Abstract

The current study aimed to explore the association between carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) and cognitive function assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and to examine possible effect modifiers in hypertensive patients. A total of 14,322 hypertensive participants (mean age 64.2 ± 7.4 years; 40.9% male) from the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT) were included in the final analysis. CIMT was measured by ultrasound, and data were collected at the last follow-up visit; MMSE was used to evaluate cognitive function. Nonparametric smoothing plots, multivariate linear regression analysis, subgroup analyses and interaction testing were performed to examine the relationship between the CIMI and cognitive function and effect modification. The mean CIMT was 0.74 ± 0.11 mm, and the mean MMSE score was 23.5 ± 4.8. There was a significant interaction (P interaction < 0.05) in both male and female populations stratified by age (<60 vs. ≥60 years), and higher CIMT was significantly associated with decreased MMSE scores only in participants aged ≥60 years (male: β = −2.29, 95% CI −3.23 to −1.36; female: β = −1.96, 95% CI −2.97 to −0.95). Males with abnormal HDL-C showed a stronger negative association (β = −3.16, 95% CI −4.85 to −1.47) than those with normal HDL-C (normal vs. abnormal, P for interaction = 0.004). We observed that increased CIMT was significantly associated with cognitive impairment in the hypertensive population, especially among individuals with an age greater than 60 years and HDL-C deficiency. Overall, upon diagnosis of hypertension, treatment should start at the earliest opportunity to prevent end-organ damage and cognitive decline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerebrovascular diseases and cognitive dysfunction are both global health concerns, and these burdens are expected to increase with population aging [1]. The World Alzheimer’s Disease 2015 report shows that the number of people with dementia in Asia is as high as 22.9 million, and this number continues to increase over time [2].

It was reported that the global prevalence of increased carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) in people aged 30–79 years in 2020 is estimated to be 27.6%, indicating that ~1667 million people are affected (an increase of 57.46% compared with 2000) [3]. Carotid intima-media thickening reflects different severities of the atherosclerotic process [4]. Previous studies have shown inconsistent results regarding whether increased CIMT was associated with cognitive impairment [5,6,7]. Most studies on CIMT and cognitive impairment have been conducted in Western countries, but research in Asian populations is sparse.

Previous studies have also shown a positive relationship between hypertension and cognitive impairment [8], Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [9], and vascular dementia. Of note, the possible effect modifiers for the CIMT-cognitive impairment relationship have not been fully investigated. The current study aimed to explore the association between CIMT and cognitive impairment and examine possible effect modifiers among Chinese hypertensive patients.

Methods

Our article adheres to the American Heart Association Journals’ implementation of the Transparency and Openness Promotion Guidelines. The China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT) was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Biomedicine, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China (FWA assurance number: FWA00001263) and registered with Clinical Trials.gov (NCT00794885). All participants provided written informed consent. The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First People’s Hospital of Lianyungang, and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and the lack of participant interaction.

Participants

All data were obtained from the CSPPT study. Details regarding the inclusion/exclusion criteria, treatment assignments and outcome measures of the trial have been thoroughly described elsewhere [10,11,12]. Briefly, the CSPPT was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial conducted from May 19, 2008, to August 24, 2013, in 32 communities in Jiangsu (20 communities) and Anhui (12 communities) provinces with 20,702 hypertensive adults who were randomly assigned to 2 double-blind treatment groups: 10-mg enalapril+0.8-mg folic acid or 10-mg enalapril, daily.

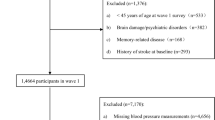

In this cross-sectional analysis of the CSPPT, we included 15,924 hypertensive individuals, with data on exit carotid artery ultrasonography in 2013, as well as MMSE score. After excluding subjects who did not finish the 30 questions for MMSE (n = 779) and with new-onset stroke or dementia (n = 383), and 3% of the participants with extreme value scores (MMSE scores ≤ 11) (n = 440), a total of 14,322 hypertensive subjects were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Smoothing curves of the association between carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) and MMSE; (a): male (b): female; adjusted for age, education, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T genotype, smoking status, alcohol consumption, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, total homocysteine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, total homocysteine, treatment group and research center

Assessment of MMSE

Cognitive assessment was conducted using the Chinese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) at the final follow-up visit. The Chinese version of the MMSE has been widely used as a reliable and standardized tool to screen cognitive impairment and dementia [13, 14]. The MMSE is a 30-point questionnaire that estimates the severity of cognitive impairment and can allow for the documentation of serial cognitive changes. The MMSE is often used in community epidemiological studies to assess participants’ current mental function. It examines functions including registration (repeating named prompts), attention and calculation, recall, language, ability to follow simple commands, and orientation [15].

Assessment of CIMT

Carotid artery ultrasonography was performed in 2013 by using a Terason 3000 with an ultrasound scanner equipped with a 12L5A linear-array transducer. Participants were asked to lie on the scanner bed in a supine position with their head resting comfortably and rotate their neck in the direction opposite to the probe at a 45-degree angle. CIMT was measured by certified sonographers with an MIA-Carotid Analyzer 6.0, which allows for semiautomatic edge detection of the echogenic lines of the intima-media complex, from the far walls of the right and left mean CCA when lumen diameter was minimal on multiple cycles of images. The measured segment of interest was 10 mm in length in CCA near the bulb and free of plaques.

The interobserver and intraobserver reliability tests of the CIMT value were reported by another post hoc analysis of CSPPT [16]. In brief, carotid artery ultrasound was performed by 3 observers (1 physician and 2 technicians) who received training prior to the start of the study. Fifty individuals from the entire study population were randomly sampled. Each observer performed the measurements independently at least 4 weeks later, and all measurements were repeated by the 3 observers. According to the Bland–Altman analysis, the average difference in interobserver agreement (95% limits of agreement) was 0.003 (95% CI − 0.113 to 0.122) mm and in intraobserver agreement was 0.049 (95% CI − 0.196 to 0.286) mm [16].

Laboratory tests and clinical data collection

Fasting blood samples were collected from all follow-up patients. Serum total homocysteine (tHcy), total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), fasting blood glucose (FBG), and serum creatinine levels were measured by automatic clinical analyzers (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) at the National Clinical Research Center for Kidney Disease, Nanfang Hospital, Guangzhou. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated with serum creatinine using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. MTHFR C677T (rs1801133) polymorphisms were detected on an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Life Technologies) using the TaqMan assay. Serum folate and vitamin B12 were measured by a commercial laboratory (New Industrial).

A standardized physical examination and accurate medical history were available for all participants. Height and weight were obtained using standard operating procedures. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight (in kilograms) divided by the squared height. Self-reported smoking and alcohol consumption statuses were recorded, which were coded into three categories: current, former, or never.

Blood pressure was recorded by trained medical staff after the subjects had been seated for 10 minutes. Triplicate measurements on the same arm were taken with at least a 2-min break between readings.

Statistical analysis

The population characteristics are described according to sex. N (%) is used to describe categorical variables, and the mean ± SD is used to describe continuous variables. Characteristics of all participants were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test for categorical variables. Variables known as traditional or suspected risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis or those showing significant differences across cognitive impairment levels were selected as covariates. Two models were constructed. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, and education. The following additional adjustments were performed in Model 2: BMI, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), lipids [total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-C], MTHFR C677T genotype, tHcy, FBG, smoking status, alcohol consumption, folic acid treatment, and research center. Generalized additive regression models and smoothing curves (penalized spline method) were used in the fully adjusted model to estimate the relationship between CIMT and MMSE scores. We performed a multivariate linear regression analysis of CIMT and MMSE in the adjusted model for male and female patients with hypertension, respectively. Next, stratified analyses of potential covariates, including age (<60 vs. ≥60 years), total cholesterol (<5.2 mmol/L vs. ≥5.2 mmol/L), HDL-C [abnormal versus normal: male HDL-C ≥ 1.04 mmol/L, female HDL-C ≥ 1.3 mmol/L] [17], tHcy (median, <12 μmol/L vs. ≥12 μmol/L), and education (illiterate vs. primary vs. secondary and above), were performed in male and female populations.

All tests were two sided, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using EmpowerStats (www.empowerstats.com; X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, MA) and the statistical software package R (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

As shown in the flow chart (Supplementary Fig. 1), 14,322 hypertensive patients with a mean age of 64.2 ± 7.4 years and among whom 40.9% (5854) were male were included in this analysis. The mean BMI of those participants was 25.0 ± 3.8 kg/m2, and the mean CIMT and MMSE scores were 0.74 ± 0.11 mm and 23.5 ± 4.8, respectively. Participant characteristics for all subjects and by sex are listed in Table 1. Compared with females, males were older; had lower BMI, SBP, total cholesterol, triglycerides and eGFR; were more likely to have received longer-term education; and had higher tHcy, current smoking and alcohol consumption rates. No significant difference was found between males and females in terms of FBG, MTHFR C677T genotype or treatment group.

Association between CIMT and MMSE

Overall, in the multivariate regression models, there was a significant negative association between the mean CIMT and MMSE in males (β: −1.26, 95% CI: −2.05, −0.47, P = 0.002) but not in females (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Consistently, when CIMT was assessed in quartiles, the adjusted β values for participants in the third and fourth quartiles were −0.31 (95% CI: −0.56, −0.05) and −0.46 (95% CI: −0.72, −0.19), respectively. However, a significant association was no longer observed in females.

Subgroup analysis

Stratified analysis of potential covariates was conducted in male and female populations. There was a significant interaction (P for interaction < 0.05) of subgroups stratified by age <60 vs. ≥60 years. A significant association of CIMT with MMSE was found among participants, both male and female, among those aged 60 years and above [male: β = −2.29, 95% CI −3.23 to −1.36, P < 0.001; female: β = −1.96, 95% CI −2.97 to −0.95, P < 0.001] (Table 3), while no significant association was found among those aged <60 years. In addition, males with abnormal HDL-C showed a stronger negative association (β = −3.16, 95% CI −4.85 to −1.47, P < 0.001) than those with normal HDL-C (normal vs. abnormal, P for interaction = 0.004) (Fig. 2). Further subgroup analysis defined by potential covariates was performed in males and females stratified by age of 60 years. There were no significant interactions in most subgroups (P for interaction > 0.05), except that HDL-C did appear to interact with the association of CIMT with MMSE in males aged 60 years and above (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Subgroup analyses of the association between MMSE score and carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) in males (a) and females (b). The multivariate model was adjusted for age, education, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T genotype, smoking status, alcohol consumption, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, total homocysteine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, total homocysteine, treatment group and research center, with the exception of the variable that was stratified

Discussion

Our study explored the modification effect of age on the association between CIMT and MMSE scores in both male and female hypertensive populations. CIMT was significantly and negatively associated with MMSE in people aged ≥60 years but not in those aged <60 years. Notably, abnormal HDL-C could improve the negative correlation between CIMT and MMSE in males aged ≥60 years.

Previous studies frequently suggested that thickened CIMT was inversely associated with cognitive impairment and dementia [5, 6, 18,19,20], but exceptions have been seen as well. A cross-sectional study based on the Heinz Nixdorf Recall (HNR) cohort revealed that the ankle-brachial index, but not CIMT, was significantly associated with mild cognitive impairment [21]. The Northern Manhattan Study found that an inverse association of CIMT with cognition existed only among people at higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease [22]. Our study, which focused on Chinese hypertensive adults, demonstrated a significant negative correlation between CIMT and cognitive function only in people aged 60 and older. The mechanism underlying the correlation between CIMT and cognitive function is still unclear. In the Framingham Offspring study, Romero et al. found an inverse association of carotid atherosclerosis with cognitive impairment performance in subjects without stroke, which was independent of structural brain changes [23]. It was suggested that the correlation between IMT thickening and cognitive impairment provides valuable information about vascular risk factors rather than directly reflecting cerebrovascular lesions [23]. A similar negative association of CIMT with cognitive function was reported in a dialysis population, but magnetic resonance imaging of the brain suggested that the impact of CIMT on global cognitive impairment was induced by brain atrophy, not by cardiovascular disease [24]. In animal research, the induction of increased carotid artery intima-media thickness and calcification caused arterial stiffening with a decrease in arterial compliance and dilatation, an increase in the production of cerebral superoxide anion, and neurodegeneration in the hippocampus, which is a key region involved in cognitive function [25].

Notably, the role of age in the relationship between CIMT and cognitive function has not been well recognized in previous studies. Most studies have focused on the association of CIMT with cognition in the elderly, but the results from studies involving the mid-life population are limited and inconsistent. Baseline data from the ELSA-Brasil study found that CIMT was associated with worse memory function in middle-aged adults without stroke [26]. A similar result was also found in The Beaver Dam Offspring Study (BOSS), which showed that CIMT was associated with the MMSE in the population aged 21–84 years after adjusting for multiple potential confounders [27], whereas another longitudinal study reported that CIMT was not a risk factor for cognitive decline among middle-aged adults in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Brain MRI cohort that included middle-aged participants (45–64 years) [28, 29]. In the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study of stroke-free middle-aged adults, higher IMT was not associated with performance on the verbal memory test, which is an important component of cognitive functioning [18]. A recent quantitative study conducted in 182 patients with AD revealed that the most involved cognitive components based on age were recalling language and space orientation [30], while CIMT in our analysis was significantly associated with worse performance on cognitive tests only in participants aged ≥60 years rather than in those aged <60 years. In addition to the direct impact of age factors on MMSE, the inconsistent conclusions might be attributed to the “threshold effect” in CIMT. Previous studies have demonstrated that the significant association of CIMT with cognitive function and dementia was only established in the top quartile [31], even quintile [32], of CIMT. In our study, the CIMT thickness in each of the quartile groups was more severe in participants aged ≥60 years, both for males and females, than in those aged <60 years. This result indicated that CIMT might need to reach a certain severity to obtain statistically predictive ability for cognitive impairment.

HDL-C levels were found to have a modifying effect on the relationship between CIMT and MMSE among males aged ≥60 years in the current study. The significant association of CIMT with MMSE was present in those with abnormal HDL-C. No significant interaction was found in females, but abnormal HDL-C showed a similar trend of a negative association. Wang et al. showed that plasma HDL-C levels were lower in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia than in healthy subjects [33]. HDL-C reduction had a high diagnostic value for Alzheimer’s disease (AUC = 0.731, P < 0.001) and vascular dementia (AUC = 0.800, P < 0.001) in the elderly population. Our study shows that abnormal HDL-C enhances the association of increased CIMT with cognitive impairment. This was demonstrated by epidemiological data showing that HDL-C levels were negatively associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease [34, 35]. It is widely accepted that HDL-C deficiency contributes to cognitive impairment by increasing the risk of atherosclerosis [36]. Moreover, as the predominant lipoprotein in the human brain, HDL-C can maintain cognitive function and delay the onset of dementia by preventing amyloid-β protein aggregation and polymerization [37, 38]. However, no evidence has supported that supplementation with HDL-C improves cognitive function. Thus, additional prospective trials and basic research are needed to confirm the mechanism by which HDL-C affects cognitive function and atherosclerosis.

There are several limitations that are worth mentioning in the current study. First, the sole use of the MMSE test to measure global cognitive function, as the main limitation of this study, may not be accurate enough to detect mild cognitive impairment (MCI). A meta-analysis including 149 studies with 49,000 participants comparing 11 screening tests for dementia indicated that the MMSE has limited performance in identifying MCI, whereas MoCA might be more preferable [39]. Nevertheless, the MoCA may have evident floor effects for participants with low education [40]. Thus, MoCA combined with MMSE may contribute to the persuasive power of our study. Second, given the limitations of our cross-sectional data obtained from the last follow-up of the CSPPT, which means that our participants were treated with strict drug interventions, the blood pressure control rate in CSPPT was well above the levels among general hypertensive patients in China [10, 41, 42]. Furthermore, no data of an unaffected control group could be analyzed. Thus, caution is required in generalizing to general hypertension populations. Third, the population that we analyzed was composed of hypertensive patients, and the above results may not be generalizable to other populations. However, as an essential risk factor for cognitive function, our analysis of hypertensive patients may have a more value than a study of the general population. Finally, participants in our study had a lower education level with a high illiteracy rate, especially among females, which may affect the sensitivity of cognitive assessment. Compared with other cognitive assessment scales, the MMSE has lower educational requirements for subjects [43]. In terms of statistical analysis, we analyzed males and females independently, which can reduce bias in the results caused by differences in education levels between males and females.

Conclusions

We observed that increased CIMT was associated with cognitive decline in the hypertensive population aged 60 years and over. HDL-C deficiency improved the negative association between CIMT and cognitive function in males aged ≥60 years. Although the current study had several limitations, our study undoubtedly suggested that attention should be given to carotid atherosclerosis in high-risk groups with older age and abnormal HDL-C. Overall, upon diagnosis of hypertension, treatment should start at the earliest opportunity to prevent end-organ damage and cognitive decline.

Change history

20 October 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-025-02371-0

References

Goh VH. Aging in Asia: a cultural, socio-economical and historical perspective. Aging Male. 2005;8:90–6.

Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali GC, Wu YT, Prina AM, Winblad B, et al. The worldwide costs of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:1–7.

Song P, Fang Z, Wang H, Cai Y, Rahimi K, Zhu Y, et al. Global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e721–e729.

Nezu T, Hosomi N, Aoki S, Matsumoto M. Carotid intima-media thickness for atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23:18–31.

Johnston SC, O’Meara ES, Manolio TA, Lefkowitz D, O’Leary DH, Goldstein S, et al. Cognitive impairment and decline are associated with carotid artery disease in patients without clinically evident cerebrovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:237–47.

van Oijen M, de Jong FJ, Witteman JC, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Atherosclerosis and risk for dementia. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:403–10.

Arntzen KA, Schirmer H, Johnsen SH, Wilsgaard T, Mathiesen EB. Carotid atherosclerosis predicts lower cognitive test results: a 7-year follow-up study of 4,371 stroke-free subjects - the Tromso study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;33:159–65.

Launer LJ, Masaki K, Petrovitch H, Foley D, Havlik RJ. The association between midlife blood pressure levels and late-life cognitive function. The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. JAMA. 1995;274:1846–51.

Freitag MH, Peila R, Masaki K, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, White LR, et al. Midlife pulse pressure and incidence of dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Stroke. 2006;37:33–7.

Huo Y, Li J, Qin X, Huang Y, Wang X, Gottesman RF, et al. Efficacy of folic acid therapy in primary prevention of stroke among adults with hypertension in China: the CSPPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:1325–35.

Huang X, Li Y, Li P, Li J, Bao H, Zhang Y, et al. Association between percent decline in serum total homocysteine and risk of first stroke. Neurology. 2017;89:2101–7.

Huang X, Qin X, Yang W, Liu L, Jiang C, Zhang X, et al. MTHFR Gene and Serum Folate Interaction on Serum Homocysteine Lowering: Prospect for Precision Folic Acid Treatment. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:679–85.

Xu G, Meyer JS, Huang Y, Du F, Chowdhury M, Quach M. Adapting mini-mental state examination for dementia screening among illiterate or minimally educated elderly Chinese. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:609–16.

Prince MJ, Acosta D, Castro-Costa E, Jackson J, Shaji KS. Packages of care for dementia in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000176.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Sun P, Liu L, Liu C, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Qin X, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness and the risk of first stroke in patients with hypertension. Stroke. 2020;51:379–86.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52.

Zeki Al Hazzouri A, Vittinghoff E, Sidney S, Reis JP, Jacobs DR Jr., Yaffe K. Intima-media thickness and cognitive function in stroke-free middle-aged adults: findings from the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Stroke. 2015;46:2190–6.

Wang A, Chen G, Su Z, Liu X, Yuan X, Jiang R, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness and cognitive function in a middle-aged and older adult community: a cross-sectional study. J Neurol. 2016;263:2097–104.

Lin HF, Huang LC, Chen CK, Juo SH, Chen CS. Carotid atherosclerosis among middle-aged individuals predicts cognition: A 10-year follow-up study. Atherosclerosis. 2020;314:27–32.

Weimar C, Winkler A, Dlugaj M, Lehmann N, Hennig F, Bauer M, et al. Ankle-brachial index but neither intima media thickness nor coronary artery calcification is associated with mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:433–42.

Gardener H, Caunca MR, Dong C, Cheung YK, Elkind MSV, Sacco RL, et al. Ultrasound markers of carotid atherosclerosis and cognition: The Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke. 2017;48:1855–61.

Romero JR, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Benjamin EJ, Polak JF, Vasan RS, et al. Carotid artery atherosclerosis, MRI indices of brain ischemia, aging, and cognitive impairment: the Framingham study. Stroke. 2009;40:1590–6.

Zheng K, Qian Y, Lin T, Han F, You H, Tao X, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness relative to cognitive impairment in dialysis patients, and their relationship with brain volume and cerebral small vessel disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2020;11:2040622320953352.

Sadekova N, Vallerand D, Guevara E, Lesage F, Girouard H. Carotid calcification in mice: a new model to study the effects of arterial stiffness on the brain. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000224.

Suemoto CK, Santos IS, Bittencourt MS, Pereira AC, Goulart AC, Rundek T, et al. Subclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis and performance on cognitive tests in middle-aged adults: Baseline results from the ELSA-Brasil. Atherosclerosis. 2015;243:510–5.

Zhong W, Cruickshanks KJ, Huang GH, Klein BE, Klein R, Nieto FJ, et al. Carotid atherosclerosis and cognitive function in midlife: the Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:330–3.

Knopman D, Boland LL, Mosley T, Howard G, Liao D, Szklo M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2001;56:42–8.

Knopman DS, Mosley TH, Catellier DJ, Coker LH. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Brain MRIS. Fourteen-year longitudinal study of vascular risk factors, APOE genotype, and cognition: the ARIC MRI Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:207–14.

Delpak A, Talebi M. On the impact of age, gender and educational level on cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease: a quantitative approach. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89:104090.

Frazier DT, Seider T, Bettcher BM, Mack WJ, Jastrzab L, Chao L, et al. The role of carotid intima-media thickness in predicting longitudinal cognitive function in an older adult cohort. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;38:441–7.

Wendell CR, Waldstein SR, Ferrucci L, O’Brien RJ, Strait JB, Zonderman AB. Carotid atherosclerosis and prospective risk of dementia. Stroke. 2012;43:3319–24.

Wang R, Chen Z, Fu Y, Wei X, Liao J, Liu X, et al. Plasma cystatin c and high-density lipoprotein are important biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: a cross-sectional study. Front Aging. Neurosci 2017;9:26.

Gordon DJ, Rifkind BM. High-density lipoprotein–the clinical implications of recent studies. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1311–6.

Feig JE, Hewing B, Smith JD, Hazen SL, Fisher EA. High-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis regression: evidence from preclinical and clinical studies. Circ Res. 2014;114:205–13.

Bahrami A, Barreto GE, Lombardi G, Pirro M, Sahebkar A. Emerging roles for high-density lipoproteins in neurodegenerative disorders. Biofactors. 2019;45:725–39.

Olesen OF, Dago L. High density lipoprotein inhibits assembly of amyloid beta-peptides into fibrils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:62–66.

Koudinov AR, Berezov TT, Kumar A, Koudinova NV. Alzheimer’s amyloid beta interaction with normal human plasma high density lipoprotein: association with apolipoprotein and lipids. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;270:75–84.

Tsoi KK, Chan JY, Hirai HW, Wong SY, Kwok TC. Cognitive tests to detect dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1450–8.

Zhu Y, Zhao S, Fan Z, Li Z, He F, Lin C, et al. Evaluation of the mini-mental state examination and the montreal cognitive assessment for predicting post-stroke cognitive impairment during the acute phase in chinese minor stroke patients. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:236.

Sheng CS, Liu M, Kang YY, Wei FF, Zhang L, Li GL, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in elderly Chinese. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:824–8.

Ma S, Yang L, Zhao M, Magnussen CG, Xi B. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control rates among Chinese adults, 1991–2015. J Hypertens. 2021;39:740–8.

Tavares-Junior JWL, de Souza ACC, Alves GS, Bonfadini JC, Siqueira-Neto JI, Braga-Neto P. Cognitive assessment tools for screening older adults with low levels of education: a critical review. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:878.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all participants for their contributions to the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT).

Funding

The study was supported by funding from the following: the Jiangxi Outstanding Person Foundation (grant number 20192BCBL23024); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81960074, 81730019); the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFE0205400, 2018ZX09739, 2018ZX09301034003); Key R&D Projects, Jiangxi (20203BBGL73173); and the Health Commission of Jiangxi Province Foundation (202130440).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Guo, L., Liu, L. et al. Effect of age stratification on the association between carotid intima-media thickness and cognitive impairment in Chinese hypertensive patients: new insight from the secondary analysis of the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT). Hypertens Res 44, 1505–1514 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00743-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00743-w