Abstract

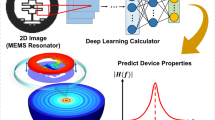

This study presents a novel approach for achieving linear motion in thermal micro-actuators by integrating machine learning-assisted optimized mechanical metastructures into the system design. Traditional solutions to actuator nonlinearity rely on complex sensor-based feedback mechanisms, which are often impractical in miniaturized systems. By embedding mechanical elements with tailored stiffness directly into the actuator structure, the proposed method transforms the inherent nonlinear relationship between input voltage and displacement into a near-linear response. A large design dataset was generated through finite element simulation and used to train a neural network model capable of predicting mechanical behavior across a broad design space. This model was then employed to guide inverse design and optimize geometrical parameters for specific performance goals. The optimized metastructures integrated with thermal actuators were fabricated via a Piezo-Multi-User MEMS Process (PiezoMUMP). Experimental characterization, conducted in a scanning electron microscope, confirmed that the fabricated device achieved an approximately 85% improvement in linearity compared to the original actuator. This enhanced performance enables more precise control of displacement in applications such as tensile testing of two-dimensional materials. The approach eliminates the need for sensors or electronic conrollers, offering a scalable and computationally efficient solution for improving actuator performance. The demonstrated methodology may be generalized to other actuation systems, opening new pathways for intelligent mechanical design enabled by data-driven optimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mechanical actuation is widely employed across diverse fields such as aviation, robotics, electronics, and medicine1,2. It involves transforming electrical, hydraulic, or thermal energy into mechanical motion3, resulting in various actuation mechanisms, including but not limited to electromagnetic actuators4, piezoelectric actuators5, hydraulic and pneumatic actuators6, and thermal actuators7. The practical application of these mechanisms depends on precise control and accurate prediction of their actuation movements. This is particularly critical in small-scale systems such as microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), where small errors or uncertainties in actuation can affect overall performance.

A key metric for actuation mechanisms is their input-output relationship, which describes how the applied input (e.g., voltage, current, magnetic field, or pressure) translates into the resulting output (e.g., displacement or force). Linearity is crucial for achieving high accuracy in controlling the behavior of these mechanisms. However, due to the complex design of these miniature devices and the coupling of different physical fields (e.g., electromechanical, magneto-mechanical, and hydro-mechanical), sophisticated control systems and feedback loops are often required to achieve a linear or pseudo-linear response. For instance, feedback loops are typically used to adjust the input signal based on real-time monitoring of discrepancies between the desired and actual outputs8. Although effective, incorporating sensing elements and developing the necessary circuits and control systems is costly and complex9, particularly in MEMS devices, which also make these systems more prone to fabrication challenges and potential failures10.

Take MEMS ETAs as an example. They have been an essential type of actuator under various contexts, such as achieving precise alignment in micro-optical components7,11, activating microvalves for microfluidic control12,13, characterizing nanomaterial properties14,15, and executing tasks that require submicron-precision motions16,17. Electrothermal actuators offer several advantages, including compactness18,19, low operating voltage20,21, compatibility with semiconductor fabrication processes19,22, and a high force or displacement to voltage ratio compared to electromagnetic, electrostatic, and piezoelectric MEMS actuators23,24. However, their inherent nonlinear relationship between the input voltage and the output actuation displacement due to a complex electro-thermo-mechanical coupling mechanism restricts their use in applications requiring linear motion25. The primary source of this nonlinearity is Joule heating. Because the generated heat is proportional to the square of the applied current or voltage, the relationship between applied voltage and actuation displacement becomes quadratic26. The temperature-dependent material properties of silicon, e.g., coefficient of thermal expansion, electrical resistivity, and thermal conductivity, further contribute to their nonlinear behaviors27,28. Variations in geometry during actuation, including deflection, buckling effects, and structural instabilities, can introduce additional nonlinearity29.

To linearize the behavior of MEMS ETAs, conventional approaches used in macro-scale devices have been investigated. These approaches often rely on feedback control systems or transducers to achieve linear actuation27,30. However, integrating sensors, such as capacitive and piezoresistive types, and control units introduces complexities, including susceptibility to crosstalk and practical challenges in fabrication and implementation31,32. Additionally, to achieve high sensitivity, the feature size and spacing of the sensing beams must be reduced to a few microns or smaller, making them vulnerable in applications. An important application of MEMS ETAs is to characterize the mechanical properties of nanomaterials, a process requiring material transfer onto the MEMS platform. Unfortunately, the sensing elements are often too delicate to withstand the harsh conditions of commonly used transfer processes, such as exposure to chemical baths or mechanical pressure33.

While voltage modulation techniques, such as applying a square root profile to the input voltage, can linearize the response of electrothermal actuators through external electronics, our approach provides a sensor-free, circuit-free alternative by embedding the linearization mechanism directly into the mechanical system. This work presents a new method for mitigating the nonlinear behavior of MEMS thermal actuators. Instead of utilizing sensors and feedback control systems, we demonstrated that near-linear responses can be achieved by integrating mechanical metastructures designed with the aid of machine learning models. By eliminating the need for real-time sensing, closed-loop feedback, or complex control electronics, our approach is particularly advantageous for space-constrained, low-power, or fully passive applications, such as implantable biomedical devices and remote MEMS sensors, where electronic solutions may be impractical. Additionally, the metastructure-based design allows for tunable actuation characteristics at the fabrication stage, ensuring repeatable and pre-defined responses without the need for runtime control. To develop an effective metastructure that ensures desired linear output within material limitations, we generated approximately 16,000 simulated models for each design configuration to serve as the training dataset. Using neural network (NN) optimization combined with an inverse design algorithm for geometrical parameter prediction34,35, we achieved the targeted near-linear output behavior for the overall system. The implemented metastructures serve as an extension of the actuator, offering several advantages: compatibility with mass production processes, customizability for tailored needs, and the absence of any requirement for additional power input or field stimuli. This lean design concept, which minimizes the integration of sensors and control systems in MEMS devices through the implementation of mechanical metastructures and the use of machine-learning models, has the potential to be applied to the development of other MEMS and even macro-scale actuation systems.

Results

Metastructures for displacement modulation

In MEMS devices, electrothermal actuation works by Joule heating. Applying voltage generates heat, which causes thermal expansion and drives actuation. (Fig. 1a). While a linear correlation between actuated displacement (ua) and applied voltage (V) is ideal, the observed displacement-voltage relationship is quadratic, i.e., ua ∝ V2 (Fig. 1b)26,30. To achieve the linear relationship between applied voltage and displacement, we propose integrating a mechanical metastructure with the actuator (Fig. 1c). This metastructure exhibits a square root relationship between the input displacement (ua), driven by the electrothermal actuator, and the output displacement (um). The combined effect of this square root relationship and the quadratic actuation mechanism is predicted to produce a linear relationship between the total displacement (uT) and the input actuation voltage (Fig. 1d).

a Schematic of the electrothermal actuator before (blue, dashed) and after (orange, solid) voltage application. b Voltage-displacement relationship of a typical electrothermal actuator with a nonlinear response (black, solid) and an ideal linear voltage-displacement relationship (red, dashed). c Integrating an add-on metastructure to achieve a linear input(voltage)/output(displacement) relationship. d Achieving linear voltage-displacement response through the combined quadratic (ETA) and square root (metastructure) actuation mechanisms. e Equivalent spring model of the hypothetical metastructure composed of two springs connected in series to modulate deformation: K1 and K2 exhibit softening and hardening behavior, respectively. f Hypothetical force-displacement responses of equivalent K1 and K2 considered in e through designs of a double clamped straight beam and an inclined beam that offer hardening and softening behavior, respectively

To design an effective metastructure, it is decomposed into two functional components. By modeling the system as two nonlinear springs connected in series with stiffnesses K1 and K2, we derive an equivalent formula to determine the stiffness for each component (Fig. 1e; detailed derivation is available in Note S1).

Although a theoretical solution is difficult to derive and would not directly provide geometrical information, one potential approach involves implementing springs with deformation-dependent stiffness. This can be achieved by having K1 exhibit softening behavior and K2 exhibit hardening behavior. Finite element analysis (FEA) simulations (Fig.S1) revealed that softening behavior is observed in a pair of double-clamped inclined beams when subjected to downward forces, as their in-plane stiffness becomes less aligned with the direction of deformation. In contrast, a pair of double-clamped straight beams exhibits stiffening behavior under deformation due to its in-plane stiffness aligning more effectively with the applied force. This insight suggests that integrating inclined and straight beams can form the basis of the metastructure design (Fig. 1f)35,36.

Geometric parameters of the metastructure

Two metastructure configurations, incorporating flat and inclined beams, were designed: single-sided inclined beams (SS, Fig. 2a) and double-sided inclined beams (DS, Fig. 2b). These designs leverage geometric nonlinearity to address the nonlinear relationship between voltage and displacement in ETAs. The maximum achievable displacement of each metastructure is limited by the ETA output, which is constrained by the applied voltage and the maximum temperature that silicon-based MEMS can withstand. Five geometric parameters (l1, l2, w1, w2, h1), illustrated in Figs. 2a and 2b, define the stiffness characteristics of each configuration: in-plane lengths (l1 and l2), in-plane widths (w1 and w2), and the rise of the beam (h1).

a Schematic of the SS metastructure with five geometric parameters defined. The SS configuration consists of a set of softening (inclined) beams and a set of constrained (flat) beams. The side connections are linked by a rigid crossbeam. b Schematic of the DS metastructure with five geometric parameters illustrated. The DS configuration consists of two sets of symmetrical softening (inclined) beams and a set of constrained (flat) beams. The side connections are linked by pairs of symmetrical inclined beams. c Output displacement profiles under tensile loading for i SS microscale, ii SS nanoscale, iii DS microscale, and iv DS nanoscale configurations, showing the influence of w1. Initial w1 dimensions are indicated in red (6 µm for microscale, 0.2 µm for nanoscale). d Output displacement profiles under tensile loading for geometric parameter w2 with the same order as c. Initial w2 dimensions are 6 µm for microscale and 0.2 µm for nanoscale. e Output displacement profiles under tensile loading for geometric parameter softening spring beam length l1 with the same order as c. Initial l1 dimensions are 500 µm for microscale and 120 µm for nanoscale. f Output displacement profiles under tensile loading for geometric parameter l2 with the same order as c. Initial l2 dimensions are 500 µm for microscale and 120 µm for nanoscale. g Output displacement profiles under tensile loading for geometric parameter h1 with the same order as c. Initial h1 dimensions are 10 µm for microscale and 2.5 µm for nanoscale

A parametric study assessed the influence of each geometric parameter on the mechanical behavior of the metastructures using beam model FEA (Fig. S2). This analysis considered fabrication limitations, leading to the definition of two design spaces: nanoscale and microscale. These classifications are based on the in-plane widths (w1 and w2) and reflect the trade-off between linearization potential and ease of fabrication. On the one hand, nanoscale metastructures, characterized by in-plane widths (w1 and w2) ranging from 0.1 to 1 µm, offer the potential for enhanced linearity due to their finer structures but require specialized nanofabrication facilities. On the other hand, microscale metastructures, with in-plane widths (w1 and w2) between 1 and 20 µm, can be readily produced using standard micro-fabrication facilities but exhibit a reduced degree of linearization.

The nonlinear behavior of the metastructure is influenced by the slenderness ratio of its component beams (Fig. S3). Higher slenderness ratios lead to increased nonlinearity under the same displacement37. Therefore, metastructures were designed with varying lengths and slenderness ratios within each size classification. Microscale metastructures had l1 and l2 from 200 to 1000 µm and slenderness ratios from 10 to 1000. Nanoscale metastructures had l1 and l2 from 40 to 200 µm and higher slenderness ratios from 40 to 2000.

Figure 2c–g illustrate the displacement response of the SS and DS designs for varying geometric parameters. The figure presents results for microscale SS (column 1), nanoscale SS (column 2), microscale DS (column 3), and nanoscale DS (column 4) configurations. To determine the influence of each geometric parameter on achieving a square root relationship between input and output displacement (uT = A√ua, where A is a constant), each parameter was systematically varied while others remained constant. The coefficient of determination (R²) for each fitted curve quantifies the agreement between simulation results and this ideal square root function. For the microscale configurations, beam widths (w1 and w2) ranged from 2 to 10 µm, beam lengths (l1 and l2) from 100 to 900 µm, and inclined beam rise (h1) from 2 to 10 µm. For the nanoscale configurations, the corresponding ranges were 0.1 to 0.5 µm for widths (w1 and w2), 40 to 200 µm for length (l1 and l2), and 0.5 to 2.5 µm for rise (h1).

The study of nanoscale metastructures revealed a critical instability in the SS configuration. All parametric studies of this design showed snap-back instability, characterized by abrupt reductions in both input and output displacement with increasing internal stress. This instability can be attributed to the fixed spacing between the side connections in the SS design. This fixed spacing facilitates greater in-plane deformation of the inclined beams, leading to an increase in buckling stress and a corresponding increase in incremental negative stiffness. In contrast, the symmetrical configuration of inclined beams in the DS design allows for lateral movement of the side connections during deformation, mitigating buckling and structural instability. Given the brittle nature of silicon, this snap-back induced energy release poses a risk of fracture in fabricated devices36,38. Consequently, the nanoscale SS configuration is unsuitable for practical implementation and is excluded from further investigation.

The nanoscale DS design configuration (Fig. 2c(iv)-2g(iv)) exhibited the strongest square root relationship between input and output of all tested configurations. This is evidenced by the high average R² values calculated from each of the R² listed in the plots: R²w1 = 0.993, R²w2 = 0.942, R²l1 = 0.979, R²l2 = 0.976, R²h1 = 0.995 for each geometric parameter. These results suggest the nanoscale DS configuration is optimal due to its strong adherence to the square root relationship. The relationship is particularly sensitive to variations in w2. A change in w2 from 0.1 µm to 0.5 µm resulted in a drop in R² from 0.991 to 0.866. In contrast, increasing l1 by the same order of magnitude produced only a marginal change of approximately 0.001 in R². This observation indicates that optimizing w2 towards a lower value is crucial for achieving the desired square root relationship.

In the microscale category, the differences in square root performance between the SS and DS configurations were less pronounced. This is likely due to the larger beam dimensions, which experience lower strain under the same input displacement compared to nanoscale designs. Although microscale structures exhibit greater absolute deformation, their increased dimensions result in reduced relative deformation (strain) for a given input displacement. This reduced deformation diminishes the square root relationship. While the difference in square root performance was minimal, several other factors distinguish the two designs. First, the SS design exhibits greater overall stiffness than the DS configuration, as it includes one fewer set of beams in series and features clamped side connections. This increased stiffness allows the SS design to generate greater force (Fig. S4–S6), making it more suitable for applications requiring high force output. Second, parametric studies (Fig. 2c(i)–2g(i) and Fig. 2c(iii)–2g(iii)) show that the SS configuration can achieve slightly higher displacement than the DS design, which could be advantageous for applications demanding significant displacement output. Finally, the SS configuration is less prone to fracture than the DS design. Because the SS design incorporates fewer inclined and constrained beams, it results in a more mechanically robust structure and a reduced risk of fracture. These advantages make the SS design a more promising candidate for the microscale category, provided its linearization behavior is comparable to the DS configuration. Nonetheless, this conclusion does not preclude further investigation of the DS design, as it may still perform well in achieving linearization.

Designing a metastructure to linearize the displacement-voltage relationship in MEMS ETAs presented a significant challenge due to the vast design space. The parametric study revealed that no single geometric parameter had a dominant influence; all parameters contributed to the linearization effect, except for the inclined beam rise (h1) in the DS design, which had a negligible impact. Therefore, traditional iterative design and simulation methods, while suitable for simpler structures, were insufficient for this complex task. The inherent nonlinearities and broad range of design variables required the use of an advanced optimization technique capable of systematically exploring and refining design configurations to achieve the desired linearization.

Optimization using a neural network

Machine learning offers a powerful approach for optimizing designs that are challenging to analyze with traditional methods39,40. By leveraging large datasets and advanced neural network algorithms, machine learning effectively captures nonlinear relationships and complex patterns in material properties and mechanical systems. In this study, a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) neural network was chosen to predict the nonlinear behavior of metastructure designs. MLPs are well-suited for this task due to their ability to model complex relationships between geometric parameters and mechanical responses. Their layered architecture and nonlinear activation functions enable them to overcome limitations of traditional analytical approaches41. Furthermore, MLPs offer a balance between computational efficiency and model complexity, making them suitable for exploring high-dimensional design spaces. The universal approximation property of MLPs ensures they can model any continuous function to a desired level of accuracy42, and they are straightforward to implement and train, providing an efficient solution for modeling intricate data patterns43,44.

The MLP surrogate model assists the optimization task by performing forward matrix multiplications in ∼0.01 s per design, in place of a full FEA solve (∼22 s per design). This allows rapid evaluation of thousands of candidate designs, whereas FEA is used only to generate the training data and to verify final optimized geometries. After training, the MLP model maintains good alignment with FEA results. Integrating the MLP model into the design workflow enabled rapid prediction of outcomes across the expansive design space. Unlike FEA, which typically requires solving systems of equations via inverse matrix calculations45, the MLP performs forward matrix operations during inference. These operations, consisting of simple matrix multiplications and nonlinear activations, eliminate the computational overhead of solving inverse problems. Consequently, the MLP reduces computational time, facilitating efficient optimization and enabling the inverse design of metastructures with desired nonlinear behaviors. This approach highlights the potential of machine learning to accelerate design processes and improve the feasibility of exploring complex, multidimensional design spaces.

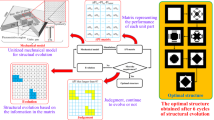

To optimize designs across the categorized size ranges (i.e., nanoscale DS and microscale SS and DS) while considering manufacturing constraints, we employed an MLP-based approach. Approximately 48,000 data points were generated and divided equally into three groups of 16,000 each. This division enabled a comprehensive investigation into size-dependent behaviors. Each design incorporated all geometric parameters into a beam model (Fig. 3a), which was then used in an FEA model to generate simulation outputs. For instance, Fig. 3b shows the output distribution of the beam model for the nanoscale DS design. In these simulations, the five key geometrical parameters (t₁, t₂, w₁, w₂, and h₁) were systematically varied over their predefined ranges, while all other factors, including material properties and boundary conditions, were held constant. This ensures that any variation in the output displacement is exclusively due to changes in the design parameters. The resulting distribution in Fig. 3c reflects the intrinsic response of the DS nanoscale metastructure design across the explored design space, with a particularly dense sampling in the 0.1-2 µm range. This density is critical for capturing the softening behavior necessary to correct the nonlinear voltage-displacement relationship of the actuator. By exploring an extensive geometric parameter space with evenly spaced parametric sweeps, we generated data points covering the entire range up to this 5 μm maximum. Output displacements for each group of 16,000 designs were sampled at 20 intervals, ensuring sufficient representation across the design space for detailed analysis and optimization.

a Procedure for generating training data for the ML model: key geometric parameters (w1, w2, l1, l2, h1) of the metastructure are the inputs of the workflow. FEA simulations are performed across a range of these parameters, generating a comprehensive dataset of output displacements for each design that forms the basis for training the neural network. b The distribution of output displacements presents the diverse range of responses captured within the dataset. c The architecture of the MLP neural network model, designed to predict the deformation behavior of the metastructure based on input variables. d The high accuracy of the MLP neural network in predicting deformation, as evidenced by near-perfect R2 values achieved during the training and validation phases across various design configurations. e The algorithm is employed to optimize metastructure designs for specified output characteristics by integrating the MLP model with a defined objective function. f The alternative algorithm employed to optimize metastructure designs for output characteristics by integrating the PSO in conjunction with FEA simulations. g The alternative algorithm employed to optimize metastructure designs for output characteristics by integrating the PSO in conjunction with NN

Subsequently, an MLP architecture (Fig. 3c) was developed to use the geometric parameters as input features and predict the tip displacement at 20 evenly spaced intervals in the input displacement domain. To standardize the neural network (NN) training process, all simulations were conducted with a fixed input displacement range of 0 to 5 µm, sampled at 0.25 µm increments (resulting in 20 evenly spaced input intervals). This approach ensures that the output displacement profiles of all metastructure designs are directly comparable. The NN was trained with geometrical parameters as input and the corresponding output displacement profile as output, eliminating the need for an explicit input displacement value during inference. Separate MLP models were trained for each size range. After training, these models demonstrated high accuracy, with an R2 = 0.996 achieved for the nanoscale DS configuration as an example (Fig. 3d). For detailed information regarding the MLP architecture, please refer to Table S1 and Fig. S7–S9.

Optimization for ideal metastructure

To optimize the metastructure geometric parameters for achieving a desired deformation behavior, the trained MLP was coupled with an objective function representing the target actuator output displacement profile \({{\boldsymbol{y}}}^{{\boldsymbol{* }}}=[{y}_{1}^{* },{y}_{2}^{* },{\boldsymbol{\ldots }}{y}_{20}^{* }]\).

The optimization process aims to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) between the MLP predicted displacements \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) and the target displacements \({y}_{i}^{* }\):

where \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) denotes the MLP predicted displacement at the i-th point, and \({y}_{i}^{* }\) is the target displacement. The algorithm updates the geometric parameters by calculating the gradients of the MSE and applying a gradient descent method46:

where θ represents the vector of geometric parameters, and α is the learning rate. The optimization process iteratively adjusts the geometric parameters until the predicted displacements match the desired specifications. This results in an optimized set of parameters. Figure 3f illustrates the framework for iteratively computing errors and updating the geometric parameters. This optimization strategy streamlines the design process by minimizing manual experimentation and directly guiding the geometric parameters toward optimal solutions. This approach also allows extensive exploration of the design space, ensuring thorough coverage with numerous starting points. Here, the optimization that runs for fabrication is performed with fabrication-based bounds on θ, enforcing a minimum beam width and maximum beam length dictated by the Piezo Multi-User MEMS Process (PiezoMUMP).

We additionally employed a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm to optimize the 5-parameter error function describing the discrepancy between the desired and actual metastructure output (Fig. 3f and Fig. 3g). In our implementation, PSO was used in conjunction with both FEA and a NN surrogate model. The PSO algorithm utilized 20 particles and was run for 100 iterations, with an inertia weight of 0.9 and cognitive and social coefficients of 2.0 each47. When integrated with FEA, each simulation took approximately 22 s; conversely, using the NN surrogate reduced the evaluation time to about 0.01 s per iteration. Although individual FEA runs can be parallelized, our PSO + FEA implementation launched each particle FEA simulation sequentially. In contrast, when generating data for the NN, we organized the simulations into batches and ran each batch on a separate CPU core in parallel. The optimized parameters obtained from PSO were comparable to those from the NN-based gradient descent approach. For details of implementation and results, please see Note S2 and Table S2.

Computational and experimental results

The optimized geometric parameters for each case (nanoscale/microscale DS and microscale SS), derived from the MLP models, were used to construct metastructures for ETA linearization. The effectiveness of the proposed metastructure is inherently dependent on specific displacement and force ranges. In this study, the metastructure was optimized for the electrothermal actuator with a functional displacement range of 1 µm. Since a single metastructure design cannot accommodate all actuation scenarios, multiple metastructure designs are required for different displacement and force conditions. To explore broader applicability, we systematically designed and analyzed multiple metastructure variations, each tailored to achieve specific displacement outputs based on a 4 µm displacement input from the electrothermal actuator (Table S3). These MLP-predicted results provided an initial baseline for manual refinement of the final geometric parameters, using 3D element modeling. This refinement was crucial for achieving higher fidelity in the final designs. As an application case study, an additional design requirement was imposed to adapt the ETA for tensile testing of 2D materials. We assumed a symmetrical configuration with a pair of ETAs positioned 2 µm apart. Each ETA needed to achieve a minimum displacement of 500 nm, with a focus on maximizing displacement control resolution. A total displacement of 1 µm would correspond to a 100% strain applied to the tested 2D material, sufficient to fracture all identified 2D materials.

Figures 4a to 4f illustrate these designs and their corresponding displacement profiles. As shown in Fig. 4a, the ETA without metastructure integration exhibits a standard nonlinear relationship between input voltage and output displacement. To quantify this nonlinearity, the second-order term (C2) of a fitted quadratic polynomial regression curve uT = C2V2 + C1V + C0 was used to represent the relationship between displacement (uT) and applied voltage (V). Smaller C2 values indicate a less nonlinear profile, as the quadratic relationship approaches linearity when C2 approaches zero. Additionally, a smaller C2 implies slower displacement growth with increasing voltage, enhancing movement resolution in response to small voltage increments.

a The configuration of the ETA in the 3D model without metastructures and its corresponding displacement versus voltage profile, derived from FEA simulations. b–d Configurations of ETA integrated with different metastructures and their input-output behaviors from 3D FEA simulation: b nanoscale DS, c microscale DS, and d microscale SS. The corresponding displacement versus voltage profile is based on FEA. The dashed black line is to help with the visualization of the beams, as the original beams are too narrow to be observed. e The configuration of the selected microscale SS metastructure, designed with fabrication constraints imposed by the MUMPs process, along with its displacement versus voltage profile derived from FEA simulations. f The configuration of the selected microscale SS metastructure, adding parallel beams to increase total output actuation force for future applications, together with the corresponding displacement versus voltage profile, derived from FEA simulations

Figure 4b–d illustrate the performance of three metastructures integrated with the ETA, optimized using the proposed procedure. The results demonstrate a consistent improvement in linearization across all configurations, with slight variations: C2 values of 0.014, 0.018, and 0.016 for the nanoscale DS, microscale DS, and microscale SS configurations, respectively. These values are significantly smaller than the C2 value of 0.099 observed in the original thermal actuator, indicating a notable but expected reduction in nonlinearity. While the nanoscale DS design would be ideal for demonstration purposes, the microscale SS design has been selected for actual fabrication due to several considerations: i) the delicate nature of nanostructures would make transferring 2D materials onto the device highly challenging; ii) the microscale SS design exhibits a smaller C2 value compared to the DS design, indicating better linearization performance; iii) the microscale SS design poses the least manufacturing challenges, ensuring greater flexibility during fabrication.

To allow mass production and practical application of the design, additional design considerations need to be incorporated. Figure 4e represents a microscale SS design optimized for MUMPs, specifically PiezoMUMPs, which has a minimum feature size of 14 µm for the purpose of this design. This results in a C2 value of 0.030, indicating a reduction in linearity regulation due to increased dimensions. Figure 4f presents the final design used for fabrication. This design, an augmentation of Fig. 4e, multiplies functional beams to enhance force output while minimizing displacement reduction. While the device was initially designed to test monolayer graphene, its design allows for the investigation of multilayer 2D materials, expanding the scope of applicability of the device. This force-enhanced modification should increase the output force without a significant trade-off in the output displacement48. The FEA simulation results show a 406.4% increase in force output and a 24.7% decrease in displacement based on FEA simulation (Fig. S10). The C2 value for this configuration is 0.023, representing a 76.77% improvement compared to the original ETA.

Importantly, all metastructure designs shown in Fig. 4, including those ultimately chosen for fabrication, were obtained through our optimization algorithm in conjunction with the MLP model. To ensure manufacturability, realistic fabrication constraints were explicitly incorporated into the optimization process by bounding the design parameter ranges. This enabled the algorithm to search for optimal solutions within the feasible design space. Therefore, the final fabricated design is not a compromise or manual fallback, but a direct result of constrained optimization that balances performance and practicality.

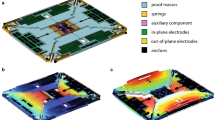

Displacement characterization in situ scanning electron microscope

Figure 5a presents an SEM image of the fabricated MEMS device with two symmetrically placed metastructure-empowered ETAs using the PiezoMUMPs process (Note S3). The center shuttles of two ETAs were designed to be connected to avoid out-of-plane imbalance and post-cut using focused ion beam (FIB) with a gap of 2 µm. The red boxed region in Fig. 5a highlights a magnified view of the gap (Fig. 5b) for potential suspension of 2D material samples. An isometric view is provided in the inset. This image was captured with no external voltage applied to the actuators. The design parameters of the fabricated device are listed in Table S4.

a SEM image of the overall layout, showing the thermal actuator, the integrated metastructure, and the electrodes. b Zoomed in view of the specimen loading area at 0 V, boxed by the red region in a. The inset is the isotropic view. The gap is milled by FIB. c SEM images showing the evolution in gap distance change at varied applied voltage from 0 V to 7 V. d The displacement versus voltage profiles for three cases: the FEA of the ETA without a metastructure (black), the FEA of ETA with finalized-metastructure design (red), and the fabricated device (blue). Errors of ±3 pixels were applied when measuring gap distance in the fabricated devices and included in the plot, but they are too small to be observed at this scale

Figure 5c shows the changes in gap distance at various voltage levels, ranging from 0 V to 7 V in 1 V increments. The displacement versus voltage profiles for the fabricated device (half-gap measurement), the FEA results for the ETA without a metastructure, and the FEA results for the ETA with the finalized metastructure are shown in Fig. 5d. Repeated calibrations were performed on three different fabricated devices (Fig. S11), all of which demonstrated consistent behavior. The performance of the fabricated device shows excellent agreement with the simulations, achieving a C2 = 0.015, which represents an approximately 85% improvement in linearity compared to the ETA without a metastructure (C2 = 0.099). The increased discrepancy between FEA predictions and experimental displacement at higher voltages (Fig. 5d) is largely due to the visual of plot scaling; the relative percentage error remains consistent across the range. Additional factors such as parasitic resistances (e.g., wire bond/contact resistance), non-ideal thermal boundary conditions (e.g., radiative heat loss), and fabrication-induced variations (e.g., beam thickness, residual stress) further contribute to deviations at high input levels. Importantly, the linearity metric (C2 = 0.015) is derived from experimental data, confirming that the metastructure maintains its linearization performance despite deviations in absolute displacement.

Discussion

This study provides a sensor-free and easy-to-implement approach to addressing the inherent nonlinearity in MEMS electrothermal actuators, advancing their applicability in broader contexts. By integrating mechanical metastructures optimized via machine learning, this work marks a significant departure from traditional sensor-based feedback systems. The proposed metastructures, designed to modulate stiffness and geometric nonlinearity, effectively linearized the voltage-displacement response, streamlining the actuation process and reducing system complexity. The results are closely aligned with simulation predictions, and while complete linearity was not achieved in the fabricated devices, they demonstrate significant improvements in linearization ( ~ 85%), making it suitable for applications such as characterizing the mechanical properties of 2D materials. The study highlights the potential of leveraging machine learning in inverse design problems, offering a scalable and computationally efficient approach to optimizing complex mechanical systems.

Alternative surrogate modeling techniques, such as Gaussian Process Regression, Polynomial Chaos Expansions, Radial Basis Function surrogates, and Support Vector Regression, are available for creating differentiable approximations of finite element models. In our study, however, the MLP neural network provided a balance of accuracy and computational efficiency for capturing the complex nonlinear behavior of the metastructures49,50. The NN surrogate achieved inference times of approximately 0.01 s per evaluation (compared to roughly 22 s per full FEA simulation), and it enabled efficient gradient-based optimization across the entire design parameter space.

A reduction in displacement compared to the original electrothermal actuator is expected due to the transformation of the “hockey-stick” voltage-displacement curve into a linear profile. This is not a limitation of the design but rather an inherent trade-off associated with linearization. Importantly, the actuator is not restricted to small-displacement applications. When larger displacements are required, the designer can simply adapt the ETA configuration accordingly to meet the specific displacement needs, ensuring the versatility of this approach. Broader applicability can also be achieved by developing multiple device variants tailored to different material classes.

Nevertheless, the addition of metastructures introduces greater fabrication complexity and potential structural weaknesses, which may impact the robustness of the system. Addressing these aspects presents opportunities for future works. Optimizing metastructure designs to balance linearity, displacement output, and structural integrity could further enhance performance. Exploring alternative materials or advanced microfabrication techniques may reduce these challenges and improve scalability.

The impact of this work extends beyond MEMS electrothermal actuators. The proposed methodology could be adapted to other nonlinear actuation systems or applied to macro-scale devices where linearity is critical. The integration of machine learning into mechanical design processes paves the way for future intelligent, adaptive systems capable of self-optimization in response to dynamic requirements. These advancements align with the increasing demand for efficient, high-performance components in robotics, biomedical devices, and precision engineering. By combining mechanical metastructures with machine learning optimization, this study establishes a foundation for future innovations in both micro- and macro-scale actuation technologies.

Materials and methods

ETA design

The selected electrothermal actuation mechanism employs a chevron-type (V-shape) configuration, chosen to meet the focus of the study on characterizing in-plane deformation of 2D materials. Figure 4a illustrates the ETA. It consists of five pairs of inclined actuation beams and four pairs of perpendicular heat-sink beams. Each actuation beam measures 450 µm in length, 25 µm in width, and 10 µm in depth, where the 10 µm depth corresponds to the thickness of the structural layer. The heat-sink beams are 200 µm long, 8 µm wide, and 10 µm deep.

To prevent out-of-plane misalignment during fabrication, the two actuation shuttles are initially connected across the gap. A focused ion beam (FIB) is then used to cut the gap for release. When a voltage is applied, the actuators move in opposite directions, and their displacements are experimentally calibrated. The SEM imaging (Hitachi S-3400N) is performed in-situ using a Deben vacuum electrical feedthrough port connected to a BK Precision 9110 DC power supply. Before SEM loading, the device is bonded to a printed circuit board (PCB) containing the electrical circuitry using a WestBond 747677E wire bonder. A detailed description of the experimental setup is provided in Fig. S12. Gap measurements are obtained using the Fiji image processing tool.

Simulation conditions

Simulations of meta-structures and the generation of data for the neural network are performed using the nonlinear arc-length solver in ANSYS 2023R2 Workbench and Mechanical with 2D beam elements. The results and the boundary conditions in mesh sensitivity and slenderness sensitivity of beam elements, and meta-structure analysis are illustrated in Fig. S2 and Fig. S3. The material properties used in FEA are listed in Table S5. 3D FEAs were conducted with Ansys 2023R2 Workbench and Mechanical (Fig. S13). For ETA, the mesh shows its convergence at 3 µm (Fig. S14), which is a balanced size for simulation accuracy and computational cost. The actuation voltages are applied across two electrodes, ranging from 0 to 7 V at an increment of 0.5 V. Thermal boundary conditions are set at room temperature (22 °C) at the anchors of both actuation and heat-sink beams. Mechanical constraints are applied as fixed support at all these anchors.

Thermal stabilization and displacement measurement protocol

To ensure accurate and repeatable displacement characterization, voltage was applied incrementally in 1 V steps from 0 V to 7 V using a precision DC power supply. At each step, the device was held at the target voltage for approximately 60 s prior to imaging, allowing the system to reach thermal equilibrium. Displacement measurements were obtained via SEM imaging only after thermal drift became negligible, as confirmed by monitoring consecutive image frames. All measurements were conducted under identical environmental conditions and followed the same timing protocol, minimizing the influence of thermal lag or transient effects on the observed displacement. This controlled procedure ensured the consistency and reliability of the acquired data for linearity evaluation.

Displacement measurement and resolution

Displacement-voltage characterization was performed using in-situ SEM (Hitachi S-3400N) combined with image-based analysis in ImageJ. Displacement was extracted by tracking the shuttle gap across applied voltages. At the selected magnification, the imaging resolution was approximately 151 pixels per micron (6.6 nm/pixel). Measurement uncertainty, primarily due to manual point selection and image contrast, was estimated at ±3 pixels ( ± 19.8 nm). Given the 0–1 μm displacement range, this corresponds to a relative uncertainty below 3%, sufficient for assessing linearity. Although SEM lacks real-time tracking capabilities, it offers high spatial resolution and visual confirmation of quasi-static displacement, making it well-suited for the present study.

Data availability

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request. Codes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sharma, K. & Srinivas, G. Flying smart: Smart materials used in aviation industry. in Materials Today: Proceedings vol. 27 244–250 (Elsevier Ltd, 2020).

Li, D. et al. Miniaturization of mechanical actuators in skin-integrated electronics for haptic interfaces. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 85 (2021).

Yu, Y. et al. Fiber-Shaped Soft Actuators: Fabrication, Actuation Mechanism and Application. Adv. Fiber Mater. 5, 868–896 (2023).

Minchala, L. I., Astudillo-Salinas, F., Palacio-Baus, K. & Vazquez-Rodas, A. Mechatronic Design of a Lower Limb Exoskeleton. in Design, Control and Applications of Mechatronic Systems in Engineering (2017). https://doi.org/10.5772/67460.

Li, J. et al. Development of a Novel Parasitic-Type Piezoelectric Actuator. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 22, 541–550 (2017).

Xie, Q., Zhang, Y., Wang, T. & Zhu, S. Dynamic response prediction of hydraulic soft robotic arms based on LSTM neural network. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I: J. Syst. Control Eng. 237, 1251–1265 (2023).

Kiuchi, M., Okimoto, N., Hirata, Y., Matsuoka, G. & Torayashiki, O. Out-Of-Plane Direction Thermal Actuater for Optical Mems. in 2019 20th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems & Eurosensors XXXIII (TRANSDUCERS & EUROSENSORS XXXIII). (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/TRANSDUCERS.2019.8808817.

Chakraborty, S., Kumar, D. & Thakura, P. R. Modeling of a high-performance three-phase voltage-source boost inverter with the implementation of closed-loop control. in Renewable Energy Systems: Modelling, Optimization and Control (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820004-9.00012-7.

Judy, J. Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS): fabrication, design and applications. Smart Mater. Struct. 10, 1115 (2001).

Van Spengen, W. M. MEMS reliability from a failure mechanisms perspective. Microelectron. Reliab. 43, 1049–1060 (2003).

Qi, Y. et al. Stiffness adjustable optical MEMS accelerometer. in SPIE/COS Photonics Asia 2020: Adv. Sensor Sys. Applications X. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2573644.

Qaiser, N. et al. A thermal microfluidic actuator based on a novel microheater. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 33, 035001 (2023).

Atik, A. C., Özkan, M. D., Özgür, E., Külah, H. & Yildirim, E. Modeling and fabrication of electrostatically actuated diaphragms for on-chip valving of MEMS-compatible microfluidic systems. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 30, (2020).

Cao, C., Howe, J. Y., Perovic, D., Filleter, T. & Sun, Y. In situ TEM tensile testing of carbon-linked graphene oxide nanosheets using a MEMS device. Nanotechnology 27, 28LT01 (2016).

Cao, C. et al. Strengthening in Graphene Oxide Nanosheets: Bridging the Gap between Interplanar and Intraplanar Fracture. Nano Lett. 15, 6528–6534 (2015).

Morrison, J., Imboden, M., Little, T. D. C. & Bishop, D. J. Electrothermally actuated tip-tilt-piston micromirror with integrated varifocal capability. Opt. Express 23, 9555 (2015).

Hamedi, M., Vismeh, M. & Salimi, P. A New MEMS assembly unit for hybrid self micropositioning and forced microclamping of submilimeter parts. Adv. Mat. Res 154–155, 1705–1712 (2010).

Zhao, L. F., Zhou, Z. F., Meng, M. Z., Li, M. J. & Huang, Q. A. An efficient electro-thermo-mechanical model for the analysis of V-shaped thermal actuator connected with driven structures. Int. J. Numer. Model.: Electron. Netw. Devices Fields 34, e2843 (2021).

Khan, F., Hussein, H. & Younis, M. I. Spring-Shaped Inductor Tuned with a Microelectromechanical Electrothermal Actuator. IEEE Magn. Lett. 11, 1–5 (2020).

Toraya, A. & Gaber, N. Novel thermal actuator employing the mechanical multiplication theory for achieving large stroke. in 2019 31st International Conference on Microelectronics (ICM). vols 2019-December (2019).

Shuaibu, A. H., Nabki, F. & Blaquiere, Y. A MEMS Electrothermal Actuator Designed for a DC Switch Aimed at Power Switching Applications and High Voltage Resilience. in 20th IEEE Interregional NEWCAS Conference (NEWCAS). (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/NEWCAS52662.2022.9842102.

Zou, Y., Jun Wang, J., Xu, P., Peng, C. & Lou, K. Miniature adjustable-focus camera module integrated with MEMS-tunable lenses for underwater applications. in Applied Optics and Photonics China 2019: Optical Sensing and Imaging Technology. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2544048.

Kim, S., Kim, K. S. & Kim, Y. Analytical modeling of Ni–Co based multilayer bimorph actuators involving dual insulation layers. Sens Actuators A Phys. 348, 113984 (2022).

Chae, U., Yu, H. Y., Lee, C. & Cho, I. J. A hybrid RF MEMS switch actuated by the combination of bidirectional thermal actuations and electrostatic holding. IEEE Trans. Micro. Theory Tech. 68, 3461–3470 (2020).

Khudiyev, T. et al. Electrostrictive microelectromechanical fibres and textiles. Nat. Commun. 8, 1435 (2017).

Ni, L., Pocratsky, R. M. & de Boer, M. P. Demonstration of tantalum as a structural material for MEMS thermal actuators. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 6 (2021).

Ouyang, J. & Zhu, Y. Z-shaped MEMS thermal actuators: Piezoresistive self-sensing and preliminary results for feedback control. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 21, 596–604 (2012).

Shu, L., Guo, L., Wu, G. C. & Chen, W. Research of thermal protection characteristics for circuit breakers considering nonlinear electro-thermal-structural coupling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 153, 85–94 (2019).

Xiang, X. et al. A customized nonlinear micro-flexure for extending the stable travel range of MEMS electrostatic actuator. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 28, 199–208 (2019).

Messenger, R. K., Aten, Q. T., McLain, T. W. & Howell, L. L. Piezoresistive feedback control of a mems thermal actuator. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 18, 1267–1278 (2009).

Thuau, D., Ayela, C., Poulin, P. & Dufour, I. Highly piezoresistive hybrid MEMS sensors. Sens Actuators A Phys. 209, 161–168 (2014).

Benmessaoud, M. & Nasreddine, M. M. Optimization of MEMS capacitive accelerometer. Microsyst. Technol. 19, 713–720 (2013)

Tsai, T. H., Tsai, H. C. & Wu, T. K. A CMOS micromachined capacitive tactile sensor with integrated readout circuits and compensation of process variations. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 8, 608–616 (2014).

Khoei, A. R. & Kianezhad, M. A machine learning-based atomistic-continuum multiscale technique for modeling the mechanical behavior of Ni3Al. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 239, 107858 (2023).

Shahryari, B. et al. Programmable Shape-Preserving Soft Robotics Arm via Multimodal Multistability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2407651 (2024).

Mofatteh, H. et al. Programming Multistable Metamaterials to Discover Latent Functionalities. Adv. Sci. 9, e2202883 (2022).

Mehreganian, N., Fallah, A. S. & Sareh, P. Impact response of negative stiffness curved-beam-architected metastructures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 279, 112389 (2023).

Seyedkanani, A. & Akbarzadeh, A. Magnetically assisted rotationally multistable metamaterials for tunable energy trapping–dissipation. Adv. Funct. Mater 32, 2207581 (2022).

Herrmann, L. & Kollmannsberger, S. Deep learning in computational mechanics: a review. Comput Mech. 74, 281–331 (2024).

Deng, B. et al. Inverse Design of Mechanical Metamaterials with Target Nonlinear Response via a Neural Accelerated Evolution Strategy. Adv. Mater. 34, 2206238 (2022).

Haykin, S. Multilayer Perceptrons. in Neural networks: a comprehensive foundation vol. 13 (Pearson Education, 1999).

Hornik, K., Stinchcombe, M. & White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Networks 2, 359–366 (1989).

Badarinath, P. V., Chierichetti, M. & Kakhki, F. D. A machine learning approach as a surrogate for a finite element analysis: Status of research and application to one dimensional systems. Sensors 21, 1–18 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Mechanical properties prediction of composite laminate with FEA and machine learning coupled method. Compos Struct. 299, 116086 (2022).

Bengio, Y. Learning Deep Architectures for AI. (Now Foundations and Trends, Montreal, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1561/2200000006.

Andrychowicz, M. et al. Learning to learn by gradient descent by gradient descent. in 30th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2016). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1606.04474.

Nayak, J., Swapnarekha, H., Naik, B., Dhiman, G. & Vimal, S. 25 Years of Particle Swarm Optimization: Flourishing Voyage of Two Decades. Arch. Comput.Methods Eng. 30, 1663–1725 (2023).

Espinosa, H. D., Zhu, Y. & Moldovan, N. Design and operation of a MEMS-based material testing system for nanomechanical characterization. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 16, 1219–1231 (2007).

Wang, Y., Wang, J., Zhang, H. & Song, J. Bridging prediction and decision: Advances and challenges in data-driven optimization. Nexus 2, 100057 (2025).

Samadian, D., Muhit, I. B. & Dawood, N. Application of Data-Driven Surrogate Models in Structural Engineering: A Literature Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 32, 735–784 (2024).

Acknowledgements

C.C., L.Z., and Y.S. would like to acknowledge the funding support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Idea to Innovation program, McGill Innovation Fund, McGill TechAccelR program, Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI) JELF program, and NSERC Discovery Program. A.H.A. acknowledges the financial support by the Canada Research Chairs program in Programmable Multifunctional Metamaterials and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada through NSERC Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2022-04493). H.M. is supported by Quebec Research Fund - Nature and technologies (FRQNT) doctoral awards (B2X). During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT and Gemini to check grammar and spelling errors. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and C.C.; Methodology, L.Z. and H.M.; Software, H.M.; Validation, L.Z. and H.M.; Investigation, L.Z., H.M., and J.K.; Resources, C.C., A.A., J.H., S.D., and Y.S.; Writing – Original Draft, L.Z. and H.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, C.C., A.A., and Y.S.; Visualization, L.Z.; Supervision, C.C., A.A., and Y.S.; Funding Acquisition, C.C.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Mofatteh, H., Kong, J. et al. Machine learning-driven metastructure design for sensor-free linearization of MEMS electrothermal actuators. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 214 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01065-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01065-4