Abstract

Wave interference between transient waves and climatological stationary waves is a useful framework for diagnosing the magnitude of stationary waves. Here, we find that the wave interference over the North Pacific Ocean is an important driver of North American wintertime cold and heavy precipitation extremes in the present climate, but that this relationship is projected to weaken under increasing greenhouse gas emissions. When daily circulation anomalies are in-phase with the climatological mean state, the anomalous transport of heat and moisture causes the enhanced occurrence of cold extremes across the continental U.S. and a significant decrease of heavy precipitation extremes in the western U.S. In a future emissions scenario, the climatological stationary wave over the eastern North Pacific weakens and shifts spatially, which alters and generally weakens the relationship between wave interference and North American climate extremes. Our results underscore that the prediction of changes in regional wave interference is pivotal for understanding the future regional climate variability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The occurrence of extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, droughts, and floods, has increased substantially since the pre-industrial period, but this trend has large regional variations1,2. An important driver of the regional climate variability is the zonally asymmetric atmospheric circulation, or stationary waves, forced by the zonal asymmetries in the Earth’s surface such as the land-sea thermal contrast and orography3,4,5,6. Because stationary waves regulate the poleward transport of heat and moisture7,8,9,10,11 and influence the storm track strength and location5,12,13, the projected stationary wave changes in response to increasing greenhouse gas concentrations have been highlighted as a key process for understanding how regional climate will be shaped in future warming scenarios14,15,16.

The causal relationship between change in the structure of stationary waves and regional climate variability in future climate has been explored by previous studies that analyzed a suite of comprehensive global climate models17,18,19,20. For instance, using simulations from Phase 5 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5), previous studies showed a projected increase in boreal winter precipitation over the west coast of North America due to an extension of the Pacific jet stream18 and stronger southerly winds associated with changes in the stationary waves21. In addition, the drying response over the Mediterranean Basin is linked to changes in the stationary wave structure over the North Atlantic19,21. Zonally symmetric forcing, on the other hand, plays a lesser role in driving the mean precipitation response over certain regions such as North America22.

Transient waves in midlatitudes can contribute to regional climate variability on intraseasonal time scales through their interference with climatological stationary waves. When transient waves, or daily atmospheric circulation anomalies in this study, are in-phase with the climatological stationary waves, they constructively interfere with each other and amplify the atmospheric circulation. Conversely, out-of-phase combinations of climatological stationary and transient waves result in destructive interference10,23,24,25. Therefore, wave interference provides a useful and simple measure of the magnitude of stationary waves on the daily time scale. It is most pronounced during boreal winter when extratropical stationary waves and the associated zonally asymmetric forcing are strongest23,26. Recent studies showed that the boreal wintertime wave interference is driven by poleward propagating Rossby waves excited by localized tropical convection, and they focused on understanding its linkage to the following Arctic temperature anomalies through enhanced poleward moisture and heat transport over the two oceanic basins10,23. They suggested that the magnitude of Arctic warming driven by those atmospheric circulation processes is reliant upon the zonal asymmetry in tropical diabatic forcing27. Wave interference also impacts regional climate through stratosphere-troposphere coupling, as interference enhances (constructive) or suppresses (destructive) the vertical propagation of planetary scale waves that influence the wintertime stratospheric polar vortex variability24,25,28,29. The anomalous strength of the polar vortex is linked to the Northern Annular Mode that impacts midlatitude circulation on hemispheric scales24,30,31.

A daily measure of wave interference can effectively quantify the daily state of enhanced or weakened stationary waves over the targeted region. Prior studies on the wave interference, however, have mainly investigated its causal linkage to the Arctic climate variability. Less focus has been placed on how the stationary-transient wave interference directly impacts the climate variability over North America and how the structure of wave interference will change in future projections, two topics with important socioeconomical implications. In light of the above, this study utilizes both observational data and the large ensemble of global climate model (GCM) simulations developed by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (NOAA GFDL) to address the following research questions:

-

(1)

How does the interference between the climatological stationary waves and transient eddies over the North Pacific Ocean impact North American temperature and precipitation extremes?

-

(2)

How does the structure and downstream impact of the North Pacific wave interference change in a future climate projection?

In the following analysis, we show that North Pacific wave interference is a useful diagnostic for estimating the magnitude of stationary waves therein, which is tightly linked to North American weather extremes through regulating heat and moisture advection, and that the spatial structure of these regional impacts is expected to change under a high greenhouse gas emissions scenario.

Results

Characteristics of North Pacific wave interference

We first focus on the characteristics of winter North Pacific stationary-transient wave interference and its relationship with North American weather extremes in reanalysis data. To identify wave interference events, we define a North Pacific stationary wave index (NP SWI) by projecting the daily 250-hPa streamfunction anomaly field onto the climatological stationary waves and normalizing the resultant time series, as in refs. 10,23 but only over the North Pacific domain (see “Methods”). This NP SWI provides a simple metric to identify days when the zonal asymmetry of the atmospheric circulation on a regional scale is anomalously enhanced or suppressed. We identify positive (constructive interference) NP SWI events as the temporal peaks that exceed the threshold value of 1.0 and are separated from each other by at least 10 days. Negative (destructive interference) events are defined in the same manner but for the threshold value of −1.0. As a result, 94 constructive interference events and 90 destructive interference events are identified during the boreal winters of 1979–2020.

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the upper-level circulation anomalies for the positive and negative NP SWI events. The constructive interference over the North Pacific at event peak is characterized by a quadrupole pattern—anticyclonic circulation anomalies centered at the Gulf of Alaska and western subtropical Pacific and cyclonic circulation anomalies centered at the northwestern North Pacific and the eastern subtropical Pacific (Fig. 1B), while anomalies of opposite sign are found for the destructive interference (Fig. 1E). The wave activity flux diagnostics reveal two important drivers of the Pacific wave interference: a Eurasian wave train and western tropical Pacific convection. As shown in the circulation fields for both interference phases (Fig. 1A, D), a prominent wave train over the Eurasian continent propagates to the North Pacific Ocean, interacting with the stationary waves 3 to 7 days prior to peak interference. Simultaneously, poleward propagating wave trains are excited from the central subtropical Pacific nearby the jet exit region, suggesting that localized tropical convection plays an important role in driving the wave interference10,23,30,32. In accordance with the decay of the Eurasian wave train and tropical convective activity, the North Pacific wave interference diminishes, and the wave train propagates further downstream 5 days later (Fig. 1C, F).

Pentad composites of 250-hPa streamfunction anomaly (shading; \({{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{2}\) \({{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\)) and wave activity flux (green vector; \({{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{2}\) \({{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-2}\)) averaged over (A, D) lag days −7 to −3, (B, E) −2 to +2, and (C, F) +3 to +7 for (A–C) (left) constructive interference events and (D–F) (right) destructive interference events. Stippling indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05) evaluated by Monte Carlo simulations. Variation in the western subtropical Pacific jet is represented by the 250-hPa zonal wind anomalies over the domain of 0–50°N and 120°E–150°W (solid black contours are positive and dashed black contours are negative; interval is 5 m \({{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\)). Purple boxes in the second row indicate the domain used in this study (140°E–120°W and 15°–75°N) to construct the North Pacific stationary wave index.

To further elucidate the relative contribution of planetary-scale and synoptic-scale waves in the evolution of wave interference, we decompose streamfunction anomaly fields into the planetary-scale and synoptic-scale counterparts by performing a Fourier transform (“Methods”). The result illustrates that throughout the growth and decay of constructive interference, the planetary-scale eddy contribution dominates, while synoptic-scale eddies play a relatively minor role (Fig. S1). By constructing the NP SWI with daily planetary-scale (or synoptic-scale) streamfunction anomalies projected onto the climatological stationary waves, we confirmed that planetary-scale eddy activity regulates the growth and decay in both phases of wave interference, while synoptic-scale eddy activity further amplifies this interference near its peak (Fig. S2). We therefore focus on identifying the sources of planetary-scale waves that are primarily involved in wave interference in the later subsection.

North American climate extremes associated with the North Pacific wave interference

Next, we demonstrate that North Pacific stationary-transient wave interference is a signature of a circulation pattern driving winter weather extremes over a large portion of North America. Figure 2 shows anomalous occurrences of cold and heavy precipitation extremes during interference events, where extremes are defined by the 5th and 95th percentiles of the climatological distributions (see “Methods”). Once wave interference reaches its peak, concurrent changes in the frequency of occurrence of cold extremes are detected mainly over Alaska and northwestern Canada, whereas the effects over most of the North American region are muted. In the next pentad, however, constructive interference brings a widespread and significant increase of cold extremes over the continental U.S. (CONUS). This increase is most pronounced over the southcentral U.S. (Fig. 2C) due to enhanced cold air advection with stronger northerly winds. These anomalous changes have opposite signs in the case of destructive interference (Fig. 2D).

Pentad composites of changes in the frequency of occurrence (%) relative to the climatological frequency of occurrence of (A–D) cold extremes (5th percentile of daily minimum temperature) and (E–H) heavy precipitation extremes (95th percentile of daily precipitation) averaged over (A, B, E, F) lag days −2 to +2, and (C, D, G, H) +3 to +7 for (A, C, E, G) (left) constructive interference events and (B, D, F, H) (right) destructive interference events. Stippling indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05) evaluated by Monte Carlo simulations. Boxes denote the domain of Alaska and western Canada (Red; 55°–70°N, 167.5°–107.5°W), western U.S. (Green; 30°–50°N, 126.25°–106.25°W), central U.S. (Yellow; 35°–55°N, 106.25°–86.25°W), and continental U.S. (Purple; 30°–50°N, 126.25°–66.25°W).

Although the relationship with heavy precipitation extremes is more complicated than that with temperature, wave interference is a major driver of heavy precipitation extremes over the western U.S. and Alaska. At the peak of constructive events, for example, the probability of heavy precipitation extremes is reduced over the west coast of the U.S., whereas Alaska and northwestern Canada experience increases of heavy precipitation extremes (Fig. 2E). In contrast, destructive interference results in more frequent occurrence of heavy precipitation extremes over the western U.S. (Fig. 2F). As anomalous moisture fluxes reach farther inland, the upper Midwest U.S. is more likely to experience precipitation extremes 3 to 7 days after destructive interference over the North Pacific. In opposition to the wetter continental U.S., the chance of heavy precipitation extremes over Alaska and northwestern Canada is reduced. This opposite relationship between the western U.S. and Alaska hydroclimate due to wave interference is similarly shown by a previous study of intense moisture transport modulated by upstream circulation anomalies33.

For a quantitative comparison of changes in occurrences, we examine the area-averaged changes over four different domains that are most strongly impacted by wave interference in the present climate—(1) Alaska and western Canada and (2) CONUS are chosen for quantifying cold extreme probabilities (Boxes in Fig. 2A, C), and (3) western U.S. and (4) central U.S. are chosen for quantifying heavy precipitation extreme probabilities (Boxes in Fig. 2E, H). The results are shown in Table S1. Consistent with Fig. 2, this table indicates that constructive interference significantly modulates the frequency of occurrences of cold extremes over the CONUS and heavy precipitation extremes over the western and central U.S., with regionally averaged extreme occurrences deviating from average by up to nearly 75% over a period of about a week.

To demonstrate that the impacts of wave interference are distinct from those of more commonly studied atmospheric circulation patterns, we compare the area-weighted CONUS-averaged changes in temperature extremes during wave interference events to those of the more familiar Northern Hemisphere teleconnection patterns: the Pacific-North American (PNA) pattern and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Perhaps surprisingly, the impact of wave interference on North American cold extremes is stronger than that of the most widely studied teleconnection patterns. For example, the frequency of occurrence of CONUS cold extremes is increased by 62.5% after constructive interference events (Fig. 2C), whereas the negative phase of NAO shows smaller increases (42.2%; Fig. S3C). Moreover, the PNA has a more modest influence on CONUS temperature extremes (−16.1% for the positive phase; Fig. S3B) than either wave interference or the NAO. We found that the negative phase of the PNA similarly exhibits a small influence over CONUS on average (e.g., 12.7%), in line with a previous finding34. Regarding heavy precipitation extremes, constructive interference considerably reduces the frequency of occurrence by 34.8% in the western U.S., which is a slightly smaller than the decrease by the positive PNA (−43.1%; Fig. S3D) but stronger than that by the negative NAO (−17.5%; Fig. S3E). To explore the relationship between the indices, we computed the Pearson correlations between their DJF-mean time series, as shown in Fig. S3F. We find that the NP SWI is not significantly correlated with the NAO (r = 0.21), but with the PNA (r = 0.31) due to some overlapping circulation anomalies over the North Pacific domain.

We additionally compare the wave interference patterns with the circulation patterns of the four North American weather regimes identified by cluster analysis35 to gain insight into their linkages. Among those regimes (i.e., the Pacific Trough, Pacific Ridge, Alaskan Ridge, and Greenland High regimes), the spatial pattern of constructive interference resembles that of the Alaskan ridge regime in that both patterns are characterized by an anomalous ridge over Alaska. However, they are also different from each other in that the Alaskan ridge is accompanied by an anomalous trough mostly confined to the Arctic Archipelago, whereas the constructive interference pattern shows anomalous trough with a northeast-southwest tilt that covers the continental U.S. and is connected to the eastern subtropical North Pacific anomalies (e.g., Fig. 1B). On the other hand, the spatial pattern of destructive interference resembles that of the Pacific Trough regime in that both patterns are characterized by an anomalous trough over the Gulf of Alaska and an anomalous ridge over the subtropical North Pacific. By counting the number of weather regimes during wave interference events, we found that the Alaskan ridge regime occurs most frequently during constructive interference events (42 out of 94 events), and the Pacific trough regime is most frequent during destructive interference events (35 out of 90 events). The frequencies of occurrence of the other regimes are approximately 20–30% during interference events, indicating that different flavors of North American weather regimes exist during wave interference.

To show how wave interference drives these changes in heavy precipitation extremes through changes in regional moisture transport, we display in Fig. 3 the vertically integrated moisture fluxes (black vectors) overlaid onto the mean sea level pressure (MSLP) anomalies (shading) during wave interference events. MSLP is examined because it depicts anomalous surface winds that divert moisture fluxes. The MSLP anomalies align well with the upper-level circulation anomalies denoted by variations of the 250-hPa streamfunction (black contours), depicting the equivalent-barotropic structure of the wintertime stationary waves3,16,21. Prior to the development of an anomalous ridge over the Gulf of Alaska, an anomalous trough is located over the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, accompanied by narrow moisture plumes directed toward the west coast of North America (Fig. 3A). Once the wave interference peaks, the direction of moisture flux vectors quickly shifts westward and poleward, creating a strong moisture transport corridor towards the Chukchi Sea (Fig. 3B). In the northwestern U.S., this suppression of moisture transport is sustained for the next 5 days (Fig. 3C). Thus, these anomalous moisture fluxes induce reduced heavy precipitation extremes over the U.S. west coast and increased precipitation extremes over Alaska and northwestern Canada (Fig. 2E, G). The destructive interference in general shows the opposite sequence with the enhanced moisture transport toward the U.S. west coast at the peak of interference (Fig. 3E, F), which collocates with the increased heavy precipitation extremes therein (Fig. 2F, H).

Pentad composites of mean sea level pressure (shading) and vertically integrated moisture flux (vector; kg \({{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-1}\) \({{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\)) anomalies averaged over (A, D) lag days −7 to −3, (B, E) −2 to +2, and (C, F) +3 to +7 for (A–C) (left) constructive interference events and (D–F) (right) destructive interference events. To aid visualization, the vectors smaller than 20 kg \({{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-1}\) \({{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\) are omitted. Stippling indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05) evaluated by Monte Carlo simulations. The corresponding composites of 250-hPa streamfunction anomalies are overlaid by green contours with an interval of \(2\times {10}^{6}\,{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{2}\) \({{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\).

Physical drivers of the North Pacific wave interference

To explain the evolution of the regional wave interference and the associated drivers in further detail, we show the Hovmöller diagram of tropical outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) anomalies, a proxy for atmospheric deep convection, and the line plots of several indices that represent potential drivers for or responses to constructive interference events (Fig. 4). Statistically significant negative OLR anomalies west of the date line indicate that tropical convection is enhanced over the western tropical Pacific at least 10 days before peak wave interference, while positive OLR anomalies east of the date line in tandem indicate suppressed convection over the central tropical Pacific (Fig. 4A). These results are consistent with stationary wave forcing by the enhanced zonal asymmetry in tropical convection. As it takes about 7 days for a Rossby wave train to propagate from the tropics to high latitudes36, the onset of the wave interference at lag day −4 matches well with the theoretical timing (Fig. 4B). The time scale of the North Pacific wave interference is about 10 days, based on its significant growth and decay of the composite SWI for all events (e-folding time scale of 3.8 days; Fig. 4B), which is consistent with other atmospheric teleconnection time scales37. Corresponding to the linearity in the wave interference, the opposite features are found for destructive interference (Fig. S4A).

A A Hovmöller diagram showing tropical outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) anomalies averaged over 15°S–15°N (shading) for constructive interference events from 20 days before (bottom) to 5 days after (top) peak interference. Black dashed lines indicate the longitudes of the western warm-pool (90°–150°E). Stippling indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05) evaluated by Monte Carlo simulations. B Lagged composite plots of the NP SWI (red), wave activity flux length over the Eurasian continent (30°–150°E and 15°–75°N, Eurasian wave train; purple), normalized transient eddy forcing (orange), the western warm-pool OLR anomalies (WP OLR; green), and 50-hPa zonal mean zonal wind anomalies (u50; pink) for constructive interference event days. Scaling has been applied to transient eddy forcing and warm-pool OLR anomalies for visualization. Black dots indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05) evaluated by Monte Carlo simulations.

The eastward propagation of the zonal dipole structure of tropical OLR anomalies raises the possibility that the Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO)38, a dominant mode of tropical variability on the intraseasonal time scale with a periodicity of about 30–70 days, is associated with this distinct eastward propagation. We investigate the relationship between the North Pacific wave interference and the MJO by constructing MJO space diagrams for the subsets of wave interferences based on the composites of the real-time multivariate MJO (RMM) indices39 (Fig. S5). For the subsets of constructive interference, we found that tropical convection related to an MJO tends to be located over the Maritime Continent, corresponding to phases 4–5, in negative lags generally between −20 and −10 days, and transitions to the boundary between phases 6 and 7 at lag 0, while the magnitude of the MJO signal has become stronger since lag −5. In the subsets of destructive interference, the MJO propagation tends to start from the boundary between phases 1 and 8 at lag −10 and heads toward phase 3 at lag 0, indicating that suppressed tropical convection is often located over the western Pacific prior to destructive interference onset. These contrasting relationships between the MJO and the two forms of wave interference are consistent with the preceding arguments about the role of tropical convection, although the amplitudes of the composited RMM indices are statistically significant mostly at a few days before and after lag 0. This MJO contribution to the North Pacific atmospheric circulation variability is consistent with the previous MJO teleconnection studies40,41 as well as previous global wave interference studies10,23.

On the seasonal time scale, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the dominant mode of tropical Pacific variability, which convectively excites atmospheric teleconnection patterns and impacts the extratropics including the North Pacific Ocean31,42,43,44,45,46. The regression of the December-to-February (DJF) mean observational sea surface temperatures (SSTs) on the NP SWI (Fig. S6) reveals that constructive interference and destructive interference favor the La Niña-like and El Niño-like tropical SST patterns, respectively. This preference of tropical SST mean state is similarly found from the subsets of wave interference days over the analyzed period (Table S2).

Given that an upstream Eurasian wave train is another important precursor of wave interference, we quantify the growth and decay of the Eurasian wave train through an index defined by the mean length of the horizontal wave activity flux over the Eurasian continent47, denoted by a purple line in Fig. 4B. The Eurasian wave train first reaches significant amplitude at lag day −6, peaks at lag day −2, and rapidly diminishes afterwards. Together with the composite maps (Fig. 1), the relative timing of the wave train from Eurasia to North America is estimated to be a 7–10-day period48. To further investigate the relative contributions of the Eurasian wave train and tropical convection to the occurrence of constructive interference separately, we computed the magnitude of the wave activity flux anomalies averaged over the Eurasian domain at the pentad of lag −3 to −7 for each constructive interference event (“Methods”). We defined the strong and weak Eurasian wave train subsets as the top and bottom terciles of the resultant values, respectively, inspired by the recent finding that the dynamical pathways associated with climate extremes can be reasonably separated out by taking the strength of regional Rossby wave trains into account49. Figure 5 depicts a pronounced difference in the magnitude of Eurasian wave train between the two subsets (Fig. 5B, F). However, in the weak Eurasian wave train subset, it simultaneously shows stronger positive streamfunction anomalies over the western subtropical Pacific and poleward propagating wave activity flux. Thus, despite the much weaker Eurasian wave activity flux in this subset, we found a similar spatial structure of constructive interference over the North Pacific at the peak and Rossby wave trains traversing North America at the decay stage.

Pentad composites of 250-hPa streamfunction anomaly (shading; \({{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{2}\) \({{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\)) and wave activity flux (black vector; \({{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{2}\) \({{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-2}\)) averaged over (A, E) lag days −12 to −8, (B, F) −7 to −3, (C, G) −2 to +2, and (D, H) +3 to +7 for the subsets of (A–D) (left) strong Eurasian wave train and (D–F) (right) weak Eurasian wave train events during constructive interference. Stippling indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05) evaluated by Monte Carlo simulations. Purple boxes in the second row indicate the domain used in this study (30°–120°E and 50°–80°N) to estimate the strength of the Eurasian wave train.

Given that pronounced constructive interference occurred even in the absence of a strong Eurasian wave train precursor, it is reasonable to hypothesize that this weak Eurasian wave train subset corresponds to the events that are primarily influenced by the western warm-pool convection (e.g., Fig. 4B). We thus further examined the lag composites of SWI values and the western warm-pool OLR anomalies associated with the strong and weak Eurasian wave train subsets (Fig. S7). The results show that the weak Eurasian wave train subset is preceded by anomalously enhanced warm-pool convection, whereas the strong Eurasian wave train subset shows a near-average or weakly suppressed warm-pool convection. Since there is no prominent difference in the evolution of SWI between the two subsets, we conclude that both wave sources play a similarly important role in the occurrence of North Pacific wave interference. Namely, both the Eurasian wave train precursor and warm pool convection are crucial components of wave interference, but wave interference does not require the occurrence of both precursors for highly amplified wave interference to occur. Due to either individual or the combination of both wave sources, the North Pacific wave interference intensifies, and is followed by strong downstream propagation of wave trains toward the North Atlantic Ocean.

Next, we examine the possible role of upper-tropospheric high-frequency eddy forcing, which also acts to sustain the growth and maintenance of atmospheric teleconnection37,50 patterns. This synoptic time scale eddy forcing is defined as the magnitude of 2.5–6–day band-pass filtered eddy vorticity flux at 250 hPa averaged over the North Pacific domain (“Methods”) and is also normalized for its visualization. Approximately 1 to 6 days prior to the onset of wave interference (i.e., lag days −10 to −5), synoptic-scale eddy forcing is reduced (Fig. 4B), indicating suppressed transient eddy activity over the North Pacific Ocean. In particular, during constructive interference, synoptic-scale eddy forcing tends to be suppressed along the intensified jet stream and enhanced at both flanks of the jet exit region (Fig. S8), which invokes a mechanism of upper tropospheric eddies being trapped by the strong subtropical jet during midwinter51. In case of destructive interference, because the subtropical jet weakens and broadens, the signs of anomalies are opposite to those in constructive interference but with similar magnitudes, hence resulting in a very small domain-averaged value (Fig. S4B). This result indicates the pronounced shifts in the North Pacific synoptic-scale eddy forcing during wave interference events. Furthermore, these shifts are preceded by the anomalous warm-pool convection, which contributes to the evolution of anomalous planetary-scale eddy activity associated with the North Pacific wave interference. The compensating relationship between planetary-scale (quasi-stationary) eddies and synoptic-scale (transient) eddies has been thoroughly investigated by previous studies on atmospheric teleconnections and energy transport8,12,32,52. As the North Pacific interference evolves, the intensity of domain-averaged synoptic-scale eddy forcing is restored to near its climatological value (Fig. 4B).

In the stratosphere, the polar vortex weakens significantly following the peak of constructive interference. Specifically, the lag composites of the 50-hPa zonal wind anomalies at 60°N (pink line of Fig. 4B) reveal that the slowing of the stratospheric polar reaches significant levels 3 days after the peak of constructive interference, a result likely owing to enhanced poleward heat flux and the associated upward wave activity23,30. This polar vortex disruption is more clearly seen in the vertical cross section of the zonal-mean zonal wind anomalies (Fig. S9).

North Pacific stationary waves simulated by the SPEAR model

Climatological stationary waves simulated by state-of-the-art climate models reasonably match with those in reanalysis, albeit with some regional differences9,16,21,53. To examine the spatial structure of climatological stationary waves simulated by the SPEAR model, we compute the modeled zonal-mean removed 250-hPa streamfunction field and compare with that of ERA5 reanalysis (Fig. 6). The key features of the observed stationary waves such as the quadrupole pattern over the North Pacific Ocean and the tripole pattern over the North Atlantic Ocean are reasonably reproduced by the model, as evidenced by the very high spatial correlation (0.975) between SPEAR and ERA5 over the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 6B). We further ascertained that the evolution of the modeled constructive interference in the recent historical period is overall in agreement with the observed evolution, which is supported by spatial correlations between ERA5 and SPEAR composites exceeding 0.89 (Fig. 7A, D, G). The growth and decay of wave interference, as well as the preceding wave train over Eurasia and the downstream wave train toward the North Atlantic, are well captured by SPEAR. This strong correspondence lends confidence in the model representation of wave interference.

The climatological stationary waves, shown in the 250-hPa streamfunction field, during the recent historical winters (1979/1980–2019/2020 DJF) derived from (A) the ERA5 reanalysis, (B) SPEAR 30-ensemble-member mean, (C) CMIP6 19-multi-model mean. For (B) and (C), the root-mean-squared error (RMSE) of the model response against ERA5 is shown at the bottom left of the panel. The climatological stationary waves during the late twenty-first century winters (2059/2060–2099/2100 DJF) (D) derived from SPEAR 30-ensemble-member mean and (E) CMIP6 19-multi-model mean. Differences between the two epochs derived from (F) SPEAR 30-ensemble-member mean and (G) CMIP6 19-multi-model mean. In (F), the differences statistically significant at the 1% level, based on a two-sided t-test, are plotted. In (G), stippling indicates areas that 15 out of 19 models agree on the sign of the change. Its spatial pattern correlation against the SPEAR 30-ensemble-member mean is shown at the bottom right of the panel.

Pentad composites of 250-hPa streamfunction anomalies (\(\psi\); shading) averaged over (A–C) lag days −7 to −3, (D–F) −2 to +2, and (G–I) +3 to +7 for constructive interference events in the (A, D, G) (left) recent historical winters and (B, E, H) (center) late twenty-first century winters, and (C, F, I) (right) differences between the two periods. The corresponding total 250-hPa streamfunction is overlaid by black contours with an interval of \(15\times {10}^{6}\,{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{2}\) \({{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\). Spatial correlation between the ERA5 and the corresponding SPEAR constructive interference composites at each pentad is denoted at the upper right corner of the left panels. Stippling indicates where at least 80% of the ensemble members agree with the sign.

While the overall stationary wave structure is broadly similar in the late twenty-first century (Fig. 6D), the difference between the early and late periods reveals substantial regional changes in the structure of stationary waves (Fig. 6F). In the North Pacific Ocean, specifically, negative differences are found over the Kamchatka Peninsula and Gulf of Alaska, and positive differences are located over the western subtropical North Pacific and far eastern tropical Pacific, which is reminiscent of the extratropical response to the ENSO and suggests a connection to changes in tropical Pacific SSTs31,42,43,44,45,46 and the associated stationary wave forcing54. We explicitly show that this connection between changes in stationary waves and tropical convection is well simulated by SPEAR in a later section. The structural changes of stationary waves indicate that in the projected future climate, the climatological trough and ridge in the western Pacific strengthens while those in the eastern Pacific weaken, which have bearing on the structure of wave interference. To demonstrate these structural changes are not model-dependent, we further examine 19 model simulations from phase 6 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6; see Table S3 for specific model information)55 and their structural changes of stationary waves between the early and late periods (Fig. 6C, E, G). For the recent historical period (Fig. 6C), the CMIP6 multi-model mean stationary waves reasonably reproduce the aforementioned features of the observed stationary waves, similar to the SPEAR model, as measured by their comparable root-mean-squared errors. Moreover, the projected changes of stationary waves simulated by CMIP6 models reveal that climate models generally agree on the structural changes of Northern Hemisphere stationary waves in a warming climate, especially over the Pacific-North American domain that is closely related to the occurrences of North American climate extremes. Previous studies employing CMIP5 models similarly showed the robust model agreement on the projected changes in wintertime stationary waves16,53. Although the inter-model spread in the magnitude of regional stationary wave changes is not negligible21, the variance of the projected stationary wave changes across the CMIP6 models has been reduced by the half of that of the CMIP5 models, indicating a notable improvement in CMIP656. Prompted by a great resemblance of the projected stationary wave changes between SPEAR and CMIP6 (i.e., pattern correlation \(\approx\) 0.92), we argue that the SPEAR model results are likely to reflect the general behavior of climate models for the projected changes associated with the North Pacific wave interference. With this in mind, we address how the structure of wave interference changes in future projection by investigating the evolution of the model upper-level circulation anomalies during wave interference events in the two different epochs (Fig. 7). We focus on constructive interference for brevity, but the findings also apply to destructive interference.

Projected changes in the spatial structure of North Pacific wave interference and its downstream impacts

Constructive interference in the late twenty-first century shows substantial structural changes compared to that in the recent historical period. At the peak of interference, differences between the two epochs are found mostly over the North Pacific Ocean, with positive anomalies centered over the subtropical North Pacific and negative anomalies over the Gulf of Alaska (Fig. 7F). These differences resemble a Rossby wave train excited from localized tropical convection in the western equatorial Pacific region44. In the following pentad, the differences develop farther downstream with positive anomalies over northern North America flanked by negative anomalies to the west and southeast, resulting in a quadrupole pattern that resembles the positive phase of the PNA pattern (Fig. 7I). The difference map indicates an overall eastward shift of the wave train straddling the Pacific North America domain in the late twenty-first century and a weakened ridge over the northwestern North America, which is associated with reduced poleward heat and moisture transport via the Gulf of Alaska. The composites of 2-m temperature anomalies in the later epoch indeed show that the surface temperature response is controlled by the weakened west-east pressure gradient over the central to eastern North Pacific Ocean (Fig. S10). For instance, in high latitudes, constructive interference in the late twenty-first century produces less warming over Alaska and less cooling over the Russian Far East and northeastern Canada, in accordance with regional weakening of the sea level pressure and the associated near-surface temperature advection anomalies. In the pentad following peak interference, the reduction of the cooling over northern North America reaches a peak, and the U.S. West Coast experiences anomalous warming (Fig. S10H, I).

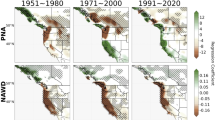

Projected changes in regional atmospheric circulation induce changes in regional climate extremes1,14,57,58. Prompted by the observational result that the North Pacific wave interference leads to large-scale spatial changes in the occurrence of the North American cold and precipitation extremes, we investigate how these regional climate extremes driven by wave interference will change in late twenty-first century. As evidenced by the model fidelity of wave interference (Fig. 7), the SPEAR simulations of the same analyzed period reasonably capture the spatial changes of climate extremes associated with constructive interference, including the decreased probability of cold extremes over northwestern North America and precipitation extremes over the western U.S., as well as increased probability of cold extremes over the continental U.S. and precipitation extremes over Alaska (Figs. 2 and 8). Due to the removal of internal variability in the ensemble-mean composite fields, it is more clearly seen that within a week after constructive interference takes place, the Rossby wave train straddling North America (Fig. 7I) extends the regions of robust changes in cold and precipitation extremes to the central and eastern U.S. (Fig. 8D, J). In the later epoch, however, the probability of cold extremes influenced by the upstream constructive interference is substantially decreased over most of North America except the southeastern U.S. (Fig. 8A–F). The reduced cold extreme occurrence is consistent with changes in the structure of constructive interference wherein the eastern flank of the ridge over northwestern North America is amplified (Fig. 7H), and thus positive streamfunction differences relative to the earlier epoch are dominant over North America (Fig. 7I). On the other hand, the weakened ridge over the Gulf of Alaska (Fig. 7I) and reduced surface warming (Fig. S10I) results in the weak reduction of cold extremes over Alaska and western Canada (Fig. 8F).

Pentad composites of changes in occurrence relative to the climatological frequency of occurrence of (A–F) cold extremes (below the 5th percentile of daily minimum temperature) and (G–L) heavy precipitation extremes (above the 95th percentile of daily precipitation) averaged over (A, B, G, H) lag days −2 to +2, and (C, D, J, K) +3 to +7 during constructive interference events for (A, D, G, J) (left) the recent historical winters, (B, E, H, K) (center) late twenty-first century winters, and (C, F, I, L) (right) differences between the two periods. Stippling indicates where at least 80% of the ensemble members agree with the sign. Boxes denote the same domains as in Fig. 2.

The connection between constructive interference and heavy precipitation extremes also generally weakens in the late twenty-first century, although this does not hold for all locations. In particular, the enhancement of heavy precipitation over Alaska and western Canada is weakened (Fig. 8G–I), which is also quantitatively shown by the epoch difference of the area-averaged changes in precipitation extremes over the three domains (Table S4). Most regions of North America are likely to experience less heavy precipitation extremes in the late twenty-first century winters by constructive interference. Over California, however, we see a notable sign reversal to enhanced heavy precipitation 3–7 days after the interference (Fig. 8J–L), in line with the eastward extension of the subtropical Pacific High (Fig. 7H, I) and the negative changes of the streamfunction anomalies over the northeastern North Pacific Ocean. These circulation anomalies indicate the zonal elongation of the Pacific jet toward the U.S. West Coast18, and consistent with their equivalent barotropic structure21 (e.g., Fig. 3), the negative sea level pressure changes in the Aleutian Low region result in the subsequently enhanced southerly advection near the surface (Fig. S10I). Over northern Mexico, this results in an extended period with an enhanced likelihood of heavy precipitation extremes. Overall, Fig. 8H, K suggests that the southwestern U.S. may experience more extreme swings between suppressed and enhanced heavy precipitation extremes associated with constructive interference. Along with the climate extreme responses, similar regional weakening in convergence of eddy heat flux and moisture flux fields occurs (Fig. 7), supporting that the reduced zonal asymmetry of stationary waves in a warmer climate modulates the frequency of occurrences of North American climate extremes through the weakened poleward eddy heat and moisture transport.

This relationship between the North Pacific wave interference and its North American impacts also operates on longer timescales. The generally reduced southern and eastern continental cooling associated with constructive interference holds for seasonal timescales as it does for intraseasonal timescales (Fig. S11). Moreover, in the late twenty-first century, the regressions of circulation anomalies overall shift northeastward, accompanying the weakened zonal asymmetry over the eastern North Pacific Ocean. As a result, changes in the surface temperature fields for seasonal timescales depict less cooling over eastern Canada, resulting in the positive difference between the two epochs (Fig. S11C, F, I).

Projected changes in the relationship between tropical convection and North Pacific wave interference

The wave interference-related circulation differences between the two epochs, which resemble a poleward propagating Rossby wave train (Fig. 7), suggest that these differences may be rooted in changes in tropical convective forcing. To investigate this possibility, we show in Fig. 9 the spatial pattern of OLR anomalies preceding constructive interference events from the recent historical and late twenty-first century winters. The composites from the early 41-year period show an enhanced zonal asymmetry of tropical convection that entails enhanced convection over the western tropical Pacific and suppressed convection over the date line, consistent with observational results10,23,32 (Fig. 4A). For a closer comparison with the observed evolution of tropical convection (e.g., Fig. 4A), we construct Hovmöller diagrams of the SPEAR tropical OLR anomalies for both SPEAR-simulated constructive and destructive interference events (Fig. S12). For constructive interference, the model results reproduce the key observed features such as negative OLR anomalies over the Maritime Continent (i.e., 90°–150°E) at lag 0, which propagated from the Indian Ocean at lag −20 days, and the persistence of this OLR dipole structure from lag −7 to +3 days (Fig. S12A). During destructive interference, the opposite features seen in observations—suppressed western Pacific convection and enhanced central Pacific convection—are also well reproduced by the SPEAR, although its persistence is somewhat shorter than in the observations. From these model results, we conclude that the relationship between tropical convection and wave interference is also well captured by SPEAR. The spatial maps in the late twenty-first century period (middle column in Fig. 9) show that this zonal asymmetry of tropical OLR anomalies associated with constructive interference, however, weakens by the eastward shift of the western tropical Pacific convection and weaker suppression over the central tropical Pacific (Fig. 9G–I). Consistently, previous idealized modeling studies showed that the eastward displacement of the extratropical response to tropical Pacific convective forcing can be induced by the eastward shift in the forcing40,44,59.

Triad composites of outgoing longwave radiation anomalies (shading) averaged over (A–C) lag days −11 to −9, (D–F) −8 to −6, (G–I) −5 to −3, and (J–L) −2 to 0 for constructive interference events in (Left; A, D, G, J) the recent historical winters and (Center; B, E, H, K) late twenty-first century winters, and (Right; C, F, I, L) differences between the two periods. Stippling indicates where at least 80% of the ensemble members agree with the sign.

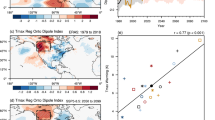

To further support that this weakened zonal asymmetry in tropical convection is indeed a primary driver of the projected stationary wave and associated wave interference changes, we next demonstrate that the projected OLR change pattern is tied to an upper-tropospheric circulation pattern that is consistent with the projected stationary wave changes. Figure 10A shows the differences of DJF-mean tropical OLR between the two epochs, a pattern that is characterized by intensified convection over the central tropical Pacific that accompanies a projected enhancement of equatorial eastern and central Pacific surface warming60. We next construct a tropical OLR index that measures the degree to which the daily, recent historical OLR anomalies resemble the OLR change pattern along the equatorial Pacific (red box in Fig. 10A; see “Methods”). We then evaluate the relationship between this OLR change pattern and upper-tropospheric circulation in the recent historical period by calculating the regressions of recent historical 250-hPa eddy streamfunction anomalies on this tropical OLR index. The resulting regression pattern (Fig. 10B) closely resembles the projected stationary wave pattern (Fig. 6F) in the Pacific/North America region (pattern correlation \(\approx\) 0.71), confirming that the projected changes in the North Pacific stationary waves are consistent with the Rossby wave response to the changes in tropical Pacific convection.

A Differences of the SPEAR ensemble-mean tropical outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) between the recent historical and late twenty-first century winters. Red box denotes the domain for the tropical OLR index (15°S–15°N, 100°E–100°W; see “Methods”). B Regressions of daily DJF 250-hPa eddy streamfunction anomalies onto the tropical OLR index averaged over lags of 0–10 days (OLR index leading). The pattern correlation of 0.71 in the upper right corner denotes that between the regression field and the differences of 250-hPa climatological stationary waves (Fig. 6F) for the North Pacific-North America domain (green box; 0°–75°N, 120°E–60°W). The seasonally averaged and detrended sea surface temperature regressed onto the seasonally averaged and detrended NP SWI for the (C) recent historical winters and (D) late twenty-first century winters. Stippling in (B–D) indicates where at least 80% of the ensemble members agree with the sign.

To investigate this linkage from a different angle, the DJF-mean SST regressed against DJF-mean NP SWI for the recent historical and late twenty-first century periods are shown in Fig. 10C, D, respectively. In the recent historical winters, constructive interference is associated with an increase of the western tropical SST and a decrease of the eastern tropical SST, resembling the SST pattern during La Niña, which is consistently found in the observation61 (Fig. S6). Furthermore, cooling over the western North Pacific and warming over the eastern North Pacific are reminiscent of the positive phase of Pacific Decadal Oscillation in the North Pacific Ocean62. In the late twenty-first century, the spatial pattern of extratropical SST regression is maintained in general, but that of tropical SST shows stark differences in that positive regressions are displaced toward the central tropical Pacific and intensified along the equatorial Pacific. The changed tropical SST regressions indicate that, unlike in the present climate, interannual variability of wave interference is tied to a weaker zonal asymmetry in tropical forcing.

Meanwhile, although not explored in this study, it is possible that orography and land-sea contrast also may significantly contribute to future changes in stationary waves and stationary-transient wave interference. For instance, previous idealized modeling studies showed that the stationary wave response to orography forcing over the North Pacific Ocean could be characterized by the upper-tropospheric trough over the Okhotsk Sea and ridge over the western subtropical Pacific3,6. In a warming climate, the strengthening of the climatological trough and ridge in the western Pacific is simulated by SPEAR (Fig. 6F). However, these changes in the western Pacific may not be sufficiently induced by tropical forcing alone. We suspect that orographically induced stationary waves may also strengthen over the western Pacific due to stronger midlatitude upper tropospheric westerlies21 and their interaction with orography in the projected future. On the other hand, the stationary wave response to land-sea contrast is expected to be reduced due to a faster warming of land than that of ocean. A recent study imposed a reduced land-sea contrast to their idealized model by warming the surface and found a weakening of stationary waves over western North America63, which is consistent with the projected change of stationary waves. Thus, we conclude that orography and land-sea contrast would also contribute to changes in different regions of the North Pacific stationary waves, while their evaluation in climate models remains for further investigation.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that stationary-transient wave interference is a useful concept to estimate the intensity of zonally asymmetric circulation, which impacts downstream climate extremes through regulating the regional transport of heat and moisture. We emphasize that during constructive interference, the probability of cold extremes across the CONUS is substantially increased, while that of heavy precipitation extremes over the U.S. West Coast is suppressed; these effects on extremes are reversed during destructive interference. This driving of North American climate extremes by the North Pacific wave interference exceeds that of the well-known and more commonly studied teleconnection patterns such as the PNA or NAO. By leveraging large ensembles of simulations from the GFDL SPEAR coupled climate model, we further show that the projected changes in the spatial structure of wave interference, corresponding to those in the climatological stationary waves, lead to reduced poleward heat and moisture transport, and thus generally a weaker relationship with North American climate extremes. These changes can be attributed to the eastward shift of tropical convection along the central equatorial Pacific (i.e., reduced zonal asymmetry of tropical convection).

The projected changes in the relationship between the North Pacific wave interference and tropical convection are similar to the projected changes in the ENSO teleconnection and are characterized by an intensification and eastward displacement of the anomalous trough over the Aleutian low and ridge over the eastern subtropical North Pacific for the North Pacific domain31,43,44,45,46, which is reminiscent of the circulation response to the central Pacific El Niño64. Both responses are related to the pattern of mean tropical SST changes43,60, the associated projected weakening of the Pacific Walker circulation65,66, and their impacts on the Rossby wave source through the reduced upper tropospheric divergence17. Similar to other climate model simulations, the SPEAR simulations show larger projected warming in the central equatorial Pacific relative to other tropical oceans45,46. Such a change in the SST variability pattern67 would consistently result in an eastward shift of the convectively active regions (Fig. 9), and in a weakening of the eastern North Pacific stationary waves. As shown earlier, this weakened eastern North Pacific ridge in turn attenuates transport of heat and moisture poleward, subsequently altering the frequency of occurrence of North American climate extremes, which is an overall reduced impact of interference events. Over the continental U.S., therefore, less cold extremes are likely to be driven by constructive interference, while the western U.S. is likely to have more heavy precipitation extremes, consistent with its wetter hydroclimate in future projections18,21,56,68,69.

Our finding that the projected changes in stationary waves and wave interference are contingent upon the tropical SST trend pattern stresses the importance of model representation in this pattern of SST evolution. The observed strengthening trend of the western warm-pool tropical convection and the corresponding La Niña-like SST trend pattern over the past several decades52,70,71 hitherto deviates from projections in most state-of-the-art coupled climate models, and there are diverse but incomplete and limited theories to understand such discrepancy in SST trends between models and observation66. As demonstrated in this study, projected changes in the intraseasonal variability of North American cold and heavy precipitation extremes are sensitive to the SST warming pattern. Thus, resolving the ongoing issue of the projected tropical Pacific SST pattern is crucial for the simulation of North American climate extremes on the intraseasonal time scale and likely on longer timescales as well.

The changes in the occurrence of the intraseasonal precipitation extremes associated with wave interference will likely have significant effects on regional hydroclimate. In certain regions such as California, changes in the frequency of occurrence of winter storms with extreme moisture transport can terminate a severe, multi-year drought72. For instance, in the winter of 2016/17, a multi-year drought in California rapidly transitioned to widespread flooding through winter storms accompanying heavy rainfall73, which was affected by the deamplification of the North Pacific stationary waves74 (2016/17 DJF-mean NP SWI = −0.34, Fig. S3F). We recall that weak NP SWI boreal winters tend to entail strengthening of the eastern North Pacific subtropical high and weakening of the climatological ridge over Alaska and western Canada (Fig. S11). Hence, even a small increase or decrease in the number of heavy precipitation extremes, driven by the projected changes in wave interference, might be critical for terminating or maintaining drought relative to the present.

The resemblance of the North Pacific interference between reanalysis and the SPEAR model simulations demonstrates model fidelity to capture an intraseasonal variation of the zonally asymmetric extratropical circulation. However, considering that structural model uncertainty in the climatological stationary waves is not negligible16,21,56, one can still improve the representation of stationary waves, and consequently stationary-transient wave interference, by reducing model biases such as orographic drag9 or latent heating biases53. Adopting a finer vertical resolution with a well-resolved stratosphere may also reduce biases in both the stratospheric and tropospheric stationary waves75. In the same spirit, a higher horizontal resolution that includes more realistic orography effect and the small-scale oceanic processes may enhance the model stationary waves6.

As an upstream wave train provides a potential predictability pathway for temperature and precipitation extreme events over North America48,49,76,77, a deeper understanding of the North Pacific wave interference variability can be useful for improving the subseasonal-to-seasonal forecasts of the North American climate extremes. Future work will focus on analyzing retrospective forecasts for the North Pacific wave interference variability and its downstream impact during boreal winter.

Methods

Observational data

In this study, the fifth generation of the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Reanalysis78 (ERA5) is used for the observational analysis. The analyzed period spans from 1979/1980 to 2019/2020 and from December to February (DJF). The daily-mean data of zonal wind, meridional wind, 2 m temperature, vertically integrated moisture flux, and mean sea level pressure (MSLP) are obtained by averaging four six-hourly fields with a 1.25° × 1.25° horizontal resolution. For outgoing longwave radiation (OLR), used as a proxy for deep atmospheric convection, the daily accumulated data is obtained from 24-hourly fields. A negative OLR anomaly in the tropics, or low OLR, indicates anomalously active tropical convection. In addition, the global daily minimum/maximum temperature \(({T}_{\min }/{T}_{\max })\) and precipitation data from the NOAA Climate Prediction Center79(CPC), which has a 0.5° × 0.5° horizontal resolution, are used to examine the relationship between surface climate extremes and upstream upper-level wave interference. Throughout this study, daily anomalies for the variables are obtained by removing the seasonal cycle that retains the first 10 harmonics of the calendar-day-mean values. For SST, the ERSSTv5 data80 is used, and monthly anomalies are obtained by removing the climatological mean.

Model data

We analyze coupled global climate model simulation data from the Seamless System for Prediction and Earth System Research (SPEAR) model developed by the GFDL. The SPEAR model incorporates the recently developed component models including the AM4 atmosphere model, LM4 land model, SIS2 sea ice model, and MOM6 ocean model, along with parameterizations and configurations optimized for simulating the seasonal-to-decadal variability of the climate system. Further details can be found in ref. 81 We analyze 30-member ensembles of the SPEAR version that has a 50-km atmospheric horizontal resolution (SPEAR-MED) and a 1.0° × 1.0° oceanic horizontal resolution with tropical refinement to 0.3°.

For comparison with the ERA5 reanalysis and computational efficiency, atmospheric variables are regridded to a 1.25° × 1.25° horizontal resolution using bilinear interpolation. To investigate how the structure of stationary waves changes in a warming climate, we define two different epochs—the recent historical winters (1979/1980–2019/2020) and the late twenty-first century winters (2059/2060–2099/2100)—by using the historical simulations forced by the observed radiative forcing and the projections following a Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5-8.5 (SSP5-8.5). The results are not qualitatively sensitive to the choice of this time window (e.g., 31-year instead of 41-year window). In this study, the historical simulations cover the period of 1979–2014 and the SSP5-8.5 simulations cover the period of 2015 to 2100. Thus, for the recent historical winters, we combine the entire period of the historical simulations and the first 6 winters of the SSP5-8.5 simulations. Each ensemble member is initialized by a different initial condition derived from a long-term control run with a 20-year interval. Daily anomalies of the variables and monthly anomalies of SST are derived from individual ensemble members in the same manner as in the observational analysis. In the same manner, 19 model simulations from phase 6 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6; Table S3)55 have been used for examining the projected changes in stationary waves.

North Pacific stationary wave index

The daily variability of wave interference over the North Pacific domain is measured using the following procedure, as in previous studies10,23. We first derive a daily 250-hPa streamfunction anomaly (\({\psi }^{{\prime} }\)) by removing its seasonal cycle that retains the first 10 harmonics of the calendar-day-mean values (\(\widetilde{\psi }\)). Next, a projection time series is constructed by the following equation:

A daily projection value at day \(t\), or \({{{{\rm{P}}}}}_{{{{\rm{SW}}}}}\left(t\right)\), is obtained by projecting the daily \({\psi }^{{\prime} }\) onto the zonal-mean removed seasonal cycle (\(\widetilde{{\psi }^{*}}\)) for the corresponding day of the year, \(d\). \({\lambda }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\) and \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{j}}}}}\) represent longitudinal and latitudinal grid points at the subscripts \(i\) and \(j\), respectively. To capture the variability over the North Pacific sector only, the projection domain is confined to 15°–75°N and 140°E–120°W. The results are not qualitatively sensitive to the choice of the domain as long as it includes the North Pacific Ocean. The projection time series is normalized by its DJF standard deviation and mean, and then referred to as the North Pacific stationary wave index (NP SWI). For identification of constructive interference events, days with an NP SWI value greater than 1.0 are first selected. Next, the temporal peaks from the selected days are isolated from each other by at least 10 days. The threshold of the NP SWI value smaller than −1.0 is applied for identifying destructive interference events. In the same manner, we identified the positive and negative phase events of the PNA and NAO (Fig. S3). To examine the relative contributions of planetary- and synoptic-scale circulation anomalies to wave interference, we partition the daily horizontal wind fields to planetary-scale (i.e., zonal wavenumbers 1 to 3) and synoptic-scale (i.e., zonal wavenumbers equal to or larger than 4) components through a Fourier transform decomposition. The resultant planetary-scale and synoptic-scale wind fields are then used to compute the corresponding scale of the streamfunction.

To investigate the potential influence of long-term trends on the lag composites of wave interference events, we conducted the same analysis after removing interannual variability from the diagnosed variables (i.e., subtracting each winter-mean value from daily anomalies). The presented results on the intraseasonal time scale are not sensitive to the retention of interannual and longer-term variability.

In the SPEAR model simulations, the NP SWIs for the recent historical and late twenty-first century periods are computed from each ensemble member by the same method as in observational analysis, except that daily anomalies and the zonal-mean removed seasonal cycle are used from the corresponding period. Furthermore, for normalization of the late twenty-first century period, the standard deviation and mean value from the recent historical period are used to apply the same threshold of defining constructive and destructive interference events.

Wave activity flux diagnostics and binning analysis

To analyze wave activity propagation during wave interference events, the anomalous horizontal wave activity flux has been computed by the following the equation given by ref. 82:

\({{{\bf{W}}}}\) is the wave activity flux, \(p\) is (pressure/1000 hPa), \({{{\bf{U}}}}\) is the magnitude of the DJF climatological basic flow with zonal speed \(U\) and meridional speed \(V\), \(a\) is the Earth’s radius, \({\psi }^{{\prime} }\) is the daily streamfunction anomaly, and (\(\lambda\), \(\phi\)) are the latitude and longitude, respectively. In the composite analysis, the daily-mean \({{{\bf{W}}}}\) is computed by using the lag composited \({\psi }^{{\prime} }\) anomalies and averaging 6-hourly fluxes.

For the binning analysis based on the magnitude of a Eurasian wave train (e.g., Fig. 5), we computed the daily time series of the magnitude of the daily-mean \({{{\bf{W}}}}\) anomalies, which is defined as follows49:

where subscript \(x\) and \(y\) indicate the zonal and meridional components of \({{{\bf{W}}}}\) at each grid point, respectively, and \({{{{\bf{W}}}}}_{{{{\bf{{clim}}}}}}\) indicates its DJF climatological value. Analogous to ref. 49, we computed the area-averaged magnitude of the wave activity flux anomaly for the domain of 30°–120°E and 50°–80°N, based on the composites in Fig. 1, to capture the wave train originated from the Eurasian continent. We selected time-averaged fields for lags −7 to −3 days to define a Eurasian wave train precursor. Note that the results are not qualitatively sensitive to the choice of the domain (e.g., 30°–90°E or 30°–80°N) or time window (e.g., lag days −7 to −1). Lastly, we ranked the magnitude of \(\left|{{{{\bf{W}}}}}_{{{{\bf{{anom}}}}}}\right|\) during wave interference events, and then extracted the top (strong Eurasian wave train events) and bottom (weak Eurasian wave train events) terciles.

Definition of climate extremes

Climate extremes are identified by selecting days when the daily anomaly of the variable exceeds a specified threshold of its climatological distribution from the 1979/1980–2019/2020 DJF period (3701 days). The occurrence of climate extremes is counted at each grid point. For cold extremes, the daily \({T}_{\min }\) anomaly and the 5th percentile threshold are used. For heavy precipitation extremes, the daily precipitation and the 95th percentile threshold are used, except that all days with less than 0.01 mm of precipitation are excluded prior to the calculation.

In the SPEAR model simulations, climate extremes are identified from each ensemble member by the same method as in the observational analysis. Percentile thresholds are separately computed for the recent historical and late twenty-first century periods to consider the impact of global warming in the latter period.

Intensity of transient eddy forcing

The anomalous transient eddy forcing has been computed as the 2.5–6-day band-pass filtered eddy vorticity flux convergence (EVFC) at 250 hPa, which is written as follows50:

where \(\nabla\) denotes the horizontal divergence operator, U denotes the horizontal wind vector, \({{{\rm{\zeta }}}}\) denotes the relative vorticity, the prime denotes the seasonal cycle removed daily anomaly, and the subscript “HF” denotes the Butterworth band-pass filtered fields. To examine how the intensity of transient eddy feedback varies during the evolution of wave interference, we consider the absolute value of daily EVFC anomalies averaged over the North Pacific domain (same as the NP SWI domain) with area weighting (Fig. 4B).

Tropical OLR index

To determine the degree to which projected stationary wave changes can be predicted from changes in climatological tropical convection, we first construct an index that measures the degree to which daily recent historical OLR anomalies resemble the pattern of climatological OLR changes. For each ensemble member, we project the daily OLR anomalies from the recent historical period onto the ensemble-mean OLR differences between the recent historical and late twenty-first century periods within the equatorial Pacific domain (red box in Fig. 10A; 15°S–15°N, 100°E–100°W) as follows:

where \({P}_{{{{{\rm{OLR}}}}}}\) is a projection time series, the overbar denotes the seasonal average from the ensemble mean, the delta denotes the late twenty-first century minus recent historical periods, and the prime denotes a seasonal-cycle removed daily anomaly. \(t\) represents each day of the recent historical period, while \({\lambda }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\) and \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{j}}}}}\) represent longitudinal and latitudinal grid points at the subscripts \(i\) and \(j\), respectively.

Statistical significance test

Two-sided Monte Carlo permutation tests with 1000 random subsamples are performed to obtain the statistical significance in the composite analysis83. For instance, if the number of events is N, we randomly select N events from all DJF days and make composites. By repeating this procedure 1000 times, a null distribution can be derived at each lag day, and a p value of the observed composites is evaluated therefrom. For testing the statistical significance of a regression coefficient, a two-sided t-test is performed.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available. ERA5 reanalysis data can be accessed from the Copernicus Climate Change Service: Data on pressure levels (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=overview) and single levels (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview). ERSSTv5 SST data can be downloaded from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html. NOAA-CPC global daily maximum/minimum temperature and precipitation data can be downloaded from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/index.html. Also, SPEAR Large ensemble data can be downloaded from https://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/spear_large_ensembles/. The PNA and NAO index time series are available from https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/precip/CWlink/daily_ao_index/teleconnections.shtml, while the RMM indices are available from http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/mjo/. Weather regime dataset is available from https://zenodo.org/records/8165165. The CMIP6 model output can be downloaded from the following portal (https://esgf-data.dkrz.de/projects/cmip6-dkrz/).

Code availability

Codes to compute wave activity flux are available from https://www.atmos.rcast.u-tokyo.ac.jp/nishii/programs/index.html. Other custom codes are direct implementations of statistical methods and techniques that are described in the “Methods” section.

References

Horton, D. E. et al. Contribution of changes in atmospheric circulation patterns to extreme temperature trends. Nature 522, 465–469 (2015).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 1513–1766 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Held, I. M., Ting, M. & Wang, H. Northern winter stationary waves: theory and modeling. J. Clim. 15, 2125–2144 (2002).

Brayshaw, D. J., Hoskins, B. & Blackburn, M. The basic ingredients of the North Atlantic storm track. Part I: land–sea contrast and orography. J. Atmos. Sci. 66, 2539–2558 (2009).

Chang, E. K. M. Diabatic and orographic forcing of northern winter stationary waves and storm tracks. J. Clim. 22, 670–688 (2009).

Garfinkel, C. I., White, I., Gerber, E. P., Jucker, M. & Erez, M. The building blocks of northern hemisphere wintertime stationary waves. J. Clim. 33, 5611–5633 (2020).

Peixoto, J. P. & Oort, A. H. Physics of Climate 520 (American Institute of Physics, 1992).

Shaw, T. A., Barpanda, P. & Donohoe, A. A moist static energy framework for zonal-mean storm-track intensity. J. Atmos. Sci. 75, 1979–1994 (2018).

van Niekerk, A., Scinocca, J. F. & Shepherd, T. G. The modulation of stationary waves, and their response to climate change, by parameterized orographic drag. J. Atmos. Sci. 74, 2557–2574 (2017).

Park, M. & Lee, S. Relationship between tropical and extratropical diabatic heating and their impact on stationary-transient wave interference. J. Atmos. Sci. 76, 2617–2633 (2019).

Cox, T., Donohoe, A., Roe, G. H., Armour, K. C. & Frierson, D. M. W. Near invariance of poleward atmospheric heat transport in response to midlatitude orography. J. Clim. 35, 4099–4113 (2022).

Kaspi, Y. & Schneider, T. The role of stationary eddies in shaping midlatitude storm tracks. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 2596–2613 (2013).

Shaw, T. A. et al. Storm track processes and the opposing influences of climate change. Nat. Geosci. 9, 656–664 (2016).

Shepherd, T. G. Atmospheric circulation as a source of uncertainty in climate change projections. Nat. Geosci. 7, 703–708 (2014).

Hoskins, B. & Woollings, T. Persistent extratropical regimes and climate extremes. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 1, 115–124 (2015).

Wills, R. C. J., White, R. H. & Levine, X. J. Northern Hemisphere stationary waves in a changing climate. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 5, 372–389 (2019).

Haarsma, R. J. & Selten, F. Anthropogenic changes in the Walker circulation and their impact on the extra-tropical planetary wave structure in the Northern Hemisphere. Clim. Dyn. 39, 1781–1799 (2012).

Neelin, J. D., Langenbrunner, B., Meyerson, J. E., Hall, A. & Berg, N. California winter precipitation change under global warming in the coupled model intercomparison project phase 5 ensemble. J. Clim. 26, 6238–6256 (2013).

Tuel, A. & Eltahir, E. A. B. Why is the mediterranean a climate change hot spot? J. Clim. 33, 5829–5843 (2020).

Narinesingh, V., Booth, J. F. & Ming, Y. Blocking and general circulation in GFDL comprehensive climate models. J. Clim. 35, 3687–3703 (2022).

Simpson, I. R., Seager, R., Ting, M. & Shaw, T. A. Causes of change in Northern Hemisphere winter meridional winds and regional hydroclimate. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 65–70 (2016).

Garfinkel, C. I. et al. The role of zonally averaged climate change in contributing to intermodel spread in CMIP5 predicted local precipitation changes. J. Clim. 33, 1141–1154 (2020).

Goss, M., Feldstein, S. B. & Lee, S. Stationary wave interference and its relation to tropical convection and Arctic warming. J. Clim. 29, 1369–1389 (2016).

Huang, J. et al. The connection between extreme stratospheric polar vortex events and tropospheric blockings. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 143, 1148–1164 (2017).

Garfinkel, C. I., Hartmann, D. L. & Sassi, F. Tropospheric precursors of anomalous Northern Hemisphere stratospheric polar vortices. J. Clim. 23, 3282–3299 (2010).

Wang, H. & Ting, M. Seasonal cycle of the climatological stationary waves in the NCEP–NCAR reanalysis. J. Atmos. Sci. 56, 3892–3919 (1999).

Baggett, C. & Lee, S. Ekman pumping and the energetics of the Southern Hemisphere eddy life cycle. J. Atmos. Sci. 71, 2944–2961 (2014).

Smith, K. L., Fletcher, C. G. & Kushner, P. J. The role of linear interference in the annular mode response to extratropical surface forcing. J. Clim. 23, 6036–6050 (2010).

Kolstad, E. W. & Charlton-Perez, A. J. Observed and simulated precursors of stratospheric polar vortex anomalies in the Northern Hemisphere. Clim. Dyn. 37, 1443–1456 (2010).

Garfinkel, C. I., Feldstein, S. B., Waugh, D. W., Yoo, C. & Lee, S. Observed connection between stratospheric sudden warmings and the Madden-Julian oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39 https://doi.org/10.1029/2012gl053144 (2012).

Domeisen, D. I. V., Garfinkel, C. I. & Butler, A. H. The teleconnection of El Niño Southern Oscillation to the stratosphere. Rev. Geophys. 57, 5–47 (2019).

Baggett, C. & Lee, S. An identification of the mechanisms that lead to Arctic warming during planetary-scale and synoptic-scale wave life cycles. J. Atmos. Sci. 74, 1859–1877 (2017).

Baggett, C., Barnes, E. A., Maloney, E. D. & Mundhenk, B. D. Advancing atmospheric river forecasts into subseasonal-to-seasonal time scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 7528–7536 (2017).

Cellitti, M. P., Walsh, J. E., Rauber, R. M. & Portis, D. H. Extreme cold air outbreaks over the United States, the polar vortex, and the large‐scale circulation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 111 https://doi.org/10.1029/2005jd006273 (2006).

Lee, S. H., Tippett, M. K. & Polvani, L. M. A new year-round weather regime classification for North America. J. Clim. 36, 7091–7108 (2023).

Hoskins, B. & Karoly, D. The steady linear response of a spherical atmosphere to thermal and orographic forcing. J. Atmos. Sci. 38, 1179–1196 (1981).

Feldstein, S. B. & Franzke, C. L. E. in Nonlinear and Stochastic Climate Dynamics (eds Franzke, C. L. E. & O’Kane, T. J.) 54–104 (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Madden, R. A. & Julian, P. R. Detection of a 40–50 day oscillation in the zonal wind in the tropical Pacific. J. Atmos. Sci. 28, 702–708 (1971).

Wheeler, M. C. & Hendon, H. H. An all-season real-time multivariate MJO index: development of an index for monitoring and prediction. Mon. Weather Rev. 132, 1917–1932 (2004).

Tseng, K.-C., Maloney, E. & Barnes, E. The consistency of MJO teleconnection patterns: an explanation using linear Rossby wave theory. J. Clim. 32, 531–548 (2019).

Yoo, C., Lee, S. & Feldstein, S. B. Arctic response to an MJO-like tropical heating in an idealized GCM. J. Atmos. Sci. 69, 2379–2393 (2012).

Held, I. M., Lyons, S. W. & Nigam, S. Transients and the extratropical response to El Niño. J. Atmos. Sci. 46, 163–174 (1989).

Zhou, Z.-Q., Xie, S.-P., Zheng, X.-T., Liu, Q. & Wang, H. Global warming–induced changes in El Niño teleconnections over the North Pacific and North America. J. Clim. 27, 9050–9064 (2014).