Abstract

Brain-wide profiling of diverse biological components is fundamental for understanding complex brain pathology. Despite the availability in whole-brain imaging, it is still challenging to conduct multiplexed, brain-wide analysis with current tissue clearing techniques. Here, we propose SOLID, a hydrophobic tissue clearing method that can minimize tissue distortion while offering impressive clearing performance. SOLID achieves high-quality imaging of multi-color labeled mouse brain, and the acquired datasets can be effectively registered to the Allen Brain Atlas via commonly-used algorithms. SOLID enables generation of neural and vascular maps within one mouse brain, as well as tracing of specific neural projections labeled with viruses. SOLID also allows cross-channel investigations of β-amyloid plaques and neurovascular lesions in the reconstructed all-in-one panorama, providing quantitative insights into structural interactions at different stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Altogether, SOLID provides a robust pipeline for whole-brain mapping, which may widen the utility of tissue clearing techniques in diverse neuroscience research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mammalian brain is a highly complex system composed of diverse cellular circuits. Precise annotation and identification of diverse biological components are crucial for an in-depth understanding of complex brain functions and pathogenic mechanisms underlying different brain diseases1. In recent years, substantial advancements in tissue clearing techniques2, along with the integration of modern fluorescent labeling techniques3 and light-sheet imaging techniques4,5,6, have enabled brain-wide imaging of fluorescent-labeled structures at the cellular level. To date, various tissue clearing methods have been developed based on distinct strategies7. Solvent-based methods, also known as hydrophobic clearing methods, can achieve the highest tissue transparency within a short period. In recent years, several advanced solvent-based methods have been developed, such as uDISCO (Ultimate DISCO)8, iDISCO+ (Immunolabeling-enabled DISCO)9,10, PEGASOS (Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-associated solvent system)11, FDISCO (DISCO with superior fluorescence-preserving capability)12, vDISCO (Nanobody(VHH)- boosted DISCO)13,14,15, wildDISCO16 and SHANEL (Small-micelle-mediated human organ efficient clearing and labeling)17,18. Aqueous-based methods usually refer to hydrophilic and hydrogel-based methods, such as CUBIC (Clear unobstructed brain imaging cocktails)/F-CUBIC (Adding formamide to CUBIC)19,20,21, CLARITY (Clear lipid-exchanged acrylamide-hybridized rigid imaging/immunostaining/in situ hybridization-compatible tissue-hydrogel)22,23, SHIELD (Stabilization to harsh conditions via intramolecular epoxide linkages to prevent degradation)24, OPTIClear (Optical properties-adjusting tissue-clearing agent)/Accu-OptiClearing25,26, EZClear27, Ce3D (Clearing-enhanced 3D microscopy)28 and MACS (MXDA-based aqueous clearing system)29, allowing for less tissue distortion and better preservation of endogenous signals. Up to date, both solvent- and aqueous-based clearing methods have become valuable tools for 3D visualization of diverse biological events within the mammalian brains30.

Despite the success of whole-brain imaging, certain challenges prevent further brain-wide profiling of desired structures based on the brain datasets acquired using most tissue clearing techniques. These challenges may be largely attributed to the limitations of existing tissue clearing techniques that lead to huge difficulties in implementing reliable registration to define the anatomical boundaries of underlying brain structures. For example, solvent-based methods usually allow high-quality imaging of the whole brain with complete transparency. However, tissue distortion resulting from thorough dehydration prevents the registration of imaging data to a common reference brain atlas, which is the first and most critical step for conducting brain-wide quantification. Although many aqueous-based methods allow for the maintenance of tissue size after clearing, the limited transparency considerably degrades the image quality in deep brain regions, resulting in the lack of important cellular information required for registration and quantification. To overcome the obstacle that prevents the tissue clearing techniques from brain mapping applications, researchers have used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reconstruction31, deep learning32, tissue expansion33 or whole-mount immunolabeling10,34 and succeeded in whole-brain profiling of immediate-early genes (IEGs)10, vasculature34 or cell population33 individually, based on different tissue clearing pipelines. However, the requirement of customized instruments, highly specialized machine-learning frameworks and unaffordable 3D immunolabeling raise rather high thresholds for the application of the abovementioned techniques in routine experiments. Moreover, existing studies have reported the identification of a single structure (e.g., the vasculature) with two or more channels. Given that the number of channels in the visible range is rather limited, this may prevent multi-color imaging and cross-channel analysis of diverse structures within the same brain.

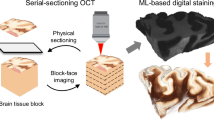

In this study, we developed SOLID (Suppressing tissue distortion based on synchronized dehydration/delipidation treatment with 1,2-hexanediol [1,2-HxD] mixtures) to overcome the abovementioned problems. SOLID is a versatile tissue clearing method designed for both multi-color visualization and global analysis of diverse structures within healthy and diseased brains. We effectively integrated tissue delipidation with tissue dehydration by designing a graded series of 1,2-HxD solutions and successfully compensated the severe tissue shrinkage led by the gradient dehydration. Consequently, SOLID results in not only complete tissue transparency and good fluorescence preservation but also minimal distortion for diverse tissues. Owing to these unique advantages, SOLID enables multi-color imaging of the entire mouse brain at cellular resolution, as well as whole-brain profiling based on the registration of imaging data to a reference brain atlas35 (Allen Brain Atlas [ABA]) using a series of readily available pipelines. We used SOLID to generate neural and vascular maps with standard anatomical annotations from ABA based on multi-color datasets. In addition, we conducted brain-wide profiling of both retrograde and antegrade neural projections from specific brain regions labeled with viruses. Notably, we demonstrated the applicability of SOLID in assessing the topological remodeling of multiple structures during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in mouse models. The findings of this study suggest that SOLID substantially decreases the threshold for brain-wide mapping of diverse structures with regional annotations. Consequently, SOLID may enhance the utility of tissue clearing techniques in diverse neuroscience applications, such as the assessment of gene expression patterns, brain regional anatomy and mapping of desired neural circuits.

Results

Development of SOLID pipeline with a synchronized delipidation/dehydration strategy to reduce tissue shrinkage

Severe tissue shrinkage is largely attributed to the gradient dehydration procedure in traditional solvent-based clearing protocol. We speculated that transient tissue expansion caused by delipidation at the beginning of dehydration might overcome the subsequent tissue shrinkage and prevent tissue deformation after clearing. Based on this hypothesis, we attempted to identify reagents exhibiting robust delipidation and dehydration abilities at lower and higher concentrations, respectively. We identified an aliphatic diol36 named 1,2-HxD that might possess these abilities owing to its strong capability to remove lipids at low concentrations20. As anticipated, 30% 1,2-HxD solution exhibited substantially stronger delipidation ability than traditional reagents used for dehydration, including methanol, ethanol, tert-butanol (TB) and tetrahydrofuran (THF) (Fig. 1A, B). Compared with dehydration in TB and THF, that in 30% 1,2-HxD solution resulted in reduced tissue shrinkage and did not influence the final tissue transparency (Fig. 1C). Consistent with our hypothesis, tissue expansion caused by 1,2-HxD at a low concentration effectively improved the subsequent tissue shrinkage (Fig.1D).

A Bright-field images of the cleared mouse hemispheres treated with different reagents at a concentration of 30%, including 1,2-hexanediol (1,2-HxD), methanol, ethanol, tert-butanol (TB) and tetrahydrofuran (THF). B Quantitative analysis of relative transparency for different cleared samples shown in (A) (n = 3 samples). P (1,2-HxD vs. Methanol)<0.0001; P (1,2-HxD vs. Ethanol)<0.0001; P (1,2-HxD vs. TB) < 0.0001; P (1,2-HxD vs. THF) < 0.0001. C Representative images of the whole mouse brains at indicated time points during different dehydration steps. D Quantitative analysis of changes in the relative sample size during dehydration (n = 3 samples). E The established SOLID pipeline. F Bright-field images and traced outline of the whole mouse brains before and after SOLID clarification. G 3D fluorescence images of Thy1-GFP-M mouse brains (green) cleared with indicated methods (from 3 replicates), the total imaging depth for each method is indicated. H Optical sections of acquired SOLID brain datasets at the indicated imaging depth. Magnified images of different regions of interest (ROI) are shown. All values are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance in (B) (***P < 0.001) was assessed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, we investigated whether 1,2-HxD was compatible with common fluorescent proteins. Although 30–90% 1,2-HxD solutions did not quench GFP signals, pure 1,2-HxD decreased the fluorescence intensity, suggesting that additional optimisation was required (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). Given that TB is harmless to endogenous fluorescence, we used a mixture of 90% 1,2-HxD and 10% TB instead of pure 1,2-HxD for the final dehydration step and successfully retained the fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). To identify the optimal refractive index (RI) matching solution for the dehydrated samples, we took account of the fluorescence preservation ability of various common organic solutions. We identified the BBPN solution as the ideal candidate, which was composed of benzyl benzoate, polyethylene glycol methacrylate 500 (PEGMMA500) and N-butyldiethanolamine in a ratio of 75:20:5 (Supplementary Fig. 1C). BBPN exhibited the highest fluorescence level of all tested solutions (Supplementary Fig. 1D). Finally, we adjusted the pH of each dehydration solution by adding 2% N-butyldiethanolamine, which not only enhanced the final fluorescence quality but also facilitated final clearing performance (Supplementary Fig. 1E). We named this clearing strategy SOLID. Given that 1,2-HxD at a low concentration possesses obvious lipid-removing ability, we also developed the SOLID-Deep Labeling protocol (SOLID-DL) based on 1,2-HxD mixtures to facilitate deep tissue labeling with fluorescent dyes and antibodies. We compared the labeling performance of SOLID-DL with two well-established protocols using typical nucleic dye and antibody. As shown, SOLID-DL could facilitate the penetration of TO-PRO-3 nucleic dye within the whole brain in 3D, more effective than those achieved by CUBIC-HistoVIsion (HV) and iDISCO+ protocol (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). As for immunolabeling, it could be seen that the IBA1 signals were evenly distributed throughout the brain sample (Supplementary Fig. 2C), therefore IBA1 was considered suitable for the evaluation of antibody penetration efficiency. SOLID-DL could achieve an antibody penetration rate at about 200 μm/d in 12 d labeling procedure, slightly higher than other two protocols in our tests (Supplementary Fig. 2C). SOLID-DL was also tested to be effective for anti-GFP counterstaining of an entire Thy1-GFP-M mouse brain with prolonged incubation time (18 d) (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Finally, SOLID-DL was proved to be compatible with a series of commonly-used antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 2E).

After the successful establishment of SOLID pipeline (Fig. 1E), we compared the clearing abilities of SOLID with a series of pioneering tissue clearing methods, including both solvent-based and aqueous-based methods. All tested methods successfully clarified the mouse brains with different level of transparency and size change. However, only SOLID successfully achieved the dual objective of achieving high transparency level while effectively maintaining sample size of mouse brains, a task challenging for alternative clearing methods (Fig. 1F, Supplementary Fig. 3). Images reconstructed using micro-CT also revealed no evident changes in the size of the brain in each dimension after clearing using SOLID (Supplementary Fig. 4A, B). Furthermore, the mouse brain samples cleared using SOLID achieved an imaging depth of >6000 μm, whereas those cleared using other solvent-based methods achieved an imaging depth of <4500 μm owing to the overall tissue shrinkage (Fig. 1G, H). Though the imaging depth was increased, SOLID still delivered a higher signal-to-background ratio in deep brain regions due to high level transparency (Supplementary Fig. 4C, D).

In addition to mouse brain, SOLID was also proved to be more effective in clearing other mouse internal organs compared to other methods tested (Supplementary Fig. 5A–C). Notably, SOLID effectively cleared whole neonatal and adult mouse bodies containing hard bones, resulting in complete transparency with only passive immersion (Supplementary Fig. 5D). Furthermore, SOLID successfully cleared an adult pig hemisphere with complete transparency and minor tissue shrinkage (Supplementary Fig. 5E).

SOLID was tested to be well compatible with a series of fluorescent signals (Supplementary Fig. 6), including fluorescent dyes (e.g., nucleic acid dyes including DAPI, TO-PRO-3, and other dyes including wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555 (WGA-AF555) and DANIR-8c), endogenous fluorescent proteins (GFP and YFP), and immunolabeling signals (GFAP and NeuN).

SOLID enables multi-color visualization of the whole mouse brain at cellular resolution

Given the good performance of SOLID in brain-wide imaging, we combined it with different fluorescent labeling techniques for simultaneous visualization of diverse structures. We employed the commonly-used Thy1-YFP-H transgenic mice. We labeled the entire vascular network in Thy1-YFP-H mouse brains and counterstained the harvested mouse brains with TO-PRO-3 using SOLID-DL. After clarification, we simultaneously visualized the neural and vascular structures as well as cell distribution within one mouse brain (Fig. 2A–C, Supplementary Movie 1). As shown in Fig. 2D, the overlaid image facilitated the assessment of the global distribution of pyramidal neurons, blood vessels and cell nuclei at the whole-brain scale. Individual optical sections revealed that the vascular structures and cell nuclei were completely and uniformly labeled across the entire brain (Fig. 2E, F). Notably, the resolution of acquired images was sufficient to distinguish individual neurons, small capillaries and cell nuclei (Fig. 2G, H).

A 3D reconstruction of neural distribution (green). B 3D reconstruction of the vasculature (glow). C 3D reconstruction of cell distribution (blue). D Three-channel rendering of the labeled neurons, vasculature and cell nuclei shown in (A–C) (from >3 replicates). Shadings represent the position of different cortical /horizontal plane images shown in (E, F). E Selected horizontal plane images indicated in (D). F Selected cortical plane images marked in (D). G Magnification of the boxed region (dark blue box) marked in (D). Shading represents the position of fluorescence image of selected plane shown in (H). H Fluorescence images of each channel marked in (G), revealing effective identification of individual neurons, capillaries and cell nuclei. White rectangle represents the magnification of indicated area.

A previous study suggested that young tissues suffer more serious deformation during dehydration10. To assess the ability of SOLID in preserving internal structures of neonatal mice, we also compared the morphology preservation performance of SOLID with several other clearing methods on cleared brain from young mice. Unlike other solvent-based clearing methods leading to obvious tissue collapses on cortex region, SOLID achieved high-level performance in preserving the morphology of neonatal mouse brains (Supplementary Fig. 7A, B). SOLID was then proved to be capable of mapping the overall vascular and cellular structures of the entire neonatal body (Supplementary Fig. 7C–E, Supplementary Movie 2). Blood vessels within different tissues, such as the brain (Supplementary Fig. 7F), spinal cord (Supplementary Fig. 7G), ribs (Supplementary Fig. 7H) and intestines (Supplementary Fig. 7I), and cellular structures for the dorsal root ganglia (Supplementary Fig. 7J), were clearly identified.

Registration of SOLID brain datasets to ABA using diverse registration methods

As reported previously, tissue distortion largely prevents automated image registration for brain datasets acquired for cleared samples10. To verify whether SOLID could facilitate automated image registration, we labeled the mouse brains with nucleic acid dye and cleared them using SOLID and several other solvent-based methods. We also involved several typical aqueous-based clearing methods, including SHIELD, EZClear and F-CUBIC, which are known for preserving sample size. In our hands, EZClear and SHIELD allowed whole-brain imaging with varying degrees of image blur in the central part, whereas F-CUBIC-processed brains were blurred in most brain regions due to insufficient tissue transparency (Supplementary Fig. 8). Whole-brain imaging datasets were acquired and automatically registered to standardised ABA using four registration methods without further modifications, including aMAP37, ClearMap10, MIRACL (Multimodal image registration and connectivity analysis)38 and BIRDS (Bi-channel image registration and deep-learning segmentation)39. Datasets for SOLID-cleared mouse brains could be effectively aligned to ABA using the four registration methods tested (Fig. 3A, B). However, datasets for other methods exhibited evident misalignment in many typical regions (e.g., the dentate gyrus and cortex region) across both horizontal and cortical planes (Fig. 3C, D). The calculation of Dice score for 5 selected main brain regions revealed the superiority of SOLID over other methods in brain registration (Fig. 3E). Additionally, SOLID also achieved better performance than other solvent-based clearing methods in registering typical sub-cortex regions, including two solid brain areas and three brain ventricles (Supplementary Fig. 9).

A Representative 3D reconstruction of the registered SOLID brain datasets for the cell nuclei channel (from 4 replicates). B Representative horizontal and cortical sections from SOLID brain datasets aligned using different registration methods. White rectangles indicate two ROIs. C Magnified images in the ROI1 marked in (B) from different registered brain datasets. D Magnified images in the ROI2 marked in (B) from different registered brain datasets. E Quantifications of the Dice scores of selected five brain regions from brain datasets of different clearing protocols registered by the four registration methods (n = 4 samples), including hippocampal formation (HPF), hindbrain (HB), Caudoputamen (CP), Isocortex (Iso), and midbrain (MB). Box plot: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

SOLID facilitates precise construction of a neurovascular map for assessing the distribution of labeled neurons and blood vessels

With SOLID, we constructed a neurovascular map within the same brain at cellular resolution without the use of any customized processing procedure (Fig. 4A). To lower the technical barrier as much as possible, we employed the tools that are well-established and readily-available to recognize neural cells (BIRDS-Imaris39) and extract vascular features (VesselExpress40), respectively. For VesselExpress toolbox, a thorough parameter configuration should be performed to select the optimal parameter for vascular extraction based on SOLID brain datasets (Supplementary Fig. 10). With these tools, we successfully generated a standard digital atlas containing the structural information of pyramidal neurons, blood vessels and cell nuclei from the same brain (Fig. 4B). Individual brain regions could be extracted from the 3D anatomical reconstruction, such as Isocortex (Iso), hippocampal formation (HPF), midbrain (MB), hindbrain (HB), olfactory area (OLF), cerebral nuclei (CNU), thalamus and hypothalamus (TH and HY) and cerebellum (CB) (Fig. 4C). After proper segmentation of neurons (Supplementary Fig. 11A) and vascular structures (Supplementary Fig. 11B) and adoption of anatomical annotations in ABA (Supplementary Fig. 12A, B), a 3D neural and vascular atlas was generated for a single brain at cellular/single-capillary resolution (Fig. 4D–G, Supplementary Movie 3). The cell number and density of neuronal somata in each brain region could be estimated based on cell detection and counting (Fig. 4H), which revealed similar distribution trends with a previous study41. In addition, vessel parameters such as vessel length density, branch point density (Fig. 4I), average branch diameter and vessel tortuosity (Supplementary Fig. 12C) could be quantified for each brain region with the help of VesselExpress toolbox. As shown from the side-by-side comparison, the quantified vessel parameters (including branch point density, vessel length density and vessel tortuosity) in four main brain regions demonstrate high consistency with results from ref. 40 (Supplementary Fig. 13A). The mean value and standard deviation of branch diameter obtained in this study was slightly higher than results from ref. 40, probably because we included all large vessels within entire brain regions for quantification. Additionally, we performed a thorough comparison regarding branch point density with results obtained from ref. 34 within more than 80 sub-brain regions, and also found good consistency in most regions (Supplementary Fig. 13B).

A The overall experimental pipeline. Part of this image is created with MedPeer (www.medpeer.cn). B A 3D digital atlas of the whole brain generated based on the cell nuclei channel with region-based color-coding Allen CCFv3. C Segmented brain regions from the established digital atlas. D Generation of a 3D neural map. E Individual planes for the generated neural map at the indicated location in (D), along with further magnification of the boxed region (white box) marked in plane 1. F Generation of a 3D vascular map. G Individual planes for the generated vascular map at the indicated location in (F), along with further magnification of the boxed region (white box) marked in plane 1. H Quantitative analysis of the cell number and density of 87 main anatomical clusters in ABA (n = 4 samples). I Quantitative analysis of the vessel length density and branch point density of 87 main anatomical clusters in ABA (n = 4 samples). Illustration of the mapped somata distributions/vasculatures are displayed in accordance with Allen CCF border lines and region-based color-coding. All values are presented as the mean ± SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

SOLID enables whole-brain profiling of retrograde and antegrade neural projections from specific brain regions

Precise profiling of long-range neural connections within specific brain regions is important for understanding the function of the brain. Here, we used SOLID to investigate specific neural circuits labeled with viruses. We compared the overall performance of SOLID with FDISCO, a well-established method capable of imaging virus-labeled brains12. The retro adeno-associated virus (AAV-retro) was injected into the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the left hemisphere of mice for retrograde tracing of neural projections onto VTA. Subsequently, the mouse brain was counterstained with nucleic acid dye and cleared using SOLID or FDISCO. Although both SOLID and FDISCO successfully enabled the visualization of labeled neural circuits throughout the mouse brain (Supplementary Fig. 14A, B), the imaging contrast was better in mouse brains cleared using SOLID (Supplementary Fig. 14C, D). In particular, brain datasets acquired from SOLID-cleared brains revealed more precise localization of neural projections owing to the high quality of image registration (Supplementary Fig. 14E). This unique advantage may allow the application of SOLID to brain-wide profiling of specific neural projections with relatively high accuracy.

Furthermore, we examined whether SOLID could be used for simultaneous visualization and identification of retrograde and antegrade neuronal projections from specific regions across the brain. We injected AAV-retro and AAV-mCherry into the pontine nuclei (PN) region for retrograde and antegrade tracing of neural projections, stained the extracted brains with nucleic acid dye and obtained whole-brain datasets containing information for both neural projections and cell distribution (Fig. 5A–C). Multi-color rendering facilitated the assessment of neural projections within the same brain (Fig. 5D, E; Supplementary Movie 4). Subsequently, the acquired brain datasets were registered to ABA using the MIRACL pipeline (Fig. 5F, G), and 3D retrograde and antegrade neural projection maps were simultaneously created based on the anatomical annotations with reference to ABA (Fig. 5H, I; Supplementary Movie 4). The brain regions through which the neural projections passed were identified, and the corresponding projection intensities were evaluated (Fig. 5J, K). The results revealed a diverse and widely distributed set of afferent projections to PN, which heavily projected from sub-regions such as CP, PAL, LZ, MEZ, and a large number of sub-brain regions belonging to Iso, HB, CB and fiber tracts (Fig. 5J). On the contrary, the output from PN was relatively limited, which were mainly concentrated in brain regions such as Iso, TH, MB, HB and CB (Fig. 5K). These results were consistent with those of previous studies investigating neural projections to PN based on tissue slices42,43,44.

A 3D reconstruction of AAV-retro-labeled afferent projections (green) to pontine nuclei (PN) throughout the brain. B 3D reconstruction of AAV-labeled antegrade projections (magenta) from PN. C The counterstained cell nuclei channel (cyan). D Reconstruction of the merged channel images from (A–C) (from 2 replicates). E Sagittal view of the 3D reconstruction shown in (D). F Registered brain section images for the retrograde projection channel. G Registered brain section images for the antegrade projection channel. H Horizontal and sagittal views of the brain-wide neural projections to PN with standard anatomical annotations. I Horizontal and sagittal views of the brain-wide neural projections from PN with standard anatomical annotations. J Quantification of the relative intensity of retrograde projections to PN in different brain regions. K Quantification of the relative intensity of antegrade projections from PN in different brain regions. Illustration of the mapped neural projections are displayed in accordance with Allen CCF border lines and region-based color-coding. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

SOLID realizes cross-channel profiling of brain-wide pathological changes for neuronal somata, vasculature and Aβ plaques during the progression of AD

AD is a serious neurodegenerative disorder primarily characterized by the deposition of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques. Existing treatment methods for AD are ineffective, necessitating the development of novel, more effective methods45. Given that Aβ plaques have a substantial influence on their neighboring structures, such as neurons and blood vessels, it is important to investigate both brain-wide deposition of Aβ plaques and alterations in other structures during the progression of AD. Therefore, we generated 5xFAD/YFP mice by crossing 5xFAD mice with Thy1-YFP-H mice, sparsely illuminating the neurons with YFP signals in 5xFAD mice. The entire vasculature was labeled with gelatin-based fluorescent dye, whereas Aβ plaques were labeled with DANIR-8c fluorescent probe as reported previously46 (Supplementary Fig. 15A). Subsequently, SOLID was combined with multiple fluorescent labeling techniques, light-sheet imaging and an image analysis pipeline to obtain 3D reconstructed images of multiple structures, including neurons, blood vessels and Aβ plaques, within the same brain (Fig. 6A, B; Supplementary Movie 5). The YFP channel was used as a reference to ensure registration of images to ABA, and the alignment results were applied to two other channels (Fig. 6C, Supplementary Fig. 15B). The labeling efficiency and segmentation accuracy of Aβ plaques were validated (Supplementary Fig. 15C, D). After proper segmentation and anatomical annotation, the structural information of Aβ plaques and blood vessels in each brain region was clearly identified (Fig. 6D). A magnified region belonging to FRP was selected to visualize the characteristics of Aβ plaques and blood vessels in wild-type (normal), 3-month-old (3 M) and 8-month-old (8 M) 5xFAD/YFP mice. Unlike the normal vascular morphology, the vessels within the brains of AD mice exhibited a tortuous shape with a spotted, string-like formation (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, we performed whole-brain profiling for numerous anatomical sub-regions in 3 M and 8 M 5xFAD/YFP mice to analyze the regional progression of AD (Supplementary Movie 6). The Aβ plaque density and the vessel density were calculated in a majority of brain regions for both 3 M and 8 M AD mice (Fig. 6F, left and middle). On calculating the fold increase/decrease rate of Aβ plaque density/vessel length density for each region, we found that a majority of brain regions with evidently increased Aβ plaque deposition had considerably low vessel density (Fig. 6F, right). Additionally, the summary of Aβ plaque density and vessel length density in 11 major brain regions in 3 M and 8 M AD mice could also be calculated (Supplementary Fig. 15E, F). Notably, we also quantified the number and density of Aβ plaques deposited on blood vessels within 11 main brain regions in mice with AD (Fig. 6G).

A Three-channel rendering of neurons (green), blood vessels (glow) and Aβ plaques (blue) (from >3 replicates). B Magnification of the boxed region in (A). C Registration of the multi-color brain datasets to ABA. D 3D rendering of the segmented data blocks for indicated brain regions. E Representative 3D rendering for Aβ plaque and blood vessel data blocks within the FRP region in normal, 3 M and 8 M AD mice. F Quantitative analysis of Aβ plaque density and vessel length density in 83 sub-regions in 3 M and 8 M AD mice. To calculate fold-changes for Aβ plaque density and decrease rate for vessel length density, mean values of calculated data for each age are used (n = 5 samples for AD 3 M, n = 7 samples for AD 8 M). G Quantitative analysis of total number and density of vessel-related Aβ plaques in 11 major brain regions in 3 M and 8 M AD mice (n = 5 samples for AD 3 M, n = 7 samples for AD 8 M). H Representative 3D rendering for the identified Aβ plaques, neuronal somata and neuronal somata invaded by Aβ plaques within the SSs region in 3 M and 8 M AD mice. Different colors represent different layers of the cortex. I Quantification of the Aβ plaque/neuronal somata overlap ratio in different layers of the cerebral cortex in 3 M and 8 M AD mice. To calculate the overlap ratio, mean values of Aβ plaque/neuronal somata for each group are used. (n = 5 samples for AD 3 M, n = 7 samples for AD 8 M). All values are presented as the mean ± SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Regional analysis was also performed to examine pathological changes in neurons and Aβ plaques in the cerebral cortex (Supplementary Movie 6). Layer 1 of each cortical area was excluded because the quantification of cells/plaques in this outermost area is easily influenced by the tissue background or potential tissue damage during dissection. Representative volume rendering for the SSs region demonstrated a significant increase in the number of neurons invaded by Aβ plaques in 3 M 5xFAD/YFP mice when compared with that in 8 M 5xFAD/YFP mice, indicating that Aβ plaques continuously accumulated in the neuronal somata during the progression of AD (Fig. 6H). Additionally, whole-cortex profiling was performed to generate an unbiased heat map reflecting the overall neural lesions in different layers of different cortical regions (Fig. 6I). Although numerous studies have reported the visualization and quantification of neurons, Aβ plaques or blood vessels, most of these studies have focused on only one of these typical structures. Therefore, this study pioneered simultaneous visualization and cross-channel quantification of brain-wide, multiple structural changes in mice with AD. The findings of this study may provide valuable insights into the pathological mechanisms underlying the development of AD.

Discussion

Brain-wide profiling of diverse biological components and the interaction among them are important to understanding the complex brain functions. Despite the availability of multiple tissue clearing techniques for whole-brain imaging, limitations such as tissue distortion, insufficient transparency or complex execution pipelines restrict the use of these techniques in whole-brain mapping. Here, we propose SOLID based on a synchronous delipidation/dehydration strategy mediated by 1,2-HxD. SOLID simultaneously realize in high transparency, minimal size change and robust fluorescence preservation, which are critical for multi-color, 3D imaging of diverse tissues, such as whole brains and neonatal mouse bodies, at cellular resolution. Notably, the brain datasets for SOLID can be registered to the ABA using various registration methods. Therefore, SOLID is highly useful for conducting global analysis of diverse biological components, such as cell distribution, neural projections, vascular topology and remodeling, and plaque accumulation.

In addition to high tissue transparency and good fluorescence preservation, which can be achieved by a series of methods, the ideal conditions for tissue clearing often involve the maintenance of sample size close to the initial morphology. Tissue shrinkage is mainly caused by complete dehydration during solvent-based clearing47. We hypothesise that transient tissue expansion at the beginning of dehydration might reduce tissue shrinkage, and identify an aliphatic diol named 1,2-HxD. 1,2-HxD possesses strong delipidation ability at low concentrations and effective dehydration ability at high concentrations. As expected, tissue shrinkage can be significantly reduced by transient tissue expansion caused by 1,2-HxD at low concentrations. In addition, effective delipidation during dehydration aids in enhancing tissue permeability, thereby facilitating deep tissue labeling. After fine-tuning of each step, the designed SOLID protocol realizes efficient clearing of diverse biological specimens, including isolated tissues/organs as well as neonatal and adult mouse bodies, resulting in high tissue transparency and minimal tissue distortion only through passive immersion. Additionally, SOLID is also proved to be compatible with a variety of fluorescent signals tested. In our tests, tissue clearing methods involving urea, such as EZClear and F-CUBIC, tend to attenuate DAPI signals, similar with previously reported48. Aqueous-based methods, including SHIELD, EZClear and F-CUBIC, are friendly to endogenous fluorescent signals. All tested methods are compatible with indicated immunofluorescence. The performance of SOLID in preserving fluorescence should be continuously validated by different researchers on different kinds of probes in the future.

It should be noted that SOLID is not the first method that aims to reduce tissue distortion and preserve tissue structures if locating in the entire tissue clearing field. A large proportion of aqueous-based clearing method, such as SHIELD24, EZClear27, OPTIClear25, Accu-OptiClearing26, F-CUBIC21 and MACS29, have made great contributions in reducing tissue distortion. However, good preservation of tissue morphology alone is not enough to ensure reliable whole-brain registration analysis, sufficient tissue transparency and fluorescence compatibility are also crucial to ensure the quality of whole brain images. It is excited to see that novel aqueous-based clearing method are continuously emerging with improved tissue transparency in the past years (e.g., SHIELD, EZClear and F-CUBIC). Additionally, the combination of different kinds of tissue clearing strategy begins to emerge. In a pioneering study, different categories of tissue clearing methods are combined to develop HYBRiD, which enabled whole-body clearing and imaging49. However, this simple and rigid combination strategy introduces problems such as superabundant processing steps and long processing times, leading to potential tissue destruction and a low success rate of repetition. As for SOLID, both solvent-based and aqueous-based strategies are utilized only with a graded series of 1,2-HxD-based mixtures, which is easier and more effective. We believe that SOLID may guide the combination of solvent- and aqueous-based clearing methods to innovate more effective clearing strategies in the future.

In recent years, serial two-photon tomography provides brain-wide imaging datasets with exceptional resolution and less tissue deformation, which facilitates relatively straightforward alignment with ABA and indeed become a benchmark for precise neuroanatomical mapping. As an emerging technology, tissue clearing has greatly lowered the threshold for whole-brain imaging, however, the remaining drawbacks prevent further registration and profiling of acquired brain datasets. For example, tissue shrinkage resulting from solvent-based methods can benefit the imaging of large tissues, such as whole mouse body8,13,16, whereas, tissue shrinkage may prevent automated image registration to a common reference brain atlas10. For aqueous-based clearing methods, though the sample size can be preserved, the relative low transparency degrades the image quality, especially in the deep region. Recently, efforts have been made to improve the registration accuracy through different means. For instance, tissue shrinkage is treated by measuring the shrinkage rate via MRI, which improves the registration accuracy for further whole-brain vasculature analysis31. However, the requirements for customised instruments33, specialized codes or complex deep-learning frameworks31,32 potentially limits their application. SOLID directly improves the abovementioned limitations in the tissue clearing procedure, thereby not only enables high-quality imaging of the whole mouse brain at cellular resolution, but also allows for direct registration of acquired datasets to ABA using a series of readily available algorithms. While we recognize that the current state of the art in tissue clearing may not yet match the precision of two-photon imaging for brain registration, we believe that the progress made is noteworthy and warrants further investigation, and SOLID may enhance the utility of tissue clearing techniques from whole-brain imaging to whole-brain profiling.

In addition to the registration accuracy, the reliable identification and segmentation of diverse structures are also important for further analysis. Though the quantifications are performed using well-established software, we recognize the essential role of validation in establishing the credibility and reliability of our results. For example, though the cell identification and regional segmentation were performed using well-designed MIRACL and BIRDS-Imaris pipelines38,39, and the results can be found consistency with published results41, the reproducibility of our estimates should be further validated by different hands. VesselExpress40, a recently-developed toolbox for fine profiling of diverse vascular structures in tissue-clearing-based datasets, is used to analyse brain vasculature in this study. Although there are ready-to-use parameters in original publication, we conduct an additional parameter configuration for SOLID to ensure the optimal parameter is used. The quantitative results regarding vascular features are compared side-by-side with those data reported in previous studies, including vessel length density, branch point density and vessel tortuosity, and are found to possess a high level of consistency with results from literature, not only in typical main brain regions40, but also in a series of secondary brain regions34. We also find the mean value and standard deviation of branch diameter obtained in this study was slightly higher than results from ref. 40, presumably because both large and small blood vessels within the entire region are taken into account.

Furthermore, SOLID is found to be effective in investigating the topological remodeling of multiple structures in mice with AD. Previous studies have conducted brain-wide imaging and analysis of Aβ plaques, neurons or blood vessels, individually46,50,51. However, few studies have examined the complex influence of Aβ plaques and other structures in a single sample simultaneously, which may help understand the complex pathological progression of AD. In this study, we label neurons, blood vessels and Aβ plaques in the same brain, and successfully perform brain-wide mapping of diverse structural interactions at different stages of AD. SOLID facilitates the identification of a previously unobserved negative correlation between Aβ plaque formation and vessel density, representing a powerful tool for elucidating the pathological mechanisms underlying the development of neurodegenerative disorders.

To ensure the observed negative correlation is not a methodological artifact, we carefully verify the accuracy of Aβ plaques labeling compared to traditional antibodies, as well as ensure precise image registration based on neural information channel. Further examinations can be extended to other mouse models of AD or even human clinical samples to guarantee the scientific rigor. Notably, it is also important to identify potential mechanisms that explain the negative correlation in the future. For example, though we identify the decrease of vessel length density, it is difficult to judge whether there is permanent capillary loss or just microvascular blockage during the accumulation of Aβ plaques based on current imaging results. It has been shown in previous studies that deposition of Aβ plaques will cause widespread capillary compression, leading to potential vessel loss and reductions in blood flow52. Additionally, the abnormal increase of neutrophils led by neuro-inflammation during the progression of AD might also block the capillary flow53. Further gaining insight into the potential inducement that leads to the decrease of vessel density is crucial for the advancement of immunotherapeutic strategies against AD.

Whole-mount immunolabeling with tissue clearing has been continuously conducted in diverse biomedical research. Inspired by the better performance of SOLID-DL in enhancing antibody penetration, we are excited about the prospects of applying SOLID-based 3D immunolabeling techniques in diverse brain mapping applications under the context of neuroscience. However, we also recognize that, at current stage, the antibody penetration efficiency enabled by passive-diffusion-based SOLID-DL is still a bit insufficient to meet the demand for fast brain mapping. For example, it may still require rather long time (more than 3 weeks) to label specific antigens with high density (e.g., Aβ plaques) using traditional antibodies in the intact brain, therefore, using validated fluorescent probes to label Aβ plaques seems to be a better alternative at this stage. However, given the indispensable role of antibodies in diverse biomedical research, further efforts should be made to promote antibody penetration for labeling large mammalian brains and even human clinical tissues. Recently, the latest wildDISCO technology is designed as an active pumping immunolabeling pipeline to facilitate antibody penetration through transcardial perfusion, and show impressive imaging results for whole mouse body16. However, perfusion-based immunolabeling requires much more antibody, which is more expensive than passive labeling and might not be feasible for many researchers. Therefore, we are currently in the process of improving the SOLID-DL by optimizing diverse physical and chemical conditions for antibody penetration, trying to realize ultrafast antibody penetration in the future. We believe the continuously-evolved SOLID technology would significantly benefit the neuroscience community for diverse brain mapping applications at that time.

It is worth saying that there are already commercial tissue clearing systems available, such as X-CLARITY and SmartClear II Pro, with indeed impressive publicity for high performance tissue clearing. Such instruments do provide new choices for researchers who want to use tissue clearing in their own study but lack of relevant expertise. However, several potential limitations may reduce researcher’s enthusiasm in such instruments, such as the unaffordable price and high use-cost. Additionally, given that current tissue clearing instruments are built upon clearing methods based on hydrogel-embedding, it is really hard to fulfill all of the demands with just one kind tissue clearing strategy. Therefore, the tissue clearing methods are still continuously evolving to meet different experimental desires in life science research16,54, and we hope there will be new instruments in the future to fit on other kinds of tissue clearing methods.

In recent years, whole-brain mapping projects have collected 3D structural and functional datasets using not only optical imaging tomography but also other modalities, such as PET and MRI. To utilize these datasets for a comprehensive assessment of the structure and function of the brain, novel methods have been proposed for the cross-modal registration of different brain datasets55. Given that SOLID is compatible with various registration methods, it may be combined with novel cross-modal registration pipelines to perform whole brain profiling across different modalities.

Methods

Animals

Wild-type mice (C57BL/6 J; male; age, 8–12 weeks) and transgenic mice (Thy1-GFP-M [male; age, 8–10 weeks]; Thy1-YFP-H [male; age, 8–10 weeks]); 5xFAD/YFP [female; age, 12 and 56 weeks] were used in this study. The Thy1-GFP-M/Thy1-YFP-H transgenic mice specifically express GFP/YFP in a proportion of pyramidal neurons within entire brain. All mice were housed in a specific-pathogen-free (SPF) environment under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle with unrestricted access to food and water. Adult pig brains were purchased from a local slaughterhouse. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Experimental Animal Management Ordinance of Hubei Province, P. R. China and the guidelines established by the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Virus injection

We used rAAV-hSyn-EGFP-WPRE-hGH-pA; AAV2/RETRO (BrainVTA, PT-1990), rAAV-CAG-DIO-mCherry-WPREs (BrainVTA, PT-1529) and rAAV-hSyn-Cre-WPRE-hGH-pA (BrainVTA, PT-0136) for neural tracing. C57BL/6 J mice aged 8–9 weeks were anaesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (100 and 20 mg/kg, respectively) and placed in a stereotaxic frame (RWD Life Science, China). A cranial window was created on the skull to expose the target brain region. The abovementioned viruses were injected using a custom-established injector fixed with a pulled glass pipette. The injection site was determined by referring to a mouse brain atlas. AAV-retro (300 nL) was targeted to the VTA with the following coordinates: The injection site (VTA: bregma, −3.52 mm; lateral, 0.5 mm; ventral, 4.23 mm); AAV-retro (300 nL) and the AAV-mCherry were targeted to the PN with the following coordinates: The injection site (PN: bregma, −3.88 mm; lateral, −0.5 mm; ventral, −5.2 mm). After the glass pipette was vertically inserted into the target site through the cranial window in the skull, a micro-syringe pump was used to deliver (injection speed, 0.2 μL/min) the virus with an injection volume of 200 nL/point. After the injection was completed, the glass pipette was left in place for 5–8 min and the syringe needle were withdrawn slowly. Meloxicam (4 mg/kg) was subcutaneously injected once daily for 3 d to relieve postoperative pain. All mice were placed in a warm cage after injection and transferred to a regular animal room after they gained consciousness. The mice were housed for 28 d after AAV injection before perfusion.

Vascular labeling

We used a vessel casting protocol based on a gelatin-WGA hydrogel, similar with those previously reported56,57. First, pig skin gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich, V900863) was dissolved in distilled water to prepare a 2% (w/v) solution, a water bath at 45 °C would ensure complete dissolution of gelatin powder. Subsequently, 0.1-mg WGA-555/WGA-633 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, W32464, W21404) was added to 15 mL of the gelatin solution to obtain the vessel casting solution. The solution should be kept away from light and continuously heated in a water bath at 40 °C to preserve its liquid state before use. Mice were anaesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (100 and 20 mg/kg, respectively) and transcardially perfused with 0.01-M PBS at first to remove the blood. Thereafter, the mice were perfused with the vessel casting solution under warm conditions (10-15 mL for adult mice; 1–1.5 mL for newborn mice). After vessel casting, the mice were kept at 4 °C overnight to solidify the dye hydrogels. Then the desired organs were harvested from the mouse body and post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight.

Deep labeling using SOLID-DL

Cell nuclei labeling

TO-PRO-3 dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific, T3605) and Propidium Iodide (PI, Aladdin, P266304) were used for nucleic labeling. PI stock solution was prepared by dissolving the dye powders in DMSO at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. The labeling solution was prepared by diluting TO-PRO-3 dye / PI stock solution with 0.01-M PBS containing sodium azide (0.02%) and 0.5-M NaCl at a ratio of 1:1000/1:200. The samples were pretreated with SOLID-permeabilization solution containing 15% (v/v) 1,2-HxD and 10% (v/v) N-butyldiethanolamine for 2 d with gentle shaking at 37 °C and washed in PBS overnight. Subsequently, the samples were incubated with the prepared dye solution with gentle shaking at 37 °C for 2–5 d based on the tissue size. The labeled samples were washed in 0.01-M PBS for 12 h, with PBS being replaced every 3 h.

Aβ labeling

DANIR-8c fluorescent probe (Beijing Shihong Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., No. 072701) was used to label Aβ plaques. The dye was prepared by dissolving DANIR-8c fluorescent crystals in a pre-prepared solution (0.01-M PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100, 0-30% [w/v] sucrose and 0.05% sodium azide) at a concentration of 1 μmol/L. The mouse brains were pretreated with SOLID-permeabilization solution containing 15% (v/v) 1,2-HxD and 10% (v/v) N-butyldiethanolamine for 2 d with gentle shaking at 37 °C and washed in 0.01-M PBS overnight. The following day, the whole mouse brains were sequentially immersed in the prepared dye solutions containing 15% sucrose, 30% sucrose and 0% sucrose with gentle shaking at 37 °C in the dark. The processing time for each step was 1 d, 2 d and 1 d, respectively. After labeling, the samples were washed in 70% alcohol for 12 h, followed by an overnight wash in PBS. The effectiveness for labeling Aβ plaque using DANIR-8c was validated in mouse brain slices using β-amyloid (D54D2) XP antibodies (Cell Signaling, 51374). For labeling 1-mm-thick mouse brain sections, the pretreatment step could be skipped and the processing time could be shortened.

Immunolabeling

The following antibodies were used in this study. Primary antibodies: β-amyloid (D54D2) XP antibodies (Cell Signaling, Cat# 51374, dilution 1:500), anti-GFP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# A-11122, dilution 1:500); anti-Iba1 (Proteintech, Cat# CL647-81728, dilution 1:200); anti-Tyrosine Hydroxylase (abcam,Cat#ab112, dilution 1:500); anti-beta Tubulin (abcam, Cat# ab21057, dilution 1:500); anti-LYVE1 (abcam, Cat#ab218535, dilution 1:500); anti-PGP9.5 (proteintech,Cat#14730-1-AP, dilution 1:500);Anti-α-SMA (Boster, Cat# BM0002,dilution 1:500);Anti-ChAT (Synaptic system,Cat# 297015,dilution 1:500); Anti-cTNT (R&D system, Cat#MAB1874, dilution 1:500); anti-MAP2 (Proteintech, Cat# 17490-1-AP, dilution 1:500); anti-NeuN (Proteintech, Cat# 26975-1-AP, dilution 1:500); anti-GFAP (Proteintech, Cat# 16825-1-AP, dilution 1:500); Secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# A-11037, dilution 1:500); Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# A-21070, dilution 1:500); Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-Guinea Pig IgG (H + L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# A-21435, dilution 1:500); CoraLite488-conjugated goat anti-Rabbit IgG(H + L) (Proteintech, Cat# SA00013-2, dilution 1:500); CoraLite594 conjugated goat anti-Rabbit IgG(H + L)(Proteintech, Cat# SA00013-4, dilution 1:500).

Mouse brain tissue samples were first pre-treated with SOLID-permeabilization for 2–5 d. Then the brain samples were incubated sequentially in 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%, 80%, 60%, 40% and 20% methanol solutions for 1–3 h (each solution). The pre-treated samples were incubated with 0.2% PBST containing 20% DMSO, 2% 1,2-HxD and 0.3 M glycine (50046, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C overnight. After washing, the samples were blocked with 0.2% PBST containing 10% DMSO and 6% goat serum at 37 °C for 1 d, washed in 0.2% PBST overnight and incubated with primary antibody solution diluted in 0.2% PBST containing 3% goat serum and 0.01% (w/v) sodium azide with gentle shaking at 37 °C for 1-20 d (depending on antigen type and sample size). Subsequently, the samples were washed in 0.2% PBST for 1 d and incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in 0.2% PBST containing 2% 1,2-HxD (optional), 3% DMSO, 3% goat serum and 0.01% (w/v) sodium azide with gentle shaking at 37 °C for 1-20 d (depending on antigen type and sample size). The samples were finally washed in 0.2% PBST for 1 d and stored in PBS at 4 °C before subsequent clearing. For CUBIC-HV58, the samples were first delipidated in CUBIC-L solution for 3 d. After washing, the delipidated samples were 3D stained with a dye-conjugated primary antibody in HEPES-TSC buffer [10 mM HEPES buffer, containing 10% (v/v) Triton X-100, 200 mM NaCl, and 0.5% (w/v) casein] at 37 °C. The stained samples were then washed with 0.2% PBST and 0.01 M PBS, and used for RI matching with CUBIC-R. For iDISCO+10, brain samples were first treated sequentially in 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%, 100% for 1 h per step and incubated in 100% methanol overnight. The samples were then delipidated with 66% dichloromethane/33% methanol overnight and bleached with 5% H2O2. After that, the samples were rehydrated in 80%, 60%, 40%, 20% methanol and PBS for 1 h each. The samples were then incubated in PBS/0.2% Triton X-100/20% DMSO/0.3 M glycine at 37 °C overnight, blocked in PBS/0.2% Triton X-100/10% DMSO/6% goat serum at 37 °C for 1 d, and finally incubated with a dye-conjugated primary antibody dilutions in PTwH/5% DMSO/3% goat serum at 37 °C.

Brain section labeling for evaluation of fluorescence compatibility

To evaluate the fluorescence compatibility of different tissue clearing methods, 1-mm-thick mouse brain sections were employed. All labeling were performed prior to tissue clearing. Specifically, for nuclei labeling, 1-mm-thick C57BL/6 J mouse brain slices were incubated with DAPI (2 mg/mL in PBS)/TO-PRO-3 (1 μM in PBS) solution for 1 d at room temperature with gentle shaking and then washed with PBS. GFP/YFP signals were from 1-mm-thick Thy1-GFP-M/ Thy1-YFP-H mouse brain slices. WGA-AF555/DANIR-8c were labeled as described above. For antibody labeling, 1-mm-thick C57BL/6 J mouse brain slices were first blocked in 0.2% PBST containing 6% goat serum at 37 °C for 3–6 h and then subjected to the primary antibodies diluted in 1–2 mL 0.2% PBST containing 3% goat serum albumin and 0.01% (w/v) sodium azide for 1 d at 37 °C with rotation, then the samples were washed with 10 mL 0.2% PBST several times and immersed in secondary antibodies diluted in 1–2 mL 0.2% PBST containing 3% goat serum albumin and 0.01% (w/v) sodium azide overnight at room temperature with rotation. The samples were then washed with 10 mL 0.2% PBST several times and stored in 0.01 M PBS at 4 °C prior to clearing.

Tissue clearing with SOLID

SOLID clearing protocol mainly consists of two parts, namely gradient delipidation/dehydration and RI matching. Procedure for gradient delipidation/ dehydration contains four solutions, including gradient concentration of 30%, 50%, 70% and 90% (v/v) of 1,2-HxD (Macklin, H916855) with 2% (v/v) N-butyldiethanolamine (Tokyo Chemical Industry, B0725) added. The HxD-TBN solution for thorough dehydration was prepared by 90% (v/v) 1,2-HxD/ 10% (v/v) tert-butanol, then added 2% (v/v) N-butyldiethanolamine and dH2O, respectively. The RI matching solution BBPN was composed of 75% (v/v) benzyl benzoate, 20% (v/v) polyethylene glycol methacrylate 500 (PEGMMA500, Sigma, 447943) and 5% (v/v) N-butyldiethanolamine. The entire clearing operation should be carried out with gentle shaking at 30 °C. The time needed for each step depends on sample size. For example, it may need 1 d, 0.5 d, 0.5 d, 0.5 d, 1d for large samples, such as a whole mouse brain. Then the samples were immersed in the RI matching solution until becoming fully transparent.

Tissue clearing with other methods

FDISCO12: Briefly, fixed tissues were sequentially dehydrated in 50%, 70%, 80%, 100%, 100% (v/v) tetrahydrofuran (THF, Sigma, 360538) solutions. The dehydrated tissues were incubated with pure dibenzyl ether (DBE, Sigma, 186562) for refractive index matching. For FDISCO, triethylamine was added to THF solutions to adjust the pH to 9. All steps were performed at 4 °C with gentle shaking.

uDISCO8: Briefly, fixed tissues were sequentially dehydrated in 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 96% and 100% (v/v) tert-butanol (Sigma, 360538) solutions. The samples were matched with the BABB-D4 solution. This solution was prepared by mixing benzyl alcohol (Sigma, W213705) with benzyl benzoate (Sigma, W213802) in a ratio of 1:2. This BABB solution was subsequently mixed with diphenyl ether (DPE, Sigma, W366706) in a ratio of 4:1, followed by the addition of 0.4% (v/v) DL-α-tocopherol (vitamin E). All steps were performed at 35 °C with gentle shaking.

PEGASOS11: The samples were decolorized with 25% (v/v) (N,N,N’,N’-tetraethylenediamine [2-hydroxypropyl]) (Quadrol, Tokyo Chemical Industry, T0781) for 2 d. The decolorized samples were sequentially incubated with 30%, 50% and 70% (v/v) tert-butanol mixed with 3% (w/v) Quadrol for 12 h each. The samples were incubated with TB-PEG containing 70% (v/v) tert-butanol, 27% (v/v) PEGMMA500 and 3% (w/v) Quadrol for 2 d. Finally, the samples were matched with BB-PEG containing 75% (v/v) benzyl benzoate, 25% (v/v) PEGMMA500 and 3% (w/v) Quadrol until they became transparent. All steps were performed at 37 °C with gentle shaking.

iDISCO+10: The samples were sequentially pre-treated with 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%, 80%, 60%, 40% and 20% (v/v) methanol (Sigma, 179337) solutions for 1 h each and washed in PBST for 1 h. The pre-treated samples were incubated with 0.2% PBST containing 20% DMSO and 0.3-M glycine at 37 °C overnight. The following day, the samples were sequentially incubated with 20%, 40%, 60% and 80% methanol solutions, followed by immersion in a pure methanol solution containing 66% dichloromethane overnight. Subsequently, the samples were washed twice with a pure methylene chloride solution and incubated with DBE until they became transparent.

CUBIC20: CUBIC-L was prepared by mixing 10 wt% N-butyldiethanolamine with 10 wt% Triton X-100 (Sigma, X100) in dH2O. CUBIC-R was prepared by mixing 45 wt% antipyrine (Tokyo Chemical Industry, D1876) with 30 wt% nicotinamide (Tokyo Chemical Industry, N0078) in dH2O. Tissue samples were incubated with CUBIC-L for 4–7 d for delipidation, washed in PBS for 12 h and incubated with CUBIC-R for 2–4 d for RI matching. All steps were performed at 37 °C with gentle shaking.

EZClear27: Fixed samples were incubated with 20 mL of the following solutions in sequence: (1) 50% (v/v) THF (Sigma, 186562) prepared in dH2O for 16 h to remove lipids. (2) Wash the samples with sterile dH2O four times, 1 h each at room temperature. (3) RI matching: incubate the samples with 5 mL of EZ View solution for 24 h to render the samples transparent for imaging. The EZ View solution consisted of 80% Nycodenz, 7 M urea, 0.05% sodium azide prepared in 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer.

F-CUBIC21: The F-CUBIC solution consisted of 10 wt% formamide (Sigma, F7503) and ScaleCUBIC-1 [25 wt% urea, 25 wt% Quadrol, and 15 wt% Triton X-100]. For optical clearing, the fixed tissues were directly immersed in F-CUBIC with gentle shaking at room temperature. For whole mouse brain, the clearing time was extended to a week or longer, with the clearing reagent refreshed every 2–3 d.

SHIELD24: The SHIELD solutions were purchased from LifeCanvas Technologies and prepared according to the user guide. Generally, mice were first perfused with SHIELD-PERFUSION solution followed by sample collection. Then the harvested samples were incubated in SHIELD-OFF solution at 4 °C for 2 d. The samples were then transferred to SHIELD-ON buffer and incubated at 37 °C with shaking overnight. Then, the samples were transferred to SDS buffer at 37 °C for 14 d. After clearing was completed, the samples were washed with PBST (1% Triton X-100 in PBS) overnight. Finally, the tissue was incubated in EasyIndex (LifeCanvas Technologies) with shaking at room temperature until transparent.

Imaging

Bright-field images were captured using a digital camera. Cleared brains and other tissue samples were imaged using a light-sheet microscope (LiToneXL, Light Innovation Technology, China) equipped with a 4× objective lens (NA = 0.28; working distance WD, 20 mm) and 10× objective lens (NA = 0.5; WD, 5 mm). Thin light sheets were used to illuminate the samples from all four sides, and a merged image was saved. Tissue slices were imaged using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM710, Zeiss, Germany) equipped with a 5× objective lens (NA = 0.25, WD, 12.5 mm), a 10× objective lens (NA = 0.5, WD, 2 mm), a 20× objective lens (NA = 0.8, WD, 0.55 mm) and a 40× objective lens (NA = 1.4, WD, 0.13 mm). The Zen 2011 SP2 software (Version 8.0.0.273; Carl Zeiss GmbH, Germany) was used to collect data.

Customized micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) was used to visualize 3D changes in the size of the whole mouse brain after clearing. The whole mouse brains were imaged using micro-CT before and after clearing with different methods, followed by 3D reconstruction of the images using the Imaris software (Version 7.6, Bitplane AG).

Image registration and dice score computation

Image stacks were down-sampled using linear interpolation to reduce the data size. The Allen CCFv3 Brain Atlas with an isotropic voxel size of 25 μm was downloaded from the Allen website. The whole brain datasets were registered using four well-established image registration pipelines, including aMAP (version 1.0.3)37, ClearMap (version 2.0)10, MIRACL (version 2.2.6)38 and BIRDS (version 1.0)39. The source code or software was downloaded for each pipeline, and the datasets were registered according to the original above cited publications.

The Dice score is an important indicator for quantifying the accuracy of registration and can be calculated as follows:

In the abovementioned Eq. (1), A represents the ground truth of a specified brain region, B represents the result of the registered brain map generated using each method, A ∩ B represents the number of pixels in which A and B overlap and A + B represents the total number of pixels in A and B. We selected typical brain regions to assess the accuracy of different clearing methods, with reference to operations reported in previous studies39. To make the comparison as objective as possible, three skilled individuals independently repeated the abovementioned process 5 times, and the integrated results represented ground-truth segmentation for each region.

Image segmentation and feature extraction

Cell detection and counting

We detected and counted neuronal somata using the BIRDS–Imaris pipeline. Briefly, multi-color brain datasets were registered to ABA based on the cell nucleic channel using the BIRDS pipeline and segmented into individual brain regions based on the registration results. Subsequently, the brain regions were categorized into multiple channels using Imaris automatic creation function, and the Spots module was used to detect and count the cells in each channel. The quality parameters were modified based on the appropriate diameter of cell bodies. After the automatic detection of the neuronal somata in each brain region, the data were manually corrected to ensure accuracy. Subsequently, the total number of detected cells in each brain region and the volume of each brain region were calculated. In addition, a 3D neural map was generated by automatically annotating datasets containing the detected cells to anatomical regions with reference to ABA. Finally, cell density was evaluated based on the total number of cells in each brain region and the volume of each brain region.

VesselExpress parameter configuration

We used a recently developed toolbox for vascular quantification, termed VesselExpress (version 1.1.1)40, enabling rapid and automated vasculature analysis for light-sheet imaging datasets. Though VesselExpress-napari provides default parameters for different organs to use, it is necessary for fine tuning of these parameters to ensure validity (Supplementary Fig. 10A). First, we used the default parameters to process the SOLID brain data (Supplementary Fig. 10B). The vessel segmentation results are not very accurate with overly-thick vessel diameters and overly connected to the surrounding vessels (Supplementary Fig. 10C, left). We then started to adjust the parameters step by step under the guidance of the original literature. We adjust the “sigma” of the second Frangi filter from “1” to “2” based on the noise level of our data, and change the “Cut-off method_2” from “Li” to“OTSU” to avoid thickening of extract vessels. To avoid excessive vessel connections, we adjust the “post_closing” parameter from “5” to “3”. The final extraction results using adjusted parameters were nearer to original data compared to the results achieved by default parameters (Supplementary Fig. 10C).

Vessel segmentation and feature extraction

Vessel segmentation and feature extraction were automatically achieved by uploading the vascular imaging data of each region to VesselExpress. Subsequently, a 3D vascular map was generated by automatically annotating datasets containing the segmented vessels to anatomical regions with reference to ABA. We calculated four characteristic vascular parameters (average vessel tortuosity, average branch diameter, vessel length density and branch point density) in diverse brain regions with the browser version of VesselExpress as reported in the original study.

Extraction and quantification of neural projections

Multi-color brain datasets were registered to ABA based on the cell nucleic channel using the MIRACL pipeline and segmented into individual brain regions based on the registration results. To extract information regarding neural projections, the imaging data of brain regions were segmented semi-automatically using the Imaris software. Subsequently, datasets containing the segmented neural projection data of each brain region were anatomically annotated with reference to ABA. For quantification, we considered the fluorescence value of all brain regions as 100% and calculated the percentage of fluorescence signals in each brain region as the relative projection intensity.

Segmentation and quantification of Aβ plaques

Multi-color brain datasets were registered to ABA based on the neuron channel using the MIRACL pipeline and segmented into individual brain regions based on the registration results. The signals of Aβ plaques were enhanced using the Difference of Gaussians filter (DoG operator), and the plaques were detected based on the OTSU threshold. Finally, the extracted signals were marked in the connected domain, and the area and centroid characteristics were used to remove signal interference at the boundary of the brain region.

Quantification

Calculation of relative tissue transparency

To evaluate the relative transparency of tissue samples using bright-field images, we estimated the average Michelson contrast (C) for different regions in each image, including the brain and background regions. The C was calculated as follows:

In the abovementioned Eq. (2), Imax indicates the mean gray value of selected rectangular regions of interest (ROIs) in the light parts of the images, whereas Imin indicates the mean gray value of selected ROIs in the dark parts of the images. Transparency (T) was calculated using the following formula:

In the abovementioned Eq. (3), Cbrain indicates the C of regions beneath the cleared brain tissue, whereas Cbackground indicates the C of background regions beyond the cleared brain tissue.

Calculation of the relative signal-to-background ratios

The relative signal-to-background ratios were calculated to assess fluorescence compatibility. Briefly, the maximum intensity projection (MIP) of image stacks from the tissue surface (50-μm thick) was obtained. The ‘threshold’ function in the Fiji software was used to extract vascular signals from the MIP image, and the mean value of the signal area was calculated as the average intensity of the fluorescence signal. The region without blood vessels in the image was manually selected using the marking function, and the mean value of this region was calculated as the average intensity of the background. The signal-to-background ratio was calculated as the mean signal intensity divided by the mean background intensity. The relative signal-to-background ratio was calculated as the signal-to-background ratio after clearing divided by the signal-to-background ratio before clearing.

Calculation of the relative sample size change

To assess sample expansion and shrinkage, bright-field images were captured before and after tissue clearing. Based on top-view images, the area of samples was determined using the ‘polygon-selections’ function in Fiji (Version 1.53, https://fiji.sc/). Changes in the relative sample size were determined based on changes in the area. It should be noted that the boundaries of highly-transparent samples were blurred in the original bright-field image, in this case, the brightness and contrast of such images should be adjusted via Fiji to clearly show the boundaries before tracing the sample outlines, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3A.

For the quantification of morphology preserving capability of clearing methods on neonatal mice, after finishing clearing of neonatal mouse bodies with different clearing methods, the brains were dissected and optically scanned via the light-sheet microscopy. The representative optical section images at similar positions for each method were used for quantifying the size change of cortex region with reference to ABA for neonatal mouse brain.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the mean ± SD and analyzed using the SPSS Statistics software (version 22; IBM, USA) with 95% confidence intervals. Sample sizes are indicated in the figure legends. To estimate statistical significance, the normality of data distribution in each experiment was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The homogeneity of variance in each group was evaluated using Levene’s test. To compare the data of three or more groups, P-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 3C). P-values of <0.05 were considered significant (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, the Supplementary Information files and the Source Data files that accompany this article. The raw image datasets with terabyte size could be made available upon request to the corresponding author. Requests for raw image data accessibility will be fulfilled with 4 weeks. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Lerner, T. N., Ye, L. & Deisseroth, K. Communication in neural circuits: Tools, opportunities, and challenges. Cell 164, 1136–1150 (2016).

Richardson, D. S. et al. Tissue clearing. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 84 (2021).

Lai, H. M., Ng, W. L., Gentleman, S. M. & Wu, W. Chemical probes for visualizing intact animal and human brain tissue. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 659–672 (2017).

Stelzer, E. H. K. et al. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 73 (2021).

Voigt, F. F. et al. The mesoSPIM initiative: open-source light-sheet microscopes for imaging cleared tissue. Nat. Methods 16, 1105–1108 (2019).

Voigt, F. F. et al. Reflective multi-immersion microscope objectives inspired by the Schmidt telescope. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 65–71 (2024).

Mano, T. et al. Whole-brain analysis of cells and circuits by tissue clearing and light-sheet microscopy. J. Neurosci. 38, 9330–9337 (2018).

Pan, C. et al. Shrinkage-mediated imaging of entire organs and organisms using uDISCO. Nat. Methods 13, 859–867 (2016).

Renier, N. et al. iDISCO: A simple, rapid method to immunolabel large tissue samples for volume imaging. Cell 159, 896–910 (2014).

Renier, N. et al. Mapping of brain activity by automated volume analysis of immediate early genes. Cell 165, 1789–1802 (2016).

Jing, D. et al. Tissue clearing of both hard and soft tissue organs with the PEGASOS method. Cell Res. 28, 803–818 (2018).

Qi, Y. et al. FDISCO: Advanced solvent-based clearing method for imaging whole organs. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau8355 (2019).

Cai, R. et al. Panoptic imaging of transparent mice reveals whole-body neuronal projections and skull–meninges connections. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 317–327 (2019).

Pan, C. et al. Deep learning reveals cancer metastasis and therapeutic antibody targeting in the entire body. Cell 179, 1661–1676 (2019).

Cai, R. et al. Whole-mouse clearing and imaging at the cellular level with vDISCO. Nat. Protoc. 18, 1197–1242 (2023).

Mai, H. et al. Whole-body cellular mapping in mouse using standard IgG antibodies. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 617–627 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. Cellular and molecular probing of intact human organs. Cell 180, 796–812 (2020).

Mai, H. et al. Scalable tissue labeling and clearing of intact human organs. Nat. Protoc. 17, 2188–2215 (2022).

Susaki, EtsuoA. et al. Whole-brain imaging with single-cell resolution using chemical cocktails and computational analysis. Cell 157, 726–739 (2014).

Tainaka, K. et al. Chemical landscape for tissue clearing based on hydrophilic reagents. Cell Rep. 24, 2196–2210 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. F-CUBIC: A rapid optical clearing method optimized by quantitative evaluation. Biomed. Opt. Express 13, 237–251 (2022).

Chung, K. et al. Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature 497, 332–337 (2013).

Murray, E. et al. Simple, scalable proteomic imaging for high-dimensional profiling of intact systems. Cell 163, 1500–1514 (2015).

Park, Y.-G. et al. Protection of tissue physicochemical properties using polyfunctional crosslinkers. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 73–83 (2019).

Lai, H. M. et al. Next generation histology methods for three-dimensional imaging of fresh and archival human brain tissues. Nat. Commun. 9, 1066 (2018).

Lee, K. et al. Optimised tissue clearing minimises distortion and destruction during tissue delipidation. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 47, 441–453 (2020).

Hsu, C.-W. et al. EZ Clear for simple, rapid, and robust mouse whole organ clearing. eLife 11, e77419 (2022).

Li, W., Germain, R. N. & Gerner, M. Y. Multiplex, quantitative cellular analysis in large tissue volumes with clearing-enhanced 3D microscopy (Ce3D). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E7321–E7330 (2017).

Zhu, J. et al. MACS: Rapid aqueous clearing system for 3D mapping of intact organs. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 7, 1903185 (2020).

Ueda, H. R. et al. Tissue clearing and its applications in neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 61–79 (2020).

Todorov, M. I. et al. Machine learning analysis of whole mouse brain vasculature. Nat. Methods 17, 442–449 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. D-LMBmap: A fully automated deep-learning pipeline for whole-brain profiling of neural circuitry. Nat. Methods 20, 1593–1604 (2023).

Murakami, T. C. et al. A three-dimensional single-cell-resolution whole-brain atlas using CUBIC-X expansion microscopy and tissue clearing. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 625–637 (2018).

Kirst, C. et al. Mapping the fine-scale organization and plasticity of the brain vasculature. Cell 180, 780–795 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. The Allen mouse brain common coordinate framework: A 3D reference atlas. Cell 181, 936–953 (2020).

Inoue, M., Saito, R., Kakita, A. & Tainaka, K. Rapid chemical clearing of white matter in the post-mortem human brain by 1,2-hexanediol delipidation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 29, 1886–1890 (2019).

Niedworok, C. J. et al. aMAP is a validated pipeline for registration and segmentation of high-resolution mouse brain data. Nat. Commun. 7, 11879 (2016).

Goubran, M. et al. Multimodal image registration and connectivity analysis for integration of connectomic data from microscopy to MRI. Nat. Commun. 10, 5504 (2019).