Abstract

Pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs) are one of the most common intracranial tumors with diverse clinical manifestations. Current pathological classification systems rely primarily on histological hormone staining and transcription factors (TFs) expression. While effective in identifying three major lineages, molecular characteristics based on hormones and TFs lack sufficient resolution to fully capture the complex tumor heterogeneity. Transcriptional diversity by alternative splicing (AS) offered additional insight to address this challenge. Here, we perform bulk and full-length single-cell RNA sequencing to comprehensively investigate AS dysregulation across all PitNET lineages. We reveal pervasive splicing dysregulations that better depict tumor heterogeneity. Additionally, we delineate fundamental splicing heterogeneity at single-cell resolution, confirming bulk findings and refining splicing dysregulation varying among tumor cell types. Notably, we effectively distinguish the silent corticotroph subtype and define a distinct TPIT lineage subtype, which is associated with worse clinical outcomes and increased splicing abnormalities driven by altered ESRP1 expression. In conclusion, our results characterize the subtype specific AS landscape in PitNETs, enhancing the understanding of the PitNETs subtyping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

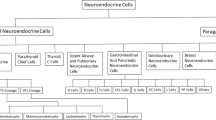

The pituitary is the most critical endocrine gland in humans, regulating key physiological functions by hormone secretion. Pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs, also known as pituitary adenomas) are among the most prevalent intracranial tumors originating from the anterior pituitary gland (APG)1. The pathological classification of PitNETs incorporates the expression of specific hormone genes and three lineage-specific transcription factors (TFs), including PIT1 (POU1F1), TPIT (TBX19), and SF1 (NR5A1)2. While the tumors within the same lineage have identical TF expressions, they exhibit variations in cellular functions and tumorigenesis. The PIT1 lineage commonly exhibits excessive hormone secretion, including somatotroph tumors (secreting growth hormone, GH), lactotrophs tumors (secreting prolactin, PRL) and thyrotroph tumors (secreting thyroid-stimulating hormone, TSH). Mixed somatotroph-lactotroph tumors secret GH and PRL (PG) and plurihormonal PIT1 lineage tumors secret all three hormones (PIT1M). The TPIT lineage tumors contain only one type, namely corticotroph tumors (secreting adrenocorticotrophic hormone, ACTH) and SF1 lineage contain gonadotroph tumors (GO, secreting follicle-stimulating hormone, FSH, and luteinizing hormone, LH)3. Null cell tumors (NULL) lack hormone production or specific TF expression, whereas plurihormonal tumors express multiple hormones with two or more lineages2. But even the same subtypes also exhibit diverse clinical manifestations. For instance, functional corticotroph tumors demonstrate typical Cushing symptoms because of ACTH oversecreting, while silent corticotroph tumors (with ACTH expressing but without Cushing symptoms) demonstrate more aggressive clinical behavior compared to other subtypes4. The complex hormone secretion profiles and highly variable clinical outcomes of these tumors present both requirements and challenges for more precise subtype classification. However, to date, the pathogenesis of most subtypes remains poorly understood and genomic markers for characterization are still lacking.

Previous studies have predominantly focused on exploring genetic features or overall gene expression for additional molecular features of PitNETs1, overlooking co-transcriptional regulations. Alternative splicing (AS) is an essential cellular process in eukaryotes that generates multiple transcripts, diversifying final protein products5. Beyond PitNETs, AS has been extensively studied in various human tumors6, offering invaluable resources for a better understanding of inter-tumor heterogeneity and developing new therapies7. However, the overall landscape of splicing changes in PitNETs has not been thoroughly investigated so far.

Here, we characterize the alternative splicing landscape of PitNETs using the PitNETs cohort with transcriptome sequencing, including bulk (n = 268 patients) and full-length single-cell RNA-seq (n = 195,720 cells) datasets from tumor tissues. Our analysis spans almost all PitNET subtypes, allowing us to construct subtype-specific splicing patterns and corresponding regulatory networks of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs). In contrast to the expression of TFs, our analysis more faithfully captures the transcriptomic diversity of PitNETs, thereby better demonstrating inter-tumor heterogeneity. Notably, within the TPIT lineage, we identify a distinct splicing regulatory pattern with significant clinical relevance. These findings are robustly validated by an independent cohort of 180 pituitary tumors. Overall, our study offers an enhanced approach to PitNET classification.

Results

PitNETs exhibit extensive splicing diversity

To obtain the global alternative splicing landscape of PitNETs, we performed bulk RNA sequencing of 264 PitNET patients and 4 normal samples, along with full-length single-cell RNA sequencing of 1,95,720 cells from 14 patients and 2 normal samples (Fig. 1a). In addition, we collected an independent bulk RNA-seq dataset from 180 PitNET patients as a validation cohort8. Patient distribution in the bulk discovery cohort encompassed all clinicopathological subtypes, including the three TF lineages, Mix, NULL, and 4 normal samples. Tumor samples were further divided into 10 clinicopathologic subtypes, including GH (n = 47), PG (n = 16), PRL (n = 26), TSH (n = 6), PIT1M (n = 8), ACTH (n = 58), GO (n = 91), Mix (n = 9) and NULL (n = 3) (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). Three major lineages of PitNETs can be effectively classified by the expression of lineage-specific TFs2. Principal component analysis (PCA) based on the expression of these TFs and related hormone genes, or global gene expression, revealed three distinct groups corresponding to the three major lineages (Supplementary Fig. 1b, 2 and Supplementary Data 2). However, within each lineage, the individual subtypes could not be clearly distinguished (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2b). For instance, within the PIT1 lineage, samples from the GH, PRL, and TSH subtypes are intermixed and indistinguishable, whether classified based on TF expression or global gene expression (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2b). This suggested that the extensive heterogeneity surpassed the capacity of expression-based markers to accurately categorize more specific subtypes. In addition, we found that subtype-specific hormone genes are also commonly high-expressed in subsets of patients across most subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). Overall, the TF-based, as well as global gene expression-based classification showed a modest agreement with the clinicopathological classification in both PIT1 lineage (adjusted rand index, ARI = 0.28 and 0.31) and TPIT lineage (ARI = 0.35 and 0.36) (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2c). Moreover, PitNETs express a relatively small number of genes compared to 33 other cancer types from TCGA (Supplementary Fig. 1e)9. These findings underscore the limitations of relying solely on gene expression to characterize PitNET subtypes.

a Overview of the splicing analysis in PitNETs. b PCA analysis of the TFs and related hormone gene expression from 264 PitNETs and 4 normal samples. Each node indicates each sample and node color indicates the classification based on clinicopathological lineages (left) and subtypes (right). c Dendrograms show the consistency of TF-based clustering and pathological classification in the PIT1 (left) and TPIT (right) lineages. Unsupervised clustering was performed based on the expression of lineage-specific TFs and related hormone genes. Subtype was assigned to each cluster by the most prevalent pathological subtype of each individual. Consistency was assessed by the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI). d Distribution of the four types of alternative splicing events identified in PitNETs, including skipped exon (SE), alternative 3′ splice site (A3), alternative 5′ splice site (A5), and retained intron (RI). e Scatter plot showing the frequency of splicing events per gene, sorted from highest to lowest. Genes with more than 30 splicing events (orange color) are used for functional enrichment analysis. The P-values are calculated by the one-sided hypergeometric test. f Scatter plot displaying the number of splicing events for each gene (x-axis) along with the overall expression levels (y-axis). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Compared to overall gene expression, splicing isoforms are not only more abundant in terms of quantity but also encompass valuable transcript structural information. Moreover, splicing-derived functional diversity has been demonstrated to impact various cancer-associated processes10, indicating the potential power of integrating AS for a more accurate subtype classification. Alternative splicing analysis in PitNETs was performed by rMATS, which detected a total number of 1,43,601 alternative splicing events, primarily enriched in exon skipping events (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Data 3). Approximately 88% of spliced genes (n = 13,641) have more than one splicing event (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Data 3), and the number of events was independent of the target gene expression (Fig. 1f). In line with previous studies11,12,13,14, functional annotation of the genes with the most splicing variants (≥30) indicated enrichment in the pathways such as ‘GTPase regulator activity’, ‘Protein metabolic process’, ‘Nitrogen compound transport’, ‘Cell junction’ and ‘Developmental process’ (Fig. 1e). Collectively, these findings suggest that, beyond gene expression, PitNETs exhibit a broader range of complex splicing repertoire with potential function implications.

Splicing dysregulations faithfully recapitulate tumor heterogeneity of PitNETs

To investigate the power of splicing profiles for subtype classification, a differential splicing analysis was performed on the bulk RNA sequencing data from 264 PitNET patients and 4 normal samples. A total of 198 differential splicing events were identified across seven subtypes spanning three tumor lineages, based on comparisons of each subtype against all other subtypes (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P-value < 0.001) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 4). Then we performed a global subtype-specific differential gene expression analysis using the same strategy as for differential splicing analysis, 340 differentially expressed genes were identified (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P-value < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Both global gene expression and splicing features effectively captured the three major lineages. However, gene expression features showed limited ability to differentiate subtypes within these lineages, while splicing features demonstrated superior performance, particularly in distinguishing more challenging subtypes (Supplementary Figs. 2c, d and 3a). This implies that alternative splicing provides unique information to the transcriptomic diversity of PitNET subtypes, independent of gene expression levels. Consistent with previous clinical observations8, the majority of samples from the PIT1 lineage subtypes both expressed and secreted hormones (93/103, 90%) (Supplementary Data 1). In the SF1 lineage subtypes, all samples expressed hormones, but none secreted them (91/91, 100%) (Supplementary Data 1). Most samples in the TPIT lineage subtypes expressed but did not secrete hormones (49/58, 84%) (Supplementary Data 1), and significant differences in splicing patterns were observed among them. Three samples were clinically diagnosed as NULL subtypes with negative IHC results for all hormones. However, our analysis showed that the NULL subtype exhibited similar splicing characteristics to the silent TPIT lineage patients (Fig. 2a), suggesting a potential origin of the NULL subtype. Additionally, our results support the use of a specific panel of splicing events for the diagnosis of the PG (mixed PRL and GH) subtype of PitNETs (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 4). Furthermore, the PG subtype shared more common splicing events with the GH subtype in comparison to the PRL subtype. These observations have implications for better understanding the initiation and development of PG and NULL subtypes. TF-based gene expression lacked the specificity to delineate these subgroups, whereas splicing precisely captured their distinct characteristics. These results were further validated in another independent PitNETs cohort (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). We observed highly consistent PSI (Percentage Spliced In) changes of the shared 166 splicing events between the discovery cohort and the validation cohort (Supplementary Fig. 3e). Unlike our discovery cohort, the splicing characteristics of the NULL subtype here were similar to those of the SF1 lineage, which suggested potential heterogeneity within the NULL subtype. Again, this validation cohort also confirmed that the splicing pattern of the NULL subtype was similar to those of the non-secreting silent subtype.

a Heatmaps showing the subtype-specific splicing characterization. The color shows the z-score of the Percent-Spliced-In (PSI) value of the splicing events across the samples. The clinical characteristics data include lineage, clinicopathological subtype, secretion, age, gender, invasion status, tumor size, and Ki67, which are shown in different colors. b Heatmap showing the differentially expressed RBP genes across different subtypes in PitNETs. The color shows the z-score of the expression value of RBPs across the samples. c Correlation network between RBP expressions and PSI values of differential splicing events. The top 15 RBPs with the largest number of splice targets from each lineage were selected (red nodes). Colors for AS nodes indicate the different lineage-specific events: PIT1 (in yellow), TPIT (in green), and SF1 (in blue). d RT-PCR validation of subtype-specific splicing events in patients. Selected GH-specific splicing events are shown on NCAM1 and DENND1A; PRL-specific splicing events: EPB41L1 and ITGB3BP; TSH-specific splicing events: AKAP8L and NFE2L1; GO-specific splicing events: APP and MCF2L; ACTH-specific splicing event: ENAH and ARFGAP2; ACTH-silent-specific splicing events: VTI1A and ARFGAP1. For the two-group comparisons, each experiment was independently repeated three times, while for the three-group comparisons, each group included two biological replicates. Different colors represent the PIT1 (in yellow), TPIT (in green), and SF1 (in blue) lineages, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Increasing evidence has highlighted the critical regulatory role of RBP dysfunction in splicing across various human diseases15. Therefore, we further investigated the expression changes of 1350 known RBPs15 in PitNETs. We identified 185 differentially expressed RBPs across all subtypes (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P-value < 0.001) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Data 5). We also observed highly consistent expression changes of the shared 151 RBPs between the discovery cohort and the validation cohort (Supplementary Fig. 3f). Notably, an almost identical pattern was observed between splicing disorder and RBP dysregulation (Fig. 2a, b), and a strong correlation was also confirmed in the validation cohort (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). This strong consistency in each subtype suggested a close relationship between splicing and RBP activity. We identified the top 15 RBPs from each lineage that govern each specific splicing pattern and generated a tightly connected regulatory network between RBPs and alternative splicing events (ASEs) based on correlation analysis (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Data 6). To further validate these regulatory relationships, we analyzed RNA-seq data from 17 RBP knockdown, knocked out, or overexpression studies. In 82% of the datasets, at least half of the AS events matched the predicted regulatory patterns (Supplementary Data 6). Importantly, we experimentally validated some subtype-specific splicing events in primary patient samples, such as NCAM1, DENND1A and FBXO25 for the GH subtype, EPB41L1 and ITGB3BP for the PRL subtype, AKAP8L and NFE2L1 for the TSH subtype, APP and MCF2L for the GO subtype, ENAH and ARFGAP2 for the functional ACTH subtype, VTI1A, ARFGAP1 and LSR for the silent ACTH subtype (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3g). In conclusion, our study clarifies the heterogeneity of PitNET subtypes using splicing features, which cannot be obtained by TF-based characteristics alone. Furthermore, we uncover RBP regulatory networks governing these splicing disorders.

scRNA-seq confirmed the subtype-specific splicing landscape

AS events detected from bulk RNA-seq represent mixed signals averaged over cell subpopulations, offering limited power to delineate the fundamental splicing heterogeneity. In contrast, single-cell analysis enables more precise identification of tumor cell populations for each subtype, facilitating the discovery of splicing changes and dysregulations within each pure cluster of different tumor cell types as well as normal cells. Recent advancements in full-length capture techniques have significantly improved read coverage across entire transcripts, showing advantages in the detection of AS and isoform usage at the single-cell level16. To further validate the precise splicing map of PitNETs at single-cell resolution, we employed full-length single-cell RNA sequencing on cells from 16 fresh samples, including GH (n = 3), PG (n = 1), PRL (n = 2), TSH (n = 2), ACTH (n = 3), GO (n = 2), NULL (n = 1) and normal pituitary samples (n = 2) (Supplementary Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 7). After quality controls, a total number of 195,720 cells were retained for subsequent analysis. (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Based on the expression of marker genes (Supplementary Fig. 4c), 13 major cell clusters were identified by unsupervised clustering, including cycling cells (CC), endothelial cells (EC), macrophage cells (Macro), T lymphocyte cells (T cell), B lymphocyte cells (B cell), fibroblasts (Fibro), PIT1 lineage normal cells (PIT1-N), somatotropes (GH), lactotropes (PRL), thyrotropes (TSH), functional corticotropes (ACTH), silent corticotropes (ACTHsilent) and gonadotropes (GO) (Fig. 3a). As positive controls, lineage-specific TF genes were exclusively expressed in three clusters of PitNET cells separately, indicting the main three PitNET lineages (Fig. 3b). Normal cells from different samples were consistently clustered together, suggesting no obvious batch effects (Supplementary Figs. 4d and 5a). At the same time, our findings showed that each tumor cell cluster predominantly derived from patients of the corresponding subtype, indicating the PitNETs heterogeneity (Supplementary Figs. 4e and 5b, c). The subtype-specific differentially expressed genes and enriched molecular pathways are consistent with observations from previous studies14,17,18,19 (Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Data 8). Collectively, our results indicate that the identified cellular subpopulations at the single-cell level effectively characterize their respective subgroups.

a UMAP plots show the 13 single-cell clusters of 195,720 cells from 16 samples. Dots: single cells. Cell type is color-coded. b Scatter plots showing the expression of known subtype markers, including key TFs and hormone genes. Light to dark colors indicate increasing expression levels. c Differential gene expression analysis shows upregulated (in red) and downregulated (in blue) genes from each single-cell cluster. d Functional annotation enrichment analysis of differentially spliced genes in each subtype. The enrichment fold changes are displayed for each term. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further inferred CNVs to identify tumor cells of each subgroup for splicing analysis (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Next, we aim to check whether the subtype-specific AS landscape observed in bulk tissues could also be reproduced at the single-cell cluster level. To this end, we revisited the identified splicing events from bulk tissues and only selected the events that also could be detected in the single-cell splicing analysis. Then, we calculated the PSI values for this set of splicing events in each cell population of PitNETs. Strikingly, the same splicing pattern was replicated between single-cell clusters, with a perfect matching of inter-tumor subtypes, indicating the high exclusivity of AS changes within each heterogeneous tumor clone (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Data 4). Significant splicing changes were observed across various AS types, with cassette exon events being the most common alterations, including changes on NCAM1, ITGB3BP, KHDRBS1, ENAH, ARFGAP1 and MCF2L (Fig. 4b). Similar to the observation at the bulk level, the analysis of RBP expression on single-cell clusters also revealed a matched pattern to AS changes (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Data 5). Notably, most splicing events (117/198, 59%) and RBPs expression (108/185, 58%) exhibited increased differentiation between subtypes at the single-cell level than the bulk level (Fig. 4a, c). This indicates that AS captures the fundamental transcriptomic diversity present in heterogeneous cell clones, while signals on bulk tissue may result from a mixture of cell types. For the remaining ASEs, 73% (59/81) were not captured due to the low read depth in single-cell data (Supplementary Data 9).

a Sankey diagram showing the changes in differential splicing events from bulk to scRNA-seq data. Heatmap showing the 117 splicing characterizations in the pseudo-bulk from scRNA-seq. b Read coverage showing the inclusion of splicing events on single-cell clusters. c Sankey diagram showing the changes in differentially expressed RBPs from bulk to scRNA-seq data. Heatmap showing the 108 dysregulated RBPs. d Ternary plot of the relative percentage of splicing events based on their presentations in PIT1 patients. The PSI of each splicing event is normalized across all subgroups. Each splicing event (node) has three coordinates indicating that a% is the normalized PSI detected in GH clusters, b% is the normalized PSI detected in PRL clusters, and c% is the normalized PSI detected in TSH clusters. And a + b + c = 100. e UMAP plots showing cells from the PIT1 lineage. f, g UMAP plots showing cells from the PIT1 lineage with detected reads for the NCAM1 event (f) and the NFE2L1 event (g). h Ternary plot of the relative percentage of splicing events based on their presentations in TPIT and SF1 patients. i UMAP plots showing cells from the TPIT lineage. j, k UMAP plots showing cells from the TPIT lineage with detected reads for the ENAH event (j) and the ARFGAP1 event (k). l Venn diagram showing the overlap between differential splicing events verified by pseudo-bulk and single-cell level. P-values are calculated by a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. m Differentially spliced events verified by pseudo-bulk in subtypes are ranked by the P-values. P-values are calculated by a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. n Box plot showing the APP splicing events in the cells of all tumor clusters (n = 46,051). Different colors represent different subtypes. The boxes indicate median (center), Q25, and Q75 (bounds of box), the smallest value within 1.5 times interquartile range below Q25 and the largest value within 1.5 times interquartile range above Q75 (whiskers). P-values are calculated by a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we further explored the subtype-specific events that have been validated at the single-cell level. Within the PIT1 lineage, we further subdivided 38 ASEs that tend to be more commonly present in the GH subtype, 15 ASEs in the PRL subtype, and 10 ASEs in the TSH subtype (Fig. 4d). The top splicing event in the GH subtype is the exon inclusion of Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 (NCAM1) gene. In 3836 cells where this event was detectable (with junction reads >5), NCAM1 displayed an increased inclusion level of the ninth exon in the GH subtype (Fig. 4e, f). Previous studies have associated NCAM1 in PitNETs with growth hormone secretion regulation20. We knocked down the aberrant exon in primary cells from GH subtype patients and found that excessive secretion of growth hormone was significantly suppressed. When overexpressing both long and short transcripts, only the overexpression of the long aberrant transcript promoted GH secretion, while the normal short transcript did not. This suggests that altered NCAM1 splicing may be linked to the pathogenesis of the GH subtype (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Similar functional changes were observed in another abnormal exon inclusion of DENND1A (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). NFE2 Like BZIP Transcription Factor 1 (NFE2L1) is implicated in invasive pituitary tumors and thyroid cell proliferation21,22. Interestingly, NFE2L1 also showed a significant splicing usage of a cassette exon in the TSH subtype (Fig. 4e, g). Likewise, in TPIT and SF1 lineages, we found that 12 ASEs of the ACTH subtype, 21 ASEs of the silent ACTH subtype, and 15 ASEs of the GO subtype were differentially spliced (Fig. 4h). The frequently reported ENAH event, which impacts invasion23, is significantly associated with functional ACTH cell cluster (Fig. 4i, j). The ADP Ribosylation Factor GTPase Activating Protein 1 (ARFGAP1) gene is known to be required for GTP hydrolysis24. We observed increased splicing of ARFGAP1 in the silent ACTH subtype from the TPIT lineage (Fig. 4i, k). The aberrant long transcript of ARFGAP1-L significantly promoted the EMT process in silent ACTH patients, whereas the normal transcript did not lead to notable changes (Supplementary Fig. 6e). Lastly, we summarized a reliable list of such AS events that demonstrate significant exclusive usage in one subtype versus all others. Ultimately, 45 high-confident splicing events covering all tumor subtypes were confirmed (Fig. 4l, m and Supplementary Data 4). The top splicing event involved the APP gene and was mostly enriched in the GO subtype (Fig. 4m, n). We observed that knocking down the aberrant splicing event of the APP gene reduced EMT progression, suggesting decreased invasiveness (Supplementary Fig. 6f). Importantly, these target genes harboring subtype-specific splicing events did not exhibit differential gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 7a–h). This suggests that changes in transcript structure account for the subtype-specific diversity, while the overall gene expression is unable to capture this. In conclusion, we deciphered the fundamental intra-tumor heterogeneity by splicing alternations at single-cell resolution, confirming the findings at the bulk level, and refining splicing dysregulations across diverse tumor cell clones.

ESRP1 is the key regulator of splicing diversity in shaping TPIT heterogeneity

Tumors in the TPIT lineage of PitNETs are typically caused by ACTH-hypersecreting corticotrophs, leading to metabolic disorders and associated complications. While a more aggressive subtype of ACTH-silent has been identified, the differences in molecular pathogenesis between the two subtypes are still poorly understood. We next sought to explore the regulatory mechanisms of the subtype-specific splicing events within the TPIT lineage. We listed the top ten RBPs with the most significant expression differences in the TPIT lineage (Fig. 5a). ESRP1, MDN1, and TCF20 were previously identified in the regulatory network constructed by bulk RNA-seq data (Fig. 2c). ESRP1 is a crucial protein known for its role in regulating CD44 splicing switch during the EMT23, a process linked to tumor metastasis and therapy resistance in pituitary tumors25. Notably, we observed a significant increase of ESRP1 expression in ACTH-secreting cells compared to non-functional cells (Fig. 5b). Surprisingly, ESRP1 binding motifs were found in 82% (27/33) of TPIT lineage-associated splicing events, most of which have got more than one binding motif (Fig. 5c). This indicates a collective regulatory role of ESRP1 on splicing events of TPIT lineage. By conducting ESRP1 knockdown and overexpression experiments using primary PitNET cells, we validated 85% (45/53) genes with associated splicing events occurring in at least one experimental dataset (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Data 10). TPIT lineage-associated splicing events, including exon skipping in ARFGAP2 and ENAH, and exon inclusion in ARFGAP1, showed significant correlations with ESRP1 expression (Fig. 5e–g). These correlations were consistently observed in our entire discovery cohort of pituitary tumors as well as the validation cohort (Supplementary Fig. 8a–f). Moreover, we confirmed differences in ESRP1 expression in functional and silent ACTH patients by qPCR (Fig. 5h) and validated its regulatory role in TPIT lineage-specific splicing events by knocking down and overexpressing ESRP1 in primary cells derived from TPIT patients (Fig. 5i and Supplementary Fig. 8g–i). Further, in the PIT1 lineage, we identified the top 10 RBPs with the most significant expression differences (Supplementary Fig. 8j). STAU1 and RBMX were also detected in our previous regulatory network (Fig. 2c). Staufen homolog 1 (STAU1) is a highly conserved double-strand RNA-binding protein known to regulate widely alternative splicing in adipocyte differentiation26. Our results suggested that STAU1 may serve as a key regulator of PIT1 lineage-specific splicing events, showing a high correlation with the PKP4 and OGA splicing events, validated in both patient cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 8k–n). In conclusion, we clarified the regulatory relationship between RBPs and splicing and confirmed the pivotal role of ESRP1 in regulating TPIT lineage-specific splicing events.

a Bubble heatmap showing the top 10 dysregulated RBPs in the TPIT lineage. b UMAP plots (left) showing cells from TPIT lineage. The colors represent different subtypes. The scatter plot (right) shows the expression of ESRP1 between the silent and functional ACTH clusters. c Heatmap displaying the number of detected ESRP1 motifs in each TPIT-lineage-specific splicing event validated by single-cell RNA-seq analysis. The ESRP1 motif (upper) is collected from the database (RBPmap, http://rbpmap.technion.ac.il/). The top enriched motif calculated from the differentially spliced events is displayed in the lower panel. d Venn diagram showing the overlap between events differentially spliced after ESRP1 knockdown and overexpression (RNA-seq data) in primary cells from PitNET patients. The P-values are calculated by the one-sided hypergeometric test. e–g Scatter plots showing the expression of ESRP1 (y-axis) versus the PSI of ARFGAP2 (x-axis) (e), ENAH (x-axis) (f), and ARFGAP1 (x-axis) (g) in 58 patients of TPIT lineage. The colors represent different subtypes. The P-values are calculated by a two-sided Spearman’s correlation analysis. h qRT-PCR showing the relative mRNA expression of ESRP1 normalized to GAPDH in patients from the functional (n = 5) and silent ACTH subtypes (n = 6). The P-values are calculated by a two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean values ± SD. i RT-PCR validation of the effect of ESRP1 knockdown on the TPIT lineage-specific splicing events in primary TPIT patient samples. Changes in splicing events under the condition of two ESRP1 siRNA treatments are measured by RT-PCR using gene-specific primers (sequences listed in Supplementary Data S14). Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent replicates. The P-values are calculated by a two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Clinical implications of TPIT lineage-specific splicing events

Finally, we want to investigate the clinical relevance of splicing characteristics in the TPIT lineage. To this end, we gathered pertinent patient clinical data, encompassing disease progression, invasion status, tumor size, and Ki67 values, which are all recognized indicators of PitNET aggressiveness (Supplementary Data 11)14,17. Dysregulation of ESRP1 has been linked to poor survival outcomes across various cancers such as breast cancer27 and prostate cancer28. Patients with lower ESRP1 expression in the silent TPIT lineage demonstrated worse progression-free survival (PFS) (Fig. 6a). Multivariable Cox regression analysis of ESRP1 expression alongside clinical covariates further identified ESRP1 expression as the most significant risk factor for patient PFS (Supplementary Data 12). ESRP1-regulated splicing events also exhibited a marked impact on PFS (Fig. 6b–d). These subtype-specific events are associated with increased invasion (Fig. 6e), larger tumor size (Fig. 6f), and higher Ki67 (Fig. 6g), respectively. These findings emphasize the important clinical significance of subtype-specific splicing characteristics as biomarkers for disease progression. To assess the power of splicing features in guiding PitNET classification, four TPIT lineage-specific splicing events including ARFGAP2, ENAH, ARFGAP1, and VTI1A were selected for unsupervised clustering. These events were selected by overlapping the top 10 differential AS changes in both bulk and single-cell analyses and targeted by ESRP1 from experimental validations (Fig. 5i). The ARI value derived from the splicing features is 0.8, which is more than twice the accuracy (0.35) calculated based on the expression of TFs and related hormone genes (Fig. 6h). Interestingly, we further defined two subgroups within the silent ACTH group based on splicing characteristics, defined as high PSI and low PSI groups (Fig. 6h). The high PSI group showed worse PFS (Fig. 6i), and a higher risk of relapse (Supplementary Fig. 9a). In addition, we found a lower stromal, immune and estimate scores in the high PSI group using the ESTIMATE algorithm (Fig. 6j, Supplementary Fig. 9b and Supplementary Data 13). Reduced infiltration of stromal cells and immune cells has been reported to be associated with worse outcomes in breast cancer, ovarian cancer, sarcoma, melanoma, and lymphoma treatment29. This is consistent with the adverse prognosis observed in the high PSI group (Fig. 6i). It suggests that a reduction in infiltration may be a critical contributor to the progression of the ACTH subtype. Further immune infiltration analysis revealed significant differences in the populations of resting mast cells, gamma delta T cells, and resting memory CD4+ T cells between the two groups. (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Together, we have defined a subset of the silent ACTH patients characterized by increased splicing abnormality, and this subset of aggressive tumors is significantly associated with dismal prognosis.

a–d Kaplan–Meier PFS curves for 36 patients from silent TPIT lineage stratified by the expression of ESRP1 (a), PSI of ARFGAP2 (b), PSI of RAD23A (c) and PSI of ARFGAP1 (d). PSI values of events here are normalized relative to the silent ACTH subtype. The P-values are calculated by the log-rank test. e–g The bar plot shows the proportion of invasion status (e), the difference in max tumor size (f), and the Ki67 value (g) between two groups with high and low PSI of ARFGAP2, LTA4H, SNAP25, PACRGL, and ADCY4 in TPIT lineage patients, respectively. The P-values are calculated by a two-sided Fisher’s exact test. h Dendrogram representing the consistency among TF-based clustering, AS-based (splicing) clustering, and pathological classification between the functional and silent ACTH subtypes. Samples with similar splicing profiles are defined into three main clusters. Consistency is assessed by the ARI. i Kaplan–Meier PFS curves for 34 patients in the silent ACTH subtype stratified by the High and Low PSI group identified in Fig. 6h. The P-values are calculated by the log-rank test. j Box plot showing the stromal and immune score in the High (n = 29) and Low PSI group (n = 17). The boxes indicate median (center), Q25, and Q75 (bounds of box), the smallest value within 1.5 times interquartile range below Q25 and the largest value within 1.5 times interquartile range above Q75 (whiskers). The P-values are calculated by a two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. k Heatmaps showing the different pathways enriched in the functional and silent ACTH including the High and Low PSI group. l Pre-ranked GSEA analysis showing the top 500 upregulated and downregulated targets in the functional ACTH subtype tested against a pre-ranked gene list which is generated based on the expression changes in the silent ACTH subtype of low PSI. NES normalized enrichment score. The P-values are calculated by a two-sided permutation test. m Diagram of the classification in the TPIT lineage based on splicing characteristics. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To explore the biological functions underlying the heterogeneity mediated by splicing in silent ACTH, we conducted differential pathway and expression analysis. The results revealed similar pathway activities between the low PSI group and the functional ACTH (Fig. 6k). Both the functional ACTH and the low PSI group showed a strong consistency in their transcriptional programs, with both upregulated and downregulated genes showing high similarity (Fig. 6l). Moreover, we found that the low PSI group had higher POMC expression, which is a marker gene for functional ACTH than the high PSI group (Supplementary Fig. 9d). All of these results suggested that the low PSI group of the silent ACTH shared similar molecular characteristics with the functional ACTH, which typically has a better clinical outcome. In summary, subtype-specific splicing features not only distinguish silent subtypes from functional ACTH but also stratify the silent subtype into a high PSI group associated with the worst clinical prognosis in the TPIT lineage (Fig. 6m). This insight underscores the potential of utilizing splicing profiles to refine the classification of pituitary subtypes.

Discussion

PitNETs exhibit high heterogeneity, presenting diverse clinical manifestations and comprising various hormone-secreting cell types. However, current pathological classification systems heavily rely on TFs and hormone expression, which makes it difficult to comprehensively capture the extensive heterogeneity of PitNETs. Since the third edition of the WHO classification in 2017 abandoned Ki67, p53, and other biomarkers as diagnostic markers for atypical pituitary adenomas, there have been no recognized biomarkers that can reflect the biological behavior of pituitary tumors. Thus, defining precise molecular features for direct subtyping helps clinicopathological classification, improving treatment accuracy and efficacy.

Previous studies have reported genetic features such as GNAS mutations in the GH subtype and USP8 mutations in the ACTH subtype30. Nevertheless, around 60% of tumors lack recurrent somatic mutations31. Copy number alterations are also detected in PitNETs, yet their role in tumorigenesis remains unclear32. Transcriptome analyses have revealed distinct gene expression signatures in GH and ACTH subtypes32. Recent studies have also proposed the analysis of the proteome and epigenome of PitNETs14. However, the importance of co-transcriptional regulation in biological processes has not been emphasized in PitNETs. Previously, we identified a critical splicing factor SF3B1 as the one most commonly mutated gene in the PRL subtype33, indicating the potential role of alternative splicing in promoting tumorigenesis of pituitary tumors. However, the full splicing landscape of PitNETs remains unexplored in current research.

To explore the transcriptomic splicing features of PitNETs, we collected 264 tumor samples spanning almost all subtypes, along with 4 normal samples from APG. In this study, we delineated the spectrum of alternative splicing in PitNETs which was validated by an independent cohort of 180 pituitary tumors. Additionally, we gathered full-length single-cell sequencing data from various subtypes to further characterize subtype-specific splicing features at single-cell resolution. Tumors lacking evidence of lineage differentiation are classified as the NULL cell subtype. Despite its rarity, this subtype has attracted attention due to its aggressive behavior and high recurrence rate34. The origin of this subtype remains unclear. Through analysis of two bulk RNA-seq datasets, we found similar splicing patterns between the NULL subtype, silent ACTH, and GO subtypes separately. This still suggests an unclear origin for the NULL subtype but indicates a close relationship with the silent tumors. Maybe it originates from the dedifferentiation of different lineage tumor cells. In addition, we observed a higher proportion of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in single-cell data from a patient with a NULL subtype. CAFs have been reported to modulate cancer metastasis, growth factor production, and angiogenesis35, indicating a potential malignant cell origin for this subtype. However, the role of CAFs in pituitary tumors is not fully understood and further exploration is needed to clarify their impact on the NULL subtype.

RBPs are pivotal regulators of alternative splicing and interact with RNA to form ribonucleoprotein complexes. The expression of RBPs provides further insight into the characterization of splicing features in PitNETs. We constructed subtype-specific splicing regulatory networks within each lineage, revealing widespread dysregulation of RBPs, indirectly confirming the splicing disruptions in PitNETs. However, the underlying reasons for such dramatic changes in RBP expression remain unknown. Possible explanations may include activation of particular transcriptomic programs or altered epigenetic regulations which require investigations in future studies. Notably, utilizing splicing features enabled the effective identification of the silent ACTH subtype within the TPIT lineage, a subtype challenging to distinguish in the current pathological classification. We identified the ESRP1 gene as a regulator of TPIT lineage-specific splicing events. ESRP1, a key epithelial splicing regulatory factor, extensively participates in the EMT process, highlighting its strong association with disease progression in pituitary tumors. It is worth the effort to further investigate the oncogenic role of ESRP1 by regulating key mis-splicing defects that contribute to the carcinogenesis of corticotroph tumors. ESRP1 dysregulation is enriched in samples with worse PFS in the TPIT lineage. Importantly, we observed a correlation between ESRP1 expression and preoperative ACTH levels (Supplementary Fig. 9e), indicating that measuring ESRP1 levels could provide additional guidance for treatment selection.

Furthermore, within the silent ACTH subtype, we observed significant differences in splicing patterns between the two identified subgroups. The first subgroup, characterized by lower levels of splicing alterations, showed similarities to functional ACTH in terms of biological characteristics and clinical outcomes, indicating a potential transitional state between functional and silent ACTH. As consistent with previous literature reports, functional ACTH and silent tumors can transform into each other36,37. Conversely, the second subgroup, displaying higher levels of splicing alterations, exhibited poorer clinical outcomes with higher recurrence rates, suggesting a more aggressive tumor phenotype. These findings underscore the need for further exploration into the underlying mechanisms of tumorigenesis in these distinct subgroups, which may provide additional avenues for personalized treatment strategies.

Although our study provided valuable insights into the alternative splicing landscape of PitNETs, there are a few limitations. While our cohort size is substantial, being exclusively sourced from the Chinese population may limit the generalizability of our findings to people of different ethnic groups. Additionally, due to the technical limitations of single-cell sequencing, we cannot capture comprehensive splicing information for every individual cell. To address this, we are actively engaged in developing new methodologies for single-cell splicing discovery. Lastly, although we have experimentally validated the functional consequences of some splicing events, further investigation is needed to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

This study not only lays a theoretical foundation for the classification and diagnosis of PitNETs but also suggests directions for optimizing clinical treatment strategies and prognostic predictions. Especially for subgroups that are difficult to distinguish, such as silent ACTH tumors, more precise diagnostics and treatment recommendations can be provided through splicing features. Overall, our study advances our understanding of PitNETs biology, emphasizing the significant role of splicing in shaping PitNET heterogeneity. Integrating these splicing features could guide molecular classification and treatment strategy for distinct PitNET subtypes, improving clinical outcomes.

Methods

Study subjects

A total of 284 human pituitary tissue samples collected from Beijing Tiantan Hospital were included in this study. All patients provided written informed consent for the molecular characterization of their tumor samples and for follow-up on their clinical information and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital. No compensation was provided to the participants in this study. All 284 samples are Asian individuals, including 156 males and 128 females. The sex and/or gender of participants were determined based on self-report. The age of the PitNETs dataset ranges from 8 to 77 years (female: 17–77; male: 8–75), with a mean age of 47.02 (SD 13.33). Two cohorts of patients were recruited: one for bulk RNA-seq (264 PitNETs and 4 normal samples) and the other for full-length single‑cell RNA-seq analysis (14 PitNETs and 2 normal samples). All patients underwent surgical resection at Beijing Tiantan Hospital. The cohort of 264 PitNETs underwent surgery from 2018 to 2022, whereas the 14 PitNETs cohort were collected in 2023. Normal pituitary tissues were collected from healthy donors. Information on the samples is provided in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 7.

Cell line and culture of primary PitNET tumor cells

Human PitNET tumor specimens were acquired during surgical resections and promptly immersed in freshly prepared low-glucose DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The collected tumor tissues were meticulously dissected into finer fragments using a pipette tip, followed by a filtration step to remove larger tissue fragments and debris. The resulting cell suspension was then subjected to red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer treatment to eradicate erythrocytes. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was extensively washed and resuspended in a fresh culture medium and subsequently cultured for further experimental analysis. Hormone release from isolated growth hormone-secreting tumor cells was assessed 48 h post-transfection using the AuthentiKine™ Human Growth Hormone ELISA Kit (KE00221, Proteintech), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The GH3 (CCL-82.1) rat pituitary cell line was acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The cells were cultured in Ham’s F12K medium supplemented with 2.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 15% horse bovine serum (Gibco).

Protein extraction and Western blotting

Proteins were extracted using NCM Biotech’s RIPA buffer, separated on 8–10% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Primary antibodies against E-cadherin (1:20,000, Proteintech), Vimentin (1:1000, Abcam), and GAPDH (1:6000, Abcam) were used for target protein detection. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence.

RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR

The experimental procedures used for RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR were described in our previous publication33. RT-PCR was conducted utilizing the I-5 High-Fidelity Master Mix (MCLAB, San Francisco, USA), and the PCR products were electrophoresed on 1–3% agarose gels. Quantitative RT-PCR was processed on QuantStudio 3 and 5 platforms (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Details of the primers used are provided in Supplementary Data 14.

Transfection and RNA interference

Beijing Syngentech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) synthesized the small interfering (si) RNA duplexes; siRNA sequences of human ESRP1 are listed in Supplementary Data 14. The ESRP1 overexpression plasmid was constructed by GeneChem (Shanghai, China). Transfections were executed with Lipo 3000 (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Cells were transfected with siRNA for 48–72 h and were harvested to perform subsequent experiments. siRNA and overexpression plasmids for gene isoform-specific knockdown and overexpression were synthesized by Umine Biotechnology Co., LTD (Guangzhou, China) (Supplementary Data 14).

Bulk RNA-seq

For RNA sequencing library preparation, 1–3 µg of total RNA per sample was processed using the VAHTS Universal V6 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit for Illumina, involving mRNA enrichment, fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, and purification. The library was then prepared through end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, size selection, and PCR amplification. Library quality was evaluated by measuring RNA concentration with a Qubit® RNA Assay Kit, assessing insert size via an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system, and quantifying the effective library concentration using a Bio-RAD CFX 96 fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument. Qualified libraries were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina platform using a PE150 strategy to obtain 150-bp paired-end reads, ensuring a comprehensive transcriptome analysis.

Preprocessing of bulk RNA-seq data

FastQC (v0.11.8) with default parameters was applied to calculate the read quality for all samples. All samples have passed quality control. FASTQ sequences were aligned to the human hg38 reference genome (GENCODE, GRCh38.99) using STAR (v2.7.7a) software38 with default parameters.

Gene expression analysis of bulk RNA-seq data

To generate the mRNA expression matrix for transcriptome analysis, FeatureCounts (v2.0.1)39 from the Subread package was used to assign reads to genes and genic regions. Read counts were then transformed to RPKM values, followed by log2 transformation and quantile normalization at the sample level. Student’s t-test was used to test for differential gene expression between sample groups. Dysregulated RBPs were considered to be significant if they passed the P-value threshold of 0.001. Genes expressed in at least 70% of patients (read count >30) were selected for subtype-specific expression analysis. Genes with zero expression in more than 10% of patients were excluded. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed to compare the expression of each subtype against all other subtypes. Significant genes were defined by a fold change greater than two (|log2FC| > 1) and a P-value < 0.001. Genes showing significant differences in multiple subtypes were excluded. The same strategy was applied to an independent PitNETs cohort for the same analysis, and differentially expressed genes had to be validated in both cohorts (Except for the PG subtype with no samples and the TSH subtype with only 2 samples).

Alternative splicing analysis of bulk RNA-seq data

rMATS (v4.0.2)40 was used to perform differential alternative splicing (AS) analysis for four major types (SE, A5SS, A3SS, IR). Splicing events that were detected in at least 70% of the patients (max read >30) were retained to calculate the number of events in PitNETs. For subtype-specific splicing analysis, we further excluded events with a PSI value of 0 in more than 10% of patients. We conducted Wilcoxon rank-sum tests comparing the PSI values of each subtype against all other subtypes. Significant events were defined as those with a splicing ratio difference of more than twice (|log2FC| > 1) between subtypes, and the P-value less than 0.001. Splicing events showing significant differences in multiple subtypes were excluded. Transcriptome-wide splicing analysis was performed using the same strategy in the independent PitNETs cohort. Differentially spliced events had been validated in both cohorts (Except for the PG subtype with no samples and the TSH subtype with only 2 samples). The splicing analysis of RNA-seq datasets from the ESRP1 knockdown and overexpression PitNET cell lines was performed by the same strategy.

Principal component analysis

PCA was applied to the bulk RNA-seq data of 264 PitNET samples and 4 normal pituitary samples to inspect the gene expression difference between each lineage or subtype samples by using the prcomp function in R (v4.2.3).

Pan-cancer analysis

We download the raw gene count data of Pan-cancer from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database by R package TCGAbiolinks (v2.27.2)41. For each cancer type, we calculated the number of expressed genes per patient.

Regulatory network construction

Regulatory networks were constructed for RBPs and splicing events in each of the three lineages. Differentially expressed RBPs were considered as potential regulatory factors in the network, and differential splicing events were considered as potential regulated targets. We established the relationship between RBPs and splicing events using Spearman’s correlation test, considering |Cor| > 0.35 and P-value < 1e-10 as significant. The regulatory network was visualized using Cytoscape software (v3.9.0)42.

Full-length single‑cell preparations and RNA-seq

After harvested, tissues were washed in ice-cold RPMI1640 and dissociated using the Brain Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi 130-095-942) as instructed. DNase I (Sigma 9003-98-9) treatment was optional according to the viscosity of the homogenate. Cell count and viability were estimated using a fluorescence Cell Analyzer (Countstar® Rigel S2) with AO/PI reagent after the removal of erythrocytes (Solarbio R1010) and then debris and dead cells removal was decided to be performed or not (Miltenyi 130-109-398/130-090-101). Finally, fresh cells were washed twice in the RPMI1640 and then resuspended at 1 × 106 cells per ml in 1× PBS and 0.04% bovine serum albumin. Single-cell RNA-seq libraries were prepared using SeekOne® Single Cell Whole Transcriptome Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (SeekGene Catalog No.K00801). Briefly, an appropriate number of cells were mixed with reverse transcription reagents and added to the sample wells of the SeekOne® DD Chip S3. Then, Barcoded Hydrogel Beads (BHBs) and partitioning oil were dispensed into corresponding wells separately in Chip S3. Subsequently, Cell-containing reverse transcription reagents and BHBs were encapsulated into emulsion droplets using the SeekOne® Digital Droplet System. Immediately following transferring emulsion droplets into PCR tubes, fifteen cycles of annealing (ramping from 8 °C to 42 °C) followed by a 5-min heat inactivation at 85 °C were performed to obtain barcoded cDNA. Next, the barcoded cDNA was purified from broken droplets, and then twice PCR reactions were performed to remove the majority of ribosomal and mitochondrial cDNA. AMPure beads were used to purify cDNA from the post-PCR reaction mixture. Finally, one-fourth volume of cDNA was fragmented, end-repaired, A-tailed, and ligated into the sequencing adapter. DNA amplified by index PCR contains any part of polyA or non-PolyA RNA as well as Cell Barcode and Unique Molecular Index. The indexed sequencing libraries were purified using AMPure beads and quantified by quantitative PCR (KAPA Biosystems KK4824). The libraries were then sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with PE150 read length.

Preprocessing of single‑cell RNA-seq data

The raw sequencing data were processed using the SeekOne tools with default parameters (https://www.seekgene.com/fxrj). Paired-end reads were aligned to the human hg38 genome (GENCODE, GRCh38.99) using STAR software (v2.7.7a). Annotation of the aligned reads to genes was performed using FeatureCounts (v2.0.1). The UMIs count for each gene within individual cells was extracted from BAM files based on barcodes. Only uniquely mapped reads were used for UMI counting. If a gene within the same barcode had two mismatched UMIs, the UMI with lower read support was corrected to match the one with higher read support. Barcodes were sorted by UMI counts, with the 99th percentile UMI count divided by 10 as the threshold for cell estimation. Barcodes exceeding this threshold were classified as cells, while those below the threshold require further determination using DropletUtils analysis. Next, downstream analysis of the raw count matrix was carried out using Scanpy (v1.9.3)43 with Python (v3.7.10). To filter out the low-quality cells, we selected only cells with a number of expressed genes more than 200, a number of detected UMIs less than 6000, a fraction of mitochondrial UMIs counts less than 20%, and genes with at least one count in at least three cells for subsequent analysis. Doublets were identified by Scrublet (v0.2.3)44 with a parameter threshold of 0.25. Highly variable features were identified using the scanpy.pp.highly_variable_genes function with default parameters. To address potential batch effects within our dataset, a graph-based method named batch-balanced KNN (BBKNN)45 was used to integrate datasets while preserving the inherent biological structure. Then the corrected KNN network was used for dimensionality reduction and clustering.

Identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and cell classification

Differentially expressed genes were identified with the sc.tl.rank_genes_groups function in Scanpy (Wilcoxon rank-sum test). These DEGs with adjusted P-values less than 0.05 were considered as differentially expressed. Only protein-coding genes were selected for functional enrichment analysis in each subtype. We annotated each cluster based on differential and classical marker genes collected from the literature14,17,18,19. The differentially expressed genes and biomarkers of each cluster were selected for visualization in a volcano plot.

Inferring CNVs from single-cell RNA-seq data

We identified malignant cells by analyzing the changes in large-scale chromosomal copy number variants (CNVs) in each individual cell using InferCNV (https://github.com/broadinstitute/inferCNV). The h5ad file was converted into a Seurat object by using Seurat (v4.3.0)46. Following the software recommendation, we extracted raw gene expression data at the single-cell level from the Seurat object. The cells derived from normal pituitary samples (P13 and P17) were included as a control reference. We analyzed inferCNV using the default parameters.

Alternative splicing analysis of single‑cell RNA-seq data

For the splicing analysis of single-cell populations in PitNETs, (1) we first integrated cells within each identified PitNET cell population (Fig. 3a) to construct a pseudo-bulk sample for each cell cluster, where the sequencing reads were integrated. (2) Next, the rMATS tool was used on these pseudo-bulk samples to identify alternative splicing events in different cell populations. (3) Subtype-specific splicing events were previously identified in the bulk RNA-seq analysis. Next, we extracted the coordinates of these events (from the bulk level) and mapped them to the splicing events detected in the pseudo-bulk samples. (4) We only kept the overlapped splicing events with matched event coordinates for further analysis. Finally, we performed this set of events (n = 117) to generate Fig. 4a. To calculate the level of splicing changes in individual cells, we first extracted each cell into a small BAM file. Then, we quantified the subtype-specific splicing events, which were validated by the pseudo-bulk analysis, for each cell. For each splicing event, cells with an average coverage sum for each exon within the splicing region greater than 5 were retained. For each subtype-specific splicing event, we used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to assess the differential usage between cells of the corresponding subtype and cells of other subtypes, considering P < 0.05 as significant.

Functional enrichment analysis of target genes

Functional enrichment analyses including Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Reactome, and WikiPathways were performed by the g:Profiler47. Terms with FDR and P < 0.001 were considered as significantly enriched.

GSEA analysis

Pathway enrichment analyses were performed by the GSEA (v4.2.2) software48 to investigate molecular profiles. Gene sets were obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB), including HALLMARK, GO, and KEGG. Parameters used were as follows: collapse data: No collapse; permutation type: gene set; chip platform: gene symbol. FDR and P < 0.001 were considered significantly enriched.

Motif enrichment analysis

The MEME (v5.0.5)49 plugin FIMO was used to scan motifs in the sequences with significant splicing changes. ESRP1 motif (GGGTGG) collected from RBPmap50 was manually added to the motif collection of RNA-binding proteins in the MEME database (Ray2013_rbp_Homo_sapiens)49. Motifs found by FIMO were visualized by sequence logos using the R package ggseqlogo51.

Progression‑free survival analysis

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were created and compared among subgroups for progression-free survival (PFS) of the patients with the R package Survival52. We set the cutoff levels at the median value of the ESRP1 expression and then used it to generate Kaplan–Meier graphs and log-rank tests. For each splicing event, we stratify patients into two groups ‘High PSI’ and ‘Low PSI’ based on the median value of PSI in patients of TPIT lineage. The comparison of the PFS between these two groups was performed using Cox regression.

Immune subtype identification

ESTIMATE score, immune cell score, and stroma score were inferred for each sample using the R package ESTIMATE53 (Supplementary Data 13). The CIBERSORTx web tool (https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/upload.php) was used to explore the proportions of different immune cell types.

Statistical analysis

All calculations of clinical data were performed in R statistical software (version 4.2.3). For statistical comparison, we performed an unpaired Student’s t-test. Kaplan–Meier survival curve P-values were performed using the Log-rank Mantel–COX test. The Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the relationship between two categorical variables. Correlations were assessed using Spearman’s correlation test. Use the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to identify significant differences between two independent sample groups. The FDR was calculated using the default parameters based on the Benjamin–Hochberg approach. Detailed descriptions of experiments and statistical tests were specified in the figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw RNA sequence data of PitNETs generated in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences under the accession number HRA006929 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA006929]. The data is available for academic use under controlled access in compliance with the regulation of the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of China for the deposit and use of human genomic data. Access can be obtained by contacting members of the Data Access Committee (DAC) and following the application procedure in GSA. Data will be available immediately once the application is approved. The access to the controlled data will be valid for one year from the date approved. The previously published RNA-seq data of PitNETs for validation in this study are available as part of NODE under accession number OEP00001353 [https://www.biosino.org/node/project/detail/OEP00001353]. The publicly available gene count matrix of Pan-cancer from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database is downloaded from the R package TCGAbiolinks (v2.27.2)41. All data supporting the current study are provided in the article, Supplementary Information, and Source data. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Neou, M. et al. Pangenomic classification of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Cell 37, 123–134 e5 (2020).

Wan, X. Y. et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of pituitary adenomas/pituitary neuroendocrine tumors: clinical practices, controversies, and perspectives. Curr. Med. Sci. 42, 1111–1118 (2022).

Yavropoulou, M. P., Tsoli, M., Barkas, K., Kaltsas, G. & Grossman, A. The natural history and treatment of non-functioning pituitary adenomas (non-functioning PitNETs). Endocr. Relat. Cancer 27, R375–R390 (2020).

Raub, S. et al. Multi-center clinical, radiographic, and surgical outcomes of silent Tpit+ pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 85, S109 (2024).

Liu, Z. & Rabadan, R. Computing the role of alternative splicing in cancer. Trends Cancer 7, 347–358 (2021).

Wu, S. et al. ASCancer Atlas: a comprehensive knowledgebase of alternative splicing in human cancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D1196–D1204 (2023).

Han, N. & Liu, Z. Targeting alternative splicing in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 1232146 (2023).

Yao, H. et al. TRIM65 determines the fate of a novel subtype of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors via ubiquitination and degradation of TPIT. Neuro Oncol. 24, 1286–1297 (2022).

Hutter, C. & Zenklusen, J. C. The cancer genome atlas: creating lasting value beyond its data. Cell 173, 283–285 (2018).

Bonnal, S. C., Lopez-Oreja, I. & Valcarcel, J. Roles and mechanisms of alternative splicing in cancer - implications for care. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 457–474 (2020).

Khalid, E. & Chang, J. P. Small GTPase control of pituitary hormone secretion: Evidence from studies in the goldfish (Carassius auratus) neuroendocrine model. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 339, 114287 (2023).

Feng, J. et al. Metabolic profiling reveals distinct metabolic alterations in different subtypes of pituitary adenomas and confers therapeutic targets. J. Transl. Med. 17, 291 (2019).

Luan, X. et al. Gene expression profiling in the pituitary gland of laying period and ceased period huoyan geese. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 26, 921–929 (2013).

Zhang, F. et al. Integrated proteogenomic characterization across major histological types of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Cell Res. 32, 1047–1067 (2022).

Sebestyen, E. et al. Large-scale analysis of genome and transcriptome alterations in multiple tumors unveils novel cancer-relevant splicing networks. Genome Res. 26, 732–744 (2016).

Wang, F. et al. Single-cell architecture and functional requirement of alternative splicing during hematopoietic stem cell formation. Sci. Adv. 8, eabg5369 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Single-cell sequencing identifies differentiation-related markers for molecular classification and recurrence prediction of PitNET. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 100934 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics identifies divergent developmental lineage trajectories during human pituitary development. Nat. Commun. 11, 5275 (2020).

Cui, Y. et al. Single-cell transcriptome and genome analyses of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Neuro Oncol. 23, 1859–1871 (2021).

Rubinek, T. et al. The cell adhesion molecules N-cadherin and neural cell adhesion molecule regulate human growth hormone: a novel mechanism for regulating pituitary hormone secretion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 3724–3730 (2003).

Larysz, D., Blamek, S. & Rudnik, A. Clinical aspects of molecular biology of pituitary adenomas. Folia Neuropathol. 50, 110–117 (2012).

Yeh, S. J., Lin, C. Y., Li, C. W. & Chen, B. S. Systems biology approaches to investigate genetic and epigenetic molecular progression mechanisms for identifying gene expression signatures in papillary thyroid cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2536 (2019).

Warzecha, C. C., Sato, T. K., Nabet, B., Hogenesch, J. B. & Carstens, R. P. ESRP1 and ESRP2 are epithelial cell-type-specific regulators of FGFR2 splicing. Mol. Cell 33, 591–601 (2009).

Lee, S. Y., Yang, J. S., Hong, W., Premont, R. T. & Hsu, V. W. ARFGAP1 plays a central role in coupling COPI cargo sorting with vesicle formation. J. Cell Biol. 168, 281–290 (2005).

Jia, W. et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal Transition (EMT) markers in human pituitary adenomas indicate a clinical course. Anticancer Res. 35, 2635–2643 (2015).

Jiang, S. et al. STAU1 promotes adipogenesis by regulating the alternative splicing of Pparγ2 mRNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1868, 159293 (2023).

Yae, T. et al. Alternative splicing of CD44 mRNA by ESRP1 enhances lung colonization of metastatic cancer cell. Nat. Commun. 3, 883 (2012).

Advani, R. et al. Epithelial specific splicing regulator proteins as emerging oncogenes in aggressive prostate cancer. Oncogene 42, 3161–3168 (2023).

Liu, W. et al. Transcriptome-derived stromal and immune scores infer clinical outcomes of patients with cancer. Oncol. Lett. 15, 4351–4357 (2018).

Reincke, M. et al. Mutations in the deubiquitinase gene USP8 cause Cushing’s disease. Nat. Genet. 47, 31–38 (2015).

Bi, W. L., Larsen, A. G. & Dunn, I. F. Genomic alterations in sporadic pituitary tumors. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 18, 4 (2018).

Salomon, M. P. et al. The epigenomic landscape of pituitary adenomas reveals specific alterations and differentiates among acromegaly, cushing’s disease and endocrine-inactive subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 4126–4136 (2018).

Guo, J. et al. The SF3B1(R625H) mutation promotes prolactinoma tumor progression through aberrant splicing of DLG1. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 41, 26 (2022).

Haddad, A. F. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of null-cell versus silent gonadotroph adenomas in a series of 1166 pituitary adenomas from a single institution. Neurosurg. Focus 48, E13 (2020).

Sahai, E. et al. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 174–186 (2020).

Zheng, G. et al. Clinical, laboratory, and treatment profiles of silent corticotroph adenomas that have transformed to the functional type: A case series with a literature review.

Zoli, M. et al. ACTH adenomas transforming their clinical expression: report of 5 cases. Neurosurg. Focus 38, E15 (2015).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Shen, S. et al. rMATS: robust and flexible detection of differential alternative splicing from replicate RNA-seq data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E5593–E5601 (2014).

Colaprico, A. et al. TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res 44, e71 (2016).

Otasek, D., Morris, J. H., Boucas, J., Pico, A. R. & Demchak, B. Cytoscape automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol. 20, 185 (2019).

Wolf, F. A., Angerer, P. & Theis, F. J. SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol. 19, 15 (2018).

Wolock, S. L., Lopez, R. & Klein, A. M. Scrublet: computational identification of cell doublets in single-cell transcriptomic data. Cell Syst. 8, 281–291 e9 (2019).

Polanski, K. et al. BBKNN: fast batch alignment of single cell transcriptomes. Bioinformatics 36, 964–965 (2020).

Stuart, T. et al. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e21 (2019).

Reimand, J., Kull, M., Peterson, H., Hansen, J. & Vilo, J. g:Profiler–a web-based toolset for functional profiling of gene lists from large-scale experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W193–W200 (2007).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Bailey, T. L. & Gribskov, M. Combining evidence using p-values: application to sequence homology searches. Bioinformatics 14, 48–54 (1998).

Paz, I., Kosti, I., Ares, M. Jr., Cline, M. & Mandel-Gutfreund, Y. RBPmap: a web server for mapping binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 42, W361–W367 (2014).

Wagih, O. ggseqlogo: a versatile R package for drawing sequence logos. Bioinformatics 33, 3645–3647 (2017).

T, T. A Package for survival analysis in R. In R package version 3.5-8 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival (2024).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (grant Z220012 to Z.L. and C.L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 82141109 to W.X.; grant 32170565 to Z.L.; grant 82071558 to W.X.), the Chinese Academy of Sciences Hundred Talents Program (to Z.L.). We would like to thank the Instrument Sharing Platform of the Chinese Academy of Sciences for providing equipment assistance. We acknowledge all participants involved in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., W.X., C.L., and Y.Z.Z conceived and supervised the entire project. Y.H. and J.G. wrote the manuscript with feedback from Z.L., W.X., and C.L. Y.H. performed the bioinformatic analyses with the help of X.H., P.X., S.W., X.L., and L.Z. J.G. conducted the experiments with the help of Y.Z. and X.J.L. J.G., Y.S., and Y. L. performed data collection and clinical information arrangement. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Manish Aghi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Guo, J., Han, X. et al. Splicing diversity enhances the molecular classification of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Nat Commun 16, 1552 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56821-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56821-x

This article is cited by

-

NOVA2 expression in pituitary gland and in functioning and non-functioning pituitary adenomas: a preliminary study

Acta Neurochirurgica (2025)

-

Multidimensional tumor-blood profiling uncovers systemic lymphocyte-monocyte imbalance in pituitary neuroendocrine tumors

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2025)