Abstract

Atropisomeric biaryls bearing carbonyl groups have attracted increasing attention due to their prevalence in diverse bioactive molecules and crucial role as efficient organo-catalysts or ligands in asymmetric transformations. However, their preparation often involves tedious multiple steps, and the direct synthesis via asymmetric carbonylation has scarcely been investigated. Herein, we report an efficient palladium-catalyzed enantioconvergent aminocarbonylation of racemic heterobiaryl triflates with amines via dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation (DyKAT). This protocol features a broad substrate scope and excellent compatibility for rapid construction of axially chiral amides in good to high yields with excellent enantioselectivities. Detailed mechanistic investigations discover that the base can impede the intramolecular hydrogen bond-assisted axis rotation of the products, thus allowing for the success to achieve high enantioselectivity. Moreover, the achieved axially chiral heterobiaryl amides can be directly utilized as N,N,N-pincer ligands in copper-catalyzed enantioselective formation of C(sp3)-N and C(sp3)-P bonds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Axially chiral structures frequently occur in natural products1,2, bioactive molecules3, medicinal chemistry4 as well as material science5,6. Particularly, due to their outstanding performance in asymmetric catalysis as chiral ligands or organo-catalysts7,8,9,10,11, they have been recognized as a class of privileged skeletons for the current development of new catalysts. Among them, atropisomeric biaryls containing carbonyl groups, such as carboxylic acid, aldehyde, ketone, and amide, not only exist in various drug candidates12,13,14,15 (Fig. 1a), but also serve as highly efficient organo-catalysts or ligands in diverse asymmetric transformations, which have been demonstrated by the groups of Maruoka16,17, Guo18,19,20, Zhao21,22,23,24, Matsunaga25,26, Shi27,28, and others29 (Fig. 1b). Nevertheless, the preparation for most of the aforementioned structural motifs invariably involves tedious multi-step synthesis. Although in the past few decades, there has been booming development in the field of asymmetric construction of axially chiral compounds in a catalytic manner30,31,32,33, the atroposelective synthesis of chiral biaryls bearing carbonyl groups via direct asymmetric carbonylation reaction has scarcely been reported.

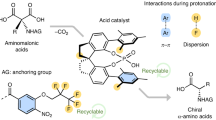

a Selected examples of axially chiral carbonyl-containing structures in natural products and pharmaceuticals. b Selected examples of axially chiral carbonyl-containing structures in catalysts and/or ligands. c Our strategy: Pd-catalyzed asymmetric aminocarbonylation via DyKAT (dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation), proposed reaction mechanistic analysis and possible racemization process of products. d This work: enantioconvergent construction of axially chiral heterobiaryl amides enabled by Pd-catalyzed aminocarbonylation.

Carbonylation reaction continues to be the most efficient and atom-economical strategy to produce carbonyl-containing compounds by merging olefins or aryl (pseudo)halides with CO and different nucleophiles34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. Since the first discovery in 1930s, carbonylation has become a powerful tool for efficient production of various value-added bulk and fine chemicals, and has attracted substantial attentions from both academia and industry48,49,50,51. Notwithstanding these achievements, in contrast, the asymmetric versions are still underdeveloped, which is generally caused by difficult simultaneous control of multiple selectivities (chemo-, regio- and stereoselectivities) along with harsh reaction conditions (elevated temperature and high pressure of CO gas). Despite the daunting challenges, some significant asymmetric carbonylation reactions have been realized by using a combination of chiral ligands with Rh52,53,54,55,56,57, Pd58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66, Ni67,68, or Cu69,70 as catalysts, albeit the substrate scope was limited to norbornene, vinylarenes, cyclopropenes or functionalized alkenes. Besides, intramolecular enantioselective carbonylative cyclization and Heck-type carbonylation71,72,73,74,75,76 also proved to be feasible strategies to give synthetically useful products. Notably, present studies mainly afford carbonyl compounds with central chirality. Recently, two elegant reports from the groups of Gu77 and Liao78 respectively described the site-selective ring-opening aminocarbonylation of five-membered-bridged diarylsulfonium salts and diaryliodonium salts, providing atropisomeric carbonyl scaffolds. Of which, the site-selectivity of C–X bond cleavage for unsymmetric substrates was controlled by steric hindrance. In this context, further development of novel strategies in carbonylation to expand the space of atropisomeric biaryl amides is still highly desirable. The following features of carbonylation were considered: a) the reversible insertion of CO into a C-Pd bond to form an acyl metal species, and b) the conversion of acyl metal intermediates is generally regarded as the rate-determining step. Both features are consistent with the principles of dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation (DyKAT) reactions. We aimed to develop asymmetric carbonylation reactions of racemic heterobiaryls using DyKAT to construct atropisomeric carbonyl compounds, which has never been explored before (Fig. 1c).

Axially chiral heterobiaryls constitute commonly used core skeletons for rapid construction of chiral ligands and catalysts. Therefore, investigations for their enantioenriched preparation from readily available materials have attracted substantial attention in the past decade10,79,80,81,82. In this respect, by employing different nucleophiles or electrophiles as another pertinent coupling partner, transition metal-catalyzed atroposelective cross-couplings of racemic heterobiaryl (pseudo)halides83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92 and C–H activation of heterobiaryls93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103 represent two advanced methodologies among various established strategies. Most reactions proceeded through DyKAT or dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) via configurationally unstable cyclometalated complexes as key intermediates (A or A’, Fig. 1c), followed by interaction with coupling reagents, which was generally regarded as the enantio-determining step. Encouraged by these prominent achievements, we wondered whether the carbonylative cross-coupling of racemic heterobiaryl (pseudo)halides could undergo a similar DyKAT process, providing a straightforward method to access atropisomeric carbonyl compounds. The main challenge for such protocol is the involvement of a more complex pathway compared with previously reported two-component reactions83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92. More specifically, three components not only engender more complicated chemoselectivity, but also may generate five- and six-membered cyclometalated intermediates, which would increase the difficulty in controlling the epimerization between diastereomeric palladacycle species (A and A’, B and B’, Fig. 1c) that could dictate the enantioselectivity of the reaction. Another foreseeable challenge is the stability of the achieved products, which may racemize via the reported quasi zwitterionic transition state104(Fig. 1c, i) or intramolecular hydrogen bond-assisted rotation of axis105 (Fig. 1c, ii). With these challenges in mind, herein, we present an enantioconvergent Pd-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of racemic heterobiaryl triflates via DyKAT to afford a range of axially chiral heterobiaryl amides (Fig. 1d). Mechanistic studies disclosed the role of the base in inhibiting the racemization of products by disrupting the intramolecular hydrogen bond. Furthermore, the utility of these products was demonstrated by applying some of them as chiral ligands in copper-catalyzed asymmetric construction of C(sp3)-heteroatom bonds.

Results

We commenced our investigation into the development of a Pd-catalyzed atropisomeric aminocarbonylation (see Supplementary Tables 1–9 for more details) using racemic 1-(isoquinolin-1-yl)naphthalen-2-yl trifluoromethanesulfonate (1a) and p-methylaniline (2a). First, conditions that are typical for transition metal-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of aryl halides were applied: 5 mol% Pd catalyst, 10 mol% chiral ligand, 3.0 equivalent base, 10 bar CO, toluene, 80 oC. Initially, Pd(OAc)2 was used as a pre-catalyst in the presence of commercially available chiral bisphosphine ligands L1–L8 (Table 1). Most of the ligands afforded the desired product 4 in 10–80% yield with 3–68% enantiomer excess (ee), demonstrating the feasibility of our hypothesis. Among them, the P-chirality phosphine ligand L1 gave the best results both in yield and ee. Notably, axially P, N-ligand L8, was used in a previously reported C–N cross-coupling reaction85, but when it was used in this optimization study, carbonylation product 4 was only observed in 10% yield with −40% ee. Interestingly, the utilization of base plays a crucial role in reactivity, because only less than 5% product could be afforded using other bases such as K2CO3 or triethylamine (NEt3). Furthermore, it was found through the screening of solvents, that the enantioselectivity of the reaction could be promoted to 83% or 89% when using dichloroethane (DCE) or dichloromethane (DCM), respectively, albeit the yield was eroded. Increasing the loading of Pd salt to 10 mol% and using a combination of two solvents (DCE/DCM), resulted in an improvement in the yield of 4 to 91% (87% isolated yield) with 94% ee, which was regarded as the optimal conditions.

Substrate scope

With the optimized conditions in hands, we started to explore the general compatibility of this asymmetric aminocarbonylation methodology via DyKAT. First, the scope of arylamines was investigated under the standard conditions. As shown in Fig. 2, an array of arylamines bearing neutral, electron-deficient, and electron-rich substituents on the phenyl ring, underwent efficient Pd-catalyzed DyKAT aminocarbonylation with racemic 1a to afford the desired axially chiral amides (4–28) in 39–95% isolated yield with 83–95% ee. Interestingly, the electron-deficient amines gave the corresponding products (11–12 and 14–17) with slightly lower ee compared to neutral and electron-deficient amines (4–8). The amines bearing substituents in the o- or m- position of the phenyl terminus gave the corresponding products (18–25) in 39–84% yield with 85–94% ee. Functional groups such as Bpin (13), CN (14), ester (15), aldehyde (16), ketone (17) and halides (10, 20, 22), were well tolerated in the reaction. Finally, the amines containing N-heterocycles, such as pyridine and quinoline, were also suitable substrates in this catalytic system, and gave the corresponding products in 62–79% yield with 88–90% ee.

All reactions were performed in DCM/DCE (0.5 mL/0.05 mL), at 80 °C for 18 h in the presence of racemic heterobiaryl triflate (0.1 mmol), arylamine (0.2 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (0.01 mmol), Cs2CO3 (0.3 mmol), (S, S)-L1 (0.012 mmol) and CO (10 bar). The yields were isolated yields for all products by column chromatography, and the ee was determined by HPLC using a chiral column. aReaction conditions: 5.0 mol% Pd(acac)2, 10.0 mol% (S, S)-L1, Cs2CO3 (0.3 mmol), CO (10 bar), DCM/DCE (0.4 mL/0.1 mL), 70 °C, 18 h.

Subsequently, a range of various heterobiaryl triflates was applied to the Pd-catalyzed aminocarbonylation by using p-methylaniline (2a) as the coupling partner. As demonstrated in Fig. 2, substitution on the 6th or 7th position of the isoquinoline ring did not affect the reaction, and provided both corresponding products both in 83% yield and 92% ee (29 and 30). Besides, the reaction also proceeded smoothly with substrates bearing substitution in the 7th and 6th positions of the naphthyl ring, which afforded the desired products (31–33) in 41–83% yield with 84–94% ee. It was noted that the yields of 18 and 19 were low due to the significant production ( > 30%) of hydrolyzed byproduct 1-(1-isoquinolinyl)-2-naphthalenol, while the low yield of product 31 was attributed to incomplete conversion. Apart from the isoquinoline derived heterobiaryl triflates, the phthalazine structures were also found to be compatible in this catalytic system. Consequently, a series of heterobiaryl triflates based on phthalazine were synthesized then investigated using the standard conditions. Pleasingly, the incorporation of substitution in the 4th position of the phthalazine ring led to the target products (34–41) in 67–98% yield with 95–99% ee, which demonstrates the broad substrate scope of this methodology. It is noteworthy that alkynyl and alkene groups could also be tolerated (41 and 40). Finally, the absolute configuration of 4 was confirmed to be R by X-ray crystal diffraction analysis.

After finishing the investigation of arylamines and heterobiaryl triflates, we turned our attention to examine the scope of stronger nucleophilic alkylamines, which might accelerate the step of nucleophilic attack to the acylpalladium species B and B’, and thus potentially result in an adverse effect on enantioselectivity. Indeed, in an initial test using 1-butylamine in the Pd-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of racemic 1a only resulted in a trace amount of the desired product. Afterwards, we studied the effect of the reaction parameters systematically for the aforementioned transformation and established a set of conditions [7.5 mol% of Pd(acac)2, 12.0 mol% of (R, SFc)-L6, 3.0 equivalent of Cs2CO3, DME (0.5 mL), CO gas (10 bar), 50 oC for 18 h]. It provided the corresponding product 49 in 82% yield with 93% ee (see Supplementary Tables 10–15 for more details). Under these standard conditions, a large variety of alkylamines were tested in the Pd-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of racemic 1a, and the results were summarized in Fig. 3. The reaction appeared to be quite compatible with various types of alkylamines, where it consistently afforded the corresponding axially chiral amide products 50–71 in good to excellent yields (53–93%) and excellent enantioselectivities (83–99% ee). The substrates with haloaryl moieties, allylamine and propargyl amine, which might be sensitive to palladium catalysis also worked well without adverse effect on the reaction (58, 59, 63, 64); albeit the conditions for 63 were slightly changed. Interestingly, when using substrates bearing both arylamine and alkylamine groups, the reaction selectively took place on the alkylamine position under the presented reaction conditions (65 and 66). Functional groups such as cyano-, OTBS, and NBoc as well as heterocycles such as furan, thiophene, and pyridine were also compatible in the reaction and the corresponding products (55, 60, 62 and 67–71) were furnished in 53–93% yield with 85–99% ee. Finally, the absolute configuration of 52 was confirmed to be S by X-ray crystal diffraction analysis.

All reactions were performed in DME (0.5 mL), at 50 °C for 18 h in the presence of racemic heterobiaryl triflate 1a (0.1 mmol), alkylamine (0.3 mmol), Pd(acac)2 (0.0075 mmol), Cs2CO3 (0.3 mmol), (R, SFc)-L6 (0.012 mmol) and CO (10 bar). The yields were isolated yields for all products by column chromatography, and the ee was determined by HPLC using a chiral column. aTHF/DMA (0.5 mL/0.05 mL) were used instead of DME. THF = tetrahydrofuran, DMA = N, N-dimethylacetamide, DME = 1, 2-dimethoxyethane.

Next, the investigation into the scope of heterobiaryl triflates was conducted using 2-phenylethan-1-amine as the coupling partner in the present conditions. As shown in Fig. 4, substitution in the 4th, 5th, or 6th position of the isoquinoline ring has no effect on the yield and enantioselectivity. Also, functional groups such as Cl, CN and CHO were well tolerated in this Pd-catalyzed carbonylation reaction and afforded the desired products (72–76 and 78) in good yields (68–89%) with high enantioselectivities (88–94%). Notably, double aminocarbonylation occurred when the substrate had bromine substitution on both the isoquinoline and naphthyl rings, and provided the corresponding products 77a–81 in good yields and excellent enantioselectivities. Interestingly, the reaction of the substrate with bromine substitution in the 5th position of the isoquinoline ring afforded the mono- and double carbonylation products (77 and 77a) in 50% yield with 91% ee and 43% yield with 92% ee, respectively. The aminocarbonylation reactions of substrates bearing ester or ether groups in the 6th and 7th positions of the naphthyl ring, also proceeded efficiently and afforded the desired products 82–84 in good yields (56–87%) with excellent enantioselectivities (88–94% ee). Besides, the reactions using heterobiaryl triflates based on a phthalazine ring with functional groups such as amino, ether, alkenyl, and alkynyl also produced the desired carbonylation products (85–93) smoothly in moderate to high yields with 93–99% ee. Moreover, the heterobiaryl triflate containing methylpyridine was also suitable in the protocol and generated 94 in 79% yield with 91% ee.

All reactions were performed in DME (0.5 mL), at 50 °C for 18 h in the presence of racemic heterobiaryl triflate 1a (0.1 mmol), 3b (0.3 mmol), Pd(acac)2 (0.0075 mmol), Cs2CO3 (0.3 mmol), (R, SFc)-L6 (0.012 mmol) and CO (10 bar). The yields were isolated yields for all products by column chromatography, and the ee was determined by HPLC using a chiral column. aFrom substrate 1 h. bFrom substrate 1i. cFrom substrate 1j. dFrom substrate 1 s.

To gain more insight into this DyKAT aminocarbonylation, we performed mechanistic investigations. Firstly, the reactivity of different biaryl triflates with or without a nitrogen atom was investigated (Supplementary Fig. 26) under the standard conditions, and the results demonstrated the crucial role of the nitrogen atom in the heterocyclic ring. Then, the kinetic study for two set of catalytic systems with arylamine 2a and alkylamine 3b were performed under each standard conditions (Fig. 5). For the reaction using arylamine 2a as the nucleophile (Fig. 5a), the time dependence of yield and enantioselectivity of the recovered 1a and generation of 4 showed that the catalytic system Pd/(S,S)-L1 only have moderate selectivity for each enantiomer of 1a with an ineffective kinetic resolution process, followed by an enantioconvergent transformation via a DyKAT pathway after four hours. The reactions of virtually enantiopure (R)-1a using matched (S,S)-L1 and mismatched (R,R)-L1 as ligand under standard conditions were also carried out (Fig. 5c, left). The corresponding enantiomers of 4 were obtained in 71% and 24% yield with 99% and 80% ee respectively, which was consistent with the observed selectivity of racemic 1a in the presence of catalyst Pd/(S,S)-L1 (Fig. 5a). Nonetheless, in both cases the configuration of the major enantiomer of the carbonylative coupling product was controlled by the ligand, and only trace amount of racemization of recovered 1a was observed.

a Kinetic analysis of (rac)-1a with p-methylaniline. b Kinetic analysis of (rac)-1a with phenylethylamine. c Reactions with a matched or mismatched ligand. d Kinetic analysis of (R)-1a with p-methylaniline. e Kinetic analysis of (R)-1a with phenylethylamine. f Investigations into the racemization process of (R)-1a under different conditions.

Subsequently, the time-course study of alkylamine 3b was conducted under the standard conditions (Fig. 5b). Along with the consumption of 1a, both the yield of (S)-52 and the ee of recovered 1a (R configuration) increased within the first two hours. After that, the ee of recovered 1a kept ab. 40% until all the substrate (1a) was converted into (S)-52. These results suggested that the consumption rate of (S)-1a was faster than (R)-1a during the initial two hours due to the matched catalysts (R, SFc)-L6 with (S)-1a, and then the consumption rate of (R)-1a was faster than (S)-1a. To explain this observed unusual phenomenon, nearly enantiopure (R)-1a was subjected to the aminocarbonylation reaction using matched (S, RFc)-L6 and mismatched (R, SFc)-L6 as ligands (Fig. 5c, right). Surprisingly, a significant amount of racemization of (R)-1a was observed in both cases, illustrating the conversion of (R)-1a to (S)-1a during the reactions. To further prove this phenomenon, the kinetic studies of (R)-1a with p-methylaniline (Fig. 5d) and phenylethylamine (Fig. 5e) were performed under two sets of catalytic systems using matched ligands. According to the analysis of the kinetic profiles, it can be concluded that the conversion of (R)-1a to (S)-1a indeed occurred. Furthermore, the control experiment of (R)-1a for 18 h did not lead to obvious racemization, which demonstrated the relative configurational stability of 1a and excluded the dynamic kinetic resolution process (Fig. 5f, Conditions A and lementary Fig. 12, eq. 9). Even in the presence of Pd/L6, no obvious racemization was detected (Fig. 5f, Conditions B, C, and D). Notably, the ee of recovered (R)-1a significantly decreased to 15% when the reaction was performed under nitrogen atmosphere (Fig. 5f, Conditions E), while phenylethylamine (3b) did not led to the racemization of (R)-1a (Fig. 5f, Conditions F). All these outcomes proved that the reaction only starts in the presence of the amine nucleophile under CO atmosphere, and the conversion from (R)-1a to (S)-1a might occur through the oxidative addition, epimerization, and reductive elimination process. Finally, the configuration of the major enantiomer of the carbonylative coupling product was controlled by the ligand, and the enantioconvergent transformation mainly rely on the epimerization of the cyclopalladium intermediate.

During the study on the rotational energy barrier of axially chiral amide (R)-4, we noted that the ee of (R)-4 decreased quickly from 96% to 29% within 24 h (Fig. 6a, left), which contradicted with the achieved high ee values in the catalytic reactions. To identify which factor was critical, sample-taking reactions were conducted by adding different reactants, and the results revealed that the base Cs2CO3 played a key role in stabilizing the configuration of product 4 (Fig. 6a, right). To investigate the influence of base in further detail, a series of control experiments were performed. The time dependence of enantioselectivities of structurally similar ester 99 showed a much slower rate of racemization compared with amide 4 (Fig. 6b, red line vs black line), thus excluded the racemization pathway via the abovementioned quasi zwitterionic transition state (Fig. 1c, i) because of the stronger electrophilicity of the carbon atom in the ester group. Interestingly, the same experiment with methylated compound (R)-100 observed dramatically slow racemization (Fig. 6b, green line), which implied the NH group of amides might be responsible for the racemization process. We assumed the intramolecular hydrogen bond between the NH group of amides and the nitrogen atom of the isoquinoline ring might assist the rotation of axis. In fact, this phenomenon of weak bond assisted rotation of axis has been widely explored in molecular rotors106,107,108,109,110 and asymmetric catalysis111.

To obtain more evidence, a series of experiments on the thermal racemization of (R)-5, (R)-6, (R)-8, (R)-11 and (R)-17 were performed in parallel at 80 oC to evaluate the substituent effect on the rate of racemization (Fig. 6c). The results disclosed a linear correlation between log(kX/kH) and the Hammett constant (σ para) with a positive slope of 0.87, implying that the axially chiral amides bearing an electron-withdrawing substituent on the arylamine phenyl ring racemized faster, which is probably due to the stronger hydrogen bond between the NH group and the nitrogen atom. Moreover, the racemization experiments of (R)-4 (96% ee) were also conducted in methanol and dichloromethane at room temperature independently for 30 days, and the ee decreased to 89% in dichloromethane while no racemization was observed in MeOH, suggesting that the intramolecular hydrogen bond was probably disrupted by protonic solvent MeOH. Based on above results and literature report105, we propose that the intramolecular hydrogen bond could accelerate the axis rotation of amide products to racemize; however, the base may inhibit this rotation by disrupting the hydrogen bond, which was in accordance with the high ee values in the catalytic reactions.

One of the advantages of carbonylation reactions is to scale easily, thus the reaction using 10 mmol racemic 1a was carried out to afford the corresponding product (S)-69 in 80% yield with 95% ee, which could be applied directly as a chiral pincer N,N,N-ligand without further modification (Fig. 7a). To prove the utility of the achieved atropisomeric heterobiaryl amides as chiral ligands, a series of transition metal catalyzed enantioselective reactions were performed. For instance, the reactions of Cu-catalyzed enantioconvergent radical C(sp3)-N bond formation112 of 101 and 102 using (R)-26 or (S)-69 as the ligand, generated product 103 in 71% and 66% yields with 80/20 and 79.5/20.5 er, respectively (Fig. 7b). As a comparison, almost no product was detected using (S)-52 as the ligand, suggesting the importance of the N,N,N-ligand in this transformation. In addition, (R)-26 could also be applied in the Cu-catalyzed construction of a C(sp3)-P bond113 using alkylbromide 104 and diethyl phosphite 105, which provided product 106 in 52% yield with 71/29 er (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, three component coupling of alkene 107, diethyl phosphite 105, and tertiary alkylbromide 108 could also be catalyzed by Cu/(R)-26 to afford the product 109 albeit with 29% yield and 69/31 er at the current stage114 (Fig. 7d).

Discussion

In conclusion, we have developed a highly efficient Pd-catalyzed enantioconvergent aminocarbonylation of racemic heterobiaryl triflates with amines through a dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation process. This methodology allows for rapid construction of previously unreported axially chiral heterobiaryl amides in good to excellent yield (up to 98%) with excellent enantioselectivities (up to 99% ee) with a broad substrate scope and excellent compatibility of various functional groups. Kinetic studies revealed that the reaction proceeded via DyKAT, and the enantiomers of the substrates could be converted reversibly through the oxidative addition, epimerization, and reductive elimination process. Thermal racemization investigations discovered that the intramolecular hydrogen bond accelerated the axis rotation of products, while the utilization of base could inhibit this process by disrupting the hydrogen bond, allowing for high enantioselectivity. The utility of the products was demonstrated by applying some of them as chiral N,N,N-ligand in Cu-catalyzed enantioselective construction of C(sp3)-X (N, P) bonds. Further applications of these ligands for more transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric reactions are ongoing in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure for Pd-catalyzed enantioconvergent aminocarbonylation of racemic heterobiaryl triflates with arylamines

In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, an oven-dried 4 mL vial equipped with a stir bar was charged with Pd(OAc) (2.24 mg, 0.01 mmol), (S,S)-L1 (3.38 mg, 0.012 mmol), heterobiaryl triflate (0.1 mmol), arylamine (0.2 mmol), and Cs2CO3 (97.7 mg, 0.3 mmol). The vial was closed by PTFE/white rubber septum (13 mm Septa) and phenolic cap and connected with atmosphere with a needle. Then, DCM/DCE (0.5/0.05 mL) was added via a syringe. Next, the vial was fixed in an alloy plate and placed inside a Parr 4760 series autoclave (300 mL) under a nitrogen atmosphere. At room temperature, the autoclave was flushed with carbon monoxide three times, and then carbon monoxide was charged to 10 atm. The reaction was heated to 80 oC for 18 h. Afterwards, the autoclave was cooled to room temperature and the pressure was released carefully. The reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by column chromatography on silica gel (eluting with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate) to yield the desired amide product.

Data availability

The authors declare that the experimental data and the characterization data for all the compounds generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information. Experimental details include the general information, preparation of heterobiaryl triflates, effect of reaction parameters, mechanistic experiments, racemization experiments, kinetic studies, synthetic application of the methodology, assignments of absolute configuration, NMR spectra and HPLC analysis (PDF). CCDC 2322372 (4) and 2322365 (52) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033. All other data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Kozlowski, M. C., Morgan, B. J. & Linton, E. C. Total synthesis of chiral biaryl natural products by asymmetric biaryl coupling. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 3193–3207 (2009).

Bringmann, G. & Tajuddeen, N. N, C-Coupled naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids: a versatile new class of axially chiral natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 38, 2154–2186 (2021).

Bringmann, G. & Menche, D. Stereoselective total synthesis of axially chiral natural products via biaryl lactones. Acc. Chem. Res. 34, 615–624 (2001).

Graff, J., Debande, T., Praz, J., Guénée, L. & Alexakis, A. Asymmetric bromine–lithium exchange: application toward the synthesis of natural product. Org. Lett. 15, 4270–4273 (2013).

Takaishi, K., Yasui, M. & Ema, T. Binaphthyl–bipyridyl cyclic dyads as a chiroptical switch. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 5334–5338 (2018).

Yang, H. & Tang, W. Enantioselective construction of ortho-sulfur- or nitrogen-substituted axially chiral biaryls and asymmetric synthesis of isoplagiochin D. Nat. Commun. 15, 4577–4577 (2022).

Noyori, R. & Takaya, H. BINAP: an efficient chiral element for asymmetric catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 23, 345–350 (1990).

Chen, Y., Yekta, S. & Yudin, A. K. Modified BINOL ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Rev. 103, 3155–3212 (2003).

Tang, W. & Zhang, X. New chiral phosphorus ligands for enantioselective hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 103, 3029–3070 (2003).

Knpfel, T. F., Aschwanden, P., Ichikawa, T., Watanabe, T. & Carreira, E. M. Readily available biaryl P, N ligands for asymmetric catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 5971–5973 (2004).

Malkov, A. V. et al. On the mechanism of asymmetric allylation of aldehydes with allyltrichlorosilanes catalyzed by QUINOX, a chiral isoquinoline N-Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5341–5348 (2008).

Bringmann, G., Mutanyatta-Comar, J., Knauera, M. & Abegaz, B. Knipholone and related 4-phenylanthraquinones: structurally, pharmacologically, and biosynthetically remarkable natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 25, 696–718 (2008).

Hughes, C., Prieto-Davo, A., Jensen, P. & Fenical, W. The Marinopyrroles, antibiotics of an unprecedented structure class from a marine streptomyces sp. Org. Lett. 10, 629–631 (2008).

Yalcouye, B., Choppin, S., Panossian, A., Leroux, F., Colobert, F. A concise atroposelective formal synthesis of (–)-steganon. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 18, 6285–6294 (2014).

Perveen, S. et al. Synthesis of axially chiral biaryls via enantioselective Ullmann coupling of ortho-chlorinated aryl aldehydes enabled by a chiral 2,2′-bipyridine ligand. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212108 (2022).

Hashimoto, T. & Maruoka, K. Design of axially chiral dicarboxylic acid for asymmetric mannich reaction of arylaldehyde n-boc imines and diazo compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 10054–10055 (2007).

Hashimoto, T., Hirose, M. & Maruoka, K. Asymmetric imino aza-enamine reaction catalyzed by axially chiral dicarboxylic acid: use of arylaldehyde N, N-dialkylhydrazones as acyl anion equivalent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 7556–7557 (2008).

Xu, B. et al. Catalytic asymmetric direct α-alkylation of amino esters by aldehydes via imine activation. Chem. Sci. 5, 1988–1991 (2014).

Wen, W. et al. Chiral aldehyde catalysis for the catalytic asymmetric. Activation Glycine Esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9774–9780 (2018).

Zhu, F. et al. Chiral aldehyde-nickel dual catalysis enables asymmetric α−propargylation of amino acids and stereodivergent synthesis of NP25302. Nat. Commun. 13, 7290 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Carbonyl catalysis enables a biomimetic asymmetric Mannich reaction. Science 360, 1438–1422 (2018).

Ma, J. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of pyroglutamic acid esters from glycinate via carbonyl catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10588–10592 (2021).

Hou, C. et al. Catalytic asymmetric α C(sp3)–H addition of benzylamines to aldehydes. Nat. Catal. 5, 1051–1068 (2022).

Xiao, X. & Zhao, B. Vitamin B6-based biomimetic asymmetric catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 1097–1117 (2023).

Lin, L. et al. Chiral carboxylic acid enabled achiral rhodium (III)-catalyzed enantioselective C−H functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 12048–12052 (2018).

Fukagawa, S., Kojima, M., Yoshino, T. & Matsunaga, S. Catalytic enantioselective methylene C(sp3)−H amidation of 8-alkyl quinolines using a Cp*RhIII/chiral carboxylic acid system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 18154–18158 (2019).

Zhou, T. et al. Efficient synthesis of sulfur-stereogenic sulfoximines via Ru(II)-catalyzed enantioselective C–H functionalization enabled by chiral carboxylic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6810–6816 (2021).

Zhou, Y.-B., Zhou, T., Qian, P.-F., Li, J.-Y. & Shi, B.-F. Synthesis of sulfur-stereogenic sulfoximines via Co (III)/chiral carboxylic acid-catalyzed enantioselective C–H Amidation. ACS Catal. 12, 9806–9811 (2022).

Wang, Q., Gu, Q. & You, S.-L. Enantioselective carbonyl catalysis enabled by chiral aldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 6818–6825 (2019).

Carmona, J. A., Rodriguez-Franco, C., Fernandez, R., Hornillos, V. & Lassaletta, J. M. Atroposelective transformation of axially chiral (hetero)biaryls. from desymmetrization to modern resolution strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 2968–2983 (2021).

Cheng, J., Xiang, S., Li, S., Ye, L. & Tan, B. Recent advances in catalytic asymmetric construction of atropisomers. Chem. Rev. 121, 4805–4902 (2021).

Qian, P., Zhou, T. & Shi, B.-F. Transition-metal-catalyzed atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral styrenes. Chem. Commun. 59, 12669–12684 (2023).

Zhang, H., Li, T., Liu, S. & Shi, F. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of atropisomers bearing multiple chiral elements: an emerging field. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202311053 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Direct synthesis of adipic acid esters via palladium-catalyzed carbonylation of 1,3-dienes. Science 366, 1514–1517 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Efficient palladium-catalyzed carbonylation of 1,3-dienes: selective synthesis of adipates and other aliphatic diesters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9527–9533 (2021).

Dong, K. et al. Rh(I)-catalyzed hydroamidation of olefins via selective activation of N–H bonds in aliphatic amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6053–6058 (2015).

Zhang, G., Gao, B. & Huang, H. Palladium-catalyzed hydroaminocarbonylation of alkenes with amines: a strategy to overcome the basicity barrier imparted by aliphatic amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 7657–7661 (2015).

Gao, B., Zhang, G., Zhou, X. & Huang, H. Palladium-catalyzed regiodivergent hydroaminocarbonylation of alkenes to primary amides with ammonium chloride. Chem. Sci. 9, 380–386 (2018).

Yang, H., Yao, Y., Chen, M., Ren, Z. & Guan, Z.-H. Palladium-catalyzed markovnikov hydroaminocarbonylation of 1,1-disubstituted and 1,1,2-trisubstituted alkenes for formation of amides with quaternary carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 7298–7305 (2021).

Bao, Z.-P., Li, C., Li, Y., Ding, Y. & Wu, X.-F. Palladium-catalyzed oxidative double alkoxycarbonylation of ethylene toward succinic acid derivatives. Green. Carbon 2, 205–208 (2024).

Dijik, L. et al. Data science-enabled palladium-catalyzed enantioselective aryl-carbonylation of sulfonimidamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20959–20967 (2023).

Faculak, M. S., Veatch, A. & Alexanian, E. Cobalt-catalyzed synthesis of amides from alkenes and amines promoted by light. Science 383, 77–81 (2024).

Hirschbeck, V., Gehrtz, P. & Fleischer, I. Regioselective thiocarbonylation of vinyl arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16794–16799 (2016).

Ai, H., Zhao, F., Geng, H. & Wu, X. Palladium-catalyzed thiocarbonylation of alkenes toward linear thioesters. ACS Catal. 11, 3614–3619 (2021).

Wu, F., Wang, B., Li, N., Ren, Z. & Guan, Z.-H. Palladium-catalyzed regiodivergent hydrochlorocarbonylation of alkenes for formation of acid chlorides. Nat. Commun. 14, 3167–3167 (2023).

Chami, K. et al. A visible light driven nickel carbonylation catalyst: the synthesis of acid chlorides from alkyl halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202213297 (2023).

Cao, Z., Wang, Q., Neumann, H. & Beller, M. Regiodivergent carbonylation of alkenes: selective palladium-catalyzed synthesis of linear and branched selenoesters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202313714 (2024).

Ali, B. E., Alper, H. Transition Metals for Organic Synthesis: Building Blocks and Fine Chemicals. 113–132 (Wiley, 2004).

Franke, R., Selent, D. & Börner, A. Applied hydroformylation. Chem. Rev. 112, 5675–5732 (2012).

Brennführer, A., Neumann, H. & Beller, M. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylation reactions of alkenes and alkynes. ChemCatChem 1, 28–41 (2009).

Yuan, Y. & Wu, X.-F. Generation and transformation of α-Oxy carbene intermediates enabled by copper-catalyzed carbonylation. Green. Carbon 2, 70–80 (2024).

Sakai, N., Mano, S., Nozaki, K. & Takaya, H. Highly enantioselective hydroformylation of olefins catalyzed by new phosphine phosphite-rhodium(I) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 7033–7034 (1993).

Yan, Y. & Zhang, X. A hybrid phosphorus ligand for highly enantioselective asymmetric hydroformylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 7198–7202 (2006).

Wang, X. & Buchwald, S. L. Rh-catalyzed asymmetric hydroformylation of functionalized 1,1-disubstituted olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19080–19083 (2011).

Chikkali, S. H., Bellini, R., Bruin, B., Vlugt, J. I. & Reek, J. N. H. Highly selective asymmetric rh-catalyzed hydroformylation of heterocyclic olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 6607–6616 (2012).

Abrams, M. L., Foarta, F. & Landis, C. R. Asymmetric hydroformylation of z-enamides and enol esters with rhodium-bisdiazaphos catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14583–14588 (2014).

Li, S., Zhang, D., Zhang, R., Bai, S.-T. & Zhang, X. Rhodium-catalyzed chemo-, regio- and enantioselective hydroformylation of cyclopropyl-functionalized trisubstituted alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202206577 (2022).

Peng, J., Liu, X., Li, L. & Wu, X.-F. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective carbonylation reactions. Sci. China Chem. 65, 441–461 (2022).

Li, J. & Shi, Y. Progress on transition metal catalyzed asymmetric hydroesterification, hydrocarboxylation, and hydroamidation reactions of olefins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 6757–6773 (2022).

Xiao, W.-J. & Alper, H. First examples of enantioselective palladium-catalyzed thiocarbonylation of prochiral 1,3-conjugated dienes with thiols and carbon monoxide: efficient synthesis of optically active β, γ-unsaturated thiol esters. J. Org. Chem. 66, 6229–6233 (2001).

Wang, X. et al. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective thiocarbonylation of styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 12264–12270 (2019).

Yao, Y. et al. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric markovnikov hydroxycarbonylation and hydroalkoxycarbonylation of vinyl arenes: synthesis of 2-arylpropanoic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 23117–23122 (2021).

Yao, Y. et al. Asymmetric markovnikov hydroaminocarbonylation of alkenes enabled by palladium-monodentate phosphoramidite catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 85–91 (2021).

Ren, X. et al. Asymmetric alkoxy- and hydroxy-carbonylations of functionalized alkenes assisted by β-carbonyl groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 17693–17700 (2021).

Tian, B., Li, X., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Asymmetric palladium-catalyzed oxycarbonylation of terminal alkenes: efficient access to β-hydroxy alkylcarboxylic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14881–14886 (2021).

Ji, X., Shen, C., Tian, X., Zhang, H. & Dong, K. Asymmetric double hydroxycarbonylation of alkynes to chiral succinic acids enabled by palladium relay catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204156 (2022).

Chen, J. & Zhu, S. Nickel-catalyzed multicomponent coupling: synthesis of α-chiral ketones by reductive hydrocarbonylation of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 14089–14096 (2021).

Yu, R., Cai, S., Li, C. & Fang, X. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric hydroaryloxy- and hydroalkoxycarbonylation of cyclopropenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200733 (2022).

Yuan, Y. et al. Copper-catalyzed carbonylative hydroamidation of styrenes to branched amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22441–22445 (2020).

Yuan, Y., Zhang, Y., Li, W., Zhao, Y. & Wu, X.-F. Regioselective and enantioselective copper-catalyzed hydroaminocarbonylation of unactivated alkenes and alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309993 (2023).

Hu, H. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of 2-oxindole spirofused lactones and lactams by heck/carbonylative cylization sequences: method development and applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9225–9229 (2019).

Yuan, Z. et al. Constructing chiral bicyclo[3.2.1]octanes via palladium-catalyzed asymmetric tandem Heck/carbonylation desymmetrization of cyclopentenes. Nat. Commun. 11, 2544–2544 (2020).

Chen, M. et al. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective heck carbonylation with a monodentate phosphoramidite ligand: asymmetric synthesis of (+)-Physostigmine, (+)-Physovenine, and (+)-Folicanthine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 12199–12205 (2020).

Wu, T., Zhou, Q. & Tang, W. Enantioselective α-carbonylative arylation for facile construction of chiral spirocyclic β, β′-diketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9978–9983 (2021).

Zhang, D. et al. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular heck carbonylation reactions: asymmetric synthesis of 2-oxindole ynones and carboxylic acids. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202103670 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. Pd-catalyzed asymmetric 5-exo-trig cyclization/cyclopropanation/carbonylation of 1,6-enynes for the construction of chiral 3-azabicyclo [3.1.0] hexanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202211988 (2023).

Zhang, Q., Xue, X., Hong, B. & Gu, Z. Torsional strain inversed chemoselectivity in a Pd-catalyzed atroposelective carbonylation reaction of dibenzothiophenium. Chem. Sci. 13, 3761–3765 (2022).

Han, J. et al. Enantioselective double carbonylation enabled by high-valent palladium catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21800–21807 (2022).

Alcocka, N. W., Brown, J. M. & Htimes, D. I. Synthesis and resolution of 1-(2-diphenylphosphino-1-naphthyl) isoquinoline; a P-N chelating ligand for asymmetric catalysis. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry 4, 743–756 (1993).

McCarthy, M., Goddard, R. & Guiry, P. J. The preparation and resolution of 2-phenyl-Quinazolinap, a new atropisomeric phosphinamine ligand for asymmetric catalysis. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry 10, 2797–2807 (1999).

Cardoso, F. S. P., Abboud, K. A. & Aponick, A. Design, preparation, and implementation of an imidazole-based chiral biaryl P, N-ligand for asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14548–14551 (2013).

Jiang, P., Wu, S., Wang, G., Xiang, S. & Tan, B. Synthesis of axially chiral QUINAP derivatives by ketone-catalyzed enantioselective oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309272 (2023).

Ros, A. et al. J. M. Dynamic kinetic cross-coupling strategy for the asymmetric synthesis of axially chiral heterobiaryls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15730–15733 (2013).

Bhat, V., Wang, S., Stoltz, B. M. & Virgil, S. C. Asymmetric synthesis of QUINAP via dynamic kinetic resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16829–16832 (2013).

Ramírez-López, P. et al. Synthesis of IAN-type N, N-ligands via dynamic kinetic asymmetric buchwald–hartwig amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12053–120556 (2016).

Carmona, J. et al. Dynamic kinetic asymmetric heck reaction for the simultaneous generation of central and axial chirality. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11067–111075 (2018).

Jiang, X. et al. Construction of axial chirality via asymmetric radical trapping by cobalt under visible light. Nat. Catal. 5, 788–797 (2022).

Xiong, W. et al. Dynamic kinetic reductive conjugate addition for construction of axial chirality enabled by synergistic photoredox/cobalt catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 7983–7991 (2023).

Sun, T. et al. Nickel-catalyzed enantioconvergent transformation of anisole derivatives via cleavage of C–OME bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 15721–15728 (2023).

Dong, H. & Wang, C. Cobalt-catalyzed asymmetric reductive alkenylation and arylation of heterobiaryl tosylates: kinetic resolution or dynamic kinetic resolution? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 26747–26755 (2023).

Chen, X.-W. et al. Atropisomeric Carboxylic Acids Synthesis via Nickel-Catalyzed Enantioconvergent Carboxylation of Aza-biaryl Triflates with CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202403401 (2024).

Ramírez-López, P. et al. A dynamic kinetic c–p cross–coupling for the asymmetric synthesis of axially chiral P, N ligands. ACS Catal. 6, 3955–3964 (2016).

Kakiuchi, F., Gendre, P. L., Yamada, A., Ohtaki, H. & Murai, S. Atropselective alkylation of biaryl compounds by means of transition metal-catalyzed C–H/olefin coupling. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry 11, 2647–2651 (2000).

Zheng, J. & You, S.-L. Construction of axial chirality by rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric dehydrogenative heck coupling of biaryl compounds with alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 13244–13247 (2014).

Zheng, J., Cui, W., Zheng, C. & You, S.-L. Synthesis and application of chiral spiro cp ligands in rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric oxidative coupling of biaryl compounds with alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5242–5245 (2016).

Hornillos, V. et al. Synthesis of axially chiral heterobiaryl alkynes via dynamic kinetic asymmetric alkynylation. Chem. Commun. 53, 14121–14124 (2016).

Wang, Q., Cai, Z., Liu, C., Gu, Q. & You, S.-L. Rhodium-catalyzed atroposelective C–H arylation: efficient synthesis of axially chiral heterobiaryls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 9504–9510 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. Rhodium-catalyzed atroposelective oxidative C–H/C–H cross-coupling reaction of 1-aryl isoquinoline derivatives with electron-rich heteroarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15678–15685 (2020).

Romero-Arenas, A. et al. Ir-catalyzed atroposelective desymmetrization of heterobiaryls: hydroarylation of vinyl ethers and bicycloalkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2628–2639 (2020).

Zheng, D., Zhang, W., Gu, Q. & You, S.-L. Rh (III)-catalyzed atroposelective C–H iodination of 1-aryl isoquinolines. ACS Catal. 13, 5127–5134 (2023).

Yang, B., Gao, J., Tan, X., Ge, Y. & He, C. Chiral PSiSi-ligand enabled iridium-catalyzed atroposelective intermolecular C−H silylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202307812 (2023).

Vázquez-Domínguez, P., Romero-Arenas, A., Fernández, R., Lassaletta, J. M. & Ros, A. ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydroarylation of alkynes for the synthesis of axially chiral heterobiaryls. ACS Catal. 13, 42–48 (2023).

Velázquez, M., Fernández, R., Lassaletta, J. M. & Monge, D. Asymmetric dearomatization of phthalazines by anion-binding catalysis. Org. Lett. 25, 8797–8802 (2023).

Hornillos, V. et al. Dynamic kinetic resolution of heterobiaryl ketones by zinc-catalyzed asymmetric hydrosilylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3777–3778 (2018).

Huth, S. E., Stone, H., Crotti, S. & Miller, S. On the ability of the N–O Bond to support a stable stereogenic axis: peptide-catalyzed atroposelective N-oxidation. J. Org. Chem. 88, 12857–12862 (2023).

Roussel, C. et al. Atropisomerism in the 2-arylimino-N-(2-hydroxyphenyl)thiazoline series: influence of hydrogen bonding on the racemization process. J. Org. Chem. 73, 403–411 (2008).

Dial, B. E., Rasberry, R. D., Bullock, B. N., Smith, M. & Shimizu, K. D. Guest-accelerated molecular rotor. Org. Lett. 13, 244–247 (2011).

Dial, B. E., Pellechia, P. J., Smith, M. & Shimizu, K. D. Proton grease: an acid accelerated molecular rotor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3675–3678 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. A multistage rotational speed changing molecular rotor regulated by pH and metal cations. Nat. Commun. 9, 1953 (2018).

Shimizu, K. D. et al. Large transition state stabilization from a weak hydrogen bond. Chem. Sci. 11, 7487–7494 (2020).

Fugard, A. J., Lahdenperä, A. S. K., Tan, J. S. J., Mekareeya, A. & Smith, M. Hydrogen-bond-enabled dynamic kinetic resolution of axially chiral amides mediated by a chiral counterion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2795–2798 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Copper-catalyzed enantioconvergent radical C(sp3)–N cross-coupling of activated racemic alkyl halides with (hetero)aromatic amines under ambient conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 14686–14696 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. A general copper-catalyzed enantioconvergent radical Michaelis–Becker-type C(sp3)–P cross-coupling. Nat. Synth. 2, 430–438 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Copper-catalyzed chemo- and enantioselective radical 1,2-carbophosphonylation of styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218523 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1507500, J.L.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (22201173, J.L. and 22201175, S.G.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (23X010301599, J.L.), and Shanghai Rising-Star Program (21QA1404900, J.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. conceived and directed the project. L.S. and S.G. performed the experiments and collected the data. J.L., L.S., and S.G. discussed the project. J.L. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, L., Gao, S. & Liu, J. Enantioconvergent synthesis of axially chiral amides enabled by Pd-catalyzed dynamic kinetic asymmetric aminocarbonylation. Nat Commun 15, 7248 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51717-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51717-8