Abstract

As semiconductor devices approach fundamental physical scaling limits, molecular electronics has emerged as a potential technological paradigm for sustaining Moore’s Law through the capabilities of single-molecule-scale functional manipulation and quantum modulation. At the foundational research level, the convergence of atomic-precision fabrication techniques with molecule–electrode interfaces and molecular orbital engineering has enabled the directional construction of electronically functional single-molecule devices, including molecular switches, rectifiers, and field-effect transistors, accompanied by preliminary validations of molecular device array integration. However, molecular electronics confronts multifaceted challenges spanning device-level bottlenecks in precise molecular assembly, accurate quantum charge transport characterizations, and performance reproducibility, coupled with integration-level limitations imposed by conventional two-dimensional planar architectures that fundamentally constrain functional density scaling, rendering the realization of high-density integrated molecular devices with operational logic capabilities exceptionally demanding. To address these critical issues, researchers have developed various device fabrication and characterization techniques in recent years, such as the integration of top-down micro/nano-fabrication technologies with bottom-up atomic manufacturing approaches, which have significantly enhanced the stability of molecular devices and data reproducibility. This review systematically summarizes recent advances in preparation methodologies for molecular electronic devices with high reproducibility and reliability, with prospective emphasis on an integrated architecture strategy combining atomic manufacturing technologies with three-dimensional (3D) integrated manufacturing technologies, offering a potential roadmap to transcend conventional two-dimensional integration paradigms and realize logical computing functionalities in molecular electronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the beginning of 2020 s, the progress in the integrated circuits industry driven by Moore’s Law1,2 has significantly decelerated when achieving mass production at the 3-nm technology node, where gate lengths have been reduced below 15 nm, while the International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductor (ITRS) has extended the mass production of sub-1 nm node by the year of 20353,4. As the process node is being shrunk closer to physical limits5,6, R&D investments for advanced processes have exponentially grown: the construction cost of a 3-nm node production line exceeds $20 billion, while the investments for next-generation 2-nm node are expected to increase by 50%7,8, resulting in a historic inflection point where the decrease of per-transistor cost exceeds the increase of investments. However, how to further extend Moore’s Law requires quite a challenge, not only from discovering new working principles but also from developing new manufacturing technologies. Molecular electronics has emerged as a potential post-Moore-era direction using single molecules as functional units, with its core value manifested in three aspects: first, new operating mechanisms through quantum tunneling transport at single-molecule scale9, distinct from classical transport in traditional semiconductor devices; second, the feature size of single molecules is at sub-5 nanometer scale, demonstrating potential high-density integration10,11; third, the molecular orbital energy levels for tunneling properties and interface coupling effects can be chemically synthesized in atomic-level precision for tuning electrical properties of molecular devices12.

In the field of molecular electronics, assuming that each molecule can be functioned as an individual device, the construction of molecular electronic device arrays via self-assembled monolayer (SAM) technology could theoretically achieve an integration density of up to 1014 molecular devices per square centimeter, surpassing the transistor integration density of approximately 1011 devices/cm2 in 1-nm node integrated circuit by 2-3 orders of magnitude. Recently, researchers have developed molecular electronic devices based on quantum tunneling effects, including conducting wires13, insulators14, switches15,16, Fano resonance devices17, diodes/rectifiers18,19,20, thermoelectric devices21, optoelectronic molecular units22, nonvolatile molecular memristors23, and even single-molecule transistors24,25,26,27. However, challenges persist in achieving high stability and reproducible characterization of molecular electronic devices, and unresolved issues remain in the heterogeneous integration of molecular devices with silicon-based microelectronic systems regarding multi-physical field coordination, such as interface coupling and thermodynamic stability28,29, while systematic methodologies for high-density integration and logic interconnects of molecular devices have yet to be established30, which are critical for practical applications of molecular electronics. Therefore, to achieve highly stable construction and highly reproducible operation of molecular electronic devices, numerous micro/nano-technologies for molecular junction fabrication and even atomic manufacturing methods for molecular device assembly have been developed. Future solutions may integrate bottom-up atomic-precision fabrication techniques such as molecular self-assembly31 with top-down silicon-based manufacturing technologies, alongside implementing advanced packaging technologies, potentially for future high-density integrations and inter-connections for logic operations and computing through molecular circuits32,33,34 (Scheme 1).

In this review, we systematically summarize critical advancements in the field of molecular electronics, with a focus on device fabrication, functionalization strategies, and large-scale integration technologies, while providing insights into the future development of this area. First, we explore the fabrication technologies of molecular electronic devices, including molecular tunneling mechanisms, manufacturing methods for molecular junctions, atomically precise fabrication approaches, and functionalization of molecular electronic devices. Second, the preliminary attempts of the two-dimensional molecular devices integration are reviewed, further adopting from the conventional three-dimensional integration in the semiconductor industry by advanced package technologies, the strategy of 3D high-density integration of molecular electronic devices is proposed by combining bottom-up assembly and top-down manufacturing. Finally, from the dual perspectives of challenges and opportunities in molecular electronics, we outline future directions for integrated molecular electronic systems in potential applications such as storage and logic computing, as well as molecular sensing and characterization.

Fabrication of molecular electronics devices

Molecular Tunneling Mechanism

Molecular junctions, as the core building blocks of molecular electronic devices, exhibit distinct quantum characteristics in their charge transport behavior at the nanoscale35. When the interelectrode distance is reduced to single-molecule dimensions ( < 3 nm), classical Ohm’s law fails, and quantum tunneling starts to dominate charge transport5. This section systematically elucidates the fundamental principles of molecular tunneling through two perspectives: charge transport mechanisms and quantum interference effects.

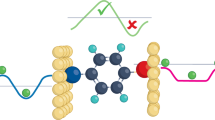

The construction of molecular junctions fundamentally relies on the formation of adjustable nanoscale gaps (0–3 nm) between metallic electrodes, with their electron transport characteristics governed by two key factors: the intrinsic electron transmission properties of the molecular backbone and the chemical coupling strength between terminal anchoring groups (e.g., thiol groups) and metal electrodes36. In a prototypical metal-molecule-metal junction architecture, the conductance follows an exponential decay relationship with molecular length described by \(G=A{{\rm{e}}}^{-\beta l}\), where \(G\) represents the total junction conductance, \(A\) corresponds to the vacuum tunneling conductance\(\,{G}_{0}\,\)(regarded as a quantum mechanical representation of contact resistance that directly correlates with molecule–electrode coupling strength), \(l\) denotes the effective transport length of the junction, and \(\beta\) represents the tunneling decay constant of the molecular framework. Depending on the nature of electron-molecule interactions, charge transport mechanisms in molecular junctions can be categorized into two fundamental regimes (Fig. 1a): coherent transport (preservation of quantum coherence in electron wavefunctions during molecular traversal) and incoherent transport (destruction of quantum coherence through energy dissipation processes)7,37. From a theoretical perspective, the Non-Equilibrium Green’s Function (NEGF) methodology38 provides a first-principle computational framework for precisely modeling quantum transport phenomena, enabling simultaneous resolution of molecular orbital energeis (static electronic structure) and dynamic characterization of quantum tunneling processes through molecular orbitals, including critical mechanisms such as quantum interference effects and inelastic scattering events, thereby achieving quantitative predictions of transport properties like I-V characteristics and conductance quantization behaviors. As a cornerstone of quantum transport theory, NEGF has become the standard computational approach in molecular electronics simulations39,40,41, rigorously addressing the evolution of electron density matrices under non-equilibrium conditions to describe quantum transport processes in nanoscale molecular devices.

a Schematic diagram of direct tunneling and hopping tunneling, reproduced from ref.7, copyright 2022, with permission from Institute of Physics Publishing. b Quantum interference in benzene ring molecular junctions: Phase relationship of wave functions through two transport paths (R represents the anchoring group bound to the electrode). c Quantum interference-driven electron transmission probability (para: red, meta: green) vs energy. (b, c) reproduced from ref.44, copyright 2017, with permission from Springer Nature

At the nanoscale, when multiple electron transport pathways coexist within a molecule, quantum state superposition between different orbitals induces quantum interference effects (QI) that substantially modulate conductance characteristics and govern charge transport behavior. This phenomenon not only establishes a crucial theoretical framework for understanding molecular-scale charge transport, but more importantly, opens new avenues for quantum manipulation of functional molecular devices42,43. A paradigmatic example is observed in benzene-derived molecular systems: para-connected configurations create spatially symmetric dual-channel transport systems that maintain synchronized phase coherence in wavefunction superposition, generating constructive quantum interference (CQI) near the Fermi level manifested as broad electronic transmission plateaus, whereas meta-connected configurations exhibit π-phase differences in wavefunctions due to topological distinctions in transport pathways (Fig. 1b), triggering destructive quantum interference (DQI) that suppresses electron transmittance at specific energy levels (particularly around the Fermi level), resulting in dramatic conductance variations spanning orders of magnitude44 (Fig. 1c). This quantum-interference-based conductance modulation mechanism demonstrates unique nonlinear response characteristics, with its pronounced quantum control effects providing essential physical implementation schemes for developing high on-off ratio and low-power molecular electronic devices.

Fabrication of molecular junctions

The construction of electrode–molecule–electrode junction systems stands as a central challenge in molecular electronics research. To achieve precise capture of target molecules within nanogaps, two primary fabrication strategies have been developed: static molecular junctions, fabricated via micro/nano-fabrication techniques with static electrode spacing, offering high structural stability and interfacial tunability; and dynamic molecular junctions, which enable repetitive formation-breakage cycles through controlled electrode displacement, generating extensive conductance datasets for statistical analysis to improve detection accuracy of molecular electric properties. The subsequent sections will systematically elaborate on the technical principles underlying these two approaches and conduct a comparative analysis of their strengths and limitations.

Static molecular junction

Static molecular junction devices, serving as pivotal platforms in molecular electronics, enable the exploration of charge transport mechanisms under quantum confinement effects and the development of nanoelectronic components surpassing silicon-based limitations by establishing precise conducting channels at single-molecule scale (typically <3 nm) between fixed electrodes. These devices are characterized by their non-volatile architecture: molecules are stably anchored within electrode gaps through covalent bond interactions45,46 or non-covalent bond interactions47,48, forming solid-state electronic interfaces with well-defined structure-property relationships. Compared to dynamic molecular junctions, static counterparts exhibit superior mechanical stability and electrical reproducibility. This section briefly introduces common methodologies for constructing static molecular junctions.

Electromigration junction

Electromigration refers to the phenomenon where momentum transfer between electrons and atoms under an applied electric field drives atomic migration against the current direction, resulting in void formation and eventual circuit failure in conductors. Long recognized as a major reliability threat to microelectronic devices49, electromigration has recently been repurposed as a critical technique for fabricating nanogaps in molecular-scale devices50,51,52. A common approach involves increasing the local current density at weak points of metallic nanowires to induce rupture, forming face-to-face source and drain electrodes (Fig. 2a, b). In 1999, Park et al.53 first demonstrated electromigration-generated 1 nm nanogaps by progressively increasing the bias across the electron beam lithographic patterned gold nanowires. However, linear current ramping risks excessive Joule heating, which can melt nanowires and deposit metallic debris in gaps54, interfering with molecular bridging and generating spurious signals. Additionally, the resulting nanogap sizes exhibit poor controllability and broad distributions, often yielding oversized gaps unsuitable for molecular junctions.

a Top and cross-sectional views of gold nanodot devices fabricated via electromigration and self-breaking techniques. b Current–voltage (I–V) characteristics of controlled electromigration in air. a, b reproduced from ref.325, copyright 2024, with permission from American Chemical Society. c Schematic of the EGaIn-exTTF-Au molecular junction. d Rectification mechanism of the EGaIn-exTTF-Au junction. c, d reproduced from ref.326, copyright 2024, with permission from Wiley. e Layered schematic of the single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) OCGT device, reproduced from ref.327, copyright 2021, with permission from Wiley. f Graphene-based single-molecule transistor (SMT) architecture with a porphyrin molecule as the central component, reproduced from ref.26, copyright 2024, with permission from Springer Nature. g DNA positioning principle: electron-beam or photolithographic patterning on HMDS-passivated substrates generates hydrophilic hydroxyl groups for selective DNA assembly. h SEM image of the hybrid SiO₂-AuNPs-DNA nanostructure assembly. g, h Reproduced from ref.120, copyright 2023, with permission from Springer Nature

To address these limitations, researchers have optimized electromigration protocols for precise nanogap control. One notable strategy is self-breaking, where O’Neill et al.55 pre-thinned gold nanowires to atomic-scale constrictions via programmed electromigration. Leveraging gold’s high room-temperature mobility, spontaneous rupture under zero bias produced nanogaps with minimal residual metal clusters. Another breakthrough is feedback-controlled electromigration (FBEM), pioneered by Strachan et al.56 in 2005. By monitoring conductance as a real-time feedback signal to adjust applied bias, they achieved deterministic control over nanogap widths.

Advanced characterization techniques have elucidated electromigration dynamics. In 2007, Heersche et al.57 performed in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging, revealing asymmetric void nucleation near the cathode. Concurrently, Taychatanapat et al.58 employed real-time scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to demonstrate that reducing series resistance suppresses metallic debris formation. Strachan59 and Stöffler60 further utilized TEM and scanning force microscopy (SFM) to monitor crystallographic plane evolution and energy profiles during electromigration, proposing mechanistic models to explain these observations.

SAM EGaln junction

Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs), highly ordered molecular layers spontaneously formed on solid substrates, typically require initial assembly on a bottom electrode followed by deposition of a top electrode to complete the molecular junction. Conventional methods involve evaporating solid metals as top electrodes61, however, gold atoms can permeate SAMs at room temperature, forming buried conductive layers that short-circuit devices62. Researchers have thus explored alternative strategies. Liquid mercury, compatible with diverse molecular systems and capable of forming non-damaging conformal contacts with molecular layers, emerged as a key solution. In 2001, Holmlin et al.63 constructed Ag-SAM(1)-SAM(2)-Hg junctions using SAMs and liquid mercury to measure electron transport rates across organic films with varying molecular architectures. They demonstrated that junction conductance depends on SAM molecular structure and thickness, further comparing electron transport in SAMs bound via van der Waals interactions versus covalent, hydrogen, or ionic bonds64.

Mercury’s high toxicity, volatility, and difficulty in forming submicron contacts spurred the search for safer alternatives. Whitesides et al.65 firstly introduced an eutectic gallium-indium alloy (EGaIn) as a non-toxic substitute. EGaIn forms metastable non-spherical structures (e.g., conical/filamentous tips) at room temperature, exhibits high conductivity, and achieves low-contact-resistance interfaces with diverse materials66. A typical protocol involves contacting a syringe-deposited EGaIn droplet with a silver film and retracting to form conical tips. The team67 also studied EGaIn’s rheological behavior in microfluidic channels, demonstrating rapid channel filling under pressure and structural stability upon pressure release, providing critical insights for microfluidic integration. Wan et al.68 later stabilized EGaIn in microfluidic devices to construct reproducible tunneling junctions with precise electrical characteristics. SAM-EGaIn junctions have become pivotal tools for studying molecular electronic properties69 (Fig. 2c, d) such as rectification70,71 and odd-even effects72,73. Nijhuis et al.70 tested rectification currents in thiol-based SAMs using SAM-EGaIn systems, modulating rectification mechanisms by spatially tuning conductive and insulating moieties within SAMs. Thuo et al.72 leveraged EGaIn’s conical tips to statistically compare charge transport in n-alkanethiols with odd versus even methylene groups, revealing higher current densities for even-numbered chains.

The native Ga2O3 layer on EGaIn surfaces critically influences functionality. In 2009, Nijhuis et al.74 proposed that Ga2O3’s non-Newtonian properties stabilize conical tips for reliable SAM contacts. Subsequent studies by Cademartiri75 and Reus76 characterized Ga2O3’s properties, including an average thickness of ~0.7 nm and resistivity, confirming SAM-dominated charge transport with negligible contributions from the oxide layer.

This review concentrates on the origins and evolution of SAM EGaln junction technology. For extended discussions on its properties, applications, and recent advances, consult the 2023 review article by Zhao et al.77.

Carbon nanotube junction

Metal electrodes, while pivotal in molecular electronics, face several critical challenges: (a) high interfacial contact barriers with molecules, leading to inefficient charge injection; (b) enhanced quantum tunneling effects in ultrathin metallic films, which obscure weak molecular signals; (c) lack of directional chemical bonding sites on surfaces, resulting in device performance variability78. Carbon nanomaterials, including carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene, have emerged as promising alternatives due to their unique properties. As low-dimensional molecular-scale systems, CNTs bridge fewer molecules, enabling single-molecule junction formation. Their π-π conjugated frameworks provide superior conductivity, while functionalizable termini allow covalent bonding for exceptional mechanical, thermal, and chemical stability79,80.

Discovered by Iijima et al. in 199181, CNTs exhibit metallic or semiconducting properties without passivated interfacial states, facilitating integration with high-κ dielectrics (Fig. 2e)82,83. Three primary methods have been developed to create molecular-scale gaps in CNTs: electrical breakdown84, oxygen plasma cutting85, and focused ion beam (FIB) etching. In 2001, Collins et al. discovered that multi-walled CNTs (MWNTs) undergo stepwise failure through rapid oxidation of outer carbon shells when biased beyond power thresholds86,87. Building on this, Tsukagoshi et al.88 applied high currents to MWNTs bridging Pt/Au electrodes, generating sub-50 nm gaps for pentacene-based organic nanotransistors via thermal evaporation. While electrical breakdown enables rapid nanogap fabrication, its poor controllability results in random gap sizes. In 2008, Wei et al.89 combined electrical breakdown with electron-beam-induced deposition (EBID), using SEM beams to refine CNT gaps while performing in situ characterization for controlled nanogap formation.

Oxygen plasma cutting, first reported by Guo in 200690, involves e-beam lithography to pattern PMMA-coated single-walled CNTs (SWNTs), followed by oxygen plasma exposure to create sub-10 nm gaps with carboxyl-terminated electrodes. These carboxyl groups capture amine-functionalized molecules via stable amide bonds, yielding robust molecular junctions resilient to environmental fluctuations. FIB etching, demonstrated by Roy et al.91, enables precision gap control in SWNTs through ion beam current and exposure time optimization, with subsequent nitric acid treatment for carboxylation.

Comparative analysis reveals tradeoffs: electrical breakdown offers simplicity but poor control; plasma cutting suits scalable integration yet requires e-beam lithography for precision; FIB etching achieves atomic-scale accuracy at high costs. Future advances demand synergy between novel materials (e.g., 2D materials, supramolecular conductors) and atomically precise fabrication (e.g., DNA-mediated assembly) for high-performance scalable molecular electronics.

The rise of CNT research paralleled investigations into DNA’s charge transport, which exhibits insulator-to-metal transitions sensitive to environmental factors92,93,94,95. Guo et al.96 resolved measurement challenges by covalently linking amine-modified DNA to SWNTs via amide bonds, enabling the first direct conductivity measurements. CNT-DNA hybrids have advanced biomedical applications: Lee’s group97 developed single-molecule field-effect transistor (smFET) biosensors in 2024 by functionalizing CNTs with DNA aptamers, achieving serotonin detection at single-molecule levels with sub-second resolution.

Graphene junction

Graphene, another critical carbon-based electrode material (Fig. 2f), consists of a single-layer two-dimensional structure formed by sp2-hybridized carbon atoms arranged in a tightly packed honeycomb lattice. It exhibits unique physical and electronic properties98,99,100: atomic-scale stability at room temperature, ultrahigh carrier mobility with minimal sensitivity to chemical doping, natural compatibility with molecules for low-resistance contacts to reduce switching time, reduced gate screening effects compared to 3D electrodes due to its 2D nature, and superior suitability for large-scale integration into arrays compared to carbon nanotubes (CNTs).

Two primary methods have been developed to fabricate graphene nanogaps: electroburning101,102,103 and oxygen plasma etching. In 2011, Prins et al.103 demonstrated feedback-controlled electroburning at room temperature to create 1–2 nm gaps, with subsequent molecular assembly yielding graphene-based junctions exhibiting robust gating characteristics. The oxygen plasma etching approach, first reported by Guo’s team in 2012104, introduced a “dash-line lithography” technique: photolithographically patterned graphene was selectively etched by oxygen plasma through a PMMA mask, producing carboxyl-terminated edges for stable covalent amide bonds with target molecules with an over 50% yield.

While electroburning offers higher yield, its stochastic nature limits positional control of nanogaps. Oxygen plasma etching enables wafer-scale nanogap arrays with precise positioning but suffers from lower yields. In 2014, Lau et al.105 synergized both methods by transferring graphene onto lithographically patterned metal substrates for plasma etching, followed by feedback-controlled electroburning at the narrowest regions of pre-etched grooves. This hybrid strategy achieved 0.5-2.5 nm gaps with 71% yield and sub-nanometer positional accuracy, paving the way for scalable graphene device integration.

Post-Moore’s Law demands for exponential growth in data processing have driven structural optimizations of graphene devices. In 2020, Rong et al.106 modulated graphene’s electronic structure via nitrogen doping, enabling reversible molecular assembly for high-sensitivity chemical switches. By 2024, Liu et al.107 developed a graphene/germanium Schottky junction-based hot-carrier transistor, leveraging diverse thermal carrier generation mechanisms to populate high-energy states, achieving enhanced speed and reduced power consumption.

DNA origami positioning junction

DNA origami technology, leveraging biomolecular self-assembly, bridges molecular-scale precision with micro/nanofabrication capabilities, offering scalable solutions for highly integrated molecular devices. First proposed by Rothemund in 2006108, this technique employs short staple DNA strands to fold long scaffold DNA into predefined 2D shapes. Douglas et al. extended this concept to 3D architectures in 2009109, enabling spatial positioning beyond planar constraints. DNA origami serves as programmable templates for organizing nanowires, carbon nanotubes, or gold nanoparticles via specific interactions110,111,112,113,114,115.

In 2010, Hung et al.116 selectively deposited DNA origami-gold nanocrystal hybrids onto lithographically patterned substrates, achieving large-scale ordered 2D nanoparticle arrays. However, uncontrolled deposition of origami solutions necessitated advanced positioning strategies. Kershner et al. addressed this in 2009117 by creating DNA origami binding sites on SiO₂ and diamond-like carbon substrates via e-beam lithography and dry oxidation, immobilizing origami through Mg2+-mediated electrostatic bridging. Despite progress, high Mg2+ concentrations risked component aggregation and material-specific limitations.

Gopinath et al. introduced covalent bonding strategies (CDAP and CTES/EDC) in 2014118,119, replacing electrostatic interactions with stable covalent linkages for Mg2+-free origami arrays. By 2023, Martynenko et al.120 advanced 3D positioning by assembling DNA origami onto substrates followed by silicification, enabling vertical alignment (Fig. 2g, h). Similarly, Teng et al. demonstrated programmable 3D origami superlattice assembly on oxide surfaces in 2025121.

DNA origami-enabled nanogaps facilitate microscopic studies of molecular optical properties and chirality122,123,124. In 2018, Gür et al.122 achieved sub-2 nm gold nanoparticle spacings using DNA origami, suppressing propagation losses inherent in lithographic techniques. Ma et al.123 constructed quasi-planar chiral satellite-core nanostructures in 2022, surrounding a central AuNP with six AuNRs on 2D origami sheets, revealing in-plane and out-of-plane chiral interactions under optical spin excitation.

Dynamic molecular junction

Dynamic junction techniques, highly sensitive methods for precise single-molecule conductance measurement and dynamic behavior analysis, enable real-time electrode spacing modulation through mechanical feedback or electromechanical control. Compared to static junction approaches, dynamic techniques offer distinct advantages: precise electrode gap control via real-time tip positioning to ensure stable molecular bridging; high stability and noise immunity; dynamic process monitoring to capture conductance evolution during junction formation, revealing molecular conformational changes and rupture kinetics; and statistical reliability through thousands of contact-withdrawal cycles for robust conductance histogram analysis. Currently reported dynamic junction platforms include STM-BJ (scanning tunneling microscopy break junction), AFM-BJ (atomic force microscopy break junction), MCBJ (mechanically controllable break junction), and MEMS-BJ (microelectromechanical system break junction), each of which will be elaborated in detail below.

STM-BJ

STM-BJ evolved from conventional scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) through instrumental modifications, employs a dynamic electrode pair comprising a metallic tip and gold substrate. Piezoelectric ceramics control tip retraction to create nanoscale gaps, which capture bridging molecules to form metal-molecule-metal junctions when the gap matches molecular dimensions (Fig. 3a, b)125. Xu et al. pioneered this technique, enabling rapid acquisition and screening of electrical signals through repeated molecular capture-dissociation cycles. Conductance histograms statistically analyze thousands of conductance traces, extracting intrinsic conductance values for molecules such as 4,4′-bipyridine126,127. Beyond direct tip-substrate contact, Haiss et al.128 demonstrated a “soft-contact” mode where the tip hovers near the substrate without physical contact, retracting only after molecular bridging.

a Schematic of a molecular junction formed via STM-BJ technique. b One-dimensional conductance histograms of L2-PF6 under different bias voltages applied between a gold tip and substrate. a, b reproduced from ref.328, copyright 2024, with permission from Springer Nature. c Structural diagram of a single-molecule junction measured using AFM-BJ. d Two-dimensional force-displacement histogram derived from single-molecule junction rupture point measurements. c, d reproduced from ref.329, copyright 2023, with permission from Wiley. e Upper panel: Supramolecular diode constructed from Py/NDI (pyrene/naphthalene diimide); lower panel: MCBJ fabrication process. f Representative current-voltage (I–V) curves corresponding to distinct conductance states. e, f reproduced from ref.330, copyright 2025, with permission from American Chemical Society. g Schematic of the MEMS-BJ platform. h Conductance histogram for 8,653 unselected tapping curves of gold-gold contacts, with six representative junction formation curves illustrated in the inset. g, h reproduced from ref.185, copyright 2020, with permission from Wiley

STM-BJ has become indispensable for probing electronic transport properties of molecular junctions47,129,130,131,132, catalyzing advancements in molecular electronics. In their 2025 study, Jia’s team129 employed sensitive STM-BJ techniques combined with SAPT theoretical calculations to analyze and further modulate complex vdW interactions within single-dimer junctions. They also revealed that applied electric fields significantly alter dimer configurations and conductance. Separately, Li’s group130 utilized ECSTM-BJ to measure and regulate molecular energy levels, demonstrating the role of antiaromaticity in single-molecule charge transport. This work offers new insights for designing bipolar devices.

Beyond charge transport, STM-BJ has expanded into spin electronics, thermal transport, nanolithography, and optoelectronics. Li et al.133 developed an electrochemically assisted jump-to-contact STM-BJ (JTCSTM-BJ) method, fabricating robust Fe-terephthalic acid (TPA)-Fe spin junctions. Applying in-plane or out-of-plane magnetic fields, they observed a 53% giant tunneling anisotropic magnetoresistance (T-AMR), advancing atomic-scale spin studies. Addressing thermal transport challenges, Lee et al.134 integrated customized probes with nanothermocouples, revealing asymmetric heat dissipation in molecular junctions dependent on bias polarity and majority carrier type.

In 2023, Lu et al.135 devised a coaxial focused electrohydrodynamic jet (CFEJ) printing technique using STM probes, enabling large-scale, precise fabrication of organic semiconductor nanowires on flexible substrates without lithography. For photocurrent studies, Imai-Imada et al.136 combined STM with tunable laser-driven localized plasmonic fields in 2022, exciting single free-base phthalocyanine (FBPc) molecules to detect first-excited-state tunneling electrons, demonstrating bias-sensitive control over photocurrent directionality and spatial distribution.

AFM-BJ

AFM-BJ represents another critical approach for nanogap formation using scanning probe microscopy. Unlike STM-BJ, which relies on tunneling current feedback to adjust electrode spacing and risks molecular structural damage from excessive probe forces during repeated stretching, AFM-BJ employs a force feedback mechanism. This system maintains non-contact between the conductive probe and substrate while monitoring cantilever deflection to track mechanical responses during molecular stretching, thereby minimizing molecular compression and tunnel current-induced damage (Fig. 3c, d).

In 2000, Wold et al.137 pioneered conductive AFM (CP-AFM) by coating AFM tips with metal to form metal-molecule-metal junctions with alkanethiol monolayers on gold substrates, enabling AFM-based electronic transport measurements138,139,140,141,142. Beyond electronics, AFM’s unique mechanical sensitivity facilitates studies of molecular mechanical properties—chemical bond strength, intermolecular forces, and force-electric coupling effects143. Frei et al.144 employed modified CP-AFM to investigate rupture forces in alkanes terminated with four distinct chemical groups, revealing that thiol-terminated molecules induce electrode restructuring via Au-S bond formation, yielding unique conductance and mechanical signatures.

AFM also advances nanolithography145 and molecular imaging146, though conventional metal-coated tips suffer from limited lateral resolution due to conical geometry and tip degradation147,148. Carbon nanotube (CNT)-functionalized AFM probes offer superior wear resistance, nanoscale diameter, and high aspect ratios, yet CNT growth methods face complexity and poor controllability149,150,151,152. In 2021, Cheng et al.153 achieved a 93% yield in synthesizing single high-quality CNTs on AFM tips by adjusting trigger thresholds for solution-based growth, enabling precise measurements of intricate nanostructures with enhanced aspect ratios and resolution.

MCBJ

MCBJ generate molecular junctions through lateral electrode stretching, distinct from the longitudinal configurations formed by SPM-BJ techniques. The conceptual precursor to MCBJ emerged in 1985 when Moreland et al.154 fractured a Nb–Sn filament on a flexible glass substrate to create an electronic tunneling junction. Müller et al.155,156 formally introduced the MCBJ concept during investigations of quantum conductance in noble metals. In 1997, Reed et al.157 first applied MCBJ to molecular electronics, successfully measuring the conductance of benzene-1,4-dithiol.

The core functional unit of a classic MCBJ system typically consists of a pre-notched metallic microbridge fabricated via lithography then electron-beam deposition on a flexible polyimide substrate, anchored by symmetrically distributed support structures. During operation, a piezoelectric actuator applies nanoscale vertical displacement (Z-axis), transmitting substrate deformation to the microbridge via a three-point bending mechanism. Stress concentration at the notch induces plastic deformation, and continued bending progressively stretches the metallic bridge until fracture, producing a pair of atomic-scale electrodes with precisely controlled spacing (Fig. 3e, f). The system achieves nanoscale precision through macroscopic mechanical control, offering unique advantages in single-molecule studies: (a) the elastic substrate and closed-loop piezoelectric control provide superior mechanical stability compared to STM-BJ158,159,160; (b) pristine molecular junctions form without additional chemical treatments161,162; (c) sub-angstrom reversible gap adjustment enables repeated junction formation163,164,165.

Reported MCBJ fabrication methods fall into three categories: mechanical cutting, electrochemical deposition, and nanolithography. Mechanical cutting, an early low-cost approach, involves manually scoring epoxy-fixed metal wires on flexible substrates155,161. While simple and equipment-minimal, this method suffers from contamination risks, poor mechanical stability, and insufficient precision for molecular-scale studies. Electrochemical deposition significantly improved these limitations. Yi et al.166 pre-patterned wide electrode gaps on silicon substrates in 2010 and narrowed them via electrochemical gold deposition under PMMA encapsulation, producing stable nanoelectrodes with reduced contact areas. To enhance vibration resistance, nanolithography was integrated into MCBJ fabrication. van Ruitenbeek et al.167 employed electron-beam lithography with PMMA resist in 1996 to fabricate Al and Cu electrodes, achieving high reproducibility and scalability168,169.

A critical advancement was the integration of gate electrodes, transforming two-terminal into three-terminal devices. Two-terminal configurations only probe molecular states relative to one electrode’s Fermi level, whereas three-terminal systems enable independent tuning of molecular states relative to both electrodes. Existing gate designs include back-gate and side-gate architectures. In 2005, Champagne et al.170 pioneered back-gate structures using degenerately doped Si substrates coated with SiO2, followed by e-beam lithography and HF etching to suspend metallic nanowire with a sub-40 nm molecule-gate distance. By 2013, Xiang et al.169 developed side-gate architectures, positioning non-contact electrodes nanometers from molecular junctions to directly modulate charge transport via applied electric fields without mechanical compromise.

MCBJ’s structural versatility facilitates broad applications in molecular conductance measurement171,172,173,174,175, spin-state control176,177,178, and vibrational studies179,180. Its compatibility with complementary techniques further enhances functionality. Combined MCBJ-Raman spectroscopy181 demonstrated accelerated nanoscale Menshutkin reactions via rational system design, exceeding macroscopic benchmarks by 104-fold and substantiating electrostatic catalysis mechanisms at confined interfaces. Concurrently, Zhao et al.182 developed a fiber-based break junction (F-BJ) technique, enabling in situ probing of single-molecule photoconductance through optical waveguides and establishing a novel paradigm for light-molecule interaction studies at the single-molecule level.

MEMS-BJ

Current techniques for constructing molecular junctions face inherent limitations such as operational complexity and low yield, driving researchers to develop more reliable methodologies. Microelectromechanical Systems (MEMS), a novel technology that integrates microscale mechanical structures, sensors, actuators, and electronic circuits onto a single chip via micro/nanofabrication183, offers a promising solution. The core principle involves using semiconductor processes, such as photolithography, thin-film deposition, and ion etching, to fabricate micron-scale (1–100 μm) mechanical components on diverse substrates, enabling synergistic operation with signal-processing circuits. MEMS excels in miniaturization, low power consumption, cost-effective batch production, and multifunctional integration. Its fabrication workflow is compatible with tranditional semiconductor manufactering processes, allowing mass production of tens of thousands to millions of devices on a single wafer, significantly reducing per-unit costs184.

In 2020, Jeong et al.185 pioneered the application of MEMS to molecular junction fabrication, termed MEMS-BJ. They employed this technique to study the electronic properties of 1,6-hexanedithiol and biphenyldithiol, as well as junction stability under ambient and cryogenic conditions (Fig. 3g, h). However, MEMS development faces challenges in multi-physics (mechanical-electrical-thermal) coupling design complexity, encapsulation reliability (e.g., dust/humidity resistance), and high-precision manufacturing consistency, necessitating further exploration and optimization.

Similarly, Scheer et al.186 developed two methods for in situ tuning of in-plane electrode gaps with Ångström-scale resolution: leveraging laterally expanding piezoelectric sheets or deformable polymeric substrates. This technology evolved into planar molecular break junctions capable of >10,000 reversible opening/closing cycles, enabling reproducible electrical characterization of benzenedithiol (BDA) molecules. This approach provides critical insights for bridging single-molecule science and nano-optical field modulation technologies.

In summary

STM-BJ plays a pivotal role in single-molecule electron transport studies due to its operational simplicity and ease of implementation, making it the most widely adopted method. AFM-BJ enables quantitative bond energy analysis via synchronized mechano-electrical detection, yet operational complexity restricts its broad adoption. MCBJ excels in sub-picometer control and wide-temperature operation, ideal for quantum transport under extreme conditions, but requires complex and expensive micro/nanofabrication processes for device preparation, which are time-consuming. MEMS-BJ enables high-throughput automation and chip integration, yet the suspended MEMS structures constrain applications in solution phase environment for reliable BJ measurements, which introduces capillary forces that can potentially damage the MEMS cantilevers. Technique selection should thus align with specific research objectives.

Atomic manufacturing methods

Synergistic interface and intermolecular interactions

The construction of molecule–electrode interfaces plays a decisive role in forming stable and reliable molecular junctions, as interfacial interactions not only determine coupling strength but also govern charge transport properties and mediate environmental modulation of electron transfer187,188,189. These interfaces typically involve molecules functionalized with anchoring groups that bind to electrodes via covalent or non-covalent interactions. The concept of covalent bonds, first proposed by Langmuir in 1919190, describes strong intermolecular interactions formed through shared electron pairs. In contrast, non-covalent bonds, including coordination bonds, hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and other secondary interactions, exhibit weaker strength but critically influence interfacial behavior. The following sections elaborate on these two interaction classes within molecular junctions.

Covalent interactions

Covalent bonding interactions primarily utilize diverse terminal functional groups as anchoring moieties to bridge molecular junctions between electrodes. Thiol groups (–SH), the earliest and most extensively studied anchoring groups45,191, dominate due to their straightforward synthesis and strong Au–S bonding affinity, which enhances junction formation probability. However, Au–S covalent bonds in single-molecule applications face limitations: (a) Ideal bond formation occurs exclusively in solution due to hydrogen’s critical role in thiol functionality, restricting environmental adaptability; (b) Thiol oxidation alters molecular structures, destabilizing junctions; (c) The higher Au-S bond strength relative to Au–Au induces electrode surface restructuring, complicating interfacial properties46.

To address these challenges, researchers have explored alternative anchoring groups. In 2010, Xing et al.192 substituted thiols with dithiocarboxylate groups (–CSSH) in phenylethynylene molecular wires, observing enhanced electrode coupling and reduced charge transport barriers. Zeng et al.193 demonstrated in 2020 that thioacetyl groups (R-SAc) enable selective junction formation in mixed solvents, with applied bias modulating molecular dipole orientation to improve yield (Fig. 4a, b). Similarly, methylthiol (R-SMe)194 and thiophenyl groups195 exhibit analogous selectivity.

a Schematic illustration of the STM-BJ device and the construction of molecular junction under an external electric field and the anchoring groups corresponding to M1-M5, respectively. M1 and M2 (-SMe), M3 (-SAc), M4 (-NH2), and M5 (-PY). b Plots of the junction formation probability of M1 (green), M2 (red), M3 (purple), M4 (orange), and M5 (blue) versus applied biases. The error bar is determined from the chip-to-chip variation of three independent experiments. a, b reproduced from ref.193, copyright 2020, with permission from Wiley. c Schematic of the single-molecule junction constructed by WTe2 electrodes and the molecular structure of M-TPP. d 1D conductance histograms for M-TPP (M = Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn) and TPP single-molecule junctions. c, d reproduced from ref.212, copyright 2023, with permission from American Chemical Society. e Schematic illustration of the preparation of photosensitizer-assembled nanocluster. f Representative TEM photographs of C3TH nanocluster. e, f reproduced from ref.220, copyright 2025, with permission from Wiley

Nitrogen-based groups, including amines (R-NH₂)196, pyridines (R-Py)197, and imidazoles198, represent a second major category. In 2006, Venkataraman et al.199 showed that diamine-terminated molecules form isotropic Au-N bonds via lone-pair interactions, yielding consistent conductance across junction types, resolving variability issues in dithiol-Au systems.

Carbon-based anchors, such as alkynes200, methylene groups201, and fullerenes173, offer another pathway. Hong et al.202 pioneered in 2012 the use of trimethylsilyl (TMS)-protected alkynes, which generate Au-C σ-bonds via in situ cleavage. These junctions exhibit higher conductance than thiol-based analogs while eliminating toxic precursors.

Oxygen-containing groups like carboxyl (–COOH)203, nitro (–NO₂)204, and ester/ether derivatives205 complete the fourth category. Building on earlier carboxyl-Au studies, Peng et al.206 employed ECSTM-BJ to systematically analyze alkanedicarboxylic acids on Cu/Ag electrodes, revealing conductance dependencies on molecular length and electrode-specific electronic coupling.

Non-metallic electrodes expand interfacial design. Carbon-based interfaces often utilize carboxyl-amine amide bonds, as detailed in prior CNT/graphene junction discussions. Vezzoli et al.207 demonstrated GaAs–molecule–Au junctions via As–S covalent bonds, where GaAs doping modulates electronic properties, while direct bandgap characteristics enable optoelectronic applications. Silicon electrodes, explored by Peiris et al.208, form durable Si–C bonds with diazonium radicals, achieving room-temperature junction lifetimes (1.1 s) exceeding Au–S bonds. These mechanically stable junctions enable precise I–V characterization and rectification control, circumventing Au’s intrinsic limitations.

Non-covalent interactions

Non-covalent interactions, though weaker than covalent bonds, enable spontaneous formation of ordered structures under mild conditions (e.g., solution-phase self-assembly) and permit reversible structural modulation of molecular junctions in response to external stimuli such as light, heat, electric fields, or chemical environments. This dynamic tunability addresses the rigidity of covalent bonds, opening new dimensions for functional molecular device design. This section briefly introduces common non-covalent interactions in molecular junctions: coordination bonds, van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds, and π-π interactions.

Coordination bonds in molecular devices typically involve terminal groups acting as electron donors, pairing lone electron pairs with vacant orbitals of metal electrodes188. In 2019, Vladyka et al.209 demonstrated in situ formation of 1D coordination polymers within junctions using MCBJ. The high affinity and anisotropic binding of isocyanide-terminated groups to gold atoms significantly improved junction formation efficiency.

Hydrogen bonds, intermediate in strength between covalent and van der Waals interactions, balance structural stability with responsiveness to temperature, solvent polarity, or pH. This allows dynamic control over junction properties210. In 2016, Wang et al.211 investigated quadruple hydrogen bonds in UPy derivatives functionalized with thiol (–SH), pyridyl (–Py), and amino (–NH₂) groups. Thiol-terminated molecules exhibited the highest conductance, while solvent polarity modulated hydrogen bond formation. Directional specificity of multiple hydrogen bonds enhanced binding strength and preserved molecular conjugation.

Van der Waals forces, the weakest yet most ubiquitous interactions, govern junction assembly and dynamics via transient dipole-induced attractions. In systems lacking strong covalent/hydrogen bonds, their nondirectional and short-range nature enables weak coupling for self-assembly and synergizes with other forces to enhance mechanical stability. In 2023, Lu et al.212 constructed transition metal dichalcogenide (TMDC) molecular devices solely via van der Waals interactions, avoiding interfacial chemical bonds (Fig. 4c, d). This approach boosted conductivity (~736%) and enabled broad conductance modulation by varying metal centers.

π–π interactions, driven by delocalized π-electron clouds in aromatic systems, exhibit strength surpassing van der Waals forces but below covalent bonds. Their directional and distance-sensitive nature promotes ordered self-assembly of π-conjugated molecules (e.g., porphyrins, acenes, fullerene derivatives) through π-orbital overlap, reducing interfacial energy barriers and enhancing charge delocalization for improved conductivity and carrier mobility213. In 2015, Yoshida et al.214 used conductive scanning AFM (CSAFM) to track conductance and rupture forces in aromatic diphenylacetylene derivatives. Pyridyl-terminated molecules formed high-conductivity coplanar connections with gold electrodes via π–π interactions, exhibiting lower conductance and rupture forces compared to other terminal groups.

Self-assembly

Non-covalent interactions between molecules drive the self-assembly of molecular devices, enabling spontaneous formation of ordered structures with specific spatial arrangements and functionalities without external intervention (Fig. 4e, f). The essence of self-assembly lies in leveraging weak intermolecular forces to achieve macroscopic-scale order. This bottom-up strategy transcends the resolution limits of traditional lithography, offering energy-efficient pathways to fabricate electronic devices with molecular-scale precision.

Biological macromolecules, such as DNA and proteins, play pivotal roles in self-assembled molecular junctions due to their inherent molecular recognition capabilities and structural programmability215. DNA’s utility, particularly through DNA origami, has been extensively discussed in prior sections on nanogap fabrication. Proteins, with their precise and complex architectures, can guide directional alignment of biomolecular components via specific interactions, forming stable junctions. In 2005, Alessandrini et al.216 demonstrated the feasibility of constructing single-molecule bio-transistors using disulfide-bonded Azurin proteins under physiological humidity. They further showed that altering the protein’s oxidation state could modulate rectification. By 2013, Raccosta et al.217 enhanced this design by attaching 5 nm gold nanoparticles (GNPs) to Azurin proteins, assembling them onto gold electrodes. Conductive probe atomic force microscopy (CP-AFM) revealed that this optimized top-contact configuration improved current stability and reduced the mechanical force required for reliable electrical characterization.

Beyond natural biomolecules, zwitterionic materials have emerged in recent studies as promising candidates for self-assembled molecular junctions. These materials, featuring spatially separated positive and negative charges, often serve as interfacial mediators. Their unique charge distribution enhances junction stability through synergistic non-covalent interactions with electrodes or adjacent molecules. Zwitterions’ high hydrophilicity and anti-fouling properties mitigate environmental interference from moisture or contaminants, while their bipolar charge distribution suppresses electrostatic repulsion-induced aggregation, promoting densely packed monolayers for homogeneous junctions218. In 2014, Wu et al.219 explored the role of hydrophilic counteranions in directing the self-assembly of cationic bola-amphiphiles. They found that zwitterionic interactions facilitated 2D planar aggregates, with aggregate morphology tunable via counteranion substituents and organic chain lengths, offering strategies for controlled molecular device assembly. A study by He et al.220 highlighted zwitterionic self-assembly in biomedical applications. They designed nanoclusters from self-assembling zwitterionic small molecules, where cross-aligned molecular arrangements minimized intermolecular electron-vibration coupling. This configuration enhanced light-induced electron transfer, triggering self-ionization to generate cationic and anionic PS radicals with potent antimicrobial efficacy.

Functional molecular electronic devices

In the field of molecular electronics research, its central scientific objective focuses on constructing single-molecule-scale devices with tailored electrical functionalities through atomic precision manufacturing techniques, combined with the precise design of molecular architectures and synergistic modulation of interfacial states, ultimately aiming to realize integrated circuit systems based on single-molecule units. Although current technologies have yet to fully overcome critical bottlenecks in device integration, significant progress has been achieved at the fundamental component level. This advancement is attributed to continuous breakthroughs in the foundational theories of molecular electronics and innovations in characterization techniques. Core functional units such as molecular switches with reversible switching characteristics, molecular diodes demonstrating rectification effects, and gate-voltage-modulated molecular transistors have been successfully implemented. This section will systematically review recent research advances in major functional molecular devices, emphasizing their operational mechanisms and technological implications.

Molecular switch

The electronic switch stands as one of the most pivotal components in circuits, operating through the reversible switching of materials between two stable states. Molecular switches achieve conductance modulation via transitions in molecular conformation or electronic states. As detailed in recent reviews221, this necessitates functional molecules to exhibit at least two stable isomers that can reversibly interconvert under external stimuli222. For example, optical stimulation induces photoisomerization, charge manipulation alters molecular charge states through redox reactions, and mechanical stimuli provoke conformational changes via stretching or compression. Notably, molecular switches can be simultaneously triggered by multiple stimuli, enabling synergistic effects223. These mechanisms furnish diverse switching strategies for molecular electronics, propelling the advancement of highly integrated nanodevices224,225.

Photoischromic molecular switches enable conductance modulation through photoresponsive conformational changes of molecules, whose operational mechanisms hold significant research value in the field of molecular electronics. Taking the diarylethene system as an example, research teams have substantially reduced the effective coupling strength between the molecule and electrodes by introducing three methylene (CH2) units on both sides of the molecular backbone. Experimental results demonstrate that under a gate voltage of 0 V and source-drain bias of ±1 V, the current switching ratio of this molecular switch can be enhanced to approximately 100-fold. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, when single-molecule switch devices are exposed to UV and visible light irradiation, the diarylethene molecules exhibit reversible interconversion between closed-ring and open-ring configurations, with current response curves displaying pronounced real-time switching behavior226. Furthermore, in photo-controlled molecular junction systems, azobenzene derivatives have emerged as critical research targets due to their synthetic accessibility and chemical stability227. These molecules consist of two benzene rings connected by an azo (–N = N–)-bond, whose trans-cis configurational isomerization can be reversibly regulated via light irradiation. Studies confirm that under low-bias conditions, this isomerization process triggers asymmetric stochastic conductance switching phenomena228. Additionally, spiropyran systems featuring dual photo/chemical responsiveness exhibit unique isomerization modulation mechanisms. Experimental investigations reveal that bifunctional spiropyran derivatives achieve rapid reversible isomerization transitions in bulk solutions through photoexcitation or chemical stimuli, accompanied by significant conductance switching between high and low conductance states229.

a Schematic of a graphene-diarylethene-graphene reversible photoswitching molecular device (left) and I–V curve of open/closed state and photocurrent response curve(right), reproduced from ref.226, copyright 2016, with permission from American Association for the Advancement of Science. b Schematic illustration of the electrochemically gated break junction experiment (left) and molecular structure of NDI-BT in the neutral state, radical-anion state and dianion state (right), reproduced from ref.231, copyright 2015, with permission from Wiley. c Schematic illustrating the reversible transformation of a neutral or negatively charged Sn-up molecule via a planar molecule geometry to a Sn-down molecule (left) and time series of tunneling current measured on a Sn-up molecule with open feedback loop (right), reproduced from ref.232, copyright 2009, with permission from American Chemical Society. d Schematic of the hydrogen tautomerization reaction responsible for the switching (left) and current trajectory was obtained when the tip of STM was located at one end of the molecule (right), reproduced from ref.233, copyright 2020, with permission from American Chemical Society. e As the molecule unfolds/refolds, the average conductance reversibly changes over three orders of magnitude, reproduced from ref.235, copyright 2011, with permission from American Chemical Society. f Schematic of a single-molecule pulling/molecular electronics setup (left) and the change of conductance corresponding to the molecular conformation change (right), reproduced from ref.236, copyright 2011, with permission from American Chemical Society

Charge-regulated molecular switches can be categorized into three distinct classes based on their redox mechanism: electrochemical gating systems, charge-transfer-driven systems, and electron-induced switching systems230. The core mechanism of electrochemical gating lies in the precise modulation of the electrode Fermi level to alter the redox state of molecular functional units, thereby achieving high-precision switching functionality. Taking the NDI-B molecular system as an example (Fig. 5b), this molecule enables reversible transitions between neutral (NDI-N) and dianionic (NDI-D) states through electrochemical gating techniques. Experimental studies confirm that this system exhibits tri-state charge storage characteristics, with marked conductivity differences between charge states, and allows reversible switching between any two states via fine-tuned molecular potential control231. In the domain of charge-transfer-driven switches, research demonstrates that phthalocyanine molecular layers adsorbed on metal electrode surfaces can establish bistable switching systems. These systems induce reconstruction of intramolecular charge distribution through resonant electron or hole injection into molecular orbitals, subsequently triggering vertical displacement modulation of the central tin ion. Ordered lamellar array architectures based on this charge-transfer mechanism have achieved reversible conductance switching at the single-molecule scale for the first time232 (Fig. 5c). Electron-induced switching operates through current-driven energy excitation to activate molecular conformational transitions. As shown in Fig. 5d, combined density functional theory (DFT) calculations and spectroscopic analyses reveal that the switching effect originates from the tautomerization process of the imino hydrogen within the molecular central cavity. Notably, the observed switching behavior in confined environments, such as step edges and molecular arrays, excludes the possibility of whole-molecule rotation, confirming the dominant role of hydrogen positional rearrangement233.

Mechanically controlled switches, as critical modulation mechanisms in molecular/atomic devices, enable conductance switching through mechanical force-induced molecular conformational transitions, interfacial contact evolution, and charge state manipulation. Their operational mechanisms primarily involve three dimensions: molecular conformational reorganization altering electron transport pathways, dynamic evolution of molecule–electrode interfaces modulating electron coupling efficiency, and mechanical stress-induced charge state shifts in molecules. Studies demonstrate that factors including molecular isomer configuration differences, spatial distribution of redox-active sites, and structural deformations under external forces (e.g., molecular folding/twisting, dihedral angle variations from stretching/compression) significantly regulate device conductance characteristics233,234. Experimentally, research teams have achieved precise manipulation of folding-extension conformational transitions at the single-molecule scale by integrating conductive atomic force microscopy (C-AFM) with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Upon transitioning from folded to extended states, the molecular system exhibits reversible conductance modulation spanning three orders of magnitude, demonstrating exceptional mechano-electrical responsiveness235 (Fig. 5e). Theoretical simulations further reveal counterintuitive quantum transport behavior in a model molecule comprising complementary aromatic moieties (1,4-naphthoquinone) interconnected via ether linkages. During mechanical stretching, the tunneling current displays a non-monotonic increase with applied force (Fig. 5f), challenging conventional frameworks of molecular force-electronic coupling236.

Molecular diode/rectifier

Molecular diodes, as core functional units in molecular electronics, exhibit a rectification mechanism sharing physical homology with semiconductor p-n junctions. By constructing molecular-scale heterojunctions of p-type and n-type doped materials to achieve unidirectional charge carrier transport characteristics—forming highly efficient conductive channels under forward bias while demonstrating high impedance under reverse bias—they display rectification effects comparable to macroscopic diodes237,238. Importantly, while realizing diode functionality requires novel molecular designs and diverse operational conditions, gating the diode behavior remains equally critical239. Current molecular rectifier architectures have expanded across material systems including quantum-confined structures in single-molecule systems, interface engineering strategies utilizing SAMs, and band-alignment regulation designs in heterojunction composites. These architectures successfully realize controllable rectification behavior spanning nanoscale to mesoscale through precise modulation of molecular orbital energy level alignment, interfacial dipole orientation, and spatial charge distribution240,241.

The electrode-molecule-electrode architecture of single-molecule rectifiers, representing the ultimate manifestation of molecular electronics, confronts dual scientific challenges in quantum confinement effects and interface coupling modulation. These nanoscale systems exhibit unique quantum tunneling transport characteristics, with rectification performance metrics surpassing the physical limitations of conventional semiconductor devices. Although precise control of molecular-electrode interfaces remains a significant technical bottleneck, breakthrough advancements in nanomanipulation techniques have provided critical support for high-reproducibility device fabrication. Employing STM-BJ technology, the research team achieved stable assembly of 1,8-nonadiyne molecules on low-doped silicon electrode surfaces. Experimental results demonstrate that this single-molecule rectification system attains a rectification ratio exceeding 4 × 103 under ambient conditions, comparable to traditional silicon-based diodes. This breakthrough enables performance compatibility between single-molecule devices and conventional semiconductor circuits, establishing fundamental technical frameworks for molecular-semiconductor hetero-integration (Fig. 6a)242. Notably, subsequent studies utilizing CP-AFM revealed that environmental humidity (5–60%) can dynamically modulate the rectification ratio by three orders of magnitude (103) in ruthenium polypyridyl complex monolayers fabricated on indium tin oxide substrates. This tunable characteristic provides novel insights for developing environment-responsive molecular devices (Fig. 6b)243.

a 1,8-Nonodiyne: Chemical structure and self-assembled monolayer formation on H-Si via UV-assisted hydrosilylation (left) and current-voltage properties of single-nonadiyne junctions (right), reproduced from ref.242, copyright 2017, with permission from Springer Nature. b Schematic representation of the 2-Ru-N ITO-molecule-ITO junction (left) and logarithmically binned RR for the humid case (right), reproduced from ref.243, copyright 2018, with permission from Springer Nature. c Schematic of alkanethiolate SAMs: SC11Fc (ferrocene headgroup) vs. Fc-free controls (SC10CH3, SC14CH3) for charge transport, reproduced from ref.74, copyright 2009, with permission from American Chemical Society. d Schematic of Ag-SAM//GaOx/EGaIn junction (left) and J (V) curve with R1/R2 conductance states and W/R/E voltages (right), reproduced from ref.247, copyright 2020, with permission from Springer Nature. e Schematic of MoS₂|MPc heterojunction via electrostatic adsorption (left) and J(V) rectification curves for MoS₂|MPc vs. MPc|MoS₂ with single molecule magnets alignment-induced orbital modulation (right), reproduced from ref.251, copyright 2017, with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry. f Representative I-V characteristics (left) and statistical histograms of RR for OPT2/1L-MoS2 and OPT2/1L-WSe2 junctions (right), reproduced from ref.252, copyright 2020, with permission from Springer Nature. g Schematic representation of the gMCBJ principle (left) and Scanning electron micrographs of a gMCBJ sample (right). h I–V characteristics (left) and corresponding gate-induced rectification ratio modulation (right) at different gate voltages. g, h reproduced from ref.253, copyright 2016, with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry

SAMs rectifiers, as archetypal two-dimensional molecular devices, demonstrate significant advantages in functional integration and engineering applications. Compared with single-molecule systems, this technical approach offers superior characteristics including simplified fabrication processes, enhanced structural stability, scalable production compatibility, and cost-effectiveness244. Through interface engineering strategies, high-density ordered molecular layers can achieve controlled assembly on diverse substrates spanning metals, oxides, and oxygen-free silicon surfaces245. Among these, thiol/dithiol-based molecular systems have emerged as preferred materials for large-area molecular architectures due to their strong affinity with noble metal electrodes, excellent fabrication reproducibility, and structural design flexibility246. Although thiol-based SAMs face limitations such as prolonged assembly time, structural defects, and interfacial coupling degradation caused by chemical oxidation, precise rectification behavior can still be engineered through molecular structure optimization and electrode property modulation42. The rectification mechanism fundamentally correlates with molecular backbone length. The hydrocarbon chain not only determines tunneling barrier thickness but also regulates charge transport pathways through conformational uniformity. A pivotal breakthrough was achieved in 2009 by the Nijhuis group, who constructed alkylthiol monolayers terminated with ferrocene groups between silver and eutectic GaIn electrodes, realizing a rectification ratio of ~102 under ±1 V bias74 (Fig. 6c). Mechanistic studies revealed that this performance originates from asymmetric alignment of the ferrocene unit’s highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) within the junction, enabling resonant tunneling channels under negative bias70. Recent advancements transcend the single-energy-level tunneling paradigm by integrating resistive switching with rectification functionalities. As shown in (Fig. 6d), the Ag/GaIn heterojunction incorporating S(CH₂)₁₁MV2+X⁻2 molecules (MV2+: methyl viologen dication, X⁻: counterion) achieves an exceptional rectification ratio of 2.5 × 104 while maintaining a resistive switching ratio of 6.7 × 103, demonstrating synergistic diode-variable resistor characteristics247.

In the study of heterostructures for molecular rectifier devices, non-functionalized molecules have traditionally been excluded from the molecular diode paradigm due to their symmetric tunneling charge transport characteristics248. However, heterojunction interface band engineering can overcome this limitation by regulating band alignment to achieve asymmetric current-voltage (I–V) characteristics. Recent research has developed hybrid molecular junction and heterojunction design strategies that integrate inorganic materials (e.g., nanoparticles, two-dimensional semiconductors) with molecular films for functional synergy249. A representative case involves constructing n-ZnO/p-ZnO-organic molecule (Rose Bengal B or copper phthalocyanine)-mercury multilayer heterojunctions on n-type silicon substrates via electrostatic assembly250. This design leverages the donor properties of nanoparticles and the acceptor characteristics of organic molecules to achieve unidirectional charge transport and rectification effects through synergistic interplay. Another breakthrough design employs layer-by-layer electrostatic adsorption to fabricate metal phthalocyanine/MoS₂ heterojunctions (Fig. 6e)251. Here, the 3d orbital characteristics of central metal atoms in phthalocyanines determine magnetization vector intensity. Following external magnetic field-induced planar orientation alignment of molecular layers, polyallylamine cationic layers are utilized for orientation fixation. This alignment regulation significantly modifies molecular orbital energy level distributions and optimizes charge transfer pathways at electrode-phthalocyanine interfaces, enabling precise control over interfacial energy level alignment and rectification performance. Organic-inorganic heterointerface studies have further revealed critical principles: Thiol-based SAMs on gold substrates coupled with transition metal dichalcogenides (MoS₂/WSe₂) exhibit pronounced rectification characteristics (Fig. 6f)252. While biphenyl-4-thiol (OPT2) SAMs alone demonstrate near-unity rectification ratios (≈1), their integration with MoS₂ and WSe₂ enhances rectification ratios to 1.79 × 103 and 2.3, respectively, under ±1 V bias. These results conclusively demonstrate the decisive role of heterointerface band engineering in establishing asymmetric transport properties in molecular devices.

Compared to traditional fixed molecular rectifying structures, three-terminal gated devices constructed using the MCBJ technique provide molecular diodes with in situ electrical tunability. As demonstrated by Perrin et al. using the gateable mechanically controllable break junction (gMCBJ) technique, the DPE-2F single-molecule rectifier (Fig. 6g) utilized a gate electrode to precisely regulate the relative alignment between molecular orbitals and the electrodes’ Fermi levels. This enabled the first experimental verification of dynamically controllable rectification based on the dual-site quantum interference mechanism. At a cryogenic temperature of 6 K, the device exhibited a high rectification ratio of 600, with the gate voltage enabling continuous tuning of this ratio (Fig. 6h). The observed modulation behavior aligns remarkably well with the dual-site level alignment model predicted by DFT calculations253. This work not only transforms the Aviram-Ratner rectifier proposal into a dynamically operable molecular component but also reveals the decisive role of the synergistic effect between gate voltage, energy level alignment, and quantum interference on rectification performance. It establishes a key technological paradigm for developing next-generation programmable molecular integrated circuits.

Molecular transistor

As the core functional component of modern integrated circuits, transistors operate based on the principle of regulating current transport characteristics between source-drain electrodes through gate voltage modulation, where the gate channel length directly determines the ultimate integration density limit of devices. In the field of molecular electronics, the molecular system constructed within molecular junctions can be analogously regarded as the conductive channel in transistor gate architectures, sharing fundamental physical mechanisms with silicon-based transistors in terms of gate-modulated charge transport environments. Molecular transistors employing bottom-up assembly strategies can compress conductive channel dimensions to the sub-nanometer scale, overcoming the physical constraints of conventional photolithography and providing innovative solutions for ultrahigh-density integrated circuits. By systematically investigating gate-controlled rectification behavior, carrier mobility modulation mechanisms, and the influence of interfacial state density on switching ratios, research on molecular transistors will drive the paradigm shift in nanoelectronics from the microelectronic era to the molecular electronic era. These performance enhancements, including tunable rectification, high switching ratios, and sub-nanometer channel control, collectively provide crucial scientific support for expanding integrated circuit technology pathways in the post-Moore’s Law era.

Electrostatic-gated molecular transistors achieve silicon-like current modulation functions through gate electric field regulation of molecular orbital energy levels, whose core mechanism lies in the synergistic interaction between the molecular junction system and the gate dielectric layer. In 2000, Park et al.254 pioneered the construction of a three-terminal device using C60 molecules as conductive channels through electromigration technology, employing doped silicon wafers as gate electrodes. This groundbreaking work experimentally demonstrated for the first time that single-molecule systems could achieve significant alterations in current-voltage characteristics via gate voltage modulation. Notably, their single-C60 transistor exhibited quantized nanomechanical oscillations at ~1.2 THz (5 meV) with an ON/OFF conductance ratio of ~300. This work thereby established the experimental foundation for molecular transistor research (Fig. 7a). With advancements in nanofabrication techniques, Song et al.255 constructed molecular junctions of 1,4-benzenedithiol and 1,8-octanedithiol between gold electrodes in 2009, innovatively implementing a 3-nm-thick aluminum oxide gate dielectric layer. Their work demonstrated continuous modulation of molecular conductance through gate voltage application, with experimental data revealing a 0.25 eV shift in molecular orbital energy levels under 1 V gate bias, corresponding to a shift rate of ~0.25 eV/V via electrostatic gating. These data established a linear response model between gate voltage and orbital energy-level displacement (Fig. 7b), while also enhancing inelastic electron tunneling spectroscopy (IETS) intensity by over 30 times and yielding Γ ≈ 0.12 eV for HOMO resonance. Recent breakthroughs in theoretical simulation technologies have provided new insights for molecular transistor design. In 2020, Weckbecker et al.256 employed first-principles calculations to reveal the bistable conductive characteristics of molecular-graphene heterojunctions during photoinduced isomerization processes, demonstrating that external gate electric fields could precisely regulate molecular configurations and interfacial coupling states to selectively stabilize distinct conductance states, as evidenced by an achieved ON/OFF conductance ratio of ~20 at 0.05 V via proton-transfer gating, with HOMO energy at −2.0 eV and coupling strength Γ = 0.12 eV (Fig. 7c). These research advancements collectively validate the effectiveness of electrostatic gate control mechanisms at the molecular scale.