Abstract

The CRISPR-Cas12a system has revolutionized nucleic acid testing (NAT) with its rapid and precise capabilities, yet it traditionally required RNA pre-amplification. Here we develop rapid fluorescence and lateral flow NAT assays utilizing a split Cas12a system (SCas12a), consisting of a Cas12a enzyme and a split crRNA. The SCas12a assay enables highly sensitive, amplification-free, and multiplexed detection of miRNAs and long RNAs without complex secondary structures. It can differentiate between mature miRNA and its precursor (pre-miRNA), a critical distinction for precise biomarker identification and cancer progression monitoring. The system’s specificity is further highlighted by its ability to detect DNA and miRNA point mutations. Notably, the SCas12a system can quantify the miR-21 biomarker in plasma from cervical cancer patients and, when combined with RPA, detect HPV at attomole levels in clinical samples. Together, our work presents a simple and cost-effective SCas12a-based NAT platform for various diagnostic settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fast, accurate, and cost-effective nucleic acid testing (NAT) is vital for wide areas, including public health, disease diagnostics, environmental sciences, food safety, etc. Over the past decades, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) has been considered as a gold standard technique for NAT1,2. However, the qPCR-based diagnostic methods require expensive instruments and time-consuming procedures, significantly limiting their applications in the field of point-of-care testing (POCT). To overcome these shortcomings, analytical methods utilizing CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)-Cas enzymes such as Cas12a3,4, Cas12b5, Cas13a6, and Cas147 have been rapidly developed in recent years8,9. Among the discovered CRISPR-Cas enzymes, CRISPR-Cas12a exhibits a unique ability that can indiscriminately cut any nearby non-specific single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecules after target-specific recognition and cleavage of DNA10. The trans-cleavage catalytic property has been utilized to develop various diagnostic tools, such as DETECTR3,11 and HOLMES4, for highly sensitive detection of DNA and RNA. In contrast to the direct detection of DNA, RNA substrates must undergo reverse transcription12,13 to be converted to DNA prior to recognition by Cas12a. When the detected object is miRNA14, a short RNA molecule consisting of approximately 20–22 nucleotides, the process of obtaining high-quality DNAs through reverse transcription becomes more challenging. Additional sample amplification steps are frequently required, leading to prolonged experimental durations (~2 h) and significantly increasing the risk of aerosol contamination. Although other CRISPR enzymes, such as CRISPR-Cas13a, enable direct detection of miRNA, they still pose challenges in mitigating the interference caused by longer precursor RNAs (pre-miRNAs). The limit of detection (LoD) for Cas13a-based methods, such as SHERLOCK15,16, typically exceeds 10 pM for miRNA targets17, thereby rendering them unsuitable for various clinical applications. Compared to Cas12a, which utilizes ssDNA probes, Cas13a employs RNA probes18 that are more expensive and prone to degradation. Consequently, this increases the risk of generating false positive results and escalates testing expenses. Together, it is urgent to develop new Cas12a-based diagnostic tools to address these issues.

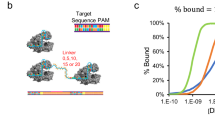

Recently, Jain et al. developed a diagnostic method that, for the first time, enables direct detection of RNA by Cas12a19. By supplying a short ssDNA or a PAM-containing dsDNA at the seed region of the crRNA, the method detected RNA substrates at the 3’-end of the crRNA. However, the utilization of the “split-activator combination” strategy only partially restored the activity of Cas12a ribonucleoprotein (RNP), resulting in a high LoD ranging from 100–700 pM against different RNA targets. Hence, further enhancements are required for the Cas12a assay to effectively detect RNA. In our previous work20, we observed that the Cas12a protein exhibits a strong binding affinity towards a truncated fragment of crRNA (scaffold RNA), which contains a fixed 20-nt sequence: 5’-AAUUUCUACUAAGUGUAGAU-3’. In comparison to the wild-type Cas12a RNP illustrated in Fig. 1a, which includes a 40-nt intact crRNA, this deficient Cas12a RNP did not exhibit any nuclease activity, possibly due to the lack of spacer RNA. Recently, this “Cas12a-scaffold RNA” complex has also been reported by other researchers21,22. For instance, Shebanova et al.22. demonstrated that a split crRNA, comprising separate scaffold and spacer RNA components, can induce precise cis-cleavage in Cas12a. However, the researchers did not extensively investigate the steric effect on the enzyme’s trans-cleavage. In light of these results, we have chosen to employ the split Cas12a system (SCas12a, Fig. 1b), comprising the Cas12a protein, a scaffold RNA, and a spacer RNA, for the development of nucleic acid detection methods.

a Schematic illustration of the wild-type Cas12a RNP. b Schematic illustration of the split Cas12a RNP. c The principle of the amplification-free fluorescence assay developed for the direct detection of miRNA target in this study. d The principle of the fluorescence assay for the direct of DNA target in this study.

In this study, we initially discover that the trans-cleavage activity of SCas12a RNP is similar to that of wild-type Cas12a RNP. Taking advantage of the SCas12a system, we establish a fluorescence assay for highly sensitive, selective, and multiplexed detection of miRNAs, eliminating the need for additional reverse transcription and pre-amplification. This approach achieves an average LoD value of 100 femtomoles (fM). Subsequently, we devise lateral flow assay (LFA) for rapid miRNA detection with a lower LoD of 10 fM. Moreover, our approach demonstrates the capability to identify long-sized RNA molecules without complex secondary structures. Interestingly, the SCas12a assay demonstrates the ability to distinguish between mature miRNA and pre-miRNA with identical sequences, a task that cannot be accomplished by Cas13a or other Cas12a based diagnostics. The discrimination of miRNA and pre-miRNA within living cells23,24 is crucial for precise molecular diagnostics and therapeutics, allowing for specific biomarker identification, understanding gene regulation, and preventing inaccurate conclusions in biomedical research and clinical settings. In addition, the results indicate that the SCas12a assay exhibits remarkable specificity towards DNA and miRNA point-mutations. Ultimately, employing this method, we successfully identify the miRNA biomarker in cervical cancer patients and detect attomolar levels of human papillomavirus (HPV) when combined with recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA). Together, we develop a diagnostic approach utilizing SCas12a that enables the rapid, cost-effective, and highly sensitive detection of both RNA and DNA.

Results

Proof-of-principle studies for the development of SCas12a-based diagnostic method

Figure 1 illustrates the working mechanism of the split Cas12a system developed in this study. To obtain the designed SCas12a RNP (Fig. 1b), we firstly mixed the purified recombinant Acidaminococcus sp. Cas12a (AsCas12a) protein (Supplementary Fig. 1) with synthesized scaffold RNA and spacer RNA at a ratio of 1: 2: 2 in vitro. Then, we assessed the cis-cleavage activity (Fig. 2a) of this variant by measuring its on-target cleavage using targeted dsDNA plasmids containing a DNA fragment of HPV16 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Comprehensive information regarding this plasmid is available in the section of Materials and Methods. Next, we investigated the trans-cleavage (Fig. 2b, c) capabilities of the variant by addition of the complementary dsDNA or ssDNA substrates, along with non-specific ssDNA probes for cutting. As depicted in Fig. 2b, a 59-bp dsDNA target was introduced alongside a 42-nt ssDNA reporter. Both the cis-cleavage and trans-cleavage products were labeled. Likewise, the gel in Fig. 2c featured a 59-nt ssDNA target and a 42-nt ssDNA reporter. The electrophoresis data revealed that nearly 100% cis- and trans-cleavage activities of the wild-type Cas12a RNP were recovered, which is consistent with a previous study22. Encouraged by these promising results, we subsequently conducted proof-of-principle studies to develop diagnostic methods based on the SCas12a system.

a Cis-cleavage of the target dsDNA plasmids by wild-type Cas12a RNPs (blue) and split Cas12a RNPs (orange). The reactions contained 50 nM Cas12a, 100 nM crRNA (or 100 nM split RNA), and 10 nM target dsDNA plasmids. b Trans-cleavage of ssDNA probes by wild-type Cas12a RNPs (blue) and split Cas12a RNPs (orange) in the presence of target or non-target dsDNA substrates. The reactions contained 50 nM Cas12a, 100 nM crRNA (or 100 nM split RNA),10 nM complementary dsDNA activators (or 10 nM non-target dsDNA), as well as 20 nM ssDNA probes. c Trans-cleavage of ssDNA probes by wild-type Cas12a RNPs (blue) and split Cas12a RNPs (orange) in the presence of target or non-target ssDNA substrates. The reactions contained 50 nM Cas12a, 100 nM crRNA (or 100 nM split RNA),10 nM complementary ssDNA activators (or 10 nM non-target ssDNA), as well as 20 nM ssDNA probes. For a to c, all the experiments were performed three times.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3a, a very strong “turn-on” fluorescence was generated exclusively in the presence of Cas12a enzyme, scaffold RNA, spacer RNA, and targeted dsDNA. The fluorescence intensity of SCas12a RNP was identical to that of wild-type Cas12a RNP. On the contrary, neither Cas12a nor Cas12a plus scaffold RNA unlocked collateral cleavage activity and almost no fluorescence signals were observed. Cas12a plus spacer RNA only partially activated trans-cleavage and a significantly reduced fluorescence signal was observed, which demonstrated that Cas12a protein, scaffold RNA and spacer RNA are all necessary to rebuilt the Cas12a RNP with complete trans-cleavage activity. This phenomenon has also been recently reported in AsCas12a by another group25. This is likely attributed to the interaction between a high concentration of spacer RNA and the ssDNA or dsDNA target, resulting in the formation of a compromised ternary complex for AsCas12a. In order to achieve a thorough comprehension of this phenomenon, it is essential to conduct crystallographic analysis on an AsCas12a effector complexed with scaffold RNA, both with and without spacer RNA, to elucidate potential conformational changes that could affect the binding site interaction with the spacer RNA. In addition, the non-target dsDNA substrates with mismatched sequences were unable to initiate the trans-cleavage activity of SCas12a, highlighting the high specificity of the assay. Similarly, the 20-nt ssDNA target can completely activate the trans-cleavage (Supplementary Fig. 3b) under identical reaction conditions. Moreover, the real-time fluorescence kinetics of both dsDNA and ssDNA targets were measured and the corresponding data were illustrated in Fig. 3. These findings show that the SCas12a system can be activated by both dsDNA and ssDNA, with ssDNA being more effective in activating Cas12a’s trans-cleavage activity. Finally, kinetic assays were performed by introducing spacer RNAs with diverse sequences (Supplementary Table 1). All the reactions were completed within 10 min without a sequence basis (Supplementary Fig. 4), indicating that the SCas12a-based detection method has the potential to become a universal NAT platform.

a, b Detection of target DNA by SCas12a or wild-type Cas12a. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 60 min at 37 °C and contained 250 nM of Cas12a, 500 nM of crRNA or split RNA, 500 nM of target or non-target DNA (dsDNA for a and ssDNA for b), and 1000 nM of fluorescent probes. All the experiments were conducted in triplicate and error bars represent mean value +/− SD (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Amplification-free miRNA detection by SCas12a-based assay

At first, we noticed that spacer RNAs have the same structure and characteristics as miRNAs, which typically comprise 20 nucleotides. Hence, we proposed a straightforward “reverse activation” strategy (Fig. 1c) for directly monitoring miRNA target. According to the design, the presence of both scaffold RNA and an excess of ssDNA activators (containing 20-nt deoxyribonucleotides complementary to the miRNA) results in the activation of the trans-cleavage activity of Cas12a. In other words, the miRNA target functions similar to the spacer RNA depicted in Fig. 1b, enabling direct detection of miRNA without the necessity for additional reverse transcription and sample amplification. Subsequently, we conducted sensitivity testing of the SCas12a fluorescence assay by designing a series of ssDNA activators that are specific to clinically significant microRNAs implicated in cancer progression. These microRNAs are known to be upregulated in tumor tissues, including miR-21, miR-31, miR-17, and miR-let-7a. For example, a series of dilutions of miR-21 targets (Fig. 4a) were prepared, ranging in concentrations from 10 fM to 1 nM. The detection of each target was evaluated by the addition of excess ssDNA activators, resulting in a LoD of 21 fM as determined by the equation outlined in the Materials and Methods section. Similarly, we achieved LoDs ranging from 70 fM to 294 fM for the remaining three miRNAs, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. The average LoD of 100 fM demonstrates the robustness of our assay in detecting various microRNA substrates. Furthermore, we established the linear relationship (Supplementary Fig. 6) between fluorescence intensity and the concentration of standard miR-21 samples depicted in Fig. 4a, supporting the feasibility of quantifying miRNA through the utilization of our methodology.

a Limit of detection of the miR-21 target was determined by a fluorescence assay. The plot illustrates the background-subtracted fluorescence intensity at t = 20 min for varying concentrations of the target. All the experiments were conducted in triplicate and error bars represent mean value +/− SD (n = 3), and statistical analysis was conducted using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical significance was determined as follows: ns (not significant) for p > 0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05, ** for p ≤ 0.01, *** for p ≤ 0.001, and **** for p ≤ 0.0001. b Limit of detection of the miR-21 target was determined by a lateral flow assay. Similar experiments were conducted, with the exception that a dipstick reporter was employed following a 20-minute LFA cleavage reaction. The red arrow indicates the test bands, while the green arrow indicates the control bands. The results are denoted by the symbols “+“ for positive outcomes and “−“ for negative outcomes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we explored the potential of utilizing orthologs of Cas12a nucleases for target recognition and cleavage through the split crRNA design. A fluorescence assay was performed to establish LoD for miRNA using LbCas12a (Lachnospiraceae bacterium ND2006). The results (Supplementary Fig. 7) indicated a notably diminished detection efficiency, which is ~100 times lower than that of AsCas12a. As a result, AsCas12a was chosen for further research.

Finally, we measured the sensitivity of the SCas12a system by using a rapid lateral flow assay. Unexpectedly, a low LoD of 10 fM was observed in Fig. 4b, representing a reduction of one order of magnitude compared to the measurement obtained through the fluorescence assay. These experiments were conducted three times using LFA dipsticks from two different companies, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 8. The observed results may be explained by the increased local concentrations of several components present within the dipstick, including the Cas12a enzyme, scaffold RNA, ssDNA activator, ssDNA probes and the miRNA targets. Furthermore, our current research endeavours focus on enhancing the sensitivity of the SCas12a system by creating a digital miRNA assay that eliminates the need for amplification, in combination with a microfluidic device.

Application of SCas12a-based fluorescence assay for multifunctional RNA detection

To evaluate the selectivity of the SCas12a fluorescence assay, we firstly tested and compared several types of miRNAs (miR-17, miR-31, and miR-let-7a) with the miR-21 target. In comparison to miR-21 (Fig. 5a), none of the non-targeted miRNAs at concentrations 100 times higher exhibited an increase in fluorescence signal, demonstrating the high specificity of the SCas12a assay. Subsequently, we evaluated the efficacy of our approach for simultaneous detection of multiple miRNAs. This was achieved by employing two different ssDNA activators that target specific miRNAs (miR-17 and miR-31), either individually or pooled them together. The results (Fig. 5b) indicate that the identified miRNAs can be detected individually or simultaneously without mutual interference. Additionally, the SCas12a assay demonstrates feasibility for multiplexed detection of DNA and RNA by introducing DNA targets and the corresponding spacer RNA activators. This finding is significant as multi-target biomarkers, such as miRNA and circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA), exhibit greater accuracy in the early diagnosis of cancer compared to single indicators. Furthermore, we investigated the efficacy of the method for quantifying miRNAs in real biological samples. Specifically, total RNA was extracted from various batches of MCF-7 breast cancer cells utilizing a commercial RNA extraction kit, followed by the quantification of miR-21 levels in real-time using the SCas12a fluorescence assay or RT-qPCR. The results (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 9) indicate a strong correlation between the two methods. In conclusion, we have developed a straightforward and precise diagnostic method utilizing SCas12a for the detection of miRNA without the need for amplification. This technique shows promise for facilitating multiplexed miRNA and ctDNA liquid biopsy applications in the context of cancer diagnosis and prognosis.

a Selective detection of the target miR-21 (10 pM) in the different types of miRNAs (1 nM), including miR-17, miR-31 and miR-let-7a. b Multiplexed detection of miR-17 and miR-31 in the same reaction. c Heatmap of the estimated concentrations of target miR-21 using the SCas12a assay or conventional RT-qPCR assay. d Schematic of an HIV RNA target and three ssDNA activators targeting it at different positions. The predicted secondary structure of this HIV RNA was determined using NUPACK software. e Comparison among the head, mid, tail and pooled HIV targeting ssDNA activators. f Schematic of the detection of mature miRNA and pre-miRNA using SCas12a or Cas13a based fluorescence assay. g Comparison of fluorescence intensity changes between pre miR-21 and mature miR-21 measured using Cas13a, SCas12a or Asymmetric CRISPR assay. The concentrations of pre-miR-21 and mature miR-21 were both 10 nM in each reaction. For a, b, e, and g, all the experiments were conducted in triplicate and error bars represent mean value +/− SD (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Upon closer inspection of the structure of SCas12a RNP (Fig. 1b), we hypothesized that the RNA targets with a high amount of secondary structure, such as stems and cloverleaves, are more inaccessible to bind to the “Cas12a-scaffold RNA” complex, and are therefore harder to detect, while targets with relatively low or no secondary structure are detected easily. To test this, we firstly detected a 60-nt RNA fragment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with three specifically designed ssDNA activators (Fig. 5d). The predicted secondary structure of the RNA target, as illustrated in Fig. 5d, was determined using NUPACK software. The results (Fig. 5e) revealed notable variations in trans-cleavage activity, with the head-targeting activator demonstrating a 4 to 6-fold increase in activity compared to both the mid-targeting and tail-targeting activators. In addition, the method displayed enhanced activity when utilizing pooled ssDNA activators, a phenomenon previously observed with the Cas13a enzyme18. Therefore, we propose the adoption of pooled ssDNA activators for the detection of long-sized RNA targets.

Distinguish between mature miRNA and pre-miRNA by SCas12a assay

We hypothesized that the observed steric hindrance effect could potentially be utilized as a means of distinguishing between mature miRNAs and pre-miRNAs that contain identical miRNA sequences (Fig. 5f). To verify this, the levels of miR-21 and pre-miR-21 were quantified at equivalent concentrations through fluorescence assays employing Cas13a, SCas12a and the recently reported Asymmetric CRISPR system21. The results obtained from SCas12a (Fig. 5g) indicated a 2500-fold increase in fluorescence intensity for mature miR-21 compared to pre-miR-21. In contrast, when using either Cas13a or the Asymmetric CRISPR assay (Fig. 5g), no significant difference in fluorescence intensity was observed between mature miR-21 and pre-miR-21. The differentiation between miRNA and pre-miRNA within cellular contexts has been identified as essential for accurate molecular diagnostics23,24. Herein, our findings suggested false positive results with high levels of mature miRNAs identified by Cas13a-based diagnostic methods, a phenomenon that was likely disregarded in previous studies. In conclusion, the use of SCas12a, which utilizes a cost-effective ssDNA probe and demonstrates markedly higher sensitivity (10 fM vs 10 pM) in comparison to Cas13a, indicates its superiority as a diagnostic tool for detecting mature miRNAs with improved precision, sensitivity, and cost-effectiveness.

Clinical validation of the SCas12a assay for miRNA detection

Liquid biopsies of miRNAs, which identify alterations in miRNA expression levels in bodily fluids such as blood, urine, or saliva, offer crucial diagnostic and prognostic insights into cancer diseases26. For example, studies have demonstrated a specific overexpression of miR-21 in cervical cancer patients27, which contributes to the growth and metastasis of this type of cancer. Here, we measured the expression level of miR-21 in the plasma samples obtained from patients diagnosed with cervical cancer using the SCas12a assay (Fig. 6a).

a Schematic illustration of miRNA detection in human plasma samples using SCas12a assay. b Estimated target miR-21 concentrations in the plasma samples from cervical cancer patients (samples 1–7) and healthy donors (samples 8–10). Error bars indicate the mean value ± standard deviation of three technical replicates. c miR-21 expression level measured by SCas12a assay (red) and RT-qPCR (gray) in cervical cancer patients and healthy donors. The median expression level is represented by the center line, the interquartile range is indicated by the bounds of the box, and the maximum and minimum values are represented by the whiskers. Data are represented as the mean value ± standard deviation of three technical replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

First, we extracted total RNA from plasma samples obtained from seven individuals (aged 25 to 60 years) diagnosed with cervical cancer and three healthy individuals (aged 25 to 60 years) utilizing a commercially available RNA extraction kit. Next, the isolated RNAs were combined with the SCas12a reaction system, followed by the collection of fluorescence signals. Subsequently, the concentration of the target miR-21 in each plasma sample was estimated using the standard curve of miR-21 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Consequently, it was confirmed that the overall expression level of miR-21 was significantly elevated in the cervical cancer samples in comparison to the samples from healthy donors (Fig. 6b). Additionally, the identical clinical samples were analyzed using RT-qPCR, revealing a robust correlation with the findings obtained through the SCas12a assay (Fig. 6c). Taken together, these findings illustrate that our SCas12a assay facilitates a straightforward, expeditious, and amplification-free identification of miRNA in clinical specimens with heightened sensitivity, thereby substantiating its potential utility in clinical settings.

SCas12a-based fluorescence assay improves mutation specificity of DNA detection

To achieve complete assembly of the functional RNP, it is essential for the Cas12a protein to bind correctly to both scaffold RNA and spacer RNA. Given this hypothesis, we suggest that SCas12a may demonstrate increased sensitivity in detecting DNA single point mutations when compared to the wild-type Cas12a. To validate this, we designed a 20-nt spacer RNA with single-point mutations (Fig. 7a) for the detection of SCas12a, as well as a 40-nt crRNA with identical mutations for the detection of wild-type Cas12a. The results of a side-by-side comparison were shown in Fig. 7b. In summary, our studies reveal that SCas12a demonstrates greater sensitivity in detecting single-point mutants. Specifically, the findings indicate that mutations at positions M2-M6, M14, and M19 substantially reduce SCas12a-mediated trans-cleavage activity, whereas mutations at M4 and M19 notably diminish trans-cleavage activity mediated by wild-type Cas12a. Additionally, these data suggest that SCas12a exhibits enhanced specificity towards mutations located in close proximity to the 5’ or 3’ end of spacer RNA. This heightened specificity is likely a result of the split RNA design of the SCas12a system, which restricts Cas12a enzyme activity to situations where scaffold RNA, spacer RNA, and target dsDNA are all present correctly. This strict regulation of the ternary complex leads to improved sensitivity in detecting single point mutations, as changes near the binding region are more likely to disrupt binding and cleavage functions. Overall, this characteristic of SCas12a has the potential to be utilized for advancing reliable single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) diagnostic tools in the future.

a Split RNA (SCas12a) and crRNA (WT Cas12a) activators were designed with point mutations across the length of the pairing region in a HPV16-derived DNA target. The mutation location is identified by ‘M’ following the nucleotide number where the base has been changed to its complementary deoxynucleotide (3’ to 5’ direction). b Comparison of fluorescence fold changes for the trans-cleavage between wild-type Cas12a assay and the SCas12a assay. All fluorescence values were normalized to those of the WT crRNA activator. Statistical analysis for n = 3 biologically independent replicates comparing the normalized fold change for the WT Cas12a assay vs. SCas12a assay. Statistical analysis was conducted using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical significance was determined as follows: ns (not significant) for p > 0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05, ** for p ≤ 0.01, *** for p ≤ 0.001, and **** for p ≤ 0.0001. Eerror bars represent mean value +/− SD (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

SCas12a-based fluorescence assay enhances mutation specificity of miRNA detection

As mentioned above, our research has indicated the efficacy of the SCas12a-based fluorescence assay for the specific detection of individual miRNA targets. The present study aims to evaluate the sensitivity of this assay in detecting single point mutations in miRNAs. Simultaneously, the Asymmetric CRISPR assay21 was carried out for a side-by-side comparison. The results (Fig. 8) reveal that our SCas12a assay demonstrates greater sensitivity in detecting single-point mutants across all 22 positions, especially for the mutations at positions M3, M5-M7, M11-M13, and M16. Notably, the Asymmetric CRISPR assay cannot discriminate differences at positions M1 to M12 because this method is specifically designed to bind only to a 10-nt segment of the target miRNA. Taken together, the SCas12a-based fluorescence assay demonstrates its capability for reliable SNP detection in both DNA and RNA targets.

a ssDNA activators were designed with point mutations across the length of the pairing region in a miR-21 target. The mutation location is identified by ‘M’ following the nucleotide number where the base has been changed to its complementary nucleotide (3’ to 5’ direction). b Comparison of fluorescence fold changes for the trans-cleavage between the SCas12a assay and Asymmetric CRISPR assay. All fluorescence values were normalized to those of the WT miR-21 target. Statistical analysis for n = 3 biologically independent replicates comparing the normalized fold change for the SCas12a assay vs Asymmetric CRISPR assay. Statistical analysis was conducted using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical significance was determined as follows: ns (not significant) for p > 0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05, ** for p ≤ 0.01, *** for p ≤ 0.001, and **** for p ≤ 0.0001. error bars represent mean value +/− SD (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Application of SCas12a-based assay for DNA detection

The wild-type CRISPR-Cas12a system has been extensively adopted for the identification of DNA targets in combination with nucleic acid amplification methodologies, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA)28,29, and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)30,31. In this study, we initially examined the sensitivity of the SCas12a assay for the amplification-free detection of DNA. As a case study, we chose HPV16 as the test DNA substrate. Briefly, HPV16-containing plasmids were incubated with ssDNA fluorescence probes and the SCas12a RNP targeting HPV16 fragments. We achieved a LoD of 10 pM through fluorescence assay (Fig. 9a), which is consistent with previous studies using wild-type Cas12a17. In addition, a LoD of 1 pM was attained through LFA (Fig. 9b). Therefore, the LoD for double-stranded DNA targets is ~100 times higher than that for miRNA targets in the SCas12a assay. It is hypothesized that variations in detection thresholds among different targets are inherently associated with the level of activation of the Cas12a enzyme’s trans-cleavage activity. Previous studies3,17 have shown that ssDNA can better activate Cas12a’s trans-cleavage activity compared to dsDNA. This finding is consistent with the detection of miRNA using the SCas12a assay, which involves the introduction of a ssDNA activator.

a Determination of limit of detection of DNA by SCas12a fluorescence assay with or without RPA. Statistical analysis was conducted using a two-tailed t-test. Statistical significance was determined as follows: ns (not significant) for p > 0.05, * for p ≤ 0.05, ** for p ≤ 0.01, *** for p ≤ 0.001, and **** for p ≤ 0.0001. error bars represent mean value +/− SD (n = 3). b Direct detection of DNA by SCas12a-based lateral flow assay. The red arrow indicates the test bands, while the green arrow indicates the control bands. The results are denoted by the symbols “+“ for positive outcomes and “−“ for negative outcomes. c Schematic outlining DNA extraction from human vaginal secretion samples to HPV identification by SCas12a fluorescence assay. The proteinase K was inactivated before the RPA process. d Identification of HPV16 in 25 clinical samples by qPCR (up) and SCas12a fluorescence assay (down). Error bars indicate the mean value ± standard deviation of three technical replicates. e Identification of HPV16 in 25 clinical samples by qPCR (left) and SCas12a assay (right). The heatmap of SCas12a assay represents normalized mean fluorescence values. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further enhance the sensitivity of the SCas12a assay for DNA, we have developed fluorescence assays that integrate RPA isothermal amplification in either a stepwise or one-pot manner. As a result, the utilization of the one-pot approach (Fig. 9a) has been proven highly effective in facilitating the detection of targets at attomolar concentrations. To investigate the utility of our method for analysing real clinical samples, we tested crude DNA extraction from 25 (aged 25 to 60 years) human vaginal secretion samples (Fig. 9c) that had previously been analysed for HPV16 infection using qPCR (Fig. 9d). Within 30 min, the method accurately identified HPV16 (25/25 agreement) in these clinical samples (Fig. 9d), showing excellent correlation with the qPCR results (Fig. 9e). In conclusion, our findings indicate that the one-pot SCas12a assay possesses comparable DNA detection capabilities to DETECTR3. Therefore, in this study, we have developed a diagnostic approach that employs Cas12a and split crRNA for efficient, cost-effective, and highly accurate DNA analysis.

Discussion

CRISPR-Cas12a has been extensively studied and widely used in DNA-based diagnostic platforms. In the context of RNA detection using Cas12a, reverse transcription and subsequent amplification reactions are required since the Cas12a enzyme does not naturally tolerate RNA substrates. In a recent study, Jain et al. developed a split-activator-based method SAHARA19 for programmable RNA detection with Cas12a. However, their diagnostic method has two major limitations: (i) only picomolar levels (250–700 pM) of RNA detection was obtained, which falls short of clinical testing requirements, and (ii) the specificity in more complex samples is not good enough since the method is designed to only bind to 12-nt of the target RNA. Upon a thorough inspection of the “Cas12a-crRNA-split activator” complex, we discovered that this complex is too crowded, making it difficult for the RNA substrates to enter and resulting in decreased trans-cleavage activity. To resolve this problem, we propose a simple strategy by combining the Cas12a enzyme with a split crRNA comprising scaffold RNA and spacer RNA components. Compared to the wild-type Cas12a, the designed SCas12a RNP undergoes minimal structural changes.

In this study, we initially observed that the SCas12a RNP exhibits trans-cleavage activity similar to that of wild-type Cas12a RNP. By utilizing miRNA targets as spacer RNA and another single-stranded DNA as the activator, SCas12a-based fluorescence and rapid lateral flow assays were developed, enabling highly sensitive and selective detection of miRNA without the requirement for reverse transcription and pre-amplification. Additionally, our SCas12a assay facilitated the simultaneous detection of multiple miRNAs, the quantitative analysis of miRNAs originating from cancer cells and human plasma samples, as well as the identification of long-sized RNAs lacking complex secondary structures. In contrast to Cas13a and other Cas12a based diagnostic techniques, the established SCas12a assay has the capability to differentiate between mature miRNA and pre-miRNA with identical sequences. Moreover, our study demonstrated that SCas12a exhibits remarkable specificity towards DNA and miRNA point mutations, highlighting its potential for the development of reliable SNP diagnostics. Finally, we combined RPA with fluorescence methodology to establish a one-pot SCas12a detection platform, successfully detecting attomolar levels of HPV16 in clinical specimens.

While preparing this work, we noticed an Asymmetric CRISPR assay21 that was recently reported. This assay exploits the competitive trans-cleavage properties of full-sized and split crRNAs for Cas12a. Although both involve a split crRNA, our SCas12a assay significantly diverges from this approach in its fundamental principle. Firstly, their method involves a complex reaction system which comprises Cas12a enzyme, full-sized crRNA, target DNA, scaffold RNA, spacer RNA, ssDNA activator, and FAM-ssDNA probe. In contrast, the reaction system utilized in our SCas12a assay demonstrates remarkable simplicity by eliminating the need for full-sized crRNA and additional ssDNA activator. Additionally, the Asymmetric CRISPR assay relies on effective suppression of Cas12a system activation by full-length crRNA in the presence of split crRNA and corresponding substrates to prevent false positives. Achieving this inhibition requires relatively stringent conditions; however, such limitations do not apply to the SCas12a assay as it does not require a full-sized crRNA. Lastly, that method is specifically designed to bind only to a 10-nt segment of the target miRNA, enhancing the probability of detecting similar RNA sequences within complex biological materials while precluding the detection of individual nucleotide mutations in miRNA.

In summary, we have devised a diagnostic approach utilizing Cas12a and split crRNA that offers several advantages1: the utilization of a more cost-effective and stable 20-nt spacer RNA in lieu of the 40-nt crRNA in conventional Cas12a assays2, the accurate identification of mature miRNA rather than pre-miRNA for the first time3, the ability to concurrently detect multiple cancer biomarkers such as miRNA and ctDNA, and4 a remarkable specificity towards point mutations in both DNA and miRNA targets. Furthermore, the straightforward “split-crRNA-activator” approach employed in this study can be extended to other CRISPR-Cas enzymes for the advancement of molecular diagnostics.

Despite its numerous advantages, the current version of the SCas12a assay is still subject to certain limitations. One notable drawback is its vulnerability to interference from the secondary structure of the target, particularly in cases where steric hindrance is present. This limitation could be addressed through the utilization of pooled spacer RNAs, the exploration of alternative split crRNA systems, and the engineering of Cas12a enzymes. We are currently developing an enhanced version of the SCas12a system, designed to effectively identify long-sized RNA molecules with any secondary structures. In addition, the SCas12a assay exhibits the capability to detect double-stranded DNA without requiring a PAM when in conjunction with transcription. For instance, the double-stranded DNA targets can be amplified and transcribed into RNA in vitro, facilitating subsequent quantification via the SCas12a assay. In the future, the SCas12a assay can be combined with a plethora of Cas12a detection techniques, such as MiCaR32 and Auto-CAR33, to create robust diagnostic tools capable of detecting multiple DNA and RNA targets in a mixture with high sensitivity and quantification. Collectively, this study presents a promising nucleic acid detection technique with the potential for application in clinical settings for commercial purposes.

Methods

Ethical statement

In this research, human vaginal section samples were collected for HPV16 detection from the department of pharmacy at Henan Cancer Hospital, following a protocol approved by the ethics committee at Zhengzhou University. Furthermore, human plasma samples from both healthy donors and cervical cancer patients were obtained from the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, also following a protocol approved by the ethics committee at Zhengzhou University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the research.

Materials

The DNA, RNA, FAM-labeled single-stranded DNA, and FAM-labeled RNA fluorescence reporters listed in Supplementary Table S1 were obtained from Sangong Biotech (Shanghai, China). The general chemicals for buffer preparation were purchased from Sinopharm (Beijing, China). The proteinase K, 10 x NEB buffer 2.1 and 10 x Cutsmart buffer were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beijing, China). The RNA extraction miRCURY LNA RT Kit was purchased from Qiagen. The RNAprep Pure Blood Kit was purchased from TIANGEN (Beijing, China). The MCF-7 cell line was purchased from Pricella (Wuhan, China). The Ultrapure water was employed throughout the research. All DNA oligonucleotides and RNA were dissolved in the DEPC (RNase-free) water, and stored at −20 oC for subsequent experiments.

Recombinant AsCas12a and LwaCas13a protein expression and purification

The genes encoding AsCas12a (Acidaminococcus sp. Cas12a) and LwaCas13a (Leptotrichia wadei. Cas13a) were synthesized and subsequently inserted into a pET-28a(+) vector to generate recombinant protein expression plasmids. These plasmids, confirmed to be correctly sequenced, were then introduced into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells for expression. Briefly, a single colony was picked and overnight grown in LB culture with ampicillin (100 μg/mL). Then, the overnight cultures were transferred into 1-liter TB medium to an OD600 of 0.8, after which they were cooled on ice for 10 min before adding 0.5 mM IPTG and then incubated at 18 oC for 16 h. The cells were harvested followed by resuspended in buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, 5 mM β-mecaptoethanol) in addition to proteinase inhibitor. Next, the recombinant Cas enzymes were purified using a standard protocol34 involving Ni-NTA and HiLoad® 16/600 Superdex® size-exclusion columns. At last, the purified recombinant Cas enzymes were concentrated utilizing Millipore concentrators (100 KD), subjected to analysis through 10% SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 1). The protein concentration was measured by Broadford method. Finally, the concentrated Cas enzymes were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80oC for future use.

Gel electrophoresis

Initially, the wild-type Cas12a and SCas12a RNPs were reconstituted in reaction buffer through the combination of one of the Cas12a nucleases and corresponding full-sized crRNA or split crRNA at a 1:2 molar ratio, followed by a 20-minute incubation at room temperature. Subsequently, the cis-cleavage activity of the wild-type Cas12a and SCas12a RNP was assessed using a standardized protocol34. To this end, a targeted dsDNA plasmid named P-HPV16 was created by integrating a PAM sequence and a 20-nt DNA fragment from HPV16 into a pcDNA3.1(+) vector with a total length of 5430 bp. The digestion was conducted using a 10 µL reaction mixture consisting of 1 µL 10 x NEB buffer 2.1, 50 nM Cas12a, 100 nM crRNA (or 100 nM split RNA), and 10 nM P-HPV16 plasmids, incubated at 37 oC for 30 min followed by termination of the reaction at 90 oC for 10 min. The cleaved DNA fragments were analyzed using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2a).

In the next, the trans-cleavage activity of wild-type Cas12a and SCas12a RNP was evaluated under the same reaction conditions described above, except for the utilization of a 20 nM concentration of 42-nt ssDNA reporter in the presence of either 10 nM 59-bp dsDNA targets (Fig. 2b) or 59-nt ssDNA targets (Fig. 2c). The resulting reaction products were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel using 1X TBE as the electrophoresis running buffer at a constant voltage of 100 V for 120 min. Finally, the gel was stained with GoldView and observed under a UV transilluminator for gel image acquisition.

Proof-of-principle studies of the SCas12a-based fluorescence assay

The cleavage reactions were performed in a final volume of 100 µL, comprising 10 µL of 10 x NEB buffer 2.1, 250 nM AsCas12a enzyme, 500 nM crRNA (or 500 nM split RNA), 500 nM target dsDNA (Supplementary Fig. 3a) or 500 nM target ssDNA (Supplementary Fig. 3b), and 1000 nM fluorescent probes. The reaction was conducted in a cuvette at 37 oC for 30 min, after which the fluorescence signal was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer F4600 (Hitachi, Japan). The excitation wavelength was set at 485 nm and emission wavelengths were recorded from 500 to 700 nm (Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition, the real-time fluorescence kinetics experiments (Fig. 3) were performed at the same conditions, except for the the fluorescence emission signals at 520 nM were recorded at 60 s intervals for 60 min using a CFX96 touch real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, CA, USA).

Application of SCas12a assay for RNA detection

Fluorescence-based detection assays were carried out using a CFX96 touch real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). The assembly of 250 nM Cas12a, 500 nM scaffold RNA, and 500 nM ssDNA activators involved mixing them in 1XNEB buffer 2.1 and nuclease-free water plus 1 mM L-proline, followed by a 10-minute incubation at room temperature. Subsequently, the mixtures were combined with 1000 nM FQ reporter and the appropriate concentration of target miRNA (pre-miRNA or long-sized RNA) in a 20 µL reaction volume. The reactions were carried out at 37 oC for 20 min, and the fluorescence changes at 520 nm were monitored. In addition, the LwaCas13a-based fluorescence assays were performed using identical reaction conditions, except that FAM-ssRNA reporter and LwaCas13a enzymes were used instead.

We have also performed lateral flow assays using the same reaction conditions, except for the utilization of a dipstick incorporating single-stranded DNA probes for cleavage. The LFA dipsticks sourced from GenDx (Suzhou, China) or ToloBio (Shanghai, China) employ the FAM-biotin reporter for immunochromatographic detection. In negative samples, the gold particle-biotin antibody binds efficiently to a high concentration of the FAM-biotin reporter and is captured by the anti-FAM antibody on the control strip. Conversely, in positive samples, the cleavage of the FAM-biotin reporter gene by active Cas12a results in the accumulation of the gold particle-biotin antibody conjugate on the test strip and a decrease on the control strip.

miRNA detection using human plasma samples

Total RNA was extracted from the human plasma samples using the RNAprep Pure Blood Kit from TIANGEN (Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted total RNA was diluted 5-fold before testing with the SCas12a assay. In the next, the RNA solution was mixed with the SCas12a assay reaction components in a 20 µL reaction volume, including 250 nM Cas12a, 500 nM scaffold RNA, 500 nM ssDNA activators and 1000 nM FQ reporter in 1XNEB buffer 2.1 and nuclease-free water plus 1 mM L-proline. The fluorescence signal was measured at 30-s intervals at 37 °C using a CFX96 touch real-time PCR system.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR for detection of miRNA

Total RNA was extracted from MCF-7 cancer cells by using the RNA extraction kit from GenePharma (Suzhou, China). Next, the cDNA was synthesized from the extracted total RNA using the miRCURY LNA RT Kit (Qiagen). Briefly, a reverse transcription reaction was performed at 42 °C for 60 min and then inactivated at 95 °C for 5 min. Synthesized cDNA was stored at −20 °C before use. For detection of specific miRNA targets, the stem-loop primers and Hairpin-it miRNA RT-qPCR detection kit were designed and ordered from GenePharma (Suzhou, China). Subsequently, the miR-21 targets in cells were quantitatively assessed according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer20. Specifically, a standard curve was developed to establish the correlation between miRNA concentration and Cq values obtained from RT-qPCR analysis. Next, the concentration of miR-21 in each cell samples was determined by referencing the standard curve generated from the RT-qPCR data. The real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) reactions were performed using a CFX96 touch real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and the miR-21 targets were identified utilizing the SYBR green fluorescent method. The thermal cycling conditions included an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 12 s and annealing/extension at 62 °C for 30 s.

Application of SCas12a assay for DNA detection

The direct detection of DNA targets was conducted using the SCas12a-based fluorescence assay or lateral flow assay, following a protocol similar to that outlined for RNA detection. The only difference was the utilization of spacer RNA activators in place of ssDNA activators. To enhance the sensitivity of detection, a RPA using TwistAmp Basic (TwistDx) was performed followed by SCas12a detection in the same reaction. Briefly, 40 µL reactions containing 1 µL sample, 0.4 µM forward and reverse primer, 1× rehydration buffer, 14 mM magnesium acetate and RPA mix were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, the RPA reaction was transferred to a PCR tube containing 250 nM Cas12a, 500 nM scaffold RNA, 500 nM spacer RNA, and 1000 nM FQ ssDNA reporter in a 20 µL reaction volume. The reactions were then carried out at 37 oC for 20 min, with fluorescence changes at 520 nm being recorded. In addition, one-pot reactions were also conducted in 30 µL reaction volumes comprising 250 nM Cas12a, 500 nM scaffold RNA, 500 nM spacer RNA, and 1000 nM FQ ssDNA reporter, dsDNA substrates, and RPA components. The assay was monitored using fluorescence or by LFA detection (GenDx Cas12a detection kit, Suzhou, China).

To identify HPV in clinical samples, a crude DNA preparation was conducted by pelleting 1.5 mL of the cell suspension. The resulting pellet was dried and then re-suspended in 100 µL of Tris-EDTA containing proteinase K at a concentration of 200 µg/mL. This mixture was incubated at 56 oC for 1 h, followed by heat inactivation of the proteinase K. Subsequently, 5 µL of this preparation was utilized in the HPV consensus PCR. In the SCas12a fluorescence assay, the detection values of HPV16 in human samples were normalized against the maximum mean fluorescence signal obtained using spacer RNA targeting the hypervariable loop V of the L13,35. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s post-hoc test was employed to establish the significance level (p ≤ 0.05) for the detection of HPV16 in patient specimens. Utilizing this threshold, all samples exhibited accurate identification of HPV16 infection, with a 100% agreement rate (25/25) when compared to PCR-based outcomes.

Limit of detection calculation

The limit of detection (LoD) was determined by conducting the trans-cleavage assay using various dilutions of RNA or DNA targets. The value of LOD was calculated by using formula 3σ/slope, where σ is the standard deviation of three blank solutions.

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kubista, M. et al. The real-time polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Aspects. Med. 27, 95–125 (2006).

Miller, J. R. & Andre, R. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 75, C188–C192 (2014).

Chen, J. S. et al. CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science 360, 436–439 (2018).

Li, S. Y. et al. CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted nucleic acid detection. Cell. Discov. 4, 20 (2018).

Li, L. et al. HOLMESv2: A CRISPR-Cas12b-Assisted Platform for Nucleic Acid Detection and DNA Methylation Quantitation. ACS. Synth. Biol. 8, 2228–2237 (2019).

Gootenberg, J. S. et al. Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science 356, 438–442 (2017).

Harrington, L. B. et al. Programmed DNA destruction by miniature CRISPR-Cas14 enzymes. Science 362, 839–842 (2018).

Kaminski, M. M., Abudayyeh, O. O., Gootenberg, J. S., Zhang, F. & Collins, J. J. CRISPR-based diagnostics. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 643–656 (2021).

Weng, Z. et al. CRISPR-Cas Biochemistry and CRISPR-Based Molecular Diagnostics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 62, e202214987 (2023).

Zetsche, B. et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 163, 759–771 (2015).

Broughton, J. P. et al. CRISPR-Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Biotech. 38, 870–874 (2020).

Feng, W. et al. Integrating Reverse Transcription Recombinase Polymerase Amplification with CRISPR Technology for the One-Tube Assay of RNA. Anal. Chem. 93, 12808–12816 (2021).

Zhang, W. S. et al. Reverse Transcription Recombinase Polymerase Amplification Coupled with CRISPR-Cas12a for Facile and Highly Sensitive Colorimetric SARS-CoV-2 Detection. Anal. Chem. 93, 4126–4133 (2021).

Yan, H. et al. A one-pot isothermal Cas12-based assay for the sensitive detection of microRNAs. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 1583–1601 (2023).

Gootenberg, J. S. et al. Multiplexed and portable nucleic acid detection platform with Cas13, Cas12a, and Csm6. Science 360, 439–444 (2018).

Kellner, M. J., Koob, J. G., Gootenberg, J. S., Abudayyeh, O. O. & Zhang, F. SHERLOCK: nucleic acid detection with CRISPR nucleases. Nat. Protoc. 14, 2986–3012 (2019).

Huyke, D. A. et al. Enzyme Kinetics and Detector Sensitivity Determine Limits of Detection of Amplification-Free CRISPR-Cas12 and CRISPR-Cas13 Diagnostics. Anal. Chem. 94, 9826–9834 (2022).

Fozouni, P. et al. Amplification-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 with CRISPR-Cas13a and mobile phone microscopy. Cell 184, 323–333.e329 (2021).

Rananaware, S. R. et al. Programmable RNA detection with CRISPR-Cas12a. Nat. Commun. 14, 5409 (2023).

Qiao, J., Lin, S., Sun, W., Ma, L. & Liu, Y. A method for the quantitative detection of Cas12a ribonucleoproteins. Chem. Commun. 56, 12616–12619 (2020).

Moon, J. & Liu, C. Asymmetric CRISPR enabling cascade signal amplification for nucleic acid detection by competitive crRNA. Nat. Commun. 14, 7504 (2023).

Shebanova, R. et al. Efficient target cleavage by Type V Cas12a effectors programmed with split CRISPR RNA. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 50, 1162–1173 (2022).

Zhao, S. et al. Selective In Situ Analysis of Mature microRNAs in Extracellular Vesicles Using a DNA Cage-Based Thermophoretic Assay. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303121 (2023).

Fu, X. Y. et al. Size-selective molecular recognition based on a confined DNA molecular sieve using cavity-tunable framework nucleic acids. Nat. Commun. 11, 1518–1529 (2020).

Nguyen, L. T. et al. Harnessing noncanonical crRNAs to improve functionality of Cas12a orthologs. Cell. Rep. 43, 113777–113795 (2024).

Shigeyasu, K., Toden, S., Zumwalt, T. J., Okugawa, Y. & Goel, A. Emerging Role of MicroRNAs as Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Clin. Cancer. Res. 23, 2391–2399 (2017).

Zamani, S., Hosseini, S. M. & Sohrabi, A. miR-21 and miR29-a: Potential Molecular Biomarkers for HPV Genotypes and Cervical Cancer Detection. MicroRNA 9, 271–275 (2020).

Li, J., Macdonald, J., von & Stetten, F. Review: a comprehensive summary of a decade development of the recombinase polymerase amplification. Analyst 144, 31–67 (2018).

Tan, M. et al. Recent advances in recombinase polymerase amplification: Principle, advantages, disadvantages and applications. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 1019071–1019084 (2022).

Yigci, D., Atçeken, N., Yetisen, A. K. & Tasoglu, S. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification-Integrated CRISPR Methods for Infectious Disease Diagnosis at Point of Care. ACS omega 8, 43357–43373 (2023).

Yüce, M., Filiztekin, E. & Özkaya, K. G. COVID-19 diagnosis-A review of current methods. Biosens. Bio8eletron. 172, 112752 (2021).

Xu, Z. C. et al. Microfluidic space coding for multiplexed nucleicaciddetectionviaCRISPR-Cas12aand recombinase polymerase amplification. Nat. Commun. 3, 6480–6494 (2022).

Deng, F. et al. Topological barrier to Cas12a activation by circular DNA nanostructures facilitates autocatalysis and transforms DNA/RNA sensing. Nat. Commun. 15, 1818–1834 (2024).

Qiao, J. et al. Co-expression of Cas9 and single-guided RNAs in Escherichia coli streamlines production of Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Commun. Biol. 2, 161–167 (2019).

Woodman, C. B., Collins, S. I. & Young, L. S. The natural history of cervical HPV infection: unresolved issues. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 7, 11–22 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China 2022YFC2304304 (Y.L.), Science and Technology Innovation Talent Plan of Hubei Province 2023DJC136 (Y.L.), the Open Funding Project of the State Key Laboratory of Esophageal Cancer Prevention K2022-008 (J.Q.), the Open Funding Project of the State Key Laboratory of Biocatalysis and Enzyme Engineering SKLBEE2022022 (J.Q.), Research Funding of Wuhan Polytechnic University NO.2022RZ031 (J.Q.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Q., Y.C., and Y.L. designed research; J.Q., Y.C., X.W., J.Z., Q.J., and W.Y. performed research; B.H. collected the patient samples; Y.C., J.Z., Q.J., and Y.L. analyzed data; and Y.L. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.L. is a professor of bioscience at Hubei university, and a scientific advisor to BravoVax. The regents of Wuhan Polytechnic University and BravoVax have two patents (application number 2023106008815.7 and 202310602086.4) pending for CRISPR-Cas12a detection technologies on which professor Y.L. and J.Q. are inventors. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Qingshan Wei, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, J. et al. Split crRNA with CRISPR-Cas12a enabling highly sensitive and multiplexed detection of RNA and DNA. Nat Commun 15, 8342 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52691-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52691-x

This article is cited by

-

Portable biosensor for quantitative detection of meat adulteration based on heparin sodium-mediated one-tube RPA/SCas12a amplification strategy

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2026)

-

A multifunctional approach: merging CRISPR/Cas technology with DNA nanomachines for advanced biosensing

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2026)

-

Tailoring Cas12a functionality with a user-friendly and versatile crRNA variant toolbox

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Precise amplification-free detection of highly structured RNA with an enhanced SCas12a assay

Communications Biology (2025)

-

Regulating cleavage activity and enabling microRNA detection with split sgRNA in Cas12b

Nature Communications (2025)