Abstract

This study explores using a GRPO (Generative Ranking Policy Optimization) reward mechanism combined with RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) to train a large language model for creating Tang poetry. The goal was to generate poems that adhere to traditional rules of tone, rhyme, parallelism, and word count while maintaining high artistic quality.The methodology involved building a specialized corpus, using DeepSeek-R1-671B for data distillation, and applying GRPO-based reinforcement learning. Integrating RAG technology further enhanced generation quality.Results showed that the resulting model, Xunzi-Yayun-R1, significantly surpassed the baseline in accurately following poetic rules. This research successfully fuses traditional literary norms with modern generative techniques, providing a viable path for generating other classical texts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The groundbreaking advancements in generative large language models have opened up unprecedented possibilities for the intelligent processing of ancient texts. While models like ChatGPT1 have demonstrated astonishing capabilities in open-domain text generation, achieving professional-level poetry creation under the dual constraints of strict formal rules and profound cultural connotations has become a core challenge that the field of digital humanities urgently needs to overcome. Tang poetry, a treasure of Chinese civilization, requires adherence to a complex system of formal rules and esthetic paradigms. This presents an almost paradoxical demand on AI generation technology: it must precisely fit structural constraints such as level and oblique tones and parallelism, while also achieving artistic sublimation in conveying mood and cultural heritage.

Current mainstream methods have fallen into a path dependency on “scaling law”, resorting to ultra-large-scale models like DeepSeek-R1-671B2 (hereinafter referred to as DeepSeek) to meet metrical requirements. This has led to two prominent problems: on one hand, the high computational power consumption for model inference creates a technical barrier, turning the digitization of cultural heritage into an “expensive experiment”; on the other hand, the simple fine-tuning of general-purpose models often results in a “separation of form and spirit”—while the generated text may barely conform to formal specifications, it commonly suffers from artistic deficiencies such as the mere piling up of imagery and a lack of emotional depth.

To address the dilemma of poor metrical accuracy and artistic expression, the key to solving this problem lies in transforming metrical rules from passive constraints into active guidance. This involves implementing metrical rewards through a rule-based reward mechanism in reinforcement learning, combined with knowledge distillation to break through the artistic expression bottlenecks of lightweight models, ultimately constructing a generative paradigm that is “excellent in both form and spirit”.

This study utilizes GRPO2 reinforcement learning, breaking through the traditional technological path of “exchanging scale for quality”. By constructing a continuous rule encoding mechanism, discrete poetic metrical rules are transformed into differentiable reward signals. A knowledge-oriented distillation strategy is designed to imbue lightweight models with the rhythms of Tang poetry. The Tang poetry generation reasoning model Xunzi-Yayun-R13 is built and combined with RAG technology to make poetry generation logical. This technical path achieves two major breakthroughs on a 32B model: ① surpassing the DeepSeek model in metrical accuracy using only 1 K data; ② reducing inference energy consumption to a range manageable by conventional computing power.

This research is dedicated to solving the following key questions:

Q1. How can an effective, model-optimizable rule-based reward mechanism be established for Tang poetry metrical rules?

Q2. How can large language models learn the rhyming patterns of Tang poetry?

Q3. How can the metrical regularity of generated Tang poetry be comprehensively and accurately evaluated?

Q4. How can a transferable reinforcement learning framework be constructed that can be generalized to other sub-domains of ancient text processing?

By constructing a systematic Tang poetry generation evaluation system and open-sourcing the training framework and model, this study not only confirms the feasibility of professional-level poetry creation with lightweight models but also refines a methodological system of “rule encoding—knowledge distillation—dynamic reinforcement—retrieval augmentation”. This provides an efficient and feasible new technological paradigm for empowering digital humanities with artificial intelligence, especially in the revitalization and inheritance of ancient texts.

The contributions of this study are as follows:

Methodological Innovation: It proposes a “rule encoding—knowledge distillation—dynamic reinforcement—retrieval augmentation” framework, which for the first time transforms discrete poetic metrical rules into adjustable reinforcement learning reward signals. This resolves the core contradiction in traditional methods where metrical regularity and artistic expression are difficult to reconcile. Through the joint optimization of GRPO reinforcement learning and knowledge distillation, the Xunzi-Yayun-R1 model achieved metrical accuracy surpassing DeepSeek, providing an efficient and sustainable technological path for generation tasks in sub-domains of ancient texts. This moves artificial intelligence beyond “cultural replication” and toward “cultural reproduction”.

Technological System Breakthrough: A Tang poetry generation evaluation system was designed, covering four core metrics: level and oblique tones, rhyming, parallelism, and word count. It also introduces an RAG real-time retrieval mechanism driven by the “Pingshui Yun” (《平水韵》)4 database, which increased rhyming accuracy to 91.23%, filling the gap in fine-grained rule quantification within traditional evaluation systems.

Research on the automatic generation of classical Chinese poetry has transitioned from evolutionary algorithms to deep learning methods, and subsequently, towards more complex large language model technologies. This progression not only demonstrates the profound impact of technological iteration on literary creation but also carves out new pathways for the deep integration of traditional culture and modern artificial intelligence.

Early poetry generation frameworks based on evolutionary algorithms combined lexicalized tree adjoining grammar with genetic operators to optimize rhyme and semantics5. The use of level and oblique tone encoding and a syntax-semantic weighting function was introduced for Song ci poetry generation, although linear evaluation led to monotonous poetic meaning6. Later efforts included constructing Tang poetry corpora and establishing DFA (Deterministic Finite Automaton) grammar specifications to strengthen semantic constraints7.

Memory-augmented neural architectures were introduced, integrating Seq2Seq generators with external knowledge bases to generate poetry, which balanced formal regularity with creativity but faced limitations in terms of templating8. Hybrid decoders were designed to alleviate the vanishing latent variable problem, enhancing thematic consistency while considering the metrical esthetics of poetry9. Dual-channel RNNs were applied to model intra-sentence grammar and inter-sentence parallelism rules, but long poetry generation was still constrained by gradient decay10. Visualizable LSTM poetry generation models were established; however, training on a five-character quatrain dataset resulted in weaker performance for generating seven-character poetry11. The combination of BiLSTM with word2vec was explored for processing poetic emotions, achieving mixed emotional expression but with insufficient accuracy12. Furthermore, BERT-based sentiment analysis was integrated with an Attention mechanism in the design of Seq2Seq steganography models, achieving high thematic relevance in poetry generation13.

The GPT series of models, based on the Transformer decoder, master the structural and rhythmic rules of poetry through autoregressive pre-training, supporting innovative fusion of classical forms and modern semantics14,15,16. GPT models have been fine-tuned on classical poetry corpora, generating high-quality and coherent poems, highlighting the potential of large models16. Systems like LingXi were developed by fine-tuning GPT-2 to generate modern poetry, achieving perplexity close to human-written text and excellent diversity17. The “Siku Quanshu” has been utilized to fine-tune models, achieving multi-style classical poetry generation, with performance validated by Turing tests18. Multi-agent frameworks employing social learning have also been proposed to avoid stylistic repetition and enhance poetic novelty19.

Overall, research in automatic classical Chinese poetry generation has iterated through three stages: rule-driven, data-driven, and knowledge-driven, gradually overcoming metrical constraints and evolving towards semantic innovation and multi-style generation. Evolutionary algorithms optimized prosody using genetic operators but tended to produce poems with convergent artistic conceptions. Deep learning methods, utilizing RNNs and Transformers, captured phonetic and rhythmic patterns but were limited by data quality. Large language models, relying on pre-trained knowledge, achieve cross-era semantic fusion, yet bottlenecks persist in creativity and the construction of cultural artistic conception. Current core challenges are concentrated on the dynamic balance between metrics and semantics, cross-modal cultural cognition, and the absence of a quantitative evaluation system, urgently requiring the construction of new paradigms to advance technology towards an artistic dimension.

Currently, innovative applications of large language models in areas such as reasoning ability optimization, multimodal semantic understanding, and cultural heritage are continually pushing the boundaries of intelligence. Research focuses on reinforcement learning-driven performance enhancement and the deep mining of cultural knowledge.

Curriculum-guided GRPO reinforcement learning has been employed to enhance the reasoning capabilities of audio language models, with a multiple-choice question dataset of 32,000 samples being constructed, leading to excellent model performance on audio reasoning tasks20. The DianJin-R1 model, through supervised fine-tuning and GRPO reinforcement learning, has demonstrated superior effectiveness over non-reasoning models across multiple benchmarks21. Fine-tuned Xunzi-series LLMs (e.g., Xunzi-Baichuan) achieve superior cross-lingual classical NER performance, excelling in F1/BLEU/ROUGE metrics with strong generalization22. Instruction-tuned Xunzi-Baichuan2-7B outperforms base models in ancient text translation using 1.2 M parallel corpora, demonstrating domain adaptation efficacy23. Research based on DeepSeek-R1 and RAG technology has led to the construction of an intelligent question-answering system for Pre-Qin cultural classics, using the “Spring and Autumn Annals” as a case study. This involves knowledge extraction and knowledge graph construction, combined with various RAG methods to enhance Q & A performance, providing intelligent support for cultural heritage24. Leveraging GPT-4 API services, work has been done to synthesize domain-specific relation extraction datasets for ancient texts using self-instruct, chain-of-thought, and human feedback. After data augmentation, F1 scores of 56.07% and 30.50% were achieved on two different ancient text relation extraction datasets, respectively25. Addressing the intertextual characteristics of Pre-Qin classics, an unsupervised automatic intertextual discovery process based on large language models has been constructed. This involves training models via a contrastive learning framework and validating the effects in idiom tracing tasks26. An LLM-based automated fact extraction and RAG evaluation framework, AutoNuggetizer, has been proposed to assess the performance of RAG systems27. The CoT-RAG framework has been introduced, which employs knowledge graph-driven chain-of-thought reasoning, knowledge instance-aware retrieval-augmented generation, and pseudo-program prompt execution to significantly enhance the reasoning ability and accuracy of large language models in complex tasks28.

In summary, by integrating reinforcement learning and RAG technology, large language models are achieving precise optimization and performance breakthroughs in vertical domains. Systematic optimization of reasoning ability based on GRPO reinforcement learning significantly improves the efficiency with which models parse complex semantic logic. Meanwhile, deep knowledge enhancement strategies based on RAG further strengthen their domain adaptability and factual consistency. The organic integration of these two aspects is enabling LLMs to transcend traditional task boundaries.

Methods

Theoretical basis and methodology

Current large language models encounter issues of metrical non-conformity in Tang poetry generation, primarily manifested as incorrect level and oblique tones, deviation from rhyme schemes, and uncontrolled word counts. For instance, a seven-character quatrain generated by Kimi29, “春风又绿江南岸, 桃花笑映故人还” (Spring wind greens the southern bank again, peach blossoms smile reflecting the returning old friend), exhibits deviations in its first couplet from the expected tonal pattern (which should be “level-level-oblique-oblique-level-level-oblique, level-oblique-oblique-level-oblique-oblique-level”, whereas the actual output deviates). Furthermore, the piling up of imagery leads to a fragmented artistic conception. These issues reflect three major technical bottlenecks: first, a loss of focus on the dynamic balance between metrical constraints and poetic expression; second, stylistic convergence caused by the homogenization of training data; and third, the lack of fine-grained metrical quantification indicators in traditional evaluation systems.This study proposes an optimization framework that integrates GRPO reinforcement learning with RAG technology. Through GRPO, a multi-dimensional reward mechanism is constructed for level and oblique tones, rhyming, parallelism, and word count, thereby achieving dynamic calibration of metrical rules. Concurrently, RAG is leveraged to retrieve suitable rhyme categories in real-time from the “Pingshui Yun” database, ensuring adherence to rhyming conventions. This approach aims to enable generated poetic verses to not only conform to metrical norms but also, through a rich interplay of tangible and intangible imagery, reinvigorate the vitality of Tang poetry by achieving a resonance between form and spirit. Figure 1.

This chart shows a comparison between the Xunzi-Yayun-R1 model and the DeepSeek model on the task of Tang poetry generation. On the left is the Xunzi-Yayun-R1 model, and on the right is the DeepSeek model. Both were tasked with answering the same classical poetry creation prompts, including composing poems based on specific rhymes and themes.

Research algorithm and framework

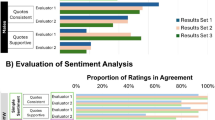

The research framework in this study consists of three core modules:①Knowledge-Oriented Distillation: This module involves constructing a Tang poetry imagery corpus and utilizing the “Pingshui Yun” database to perform knowledge distillation from DeepSeek. This process generates a Tang poetry inference dataset comprising both cold-start data and test data. The aim of this module is to address the insufficient understanding of Tang poetry metrical rules and artistic conception features by models with fewer parameters. Through knowledge transfer, the model is guided to grasp rules such as level and oblique tones and rhyme schemes from the underlying semantics, thereby avoiding the rigid generation patterns caused by rote memorization.②Cold-Starting and Reinforcement Learning: A two-stage training strategy is adopted. First, a general conversational model undergoes supervised fine-tuning based on the cold-start data, initially adapting it into a Tang poetry reasoning model. Subsequently, GRPO reinforcement learning is introduced, designing dual optimization objectives that include format rewards and content rewards (encompassing level and oblique tones, rhyming, parallelism, and word count). This process yields reasoning model-R1. Concurrently, the general conversational model also undergoes direct reinforcement learning without the cold-start phase, resulting in reasoning model-RL, thus forming a basis for comparing different training paths.③Model Comparison and Evaluation: An automated metrical scoring system is constructed using an open-source evaluation tool30 combined with RAG technology. Model performance is quantified using a weighted comprehensive metric (level and oblique tones: 40%; rhyming: 30%; parallelism: 20%; word count: 10%). This module validates the effectiveness of knowledge distillation and staged training by comparing the training path involving cold-starting and reinforcement learning (reasoning model-R1) with the direct reinforcement learning path (reasoning model-RL). Ultimately, reasoning model-R1 is selected as the preferred open-source solution, providing a highly robust solution for Tang poetry generation. This is specifically illustrated in Fig. 2.

To systematically address the issue of metrical non-conformity in Tang poetry generated by large language models, this study designs five core algorithms (Algorithm 1–5) to quantitatively control poetry quality assessment, level and oblique tone rules, rhyming conventions, parallelism correctness, and word count structure, respectively.

Algorithm 1 is the core process for evaluating the quality of generated Tang poetry, calculating a comprehensive score through the weighted computation of multi-dimensional metrics. The input consists of the Tang poetry text and a reference rhyme database, and the output is a quality score ranging from 0 to 100. First, pure Chinese text is extracted (Step 3). A classification algorithm then determines the poem’s type (e.g., Jueju, Lüshi), the number of lines (L), and the number of characters per line (C) (Step 4). If the type is invalid, or if the number of lines and characters per line do not conform to Tang poetry standards (e.g., not 4 or 8 lines, or not 5 or 7 characters per line), a baseline score of 50 is directly returned (Steps 5–7). Subsequently, four sub-algorithms are invoked to calculate scores for level and oblique tones (ST), rhyming (SR), parallelism (SA), and word count (SL) respectively (Steps 8-12). These scores undergo normalization processing (constrained to the 0.1–1.0 range) to prevent interference from extreme values (Steps 13-15). Finally, the total score is obtained based on predefined weights (level and oblique tones 40% + rhyming 30% + parallelism 20% + word count 10%) (Step 16), and is outputted with two decimal places. This algorithm ensures the objectivity of the evaluation through structured rules.

Algorithm 1

Overall Algorithm for Evaluating Tang Poetry

1: Input: Tang poetry text; Reference prosody database

2: Output: Poem quality score S ∈ [0,100]

3: P ← ExtractChineseText(poem)

4: (type, L, C) ← ClassifyPoem(P)

5: if type = null or L not {4,8} or C not {5,7} then

6: return 50.0

7: end if

8: R ← AnalyzeProsody(P, type)

9: ST ← CalculateTonesScore(R, P, L, C)

10: SR ← CalculateRhymesScore(R, type)

11: SA ← CalculateAntithesisScore(R, type)

12: SL ← CalculateLengthScore(P, L, C)

13: for each score Si in{ST, SR, SA, SL}:

14: S'i← max(0.1, min(1.0, Si))

15: end for

16: FS← (S'T×0.4 + S'R×0.3 + S'A×0.2 + S'L×0.1)×100

17: return round(FS, 2)

Algorithm 2 provides a quantitative evaluation of Tang poetry tonal patterns. The input includes the results of a rhythm analysis, the poetry text, and parameters for the number of lines and characters per line; the output is a score for level and oblique tones ranging from 0.0 to 1.0. First, the validity of the poem type is checked (Steps 3–5). The number of errors is then calculated by counting “error” markers in the rhythm analysis results (Step 6). The total number of characters is determined by multiplying the number of lines by the characters per line (Step 7). If errors are present, points are deducted proportionally to the error rate (Steps 8-9); for example, if 4 out of 20 total characters have tonal errors, the score is 1 − (4/20) = 0.8. If no errors are detected and a specific tonal pattern exists (such as a standard Lüshi format), a preset high score of 0.85 is returned (Steps 10-11). If there is no explicit pattern but no errors are found, a base score of 0.7 is returned (Steps 12–14). This algorithm considers strict pattern matching while also accommodating scenarios of free-form creation, thereby balancing conformity with flexibility.

Algorithm 2

CalculateTonesScore(R, P, L, C)

1: Input: R: prosody analysis results, P: poem text, L: line count, C: chars per line

2: Output: ST: tones pattern score ∈ [0.0, 1.0]

3: if type = null then

4: return 0.5

5: end if

6: error_count ← Count(“error” in R)

7: total_chars ← L×C

8: if error_count > 0 then

9: return max(0, 1 - (error_count / total_chars))

10: else if Has TonePattern(R) then

11: return 0.85

12: else

13: return 0.7

14: end if

Algorithm 3 focuses on the automated evaluation of Tang poetry rhyming rules. The input consists of rhythm analysis results and the poem type, while the output is a rhyming score ranging from 0.0 to 1.0. The core logic involves counting the number of rhyming lines and the number of errors. First, the total number of lines marked as “rhyming” is calculated (Step 3). Then, the number of erroneous lines is determined by checking for “error” markers adjacent to the “rhyming” tags (Step 4). If the total number of rhyming lines is <2 (for instance, a Jueju requires at least two rhyming lines), a low score of 0.4 is returned (Steps 5–6). Otherwise, the proportion of correctly rhymed lines is calculated (Steps 7–9). For example, if a poem has four lines marked as rhyming and two of these are incorrect, the score would be (4 − 2)/4 = 0.5. This algorithm places particular emphasis on the fundamental requirement for the number of rhyming lines while also reflecting rhyming quality through proportional calculation. This approach prevents excessive penalization and ensures that low-quality rhyming does not pass undetected.

Algorithm 3

CalculateRhymesScore(R, type)

1: Input: R: prosody analysis results, type: poem type

2: Output: SR: rhymes pattern score ∈ [0.0, 1.0]

3: total_rhyme_lines ← Count(“rhyming” in R)

4: correct_rhyme_lines ← total_rhyme_lines - Count(“error” near “rhyming” in R)

5: if total_rhyme_lines < 2 then

6: return 0.4

7: else

8: return correct_rhyme_lines / max(total_rhyme_lines, 1)

9: end if

Algorithm 4 conducts a graded evaluation of parallelism correctness in Tang poetry. The input parameters are the same as those for the rhyming algorithm, and the output is a parallelism score ranging from 0.0 to 1.0. Processing varies based on the poem type: for Wujue (five-character Jueju) and Qijue (seven-character Jueju), which have less stringent parallelism requirements, a high score of 0.9 is directly returned (Steps 3-4). Conversely, for Wulü (five-character Lüshi) and Qilü (seven-character Lüshi), strict detection of parallelism errors is necessary. The number of errors is calculated by counting negative markers such as “error”, “no”, and “fail” that accompany the “parallelism” tags (Steps 5–6). For each error identified, 0.5 points are deducted (Step 7); The penalty value of 0.5 per error is a tunable hyperparameter, chosen to enforce strictness on the Lüshi form while allowing for minor imperfections. For example, if three errors are detected, the score would be max(0,1 − (0.5×3)) = 0. Other poem types default to a score of 0.7 (Step 9). This evaluation algorithm respects the creative freedom inherent in Jueju forms while reinforcing the specific parallelism requirements for Lüshi forms.

Algorithm 4

CalculateAntithesisScore(R, type)

1: Input: R: prosody analysis results, type: poem type

2: Output: SA: parallelism score ∈ [0.0, 1.0]

3: if type = {“wujue”, “qijue”} then

4: return 0.9

5: else if type ∈ {“wulv”, “qilv”} then

6: antithesis_errors ← Count(“parallelism” and (“error” or “no” or “fail”) in R)

7: return max(0, 1.0 - (antithesis_errors / 2.0))

8: else

9: return 0.7

10: end if

Algorithm 5 evaluates the structural conformity of a poem with respect to the number of lines and characters per line. The input is the poem text, along with the classified number of lines (L) and characters per line (C). The output is a structural score between 0.0 and 1.0. First, basic specifications are validated: if the number of lines is 0, the score is 0 (Step 3); if the number of lines is not 4 or 8, the score is 0.5 (Step 4); if the number of characters per line is not 5 or 7, the score is 0.6 (Step 5). For poems that conform to these specifications, the number of lines with inconsistent character counts is tallied (Step 6). For instance, if an 8-line poem has 2 lines with incorrect character counts, the score will be 1 − (2/8) = 0.75 (Step 7). This algorithm, through a hierarchical penalty mechanism, prioritizes ensuring the fundamental structural features of Tang poetry (four/eight lines, five/seven characters per line), and then provides a finer-grained assessment of the consistency of character counts in individual lines, thereby avoiding the nullification of the overall structural value due to localized errors.

Algorithm 5

CalculateLengthScore(P, L, C)

1: Input: P: poem text, L: line count, C: chars per line

2: Output: SL: structure score ∈ [0.0, 1.0]

3: if L = 0 then return 0.0 end if

4: if L not {4,8} then return 0.5 end if

5: if C not {5,7} then return 0.6 end if

6: inconsistent_lines ← Count(lines where length ≠ C)

7: return max(0, 1.0 - (inconsistent_lines / L))

Data distillation

This study designs a knowledge distillation method based on a multi-dimensional constraint sampling framework, achieving targeted capability transfer of large language models in the domain of Tang poetry generation through structured prompt engineering. First, a semantic space comprising 147 Tang poetry themes, covering 7 major categories such as natural scenery and seasonal solar terms, was constructed. This is integrated with a joint sampling mechanism from “The Pingshui Yun Scheme” corpus of the CText4 to dynamically generate strongly constrained creative instructions. The specific structured prompt generation instructions are shown in Table 1.

Through structured prompt generation instructions, the finally constructed distillation dataset includes: (1) theme-prosody aligned samples that conform to Tang dynasty literary paradigms; (2) inference process data from the DeepSeek model during Tang poetry generation; and (3) fine-grained annotations with four-dimensional scoring (tonal patterns, rhyming, antithesis, character count). This method, via a knowledge embedding mechanism, transfers the poetry creation capabilities of a 671B parameter model to a model with fewer parameters. It achieves knowledge transfer for culturally specific generation using only 1 K high-quality samples. To ensure structural diversity, the 1,000 training examples were deliberately and evenly distributed across the four main Tang poetry forms: five-character Jueju, seven-character Jueju, five-character Lüshi, and seven-character Lüshi (250 examples each). Furthermore, the examples were curated to span a representative range of common classical themes, providing a balanced training foundation for subsequent reinforcement learning that balances normative constraints with artistic diversity.

As shown in Table 2. To address potential data bias and ensure thematic diversity, the 147 themes were meticulously curated to cover a wide spectrum of classical subjects. For example, the “natural scenery” category was broken down into sub-themes such as “mountains”, “rivers”, “moon”, and “willows”, while “seasonal solar terms” included specific themes like “Spring Equinox” and “Autumn Cicadas”. Crucially, the themes used in the training set and the test set were kept mutually exclusive to prevent data leakage and to rigorously evaluate the model’s ability to generalize to unseen topics. This ensures that the model learns the underlying principles of poetic creation rather than merely memorizing thematic patterns.

Cold-start instruction construction

This study employs an instruction fine-tuning method enhanced by Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. Through the coupled design of structured Chain-of-Thought and multi-rule constraints, it achieves controllable poetry generation capability for the model under zero-shot conditions. As illustrated in Fig. 3, cold-start instructions comprise a three-tiered structure:

This figure demonstrates the model’s chain-of-thought reasoning. The left panel shows a complex prompt with multiple constraints. The right panel displays the model’s internal monologue as it systematically analyzes the rules and constructs the poem, showcasing its ability to follow intricate instructions.

① Multi-rule Constraint Encoding: Each instruction is defined by a quintuple L = (T, G, R, F, C), where:

·Theme T is selected from a 7-category theme lexicon (e.g., “隐居”[seclusion]).

·Prosody G specifies the genre (e.g., five-character Jueju / seven-character Lüshi).

·Rhythm R binds to a “Pingshui Yun” category and tone (e.g., “元·平声”-Yuan·Level Tone).

·Format F includes constraints on line count, character count, and punctuation.

·Control token C enforces output purification (prohibits titles/annotations).

② Chain-of-Thought Data Construction: This is constructed using a

③ Cold-Start Data Construction: This integrates the multi-rule constraint instructions and Chain-of-Thought data to construct the reasoning data required for cold-start. Specific data are formatted as instruction tuples as shown in Fig. 3. See Table 1 for specific translation content.

GRPO Reinforcement Learning

GRPO is an efficient optimization algorithm for the reinforcement learning fine-tuning of large language models, proposed by the DeepSeek team. It aims to address the limitations of traditional Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) methods in terms of computational efficiency and training stability. Its core idea is to replace the dependency on a value network with a group relative reward mechanism, combined with dynamic regularization constraints, to achieve efficiency and controllability in policy optimization. Table 3.

GRPO specifically reconstructs the reinforcement learning paradigm through the technical path illustrated in Fig. 4:

Group Sampling and Relative Advantage Estimation: For each input state, multiple candidate actions (i.e., output sequences) are sampled. Relative advantage values are calculated through intra-group reward normalization (Z-score standardization), as shown in formula (1):

Where ri is the reward for a single action, and μ and σ are the mean and standard deviation within the group, respectively.

KL Divergence Constraint: A KL divergence penalty term is directly introduced into the objective function. The magnitude of policy updates is constrained by dynamically adjusting β, preventing the model from deviating too far from the reference policy.

Objective Function Optimization: By integrating policy gradient, a clipping mechanism, and the KL constraint, the objective function is defined by formula (2).

The Format Reward Algorithm is given by formula (3). If the answer generated by the model conforms to the specified rules, +0.5 points are awarded.

The Tang Poetry Prosody Reward Algorithm is given by formulas (4) and (5). If the model achieves a score >50 on any single item, +0.5 points are awarded. If the weighted score exceeds 80, +2 points are awarded.

RAG

RAG31 is a natural language processing technique that combines information retrieval with text generation, aiming to enhance the accuracy and real-time capabilities of generative models by dynamically retrieving from external knowledge bases. Its core idea is to decouple the retriever from the generator: the retriever extracts relevant information from a vast collection of documents, and the generator then produces text based on these retrieved results, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional generative models that rely on static training data. This architecture endows RAG with both the flexibility of “open-book retrieval” and the creativity of “logical generation”, significantly reducing the “hallucination” problem in large models. This study uses LangChain32 as the RAG framework and incorporates vLLM33 for accelerated inference.

The RAG system follows a “Retrieve-Augment-Generate” three-stage process, as detailed in Fig. 5:

· Retrieval Stage: After the user inputs a query, the system employs a vectorization model to convert the query and knowledge base documents into high-dimensional vectors. It then retrieves the most relevant text snippets using metrics such as cosine similarity. For example, inputting “rhyme with '东' (dōng, east) rhyme” would retrieve characters from “Pingshui Yun” that conform to the “东” rhyme category.

· Augmentation Stage: The retrieved results are integrated to form a contextual prompt, which serves as supplementary input for the generation model. This process allows the model to identify the required rhyme and learn how to apply it.

· Generation Stage: The large language model generates the final answer based on the augmented context, ensuring that the content is consistent with the retrieved facts and exhibits natural language coherence.

Experimental Environment and Configuration

In this study, the specific configurations for the experiments are detailed in Table 4. We strictly controlled the experimental conditions, adjusting only the model type and the volume of training data to ensure the accuracy of the results.

To address limitations in computational power, this study opted for the LoRA34 method for cold-start fine-tuning of the models, with specific details provided in Table 5. The LoRA method updates only a small fraction of the model’s parameters, effectively reducing the demand on hardware resources. During this process, LoRA primarily updates low-rank matrices injected into the model’s attention layers. This allows the model to efficiently adapt its understanding of poetic structure and rules from the cold-start data without undertaking a costly full-parameter fine-tune, thereby preserving its vast pre-trained knowledge while specializing for the poetry generation task. This approach enables a broader range of researchers to participate in the study of large language models, enhancing resource utilization efficiency and lowering the barrier to entry for research. The parameters used for GRPO reinforcement learning are listed in Table 6.

In terms of hardware configuration, 8 NVIDIA A800-80GB GPUs were utilized to perform model fine-tuning, inference, and reinforcement learning tasks. The A800-80GB GPUs, with their powerful computational capabilities, provided the necessary support for model training and prediction, ensuring the smooth execution of the experiments.

Results

Rhyme scheme statistics

In “Pingshui Yun”, Tang dynasty poetry predominantly utilized level tones (平声, píngshēng) for rhyming, with Lower Level (下平, Xià Píng) and Upper Level (上平, Shàng Píng) rhyme categories constituting the majority of rhyme feet. The high frequency of level tone rhyme categories in Tang poetry reflects the poets' preference for euphony and rhythm during composition. Particularly among the top 20 rhyme categories, level tone ones such as “Lower Level Eighth Geng” (下平·八庚, Xià Píng · Bā Gēng) and “Upper Level Eleventh Zhen” (上平·十一真, Shàng Píng · Shíyī Zhēn) appear with high frequency, while entering tone (入声, rùshēng) rhyme categories were scarcely used in poetry. This is detailed in Fig. 6.

An analysis of the distribution of rhyme characters, as shown in Table 7, reveals that characters like “人” (people), “来” (come), “时” (time), and “归” (return) appear frequently. The usage of these characters is not only closely related to the themes of Tang poetry but also reflects the poets' preferences for certain emotions and imagery in their creations. High-frequency rhyme characters are typically associated with elements such as nature, time, and human emotions, often employed to express the poets' inner worlds and their reflections on time and life. Overall, the metrical structure and choice of rhyme characters in Tang poetry demonstrate the high degree of importance poets placed on phonetic beauty and emotional expression.

Based on this, the present study employed a stratified sampling strategy to construct the test set: focusing on the top 20 rhyme categories, it covers five-character Jueju, five-character Lüshi, seven-character Jueju, and seven-character Lüshi. This ultimately resulted in a multi-dimensionally annotated test set comprising 500 entries, designed to validate the model’s capabilities in rhythmic reasoning and artistic generation across multiple genres.

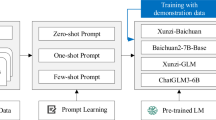

Model evaluation

This study conducted supervised fine-tuning and reinforcement learning on models based on Qwen2.5-32B-Instruct35 and Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct35. It also compared the performance of different models under identical data and training strategies. The evaluation results for Tang poetry generation models, detailed in Table 8, reveal performance disparities across models of varying types, scales, and technical strategies. In the table, bolded values represent the best results for each metric. Based on these results, the following conclusions are drawn:

①Regarding dataset benchmarks, “唐诗三百首” (Three Hundred Tang Poems) with a score of 83.91 and “全唐诗” (Complete Tang Poems) with a score of 82.81, as classic poetry collections, provide high reference standards.

②Among models utilizing RAG, Xunzi-Yayun-R1 achieved the highest score of 86.34, surpassing the Tang poetry generation capabilities of DeepSeek. This was followed by Qwen2.5-32B-Instruct-RAG (86.00) and Qwen2.5-32B-Instruct-GRPO-RAG (85.86). This indicates that RAG technology offers a significant advantage in Tang poetry generation, enabling the combination of large models' generative power with references from external knowledge bases to produce works more aligned with Tang poetry prosody, with performance exceeding that of “Complete Tang Poems” and “Three Hundred Tang Poems”.

③In terms of model parameter scale, the data exhibit a clear scale effect. A performance gradient of 32B > 14B > 7B within the same series is observed across all model types.

④ The cold-start factor influences model performance to a certain extent. Most smaller-parameter models generally achieve a certain level of effectiveness without requiring a cold start, such as Qwen2.5-14B-Instruct (score 79.34, as a conversational model with only fine-tuning). This performance is superior to the cold-started Qwen2.5-14B-Instruct (score 70.92, as an reasoning model). For 32B models, a cold-start + GRPO approach essentially reaches the baseline level, suggesting that 32B models generally possess superior learning capabilities compared to smaller-parameter models.

⑤A dimensional breakdown shows that most models perform best on the 'Length' dimension, with scores generally above 90, indicating that controlling the formal length of poetry is relatively easy to master. This is followed by the 'Antithesis' dimension, where most models score between 80 and 95. Performance on the 'Tones' dimension is moderate, with most scores ranging from 60 to 80. The 'Rhymes' dimension, however, is a weak point for many models, especially those without RAG enhancement, such as the reasoning model internlm2.5-7b-chat, which scored only 41.29.

In summary, reasoning models + RAG demonstrate a significant advantage in rhyming, enabling models to learn rhyming effectively. reasoning models alone already possess good Tang poetry generation capabilities, while conversational models also exhibit initial promising performance. Current Tang poetry generation techniques have achieved a good grasp of prosodic constraints. Employing large models combined with RAG technology, along with cold-start and GRPO reinforcement learning training strategies, presents an effective pathway to enhance the quality of Tang poetry generation.

Turing test

To evaluate the extent to which the generated poems can be distinguished from those written by humans, a Turing Test was conducted. We recruited a group of graduate students from diverse academic backgrounds to serve as non-expert judges. The test material included 125 human-authored poems and 125 poems generated by our models, forming a balanced and randomized collection. To mitigate potential biases stemming from prior familiarity, the human-written poems selected for the test were sourced from relatively obscure classical poets. Participants were presented with each poem individually and asked to rate it on a 5-point Likert scale, indicating their judgment of its origin. The scale was defined as follows: 5 for “very confident it is human-written”, 4 for “likely human-written”, 3 for “unable to determine”, 2 for “likely machine-generated”, and 1 for “very confident it is machine-generated”.

The Turing Test results (Fig. 7) show that for human-authored poems, the combined percentage of scores rated 4 and 5 (indicating a preference for human origin) reached 41.8%. For the top-performing model, DeepSeek-R1, 71.3% of judges rated the poems as human-like or were unable to determine (scores 3, 4, and 5). Similarly, our proposed model, Xunzi-Yayun-R1-32B, also demonstrated excellent performance, with 66.4% of judges assigning scores of 3, 4, or 5, which is also well above the halfway mark. This indicates that the poems generated by these top models possess a high degree of ambiguity in the eyes of individuals, causing more than half of the testers to misjudge or be unable to judge, thus achieving a convincing effect.

This figure presents the results of a Turing test in which human evaluators rated the quality of Tang-style poems generated by various large language models and those written by humans. The performance of each model or human author is shown as a horizontal stacked bar, with the length of the bar representing the complete 100% distribution of scores received. The scores range from 1 (most machine-like) to 5 (most human-like). The color of each segment within a bar corresponds to a specific score: dark red represents a score of 1, light orange represents a score of 2, yellow represents a score of 3 (indicating uncertainty), light blue represents a score of 4, and dark blue represents a score of 5. A larger proportion of blue segments indicates a more human-like performance. The models are categorized by their generation method, including Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), and a reasoning-based prompting strategy (Reasoning). a This panel displays the score distributions for the highest-performing models, ranked by the combined percentage of scores 4 and 5. It also includes the human-written poems as a baseline for comparison. b This panel displays the score distributions for the remaining models tested, sorted by the same performance metric.

Expert evaluation

For a more in-depth assessment of literary quality, a blind expert evaluation was performed. We invited a panel of experts with professional backgrounds in classical literature and poetry to score the poems. The evaluation was conducted under blind conditions, meaning the experts were not informed of the source of any given poem, thus ensuring objectivity in their assessments. Each poem was rated across three distinct dimensions on a 1-to-10 scale: (1) Grammatical Fluency, which assesses the correctness of wording and the smoothness of the sentences; (2) Coherence, which measures the logical and thematic consistency between consecutive lines; and (3) Semantic and Poetic Quality, which evaluates the poem’s capacity to convey rich emotions and artistic imagery. To account for inter-rater variability in scoring tendencies, the raw scores from each expert were normalized using Min-Max scaling before the final mean scores for each dimension were calculated. This quantitative analysis allows for a rigorous comparison of the literary attributes of poems generated by different models against each other and against the baseline of human-authored works.

The results from the expert evaluation, as detailed in Table 9, reveal several key insights into the current capabilities of generative models in literary creation. In the table, bolded values represent the best results for each metric. Most notably, models employing the framework proposed by this graduate student demonstrated a clear superiority over those using only reasoning or standard fine-tuning (SFT). The top-performing model, Xunzi-Yayun-R1-32B, achieved an average score of 5.81, which not only surpasses all other models but also slightly exceeds the human baseline score of 5.74. Similarly, other models like QwQ-32B (5.77) and DeepSeek-R1 (5.75) performed at a level comparable to human authors. A deeper analysis of the sub-metrics indicates that while these top models often match or even outperform humans in structural aspects like Fluency and Coherence, human poets retain a distinct advantage in Poeticness (5.70). This suggests that while AI has become exceptionally proficient at mastering the grammatical and logical “craft” of language, the “art” of imbuing text with deep emotional resonance and novel imagery remains a significant challenge and a key differentiator for human creativity.

Ablation study

To dissect the individual and combined contributions of the proposed enhancement techniques, this study conducted a rigorous ablation experiment. The study systematically evaluated the impact of distinct training configurations—including SFT, GRPO, and RAG—across two model scales: 32B and 7B parameters.

Analysis of 32B-parameter models

The 32B models provided consistent and interpretable results, forming the primary basis of this study’s analysis.

This study compares the performance of distinct training configurations. The Qwen2.5-32B-Instruct model trained with SFT only serves as the reference point. The results are summarized in Table 10.In the table, bolded values represent the best results for each metric.

The results reveal a clear and compelling narrative.

①Impact of RAG: The SFT + RAG configuration achieved a total score of 86.00, significantly outperforming the SFT only score of 80.10. This improvement is almost exclusively driven by a massive surge in the Rhymes score from 65.84 to 87.86. This underscores RAG’s critical role in injecting precise, factual knowledge. However, this comes at the cost of a noticeable degradation in the Tones score, suggesting a trade-off between knowledge-fidelity and stylistic consistency.

②Synergy of GRPO and RAG: A comparison between the SFT + RAG configuration, which scored 76.81 on Tones, and the GRPO + RAG configuration, which scored 80.89, reveals GRPO’s role as a style rectifier. It successfully mitigates the tonal degradation caused by RAG, producing a more robust and well-rounded model.

③Effect of Training Strategy: The dataset presents two different outcomes for the SFT + GRPO configuration. The Xunzi-Yayun-R1-32B result, with a total score of 83.25, outperforms the other SFT + GRPO result. This suggests that the specific implementation or fine-tuning strategy within a given technical framework is a critical factor. Ultimately, the Xunzi-Yayun-R1-32B model with the full SFT + GRPO + RAG suite achieved the highest overall score of 86.34, highlighting how an optimized training strategy amplifies the benefits of enhancement techniques.

Analysis of 7B-parameter models

The experimental results for the 7B models are complex, reflecting the distinct impact of each specific training configuration. The results are summarized in Table 11. In the table, bolded values represent the best results for each metric.

Unlike the clear trends observed in the 32B models, the 7B results are inconclusive and show counter-intuitive performance degradation.

①Performance Degradation: Contrary to the 32B results, nearly every enhancement configuration results in a lower total score compared to the SFT only reference score of 76.22. The SFT + GRPO configuration is particularly notable for its dramatic performance drop to 64.33.

②Anomalous Exception: The only exception is the GRPO + RAG configuration, which achieves the highest score of 80.17 in the 7B series. This suggests a potentially unique synergy between these two techniques when SFT is omitted, though this finding is isolated and requires further verification.

Given the general trend of performance degradation and the ambiguity in the original data logging, this study refrains from drawing firm conclusions about the efficacy of these techniques on 7B models. The results strongly suggest that enhancement methods are not universally applicable across model scales and may require significant re-tuning or different strategies for smaller models.

In summary, this ablation study yields two key findings. First, for large-scale 32B models, a clear synergistic relationship exists: RAG is a powerful tool for knowledge-intensive tasks, and its combination with a stylistic optimizer like GRPO is essential for achieving state-of-the-art performance in complex, creative generation tasks. Second, the effectiveness of these techniques does not appear to scale down linearly, as the 7B models exhibit anomalous performance degradation across most configurations, indicating that model scale is a critical factor and warrants dedicated future research.

Comparative analysis of reinforcement learning methods

To empirically validate the selection of GRPO over other reinforcement learning (RL) methods, a small-scale controlled experiment was conducted comparing its performance against the widely used Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). The primary objective was to assess which method is better suited for internalizing the complex, rule-based constraints of Tang poetry generation.

Experimental Setup: Both GRPO and a standard PPO implementation were applied to the same base model after the initial SFT phase. Both methods used the identical rule-based reward signal derived from our metrical evaluation algorithms (Algorithms 1–5).

The results, summarized in Table 12, indicate a clear advantage for GRPO in this specific task. The GRPO-trained model achieved a higher final metrical accuracy score (83.25) compared to the PPO-trained model (81.33). In the table, bolded values represent the best results for each metric. We attribute this to GRPO’s group relative reward mechanism, which is more effective than PPO’s value network at providing a stable learning signal for tasks with discrete, rule-based reward structures.

This empirical comparison provides strong evidence supporting our choice of GRPO. Its ability to effectively internalize poetic rules and maintain training stability makes it a more suitable algorithm for the nuanced task of classical poetry generation than general-purpose RL optimizers like PPO.

Analysis of inference performance

Figure 8 and Table 13 illustrate the specific inference process of the Xunzi-Yayun-R1 model, demonstrating the reasoning model’s multi-layered structured thinking capability in handling Tang poetry generation. In the first stage of constraint analysis, the model establishes a multi-dimensional parameter space through instruction decomposition: first, it identifies the genre characteristics of a five-character Jueju (four lines, twenty characters); then, it constructs a semantic framework for the “忧愁”(sorrow) theme; and finally, it locks down the rhyming rules of the “Ping Shui Yun” “东” (dōng, east) rhyme. Particularly in the choice of rhyming words, the model demonstrates cross-validation capabilities—first filtering out character groups like “中 (zhōng, center)” and “鸿” (hóng, swan goose) that conform to the “东” (dōng, east) rhyme, then semantically matching them with the thematic imagery, and finally determining the rhyming combination of “古桐中” (gǔ tóng zhōng, ancient paulownia tree, in the center of) and “问孤鸿” (wèn gū hóng, ask the solitary swan goose). This mechanism of coupling sound and meaning effectively avoids the mechanical problem of “rhyming for rhyming’s sake” common in traditional algorithms.

In the second stage of creative reasoning, the model achieves a cross-modal transformation from parameter constraints to poetic expression. By constructing an imagery chain of “孤灯” (solitary lamp)—“寒夜” (cold night)—“泪落” (tears fall)—“愁肠” (bowels)—“孤鸿”(solitary swan goose)”, the model not only completes the montage-like splicing of spatial scenes (indoor → nature) but also employs synesthesia and metaphor to construct emotional logic: “愁肠凝似铁” (sorrowful heart/bowels congeal like iron) transforms abstract emotion into a metallic property, strengthening psychological intensity through tactile texture; “何处问孤鸿”(where to ask the solitary swan goose) utilizes an interrogative sentence structure to elevate individual sorrow into an existential inquiry. It is worth noting that the model exhibits semantic deconstruction capabilities when processing cultural archetypes—“孤鸿” (solitary swan goose) not only inherits the symbolic system of “鸿雁传书” (swan geese delivering messages) (from 《汉书·苏武传》 (Book of Han·Biography of Su Wu)) in traditional poetry but also, through the active nature of “问” (ask), dissolves the passive characteristic of this image. This tension between tradition and modernity demonstrates the algorithm’s innovative potential in the recombination of cultural symbols. The entire inference process exhibits a spirally ascending characteristic: from the rigid satisfaction of constraints to the flexible creation of literary expression, ultimately achieving a dynamic balance between cultural inheritance and the algorithm.

Comparison of verses generated by different models

Table 14 shows Tang poetry generated by different models. In terms of basic metrical rules, Xunzi-Yayun-R1 strictly satisfies all metrical specifications: the eight-line structure is complete, and the second, fourth, sixth, and eighth lines with “漾” (yàng, overflow), “浪 (làng, wave)”, “旷 (kuàng, vast)”, and “唱 (chàng, sing)” all belong to the “去声” (qùshēng, departing tone) 「漾 (yàng, yang)」 rhyme of “Pingshui Yun”. In comparison, other models basically all have rhyming errors, such as with “响 (xiǎng, sound)”, “长 (cháng, long)”, “凉 (liáng, cool)”, etc. Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct only generated seven lines, showing serious formatting errors. internlm2.5-7b-chat mistakenly truncated a Lüshi to four lines, revealing the inadequacy of smaller models in grasping complex formats.

In terms of artistic quality, Xunzi-Yayun-R1 demonstrates advanced poetry creation ability: it constructs a dynamic visual flow through “金乌西坠“ (Golden Crow sets in the west) → “霞光映水“ (rosy clouds reflect on the water) → “山染丹青“ (mountains are dyed in crimson and blue-green) → “江化银浪“ (river turns into silver waves); it achieves an emotional transition from grandeur to desolation in “孤舟渐隐“ (solitary boat gradually fades) / “远笛空余“ (distant flute’s sound lingers alone); and the concluding couplet “星斗替唱“ (stars and constellations take turns singing) breaks through conventional personification techniques, endowing celestial bodies with a lyrical function. The concluding couplet of Qwen2.5-14B-Instruct, “风吹衣袂带余香“ (wind blows the sleeves, carrying lingering fragrance), although possessing artistic conception, has the character “香 (xiāng, fragrant)“ not rhyming with the required 「漾 (yàng, overflow)」 rhyme, showing defects in multi-task coordination.

In summary, differences in parameter scale and training methods lead to significant stratification in model generation capabilities. The 32B parameter model performs optimally in balancing formal specifications and literary quality. Particularly, Xunzi-Yayun-R1, through the word-crafting technique of “江吞赤焰 (river swallows crimson flames) and the surreal imagination of “星斗替唱“ (stars and constellations take turns singing), reaches a creative standard close to that of human poets. Whereas 7B-level models commonly have issues such as formatting errors and forced rhyming, proving the significant meaning of reinforcement learning and RAG in Tang poetry generation.

Discussion

This study, by constructing the GRPO reinforcement learning and its three-fold synergistic mechanism—continuous rule encoding, targeted knowledge distillation, and dynamic reinforcement rewards—under the condition of using only one thousand training data samples and a 32B parameter-scale model, has achieved performance surpassing that of hundred-billion parameter models. This breakthrough not only validates the effectiveness of the “rule encoding—knowledge distillation—dynamic reinforcement—retrieval augmentation“ technological paradigm, but also demonstrates a new model for literary creativity in large language models: the core of poetry creation does not rely on the piling up of massive data, but rather on constructing a multi-dimensionally coupled cultural cognitive system—structurally reorganizing metrical rules.

Experimental data show that the model achieves an rhyming accuracy of 91.23% according to “Pingshui Yun“, and can be deployed on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 card (24GB VRAM) via the Ollama36 framework. The more profound significance of this study lies in the fact that by transforming discrete poetry metrical rules into tunable reward signals, it provides a reusable methodological framework for the digitalization challenges of other art forms, such as Song Ci metrical rules and Xiqu melodies. This technological universality holds landmark significance in the field of digital humanities, marking a systemic innovation in AI-assisted creation from single-modality breakthroughs to cross-art-form systematic innovation, opening up new technological frontiers for the intelligent inheritance of excellent traditional Chinese culture.

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations that offer avenues for future research. First, a comprehensive hyperparameter sensitivity analysis for GRPO was not conducted due to prohibitive computational costs. While our chosen parameters (e.g., warmup_ratio = 0.1, max_grad_norm = 0.1) were based on best practices from the original GRPO paper and preliminary experiments, a full analysis would further strengthen the method’s reproducibility and potentially unlock further performance gains. Second, while our expert evaluation provides robust qualitative insights, the assessment of “artistic diversity“ remains largely subjective. Future work should aim to integrate more objective, quantitative metrics to better capture creative variation.

Data availability

We opened our project to GitHub (https://github.com/Xunzi-LLM-of-Chinese-classics/Xunzi-Yayun-R1).

References

OpenAI et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774 (2024).

DeepSeek-AI et al. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.12948 (2025).

GitHub. Xunzi-LLM-of-Chinese-classics/Xunzi-Yayun-R1:Xunzi-Yayun-R1. https://github.com/Xunzi-LLM-of-Chinese-classics/Xunzi-Yayun-R1 (2025).

Sturgeon D. PingshuiYunbu: PingshuiYunbu—Chinese Text Project. https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=190510&remap=gb (2025).

Manurung, H. An evolutionary algorithm approach to poetry generation. (2004).

You, W. Research on Automatic Generation of Song Ci Based on Genetic Algorithms. (Xiamen University, 2008)(in Chinese)

Cao, W. H. Automatic Generation System for Imitating Tang Poetry Based on Evolutionary Strategies. (Guangdong University of Technology, 2011) (in Chinese).

Zhang, J. et al. Flexible and creative chinese poetry generation using neural memory. In Proc. 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds. Barzilay, R. & Kan, M.-Y.) 1364–1373 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2017).

Yang, X., Lin, X., Suo, S. & Li, M. Generating thematic Chinese poetry using conditional variational autoencoders with hybrid decoders. In Proc. 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 4539–4545 (AAAI Press, Stockholm, Sweden, 2018).

Li, Z. Research on Automatic Generation of Ancient Poetry and Ci Based on Neural Networks. (Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, 2018)(in Chinese).

Hu, W. Research on Automatic Generation and Visual Analysis of Classical Poetry Based on RNN. (Central China Normal University, 2021) (in Chinese).

Bao, C. & Huang, L. Chinese traditional poetry generating system based on deep learning. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2110.12335 (2021).

Lu, J., Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., Yang, W. & Zhou, B. Automatic poetry and ci generation steganography algorithm and system. Software Guide 23, 48–55 (2024).

Jia, K. Sentiment classification of microblog: a framework based on BERT and CNN with attention mechanism. Comput. Electr. Eng. 101, 108032 (2022).

Ye, J. et al. A comprehensive capability analysis of GPT-3 and GPT-3.5 series models. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.10420 (2023).

Liao, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, Q. & Jiang, X. GPT-based generation for classical Chinese poetry. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1907.00151 (2019).

Zhang, X., Sun, M., Liu, J. & Li, X. Lingxi_ A diversity-aware Chinese modern poetry generation system. In Proc. 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 3: System Demonstrations) (eds. Bollegala, D., Huang, R. & Ritter, A.) 63–75 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023).

Liu, J. F. et al. A practical exploration of AlGC-powered digital humanities research:a SikuGPT driven research of ancient poetry generation. Information. Stud. Theor. Appl. 46, 23–31 (2023).

Zhang, R. & Eger, S. LLM-based multi-agent poetry generation in non-cooperative environments. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.03659 (2024).

Wen, C., Guo, T., Zhao, S., Zou, W. & Li, X. SARI: Structured audio reasoning via curriculum-guided reinforcement learning. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.15900 (2025).

Zhu, J. et al. DianJin-R1: Evaluating and enhancing financial reasoning in large language models. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.15716 (2025).

Xu, Q., Liu, Y., Wang, D. & Huang, S. Automatic recognition of cross-language classic entities based on large language models. NPJ Herit. Sci. 13, 1–12 (2025).

Zhao, Z., Sun, G., Liu, C. & Wang, D. Research on machine translation of ancient books in the era of large language model. Npj Herit. Sci. 13, 1–9 (2025).

Zhang, Q., Gao, Y., Ren, D., Han, M. & Bao, P. Research on intelligent question answering for pre-qin cultural classics by integrating deepseek-r1 and rag technologies. J. Modern Inf. https://link.cnki.net/urlid/22.1182.G3.20250414.0937.002 (2025). (in Chinese).

Liu, C. et al. Research on the extraction and application of ancient books' restricted domain relation based on large language model technology. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inform. 44, 200–219 (2025).

Ye, W., Hu, D., Wang, D., Zhou, H. & Liu, L. Research on unsupervised automatic intertextual discovery based on large models of ancient books. Library Inform. Service 68, 41–51 (2024).

Pradeep, R. et al. The great nugget recall: automating fact extraction and rag evaluation with large language models. ArXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.15068 (2025).

Li, F. et al. CoT-RAG: Integrating chain of thought and retrieval-augmented generation to enhance reasoning in large language models. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.13534 (2025).

Team, K. et al. Kimi k1.5: Scaling reinforcement learning with LLMs. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.12599 (2025).

hulbji/couyun. A Tool for Checking Rules of Chinese Poems. https://github.com/hulbji/couyun (2025).

Lewis, P. et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 9459–9474 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2020).

langchain-ai/langchain. Build Context-Aware Reasoning Applications. https://github.com/langchain-ai/langchain (2025).

Kwon, W. et al. Efficient memory management for large language model serving with pagedattention. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.06180 (2023).

Hu, E. et al. LORA: LOW-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.09685 (2022).

Yang, A. et al. Qwen2 technical report. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.10671 (2024).

ollama/ollama. Get Up and Running with Llama 3.3, DeepSeek-R1, Phi-4, Gemma 3, Mistral Small 3.1 and Other Large Language Models. https://github.com/ollama/ollama (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Social Science Foundation of China project “Research on the construction and application of cross-language support library for ancient Chinese classics” (Grant No. 21 & ZD331), the general project of the Jiangsu Provincial Social Science Fund, “Research on the Construction and Application of Knowledge Graphs for Figures in the ‘Twenty-Four Histories’“ (Grant No. 24TQB004) and Jiangsu Provincial Social Science Foundation Youth Project “Cross-Linguistic Knowledge Organization and Application Research on Metaphors in Classical Poetry Across Dynasties“ (Grant No. 24TQC009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenhua Zhao wrote the main manuscript. Xiyu Wang verified the experimental results. Jiacheng He prepared the section on related work. Zhixiao Zhao and Chang Liu contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. Liu Liu conceived and designed the overall research framework.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Consent to Publish declaration not applicable

Consent to Participate declaration not applicable

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, W., Wang, X., He, J. et al. Large language models learning to write rhyming Tang poetry A Xunzi Yayun R1 case study. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 519 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02087-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02087-x