Abstract

The promise of integrating Electronic Medical Records (EMR) and genetic data for precision medicine has largely fallen short due to its omission of environmental context over time. Post-genomic data can bridge this gap by capturing the real-time dynamic relationship between underlying genetics and the environment. This perspective highlights the pivotal role of integrating EMR and post-genomics for personalized health, reflecting on lessons from past efforts, and outlining a roadmap of challenges and opportunities that must be addressed to realize the potential of precision medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The dawn of the 21st century heralded the promise of precision medicine equipped to radically transform patient healthcare through human genetics. Despite some notable successes1, this promise has largely fallen short. An overreliance on hereditary polygenic risk2, inadequate incorporation of environmental context3, and an oversimplification of human diversity4 have led to only cursory adoption by general clinical practice5, largely through direct-to-consumer products6.

As we navigate the 3rd decade of the 21st century, scientific perspectives are shifting. Technological advancements are enabling large-scale and frequent measurement of a diverse set of personalized molecular processes that may have their origin in DNA yet go far beyond this. From the transcriptome and the epigenome to the proteome, metabolome, and exposome, these -omic datatypes capture molecular perturbations due to both genetic and environmental factors and the interactions therein, broadening the scope of what may be possible with precision medicine7.

This paradigm shift in precision medicine is predicated on the acceptance that exposures over the course of the lifespan should be viewed as a key causal factor in molecular medicine and as pivotal to the success of personalized health. From this viewpoint, health is considered an episodic journey that is impacted by encounters along the lifecourse under the backdrop of genetic predisposition. Just as a smartphone camera allows a personal chronological record of events both life-changing and quotidian, post-genomic technology can be used to take periodic snapshots of molecular health, moving from a static genomic assessment of disease predisposition knowable at birth to a life-long molecular health trajectory. The ability to detect and avert disease in healthy individuals long before symptoms appear could empower an overburdened global healthcare system to move away from the current reactive models of disease management toward a more proactive model for preventing disease and maintaining health across an individual’s lifespan.

Early attempts to integrate genomic, post-genomic, and wearable technology measurements into a personalized health trajectory have shown promise. Of note is the P4 medicine model developed by Leroy Hood8. His Pioneer 100 Wellness Project (P100) provided a successful proof of concept9, and in 201310 he predicted that “in 10 years each patient will be surrounded by a virtual cloud of billions of data points, and we will have the tools to reduce this enormous data dimensionality into simple hypotheses about how to optimize wellness and avoid disease for each individual.” Although the timescale of this prophecy was ambitious, the goal remains a desirable one. He further identified “A key challenge is to fully integrate these diverse data types, correlate with distinct clinical phenotypes, extract meaningful biomarker panels for guiding clinical practice.”11 Acknowledging Hood’s actionable challenge for its insight, the more fundamental challenge for precision medicine is the practical integration of this vast individualized molecular ‘data cloud’ within existing electronic medical records (EMRs) and subsequent distillation into actionable advice for health practitioners that result in reduced healthcare costs. Real-time, patient-centered molecular records will empower health practitioners to provide precise, inclusive, bottom-up, evidence-based healthcare tailored to specific personal, and population needs.

This review outlines a roadmap toward precision medicine by examining the critical role of integrating EMRs and -omics data in shaping the path forward, drawing on past successes in genomic medicine and considering the needs of post-genomic medicine as we move from research to clinical practice. We discuss the specific challenges of integrating post-genomic data with EMRs, with particular focus on the critical need to map periodic -omic profiling with asynchronous EMRs12. Such integration will help to establish EMR-based precision medicine as an effective tool for health practitioners’ decision-making in everyday clinical practice. Beyond the practicalities of how we might implement this, there is a need to make this accessible and representative of all patient groups, particularly minority groups and underrepresented populations.

The emergence of electronic medical records for clinical research

Prior to EMRs, handwritten patient health records were stored locally at the point-of-care. Even within one clinical center, paperwork was often distributed across multiple offices, with separate clinical records, prescriptions, and billing details at each location. In 1972, the Regenstrief Institute, USA implemented the first EMR system13; however, it was not until the 1990s that sufficient computational and internet infrastructure enabled EMRs to gain traction, first in large academic institutions and now in virtually all clinical settings14. While practitioners voiced initial concerns that EMR systems would undermine the interpersonal aspects of patient care and impose a significant increase in cognitive load on an already overburdened profession15, the advantages they presented with regard to patient safety (via reduction of human errors), organizational consolidation, and simplification of billing processes for insurance providers ultimately led to their universal use16. The evolution of the EMR industry has predictably extended far beyond original intentions and now serves a variety of functions for a broad spectrum of interested parties as a singular, centralized data source. EMRs capture everything from health diagnoses to laboratory results, medication usage, family health history, prior immunizations, and billing details (Table 1). While they may have been designed to improve patient care, the efficient consolidation of data has additionally proven to be particularly valuable for clinical research17.

Highly structured EMR data enables straightforward computational use and interpretation in clinical studies. The adoption of structured systems, such as the International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes, provides comprehensive numerical coding of patient diagnoses and offers easy mechanisms for translation to clinical research. Combining ICD codes with other structured coding systems, such as SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms), HCPCS (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System), LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes), CVX codes (Vaccine Administered Code), or the DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine), details multiple aspects of clinical care that further enhances the spectrum of healthcare informatics. While inconsistencies will certainly exist across the selection and submission of codes, due to differences in disease classifications and granularity18, the widespread use of these standardized coding systems has provided a landscape for information standardization across platforms19.

Structured EMR data does not remove the need for unstructured data, and the ultimate need for more complex automated information extraction. The supplementation of coded fields with free text allows for flexibility, nuanced diagnoses, and facilitates the classification of emerging diseases (Table 1). Applications of Natural Language Processing (NLP) have already made significant strides in addressing the challenges of automated extraction of medical information from free-text20. Meanwhile, emerging technologies that leverage large language model (LLM) algorithms for medicine21,22 enable accurate interpretation of unstructured clinical texts. Understanding the progression of Alzheimer’s disease23,24 or tailoring diabetes therapy25,26 via information extracted from clinical notes offers just a few examples of the tremendous opportunity to improve individual health outcomes with these complex data structures. As our ability to rely on unstructured data increases, their combined use with structured coding systems will be pivotal in shaping the landscape of EMR-based research. As the digital age now allows for the continuous capture of health information through wearable devices, health-based apps, etc., there is no doubt that their integration into the EMR brings further research opportunities to advance biological understanding and improve patient care.

While there is no doubt that tremendous potential for translational research lies within the robust data available through EMR, it is imperative to recognize these data are not collected with the intent to do clinical research. They, therefore, have inherent biases, nuances, and complexities in what is and what is not recorded that make their use particularly challenging and vulnerable to misinterpretation, which we summarize in Table 2. Fortunately, approaches to overcome or limit these biases and shortcomings may often be incorporated into the study design. EMR data capture sporadic patient encounters over random intervals of time that are a combination of acute and scheduled health visits. Critically important is the consideration of the clinical context, which will help to maximize data richness and avoid potential bias, both in the existing data and the represented patient populations who may have more access to healthcare. For example, studying acute myocardial infarctions (MIs) in contrast to long-term health trajectories will require different data captures: the former may use indicators for patient encounters from the emergency room, concurrent acute MI diagnostic codes, while the latter may focus on patient encounters from regularly scheduled outpatient health visits (e.g. annual physicals) with their general practitioner. Using this approach in conjunction with other summary metrics created from the EMR, such as overall health status (e.g., the Charlson index27) or health care utilization28, can further facilitate the selection of appropriate patient samples for clinical research. Awareness of the systematic biases present in EMR patient populations also provides opportunities for clinical research to focus on minorities and other traditionally underrepresented groups.

Genetics, Biobanks, and EMR—the emergence of EMR-based precision medicine

As early as 196229, the study of therapeutic treatments for monogenetic diseases laid the groundwork for precision medicine, yet the full potential for large-scale application remained unrealized until technological advancements in DNA sequencing by Frederick Sanger in the late 1970s facilitated the identification of genes for major diseases including Huntington’s disease30, cystic fibrosis31, Alzheimer's disease32, and breast cancer33. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS)34 in the early 2000s marked a pivotal shift, enabling high-throughput DNA analysis at an unprecedented scale; broadening the scope of detectable genetic variations and allowing for the comprehensive analysis of the genetic makeup of individuals. The Human Genome Project was completed in 200335, however most of the studies that immediately followed had insufficient population sizes, particularly for sub-population analysis and assessment of rarer genetic variation. Consequently, genetic researchers strove to recruit larger and larger sample sizes. Central government funding agencies also shifted their focus toward developing very large, general-purpose (hypothesis-neutral) biobanks specifically designed for genomic research36. Unfortunately, these efforts were initially biased toward individuals of European ancestry, limiting genetic diversity4,37.

The linking of large-scale biobanks to EMR data rapidly gained global interest. The first government-supported EMR-linked biobank was established in 1996 by deCODE genetics38, a private company based in Reykjavík, with the aim of genotyping the complete population of Iceland. It is now an independent subsidiary of Amgen with a biobank cohort of over 350,000 samples. This initial success laid the foundations for several similar projects across the globe, including BioBank Japan39, the UK Biobank40, U.S. Million Veteran Program41, the China Kadoorie Biobank42, the Danish Biobank Register43, the Nord Trondelag Health Study (HUNT)44, the GenomeAsia 100K project45, the U.S. All of Us Research Program46, and the Finnish FinnGen47 project, one of the many projects under the Finnish Biobank Cooperative (FINBB), with many of these projects now providing external researchers with access to both their EMR and -omics data48,49,50,51,52,53,54 (Table 3). Of particular importance has been the establishment of the USA National Human Genome Research Institute-funded eMERGE (Electronic Medical Records and Genomics) Network to investigate methods and best practices for utilizing EMRs for large-scale, high-throughput genomic research55. To date, this network has published over 700 research articles and generated ‘participant-imputed’ GWAS data for over 100,000 individuals available for general use56. Key outcomes from the network include the development of algorithms to extract computable phenotypes, or ‘PheCodes’ from EMR data (based on ICD & CPT codes, billing codes, laboratory results, medication data) for genetic research57, with close to 70 phenotypes listed in the open-access PheKB.org catalog58; the development of best practice methods for incorporating and using patient genomic data with EMRs59; the establishment of ethical best practices60; shaping effective mechanisms for patient consent and data sharing61; and formalizing methodologies for large-scale phenome-wide association studies (PheWAS)62, which also allow for disease-associated variants to be systematically reviewed for their impact on other phenotypes within the EMR.

Despite the tremendous pace and indisputable contributions to understanding disease etiology, genomic precision medicine remains fundamentally limited, due primarily to a lack of accurate environmental context. Even the most reproducible common genetic variants found by GWAS display a very modest effect size63. By itself, the link between genetic-based risk prediction and appropriate clinical action is weak and imprecise64. Individual variants have been replaced by individual-level polygenic risk scores (a combination of the estimated effects of multiple genetic variants, each with a very small effect size on the risk of disease), but even a complex consolidation of genetic variants has still not accounted for the impact of environmental or lifestyle factors on complex trait risk65. Genomic studies in isolation can only ever provide a risk of genetic susceptibility—a measure of ‘what may happen’, but not ‘what is happening or will happen’. Genomics that is supplemented by this contextual information has far greater potential to achieve the semblance of precision medicine that has been long-envisioned.

While EMR presents a means to curate much contextual data, the current infrastructure largely focuses only on demographics, diagnoses, medications, and clinical interventions. Environmental and lifestyle EMR data are inconsistent, coarse-grained, and subjective, often depending on ad hoc self-reporting66. By providing more nuanced measurements of the individualized impact of environmental and lifestyle factors, post-genomic technologies offer an opportunity to complement current EMR and genomic data to fill this void. Therefore, it is the synthesis of EMR, genomics, and post-genomic data that will ultimately provide comprehensive patient profiles to enable precision medicine.

Rise of post-genomics: time is of the essence!

As next-generation sequencing led to a proliferation of genomic studies in the biomedical literature67; concurrent parallel technological advancements enabled the capture of molecular processes ‘downstream’ of genetics that manifest under different environmental conditions. The ‘-omic’ wide measurement of the epigenome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, microbiome, and exposome (Table 4) is rising to the ubiquity of genomics. Several pivotal projects have further enabled the use of these -omics in clinical research: the Human Epigenome Project68 initiated in tandem with the Human Genome Project completion35, followed by the Human Microbiome Project69, the Human Metabolome Database70 release in 2007, and the Human Proteome Project71 in 2010. The accumulation of these -omics sparked the conception of characterizing an individual’s health status by the aggregate state of a unique and complex interconnected biological system. This “systems biology” approach simultaneously considers multiple -omics technologies and characterizes how these complex molecular profiles interrelate to ultimately manifest in the clinical presentation of an individual. These multilevel post-genomic readouts of human wellbeing have the potential to infer how environmental exposures and lifestyle choices interact with genetic propensity for disease in unique and diverse ways, which may lead to new approaches to abate disease risk for individual circumstances.

The key concept here is plasticity. An individual’s health is not predetermined at birth but molded over time because of developmental programming and environmental context. There may be genetic risk factors for developing a given disease, but generally, these are more than matched by environmental risk factors, which are inherently malleable. This gives rise to the proposition that the state of each -omic profile over time can provide a unique modulating multifactorial descriptor of specific aspects of past and present health status—the rate of modulation being dependent on both the environmental exposure being considered and the -omic system being measured72. Epigenomic changes are relatively slow, taking weeks, months, or even years to accumulate73. In contrast, transcriptomics is more rapid, with gene expression modulated within minutes to hours in response to environmental cues or cellular processes74. Proteomic changes occur on a similar timescale, as protein levels and post-translational modifications adjust within minutes to hours or days, based on the specific protein and cellular context75. Lastly, metabolomics represents the most dynamic -omics system, with many metabolic changes happening within seconds to minutes or hours, contingent upon the specific metabolite and cellular context76. The synchronized interaction of these -omics layers collectively empowers an organism to adapt to environmental changes and maintain homeostasis. This understanding brings a fundamental paradigm shift to precision medicine: that changing environmental context over time (past, present, future) is a key factor in molecular medicine and critical to incorporate for the success of personalized health.

Post-Genomics and the EMR: learning from genomics in the research domain

Two decades of genomics research have built an effective framework linking EMRs to biobanks77 that provides a foundation for integrating post-genomics and EMR data. In some cases, this has already led to clinically translatable findings78. The potential of repurposing large cohort biobanks (Table 3) for post-genomic research is undeniably alluring, with a select few pioneering studies78,79,80; however, the extension of genomic-centric infrastructure and methodology into the post-genomic domain is not a simple process. Crucially, the collection and storage protocols required for post-genomic data reproducibility differ substantially from genomics81. Furthermore, the dynamic nature of post-genomic data, reflecting real-time physiological changes, necessitates periodic resampling that leads to more complex, context-specific collection strategies. For example, while observing maternal/fetal health during pregnancy, the maternal body undergoes dramatic metabolic, hormonal, and immunological shifts to accommodate the developing fetus and prepare for childbirth82. Capturing these dynamics requires an approach that moves beyond a singular snapshot to a series of carefully timed measurements, which together create a chronological narrative of maternal health. A noteworthy study by Long et al.83, provides an illustrative case in point. In this example, the periodicity and duration of sampling are specific to pregnancy, and unlikely to be appropriate for other health monitoring situations, such as chronic disease, where essential molecular dynamics may be slower, and monitoring requirements much longer. Recent work by Shen, et al.84 beautifully exemplifies the power of post-genomics to capture the nonlinear dynamics of disease and ageing processes through repeated multi-omic profiling over extended periods of time, and adeptly illustrates how harnessing these data bring new insights into an ever-changing health journey.

A roadmap to post-genomic clinical translation

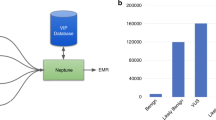

As post-genomic research evolves, a more nuanced understanding of the requirements for the biobank design is emerging, which effectively bridges the static nature of genetic data with the plasticity inherent in other -omic processes. It is also becoming clear that the non-targeted (-omic-wide) data acquired for the purposes of discovery research cannot reasonably be used in clinical practice. The more likely roadmap is one of global discovery, leading to the development of -omic biomarker panels tailored to specific contexts (Fig. 1), followed by the use of these panels together with medical records to guide clinical decision-making (Fig. 2). There are several promising frameworks for the clinical application of -omic biomarker panels that could significantly impact patient care. For instance, Fig. 2 highlights three examples: genetic risk screening, health management tools for tracking chronic disease progression and monitoring the risk of recurrent events, such as heart attacks. A key advantage of -omic biomarkers is the potential to provide critical insights earlier in the health journey, enabling prevention and the optimization of individual health, which can ultimately help reduce the broader healthcare burden. A significant challenge still lies in aligning data effectively across disparate time points. Determining the best approach—whether through nearest-time-point selection85, regression-based strategies86,87, or machine learning methodologies88—remains a critical focus for future integration efforts. As we continue to integrate these innovations, the road ahead offers numerous opportunities to refine our approach and develop effective frameworks, ensuring the highest standard of patient care.

This circular flow diagram represents the sequential stages of post-genomic research leading to clinical translation. Starting with patient enrollment, the cycle progresses through clinical visits, biosample collection, electronic medical record (EMR) integration, and -omics data generation. These steps culminate in biomarker discovery, ultimately enabling clinical translation. The circular structure highlights the iterative and interconnected nature of these processes. Created in BioRender. Su, J. (2024) https://BioRender.com/s06p486.

This illustrates how the integration of electronic medical records (EMR) and -omics data within healthcare systems can lead to improved health outcomes. Solid red lines represent health trajectories with -omics monitoring, showing improved outcomes due to timely interventions, while dashed red lines reflect trajectories without -omics monitoring, highlighting delayed interventions. EMR data is depicted as red squares (diagnoses) and red circles (medications), while -omics biomarker panels are represented as green circles (genetic risk screening), blue circles (health management), and purple circles (event risk monitoring). Created in BioRender. Su, J. (2024) https://BioRender.com/s06p486.

Challenges to EMR-omics integration

There are multiple formidable challenges that must be addressed for EMR-omics integration to have a truly transformative impact on precision medicine. While this will take considerable effort, there exist potential solutions to overcome each of these hurdles (Table 2). A preeminent challenge to securing the future of -omic-based healthcare lies in harmonizing and then standardizing these orthogonal -omic data sources, each with their own idiosyncrasies. With the current diversity in content and methodology, not just by -omic data sources but across different biofluids and tissues, this may seem like an impossible task, and initially, this integration will remain in the research (discovery) domain. However, as targeted disease-specific biomarker profiles are discovered and developed in clinical assays, this will be a more manageable prospect89. That said, such standardization is not merely a matter of data homogeneity; it also directly impacts the efficiency and accuracy of executing clinical algorithms, drawing insights, and facilitating real-time decision-making. Furthermore, it will also require the use of accredited laboratories with rigorous protocols for data acquisition.

Integrative longitudinal multi-omic analyses are also not without their complexities. The challenge shifts away from data acquisition and more toward data modeling enabling coherent and actionable insights that are both clinically meaningful and cost-saving. To truly harness the power of these longitudinal models, a significant shift in patient care strategy is required. Incorporating a systematic approach where patient biosamples and comprehensive clinical information are collected regularly on all patients will substantially contribute to a systematic clinical data capture that counteracts many of the current limitations of EMRs, including irregular timing of data collection, variability in accuracy and reliability, and structural inconsistencies that hinder seamless integration with dynamic -omics data (Table 2).

While the number of -omics tests can be reduced by focusing on disease-specific profiles, such as those identified through initial genetic profiling, or changes in BMI from previous clinical visits, this paradigm shift still demands significant resources and a reevaluation of current healthcare delivery models to accommodate the increased frequency and regularity of patient visits. This intensified approach to patient monitoring, while potentially offering unprecedented insights into health trajectories and early intervention opportunities, presents a logistical and financial challenge that must be addressed to fully realize the benefits of integrative multi-omic analyses. The collection of this density of data will likely require instituting novel approaches to both clinical data capture and biosample collection in order to not overextend current healthcare systems90. Other solutions that exist outside of the current clinical system may offer a more viable solution. Use of EMR-based wellness apps that automatically upload data from wearable monitoring devices and other regular patient inputs offers a simple solution to capturing massive amounts of additional data input that may be seamlessly integrated into the EMR. External clinical laboratories that collect and process biosamples offer another solution to bypass clinical visits yet still collect the necessary biosamples for clinical monitoring. While regular visits could be scheduled with patients, machine learning algorithms could also monitor biomarker panels and ‘trigger’ when in-person clinical visits are needed.

Ethical implications

As EMR and -omics data converge, a complex ethical landscape emerges. Central to these concerns is the principle of informed consent. Genetic testing not only informs the current risk of a specific disease, but also reveals health predispositions, ancestral histories, and intricate biological information that could resonate across a lifetime and even influence future generations91,92,93. The ethical complexities extend to issues of confidentiality and privacy, as genetic insights into one patient can inadvertently reveal information about their relatives94,95,96. While similar concerns apply to post-genomic data, their implications are less immutable due to the plasticity of the underlying processes. For instance, snapshots of the metabolome or proteome, while initially predictive of future disease, can change significantly with age, lifestyle shifts, or environmental exposures, altering associated risks over time.

Navigating the ethical complexities of resource allocation becomes more pronounced given the high costs associated with -omics testing97,98,99. As we expand further into the realms of multi-omics, inevitably, the cost of health monitoring escalates, particularly with the prospect of longitudinal repeated testing over time. Determining who gets access to such sophisticated testing is of prescient concern. Balancing economic constraints, medical needs, and ethical obligations pushes us towards a rigorous discourse on how best to allocate medical resources, aiming for judicious and fair utilization while also embracing the revolutionary potential of -omics insights.

Equitable access to precision medicine

Looking toward post-genomic clinical translation in modern healthcare, a parallel commitment to reducing disparities that hinder equal access is essential. Socioeconomic inequalities, geographic barriers, and entrenched systemic biases in the United States continue to prevent marginalized populations from fully realizing the benefits of advanced health technologies100. Without focused intervention, EMR-omics integration risks further deepening the healthcare inequities that already exist.

Addressing cost barriers, equitable infrastructure investments, and inclusive research efforts are essential to ensure that advancements in precision medicine benefit all populations (Table 2). As we transition to a more intensive model of patient monitoring through longitudinal -omics profiling, the associated costs will disproportionately limit access for lower-income populations. Financial mechanisms at the individual level, including subsidies, sliding-scale payment models, and public insurance coverage, and at the institutional level, such as reimbursement programs, grants, and tax incentives, are critical. Geographic disparities, particularly in rural areas where underfunded health centers cannot sustain this level of patient monitoring, introduce additional obstacles101. Strategic investments in rural health systems, including infrastructure improvements, the establishment of external clinical laboratories, and the expansion of telehealth services to alleviate pressure on existing facilities, are crucial. Lastly, for successful post-genomic clinical translation, -omics biomarker panels must be effective across diverse populations; yet, systemic biases in -omics research persist, with a disproportionate focus on European ancestry102. This has led to well-documented issues in genetics, particularly concerning the diagnostic efficacy of certain genetic tests for underrepresented groups4,37. Increasing diversity in research populations is essential to developing inclusive -omics biomarker panels and ensuring that precision medicine benefits all.

The future of precision healthcare and a move toward prevention

The U.S. healthcare system, in particular, has historically leaned heavily towards reactive treatments rather than preemptive measures103. In the United States, this narrative began to change with the proclamation of the “Precision Medicine Initiative” by former president Barack Obama in his January 2015 State of the Union Address104; since then, the emphasis on personalized medicine has not only deepened but has also steered the discourse towards a more holistic and preventive approach105. Alongside such initiatives, regulatory measures like the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA)106 were introduced to ensure that, as the healthcare system moved towards more personalized approaches, individuals were protected from potential discrimination based on their genetic data. Amongst the $215 million aimed in funding, this initiative crucially allocated significant resources towards data and informatics, laying the essential groundwork to manage the integration of -omics data with the EMR107. This shift towards EMR-omics integration around 2013 is highlighted in Fig. 3, with the start of leveraging both EMR and post-genomic technologies in research contexts.

This timeline maps key developments in EMR, indicated in red, alongside seminal advances in genomics, marked in blue, and post-genomic fields, highlighted in yellow. Underscoring the integration of EMR with genomics, represented in purple, by 2006, and the subsequent integration with post-genomic data, in brown, by 2013. Created in BioRender. Su, J. (2024) https://BioRender.com/s06p486.

Precision medicine champions proactive healthcare informed by personalized -omics data, shifting ideology away from treatment to prevention. Yet the deep-rooted inclination towards treatment over prevention in global healthcare systems has myriad causes, influenced by clinical practices, medical traditions, and economic motivations108. In the United States, this bias intensifies, significantly influenced by the profit-driven structures of the healthcare economy. Insurance companies, pivotal players in the American health landscape, have long aligned their economic interests with treatments, seeing them as more immediate reasons for payment109. This alignment is not without its contradictions. While treatments bring in direct revenue to healthcare systems, preventive measures, though often overlooked in terms of immediate profitability, promise significant long-term financial savings110. By minimizing high-cost interventions and reducing the length and frequency of hospital admissions, preventive strategies can drastically cut healthcare expenditures in the long run111. Yet, the allure of the immediate returns from treatments often overshadows these long-term savings, leading to a paradox where the apparent financial benefits of reactive care deter investments in more sustainable, preventive approaches. To truly transition towards a preventive model underpinned by precision medicine, the healthcare industry must innovate and devise new economic structures and revenue streams that prioritize and reward long-term patient well-being over short-term treatment results. Only by aligning financial incentives with proactive care can we ensure the widespread adoption and sustainability of this transformative approach. Implementing reimbursements for screening could allow healthcare systems to transition toward a more preventive, all-inclusive patient-focused model, fully realizing the benefits of precision medicine.

Reflections and future potential

Thirty years after the start of the Human Genome Project, a new frontier has emerged within precision medicine that involves assimilating post-genomic data into a framework that began with genetics alone. While this may seem to point to a promise that has fallen short regarding the transformation of healthcare and disease treatment, it is really the unimagined consequences of these efforts that brought forth a crucial, yet often unrecognized scientific advance to the impending omics revolution. “Its success should be measured by how this project transformed the rules of research, the way of practicing biological discovery and the ubiquitous digitization of biological science,” as Richard Gibbs sagely advised112. The ubiquitous digitization of medical records via EMRs merging with genetic predisposition and real-time post-genomic data has the potential to revolutionize diagnostic and treatment paradigms. Despite the challenges, the trajectory towards seamless EMR-‘omics’ integration is promising, signaling a bright future for precision medicine.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

References

Ashley, E. A. Towards precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 507–522 (2016).

Lewis, C. M. & Vassos, E. Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Med. 12, 44 (2020).

Li, J., Li, X., Zhang, S. & Snyder, M. Gene–environment interaction in the era of precision medicine. Cell 177, 38–44 (2019).

Popejoy, A. B. & Fullerton, S. M. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature 538, 161–164 (2016).

Bonham, V. L., Callier, S. L. & Royal, C. D. Will precision medicine move us beyond race? N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 2003 (2016).

Majumder, M. A., Guerrini, C. J. & McGuire, A. L. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: value and risk. Annu. Rev. Med. 72, 151–166 (2021).

Dai, X. & Shen, L. Advances and trends in omics technology development. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9, 911861 (2022).

Flores, M., Glusman, G., Brogaard, K., Price, N. D. & Hood, L. P4 medicine: how systems medicine will transform the healthcare sector and society. Personalized Med. 10, 565–576 (2013).

Price, N. D. et al. A wellness study of 108 individuals using personal, dense, dynamic data clouds. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 747–756 (2017).

Hood, L. Systems biology and p4 medicine: past, present, and future. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 4, e0012 (2013).

Hood, L. & Tian, Q. Systems approaches to biology and disease enable translational systems medicine. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 10, 181–185 (2012).

Misra, B. B., Langefeld, C. D., Olivier, M. & Cox, L. A. Integrated omics: tools, advances, and future approaches. J. Mol. Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1530/jme-18-0055 (2018).

McDonald, C. J. et al. The Regenstrief Medical Record System: a quarter century experience. Int. J. Med. Inf. 54, 225–253 (1999).

Haughom, J., Kriz, S. & McMillan, D. R. Overcoming barriers to EHR adoption: one health system managed its organizationwide patient health data exchange by first gaining input from clinicians and working cooperatively with competitors. Healthc. Financ. Manag. 65, 96–101 (2011).

Honavar, S. G. Electronic medical records—the good, the bad and the ugly. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 68, 417–418 (2020).

Miller, R. H. & Sim, I. Physicians’ use of electronic medical records: barriers and solutions. Health Aff. 23, 116–126 (2004).

Wells, Q. S. et al. Accelerating biomarker discovery through electronic health records, automated biobanking, and proteomics. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 2195–2205 (2019).

Cartwright, D. J. ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM codes: what? Why? How? Adv. Wound Care (N. Rochelle) 2, 588–592 (2013).

Kurbasic, I. et al. The advantages and limitations of International Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death from Aspect of Existing Health Care System of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Acta Inf. Med. 16, 159–161 (2008).

Hossain, E. et al. Natural Language Processing in Electronic Health Records in relation to healthcare decision-making: A systematic review. Comput. Biol. Med. 155, 106649 (2023).

Lee, J. et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 36, 1234–1240 (2020).

Huang, K., Altosaar, J. & Ranganath, R. Clinicalbert: modeling clinical notes and predicting hospital readmission. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.05342 (2019).

Kumar, S. et al. Machine learning for modeling the progression of Alzheimer disease dementia using clinical data: a systematic literature review. JAMIA Open 4, ooab052 (2021).

Jaakkimainen, R. L. et al. Identification of physician-diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in population-based administrative data: a validation study using family physicians’ electronic medical records. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 54, 337–349 (2016).

Bertsimas, D., Kallus, N., Weinstein, A. M. & Zhuo, Y. D. Personalized diabetes management using electronic medical records. Diab. care 40, 210–217 (2017).

Benhamou, P.-Y. Improving diabetes management with electronic health records and patients’ health records. Diab. Metab. 37, S53–S56 (2011).

Charlson, M. E., Carrozzino, D., Guidi, J. & Patierno, C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: a critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 91, 8–35 (2022).

Hussey, P. S. et al. A systematic review of health care efficiency measures. Health Serv. Res. 44, 784–805 (2009).

Kalow, W. Pharmacogenetics, heredity and the response to drugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 52, 208–208 (1962).

Bates, G. P. The molecular genetics of Huntington disease—a history. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 766–773 (2005).

Tsui, L.-C. & Dorfman, R. The cystic fibrosis gene: a molecular genetic perspective. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 3, a009472 (2013).

Laws, S. M., Hone, E., Gandy, S. & Martins, R. N. Expanding the association between the APOE gene and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: possible roles for APOE promoter polymorphisms and alterations in APOE transcription. J. Neurochem. 84, 1215–1236 (2003).

Francken, A. B., Schouten, P. C., Bleiker, E. M., Linn, S. C. & Emiel, J. T. Breast cancer in women at high risk: the role of rapid genetic testing for BRCA1 and-2 mutations and the consequences for treatment strategies. Breast 22, 561–568 (2013).

Goodwin, S., McPherson, J. D. & McCombie, W. R. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 333–351 (2016).

Collins, F. S. et al. New goals for the US human genome project: 1998–2003. Science 282, 682–689 (1998).

Kinkorová, J. Biobanks in the era of personalized medicine: objectives, challenges, and innovation. EPMA J. 7, 4 (2016).

Sirugo, G., Williams, S. M. & Tishkoff, S. A. The missing diversity in human genetic studies. Cell 177, 26–31 (2019).

Gulcher, J. & Stefansson, K. An Icelandic saga on a centralized healthcare database and democratic decision making. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 620–620 (1999).

Nagai, A. et al. Overview of the BioBank Japan Project: study design and profile. J. Epidemiol. 27, S2–s8 (2017).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Gaziano, J. M. et al. Million Veteran Program: a mega-biobank to study genetic influences on health and disease. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 70, 214–223 (2016).

Chen, Z. et al. China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 1652–1666 (2011).

Laugesen, K. et al. A review of major Danish Biobanks: advantages and possibilities of health research in Denmark. Clin. Epidemiol. 15, 213–239 (2023).

Krokstad, S. et al. Cohort Profile: the HUNT study, Norway. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 968–977 (2013).

Wall, J. D. et al. The GenomeAsia 100K Project enables genetic discoveries across Asia. Nature 576, 106–111 (2019).

Denny, J. C. et al. The “All of Us” research program. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 668–676 (2019).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen: unique genetic insights from combining isolated population and national health register data. Preprint at medRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.03.22271360 (2022).

University of Tartu. Estonian Biobank https://genomics.ut.ee/en/content/estonian-biobank (2024).

BioBank Japan. Overview of BBJ’s Samples and Data https://biobankjp.org/en/researchers/1971 (2024).

UK Biobank. About Our Data https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research/about-our-data (2024).

lifelines. Data Catalogue https://data-catalogue.lifelines.nl (2024).

Genomics England. 100,000 Genomes Project https://www.genomicsengland.co.uk/initiatives/100000-genomes-project (2024).

FinnGen. Data Available In FinnGen https://www.finngen.fi/en/researchers/data_available (2024).

All of Us Research Hub. Data Browser https://databrowser.researchallofus.org (2024).

Gottesman, O. et al. The Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) network: past, present, and future. Genet. Med. 15, 761–771 (2013).

eMERGE Consortium. Lessons learned from the eMERGE Network: balancing genomics in discovery and practice. HGG Adv 2, 100018 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xhgg.2020.100018 (2021).

Wei, W. Q. & Denny, J. C. Extracting research-quality phenotypes from electronic health records to support precision medicine. Genome Med. 7, 41 (2015).

Kirby, J. C. et al. PheKB: a catalog and workflow for creating electronic phenotype algorithms for transportability. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 23, 1046–1052 (2016).

Bowdin, S. et al. Recommendations for the integration of genomics into clinical practice. Genet. Med. 18, 1075–1084 (2016).

Wan, Z. et al. Expanding access to large-scale genomic data while promoting privacy: a game theoretic approach. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 316–322 (2017).

Sanderson, S. C. et al. Public attitudes toward consent and data sharing in Biobank research: a large multi-site experimental survey in the US. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 414–427 (2017).

Denny, J. C. et al. Systematic comparison of phenome-wide association study of electronic medical record data and genome-wide association study data. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 1102–1111 (2013).

Young, A. I., Benonisdottir, S., Przeworski, M. & Kong, A. Deconstructing the sources of genotype-phenotype associations in humans. Science 365, 1396–1400 (2019).

Lewis, A. C. F., Green, R. C. & Vassy, J. L. Polygenic risk scores in the clinic: Translating risk into action. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2, 100047 (2021).

Hunter, D. J. Gene–environment interactions in human diseases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 287–298 (2005).

Bush, W. S., Oetjens, M. T. & Crawford, D. C. Unravelling the human genome–phenome relationship using phenome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 129–145 (2016).

Lander, E. S. et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409, 860–921 (2001).

Esteller, M. The necessity of a human epigenome project. Carcinogenesis 27, 1121–1125 (2006).

Turnbaugh, P. J. et al. The human microbiome project. Nature 449, 804–810 (2007).

Wishart, D. S. et al. HMDB: the human metabolome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D521–D526 (2007).

Legrain, P. et al. The human proteome project: current state and future direction. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 10, M111.009993 (2011).

Buescher, J. M. & Driggers, E. M. Integration of omics: more than the sum of its parts. Cancer Metab. 4, 1–8 (2016).

Feinberg, A. P. & Fallin, M. D. Epigenetics at the crossroads of genes and the environment. JAMA 314, 1129–1130 (2015).

Palazzo, A. F. & Lee, E. S. Non-coding RNA: what is functional and what is junk? Front. Genet. 6, 2 (2015).

Schubert, O. T., Röst, H. L., Collins, B. C., Rosenberger, G. & Aebersold, R. Quantitative proteomics: challenges and opportunities in basic and applied research. Nat. Protoc. 12, 1289–1294 (2017).

Nicholson, J. K. & Lindon, J. C. Systems biology: metabonomics. Nature 455, 1054–1056 (2008).

Crawford, D. C. & Sedor, J. R. Biobanks linked to electronic health records accelerate genomic discovery. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 1828–1829 (2021).

Kachroo, P. et al. The systematic use of metabolomic epidemiology, biobanks, and electronic medical records for precision medicine initiatives in asthma: findings suggest new guidelines to optimize treatment. Nat. Portf. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-268507/v1(2022).

Pietzner, M. et al. Plasma metabolites to profile pathways in noncommunicable disease multimorbidity. Nat. Med. 27, 471–479 (2021).

Luo, S. et al. NAT8 variants, N-acetylated amino acids, and progression of CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 37–47 (2020).

Yin, P., Lehmann, R. & Xu, G. Effects of pre-analytical processes on blood samples used in metabolomics studies. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 407, 4879–4892 (2015).

Murray, I. & Hendley, J. Change and adaptation in pregnancy. Myles’ Textbook for Midwives E-Book, 197 (2020).

Long, S. E. et al. Longitudinal associations of pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain with maternal urinary metabolites: an NYU CHES study. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 46, 1332–1340 (2022).

Shen, X. et al. Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging. Nat. Aging https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-024-00692-2 (2024).

Engels, J. M. & Diehr, P. Imputation of missing longitudinal data: a comparison of methods. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 56, 968–976 (2003).

McQuarrie, A. D. & Tsai, C.-L. Regression and Time Series Model Selection (World Scientific, 1998).

Chatfield, C. The Analysis of Time Series: Theory and Practice (Springer, 2013).

Specht, D. F. A general regression neural network. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2, 568–576 (1991).

Wu, P. Y. et al. Omic and electronic health record big data analytics for precision medicine. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 64, 263–273 (2017).

Yarnall, K. S., Pollak, K. I., Østbye, T., Krause, K. M. & Michener, J. L. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am. J. Public Health 93, 635–641 (2003).

Fisher, C. B. & Harrington McCarthy, E. L. Ethics in prevention science involving genetic testing. Prev. Sci. 14, 310–318 (2013).

Botkin, J. R. et al. Points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97, 6–21 (2015).

Hogarth, S., Javitt, G. & Melzer, D. The current landscape for direct-to-consumer genetic testing: legal, ethical, and policy issues. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 9, 161–182 (2008).

Hallowell, N. et al. Balancing autonomy and responsibility: the ethics of generating and disclosing genetic information. J. Med. Ethics 29, 74 (2003).

Young, M.-A. The responses of research participants and their next of kin to receiving feedback of genetic test results following participation in the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study. Genet. Med. 15, 458–465 (2013).

Finkler, K., Skrzynia, C. & Evans, J. P. The new genetics and its consequences for family, kinship, medicine and medical genetics. Soc. Sci. Med. 57, 403–412 (2003).

Lemieux-Charles, L., Meslin, E. M., Baker, R. & Leatt, P. Ethical issues faced by clinician/managers in resource-allocation decisions. J. Healthc. Manag. 38, 267–285 (1993).

Calman, K. The ethics of allocation of scarce health care resources: a view from the centre. J. Med. Ethics 20, 71–74 (1994).

Wafi, A. & Mirnezami, R. Translational-omics: future potential and current challenges in precision medicine. Methods 151, 3–11 (2018).

Dickman, S. L., Himmelstein, D. U. & Woolhandler, S. Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. Lancet 389, 1431–1441 (2017).

Cacari Stone, L., Roary, M. C., Diana, A. & Grady, P. A. State health disparities research in rural America: gaps and future directions in an era of COVID-19. J. Rural Health 37, 460–466 (2021).

Yang, G., Mishra, M. & Perera, M. A. Multi-omics studies in historically excluded populations: the road to equity. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 113, 541–556 (2023).

Waldman, S. A. & Terzic, A. Health care evolves from reactive to proactive. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 105, 10–13 (2019).

Terry, S. F. Obama’s precision medicine initiative. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 19, 113–114 (2015).

Jørgensen, J. T. Twenty years with personalized medicine: past, present, and future of individualized pharmacotherapy. Oncologist 24, e432–e440 (2019).

Health law - genetics - Congress restricts use of genetic information by insurers and employers. - Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, Pub. L. No. 110-233, 122 Stat. 881 (to be codified in scattered sections of 26, 29, and 42 U.S.C.). Harv Law Rev 122, 1038-1045 (2009).

McGrath, S. & Ghersi, D. Building towards precision medicine: empowering medical professionals for the next revolution. BMC Med. Genom. 9, 23 (2016).

Squassina, A. et al. Realities and expectations of pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine: impact of translating genetic knowledge into clinical practice. Pharmacogenomics 11, 1149–1167 (2010).

Underhill, K. Paying for prevention: challenges to health insurance coverage for biomedical HIV prevention in the United States. Am. J. Law Med. 38, 607–666 (2012).

Waters, H. & Graf, M. The Costs of Chronic Disease in the US (The Milken Institute, Santa Monica, CA, 2018).

Porter, M. E. & Teisberg, E. O. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-based Competition on Results (Harvard Business Press, 2006).

Gibbs, R. A. The Human Genome Project changed everything. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 575–576 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grant funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) under award number R01HL155742 (K.M. Mendez, R.S. Kelly, J.A. Lasky-Su, Q. Chen, and M. McGeachie).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M. Mendez, S.N. Reinke, R.S. Kelly, D.I. Broadhurst, and J.A. Lasky-Su contributed to the original draft preparation, and Q. Chen, M. Su, M. McGeachie, and S. Weiss reviewed edited, and gave feedback on the original draft as additional subject experts. All authors then reviewed, provided feedback on, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pankaj Agrawal and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mendez, K.M., Reinke, S.N., Kelly, R.S. et al. A roadmap to precision medicine through post-genomic electronic medical records. Nat Commun 16, 1700 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56442-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56442-4

This article is cited by

-

Deep learning for sustainable development across climate, energy, agriculture and urban systems

Discover Sustainability (2025)