Abstract

A wide range of Cu(II)-catalyzed C–H activation reactions have been realized since 2006, however, whether a C–H metalation mechanism similar to Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H activation reaction is operating remains an open question. To address this question and ultimately develop ligand accelerated Cu(II)-catalyzed C–H activation reactions, realizing the enantioselective version and investigating the mechanism is critically important. With a modified chiral BINOL ligand, we report the first example of Cu-mediated enantioselective C–H activation reaction for the construction of planar chiral ferrocenes with high yields and stereoinduction. The key to the success of this reaction is the discovery of a ligand acceleration effect with the BINOL-based diol ligand in the directed Cu-catalyzed C–H alkynylation of ferrocene derivatives bearing an oxazoline-aniline directing group. This transformation is compatible with terminal aryl and alkyl alkynes, which are incompatible with Pd-catalyzed C–H activation reactions. This finding provides an invaluable mechanistic information in determining whether Cu(II) cleaves C–H bonds via CMD pathway in analogous manner to Pd(II) catalysts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the past decade, enantioselective C–H activation reactions via asymmetric metalation have emerged as a promising platform for asymmetric catalysis1,2,3,4. Significant progress has been made in this field with the development of catalytic systems using Pd(II)5,6,7, Pd(0)8,9,10,11,12, Rh(III)13,14,15,16, Rh(I)17, Ir18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, and other precious metals. In particular, a wide range of chiral Pd(II) catalysts have been developed for inducing point chirality, axial chirality, and planar chirality owing to the discovery of bifunctional chiral mono-N-protected amino acid (MPAA) ligands and next-generation ligands capable of accelerating C–H activation5,6,7. In contrast, there are few reports of asymmetric C–H activation using first-row transition metal catalysts, such as Fe, Co, Ni, or Cu, despite their abundance and low cost26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. For example, Cu-catalyzed C–H activation reactions have immense potential utility given the superior tolerance of Cu catalysts for heterocycles and other sensitive functionalities compared to precious metal catalysts34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. However, the development of enantioselective transformations has not been successful. The discovery of chiral ligands that accelerate Cu-catalyzed C–H activation is essential, as it enables the chiral ligand–catalyst complex to outcompete the racemic “background” reaction that is prevalent with unligated Cu. In addition, the establishment of a stereo model will provide unique insights into the transition state structures.

Given the aforementioned advantages of Cu-catalyzed C−H activation reactions, our group has devoted extensive effort to the development of Cu catalysis since the first report in 200634. We have developed diverse transformations using a wide range of coupling partners enabled by our class of practical oxazoline-aniline directing groups (DGs)46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Our oxazoline-aniline DG not only unlocks reactivity with an enormous range of coupling partners for C–H activation, including free amines/amides46 and trifluoromethylating reagents48 but also demonstrates exceptional tolerance for otherwise challenging functional groups, especially a broad range of heterocycles52,53.

In the realm of stereoselective Cu-catalyzed C−H activation, we recently reported the diastereoselective C–H thiolation of ferrocenes using a chiral oxazoline directing group (Fig. 1a)55. Despite its practical limitations, this chiral auxiliary approach represents a promising lead for the ultimate development of Cu-catalyzed enantioselective C−H activation reactions. Here, we report the discovery of BINOL-derived ligands that accelerate the Cu-mediated C–H alkynylation of ferrocenes with an oxazoline-amide directing group. When using (S)−6,6’-dibromo-BINOL as the chiral ligand, the Cu-mediated enantioselective C–H alkynylation of ferrocene carboxylic acid derivatives was achieved with high enantioselectivity (Fig. 1b). Mechanistic studies support the presence of ligand acceleration and indicate the acceleration occurs at the key C–H cleavage step of the catalytic cycle.

Results and discussion

Reaction optimization for Cu-mediated C–H alkynylation

We targeted the ortho-C(sp2)–H activation of planar chiral ferrocene carboxylic acid derivatives as the model system to develop ligands to accelerate C–H activation with Cu. We derivatized the carboxylic acid with our oxazoline-amide directing group as it promotes a range of transformations and is readily installed and removed46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Achieving ligand acceleration could enable the development of asymmetric Cu-catalyzed C–H activations. A number of catalytic asymmetric C–H activations of ferrocenes using other metals have been reported18,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65.

Planar chiral ferrocenes are prevalent in synthetic chemistry, materials science, and medicinal chemistry66,67,68,69, as well as privileged scaffolds for chiral ligands and catalysts70,71,72,73,74,75. More specifically, ortho-substituted planar chiral ferrocene carboxylic acids and their derivatives, the products of this method, are highly valuable in the preparation of chiral monodentate (carboxylates)76 and bidentate (oxazolines/phosphines, etc.)77 ligands. Traditional directed ortho lithiation approaches for the enantioselective preparation of ortho-substituted ferrocene carboxylic acids rely on chiral auxiliaries78,79,80,81,82. They suffer from efficiency and atom economy losses associated with the use of chiral auxiliaries, as well as the scope limitations associated with organolithium reagents. A Cu-catalyzed enantioselective C–H activation approach towards ortho-substituted planar ferrocene carboxylic acid derivatives would circumvent these limitations and permit direct installation of diverse functionality using an abundant base metal catalyst. Notably, very few enantioselective catalytic C–H activation reactions to prepare ortho-substituted ferrocene carboxylic acid derivatives are known83.

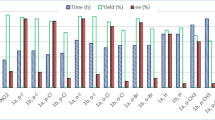

Preliminary experiments with the racemic Cu-mediated C–H alkynylation of ferrocene carboxylic acid substrate 1 with ethynylbenzene (2a) provided only 14% yield of product 3a under our previously developed conditions for Cu-mediated C–H alkynylation, which did not use an exogenous ligand36. Through a systematic evaluation of reaction parameters, the yield of 3a was improved to 56% (17/1.0 mono/di). Encouraged by our success in developing ligands capable of accelerating Pd-catalyzed C−H activation, we then initiated a search for ligand acceleration effects for this Cu-mediated transformation. A range of ligand scaffolds were systematically investigated (Fig. 2, see Supplementary Information for more details). Common mono- and bi-dentate donating ligands such as triphenylphosphine (L1), BINAP (L2), 1,10-phenanthroline (L3), and bis-oxazoline (L4) either inhibited or showed no beneficial impact on reactivity. We next evaluated mono-protected amino acid (L5) and pyridone (L6) ligands, two scaffolds widely used in Pd-catalyzed C−H activation and capable of directly accelerating the key C−H activation step. Unfortunately, both ligand classes were ineffective in this transformation. Pyridine-type (L7) ligands, which are also widely used to improve the reactivity of Pd C−H activation catalysts, failed to show any improvement. Finally, mono-oxazoline ligands (L8), which are effective ligands in Cu-mediated C−H activations with monodentate directing groups43, were not beneficial in this transformation.

Reaction conditions: 1 (37.4 mg, 0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 2a (27.5 μL, 0.25 mmol), CuOAc (18.4 mg, 0.15 mmol), Ligand (40 mol%), NaOAc (8.2 mg, 0.1 mmol), DMSO (5.0 mL), 70 °C, air, 12 h. The yield was determined using tetrachloroethane as the internal standard, and the ratio of mono/di was determined by analysis of the crude 1H NMR. The data in the bracket indicates the isolated yield.

In contrast to the results with established ligands for Pd-catalyzed C−H activations, we found that (S)-BINOL (L10) showed a significant improvement in reactivity, increasing the yield of 3a to 69% and indicating the potential for ligand accelerated catalysis84. Other bisphenol scaffolds such as L9 and (S)-spirosilabiindane diol (SPSiOL, L12)85 showed inferior results, while (S)-spirobiindane diol (SPINOL, L11) demonstrated similar reactivity as L10. Given the established modularity and ease of derivatization of the BINOL core, we chose the BINOL platform for further investigation. We first evaluated 3,3’-Me2-BINOL (L15), which to our delight gave an improved yield of 76% (4.8/1 mono/di). Control experiments revealed that both phenolic hydroxyl groups are crucial for the high reactivity (L13, L14 vs. L10). The observation of this potential ligand acceleration effect with Cu not only will promote the discovery of Cu-mediated/catalyzed C−H activations with this abundant and economical metal but also enable the development of enantioselective catalysis (vide infra).

Substrate scope for the Cu-mediated C–H alkynylation

With the optimal conditions in hand, the scope of the ligand-accelerated Cu-mediated C–H alkynylation was investigated. Employing ferrocene monocarboxylic acid-derived 1 as the model substrate, we first evaluated the breadth of terminal alkynes (Fig. 3). In general, this method could tolerate a series of aryl, alkenyl, and alkyl-substituted terminal alkynes, providing the desired products in moderate to good yields (3a–r). Both electron-rich (2b–d, 2g, 2i) and electron-deficient (2e, 2f, 2h, 2j) substituents on the phenyl group of phenylacetylenes are compatible with this protocol. To our delight, terminal alkyne 2l bearing a heterocyclic thiophene moiety was also compatible, providing product 3l in 64% yield. Notably, aliphatic alkynes containing both cyclic (2m, 2n) and acyclic (2o–q) alkyl groups, were all compatible, giving products 3m–q in good yields. Conjugated enyne 2r gave the ferrocene-containing enyne 3r in 62% yield, further demonstrating the generality of this protocol.

Reaction conditions: 1 (37.4 mg, 0.1 mmol), 2 (0.25 mmol, 2.5 equiv), CuOAc (18.4 mg, 0.15 mmol), L15 (12.6 mg, 40 mol%), NaOAc (8.2 mg, 0.1 mmol), DMSO (5.0 mL), 70 °C, air, 12 h. Isolated yield and the ratio of mono/di were determined by analysis of the crude 1H NMR. For 3f, the reaction was conducted for 16 h.

Next, the scope of ferrocene substrates was evaluated with phenylacetylene (2a) as the alkynylating reagent (5a–i), as presented in Fig. 4. Ferrocenes bearing both electron-deficient ketone and ester groups (4a–e) and electron-rich alkyl (4f–h) substituents on the lower cyclopentadiene ring were all tolerated, affording the corresponding alkynylated ferrocene derivatives in moderate to good yields. Bulky ferrocene 4i bearing a Cp* on the lower ring gave a lower yield (38%) with excellent mono selectivity, potentially due to steric hindrance.

Reaction optimization for Cu-mediated asymmetric C–H alkynylation

Encouraged by the potential ligand acceleration effect in Cu-mediated C–H activation with BINOL ligands, we hypothesized that an asymmetric Cu-mediated C–H alkynylation of ferrocenes could be achieved with enantioenriched chiral diol ligands. This method would enable the enantioselective preparation of useful planar chiral ferrocene scaffolds. Ligand acceleration of the catalytic cycle is particularly critical for asymmetric Cu C–H activation catalysis, in light of the prominent achiral “background” reaction often observed with Cu. Upon evaluating enantiopure BINOL ligands in our racemic reaction protocol, we obtained a promising initial hit with (S)-BINOL ((S)-L10) providing product 3a in 78.5:21.5 er. Additional optimization of reaction parameters to a mixture of CuOAc (50 mol%) and Cu(OAc)2 (70 mol%) as the Cu sources and 60 mol% of (S)-L10 ligand, as well as the use of Ag2CO3 (0.5 equiv) and NaOAc (1.0 equiv) improved the enantioselectivity to 82:18 er in 63% yield (6.0/1.0 mono/di) (Fig. 5). Next, ligand effects were explored. (S)-H8-BINOL (L16) led to 54:46 er, while (S)-SPINOL (L11) and (R,R)-TADDOL (L17) gave the racemic product. Although (S)−3,3’-Me2-BINOL (L15) showed superior reactivity under the racemic reaction conditions, it only provided the product at 55:45 er. The installation of other substituents at the 3,3’-positions of BINOL (L18–20) generally resulted in inferior selectivity to L10, although results with L19 and L20 (70:30 er, 74:26 er, respectively) suggested that electron-withdrawing groups could benefit asymmetric induction by rendering the phenolic groups more acidic. Following this reasoning, we then evaluated (S)−6,6’-Br2-BINOL [(S)-L21], with distal Br substituents capable of acidifying the phenolic groups without steric interference. Gratifyingly, these changes improved stereocontrol to 87:13 er. Phenyl substituents at the 6,6’-positions provided inferior results (L22, 72:28 er). Control experiments with enantioenriched mono-((S)-L13) and di-((S)-L14) protected BINOL ligands showed that both hydroxyl groups are essential for selectivity and reactivity.

Reaction conditions: 1 (37.4 mg, 0.1 mmol), 2a (33.0 μL, 0.30 mmol), CuOAc (6.1 mg, 50 mol%), chiral diol ligand (50 mol%), Cu(OAc)2 (12.7 mg, 0.07 mmol), NaOAc (8.2 mg, 0.1 mmol), DMSO (5.0 mL), 60 °C, air, 12 h. Isolated yield and the ratio of mono/di were determined by analysis of the crude 1H NMR. The er value for the mono-alkynylated product was determined by chiral HPLC.

Substrate scope for the asymmetric C–H alkynylation

With (S)−6,6’-dibromo-BINOL [(S)-L21] as the optimal ligand, the enantioselectivity was further improved to 92.5:7.5 by reducing the loading of CuOAc/[(S)-L21] and lowering the reaction temperature. The absolute configuration of the planar chiral alkynylated ferrocene was determined by X-ray crystallography of (Rp)-3a. This novel process features broad substrate scope with respect to the terminal alkynes (3a–r, Fig. 6). Both substituted phenylacetylenes and alkyl-substituted acetylenes are suitable substrates, delivering the enantioenriched mono-alkynylated ferrocenes in synthetic useful yields (35–68% yields) with good enantioselectivities (88:12 er to 93:7 er). The mono/di selectivity is lower than the racemic reaction (Figs. 3 and 4), probably due to the higher reactivity of (S)−6,6’-dibromo-BINOL [(S)-L21] in comparison with 3,3’-Me2-BINOL (L15). Notably, heterocyclic arylalkynes containing thiophene (2l) also proceeded in high enantioselectivity (89.5:10.5 er). A range of ferrocene carboxylic acid derivatives (4f–h) are also compatible with this protocol, providing the desired planar chiral ferrocenes (Rp)-5f-h in high yields and high ers.

Reaction conditions: 1 or 4 (0.1 mmol), 2 (0.25 mmol), CuOAc (3.7 mg, 30 mol%), (S)-L21 (13.3 mg, 30 mol%), Cu(OAc)2 (12.7 mg, 0.07 mmol), NaOAc (8.2 mg, 0.1 mmol), DMSO (5.0 mL), 60 °C, air, 12 h. Isolated yield and the ratio of mono/di were determined by analysis of the crude 1H NMR. The er value for the mono-alkynylated product was determined by chiral HPLC.

To demonstrate the synthetic utility of the Cu-mediated asymmetric C–H alkynylation, we conducted the transformation on a gram-scale and elaborated the product to synthetically useful compounds. First, the gram-scale reaction was conducted with 70 mol% of Cu(OAc)2, 20 mol% of CuOAc, and 20 mol% of (S)-L21 (Fig. 7a), providing enantioenriched mono-alkynylated product 3a in 52% yield with slightly lower enantioselectivity (90:10 er), and the di-product (di-3a) in 7% yield. Recrystallization from hexane/dichloroethane provided 3a in very high selectivity (99.5:0.5 er) and 38% yield. To explore potential applications of the product (Fig. 7b), we derivatized 3a through a synthetic sequence, first through hydrogenation to ortho-alkylated 6a, followed by removal of the directing group to reveal ferrocene carboxylic acid 7a, with minimal loss of enantioenrichment (98:2 er). Ortho-substituted planar chiral ferrocene carboxylic acids have recently been shown by Matsunaga to be effective chiral ligands in Co-catalyzed enantioselective C(sp3)–H activation reactions76. As a demonstration of our method’s potential impact, we employed 7a as a chiral ligand in the Co-catalyzed C(sp3)–H amidation of thioamide 8 (Fig. 7b), providing product 10 in high yield (95%) and promising enantioselectivity (70.5:29.5 er). This example highlights the synthetic utility of our Cu-mediated enantioselective C–H alkynylation, which enables access to novel chemical space in valuable ortho-substituted planar chiral ferrocenes.

Mechanistic insights

The increased reactivity and high enantioselectivity imparted by the BINOL ligands were suggestive of ligand-accelerated catalysis, particularly in light of the strong background reaction. To further probe the possibility of ligand acceleration and collect data on the catalytic cycle, we then conducted some preliminary mechanistic studies on the system. We first performed a one-pot intermolecular competition kinetic isotope effect (KIE) experiment using 1a and ortho-deuterated D2−1a (Fig. 8a) in the presence of L21. A primary KIE was observed (4.9), indicating that C–H cleavage is likely the rate-determining step. This result indicates that the Cu-mediated C–H alkynylation is likely proceeding through CMD C–H activation at Cu, as opposed to SET pathways that do not involve Cu in C–H bond breaking, which would show no KIE (~1)86. This is a critical mechanistic insight as it both establishes that Cu cleaves C–H bonds in a similar manner as Pd and suggests a plausible mechanism for ligand involvement and acceleration. Having identified C–H cleavage at Cu as the rate-determining step, we next conducted initial rate studies to test for ligand acceleration (Fig. 8b). We observed a striking initial rate difference when comparing catalyst reactivity with and without BINOL-derived ligand (S)-L21. A rate acceleration of 11.6 times was observed with (S)-L21, strongly supporting our initial ligand acceleration hypothesis. Taken together, these experiments indicate that the BINOL scaffold accelerates the key rate- and enantio-determining C–H cleavage step at Cu, similar to the behavior of MPAAs and related ligands for Pd5,6,7.

In conclusion, Cu-mediated enantioselective ortho C–H alkynylation of ferrocene carboxylic acid derivatives has been realized using a chiral BINOL-derived diol ligand. This scaffold demonstrates ligand-accelerated catalysis with the Cu-mediated C–H activation, which both boosts the reactivity and also enables enantioselective catalysis. The development of additional Cu-catalyzed/mediated asymmetric C–H activation reactions with these chiral diol ligands is an ongoing research direction in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure for Cu-mediated asymmetric C–H alkynylation of ferrocenes

A 15 mL scale tube was charged with substrate 1 or 4 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), Cu(OAc)2 (12.7 mg, 0.07 mmol), CuOAc (3.7 mg, 0.03 mmol), (S)-L21 (13.3 mg, 30 mol%), Ag2CO3 (13.8 mg, 0.05 mmol), NaOAc (8.2 mg, 0.1 mmol), 2 (0.25 mmol, 2.5 equiv.), DMSO (5.0 mL) under air atmosphere. The tube was capped tightly, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 s and then stirred at 60 °C for another 12 h. Upon completion, the reaction was cooled to room temperature, and then EtOAc was added to dilute the reaction mixture. The organic layer was washed with NH3·H2O, saturated brine, and dried over Na2SO4. Volatiles were removed under a vacuum. The crude product was purified by column chromatography to afford the desired product (Rp)-3 or (Rp)-5. The ratio of mono/di was determined by the analysis of crude 1H NMR. Full experimental details and characterization of new compounds can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

X-ray structural data of compound (Rp)-3a (ccdc 2192815) is available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Other chemical characterizations and kinetics data are provided in the Supplementary Information file. All other data are provided in the Supplementary Information file or from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Newton, C. G., Wang, S.-G., Oliveira, C. C. & Cramer, N. Catalytic enantioselective transformations involving C–H bond cleavage by transition-metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 117, 8908–8976 (2017).

Saint-Denis, T. G., Zhu, R. Y., Chen, G., Wu, Q.-F. & Yu, J.-Q. Enantioselective C(sp3)–H bond activation by chiral transition metal catalysts. Science 359, eaao4798 (2018).

Liao, G., Zhang, T., Lin, Z.-K. & Shi, B.-F. Transition metal-catalyzed enantioselective C–H functionalization via chiral transient directing group strategies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19773–19786 (2020).

Liu, C.-X., Zhang, W.-W., Yin, S.-Y., Gu, Q. & You, S.-L. Synthesis of atropisomers by transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric C–H functionalization reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 14025–14040 (2021).

Shi, B.-F., Maugel, N., Zhang, Y.-H. & Yu, J.-Q. Pd(II)-catalyzed enantioselective activation of C(sp2)–H and C(sp3)–H bonds using monoprotected amino acids as chiral ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4882–4886 (2008).

Shao, Q., Wu, K., Zhuang, Z., Qian, S. & Yu, J.-Q. From Pd(OAc)2 to chiral catalysts: the discovery and development of bifunctional mono-N-protected amino acid ligands for diverse C–H functionalization reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 833–851 (2020).

Lucas, E. L. et al. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective β-C(sp3)–H activation reactions of aliphatic acids: a retrosynthetic surrogate for enolate alkylation and conjugate addition. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 537–550 (2022).

Albicker, M. R. & Cramer, N. Enantioselective palladium-catalyzed direct arylations at ambient temperature: access to indanes with quaternary stereocenters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 9139–9142 (2009).

Anas, S., Cordi, A. & Kagan, H. B. Enantioselective synthesis of 2-methyl indolines by palladium catalysed asymmetric C(sp3)–H activation/cyclisation. Chem. Commun. 47, 11483–11485 (2011).

Nakanishi, M., Katayev, D., Besnard, C. & Kündig, E. P. Fused indolines by palladium-catalyzed asymmetric C–C coupling involving an unactivated methylene group. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7438–7441 (2011).

Saget, T., Lemouzy, S. J. & Cramer, N. Chiral monodentate phosphines and bulky carboxylic acids: cooperative effects in palladium-catalyzed enantioselective C(sp3)–H functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 2238–2242 (2012).

Martin, N., Pierre, C., Davi, M., Jazzar, R. & Baudoin, O. Diastereo- and enantioselective intramolecular C(sp3)–H arylation for the synthesis of fused cyclopentanes. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 4480–4484 (2012).

Ye, B. & Cramer, N. Chiral cyclopentadienyl ligands as stereocontrolling element in asymmetric C–H functionalization. Science 338, 504–506 (2012).

Zheng, J., Cui, W.-J., Zheng, C. & You, S.-L. Synthesis and application of chiral spiro Cp ligands in rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric oxidative coupling of biaryl compounds with alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5242–5245 (2016).

Sun, Y. & Cramer, N. Rhodium(III)-catalyzed enantiotopic C–H activation enables access to P-chiral cyclic phosphinamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 364–367 (2017).

Fukagawa, S., Kojima, M., Yoshino, T. & Matsunaga, S. Catalytic enantioselective methylene C(sp3)–H amidation of 8-alkylquinolines using a Cp*Rh(III)/chiral carboxylic acid system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 18154–18158 (2019).

Gressies, S., Klauck, F. J. R., Kim, J. H., Daniliuc, C. G. & Glorius, F. Ligand-enabled enantioselective C(sp)3–H activation of tetrahydroquinolines and saturated aza-heterocycles by Rh(I). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 9950–9954 (2018).

Shibata, T. & Shizuno, T. Iridium-catalyzed enantioselective C–H alkylation of ferrocenes with alkenes using chiral diene ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5410–5413 (2014).

Zou, X. et al. Chiral bidentate boryl ligand enabled iridium-catalyzed asymmetric C(sp2)-H borylation of diarylmethylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5334–5342 (2019).

Zou, X., Li, Y., Ke, Z. & Xu, S. Chiral bidentate boryl ligand-enabled iridium-catalyzed enantioselective dual C–H borylation of ferrocenes: reaction development and mechanistic insights. ACS Catal. 12, 1830–1840 (2022).

Park, Y. & Chang, S. Asymmetric formation of γ-lactams via C–H amidation enabled by chiral hydrogen-bond-donor catalysts. Nat. Catal. 2, 219–227 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Iridium-catalyzed enantioselective C(sp3)–H amidation controlled by attractive noncovalent interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 7194–7201 (2019).

Genov, G. R., Douthwaite, J. L., Lahdenperä, A. S. K., Gibson, D. C. & Phipps, R. J. Enantioselective remote C–H activation directed by a chiral cation. Science 367, 1246–1251 (2020).

Liu, L., Song, H., Liu, Y.-H., Wu, L.-S. & Shi, B.-F. Achiral CpxIr(III)/Chiral carboxylic acid catalyzed enantioselective C–H amidation of ferrocenes under mild conditions. ACS Catal. 10, 7117–7122 (2020).

Zhang, C.-W. et al. Asymmetric C–H activation for the synthesis of P- and axially chiral biaryl phosphine oxides by an achiral Cp*Ir catalyst with chiral carboxylic amide. ACS Catal. 12, 193–199 (2021).

Schmiel, D. & Butenschön, H. Directed iron-catalyzed ortho-alkylation and arylation: toward the stereoselective catalytic synthesis of 1,2-disubstituted planar-chiral ferrocene derivatives. Organometallics 36, 4979–4989 (2017).

Fukagawa, S. et al. Enantioselective C(sp3)–H amidation of thioamides catalyzed by a Cobalt(III)/chiral carboxylic acid hybrid system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 1153–1157 (2019).

Liu, Y.-H. et al. Cp*Co(III)/MPAA-catalyzed enantioselective amidation of ferrocenes directed by thioamides under mild conditions. Org. Lett. 21, 1895–1899 (2019).

Ozols, K., Jang, Y. S. & Cramer, N. Chiral cyclopentadienyl cobalt(III) complexes enable highly enantioselective 3d-metal-catalyzed C–H functionalizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5675–5680 (2019).

Liu, Y.-H. et al. Cp*Co(III)-catalyzed enantioselective hydroarylation of unactivated terminal alkenes via C–H activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 19112–19120 (2021).

Jacob, N., Zaid, Y., Oliveira, J. C. A., Ackermann, L. & Wencel-Delord, J. Cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective C–H arylation of indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 798–806 (2022).

Diesel, J., Finogenova, A. M. & Cramer, N. Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective pyridone C–H functionalizations enabled by a bulky N-heterocyclic carbene ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4489–4493 (2018).

Chen, H., Wang, Y.-X., Luan, Y.-X. & Ye, M. Enantioselective twofold C–H annulation of formamides and alkynes without built-in chelating groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9428–9432 (2020).

Chen, X., Hao, X.-S., Goodhue, C. E. & Yu, J.-Q. Cu(II)-catalyzed functionalizations of aryl C–H bonds using O2 as an oxidant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6790–6791 (2006).

Uemura, T., Imoto, S. & Chatani, N. Amination of the ortho C–H bonds by the Cu(OAc)2-mediated reaction of 2-phenylpyridines with anilines. Chem. Lett. 35, 842–843 (2006).

Rao, W.-H. & Shi, B.-F. Recent advances in copper-mediated chelation-assisted functionalization of unactivated C–H bonds. Org. Chem. Front. 3, 1028–1047 (2016).

Dai, H.-X., Shang, M., Sun, S.-Z., Wang, H.-L. & Wang, M.-M. Recent progress on copper-mediated directing-group-assisted C(sp2)–H activation. Synthesis 48, 4381–4399 (2016).

Tran, L. D., Popov, I. & Daugulis, O. Copper-promoted sulfenylation of sp2 C–H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18237–18240 (2012).

Nishino, M., Hirano, K., Satoh, T. & Miura, M. Copper-mediated C–H/C–H biaryl coupling of benzoic acid derivatives and 1,3-azoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 4457–4461 (2013).

Wang, Z., Ni, J., Kuninobu, Y. & Kanai, M. Copper-catalyzed intramolecular C(sp3)–H and C(sp2)–H amidation by oxidative cyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 3496–3499 (2014).

Wu, X., Zhao, Y., Zhang, G. & Ge, H. Copper-catalyzed site-selective intramolecular amidation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 3706–3710 (2014).

Liu, Y. J., Liu, Y. H., Yin, X. S., Gu, W. J. & Shi, B. F. Copper/silver-mediated direct ortho-ethynylation of unactivated (hetero)aryl C–H bonds with terminal alkyne. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 205–209 (2015).

Shang, M. et al. Identification of monodentate oxazoline as a ligand for copper-promoted ortho-C–H hydroxylation and amination. Chem. Sci. 8, 1469–1473 (2017).

Kim, H., Heo, J., Kim, J., Baik, M.-H. & Chang, S. Copper-mediated amination of aryl C–H bonds with the direct use of aqueous ammonia via a disproportionation. Pathw. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 14350–14356 (2018).

Takamatsu, K., Hayashi, Y., Kawauchi, S., Hirano, K. & Miura, M. Copper-catalyzed regioselective C–H amination of phenol derivatives with assistance of phenanthroline-based bidentate auxiliary. ACS Catal. 9, 5336–5344 (2019).

Shang, M., Sun, S.-Z., Dai, H.-X. & Yu, J.-Q. Cu(II)-mediated C–H amidation and amination of arenes: exceptional compatibility with heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 3354–3357 (2014).

Shang, M., Wang, H.-L., Sun, S.-Z., Dai, H.-X. & Yu, J.-Q. Cu(II)-mediated ortho C–H alkynylation of (hetero)arenes with terminal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11590–11593 (2014).

Shang, M. et al. Exceedingly fast Copper(II)-promoted ortho C–H trifluoromethylation of arenes using TMSCF3. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10439–10442 (2014).

Shang, M., Sun, S.-Z., Dai, H.-X. & Yu, J.-Q. Cu(OAc)2-catalyzed coupling of aromatic C–H bonds with arylboron reagents. Org. Lett. 16, 5666–5669 (2014).

Wang, H.-L. et al. Cu(II)-catalyzed coupling of aromatic C–H bonds with malonates. Org. Lett. 17, 1228–1231 (2015).

Sun, S.-Z. et al. Cu(II)-mediated C(sp2)–H hydroxylation. J. Org. Chem. 80, 8843–8848 (2015).

Shang, M. et al. Copper-mediated late-stage functionalization of heterocycle-containing molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5317–5321 (2017).

Yu, J.-F., Li, J.-J., Wang, P. & Yu, J.-Q. Cu-mediated amination of (hetero)aryl C–H bonds with NH azaheterocycles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 18141–18145 (2019).

Li, J.-J., Wang, C.-G., Yu, J.-F., Wang, P. & Yu, J.-Q. Cu-catalyzed C–H alkenylation of benzoic acid and acrylic acid derivatives with vinyl boronates. Org. Lett. 22, 4692–4696 (2020).

Kong, W.-J. et al. Copper-mediated diastereoselective C–H thiolation of ferrocenes. Organometallics 37, 2832–2836 (2018).

Liu, C.-X., Gu, Q. & You, S.-L. Asymmetric C–H bond functionalization of ferrocenes: new opportunities and challenges. Trends Chem. 2, 737–749 (2020).

Gao, D.-W., Shi, Y.-C., Gu, Q., Zhao, Z.-L. & You, S.-L. Enantioselective synthesis of planar chiral ferrocenes via palladium-catalyzed direct coupling with arylboronic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 86–89 (2013).

Pi, C. et al. Synthesis of ferrocene derivatives with planar chirality via palladium-catalyzed enantioselective C–H bond activation. Org. Lett. 16, 5164–5167 (2014).

Gao, D.-W., Gu, Q. & You, S.-L. An enantioselective oxidative C–H/C–H cross-coupling reaction: highly efficient method to prepare planar chiral ferrocenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2544–2547 (2016).

Gao, D.-W., Yin, Q., Gu, Q. & You, S.-L. Enantioselective synthesis of planar chiral ferrocenes via Pd(0)-catalyzed intramolecular direct C–H bond arylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4841–4844 (2014).

Deng, R. et al. Palladium-catalyzed intramolecular asymmetric C–H functionalization/cyclization reaction of metallocenes: an efficient approach toward the synthesis of planar chiral metallocene compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4472–4475 (2014).

Shibata, T., Shizuno, T. & Sasaki, T. Enantioselective synthesis of planar-chiral benzosiloloferrocenes by Rh-catalyzed intramolecular C–H silylation. Chem. Commun. 51, 7802–7804 (2015).

Zhang, Q.-W., An, K., Liu, L.-C., Yue, Y. & He, W. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular C–H silylation for the syntheses of planar-chiral metallocene siloles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 6918–6921 (2015).

Wang, Q. et al. Rhodium(III)-catalyzed enantioselective C–H activation/annulation of ferrocenecarboxamides with internal alkynes. ACS Catal. 12, 3083–3093 (2022).

Ito, M., Okamura, M., Kanyiva, K. S. & Shibata, T. Catalytic enantioselective synthesis of azepine-fused planar-chiral ferrocenes by Pt-catalyzed cycloisomerization. Organometallics 38, 4029–4035 (2019).

Seiwert, B. & Karst, U. Ferrocene-based derivatization in analytical chemistry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 390, 181–200 (2008).

Braga, S. S. & Silva, A. M. S. A new age for iron: antitumoral ferrocenes. Organometallics 32, 5626–5639 (2013).

Lerayer, E. et al. Highly functionalized ferrocenes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 419–445 (2020).

Sansook, S., Hassell-Hart, S., Ocasio, C. & Spencer, J. Ferrocenes in medicinal chemistry; a personal perspective. J. Organomet. Chem. 905, 121017 (2020).

Ruble, J. C., Latham, H. A. & Fu, G. C. Effective kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols with a planar-chiral analogue of 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine. use of the Fe(C5Ph5) group in asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 1492–1493 (1997).

Zhou, X.-T., Lin, Y.-R. & Dai, L.-X. A simple and practical access to enantiopure 2,3-diamino acid derivatives. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 10, 855–862 (1999).

Nishibayashi, Y., Takei, I., Uemura, S. & Hidai, M. Extremely high enantioselective redox reaction of ketones and alcohols catalyzed by RuCl2(PPh3)(oxazolinylferrocenylphosphine). Organometallics 18, 2291–2293 (1999).

Manoury, E., Fossey, J. S., Aϊt-Haddou, H., Daran, J.-C. & Balavoine, G. G. A. New ferrocenyloxazoline for the preparation of ferrocenes with planar chirality. Organometallics 19, 3736–3739 (2000).

Tao, B., Lo, M. M. C. & Fu, G. C. Planar-chiral pyridine N-oxides, a new family of asymmetric catalysts: exploiting an η5-C5Ar5 ligand to achieve high enantioselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 353–354 (2001).

You, S.-L., Hou, X.-L., Dai, L.-X., Yu, Y.-H. & Xia, W. Role of Planar chirality of S,N- and P,N-ferrocene ligands in palladium-catalyzed allylic substitutions. J. Org. Chem. 67, 4684–4695 (2002).

Sekine, D. et al. Chiral 2-aryl ferrocene carboxylic acids for the catalytic asymmetric C(sp3)–H activation of thioamides. Organometallics 38, 3921–3926 (2019).

Sutcliffe, O. B. & Bryce, M. R. Planar chiral 2-ferrocenyloxazolines and 1,1′-bis(oxazolinyl)ferrocenes—syntheses and applications in asymmetric catalysis. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 14, 2297–2325 (2003).

Riant, O., Samuel, O. & Kagan, H. B. A general asymmetric synthesis of ferrocenes with planar chirality. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 5835–5836 (1993).

Nishibayashi, Y. & Uemura, S. Asymmetric synthesis and highly diastereoselective ortho-lithiation of oxazolinylferrocenes. Synlett 1995, 79–81 (1995).

Richards, C. J., Damalidis, T., Hibbs, D. E. & Hursthouse, M. B. Synthesis of 2-[2-(diphenylphosphino)ferrocenyl]oxazoline ligands. Synlett 1995, 74–76 (1995).

Sammakia, T., Latham, H. A. & Schaad, D. R. Highly diastereoselective ortho lithiations of chiral oxazoline-substituted ferrocenes. J. Org. Chem. 60, 10–11 (1995).

Riant, O., Samuel, O., Flessner, T., Taudien, S. & Kagan, H. B. An efficient asymmetric synthesis of 2-substituted ferrocenecarboxaldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 62, 6733–6745 (1997).

Mou, Q. et al. Cp*Ir(iii)/chiral carboxylic acid-catalyzed enantioselective C–H alkylation of ferrocene carboxamides with diazomalonates. Org. Chem. Front. 8, 6923–6930 (2021).

Han, Y.-Q. et al. Pd(II)-catalyzed enantioselective alkynylation of unbiased methylene C(sp3)–H bonds using 3,3′-fluorinated-BINOL as a chiral ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 4558–4563 (2019).

Chang, X., Ma, P.-L., Chen, H.-C., Li, C.-Y. & Wang, P. Asymmetric synthesis and application of chiral spirosilabiindanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 8937–8940 (2020).

Suess, A. M., Ertem, M. Z., Cramer, C. J. & Stahl, S. S. Divergence between organometallic and single-electron-transfer mechanisms in copper(II)-mediated aerobic C–H oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9797–9804 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1500200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22171277, 22101291, 21821002), the Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (23XD1424500), Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry, and State Key Laboratory of Organometallic Chemistry for financial support. We also thank H.-C. Shen for verifying the reproducibility of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.K. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.-J.L. and L.T. assisted with some substrate preparation. K.W. helped prepare the manuscript. P.W. directed the project. C.-H.D., P.W., and J.-Q.Y. conceived the concept and prepared this manuscript with feedback from X.K.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuang, X., Li, JJ., Liu, T. et al. Cu-mediated enantioselective C–H alkynylation of ferrocenes with chiral BINOL ligands. Nat Commun 14, 7698 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43278-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43278-z

This article is cited by

-

Designing 2D carbon dot nanoreactors for alcohol oxidation coupled with hydrogen evolution

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Enantioselective synthesis of saddle-shaped eight-membered lactones with inherent chirality via organocatalytic high-order annulation

Nature Communications (2024)