Abstract

Biological soil crusts (biocrusts) cover the majority of the world’s dryland ground and are a significant component of the vegetation-free surface of the planet. They consist of an intimate association of microbial organisms, lichens, bryophytes and fungi. Biocrusts are severely endangered by anthropogenic disturbances despite their importance. The genus Bracteacoccus (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyta) is a ubiquitous component of biocrusts from extreme environments. Here, we present the chromosome-level genome sequences of two Bracteacoccus species, B. bullatus and B. minor. Genome comparisons with other Archaeplastida identify genomic features that highlight the adaptation of these algae to abiotic stresses prevailing in such environments. These features include horizontal gene transfer events mainly from bacteria or fungi, gains and expansions of stress-related gene families, neofunctionalization of genes following gene duplications and genome structural variations. We also summarize transcriptional and metabolic responses of the lipid pathway of B. minor, based on multi-omics analyses, which is important for balancing the flexible conversion of polar membrane lipids and non-polar storage lipids to cope with various abiotic stresses. Under dehydration and high-temperature stress conditions B. minor differs considerably from other eukaryotic algae. Overall, these findings provide insights into the genetic basis of adaptation to abiotic stress in biocrust algae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drylands (arid and semi-arid ecosystems) encompass over 40% of the terrestrial surface of the Earth, holding a significant portion of the global organic soil carbon1. Biological soil crusts (biocrusts), complex communities of cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algae, lichens, bryophytes, fungi, and heterotrophic bacteria and protists, living in intimate association with each other in the top millimeters of soil, constitute up to 70% of dryland ground cover2,3. Biocrust organisms in drylands are adapted to various abiotic stresses such as drought, large fluctuations of temperature and salinity, high solar radiation, and low nutrient conditions among others, and need to respond rapidly to changes in their microenvironment. They provide important ecosystem services such as creating and maintaining fertility in otherwise infertile soils by fixing both carbon and nitrogen, controlling soil erosion, capturing nutrient-rich dust, and regulating surface hydrology2. Biocrusts are vulnerable to climate change and other anthropogenic disturbances and have therefore attracted increased attention in recent years including restoration efforts4,5,6. Because of their specific adaptations, biocrust organisms have considerable biotechnological potential with respect to e.g. enzymes, antioxidants, antimicrobials, biosurfactants, polysaccharides, and lipids7.

Among eukaryotic algae, species of Bracteacoccus (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyta) are common constituents of biological soil crusts worldwide, ranging from polar to tropical habitats8. They have been found in habitats as diverse as barren glacial soils and green ice9,10,11,12, hot and cold deserts13,14,15, caves16,17,18, volcanic soils19,20, coastal and inland dunes21,22 and anthropogenically polluted soils23,24,25,26,27.

Given their wide distribution in biocrusts and special adaptive properties, species of Bracteacoccus, in particular, Bracteacoccus bullatus and Bracteacoccus minor, have been investigated for biotechnological applications28. Representatives of the genus contain up to 63% lipids in the dry biomass and thus have been investigated for biofuel production29,30,31,32. New strains of B. bullatus have been isolated from soil and snow with a balanced ratio of ω-6/ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, making them potentially suitable as food additives33,34. A maximum content of ω-3 fatty acids (26.1% of total fatty acids) has been determined for B. minor strain SAG 61.8035. Several species of Bracteacoccus (there are currently 16 species recognized in the genus (AlgaeBase: https://www.algaebase.org) can be grown heterotrophically on glucose as the sole carbon source facilitating the use of fermentation technology36,37. B. minor has previously been shown to produce secondary carotenoids in substantial quantities upon nitrogen starvation30. In a new strain of B. aggregatus (a close relative of B. minor), simultaneous production of β-carotene and astaxanthin was reported, with 13% and 48% of β-carotene and astaxanthin, respectively, of the total carotenoids38. In contrast to other carotenogenic chlorophytes, this strain was highly resistant to UV-A stress, presumably reflecting adaptation to its biocrust habit39.

In this contribution, we established chromosome-level genome assemblies of the authentic strains of B. bullatus and B. minor, and performed comparative genome analyses with other Viridiplantae (and with Archaeplastida) as well as RNA-Seq analyses under different abiotic stress conditions to explore genomic adaptations of these terrestrial algae to their biocrust environment. We identified several genes potentially involved in these adaptations that were obtained from bacteria or fungi by horizontal gene transfer (HGT). Besides HGT, gene family gains and expansions as well as neofunctionalization following gene duplications and genome structural variations likely contributed to enhanced stress tolerance in the two Bracteacoccus strains. A multi-omics analysis of lipid metabolism in B. minor provided evidence that lipid metabolism under dehydration and high-temperature stress differed fundamentally from that of other terrestrial algae probably highlighting specific adaptation to dryland biocrusts.

Results and Discussion

Genome sequencing, assembly and annotation

K-mer analyses based on short-read data implied an estimated genome size of 68.85 Mb and 65.99 Mb for B. bullatus and B. minor, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, both species are haploid supported by ploidyNGS and K-mer analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). A total of 96.8 Gb and 81.2 Gb 10X reads were generated and used for scaffolding the assembled genomes of B. bullatus and B. minor, respectively (Supplementary Data 1). We achieved de novo assembly of 74.38 Mb for the B. bullatus genome and 64.66 Mb for the B. minor genome using the Supernova assembler (see “Library preparation, sequencing and genome assembly” of Methods for details) (Supplementary Data 2).

A total of 1811 and 2817 scaffolds were assembled in the B. bullatus and B. minor genomes with scaffold N50 lengths of 1.06 Mb and 3.07 Mb, respectively (Supplementary Data 2). The G + C content of B. bullatus and B. minor is 54.28% and 54.40%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 2). Using Hi-C contact information, contigs of both B. bullatus and B. minor were further anchored onto 19 pseudochromosomes (Supplementary Fig. 3), which covered 96.0% and 95.8% of the respective assembled sequences (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Data 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). To assess the quality of the B. bullatus and B. minor genome assemblies, a total of 96.1% and 96.8% of RNA-seq reads were aligned to the final assemblies, respectively (Supplementary Data 1). Besides, BUSCO assessment (chlorophyta_odb10) results showed that 94.3% and 93.8% of the conserved chlorophyte genes were captured in the genomes of B. bullatus and B. minor, respectively (Supplementary Data 3). Taken together, high-quality genome assemblies of two Bracteacoccaceae (B. bullatus and B. minor) were obtained.

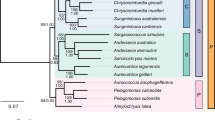

a Light micrographs of two Bracteacoccaceae, B. bullatus (top) and B. minor (bottom). Inset shows the typical bulbous extensions of the cell wall in B. bullatus. b Circos plot of genome features for B. bullatus and B. minor genomes. a–j Concentric circles from outermost to innermost include: pseudochromosome, GC content, gene number, LTR number, Repeat number, Copia number, Gypsy number, SNP distribution, Indel distribution, and synteny regions in the genomes of B. bullatus and B. minor. c Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of Bracteacoccaceae and related algae based on the concatenated sequences of 589 single-copy genes. The bootstrap values of all branches were 100% (n = 500). Divergence time of two Bracteacoccus species is highlighted in bold. The red circle represents the time point chosen as calibrator. The proportion of expanded, contracted, gained, and lost gene families are shown in pie charts with different colors. d The Venn diagram shows the number of gene families shared and unique between B. bullatus and B. minor genomes. e A Venn diagram depicting the shared and unique gene families of the two Bracteacoccaceae in comparison with representatives from four other families of Sphaeropleales.

Subsequently, we performed annotation of repeat elements (REs) and protein-coding genes for B. bullatus and B. minor. The two genomes contained 7.00 Mb (9.41%) and 5.60 Mb (6.44%) REs, an intermediate percentage of their genomes, compared to other chlorophytes but lower than in two related families (Scenedesmaceae and Selenastraceae) of the Sphaeropleales (Supplementary Data 4 and 5). Similar to most Chlorophyta, LINE was identified as the most abundant REs40, occupying ~4.98% and ~4.69% of the genomes of B. bullatus and B. minor, respectively. The annotation of the two genome assemblies contains 16,218 and 13,973 protein-coding genes in the B. bullatus and B. minor genomes, respectively (Supplementary Data 2). Notably, the average gene length between B. bullatus (2855 bp) and B. minor (3143 bp) was slightly different (Supplementary Data 2).

Phylogeny and gene family analysis

To reveal the phylogenetic position of the Bracteacoccaceae, a maximum-likelihood tree was constructed from an alignment of 589 orthologues of single-copy nuclear genes from 18 representative species. Our phylogenetic tree placed Bracteacoccaceae as the sister family to Chromochloridaceae in the Sphaeropleales (Fig. 1c). A close relationship between the two families has also been recovered in recent phylogenetic analyses of plastid-encoded genes41,42. The molecular dating results suggest that the divergence time of B. bullatus and B. minor is approximately 110 Mya (see “Gene family analysis and phylogenetic reconstruction” of Methods for details).

Dynamic changes in gene families play an important role in driving phenotypic diversity and adaptive evolution43. Based on the fully resolved phylogeny, we found that 229 gene families had expanded, and 23 gene families contracted at the ancestral node of the two Bracteacoccaceae. However, 1395 and 94 gene families were gained and lost, respectively (Fig. 1c). Functional enrichment analysis of the expanded gene families showed significant clustering of 13 KEGG metabolic pathways, including ‘nitrogen metabolism’, ‘fatty acid elongation’ and ‘cutin, suberin, and wax biosynthesis’ etc. The gained gene families were significantly enriched in 15 KEGG pathways such as ‘MAPK signaling pathway -plant’, ‘plant-pathogen interaction’ and ‘fatty acid biosynthesis’ (Supplementary Data 6). Comparative analyses of gene families between B. bullatus and B. minor revealed that 10,188 gene families were shared between the two, while 2555 and 2734 gene families were unique in B. bullatus and B. minor, respectively (Fig. 1d). The unique genes of B. bullatus were significantly enriched in ‘Tropane, piperidine and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis’, which might be associated with adaptation to desiccation stress or exposure to heavy metals44,45,46,47. Unique genes from B. minor were mainly related to nitrogen transport and storage including ‘Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis’, ‘Alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism’, and ‘Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism’ (Supplementary Data 7). The results suggested diversity of genome evolution within Bracteacoccaceae species.

We further compared gene families in the Bracteacoccaceae with those of four other species of Sphaeropleales, Chromochloris zofingiensis, Mychonastes homosphaera, Tetradesmus obliquus, and Monoraphidium neglectum (Fig. 1e). We found that 39.4% (4011 of 10,188 total) of the gene families in the Bracteacoccaceae were shared among all six species, the Bracteacoccaceae sharing most gene families 82.5% (8401 of 10,188 total) with C. zofingiensis, which is consistent with their sister group relationship to C. zofingiensis (Fig. 1c). Overall, 42.8% (4362/10,188) of gene families were Bracteacoccaceae-specific (Fig. 1e). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that these specific gene families mainly referred to ‘MAPK signaling pathway –plant’, ‘Plant-pathogen interaction’, ‘Plant hormone signal transduction’, and ‘Biosynthesis of amino acid’, etc. (Supplementary Data 7), which were reported to be related with the resistance to stress, signal transduction and physiological development in plants. Therefore, these Bracteacoccaceae-specific gene families might endow them with unique capabilities for adaptation of biocrust habit.

Adaptive evolution in Bracteacoccaceae

We performed a genome-wide analysis of transcription factors (TFs) in the two Bracteacoccaceae genomes based on domain characters from TAPscan (see “Detection of key candidate functional genes” of Methods for details). In total, 396 and 379 TF genes were identified in the genomes of B. bullatus and B. minor, respectively, which is remarkably higher ( ~ 18%) than in other sequenced Sphaeropleales, except the sister lineage C. zofingiensis, in which the number is similar (369; Supplementary Data 8). Overall, 15 TFs expanded (the gene copy number >1.5-fold) in the Bracteococcaceae compared to the average of other Sphaeropleales genomes evaluated (Supplementary Data 8). The expansion was particularly pronounced in TRAF, GNAT, and mTERF, which play key roles in the development and stress responses of plants (Fig. 2a)48,49,50. Eleven TFs contracted (minimum >1.5-fold) in the Bracteacoccaceae compared to the average of other Sphaeropleales genomes analyzed (Supplementary Data 8) and one TF was lost (CCAAT_Dr1) in the Bracteacoccaceae compared to other Spaeropleales.

a Comparison of the number of representative expanded and HGT-derived gene families among selected Archaeplastida (The top three expansion genes are shown in the figure, see Supplementary Data 10 for details). Bacteria- and fungi-derived HGTs are marked with different shapes. b Maximum-likelihood tree of Nickel-binding periplasmic protein (NIKA) rooted with bacteria. c Maximum-likelihood tree of Iron transport multicopper oxidase (FETC) rooted with bacteria. Bracteacoccaceae sequences are highlighted with red and blue triangles, respectively. The red asterisk denotes the branch of the putative horizontal gene transfer (HGT). FETC Iron transport multicopper oxidase fetC, NIKA Nickel-binding periplasmic protein, hlyA Hemolysin, HPO Heme peroxidase, MFS major facilitator superfamily, KHA Cation/hydrogen exchanger, Cry8Ea1 insecticidal delta-endotoxin Cry8Ea1 family protein, DFG5 Mannan endo-1,6-alpha-mannosidase DFG5, GH1 beta-galacto-sidase, GH26 glycosyl hydrolase 26, GH28 glycosyl hydrolase 28, MNN9 Mannan polymerase complex subunit mnn9, EAG Endo alpha-1,4 polygalactosaminidase, CEEP Cellobiose 2-epimerase. Gene abbreviations are also explained in Supplementary Data 18.

In addition to expanded TFs, we found an expansion of gene copy numbers in the Bracteacoccaceae in several gene families that are generally involved in antioxidant defense systems in plants51,52. In particular, 14 Peroxiredoxin homologs were identified in B. bullatus and B. minor, a > 1.5-fold expansion compared to Volvocales and the average of other Sphaeropleales, and the same number compared to Chromochloridaceae (Supplementary Data 9).

Algae live in close association with other microbes like fungi and bacteria (especially in the soil habitat), thus it was of interest to search for horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events in the two Bracteacoccus genomes. Using a phylogeny-based HGT identification pipeline53, we systematically searched for putative HGT-acquired genes (see “Identification and phylogenetic analysis of candidate horizontal gene transfer (HGT) genes” Methods for details). A total of 181 gene families (360 genes) were identified as HGT-acquired candidates in the two genomes, which included HGT gene families that might have been acquired in the common ancestor of the Sphaeropleales, in the ancestor of the two Bracteacoccaceae, or on the terminal branches of the two Bracteacoccus species. Most of the HGT candidates (112 gene families, 62%) were predicted to have been acquired from soil bacteria, followed by fungi (20%) and other donors (18%) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 5–18, Supplementary Data 10). The functional enrichment revealed that total HGT families were enriched in GO categories related to the ‘oxidation-reduction process’, ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’, and ‘cation transport’ etc. (Supplementary Fig. 4). We further divided these HGT-acquired families into three categories: basic/secondary metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, and stress response (Supplementary Data 10). Seven HGT gene families belonging to the Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) are probably involved in cell wall and polysaccharide metabolism54. Two of which have no clear functional annotation but contain glycosyl hydrolase 26 and 28 domains, respectively (Supplementary Data 10). The other five CAZyme families are Cellobiose 2-epimerase (CEEP)55, Mannan polymerase complex subunit MNN956 (GT62), Mannan endo-1,6-alpha-mannosidase DFG557 (GH76), Endo alpha-1,4 polygalactosaminidase EAG58 (GH114), and beta-galactosidase59 (GH1). Phylogenetic trees showed that CEEP, MNN9, GH26, GH28 and GH1 were likely acquired from bacteria and fungi in the common ancestor of the Sphaeropleales, and the bacteria-derived GH76 might have been obtained in the common ancestor of the Chromochloridaceae and Bracteococcaceae. Notably, the bacteria-derived EAG (GH114) was Bracteacoccaceae-specific (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 11–17).

In addition, seven HGT families were found to be associated with stress resistance. For example, two copies of insecticidal delta-endotoxin Cry8Ea1 with transcript support were only identified in the B. minor genome, and might have been acquired from bacteria based on the phylogenetic analysis (Supplementary Fig. 10). Expression of bacterial delta-endotoxin into crops protected them against insect attack60,61. We therefore hypothesize that the bacteria-derived Cry8Ea1 may have a similar function in B. minor. B. bullatus was isolated from a heavy metal-contaminated dump site, and interestingly two HGT candidates were identified in both genomes namely iron transport multicopper oxidase (FETC) and nickel-binding periplasmic protein (NIKA), which participate in the metabolism of metals and heavy metal tolerance62,63,64. Within the Sphaeropleales, NIKA genes were only found in the sister families Bracteacoccaceae and Chromochloridaceae (C. zofingiensis). Phylogenetic analysis suggested that NIKA might have been acquired from bacteria earlier in chlorophyte evolution, and maintained in the two families of terrestrial Sphaeropleales (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 6). FETCs are ubiquitously present in bacteria and fungi and no homologs were found in embryophytes (Fig. 2c). Our results showed that FETC was present in Sphaeropleales, three gene copies each in B. bullatus and B. minor, two each in T. obliquus and H. reticulata, and one in M. homosphaera. Further phylogenetic analysis indicated that the FETC of Sphaeropleales likely originated by HGT from fungi (rotifers probably obtained their FETC independently from fungi, Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 5). We suggest that the HGT-derived and expanded gene families in the Bracteacoccaceae play a role in coping with stresses that prevail in desert soils and heavy metal-contaminated terrestrial environments.

Genome structural variation between two Bracteacoccaceae

Genome structural variation (SV) is usually associated with the evolution of phenotypic characteristics65. The genome sequence alignment between the two Bracteacoccaceae reveals high collinearity, although the B. bullatus genome size is approximately 10 Mb larger than that of B. minor (Fig. 3a).

a Genome collinearity in B. bullatus and B. minor. The heatmap displays the distribution of structural variant (SV) numbers on the chromosomes. b Examples of two PAV between genomes of B. bullatus and B. minor. Depicted areas in blue show collinear blocks between two genomes, and each rectangle with the arrow represents one gene. c The distribution of SV lengths between the genomes of B. bullatus and B. minor. d The bar graph shows the statistics of the location distribution of PAV (presence/absence variation) in gene parts. e The KEGG enrichment of PAV affected genes in B. bullatus and B. minor (The gene covering > 80% PAV regions was treated as a PAV-related gene). P-value was calculated by Fisher’s exact test. BB-A genes absent in B. bullatus; BB-P genes present in B. bullatus; BM-A genes absent in B. minor; BM-P genes present in B. minor.

A total of 214,181 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 3802 indels (length <50 bp) were identified between B. bullatus and B. minor based on comparative genome analysis, and both were mainly distributed on the longest pseudochromosome No.14 of B. bullatus and B. minor (Supplementary Data 11). Moreover, characterization of presence/absence variations (PAVs) showed that there were 34.36 Mb discrepant segments between the two species, among which 3659 and 3700 segments were absent in B. bullatus and B. minor, respectively. There were 3659 genes in B. bullatus and 3188 genes in B. minor in these PAV regions (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 12). In B. bullatus, these genes were significantly enriched in KEGG pathways including ‘tryptophan metabolism’ and ‘carotenoid biosynthesis’, both known to play crucial roles in abiotic stress responses66,67. In B. minor, genes distributed in the PAV region were mainly associated with ‘lipoic acid metabolism’, which has been suggested to improve the tolerance of plants to a wide array of abiotic stresses68,69 (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Data 13).

Close examination suggested that many insertion-type SVs might explain the divergence of the phenotypic characteristics between the two Bracteacoccaceae. For example, two insertions (54 Kb and 65 Kb) on pseudochromosomes No.1 and No. 16 of the B. bullatus genome both contained 4 copies of prolyl 4-hydroxylase that were arranged as a tandem array (Fig. 3e). Prolyl 4-hydroxylase catalyzes the post-translational formation of 4-hydroxyproline, an important constituent of many plant cell wall glycoproteins such as extensins, hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins, lectins, and arabinogalactan proteins70. Thus, our finding on the SVs of Prolyl 4-hydroxylase expansion could be related to cell wall modifications of B. bullatus, resulting in the “bullatus”-type extensions characteristic (Fig. 1a)8,34. Another example involves the insertion of an SV (36 Kb) on pseudochromosome No. 1 of the B. minor genome, resulting in the presence of two copies of tripeptidyl-peptidase (Fig. 3e), which may contribute to the degradation of oxidized proteins in response to environmental stresses71.

Evolutionary novelties in the lipid metabolic pathway of Bracteacoccaceae

Because of the high lipid accumulation of Bracteacoccaceae in culture8,30,32,33,34, we compared the number of lipid metabolic pathway-related genes among the genomes of two Bracteacoccaceae and other representative algae (Fig. 4a). The Bracteacoccaceae contain a similar number of fatty acid biosynthesis and TAG assembly genes compared to other Sphaeropleales but the copy numbers of KAR, DGAT and FAD were >1.5-fold higher than the average gene copy number of these genes in other representative chlorophyte taxa (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 14). In particular, KAR also exhibited a higher gene copy number ( > 2-fold) than the average gene copy number of the other Sphaeropleales. DGAT catalyzes the last step in TAG synthesis in the Acyl-CoA-dependent pathway, which plays a key role in TAG synthesis and lipid turnover in Sphaeropleales72. The FAD gene family is evolutionarily complex in plants, and is important in plant development and acclimation to environmental stresses by introducing double bonds into fatty acids73. B. bullatus and B. minor encode 17/15 FAD homologs (including FAD, SAD and SLD), respectively, similar to C. zofingiensis (17). Phylogenetic analysis showed that FADs of B. bullatus and B. minor were divided into FAD2, FAD3/7/8, FAD4, FAD5, FAD6, SAD and SLD subgroups. Interestingly, our analysis identified a unique FAD clade, “FAD-New”, in the genomes of Bracteacoccaceae, other Sphaeropleales, and the terrestrial Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, presumably acquired from soil bacteria (Alphaproteobacteria) via HGT (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 19). We also observed genes upstream and downstream of FAD-New in the Bracteacoccaceae genome are all Viridiplantae genes, and displayed normal expression. We assumed that the evolutionary novelties in the lipid metabolic pathway of the Bracteacoccaceae might relate to their specific habitats.

a Heat map showing the comparison between the number of key genes involved in lipid metabolism among Bracteacoccaceae and other representative Archaeplastida (see Supplementary Data 14). The genes highlighted in red represent expanded gene families in Bracteacoccaceae compared to the average of other Chlorophyta. Histogram showing the total number of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism. b Phylogenetic tree of fatty acid desaturases (FAD) of Bracteacoccaceae and other representative taxa. Colored branches and node symbols in the phylogenetic tree represent taxonomic distribution. Gene numbers are shown in each clade for selected Chlorophyta. The original tree can be found in Supplementary Fig. 19. Gene abbreviations are explained in Supplementary Data 18.

Stress-induced transcriptional response in B. minor

Lipid composition and production in oleaginous microalgae are influenced by various abiotic stimuli69,74. In turn, changes in cellular lipid composition are also effective strategies for a plant/an alga to cope with environmental stress68,75,76. To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms of stress-induced and photo-/heterotrophic lipid accumulation in the Bracteacoccaceae, we performed transcriptome profiling of B. minor cultured under; 1) dehydration (4hr-Dehy and 24hr-Dehy); 2) nitrogen starvation (NS), 3) high temperature (HT), 4) mixotrophic Glucose-Light (GL) and heterotrophic Glucose-Dark (GD) conditions (here GL served as the control for GD) (see details in Methods).

Our principal component analysis of RNA-seq data derived from samples cultured under different conditions showed high consistency for all biological replicates of each experimental and control group (Supplementary Fig. 20). Likewise, a high correlation coefficient was also observed for the metabolome data (Supplementary Fig. 20). A total of increase/decrease of transcript abundance (TA) of 2682/3035; 3531/4022; 1259/1977; 2251/3011; 2658/2968 was observed when B. minor was cultured under 4hr-Dehy, 24hr-Dehy, NS, HT, and GD conditions compared to their corresponding controls, respectively (Fig. 5a; Supplementary Figs. 21, 22). The 24-h delay led to a much higher number of changes in transcript abundance compared to the other conditions. In addition, we found that the abundance of only 121 gene transcripts significantly changed under all five conditions, whereas 29%, 30%, 30%, 28% and 34% of the genes (accounting for the total number of genes with significant changes in TA levels) changed their TA specifically under 4hr-Dehy, 24hr-Dehy, NS, HT and GD conditions, respectively (Fig. 5c), suggesting that the five conditions have different effects on the B. minor cells (Supplementary Data 15).

a comparison of increased and decreased TAs under four types of environmental conditions. b UpSet plot showing overlap among increased/decreased TAs in B. minor under different environmental conditions. c GO functional enrichment (biological process) for the increased and decreased TA of genes under the four types of environmental conditions in B. minor. Bubble size indicates the generality of the GO term in the underlying Gene Ontology Annotation (GOA) database. d Bar charts showing the average content level of total lipids and main subtype lipids of three biological replicates in B. minor in each environmental condition. Error bars represent standard error (n = 3), letters (abc, xyz, opq) and asterisks denote significant differences (t-test, P < 0.05, see exact P-value in Supplementary Data 17), ns no significance. DC Dehydration Control, 4 hr: under dehydration for 4 h, 24 hr: under dehydration for 24 h, Dehy Dehydration, NC Nitrogen Starvation Control, NS Nitrogen Starvation, HC High Temperature Control, HT High Temperature, GT Glucose-Light, GD Glucose-Dark, GL Glycerolipids, FFA Free Fatty Acids, GP Glycerophospholipids, PR Prenol Lipids, SP Sphingolipids. Abbreviations are explained in Supplementary Data 18.

Effects of abiotic stresses on lipid metabolism in B. minor

Lipids are mainly divided into five components, Glycerolipids (GL), Glycerophospholipids (GP), Free Fatty Acids (FFA), Prenol lipids (PR), and Sphingolipids (SP)77,78. B. minor mainly accumulated the first three types of lipids, the latter two were barely detectable (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 23, Supplementary Information for lipids detection). Accumulation of FFA is mainly through the de novo FFA biosynthetic pathway, while GL and GP are mainly generated through the Kennedy pathway and membrane lipid metabolism, respectively. Additionally, lipid metabolism typically balances the levels of FFA, GL, and GP through conversion and turnover among these three lipid types to respond to environmental changes in plant cells79.

We observed that the 4hr-Dehy caused a significant decrease in both GL and GP levels, but an increase of the FFA level compared to the control (Fig. 5d). Interestingly, slightly increased GL levels, more than 3-fold higher GP levels, and significantly decreased FFA levels were observed in B. minor under 24-hour Dehy compared to the control. This suggests that short-term Dehy stress leads to a significant decrease in GL and GP levels and an increase in FFA, while long-term Dehy stress has the opposite effect. In brief, the total lipid level of 4hr-Dehy decreased by almost half while that of 24hr-Dehy increased by 74% compared to the control, respectively (Fig. 5d).

Although total lipid levels of B. minor showed no significant change under HT conditions, different subtypes of lipids did (Fig. 5d, the significance changes for metabolites: P-value < 0.05, the detail P-value see Supplementary Data 17). For example, the level of FFA and GP exhibited the most dramatic changes, the former decreased, and the latter increased under HT conditions. In accordance with the findings of a previous study on other chlorophytes80, we observed that the total lipids of B. minor increased significantly under NS conditions (Fig. 5d), and the increase of GL-type lipids was the main factor in the increase of total lipids. Furthermore, the amount of FFA also increased, while the GP level showed a significant decrease in B. minor under the NS condition compared with the control (Fig. 5d). As in the NS condition, the total GL-type lipids of B. minor also exhibited a remarkable increase in the GD condition compared to the control (Fig. 5d). Since, however, both FFA- and GP-type lipids decreased significantly compared to the control, the amount of total lipids in the GD condition did not differ significantly from the control (Fig. 5d).

Effects of abiotic stresses on free fatty acid biosynthesis in B. minor

To further evaluate the response mechanism of lipid metabolism under different conditions, we first investigated the changes in FFA composition and TA profile of genes related to the de novo FFA biosynthesis pathway in B. minor.

The main components of FFA in B. minor were C18-type and C16-type FFA, the other types of FFA were much less abundant than these two (Fig. 6a). We also compared the saturated with the unsaturated FFA levels, and found that the unsaturated FFA content of B. minor was much higher than that of the saturated FFA (Fig. 6b). Unsaturated FFA contents decreased significantly under 24hr-Dehy, HT, and GD conditions compared to controls, whereas they exhibited an increase under 4hr-Dehy and NS conditions (Fig. 6b). Further comparison of the composition of C18-type and C16-type FFA showed that levels of C18 FFA and C16 FFA both increased significantly under 4hr-Dehy and NS stresses, but decreased significantly under 24hr-Dehy and HT conditions (Fig. 6a). In the GD condition, the level of C18-type FFA was lower than in the GL condition, whereas the opposite was observed for C16-type FFA levels (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, the levels of all C18 (C18:0~4) and C16 (C16:0~3) subtype FFA were significantly higher under 4hr-Dehy, and lower under 24hr-Dehy compared to the control. Different from the 4hr- or 24hr-Dehy conditions, various levels of FFA subtypes differed under the HT condition compared with the control (Fig. 6c, d). The levels of C18 and C16 FFA of B. minor increased significantly under NS conditions compared to the control (Fig. 6a). The NS condition promoted the accumulation of all C16-subtypes FFA, whereas for C18-subtypes FFA, only C18:0, C18:1 and C18:2 levels increased conspicuously (Fig. 6c, d). Under GD conditions, the C18 FFA content decreased significantly, whereas the C16 FFA level increased compared to the control (Fig. 6a). The increase in C16 FFA is related to the polyunsaturated C16:2 and C16:3 FFA subtypes (Fig. 6c). Consistent with the results of changes in FFA levels, the transcript abundance of almost all genes involved in the de novo FFA biosynthesis decreased significantly under GD conditions (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Data 16).

a Bar charts showing the total content of C18- and C16- FFA in B. minor under different conditions. b Bar charts showing the content of unsaturated fatty acids and saturated fatty acids in B. minor under different conditions. Pie charts illustrate relative distributions of unsaturated and saturated FAs of B. minor in the respective condition. c Bar charts showing the content of major C16- FFAs. The top right corner bar charts show the proportion of each type of C16- FFA under different conditions. d Bar charts show the contents of major C18- FFAs. The top right corner shows the proportion of each type of C18- FFA in different environments. The plots showed in a-d are using average value of three biological replicates, error bars represent standard error, letters (abc) and asterisks denote significant differences (t-test, P < 0.05, see exact P-value in Supplementary Data 17). e The heatmap on the right panel shows the transcripts abundance of each gene involved in the metabolic pathway of FFA (Five abundance categories 1–5 based on normalized count value, see Supplementary Information). Each condition has three biological replicates (R1, R2, R3). The significant difference (absolute log2[fold change] value > 1 and FDR adjusted P < 0.05) is indicated with an asterisk (see Supplementary Data 16). The pink and mediumaquamarine asterisks denote the significant increase and decrease of gene transcript abundance, respectively. The numerals behind the asterisks show the binned transcript abundance for four kinds of different conditions. The left panel shows the metabolic pathway of FFA biosynthesis and the desaturation pathway of C16- and C18- FFA. The triangles in pink, mediumaquamarine, and gray indicate significant increase, decrease, and no change of gene transcription, respectively. The circles in pink, mediu-maquamarine, and gray indicate significantly increased, decreased, and unchanged metabolites. For proteins encoded by multiple copies of genes, the changes in total transcripts of the genes were employed for determining the overall change according to gene transcript abundance (see details in Supplementary Information). Abbreviations are explained in Supplementary Data 18.

Notably, we found that changes in transcript abundance of many genes associated with the biosynthesis and desaturation of FFA were inconsistent with changes in total FFA contents and various saturated and unsaturated FFA levels (Fig. 6e; Supplementary Data 16 and 17). For instance, whereas almost all genes exhibited decreased transcript abundance, the levels of total FFA and various desaturated FFAs increased under 4hr-Dehy condition compared to the control. These discordances might be understood when the downstream Kennedy pathway and membrane lipid metabolism are analyzed together with the FFA biosynthetic pathway. In brief, under the 4hr-Dehy condition, most genes in the Kennedy and membrane lipid metabolism pathways showed a significant decrease in transcriptional abundance (Fig. 7a, c). In line with this, significant declines in total GL and total GP levels (including various GL and GP subclasses) were also observed. These results suggest that the 4hr-Dehy might repress the overall activity of upstream FFA biosynthesis as well as the downstream pathways of Kennedy and membrane lipids. With the decrease of the downstream accumulation of GL and GP contents, the demand for upstream raw material FFA from both Kennedy metabolism and membrane lipid metabolism also decreases accordingly, thereby reducing the conversion from FFA into the Acyl CoA pool (the lower transcriptional abundance of LACS also supports this hypothesis). Finally, this may lead to an accumulation of various saturated and unsaturated FFAs, although the majority of the FFA metabolic pathways are reduced in gene transcript abundance.

a Bar charts show the major content of each subtype of GL-type lipids, and b, GP-type lipids in B. minor under different environmental conditions. The plots showed in a, b are using average value of three biological replicates, error bars represent standard error, letters (abc, opq, xyz) and asterisks denote significant differences (t-test, P < 0.05, see exact P-value in Supplementary Data 17). c The heatmap at the right panel shows the transcript abundance of each gene involved in the Kennedy metabolic pathway. Each condition with three biological replicates (R1, R2, R3). The left panel shows the Kennedy metabolic pathway. The triangles in pink, mediumaquamarine, and gray indicate significant increase, decrease, and no change of gene transcript abundance, respectively. The circles in pink, mediumaquamarine, and gray indicate significantly increased, decreased, and unchanged metabolites. The significant difference (absolute log2[fold change] value > 1 and adjusted P < 0.05; n = 3) is indicated with an asterisk. For proteins encoded by multiple copies of genes, the changes in total transcripts of the genes were employed for determining the overall change according to gene transcript abundance. Five abundance categories 1–5 are based on normalized count values, see Supplementary Information for details. d Schematic model of the significant changes of genes and relevant metabolites of lipid metabolism under different conditions in B. minor. DC: Dehydration Control, 4 h: under dehydration for 4 h, 24 h: under dehydration for 24 h, Dehy Dehydration, NC Nitrogen Starvation Control, NS Nitrogen Starvation, HC High Temperature Control, HT High Temperature, GT Glucose-Light, GD Glucose-Dark. MG Monoacylglycerol, DAG Diacylglycerol, TAG Triacylglycerol, SQDG Sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol, L-/DGTS Lyso-/Diacylglyceryl trimethylhomoserine, GAIL Galactolipids (Monog-alactosyldiacylglycerol, MGDG; Digalactosyldiacylglycerol, GDGD), PG Phosphatidylglycerol, PI Phosphatidylinositol, LPA Lysophosphatidic acid, PC Phosphatidylcholine, PE Phosphatidylethanolamine. Abbreviated names are explained in Supplementary Data 18.

Interestingly, the total FFA and various saturated and unsaturated FFA levels decreased significantly under 24hr-Dehy condition, despite a significant increase in the transcript abundance of the ACC, SAD, and FAT genes in the FFA biosynthetic pathway. By analyzing the transcriptome and metabolome of the Kennedy and membrane lipid pathways, we found that the transcript abundance of most genes, as well as the content of various GL and GP lipid subclasses, significantly increased, compared to the control. We conclude that highly active GL and GP assemblies downstream might trigger the requirement for FFA upstream to allow a higher accumulation of GL and GP lipids. Therefore, while the transcript abundance of several key genes in the FFA biosynthesis pathway increased significantly under 24-hour Dehy conditions, the total FFA content and levels of various FFA subclasses showed a significant decline compared to the control.

Lipidomic analysis of the Kennedy pathway in B. minor under abiotic stresses

TAG is the dominant lipid among GL in many plants81. Diacylglycerol or GL-type membrane lipids (such as DGTS, galactolipids, and SQDG) rather than TAG, was the most abundant GL in B. minor (Fig. 7a). MG, DAG, and TAG belong to GL-type non-polar lipids, while GL-type membrane lipids are mostly polar lipids that are crucial components of various membranes and essential for maintaining membrane functions82,83,84,85. In addition, GP lipids, like PG, PI, PC, PE etc., are also important polar lipids in various cellular membranes86, and play important roles in maintaining the structural stability, integrity, and fluidity of membranes87,88. Many studies have confirmed that plants respond to abiotic stress by adjusting the conversion between non-polar and polar lipids, as well as the compositions of various types of membrane GL and GP lipids68,89. Combined with changes in the metabolome and transcriptome, we further investigated how B. minor changes its GL and GP metabolism in response to various environmental stresses (Fig. 7, Supplementary Data 16 and 17).

Dehydration

We observed the total levels of GL and GP both significantly decreased under 4hr-Dehy but increased under 24hr-Dehy compared with the control (Figs. 5d, 7a, b). Correspondingly, the transcript abundance of most genes related to the Kennedy and membrane lipid pathways decreased under the 4hr-Dehy condition but increased under the 24-Dehy condition compared with the control (Fig. 7c).

The main reason for the changed level of GL was the large variation in galactolipid (GAIL) contents (composed of MGDG and DGDG). For example, transcript abundance of MGD and DGD, two key genes involved in GAIL biosynthesis, showed a significant decrease under 4hr-Dehy and a significant increase under 24hr-Dehy compared with the control (Fig. 7d). Here, the changes in transcript abundance of these two genes at 4hr-Dehy and 24hr-Dehy were consistent with the changes in GAIL contents during these two periods (Supplementary Fig. 24). This suggests that the GAIL level in the chloroplast membranes of B. minor plays an important role in response to dehydration. GAIL are the most abundant lipids in chloroplast membranes, and they constitute the majority of total membrane lipids in plants90 and membranes are the main targets of dehydration, and there is growing evidence for the involvement of membrane GAIL lipids in plant adaptation to stress. For example, the drought-induced DGDG accumulated in extra-chloroplastic membranes of cowpeas contributed to its tolerance to arid environments91, and regulation of galactolipids remodeling improved maize drought adaptation92.

Despite a significant decline of the total level of GP lipids under 4hr-Dehy, we also noted that two GP subtypes of membrane lipids (PC and PI) remained at the same levels as the control (Fig. 7b). PC mainly exists in the extra-plastidic membranes of plant cells to maintain membrane integrity and functionality89,93, and exogenous PC treatment has been reported to alleviate drought stress maintaining the integrity of cell membranes94. By further examining the transcript abundance of genes involved in PC metabolism, we found that 4hr-Dehy caused decreased transcript levels of PDAT and PLD, which encode enzymes involved in the downstream metabolic conversion of PC to PA and TAG, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 24, Supplementary Data 16)95. Therefore, we hypothesize that B. minor accumulates a higher level of PC in the extra-plastidic membranes by repressing its downstream conversion, eventually improving the resistance of cell membranes to dehydration. Only a few reports exist about changes in PI of plants under dehydration. Increased levels of inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate (InsP3) facilitated drought tolerance in tomato96. This is in accordance with our result on the significant increase of the PI content under 24 hr DeHy compared to the control. PIs are lipid messengers that play essential roles in the regulation of a wide array of cellular processes97, stimulating signal transduction in B. minor in response to dehydration.

In addition, a correlation analysis of the transcriptome and proteome of B. minor under DeHy from 0 hr to 4 hr and 24 hr was performed (Supplementary Fig. 25). Our results showed that many lipid metabolism-related genes displayed corresponding changes in their transcript abundance and protein abundance, such as ACC, FADs, LACS from the Free fatty acid biosynthesis pathway, DGAT, GPAT, PAP, Lipase from the Kennedy pathway, and SQD, LPCAT, PGPS, and ETK from the membrane lipid metabolic pathway. The results of the proteome analyses may help to gain further insight into the regulation of lipid metabolism at the gene expression level rather than only at the transcriptional level. However, considering that the proteome analysis was only performed under dehydration conditions in this study, and in general, many proteins remained undetectable, we mainly focused on the stress responses on changes in gene transcript abundance.

Nitrogen starvation

The contents of two main GL-type non-polar lipids (DAG and TAG) exhibited a significant increase in B. minor under NS conditions (Fig. 7a), but we found that the contents of various GL-type polar lipids, such as SQDG, DGTS, and GAIL were significantly decreased compared with the controls. Besides, many GP-type polar lipids (PG, PI, PC, PE) also displayed significant down-regulation under NS conditions (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Fig. 24). In line with this, transcript abundance of genes related to GP-type polar lipid metabolism PGP, EPT, SQD, MGD and DGD were significantly decreased under NS stress compared with the control (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 24). These results might imply the conversion of polar membrane lipids into non-polar lipids.

Notably, the transcript abundances of many Lipase genes involved in TAG degradation were considerably lower under NS conditions, suggesting that the disassembly of GL-type non-polar lipids to release FFA was inhibited in B. minor under NS conditions. Combined with the multi-omics results of B. minor under NS, we conclude that NS caused a higher accumulation of FFA, associated with 1) reduction in the activity of the downstream Kennedy and membrane lipid pathways (supported by decreased transcript abundance of most of the genes involved, compared to controls), thereby reducing the consumption of FFAs required for downstream GL and GP assembly. 2) the elevated transcript abundance of the FAT gene, a key enzyme in FFA biosynthesis, and its increased transcript level might positively promote FFA biosynthesis. Overall, both the metabolic pathways from non-polar lipids to polar lipids and from non-polar lipids to FFA were suppressed under NS (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 24).

High-temperature

Despite remarkable drops in TAG and MG contents in B. minor, the SQDG level, one of the most abundant lipids present in the thylakoid membranes98,99, increased nearly five-fold in B. minor compared with the control (Fig. 7a). SQDG is important to maintain the full functionality of the photosystems, and its depletion interferes with the plants’ photosynthesis100. Our findings underpin a previous study suggesting the involvement of SQDG in heat tolerance101. HT likely promoted the conversion of DAG to SQDG in B. minor with concomitant inhibition of the conversion from DAG to TAG. Although the contents of two GL-type polar lipids (MGDG and DGDG) that are abundant in thylakoid membranes exhibited no changes under HT (Supplementary Data 17), the contents of all GP-type polar lipids that are widely distributed in cellular membranes including thylakoid membranes102, such as PG, PI, PC, and PE increased significantly in B. minor under HT stress compared with the control (Fig. 7b). Being consistent with the changes of metabolites, the transcript abundance of many genes involved in membrane lipid metabolisms such as LPAT, PLD, EPT, PDAT, MGD, DGD, and MPIS, also significantly increased under HT(Fig. 7d).

Given HT generally damages the fluidity of membrane lipids and interferes with the activity of chloroplast-based enzymes and membrane integrity in plants103,104,105, we inferred, based on our results, that HT might promote the conversion of non-polar lipids (DAG and CDP-DAG) to polar membrane lipids (SQDG and other GP-type lipids) in B. minor to cope with HT. Contrasting results were obtained in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, in which plastid membrane lipids (especially MGDG) were degraded and converted to storage lipids (DAG and TAG) upon exposure to HT (40 min at 42 °C)106. Similar results were reported at moderate HT (28 °C) in Scenedesmus obliquus, a prominent constituent of the temperate freshwater phytoplankton, in which a decrease in polar lipids and a concomitant increase in TAG was observed with potentially important implications concerning food quality for higher trophic levels during climate change107. The difference in lipid dynamics could be related to the adaptation of the terrestrial B. minor to its specific high-temperature habitat.

Heterotrophic condition

The total GL content was significantly higher in B. minor under the GD condition, which mainly resulted from a significant increase in TAG accumulation (Fig. 7a). In line with this, the increased transcript abundance of LPAT and PAP genes in the Kennedy pathway is proposed to be a major factor that correlated with TAG accumulation. It is worth noting the contents of several GL-type polar lipids (SQDG and MGDG) decreased significantly compared with the control (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Figs. 23, 24). Similarly, we found the contents of many GP-type polar lipids such as PG, PI, PC and PE also decreased significantly (Fig. 7b). These results indicated that metabolic conversion from the non-polar DAG to polar membrane lipids was repressed in B. minor under the GD condition. To a certain extent, the metabolic changes of B. minor under the GD condition were similar to those under the NS condition. Accumulation of TAG in the dark under heterotrophic conditions in B. minor might be an adaptation to its terrestrial life history as has also been observed in C. reinhardtii, another terrestrial alga, under anaerobiosis in the dark108.

A comparison of responses of lipid metabolism in B. minor to the different environmental conditions tested, using multi-omics (Fig. 7d), revealed similarities between the NS and GD conditions with higher levels of GL, in particular TAG (also DAG in the NS condition) and lower levels of SQDG and MGDG as well as all GP. Besides, C16 FFA also exhibited an increased level under both conditions. In general, these results are in accordance with previous data and highlight the effect of general stress conditions on the lipid metabolism of microalgae. However, the lipid metabolism of B. minor under the HT condition differs from a general stress response (and from data reported in the literature, see above) in that GL, in particular, TAG as well as C16 and C18 FFA are reduced under HT (Fig. 7d). Therefore, we suggest that the specifics of lipid metabolism under HT reflect an adaptation of B. minor to its high-temperature habitat. The biocrust-dwelling alga B. minor exhibited opposite changes in response to short-term and long-term Dehy. During 4hr-Dehy metabolic activity of lipid metabolism of B. minor is reduced, as both the transcript abundance of lipid-related genes and the total lipid content (especially polar membrane lipids) decreased dramatically. It should be noted that both the total non-polar lipids and FFAs increased compared with the control. Lipid metabolism activity fully recovered after 24hr-Dehy, accompanied by increased transcript abundance of most lipid metabolism genes compared with the control. Besides, lipid production was stimulated and resulted in higher accumulation of both polar and non-polar lipids.

Our results elucidate several major drivers of genome evolution in Bracteacoccus that presumably contributed to the ability of the algae to adapt to biocrusts with poly-extreme conditions. These drivers include HGT from bacteria, fungi, and other organisms, gains and expansions of stress-related gene families, neofunctionalization of genes following gene duplications, and genome structural variations. We also summarized the changes in lipid metabolite levels, compositions, and transcript abundance of genes of lipid metabolism in response to various stresses in B. minor. These changes are especially important for balancing the conversion of polar membrane lipids and non-polar storage lipids to cope with various environmental stresses. As a result of the evolutionary innovations in lipid metabolism, Bracteacoccus has developed strong adaptive properties for its special microhabitat, which may account for its wide distribution in the world’s biocrusts.

Methods

Cultivation of algae, nucleic acid extraction

Axenic strains of B. bullatus (SAG 2032) and B. minor (SAG 221-1) were obtained from the Culture Collection of Algae at Göttingen University (SAG; https://www.uni-goettingen.de/en/culture+collection+of+algae + %28sag%29/184982.html). The strain SAG 221-1 was isolated by R.Chodat in 1913 from soil (presumably in Switzerland) and is the authentic strain of the species. The strain SAG 2032 was isolated from the soil of a mining dump, contaminated with heavy metals, near the Harz mountains (Germany) by U.G. Schlösser before 1999. It is also the authentic strain of the species. Algae were grown in 3N-BBM + V culture medium (https://www.ccap.ac.uk/index.php/media-recipes/) in aerated 1 L culture flasks in a 14/10 hr light/dark cycle at 18 µmol photons m−2 s−1 (white LED illumination) and 20 °C. During all steps of culture scale-up until nucleic acid extraction, axenicity was monitored by sterility tests and light microscopy. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (B. bullatus: 10 min, 300 g; B. minor: 8 min, 400 g), rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and transferred to -80 °C until freeze-drying. To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms of stress-induced and photo-/heterotrophic lipid accumulation in the Bracteacoccaceae, we performed transcriptome profiling of B. minor cultured under; 1) dehydration (4hr-Dehy and 24hr-Dehy); 2) nitrogen starvation (NS, 3 weeks), 3) high temperature (HT, 1 hr), 4) mixotrophic Glucose-Light (GL, 3 weeks) and heterotrophic Glucose-Dark (GD, 3 weeks) conditions (here GL served as the control for GD) (see “Experimental setup for stress treatments” of Methods for details).

For 10X sequencing, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA was isolated from the freeze-dried algae using the IrysPrep® Plant Tissue DNA Isolation kit (RE-014-05; Bionano Genomics, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality and quantity were evaluated using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and a Qubit® 3.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA extractions were performed from freeze-dried material using RNA-easyTM Isolation Reagent (Vazyme, Nanjing).

Light microscopy

Cultures were grown for light microscopy at 20 °C, light/dark cycle of 14:10 h, 50 µmol photons m-² s-1, on agar slants of ESP-Medium (Basal Medium with Peptone, Medium 1b in Schlösser 1994). Light microscopy was performed on three-week-old cultures using an Olympus BX-60 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), a ProgRes C14plus camera, and the ProgRes CapturePro imaging system (v2.9.0.1) (Jenoptik, Jena, Germany). A minimum of n = 20 micrographs were taken for each species.

Library preparation, sequencing and genome assembly

Stranded RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the TrueSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina). Libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq. 10X Genomics Chromium™ genome libraries with insert sizes of 350–500 bp were prepared with Chromium Genome Reagent Kit (v2 Chemistry, Pleasanton, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocols with modified PCR primers to introduce sequencing primers suitable for the BGISEQ-500 platform and then sequenced with PE reads of 150 bp.

FASTQC (version 0.11.8) and SOAP-nuke (version 1.5.2) were used to perform the quality control, trim the adapter, and low-quality read filtering109. Jellyfish (version 2.3.0) was used to perform Kmer analysis for estimation of genome size, heterozygosity and repetitive contents110. The ploidyNGS was used to visualize and explore ploidy (https://github.com/diriano/ploidyNGS). The clean 10X reads were assembled into contigs and scaffolds using Supernova (version 2.1.1) with the default parameters111. The quality of genome assembly was evaluated by Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCOs version 3.0)112. BLAT (version 36) and Bowtie2 (version 2.5.1) were used to map RNA and DNA reads to genome assembly to calculate the mapping rate, respectively. To further enhance assembly contiguity, Hi-C data was used to perform chromosome conformation in conjunction with the 3D-DNA algorithm113. Finally, using Juicebox the scaffolds were anchored onto 19 chromosomes of B. bullatus and B. minor, respectively114.

Repeat annotation and gene annotation

A combination of a de-novo and homolog-based strategy was used to perform annotation of repetitive elements (RE). For de-novo prediction, LTRharvest115 and MITE-hunter116 were used to identify retrotransposons and transposons, respectively. RepeatModeler (version 1.0.3) was applied to annotate other types of Res117. For the library-based approach, the custom library Repbase 25.03 was used to identify the repeat elements by RepeatMasker118. Highly accurate gene prediction was performed by using BRAKER with “–etpmode” mode, which integrates two major tools: GeneMark-ES/ET and AUGUSTUS119. Gene functional annotation was performed using BLASTP (E-value < 1 × 10–5) against the KEGG, InterProScan, COG, SwissProt, TrEMBL, and NR databases.

Gene family analysis and phylogenetic reconstruction

Genomes of 19 representative algae were downloaded from public databases (Supplementary Data 19). A total of 262 single-copy orthologous were identified by OrthoFinder (version 2.4.0)120. Multiple sequence alignments of orthologs were performed by MAFFT (version 7.310) followed by a gap position filter (only positions where 50% or more of the sequences showed a gap were treated as a gap position)121. A maximum-likelihood tree was constructed by RAxML (version 8.2.4) with the GTR (General time reversible) + Gamma model, with 500 bootstrap replicates122. The iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/itol.cgi) software was used for visualization of the final phylogenetic tree, and the Count software to calculate dynamic changes in the gene families such as expansions, contractions, gains and losses for each evolutionary node, based on the phylogenetic tree123. MCMCTREE (v4.5) implemented in PAML package was used to estimate the divergence time of the phylogenetic tree124. The Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) process was run for 5,000,000 iterations with a sampling frequency of 500 after a burn-in of 500,000 iterations. The time point, the divergence time of Volvocales (516.7-682.8 Mya), was chosen as the calibrator according to TimeTree (http://www.timetree.org/).

Experimental setup for stress treatments

For differential analyses of transcriptomes, B. minor was grown under different cultivation conditions. In brief, 800 mL of a well-grown culture of B. minor (cell density ~107 cells/mL) was concentrated by centrifugation (8 min, 400 g) to 60 mL. 5 mL of the concentrated suspension were applied to an agar plate (9 cm diameter). In total 18 agar plates (1% [w/w] agar) were inoculated. Algae were grown on the agar plates for three weeks as follows: a control was grown on 3 N BBM + V agar at regular cultivation conditions (see above for suspension cultures). For nitrogen limitation (NS) 0.1 N BBM + V was used. To test for heterotrophy, 0.5% (w/w) glucose in 3 N BBM + V was applied and plates were exposed either to regular cultivation conditions (GL) as a control or stored in the dark (GD). In addition, we also recorded the dry weight and chlorophyll content of B. minor cells under GD and GL conditions (Supplementary Fig. 26). Total chlorophyll content was determined using a TECAN plate reader (Infinite M Plex) following previously established protocols and equations125,126. To test for the effect of dehydration (Dhy), a well-grown culture of B. minor (cell density ~107 cells/mL) was centrifuged as above. Aliquots of the pellet (packed cell volume) were transferred with a spatula to weighing pans and placed in a glass desiccator (Glaswerk Wertheim, Germany), loaded with activated silica gel drying beads. The water content of the algal fresh weight (packed cell volume) was determined to be 81.9% (n = 6) after freeze-drying. Samples were withdrawn from the desiccator after 4 hrs and 24 hrs, respectively. Three biological replicates were analyzed, and each included transcriptome, lipidome and proteome analyses (details of the proteome analyses are described in Supplementary Information). The water contents of the samples were determined to be 4.6 g water/g dry weight (n = 5) at the beginning of the experiment (time 0), 2.2 g water/g dry weight after 4hrs and 0.04 g water/g dry weight (n = 5) after 24 hrs. The relative humidity (RH) within the desiccator was also measured by a digital thermo-hygrometer (Temeo, Bresser, Rhede, Germany). The RH was 10% at the start of the experiment, increased to 24% after 4hrs and decreased again to 10% after 24 hrs. A drying curve of the 5 replicates is shown in Supplementary Fig. 27. To test for the effect of high temperature (HT), 125 mL of a concentrated algal suspension was transferred to a petri dish (145 cm diameter) and incubated for 1 h at 40 °C in the dark (controls were kept in the dark at 20 °C). Algae from the HT experiment were concentrated by centrifugation as above. Immediately after harvest (from agar plates or after centrifugation) the cells were frozen in liquid N2 and further processed as described above for suspension cultures. Light microscopical analyses of treated cells was routinely performed but no significant changes were observed in morphology or color compared to controls after the experimental period.

Transcriptome analysis

RNA data were trimmed using Trimmomatic (version 0.3.2)127. Bowtie2 was used to map RNA reads against the annotated gene set of B. minor. Transcript abundance was quantified as a normalized count using eXpress128. The differential gene transcript abundance was identified by using DESeq2129 (|log2FoldChange | >1 and adjust P < 0.05). Five abundance categories (1–5) are based on normalized count values. For proteins encoded by multiple copies of genes, the changes in total transcripts of the isogenies were employed for determining the overall pattern according to gene transcript abundance, see Supplementary Information for details.

Detection of key candidate functional genes

The candidate gene sequences should generally be similar to the query genes collected from previous studies or databases (BLAST < 1E-05); and the function of the candidate genes should be consistent with the query genes according to online NR functional annotation or Swissprot functional annotation. For TFs we used the HMMER search method. We downloaded the HMMER model of the domain structure of each transcription factor from the Pfam website (https://pfam.xfam.org/) while referring to the TAPscan v.3.0 transcription factor database130. Preliminary candidates were collected by searching the profile HMM for each species ( < 1E-05), then those genes were filtered that did not match the SwissProt functional annotation ( < 1E-05). Finally, genes containing a wrong domain according to the domain rules of the TAPscan v.3.0 transcription factor database were filtered. In expanded gene families the gene copy number was >1.5-fold in the Bracteococcaceae compared to the average of all other Sphaeropleales genomes analyzed.

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of candidate horizontal gene transfer (HGT) genes

Firstly, we performed BLASTP searches against gene sets of B. bullatus and B. minor to each taxonomy group (including Metazoa, Archaea, Bacteria, Fungi, Virus, and Archaeplastida) from NR database. The HGT gene identification was performed by blast2hgt pipeline53, it determines HGT candidates and its donor based on the BLAST searching results for each taxonomy group of the NR database, to calculate the HGT index (h) and the alien index (AI), and finally evaluates whether HGT events have occurred and the likelihood of transfers. We set the putative recipient was Chlorophyta, and the putative donor groups were bacteria, fungi, archaea, viruses, and metazoans. All the identified HGT candidates were further clustered as gene families using Orthofinder. To further ensure the accuracy of the identified HGT-acquired gene families, phylogenetic analysis for each gene family was performed. Additionally, we checked the upstream and downstream regions of each HGT gene, all of which are clearly homologous to Viridiplantae, and identified that most HGT-acquired gene families were supported by transcript evidence. Multiple sequence alignments were generated by MAFFT (version 7.310). IQ-TREE (version 1.6.12) using the automatically selected best-fit model was applied to construct the maximum likelihood trees.

SNP, Indel and structural variation analysis between B. bullatus and B. minor

MCscan was used to detect syntenic blocks between B. bullatus and B. minor with default parameters131. Circos and RectChr (version 1.32) were used for data visualization132. The MUMmer4 tool (version 4.0.0) was applied to compare the chromosomal regions of the two algae using the “–mum” parameter133. The delta-filter utility was used to filter and obtain the one-to-one unique alignment blocks. SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) and indels were detected by using show-snp. The structural variants (SV) were carried out by the show-diff utility in MUMmer4, and the potential PAV regions were selected from classified differences (gaps, duplication, insertion). The snpEff software was used to annotate the effects of SNPs/InDels and PAV to genes. A gene with > 80% overlap with PAV regions was treated as a PAV-related gene134.

Statistical analysis

The metabolite significance tests of the NS, HT, and GD group and their respective control groups were performed using the T-test (two-tailed) in this study, and the metabolite significance test of dehydration of 4 and 24 h compared to the control group was performed by one-way ANOVA, multiple comparisons were using Student–Newman–Keuls (SNK). (Supplementary Data 17).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation / Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA: CRA020561) that are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa. The genome assemblies, annotation and raw data for two Bracteacoccaceae, B. bullatus and B. minor in this study are also deposited at the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (https://db.cngb.org/search/project/CNP0002578/). The protein and lipid detection data were deposited in the OMIX database (OMIX007958, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix/release/OMIX007958). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Prăvălie, R. Drylands extent and environmental issues. A global approach. Earth-Sci. Rev. 161, 259–278 (2016).

Belnap J., Büdel B., Lange O. L. Biological Soil Crusts: Characteristics and Distribution. In: Biological Soil Crusts: Structure, Function, and Management (eds Belnap J., Lange O. L.). Springer (2003).

Belnap J., Weber B., Büdel B. Biological Soil Crusts as an Organizing Principle in Drylands. In: Biological Soil Crusts: An Organizing Principle in Drylands (eds Weber B., Büdel B., Belnap J.). Springer International Publishing (2016).

Ferrenberg, S., Reed, S. C. & Belnap, J. Climate change and physical disturbance cause similar community shifts in biological soil crusts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 12116–12121 (2015).

Chock, T. et al. Responses of biological soil crusts to rehabilitation strategies. J. Arid Environ. 163, 77–85 (2019).

Antoninka, A. et al. Biological soil crusts in ecological restoration: emerging research and perspectives. Restor. Ecol. 28, S3–S8 (2020).

Torres-León C., Aguirre-Joya J. A., Aguillón-Gutierrez D. R. Dryland Microorganisms: Ecology and Biotechnological Potential. In: Microbial Biodiversity, Biotechnology and Ecosystem Sustainability (eds Aguilar C. N., Abdulhameed S., Rodriguez-Herrera R., Sugathan S.). Springer Nature (2023).

Fuíková, K., Flechtner, V. R. & Lewis, L. A. Revision of the genus Bracteacoccus Tereg (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) based on a phylogenetic approach. Nova Hedwigia, 15-59 (2012).

Kol, E. & Flint, E. A. Algae in green ice from the Balleny Islands, Antarctica. N. Z. J. Bot. 6, 249–261 (1968).

Kastovská, K., Elster, J., Stibal, M. & Santrůcková, H. Microbial assemblages in soil microbial succession after glacial retreat in Svalbard (high arctic). Microb. Ecol. 50, 396–407 (2005).

Stibal, M., Šabacká, M. & Kaštovská, K. Microbial communities on glacier surfaces in svalbard: impact of physical and chemical properties on abundance and structure of cyanobacteria and algae. Microb. Ecol. 52, 644–654 (2006).

Darcy, J. L. & Schmidt, S. K. Nutrient limitation of microbial phototrophs on a debris-covered glacier. Soil Biol. Biochem. 95, 156–163 (2016).

Broady, P. A. Diversity, distribution and dispersal of Antarctic terrestrial algae. Biodivers. Conserv. 5, 1307–1335 (1996).

Sosa-Quintero, J. et al. Biocrusts in Mexican deserts and semideserts: A review of their species composition, ecology, and ecosystem function. J. Arid Environ. 199, 104712 (2022).

Rybalka, N. et al. Unrecognized diversity and distribution of soil algae from Maritime Antarctica (Fildes Peninsula, King George Island). Front Microbiol 14, 1118747 (2023).

Czerwik-Marcinkowska, J. & Mrozińska, T. Algae and cyanobacteria in caves of the Polish Jura. Polish Botanical J. 56 (2011).

Lee, N. et al. Caves and Karst Environments. In: Life at Extremes: Environments, Organisms and Strategies for Survival) (2012).

De Luca, D., Caputo, P., Perfetto, T. & Cennamo, P. Characterisation of environmental biofilms colonising wall paintings of the Fornelle Cave in the archaeological site of Cales. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 8048 (2021).

Kunsbaeva, D. et al. Preliminary data about algae and cyanobacteria of volcanic soils on Kuril Islands. Theoretical and Applied Ecology, 10.25750/1995-4301-2018-4-119-126 (2018).

Allaguvatova, R. Z., Nikulin, A. Y., Nikulin, V. Y., Bagmet, V. B. & Gaysina, L. A. Study of biodiversity of algae and cyanobacteria of Mutnovsky and Gorely Volcanoes soils (Kamchatka Peninsula) using a polyphasic approach. Diversity 14, 375 (2022).

Mikhailyuk, T., Glaser, K., Tsarenko, P., Demchenko, E. & Karsten, U. Composition of biological soil crusts from sand dunes of the Baltic Sea coast in the context of an integrative approach to the taxonomy of microalgae and cyanobacteria. Eur. J. Phycol. 54, 263–290 (2019).

Kammann, S. et al. Successional development of the phototrophic community in biological soil crusts on coastal and inland dunes. Biology 12, 58 (2023).

Evdokimova, G., Mozgova, N. P. & Shtina É. Soil pollution by fluorine and evaluation of the soil microflora status in the area of influence of an aluminum plant. Eurasian Soil Science, (1997).

Patova, E. & Dorokhova, M. Green algae in tundra soils affected by coal mine pollutions. Biologia 63, 831–835 (2008).

Sommer, V., Karsten, U. & Glaser, K. Halophilic algal communities in biological soil crusts isolated from potash tailings pile areas. Front. Ecol. Evolution 8, 46 (2020).

Maltseva, I. & Maltsev, Y. Diversity of cyanobacteria and algae in dependence to forest-forming tree species and properties rocks of dump. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 18, 545–560 (2021).

Maltsev, Y., Maltseva, S. & Maltseva, I. Diversity of cyanobacteria and algae during primary succession in iron ore tailing dumps. Microb. Ecol. 83, 408–423 (2022).

Malik, S. et al. Characterization of a newly isolated self-flocculating microalga Bracteacoccus pseudominor BERC09 and its evaluation as a candidate for a multiproduct algal biorefinery. Chemosphere 304, 135346 (2022).

Ratha, S. K. et al. Exploring nutritional modes of cultivation for enhancing lipid accumulation in microalgae. J. Basic Microbiol. 53, 440–450 (2013).

Minyuk, G., Chelebieva, E. & Chubchikova, I. Secondary carotenogenesis of the green microalga Bracteacoccus minor (Chodat) Petrova (Chlorophyta) in a two-stage culture. Int. J. Algae 16, 354–368 (2014).

Piligaev, A. V. et al. Isolation of prospective microalgal strains with high saturated fatty acid content for biofuel production. Algal Res. 12, 368–376 (2015).

Mamaeva, A. et al. Simultaneous increase in cellular content and volumetric concentration of lipids in Bracteacoccus bullatus cultivated at reduced nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations. J. Appl. Phycol. 30, 2237–2246 (2018).

Maltsev, Y. I., Maltseva, I. A., Maltseva, S. Y. & Kulikovskiy, M. S. Biotechnological potential of a new strain of Bracteacoccus bullatus (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyta) as a promising producer of omega−6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Russian J. Plant Physiol. 67, 185–193 (2020).

Lukavský, J. et al. The alga Bracteacoccus bullatus (Chlorophyceae) isolated from snow, as a source of oil comprising essential unsaturated fatty acids and carotenoids. J. Appl. Phycol., 1-12 (2023).

Lang, I., Hodac, L., Friedl, T. & Feussner, I. Fatty acid profiles and their distribution patterns in microalgae: a comprehensive analysis of more than 2000 strains from the SAG culture collection. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 124 (2011).

Parker, B. C., Bold, H. C. & Deason, T. R. Facultative heterotrophy in some chlorococcacean algae. Sci. (N. Y., NY) 133, 761–763 (1961).

Sheath, R. G. & Hellebust, J. A. Glucose transport systems and growth characteristics of Bracteacoccus minor. J. Phycol. 10, 34–41 (1974).

Chekanov, K., Litvinov, D., Fedorenko, T., Chivkunova, O. & Lobakova, E. Combined production of astaxanthin and β-carotene in a new strain of the microalga Bracteacoccus aggregatus BM5/15 (IPPAS C-2045) cultivated in photobioreactor. Biology 10, 643 (2021).

Chekanov, K., Shibzukhova, K., Lobakova, E. & Solovchenko, A. Differential responses to UV-A stress recorded in carotenogenic microalgae Haematococcus rubicundus, Bracteacoccus aggregatus, and Deasonia sp. Plants 11, 1431 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Chromosome‐level genome of Pedinomonas minor (Chlorophyta) unveils adaptations to abiotic stress in a rapidly fluctuating environment. N. Phytologist 235, 1409–1425 (2022).

Fučíková, K. et al. Johansenicoccus eremophilus gen. et sp. nov., a novel evolutionary lineage in Chlorophyceae with unusual genomic features. Plant Ecol. Evol. 156, 311–325 (2023).

Lee, C. et al. Complete plastome of Coelastrum microporum Nageli (Scenedesmaceae, Sphaeropleales). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 8, 948–951 (2023).

Tatusov, R. L., Koonin, E. V. & Lipman, D. J. A genomic perspective on protein families. Sci. (N. Y., NY) 278, 631–637 (1997).

Saenz, L., Santamaría, J. M., Villanueva, M. A., Loyola-Vargas, V. M. & Oropeza, C. Changes in the alkaloid content of plants of Catharanthus roseus L. (Don). as a result of water stress and treatment with abscisic acid. J. Plant Physiol. 142, 244–247 (1993).

Seigler, D. S. Pyrrolidine, Tropane, Piperidine, and Polyketide Alkaloids. In: Plant Secondary Metabolism (ed Seigler D. S.). Springer US (1998).

Ali, A. H., Abdelrahman, M. & El-Sayed M. A. Alkaloid role in plant defense response to growth and stress. In: Bioactive Molecules in Plant Defense: Signaling in Growth and Stress (eds Jogaiah S., Abdelrahman M.). Springer International Publishing (2019).

Isah, T. Stress and defense responses in plant secondary metabolites production. Biol. Res. 52, 39 (2019).

Robles, P. & Quesada, V. Research progress in the molecular functions of plant mTERF proteins. Cells 10, 205 (2021).

Qi, H., Xia, F.-N., Xiao, S. & Li, J. TRAF proteins as key regulators of plant development and stress responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 64, 431–448 (2022).

Ivanauskaite, A. et al. Loss of chloroplast GNAT acetyltransferases results in distinct metabolic phenotypes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 64, 549–563 (2023).

Laxa, M., Liebthal, M., Telman, W., Chibani, K. & Dietz, K.-J. The role of the plant antioxidant system in drought tolerance. Antioxidants 8, 94 (2019).

Dumanović, J., Nepovimova, E., Natić, M., Kuča, K. & Jaćević, V. The significance of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense system in plants: A concise overview. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 552969 (2020).

Ma, J. et al. Major episodes of horizontal gene transfer drove the evolution of land plants. Mol. Plant 15, 857–871 (2022).

Cantarel, B. L. et al. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 37, D233–D238 (2009).

Ito, S. et al. Enzymatic properties of cellobiose 2-epimerase from Ruminococcus albus and the synthesis of rare oligosaccharides by the enzyme. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 79, 433–441 (2008).

Stolz, J. & Munro, S. The cComponents of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mMannosyltransferase cComplex M-Pol I hHave dDistinct fFunctions in mMannan sSynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44801–44808 (2002).

Kitagaki, H., Wu, H., Shimoi, H. & Ito, K. Two homologous genes, DCW1 (YKL046c) and DFG5, are essential for cell growth and encode glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane proteins required for cell wall biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol 46, 1011–1022 (2002).