Abstract

Wildfire disturbance propagation along fluvial networks remains poorly understood. We use incident, atmospheric, and water-quality data from the largest wildfire in New Mexico’s history to quantify how this gigafire affected surface runoff processes and mobilized wildfire disturbances into fluvial networks after burning 1382 km2. Surface runoff post-fire increased compared to pre-fire conditions, and precipitation events that are frequently observed in the affected watershed (<2-year recurrence) and fell during the post-fire first rainy season resulted in uncorrelated, less frequently observed runoff events (10-year recurrence). Besides these shifts in runoff generation, the magnitude and fluctuation of daily water quality parameters and relevant ecosystem processes also shifted over multiple months, even at sites located >160 km downstream of the burn perimeter. Our findings emphasize the need to incorporate spatially resolved longitudinal sampling designs into wildfire water quality research and highlight the spatiotemporal co-dependency among atmospheric, terrestrial, and aquatic processes in defining the net outcome of wildfire disturbance propagation along impacted fluvial networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wildfires are increasing in frequency, extent, and severity across the western United States (USA) and other regions of Earth1,2,3 due to climate change impacts to drought, rainfall patterns3,4,5,6,7, and plant water limitation8. These fires impact watershed characteristics that control surface runoff, including reducing vegetation cover and altering soil properties such as water repellency9, surface sealing10, and soil aridity11. Subsequent alterations to runoff processes in burned watersheds are common, including increasing low and high flows12 and generating extreme flood events13. These changes to surface runoff and the mobilization of terrestrial burned material post-fire generate aquatic wildfire disturbances that have cascading effects on environmental conditions and ecosystem services in impacted fluvial networks1,14,15,16,17,18. The magnitude, extent, and duration of those aquatic disturbances are controlled by burn severity, watershed characteristics, post-fire precipitation patterns, and ecosystem recovery rates19,20,21,22.

Altered water quality is a primary post-fire environmental disturbance to streams draining burned watersheds1,12,23. Increased runoff, mass wasting, and debris flows transport wildfire disturbances into receiving waters, generally causing increases in sediment export12,24 proportional to the percentage of the watershed burned25,26. Post-fire water chemistry disturbances include increases in total ion export, nutrient concentrations and metals12,23,27, and significant but episodic declines in dissolved oxygen14. Most aquatic disturbances to downstream water quality decline gradually within 5 years of the fire23,26,27, while other effects persist for decades23,28,29.

Wildfires contribute to at least ten of the most crucial disturbances that cause stream impairments listed by the US Environmental Protection Agency’s water quality assessment30, including increasing the transport of materials and altering critical physical and chemical parameters. Paradoxically, while wildfires exacerbate impairments, they are frequently excluded as a source of disturbance because fires are unpredictable, and monitoring water quality post-fire is logistically challenging1. Additionally, very little is known about the propagation of post-fire water quality disturbances throughout fluvial networks, with only a few known case studies in which monitoring instrumentation had been fortuitously deployed pre-fire to study non-fire-related water quality issues. Limited data revealed wildfire impacts over hundreds of kilometers downstream of the burn scar14,17, affecting reservoirs and municipal water supply systems31. However, little is known about the coupling between post-fire rainfall-runoff events and the associated propagation of aquatic wildfire disturbances through burned and unburned parts of affected watersheds.

Since current fire models predict that the prevalence and size of wildfires and associated damage will continue to increase due to anthropogenic climate change and forest management practices32,33,34,35,36, we need to quantify and predict the propagation of wildfire disturbances through fluvial networks. In 2022, we formed a rapid response team37 to address this critical knowledge gap by deploying water quality sondes co-located with flow gages along watersheds draining the largest wildfire recorded in New Mexico, which burned 1382 km2 becoming a gigafire38 (i.e., >1 × 109 m2). Data collection began 2 weeks after fire ignition but before rainfall mobilized burned terrestrial material, and covered the completion of the first post-fire rainfall season, i.e., the North American Monsoon. Monitoring occurred within the burned area and at hydrologically connected sites up to 178 km away from their headwaters, which were located inside the burn scar. The goals of this study were to quantify (1) the impacts of a gigafire on terrestrial vegetation and surface runoff in affected watersheds, (2) the longitudinal propagation of rainfall-runoff events post-fire and their impacts on water quality, and (3) sub-year impacts of wildfire disturbances on water quality dynamics and ecosystem processes along fluvial networks.

Results

Impacts of fire on terrestrial vegetation and surface runoff

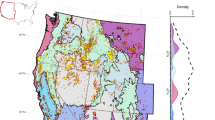

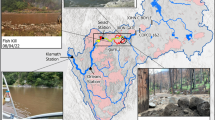

The Hermit’s Peak–Calf Canyon (HPCC) wildfire began on April 6th, 2022, and was contained on August 21st, 2022, after burning 1382 km2 and becoming the largest recorded in New Mexico, USA (section “Methods”). Our analyses focus on sites along the Gallinas (sites starting with P to represent the receiving water and subscripts indicating distance in kilometers from the headwaters) and Sapello (sites starting with C) watersheds, which drain into the Pecos and Canadian Rivers, respectively (Fig. 1). Approximately 87% of the 186 km2 and 47% of the 343 km2 of Gallinas and Sapello watersheds above P226 and C129 were burned, respectively. Inside the burned area, 19 and 21% of the Gallinas and Sapello watersheds were designated high severity, 25 and 32% moderate severity, and 43 and 41% low severity (section “Methods”). The Pecos and Canadian watersheds are non-urban, draining only 0.75% and 0.9% of urban lands39.

Stream flow and water quality sampling locations in the Pecos (sites P120–P5167) and Canadian (sites C129–C3178) watersheds. P120–P4136 are on Gallinas Creek, a major tributary to the Pecos River, and C129 and C286 are on the Sapello and Mora Rivers, which drain into the Canadian River. Outside the forested areas (mixed canopy), most of the remainder of the watersheds are shrublands and grasslands. Longitudinal sampling locations are identified with subscripts indicating distance from the headwaters in kilometers. ArcGIS Desktop 10.8 (Esri, West Redlands, CA, USA) was employed to generate the map.

Two weeks after the fire began, during groundwater-sustained baseflow conditions (Fig. S1), we deployed a rapid response team37 to monitor the propagation of wildfire disturbances. In the Pecos River watershed, we collected data at four 4th-order streams along Gallinas Creek that were located upstream of the confluence with the Pecos River (P120, P226, P361, P4136) and at a 5th-order site on the Pecos River (P5167), upstream of Santa Rosa Lake (Fig. 1, Table S1). Water quality instruments were installed at P120–P361 and P5167, and discharge was measured at P226–P5167. Data were also collected for two hydrologically connected tributaries of the Canadian River, the 4th-order Sapello Creek (C129), the 5th-order Mora River (C286), and at a site on the 6th-order Canadian River (C3178) immediately upstream of Conchas Lake (Fig. 1, Table S1). Water quality data were collected at all sites in the Canadian River watershed, but discharge was only available at C3178. Due to the greater availability of discharge data in the Pecos River watershed, we used that watershed to determine the impact of the wildfire on the propagation of rainfall-runoff events. Sites from both watersheds were used to assess the propagation of fire impacts to water quality during discrete runoff events and to estimate changes in water quality and ecosystem processes post-fire. We divided our semi-continuous data into periods before and after the North American Monsoon season mobilized wildfire disturbances from terrestrial into aquatic subsystems, which are referred to as pre- (May to mid-June 2022) and post-connectivity (mid-June to mid-September 2022). Between the declaration of the fire in April and the Monsoon season, rainfall was negligible (Fig. S1), and the characteristic fire weather in the region featured sunny days with low relative humidity levels reaching 4% and wind gusts of up to 102 km/h (section “Methods”).

Our analysis first focused on the impact of the fire on vegetation. The HPCC wildfire severely decreased plant biomass in the impacted watersheds, as shown by Landsat enhanced vegetation index (EVI) data (Fig. 2A and section “Methods”), which is similar to the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) but uses additional wavelengths to correct for atmospheric conditions and canopy background noise, increasing sensitivity in areas with dense vegetation40. EVI values from spring 2022 closely matched those from the 15 years pre-fire. However, after the fire began, values declined to ~0.12 in May 2022 compared to the pre-fire value of ~0.25. For the rest of 2022, EVI remained consistently lower than pre-fire averages (Fig. 2A).

A Enhanced vegetation index (EVI) values from a 15-year period pre-fire in the Gallinas and Sapello watersheds deviate from 2022 post-fire values. B Example of three post-fire rainfall-runoff event responses observed at sampling location P226 between July and September 2022 that were better simulated C–E by HEC-HMS models using post-fire watershed parameters (see section “Methods”). P226 is located 26 km downstream from the headwaters of Gallinas Creek. Annual exceedance probabilities (AEPs) for 5-min rainfall (data source = NOAA Atlas 14) and instantaneous discharge (data source = USGS Streamstats) are shown for reference.

Next, we assessed how the terrestrial impacts of the fire affected surface runoff (Fig. 2B–E, Fig. S2). We used a Hydrologic Engineering Center—Hydrologic Modeling Software (HEC-HMS) model (section “Methods”) calibrated with pre-fire data from Gallinas Creek to estimate surface runoff flows that would have happened under pre-fire watershed conditions with the observed rainfall data post-fire41. We then compared those values with HEC-HMS flow predictions using post-fire watershed parameters and with observed flows (Fig. 2C–E). Post-fire HEC-HMS parameters were estimated through hydrologic impact factors42 that vary as a function of the percentages of subbasins with high and moderate severities (section “Methods”). The rainfall events observed during the Monsoon season were average, i.e., below the 50% annual exceedance probability (AEP), corresponding to a 2-year recurrence interval or less. The HEC-HMS model with pre-fire parameters predicted that these events would result in surface flows frequently exceeded (i.e., below 50% AEP), with simulated peak flows ranging from 0.9 to 4 m3s−1 (Fig. 2C–E). However, the model predictions with post-fire parameters ranged from 20 to 60 m3s−1 and more closely matched the observed surface flows reaching up to 10% AEP (10-year recurrence interval) (Fig. 2C–E). While the inherently simplified model formulation and flow representation in HEC-HMS may affect peak discharge and return interval estimates due to its deterministic conceptualization (i.e., boundary conditions, initial conditions, and parameters are assumed to be exactly known), we found comparable insights from a flow exceedance probability analysis of daily maximum values, which showed that post-fire runoff events, particularly near the burn perimeter, were larger than events that were exceeded by <1% of all records (Fig. S3). Together, these results suggest drastic changes between pre- and post-fire watershed hydrologic responses directly linked to the HPCC wildfire, as seen in the post-fire flood conditions in summer 2022 (Fig. S2).

Propagation of rainfall-runoff events

After determining the impact of the wildfire on surface runoff, we investigated how runoff events propagated through the fluvial network. Six post-fire rainfall events in the Pecos River watershed generated direct runoff (i.e., above baseflow) events with sufficiently distinct hydrographs to track their propagation across sites (P226–P5167, Fig. 3). The amplitude and volume of these direct runoff events consistently decreased downstream (Fig. 3A, B), with the median direct runoff volume decreasing from 312,000 m3 at P226 to 47,200 m3 at P5167. The station-to-station median volumes changed to 53.4% of the upstream value between P226 and P361, 54.6% between P361 and P4136, and 52.0% between P4136 and P5167. With respect to P226, the median volumes propagating to P361, P4136, and P5167 changed to 53.4, 29.1, and 15.1% of the upstream value, respectively. As expected, the runoff propagating across the fluvial network changed for each of the six storms based on antecedent conditions (Fig. 3C, D). These results indicate that while the hydrologic impacts of the fire propagated downstream, the direct runoff volume generated near the burn area was strongly attenuated along the fluvial network, following characteristic trends observed in net losing watersheds of the arid southwestern USA7,43,44. In such watersheds, stream flows decrease longitudinally due to human withdrawals (e.g., drinking water supply and irrigation), storage in reservoirs and lakes, and natural processes (e.g., stream to groundwater losing conditions and evapotranspiration). While net losing conditions prevail in arid watersheds, increased runoff production post-fire and reduced withdrawals and storage due to water contamination may have contributed to decreased or delayed longitudinal flow reductions. Therefore, the trends shown in Fig. 3 are expected to be more accentuated during pre-fire conditions.

A Example of one event of direct runoff (i.e., above baseflow) propagation from Gallinas Creek (sampling locations P226, P361, and P4136) to the Pecos River (P5167). B Distribution of total volumes of direct runoff measured at each sampling location for six storm events after Monsoon rainfall connected burned terrestrial and aquatic subsystems. C Station-to-station volume changes of a given runoff event between successive downstream sites, and D with respect to P226. Longitudinal sampling locations are identified with subscripts indicating distance from the headwaters in kilometers.

Impacts of fire on water quality changes and ecosystem processes

Since post-fire runoff events exceeded historical records (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2) and propagated along the fluvial network (Fig. 3), we compared post-fire and historical water quality data to explore the impact of the HPCC fire on water quality parameters. P226, located near the burn perimeter, was the only one of our sites with historical water quality data. These data were used to inform the water treatment plant of the City of Las Vegas, NM, which withdraws drinking water from Gallinas Creek. All historical pre-fire data were collected before 1990, after which the monitoring program was halted. Comparable post-fire data for 2022 was collected as part of the HPCC fire national emergency declaration from the US Government (section “Methods”).

We found significant (p < 0.05) differences between historical pre-fire and post-fire data for suspended sediment discharge (SSD), turbidity, and nitrate (section “Methods”, Fig. 4, and Fig. S4). For SSD, 52 and 80% of the pre- and post-fire samples exceeded the pre-fire median value of 465 kg/day, respectively. The maximum SSD values exceeded the pre-fire median 107-fold and 11,023-fold pre- and post-fire, indicating post-fire changes beyond the seasonality captured by pre-fire data. For turbidity, 50 and 90% of the pre- and post-fire samples exceeded the pre-fire median value of 3.5 nephelometric turbidity ratio units (NTRU), respectively. The maximum turbidity values exceeded the pre-fire median 29-fold and 120-fold pre- and post-fire. Also, some of the first post-fire runoff events exceeded turbidity levels observed pre-fire under discharges eightfold greater (Fig. S4A). Acknowledging that changes in global atmospheric deposition patterns could overlap with fire-related changes, we found that 19 and 89% of the pre- and post-fire nitrate samples exceeded the pre-fire median concentration of 0.1 mg/L. The maximum nitrate concentrations exceeded the pre-fire median 4-fold and 23-fold pre- and post-fire (Fig. S4B). Together, results in Figs. 3, 4, and S4 indicate that the HPCC fire generated unprecedented high runoff disturbances that mobilized sediments and other fire materials, contributing to increases in turbidity and nutrients.

The Hermit’s Peak–Calf Canyon gigafire generated water quality disturbances associated with increased suspended sediment discharges and turbidities compared to historical values. All samples are from Gallinas Creek near Montezuma, P226, located 26 km downstream from the headwaters of Gallinas Creek, near the burn perimeter and the intake of the water treatment plant of the city of Las Vegas, NM.

We used our semi-continuous sensor data to characterize impacts to water quality parameters and ecosystem processes longitudinally at diel timescales during pre- (May to mid-June) and post-connectivity (mid-June to mid-September) periods in 2022. We focused our analysis on the P226, P361, C129, and C286 sites, where fire-related impacts were most pronounced. A principal component analysis (PCA) (section “Methods”) of daily means for DO, fluorescent dissolved organic matter (fDOM), pH, specific conductivity (SpCond), turbidity, and measures of ecosystem processes, i.e., ecosystem respiration (ER) and gross primary production (GPP), showed clear separation pre- and post-connectivity (Fig. 5). At all sites, higher values of GPP and SpCond were associated with pre-connectivity periods, while elevated DO, turbidity, and fDOM occurred post-connectivity (Fig. 5). These data suggest relatively consistent impacts to water quality parameters and ecosystem processes at downstream locations far from the burn scar.

Principal component analysis (PCA) biplots constructed with mean daily values for dissolved oxygen (DO), fluorescent dissolved organic matter (fDOM), pH, specific conductivity (SpCond), turbidity, ecosystem respiration (ER), and gross primary production (GPP). Dots represent data before and after Monsoon rainfall connected burned terrestrial and aquatic subsystems (pre- and post-connectivity), and arrows represent parameter eigenvectors. Longitudinal sampling locations are identified with subscripts indicating distance from the headwaters in kilometers.

The time series of DO data for the sites in Fig. 5 showed a clear decrease in diel variation post-connectivity (Fig. 6). Stream metabolism values (section “Methods”), represented as metabolic fingerprints45, also reflected this change, with post-connectivity declines in both ER and GPP at three sites (P226, P361, and C129) and an increase in ER at C286 (Fig. 6). The decrease in GPP in response to an increase in runoff was slightly delayed at C286, where the runoff from the first storm event of the summer caused a slight and temporary decrease in the diel variation in DO in late June, which was then followed by an additional decline in the diel signal in early July, after which the DO variation remained low for the remainder of the summer (Fig. 6). Additionally, at P361, both DO data and the metabolic fingerprints suggest that the recovery of the primary producer communities began in late August. However, a subsequent storm event in mid-September resulted in scouring and an additional reset of the primary producers (Fig. 6).

Dissolved oxygen (DO) time series and metabolic fingerprints for upstream and mid-network sampling locations in the Pecos (P226 and P361) and Canadian (C129 and C286) watersheds. The connectivity period began when Monsoon rainfall connected burned terrestrial and aquatic subsystems. Longitudinal sampling locations are identified with subscripts indicating distance from the headwaters in kilometers.

Propagation of water quality disturbances during runoff events

After characterizing the generation of water quality disturbances and their impacts on ecosystem processes, we examined their propagation along the fluvial networks. We used wavelet coherence (section “Methods”) to identify the propagation of temperature, DO, SpCond, pH, and turbidity signals along four reaches bounded by our sensors in the Pecos and Canadian watersheds. Wavelet coherence allows for temporal flexibility, resolves relationships across different periods from sub-hourly to daily timescales, and focuses on patterns rather than absolute input data values, making it an ideal tool for comparisons between datasets that vary in time and magnitude46. The power of coherence (or localized correlation coefficients) indicates the strength of the relationship between two observation sites at a given time point for a given period47. We limited our analysis to sub-daily periods to exclude any connections between sites related to diel patterns.

We first focused on wavelet coherence for pH, which exhibited clear decreases when runoff increased (Fig. S1), between sites of adjacent upper (P120–P226) and lower (P226–P361) reaches along Gallinas Creek (Fig. 7). In the upper reach, which is short (~6 km) and located within the burn scar, we observed consistent increases in wavelet coherence during runoff events (Fig. 7a, b), which indicated the propagation of pH disturbances along the reach. For the downstream reach, which is substantially longer (~40 km) and farther from the burn scar, coherence was weaker, suggesting an attenuated propagation of pH disturbances. While most runoff events that increased coherence along the upper reach also propagated to the lower reach, some events did not (e.g., near June 21, 2022) (Fig. 7c). To compare coherence between the two reaches, we plotted mean coherence across all periods for each timestamp (Fig. 7d). Consistent with observations in Fig. 7b, c, coherence was approximately an order of magnitude higher for the upper reach, with broader peaks consistent with increased dispersion of pH signals downstream (Fig. 7d).

a Discharge data from sampling location P226, b wavelet coherence analysis of pH from sites P120 to P226 and c from sites P226 to P361, where colors depict coherence power (localized correlation coefficients between two time series), and d the mean coherence power in the Pecos watershed after Monsoon rainfall connected burned terrestrial and aquatic subsystems. Longitudinal sampling locations are identified with subscripts indicating distance from the headwaters in kilometers.

Next, we explored if the propagation patterns observed in Fig. 7 for pH transferred to other reaches and water quality parameters (Fig. S5). Based on mean power (analogous to Fig. 7d), temperature had the highest average coherence across all sites, SpCond and turbidity had the lowest average coherence, and pH and DO were consistently intermediate (Fig. S5). Based on Fig. 7, we expected that coherence would decrease from shorter upstream reaches to longer downstream reaches due to longitudinal dispersion. While this was observed for SpCond and temperature in both watersheds, for DO and turbidity in the Canadian River and pH in the Pecos River, average coherence unexpectedly increased for pH in the Canadian River and turbidity in the Pecos River (Fig. S5). These findings suggest that the propagation of water quality disturbances was consistently detectable across water quality parameters and along reaches extending to our most downstream sites (P5157 and C3178).

Discussion

The fluvial propagation of wildfire disturbances depends on the spatial and temporal connectivity of atmospheric, terrestrial, and aquatic subsystems. Despite the rapid global increase in fire disturbances, the scientific literature on fluvial network-scale propagation of these impacts is limited1,14,17,48. This study features an analysis of disturbance origination and propagation along two fluvial networks following the largest wildfire recorded in New Mexico, a gigafire, and explores context-dependent nuances that affected the role of each subsystem.

Impacts of the HPCC wildfire on terrestrial vegetation and surface runoff

In our non-urban watersheds, the hydrologic impacts of wildfires to aquatic subsystems depend on post-fire rainfall patterns, the damage caused to terrestrial subsystems, the progressive exhaustion of easily mobilized soil and burned material, and the recovery of vegetation post-fire48,49,50,51. High-intensity, short-duration, infrequent rainfall events48,52,53,54 on forested areas with high burn severities and low-infiltration-capacity soils mobilize more soil and burned material into fluvial networks50,55,56,57,58,59. However, following the HPCC wildfire, the variable spatiotemporal distribution of rainfall (Fig. S6), the heterogeneity of burn severities (Fig. 1), and the patchy recovery of soils and vegetation combined to create a highly dynamic mosaic of surface runoff impacts. As in other large, high-intensity fires in the southwestern USA40,60, the HPCC wildfire resulted in the near total removal of vegetation from large portions of the burn scar, as evidenced by rapid and severe reductions in EVI (Fig. 2A) and field observations (Fig. S2). Post-fire reductions in vegetation are directly linked to altered runoff and hydrologic responses to rainfall events10,57,61, with average decreases in infiltration of ~50-fold and ~70- and 1000-fold increases in water export and runoff, respectively12. While post-fire rainfall events during the 2022 Monsoon season were numerous, no event exceeded the 2-year recurrence interval. Thus, the numerous high-flow events characterized by highly unusual runoff events with up to a 10-year recurrence interval that we observed are consistent with impacts following fires in other forested catchments57,62,63,64. However, the post-fire calibrated HEC-HMS model suggests that if high-intensity rainfall events with a 10-year recurrence interval had fallen over the burned area, the flooding impacts generated by the HPCC wildfire would have been considerably more catastrophic, resulting in runoff events of up to 200-year recurrence interval.

Impacts of wildfire disturbances on water quality dynamics and ecosystem processes along fluvial networks

The discrete water quality data collected pre- and post-fire to inform the operation of the water treatment plant of the city of Las Vegas, NM, verified that the HPCC fire generated significant water quality disturbances (Fig. 4), as is typical following large fires12,23. Our semi-continuous data captured clear separations between pre- and post-connectivity responses (Fig. 5). There were consistent increases in turbidity (suspended sediment surrogate) post-connectivity in both fluvial networks (Fig. S1), which are consistent with increased erosion rates common after fires65,66. There were declines in SpCond, which are unusual because fires typically increase the transport of dissolved ions12,26,44. This discrepancy is likely associated with the relatively high baseline of conductance values in arid streams67,68,69, where limited flushing from rainfall and elevated evapotranspiration promote salt accumulation, and new rainfall dilutes salts. There were also declines in pH, most likely linked to the acidity of rainfall, the mobilization of organic acids, or other mechanisms that countered observed increases in pH due to the mobilization of ash and other alkaline materials post-fire23,70,71,72. Interestingly, while fDOM increased in Gallinas Creek, it decreased in the Sapello River, suggesting differences in the flushing of dissolved organic carbon (DOC). Given the marked similarities in land use, land cover, and burn severities between these two watersheds upstream of the sites where fDOM was measured (section “Methods”), the higher levels of fDOM flushed from Gallinas Creek may be associated with its smaller watershed size (186 vs. 343 km2) and higher percentage of burned area (87% vs. 47%). However, we also note that DOC responses to wildfire can be highly variable, with both increased and decreased concentrations reported73.

In both watersheds, post-connectivity DO values had less variability compared to pre-connectivity values, suggesting fire-related changes in stream metabolism. Wildfire disturbances impact each of the key variables that mediate metabolism in stream ecosystems, i.e., temperature, light and nutrient availability, and flow extremes45,74. Therefore, post-fire impacts to GPP and ER depend on site-specific disturbances to water quality parameters. In other watersheds, primary production has increased through reductions in light limitation post-fire28,75 or through induced fertilization from excess nutrients76. In this study, the consistent decrease in GPP estimated post-connectivity (Fig. 6) is likely due to the increase in scouring flow disturbances, which impact benthic primary producer communities77,78, and increased light limitation due to elevated turbidity and sediment transport, which reduces GPP45. This finding is similar to another recent study in the southwestern USA in which increased turbidity depressed GPP79, suggesting this impact may be common in some regions. The reduction in GPP and impact to ER at sites distant to the fire post-connectivity provides quantitative evidence that wildfire disturbances propagating through fluvial networks can generate negative impacts to ecosystem services along hundreds of kilometers and over multiple months. Our findings emphasize the need to incorporate spatially resolved longitudinal sampling designs into wildfire water quality research.

Longitudinal propagation of rainfall-runoff events post-fire and their impacts on water quality

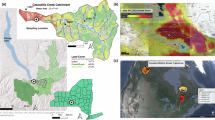

Our current understanding of the propagation of post-fire hydrologic impacts, such as those produced by the HPCC wildfire, is limited by the availability of longitudinal observations. In Ball et al.1, we proposed a simple model to predict the longitudinal extent of stream + river length impacted by wildfire disturbances downstream of a burned area (\(S{L}_{{LE}}\)). Briefly, \(S{L}_{{LE}}={\bar{L}}_{{\omega }_{0}}(1-{R}_{L}^{w})/(1-{R}_{L})\), where the length ratio \({R}_{L}=\bar{L}\left(\omega+1\right)/\bar{L}\left(\omega \right)\) follows predictable scaling patterns, i.e., 1.5 < \({R}_{L}\) < 3.5, \({\omega }_{0}\) is the lower stream order affected, and \(\bar{L}\left(\omega \right)\) is the arithmetic average of the length of streams of order \(\omega\). We applied \(S{L}_{{LE}}\) to the 2011 Las Conchas wildfire dataset presented in ref. 14, which burned first-order streams \(({\omega }_{0}=1)\) with \({\bar{L}}_{1}\)~1.3 km, to predict that a major downstream river, the Rio Grande, would still be affected where it was an 8th-order stream, assuming the average value recommended of \({R}_{L}\) = 2. From our data-limited analysis, we proposed that \(S{L}_{{LE}}\) conservatively should be about equal to the stream length impacted within burned areas \((S{L}_{{{\rm{BA}}}})\)1.

From the 2022 HPCC wildfire dataset, we know that wildfire disturbances that were generated in headwater streams with \({\bar{L}}_{1}\)~0.6 km propagated along the 5th-order stream reach where P5167 is located and further into Santa Rosa Lake (Fig. 1), suggesting that \(S{L}_{{LE}}\)~180 km. Because Santa Rosa Lake released water for only 19 days during the study period, it became predominantly a net sink of HPCC wildfire disturbances. In the lake, particulate material sank due to large-scale sedimentation and localized biochemical reactions, both of which reset solute signals80. While this disturbance propagation can be predicted with our \(S{L}_{{LE}}\) equation when 3.0 < \({R}_{L}\) < 3.5, smaller \({R}_{L}\) values would consistently overestimate the stream order to which the disturbances propagate, suggesting that higher \({R}_{L}\) values are better predictors in arid watersheds, where losing conditions impact the longitudinal propagation of disturbances analogously to having longer segments between stream orders. This overestimation is expected since Horton’s original equation predicts the uninterrupted growth of stream orders and flows, an assumption that seldom holds true in arid watersheds due to intermittent or non-perennial river segments, which interrupt the spatial and temporal connectivity along arid fluvial networks43,81,82,83. Interestingly, the stream length directly impacted within the Gallinas and Sapello watersheds (\(S{L}_{{{\rm{BA}}}-{Gallinas}}=\) 223 km and \(S{L}_{{{\rm{BA}}}-{Sapello}}\) = 197 km) closely agree with the longitudinal extent of the stream + river length impacted (\(S{L}_{{LE}}\)) observed in each network. Therefore, \(S{L}_{{LE}} \sim S{L}_{{BA}}\), an easy-to-estimate predictor presented in ref. 1, proved to be reliable.

While we observed increases in runoff near the burn perimeter in response to average rainfall events post-fire (Fig. 2), we also observed considerable attenuation of the water volumes reaching the confluence with the Pecos River (i.e., ~29% of the median runoff at P226 remained at P4136, Fig. 3). These predominantly losing conditions restricted the longitudinal propagation of water quality disturbances from Gallinas Creek into the Pecos River, particularly during the periods when Gallinas Creek became non-perennial. Additionally, our flow analysis at P4136 and P5167 suggests that most of the runoff seen at P5167 is unrelated to P4136, indicating that most wildfire disturbances reaching Santa Rosa Lake originated along, and propagated through, the mainstem of the perennial Pecos River.

Besides changes in water volumes along Gallinas Creek, wavelet coherence decreased with distance downstream (Fig. 7) due to the lack of additional sources and the longitudinal attenuation caused by advection, dispersion, transient storage, and decay processes84,85,86,87. Runoff events were not uniquely coupled with water quality disturbances (Fig. S4A), indicating the importance of antecedent conditions in determining when and where high-flow events result in high-mobilization events and the occurrence of hysteresis58,88,89. Previous studies have also shown that post-fire water, sediment, and solute fluxes can be strongly decoupled14,49,90,91 due to differences in the size and residence times of the various hydrologic compartments involved (e.g., hillslopes, main channel, groundwater), resulting in asynchronous activation thresholds and intermittent connectivity between terrestrial and aquatic subsystems.

Even though the presence of high turbidity and organics in Gallinas Creek forced the city of Las Vegas, NM, to halt its use as the primary source of potable water (intake located near P226) and led to large-scale and restricted use of bottled water in the region and the installation of a two-million-dollar filtration system92, the longitudinal propagation of wildfire disturbances from the HPCC gigafire after the first rainy season was highly attenuated by the average rainfall falling in the region, the net losing conditions that prevail in the mostly arid lands downstream of the burn scar, and the presence of large-scale reservoirs. In this arid land river network with numerous intermittent stream segments, solutes infiltrated groundwater compartments, and sediments and particulates were deposited in channels, moderating the effects of the fire as propagation occurred (Fig. S2). Therefore, our findings highlight the spatial and temporal co-dependency among atmospheric, terrestrial, and aquatic processes in defining the net outcome of wildfire disturbance propagation along impacted fluvial networks.

To date, most data post-fire have been collected in reaches within or near burned areas12,26,55, but this and other studies continue to emphasize the need to implement new methods that are appropriate to study larger systems and allow the collection and integration of data across spatial dimensions of connectivity37,93,94,95,96, evaluate processes across spatial and temporal scales57,97,98,99, and account from the perspectives of multiple disciplines to generate more holistic mitigation and restoration plans to address watershed-scale impacts to human and ecosystem health96,100,101,102,103.

Methods

Study site descriptions

The Hermit’s Peak wildfire began on April 6, 2022, after a prescribed burn on the Santa Fe National Forest became out of control due to high winds in the region. The Calf Canyon Fire was declared a wildfire on April 19, 2022, after a dormant pile burn holdover from a prescribed burn in January 2022 reemerged. The Hermit’s Peak and Calf Canyon wildfires merged on April 23, 2022. Strong winds quickly spread the fire to cover 600 km2 within a month, when it was only 20% contained104. The fire grew to over 1200 km2 and became a gigafire after 2 months, when it was 70% contained around June 15, 2022. The seasonal rain from the Monsoon slowed the HPCC, which became fully contained on August 21, almost 5 months after it began. Our rapid response team37 studied two fluvial networks affected by the HPCC gigafire, which we summarize below. Site characteristics for each subwatershed studied are detailed in Fig. S7 and Table S2. The flow in the streams and rivers of these fluvial networks is associated with groundwater baseflow in the winter, groundwater baseflow and snowmelt in the spring, and monsoonal storms in the summer and fall105.

Gallinas Creek-Pecos River fluvial network

The main stem of Gallinas Creek flows ~142 km before joining the Pecos River (Fig. 1). The Pecos River flows into Santa Rosa Lake, located ~180 km from the headwaters of Gallinas Creek. Santa Rosa Lake is operated by the US Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) for flood control, irrigation, recreation, and sediment retention. Most of the HPCC gigafire occurred upstream of P226. There are water quantity and quality data pre- and post-fire at P226 because, near it, Gallinas Creek is used for drinking water supply to ~13,000 people in the city of Las Vegas, NM.

Sapello–Mora–Canadian Rivers fluvial network

The Sapello River is a major tributary of the Mora River, and both join ~64 km from the Sapello’s headwaters (Fig. 1). The confluence between the Mora and Canadian Rivers is ~119 km from the headwaters. The Canadian River flows into Conchas Lake, located ~183 km from the headwaters of the Sapello River. Conchas Lake is operated by the USACE for flood control, irrigation, recreation, and sediment retention. Most of the HPCC gigafire occurred upstream of C129. Unlike Gallinas Creek, Sapello River did not have flow gaging stations due to the lack of widespread use of that river for human consumption.

Monitoring description

Discharge data

Discharge and stage data were collected at 5 and 15-min intervals at stream gages maintained by the USGS (Nos. 08380400, 08380500, 08382000, 08382500, 08382650, and 07221500) collocated or proximal to sonde sites P120, P226, P361, P4136, P5167, and C3178, respectively106. Discharge at P120 was estimated using a 2-h lagged relationship between gage heights from USGS gages 08380400 and 08380500. Discharge at C129 was estimated using a historical comparison of 08380500 and the legacy USGS gage 07220000 to compute an average coefficient of 0.79 for instantaneous discharge at C129 compared to P120. We estimated discharge at C286 using a historical comparison of USGS gages 07216500 and 07221000 and water quality parameters to calculate a mean travel time of 22 h from USGS gage 07216500 to C286. Because the Sapello River is a major tributary to the Mora River and a primary focus of this study, we estimated a 60% attenuation of peak discharge from C129 to C286 based on differences in peak flow from P120 to P226. We then used water quality parameters to calculate a mean travel time from C129 to C286 of 33 h and added the estimated discharge contribution from the Sapello River to time-corrected instantaneous discharge estimates of the Mora River from 07216500 at C286.

Meteorological data

Rainfall data were collected at 5-min intervals at gages maintained by the USGS (Nos. 08379990, 08380040, 08380070, 08380088, 08380400, 354142105184301, 354150105275301, and 354633105323601). Air Pressure and shortwave radiation were obtained for each site from gridded datasets at 1-h intervals and 0.125° spatial resolution from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) North American Land Data Assimilation System (NLDAS)107,108. Meteorological data were exported from MesoWest at climate stations LVPN5, TR931, NMC06, and NMC08 at 10-min intervals109.

Data quality control, assurance, and conversions

Raw and converted data were processed for outliers and sensor drift with Aquarius Timeseries 21.1 (Aquatic Informatics, Vancouver, Canada). Erroneous outliers were eliminated using a moving average filter targeting points deviating more than 20% from a 2-h moving window. We corrected sensor drift and biofouling by comparing pre- and post-cleaning and calibration values and applied a linear correction from the date of the previous maintenance110. Lastly, we performed a final visual inspection of data quality.

A high discharge event on September 10th, 2022, damaged the sonde at the P120 monitoring site, effectively terminating data collection on August 28th, 2022. At P361, sensor connectivity issues halted data recording from June 20th to July 11th, 2022. Starting September 4th, 2022, the DO sensor at P5167 was damaged, producing negative values, and was excluded from the analysis. Also, at P5167, there were periods with data removed because the sonde was buried or out of the water column.

fDOM was corrected for changes in water temperature and turbidity using the following equations111:

where \({{{\rm{fDOM}}}}_{{{\rm{temp}}}}\) is the temperature corrected fDOM concentration (QSU); \({{{\rm{fDOM}}}}\) is the uncorrected fDOM concentration (QSU); \(\rho\) is temperature-specific fluorescence coefficient of \(-7.545 \times {10}^{-3}\circ \; {{{\rm{C}}}}^{-1}\); \({W}_{T}\) is the water temperature (°C); \({T}_{l}\) is the lab temperature of 22 °C when fDOM was calibrated; \({{{{\rm{fDOM}}}}}_{{{{\rm{cor}}}}}\) is the temperature and turbidity corrected fDOM concentration (QSU); \({turb}\) is the water turbidity (FNU); \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) are turbidity correction coefficients of 0.38901, 0.72842, and −0.00618 when turbidity is <600 FNU, or 0.17573, 0.25597, and −0.00038 when turbidity is >600 FNU44.

Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) was derived by multiplying total downwelling shortwave radiation by a factor of 2.11112. Hydraulic geometry coefficients for estimating stream depth and velocity at each site were developed based on the analysis of instantaneous cross-sectional area and discharge measurements at each USGS discharge station. Depth and velocity were derived using power-law relationships relating cross-sectional areas and stream widths.

Enhanced vegetation index

EVI data were obtained for 2007–2022 from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Terra (MOD13Q1) and Aqua (MYD13Q1) Version 6.1. EVI was developed to optimize the vegetation signal with improved sensitivity to canopy-soil variation when compared with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration-Advanced Very High-Resolution Radiometer (NOAA-AVHRR) derived NDVI40,113:

where \(\rho\) are atmospherically corrected or partially atmosphere corrected (Rayleigh and ozone absorption) surface reflectances, \(L\) is the canopy background adjustment that addresses nonlinear, differential NIR and red radiant transfer through a canopy, and \({C}_{1}\) and \({C}_{2}\) are the coefficients of the aerosol resistance term, which uses the blue band to correct for aerosol influences in the red band. The coefficients adopted in the EVI algorithm are, \(L\) = 1, \({C}_{1}\) = 6, \({C}_{2}\) = 7.5, and \(G\) = 2.5, which is a gain factor that adjusts the EVI dynamic range to a range comparable to NDVI. Data are generated every 16 days based on the best available pixel from the acquisition period at a 250 m special resolution, and because the Terra and Aqua EVI algorithms are phased to generate each 16-day composite 8 days apart, both data records were combined for better temporal resolution.

We obtained shapefiles from StreamStats39 and used them separately to mask the EVI rasters to characterize the vegetation dynamics from within the burned portions of the Gallinas and Sapello watersheds. We rounded dates to the nearest 8-day interval for calendar year 2022 to compare accurately between years. We then calculated the 15-year pre-fire mean value and standard deviations for each date within the watershed boundaries for 2007–2021. These values were then compared with a time series for the mean values within each watershed in 2022 pre- (Jan 1-Apr 7) and post-fire (Apr 15-Dec 27).

HEC-HMS flow routing model

In 2022, the USACE completed a hydrologic assessment for Gallinas Creek to provide peak flow estimates for the increased flood risk following the HPCC wildfire41. Hydrologic Unit Code 12 basins for the watersheds were used to define the study area with the 3D Elevation Program database and add 10-m resolution digital elevation models in HEC-HMS (version 4.10, beta 8). Basin models use the Soil Conservation Service Curve Number (SCS-CN) loss method, which is a popular and practical method used for computing surface runoff in small watersheds. The method is simple, easy to conceptualize and apply, stable, and has shown good prediction results as it considers soil type, land use and cover, and antecedent soil moisture conditions114. However, this method was developed with data from agricultural watersheds in the midwestern USA and does not consider the dynamics of rainfall intensity and assumes that the infiltration rate approaches zero instead of keeping a constant rate. The initial SCS-CN for each subbasin was estimated using the 2019 National Land Cover Database (NLCD) and hydrologic soil group from the 2021 Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS’s) Soil Survey Geographic Database (SSURGO).

Rainfall frequency grids were generated from NOAA Atlas 14 and used to perform frequency analysis for events with different AEP: 50, 20, 10, 4, 2, and 1%. The HEC-HMS models were then calibrated based on adjusting the basin loss (SCS-CN) values, transform parameters (lag time), and peak rate factor using USGS Gage 08280500 Gallinas Creek near Montezuma, NM (P226) as a calibration point. Post-fire hydrology (peak flow) models were then estimated by modifying SCS-CNs (and lag times) to reflect post-fire conditions based on an evaluation following the 2005 Cerro Grande Fire in New Mexico, which related pre- and post-fire SCS-CN ratios to burn severity area using a wildfire hydrologic impact (WHI) factor42. That method defines WHI factors to modify SCS-CN ratios pre-fire as a function of the percentages of the subbasin with high or moderate severities calculated through GIS.

We created a meteorological model for the basin by assigning each subbasin within the HEC-HMS models to the nearest rainfall gage with data for the analysis period. Since the SCS-CN loss method does not include a means for extracting infiltrated water, the models were limited to individual event simulations. We identified three events in 2022 with at least 24 h of separation between rainfall-runoff events (07/09, 08/03, and 09/10) and used the meteorological model to simulate response curves at USGS Gages 08379990 with control specifications beginning at 10:00 a.m. the day of the observed peak-runoff and ending at 10:00 a.m. the following day to account for the modeled recession curve to return to baseflow without influence from rainfall on the preceding or next days (Fig. 2C). We selected the observed instantaneous discharge value immediately preceding the rising limb for each event as baseflow (0.84 m3s−1 for July, 1.76 m3s−1 for August, and 0.59 m3s−1 for September). Because the observed rainfall was <50% AEP (NOAA Atlas 14) for all observation gages, and the pre-fire peak discharge results were also <50% AEP (via Streamstats102), we selected the 50% AEP basin model for pre- and post-fire comparison to observed flow for all three events.

Historical discrete water quality data and pre-fire–post-fire comparisons

Historical water quality data were available at P226 through monitoring done by the USGS New Mexico Water Science Center. The data included discrete samples for SSD (i.e., suspended sediment concentration (SSC) multiplied by discharge), turbidity, and nitrate. SSD data were collected from June 1987 to September 1990 (19 samples, pre-fire) and between June and September 2022 (10 samples, post-fire). Turbidity data were available between May 1988 and September 1989 (10 samples, pre-fire) and between June and October 2022 (10 samples, post-fire). Pre-fire turbidity data were reported in Jackson Turbidity Units (JTU) and post-fire data in NTRU. However, both unit systems are roughly equivalent and were used interchangeably115. Nitrate data were available between March 1964 and June 1967 (16 samples, pre-fire) and between July 2022 and October 2022 (9 samples, post-fire). Those data were retrieved from the online water monitoring report How’s My Waterway, hosted by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). We used the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U statistical test to determine significant differences between pre- and post-fire discrete data since our populations had varying sizes116,117.

Estimates of stream metabolism

Stream metabolism modeling

We estimated daily averages of stream metabolism with the USGS streamMetabolizer model118, which uses a one‐station model based on the open‐channel metabolism approach119 and incorporates inverse Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo modeling. The equations used in streamMetabolizer are:

where \({{DO}}_{t}\) is the observed dissolved oxygen (\({{{\rm{mg}}}}{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{-1}\)) at time \(t\); \({{DO}}_{{{\mathrm{sat}}},t}\) is the hypothetical saturated DO concentration (\({{{\rm{mg}}}}{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{-1}\)); \({{{\mathrm{DO}}}}_{{{\mathrm{mod}}},t}\) is the modeled DO concentration \(({{{\rm{mg}}}}{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{-1});{\varepsilon }_{\begin{array}{c}{{obs}}\\ \end{array}}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{\begin{array}{c}{{proc}}\\ \end{array}}\) are the observation and processes error; t0 and t1 are the beginning and end of the day (\({{{\rm{d}}}}\)); \({Z}_{t}\) is stage (\({{{\rm{m}}}}\)); \({{PPFD}}_{t}\) is photosynthetic photon flux density (µ\({{{\rm{mol}}}}{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-2}\) \({{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{-1}\)); \({T}_{t}\) is the water temperature (°C); \({S}_{A,B,C,D}\) are dimensionless Schmidt coefficients (−); \({{GPP}}\) is the daily average areal rate of GPP (\({{{\rm{g}}}}{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{2}{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-2}{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{-1}\)); \({{ER}}\) is the daily average areal rate of ER (\({{{\rm{g}}}}{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{2}{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-2}{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{-1}\)); and \({K}_{600}\) is the standardized gas exchange rate coefficient \(({{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{-1}).\)

Stream metabolic fingerprints

We used the stream metabolic fingerprint technique45 to compare stream metabolism patterns across periods of analysis and monitoring sites. This technique analyzes GPP and ER kernel distributions to qualitatively compare metabolic regimes in response to changing site conditions and pulse events. We derived GPP and ER kernel distributions using the R package MASS’s kde2d function at a bandwidth of 7.5. The kde2d function is a non-parametric representation of the probability density function that is useful when data do not fall within a Gaussian distribution120.

Principal component and multi-comparison analysis

We used Matlab’s pca function to generate PCA and examine relationships between water quality parameters and stream metabolism estimates. The first two principal components were used for statistical analysis since they explained >60% of the total variance at each sonde site. We plotted the first two principal components in a biplot. Parameters aligned in the same direction represent positive correlations, those in opposite directions represent negative correlations, and those orthogonal are uncorrelated121. We also categorized the latent space daily points in each period of analysis by color to understand their dominance. Daily mean water quality values were derived to align with the timestep of stream metabolism estimates. Lastly, we standardized each parameter’s daily average by centering its mean at zero and scaling by its standard deviation to make parameters with varying magnitudes and units comparable:

where \({{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{X}\) is the standardized parameter \(X\) (−), and \({{{{\rm{\mu }}}}}_{X}\) and \({{{{\rm{\sigma }}}}}_{X}\) are the mean and standard deviation of parameter \(X\).

Wavelet coherence analysis

Wavelet coherence analyzes coherence, or localized correlation coefficients, between two-time series in the time–frequency domain using a continuous wavelet transformation47. This approach helps interpret inter-variable relationships in environmental datasets122,123, e.g., discharge and water quality parameters, as it can simultaneously explore lag or lead relationships without dataset manipulations. In this study focused on longitudinal propagation, we explored sub-daily frequencies, which we interpret as temporal synchrony of upstream and downstream sites not associated with diel patterns and, therefore, associated with shorter term disturbances (i.e., storm events). We used the WaveletCompR package47 to conduct wavelet coherence analysis based on a Morlet wavelet for DO, pH, SpCond, temperature, and turbidity at pairs of sites along the fluvial network to examine when water quality and runoff events are correlated. We removed periods ≥24 h to remove diurnal patterns, and interpret coherence across periods <24 h between parameters as longitudinal connectivity between monitoring sites.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during this study are available in the repository published by Nichols et al.124.

References

Ball, G., Regier, P., González-Pinzón, R., Reale, J. & Van Horn, D. Wildfires increasingly impact western US fluvial networks. Nat. Commun. 12, 2484 (2021).

Flannigan, M. D., Krawchuk, M. A., Groot, W. J., de, Wotton, B. M. & Gowman, L. M. Implications of changing climate for global wildland fire. Int. J. Wildland Fire 18, 483–507 (2009).

Westerling, A. L. Increasing western US forest wildfire activity: sensitivity to changes in the timing of spring. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150178 (2016).

Cayan, D. R., Kammerdiener, S. A., Dettinger, M. D., Caprio, J. M. & Peterson, D. H. Changes in the onset of spring in the western United States. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 82, 399–416 (2001).

Stewart, I. T., Cayan, D. R. & Dettinger, M. D. Changes in snowmelt runoff timing in western North America under a ‘Business as Usual’ climate change scenario. Clim. Change 62, 217–232 (2004).

Westerling, A. L., Hidalgo, H. G., Cayan, D. R. & Swetnam, T. W. Warming and earlier spring increase western U.S. forest wildfire activity. Science 313, 940–943 (2006).

Seager, R. et al. Model projections of an imminent transition to a more arid climate in southwestern North America. Science 316, 1181–1184 (2007).

Rao, K., Williams, A. P., Diffenbaugh, N. S., Yebra, M. & Konings, A. G. Plant-water sensitivity regulates wildfire vulnerability. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 332–339 (2022).

MacDonald, L. H. & Huffman, E. L. Post-fire soil water repellency. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 68, 1729–1734 (2004).

Larsen, I. J. et al. Causes of post-fire runoff and erosion: water repellency, cover, or soil sealing?. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 73, 1393–1407 (2009).

Moody, J. A. & Ebel, B. A. Hyper-dry conditions provide new insights into the cause of extreme floods after wildfire. Catena 93, 58–63 (2012).

Paul, M. J. et al. Wildfire induces changes in receiving waters: a review with considerations for water quality management. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR030699 (2022).

Brogan, D. J., Nelson, P. A. & MacDonald, L. H. Reconstructing extreme post‐wildfire floods: a comparison of convective and mesoscale events. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 42, 2505–2522 (2017).

Dahm, C. N., Candelaria-Ley, R. I., Reale, C. S., Reale, J. K. & Van Horn, D. J. Extreme water quality degradation following a catastrophic forest fire. Freshw. Biol. 60, 2584–2599 (2015).

Emmerton, C. A. et al. Severe western Canadian wildfire affects water quality even at large basin scales. Water Res. 183, 116071 (2020).

Mast, M. A., Murphy, S. F., Clow, D. W., Penn, C. A. & Sexstone, G. A. Water-quality response to a high-elevation wildfire in the Colorado Front Range. Hydrol. Process. 30, 1811–1823 (2016).

Reale, J. K., Van Horn, D. J., Condon, K. E. & Dahm, C. N. The effects of catastrophic wildfire on water quality along a river continuum. Freshw. Sci. 34, 1426–1442 (2015).

Rhoades, C. C., Nunes, J. P., Silins, U. & Doerr, S. H. The influence of wildfire on water quality and watershed processes: new insights and remaining challenges. Int. J. Wildland Fire 28, 721 (2019).

Rhoades, C. C. et al. The legacy of a severe wildfire on stream nitrogen and carbon in headwater catchments. Ecosystems https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-018-0293-6 (2018).

Rust, A. J., Saxe, S., Mccray, J., Rhoades, C. C. & Hogue, T. S. Evaluating the factors responsible for post-fire water quality response in forests of the western USA. Int. J. Wildland Fire 28, 769–784 (2019).

Santos, F. et al. Fire severity, time since fire, and site-level characteristics influence streamwater chemistry at baseflow conditions in catchments of the Sierra Nevada, California, USA. Fire Ecol. 15, 3 (2019).

Shakesby, R. A. & Doerr, S. H. Wildfire as a hydrological and geomorphological agent. Earth Sci. Rev. 74, 269–307 (2006).

Rust, A. J., Hogue, T. S., Saxe, S. & McCray, J. Post-fire water-quality response in the western United States. Int. J. Wildland Fire 27, 203–216 (2018).

Chen, J. & Chang, H. A review of wildfire impacts on stream temperature and turbidity across scales. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 47, 369–394 (2023).

Hohner, A. K., Rhoades, C. C., Wilkerson, P. & Rosario-Ortiz, F. L. Wildfires alter forest watersheds and threaten drinking water quality. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 1234–1244 (2019).

Raoelison, O. D. et al. Wildfire impacts on surface water quality parameters: cause of data variability and reporting needs. Environ. Pollut. 317, 120713 (2023).

Hampton, T. B., Lin, S. & Basu, N. B. Forest fire effects on stream water quality at continental scales: a meta-analysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 064003 (2022).

Rhea, A. E., Covino, T. P. & Rhoades, C. C. Reduced N-limitation and increased in-stream productivity of autotrophic biofilms 5 and 15 years after severe wildfire. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 126, e2020JG006095 (2021).

Rhoades, C. C. et al. The legacy of a severe wildfire on stream nitrogen and carbon in headwater catchments. Ecosystems 22, 643–657 (2019).

USGS circular 1350: nutrients in the nation’s streams and groundwater, 1992–2004. https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1350/.

Bladon, K. D., Emelko, M. B., Silins, U. & Stone, M. Wildfire and the future of water supply. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 8936–8943 (2014).

Adams, M. A. Mega-fires, tipping points and ecosystem services: managing forests and woodlands in an uncertain future. Ecol. Manag. 294, 250–261 (2013).

Calkin, D. E., Thompson, M. P. & Finney, M. A. Negative consequences of positive feedbacks in US wildfire management. For. Ecosyst. 2, 9 (2015).

North, M. P. et al. Reform forest fire management. Science 349, 1280–1281 (2015).

Westerling, A. L. et al. Climate change and growth scenarios for California wildfire. Clim. Change 109, 445–463 (2011).

Abatzoglou, J. T. & Williams, A. P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11770–11775 (2016).

Tunby, P. et al. Development of a general protocol for rapid response research on water quality disturbances and its application for monitoring the largest wildfire recorded in New Mexico, USA. Front. Water 5, 1223338 (2023).

Linley, G. D. et al. What do you mean, ‘megafire’? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 31, 1906–1922 (2022).

USGS. StreamStats. https://streamstats.usgs.gov/ss/.

Ba, R., Song, W., Lovallo, M., Zhang, H. & Telesca, L. Informational analysis of MODIS NDVI and EVI time series of sites affected and unaffected by wildfires. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 604, 127911 (2022).

AuBuchon, J. et al. Racing the Rain: A Post-Wildfire Case Study in Northern NM (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2023).

Livingston, R. K., Earles, T. A. & Wright, K. R. Los Alamos post-fire watershed recovery: a curve-number-based evaluation. 1–11 https://doi.org/10.1061/40763(178)41 (2012).

Datry, T. et al. Non-perennial segments in river networks. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 815–830 (2023).

Regier, P. J. et al. Water quality impacts of urban and non-urban arid-land runoff on the Rio Grande. Sci. Total Environ. 729, 138443 (2020).

Bernhardt, E. S. et al. The metabolic regimes of flowing waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 63, S99-S118 (2018).

Sang, Y.-F. A review on the applications of wavelet transform in hydrology time series analysis. Atmos. Res. 122, 8–15 (2013).

Rosch, A. & Schmidbauer, H. WaveletComp: Computational Wavelet Analysis. R package version 1.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=WaveletComp (2018).

Murphy, S. F., Writer, J. H., McCleskey, R. B. & Martin, D. A. The role of precipitation type, intensity, and spatial distribution in source water quality after wildfire. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 084007 (2015).

Bixby, R. J. et al. Fire effects on aquatic ecosystems: an assessment of the current state of the science. Freshw. Sci. 34, 1340–1350 (2015).

Mayor, A. G., Bautista, S., Llovet, J. & Bellot, J. Post-fire hydrological and erosional responses of a Mediterranean landscpe: seven years of catchment-scale dynamics. Catena 1, 68–75 (2007).

Hislop, S. et al. Using Landsat spectral indices in time-series to assess wildfire disturbance and recovery. Remote Sens. 10, 460 (2018).

Coombs, J. S. & Melack, J. M. Initial impacts of a wildfire on hydrology and suspended sediment and nutrient export in California chaparral watersheds. Hydrol. Process. 27, 3842–3851 (2013).

Murphy, S. F., McCleskey, R. B., Martin, D. A., Writer, J. H. & Ebel, B. A. Fire, flood, and drought: extreme climate events alter flow paths and stream chemistry. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 123, 2513–2526 (2018).

Moody, J. A. & Martin, D. A. Initial hydrologic and geomorphic response following a wildfire in the Colorado Front Range. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 26, 22 (2001).

Smith, H. G., Sheridan, G. J., Lane, P. N. J., Nyman, P. & Haydon, S. Wildfire effects on water quality in forest catchments: a review with implications for water supply. J. Hydrol. 396, 170–192 (2011).

Yu, M., Bishop, T. F. A. & Van Ogtrop, F. F. Assessment of the decadal impact of wildfire on water quality in forested catchments. Water 11, 533 (2019).

Kinoshita, A. M. & Hogue, T. S. Spatial and temporal controls on post-fire hydrologic recovery in Southern California watersheds. Catena 87, 240–252 (2011).

Doerr, S. H. et al. Effects of differing wildfire severities on soil wettability and implications for hydrological response. J. Hydrol. 319, 295–311 (2006).

DeBano, L. F. The role of fire and soil heating on water repellency in wildland environments: a review. J. Hydrol. 231–232, 195–206 (2000).

Humagain, K., Portillo-Quintero, C., Cox, R. D. & Cain, J. W. Mapping tree density in forests of the southwestern USA using Landsat 8 data. Forests 8, 287 (2017).

Saxe, S., Hogue, T. S. & Hay, L. Characterization and evaluation of controls on post-fire streamflow response across western US watersheds. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 1221–1237 (2018).

Lanini, J. S., Clark, E. A. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Effects of fire-precipitation timing and regime on post-fire sediment delivery in Pacific Northwest forests. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L01402 (2009).

Johansen, M. P., Hakonson, T. E. & Breshears, D. D. Post-fire runoff and erosion from rainfall simulation: contrasting forests with shrublands and grasslands. Hydrol. Process. 15, 2953–2965 (2001).

Moody, J. A. & Martin, D. A. Post-fire, rainfall intensity–peak discharge relations for three mountainous watersheds in the western USA. Hydrol. Process. 15, 2981–2993 (2001).

Holliday, C., Rasmussen, T. C. & Miller, W. P. Establishing the Relationship Between Turbidity and Total Suspended Sediment Concentration (Georgia Institute of Technology, 2003).

Lee, E.-J. et al. Comparison of UV–VIS and FDOM sensors for in situ monitoring of stream DOC concentrations. Biogeosciences 12, 3109–3118 (2015).

Jolly, I. D., McEwan, K. L. & Holland, K. L. A review of groundwater–surface water interactions in arid/semi-arid wetlands and the consequences of salinity for wetland ecology. Ecohydrology 1, 43–58 (2008).

Zeglin, L. H., Crenshaw, C. L., Dahm, C. N., Sheibley, R. W. & Takacs-Vesbach, C. D. Watershed hydrology and salinity, but not nutrient chemistry, are associated with arid-land stream microbial diversity. Freshw. Sci. 38, 77–91 (2019).

Herczeg, A. L., Dogramaci, S. S. & Leaney, F. W. J. Origin of dissolved salts in a large, semi-arid groundwater system: Murray Basin, Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 52, 41–52 (2001).

Gomez Isaza, D. F., Cramp, R. L. & Franklin, C. E. Fire and rain: a systematic review of the impacts of wildfire and associated runoff on aquatic fauna. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 2578–2595 (2022).

Bayley, S. E., Schindler, D. W., Parker, B. R., Stainton, M. P. & Beaty, K. G. Effects of forest fire and drought on acidity of a base-poor boreal forest stream: similarities between climatic warming and acidic precipitation. Biogeochemistry 17, 191–204 (1992).

Lydersen, E., Høgberget, R., Moreno, C. E., Garmo, Ø. A. & Hagen, P. C. The effects of wildfire on the water chemistry of dilute, acidic lakes in southern Norway. Biogeochemistry 119, 109–124 (2014).

Cavaiani, J. et al. Catchment characteristics modulate the influence of wildfires on nitrate and dissolved organic carbon across space and time: a meta-analysis. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.22541/essoar.171052482.22663736/v1 (2024).

Bernhardt, E. S. et al. Light and flow regimes regulate the metabolism of rivers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2121976119 (2022).

Tuckett, Q. M. & Koetsier, P. Mid- and long-term effects of wildfire and debris flows on stream ecosystem metabolism. Freshw. Sci. 35, 445–456 (2016).

Betts, E. F. & Jones, J. B. Impact of wildfire on stream nutrient chemistry and ecosystem metabolism in boreal forest catchments of interior Alaska. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 41, 407–417 (2009).

O’Donnell, B. & Hotchkiss, E. R. Resistance and resilience of stream metabolism to high flow disturbances. Biogeosciences 19, 1111–1134 (2022).

Atkinson, B. L., Grace, M. R., Hart, B. T. & Vanderkruk, K. E. N. Sediment instability affects the rate and location of primary production and respiration in a sand-bed stream. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 27, 581–592 (2008).

Reale, J. Evaluating the Effects of Catastrophic Wildfire on Water Quality, Whole-stream Metabolism and Fish Communities (The University of New Mexico, 2018).

Khandelwal, A., Castillo, T. & González-Pinzón, R. Development of The Navigator: a Lagrangian sensing system to characterize surface freshwater ecosystems. Water Res. 120577 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.120577 (2023).

Busch, M. H. et al. What’s in a name? Patterns, trends, and suggestions for defining non-perennial rivers and streams. Water 12, 1980 (2020).

Costigan, K. H. et al. Flow regimes in intermittent rivers and ephemeral streams. in Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams (eds Datry, T., Bonada, N. & Boulton, A.) Ch. 20.2, 51–78 (Academic Press, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803835-2.00003-6.

Datry, T., Larned, S. T. & Tockner, K. Intermittent rivers: a challenge for freshwater ecology. BioScience 64, 229–235 (2014).

Bencala, K. E. & Walters, R. A. Simulation of solute transport in a mountain pool-and-riffle stream: a transient storage model. Water Resour. Res. 19, 718–724 (1983).

Runkel, R. L. One-Dimensional Transport with Inflow and Storage (OTIS): A Solute Transport Model for Streams and Rivers (U.S. Geological Survey, 1998).

Briggs, M. A., Gooseff, M. N., Arp, C. D. & Baker, M. A. A method for estimating surface transient storage parameters for streams with concurrent hyporheic storage. Water Resour. Res. 45, W00D27 (2009).

González-Pinzón, R. & Haggerty, R. An efficient method to estimate processing rates in streams. Water Resour. Res. 49, 6096–6099 (2013).

Certini, G. Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: a review. Oecologia 143, 1–10 (2005).

Giovannini, G., Lucchesi, S. & Giachetti, M. The natural evolution of a burned soil: a three-year investigation. Soil Sci. 143, 220–226 (1987).

Hall, S. J. & Lombardozzi, D. Short-term effects of wildfire on montane stream ecosystems in the southern Rocky Mountains: one and two years post-burn. West. N. Am. Nat. 68, 453–462 (2008).

Emelko, M. B. et al. Sediment-phosphorus dynamics can shift aquatic ecology and cause downstream legacy effects after wildfire in large river systems. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 1168–1184 (2016).

Lohmann, P. Las Vegas Slowly Rebuilds Clean Water Supply, But Residents Worry About Long-term Future—Source New Mexico. https://sourcenm.com/2022/09/16/las-vegas-slowly-rebuilds-clean-water-supply-but-residents-worry-about-long-term-future/ (2022).

Lentile, L. et al. Lessons Learned From Rapid Response Research on wildland fires. Fire Management Today. 67, 24–31 (2007).

Gootman, K. S., González‐Pinzón, R., Knapp, J. L. A., Garayburu‐Caruso, V. & Cable, J. E. Spatiotemporal variability in transport and reactive processes across a first- to fifth-order fluvial network. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR026303 (2020).

Ward, A. S. et al. Spatial and temporal variation in river corridor exchange across a 5th-order mountain stream network. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 5199–5225 (2019).

Covino, T. Hydrologic connectivity as a framework for understanding biogeochemical flux through watersheds and along fluvial networks. Geomorphology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.09.030 (2016).

Harvey, J. & Gooseff, M. River corridor science: hydrologic exchange and ecological consequences from bedforms to basins. Water Resour. Res. 51, 6893–6922 (2015).

Ward, A. S. & Packman, A. I. Advancing our predictive understanding of river corridor exchange. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 6, e1327 (2019).

Brunner, P., Simmons, C. T. & Cook, P. G. Spatial and temporal aspects of the transition from connection to disconnection between rivers, lakes and groundwater. J. Hydrol. 376, 159–169 (2009).

Carone, M. T., Simoniello, T., Manfreda, S. & Caricato, G. Watershed influence on fluvial ecosystems: an integrated methodology for river water quality management. Environ. Monit. Assess. 152, 327–342 (2009).

Álvarez-Cabria, M., Barquín, J. & Peñas, F. J. Modelling the spatial and seasonal variability of water quality for entire river networks: relationships with natural and anthropogenic factors. Sci. Total Environ. 545–546, 152–162 (2016).

Yu, G.-A., Disse, M., Huang, H. Q., Yu, Y. & Li, Z. River network evolution and fluvial process responses to human activity in a hyper-arid environment – Case of the Tarim River in Northwest China. Catena 147, 96–109 (2016).

Maaß, A.-L., Schüttrumpf, H. & Lehmkuhl, F. Human impact on fluvial systems in Europe with special regard to today’s river restorations. Environ. Sci. Eur. 33, 119 (2021).

National Interagency Fire Center. InciWeb: Incident Information System. https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/ (2022).

Waltemeyer, S. D. Analysis of the Magnitude and Frequency of Peak Discharge and Maximum Observed Peak Discharge in New Mexico and Surrounding Areas. (U.S. Geological Survey, 2008).

U.S. Geological Survey. National Water Information System. USGS Water Data Nation (2022).

Mitchell, K. E. et al. The multi-institution North American Land Data Assimilation System (NLDAS): utilizing multiple GCIP products and partners in a continental distributed hydrological modeling system. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D07S90 (2004).

Xia, Y. et al. Continental-scale water and energy flux analysis and validation for the North American Land Data Assimilation System project phase 2 (NLDAS-2): 1. Intercomparison and application of model products. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117, D03109 (2012).

MesoWest data. https://mesowest.utah.edu/index.html. (accessed in 2022).

Wagner, R. J., Boulger, R. W. Jr., Oblinger, C. J. & Smith, B. A. Guidelines and Standard Procedures for Continuous Water-Quality Monitors: Station Operation, Record Computation, and Data Reporting http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/tm1D3 (2006).

Downing, B. D., Pellerin, B. A., Bergamaschi, B. A., Saraceno, J. F. & Kraus, T. E. C. Seeing the light: the effects of particles, dissolved materials, and temperature on in situ measurements of DOM fluorescence in rivers and streams: effects and compensation for in situ DOM fluorescence. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 10, 767–775 (2012).

Meek, D., Hatfield, J., Howell, T., Idso, S. & Reginato, R. A generalized relationship between photosynthetically active radiation and solar radiation1. Agron. J. 76, 939–945 (1984).

Huete, A. et al. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 195–213 (2002).

Mishra, S. K. & Singh, V. P. SCS-CN method. in Soil Conservation Service Curve Number (SCS-CN) Methodology (eds Mishra, S. K. & Singh, V. P.) 84–146 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-0147-1_2.

Bash, J., Berman, C. & Bolton, S. Effects of Turbidity and Suspended Solids on Salmonids (University of Washington Water Center, 2001).

Yue, S. & Wang, C. Y. Power of the Mann-Whitney test for detecting a shift in median or mean of hydro-meteorological data. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 16, 307–323 (2002).

Dorley, J. et al. Physical and stoichiometric controls on stream respiration in a headwater stream. Biogeosciences 20, 3353–3366 (2023).

Appling, A. P., Hall, R. O., Yackulic, C. B. & Arroita, M. Overcoming equifinality: leveraging long time series for stream metabolism estimation. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 123, 624–645 (2018).

Odum, H. T. Primary production in flowing waters1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1, 102–117 (1956).

Venables, W. & Ripley, B. D. Statistics and Computing: Modern Applied Statistics with S Vol. 1007, 978–0 (Springer-Verlag, 2002).

Jolliffe, I. T. & Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 374, 20150202 (2016).

Regier, P. et al. Biogeochemical control points of connectivity between a tidal creek and its floodplain. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 6, 134–142 (2021).

Webster, A. J., Douglas, T. A., Regier, P., Scheuerell, M. D. & Harms, T. K. Multi-scale temporal patterns in stream biogeochemistry indicate linked permafrost and ecological dynamics of boreal catchments. Ecosystems 25, 1189–1206 (2022).

Nichols, J. et al. Data archive: longitudinal propagation of aquatic disturbances following the largest wildfire recorded in New Mexico, USA. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.12762324 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The National Science Foundation funded this work through grants CBET 2054444 to R.G.P. and D.J.V.H., and HDR 1914490 and EAR 2142691 to R.G.P. USACE supported part of this research through internal funding to J.K.R. and Cooperative Agreement W912HZ-14-2-0014 to D.J.V.H. and R.G.P. Support for P.R. for manuscript development was provided by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research, as part of the Environmental System Science (ESS) Program. P.R.’s contribution originates from the River Corridors Science Focus Area at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). PNNL is operated for DOE by Battelle Memorial Institute under contract DE-AC05-76RL01830. The New Mexico Water Resources Research Institute also funded part of this research through faculty and student grants to R.G.P. and Asmita K. We thank Matthew Segura and Christopher McGibbon from USACE for assisting with the operation and maintenance of the sites above Santa Rosa and Conchas Lakes. We thank Lea Knutson and Conrad Greaves from the Hermit’s Peak Watershed Alliance for helping us secure site access to monitoring stations; Jennifer Aldred from New Mexico Highlands University for help setting up sensor stations; and the firefighters who saved lives and property during this devastating event. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.N. contributed to the conceptualization of the study, deployment and maintenance of sensors, data collection, data analysis, generation of figures and tables, writing, review, and editing. E.J., L.R., and P.R. contributed to the data analysis, generation of figures, writing, review, and editing. Asmita K., P.T., and Aashish K. contributed to the deployment and maintenance of sensors, data collection, data analysis, review, and editing. J.K.R. contributed to the writing, review, and editing of the manuscript. R.G.P. and D.V.H. conceptualized the study, secured funding, mentored students, led the deployment and maintenance of sensors, led the data analysis, and contributed to the writing, review, and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Erica Siirila-Woodburn and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information