Abstract

Background

This study was designed to identify genes for further study as modifiers of the severity of cardiomyopathy in DMD-related Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD).

Methods

We evaluated genome sequencing results in a well-phenotyped DMD cohort with severe cardiomyopathy against those with less severe cardiomyopathy. Using combined annotation-dependent depletion variant annotation to look at variant burden, we created a difference between group mean (DBGM) summative C-Scores by gene. We completed analyses on three groups. For each analysis, we normalized DBGM summative C-Score and determined which genes had a value > three standard deviations from the mean in all three analyses.

Results

There were 54 DMD males in this analysis. 18 individuals (33%) had severe cardiomyopathy and 36 individuals (67%) had less severe cardiomyopathy. Nine genes were identified as possible cardiomyopathy severity modifiers: ANKLE1, ESRRA, FRAS1, GEMIN4, GXYLT1, MTCH2, PKD1L2, PRSS2 and QRFPR.

Conclusion

DBGM summative C-Scores in well-phenotyped groups are a feasible exploratory method to identify genetic targets for additional study. There is preliminary evidence from this and other studies suggesting further evaluation of ESRRA, GEMIN4, and MTCH2 as modifiers of cardiomyopathy severity could advance understanding of DMD cardiomyopathy progression.

Impact

-

This article identifies possible genetic modifiers of DMD cardiomyopathy severity via a novel method of looking at variant burden between groups. This adds to the existing literature by providing new evidence for modifier pathway targets for possible therapeutic targets or drug repurposing in a rare genetic disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DMD related Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked genetic disease caused by disruption of dystrophin and is associated with progressive muscle dysfunction resulting in respiratory compromise and cardiomyopathy.1,2,3,4,5 Supportive care advances have decreased respiratory death and simultaneously unmasked the lethal, fully penetrant cardiomyopathy phenotype, now the leading cause of death in DMD.1,2,3,4 Despite universal cardiomyopathy, the onset and pace of progression are quite variable complicating the determination of prognosis and optimal approach to therapy. Differences in dystrophin genotype do not explain the variability of the cardiac phenotype.6

This variability isn’t unique to cardiomyopathy in DMD.7,8 The search for genetic modifiers in cardiomyopathy phenotypes is a high priority since they can help with prognostication and therapeutic targets.9 There have been numerous approaches to identifying genetic modifiers in rare genetic diseases, but this remains a challenging area.10 This study uses a novel approach to identify possible genetic cardiomyopathy severity modifiers in a cohort of well phenotyped patients with DMD.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Vanderbilt University (IRB#181942) and Indiana University (IRB#1901898821).

Subjects

Subjects were identified from the “Development of a multimodal biomarker platform for predictive risk stratification of cardiac disease in Duchenne muscular dystrophy” study by the DMD cardiovascular care consortium, a multi-center consortium of 9 institutions funded by the NIH/NHLBI and the FDA.

Individuals with available biospecimens that met the clinical criteria were included in this study. Clinical criteria were based on cardiac phenotype and categorized into two groups, severe cardiomyopathy and less severe cardiomyopathy.

Phenotyping

Patients were prospectively enrolled and clinically available cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiograms were used to measure left ventricular ejection fraction to define the cardiac phenotype. The cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) left ventricular volume, mass, and ejection fraction were calculated from manually drawn contours of endocardial and epicardial borders in end-diastole and end-systole using QMas (MedisSuite 2.1, Medis, Leiden, The Netherlands). Whenever possible, the echocardiographic left ventricular ejection fraction was calculated using a 5/6 area length, as this has previously been shown to have the best reproducibility and strongest correlation with cMRI.11

Individuals were considered to have a severe cardiomyopathy if there was a clear cardiac mortality or a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40% under 20 years of age. Individuals were considered to have a less severe cardiomyopathy if they had a left ventricular ejection fraction over 40% over 20 years of age. Information provided in the details of cardiac phenotype reflect data available at the time of data set completion for this study, which occurred in November 2023.

Grouping

Three (sub)groups were used in this study. We had a subgroup of siblings discordant for cardiomyopathy severity phenotype (discordant sibling subgroup), a subgroup of study participants with no relatives in the study (unrelated participant subgroup), and the complete group of all study participants.

Genome sequencing

DNA was extracted from blood samples stored in the Vanderbilt cardiovascular translational and clinical research core for genome sequencing. Genome sequencing libraries were generated with the Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep Kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Illumina). 200 ng DNA was used as input. The resulting libraries were assessed with both Agilent Bioanalyzer and Qubit. The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with 150 bp paired-end reads.

The paired-end sequence data were analyzed with the Sentieon pipeline on the Google Cloud Platform (GCP). Sentieon (Sentieon, Inc, https://www.sentieon.com/) implements the GATK algorithm but with much faster speed.12 Sentieon version 202010.02 was used. The human hg38 reference genome bundle from the Broad public Google cloud bucket (//genomics-public-data/resources/broad/hg38/v0) was utilized. In brief, the GCP Sentieon analysis included alignment of sequence reads to the human reference genome hg38 using BWA-MEM, duplicated reads marking, indel realignment, base quality recalibration (BQSR), gvcf generation.13,14 A series of quality metrics including alignment stats and insert size metrics were generated during the process. Joint genotyping of all samples was performed with the gvcf files generated. The joint-genotyped variants were further analyzed with variant quality recalibration (VQSR) using Sentieon applying the parameters recommended by the GATK best practice.

Variant burden analysis and statistical analysis

The methods for variant burden analysis are summarized in Fig. 2 of the manuscript. To determine variant burden we utilized combined annotation dependent depletion (CADD), a variant assessment tool that is expressed as a numerical value.15,16 This system of variant annotation provides a standardized raw C-Score which can be utilized to provide relative predicted likelihood of a variant to be observed, with higher values having a lower likelihood to be observed.15,16 There is no C-Score that directly correlates with clinical variant pathogenicity.15,16 Raw C-Scores were annotated with CADD v1.6 for GRCh38.16

Each individual had an assessment for what we refer to as a “summative C-Score” for each gene. Summative C-Scores were calculated by determining the sum of all coding variants and coding change variants such as splicing variants in a gene with a raw C-Score greater than 2.5 using the plink 1.9 score function. Allelic scoring function using ‘sum’ parameter. “Protein coding changing variants” includes those variants with Annovar ExonicFunc.refGene annotation with the following values: exonic, exonic; splicing, splicing, frameshift deletion, frameshift insertion, nonsynonymous SNV, stopgain, stoploss, nonsynonymous, startloss, startgain, frameshift.

For each gene, a mean summative C-Score was calculated based on the cardiomyopathy severity group. Since genes have different lengths and tolerance for variation, the difference between group mean (DBGM) summative C-Scores for each gene was used to normalize values for comparison between genes. DBGM was calculated by taking the severe cardiomyopathy’s mean summative C-Score minus the less severe cardiomyopathy’s mean summative C-Score. This would mean genes with positive DBGM summative C-Scores have more variants in individuals with the severe cardiomyopathy, or variants in those genes could be potentially detrimental, and genes with negative DBGM summative C-Scores have more variants in individuals with the less severe cardiomyopathy, or variants in those genes could be potentially protective. The DBGM summative C-Scores for each gene was used to create a distribution in order to identify genes which were relative outliers in each group.

Statistical analysis of DBGM summative C-Score was completed with Stata Statistical Software (Stata BE 18.0, StataCorp, College Station Texas).17 Means with standard deviations and medians with interquartile ranges were calculated, histograms and boxplots were used to display the distribution of DBGM summative C-Score across genes. For each of the three groups, a list of genes with a DBGM summative C-Scores greater than three standard deviations from the mean were identified. Only genes that had concordant DBGM summative C-Scores greater than three standard deviations from the mean in all three groups were examined further. For these genes the probability that gene’s DBMG summative C-Score would be as extreme as what was found based on the mean and standard deviation was also determined for all three analyses. Once this gene list was identified the individual variants and the participants they were identified in were reviewed to look for patterns in number and type of variants contributing to the DBGM summative C-Score for each analysis. Basic descriptive statistics on specific cMRI parameters were also calculated.

Results

There were 54 DMD males included in this analysis. There were 18 individuals (33%) with severe cardiomyopathy and 36 individuals (67%) with less severe cardiomyopathy. There were 15 sets of siblings (31 individuals) in the analysis, which consisted of 14 sibling pairs and one sibling trio. There were 9 pairs of siblings (18 individuals) concordant for cardiomyopathy severity. There were 2 sibling pairs (4 individuals) concordant for severe cardiomyopathy and 7 sibling pairs (14 individuals) concordant for less severe cardiomyopathy. This is demonstrated in Fig. 1. The remaining 6 sibling sets (13 individuals) were discordant for cardiomyopathy severity. The trio sibling set had one sibling with severe cardiomyopathy and two siblings with less severe cardiomyopathy. These data are summarized in Table 1.

Cardiac phenotypic features

Full details of cMRI were available for 48 (89%) individuals in the study and key parameters are summarized in Table 1. In the 15 (83%) individuals with severe cardiomyopathy the average age of the most recent cMRI was 15.7 years old and there was an average left ventricular ejection fraction of 39.3%. Late gadolinium enhancement was observed in 16 (89%) of the individuals with severe cardiomyopathy and was noted on cMRI at an average age of 14.8 years old. There were 12 (67%) individuals with severe cardiomyopathy who died during the study period. Death occurred at an average age of 19.6 years old. Of note, all three individuals with severe cardiomyopathy who did not have full cMRI data available died, and it is thought that this is likely a major contributor to why this data was unavailable for review.

In the 33 (92%) individuals with less severe cardiomyopathy and full cMRI data the average age at most recent cMRI was 13.9 years old and there was an average left ventricular ejection fraction of 58.4%. Late gadolinium enhancement was observed in 24 (67%) of the individuals with less severe cardiomyopathy and was noted on cMRI at an average age of 14.2 years old. There was one individual who died with less severe cardiomyopathy during the study period at 23 years of age.

In addition to summarizing these features for the individuals with severe versus less severe cardiomyopathy we further divided by subgroups and summarized these data in Table 2.

Variant buden analysis

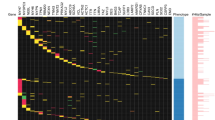

The variant burden analysis process and results are summarized in Fig. 2. The distribution of DBGM summative C-Score was based on data from 8155 genes with at least one individual with a variant above the threshold C-Score of 2.5. Table 3 shows the range, mean, and median DBGM summative C-Scores for all study participants, the discordant sibling subgroup, and the unrelated participants subgroup. The DBGM summative C-Score ranged from −7.503224 to 7.24595. The mean DBGM summative C-Score was 0.0070217 with a standard deviation of 0.4143616. The list of genes with DBGM summative C-Scores that were more than three standard deviations from the mean for all study participants included 159 genes, for the discordant sibling subgroup included 134 genes, and for the unrelated participants subgroup for 136 genes.

There were nine genes with DBGM summative C-Scores that were more than three standard deviations from the mean shared in the analyses of all study participants, the discordant sibling subgroup, and the unrelated participants subgroup. These nine genes were ANKLE1, ESRRA, FRAS1, GEMIN4, GXYLT1, MTCH2, PKD1L2, PRSS2, and QRFPR and the probability of each gene’s DBGM summative C-Score being as extreme by each of the three analyses are summarized in Table 4. Figure 3 shows histograms of where each gene fell in each of the three analyses. Five of the genes, ANKLE1, ESRRA, GXYLT1, MTCH2, and QRFPR, had scores suggestive that these genetic variants could be protective against severe CMP. Four genes, FRAS1, GEMIN4, PKD1L2, and PRSS2 had scores suggestive that these genetic variants could be a risk factor for severe CMP. The comprehensive list of variants that contributed to each gene’s DBGM summative C-Score, and how much the variant contributed to a gene’s DBGM summative C-Score for each analysis, are available in the supplemental variant information file.

The x axis is the difference between group means and the y axis represents the percentage of the 8155 genes analyzed with that value for a difference between group means. The bold vertical dashed lines represent the three standard deviation cut offs used in the analysis. Genes with negative values to the left are potentially protective and genes with positive values to the right are potentially detrimental. a is the analysis of all study participants, b is the subgroup analysis for discordant siblings and c is the analysis of unrelated participants. SD Standard Deviation.

Potentially protective genes of interest

ANKLE1, (ankyrin repeat and LEM domain containing 1) had a negative DBGM summative C-Score, suggesting variants in this gene could potentially be protective against severe cardiomyopathy. Four missense variants accounted for the DBGM summative C-Score.

ESRRA (estrogen-related receptor alpha) had a negative DBGM summative C-Score, suggesting variants in this gene could potentially be protective against severe cardiomyopathy. Six missense variants accounted for the DBGM summative C-Score. All six of the ESRRA variants were uncommon (gnomAD allele frequencies ranging between 2.22-3.11%) and consistently had negative DBMG across all three subgroup analyses (supplemental variant information file).

GXYLT1, (glucoside xylosyltransferase 1) had a negative DBGM summative C-Score, suggesting variants in this gene could potentially be protective against severe cardiomyopathy. Eight missense variants and one nonsense variant accounted for the DBGM summative C-Score.

MTCH2 (mitochondrial carrier homolog 2) had a negative DBGM summative C-Score, suggesting variants in this gene could potentially be protective against severe cardiomyopathy. Five missense and two nonsense variants accounted for the DBGM summative C-Score. The DBGM summative C-Score of MTCH2 had one of the lowest probabilities seen in our study, particularly in the discordant sibling group (Table 4).

QRFPR (pyroglutamylated RFamide peptide receptor) had a negative DBGM summative C-Score, suggesting variants in this gene could potentially be protective against severe cardiomyopathy. Five missense variants accounted for the DBGM summative C-Score.

Potentially increased risk genes of interest

FRAS1 (Fraser extracellular matrix complex subunit 1) had a positive DBGM summative C-Score, suggesting variants in this gene could potentially increase risk for severe cardiomyopathy. Ten missense variants accounted for the DBGM summative C-Score.

GEMIN4 (gem nuclear organelle-associated protein 4) had a positive DBGM summative C-Score, suggesting variants in this gene could potentially increase risk for severe cardiomyopathy. Six missense variants accounted for the DBGM summative C-Score.

PKD1L2 (polycystin 1 like 2 (gene/pseudogene)) had a positive DBGM summative C-Score, suggesting variants in this gene could potentially increase risk for severe cardiomyopathy. Seventeen missense variants, one +2 splice site variant, and three nonsense variants accounted for the DBGM summative C-Score. In gnomAD v4.1.0 PKD1L2 has a Probability of being Loss of function Intolerant (pLI) of 0 and an observed to expected loss of function variant ratio of 1.33 suggesting that loss of function is tolerated and not under selection pressures.

Reviewing the PKD1L2 variants in depth showed a number of common variants contributing to the DBGM inconsistently and that the largest contribution to the score for this gene in each analysis is a single variant (PKD1L2 c.658C>T; p.Gln220*). The PKD1L2 c.658 C > T variant is present in 31.99% of individuals in gnomAD v4.1.0 and the raw C-score for this variant is 11.62, the highest of any variant across our genes of interest. Due to the specifics of a single, common variant with a high raw C-Score driving the DBGM we are inclined to think this is an artifact of the method versus a target for further study.

PRSS2 (serine protease 2) had a positive DBGM summative C-Score, suggesting variants in this gene could potentially increase risk for severe cardiomyopathy. Eight missense variants, one +1 splice site variant, and one nonsense variant accounted for the DBGM summative C-Score. One specific area of caution is that PRSS2 has homology with a few other genes and pseudogenes.18,19,20

Discussion

The results of this study show that utilizing DBGM summative C-Score to assess variant burden in well phenotyped rare disease cohorts may be a reasonable method to identify genetic targets for future study. Of our nine genes of interest, we found common pathways such as insulin resistance and inflammation summarized in Table 5. We found information supporting further investigation of MTCH2, ESSRA, and GEMIN4 in particular.

Dystrophin is a cytoskeletal protein that forms a critical part of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex in skeletal and cardiac muscle linking the extracellular membrane to the intracellular cytoskeleton.21,22,23 Dysfunctional dystrophin leads to myonecrosis that results in inflammation and over time regeneration is impaired, coupled with development of fibrosis. 2,3,22,24 Treatment with steroids to reduce inflammation and delay fibrosis is standard of care and has been shown to prolong ambulation.24 Even with treatment, skeletal muscle is progressively replaced with fibrofatty tissue.3,24

Decreased energy expenditure due to lack of ambulation and chronic steroid treatment contribute to obesity and insulin resistance.24,25 There is evidence that patients with DMD also have insulin resistance independent of steroid treatment.21 Abnormalities in the dystrophin glycoprotein complex may inhibit cellular signaling in the skeletal muscle, thus contributing to insulin resistance through decreased glucose uptake.21 Insulin-dependent transport of glucose into skeletal and cardiac muscle cells is primarily achieved through glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4).26,27 Muscle biopsies of patients with DMD demonstrated abnormal cytoplasmic aggregates of GLUT4, suggesting impaired GLUT4 translocation.21

Cardiomyopathy also increases insulin resistance.26,28,29 This is likely in part because the failing heart has reduced mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity which leads to an increased reliance on glycolysis.27,28,29,30 DMD patient pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in culture show similar metabolic findings over time.2

Due to the high energy demands of cardiac tissue, under normal conditions, approximately 95% of the heart’s energy requirements are the result of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and the rest is from glycolysis.27,28 The decreased energetic efficiency in the failing heart is associated with increased cardiomyocyte oxidative stress with increased concentrations of reactive oxygen species.5,27,29,30 DNA damage from increased reactive oxygen species upregulates p53 expression.29,31 Significant upregulation of p53 seems to further drive mitochondrial dysfunction and exacerbate heart failure.31,32

Loss of function for MTCH2 is a promising target of future research as a protective factor increasing resistance to cardiomyopathy in patients with DMD. Deficiency of MTCH2 seems to protect against insulin resistance.33,34 Mouse models suggest that loss of function of Mtch2 in skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle cause lower body fat levels and lower levels of circulating insulin.33 They also found increased cardiac function with increases in stroke volumes and ejection fraction.33 Metabolic testing of muscle tissue from these mice showed increased glucose uptake, increased evidence of glycolysis, increased muscle glycogen content, and overall increased energy expenditure.33 A study looking at 50% reduced cardiac tissue expression of the MTCH2 ortholog Mtch in Drosophila found it was associated with increased glycolysis and reduced lifespan.34

The MTCH2 c.229A>T (p.Arg77*) nonsense variant in our population was found at an allele frequency of 8.3% in individuals with a severe cardiomyopathy and at an allele frequency of 29.2% in individuals with a less severe cardiomyopathy (supplemental variant information file). Both of these were higher than the gnomAD v4.1.0 allele frequency of 2.8%. Specifically looking at the discordant sibling subgroup, this variant was present in all six discordant sibling sets. For five of the six discordant sibling sets it was found in only the less severe cardiomyopathy sibling (six individuals) and for the final discordant sibling set it was found in both the severe cardiomyopathy sibling and the less severe cardiomyopathy sibling. This variant was the largest contributor to the MTCH2 DBGM summative C-Score in all three analyses (supplemental variant information file). Based on these findings and what is known about intrinsic and extrinsic risk for insulin resistance in DMD, it is a reasonable hypothesis that decreased MTCH2 function is a unique protector against cardiomyopathy in DMD through protection against insulin resistance and cardiac metabolic decompensation.

ESRRA is a nuclear receptor expressed in tissues that preferably rely on fatty acid oxidation, including the heart.35 ESRRA is known to regulate critical metabolic genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial maintenance.35 Mouse models that are null for ESRRA have resistance to obesity.35 The ESRRA activator, genistein, also seems to protect against obesity.35 Activation of ESRRA has also been proposed as a target for therapy for insulin resistance.35 Though ultimately there seems to be some conflicting results between tissue level effects and organism level effects that make it unclear if reducing or increasing ESRRA would be most beneficial to prevent certain metabolic anomalies.35 It seems reasonable to hypothesize that altering the function of ESRRA might be able to modify DMD cardiomyopathy severity through its effects on metabolism, though what level and type of alteration to function would be difficult to predict.

GEMIN4 is an interesting result as it has been previously assessed as a potential therapeutic target for heart failure due to its interaction with the mineralocorticoid receptor.36 Decreased expression of GEMIN4 increased mineralocorticoid receptor expression.36 This supports a hypothesis that increased variation in GEMIN4 could lead to decreases in its functionality that modify risk for heart failure. Mineralocorticoid receptors are already an identified target for therapeutics in DMD and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists are routinely used in heart failure management by DMD experts.37,38,39 This could make GEMIN4 a unique target of further study and assessment for therapeutic potential.

Overall, this study supports that use of DBGM summative C-Score to assess variant burden in well-defined rare disease cohorts, such as DMD may be a reasonable method to identify targets for future study. For DMD, additional studies into the role of at least ESRRA, GEMIN4, and MTCH2 in modifying risk of cardiomyopathy severity are warranted.

Limitations of our study include that we are unable to know the phase of specific variants, our cohort has a high number of sibling sets, and that this method provides no functional evidence of the implications of the genes of interest or the specific variants’ effect on gene function. Since variant phase is unknown, we are unable to determine if the presence of multiple variants in a single individual reflects biallelic variation. The high number of sibling sets limits our ability to compare variant frequency to general population allele frequencies. Additionally, while this study identified genes to potentially target in future studies, it does not provide any conclusive evidence if these genes have a role in modifying risk for cardiomyopathy in DMD.

Strengths of this study include that our cohort is well phenotyped with detailed information on cardiac function over time, cross-analysis with subgroups, and that our genes of interest were clearly involved in pathways relevant to DMD. The detailed phenotype information allowed us to normalize factors such as gene length by being able to define clear, separate groups to use to define DBGMs. Our subgroup analyses allowed us to narrow the genes of focus to ones that were shared as differentiating between discordant siblings and unrelated participants to compensate for any biases from having multiple sibling sets in our cohort. Being able to easily connect the final list of genes to pathways clearly relevant to DMD also allowed for us to have support that further evaluation of the genes of interest identified by this method are reasonable targets of future studies.

Data availability

To promote transparency and openness, data not available in the paper or supplemental materials will be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Soslow, J. H. et al. The role of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in Duchenne muscular dystrophy cardiomyopathy. J. Card. Fail. 25, 259–267 (2019).

Willi, L. et al. Bioenergetic and metabolic impairments in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes generated from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 9808 (2022).

Chang, M. et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: pathogenesis and promising therapies. J. Neurol. 270, 3733–3749 (2023).

Soslow, J. H. et al. Cardiovascular measures of all-cause mortality in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Circ. Heart Fail. 16, e010040 (2023).

Bez Batti Angulski, A. et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: disease mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Front. Physiol. 14, 1183101 (2023).

Tandon, A. et al. Dystrophin genotype-cardiac phenotype correlations in duchenne and becker muscular dystrophies using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Am. J. Cardiol. 115, 967–971 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Identifying modifier genes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 144, 119–126 (2020).

Glavaški, M., Velicki, L. & Vučinić, N. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: genetic foundations, outcomes, interconnections, and their modifiers. Medicina 59, 1424 (2023).

Gacita, A. M. et al. Genetic variation in enhancers modifies cardiomyopathy gene expression and progression. Circulation 143, 1302–1316 (2021).

Rahit, K. M. T. H. & Tarailo-Graovac, M. Genetic modifiers and rare Mendelian disease. Genes 11, 239 (2020).

Soslow, J. H. et al. Evaluation of echocardiographic measures of left ventricular function in patients with duchenne muscular dystrophy: assessment of reproducibility and comparison to cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 29, 983–991 (2016).

Kendig, K. I. et al. Sentieon Dnaseq variant calling workflow demonstrates strong computational performance and accuracy. Front. Genet. 10, 736 (2019).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. Vol. arXiv:1303.3997v1 [q-bio.GN] (2013).

Kircher, M. et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 46, 310–315 (2014).

Rentzsch, P., Schubach, M., Shendure, J. & Kircher, M. Cadd-splice-improving genome-wide variant effect prediction using deep learning-derived splice scores. Genome Med. 13, 31 (2021).

Stata Statistical Software v. Release 18 (Stata Press, 2023).

Weiss, F. U., Laemmerhirt, F. & Lerch, M. M. Next-generation sequencing pitfalls in diagnosing trypsinogen (Prss1) mutations in chronic pancreatitis. Gut 70, 1602–1604 (2021).

Génin, E., Cooper, D. N., Masson, E., Férec, C. & Chen, J. M. Ngs mismapping confounds the clinical interpretation of the PRSS1 p.Ala16Val (c.47C>T) variant in chronic pancreatitis. Gut 71, 841–842 (2022).

Lou, H., Xie, B., Wang, Y., Gao, Y. & Xu, S. Improved Ngs variant calling tool for the PRSS1–PRSS2 locus. Gut 72, 210–212 (2023).

Rodríguez-Cruz, M. et al. Evidence of insulin resistance and other metabolic alterations in boys with duchenne or becker muscular dystrophy. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 867273 (2015).

Grounds, M. D. et al. Biomarkers for duchenne muscular dystrophy: myonecrosis, inflammation and oxidative stress. Dis. Model. Mech. 13, dmm043638 (2020).

Wilson, D. G. S., Tinker, A. & Iskratsch, T. The role of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex in muscle cell mechanotransduction. Commun. Biol. 5, 1022 (2022).

Strakova, J. et al. Integrative effects of dystrophin loss on metabolic function of the Mdx mouse. Sci Rep 8, 13624 (2018).

Saure, C., Caminiti, C., Weglinski, J., de Castro Perez, F. & Monges, S. Energy expenditure, body composition, and prevalence of metabolic disorders in patients with duchenne muscular dystrophy. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 12, 81–85 (2018).

Szablewski, L. Glucose transporters in healthy heart and in cardiac disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 230, 70–75 (2017).

Lopaschuk, G. D., Karwi, Q. G., Tian, R., Wende, A. R. & Abel, E. D. Cardiac energy metabolism in heart failure. Circ. Res. 128, 1487–1513 (2021).

Meng, S. et al. Advances in metabolic remodeling and intervention strategies in heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 17, 36–55 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Sglt2 inhibitors break the vicious circle between heart failure and insulin resistance: targeting energy metabolism. Heart Fail. Rev. 27, 961–980 (2022).

Fan, L. et al. Driving force of deteriorated cellular environment in heart failure: metabolic remodeling. Clinics 78, 100263 (2023).

Men, H. et al. The regulatory roles of P53 in cardiovascular health and disease. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 78, 2001–2018 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. P53-Dependent mitochondrial compensation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e024582 (2022).

Buzaglo-Azriel, L. et al. Loss of muscle Mtch2 increases whole-body energy utilization and protects from diet-induced obesity. Cell. Rep. 14, 1602–1610 (2016).

Fischer, J. A. et al. Opposing effects of genetic variation in Mtch2 for obesity versus heart failure. Hum. Mol. Genet. 32, 15–29 (2023).

Tripathi, M., Yen, P. M. & Singh, B. K. Estrogen-related receptor alpha: an under-appreciated potential target for the treatment of metabolic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1645 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Gemin4 functions as a coregulator of the mineralocorticoid receptor. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 54, 149–160 (2015).

Villa, C. et al. Current practices in treating cardiomyopathy and heart failure in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD): understanding care practices in order to optimize DMD heart failure through action. Pediatr. Cardiol. 43, 977–985 (2022).

Landfeldt, E. et al. Predictors of cardiac disease in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a systematic review and evidence grading. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 19, 359 (2024).

Wittlieb-Weber, C. A. et al. Cardiac medication use in action for Duchenne muscular dystrophy cardiomyopathy. Pediatr. Cardiol. (2025). Epub ahead of print.

Funding

This work was completed with funding from the Ackerman/Nicholoff Family DMD Discovery Gift, Food and Drug Administration Orphan Products Grant R01FD006649, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health award F30HL162452. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C.G.: Concept/Design, Data Collection, Data Analysis/Interpretation, Drafting Article, Critical Revision of Article, Approval of Article. S.M.W.: Concept/Design, Data Analysis/Interpretation, Critical Revision of Article, Approval of Article. T.S.A.: Concept/Design, Data Collection, Data Analysis/Interpretation, Critical Revision of Article, Approval of Article. M.A.A.: Concept/Design, Data Collection, Data Analysis/Interpretation, Critical Revision of Article, and Approval of Article. J.J.P.: Concept/Design, Data Analysis/Interpretation, Critical Revision of Article, Approval of Article. C.C.E.: Concept/Design, Data Analysis/Interpretation, Critical Revision of Article, Approval of Article. J.H.S.: Concept/Design, Data Collection, Data Analysis/Interpretation, Critical Revision of Article, Approval of Article. L.W.M.: Concept/Design, Data Collection, Data Analysis/Interpretation, Drafting Article, Critical Revision of Article, Approval of Article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.S. has worked as a consultant for: Boerhinger Ingelheim, Capricor, Dyne, Fibrogen, Immunoforge, Sardocor and Sarepta. The other authors have no conflicts of interest or disclosures.

Consent statement

Consent was required from patients or their legal guardian to participate in this research study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geddes, G.C., Ware, S.M., Schwantes-An, TH. et al. Variant burden and severity of cardiomyopathy in patients with DMD-related Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Res (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04683-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04683-w