Abstract

Background

Body mass index (BMI) is strongly associated with the development of type 2 diabetes. However, the association between long-term time in target range (TTR) for BMI and the incidence of new-onset diabetes remains unclear.

Methods and results

This study utilized a non-diabetic population aged 45 years or older from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). BMI-TTR was assessed in Waves 1, 2, and 3 over a 5-year period, with the target range defined as 18.5 kg/m² ≤ BMI < 23 kg/m². New-onset diabetes in Waves 2, 3, and 4 over a 6-year follow-up served as the study endpoint. After applying exclusion criteria, 6662 participants (3143 men and 3519 women; mean age 58.93 ± 8.85 years) were enrolled. Participants were categorized into four groups (TTR1–TTR4) based on the number of times BMI was within the target range (0–3 times). The risk of new-onset diabetes decreased progressively with increasing BMI-TTR during follow-up. Compared with the TTR1 group, participants in the TTR4 group exhibited a significantly lower risk of diabetes (adjusted HR: 0.577, 95% CI: 0.463–0.720, P < 0.001), even after adjusting for baseline BMI (adjusted HR: 0.685, 95% CI: 0.537–0.872, P = 0.002). This effect was even more pronounced in female subgroup and in individuals aged under 60 years of age.

Conclusion

In adults aged 45 years or older, regardless of baseline BMI, maintaining BMI within the target range over time was associated with a reduced risk of new-onset diabetes, particularly among women and individuals under 60 years of age. These findings highlight the importance of long-term weight management in diabetes prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a major public health concern and a leading cause of mortality and disability worldwide. Studies have shown that body mass index (BMI) is a commonly used measure of obesity and that obese individuals (as measured by BMI) have a significantly higher risk of T2DM [1, 2]. This association is particularly pronounced among the elderly, especially those over 50 years of age [3].

Several studies have indicated that a normal BMI, not too low nor too high, is significantly associated with a reduced risk of T2DM, cardiovascular disease events, and death [4,5,6]. Time in target range (TTR) metrics, such as those for blood glucose and blood pressure, have been employed to predict complications and clinical outcomes in diabetes and hypertension [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Elevated BMI has also been independently associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality [13, 14]. However, the association between BMI-TTR and the risk of new-onset diabetes remains underexplored.

In this study, we utilized the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which initially recruited a middle-aged and older cohort aged 45 years and older and has followed them over time, to investigate the association between BMI-TTR and risk of the long-term risk of diabetes in a middle-aged and elderly population.

Participants and methods

Study design and participants

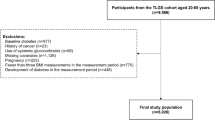

CHARLS is a longitudinal cohort study that collects high-quality microdata on households and individuals aged 45 years and older in China, and the study is ongoing. For a detailed description of CHARLS, please refer to the relevant literature and its official website [15, 16]. Participants included in this analysis had BMI measurements from CHARLS Wave 1 (2011), Wave 2 (2013), and Wave 3 (2015). Individuals under 45 years of age, those with diabetes mellitus (DM) at baseline, and those with a fasting blood glucose ≥7 mmol/L or glycated hemoglobin ≥6.5% at baseline were excluded. Ultimately, a total of 6662 participants were included in the BMI-TTR analysis (Flow Diagram was shown in Fig. 1). The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Peking University. The studies were in accordance with the STROBE Statement, and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Assessment of BMI and definition of BMI-TTR

BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²). The target range for BMI was defined as 18.5 kg/m² ≤ BMI < 23 kg/m², based on World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for Asian populations. Participants were stratified into four groups (TTR1–TTR4) based on the number of times their BMI fell within the target range (0–3 times). The TTR1–TTR4 categories are mutually exclusive. The TTR1 group consists of participants whose BMI was outside the normal range in all three Waves. The TTR2 group refers to participants whose BMI fell within the normal range in any one of the three Waves. The TTR3 group refers to participants whose BMI fell within the normal range in any two of the three Waves. The TTR4 group includes participants whose BMI remained within the normal range across all three Waves.

Incident diabetes

New-onset diabetes, defined as self-reported physician-diagnosed diabetes, was assessed in Waves 2 (2013), 3 (2015), and 4 (2018) over a 6-year period.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL) and R software (version 4.3.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria). Categorical variables were expressed as percentages, and continuous variables as means ± SD. Group comparisons were performed using Student t-tests, ANOVA, nonparametric tests, Chi-square tests, or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Cox regression models and binary logistic regression models were employed to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Kaplan–Meier curves illustrated the incidence of outcomes. Multivariate Cox models and binary logistic regression models adjusted for covariates including age, gender, hypertension, smoking, and other relevant factors.

The COX regression models included the following:

Model 1: Age, gender, hypertension, smoking, systolic blood pressure (SBP), heart rate (HR), hyperlipidemia, physical activity, marital status, education, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and BMI-TTR.

Model 2: Age, gender, hypertension, smoking, SBP, HR, hyperlipidemia, physical activity, marital status, education, HDL-C, hsCRP, HbA1c, eGFR, BMI-TTR, and BMI of waves 1.

Model 3: Age, sex, hypertension, smoking, SBP, HR, hyperlipidemia, physical activity, marital status, education, HDL-C, hsCRP, HbA1c, eGFR, BMI-TTR, and BMI from waves 1, 2, and 3. The covariates included in the models were selected based on the results of univariate analysis, previously identified risk factors for diabetes in the literature, and established risk factors recognized as associated with diabetes, including age >45 years, overweight, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and other features of metabolic syndrome, such as sex, pollution, chronic kidney disease (CKD, which affects HbA1c), obesity-related inflammation (CRP and IL-6) [17,18,19,20]. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was used to explore the nonlinear relationship between baseline BMI and diabetes incidence. Subgroup analyses were conducted by gender and age, with interaction effects assessed. Missing data were addressed using multiple imputation (see S-Table 1). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Basic characteristics

A total of 6662 participants (3143 men and 3519 women, aged 58.93 ± 8.85 years) from the CHARLS were included. The basic characteristics of the different groups are presented in Table 1. From TTR 1 to TTR 4, baseline BMI levels gradually decreased, as did blood pressure, HR, blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin levels, and the proportion of individuals with a history of hypertension. Conversely, age, the proportion of males, and the proportions of smokers and alcohol drinkers gradually increased.

Association between TTR and diabetes incidence

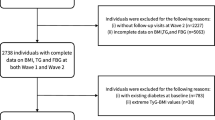

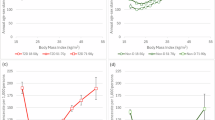

Table 1 shows the number and proportion of incident diabetes cases during the 6-year follow-up period. In total, 655 participants developed diabetes, resulting in a prevalence of 9.83%. The incidence rates across TTR groups were: TTR1, 413 (13.6%); TTR2, 73 (8.6%); TTR3, 58 (6.8%); and TTR4, 111 (5.8%) (p < 0.001 for trend). Compared to TTR1, TTR4 was associated with a significantly reduced risk of diabetes in both unadjusted (HR 0.414, 95% CI 0.335–0.51, p < 0.001) and adjusted: Model 1 (HR 0.577, 95% CI 0.463–0.720, p < 0.001), and Model 2 (HR 0.685, 95% CI 0.537–0.872, p = 0.002). Only when all BMIs of three Waves are included in the model will this significant effect of TTR disappear (Model 3). Baseline BMI was independently associated with diabetes risk (HR 1.037, 95% CI 1.017–1.057, p < 0.001) (Table 2). Binary logistic regression produced similar results (S-Table 2). Survival curves are presented in Fig. 2, with a log-rank p-value < 0.001. We developed an RCS model to examine the nonlinear relationship between baseline BMI and new-onset diabetes. The model revealed a significant nonlinear association (overall p < 0.0001, nonlinear p = 0.0003) (S-Fig. 1).

Additionally, we conducted an analysis comparing participants with persistently high TTR across all periods to those whose TTR improved over time (S-Tables 4 and 5). The total population was divided into three groups: the sustained normal BMI group (Group 1: normal BMI across all three waves, n = 1921), the BMI improvement group (Group 2: abnormal in wave 1 but normal in at least one of waves 2 or 3, n = 590), and the other group (Group 3, n = 4151). We found that both the BMI improvement group and the BMI consistently normal group exhibited lower long-term diabetes risk compared to the group with no improvement or persistently abnormal BMI. However, there was no significant difference in long-term diabetes risk between the BMI improvement group and the BMI consistently normal group.

Subgroup analysis

To further validate the association between TTR and the risk of new-onset diabetes, we repeated the regression analyses in gender and age subgroups. As shown in Table 3 and S-Table 3, the results regarding the association between new-onset diabetes and TTR were consistent with those observed in the whole population. However, the association was more pronounced in women and individuals aged 45–60 years. Interaction analyses were nonsignificant (p > 0.05).

Discussions

This study based on CHARLS data from 2011 to 2018, explores the association between middle-aged and older adults’ TTR and the risk of incident diabetes. A higher BMI-TTR was associated with a lower risk of diabetes, independent of baseline BMI, particularly among women and those aged 45–60 years. These findings highlight the importance of sustained BMI management within the target range to mitigate the risk of diabetes.

Obesity is well-known for its strong association with insulin resistance and the incidence of type 2 diabetes, with BMI being the classic measure of obesity. DM is a serious chronic condition that can lead to severe complications in multiple systems, including the heart, brain, kidneys, eyes, and nervous system. TTR has been widely used in studies examining the association between blood pressure or blood sugar and long-term outcomes. For example, higher SBP-TTR has been associated with a lower risk of adverse renal and cardiovascular events in hypertensive adults, and in older adults with hypertension, a higher long-term SBP-TTR correlates with a lower risk of cardiovascular events, regardless of their mean SBP [21,22,23]. TTR for blood glucose and the glycated hemoglobin has been shown to be significantly associated with adverse outcomes, such as complications and mortality, and is used as an important indicator for prognostic monitoring [7, 9, 10, 24, 25]. However, the association between long-term BMI attainment and the risk of developing diabetes remains unclear.

Although BMI is a relatively stable parameter in the short term (e.g., within hours or days), it can still exhibit meaningful changes over extended periods (e.g., months or years) [26, 27]. BMI-TTR is a valuable parameter for assessing the attainment of BMI over time. Our study is the first to examine the association between BMI-TTR and the long-term risk of diabetes. Our findings suggest a significant association between higher TTR and a lower risk of new-onset diabetes, even after controlling for baseline BMI levels. These results emphasize the importance of managing BMI not only to achieve the target range but also to maintain it as much as possible over a long follow-up period, in order to reduce the risk of developing diabetes and avoid a range of adverse clinical events associated with diabetes development.

In reference to the use of TTR in blood pressure and glucose monitoring, a higher TTR reflects lower variability in BMI and a greater chance of staying within the “healthy BMI” range over time. Previous studies have suggested that weight fluctuations may indicate underlying metabolic dysfunction, such as insulin resistance and inflammation [28,29,30]. Animal experiments have highlighted the significance of BMI variability: weight-cycling animals (those with fluctuating weight gain, loss, and recovery) exhibit similar adverse metabolic consequences as those with lifelong obesity, including higher levels of impaired fasting glucose and glucose intolerance [31]. It is hypothesized that neuroendocrine dysregulation of appetite and satiety hormones, as well as aseptic inflammation, may contribute to these effects [32, 33]. Furthermore, weight changes may promote increased lipogenic enzymes, such as myristic acid, palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid, and stearic acid, which can impair glucose metabolism and increase the risk of diabetes [34, 35]. These studies focused on BMI variability and did not address the percentage of BMI attainment, which is a key aspect of our study and its innovation.

Our findings were particularly robust in the female subgroup and among individuals aged 45–60 years. Changes in BMI are closely related to diet and exercise. It has been found that women are more likely to feel full than men, owing to gender-specific differences in hormones and neuronal activation [36]. There is also a gender-specific association between female estrogen and male hormone-sensitive lipase variants, as well as blood glucose concentrations, which may lead to different susceptibilities to metabolic diseases [37]. Males and females differ in body composition, with females generally having a higher body fat percentage and higher leptin levels. In addition, males have a marked preference for strength training, and high muscle mass in men facilitates glucose uptake and optimizes metabolic reactions [38, 39]. In summary, women may be more susceptible to changes in BMI. Regarding age, physical activity declines significantly with age, accompanied by a loss of muscle mass and a decrease in hormone levels, resulting in less pronounced benefits of maintaining BMI within the target range in older adults compared to younger ones [40].

BMI is a weight-related index, and since height remains relatively stable after adulthood, changes in BMI can effectively reflect changes in weight. With the increasing awareness of the dangers of obesity, many individuals strive to maintain a healthy weight. Additionally, beauty-conscious individuals often aim to control their weight to achieve an ideal body. Although our study focused on the impact of TTR on the development of diabetes, it did not examine the influence of weight loss, whether intentional or unintentional. Studies have shown that intentional weight loss can significantly reduce mortality, cancer risk, and cardiovascular disease risk, as well as increase remission rates in diabetic patients. However, unintentional weight loss, which differs metabolically from intentional weight loss, is often associated with chronic diseases, low muscle mass, and poor appetite, and tends to be associated with poor outcomes [41,42,43]. Unfortunately, this study only examined the number of times BMI was within the normal range. Although the statistical results are significant, the study did not explore the chronological order of BMI attainment or consider whether the weight loss was intentional or unintentional. Our conclusions provide evidence and motivation for individuals seeking to lose weight. Future studies with a prospective design are needed to explore the TTR-related effects whereas considering both intentional and unintentional weight loss.

Of course, there are some limitations in our study. First, the diagnosis of DM was based on self-reported physician-diagnosed information, which may introduce bias. Second, this study was conducted solely within a Chinese geriatric cohort, limiting the generalizability of the finding to other population. Third, the number of BMI measurements in our study was limited to three, which is significantly fewer than the numerous blood pressure measurements in the Blood Pressure TTR studies, and the method of TTR calculation was also different. Therefore, studies with more frequent and shorter intervals of BMI measurements and more precise TTR calculations are urgently needed to further validate our findings. Forth, the sample size in our study was relatively small, particularly in the TTR2 and TTR3 groups, which included only more than 800 individuals, and even fewer were available for subgroup analyses by gender and age. Fifth, the confounding effects of weight loss (whether intentional or unintentional) were not considered in the analysis of the association between TTR and diabetes onset. Sixth, although we controlled for confounding variables in the regression model, we were unable to entirely eliminate potential biases, such as survival bias and selection bias. Seventh, additional analysis comparing participants with sustained normal BMI across all periods to those whose BMI improved later showed no significant difference in DM incidence. Finally, whereas we have proposed potential mechanisms, they do not fully explain the findings, and further research is needed to explore these mechanisms more thoroughly.

Conclusions

Higher BMI-TTR was significantly associated with a reduced risk of long-term diabetes in non-diabetic middle-aged and older adults aged 45 and above, with the association being more pronounced in men and individuals under 60 years of age. Long-term monitoring and maintenance of body weight within the normal range can significantly reduce the risk of developing diabetes in the long term.

Data availability

Data supporting the results of this study are available from official websites tttp:// charls.pku.edu.cn and https://g2aging.org/.

References

Papotto PH, Yilmaz B, Silva-Santos B. Crosstalk between γδ T cells and the microbiota. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6:1110–7.

Boutari C, DeMarsilis A, Mantzoros CS. Obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;202:110773.

Li Y, Teng D, Shi X, Qin G, Qin Y, Quan H, et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American Diabetes Association: national cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369:m997.

Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Després JP, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e984–e1010.

Dwivedi AK, Dubey P, Cistola DP, Reddy SY. Association between obesity and cardiovascular outcomes: updated evidence from meta-analysis studies. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22:25.

Su HX, Chen ZS, Xu HW, Luo Y, Wang KP, Hu YH, et al. Relationship between obesity and death by multi-morbidity status in older adults in China]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2022;43:324–9.

Cai J, Liu J, Lu J, Ni J, Wang C, Chen L, et al. Impact of time in tight range on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27:2154–62.

Al-Dalakta A, Tabaja C, Motairek I, El Hajjar AH, Agarwal N, St John J, et al. Blood pressure time in target range and its impact on clinical outcomes. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2024;26:1145–51.

Lu J, Ma X, Zhou J, Zhang L, Mo Y, Ying L, et al. Association of time in range, as assessed by continuous glucose monitoring, with diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2370–76.

Xu, KeLi SY, Zhang Z, Liu CY, Guo QY, Lu B, et al. Association between time in range, a novel measurement of glycemic control and islet secretory function in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus-An observational study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;173:108684.

Wang H, Song J, Liu Z, Yu H, Wang K, Qin X, et al. Time in target range for blood pressure and adverse health outcomes: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2025;82:419–31.

Tian X, Zhang Y, Chen S, Xia X, Xu Q, Wang Y, et al. Blood pressure time in target range within 24h and cardiovascular diseases and mortality: perspectives from a real-world cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2025;100:657–67.

Mehran L, Honarvar M, Masoumi S, Khalili D, Azizi F, Blaha MJ, et al. The association of body mass index variability with cardiovascular disease and mortality: a mediation analysis of pooled cohorts. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15:1345781.

Massey RJ, Chen Y, Panova-Noeva M, Mattheus M, Siddiqui MK, Schloot NC, et al. BMI variability and cardiovascular outcomes within clinical trial and real-world environments in type 2 diabetes: an IMI2 SOPHIA study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:256.

Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61–8.

The official CHARLS: website http://charls.pku.edu.cn/.

Vijan S. Type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:ITC65–ITC80. https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC201911050.

Ma RCW. Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetic complications in China. Diabetologia. 2018;61:1249–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-018-4557-7.

Li J, Glenn AJ, Yang Q, Ding D, Zheng L, Bao W, et al. Dietary protein sources, mediating biomarkers, and incidence of type 2 diabetes: findings from the women’s health initiative and the UK Biobank. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:1742–53. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-0368.

Bloomgarden Z, Handelsman Y. How does CKD affect HbA1c?. J Diabetes. 2018;10:270. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.12624.

Chen K, Li C, Cornelius V, Yu D, Wang Q, Shi R, et al. Prognostic value of time in blood pressure target range among patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2022;10:369–79.

Doumas M, Tsioufis C, Fletcher R, Amdur R, Faselis C, Papademetriou V. Time in therapeutic range, as a determinant of all-cause mortality in patients with hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e007131.

Bakris G, Sternlicht H. Time in therapeutic range: redefining “optimal” blood pressure control. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1300–1.

Sundberg F, Smart CE, Samuelsson J, Åkesson K, Krogvold L. Using time in tight glucose range as a health-promoting strategy in preschoolers with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2025;48:6–14.

Wang Y, Lu J, Yu J, Ni J, Wang M, Lu W, et al. Association between time in tight range and incident diabetic retinopathy in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27:1415–22.

Vink RG, Roumans NJT, Arkenbosch LAJ, Mariman ECM, Van Baak MA. The effect of rate of weight loss on long-term weight regain in adults with overweight and obesity. Obesity. 2016;24:321–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21346.

Purcell K, Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Bouniu CJ, Delbridge E, Proietto J. The effect of rate of weight loss on long-term weight management: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:954–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70200-1.

Li X, Jiang L, Yang M, Wu YW, Sun JZ. Impact of weight cycling on CTRP3 expression, adipose tissue inflammation and insulin sensitivity in C57BL/6J mice. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:2052–9.

Yatsuya H, Tamakoshi K, Yoshida T, Hori Y, Zhang H, Ishikawa M, et al. Association between weight fluctuation and fasting insulinconcentration in Japanese men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:476–83.

Tamakoshi K, Yatsuya H, Kondo T, Ishikawa M, Zhang H, Murata C, et al. Long-term body weight variability is associated with elevated C-reactive protein independent of current body mass index among Japanese men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:1059–65.

Thillainadesan S, Madsen S, James DE, Hocking SL. The impact of weight cycling on health outcomes in animal models: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13416.

Tschöp MH, Friedman JM. Seeking satiety: from signals to solutions. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15:eadh4453.

Sakers A, De Siqueira MK, Seale P, Villanueva CJ. Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell. 2022;185:419–46.

Sea MM, Fong WP, Huang Y, Chen ZY. Weight cycling-induced alteration in fatty acid metabolism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1145–55.

Eguchi K, Manabe I, Oishi-Tanaka Y, Ohsugi M, Kono N, Ogata F, et al. Saturated fatty acid and TLR signaling link β cell dysfunction and islet inflammation. Cell Metab. 2012;15:516–33.

Rakha A, Mehak F, Shabbir MA, Arslan M, Ranjha MMAN, Ahmed W, et al. Insights into the constellating drivers of satiety impacting dietary patterns and lifestyle. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1002619.

Qi L, Shen H, Larson I, Barnard JR, Schaefer EJ, Ordovas JM. Genetic variation at the hormone sensitive lipase: gender-specific association with plasma lipid and glucose concentrations. Clin Genet. 2004;65:93–100.

Lombardo M, Feraco A, Armani A, Camajani E, Gorini S, Strollo R, et al. Gender differences in body composition, dietary patterns, and physical activity: insights from a cross-sectional study. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1414217.

Bédard A, Dodin S, Corneau L, Lemieux S. Impact of the traditional Mediterranean diet on the Framingham risk score and the metabolic syndrome according to sex. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2014;12:95–101.

World Obesity Atlas. 2023. https://www.worldobesityday.org/assets/downloads/World_Obesity_Atlas_2023_Report.pdf. Accessed 2 Aug 2024.

Hendryx M, Manson JE, Ostfeld RJ, Chlebowski RT, LeBlanc ES, Waring ME, et al. Intentional weight loss, waist circumference reduction, and mortality risk among postmenopausal women. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e250609. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.0609.

Morieri ML, Rigato M, Frison V, D’Ambrosio M, Sartore G, Avogaro A, et al. Early weight loss, diabetes remission and long-term trajectory after diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: a retrospective study. Diabetologia. 2025;68:1115–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-025-06402-w.

Yao S, Marron MM, Farsijani S, Miljkovic I, Tseng GC, Shah RV, et al. Metabolomic characterization of unintentional weight loss among community-dwelling older black and white men and women. Aging Cell. 2025;24:e14410. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.14410.

Acknowledgements

All authors thank the original data collectors, depositors, copyright holders, and funders of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. In addition, this analysis uses data or information from the Harmonized CHARLS Life History dataset and codebook, Version A as of July 2022 developed by the Gateway to Global Aging Data in collaboration with the University of Duesseldorf and the TU Dortmund University. The development of the Harmonized CHARLS was funded by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG030153, RC2 AG036619, R03 AG043052). For more information, please refer to https://g2aging.org/. This research was funded by the Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation [No. 2024JC-YBQN-0965].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. conceived and designed the study; L.Z. and C.C. performed the study; L.Z. analyzed the data and drafted the paper, Y.Z., and F.D. helped to study. All authors read, critically revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All authors have reviewed the final version of the manuscript and approved it for publication.

Ethical approval

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Peking University. Informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, C., Zhang, Y., Deng, F. et al. Long-term time in target range for body mass index (BMI) and diabetes incidence: insights from CHARLS. Nutr. Diabetes 15, 46 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-025-00404-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-025-00404-8