risk of inaccuracies. In addition, our data showed that the later sections of the survey responses (i.e., personal responsibility, self-efficacy and task-orientedness) were not valid even if they were of highly replicable variables. This failure may contribute to the cultural differences, where most questionnaires were developed based on a Western cultural background. Future research should consider conducting cross-cultural studies to understand how different cultural values and educational practices shape students’ identities and their relationship with academic motivation and achievement in online learning environments. Finally, this study did not individually examine differences in students’ identity depending on students’ characteristics such as gender, age, areas of study, etc. as this study used them for covariates in PSM. Future studies can examine whether there is any difference in students’ identity depending on such characteristics by incorporating two sample T-test or PSM-DID.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional ethical policies requiring that all human participant-related data remain within China. However, the data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and subject to approval in accordance with these restrictions.

References

Adams GR, Marshall SK (1996) A developmental social psychology of identity: Understanding the person-in-context. J Adolesc 19(5):429–442

Arfini S, Botta Parandera L, Gazzaniga C, Maggioni N, Tacchino A (2021) Online identity crisis identity issues in online communities. Minds Mach 31(1):193–212

Arıcak OT, Dündar Ş, Saldaña M (2015) Mediating effect of self-acceptance between values and offline/online identity expressions among college students. Comput Human Behav

Austin PC (2011) An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res 46(3):399–424

Bączek M, Zagańczyk-Bączek M, Szpringer M, Jaroszyński A, Wożakowska-Kapłon B (2021) Students’ perception of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey study of Polish medical students. Medicine 100(7):e24821

Bandura A (1977) Self efficacy toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol Rev84(2):191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/10522-094

Bavelier D, Green CS, Dye MW (2010) Children, wired: For better and for worse. Neuron 67(5):692–701

Blau I, Shamir-Inbal T (2017) Re-designed flipped learning model in an academic course: The role of co-creation and co-regulation. Comput Educ 115:69–81

Bonfiglio AY, Munniksma A, Volman M, van Rooij F, Gaikhorst L (2024) Teachers’ attention to students’ funds of identity in Dutch primary school classrooms. Teac Teach Educ, 144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104584

Borlee GI, Kinkel T, Broeckling B, Borlee BR, Mayo C, Mehaffy C, Caporale N (2024) Upper-level inter-disciplinary microbiology CUREs increase student’s scientific self-efficacy, scientific identity, and self-assessed skills. J Microbiol Biol Educ 25(1):e0014023

Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv26071r6

Caton A, Bradshaw-Ward D, Kinshuk K, Savenye W (2022) Future Directions for Digital Literacy Fluency using Cognitive Flexibility Research: A Review of Selected Digital Literacy Paradigms and Theoretical Frameworks J Learn Dev 9(3):381–393

Chen H (2017) Antecedents of positive self-disclosure online: An empirical study of US college students’ Facebook usage. Psychol Res Behav Manag 10:147–153

Cho YH, Caleon IS, Kapur M (Eds.). (2015) Authentic problem solving and learning in the 21st century: Perspectives from Singapore and beyond. Springer

Comi SL, Argentin G, Gui M, Origo F, Pagani L (2017) Is it the way they use it? Teachers, ICT and student achievement. Econ Educ Rev 56:24–39

Cortina JM (1993) What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol 78(1):98

Cousin G, Deepwell F (2005) Designs for network learning: A communities of practice perspective. Stud High Educ 30(1):57–66

Daher W, Shahbari JA (2020) Secondary students’ identities in the virtual classroom. Sustainability 12(11):591708

Davidson R (2015) Wiki use that increases communication and collaboration motivation. J Learn Design, 8(3)

Davis K (2012) Friendship 2.0: Adolescents’ experiences of belonging and self-disclosure online. J Adolesc 35(6):1527–1536

Delahunty J, Verenikina I, Jones P (2014) Socio-emotional connections: Identity, belonging and learning in online interactions. A literature review. Technol Pedagog Educ 23(2):243–265

de Vaate NAB, Veldhis J, Konijn EA (2020) How online self-presentation affects well-being and body image: A systematic review Telemat Inf 47:101316

Dignan MH (1965) Ego identity and maternal identification. J Pers Soc Psychol 1(5):476–483

Eccles JS, Vida MN, Barber B (2004) The relation of early adolescents’ college plans and both academic ability and task-value beliefs to subsequent college enrollment J Early Adolesce 24(1):63–77

Edwards C, Edwards A, Stoll B, Lin X, Massey N (2019) Evaluations of an artificial intelligence instructor’s voice: Social Identity Theory in human-robot interactions Comput Hum Behav 90:357–362

Elliot AJ, Dweck, CS, Yeager DS (Eds.) (2017) Handbook of competence and motivation : Theory and application. Guilford Publications

Erikson EH (1968) Identity, Youth and Crisis. Norton

Everitt B, Skrondal A (2002) The Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics. Cambridge University Press

Fishbein, M, Ajzen, I (2009) Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/859056c521c500e6b42018dd2cdf128db34c7af5

Gillett-Swan J (2017) The challenges of online learning: Supporting and engaging the isolated learner. J Learn Des 10(1):20–30

Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM (1999) Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 10(1):37–48

Gutiérrez-Braojos C (2015) Future time orientation and learning conceptions: Effects on metacognitive strategies, self-efficacy beliefs, study effort and academic achievement. Educ Psychol 35(2):192–212

Henriksen D, Mishra P, Creely E, Henderson M (2021) The role of creative risk taking and productive failure in education and technology futures. TechTrends 65(4):602–605

Hew KF, Huang W, Du J, Jia C (2023) Using chatbots to support student goal setting and social presence in fully online activities: Learner engagement and perceptions. J Comput High Educ 35(1):40–68

Hodson, G., & Earle, M. (2017). Social Identity Theory (SIT). In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (pp. 1-7). Springer International Publishing

Hu P, Kong L-N, Chen S-Z, Luo L (2024) The mediating effect of self-directed learning ability between professional identity and burnout among nursing students. Heliyon 10(6):e27707

Hu C, Zhao L, Huang J (2015) Achieving self-congruency? Examining why individuals reconstruct their virtual identity in communities of interest established within social network platforms. Comput Hum Behav, 50

Huo H, Lesage E, Dong W, Verguts T, Seger CA, Diao S, Feng T, Chen Q (2023) The neural substrates of how model-based learning affects risk taking: Functional coupling between right cerebellum and left caudate. Brain Cogn 172:106088

Jin SH, Im K, Yoo M, Roll I, Seo K (2023) Supporting students’ self-regulated learning in online learning using artificial intelligence applications. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 20(1):37

Jones G, Norman P(2022) Predicting exercise after university: An application of the reasoned action approach across a significant life transition. Psychol Health Med 27(7):1495–1506

Khalid F. (2019) Students’ identities and its relationships with their engagement in an online learning community. International J Emerg Technol Learn, 14(5)

Kim J, Ham Y, Lee SS (2024) Differences in student-AI interaction process on a drawing task: Focusing on students’ attitude towards AI and the level of drawing skills. Australas J Educ Technol 40(1):19–41

Kim J, Detrick R, Yu S, Song Y, Bol L, Li N (2025) Socially shared regulation of learning and artificial intelligence: Opportunities to support socially shared regulation. Educ Inf Technol, 1-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13187-9

Kristie-Lee A, Kim W, Matthew C, Amanda LR (2023) The role of identity in human behavior research: A systematic scoping review. Int J Theory Res, 23(3)

Lai AHY, Wong, ELY, Lau WSY, Tsui EYL, Leung CTC (2024) Life-World Design: A career counseling program for future orientations of school students. Child Youth Serv Rev, 161

Lai CL, Hwang GJ (2016) A self-regulated flipped classroom approach to improving students’ learning performance in a mathematics course. Comput Educ, 100

Lau KL, Jong MSY (2022) Acceptance of and self-regulatory practices in online learning and their effects on the participation of Hong Kong secondary school students in online learning. Educ Inf Technologies

Lee J, Jeong HJ, Kim S (2021) Stress, anxiety, and depression among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic and their use of mental health services. InnovHigh Educ 46:519–538

Li M, Zhang S, Zhang L-f (2024) Vocational college students’ vocational identity and self-esteem: Dynamics obtained from latent change score modeling. Pers Individual Differ, 229

Li N, Lim EG, Leach M, Zhang X, Song P (2022) Role of perceived self-efficacy in automated project allocation: Measuring university students’ perceptions of justice in interdisciplinary project-based learning. Comput Hum Behav, 136

Liao M, Xie Z, Ou Q, Yang L, Zou L (2024) Self-efficacy mediates the effect of professional identity on learning engagement for nursing students in higher vocational colleges: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today 139:106225

Lieberman A, Schroeder J (2020) Two social lives: How differences between online and offline interaction influence social outcomes. Curr Opin Psychol 31:16–21

Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: Teenagers’ use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media Soc, 10(3)

Mairitsch A, Sulis G, Mercer S, Bauer D. (2023) Putting the social into learner agency: Understanding social relationships and affordances. Int J Educ Res, 120

Marsh HW, Martin AJ (2011) Academic self-concept and academic achievement: relations and causal ordering. Br J Educ Psychol 81(1):59–77

Martin AJ, Dowson M (2009) Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Rev Educ Res, 79(1)

McGrath, C., Cerratto Pargman, T., Juth, N., & Palmgren, P. J. (2023). University teachers’ perceptions of responsibility and artificial intelligence in higher education - An experimental philosophical study. Comput Educ: Artif Intell, 4

Molenaar I (2022) The concept of hybrid human-AI regulation: Exemplifying how to support young learners’ self-regulated learning. Comput Educ: Artif Intell, 3

Niemi HM, Kousa P (2020) A case study of students’ and teachers’ perceptions in a Finnish high school during the COVID pandemic. Int J Technol Educ Sci, 4(4)

Normand SLT, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Ryan TJ, Cleary PD, McNeil BJ (2001) Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: a matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol 54(4):387–398

Noroozi O, Alikhani I, Järvelä S, Kirschner PA, Juuso I, Seppänen T (2019) Multimodal data to design visual learning analytics for understanding regulation of learning. Comput Hum Behav 100:298–304

Oztok M, Lee K, Brett C (2012). Towards better understanding of self-representation in online learning. In E-Learn: World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education (pp. 1867-1874). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE)

Patti MV, Patti MV, Jochen P, Jochen P (2011) Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. J Adolesc Health 48:121–127

Qin Y, Lowe J (2021) Is your online identity different from your offline identity?–A study on the college students’ online identities in China. Cult Psychol 27(1):67–95

Rogoff B, Lave J (Eds.) (1984) Everyday cognition: Its development in social context. Harvard University Press

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1983) The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika 70(1):41–55

Rubin DB (2001) Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Services Outcomes Res Methodol. 2, 169–188

Sagie A, Elizur D, Yamauchi H (1996) The Structure and Strength of Achievement Motivation: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. J Orgl Behav 17(5). http://www.jstor.org/stable/2488554

Simons J (2020). From Identity to Enaction: Identity Behavior Theory

Steele CM (1988) The Psychology of Self-Affirmation: Sustaining the Integrity of the Self. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (21, pp. 261-302). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60229-4

Stikvoort B, Juslin P (2022) We are all individuals: Within-and between-subject analysis of relationships between pro-environmental intentions and motivations. J Environ Psychol 81:101812

Su W, Zhang Y, Yin Y. Dong X (2024) The influence of teacher-student relationship on innovative behavior of graduate student: The role of proactive personality and creative self-efficacy. Think Skills Creativ, 52

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1978) Intergroup behavior. Introd Soc Psychol, 401

Taub M, Sawyer R, Smith A, Rowe J, Azevedo R, Lester J (2020) The agency effect: The impact of student agency on learning, emotions, and problem-solving behaviors in a game-based learning environment. Comput Educ 147

Tetzner J, Becker M, Maaz K (2017) Development in multiple areas of life in adolescence: Interrelations between academic achievement, perceived peer acceptance, and self-esteem. Int J Behav Dev. 41(6)

Tongfei G, Zhichao C, Zeqian Z, Cui L, Yuan N, Xiaokang W (2022) Formation mechanism of contributors’ self-identity based on social identity in online knowledge communities. Front Psychol 13:1046525

Tsushima T, Burke PJ (1999). Levels, agency, and control in the parent identity. Soc Psychol Q 62(2):173–189

Wang TH (2011) Developing web-based assessment strategies for facilitating junior high school students to perform self-regulated learning in an e-learning environment. Comput Educ 57(2):1801–1812

Wigfield A, Muenks K, Eccles JS (2021) Achievement motivation: What we know and where we are going. Annu Rev Dev Psychol 3(1):87–111

Wu C, Carroll JM (2024) Self-presentation and social networking online: The professional identity of PhD students in HCI. Internet High Educ 62:100951

Zhou X, Li Q, Xu D, Li X, Fischer C (2023) College online courses have strong design in scaffolding but vary widely in supporting student agency and interactivity. Internet High Educ 58:100912

Zhu H, Li X, Zhang H, Lin X, Qu Y, Yang L, Ma Q, Zhou C (2024b) The association between proactive personality and interprofessional learning readiness in nursing students: The chain medication effects of perceived social support and professional identity. Nurse Educ Today 140:106266

Zhu J, Xie X, Pu L, Zou L, Yuan S, Wei L, Zhang F (2024a) Relationships between professional identity, motivation, and innovative ability among nursing intern students: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon 10(7):e28515

Acknowledgements

The research received funding support from the Digital Game-based Learning (DGBL) Special Interest Group (SIG) Fund within the Academy of Future Education at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (AoFESIG01). Also, the research discloses receipt of the financial support from graduate fellowship grant (no. 14814) from Department of Public Administration at Korea University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sang-Soog Lee and Jinhee Kim conceived the main conceptual ideas, developed research instruments, performed the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Jinhee Kim also contributed to the APC process. Seung Won Yu contributed to the data analysis. Na Li supervised the research process and the data collection and contributed to the manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University’s Institutional Review Board (Approval NO. ER-AOFE -12781164620220903234225) on September 9th, 2022. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Before the study began, the participants (non-vulnerable individuals) were provided with an online consent form and participant information sheet in the online survey by the researchers between 14-21 December 2023 and were fully informed that their anonymity is assured, why the research is being conducted, how their data will be utilized, and there will be no risks to them of participating. They read through and comprehended the study’s purpose, objectives, how their data will be utilized, consent to publish and there are no risks to them of participating. All those who understood the purpose and goals of the research participated. The consent form included contact information for inquiries about the study and withdrawal from participation. The research team obtained written consent from all participants by signing the online consent form and the institution’s ethics committee granted permission to conduct the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, SS., Kim, J., Yu, S.W. et al. College students’ identity differences in offline and online learning environment and their effects on achievement motivation. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1579 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05891-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05891-9