Abstract

Bacteriophage (phage) therapy is a promising therapeutic modality for multidrug-resistant bacterial infections, but its application is mainly limited to personalized therapy due to the narrow host range of individual phages. While phage cocktails targeting all possible bacterial receptors could theoretically confer broad coverage, the extensive diversity of bacteria and the complexity of phage-phage interactions render this approach challenging. Here, using screening protocols for identifying “complementarity groups” of phages using non-redundant receptors, we generate effective, broad-range phage cocktails that prevent the emergence of bacterial resistance. We also discover characteristic interactions between phage complementarity groups and particular antibiotic classes, facilitating the prediction of phage-antibiotic as well as phage-phage interactions. Using this strategy, we create three phage-antibiotic cocktails, each demonstrating efficacy against ≥96% of 153 Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates, including biofilm cultures, and demonstrate comparable efficacy in an in vivo wound infection model. We similarly develop effective Staphylococcus aureus phage-antibiotic cocktails and demonstrate their utility of combined cocktails against polymicrobial (mixed P. aeruginosa/S. aureus) cultures, highlighting the broad applicability of this approach. These studies establish a blueprint for the development of effective, broad-spectrum phage-antibiotic cocktails, paving the way for off-the-shelf phage-based therapeutics to combat multidrug-resistant bacterial infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens has created an urgent need for the development of novel therapeutic approaches to treat these bacterial infections1. Bacteriophages (phages), viruses that kill bacteria, have garnered significant interest as potential alternatives or supplements to conventional antibiotics2. Indeed, phage therapy is already saving individual lives in the setting of compassionate use cases3,4,5,6,7. However, successful clinical trials with widely effective phages have been elusive8,9,10, limiting the therapeutic and commercial potential of this approach.

One significant obstacle in the development of effective phage therapy is the narrow host range exhibited by many individual phages. Although the level of specificity can vary, phages typically infect one particular host bacterial species and a limited subset of strains (i.e., strains being variants within a single species). Bacterial receptors are implicated as major determinants of phage host range11, but the receptors for most phages remain undetermined. Identifying phages with adequate coverage is particularly challenging in the setting of polymicrobial (involving multiple microbial species) and polyclonal (involving multiple bacterial strains) infections. For example, chronic wound infections in diabetic ulcers and chronic lung infections in cystic fibrosis often involve polyclonal infections with numerous distinct, MDR strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa12 and polymicrobial infections involving both P. aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus13. Identifying phages capable of targeting all of these complex niches remains an unsolved problem.

Another barrier is the development of phage resistance by host bacteria14. Bacteria employ diverse defense mechanisms to evade predation by phages, including receptor modification, restriction-modification systems, and other defense strategies15,16. These phage defense mechanisms are frequently triggered in response to phage predation, often resulting in bacterial growth after initial inhibition17, and may contribute to both individual and community-level protection18,19. However, the relative importance of these resistance mechanisms is unclear, necessitating laborious and time-consuming screening protocols to identify effective phages for each bacterial isolate20.

“Cocktails” that combine multiple phages are an appealing solution to the problems of limited host range and the emergence of resistance21,22. However, phage-phage interactions can either be synergistic23 or antagonistic24 and are challenging to predict. Moreover, the optimum number of phages, and whether they ought to be administered serially or in concert remain unclear. Further complicating the development of cocktail approaches is the lack of robust technical protocols, analytical frameworks, and appropriate pre-clinical models to effectively interrogate phage-phage and phage-antibiotic combinations. In the absence of clear guiding principles and effective protocols to inform cocktail design, phage cocktails are typically selected empirically25,26. Combining phages with antibiotics is similarly challenging, as phage-antibiotic interactions are also difficult to predict27,28,29.

There are several competing models for phage cocktail design30,31, but each faces challenges in generalized implementation. One approach is to use genomic or strain-based algorithms to guide cocktail composition21,32. Another strategy involves experimentally matching phages to all of the individual bacteria in a population, which has shown promise when dealing with a limited number of strains33,34,35. However, scaling up this approach to encompass the vast diversity of bacteria in clinical settings is challenging. Bacterial receptors are an important factor in determining phage host range in designing phage cocktails21,36, and theoretically creating cocktails targeting all possible bacterial receptor specificities could provide broad coverage. Indeed, cocktails containing phages using different receptors have been explored35,37,38, establishing the conceptual foundation for this approach. However, these studies have typically been limited to a few strains and have not consistently achieved bacterial eradication. Ultimately, current phage cocktail designs have shown limited success in clinical trials8,29, and the field has struggled to move beyond personalized phage therapy.

Here, we hypothesized that identifying “complementarity” groups of phages using non-redundant receptors and correlating this approach with antibiotic pairing could be the key to generating effective phage-antibiotic cocktails for broad use. To test this idea, we developed an integrated series of assays and analytical approaches to facilitate cocktail selection. These efforts focused on two major pathogens commonly associated with devastating MDR infections39,40: P. aeruginosa, a Gram-negative bacterium, and S. aureus, a Gram-positive bacterium.

Results

Repeated exposure to phages promotes the selection for heritable, high-level resistance in bacteria

To study phage host range, we employed a spectrophotometer to provide a robust, quantitative measurement of bacterial growth of P. aeruginosa strain PA14 by recording the optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600) over time41. Then, we introduced the phage DMS3vir (a phage strain modified to be virulent42) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b, c) and assessed its impact on PA14 growth over a 30-hour period. This time window was selected because PA14 reaches a growth peak and is susceptible to phage predation.

To quantify phage susceptibility from these growth measurements43, we calculated what we termed as the “Suppression Index”– the percentage of growth inhibition caused by lytic phage within the first 30 hours of exposure (Fig. 1a). Initially, bacterial growth is inhibited due to the predation by DMS3vir. However, after 15 hours PA14 shows “growth”, indicating a fraction of phage-exposed bacterial population has developed resistance (Fig. 1b). Comparable results were obtained regardless of the MOI used, despite the initial, sub-maximal growth inhibition effects observed at lower MOIs (Fig. 1c). To maximize susceptibility to phages, we used an MOI of 100 throughout this work, unless indicated otherwise. Analogous results were obtained across a panel of eight different phages (Fig. 1d), which were previously used in preclinical and clinical phage studies24,44,45,46.

a To quantify phage-mediated suppression of bacterial growth, we measured growth curves over a 30-hour period and calculated the “Suppression Index,” defined as the area under the curve (AUC) for the non-phage-treated condition minus the phage-treated condition divided by the AUC for the non-treated condition. Growth curves (b) and Suppression Index (c) for P. aeruginosa strain PA14 under different multiplicity of infection (MOI) of DMS3vir phage. d Suppression Index for PA14 exposed to eight different phages, each at an MOI of 100. Representative plaque assays from three independent experiments are shown above each column. e To quantify resistance upon repeat phage exposure, we collected bacteria following an initial phage exposure (1st exposure) and then re-cultured these bacteria in the absence or presence of the identical phage (2nd exposure). Upon this second exposure, we again generated growth curves over 15 h and determined the “Resistance Index,” defined as the AUC of the phage-rechallenged condition divided by the AUC of the non-rechallenged condition. Growth curves (f) for PA14 after initial exposure to DMS3vir at an MOI of 100 (1st exposure) followed by subsequent exposure to either DMS3vir at an MOI of 100 (2nd exposure, dark blue) or Buffer control (light blue) and the resulting Resistance Index (g). h Resistance Index for PA14 challenged initially with one of eight different phages (1st exposure) and subsequently re-challenged with the same phage (2nd exposure). Representative plaque assays from three independent experiments are shown above each column. The bacteria and phage features depicted on the right side of a and e were created in BioRender. Kim, K. (2023) BioRender.com/z47k977. All reported values for b–d, f, g, and h are depicted from three independent experiments with n = 3 and associated error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. Statistical significance in c is derived from One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and significance levels include *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Subsequently, we then re-exposed these same bacterial cultures a second time to the same phages (Fig. 1e). Notably, we observed the occasional emergence of PA14 variants with a complete loss of susceptibility to the phage (Fig. 1f). Following the initial phage exposure, this loss of susceptibility was constitutive.

To quantify this phage resistance upon repeated exposure, we calculated what we call the “Resistance Index” – the percentage of growth observed over 15 hours upon phage re-challenge in a previously phage-exposed strain (Fig. 1e). For example, we observed more than 90% bacterial growth (or 90.1% Resistance Index), when re-exposed to 100 MOI of DMS3vir in the previously DMS3vir-exposed strain (Fig. 1f, g), indicating that the previously DMS3vir-exposed strain had developed near-complete resistance to DMS3vir. Similar results were obtained across a panel of eight different phages (Fig. 1h).

Constitutive phage resistance confers cross-resistance against “complementarity groups” (CGs) of genetically diverse phage species

To investigate how constitutive phage resistance, induced by repeated exposure to a single phage, affects susceptibility to other phages, we “rechallenged” each phage-exposed PA14 strain by all eight phages and assessed the individual Resistance Indexes. We observed that bacteria that lost susceptibility to each of the three phages DMS3vir, TIVP-H6, and Luz24 also lost susceptibility to all three phages in this group. Similarly, bacteria that lost susceptibility to either 14-1 or PhiKZ lost susceptibility to both (Fig. 2a). This cross-resistance within a group of phages indicated a shift in host susceptibility against a collection of phages.

a The Resistance Index of PA14 initially exposed to one of a set of eight phages and then subsequently re-exposed to each of the same set of eight phages, all at an MOI of 100. All reported values are depicted from three independent experiments with n = 3 and associated error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. b Phage exposure matrix representing the average value of the Resistance Index data presented in a. These data highlight the presence of multiple groups of phages wherein constitutive resistance to one confers PA14 cross-resistance against other phages within that group. In this context, CGs are defined as groups of phages that can have cross-constitutive resistance to one another within that group. c Principal component analysis (PCA) of the data presented in the matrix description of b. d Phylogenic dendrogram for the phages in a, b. The scale (A.U.) is represented as relative evolutionary distance (substitution/site), providing a measure of the genetic relatedness among the phages. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Using these cross-resistance patterns, we generated a phage exposure matrix (Fig. 2b). We observed that phages clustered within four major groups, which we termed “complementarity groups” or CGs. These phage CG patterns are further supported by principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig. 2c), which shows the phages with the same CG clustered with one another. Notably, phage Luz24 belongs to two CGs, indicating that dual identity is possible. Analogous CG results were observed using P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b), suggesting that phage CG structures are generalizable across P. aeruginosa strains.

To investigate whether the resistance matrix chart could be expanded to include previously uncharacterized phages, we isolated a pair of novel P. aeruginosa phages, KOR_P1 and KOR_P2, from local sewage (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d). The newly identified phages could likewise be linked to phage susceptibility groups based on cross-resistance patterns (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Upon screening and analysis, we observed that both KOR_P1 and KOR_P2 grouped with the CG of DMS3vir (Supplementary Fig. 2f), suggesting that the CG framework is expandable.

We also questioned whether CG patterns might be correlated with the evolutionary relationships among these phage species11. To test this, we generated a phylogenetic tree based on phage genome sequences. We observed that the phylogenetic grouping did not entirely align with the CG patterns (Fig. 2d), indicating that the determinants of CG may not necessarily be evolutionarily fixed nor mediated by convergence evolution, presumably due to the mosaicism nature of phage genomes47.

Phages belonging to the same CG use the same bacterial receptors

We hypothesized that phages belonging to the same CG share the same bacterial receptors, such that loss of susceptibility to one phage confers loss of susceptibility to all phages within the group. In support of this model, phages are known to utilize common bacterial structures, including the Type IV pilus, the flagella, and oligosaccharide antigens/lipopolysaccharide (OSA/LPS)48,49,50,51, as receptors for entry to their hosts (Fig. 3a).

a Schematic model description of three major surface receptors involved in phage uptake by P. aeruginosa, including Type IV pili (pink), oligosaccharides antigens (OSA) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS, blue), and flagella (green). This schematic model was created in BioRender. Kim, K. (2023) BioRender.com/q97t970. b Representative images of twitching motility assay by PA14, PA14ΔpilA, and PA14 strains exposed to DMS3vir, TIVP-H6, Luz24, and OMKO1 phages. Scale bar = 10 mm. c Suppression Index measured for PA14 (black) and the PA14ΔpilA (pink) by eight different types of phages, each at an MOI of 100. d Colony biofilm phenotypes of PA14, PA14ΔwapR, and the designated phage-exposed strains on Congo red agar medium after 100 hours of growth. Scale bar = 2 mm. e Suppression Index measured for the wild-type PA14 (black) and PA14ΔwapR (blue) by eight different types of phages at an MOI of 100. f Representative images of swimming motility assay by PA14, PA14ΔfliC, and PA14 strains exposed to DMS3vir, TIVP-H6, Luz24, and OMKO1 phages. Scale bars = 10 mm. g Suppression Index measured for PA14 (black) and PA14ΔfliC (green) by eight different types of phages, each at an MOI of 100. Images shown in b, d, and f are based on a minimum of triplicate independent replicates. All reported values for c, e, and g are depicted from three independent experiments with n = 3 and associated error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. Statistical significance in c, e, and g is derived from Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and significance levels include *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To investigate this idea, we examined whether resistance to a particular phage CG could result in a phenotype consistent with the loss of a functional receptor. We found that PA14 that lost susceptibility to either DMS3vir, TIVP-H6, or Luz24 phage CG no longer exhibited twitching motility, a characteristic mediated by the Type IV pilus, and resembled a Type IV pilus mutant strain (PA14ΔpilA) (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Further supporting this notion, we found that the phages in this CG require an intact Type IV pilus to infect PA14 (Fig. 3c). We obtained identical results—reduced infection by the DMS3vir, TIVP-H6, and Luz24 phages—with six different mutant strains defective in various components of the type IV pilus, including PA14ΔpilA, PA14ΔpilB, PA14ΔpilC, PA14ΔpilW, PA14ΔpilX, and PA14ΔpilY1, suggesting that DMS3vir, TIVP-H6, and Luz24 requires an intact Type IV pilus to infect PA14 (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Of note, DMS3vir, TIVP-H6, and Luz24 phages are still able to partially infect the PA14ΔpilTU mutant that has an intact Type IV pilus structure but has defective retraction motor proteins52, indicating that these phages did not need a fully functional exterior Type IV pilus structure to infect their targets. Mutations in Type IV pilus genes were identified in those phage-resistant PA14 strains (Supplementary Table 1), further supporting the role of the Type IV pilus in infection by phages in this CG and indicating that phage resistance is mediated by mutations in the genes encoding for Type IV pilus.

Similarly, PA14 strains that had lost susceptibility to either LMA2 or PAML-31-1 exhibited a loss of rugae in the center of a colony biofilm, a phenotype associated with oligosaccharide antigen (OSA)-containing LPS, and resembled an OSA/LPS mutant strain of PA14 (PA14∆wapR) (Fig. 3d; Supplementary Fig. 3d). The phenotypic changes were supported by a shift of OSA/LPS size (Supplementary Fig. 3e). Consistent with this finding, these phages require an intact OSA/LPS to infect PA14 (Fig. 3e). Phage-resistant PA14 strains (resistant to either LMA2 or PAML-31-1) harbored mutations in genes regulating the synthesis of OSA/LPS (Supplementary Table 1), indicating that the loss of PA14 susceptibility to infection by phages in this CG is mediated by mutations in the genes governing OSA/LPS synthesis.

The PA14 strain that lost susceptibility to the phage OMKO1 exhibited diminished swimming motility and resembled a strain of PA14 bearing mutant flagella (PA14∆fliC) (Fig. 3f; Supplementary Fig. 3f, g). OMKO1 requires intact flagella to infect PA14, as evidenced by the phage’s inability to infect mutant strains defective in different components of the flagella structure, FliC (PA14∆fliC) and FlgK (PA14∆flgK) (Fig. 3g; Supplementary Fig. 3h). Of note, OMKO1 phage is also unable to infect the PA14ΔoprM mutant that has a defective outer membrane protein for antibiotic efflux53 (Supplementary Fig. 3i), indicating that both intact flagella and OprM are required for OMKO1 to infect PA14. The OMKO1-resistant PA14 strain exhibited mutations in flagellar genes (Supplementary Table 1), indicating that OMKO1 resistance in this CG is mediated by these mutations.

We also investigated what receptor-related phenotype changes are involved in PA14 with resistance to phages PhiKZ and 14-1. However, while possible receptors for these phages have been suggested54,55,56, an obvious receptor-related phenotype was not identified in this present work.

We were intrigued to note that some phages may belong to multiple complementarity groups. For example, phage Luz24 requires the Type IV pilus for infectivity of PA14 (Fig. 3b, c), but also shares cross-resistance patterns with phages PhiKZ and 14-1 (Fig. 2a, b). Consistent with this result, this Luz24 phage has been reported previously to utilize either a cell surface structure54 and/or Type IV pilus as its entry receptors.

Together, these findings demonstrate that a loss of susceptibility to a CG of phages is associated with loss or changes in expression of the entry receptor, conferring cross-resistance against the entire group of phages that utilize that receptor(s). This idea is further supported by the observation that the two newly identified phages (KOR_P1 and KOR_P2), which we found belong to the same CG as DMS3vir (Supplementary Fig. 2e, f), also rely on the Type IV pilus for phage entry, as seen in studies with the PA14ΔpilA strain (Supplementary Fig. 3j). These data demonstrate that information on CG identity can help predict the receptor(s) used by previously uncharacterized phages.

Cocktails containing phages from multiple CGs reliably eliminate multi-drug resistant clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa, including biofilm and polyclonal cultures

By utilizing the CGs information, we next create cocktails incorporating multiple phages. To this end, we sought to determine how many phages are optimal and whether combinations of phages from the same or different CGs were equally effective. Comparing one phage versus two phages from the same CG, two phages from different CGs, or three phages from different CGs, we observed that while treatment with one or two phages from the same CG could only initially suppress bacterial growth, treatment with two or three phages from different CGs more completely eliminated the growth within the 30-hour time frame examined here (Fig. 4a). Pooled Suppression Index data for PA14 treated with various phage cocktails, each using a different combination of phages (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Table 2), showed that two or more phages from different CGs can suppress bacterial growth by over 90%.

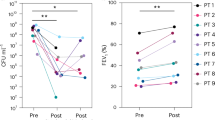

a Growth curves for PA14 treated with phage(s) from DMS3vir, the same CG (DMS3vir + TIVP-H6), two different CGs (DMS3vir + OMKO1), or three different CGs (Luz24 + OMKO1 + PAML-31-1). Notably, the treatment with three phages from different CGs completely prevented growth (highlighted in yellow). All reported values are depicted from three independent experiments (n = 3) and associated error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. b Pooled Suppression Index data for PA14 treated with different phage cocktails; each data point represents as the average Suppression Index value of three independent experiments from a different combination of phages, with the number of phages and number of CGs as indicated. These cocktails are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The error bars represent standard deviation from the mean of pooled Suppression Index data. c Pooled Resistance Index for PA14 treated initially with different phage cocktails and subsequently re-challenged by each component phage that comprises the cocktails, all at an MOI of 100; each data point represents as the average Resistance Index value of three independent experiments. Detailed information on the phages used is in Supplementary Table 2. The error bars represent standard deviation from the mean of pooled Resistance Index data. d Representative three-dimensional renderings of PA14 biofilms after 72 hours in the absence or presence of phage therapy, as indicated. e Pooled data for PA14 cells in biofilms treated with different phage cocktails; each data point represents as the average cell number of three independent experiments. The error bars represent standard deviation from the mean of pooled biofilm data. f Suppression Index for 16 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa by individual phages Luz24, OMKO1, and PAML-31-1, each at an MOI of 100, or a cocktail of these three phages (KIM-C1) with a combined MOI of 100. g, Suppression Index for these clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa by cocktail KIM-C1 at combined MOIs of 1, 100, or 500. Data in f and g are shown as an average of triplicate independent results. h Suppression Index for monoclonal and polyclonal P. aeruginosa cultures treated individually with KIM-C1 cocktail, its three constituent phages, or KIM-M1 mocktail (a mixture of 3 phages with same CG: DMS3vir, KOR_P1, and KOR_P2) grown in planktonic form or as biofilms. Data are shown as an average of triplicate independent results. The phage dose used here is a combined MOI of 100. i A schematic for wound mice model. This schematic model was created in BioRender. Kim, K. (2023) BioRender.com/s43l916. j Representative wound images of each condition (control, cocktail, and mocktail) over the course of experiments. k CFU of the polyclonal cultures in wounds under the conditions in j. The red line indicates the average value of each condition from at least 15 independent experiments. The black dotted line with “LOD” denotes the limit of detection, which is 100 CFU/g (log(100) = 2). The data under LOD indicates LOD/2 (50 CFU/g or log(50) = 1.7). Statistical significance in b, c, e, and k is derived from One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and significance levels include *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We then examined the development of constitutive resistance to phages upon repeated exposure to these four conditions. The pooled Resistance Index data for PA14 treated with various phage cocktails showed that three or more phages from different CGs most effectively suppressed resistance (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Table 2).

Similarly, we found that three phages from different CGs were the most effective against biofilm cultures, as measured by confocal microscopy57 (Fig. 4d, e). Together, these data demonstrated the superiority of combining three phages from different CGs in regard to suppressing growth without the development of resistance.

Notably, few cells isolated after being challenged by three phages from different CGs exhibited significant growth defect as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a, with multiple mutations in genes governing cell metabolism (e.g., dnaB, dnaX, ftsZ, hrpB, phaC, pchF, and nuoF), without any mutation in genes responsible for phage receptor synthesis. We interpret these data to suggest that the few isolated cells are able to persist in the presence of multiple lytic phages via altered metabolism, which in turn can also negatively impact phage replication in the host cell. These isolated bacteria with major growth defects may be clinically insignificant, as they rarely can grow upon secondary exposure to the identical three phages from different CGs (Supplementary Fig. 4a).

We next asked whether phages should be given in sequence or in concert. To this end, we compared sequential monotherapy versus consecutive dual therapy, as per the schematic in Supplementary Fig. 4b. We observed that phages delivered “in combination” suppressed bacteria growth over time with less resistance, as opposed to the phages delivered “in series” (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Analogous results were obtained using other combinations of phages with different CGs (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e), suggesting that this is a general feature of phage CG cocktails. Together, these data indicate that phage cocktails administered in concert are superior to those given in sequence, as consistent with a previous report24.

We then examined the impact of phage cocktails incorporating multiple CGs on de-identified clinical P. aeruginosa isolates collected at Stanford University Medical Center. We observed that individual phages Luz24, OMKO1, and PAML-31-1 were sporadically effective at suppressing the growth of 16 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. In contrast, a cocktail of these three phages (which we call “KIM-C1”) was more reliably effective (Fig. 4f), without showing inferiority in the Suppression Index compared to any single constituent phage. This suggests that there is no significant interference between each phage. Of note, we chose this particular three-phage combination because it covers all four different CGs, indicating that they target different receptors and are thus more compatible with each other, reducing the risk of interference. We also noticed that the effectiveness of KIM-C1 is also dose-dependent (Fig. 4g). These results indicate that the KIM-C1 phage cocktail can effectively target clinical isolates.

To explore the effectiveness of this approach in microbially complex bacterial niches, such as might be found in a polyclonal infection12, we simultaneously grew three P. aeruginosa strains (PA14-mCherry, PAO1-GFP, and a clinical isolate of CPA050) and then confirmed that they have comparable growth rates each other and they do not interfere each other’s growth by tracking their labels (Supplementary Fig. 4f, g). Subsequently, we treated this polyclonal culture with either individual phages or the KIM-C1 cocktail that covers four CGs. As a control, a “mocktail” (KIM-M1) of three phages mixture (DMS3vir, KOR_P1, and KOR_P2) from a single CG was used. While the individual strains are often susceptible to individual phages or the mocktail, the polyclonal culture was only eliminated by KIM-C1 (Fig. 4h). This was also true for the same bacteria grown under biofilm conditions (Fig. 4h; Supplementary Fig. 4h). These results indicate that polyclonal bacterial infections can be effectively targeted by a cocktail of phages from multiple CGs.

To investigate whether our in vitro findings are also applicable in an animal model of wound infection38,58, as shown with a schematic of this model (Fig. 4i), we mixed equal portions of three P. aeruginosa strains (PA14-mCherry, PAO1-GFP, and CPA050) and infected mice with the mixed culture 24 hours after a fresh wound was made (Fig. 4j). Then, each wound was treated twice (at 2 and 24 hours after bacterial infection) with either a cocktail (KIM-C1), a mocktail (KIM-M1), or a buffer as a control. At 72 hours after infection, we collected the wound and measured the remaining bacteria in each wound. We observed that the cocktail KIM-C1 was more consistently effective against the polyclonal culture, as compared to the mocktail or control (Fig. 4k). These results confirm that the phage cocktail, KIM-C1 can successfully treat polyclonal infections in vivo, mirroring the mechanisms of action observed in vitro and further suggesting its potential clinical applications.

Together, our findings demonstrate that combinations of three or more phages from different CGs are effective at suppressing the growth of clinical P. aeruginosa isolates in planktonic conditions, biofilms, polyclonal cultures, and in an in vivo animal model, highlighting the potential of this approach for the development and application of effective phage therapy strategies.

Phage CGs have predictable interactions with particular classes of conventional antibiotics

Given that antibiotics are known to impact phage lytic activity in both positive (synergistic) and negative (antagonistic) ways28,29,53,56,59, we next sought to determine whether phages from particular complementarity groups similarly have characteristic relationships with different conventional antibiotics. To investigate this, we used low levels of antibiotic (sub-MIC levels; MIC levels shown in Supplementary Table 3) to best study phage-antibiotic interactions. Growth curves from PA14 under the different sub-MICs of 12 antibiotics used in these experiments are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 5a. For phages, we used an MOI of 10 in these experiments. Then, we measured the bacterial growth over 30 hours in the presence of either a particular antibiotic, each phage, or both together (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c, d). The synergy score index was calculated as the phage-antibiotic interactions in each pair using the Highest Single Agent (HSA) Model, as detailed in the Methods section.

We observed that phages belonging to the same CGs generally share common patterns of interactions with conventional antibiotics (Fig. 5a, b). Some antibiotic classes were synergistic with most phages, such as the β-lactam drugs (e.g., ceftazidime (CTZ) and meropenem (MER)), while other antibiotic classes had idiosyncratic patterns of activity with phage CGs (e.g. ciprofloxacin (CIP), and doxycycline (DOX)). These data suggest that for some antibiotics, characteristic patterns of antibiotic responses exist for different phage CGs.

a Exposure matrix for PA14 exposed to combinations of phages and antibiotics simultaneously. Blue areas represent synergy, while red areas represent antagonism. The antibiotic concentrations were below their MIC values (sub-MIC) as detailed in the Supplementary Table 3. CTZ ceftazadime, AZT aztreonam, MER meropenem, GEN gentamicin, TOB tobramycin, AMI amikacin, DOX doxycycline, ERY erythromycin, CIP ciprofloxacin, TMP trimethoprim, COL colistin, and RIF rifampin. Data are shown in the matrix as an average of triplicate independent results. b PCA data for responses to phages and antibiotics. c Effectiveness Ratio (%) of 153 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates treated with the KIM-C1 cocktail (Luz24, OMKO1, and PAML-31-1), AZT treatment alone, or the KIM-C1 cocktail plus aztreonam (KIM-C1 + AZT) grown in planktonic form or as a biofilm. Effectiveness was defined as >60% growth suppression over 30 hours. d Effectiveness Ratio (%) of 153 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates treated with either one of three different phage cocktails (KIM-C1, -C2, and -C3), each containing three or four phages from all four different CGs, or a cocktail plus aztreonam. e Suppression Index for 153 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates treated with the KIM-C1 cocktail, AZT alone, or the KIM-C1 cocktail plus aztreonam (KIM-C1 + AZT) grown in planktonic form or as biofilms. Data are shown in the matrix as an average of triplicate independent results. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To investigate the impact of combining synergic antibiotics with the KIM-C1 cocktail (shown in Fig. 4f), we expanded our analysis to include 153 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates. We treated these with the cocktail KIM-C1, aztreonam (AZT), or a phage-antibiotic cocktail (KIM-C1 + AZT) and then measured the Suppression Index for each. We observed comparable rates of effectiveness regardless of whether >50, >60, or >70% suppression was used as the cut-off for effectiveness (Supplementary Fig. 5e). For subsequent analyses, >60% suppression was used as the cut-off for effective therapy in these studies.

Among 153 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates, overall response rates were 81%, 39%, and 96% to the KIM-C1 cocktail, AZT, or the KIM-C1 + AZT phage cocktail/aztreonam respectively in planktonic conditions (Fig. 5c). 80% of isolates grown as biofilms were likewise suppressed by KIM-C1 + AZT (Fig. 5c). We then extended this approach to generate additional cocktails (KIM-C2 and KIM-C3) of other phages encompassing multiple CGs. We found that these likewise achieved ≥96% coverage (Fig. 5d). These data further demonstrate that the receptor-based complementarity grouping can inform the generation of effective phage-antibiotic cocktails with broad host range.

Notably, some clinical P. aeruginosa isolates were not responsive either to KIM-C1 or AZT individually but were suppressed by KIM-C1 + AZT (Fig. 5e). These data indicate that a cocktail incorporating phages from the different CGs plus a synergic antibiotic was broadly effective against both planktonic and biofilm cultures.

Together, these findings demonstrate that phage CGs may exhibit predictable interactions with particular classes of conventional antibiotics, with some antibiotic classes showing synergistic effects with most phage CGs and others displaying idiosyncratic patterns of activity with phage CGs. Combining phages from different CGs with synergistic antibiotics resulted in broadly effective cocktails against both planktonic and biofilm cultures of clinical P. aeruginosa isolates. We highlight that the receptor-based CG approach could be a valuable tool in the development of effective phage-antibiotic cocktails with broad host range.

Phage-antibiotic combination therapy is effective against multi-drug resistant clinical S. aureus isolates and also effective for polymicrobial infections

To determine whether the approach of using phage CGs to design effective phage-antibiotic cocktails could be applicable to S. aureus, another MDR organism that often occurs in polymicrobial infections along with P. aeruginosa13, we examined a panel of five different S. aureus phages. For two of these (S. aureus bacteriophages K and Romulus), the receptors were known60,61,62 (Fig. 6a). We evaluated the Suppression Index for these phages against S. aureus strain 1203 (Fig. 6b, c). Following re-exposure to these same phages, we used the resulting Resistance Index data to generate the phage exposure matrix shown in Fig. 6d, which revealed that the phages targeting S. aureus fit into two major CGs. This pattern was further supported by principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig. 6e). As with our P. aeruginosa studies (Fig. 2d), the patterns of receptor usage did not always group with phylogenetic relationships (Fig. 6f). We also identified characteristic patterns of antibiotic responses that exist for different S. aureus phage CGs, with being vancomycin (VAN) synergistic and rifampin (RIF) being antagonistic against phages belonging to both CGs (Fig. 6g, h).

a Schematic model description of two major surface receptors involved in phage uptake by S. aureus. This schematic model was created in BioRender. Kim, K. (2023) BioRender.com/p71c092. b Growth curves for S. aureus strain 1203 following treatment with phage K. c Suppression Index for strain 1203 exposed to five different phages, each at an MOI of 100. All reported values in b and c are depicted from three independent experiments (n = 3) and associated error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. d Phage exposure matrix for strain 1203 initially exposed to one of five phages and then subsequently “re-exposed” to each of the same five phages, all at an MOI of 100. e PCA analysis, and f phylogenic dendrogram for these phages. g Synergic interaction matrix for 1203 exposed to combinations of phages and antibiotics simultaneously. VAN vancomycin 1.0 μg/ml, DOX doxycycline 0.05 μg/ml, ERY erythromycin 1.0 μg/ml, AMP ampicillin 0.1 μg/ml, TMP trimethoprim 1.0 μg/ml, RIF rifampin 0.03 μg/ml. h PCA data for the data in g. i Suppression Index for the individual phages vFB433, vFB009 (100 MOI each), a cocktail (KIM-C4) containing both phages (100 of combined MOIs), vancomycin (VAN), or and phage-antibiotic cocktail (KIM-C4 + VAN) grown in planktonic form or as biofilms. j Effectiveness Ratio (%) of 15 clinical S. aureus isolates to the treatments in i. k Suppression Index for monoclonal versus polyclonal S. aureus isolates cultures (CSA007, CSA009, CSA010) treated individually with a cocktail (KIM-C4) or its two constituent phages (vFB433, vFB009). l Suppression Index for polyclonal S. aureus (CSA007, CSA009, CSA010) or P. aeruginosa (CPA077, CPA086, CPA149) and m Suppression Index for polymicrobial S. aureus + P. aeruginosa isolates (all six strains) cultures treated individually with cocktails of phages with the different CGs or “mocktails” of phages sharing the same CG as controls. P. aeruginosa mocktail (KIM-M1) includes DMS3vir, KOR_P1, and KOR_P2. S. aureus mocktail (KIM-M2) includes vFB433 and vFB468. P. aeruginosa cocktail (KIM-C1) includes Luz24, PAML-31-1 and OMKO1. S. aureus cocktail (KIM-C4) includes vFB433 and vFB009. While the polyclonal S. aureus/P. aeruginosa isolates cultures include three clinical isolates each, the polymicrobial S. aureus and P. aeruginosa cultures include all six isolates. All data shown here are from triplicate independent results. The Suppression Index data in i, k, l, and m are shown as an average of triplicate independent results. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To assess the efficacy of CG-informed cocktails against S. aureus clinical isolates, we generated a cocktail called KIM-C4, which includes representatives of two different CGs using phages vFB433 and vFB009 and chose VAN as this antibiotic had widely synergistic interactions with all five phages in our set. We observed that while most of a set of 15 clinical S. aureus isolates were occasionally susceptible to either these individual phages or vancomycin when used alone, the phage-antibiotic combination (KIM-C4 + VAN) substantially increased these responses and had the broadest host range, including against biofilm cultures (Fig. 6i, j). Polyclonal S. aureus cultures also exhibited improved responses with the KIM-C4 cocktail (Fig. 6k).

Finally, we investigated whether phage cocktails designed using CG principles were effective against polymicrobial cultures. To assess this, we first grew either three different S. aureus or three different P. aeruginosa isolates each at a 1:1:1 ratio. These polyclonal cultures were subsequently treated with either “mocktails” of phages sharing the same CG or “cocktails” of phages with different CGs. We observed that each polyclonal culture was specifically responsive to the species-specific cocktail (Fig. 6l). Next, we mixed, with the same ratio, a total of six clinical isolates (three different S. aureus and three different P. aeruginosa isolates in equal proportions) and subsequently treated with either mocktails and/or cocktails of each species (Fig. 6m). We observed that polymicrobial cultures simultaneously treated with both KIM-C1 (a P. aeruginosa phage cocktail) and KIM-C4 (a S. aureus phage cocktail) were most effectively suppressed, compared to the other conditions. Notably, we did not observe any antagonism between phages of each species (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b), suggesting that our mixtures of multiple species-targeting phage cocktails can be used for complex, polymicrobial infections.

Together, these data demonstrate that phage cocktails developed using CG principles are effective against both polyclonal and polymicrobial cultures containing representative Gram-negative and Gram-positive MDR pathogens. The successful application of this approach to P. aeruginosa and S. aureus highlights the potential of CG-informed phage-antibiotic combination therapy as a broad-spectrum strategy for combating MDR bacterial infections.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that by combining phages from multiple, non-redundant receptor CGs, we can create highly effective, broad-spectrum phage cocktails. Using this approach, we develop multiple cocktails effective against large numbers of diverse clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, including biofilm cultures, and demonstrate high efficacy of the KIM-C1 cocktail in a wound infection animal model. Although we primarily used model strains for most mechanistic studies to demonstrate proof of principle, we show the potential of its clinical applications with a large set of clinical isolates.

In addition to broad host range, we report that cocktails including representative phages from multiple CGs can prevent the emergence of phage resistance, an important limitation of existing treatment protocols14,16. We propose that exposure to multiple phages that use different receptors may create orthogonal selection pressures on bacteria simultaneously. This may reduce the likelihood of resistance evolving to any phages, as has been shown for at least one phage-antibiotic pairing63. Similar to the use of multiple anti-retroviral therapies with different mechanisms of action against HIV64, the use of at least three complementary phages may effectively suppress bacterial growth and prevent mutations leading to resistance.

Interestingly, we observed that CG patterns were distinct from the phylogenetic relationships derived from whole-genome sequences of the same phages. While phylogenetic relationships for particular genes might reveal other patterns, these results suggest that phage receptor usage is evolutionarily fluid, presumably due to the mosaicism of phage genomes47. In addition, it is noteworthy that some phages rely on multiple receptors, in agreement with previous reports65. Our results also point to previously unsuspected receptor interactions for some well-characterized phages, such as OMKO153, which we find requires both OprM and the P. aeruginosa flagella for its infection. These findings suggest that phage-bacterial receptor interactions are likely dynamic and complex11,51, highlighting both the utility of a functional screening assay for phage-receptor interactions and the need for further study.

Particular phage CGs exhibit distinctive patterns with particular antibiotic classes, albeit having some degree of variations. For example, phages belonging to the Type IV pili CG are consistently synergistic with β-lactam antibiotics and aminoglycosides but have idiosyncratic interactions with most other antibiotic classes. This can be explained by the fact that antibiotics that inhibit cell wall biosynthesis (e.g., β-lactam) can cause bacterial filamentation, possibly making cells more susceptible to phage infection, leading to synergic interaction with phages66. On the other hand, some protein synthesis inhibitors can interfere with phage replication, which relies on bacterial protein synthesis machinery, resulting in antagonistic interaction with some phages67. Interestingly, we observed that phage-antibiotic interactions are also strain/species-dependent. For example, rifampin consistently exhibited synergistic interactions with our P. aeruginosa phages, while demonstrating antagonistic interactions with our S. aureus phages. This striking difference may be attributed to the distinct physiological characteristics of each organism and their unique interplay with rifampin. It is plausible that the antibiotic interferes with the phage replication cycle within S. aureus in a manner that is not observed in P. aeruginosa, leading to the observed antagonistic effects. Further investigation into the underlying molecular mechanisms and host-specific factors influencing these interactions could provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics of phage-antibiotic synergy and antagonism. While beyond the scope of this work, understanding the mechanisms underlying these patterns will be important for the future success of this approach. We envision that phage-antibiotic synograms28 could incorporate phage CG information to empower phage clinical treatment decisions, in the same way that physicians currently consult an antibiogram to inform treatment choices.

Of note, the concept of CGs is conceptually related to earlier idea of “cross-resistance modules” proposed by Wright et al.37. However, there are several key distinctions between the two approaches. Wright et al. primarily focused on studying phage cross-resistance and did not consider bacterial eradication as an endpoint (their analyses were limited to a 24-hour timeframe). Moreover, their definition of modules was based on genetic mutations, including transcriptional regulators, rather than receptors per se. Finally, this approach requires complex mutational analyses and a sophisticated algorithm, which may be challenging to directly translate into phage therapy cocktails. In contrast, our receptor complementarity grouping is defined solely by receptors and can be readily determined using a simple, quantitative method that is accessible to most academic laboratories and companies working in the field of phage therapy.

In addition to the conceptual advance of using phage cross-resistance to identify receptor CG and design effective cocktails, we also have introduced toolkits to facilitate this approach. This includes systems for quantifying phage suppression and resistance and a robust in vitro/in vivo model for evaluating cocktail activity, even against polymicrobial infections. While several of the elements presented in our work have antecedents in the previous literature28,68,69, their incorporation into an integrated system represents a step forward in the development of phage-antibiotic cocktails for these and other pathogens. We believe that our work provides a foundation for the continued exploration and optimization of phage-based therapies, contributing to the growing body of knowledge in this field.

It is important to note that while we have demonstrated that the primary defense mechanism against lytic phages in our study is through receptor loss or modification, several other defense systems specific to each species or strain were not considered in this study. These alternative defense mechanisms may have played a role in the observed outcomes. To enhance the effectiveness of our blueprint, future research should explore strategies for evading these additional phage defense systems and incorporate them into this blueprint framework.

Future studies may build on these findings in other ways. In particular, it may be possible to further expand the existing CG matrices reported here to include additional characterized or unknown phages. In addition, by expanding the CG matrices, we could generate additional phage cocktails against P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. We used P. aeruginosa and S. aureus for these studies because of the urgent medical need for new treatments against these deadly pathogens. However, it should be possible to generate phage cocktails against other Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens as well, using the same technique, analytic tools, and principles described here. It is worth noting that we observed a reduced effectiveness of phage cocktails within biofilms compared to the planktonic condition. This phenomenon is presumably due to the limited advection and diffusion of phages and antibiotic molecules within the biofilm matrix70,71. The potential of this therapeutic approach could be further extended by incorporating molecules that degrade biofilm matrix, such as dispersin B, glycoside hydrolase, or holins72. Our strategy further suggests the potential to be expanded to other systems like fungal infections using mycophages, a promising avenue for future research.

In conclusion, these studies establish a blueprint for the rational design of broad-spectrum phage-antibiotic cocktails that may overcome the serious medical problem of highly drug-resistant bacterial infections. We hope that the approaches developed here will enable future off-the-shelf phage-based therapeutics and thereby unlock the clinical and commercial potential of phage therapy.

Methods

Bacterial strains and overnight growth conditions

The strains used are listed in Supplementary Table 4. P. aeruginosa strain PA14 was used as a representative P. aeruginosa strain for most experiments shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 and their corresponding Supplementary Figs. unless stated otherwise. For experiments shown in Figs. 4, 5, and 6, clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa were used. For the experiment shown in Fig. 6, S. aureus strain 1203 was used as a representative S. aureus strain, and 15 clinical isolate strains of S. aureus were also used. For growth conditions, lysogeny broth (LB) was used as media and if applicable, appropriate antibiotics were added. LB agar contained LB with 18 g/L agar, and LB top agar included LB with 3.0 g/L agar, 50 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgSO4.

Collection of clinical P. aeruginosa and S. aureus isolates from patients

P. aeruginosa and S. aureus were isolated from various patient sources including sputum, BAL, sinus, and wounds in the Stanford Healthcare Clinical Microbiology Laboratory (SHCML), from June 2020 to May 2023. After 153 P. aeruginosa and 15 S. aureus clinical isolates were collected, all strains were de-identified. The clinical samples were cultured on routine media (blood, chocolate, MacConkey, and CNA agar). Pathogens were identified by MALDI-TOF (Bruker Biotyper). These isolates were given a unique identifier and stored at -80 °C in 40% glycerol until further use.

Bacterial growth curves for phage suppression assays

Cultures from frozen stocks were incubated at 250 rpm shaking at 37 °C overnight. Overnight cultures of bacterial strains were back-diluted 1:200, and re-grown for 2-3 hours (to OD600 ~ 0.1-0.2). Then, the re-grown culture was diluted 1:100 (OD600 ~ 0.001-0.002) into wells on a 96-well plate with LB to a total volume of 150 μL with pre-mixed phage (phage cocktails) to reach the target MOI. Depending on the experiment condition, an appropriate antibiotic was also added to each well to reach the target concentration. The final cultures on a 96-well plate were then incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 30 hours, and the OD600 curve was read every 20 min using an automated spectrophotometer (Biotek microplate reader) and the growth curves were obtained using the Gen5 software integrated with the BioTek plate reader. All the growth curves were subtracted from the background curve (LB media with phage buffer (1 mM MgSO4, 4 mM CaCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH=7.8, 6 g/L NaCl and 1 g/L gelatin)). Using the built-in GraphPad Prism Version 9.0 software package, the Suppression Index was calculated as the area under the curve (AUC) for the non-phage-treated condition minus the phage-treated condition divided by the AUC for the non-treated condition.

Bacterial growth curves for phage resistance assays

Phage-resistant isolates were obtained as follows. First, the strains after 30 hours of exposure to the 1st phage (or cocktails) were plated on the LB agar, where two colonies were randomly selected in the most dilute spots. Each picked colony was re-streaked onto sterile LB plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Each re-streaked isolate was picked and then suspended in sterile LB and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 250 rpm shaking. 500 μL samples of each bacterial culture were combined with 500 μL of sterile 60% glycerol solution and then frozen at −80 °C. These stocks were used for overnight cultures. The growth conditions were the same as described above in the suppression assay. The Resistance Index was calculated as the AUC of the phage-rechallenged condition divided by the AUC of the non-rechallenged condition after 15 hours.

Phage strains, purification, quantification, and plaque assay

The bacteriophages and their host strains for phage propagation are listed in Supplementary Table 5. For phage amplification, host bacteria strains at the mid-log phase were infected with stocks of phage and then cultured in 5 mL of LB top agar solution, which was subsequently poured into a sterile LB agar plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Phages were collected by adding 5 ml of phage buffer into the agar and collecting the top agar overlays. After collection of the top agar pieces into a 50 ml tube, any agar residuals were spun down by centrifuging them at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatants in the tube were collected and filtered via a 0.45 mm PES syringe. The collected phages were proceeded for further quantification. Phages were precipitated from the collected supernatant by adding 0.5 M NaCl and 4 % (w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 (Fisher Scientific, BP233-1) and then were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Phages were pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 20 min, and the pellet was then suspended in sterile TE (Tris, EDTA) buffer (pH 8.0). The suspension was centrifuged for 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was subjected to another round of PEG precipitation. The purified phage pellets were suspended in sterile PBS and dialyzed in 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off tubing (Fisher Scientific, UFC501096) against PBS, diluted to appropriate concentrations in sterile phage buffer, and filter-sterilized. For phage quantification, a phage titer in the filtered phage suspensions was determined as follows. Ten-fold serial dilutions of phage suspensions were prepared in phage buffer, ranging from 10–1 to 10–12. From each dilution, 10 μL was spotted on the host bacterial lawn on LB agar and incubated overnight at 37 °C. After incubation, plaques were counted at the spots at which the phage suspensions were added. The final PFU (plaque forming unit) was made based on the two independent counting. For plaque assay, 10 μL of the phage (1010 PFU/ml) was spotted on the host bacterial lawn (OD600 ~ 0.1) and incubated for 12 hours at 37 °C. Following incubation, plaque formation was documented by capturing images from three independent plates. A representative image for each condition is presented in Fig. 1d and h.

Isolation of wild phage KOR_P1 and KOR_P2

The phages were isolated from the Codiga Resource Recovery Center (CR2C) at Stanford (692 Pampas Lane, Stanford, CA 94305, United States). Wastewater from the plant was centrifuged and then the supernatant was filtered (pore size = 0.22 μm). PAO1Δpf4Δpf6 was used as a host and then mixed with the filtered sewage, and grown on an agar overlay overnight at 37 °C. Clear individual plaques were selected and suspended in the phage buffer. Using this phage-containing buffer, this process was repeated three times, and phages KOR_P1 and KOR_P2 were plaque-purified and then quantified for their PFU.

Isolation of phage genomic DNA

Phage genomic DNA from KOR_P1 and KOR_P2 was extracted by the following method using 0.5 ml of lysate (1010 pfu/ml). To remove any residual bacterial DNA and RNA present in the lysate, 0.48 ml of the filter-sterilized lysate was incubated with 1 μL DNase I (1 U/μL) and 1 μL RNase A (10 mg/mL) for 90 min at 37 °C without shaking. Thereafter, 20 μL of 0.5 M EDTA (final concentration 20 mM) was added to inactivate DNase I and RNase A. To digest the phage protein capsid, 1.25 μL Proteinase K (20 mg/mL) was then added and incubated for 90 min at 55 °C without shaking. The digested phage DNA was then purified with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, 69504) with the modified manufacturer manual73.

Transmission electron microscopy

Images of high-titer phage lysates (5 µl) were collected as follows. The phage lysates were absorbed onto glow discharged forever and carbon-coated copper grids (300 nm mesh size, Electron Microscopy Sciences) at room temperature for 5 min, negatively stained with 1% (w/v) uranyl acetate at room temperature for 1 min and imaged with a JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope (Jeol) operated at 120 kV. The images were taken with a GATAN Multiscan 791 CCD camera.

Construction of phylogenetic trees for bacteriophages

Sequences of phage DNA were obtained from the database found in NCBI Nucleotide. The sequences of vFB009, vFB433, and vFB468 were provided from the original source (Felix Biotechnology, Inc). Using the Tree Builder in the Geneious Prime software with the default settings, phylogenetic trees were generated and the genetic distances between phages were obtained.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS), genome assembly, annotation, and comparison

Libraries of the selected bacterial DNA samples (input DNA 0.2 ng/μl) were prepared using the Illumina Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, FC-131-1024) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing of DNA (paired-end 2 × 150 high output) was carried out using the Illumina NovaSeq PE150 platform. After adapter trimming, sequence reads were assembled using the Geneious Prime v2023.1.2. All individual genome assemblies were annotated and assessed through mapping to the reference P. aeruginosa PA14 bacterial genome NC_008463 with default settings. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection was conducted using the Geneious Prime software with the default settings.

Suppression assays using knockouts library of P. aeruginosa PA14

The knockout mutants used for the suppression assays included 11 strains, which are listed in the Supplementary Table 4 and differed in the knockout of a gene for a surface-expressed protein involved in the phage receptors: type IV pili genes (pilA, pilB, pilC, pilW, pilTU, pilX, and pilY1), flagella genes (fliC and flaK), a Mex system protein gene (oprM), and a OSA/LPS synthesis gene (wapR). Suppression assays were conducted as mentioned above. The suppression ability of a phage on the test knockout strain was compared to its ability on the phage-sensitive host (P. aeruginosa strain PA14).

Motility (twitching and swimming) assays

Following an established protocol52, bacterial cultures were grown overnight and diluted and regrown to OD = 0.1-0.2. Using a pipette tip, the bacterial suspension was transferred by a puncture into the agar plates (containing a 1% tryptone medium with different concentrations of agar (0.3% for swimming motility and 2% for twitching motility)). The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours (swimming motility) and 48 hours (twitching motility). After the incubation, the growth zones were measured. For swimming motility, the measurement was made directly. For twitching motility, the agar layer was removed and the bottom of the plate was stained with 5 ml of a 0.01% solution of crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, C0775) for 10 min and washed with DI water. Each experiment condition was performed for at least 5 repetitions and the obtained images were processed with the software Fiji (v2.9.0) and ImageJ.

Colony biofilm morphology assay

Following an established protocol74, 1 μL of overnight PA14 cultures was spotted onto the agar plates (containing a 1% TSB medium fortified with 40 mg/L Congo red and 20 mg/L Coomassie brilliant blue dyes and solidified with 1% agar). Biofilms were grown at 25 °C, and images were acquired after 100 hours, using a Leica M80 Stereo Microscope mounted with a Nikon 170 camera at 7.5 × zoom. Each experiment condition was performed for at least 3 repetitions and the obtained images were processed with the software Fiji (v2.9.0) and ImageJ.

Hitchcock and Brown LPS Preparation, LPS SDS-PAGE, and LPS modified silver staining

LPS was prepared following the Hitchcock and Brown LPS Preparation method75. 3 μL of LPS solutions were treated for 5 min at 100 °C after mixing with 17 μL water and 20 μL sample buffer. The 40 μL mixture was transferred into each well of a 12% discontinuous PAGE mini-slab Tris-glycine-polyacrylamide gels and poured with the SDS-running buffer (0.25 M Tris, 1.92 M glycine, 1 % w/v SDS)) in a vertical gel electrophoresis system, and then ran at 200 V for 50 min. The fractionated LPS-SDS-PAGE-gels were first oxidized with 0.7% periodic acid in 40% ethanol-5% acetic acid at 25 °C for 30 min without any prior fixation. The gels were washed twice with DI water and followed the protocol of the Pierce™ Silver Stain Kit (Thermo Scientific, 24612). The final images were taken by a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP imaging system and the obtained images were processed with the software Fiji (v2.9.0) and ImageJ.

Surface biofilm imaging assays

Following the previous protocol for the biofilm imaging57,76, the overnight cultures from those strains that encode a gene that constitutively expresses fluorescent proteins were regrown and diluted to OD600 ~ 0.001 and 100 μL of the diluted cultures were added to wells of 96-well plates with no. 1.5 coverslip bottoms (MatTek, NC0049443). The cells were allowed to attach for 10 min, after which the wells were washed twice with fresh LB medium. Subsequently, 100 μL of fresh LB medium was added and grown at 25 °C. Images were acquired with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 confocal spinning disk unit mounted on a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope, using a 60× water objective with a numerical aperture of 1.2, the 405/488/561/642 multichroic laser, and a Photometrics Prime 95B camera. All experimental images in this work were acquired and rendered using Nikon NIS-Elements software. Each biofilm covering a surface area of 109 × 109 μm2 was imaged at six different regions for each well in at least n = 3 independent experiments. Each image was then segmented in the z-plane and assessed independently to count the cells in the biofilms using the previously published custom code77.

Modified microtiter dish biofilm formation assay

Following an established protocol78 with modifications, strains that do not encode a gene that constitutively expresses fluorescent proteins (e.g., clinical isolated strains) were cultured overnight, regrown, and diluted to OD600 ~ 0.001. 15 μL of the diluted cultures were then added to each 96-well plate with 135 μL of LB media containing phage cocktails, as applicable. The plate was then covered with a pegylated lid and sealed with the sides of the plate with a permeable membrane (Sigma-Aldrich, Z763624) to prevent evaporation and incubated for 48 hours at 25 °C with shaking of 100 rpm. After 48 hours, the biofilm-attached pegylated lid was removed and placed into the fresh plate that contains sterile PBS. Then, the plate was shaken for 1 min to wash out the un-attached bacteria from the lid. After this process, the lid was placed on a fresh plate with 200 μL of sterile LB media in each well and sonicated for 1 h to dislodge biofilm cells from the lid by the vibrations created by the sonicator. After removing the lid from the plate, biofilm cells in the plate were amplified for 24 hours and then OD600 was measured to quantify the cells. The Suppression Index (%) was calculated as the OD600 for the non-treated condition minus the treated condition divided by the OD600 for the non-treated condition.

Antibiotic-phage synergic assays

P. aeruginosa strain PA14 and S. aureus strain 1203 were grown overnight at 37 °C as described above. The cultures were back-diluted 1:200, and re-grown for 2-3 hours (to OD600 ~ 0.1-0.2). Then, the re-grown cultures were diluted 1:100 (OD600 ~ 0.001-0.002) into wells on a 96-well plate with LB to a total volume of 150 μL with/without a phage and/or antibiotics to reach the target MOIs and serial concentrations. The plates were incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 30 hours, the OD600 growth curves were obtained, and the bacterial levels (a.u., defined as the AUCs of OD600 for 30 hours) were obtained from triplicate experiments for each concentration of either an antibiotic or a phage individually or both of note, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for bacterial strains used in this study (Supplementary Table 3) were obtained using Liofilchem® MTS (the MIC Test Strip, Fisher Scientific, 22-777), gradient tests used to determine MIC values.

Synergy scores were obtained for the antibiotic-phage interaction using the Highest Single Agent model79,80. In brief, bacterial cells grow under specific concentrations involving either an antibiotic or a phage. The impact of the more effective agent (by either an antibiotic or a phage) was defined as the expected effect of the combination of both an antibiotic and a phage. If the observed growth suppression in combination was equal to the expected value, each of the antibiotic and a phage was deemed to be independent. If the growth suppression was more or less than expected, the antibiotic and a phage were deemed to be synergistic or antagonistic, respectively. When an antibiotic and a phage were combined, the observed effect of the combination could be high or low, compared to what was expected given the individual effects of a given agent. The synergic scores were measured by comparing the growth suppression to an antibiotic and a phage and their combinations.

In vivo murine full-thickness wound infection model

All male C57BL/6 J mice for the wound infection experiments were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor). Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, with free access to food and water, in the vivarium at Stanford University. All experiments and animal use procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the School of Medicine at Stanford University. The study design was adapted from the previous work58. In brief, 6–8-week-old male mice (total number = 47) were anesthetized using 3% isoflurane. The dorsum of mice was shaved using a hair clipper and depilated using Nair hair removal cream (Church and Dwight). The shaved area was cleaned with betadine (Fischer Scientific, 19066452) and alcohol swabs. Mice received 0.1-0.5 mg/kg slow-release buprenorphine (ZooPharm) subcutaneously before wounding. Bilateral dorsal full-thickness wounds were created using 6-mm biopsy punches (Integra). The wounds were covered with Tegaderm (3 M). PAO1, PA14, and CPA 050 were grown as described above and diluted and mixed to 1 × 107 CFU/mL in a 1:1:1 ratio. Mice received 5 × 104 CFU/wound bacteria via injection into each wound under the Tegaderm patch. All mice received the first treatment at two hours post-infection and the second treatment at 24 hours post-infection. A phage cocktail (KIM-C1) was prepared on the same day of the treatment in MOI = 200 in a 1:1:1 ratio for each individual phage. The phage cocktail (KIM-C1) and the phage mocktail (KIM-M1) were administered topically to the mice wound. Control mice were topically treated with phage buffer. Mice were weighed daily and provided with Supplical Nutritional Supplement Gel (Henry Schein Animal Health). Three days post-infection, mice were euthanized by CO2 chamber and cervical dislocation and the wound bed was excised, homogenized, and plated for CFU analysis.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed with a minimum of three independent replicates, and these values were used to plot mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 9.0 software package, and data were analyzed using unpaired t-tests, ordinary one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and multiple comparison test to determine the significance of results. Results were taken as significantly different by a p-value of <0.05 unless otherwise stated.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The DNA sequencing data are available from NCBI GenBank under accession codes: PQ316107, PQ431181 - PQ431192.

Code availability

All custom codes used to process biofilms are available in the previously published paper77 (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-00817-4).

References

Antimicrobial Resistance, C. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

Hatfull, G. F., Dedrick, R. M. & Schooley, R. T. Phage therapy for antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. Annu Rev. Med. 73, 197–211 (2022).

Pirnay, J. P. et al. Personalized bacteriophage therapy outcomes for 100 consecutive cases: a multicentre, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 1434–1453 (2024).

Uyttebroek, S. et al. Safety and efficacy of phage therapy in difficult-to-treat infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 22, e208–e220 (2022).

Schooley, R. T. et al. Development and Use of Personalized Bacteriophage-Based Therapeutic Cocktails To Treat a Patient with a Disseminated Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61 https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00954-17 (2017).

Cano, E. J. et al. Phage Therapy for Limb-threatening Prosthetic Knee Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection: Case Report and In Vitro Characterization of Anti-biofilm Activity. Clin. Infect Dis. 73, e144–e151 (2021).

Jennes, S. et al. Use of bacteriophages in the treatment of colistin-only-sensitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicaemia in a patient with acute kidney injury-a case report. Crit Care 21, 129 (2017).

Jault, P. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a cocktail of bacteriophages to treat burn wounds infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PhagoBurn): a randomised, controlled, double-blind phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 19, 35–45 (2019).

Gorski, A., Borysowski, J. & Miedzybrodzki, R. Phage therapy: Towards a successful clinical trial. Antibiotics (Basel) 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9110827 (2020).

Leitner, L. et al. Intravesical bacteriophages for treating urinary tract infections in patients undergoing transurethral resection of the prostate: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 21, 427–436 (2021).

de Jonge, P. A., Nobrega, F. L., Brouns, S. J. J. & Dutilh, B. E. Molecular and evolutionary determinants of bacteriophage host range. Trends Microbiol. 27, 51–63 (2019).

Jorth, P. et al. Regional isolation drives bacterial diversification within cystic fibrosis lungs. Cell Host Microbe 18, 307–319 (2015).

Limoli, D. H. et al. Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa co-infection is associated with cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and poor clinical outcomes. Eur J Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 35, 947–953 (2016).

Oechslin, F. Resistance development to bacteriophages occurring during bacteriophage therapy. Viruses 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/v10070351 (2018).

Stokar-Avihail, A. et al. Discovery of phage determinants that confer sensitivity to bacterial immune systems. Cell 186, 1863–1876 e1816 (2023).

Egido, J. E., Costa, A. R., Aparicio-Maldonado, C., Haas, P. J. & Brouns, S. J. J. Mechanisms and clinical importance of bacteriophage resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 46, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuab048 (2022).

Gelman, D. et al. Clinical phage microbiology: a suggested framework and recommendations for the in vitro matching steps of phage therapy. Lancet Microbe 2, e555–e563 (2021).

Hoyland-Kroghsbo, N. M., Maerkedahl, R. B. & Svenningsen, S. L. A quorum-sensing-induced bacteriophage defense mechanism. mBio. 4, e00362–00312 (2013).

Kronheim, S. et al. A chemical defence against phage infection. Nature 564, 283–286 (2018).

Glonti, T. & Pirnay, J. P. In Vitro Techniques and Measurements of Phage Characteristics That Are Important for Phage Therapy Success. Viruses 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/v14071490 (2022).

Abedon, S. T., Danis-Wlodarczyk, K. M. & Wozniak, D. J. Phage cocktail development for bacteriophage therapy: Toward improving spectrum of activity breadth and depth. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14101019 (2021).

Molina, F. et al. A new pipeline for designing phage cocktails based on phage-bacteria infection networks. Front Microbiol. 12, 564532 (2021).

Schmerer, M., Molineux, I. J. & Bull, J. J. Synergy as a rationale for phage therapy using phage cocktails. PeerJ 2, e590 (2014).

Hall, A. R., De Vos, D., Friman, V. P., Pirnay, J. P. & Buckling, A. Effects of sequential and simultaneous applications of bacteriophages on populations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in wax moth larvae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 5646–5652 (2012).

Merabishvili, M., Pirnay, J. P. & De Vos, D. Guidelines to compose an ideal bacteriophage cocktail. Methods Mol. Biol. 1693, 99–110 (2018).

Haines, M. E. K. et al. Analysis of selection methods to develop novel phage therapy cocktails against antimicrobial resistant clinical isolates of bacteria. Front Microbiol. 12, 613529 (2021).

Tagliaferri, T. L., Jansen, M. & Horz, H. P. Fighting pathogenic bacteria on two fronts: Phages and antibiotics as combined strategy. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9, 22 (2019).

Gu Liu, C. et al. Phage-antibiotic synergy is driven by a unique combination of antibacterial mechanism of action and stoichiometry. mBio. 11, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01462-20 (2020).

Lusiak-Szelachowska, M. et al. Bacteriophages and antibiotic interactions in clinical practice: what we have learned so far. J Biomed Sci. 29, 23 (2022).

Lood, C., Haas, P. J., van Noort, V. & Lavigne, R. Shopping for phages? Unpacking design rules for therapeutic phage cocktails. Curr Opin Virol 52, 236–243 (2022).

Hammerl, J. A. et al. Reduction of Campylobacter jejuni in broiler chicken by successive application of group II and group III phages. PLoS One 9, e114785 (2014).

Menor-Flores, M., Vega-Rodriguez, M. A. & Molina, F. Computational design of phage cocktails based on phage-bacteria infection networks. Comput Biol. Med. 142, 105186 (2022).

Gu, J. et al. A method for generation phage cocktail with great therapeutic potential. PLoS One 7, e31698 (2012).

Yang, Y. et al. Development of a Bacteriophage Cocktail to Constrain the Emergence of Phage-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol. 11, 327 (2020).

Tanji, Y. et al. Toward rational control of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by a phage cocktail. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64, 270–274 (2004).

Gordillo Altamirano, F. L. & Barr, J. J. Unlocking the next generation of phage therapy: the key is in the receptors. Curr Opin Biotechnol 68, 115–123 (2021).

Wright, R. C. T., Friman, V. P., Smith, M. C. M. & Brockhurst, M. A. Cross-resistance is modular in bacteria-phage interactions. PLoS Biol. 16, e2006057 (2018).

McVay, C. S., Velasquez, M. & Fralick, J. A. Phage therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a mouse burn wound model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51, 1934–1938 (2007).

Morales, E. et al. Hospital costs of nosocomial multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa acquisition. BMC Health Serv Res 12, 122 (2012).

Lee, B. Y. et al. The economic burden of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19, 528–536 (2013).

Beal, J. et al. Robust estimation of bacterial cell count from optical density. Commun Biol. 3, 512 (2020).

Cady, K. C., Bondy-Denomy, J., Heussler, G. E. & Davidson, A. R. & O’Toole, G. A. The CRISPR/Cas adaptive immune system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mediates resistance to naturally occurring and engineered phages. J Bacteriol 194, 5728–5738 (2012).

Xie, Y., Wahab, L. & Gill, J. J. Development and validation of a microtiter plate-based assay for determination of bacteriophage host range and virulence. Viruses 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/v10040189 (2018).

Dimitriu, T. et al. Bacteriostatic antibiotics promote CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity by enabling increased spacer acquisition. Cell Host Microbe 30, 31–40.e35 (2022).

Ashworth, E. A. et al. Exploiting lung adaptation and phage steering to clear pan-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in vivo. Nat. Commun. 15, 1547 (2024).

Chan, B. K. et al Personalized Inhaled Bacteriophage Therapy Decreases Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.23.22283996 (2023).

Hatfull, G. F. & Hendrix, R. W. Bacteriophages and their genomes. Curr. Opin Virol 1, 298–303 (2011).

Burrows, L. L. Pseudomonas aeruginosa twitching motility: type IV pili in action. Annu Rev. Microbiol. 66, 493–520 (2012).