Abstract

Thermophilic microbial communities growing in low-oxygen environments often contain early-evolved archaea and bacteria, which hold clues regarding mechanisms of cellular respiration relevant to early life. Here, we conducted replicate metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, microscopic, and geochemical analyses on two hyperthermophilic (82–84 °C) filamentous microbial communities (Conch and Octopus Springs, Yellowstone National Park, WY) to understand the role of oxygen, sulfur, and arsenic in energy conservation and community composition. We report that hyperthermophiles within the Aquificota (Thermocrinis), Pyropristinus (Caldipriscus), and Thermoproteota (Pyrobaculum) are abundant in both communities; however, higher oxygen results in a greater diversity of aerobic heterotrophs. Metatranscriptomics revealed major shifts in respiratory pathways of keystone chemolithotrophs due to differences in oxygen versus sulfide. Specifically, early-evolved hyperthermophiles express high levels of high-affinity cytochrome bd and CydAA’ oxidases in suboxic sulfidic environments and low-affinity heme Cu oxidases under microaerobic conditions. These energy-conservation mechanisms using cytochrome oxidases in high-temperature, low-oxygen habitats likely played a crucial role in the early evolution of microbial life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atmospheric levels of oxygen in the Archaean are thought to have been negligible ranging from 10−5 to 10−6 of present-day atmospheric levels1. Early microbial metabolisms involving methane and other single-carbon compounds may have relied on respiration using sulfate, nitrate, or ferric iron2,3,4,5. Although the rise of atmospheric oxygen during the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) commencing circa 2.5 Gya6,7 caused extensive radiation of aerobic microorganisms and eukaryotes8,9, the role of oxygen in microbial metabolism prior to the GOE is uncertain.

Recent studies on the evolution of oxygen utilizing enzymes by microorganisms10 provide phylogenetic evidence of microbial oxygen metabolism well before the GOE. These results are consistent with other geochemical studies that indicate the importance of oxygen in ancient biosignatures that predate the GOE, such as microaerobic steroid biosynthesis11, transition metal anomalies12, or micrometeorite analysis in the Archaean13. Numerous oxygen reductases are present and function in hyperthermophilic bacteria and archaea including heme Cu oxidases (HCOs; types 1, 2, and 3), cytochrome bd (ubiquinol) oxidases and the CydAA’ oxidases14,15,16,17,18,19. Type 3 (cbb3) HCOs and cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidases have high affinities for oxygen and can support aerobic growth at nanomolar levels of oxygen20 even in the presence of high sulfide21,22. Therefore, thermal habitats containing high sulfide and/or low levels of oxygen are extremely relevant to environments likely common prior to the GOE when atmospheric oxygen concentrations were significantly lower than modern levels1,6,7,12.

Filamentous communities residing in the outflow channels of alkaline (pH 8-9) chloride geothermal springs rely on attachment in high-velocity (~0.2 m s−1) outflow channels to capitalize on the chemical energy available as highly reduced fluids mix with oxygen21,23,24,25. Variable levels of dissolved sulfide (DS) in different alkaline springs represent natural laboratories for testing hypotheses focused on microbial respiration under low-oxygen conditions at similar pH and temperature. Our objectives were to examine the genomics of chemolithotrophic electron transfer processes responsible for the growth and activity of thermophilic microorganisms in two filamentous ‘streamer’ communities thriving under different levels of DS versus DO. ‘Streamer’ is used here to define microbial communities that contain dominant filamentous members attached to solid substrates in high-velocity currents. Integrated and replicated genomic, transcriptomic, geochemical, and microscopic analyses were performed for nearly 10 years at two alkaline-chloride springs in YNP to elucidate microbial community structure and function under microaerobic (40–50 µM DO) versus sulfidic (~100 µM DS) conditions. Here we show that despite differences in DS and DO, several microbial populations including Thermocrinis, Pyrobaculum and Caldipriscus (a member of the early-evolved Pyropristinus lineage) are abundant in each habitat. However, the primary mechanisms of energy conservation and respiration vary under sulfidic (sub-oxic) versus microaerobic conditions. These results have important implications for the effect of oxygen concentrations on microbial community function and biogeochemical cycling under microaerobic and suboxic conditions, at temperatures often considered too high to support aerobic metabolism.

Results and Discussion

Geochemistry and microbial community composition

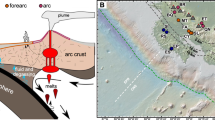

Two alkaline-chloride geothermal springs (Conch and Octopus Springs) with similar geochemical profiles (Table 1) were chosen for this study to provide a direct comparison between geothermal habitats with contrasting levels of DS and DO (Figs. 1 and 2). Both springs discharge near-boiling water (~90°C at 2500 m) but Conch Spring is highly sulfidic (>120 µM DS) with no detectable oxygen (<1 µM), while Octopus Spring contains ~20 µM DO and low DS (<2-3 µM) at the source. DO concentrations increase quickly in the Octopus Spring outflow channel due to oxygen ingassing, and within several meters, DO concentrations reach 40–50 µM at streamer sampling sites (Fig. 2), which is approximately 30% of oxygen saturation at 80 °C and 2500 m (~130 µM).

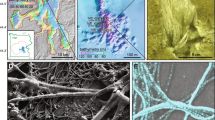

A Conch Spring B Octopus Spring (Lower Geyser Basin, YNP). Scanning electron micrographs show filamentous organisms and extensive extracellular matrix (high-resolution insets) that dominate the physical fabric of both communities. Micrographs were chosen from a large collection of over 30 replicates from 3 different sample years and a minimum of 10 replicate images per year.

Filamentous communities were sampled down-gradient of spring discharge at transect position B, C (82–84 °C) for metagenomic and transcriptomic analyses (DS was <1 μM in Octopus Spring and DO <1 μM in Conch Spring). Error bars are standard deviations of 4–6 replicates, where absent, error bars fall within symbol. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Both streamer communities contain highly abundant populations of Thermocrinis (Aquificota), Pyrobaculum (Thermoproteota), and Caldipriscus (Pyropristinus) genera (Fig. 3). Together, these three keystone populations comprise from ~ 50% to > 90% of the Octopus and Conch microbial communities, respectively. However, the other abundant community members were unique to each habitat type: Conch Spring is less diverse and contains only 3-4 additional microbial populations while Octopus communities contained greater diversity for a total of ~ 15 different populations (Fig. 3, Table 2). Microorganisms present in Conch Spring but not in Octopus included Thermodesulfobacteriaceae, Thermosphaera, and several members of the Desulfurococcales. Conversely, Octopus Spring contained ~10 populations not seen in Conch Spring and these included additional early-evolved bacteria as well as additional archaea. Both habitats also contain low amounts (<1 % abundance) of very similar populations of Thermus aquaticus, Nanopusillus and Acidilobaceae (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1). The strong reproducibility in population abundances in 2011 and 2012 (Supplementary Fig. 1) as well as the consistent compositional differences between Conch and Octopus Springs are also evident in tetranucleotide frequency t-SNE plots (Supplementary Figs. 2–4).

Organisms common to both sites include Thermocrinis, Pyrobaculum, and Caldipriscus (Pyropristinus) (hatched). Other populations (clockwise, in order of abundance) include Thermodesulfobacteria and 2 members of the Desulfurococcales at Conch Spring (yellow patterns), and Thermoproauctor, Calescibacterium (Calescamantes), Armatimonadota T1, Calditenuis aerorhuemensis 59, Acidilobaceae, Armatimonadota T2, Thermoflexus, and several others <2% at Octopus Spring (blue patterns) (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1 show complete list of phylotypes). Abundances were calculated based on the fraction of mapped reads from random metagenome sequence (CheckM61). Taxonomic references are based on nucleotide identity (>95%) at either the phylum, order, family, or genus/species level. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Phylogenetics of early-evolved thermophiles

A bacterial phylogeny based on a standard group of 16 ribosomal proteins (Fig. 4A) shows that the Pyropristinus lineage is the most deeply rooted bacterial group independent of the Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR)26. The Pyropristinus lineage also includes the WOR-like populations described in the Genome Taxonomy Database27 (GTDB) (Fig. 4A). A bacterial phylogeny based on the 16S rRNA sequence (Fig. 4B) also shows that Caldipriscus and Thermoproauctor represent two separate branches within the Pyropristinus lineage28, each branching deeper than the Aquificota and Thermotogota24. In summary, both microbial communities contain several early-evolved bacterial lineages including the Pyropristinus, the Aquificota, and the Calescibacteria. Functional traits of these groups may provide insight into the activities of microorganisms thought to have been important in early life4,29.

Bayesian phylogenetic trees of Bacteria using A a concatenation of 16 ribosomal proteins (2447 residues) or B the 16S rRNA gene (sequences > 1000 bp only). Members of the Pyropristinus lineage include Caldipriscus and Thermoproauctor spp. from circumneutral (pH 7–9) hyperthermal (>75 °C) geothermal springs [OCT Octopus Spring, CON Conch Spring, BCH Bechler, FF Fairy Falls, PS Perpetual Spouter; *16S rRNA clones EM3 and EM19 from Octopus Spring 23; ** lineages contain populations from Octopus Spring (e.g., Patescibacteria within Candidate Phyla Radiation26 (CPR) (2 types, OCT 2012), Thermus aquaticus OCT 2011, 2012, Thermoflexus hugenholtzii OCT 2011, 2012) or Conch Spring (Thermodesulfobacteria); Uncollapsed versions of these phylogenetic trees are provided in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6.

Geochemical forcing: Impacts on functional genomics

The geochemical conditions in Conch and Octopus Springs are linked to differences in the distribution of key functional genes that regulate electron transfer reactions involving arsenic, sulfur, and oxygen. Keystone populations present in these alkaline (pH 8-9) habitats included Thermocrinis, Pyrobaculum and Caldipriscus, and although the metabolic potential of each of these organisms was highly similar between the two habitats, there were several notable exceptions (Fig. 5). For example, Pyrobaculum populations in Octopus Spring contained an arsenite oxidase (Aio) and HCO complex, while these genes were completely absent in the Pyrobaculum from Conch Spring. Caldipriscus populations also contained a type 1 HCO but only the population from Conch Spring contained a cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase (Cyt bd), known to be a high-affinity oxygen reductase20 as well as a sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase (Sqr) that is important in the oxidation of sulfide30. Thermocrinis, the predominant population in both communities, exhibited similar metabolic potential in each habitat, including the oxidation of thiosulfate (Sox complex) and arsenite (Aio) using oxygen as an electron acceptor (HCO). However, as will be shown, the actual transcription of these genes was remarkably different between sulfidic and microaerobic environments. A broader look at energy-related genes using hierarchal clustering (Supplementary Fig. 7) shows similar results, and high reproducibility between each of the phylotypes found in both habitats (i.e., Thermocrinis, Pyrobaculum, Caldipriscus). Thermocrinis populations in both environments contained a convincing set of genes necessary for the synthesis and use of flagella (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Keystone microbial populations present in both springs (A), or populations present only in Conch (B) or only in Octopus (C) Springs [sox sulfur oxidation pathway, aio arsenite oxidase, sqr sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase, ttr tetrathionate reductase, psr polysulfide reductase, dsr dissimilatory sulfite/sulfate reductase, hco heme Cu oxidases, cytbd cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase, cydAA’ archaeal cytochrome oxygen reductase, ccl/ccs citryl-CoA lyase/citryl-coA synthetase, fdh formate dehydrogenase, acc acetyl CoA carboxylase, por pyruvate oxidoreductase].

Dissolved sulfide and oxygen concentrations affect the overall community composition in each geothermal habitat, as well as the metabolic attributes of additional community members (Fig. 5). For example, higher sulfide levels in Conch Spring result in lower microbial diversity and select for organisms that are known to prefer suboxic conditions (DO < 1 µM) such as organisms within the Thermodesulfobacteria31 and Thermosphaera32. These populations also contain higher affinity oxygen reductases including the cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase (bacteria) and cytochrome AA’ oxidase (archaea)18. Moreover, the number of genes potentially involved in the oxidation of sulfide (Sqr), the reduction of sulfur compounds (Ttr, Psr, Dsr) and the reduction of nitrate (NarG) were notably higher in the sulfidic (and suboxic) Conch Spring (Fig. 5B). The Thermodesulfobacteriaceae in Conch Spring was the only population with a nearly complete set of genes necessary for dissimilatory sulfate reduction33. Pyrobaculum populations from both springs contain DsrAB, but lack other major proteins required for sulfate reduction. The complete absence of Thermoproauctor, Calescibacterium, Calditenuis, and other heterotrophs under sulfidic conditions (Conch Spring) is likely due to the lack of a high-affinity cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase and/or direct toxicity from sulfide.

Conversely, the microbial community in Octopus Spring was more diverse, which is attributable to higher levels of DO ranging from 40–50 µM (Fig. 2). Specifically, genes required for oxygen respiration using type 1 HCO complexes were present in nearly all the microorganisms from Octopus Spring (Fig. 5C). Most of the additional organisms in Octopus Spring are heterotrophic, as evinced by the absence of chemolithotrophic markers (e.g., Fig. 5C) and high gene counts of a diverse suite of carbohydrate degrading enzymes (Supplementary Fig. 9). Numerous glycosyltransferases (e.g., families GT4, GT5, GT9 of the CAZy database34), glycoside hydrolases (family GH109), and carbohydrate binding modules (e.g. family CBM50) were observed in Armatimonadota (types 1 and 2), Calescibacteria and Themoflexus populations, respectively.

The keystone populations common to both habitats have genes necessary for the fixation of carbon dioxide via either the reverse TCA cycle (primarily Thermocrins, e.g., ccl/ccs = citryl-CoA lyase/citryl-coA synthetase24) or other carboxylases (e.g., acc = acetyl coA carboxylase; por = pyruvate oxidoreductase) (Fig. 5). This is consistent with stable-isotope (13C) analyses, which revealed high levels of CO2 fixation in both communities35. In fact, microbial biomass from Conch Spring originates nearly entirely (>90%) from the fixation of CO235, which correlates with the large fraction of primary autotrophs Thermocrinis, Pyrobaculum, and Caldipriscus (up to 90%, Fig. 3). Conversely, the presence of numerous aerobic heterotrophs in Octopus Spring explains 13C-biomass values that reveal a greater fraction of microbial biomass (up to 40%) acquired via dissolved organic carbon35. Consequently, higher oxygen levels in Octopus Spring select for a more diverse, aerobic, and heterotrophic microbial community than present in the highly sulfidic Conch Spring, where DO levels were below detection (<1 µM).

Finally, the acquisition of sufficient Fe can be problematic in high pH environments due to the low solubility of ferric iron solid phases. Concentrations of dissolved Fe in Conch and Octopus Springs were below detection using ICP-OES (~1 µM) and numerous phylotypes in these habitats showed genomic capabilities for enhanced Fe transport, siderophore production, as well as Fe gene regulation (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). No evidence of Fe reduction and/or Fe oxidation existed in these communities, which is consistent with low dissolved Fe as well as the absence of any Fe solid phases.

Metatranscriptomics: Energy conservation and respiration

Thermocrinis, Pyrobaculum and Caldipriscus MAGs accounted for ~80–90 % of the total transcript sequence mapped to community populations from Conch and Octopus Springs (Fig. 6A). Metatranscriptomes from Octopus Spring (years 2011 and 2016) were highly similar (p < 0.01), and the fraction of transcripts mapped to Thermocrinis, Pyrobaculum and Caldipriscus was notably consistent (also see Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). The large number of transcripts mapped to these highly abundant and active populations provided sufficient coverage to evaluate the activity of numerous cellular processes (Supplementary Data 1–3).

A Transcript abundance by major phylotype (Octopus 2011 solid blue, Octopus 2016 hatched blue, Conch 2016 hatched yellow). B Abundance of transcripts mapped to specific functions within Thermocrinis, Pyrobaculum, and Caldipriscus metagenome assembled genomes (MAGs), expressed as a percent of total transcripts within each MAG. [Armatimona. T1 Armatimonadota type 1, aio arsenite oxidase, sox sulfur oxidation complex, hco heme Cu oxidase complex subunits I, II and III, cytBC cytochrome bc complex, rhod rhodanese sulfur transferase, sqr sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase, cytBD cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase; cydAA’ = archaeal cytochrome oxidase, por pyruvate ferrodoxin oxidoreductase complex, hgl hemoglobin. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The ratio of DS to DO ranges from > 100 in Conch Spring to <0.025 in Octopus Spring, a factor of approximately 4000 times. Transcript abundances of genes involved in energy conservation and electron transport revealed several major shifts in metabolism consistent with this large difference in sulfide: oxygen ratio (Fig. 6B). Thermocrinis arsenite oxidase (Aio) and sulfur oxidase (Sox) complexes were highly transcribed (4–5% of transcripts) in Octopus Spring yet these same genes were not expressed in Conch Spring. Arsenite oxidases were also highly transcribed (~2% of transcripts) in Pyrobaculum populations in Octopus Spring, yet these transcripts were completely absent in Conch Spring despite nearly identical levels of total soluble arsenic (Table 1). Moreover, the type 1 HCOs of Pyrobaculum, along with associated cytochrome bc complexes were only transcribed in Octopus Spring (> 1% of transcripts), which indicates that oxygen is serving as an electron acceptor for the oxidation of arsenite and generation of ATP36.

The large fraction of transcripts consistently mapped to Thermocrinis and Pyrobaculum AioAB genes indicates the importance of arsenite as a critical energy source for chemolithoautotrophs under non-sulfidic, microaerobic conditions (Fig. 7). Arsenite oxidases were previously shown to be expressed in several Aquificales-dominated filamentous communities using reverse transcriptase-PCR36, especially in non-sulfidic geothermal channels. Moreover, Thermocrinis ruber was cultivated from Octopus Spring37 and has been shown to oxidize arsenite aerobically in pure culture38. The Sox sulfur oxidation pathway was also highly expressed in Thermocrinis, but only in Octopus Spring where 4–5% of Thermocrinis transcripts were mapped to the Sox genes, including subunits SoxA, SoxB, SoxX, SoxY and SoxZ (Fig. 7). No SoxCD was observed in the Thermocrinis Sox complex, which suggests that thiosulfate is partially oxidized to S and sulfate39. The Thermocrinis Sox complex was not expressed in Conch Spring where high sulfide: oxygen ratios favored Sqr proteins (Fig. 6).

Ratios of DS:DO were nearly 4000 times higher at sample sites in Conch versus Octopus Springs. [Gene names: sqr = sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase, cytBD = bd-type ubiquinol cytochrome oxidase; cydAA’ = archaeal cytochrome oxidase; sox = sulfur oxidation complex including subunits soxA, soxB, soxX, soxY, and soxZ; aioAB = arsenite oxidase large and small subunits; HCO = heme Cu oxidase complex subunits I, II and III; and energy generating ATPase subunits a, b, and c.].

High-affinity oxygen reductases including the cytochrome bd ubiquinol (Caldipriscus) and cytochrome CydAA’ oxidases (Pyrobaculum)18 were highly transcribed in Conch Spring, indicating a major shift in energy metabolism yet still dependent on oxygen (Figs. 6 and 7). The CydAA’ cytochromes have recently been shown18 to serve as bona fide oxygen reductases and are important in numerous archaea17,40. Expression of the high-affinity cytochrome bd ubiquinol and CydAA’ oxidases occurred when DO levels were below detection (<1 µM) and likely in the nanomolar range. The HCOs of Caldipriscus and Thermocrinis were over-expressed in Conch Spring, along with increased levels of the cytochrome bc complex compared to Octopus Spring. Sqr proteins implicated in the oxidation of sulfide30 were only expressed significantly in Conch Spring (Fig. 7), as well as rhodanese sulfur transferase domains and an oxygen-binding hemoglobin gene (Thermocrinis). The major shifts in respiration pathways observed for these keystone populations reveal a tight linkage between the availability of oxygen and the metabolic strategies employed for energy conservation.

Type IV filaments: Microbial community attachment

One of the most noticeable features of high-temperature filamentous streamer communities is the surprising abundance of extracellular structures resembling pili with diameters of ~ 20–25 nm (Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. 14). Numerous genes important in the synthesis, secretion and function of type IV filament (Tff) machinery41,42,43 were highly expressed in Thermocrinis populations in both Conch and Octopus Spring (Fig. 8). Genes involved in Tff production and activity were found on two different contigs and were observed in numerous metagenomes as well as Thermocrinis ruber, which was isolated from Octopus Spring 37. Piliation can serve multiple functions including natural transformation through DNA uptake, export of filamentous phages, protein secretion, adhesion, and electron transport41,42,43,44,45.

Highly expressed type four filament (Tff) systems in Thermocrinis MAGs (A) likely explain the extensive network of pili-like structures (~20–25 nm diameter) commonly observed in filamentous streamer communities from Conch Spring (B) and Octopus Spring (C). [Abbreviations and Definitions: Bechler 2008 = Thermocrinis entry from Bechler Spring, YNP24. Arrows in C indicate Tff structures versus cells. [pilA = Type IV pilus assembly, pilW = Type IV pilus assembly, pulG = Type II secretory pathway, fimT = Type IV fimbrial biogenesis, pilY = adhesin; nfuA = Fe-S biogenesis, pilQ = pilus secretin, recJ = ssDNA exonuclease, HCO = heme copper oxidase complex subunits I, II, and III. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Micrographs shown in B and C were chosen from a large collection of over 30 replicates from 3 different sample years and a minimum of 10 replicate images per year. Additional FE-SEM micrographs are provided in Supplementary Fig. 14. Complete tables of observed transcripts and expression levels are provided in Supplementary Data 1–3].

Very high transcript levels of pilA (1.3 to 5.8% of transcripts) and nfuA (0.6 to 2.5% of transcripts) in Thermocrinis confirm the microscopic evidence that large amounts of cellular resources and carbon are being directed to the formation and maintenance of an extensive Tff network (Fig. 8). PilA is the protein comprising actual major pilin structure43 and NfuA is an Fe/S assembly protein used in maturation and repair of Fe-S proteins, which is often associated with electron transport and Fe stress46,47. Genes for the fixation of inorganic carbon (citryl co-A lyase and citryl-CoA synthetase/succinyl-CoA synthetase)24 were also highly expressed in Thermocrinis (up to 0.1 % of transcripts in Conch Springs). We have shown using 13C isotope analyses that autotrophically fixed inorganic carbon (CO2) is a very significant fraction (i.e., 50- > 90 %) of the total biomass carbon in both communities35. In fact, the percent of biomass originating from CO2 is highly correlated with the fraction of keystone populations in each community (e.g., Fig. 3). Ultimately, the energy required to reduce significant amounts of inorganic carbon and form extensive Tff systems comes from the oxidation of arsenite and reduced sulfur species (i.e., sulfide, polysulfide(s), and/or thiosulfate).

Type IV filament systems are central to several processes important in the colonization and survival of Thermocrinis in turbulent, high-velocity (~0.2 m s−1) geothermal outflow channels. Firstly, adhesion to solid substrates is an absolute prerequisite for attachment and growth of filamentous streamer communities (Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). PilY, which was transcribed by the ‘Pil’ operon in Thermocrinis (Fig. 8) is a known adhesin protein shown to be important in bacterial attachment to surfaces48. Secondly, ‘pilin’-like structures can be conductive and promote electron transfer reactions. Evidence obtained here shows that the HCO complex (subunits I, II and III) are located near the nfuA and pilQ and were co-transcribed in Thermocrinis populations from Conch Spring (Fig. 8). Finally, the actual secretin (pilQ)49 in Thermocrinis was also conserved across numerous metagenome entries and present in Thermocrinis ruber.

Early-evolved thermophiles: Relevance to early metabolisms

Low-oxygen environments were undoubtedly very important under early-Earth conditions6 prior to the GOE. Early-evolved thermophiles provide clues for understanding how early microbial lineages may have harnessed low levels of oxygen in extreme environments. Alkaline-chloride filamentous communities contain several major lineages of aerobic thermophilic bacteria including the Aquificota24, two representatives of the Pyropristinus lineage (Caldipriscus and Thermoproauctor 28), the Calescibacteria (Calescibacterium) as well as two novel aerobic organisms distantly related to members of the Armatimonadota shown in the GTDB27. Each of these aerobic lineages, including the Pyropristinus, Aquificota and Calescibacteria (and to a lesser extent, Armatimonadota) occupy deep phylogenetic positions (e.g., Fig. 4). The monophyletic HCO genes within these lineages is consistent with the hypothesis that oxidases were important in the early evolutionary history of archaea and bacteria. Protein modeling of the subunit I HCO (Supplementary Fig. 15) present in Caldipriscus and Thermoproauctor (Pyropristinus lineage) as well as for Thermocrinis and Pyrobaculum indicate that these proteins are all type 1 HCOs (Supplementary Table 4) expected to reduce oxygen and create proton motive force driving the production of ATP50.

Arsenite oxidase has also been considered an ancient bioenergetic protein, which existed prior to the divergence of archaea and bacteria51,52. Moreover, arsenite may have served as an electron donor for anoxygenic phototrophy in the early Archaean53. Indeed, in the current study, both Thermocrinis and Pyrobaculum (bacteria and archaea, respectively) obtain energy for metabolism using arsenite as an electron donor under low-oxygen conditions. However, high levels of sulfide suppress the oxidation of arsenite, which may be due to a combination of a stronger donor via Sqr proteins and/or oxygen limitation due to high sulfide: oxygen ratios.

The discharge of reduced geothermal and/or hydrothermal fluids creates complex mixing environments where turbulence and gas-exchange (e.g., oxygen, sulfide) converge to create optimum habitats for filamentous chemolithoautotrophs24,54. These same processes were likely critical in hydrothermal environments thought to be important on an early Earth4,29. The solubility of oxygen in water is approximately 2 times lower at 75–80 °C versus 25 °C. However, oxygen reduction by relevant electron donors is highly exergonic even under nanomolar levels of oxygen54, which have been shown to support microbial aerobic respiration using high-affinity oxygen reductases14,18,20, even in the presence of sulfide21,22. Transcriptomic measurements reported here provided sufficient resolution to understand the in situ physiology of three keystone populations, which were important in both communities but exhibited major metabolic shifts due to changes in sulfide and oxygen concentrations. Type I terminal oxidase complexes were highly expressed under microaerobic conditions and contributed to extensive heterotrophic microbial diversity. Conversely, high-affinity oxygen reductases including both the cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidases (Caldipriscus) and the cytochrome CydAA’ oxidase (Pyrobaculum) were highly expressed under sulfidic conditions where DO levels were below detection (<1 µM), and likely in the nanomolar range. Both geothermal habitats have unique relevance to possible geochemical circumstances prior to the GOE and indicate the metabolic resilience of early-evolved thermophiles to low-oxygen conditions.

Methods

Geothermal sites

Research in YNP was conducted under National Park Service Research Permits YELL-2011/2012/2014/2016-5068. Conch Spring and Octopus Spring (Fig. 1) are in Lower Geyser Basin, YNP; these alkaline-chloride (siliceous) springs exhibit similar geochemistry except for DO and DS (Table 1, Fig. 2), and have been stable geothermal sampling sites for many years23. Filamentous streamer communities thrive within the outflow channels down-gradient of spring discharge across temperatures from ~86 to 75 °C. The microbial communities emphasized in this report were sampled from a narrow temperature range of 82–84 °C in both springs, which provided a unique opportunity to focus solely on the effects of specific geochemical properties on microbial community structure and function. Aqueous samples were filtered on site (0.2 µm) and analyzed using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) and ion chromatography (IC). DS, DO, soluble ferrous/ferric Fe and pH were determined on-site immediately upon sampling. Total ferrous versus ferric Fe was determined using ferrozine colorimetry55. DS was determined using a modified diamine-sulfuric acid procedure56 where absorbance values (λ = 664 nm) were determined in the field and calibrated in the laboratory using iodometric titration. DO was determined using a modified Winkler method56,57, to avoid sample exposure to atmospheric oxygen. Briefly, a 60-mL aqueous sample with zero headspace was sealed with a rubber septum and immediately treated with 0.4 mL of 2.15 M MnSO4 and 0.4 mL of alkali-iodide-azide solution (12 M NaOH, 0.87 M KI, 0.15 M NaN3), respectively, through the septa. The sample was inverted 3 times to mix the suspension and allowed to equilibrate for 3–5 min, repeated, then 0.4 mL of concentrated H2SO4 was added via another syringe. The 60-mL sample was inverted until the floc dissolved, then 30 mL of the mixture was titrated (with replication) with sodium thiosulfate (0.01 M) to quantify DO. The detection limit for DO using these procedures was ~1 µM. DO measurements in streamer communities using glass microelectrodes58 could not be obtained because the small-diameter glass tips (~100 um) break immediately due to shear forces created by rapid streamer oscillation in the current (Supplementary Videos 1 and 2).

Elemental analysis and electron microscopy

Subsamples of filamentous streamer biomass were aseptically transferred and fixed in situ using 2% glutaraldehyde for subsequent microscopic and elemental analysis in the Imaging and Chemical Analysis Laboratory (Montana State University). Biomass samples were mounted and washed with sterile DI H2O on 13 mm-diameter 0.2 µm polycarbonate filters (Millipore), then powder-coated with Ir prior to imaging using a Zeiss SUPRA 55VP field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM).

DNA extraction, metagenome sequencing, and metatranscriptomics

Subsamples (approximately 2−5 g) of filamentous streamer communities were aseptically transferred from the outflow channels of Conch and Octopus Springs, placed on dry ice, then stored at −80 °C. DNA was extracted from biomass samples taken from Conch and Octopus Spring on October 11, 2011 and again on October 5, 2012. Subsequent samples in 2014 (July) and 2016 (November) were used to confirm community composition as well as to perform metatranscriptome analyses (described below). Metagenome sequence obtained from a prior sample (2008) of the filamentous community from Octopus Spring was described in a comprehensive analysis of geothermal systems in YNP24,40.

DNA was extracted using the MP Biomedicals FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil and/or the MoBio Power MaxTM Soil DNA Isolation Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA concentrations were measured with a Qubit fluorometer and sent to the DOE-Joint Genome Institute for shotgun metagenomic sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq machine in a 2 × 150 paired end run with dedicated read indexing and demultiplexed with bcl2fastq. Samples from 2011 and 2012 were sequenced at 10% and 100% of a single Illumina lane, respectively.

RNA was extracted from the Octopus and Conch streamer communities by modifying a FastRNA® Pro-Soil-Direct Kit (MP Biomedicals, LLC, Solon, OH, USA) extraction kit and method. RNA from the streamer communities (October 2011; July 2014; October 2016) was preserved in the field by placing streamer biomass directly into RNALater® (Life Technologies Co., Carlsbad, CA, USA) and shaking vigorously for ~15 s. Streamer biomass (~0.5 g, n = 3) was removed from the RNALater solution in a sterile, RNase-free hood, added to 0.5 mL of RNAproTM soil lysis solution in a lysing E matrix tube, and vortexed for 15 min. The sample lysate was then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred into a new 2 mL microcentrifuge tube (~500 – 800 μL), to which 1 mL of TriReagent was added and incubated for 5 min at room temperature (RT). Next, 200 μL of chloroform was added to the TriReagent/lysate mixture and incubated for 15 min at RT, followed by centrifugation at 16,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The triplicate supernatants containing RNA were pooled in a new tube to which 500 μL of ice-cold isopropanol (100 %) was added and incubated overnight at −20 °C to facilitate RNA precipitation. RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min and the pellet was washed once in ice-cold 70 % ethanol and centrifuged as before. The pellet was allowed to dry at RT for ~30 min, and immediately resuspended in 100 μL of TE buffer (pH = 7, Life Technologies Co. Carlsbad, CA, USA) and quantified with a Qubit® 2.0 fluoremeter and Qubit® RNA Broad Range Assay kit (Life Technologies Co. Carlsbad, CA, USA). Total RNA quality was checked with a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies Co., Santa Clara, CA, USA). DNA contamination was analyzed by PCR with universal archaeal and bacterial 16S rRNA genes primers and ethidium bromide agarose gel electrophoresis. When DNA was present it was removed by DNase I treatment (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by lithium chloride/ethanol precipitation overnight at −20 °C59.

Metagenome assembly and metagenome assembled genomes

Metagenome assemblies and quality-filtered FASTQ reads were obtained from DOE-JGI; IMG ‘Gold Analysis’ Project Numbers for all datasets used in the current study are provided in Supplementary Table 2. We used the most recent JGI assemblies as a baseline and performed our own assemblies using a custom procedure: Illumina sequencing errors were corrected using BFC and the remaining reads were split into paired and single60 before an assembly with MEGAHIT. We also compared different assembly methods to evaluate possible genome fragmentation, which can be caused by sequencing errors due to deep sequencing. Specifically, we compared down-sampling and digital normalization to sequencing depths of 60x, 80x and 100x60 to ensure no artifacts due to high coverage were reported. In most cases, metagenome assemblies were improved significantly using error correction alone. Generally, the MEGAHIT assemblies with custom error correction and read filtering were larger (greater number of bases assembled) and contained fewer contigs. High sequence coverage of numerous MAGs prompted an evaluation of down-sampling reads and/or digital coverage normalization. The random removal of 50% and 80% of reads as well as normalization to 60x and 100x coverage60 were used to evaluate impacts of high read coverage on MAG completeness and redundancy. In Octopus Spring, neither down-sampling nor digital normalization resulted in significant improvement of MAG completeness and redundancy metrics determined using single-copy marker genes (CheckM61) (Supplementary Table 3). In fact, redundancy estimates increased upon down-sampling for many MAGs, often with a concomitant loss in completeness. High coverage does not unilaterally result in high redundancy; in fact, several high-coverage MAGs such as Thermoproauctor were highly complete with redundancy estimates <10% (Supplementary Table 3). Assemblies for Conch 2011 were based on digital coverage normalization to 60x, which resulted in improved assembly parameters.

Tetranucleotide frequencies were calculated using CheckM61 and open TSNE was used to calculate the 2D embedding, from which the bins were generated by hierarchical density-based clustering. Only contigs > 2 Kb were used for binning. Completeness and redundancy of MAGs were determined using CheckM61. Coverage statistics were generated from Bowtie output after mapping Illumina reads to the assembled metagenome. G + C content and total contig length were calculated using BioPython scripts. tRNA sequences were predicted using tRNAscan-SE (https://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/). CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) arrays were identified with MinCED v0.4.2 (https://github.com/ctSkennerton/minced).

Initial taxonomic identification was determined with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool for nucleotide sequences (BLASTn) of every scaffold within every microbial population cluster to the nucleotide sequence database from NCBI. The majority consensus of scaffold hits was used to formulate taxonomic hypotheses for each population, which were tested with robust phylogenomic analyses (see below). Replicate populations were designated by > 95% ANI62.

Metatranscriptome sequence reads (Supplementary Table 2) were mapped to MAGs generated from 2011 and 2012. Data reported in the primary manuscript are based on transcripts mapped to MAGs generated from 2011 because the 2011 metatranscriptome from Octopus Spring was from a matching sample used for metagenome analysis. Metatranscriptomes from 2014 (Octopus) and 2017 (Octopus, Conch) were mapped to MAGs generated from 2011, primarily to provide consistency, however, similar results were obtained when these same transcripts were mapped to MAGs from 2012. Although transcripts were observed for most community members identified in metagenomes (e.g., Table 2), insufficient coverage precluded a thorough characterization of metabolic activity in the remaining phylotypes, which only comprised ~ 10–20% of the total transcripts sequenced (Fig. 6A). Replicate metatranscriptomes from Octopus Spring collected in 2011, 2014 and 2016 were highly correlated (p < 0.01) with one another (Supplementary Fig. 13), which is further evidence of the overall stability of these microbial communities; replicate transcriptomes from 2014 also confirmed reproducibility of RNA extraction and sequencing steps.

Metabolic potential

Each MAG from Conch and Octopus Spring (2011 and 2012) was uploaded for gene calling and annotation using ‘My Workspace’ on the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) portal. KEGG pathway analysis and confirmation of specific functional genes were accomplished on IMG. In addition, METABOLIC63 and DRAM64 were used to identify genes involved in metabolic pathways. METABOLIC output was used for all hierarchal heat maps except for the analysis of ‘carbohydrate active enzymes’, where DRAM output was used. Iron-related genes and their gene neighborhoods were identified with FeGenie (https://github.com/Arkadiy-Garber/FeGenie). The metabolic potential for sulfite and sulfate reduction via the Dsr pathway was evaluated using DiSCo33.

Phylogenomic analyses

Hidden Markov Models (HMM) were downloaded from PFAM database65 for the following 16 ribosomal proteins: L27a, S10, L2, L3, L4, L18p, L6, S8, L5, L24, L14, S17, S3c, L22, S19, L16. Custom HMMs were used for archaeal ribosomal proteins16. HMMer was used to scan microbial population clusters for HMM hits and ribosomal protein sequences were extracted from each population. Individual ribosomal proteins were aligned with MAFFT (--maxiterate 1000 --localpair --nomemsave)66 and positions with >50% gaps were trimmed with trimAl and BMGE67. Following the concatenation of 16 alignments, MrBayes (version 3.2.7a; MPI) was used for Bayesian inference analysis68 with the following parameters: 2 million generations, 0.25 burn-in fraction, 4 parallel chains, 4 rate categories, and invariable gamma models for rate variation, LG model with empirical amino acid frequencies and heating factors set to 0.1.

Select genomes for the 16S trees were retrieved from NCBI. For all genomes and MAGs, 16S sequences were identified and aligned using SSU-ALIGN. MrBayes68 was used for phylogenetic inference with similar parameters as above, except that inference typically took longer to converge (5 million generations for archaeal entries, and 10 million for bacterial entries).

AlphaFold2 modeling

Select HCO proteins from Conch and Octopus datasets were modeled with AlphaFold269 (AF2). All 3D models are in the very high confidence category by AF2 criteria, with average pLDDT values > 90. These models were structurally aligned to an HCO protein from Thermus thermophilus (PDB code 1EHK) (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw sequencing files for metagenomes and metatranscriptomes from Conch and Octopus Spring are available at NCBI (Metagenome Bioprojects PRJNA336661, PRJNA336655, PRJNA366311 and PRJNA366312; Metatranscriptome Bioprojects PRJNA443572, PRJNA443573 and PRJNA366530). Metagenome assembled genomes (MAGs) from this study are deposited at NCBI Bioproject PRJNA1186224. Related sequencing and/or analysis projects from the DOE-JGI Integrated Microbial Genomes database are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Additional data and movie files are available on Figshare as follows: Superposed 3D models of HCO proteins: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26339617.v1. Supplementary Excel Files: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26367556.v1. Supplementary Movies: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26367544.v1. The remainder of data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, the Source Data file and the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Catling, D. C. & Zahnle, K. J. The Archean atmosphere. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax1420 (2020).

Anantharaman, K. et al. Expanded diversity of microbial groups that shape the dissimilatory sulfur cycle. ISME J. 12, 1715 (2018).

McKay, L. J. et al. Co-occurring genomic capacity for anaerobic methane and dissimilatory sulfur metabolisms discovered in the Korarchaeota. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1 (2019).

Mulkidjanian, A. Y., Bychkov, A. Y., Dibrova, D. V., Galperin, M. Y. & Koonin, E. V. Origin of first cells at terrestrial, anoxic geothermal fields. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E821–E830 (2012).

Shen, Y., Buick, R. & Canfield, D. E. Isotopic evidence for microbial sulphate reduction in the early Archaean era. Nature 410, 77–81 (2001).

Canfield, D. E. The early history of atmospheric oxygen: Homage to Robert M. Garrels. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 33, 1–36 (2005).

Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T. & Planavsky, N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–315 (2014).

David, L. A. & Alm, E. J. Rapid evolutionary innovation during an Archaean genetic expansion. Nature 469, 93–96 (2010).

Reinhard, C. T., Planavsky, N. J., Olson, S. L., Lyons, T. W. & Erwin, D. H. Earth’s oxygen cycle and the evolution of animal life. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 8933–8938 (2016).

Jabłońska, J. & Tawfik, D. S. The evolution of oxygen-utilizing enzymes suggests early biosphere oxygenation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 442–448 (2021).

Waldbauer, J. R., Newman, D. K. & Summons, R. E. Microaerobic steroid biosynthesis and the molecular fossil record of Archean life. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13409–13414 (2011).

Anbar, A. D. et al. A whiff of oxygen before the great oxidation event? Science 317, 1903–1906 (2007).

Tomkins, A. G. et al. Ancient micrometeorites suggestive of an oxygen-rich Archaean upper atmosphere. Nature 533, 235–238 (2016).

Bueno, E., Mesa, S., Bedmar, E. J., Richardson, D. J. & Delgado, M. J. Bacterial adaptation of respiration from oxic to microoxic and anoxic conditions: Redox control. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 16, 819–852 (2012).

Han, H. et al. Adaptation of aerobic respiration to low O2 environments. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14109–14114 (2011).

Jay, Z. J. et al. Marsarchaeota are an aerobic archaeal lineage abundant in geothermal iron oxide microbial mats. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 732–740 (2018).

Jay, Z. J. et al. The distribution, diversity and function of predominant Thermoproteales in high-temperature environments of Yellow stone National Park. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 4755–4769 (2016).

Murali, R., Gennis, R. B. & Hemp, J. Evolution of the cytochrome bd oxygen reductase superfamily and the function of CydAA’ in Archaea. ISME J. 15, 3534–3548 (2021).

Theßeling, A. et al. Homologous bd oxidases share the same architecture but differ in mechanism. Nat. Commun. 10, 5138 (2019).

Stolper, D. A., Revsbech, N. P. & Canfield, D. E. Aerobic growth at nanomolar oxygen concentrations. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 18755–18760 (2010).

Dong, Y. et al. Physiology, metabolism, and fossilization of hot-spring filamentous microbial mats. Astrobiology 19, 1442–1458 (2019).

Forte, E. & Giuffrè, A. How bacteria breathe in hydrogen sulfide-rich environments. Biochemist 38, 8–11 (2016).

Reysenbach, A. L., Wickham, G. S. & Pace, N. R. Phylogenetic analysis of the hyperthermophilic pink filament community in Octopus Spring, Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 2113–2119 (1994).

Takacs-Vesbach, C. et al. Metagenome sequence analysis of filamentous microbial communities obtained from geochemically distinct geothermal channels reveals specialization of three Aquificales lineages. Front. Microbiol. 4, 84 (2013).

McKay, L. J. et al. Sulfur cycling and host-virus interactions in Aquificales-dominated biofilms from Yellowstone’s hottest ecosystems. ISME J. 16, 842–855 (2022).

Hug, L. A. et al. A new view of the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16048 (2016).

Parks, D. H. et al. GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D785–D794 (2022).

Colman, D. R. et al. Novel, deep-branching heterotrophic bacterial populations recovered from thermal spring metagenomes. Front. Microbiol. 7, 304 (2016).

Arndt, N. T. & Nisbet, E. G. Processes on the young earth and the habitats of early life. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 40, 521–549 (2012).

Marcia, M., Ermler, U., Peng, G. & Michel, H. The structure of Aquifex aeolicus sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase, a basis to understand sulfide detoxification and respiration. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 9625–9630 (2009).

Hamilton-Brehm, S. D. et al. Thermodesulfobacterium geofontis sp. nov., a hyperthermophilic, sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park. Extremophiles 17, 251–263 (2013).

Spring, S. et al. Complete genome sequence of Thermosphaera aggregans type strain (M11TL). Stand Genom. Sci. 2, 245–259 (2010).

Neukirchen, S. & Sousa, F. L. DiSCo: a sequence-based type-specific predictor of Dsr-dependent dissimilatory sulphur metabolism in microbial data. Micro. Genom. 7, 000603 (2021).

Drula, E. et al. The carbohydrate-active enzyme database: functions and literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D571–D577 (2022).

Jennings, Rd. M. et al. Integration of metagenomic and stable carbon isotope evidence reveals the extent and mechanisms of carbon dioxide fixation in high-temperature microbial communities. Front. Microbiol. 8, 88 (2017).

Hamamura, N. et al. Linking microbial oxidation of arsenic with detection and phylogenetic analysis of arsenite oxidase genes in diverse geothermal environments. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 421–431 (2009).

Huber, R. et al. Thermocrinis ruber gen. nov., sp. nov., a Pink-Filament-Forming Hyperthermophilic Bacterium Isolated from Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3576–3583 (1998).

Härtig, C. et al. Chemolithotrophic growth of the aerobic hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermocrinis ruber OC 14/7/2 on monothioarsenate and arsenite. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 90, 747–760 (2014).

Grabarczyk, D. B. & Berks, B. C. Intermediates in the Sox sulfur oxidation pathway are bound to a sulfane conjugate of the carrier protein SoxYZ. PLOS ONE 12, e0173395 (2017).

Inskeep, W. P., Jay, Z. J., Tringe, S. G., Herrgard, M. J. & Rusch, D. B. The YNP metagenome project: environmental parameters responsible for microbial distribution in the Yellowstone geothermal ecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 4, 67–82 (2013).

Giltner, C. L., Nguyen, Y. & Burrows, L. L. Type IV pilin proteins: Versatile molecular modules. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76, 740–772 (2012).

Berry, J.-L. & Pelicic, V. Exceptionally widespread nanomachines composed of type IV pilins: the prokaryotic Swiss Army knives. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 134–154 (2015).

Denise, R., Abby, S. S. & Rocha, E. P. C. Diversification of the type IV filament superfamily into machines for adhesion, protein secretion, DNA uptake, and motility. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000390 (2019).

Wallden, K., Rivera-Calzada, A. & Waksman, G. Microreview: Type IV secretion systems: versatility and diversity in function. Cell Microbiol. 12, 1203–1212 (2010).

Guglielmini, J. et al. Key components of the eight classes of type IV secretion systems involved in bacterial conjugation or protein secretion. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 5715–5727 (2014).

Angelini, S. et al. NfuA, a new factor required for maturing Fe/S proteins in escherichia coli under oxidative stress and iron starvation conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14084–14091 (2008).

Romsang, A., Duang-nkern, J., Saninjuk, K., Vattanaviboon, P. & Mongkolsuk, S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa nfuA: Gene regulation and its physiological roles in sustaining growth under stress and anaerobic conditions and maintaining bacterial virulence. PLOS ONE 13, e0202151 (2018).

Johnson, M. D. L. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PilY1 Binds Integrin in an RGD- and Calcium-Dependent Manner. PLOS ONE 6, e29629 (2011).

Burkhardt, J., Vonck, J. & Averhoff, B. Structure and function of PilQ, a Secretin of the DNA transporter from the thermophilic bacterium thermus thermophilus HB27. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 9977–9984 (2011).

Pereira, M. M. et al. Respiratory chains from aerobic thermophilic prokaryotes. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 36, 93–105 (2004).

Lebrun, E. et al. Arsenite oxidase, an ancient bioenergetic enzyme. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 686–693 (2003).

Inskeep, W. P. et al. Detection, diversity and expression of aerobic bacterial arsenite oxidase genes. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 934–943 (2007).

Visscher, P. T. et al. Modern arsenotrophic microbial mats provide an analogue for life in the anoxic Archean. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 1–10 (2020).

Inskeep, W. P. et al. On the energetics of chemolithotrophy in nonequilibrium systems: case studies of geothermal springs in Yellowstone National Park. Geobiology 3, 297–317 (2005).

To, T. B., Nordstrom, D. K., Cunningham, K. M., Ball, J. W. & McCleskey, R. B. New method for the direct determination of dissolved Fe(III) concentration in acid mine waters. Env. Sci. Tech. 33, 807–813 (1999).

American Public Health Association, American Waterworks Association, Water Environment Federation. In: Standard Methods For the Examination of Water and Wastewater (eds Clesceri, L. S., Greenberg, A. E. & Eaton, A. D.) APHA Press, Washington DC (1998).

Macur, R. E. et al. Microbial community structure and sulfur biogeochemistry in mildly-acidic sulfidic geothermal springs in Yellowstone National Park. Geobiology 11, 86–99 (2013).

Bernstein, H. C., Beam, J. P., Kozubal, M. A., Carlson, R. P. & Inskeep, W. P. In situ analysis of oxygen consumption and diffusive transport in high-temperature acidic iron-oxide microbial mats. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 2360–2370 (2013).

Beam, J. P. et al. Ecophysiology of an uncultivated lineage of Aigarchaeota from an oxic, hot spring filamentous ‘streamer’ community. ISME J. 10, 210–224 (2016).

Crusoe, M. R. et al. The Khmer software package: enabling efficient nucleotide sequence analysis. F1000Res 4, 900 (2015).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Thompson, C. C. et al. Microbial genomic taxonomy. BMC Genomics 14, 913 (2013).

Zhou, Z. et al. METABOLIC: high-throughput profiling of microbial genomes for functional traits, metabolism, biogeochemistry, and community-scale functional networks. Microbiome 10, 33 (2022).

Shaffer, M. et al. DRAM for distilling microbial metabolism to automate the curation of microbiome function. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 8883–8900 (2020).

El-Gebali, S. et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D427–D432 (2019).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Criscuolo, A. & Gribaldo, S. BMGE (Block Mapping and Gathering with Entropy): a new software for selection of phylogenetic informative regions from multiple sequence alignments. BMC Evol. Biol. 10, 210 (2010).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate support from NSF OPUS (1950770; W.P.I., M.D. and Z.J.) through the Systematics and Biodiversity Science Cluster and the Montana Agricultural Experiment Station (project 911300; W.P.I.). Metagenome sequencing was performed by the Joint Genome Institute under Community Sequencing Project Awards 787080, 701 and 1675. Electron microscopy and elemental analyses were performed at the Montana Nanotechnology Facility, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI), which is supported by NSF (ECCS-2025391). Assistance from M. Meslé on RNA extraction and T.B.K. Reddy on JGI-IMG Gold Project analyses is appreciated as well as collaboration with S. Blodgett and I. J. Russell on primary goals and findings of the study. Research in YNP was conducted under National Park Service Research Permits YELL-2011/2012/2014/2016-5068.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.P.I. obtained necessary permits, sequencing grants, and funding, designed and coordinated the study, collected the samples, jointly analyzed data, performed microscopy, and wrote the manuscript draft. Z.J.J. collected the samples and performed geochemical and bioinformatic analyses. L.J.M. collected samples and performed some bioinformatic analyses. M.D. obtained funding, processed the metagenomic and transcriptomic datasets, performed most of the bioinformatics analyses, jointly analyzed the data, and contributed to manuscript editing. All authors prepared the figures and tables, provided critical revisions, and approved the final manuscript. Z.J.J. and L.J.M. contributed equally and were ordered alphabetically by surname.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Karthik Anantharaman, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Inskeep, W.P., Jay, Z.J., McKay, L.J. et al. Respiratory processes of early-evolved hyperthermophiles in sulfidic and low-oxygen geothermal microbial communities. Nat Commun 16, 277 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55079-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55079-z