Abstract

Adeno-associated virus-based gene therapy is a promising avenue in heart failure treatment, but has shown limited cardiac virus uptake in humans, requiring new approaches for clinical translation. Using a Yorkshire swine ischemic heart failure model, we demonstrate significant improvement in gene uptake with temporary coronary occlusions assisted by mechanical circulatory support. We first show that mechanical support during coronary artery occlusions prevents hemodynamic deterioration (n = 5 female). Subsequent experiments show that coronary artery occlusions during gene delivery improve gene transduction, while adding coronary sinus occlusion (Stop-flow) further improves gene expression up to >1 million-fold relative to conventional intracoronary infusion. Complete survival during and after delivery (n = 10 female, n = 10 male) further indicates safety of the approach. Improved cardiac gene expression correlates with virus uptake without an increase in extra-cardiac expression. Stop-flow delivery of virus-sized gold nanoparticles exhibits enhanced endothelial adherence and uptake, suggesting a mechanism independent of virus biology. Together, utilizing mechanical support for cardiac gene delivery offers a clinically-applicable strategy for heart failure-targeted therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) accounts for a major growing morbidity1, requiring new approaches to intercept progression and reduce disease burden. Gene therapy continues to show benefits in preclinical and clinical studies targeting debilitating diseases; however, no gene therapies for HF are yet clinically available2. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is one of the most promising vectors for HF therapy because it offers long-term gene expression, displays cardiotropism in some serotypes, and is non-pathogenic for humans3. Indeed, animal studies showed that gene therapy with sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) by intracoronary delivery of AAV serotype 1 improves cardiac function4,5,6,7. However, despite promising results in the Phase 1/2a clinical trial8, it failed to demonstrate consistent efficacy in the Phase 2b study that enrolled 250 patients9. Post-trial analysis of myocardial tissues from some of the patients who received gene therapy demonstrated minimal AAV detection10 within the myocardium (less than 1% of infected cardiac cells), indicating very low AAV uptake in the human heart as a likely reason for the lack of efficacy in these patients. While increasing the AAV dose is one approach to improve gene transfer efficacy, recent reports in ongoing clinical trials from other disease areas suggest a dose-dependent increase in serious side effects, including major morbidities and death11,12,13. Achieving efficient uptake without dose escalation remains a critical challenge for cardiac gene delivery, particularly in attaining target specificity and surpassing cellular barriers, without facing immunogenicity2.

Factors that have been identified as contributing to vector uptake in intracoronary delivery include vector dose, vector dwell time at the target site, coronary flow, and perfusion pressure14,15. Various advances made in coronary intervention techniques and tools during the past few decades now offer unique opportunities to modify some of these factors during delivery. We hypothesized that extending AAV dwell time in the coronary system would significantly improve cardiac AAV uptake and gene expression.

In this study, we utilize brief coronary artery and sinus balloon occlusions, which are common procedures in interventional cardiology and electrophysiology, respectively. To avoid the hemodynamic risk and ischemic myocardial damage in using balloon occlusions for delivery16, we employ temporary mechanical circulatory support (MCS). The Impella (Abiomed, Inc., Danvers, MA) cardiac pump, a catheter-based device for MCS, can replace the mechanical work of the heart and is able to support hemodynamics in patients with low cardiac function17,18. Benefits of MCS also include reduction of myocardial oxygen consumption and wall stress reduction, often referred to as unloading19. Taken together, we propose a clinically relevant technique for heart-targeted gene delivery by taking advantage of modern coronary intervention techniques and tools to address major challenges in the clinical translation of cardiac AAV gene therapy.

Results

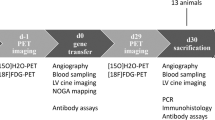

The overall study design is shown in Fig. 1. All pigs underwent anterior myocardial infarction (MI) induction 1 week prior to gene delivery to simulate gene delivery in HF patients as expected in clinical application. To evaluate the impact of intracoronary gene delivery method modifications on transgene expression, we injected 5.0 × 1013 viral genomes (vg) of AAV serotype 6 encoding for luciferase (AAV6.Luc) with the CMV promoter into male (n = 9; 37.4 ± 1.21 kg) and female (n = 8; 37.1 ± 0.75 kg) Yorkshire pigs (with at least one of each sex per delivery group). An additional 3 pigs (2 female, 1 male) received direct intramyocardial injection of AAV6.Luc for comparison. None of the animals died during or after the procedure, and all survived until the planned endpoint. AAV antibodies were not screened prior to delivery due to concerns that antibody titer at screening would not reflect the level of immune response at injection due to the immune activation associated with MI. Retrospective analysis of pre-injection blood showed relatively high antibody titers against AAV6 across groups (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Acute myocardial infarction was induced in Yorkshire pigs by temporal balloon occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) at day 0. One week later, animals were used for acute hemodynamic study (n = 5), acute nanoparticle study (n = 3), and AAV gene delivery study (n = 20), where n are independent animals and experimental procedures. AAV was injected via intracoronary delivery, followed by tissue harvest at 5 weeks for expression analysis. Intracoronary AAV injection was performed by one of five delivery methods: Continuous without mechanical circulatory support (MCS) (Continuous), Continuous with MCS (Continuous, MCS), Coronary artery occlusion with MCS (CAO), Stop-flow with MCS (Stop-flow), or Stop-flow without MCS and short occlusions (Stop-flow, short). AAV was delivered through the balloon wire lumen during balloon occlusions in the LAD (90 s each) and left circumflex artery (60 s each) in CAO and Stop-flow groups and for 15 s each in the same arteries in the short Stop-flow group.

Mechanical support stabilizes hemodynamics during occlusions

Coronary balloon occlusions during AAV delivery can result in hemodynamic instability due to myocardial ischemia, especially in those with low cardiac reserve, and despite the use of anti-arrhythmic drugs. Therefore, prior to the AAV delivery study, we first examined the efficacy of applying catheter-based MCS to maintain hemodynamics and alleviate myocardial ischemia during coronary balloon occlusions. Five female Yorkshire pigs underwent proximal to mid-left anterior descending artery (LAD) occlusion to induce HF associated with large anterior MI. One week later, these pigs were enrolled for the acute safety/feasibility test (Fig. 2A). The Impella CP device, able to provide up to 3.5 L/min of MCS flow, was inserted via femoral arterial access. Arterial pressure and electrocardiogram (ECG) were monitored during coronary artery occlusions with and without MCS. Interestingly, MCS played little role during coronary occlusion of the infarcted LAD; a 5-min balloon occlusion of the LAD resulted in a small decrease in systolic aortic blood pressure even without MCS, likely due to minimum viable myocardium left in the infarcted area. Under MCS, systolic aortic pressure was maintained over the occlusion period, similar to the non-MCS setting (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, balloon occlusion of the non-infarcted left circumflex artery (LCx) resulted in a rapid decline in systolic blood pressure in the absence of MCS and one of the animals developed ventricular fibrillation. In contrast, MCS during LCx occlusion successfully maintained systolic aortic pressure for the entire 5-min duration in all animals (Fig. 2C). ECG showed less ST elevation and less frequent premature ventricular contractions under MCS. Because pigs have a small right coronary artery compared to humans and minimal supply to the LV, MCS support seemed effective in supporting the total LV ischemia at least for 5 min. To mimic AAV delivery, an X-ray contrast agent was slowly injected through the balloon wire lumen during coronary occlusion. Serial imaging at 15-second intervals showed that contrast is barely seen after 90 s in the infarcted LAD, and 60 s in the non-infarcted LCx, indicating its washout by collateral or retrograde flow distal to the balloon occlusion.

a Blood pressure was monitored in five animals one week after myocardial infarction (MI) during coronary artery balloon occlusions without and with mechanical cardiac support (MCS). b, c Following ischemic preconditioning, infarcted (LAD; b) and non-infarcted (LCx; c) coronary arteries were occluded with an over-the-wire coronary balloon for 5 min, and systolic aortic pressure was recorded at 0 and at 5 min. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Coronary artery occlusion delivery improves gene expression

After establishing the feasibility and hemodynamic safety of coronary balloon occlusions under MCS in HF animals, we examined whether intracoronary AAV delivery with coronary artery occlusion (CAO, n = 3) could enhance transgene expression in the left ventricle (LV) in comparison to delivery by slow, continuous infusion over 10 min (Continuous, n = 3). Occlusion duration was set at 90 s each for LAD and 60 s each for LCx based on the above feasibility study (Fig. 2). The CAO group showed increased gene expression in some LV regions (Fig. 3A, B) that exceeded the mean expression levels after Continuous delivery, despite variability. To evaluate if the cardiac unloading effects of MCS might have led to improved gene expression, we enrolled an additional group for Continuous Delivery with MCS (n = 4). Compared to the Continuous group without MCS, the addition of MCS provided no obvious improvement in luciferase expression across LV tissue regions (Fig. 3C), suggesting that coronary artery occlusion, but not the effect of cardiac unloading, was the primary cause of improved gene expression.

a Different areas of myocardium from LV base, mid, and apex were collected to study gene distribution. Luciferase expression data were normalized to total protein. b, c Luciferase expression in the LV was compared between Continuous (n = 3) and CAO (n = 3) delivery groups (b) and between Continuous delivery without (n = 3) and with (n = 3) the addition of MCS (c) to assess the contribution of balloon occlusions or MCS to gene expression. All n-values represent biological replicates, with each point averaged from technical triplicates within the same animal. Expression is shown as mean ± SEM of biological replicates. Comparisons were conducted as a two-tailed t test with p-value set at 0.05. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Dotted lines separate linear and logarithmic scales in (b). Infarct refers to the mid-anterior region. Border refers to the infarct-border at the mid-lateral region. Post, posterior; Epi, epicardial; Endo, endocardial; Lat, lateral; Sept, Septum.

Stop-flow delivery significantly improves gene expression

Based on our hypothesis that extension of AAV dwell time results in improved gene expression, we sought to further increase vector dwell time by preventing venous washout through the addition of coronary sinus occlusion (Stop-flow). Stop-flow delivery with MCS resulted in impressive improvement in luciferase expression across LV regions compared to both Continuous and CAO delivery, with significant differences among groups in most LV tissues (Fig. 4). Expression in posterior epicardium was one of the most pronounced areas with a statistically significant improvement by Stop-flow compared to combined Continuous delivery groups with and without MCS (1,517,894-fold increase in mean, p = 0.048, CI [33,694, 68,380,196]). Notably, the highest average expression levels following Stop-flow delivery superseded the highest average expression levels achieved following direct intramyocardial injection, which received 5.0 × 1012 vg per injection site.

Average normalized luciferase expression was compared between Stop-flow and other groups shown in Fig. 3. Continuous delivery groups with and without mechanical cardiac support were combined due to similar expression between the two. Dotted lines separate linear and logarithmic scales. Statistical significance is denoted at *p < 0.05. Continuous (Combined), n = 7; CAO, n = 3; Stop-flow, n = 4; Stop-flow, short, n = 3; IM, n = 3. All n-values represent biological replicates, with each point averaged from technical triplicates within the same animal. Expression is shown as mean ± SEM of biological replicates. Post, posterior; Epi, epicardial; Endo, endocardial; Lat, lateral; Sept, Septum. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Statistics reflect comparisons by Kruskal-Wallis test where H, η2, p (exact): Apex (4.245, 0.10, 0.2498); Infarct (4.089, 0.08, 0.2645); Border (7.221, 0.32, 0.0471); Posterior endocardial (7.745, 0.37, 0.0322); Posterior epicardial (9.924, 0.53, 0.0051); Septum (5.681, 0.21, 0.1210); Base lateral (7.594, 0.35, 0.0361); Base septum (7.694, 0.36, 0.0336).

Given dramatic increases in gene expression and to explore the potential exclusion of MCS during Stop-flow delivery, we investigated if shorter duration occlusions without MCS might be possible and sufficient to improve gene expression. Stop-flow with 15-s occlusions in the absence of MCS (Stop-flow, short; n = 3) was tolerated, and also exhibited improved expression with some variability. One pig in the 15-s occlusion group showed minimal improvement across the heart tissues, suggesting that the duration of occlusions may be important in securing improvement rather than improvement being occlusion time-dependent.

Increased AAV uptake results in improved gene expression

To determine whether differences in gene expression could be attributed to greater AAV uptake, vg in each of the LV tissue regions was quantified by qPCR. Stop-flow delivery resulted in markedly increased vg/mg of DNA in most LV tissue regions that was significantly higher in border (padj = 0.023, Z: 2.888) and posterior epicardial (padj = 0.005, Z: 3.373) regions compared to Continuous delivery (Fig. 5A). Correlation analysis demonstrated an overall positive association between viral genome and normalized luciferase expression (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, correlation in non-infarct tissue regions was more obvious in contrast to infarcted regions (apex and infarct) that showed poor association between AAV uptake and luciferase expression (Supplementary Fig. 2). Specifically, despite a trend of higher luciferase expression in infarcted regions within the balloon occlusion groups, AAV genomic DNA was not correlated. To understand the distribution patterns of AAV gene expression, we used the RNAscope (ACD Bio, Newark, CA) approach to detect the luciferase gene (probe #313408). Non-infarcted remote (posterior) and infarct sample tissues after Stop-flow delivery showed transgene distribution in cardiomyocyte cytoplasm that was notably higher in posterior compared to infarct regions (Fig. 6). Post-analysis of blood samples at the time of AAV delivery revealed no overall correlation between NAb titer and gene expression across delivery groups, implying that expression was influenced by delivery method over the presence of NAbs (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Viral genome (vg) quantification by qPCR compared AAV uptake in LV regions after coronary balloon occlusions (CAO, n = 3; Stop-flow, n = 4; Stop-flow, short, n = 3) vs Continuous delivery (n = 7). The dotted line separates linear and logarithmic scales. b Vg in LV tissue regions was plotted against normalized luciferase in each delivery group. The dashed lines represent the average limits of detection for vg and luciferase expression. All n-values represent biological replicates, with each point averaged from technical triplicates within the same animal. Expression is shown as mean ± SEM of biological replicates. Post, posterior; Epi, epicardial; Endo, endocardial; Lat, lateral; Sept, Septum. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Statistical significance is denoted at *p < 0.05. Statistics reflect delivery comparisons in vg by Kruskal-Wallis test where H, η2, p (exact): Apex (6.543, 0.27, 0.707); Infarct (2.865, − 0.01, 0.4351); Border (11.12, 0.62, 0.0017); Posterior endocardial (5.361, 0.18, 0.1142); Posterior epicardial (12.81, 0.75, 0.0002); Septum (0.2506, − 0.21, 0.9810); Base lateral (8.187, 0.40, 0.0239); Base septum (1.274, − 0.13, > 0.9999).

Examination of tissue distribution of vector via luciferase transgene probe (green) using RNAscope shows cardiomyocyte cytoplasmic distribution (arrowheads) in both posterior (remote) and infarct tissues. Sample areas of positive signal distribution are shown from posterior epicardial tissue and limited expression in infarct tissue (n = 2 biological replicates with highest luciferase expression). Acquisition at 40x magnification. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Improved gene expression is limited to the heart

Given that balloon occlusion delivery resulted in improved LV gene expression, we also looked at whether significant changes in transgene expression could be observed in off-target areas of the heart and in extra-cardiac organs (lung, liver, spleen, kidney cortex and medulla, skeletal muscle, brain). There was a trend of increased luciferase expression in the coronary arteries with balloon occlusions (Stop-flow > CAO). CAO and Stop-flow delivery also resulted in higher gene expression in the left atrium in comparison to Continuous delivery, although only one animal exhibited high expression in the CAO group. Meanwhile, relatively lower luciferase expression was seen in the right ventricle, and little to no expression was seen in the liver and kidney cortex in all groups (Fig. 7A). AAV uptake was also detected by qPCR in the coronary artery and left atrium, as well as in liver and spleen in a few samples largely at much lower levels compared to LV tissues after Stop-flow (Fig. 7B).

a, b Average (a) luciferase expression and (b) AAV uptake in other cardiac and non-cardiac tissues in intracoronary delivery groups. Tissues that showed positive expression in any of the animals are shown. The dotted line in (a) separates linear and logarithmic scales. Continuous (Combined), n = 7; CAO, n = 3; Stop-flow, n = 4; Stop-flow, short, n = 3. All n-values represent biological replicates, with each point averaged from technical triplicates within the same animal. Expression is shown as mean ± SEM of biological replicates. Post, posterior; Epi, epicardial; CA, coronary artery; RV, right ventricle; LA, left atrium. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Balloon occlusion delivery does not impair cardiac function

To evaluate if delivery with coronary balloon occlusions could result in long-term cardiac impairment, we assessed cardiac function and remodeling before and 1 month after AAV delivery. Final infarct size was not significantly different between groups (p = 0.6169, H: 2.952, η2 = − 0.10) (Supplementary Fig. 3). No difference in hemodynamic or functional parameters (Table 1) was found between groups, reflecting a lack of chronic hemodynamic impairment associated with balloon occlusion delivery or temporary MCS use.

Stop-flow physiologically enhances acute vector uptake

To examine whether the improved uptake is attributed specifically to AAV biology, we injected AAV-sized (20 nm) gold nanoparticles instead of AAV and studied their acute retention using electron microscopy. Tissue samples from remote (mid-posterior) and infarct (mid-anterior) LV regions were collected 30 min after Continuous and Stop-flow delivery. Electron microscopic analysis showed the absence of gold nanoparticles in both the remote and infarct regions after Continuous delivery (Fig. 8A). In contrast, Stop-flow delivery resulted in multiple gold nanoparticles at the endothelium-lumen interface and some within vesicles in both the remote and infarct regions (Fig. 8B), indicative of a physiological effect on vector uptake by Stop-flow delivery. To evaluate whether this observation might be spurious or temporary, the same study with Stop-flow delivery was repeated but with tissue sample collection at 4 h after delivery. Similarly, the later time point resulted in multiple gold nanoparticles at the endothelium-lumen interface and within vesicles, with a shift toward higher numbers observed in endothelial vesicles (Fig. 8C).

a, b Images are representative of gold nanoparticle detection (a) 30 min after Continuous vs Stop-flow delivery and (b) 4 h after Stop-flow delivery in remote (mid-posterior) and infarct (mid-anterior) tissues. Gold nanoparticles were not detected after Continuous delivery but were found with Stop-flow delivery (gold arrows), either attached at the endothelium-lumen interface or in vesicular structures. Images acquired at 4000x-6000x direct magnification were fitted to the same scale. Scale bar in (a), larger images = 600 nm; scale bar in (a) projections, (b) = 200 nm. c Observed instances of gold nanoparticle detection over equivalent grid areas and imaging time were recorded in each condition (n = 1 animal per condition, with duplicate tissues from each tissue region) representing gold nanoparticle distribution.

Discussion

Our data support that intracoronary AAV uptake and gene expression in the heart are improved through delivery modifications using serial coronary balloon occlusions. The Stop-flow method led to improved site-specific transgene expression in the LV, even surpassing that of direct intramyocardial injection (1/10 AAV dose per injection site), which has been regarded as the most efficient method despite its highly focal distribution20. Considering also that covering the whole LV by direct intramyocardial injection would require more than 10 injection sites, we believe that our method can provide more efficient gene delivery to the whole heart than invasive surgical intramyocardial delivery. The application of a catheter-based MCS device is a clinically-applicable strategy for gene delivery that provides necessary hemodynamic stability during coronary occlusions. Since the Impella is already approved for clinical use in patients with cardiogenic shock and for high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention, our proposed delivery method can accelerate the clinical translation of cardiac AAV gene therapy.

Despite various rodent studies demonstrating the therapeutic benefits of AAV gene therapy for the heart in improving and even correcting molecular pathologies and function21, clinical translation has been hampered by poor cardiac AAV uptake in humans22. Our study addresses this key problem in the clinical realization of cardiac gene therapy by demonstrating significantly improved AAV uptake and gene expression over conventional delivery in the context of preceding HF onset. Intracoronary delivery offers a significant advantage for treating HF patients, including the catheter-based approach that can be tolerated by patients with low cardiac reserve, and more homogeneous gene distribution that allows for global targeting of the myocardium. While our data suggest a 15 s duration of serial occlusions might be able to achieve comparable gene expression without MCS in some patients, a longer duration might be important for consistency in the improvement. In addition, even 15 s of repetitive coronary ischemia can endanger patients with minimal cardiac reserve who are candidates for HF gene therapy. Our data indicates that MCS secures safety. Although not relevant in our study animals, it can also serve as back-up support in cases of patients developing acute congestive HF during the peri-delivery phase. Importantly, both coronary interventional techniques and Impella use are now widely performed in clinical practice23, offering potentially rapid clinical translation, particularly for unstable hearts, to benefit from earlier intervention aimed at intercepting HF progression.

The majority of current clinical trials dose > 1014 vg of AAV24, whereas our results were achieved following a total dose of 5.0 × 1013 vg (~ 1.38 × 1012 vg/kg), which may also directly impact cost associated with gene therapy and further AAV studies. Considering that pig cardiomyocytes have 6.4 pg DNA/genome25 and are multinucleated, > 109 vg/mg DNA in some of the tissues after Stop-flow corresponds to > 10 vg/cardiomyocyte. This is much higher than recent studies that examined cardiac AAV uptake26,27 despite the lower AAV dose used in our study, though the direct comparison is difficult given the difference in AAV serotype in other studies. More importantly, minimizing the AAV dose precludes serious side effects associated with high-dose AAV28. Over the last few years, multiple complications have arisen with the use of very high doses of AAV ~ 1014 vg/kg, resulting in severe liver toxicity, immune responses, acute kidney injury, and thrombotic microangiopathy, leading in some cases to death11,12,13,24. We observed in our study that delivery of a relatively low dose of vectors can result in highly efficient cardiac cell infectivity. Notably, the clear improvement shown in cardiac gene expression was not associated with a similar increase in off-target organs despite the use of a non-cardiac-specific promoter. Thus, our delivery method can be a platform for cardiac AAV gene delivery for any therapeutic genes targeting the heart.

Comparatively, most of the previous studies that examined the impact of delivery methods for improving cardiac vector uptake used other vectors such as adenovirus or non-viral materials29,30. It is important to note that AAV (20 nm) has a much smaller size than adenovirus (100 nm), which is significant when considering the size of pores in fenestrated capillaries (60–100 nm). In addition, the difference in biological properties, such as cell tropism, raises concerns as to whether findings in adenoviral gene therapy studies can be directly applied to AAV studies. A study by Keith et al.31 that used coronary artery occlusion to deliver cardiac stem cells in pigs found no improvement in acute retention. The authors concluded that coronary balloon occlusion does not influence cardiac stem cell uptake, which is in contrast to findings in AAV and highlights the importance of vector-specific delivery studies.

By directly showing significant improvement in AAV uptake and gene expression against control groups, we provide strong evidence that AAVs are amenable to uptake enhancement by physiological delivery modifications. Recently, Vekstein et al.30 reported improved AAV9 uptake with coronary balloon occlusion delivery. While the results are consistent with our findings, their study did not include coronary sinus occlusion, lacked transgene expression analysis or hemodynamic studies, and omitted disclosure of some details. Through our study design, we were able to demonstrate a full comparison of delivery groups with a consistent AAV serotype injected after disease onset and to include spatial distribution and transgene expression. Of note, it is interesting to find that both Vekstein et al. and our study found limited AAV expression after intramyocardial injection in the ischemic region, suggesting that intramyocardial gene delivery might not be as efficacious as it has been considered. Although limited, we are not the first to employ the Stop-flow concept for AAV delivery. Lampela et al.32 recently reported global LV gene distribution in naïve pigs using adenovirus and AAV with temporary coronary artery occlusion and sustained venous block during retrograde injection. Beeri et al.33 also found evidence of functional improvements following SERCA2a vs reporter gene expression via antegrade AAV6 injections and coronary vein occlusion prior to inducing ischemic mitral regurgitation in sheep. While the results of these studies are consistent with our findings, delivery was in naïve animals without hemodynamic evaluations. We provide insights for clinical translation by adding MCS and studying differences in gene uptake patterns among heterogeneous myocardial tissues after infarction. In our study, expression levels in posterior and lateral regions, areas with viable myocardium, most positively correlated with AAV uptake. In contrast, the weak correlation between AAV vg and luciferase expression in infarcted areas suggests that the effect of Stop-flow delivery might be different for respective tissue types. For example, similar AAV vg with higher luciferase expression in infarcted tissues suggests potential improvement in transcription or translation specific to these tissues by coronary balloon occlusion. How much tissue-dependent activation occurs needs to be studied in the future.

As mentioned above, prior studies using other vectors found several key factors that regulate the cardiac uptake of those vectors. We designed the study based on extending cardiac AAV dwell time, first through coronary artery occlusion and then further through both coronary artery and sinus occlusions to prevent AAV washout through the venous system. However, it is noteworthy that coronary sinus occlusion also changes coronary capillary pressure. Thus, our study is unable to conclude the contribution of vector dwell time vs capillary pressure in the improvement between CAO and Stop-flow delivery. Nevertheless, minimal uptake in one of the short Stop-flow group pigs suggests that the dwell time is an important factor for achieving consistent improvement, whereas coronary capillary pressure is likely important in increasing the uptake. Future studies should address the minimal required duration of Stop-flow and explore factors that predict improved expression even with short Stop-flow. Some studies have suggested that retrograde delivery might offer better efficacy than antegrade delivery34,35. While our study did not compare AAV delivery direction, we chose the antegrade route with respect to prior clinical trials and current clinical relevance and showed successful improvement in gene expression. Raake et al.36 similarly utilized temporary coronary occlusions for AAV delivery in ischemic myocardium with retrograde delivery. However, there is no data so far comparing the impact of injection directions in a consistent setting. We are planning follow-up studies to determine the importance of these factors for further improvement of delivery.

Finally, to understand whether improved cardiac AAV uptake was mainly associated with AAV biology, we examined acute retention and distribution of AAV-sized gold nanoparticles using electron microscopy. Interestingly, whereas no gold nanoparticles were found after slow Continuous delivery, some were found attached to the endothelium and some also in vesicular structures after Stop-flow delivery. While understanding how vesicular-mediated uptake contributes to improved gene expression requires extensive follow-up, our data indicates that the physiological properties of Stop-flow delivery are sufficient to influence AAV-sized nanoparticle uptake. This finding also opens the door for nanodrug delivery targeting the heart.

The major limitation of our study is sample size, which is associated with the high cost of experiments and vectors and the effort-demanding nature of large animal experiments. Yet, the impact of delivery modification was so large that we found statistically significant differences in both vg and luciferase expression when Continuous delivery groups with and without MCS were combined. In order to promote the clinical translation of cardiac AAV gene therapy, which is behind other disease areas, we decided that reporting current data might invoke new activities in academia and industry. All animals were enrolled 1 week post-MI, which is an active healing phase post-MI. While our data supports the safety of Stop-flow delivery with MCS in this vulnerable stage of the disease, tissue uptake patterns might be different in chronic MI. Given that our interest was to evaluate the effectiveness of the delivery method, we did not investigate a specific gene target for HF therapy. The impact of our research may be enhanced by combining our delivery with cardiac AAV gene therapy already in or approaching clinical trials.

In summary, we demonstrate that MCS provides necessary hemodynamic stability during Stop-flow AAV delivery in a clinically relevant HF model, which significantly improves AAV uptake and transgene expression. Considering that low cardiac gene transduction has impeded clinical translation, our delivery platform that can be applied to any gene targets might offer a breakthrough in cardiac AAV gene therapy.

Methods

Study design

Male and female Yorkshire pigs at the age of approximately 3 months were purchased from Animal Biotech Industries (Doylestown, PA) and were enrolled in all studies. All procedures were conducted in accordance with ethical approval (PROTO202100000003) from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Animal care and management were maintained in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Age, sex, and weight were all taken into consideration for appropriate housing conditions, medication dosing and equipment sizing during procedures, and health status over the course of each study. All animals were healthy at the time of the study and underwent a minimum 72-hour acclimatization period prior to participation. Other than overnight fasting prior to procedures, pigs retained daily access to food (LabDiet, 5081) and water. Weight measurements were taken prior to each procedure.

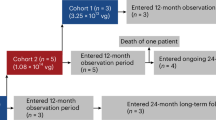

MCS hemodynamic study: Five pigs (n = 5, female, 38.7 ± 2.42 kg) were allocated for a safety/feasibility study. On day 0, animals underwent acute MI and were recovered. At 1 week, the Impella CP was guided to the LV for MCS to assess hemodynamic status during coronary artery occlusions without or with MCS. Aortic blood pressure and ECG were monitored throughout the study.

AAV study: As in the hemodynamic study, animals (36.8 ± 0.67 kg, n = 10 female, n = 10 male) had an acute anterior MI followed by delivery at 1 week, by either antegrade intracoronary (5 groups; n = 3-4 animals/group) or intramyocardial injection (1 group; n = 3 animals) with AAV serotype 6 encoding for luciferase (AAV6.Luc) using the CMV promoter (5.0 × 1013 vg, ~ 1.36 × 1012 vg/kg). For intracoronary delivery, MCS with the Impella CP was introduced in the LV in three of five groups prior to AAV delivery. The reference group received AAV6.Luc by slow continuous infusion (Continuous, n = 3) without MCS. In the MCS groups, animals were allocated to AAV6.Luc injection by either Continuous delivery (n = 4), during coronary artery occlusion (CAO, n = 3), or during both coronary artery and coronary sinus occlusions (Stop-flow, n = 4). An additional group included Stop-flow with shorter occlusion times but without MCS (Stop-flow, short, n = 3) (Fig. 1). An initial 9 animals for Continuous, Continuous with MCS, and CAO groups were randomized based on pre-AAV injection cardiac function evaluated with echocardiogram. The Stop-flow group was added after the completion of 9 animals, followed by the short Stop-flow group and another 2 animals (Continuous, MCS, and Stop-flow groups) to increase the sample size. Hemodynamic data were recorded throughout MCS and during delivery in all groups. The intramyocardial injection was performed by lateral thoracotomy. After AAV delivery, animals were recovered and reassessed at 5 weeks (4 weeks post-AAV delivery). Final echocardiographic and pressure-volume measurements were obtained to evaluate cardiac function and remodeling. Animals were euthanized, the heart was explanted, and different areas of the LV (Fig. 3A), as well as extra-cardiac tissues, were harvested for expression analysis. In vivo, study data analysis was not blinded due to technical difficulty in the presence of Impella, but tissue analyses were done by investigators blinded to the group allocation.

Gold nanoparticle study: Three other animals (35.7 ± 1.58.kg, female) similarly underwent MI at day 0 and one week later were assigned to injection of AAV-sized gold nanoparticles by either Continuous or Stop-flow delivery. After 30 minutes (n = 2 [Continuous and Stop-flow]) or 4 h (n = 1 [Stop-flow]) following gold nanoparticle delivery, hearts were explanted, perfused, and fixed in aldehydes. Remote and infarct tissue regions were further processed and analyzed by electron microscopy.

Animal model

For each time point in the study, animals were fasted overnight, sedated, and intubated under Telazol (6 mg/kg), and peripheral venous access was obtained. Mechanical ventilation was established, and anesthesia was maintained with propofol. Vital signs were continuously monitored and recorded at 5-minute intervals. For MI creation, normal saline with potassium acetate and amiodarone was set at a maintenance rate according to body weight. Echocardiography was performed before all invasive procedures to screen for abnormalities. In MI procedures, an additional dose of amiodarone was given intravenously and intramuscularly after echocardiography ahead of angiography. Vascular access was secured via a modified Seldinger technique for all catheter procedures. Initial heparin was given IV after primary vascular access and every hour afterward.

An anterior MI was created by 90-minute occlusion of the proximal to mid-LAD according to our well-established model37,38. A coronary balloon was advanced to the LAD though a 7 F guiding catheter and the location of balloon occlusion was balanced between individual animals’ anatomy. At 90 min, the balloon was deflated and animals were recovered after confirming hemodynamic stability. All the animals survived MI.

AAV delivery

Intracoronary delivery approaches: For delivery involving MCS, the Impella CP was first placed through femoral artery access, its position in the LV was confirmed under fluoroscopy, and the pump was run at maximum flow. Supplemental heparin was added before MCS placement as needed to maintain anticoagulant status.

Continuous delivery was conducted by advancing two coronary wires through a 7 F guiding catheter to the left main coronary artery and securing its position with one wire each in the LAD and LCx. The vector was slowly infused at a rate of 1 mL/minute.

In balloon occlusion delivery groups with MCS, a 7 Fr coronary guiding catheter was advanced to the left main artery, and a 3.5-4 mm coronary balloon was positioned in the proximal LAD (infarcted coronary artery). The balloon was inflated to 1-2 atm (to avoid vascular injury) three times at 15-s intervals for ischemic preconditioning. The balloon was then inflated to 1-2 atm three times for 90 s each for AAV6.Luc or gold nanoparticle injection (Stop-flow) or 15 s each for AAV6.Luc injection (Stop-flow, short). Each inflation was followed by a short recovery period until the blood pressure returned to baseline. The same process was subsequently repeated with the balloon positioned in the proximal LCx (non-infarcted coronary artery) at 60-s injections (Stop-flow) or 15-s (Stop-flow, short) injections, such that half of the total dose was delivered to each artery. In the Stop-flow groups, a coronary balloon was also guided into the coronary sinus from jugular venous access. Pressure rise in the coronary sinus was confirmed with balloon inflation just prior to delivery. Stable positioning of catheters and balloons was ensured under fluoroscopy during delivery. After AAV/gold nanoparticle Stop-flow delivery, the Impella was gradually weaned and removed.

Intramyocardial delivery: A left lateral thoracotomy was performed to expose the heart and identify the infarct region. Injections were administered with a 30-gauge needle bent at the tip into apex, infarct (anterior), border (lateral), and remote (posterior) areas. To ensure accurate collection of the tissues from the injection site, we placed a suture that stayed during the follow-up. Each injection site was immediately held after injection to avoid leakage.

Vector

AAV6.cmv.Luc (AAV6.Luc) was obtained from Virovek with vectors produced using the baculovirus expression system. The titer was confirmed by qPCR and alkaline gel analysis. AAV was prepared for delivery by diluting a total dose of 5.0 × 1013 vg into 6 mL half-normal saline and half contrast for Stop-flow and CAO and into 10 mL normal saline for Continuous deliveries. The same dose was diluted into 1 ml of normal saline and divided into two insulin syringes for injection of 100 μL/site for intramyocardial delivery. Gold nanoparticles (8.175 × 1012) were injected similarly as for AAV intracoronary injection.

Tissue harvest

At final time points, the heart was stopped by IV injection of high-dose potassium acetate (20 mEq) to induce VF under deep anesthesia with isoflurane while still under ventilation. Once lack of pulse was confirmed, the heart was explanted into cardioplegia, and each chamber was weighed. Each septum was kept in the respective left heart chamber. The LV was sectioned into 5-6 slices from apex to base. Each segment was weighed, and superior and inferior surfaces were photographed for infarct size analysis by standard planimetry, in which infarct areas were outlined relative to the areas of remaining myocardium and calculated as the percent of total LV mass, factoring in the weight of each slice. Slices remaining after frozen tissue collection were further stained in triphenyl tetrazolium chloride to emphasize the infarct area on gross analysis. For intracoronary delivery groups, LV tissues were sampled from apex, mid (infarct [anterior], infarct-border [border/lateral], posterior, septum), and base (lateral, septum) regions. Mid-posterior regions were further separated into epicardial and endocardial halves. The right ventricle (RV), left atrium (LA), right atrium (RA), left coronary artery (CA), lung, liver, spleen, kidney, skeletal muscle, and brain tissues were also collected. Tissues were frozen at − 80 °C for expression assays.

Echocardiogram analysis

Three-dimensional (3D) echocardiogram images were acquired and analyzed in apical 4-chamber view and 3D volumes and ejection fraction were determined using QLAB software (Ver 9.1. Philips iE33, Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA).

Hemodynamic measurements

Pressure data were obtained from a high-fidelity pressure catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) placed in the LV and recorded in iox2 software (version 10.8.34, Emka Technologies, Falls Church, VA). Cardiac output and stroke volume were derived from an average of at least three recordings by the thermodilution method using a Swan-Ganz catheter (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA). Each measurement was acquired under breath-hold.

Viral genome analysis

Frozen tissues were crunched and equal sample amounts were weighed out for viral genome (vg) quantification. Total DNA was extracted (Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, QIAGEN, Aarhus, Denmark), measured in NanoDrop, and probed for the CMV promoter of the AAV construct by qPCR (Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) (F: TGTACTGCCAAGTAGGAAAGTC; R: CCCACTTGGCAGTACATCAA). Beta-actin for sus scrofa was added as a housekeeping control (F: CGAGAGGCTGCCGTAAAGG; R: TGCAAGGAACACGGCTAAGTG) as an extra measure of equal loading (100 ng of total DNA). All kits were followed according to manufacturers’ instructions at recommended settings. qPCR was run by tissue with all samples per plate. Quantification of vg was derived from CMV Ct values using the standard curve generated by Ct values of a serially-diluted AAV reference standard (ATCC recombinant AAV2 VR-1616, ATCC, Manassas, VA). The limit of detection (LOD) for the standard was established at 100 vg/µL (“zero”) based on comparable Ct values at this dilution and the no template control. The LOD was determined as Ct(zero) – 1.645*SEM(zero). All values in vg/µL were converted to vg/mg of total DNA.

Luciferase expression

Crunched frozen tissue was weighed out (50 mg/sample) and incubated in 5x lysis reagent (Promega Cell Culture 5x Lysis Reagent, Promega, Madison, WI) diluted to 2x for 25 min at room temperature on a thermocycler at 700 rpm. The aqueous phase was recovered, and each sample lysate was distributed in triplicate at 20 µL per well on a white opaque 96-well plate. 100 µL of luciferase assay reagent39 was added to each well immediately before the plate reading (GloMax Plate Reader, Promega, Madison, WI). The total protein concentration of each lysate was measured by Pierce BCA (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) quantification. Luciferase enzyme was quantified by luciferase standard curve using QuantiLum recombinant luciferase (Promega, Madison, WI) in serial dilutions (including zero without luciferase) and normalized to total protein. The LOD was established as RLU(zero) + 1.645*SEM(zero), where RLU are relative light units.

RNAscope

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 4 µm. Slides were processed using the RNAscope 2.5 LS Duplex Assay (ACD Bio, Newark, CA) with corresponding probes for luciferase (#313408), positive (SsUBc, #400641) and negative (DapB, #320758) controls, with the BOND RX automated stainer (Leica Systems, Deer Park, IL) on the C1 green channel, according to each manufacturers’ instructions. Slides were subsequently scanned and imaged with the Aperio GT 450 (Leica Systems, Deer Park, IL) at 40x magnification and evaluated using QuPath software.

Electron microscopy

In the gold nanoparticle study, upon explant, the heart was perfused at the aortic root for 1 min with a light fixative flush (1% paraformaldehyde) and then perfused over 10 min with 2% paraformaldehyde/2% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for fixation. Infarct and remote areas were isolated, sized down, and kept in 2% aldehydes at 4 °C until electron microscopy processing.

Tissues for imaging were rinsed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (SCB), post-fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide/1.5% potassium ferricyanide in 0.1 M SCB, and en bloc stained with 2% uranyl acetate in distilled, deionized water. Tissue sections were dehydrated in an ethanol series (25% to 100%), infiltrated through an ascending ethanol/propylene oxide series, and placed in epoxy resin (“Embed 812”, Electron Microscopy Sciences (EMS), Hatfield, PA) overnight. Then samples were placed in BEEM capsules in a 60 °C vacuum oven for polymerization. The blocks were semithin-sectioned (0.5 and 1 µm) using an ultramicrotome and counterstained with 1% toluidine blue/water. Ultrathin sections at 80 nm were sectioned using a diamond knife (DiATOME, EMS, Hatfield, PA) and collected onto 300 mesh copper grids using a coat-quick adhesive pen. Images were taken on an HT7500 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) using an AMT NanoSprint12 12-megapixel CMOS TEM Camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA). Final image brightness, contrast, and size were adjusted using Adobe Photoshop CS4 software version CS4 11.0.1.

Statistics

Averaged data were represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was denoted at p < 0.05. Group data were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test between means of two-group comparison (with corresponding t-statistic, degree of freedom (df) = n – 1) or by Kruskal-Wallis test (H statistic) with Dunn’s posthoc test (adjusted p values, Z statistic) for multi-group comparison with unequal variances following the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Assay calculations were done in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA), and statistical analysis was completed in GraphPad Prism version 10.2.3 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Values below LOD were included in statistical calculations as LOD/√2. Correlation data was evaluated by Spearman’s correlation test (unequal variances). Confidence intervals and corresponding degrees of freedom were calculated using the Satterthwaite delta method for mean ratio comparison. The effect size for the Kruskal-Wallis test was determined by η2 [= (H – df + 1)/(n – k); df = n – 1, k = number of groups].

Pre-study sample size calculation was not made due to unclear effects of the intervention. The number of animals before tissue analysis was based on the availability of the vectors and the study budget.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Hemodynamic and expression data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file in Figshare under accession code 10.6084/m9.figshare.26499541. Inquiries can be addressed to the corresponding author: kiyotake.ishikawa@mssm.edu. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 147, e93–e621 (2023).

Ravichandran, A. J., Romeo, F. J., Mazurek, R. & Ishikawa, K. Barriers in heart failure gene therapy and approaches to overcome them. Heart Lung Circ. 32, 780–789 (2023).

Drouin, L. M. & Agbandje-McKenna, M. Adeno-associated virus structural biology as a tool in vector development. Future Virol. 8, 1183–1199 (2013).

Hajjar, R. J. et al. Modulation of ventricular function through gene transfer in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5251–5256 (1998).

Hadri, L. et al. SERCA2a gene transfer enhances eNOS expression and activity in endothelial cells. Mol. Ther. 18, 1284–1292 (2010).

Xin, W., Lu, X., Li, X., Niu, K. & Cai, J. Attenuation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related myocardial apoptosis by SERCA2a gene delivery in ischemic heart disease. Mol. Med. 17, 201–210 (2011).

Chamberlain, K., Riyad, J. M. & Weber, T. Cardiac gene therapy with adeno-associated virus-based vectors. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 32, 275–282 (2017).

Jaski, B. E. et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease (CUPID Trial), a first-in-human phase 1/2 clinical trial. J. Card. Fail. 15, 171–181 (2009).

Greenberg, B. et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in patients with cardiac disease (CUPID 2): a randomised, multinational, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet 387, 1178–1186 (2016).

Hulot, J. S., Ishikawa, K. & Hajjar, R. J. Gene therapy for the treatment of heart failure: promise postponed. Eur. Heart J. 37, 1651–1658 (2016).

Ertl, H. C. J. Immunogenicity and toxicity of AAV gene therapy. Front. Immunol. 13, 975803 (2022).

Shen, W., Liu, S. & Ou, L. rAAV immunogenicity, toxicity, and durability in 255 clinical trials: A meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 13, 1001263 (2022).

Lek, A. et al. Death after high-dose rAAV9 gene therapy in a patient with duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 389, 1203–1210 (2023).

Donahue, J. K., Kikkawa, K., Johns, D. C., Marban, E. & Lawrence, J. H. Ultrarapid, highly efficient viral gene transfer to the heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 4664–4668 (1997).

Emani, S. M. et al. Catheter-based intracoronary myocardial adenoviral gene delivery: importance of intraluminal seal and infusion flow rate. Mol. Ther. 8, 306–313 (2003).

Verma, S., Burkhoff, D. & O’Neill, W. W. Avoiding hemodynamic collapse during high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: Advanced hemodynamics of impella support. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Inter. 89, 672–675 (2017).

Dangas, G. D. et al. Impact of hemodynamic support with Impella 2.5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump on prognostically important clinical outcomes in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (from the PROTECT II randomized trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 113, 222–228 (2014).

O’Neill, W. W. et al. Improved outcomes in patients with severely depressed LVEF undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with contemporary practices. Am. Heart J. 248, 139–149 (2022).

Uriel, N., Sayer, G., Annamalai, S., Kapur, N. K. & Burkhoff, D. Mechanical unloading in heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 569–580 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Comparative study of catheter-mediated gene transfer into heart. Chin. Med. J. 115, 612–613 (2002).

Zhang, H., Zhan, Q., Huang, B., Wang, Y. & Wang, X. AAV-mediated gene therapy: Advancing cardiovascular disease treatment. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 952755 (2022).

Hajjar, R. J. & Ishikawa, K. Introducing genes to the heart: All about delivery. Circ. Res. 120, 33–35 (2017).

Zeitouni, M. et al. Prophylactic mechanical circulatory support use in elective percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Inter. 15, e011534 (2022).

Au, H. K. E., Isalan, M. & Mielcarek, M. Gene therapy advances: A meta-analysis of AAV usage in clinical Settings. Front. Med. 8, 809118 (2021).

Vinogradov, A. E. Genome size and GC-percent in vertebrates as determined by flow cytometry: the triangular relationship. Cytometry 31, 100–109 (1998).

Li, J. et al. Distribution of cardiomyocyte-selective adeno-associated virus serotype 9 vectors in swine following intracoronary and intravenous infusion. Physiol. Genom. 54, 261–272 (2022).

Myers, V. D., Landesberg, G. P., Bologna, M. L., Semigran, M. J. & Feldman, A. M. Cardiac transduction in mini-pigs after low-dose retrograde coronary sinus infusion of AAV9-BAG3. A Pilot Study JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 7, 951–953 (2022).

Kishimoto, T. K. & Samulski, R. J. Addressing high dose AAV toxicity - ‘one and done’ or ‘slower and lower’? Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 22, 1067–1071 (2022).

Shi, W. et al. Ischemia-reperfusion increases transfection efficiency of intracoronary adenovirus Type 5 in pigheart In Situ. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 23, 204–212 (2012).

Vekstein, A. M. et al. Targeted delivery for cardiac regeneration: Comparison of intra-coronary infusion and intra-myocardial injection in porcine hearts. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 833335 (2022).

Keith, M. C. et al. Effect of the stop-flow technique on cardiac retention of c-kit positive human cardiac stem cells after intracoronary infusion in a porcine model of chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. Basic Res. Cardiol. 110, 503 (2015).

Lampela, J. et al. Caridac vein retroinjections provide an efficient approach for global left ventricular gene transfer with adenovirus and adeno-associated virus. Sci. Rep. 14, 1467 (2024).

Beeri, R. et al. Gene delivery of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase inhibits ventricular remodeling in ischemic mitral regurgitation. Circ. Heart Fail 3, 627–634 (2010).

Raake, P. W. et al. Cardio-specific long-term gene expression in a porcine model after selective pressure-regulated retroinfusion of adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors. Gene Ther. 15, 12–17 (2008).

Boekstegers, P. et al. Myocardial gene transfer by selective pressure-regulated retroinfusion of coronary veins. Gene Ther. 7, 232–240 (2000).

Raake, P. W. et al. AAV6.betaARKct cardiac gene therapy ameliorates cardiac function and normalizes the catecholaminergic axis in a clinically relevant large animal heart failure model. Eur. Heart J. 34, 1437–1447 (2013).

Bikou, O., Watanabe, S., Hajjar, R. J. & Ishikawa, K. A pig model of myocardial infarction: Catheter-based approaches. Methods Mol. Biol. 1816, 281–294 (2018).

Ishikawa, K. et al. Characterizing preclinical models of ischemic heart failure: differences between LAD and LCx infarctions. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 307, H1478–1486, (2014).

Ravichandran, A. J., Mazurek, R. & Ishikawa, K. Cell-based determination of neutralizing antibodies against adeno-associated virus in cardiac gene therapy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2573, 293–304 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R01 HL139963, R01 HL173593 (K.I.), and an Abiomed-sponsored research grant to the institution. S.A.M. was supported by the National Institutes of Health T32HL007824-23. We would like to acknowledge the Gene Therapy Resource Program (GTRP) of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, for providing the gene vectors used in this study. For electron microscopy at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, we would like to acknowledge Allison Sowa and William Janssen of the Microscopy and Advanced Bioimaging CoRE for processing and image analysis and Dr. Ronald Gordon at the Department of Pathology for contributing expert opinion. For RNAscope at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, we would additionally like to acknowledge Dr. Claudia De Sanctis and the Neuropathology Brain Bank and Research CoRE. We would like to acknowledge the equipment funding from NIH on the animal catheterization lab C-arm (S10OD034330).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M., S.T., S.A.M., D.T.S., O.B., T.S., T.K., K.Y., E.K., L.L, A.J.R., S.W., R.J.H., and K.I. contributed to investigation and review and editing of the final draft. In addition, R.M. contributed to data curation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, and writing the original draft. S.T. and S.A.M. contributed to formal analysis and visualization. D.T.S. and O.B. contributed to data curation and formal analysis. T.K. and K.Y. contributed to data curation. R.J.H. contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, and supervision. K.I. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, visualization, and writing the original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Part of this study was supported by a research grant from Abiomed, Inc. to the institution. K.I. serves as the principal investigator on the grant from Abiomed, Inc. K.I. received an honorarium from Abiomed, Inc. and served as a consultant for Pfizer, Inc., and Gordian Biotechnology. T.S. and T.K. were supported by A-CURE Research Fellowship supported by Abiomed, Inc.. K.I. and R.J.H. have a patent, “SYSTEMS AND METHODS FOR LEFT VENTRICULAR UNLOADING IN BIOLOGIC THERAPY OR VECTORED GENE THERAPY” Publication number: 20200305888. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Oliver Muller, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mazurek, R., Tharakan, S., Mavropoulos, S.A. et al. AAV delivery strategy with mechanical support for safe and efficacious cardiac gene transfer in swine. Nat Commun 15, 10450 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54635-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54635-x

This article is cited by

-

Cardiac epigenome in heart development and disease

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2026)

-

Cardiac gene therapy makes a comeback

Nature Medicine (2025)

-

Gene Therapies in Atrial Fibrillation

Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research (2025)