Abstract

Hypertension is a serious global health problem. Hypertensive retinopathy is generally considered to be a predictor of vascular disease elsewhere in the human body. In the past few decades, a variety of grading systems have been proposed for hypertensive retinopathy. However, these grading systems have some limitations. This study utilized optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) to investigate the morphological changes and macular retinal microvasculature in depth among 100 patients with hypertensive retinopathy and 66 healthy participants. Five main pathological changes were discovered in hypertensive retinopathy, as follows: focal capillary sparsity, scattered microangioma, focal macular arch ring defects, focal capillary disorder, and focal capillary nonperfusion at the levels of the superficial and deep vascular networks. In addition, we have found that the number of various pathological changes shows an increasing trend as hypertensive retinopathy progresses and may be related to renal damage. Finally, deep vessel density tended to decrease with progressive stages of hypertensive retinopathy and could be the best indicator to predict the risk of hypertensive retinopathy. Our study, therefore, proposes 3 stages of hypertensive retinopathy without macular edema according to the pathophysiology found by OCTA: stage 1 (only focal capillary sparsity), taking the place of KWB grade I; stage 2 (focal capillary sparsity and scattered microangioma), taking the place of KWB grade II; and stage 3 (focal capillary sparsity, scattered microangioma, focal capillary disorder, and nonperfusion), taking the place of KWB grade III. Hence, OCTA may be a potentially useful tool for evaluating the pathophysiology and staging of hypertensive retinopathy. Further longitudinal prospective studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is a serious global health problem and is common in China [1, 2]. It has been reported that the prevalence of hypertension in adults aged 45–59 and 35–75 years old in China is 29.1% and 44.7%, respectively [2, 3]. Longstanding hypertension can cause cerebral, cardiac, renal, and retinal end-organ damage [4]. In the presence of hypertension, hypertensive retinopathy is generally considered to be a predictor of vascular disease elsewhere in the body [5, 6]. The transparent media of the eyeball allow retinopathy to be observed directly [6].

According to the different clinical stages of disease development, narrowing of retinal arteries, arteriovenous crossings, the formation of retinal microaneurysms, fundus hemorrhages, hard exudates, and cotton-wool spots, or a combination of these signs may occur in hypertensive retinopathy [6,7,8]. In the past few decades, a variety of grading systems have been proposed for hypertensive retinopathy [6, 8]. The traditional classification of hypertensive retinopathy is based on the Keith–Wagener–Barker (KWB) grading system and remains the most widely used [9, 10]. For reasons of simplifying clinical practice, the Mitchell–Wong grading system was proposed in 2004, combining grades I and II of KWB in one stage [9]. However, these two grading systems have some limitations, such as variability in subjective among clinicians and difficulty in distinguishing between first and second grades for the KWB grading system [9]. Recently, another classification was proposed based on optical coherence tomography features, but it was applicable only to severe hypertension [11].

Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) is a new high-resolution fundus angiography technology. Since it was approved by the FDA at the end of 2016, OCTA has been widely used in the clinic, and it has been particularly useful in retinal vascular diseases such as diabetic retinopathy and retinal venous occlusion [12,13,14,15]. It can display the retinal capillary network in layers and quantify macular vascular density and arch area using various retinal vascular metrics such as vessel density, perfusion density, and foveal avascular zone characteristics in a rapid, noninvasive manner [12, 13, 16]. However, there have been very few reports on OCTA imaging in hypertensive retinopathy thus far [17, 18], and these two studies merely investigated the changes in capillaries in the superficial retina. In addition, the subjects were limited to relieved grade IV hypertensive retinopathy according to the KWB classification system [10] and hypertensive patients without retinopathy [17, 18].

In the current study, we first evaluated the morphological characteristics of superficial and deep retinal microvascular changes with the development of hypertensive retinopathy in grade I-III hypertensive retinopathy patients. Then, we performed a detailed quantitative analysis of the foveal avascular zone area, perimeter, circularity, and macular vascular density measured by vessel density and perfusion density in the study population. In addition, we analyzed the correlation of these parameters with hypertensive retinopathy and explored its association with other organ damage using OCTA.

Methods

Participants

This retrospective observational clinical study was approved by the Office of Research Ethics, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, China, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Each participant was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients with a diagnosis of hypertension with hypertensive retinopathy who underwent OCTA for one or both eyes at the Department of Ophthalmology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University between May 1st, 2018, and January 31st, 2019, were evaluated. The data, including BMI, blood pressure (BP), dyslipidemia, history of cardiovascular events, serum creatinine, eGFR, and urine albumin creatinine ratio, were collected by trained investigators in strict accordance with the standard operating procedure. Hypertension was defined as an average systolic BP of at least 140 mmHg or an average diastolic BP of at least 90 mmHg according to the Chinese hypertension treatment guidelines [19]. All hypertensive and healthy participants underwent standard ophthalmic examination and high-resolution optical coherence tomography (OCT; RS-3000 Nidek Co. Ltd., Japan). Before the acquisition of the OCTA scans, the stage of hypertensive retinopathy was determined with fundus examination by 2 independent investigators (LY, JZ) based on the KWB grading system [10], which is defined by four grades of retinal damage: grade I (arterial narrowing), grade II (arteriovenous crossings), grade III (hemorrhages and exudates), and grade IV (papilledema). Subjects with macular edema on OCT, previous ocular surgery or other known ocular or systemic diseases were excluded.

Optical coherence tomography angiography

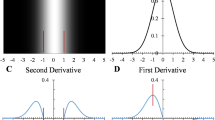

OCTA images were obtained with the RS-3000 Advance OCTA system (Nidek Co. Ltd., Japan). This system operates at 53 000 A-scans per second with a wavelength of 880 nm. The axial and transverse resolutions are 7 and 20 µm, respectively, in tissues. Angioscan 1.8.0 OCTA software was used to acquire a 3 × 3-mm macular map consisting of 256 B-scans separated by 11 µm [20]. OCTA images of the superficial and deep retinal capillary networks were generated automatically by the software of the device. The boundaries of the superficial capillary network extended from the internal limiting membrane to 12 µm below the outer border of the inner plexiform layer. The deep capillary network extended from 8 µm below the outer border of the inner plexiform layer to the outer border of the outer plexiform layer.

Two experienced investigators (LY, JZ) independently reviewed the OCTA images. Eyes with poor image quality due to opacity of the medium, poor fixation, artifacts, or low signal intensity index (<8/10) were excluded. In order to prevent OCTA stratification from being affected by changes in retinal anatomy, eyes with macular changes identified by OCT examination were also excluded. Of the 132 control eyes and 200 eyes with hypertensive retinopathy, 20 (15.2%) and 38 (19.0%) eyes were excluded, respectively, based on the criteria mentioned above.

Quantitative measurements

The central macular thickness in a 1-mm-diameter circular region at the fovea was measured using a 512 × 128 macular cube combination scan modev [18]. Using the acquired images, measurements of the foveal avascular zone area, perimeter, and circularity were calculated using the Angioscan 1.8.0 OCTA software at the level of the superficial vascular network. Vessel density and perfusion density in superficial and deep layers were calculated automatically by the software. Vessel density was defined as the total length (mm) of the blood vessels per unit area in a measured region (mm2), and its unit was mm−1. Perfusion density was defined as the total area (mm2) of the blood vessels per unit area in a measured region (mm2), and its unit was %.

Statistical analysis

All data management and statistical analyses were performed using Stata/MP 15.1 for Windows (Copyright 1985-2017 Stata Corp LLC) and Rstudio 1.1.456 for Windows (Copyright 2009-2018 Rstudio, Inc.). In order to facilitate analysis, the eyes were grouped in two ways: (1) Grade I, Grade II, and grade III hypertensive retinopathy and healthy controls, defined according to the severity of the disease; (2) case and control groups, defined according to whether they had hypertensive retinopathy. The distributions of continuous data were tested for normality with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test before statistical analysis. Continuous data following the normal distribution were described as the mean ± standard deviation, and analysis of variance with a post hoc Tukey test (or the independent t test) was performed to compare the differences among the four groups (or between the two groups). Otherwise, the median (Q1, Q3) and the Kruskal–Wallis H-test (or Mann–Whitney U-test) were used. For categorical variables, a χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test) was applied to evaluate the differences in the above groups. Kappa values were calculated to assess the degree of agreement of the KWB and OCTA grading systems for hypertensive retinopathy without macular edema. The Z-value was calculated with an Excel macro (http://www.agr.niigata-u.ac.jp/~muratac/), and the P value = NORMSDIST(-ABS(Z-value)).

The relationship between OCTA-based staging of hypertensive retinopathy and other organ damage was determined by logistic regression analyses.

In order to further study the impact of various factors on hypertensive retinopathy, and considering the independence of binocular indicators, the associations between hypertensive retinopathy and the parameters of OCTA, age, and gender were examined by generalized estimating equations (GEEs). The possible confounding factors, such as age, gender, systolic BP, and central macular thickness, were adjusted. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) was estimated to determine the cutoff point of vessel density or perfusion density and the ability of each parameter to predict hypertensive retinopathy. Considering the high correlation between right and left eyes, ROC and logistic regression analyses were performed for right and left eyes, respectively. All tests were two-sided, and P ≤ 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

In total, 162 eyes from 94 patients with hypertensive retinopathy and 112 control eyes from 60 healthy participants were included in this study. Demographic and clinical data are listed in Table 1, which shows that participants in these groups were not well balanced (P < 0.05), indicating that age, gender, BMI, BP, dyslipidemia, history of cardiovascular events, duration of hypertension, serum creatinine, eGFR, and urine albumin creatinine ratio may be significantly associated with hypertensive retinopathy.

Comparisons of optical coherence tomography and angiography parameters between control eyes and eyes with hypertensive retinopathy

Hypertensive retinopathy was classified as grade I in 30 eyes, grade II in 72 eyes and grade III in 60 eyes (Table 2). There were significant differences in foveal avascular zone area, central macular thickness, superficial and deep vessel density and perfusion density among the four groups—the grade I, grade II, and grade III hypertensive retinopathy groups and the control group (P < 0.05). Compared with the control eyes, the foveal avascular zone area tended to increase in grade I hypertensive retinopathy and then decreased with increasing hypertensive retinopathy severity, which was statistically smaller in grade III hypertensive retinopathy eyes than in grade I hypertensive retinopathy eyes (P = 0.01) or grade II hypertensive retinopathy eyes (P = 0.03). The central macular thickness was significantly thinner in hypertensive retinopathy eyes than in controls (P = 0.006), especially in grade I hypertensive retinopathy eyes (P = 0.046). Superficial and deep vessel density and perfusion density were similar between grade I hypertensive retinopathy eyes and controls (all P ≥ 0.05); however, they decreased significantly in grade II and grade III eyes compared with the controls (all P ≥ 0.05) and tended to decrease with advancing stages of hypertensive retinopathy (Figs. 1 and 2).

Characteristics of macular retinal microvasculature abnormalities based on optical coherence tomography angiography in hypertensive retinopathy

The morphological characteristics of superficial and deep retinal microvascular changes in grade I-III hypertensive retinopathy patients were analyzed by OCTA. The five main pathological changes (Table 3 and Fig. 3) were focal capillary sparsity, scattered microangioma, focal macular arch ring defects, focal capillary disorder, and focal capillary nonperfusion at the level of the superficial and deep vascular networks of eyes with hypertensive retinopathy. In grade I hypertensive retinopathy eyes, the first pathological changes in OCTA were deep retinal focal capillary sparsity (33.3%) and corresponding superficial and deep retinal focal macular arch ring defects (16.6%). In grade II hypertensive retinopathy eyes, a small number of superficial and deep retinal scattered microangiomas began to appear. Notably, superficial and deep retinal focal capillary disorders (18.3%) and superficial and deep retinal focal capillary nonperfusion (25.0%) appeared only in grade III hypertensive retinopathy eyes. Moreover, as the stage of hypertensive retinopathy progressed, the number of various pathological changes showed an increasing trend, and there was a significant difference among the four groups (all P < 0.001, Table 3).

Changes in superficial and deep retinal capillary measurements using optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA, 3 × 3 mm scans) in patients with hypertensive retinopathy (HR). A and a, respectively, show a few focal scattered microangioma-like changes (arrows) in the superficial and deep retinal capillary plexus below the macular fovea of the left eye of a 50-year-old female patient (grade II HR). B and b, respectively, show extensive sparse foci (pentagrams) of local retinal capillaries in the superficial vascular plexus and deep capillary plexus of the retina around and below the macular arch ring of the right eye of a 46-year-old male patient (grade III HR). C and c, respectively, show the superficial and deep retinal capillary angiograms of the left eye of a 34-year-old male patient (grade III HR). Focal retinal capillary disorder (ellipses) and sparse foci (triangles) are found above the central fovea of the superficial and deep retinal vessel networks, and the upper and lower parts of the deep arch ring are obviously damaged (arrows). D and d, respectively, show that the superficial and deep macular arch rings are destroyed (arrows) with scattered focal retinal capillary nonperfusion areas (triangles) in the left eye of a 43-year-old male patient (grade III HR). E and e, respectively, show the large retinal capillary nonperfusion areas (triangles) above the temporal fovea of the superficial and deep retinal capillaries with residual vascular tortuosity and dilatation (thick arrows) and scattered microangioma-like changes (fine arrows) in the left eye of a 40-year-old male patient (grade III HR)

Classification systems for hypertensive retinopathy and interobserver agreement for KWB and OCTA classification systems

The fundus color photos and OCTA images from a total of 90 eyes were randomly graded by two residents using two hypertensive grading systems: KWB and OCTA (Table 4). Kappa (standard error) values were calculated to assess the degree of agreement for interrater reliability (IRR). The interobserver agreement of both residents was also compared with a “gold standard” for retinal grading developed by two senior retinal experts (LY, JZ). Kappa is interpreted qualitatively using the following criterion: good agreement, 0.60–0.80; very good agreement, 0.80–1.00. Obviously, comparing the kappa values of the two grading systems, the IRR of OCTA was better than that of KWB in this study (0.891 vs. 0.784). When compared with the gold standard grading, the same result can be obtained (0.959 and 0.932 vs. 0.865 and 0.843). After statistical analysis with an Excel macro, the IRR of OCTA was also better than that of KWB, especially for resident 1 (Table 4, Z = −2.05, P < 0.05), indicating that OCTA is a good predictor for the common use of hypertension grading.

Associations of staging of hypertensive retinopathy using optical coherence tomography angiography and other organ damage

In this study, since the involvement of the retina in hypertension is similar to blood vessel damage in the kidneys, we mainly evaluated the correlation between retinal and renal injury in patients with hypertension. Renal damage [21] was defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Table 5 shows that the relationship between renal damage and the classification of OCTA is relatively obvious. Compared to patients with OCTA stage 1, those with stages 2 and 3 hypertensive retinopathy were 3.9 and 5.6 times more likely to have renal damage, respectively (P < 0.05). For cardiovascular events, in this study, due to the small sample size, we found only that the cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension were higher than those in the control group (Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.05). We did not find an increasing trend in cardiovascular events with increasing retinal OCTA classification. We will further expand the sample size for additional research in the future.

Association between hypertensive retinopathy and optical coherence tomography angiography measurement

Considering the independence of binocular indicators, GEEs were used to examine the associations between hypertensive retinopathy and optical coherence tomography angiography measurement, age, and gender. Our data clearly showed that hypertensive retinopathy was significantly associated with age, gender, systolic BP, central macular thickness, superficial and deep vessel density (P < 0.001), and superficial and deep perfusion density (all P < 0.04) in the 274 studied eyes. In order to further analyze the correlation between vessel density and perfusion density and hypertensive retinopathy risk, 274 eyes were divided into four equal parts according to the value of vessel density and perfusion density into superficial and deep layers before and after adjusting for the related confounding factors. Table 6 shows that only deep vessel density is significantly related to hypertensive retinopathy risk after adjusting for the related confounding factors. Compared with the first group, the ORs (95% CI) of deep vessel density in the second, third and fourth groups were 0.90 (0.19, 4.18), 0.29 (0.08, 1.06) and 0.15 (0.04, 0.53), respectively. The linear trend for deep vessel density was significant (P < 0.001). These data show that the lower the deep vessel density, the greater the risk of hypertensive retinopathy; the findings also confirm that deep vessel density is an independent risk factor for hypertensive retinopathy and can be defined as a marker for the prediction of hypertensive retinopathy.

Based on ROC analyses, the AUC (95% CI), sensitivity, specificity and accuracy for vessel density and perfusion density in predicting hypertensive retinopathy are presented in Fig. 4 and Table 7. The AUC (95% CI) of deep vessel density was 0.70 (0.61, 0.79) in the right eye and 0.77 (0.69, 0.85) in the left eye, making it the most indicative single variable. There was no significant difference compared with the combined index (right eyes, P = 0.17; left eyes, P = 0.83). Therefore, deep vessel density may be the best indicator to predict the risk of hypertensive retinopathy in this study. The optimal cutoff points, representing the largest sum of sensitivity and specificity, are 19.36 mm−1 (right eye) and 20.15 mm−1 (left eye) based on the results of the ROC analyses.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the ROC curve (AUC) showing the ability of vessel density (VD) or perfusion density (PD) to indicate hypertensive retinopathy (HR). a and b represent the ability of VD and PD in the right and left eyes, respectively, to indicate HR. Model 1, Model 2, Model 3, Model 4, and Model 5 indicate the ROCs and AUCs of deep vessel density; superficial vessel density; deep perfusion density; superficial perfusion density; and the combination of superficial vessel density, deep vessel density, superficial perfusion density, and deep perfusion density

Discussion

The classical pathophysiological changes associated with hypertensive retinopathy are usually classified as vasoconstrictive, sclerotic, exudative, and malignant phases in response to elevated BP [22, 23]. However, animal models of hypertension and histopathological studies [24, 25] have shown that, prior to changes in the macrostructure of the retina, elevated BP leads to impaired NO function in endothelial cells and decreased microvascular resistance, which may subsequently lead to excessive capillary perfusion and oxidative stress impairment of microvessels. In the present study, to the best of our knowledge, five main pathological changes of hypertensive retinopathy were first identified by OCTA, including focal capillary sparsity, scattered microangioma, focal macular arch ring defects, focal capillary disorder and focal capillary nonperfusion. The early pathological changes in grade I hypertensive retinopathy eyes were deep focal retinal capillary sparsity with corresponding superficial and deep focal retinal arch defects. In grade II hypertensive retinopathy eyes, scattered microangiomas of the superficial and deep retina began to appear. In grade III hypertensive retinopathy eyes, focal retinal capillary disorders (18.3%) and capillary nonperfusion (25.0%) were found in the superficial and deep retina. Moreover, as hypertensive retinopathy worsened, the number of lesions increased. Therefore, according to the results of OCTA, we speculate that the pathophysiological process of hypertensive retinopathy is as follows: with elevated BP, a small number of capillaries are first subjected to oxidative injury and occlusion, resulting in focal retinal capillary sparsity, and then sustained elevated BP leads to retinal microvascular wall injury and tumor dilatation, resulting in retinal microangioma-like changes. With retinal microvascular injury, the distribution of microvessels in the lesion area is irregular, resulting in retinal microvascular disorder. Finally, focal microvascular complete occlusion leads to local capillary nonperfusion in the retina. Further longitudinal studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

As mentioned above, hypertensive retinopathy is generally considered to be a predictor of vascular disease elsewhere in the human body [5, 6]. In the past few decades, a variety of grading systems have been proposed for hypertensive retinopathy [6, 8, 9, 11]. However, these grading systems have some limitations and a restricted scope of application. In contrast to previous studies, we propose 3 stages in hypertensive retinopathy without macular edema according to the pathophysiology found by OCTA (Table 4): stage 1 vs KWB grade I (only focal capillary sparsity), stage 2 vs KWB grade II (focal capillary sparsity and scattered microangioma), and stage 3 vs KWB grade III (focal capillary sparsity, scattered microangioma, focal capillary disorder and nonperfusion). Compared to previous grading systems, our staging system has the following advantages. First, in contrast to the previous grading systems, all microvascular lesions are observed in a uniform standard 3 × 3-mm macular area, which is more comparable; second, the macula is one of the most metabolically active tissues of the body with a unique microanatomy that represents the area of sharpest visual acuity [26, 27]; third, OCTA microvascular lesions can be quantitatively assessed in combination with vascular density; fourth, since the microvascular lesions of OCTA in the macular area are very clear and distinguishable (Fig. 1), this system will be easy to promote among cardiologists and general practitioners; fifth, because OCTA classification is based on microvascular morphology, it may have a better correlation with target organ microvascular lesions elsewhere in the body and can better predict their pathological changes. In this study, since the involvement of the retina in hypertension is similar to blood vessel damage in the kidneys, we mainly evaluated the correlation between retinal and renal injury in patients with hypertension. Similar to previous studies [28, 29], we found that the associations of staging of hypertensive retinopathy using OCTA and renal damage were significant in this study subjects; finally, the most important is that the IRR of OCTA classification was better than that of KWB in this study.

The foveal avascular zone area is a capillary-free zone in the macular center, and its size is of great significance for the diagnosis and treatment of various fundus diseases [12, 15, 30]. Lee et al. reported that the superficial foveal avascular zone area in hypertensive patients was significantly increased compared to that of normal control eyes [18]. Lim et al. revealed that the foveal avascular zone area of hypertensive patients with a history of more than 5 years was larger than that of the control group after excluding abnormal fundus findings [17]. However, Dogan et al. showed that enlargement was found either in the superficial or deep foveal avascular zone area in malignant hypertensive retinopathy after 6 months of follow-up [31]. In our study, compared with the control eye, the foveal avascular zon area tended to increase in grade I hypertensive retinopathy and then decreased with the increase in hypertensive retinopathy severity. Similar to the above previous studies [17, 18], retinal microvascular damage may occur in the early stage of hypertension.

In the present study, which was consistent with previous studies [18, 32, 33], central macular thickness was statistically thinner in hypertensive retinopathy eyes than in controls, especially in grade I hypertensive retinopathy eyes. These results suggest that early chronic ischemic damage caused by a retinal blood circulation disorder may have contributed to changes in retinal microstructures in hypertensive retinopathy [33].

OCTA can be used not only to measure the morphological changes of the retinal microvascular network in the macular area but also to analyze the retinal capillary network quantitatively by using the parameters vessel density and perfusion density of itself. Our study found that vessel density and perfusion density tended to decrease as the hypertensive retinopathy stage worsened. After adjusting for the related confounding factors, only deep vessel density was significantly related to hypertensive retinopathy risk in OCTA parameters. This finding indicates that only deep vessel density is an independent risk factor for hypertensive retinopathy and can be defined as a marker for the prediction of hypertensive retinopathy. There have been many reports about retinal microvascular changes caused by hypertension, which play an important role in predicting the risk of vascular disease elsewhere in the body, including the heart, brain and kidney [4, 6, 34]. However, there was not a standardized tool yet for quantitative assessment of hypertensive retinopathy retinal microvascular changes before OCTA [17, 18]. Deep vessel density may act as a surrogate marker of retinal microcirculation to assess the risk of vascular disease elsewhere in hypertensive patients. Further longitudinal prospective studies are needed to address this issue.

Logistic regression analysis also showed that deep vessel density was the parameter most significantly related to hypertensive retinopathy risk after adjusting for the related confounding factors (P < 0.001). Based on ROC analyses, the AUC (95% CI) of deep vessel density was also the largest in a single index, and there was no significant difference compared with the combined index. Therefore, deep vessel density may be the most sensitive and best indicator to predict the risk of hypertensive retinopathy in this study. We speculate that the deep retinal capillary network is particularly vulnerable to ischemia and oxidative damage [35,36,37].

The potential limitations of the present study should also be mentioned. First, there was a bias in the clinical selection of subjects since this was a hospital-based cross-sectional study. In addition, we did not evaluate the association of these macular microvascular abnormalities and parameters of OCTA with visual acuity. Further research is needed to elucidate these issues.

Conclusion

There were five main pathological changes in hypertensive retinopathy: focal capillary sparsity, scattered microangioma, focal macular arch ring defect, focal capillary disorder, and focal capillary nonperfusion at the level of the superficial and deep vascular networks. In addition, the number of these various pathological changes showed an increasing trend as the stage of hypertensive retinopathy progressed, and deep vessel density could be the best indicator to predict the risk of hypertensive retinopathy. The results suggest that OCTA is a potentially useful tool for evaluating the pathophysiology and staging of hypertensive retinopathy.

References

Li D, Lv J, Liu F, Liu P, Yang X, Feng Y, et al. Hypertension burden and control in mainland China: analysis of nationwide data 2003-2012. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:637–44.

Li Z, Fu C, Yang F, Mao Z. Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension for the middle-aged population in China—results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (charls). Clin Exp Hypertens. 2019;41:80–86.

Lu J, Lu Y, Wang X, Li X, Linderman GC, Wu C, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from 1.7 million adults in a population-based screening study (China peace million persons project). Lancet. 2017;390:2549–58.

Kolman SA, van Sijl AM, van der Sluijs FA, van de Ree MA. Consideration of hypertensive retinopathy as an important end-organ damage in patients with hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2017;31:121–5.

Schmieder RE. Hypertensive retinopathy: a window to vascular remodeling in arterial hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;51:43–44.

Fraser-Bell S, Symes R, Vaze A. Hypertensive eye disease: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;45:45–53.

Harjasouliha A, Raiji V, Garcia, Gonzalez JM. Review of hypertensive retinopathy. Dis-a-Mon: DM. 2017;63:63–69.

Konstantinidis L, Guex-Crosier Y. Hypertension and the eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27:514–21.

Aissopou EK, Papathanassiou M, Nasothimiou EG, Konstantonis GD, Tentolouris N, Theodossiadis PG, et al. The Keith-Wagener-Barker and mitchell-wong grading systems for hypertensive retinopathy: association with target organ damage in individuals below 55 years. J Hypertens. 2015;33:2303–9.

Keith NM, Wagener HP, Barker NW. Some different types of essential hypertension: their course and prognosis. Am J Med Sci. 1974;268:336–45.

Ahn SJ, Woo SJ, Park KH. Retinal and choroidal changes with severe hypertension and their association with visual outcome. Investigative Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:7775–85.

Kashani AH, Chen CL, Gahm JK, Zheng F, Richter GM, Rosenfeld PJ, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography: a comprehensive review of current methods and clinical applications. Prog Retinal Eye Res. 2017;60:66–100.

Ang M, Tan ACS, Cheung CMG, Keane PA, Dolz-Marco R, Sng CCA, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography: a review of current and future clinical applications. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256:237–45.

Samara WA, Shahlaee A, Adam MK, Khan MA, Chiang A, Maguire JI, et al. Quantification of diabetic macular ischemia using optical coherence tomography angiography and its relationship with visual acuity. Ophthalmology 2017;124:235–44.

Balaratnasingam C, Inoue M, Ahn S, McCann J, Dhrami-Gavazi E, Yannuzzi LA, et al. Visual acuity is correlated with the area of the foveal avascular zone in diabetic retinopathy and retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2352–67.

Spaide RF, Klancnik JM Jr., Cooney MJ. Retinal vascular layers imaged by fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography angiography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:45–50.

Lim HB, Lee MW, Park JH, Kim K, Jo YJ, Kim JY. Changes in ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness and retinal microvasculature in hypertension: an optical coherence tomography angiography study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;199:167–76.

Lee WH, Park JH, Won Y, Lee MW, Shin YI, Jo YJ, et al. Retinal microvascular change in hypertension as measured by optical coherence tomography angiography. Sci Rep. 2019;9:156.

Liu LS. Writing Group of Chinese Guidelines for the Management of H. [2010 chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension]. Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi. 2011;39:579–615.

Pilotto E, Frizziero L, Crepaldi A, Della Dora E, Deganello D, Longhin E, et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of foveal avascular zone area measurement on normal eyes by different optical coherence tomography angiography instruments. Ophthalmic Res. 2018;59:206–11.

Penno G, Solini A, Zoppini G, Orsi E, Zerbini G, Trevisan R, et al. Cardiovascular Events Study G. Rate and determinants of association between advanced retinopathy and chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: The renal insufficiency and cardiovascular events (riace) italian multicenter study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2317–23.

Tso MO, Jampol LM. Pathophysiology of hypertensive retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1132–45.

Wong TY, Mitchell P. Hypertensive retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2310–7.

Tsai SH, Xie W, Zhao M, Rosa RH Jr, Hein TW, Kuo L. Alterations of ocular hemodynamics impair ophthalmic vascular and neuroretinal function. Am J Pathol. 2018;188:818–27.

Reichhart N, Haase N, Crespo-Garcia S, Skosyrski S, Herrspiegel C, Kociok N, et al. Hypertensive retinopathy in a transgenic angiotensin-based model. Clin Sci. 2016;130:1075–88.

Yu DY, Yu PK, Cringle SJ, Kang MH, Su EN. Functional and morphological characteristics of the retinal and choroidal vasculature. Prog Retinal Eye Res. 2014;40:53–93.

Yu DY, Cringle SJ, Su EN. Intraretinal oxygen distribution in the monkey retina and the response to systemic hyperoxia. Investigative Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4728–33.

Takayama K, Kaneko H, Ito Y, Kataoka K, Iwase T, Yasuma T, et al. Novel classification of early-stage systemic hypertensive changes in human retina based on octa measurement of choriocapillaris. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15163.

Chua J, Chin CWL, Hong J, Chee ML, Le TT, Ting DSW, et al. Impact of hypertension on retinal capillary microvasculature using optical coherence tomographic angiography. J Hypertens. 2019;37:572–80.

Kumagai K, Furukawa M, Suetsugu T, Ogino N. Foveal avascular zone area after internal limiting membrane peeling for epiretinal membrane and macular hole compared with that of fellow eyes and healthy controls. Retina. 2018;38:1786–94.

Dogan B, Akidan M, Erol MK, Coban DT, Suren E. Optical coherence tomography angiography findings in malignant hypertensive retinopathy. Arquivos brasileiros de oftalmologia. 2019;82:72–77.

Lee HM, Lee WH, Kim KN, Jo YJ, Kim JY. Changes in thickness of central macula and retinal nerve fibre layer in severe hypertensive retinopathy: a 1-year longitudinal study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:e386–92.

Lee SH, Lee WH, Lim HB, Jo YJ, Kim JY Thicknesses of central macular, retinal nerve fiber, and ganglion cell inner plexiform layers in patients with hypertension. Retina. 2018.

Downie LE, Hodgson LA, Dsylva C, McIntosh RL, Rogers SL, Connell P, et al. Hypertensive retinopathy: comparing the Keith-Wagener-Barker to a simplified classification. J Hypertens. 2013;31:960–5.

Wangsa-Wirawan ND, Linsenmeier RA. Retinal oxygen: fundamental and clinical aspects. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:547–57.

Birol G, Wang S, Budzynski E, Wangsa-Wirawan ND, Linsenmeier RA. Oxygen distribution and consumption in the macaque retina. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1696–704.

Wakabayashi T, Sato T, Hara-Ueno C, Fukushima Y, Sayanagi K, Shiraki N, et al. Retinal microvasculature and visual acuity in eyes with branch retinal vein occlusion: Imaging analysis by optical coherence tomography angiography. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:2087–94.

Funding

This research was supported by the Wenzhou Science & Technology Bureau under Grant No. Y20190631 (to YL) and No. Y20180168 (ZJ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Li, J., Pan, J. et al. Morphological changes in and quantitative analysis of macular retinal microvasculature by optical coherence tomography angiography in hypertensive retinopathy. Hypertens Res 44, 325–336 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00583-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00583-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluating the effect of systemic hypertension on retinal, optic nerve head microvasculature and field of vision using optical coherence tomography angiography and visual field analyzer

BMC Ophthalmology (2025)

-

SS-OCTA assessment of fundus microvascular changes and their correlation with coronary lesion severity in severe coronary heart disease

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Hypertensive eye disease

Nature Reviews Disease Primers (2022)

-

Quantifying the pattern of retinal vascular orientation in diabetic retinopathy using optical coherence tomography angiography

Scientific Reports (2021)