Abstract

We developed a two-stage manufacturing process utilizing cultivated autologous limbal epithelial cells (CALEC), the first xenobiotic-free, serum-free, antibiotic-free protocol developed in the United States, to treat blindness caused by unilateral limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) and conducted a single-center, single-arm, phase I/II clinical trial. Primary outcomes were feasibility (meeting release criteria) and safety (ocular infection, corneal perforation, or graft detachment). Participant eligibility included male or female participants age 18 to <90 years old and ability to provide written informed consent with LSCD. Funding was provided by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health. CALEC grafts met release criteria in 14 (93%) of 15 participants at conclusion of trial. After first stage manufacturing, intracellular adenosine triphosphate levels correlated with colony forming efficiency (r = 0.65, 95% CI [0.04, 0.89]). One bacterial infection occurred unrelated to treatment, with no other primary safety events. The secondary outcome was to investigate efficacy based on improvement in corneal epithelial surface integrity (complete success) or improvement in corneal vascularization and/or participant symptomatology as measured by OSDI and SANDI (partial success). 86%, 93%, and 92% of grafts resulted in complete or partial success at 3, 12, and 18 months, respectively. Our results provide strong support that CALEC transplantation is safe and feasible and further studies are needed to evaluate therapeutic efficacy. Clinicaltrials.gov registration: NCT02592330.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corneal clarity depends on the regenerative capacity of limbal epithelial stem cells (LESCs)1, which reside in the corneal limbus and continually provide specialized corneal epithelium while serving as a barrier between conjunctiva and cornea2. Limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) is characterized by conjunctivalization of the corneal surface and other signs of diminished integrity of the corneal epithelium, such as neovascularization, inflammation, scarring and opacity, which lead to decreased vision and debilitating symptoms (pain, photophobia, and tearing)3. LSCD management aims to re-establish a healthy ocular surface and adjacent limbal niche to support limbal epithelial stem cells4,5. In unilateral LSCD, autologous donor tissue can be harvested from the patient’s unaffected eye6,7. Autologous is preferred to allogeneic grafting, since it has higher success rates with fewer complications and does not require lifelong systemic immunosuppression8,9. Surgical strategies include direct grafting of autologous tissue (conjunctival limbal autograft6 [CLAU] and simple limbal epithelial transplantation10 [SLET]) and cultivated limbal epithelial transplantation11 (CLET). In CLET, epithelial cells from a limbal biopsy of the donor eye are expanded ex vivo and grafted to the recipient ocular surface11. CLET harvests less donor limbal tissue than CLAU, reducing the risk for inducing LSCD in the donor eye12. Although SLET also utilizes less donor tissue, limbal epithelial stem cells are not expanded before grafting, and limited long-term follow-up is available10,13.

Since the first publication of CLET11, multiple trials have supported its utility and feasibility; however, it is not available in the United States14. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not yet approved a CLET procedure because Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP)-compliant processes for manufacturing this type of product and clinical trials to evaluate this approach have not been developed.

To address this barrier, we developed a standardized two-stage manufacturing technique termed cultivated autologous limbal epithelial cell (CALEC) transplantation14,15. Our manufacturing procedure used only FDA-compliant materials without allogeneic or xenogeneic feeder cells. Standardized assays were developed to monitor the manufacturing process and establish rigorous product release criteria. Development of the CALEC manufacturing process and short-term (12 months) outcomes of the initial four transplant recipients were previously reported15. We now report outcomes of the completed phase I/II trial designed to evaluate feasibility, safety, and to investigate the efficacy of this novel technique14.

Results

Enrollment, Follow-up, Participant Characteristics

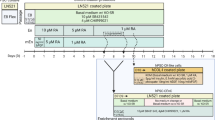

Five participants enrolled during the initial recruitment phase, August 22, 2016, to January 2, 2019, and 10 additional participants enrolled during open recruitment, August 19, 2019, to September 29, 2021 (Fig. 1). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the 14 participants who received a CALEC transplant are summarized in Table 1. Age at enrollment ranged from 24 to 78 years, and 10 (71%) had no epithelial defects at baseline. Clinical photos for all study participants are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1A. Follow-up through the 18-month visit was completed by all but one participant who received a second transplant after the 12-month visit (Fig. 1).

Flowchart of N = 15 participants who enrolled in the trial and completed a biopsy for CALEC. For simplicity of presentation of results, two additional participants who enrolled in the study are not counted in these 15: One participant in the open enrollment phase discontinued the study before proceeding to biopsy. One participant enrolled in the randomized CLAU group and completed the study through 18 months; this was the only CLAU participant prior to discontinuation of the randomized CLAU arm of the study.

Manufacturing Outcomes and Construct Biomarker Data

Fourteen (88%) of 16 biopsies (in 15 participants) resulted in a manufacturing success (Supplementary Tables 3, 4). Two failures occurred in the initial recruitment phase and were previously reported15. CALEC grafts were successfully manufactured for subsequent patients. Two constructs were manufactured from 1 limbal biopsy for each patient. Only one construct did not meet release criteria due to high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), indicating low viability and the backup construct that met release criteria was used for transplant.

The number of days from biopsy to final harvest ranged from 13 to 27 with final cell counts ranging from 0.4 x 106 to 1.5 x 106 (Table 2). Cells obtained at P0 consistently expressed high levels (~98%) of epithelial markers (CD49F and CD340), low levels (~2%) of hematopoietic/endothelial markers (CD45/CD31), and low levels (~3%) of a myeloid/mesenchymal cell marker (CD13), confirming the predominantly epithelial phenotype of cultivated LEC (Table 2). Exploratory analyses of in-process manufacturing assays revealed that colony forming efficiency (CFE) percent at P0 correlated with days from biopsy to P0 harvest (r = -0.64, 95% CI [-0.87, -0.11]), and intracellular adenosine triphosphate (iATP) ratio (r = 0.65, 95% CI [0.04, 0.89]) (Fig. 2B–C; Supplementary Table 5).

A Schematic representation of CALEC preparation from the limbal biopsy of the donor eye, harvesting, and isolation of limbal epithelial cells into single cell suspension at P0; followed by cell seeding onto the denuded human amniotic membrane, AmnioGraft, draped over a transwell into the secondary (P1) culture. The resulting CALEC construct is then transplanted on the diseased eye (1). Phase contrast images cultivated autologous epithelial cells at P0 (2) and P1(3), Scale – 100 µm. B Spearman Correlation of Colony Forming Efficiency (CFE)% at P0 with Intracellular Adenosine Triphosphate (iATP) ratio (N = 11). C Spearman Correlation of Colony Forming Efficiency (CFE) % with Days from Biopsy to P0 Harvest (N = 13).Includes data for all conforming constructs (N = 14 biopsies). Missing values are detailed in Supplementary Table 3.

Immunohistology of backup CALEC constructs revealed a narrow range of biomarker expression, with median positive rates of 4.0%, 4.4%, 2.8%, and 3.0% for p63, p63α, C/EBPδ, and Krt12, respectively (Supplementary Table 6). These rates indicate that a small but consistent portion of the cultured epithelial cells express ‘stemness’ markers or are mitotically quiescent. The relatively low positive rate of Krt12 suggests that few cultured epithelial cells are fully differentiated. The median RT-PCR copy numbers of p63, p63α, C/EBPδ, Krt12, Krt14, Notch1 and ABCG2 (relative to 100 copies of internal control beta-actin) are 3.0, 4.0, 0.1, 5.5, 16.2, 0.1, 0.9, respectively (Supplementary Table 6). Correlations among RT-PCR markers ranged from 0.10 to 0.81 indicating varying degrees of consistency among these putative stem cell markers. The largest negative correlations were between Krt14 and Krt12 (r = -0.64) and Krt12 and Notch 1 (-0.48). The largest positive correlations were between C/EBPδ and p63 (r = 0.77), C/EBPδ and p63α (r = 0.63), C/EBPδ and Krt12 (r = 0.65), C/EBPδ and Notch1 (r = 0.69), p63 and p63α (r = 0.61), p63 and ABCG2 (r = 0.64), and Krt14 and Notch 1 (r = 0.81), as would be expected (Supplementary Table 7).

Safety Outcomes

None of the reported recipient eye, donor eye, and systemic adverse events were serious, related, and unexpected (Supplementary Tables 8, 9, 10 and 11). One primary safety event occurred in the recipient eye (Supplementary Table 8); a bacterial infection (Cutibacterium acnes) occurring 8 months after transplant and attributed to chronic contact lens use. One participant (11) received a penetrating keratoplasty at the time of CALEC transplant due to necrotic stromal loss from chemical injury and one participant (7) underwent elective penetrating keratoplasty with cataract surgery for visual rehabilitation (Supplementary Table 12). There were 7 cases of corneal bleeding, 3 of which were under the graft and resolved early post-operatively (Supplementary Table 9). Epithelial defects in the donor eye 1-day post-biopsy ranged 2 to 36 mm2; all resolved within 1 week. One participant developed corneal neovascularization in the donor eye (area 0.8mm2) 4 weeks after biopsy that resolved 6 weeks later (Supplementary Table 10). Donor eye visual acuity at the final visit was within one line of baseline for all participants.

Secondary Outcome to Investigate Efficacy of Treatment

At the 3-month visit, 7 of 14 participants met the definition of complete success (50%, 95% CI [23%, 77%]), which was based on improvement in corneal surface integrity (decrease in epithelial defect or decrease in corneal surface staining if defect not present at baseline). The complete success rate increased to 79% [49%, 95%] at 12 months and remained similar (77%, [46%, 95%]) at 18 months (Table 3). Two participants (15%, [2%, 45%]) met the definition of partial success at 18 months based on the decrease in neovascularization or decrease in participant symptomology as measured by OSDI and SANDI scores, one participant was not a success, and one participant received a second CALEC transplant prior to 18 months (Table 3).

All participants were a complete success during at least one of the six protocol visits, and 9 of those remained a complete success at all subsequent visits (Fig. 3A–D, Supplementary Fig. 1A). Of the 5 remaining participants (2 examples shown in Supplementary Fig. 1B), 3 went on to second CALEC. Individual components of the efficacy outcome measure (epithelial defect surface area, corneal surface staining, neovascular area, OSDI score, and SANDE score) improved over time on average, (Fig. 4), were fairly stable upon improvement within participants (Fig. 3E–G, Supplementary Fig. 2), and mildly correlated with each other (Fig. 3H, Supplementary Fig. 3). Secondary clinical measures of recipient eye visual acuity and corneal opacification generally showed improvement from baseline (Supplementary Fig. 4).

(A) Slit lamp photos (B) Corneal neovascularization tracing and (C) Fluorescein staining for Participant 9, who met criteria for Complete Success at final endpoint (18 months after CALEC transplant). Participant had history of severe alkali burn, and prior to enrollment had ocular surface reconstruction with extensive conjunctivoplasty including resection of corneal pyogenic granuloma. At baseline, participant had stage III limbal stem cell deficiency with best corrected visual acuity of count fingers. From post-operative month 3 through postoperative month 15 participant met criteria for partial success and had waxing and waning small epithelial defects. At post-operative month 18, the participant had a stable and improved ocular surface with improved comfort, and met criteria for a Complete success. Final visual acuity (20/500) with hard contact lens was 20/80, limited by pre-existing corneal stromal scarring. D–G Participants 1, 3, 8, and 15 are marked with an asterisk (*) on all plots to indicate they had an epithelial defect at baseline. The 3-month, 12-month and 18-month visits were prespecified times of outcome assessment. D Efficacy outcome per participants from 3-month to 18-month visit. White color pertains to outcomes that could not be calculated due to missing efficacy component measurements due to missed/telemedicine visits. E Epithelial Defect Surface Area per Participant from Baseline through 18 months (F) Cornea Surface Staining Score per Participant from Baseline through 18 months (G) Neovascular Area per Participant from Baseline through 18 months. H Spearman Correlation among Component Measures of Efficacy (N = 14 participants, at 96 total visits). Spearman correlation coefficients calculated using measures of efficacy at multiple visits (Baseline, 3-month, 6-month, 9-month, 12-month, 15-month and 18-month). Repeated measures were accommodated by using a mixed model approach for p-values and clustered bootstrap methods for estimation of confidence intervals. Epithelial defect, cornea staining, neovascular area and OSDI scores are missing for N = 8 visits, and SANDE scores missing for N = 7 visits due to missed/telemedicine visits.

For each boxplot, the center line represents the median; the box limits represent the upper and lower quartiles; the whiskers represent 1.5x interquartile range; the individual points outside the box and whiskers represent the outliers. (A) Epithelial defect surface area (mm sq) across Baseline through 18-month visits, N = 14. B Corneal surface staining (NEI Grading scale 0-15) across Baseline through 18-month visits, N = 14. C Neovascular area (% of total area) across Baseline through 18-month visits, N = 14. D OSDI Score (Scale 0-100) across Baseline through 18-month visits, N = 14. E SANDE Score (Scale 0-100) across Baseline through 18-month visits, N = 14.

Although baseline clinical and manufacturing factors were not strongly associated with complete success at the 3-month visit, patients who were early complete successes tended to have less corneal opacification, shorter duration of disease, fewer reconstructive surgeries prior to transplant, fewer days from biopsy to end of culture, and higher iATP and CFE values (Supplementary Table 13). The high long-term success rate precluded a meaningful assessment of factors related to efficacy at 12 and 18-month visits.

Second CALECs

Three participants received a second CALEC transplant (Supplementary Table 14). No primary safety events were observed (Supplementary Table 15). One of the three reached complete success by the common study end visit (Supplementary Table 16, Supplementary Fig. 5).

Discussion

Although transplantation of ex vivo-cultivated autologous limbal stem cells is performed in other countries on a limited basis, procedures used to manufacture these products do not meet rigorous FDA standards and these products are not available in the United States. For example, CLET product approved in EU (Holoclar) and in Japan (Nepic) utilize 3T3 feeder cells along with serum and antibiotics in the cell growth media. To address this gap, we developed a novel standardized manufacturing protocol that met FDA requirements and undertook a clinical trial to evaluate the safety and to investigate the efficacy of CALEC tissue grafts in patients with LSCD15. Our findings show that transplantation of CALEC constructs in patients with both mild and severe forms of LSCD achieved corneal surface restoration with limbal epithelial cells and improved clinical symptoms. Fourteen participants received CALEC transplants and there were no serious safety events in the donor or recipient eye. Of these patients, 86% were a complete or partial success at 3 months, and 93% and 92% were a complete or partial success at 12 and 18 months, respectively, based on improvement in corneal epithelial surface integrity (complete success) or improvement in corneal vascularization and/or participant symptomatology as measured by OSDI and SANDI (partial success). This indicates that autologous CALEC grafts reconstituted epithelial cell homeostasis leading to improvement in corneal surface integrity, neovascularization, and patient symptomatology.

CALEC performed well in achieving the efficacy outcome for corneal surface integrity, 77% at 18 months. A recent meta-analysis of LSCT (Limbal Stem Cell Transplantation) outcomes by Le et al. reported that CLET similarly has an epithelial integrity success rate of 72%9. It is notable that all CALEC participants met complete success criteria during at least one visit, and most remained a complete success at all subsequent visits, indicating stability of corneal surface integrity over 18 months. Of the five exceptions, one (-07) became a partial success, attributable to expected ocular surface changes following an elective penetrating keratoplasty for visual improvement at 15 months. One (-14) became partial success due to the recurrence of epithelial defects, despite improved neovascularization and symptomatology (OSDI/SANDE). Three underwent second CALEC with varied outcomes at their final closeout visit (complete success at 9 months, partial success at 3 months, and not a success at 6 months, respectively. The same factors that made patients a candidate for second CALEC procedure likely selected patients with more severe underlying corneal damage and consequently result in diminished efficacy outcomes.

Lack of clinical endpoint standardization in LSCD has led to significant variation in reported outcomes in previous studies7,9,14,16,17,18. Newly developed objective clinical parameters of CALEC’s efficacy outcomes (corneal epithelial defect area, corneal fluorescein staining, and neovascular area) correlated well with each other, which may inform eligibility and outcome for future trials in LSCD. While the two symptom scores SANDE and OSDI were moderately correlated with each other, they were only weakly correlated with objective signs; a finding that is similar in dry eye disease19,20,21.

A favorable safety profile was demonstrated for the recipient eyes and the only primary safety event to occur was a bacterial infection 8 months after CALEC attributed to nocturnal bandage contact lens wear rather than CALEC itself. Transient corneal hemorrhage under the carrier amniotic membrane was observed, and has also been reported in other CLET constructs utilizing amniotic membrane9. Limbal biopsy from the donor eye (including second biopsy harvest for second CALEC transplant) was well tolerated, and eyes healed well without iatrogenic LSCD or other severe sequelae. The long-term stability of donor eyes for up to 4 clock hours of limbus harvest in autologous LSCT has previously been demonstrated22.

Our study established the feasibility of CALEC, with manufacturing success of 93%. Cellular expansion at P0 provided enough cells for quality control assays in addition to the generation of two CALEC constructs, with one used as a back-up graft during the surgery. Analysis of 28 manufactured constructs found moderate correlations of CFE with days from biopsy to P0, and most notably with iATP assay. CFE and iATP values were higher in the complete success group, which may suggest that these assays are consistent with the mechanism of action of the cellular product, in addition to being potential indicators of construct quality. Although CFE is commonly used in corneal epithelial cell therapy, the assay is difficult to scale and standardize as it takes at least 14 days for a readout and has high variability9,23. However, the iATP assay requires a lower number of cells at P0 and quantifies cellular proliferative potential that is easier to scale and may be evaluated as a product potency assay in future trials.

The extent of p63 positivity has previously been reported to predict better clinical outcomes after CLET7, as p6324 and in particular the p63α isoform24 are purported markers of limbal stemness. Our study did not find p63 or any other marker to be associated with efficacy outcomes. It is possible that the relatively severe nature of LSCD in our patient population led to outcomes being heavily influenced by recipient eye characteristics. Similarly, p63 did not correlate with outcome measures for the Nepic, another CLET construct16. Instead the clinical success of epithelial cell transplantation appears to depend primarily on factors specific to the recipient microenvironment (the limbal niche)25 and macro-environment (including adjacent eyelid and external disease)26 that ultimately support the graft. Indeed, Rama et al. found that in addition to p63, the severity of limbal damage and postoperative complications are factors significantly associated with limbal stem cell transplant outcome7. To a similar effect, the International LSCD Working Group has recommended optimization of the ocular surface prior to grafting4. In this trial, several patients had ocular surface reconstruction and surgical optimization of other recipient factors prior to enrolling in the trial. Nevertheless, patient-specific factors may have limited clinical improvement in some patients.

We noted correlations between several biomarkers tested. The negative correlation between Krt12 and Krt14 and Notch1 reveals the balance between limbal stem cell presence and corneal differentiation27. Presence of C/EBPδ, p63α, and Notch1 support self-renewal in limbal stem cells, while ABCG2 cells confirm putative stem cell properties7,28; thus, taken together, CALEC cultures showed dynamic expression of stem cell and epithelial markers, indicating active differentiation and self-renewal.

Overall manufacturing time was relatively consistent from biopsy to P0 (7 to 13 days, median 10 days). Time from P0 to end of culture varied more as limbal cells adjusted to in vitro expansion on the amniograft membrane. Serum-free media without supplemental growth factors was used throughout ex vivo processing. As these are autologous products, we expect that there will always be some level of inconsistency in ex vivo expansion. For example, now that there is a great deal of experience manufacturing autologous CAR T cells, it is evident that products that meet all release criteria cannot be manufactured for 10-20% of patients. One limitation of the manufacturing process for CALEC grafts is that the final product is not cryopreserved and must be surgically grafted within 24 hours after completion of the manufacturing process. The development of media and conditions that can maintain the viability and function of the CALEC graft for longer periods ex vivo will facilitate further clinical application of this approach. Furthermore, the next steps include the assessment of viability in the preservation media for longer periods of time and the assessment of long-distance shipments and cultivation of allogeneic epithelial stem cells that would allow a scaled-up production of cellular products.

The present study has several limitations. Our study had a disproportionate sex distribution, with only one female and 13 males. It is well established in the field that males are at a greater risk for the ocular surface and workplace injuries than females with reported ratios of 86:1829, 81:1930, 91:931, and 68.5:31.532. Our study population mirrors this trend, with 78.6% (11 out of 14 cases) of chemical/thermal burns occurring in males29,30,31,32,33. The study was initiated prior to the publication of the International LSCD Working Group’s consensus papers; therefore, the currently established grading criteria of LSCD were not utilized3,4. A post hoc classification of LSCD severity in our study participants noted 11 (79%) at stage III, 1 (7%) at stage IIB and 2 (14%) at stage IB. A randomized control CLAU arm was originally planned but was discontinued due to slow recruitment. CLAU procedures have shown success rates of approximately 70-80%, even though outcome measures are highly variable between reported studies9,23. Expert opinion varies on whether CLAU or SLET procedures are the most appropriate comparator to CALEC, as they represent distinct surgical approaches and risks to the donor eye8. Use of amniotic membrane alone has also been used for LSCD and is an important consideration for milder cases where residual LSC may still be preserved34. Future investigations of CALEC should include larger numbers of patients accrued at multiple centers, longer follow-up and randomized control design to better define outcomes and factors predictive of success.

In conclusion, CALEC presents high manufacturing success and good safety profile in this phase I/II clinical trial. The results of this trial provide strong support for further trials and will serve as a steppingstone for establishing cellular therapy products as viable options for patients with LSCD.

Methods

Ethics statement

Participants were compensated for their time and further details on recruitment, sample size determination, and data collection were previously published15.

Patients

All participants were enrolled at Massachusetts Eye and Ear (MEE). Five participants enrolled during the initial recruitment phase, August 22, 2016, to January 2, 2019, and 10 additional participants enrolled during open recruitment, August 19, 2019, to September 29, 2021 (Fig. 1). The protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, was approved by the MEE Institutional Review Board, and monitored and approved by the CALEC DSMB. The research reported here includes all relevant aspects of the study and any discrepancies from the protocol are explained. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. An Investigational New Drug Application was approved by the FDA (#16102). The trial is registered in clinicaltrials.gov NCT02592330 (registered October 29, 2015 prior to patient enrollment and enrollment is complete) and the full study protocol is publicly available at https://publicfiles.jaeb.org/CALEC_Protocol_v6_Feb_3_2022.pdf. A full de-identified study dataset will be available without restriction at https://public.jaeb.org/calec no later than 12 months after study completion.

Participants were 18 to <90 years old with unilateral LSCD as determined by conjunctivalization of the cornea defined by fibrovascular pannus more than 2 mm from the limbus into the cornea for ≥6 clock hours. Loss of normal limbal architecture as seen in LSCD was assessed by noting lack of limbal palisades of Vogt for ≥9 clock hours. The donor eye could not have conjunctivalization more than 2 mm from the limbus for ≥3 clock hours as previously published15.

During the initial safety and feasibility phase15, transplants were staggered to allow review of safety by an independent data and safety monitoring committee. After enrollment of 5 patients, the committee reviewed safety and efficacy data at least annually.

Intervention: Biopsy, Manufacturing and Transplant

Limbal biopsy, 2-stage manufacturing, transplant, and post-operative care followed standardized procedures which were previously reported15. In brief, the limbal biopsy of the unaffected eye (1 clock hour) was performed under topical anesthesia and placed in Hypothermosol-FRS animal component free solution (Biolife Solutions, Bothell, WA) for transfer in a reusable EVOTM transporting device (Biolife Solutions, Bothell, WA).

The manufacturing process is shown in Fig. 2A. In Stage 1, cells obtained from a limbal biopsy of the unaffected eye were grown to confluency on plastic (P0). In Stage 2, P0 cells were transferred to a de-epithelialized amniotic membrane (Amniograft) for further expansion. After reaching confluence (P1), CALEC constructs were harvested and delivered to the operating room in the 6-well plate using the EVOTM temperature-controlled transport container. Quality control testing was carried out on cells harvested at P0 and P1. Testing at P0 included cell count, viability (trypan blue), phenotype (flow cytometry, proliferation (iATP), colony formation, mycoplasma and sterility. Testing at P1 (final harvest) included cell count, viability (LDH), endotoxin, mycoplasma and sterility. Stage 1 was continued until 3-5 ×104 viable cells (P0) were available for transfer onto each amniograft. Once sufficient numbers of cells were available, the only additional release criteria at P0 were preliminary sterility (no growth on sample of supernatant obtained 24-48 hours prior to P0 harvest). P0 sterility cultures were maintained for a total of 14 days as required by the FDA and all cultures remained negative. P0 samples were also taken for colony forming assays, iATP and flow cytometry but these assay results were for information only. Release criteria at the end of limbal cell expansion on the amniograft membrane included preliminary sterility (no growth from culture supernatant obtained 24-48 hours prior to final end of culture), viability (measured by LDH release ≤150 U/L), endotoxin (measured by LAL ≤ 0.5 EU/ml), gram stain (no organisms seen), cell count (EVOS microscopy 0.4 to 1×106 cells per amniograft), and mycoplasma (negative by PCR assay measured on final harvest supernatant). Final product sterility assays were maintained for 14 days and all products showed no growth. Two constructs were manufactured from each biopsy; one was used for transplant and the second was used for assessment of biomarkers as described in Supplementary Table 1 if not needed as a backup for the transplant procedure.

At the time of CALEC transplantation, peritomy was performed and the fibrovascular pannus was meticulously dissected from the recipient eye, and in some cases with particularly robust pannus, mitomycin C (0.4 mg/mL) was applied to the fornices to prevent fibrosis. The CALEC construct was trephined with a 17 mm trephine and sutured with interrupted 10-0 nylon sutures at the limbus. A bandage contact lens (BCL) was placed on the eye. The postoperative regimen consisted of preservative-free moxifloxacin, and prednisolone (1%) eye drops. Additionally, serum tears were employed in an effort to enhance stratification in vivo. If epithelial defect was noted on the 1 or 2-week evaluations after the surgery, preservative-free methylprednisolone was added. Pathology of the excised pannus revealed findings consistent with LSCD.

Testing Performed

Patient evaluations are detailed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Corneal staining was graded according to the National Eye Institute (NEI) scale ranging from 0 (no staining) to 3 (severe) within each of five corneal zones (superior, nasal, central, inferior and temporal)35. Epithelial defect surface area was calculated from the greatest horizontal and vertical dimensions. A planimetric program (ImageJ) was used to evaluate corneal neovascular area from slit lamp photographs36. Participant symptomatology was measured by the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI)37 and Symptom Assessment in Dry Eye (SANDE)38.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of the study were feasibility and safety. The feasibility outcome was based on whether a limbal biopsy generated a viable construct for transplant. When all release criteria (including assessments of cell growth, cell viability, and sterility) were met for at least one of the two constructs, the feasibility outcome was considered a “manufacturing success”. The safety outcome was defined as the occurrence of any of the following events in the recipient eye during the 18 months of follow-up: (1) ocular infection (endophthalmitis or microbial keratitis), (2) corneal perforation, (3) graft detachment ≥50%.

The secondary outcome of the study was to investigate the efficacy of CALEC transplantation in the treatment of LSCD. This efficacy outcome was defined as a “complete success” based on improvement in corneal epithelial surface integrity. If epithelial defect was present at baseline, improvement was defined as a decrease in epithelial defect surface area by ≥75%; otherwise, if no epithelial defect was present at baseline, improvement was defined as a decrease in corneal surface staining by ≥50%. The efficacy outcome was defined as a “partial success” based on improvement in corneal vascularization (decrease in neovascular area by ≥25%) or participant symptomatology (decrease in OSDI or SANDE score by ≥25%). Detailed efficacy outcome definitions are provided in Table 3. Efficacy was assessed at 3, 12, and 18 months.

After 12 months, eligibility for a second CALEC procedure included the presence of epithelial defect >1 mm at 2 or more visits after the 3-month visit and the same recipient and donor eye eligibility as the original CALEC. Second transplant recipients were followed until a common study end date.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 15 provided >50% chance of observing adverse events with a true incidence of ≥5%. Associations among efficacy and manufacturing characteristics were assessed with Spearman correlation coefficients. Confidence intervals for Spearman correlation coefficients based on one point in time were calculated using the SAS PROC CORR procedure with a Fisher transformation and bias adjustment. When the Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated using measures of efficacy at multiple visits, the repeated measures were accommodated by using a mixed model approach for p-values and clustered bootstrap methods for the estimation of confidence intervals. Heatmaps displayed efficacy outcomes over time. Confidence intervals for estimated proportions were calculated using the SAS PROC FREQ procedure with exact binomial (Clopper-Pearson) methods. A least squares linear regression line is superimposed on some scatterplots. Confidence intervals for the difference in medians between two groups were calculated using the SAS PROC QUANTREG procedure. Side-by-side boxplots were used to visualize longitudinal patterns of clinical measures. A scatterplot matrix was used to summarize the association between components of the efficacy outcome measure. All P-values reported are 2-sided. All computations were completed using SAS version 9.4. The experiments were not randomized, and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All of the individual participant data collected during the trial, including de-identified participant data, a data dictionary defining each field in the data set, and the study protocol will be made available with unrestricted access to anyone who wishes to access the data for any purpose immediately following publication with no end date. Data are available indefinitely at https://public.jaeb.org/calec. The sharing of the public dataset has been approved by the study DSMB. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Tseng, S. C. Concept and application of limbal stem cells. Eye (Lond.) 3, 141–157 (1989).

Townsend, W. M. The limbal palisades of Vogt. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 89, 721–756 (1991).

Deng, S. X. et al. Global Consensus on Definition, Classification, Diagnosis, and Staging of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Cornea 38, 364–375 (2019).

Deng, S. X. et al. Global Consensus on the Management of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Cornea 39, 1291–1302 (2020).

Masood, F. et al. Therapeutic Strategies for Restoring Perturbed Corneal Epithelial Homeostasis in Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency: Current Trends and Future Directions. Cells 11 (2022).

Kenyon, K. R. & Tseng, S. C. Limbal autograft transplantation for ocular surface disorders. Ophthalmology 96, 709–722 (1989). discussion 722-703.

Rama, P. et al. Limbal stem-cell therapy and long-term corneal regeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 147–155 (2010).

Yin, J. & Jurkunas, U. Limbal Stem Cell Transplantation and Complications. Semin. Ophthalmol. 33, 134–141 (2018).

Le, Q., Chauhan, T., Yung, M., Tseng, C. H. & Deng, S. X. Outcomes of Limbal Stem Cell Transplant: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 138, 660–670 (2020).

Sangwan, V. S., Basu, S., MacNeil, S. & Balasubramanian, D. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET): a novel surgical technique for the treatment of unilateral limbal stem cell deficiency. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 96, 931–934 (2012).

Pellegrini, G. et al. Long-term restoration of damaged corneal surfaces with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. Lancet (Lond., Engl.) 349, 990–993 (1997).

Ghareeb, A. E., Lako, M. & Figueiredo, F. C. Recent Advances in Stem Cell Therapy for Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency: A Narrative Review. Ophthalmol. Ther. 9, 809–831 (2020).

Vazirani, J. et al. Surgical Management of Bilateral Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Ocul. Surf. 14, 350–364 (2016).

Jurkunas, U., Johns, L. & Armant, M. Cultivated Autologous Limbal Epithelial Cell Transplantation: New Frontier in the Treatment of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 239, 244–268 (2022).

Jurkunas, U. V. et al. Cultivated autologous limbal epithelial cell (CALEC) transplantation: Development of manufacturing process and clinical evaluation of feasibility and safety. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg6470 (2023).

Oie, Y. et al. Clinical Trial of Autologous Cultivated Limbal Epithelial Cell Sheet Transplantation for Patients with Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Ophthalmology 130, 608–614 (2023).

Sangwan, V. S. et al. Clinical outcomes of xeno-free autologous cultivated limbal epithelial transplantation: a 10-year study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 95, 1525–1529 (2011).

Nakamura, T., Inatomi, T., Sotozono, C., Koizumi, N. & Kinoshita, S. Successful primary culture and autologous transplantation of corneal limbal epithelial cells from minimal biopsy for unilateral severe ocular surface disease. Acta ophthalmol. Scandinavica 82, 468–471 (2004).

Bartlett, J. D., Keith, M. S., Sudharshan, L. & Snedecor, S. J. Associations between signs and symptoms of dry eye disease: a systematic review. Clin. Ophthalmol. 9, 1719–1730 (2015).

Nichols, K. K., Nichols, J. J. & Mitchell, G. L. The lack of association between signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye disease. Cornea 23, 762–770 (2004).

Tawfik, A. et al. Association of Dry Eye Symptoms and Signs in Patients with Dry Eye Disease. Ophthal. Epidemiol, 1–9 (2023).

Cheung, A. Y., Sarnicola, E. & Holland, E. J. Long-Term Ocular Surface Stability in Conjunctival Limbal Autograft Donor Eyes. Cornea 36, 1031–1035 (2017).

Shanbhag, S. S. et al. Autologous limbal stem cell transplantation: a systematic review of clinical outcomes with different surgical techniques. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 104, 247–253 (2020).

Pellegrini, G. et al. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3156–3161 (2001).

Amin, S., et al. The Limbal Niche and Regenerative Strategies. Vision (Basel) 5 (2021).

Liang, L., Sheha, H., Li, J. & Tseng, S. C. Limbal stem cell transplantation: new progresses and challenges. Eye (Lond.) 23, 1946–1953 (2009).

Sacchetti, M., Rama, P., Bruscolini, A. & Lambiase, A. Limbal Stem Cell Transplantation: Clinical Results, Limits, and Perspectives. Stem cells Int. 2018, 8086269 (2018).

Schlötzer-Schrehardt, U. & Kruse, F. E. Identification and characterization of limbal stem cells. Exp. Eye Res 81, 247–264 (2005).

Akgun, Z., Palamar, M., Egrilmez, S., Yagci, A. & Selver, O. B. Clinical Characteristics and Severity Distribution of Tertiary Eye Center Attendance by Ocular Chemical Injury Patients. Eye Contact Lens 48, 295–299 (2022).

Kate, A. et al. Demographic profile and clinical characteristics of patients presenting with acute ocular burns. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 71, 2694–2703 (2023).

Vergara, A. E. & Fuortes, L. Surveillance and epidemiology of occupational pesticide poisonings on banana plantations in Costa Rica. Int J. Occup. Environ. Health 4, 199–201 (1998).

Quesada, J. M., Lloves, J. M. & Delgado, D. V. Ocular chemical burns in the workplace: Epidemiological characteristics. Burns 46, 1212–1218 (2020).

Ahmmed, A. A., Ting, D. S. J. & Figueiredo, F. C. Epidemiology, economic and humanistic burdens of Ocular Surface Chemical Injury: A narrative review. Ocul. Surf. 20, 199–211 (2021).

Tseng, S. C., Prabhasawat, P., Barton, K., Gray, T. & Meller, D. Amniotic membrane transplantation with or without limbal allografts for corneal surface reconstruction in patients with limbal stem cell deficiency. Arch. Ophthalmol. (Chic., Ill.: 1960) 116, 431–441 (1998).

Lemp, M. A. Report of the National Eye Institute/Industry workshop on Clinical Trials in Dry Eyes. CLAO J.: Off. Publ. Contact Lens Assoc. Ophthalmol. Inc. 21, 221–232 (1995).

Dastjerdi, M. H. et al. Topical bevacizumab in the treatment of corneal neovascularization: results of a prospective, open-label, noncomparative study. Arch. Ophthalmol. (Chic., Ill.: 1960) 127, 381–389 (2009).

Schiffman, R. M., Christianson, M. D., Jacobsen, G., Hirsch, J. D. & Reis, B. L. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch. Ophthalmol. (Chic., Ill.: 1960) 118, 615–621 (2000).

Schaumberg, D. A. et al. Development and validation of a short global dry eye symptom index. Ocul. Surf. 5, 50–57 (2007).

Acknowledgements

A listing of study personnel appears in the Supplementary Appendix. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UG1EY026508 (Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary), UG1EY027726 (Cell Manipulation Core Facility), and UG1EY027725 (Coordinating Center). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Preclinical development of the CALEC manufacturing process was supported by the Production Assistance for Cellular Therapy (PACT) Program of the NHLBI (contract HHSN268201000009C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

U.V.J.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing original draft, resources, supervision, funding acquisition; A.R.K.: investigation, writing original draft; J.Y.: investigation, writing original draft; A.A.: project administration, resources, supervision, writing original draft, funding acquisition; M.M.: formal analysis, writing review & editing; L.S.: data curation, formal analysis, writing original draft; L.K.J.: investigation, writing review & editing; M.P.: investigation, writing review & editing; S.L.: investigation, writing review & editing; A.G.: investigation, writing review & editing; H.N.: investigation, writing review & editing; K.L.S.: investigation, writing review & editing; D.E.H.R.: investigation, writing review & editing; H.D.: investigation, writing review & editing; R.D.: investigation, writing review & editing; M.A.: methodology, validation, writing review & editing; J.R.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, resources, supervision, writing review & editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Patent pending (UVJ, R.D., J.R., and M.A.). U.V.J. and R.D. have financial interests in OcuCell, Inc. This company is developing living ophthalmic cell-based therapies for treating eye disease. U.V.J. and R.D. interests were reviewed and are managed by Mass Eye and Ear Infirmary and Mass General Brigham in accordance with their competing interest policies. M.A. serves on the scientific advisory board for OcuCell, Inc. JR receives research funding from Kite/Gilead, Novartis and Oncternal and serves on Scientific Advisory Boards for Astraveus, Garuda Therapeutics, LifeVault Bio, Smart Immune, Tolerance Bio, and TriArm Therapeutics. ARK, JY, AA, MM, LS, LKJ, MP, SL, AG, HN, KLS, DEHH, and HD declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kapil Bharti, Jan Rekowski, Zhulin Yin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A listing of non-author contributors appears in the Supplementary Appendix.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jurkunas, U.V., Kaufman, A.R., Yin, J. et al. Cultivated autologous limbal epithelial cell (CALEC) transplantation for limbal stem cell deficiency: a phase I/II clinical trial of the first xenobiotic-free, serum-free, antibiotic-free manufacturing protocol developed in the US. Nat Commun 16, 1607 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56461-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56461-1

This article is cited by

-

Simultaneous generation of transplantable RGC-like and corneal progenitor cells from hiPSCs using a dual-lineage platform

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2025)

-

3D Bioprinting of Cellular Therapeutic Systems in Ophthalmology: from Bioengineered Tissue to Personalized Drug Delivery

Current Ophthalmology Reports (2025)