Abstract

Infants with severe bronchiolitis (i.e., bronchiolitis requiring hospitalization) face increased risks of respiratory diseases in childhood. We conduct epigenome-wide association studies in a multi-ethnic cohort of these infants. We identify 61 differentially methylated regions in infant blood (<1 year of age) associated with recurrent wheezing by age 3 (170 cases, 318 non-cases) and/or asthma by age 6 (112 cases, 394 non-cases). These differentially methylated regions are enriched in the enhancers of peripheral blood neutrophils. Several differentially methylated regions exhibit interaction with rhinovirus infection and/or specific blood cell types. In the same blood samples, circulating levels of 104 proteins correlate with the differentially methylated regions, and many proteins show phenotypic association with asthma. Through Mendelian randomization, we find causal evidence supporting a protective role of higher plasma ST2 (also known as IL1RL1) protein against asthma. DNA methylation is also associated with ST2 protein level in infant blood. Taken together, our findings suggest the contribution of DNA methylation to asthma development through regulating early-life systemic immune responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bronchiolitis is an acute lower respiratory infection caused by respiratory viruses1 and the leading cause of hospitalization in infants (age < 1 year) in the United States2. Infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis (i.e., severe bronchiolitis), especially those with rhinovirus infection, have a substantially higher risk of developing recurrent wheezing and asthma in childhood3,4. However, the underlying biological mechanisms contributing to this elevated risk remains unclear.

DNA methylation (DNAm), a form of epigenetic modification, reflects the influence of genetics, environmental exposures, and gene-by-environment interactions5. DNAm has important regulatory functions in gene expression and contributes to the development of health outcomes5. Recent epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) have linked DNAm level in children’s blood to bronchiolitis severity6, recurrent wheezing7, and childhood asthma8,9. However, the association between infant DNAm and childhood respiratory outcomes has not been investigated among infants with severe bronchiolitis. Such an investigation will provide important insights into the underlying mechanism of asthma development in this large, high-risk subpopulation.

Early-life immune regulation plays crucial roles in the development of childhood-onset asthma10. Proteins associated with immune functions, including cytokines and chemokines, contribute to the initiation and exacerbation of asthma11,12. In addition, large population-based proteomics studies have reported association between levels of DNAm and plasma proteins13,14. Therefore, integrating epigenome-wide DNA methylation data with immune-related proteomics data measured in infant blood offers promising avenues for exploring the impacts of early-life immune responses on the development of asthma.

To this end, we performed an epigenome-wide scan in a cohort of infants with severe bronchiolitis to examine the prospective association between DNAm in infant blood and development of recurrent wheezing by age 3 years and childhood asthma by age 6 years. Employing the state-of-the-art EPIC array, we examined the associations across almost 800,000 CpG sites throughout the genome, thereby nearly doubling the coverage of genome compared to previous studies8,9. Additionally, we utilized real-time polymerase chain reaction to determine rhinovirus infection status and accounted for its interaction effect in our EWAS discovery. Last, we integrated the EWAS results with data on 347 immune-related proteins measured in the same infant blood samples and identified proteins correlated with the DNAm differences. To prioritize potential intervention targets, we further evaluated the phenotypic associations and causal relationships of these proteins with asthma-related traits.

Results

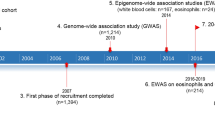

Among 625 infants who were enrolled in a prospective 17-center cohort study—the 35th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-35) cohort—and had high-quality blood DNAm data measured at hospitalization before age 1 year, recurrent wheezing status before age 3 years was available for 488 infants, and asthma status by age 6 years was available for 506 infants (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). These participants were included in the EWAS to identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) associated with recurrent wheezing and asthma, respectively. Supplementary Data 1 shows the characteristics of these participants. Among participants with recurrent wheezing data, 170 (34.8%) developed recurrent wheezing by age 3 years; these infants were more likely to develop asthma by age 6 years compared to infants without recurrent wheezing (44.2% vs. 10.8%, p = 2.2 × 10−16). A total of 112 (22.1%) participants developed asthma by age 6 years in our study sample. We observed notable differences in several baseline variables between recurrent wheezing/asthma cases and non-cases. These variables include age at hospitalization, race/ethnicity, number of previous breathing problems, history of eczema, rhinovirus infection, and maternal asthma.

This study investigates the associations between epigenome-wide DNA methylation (794,125 high-quality CpG sites), measured using the Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC array, in blood samples from infants with severe bronchiolitis, and the subsequent risk of recurrent wheezing (before 3 years of age, n = 448, 170 cases) and asthma (at 6 years of age, n = 506, 112 cases) during childhood. The analytical data were collected from participants of the 35th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-35) study. Thirty-one differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were associated with recurrent wheezing, and thirty-three DMRs were associated with asthma, taking into account potential interactions with rhinovirus infection during infancy. In silico blood cell-type deconvolution and chromatin state enrichment analyses were conducted to identify specific blood cell types likely driving the associations at these DMRs. The chromatin state annotation was obtained from the Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium. We then explored the relationship between these DMRs and the levels of 347 proteins measured in the same bronchiolitis infant blood samples using the Olink multiplex platform. For proteins associated with the DMRs, we constructed a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network leveraging data from the STRING database, performed two-sample mendelian randomization analysis using protein quantitative trait loci (pQTLs, UK Biobank and deCODE) and GWAS summary statistics from published studies, and conducted pathway enrichment analysis using data from the Gene Ontology database. These analyses aim to provide additional biological insights into the early development of childhood respiratory diseases in infants with severe bronchiolitis underlying the DNA methylation differences.

Epigenome-wide analysis identified novel DMRs associated with recurrent wheezing

We first examined the associations between DNAm and recurrent wheezing at 794,125 CpG sites that passed the quality control (Supplementary Fig. 2). No substantial genomic inflation was observed as indicated by the quantile-quantile plots (e.g., λgenomic control = 1.03 for linear regression, Supplementary Fig. 3). We identified 31 DMRs associated with recurrent wheezing after accounting for multiple testing (Šidák p < 0.01; Table 1, Supplementary Data 2, Supplementary Data 3). Of these, 21 DMRs were identified through the analysis based on linear regression, and additional 10 DMRs were identified through the analysis based on LRT-2df that leveraged potential interaction with rhinovirus infection to increase power. Ten DMRs exhibited different association patterns between participants who were rhinovirus-infected and those who were not (i.e., the nominal p-value < 0.05 for the recurrent wheezing×rhinovirus infection interaction at more than half of the CpG sites within a DMR).

The most significant recurrent wheezing DMR (chr18:13611190-13611807, Šidák p = 1.08 × 10−10; Table 1) was annotated to the LDLRAD4. Across all 11 CpG sites in this region, we observed a lower DNAm level among the recurrent wheezing cases compared with the non-cases, and the effect sizes were more pronounced among participants who had rhinovirus infection during infancy (i.e., 7 out of 11 CpG site in the DMR had nominal p-value < 0.05 for the interaction term).

Epigenome-wide analysis identified novel DMRs associated with childhood asthma

We then examined the associations between DNAm at 794,125 CpG sites and childhood asthma. No substantial genomic inflation was observed as indicated by the quantile-quantile plots (e.g., λgenomic control = 1.05 for linear regression, Supplementary Fig. 4). We identified 33 DMRs associated with asthma after accounting for multiple testing (Šidák p < 0.01; Table 2, Supplementary Data 4, Supplementary Data 5). Of these, 20 DMRs were identified through the analysis based on linear regression, and an additional 13 DMRs were identified through the analysis based on LRT-2df. Seven DMRs exhibited different association patterns between participants who were rhinovirus-infected and those who were not (i.e., the nominal p-value < 0.05 for the asthma×rhinovirus infection interaction at more than half of the CpG sites within a DMR).

The most significant asthma DMR (chr17:6899085-6899758, Šidák p = 1.31 × 10−13; Table 2) overlapped the promoter region of ALOX12. We observed a higher DNAm level among the asthma cases compared to the non-cases across all 12 CpG sites in this region. This asthma DMR overlapped with a recurrent wheezing DMR near ALOX12 (chr17:6898821-6899577, Šidák p = 3.15 × 10−8; Table 1). In addition, two other asthma DMRs were also associated with recurrent wheezing, with consistent direction of effects: chr6:28129313-28129656 (ZKSCAN8P1; higher DNAm in cases) and chr6:42927940-42928200 (GNMT; lower DNAm in cases).

Cell-type specific associations at the infant blood DMRs

The proportions of seven blood cell types (B cells, NK cells, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, monocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils) were inferred based on the epigenome-wide DNAm data. Utilizing the CellDMC method15, which tests the interactions between the cell type fractions in each sample and the outcome of interest, we identified blood cell types that may drive the observed associations between the DMRs and the childhood respiratory outcomes.

Supplementary Fig. 5 illustrates the cell-type specific associations of DNAm with recurrent wheezing at selected DMRs (DMRs displaying nominal statistical significance, i.e., p < 0.05, for cell-type specific associations are shown). At the most statistically significant DMR for recurrent wheezing (chr18:13611190-13611807; LDLRAD4), the association appeared to be driven by effects in eosinophils, monocytes, and neutrophils. Other recurrent wheezing DMRs, such as chr2:54086854-54087343 (GPR75, ASB3; B cells), chr8:22132926-22133076 (PIWIL2; B cells), chr11:124622096-124622444 (VSIG2; neutrophils, eosinophils), and chr17:46681111-46681401 (HOXB6; CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, eosinophils), also appeared to be influenced by cell-type-specific DNAm effects.

Supplementary Fig. 6 illustrates the cell-type specific associations of DNAm with asthma at selected DMRs with nominal statistical significance (p < 0.05) for cell-type specific associations. Asthma DMRs with evidence for cell-type specific DNAm effects include chr6:28058724-28058973 (ZSCAN12P1; CD4 T cells), chr7:95025855-95026248 (PON3; NK cells), chr16:66400320-66400599 (CDH5; monocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils), and chr16:67233432-67233983 (ELMO3; CD4 T cells).

DMRs for childhood respiratory outcomes were enriched in neutrophil-specific chromatin states

We conducted enrichment analysis to examine whether the 61 DMRs for recurrent wheezing and/or asthma were enriched with specific chromatin states in human peripheral blood cells from the Roadmap Epigenomics Project16. Our analysis (Fig. 2, Supplementary Data 6) revealed statistically significant enrichment of these DMRs in the Genic Enhancer (6_EnhG, p = 1.90 × 10−7) and Repressed Polycomb (13_ReprPC, p = 7.65 × 10−6) regions in primary neutrophils (Accession: E30), highlighting the potential roles of epigenetic regulation in neutrophils during early asthma development.

The 15 chromatin states were consolidated from the NIH Roadmap Epigenomics project based on five histone modification marks (H3K4me3, H3K4me1, H3K36me3, H3K9me3, H3K27me3) in human cells. Chromatin states are 1_TssA (Active TSS), 2_TssAFlnk (Flanking Active TSS), 3_TxFlnk (Transcr. at gene 5’ and 3’), 4_Tx (Strong transcription), 5_TxWk (Weak transcription), 6_EnhG (Genic enhancers), 7_Enh (Enhancers), 8_ZNF/Rpts (ZNF gene & repeats), 9_Het (Heterochromatin), 10_TssBiv (Bivalent/Poised TSS), 11_BivFlnk (Flanking Bivalent TSS/Enh), 12_EnhBiv (Bivalent Enhancer), 13_ReprPC (Repressed PolyComb), 14_ReprPCWk (Weak Repressed PolyComb), 15_Quies (Quiescent/Low). The enrichment p-value was obtained based on two-sided binomial test in 1000 permuted samples. To address multiple testing, we employed a Bonferroni-corrected significant threshold of p = 2.22 × 10−4 (the horizontal dashed line).

DMRs for childhood respiratory outcomes correlated with circulating levels of immune proteins in infant blood

We examined the correlations between DNAm level at the DMRs and 347 immune-related proteins in infant blood, controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and other key covariates. A total of 38 DMRs showed correlation with at least one protein level in infant blood (FDR < 0.05; Supplementary Data 1). Among them, the 4 DMRs correlated with the greatest number of proteins, namely, chr17:2169272-2169852 (SMG6, 51 proteins), chr22:44568725-44568913 (PARVG, 42 proteins), chr16:66400320-66400599 (CDH5, 41 proteins), and chr11:2920052-2920414 (SLC22A18AS, 37 proteins), shared correlation with the same set of 30 proteins (Supplementary Fig. 7a). These 30 proteins were also correlated with a large number of other DMRs. Some examples of these proteins are CEACAM8 (20 DMRs), MMP-9 (19 DMRs), TNFB (17 DMRs), AZU1 (17 DMRs), OSM (17 DMRs), HGF (17 DMRs), TGF-alpha (15 DMRs), and CLEC4D (15 DMRs) (Supplementary Fig. 7b).

To visually represent the DMR-protein correlations in infant blood, we created Fig. 3 to highlight the 18 proteins with the most statistically significant correlations with DMRs (FDR < 0.0005).

Rectangular nodes are DMRs, with the color shade corresponding to number of proteins the DMRs associated with. Oval nodes are proteins, with the color shade corresponding to number of DMRs the protein associated with. Edges represent associations between DMRs and proteins with a Benjamini-Hochberg FDR below 0.0005 after adjusting for covariates. The thickness of the edges corresponds to the statistical significance of the association (obtained from linear regression, two-sided test) calculated as average -log10(P) of the DNAm-protein correlation across all CpG sites within a DMR. Red edges show positive association. Blue edges show negative association.

Phenotypic associations between DMR-correlated proteins and asthma

A total of 104 protein markers were statistically significantly (FDR < 0.05) correlated with the DMRs for childhood respiratory outcomes. Among these DMR-correlated proteins, levels of LIF-R and CHI3L1 in infant blood were prospectively associated with childhood asthma in a small subset of MARC-35 participants with available data (50 asthma cases, 59 non-cases) after correcting for multiple testing (FDR < 0.05; Fig. 4). Supplementary Data 8 provides detailed results for the phenotypic associations between protein levels and the respiratory outcomes. Using this data, we also found 6 and 24 proteins associated with later recurrent wheezing and asthma outcomes, respectively, with nominal significance (p < 0.05). Of them, IFN-γ was nominally associated with both recurrent wheezing (p = 0.006) and asthma (p = 0.032). We further leveraged recent findings from the UK Biobank (UKB)17 where associations between plasma proteomics and prevalent asthma were assessed in a larger population (N = 46,595; mean age: 57 years). Among all DMR-correlated proteins we identified, 63.5% (n = 66) also showed were associated with prevalent asthma in UKB (FDR < 0.05; Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 8).

Evidence for the putative causal relationship was obtained using two-sample mendelian randomization (MR Egger, weighted median, inverse variance weighted (IVW), weighted mode) with pQTLs from deCODE as genetic instruments. Phenotypic associations were obtained using linear regression. The analyses to identify phenotypic association in the MARC-35 cohort were conducted in a small subset of participants with available data (recurrent wheezing: 57 cases, 50 non-cases; asthma: 50 cases, 59 non-cases).

Protein–protein interactions and pathway enrichments of the DMR-correlated proteins

We derived protein-protein interaction (PPI) network from the STRING database18 based on previous experimental evidence and co-expression data (Supplementary Fig. 8). This network suggested that many DMR-correlated proteins may interact with each other. For instance, CEACAM8, AZU1, PRTN3, and MPO were significantly associated with DNAm at the DMRs (FDR < 0.0005). These proteins were also interconnected with each other through co-expression evidence, suggesting shared biological functions. Similarly, MMP-9, OSM, and HGF were interconnected with each other and also demonstrated evidence for interacting with other cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL12RB1, IL18, TNF) and chemokines (e.g., CCL3, MCP-1/CCL2) through the PPI network. Additionally, we identified several pairs of known ligand-receptor interactions among the DMR-correlated proteins, including IL-18 and IL-18BP, IL-33 and ST2, IL-12B and IL12RB1, TNF and TNF-R2/TNFRSF1B, and TRAIL/TNFSF10 and TNFSFR10C.

The Gene Ontology (GO) pathway analyses for the 104 DMR-correlated proteins revealed multiple significantly enriched biological and molecular pathways (FDR < 0.05; Supplementary Data 9). Among the most significantly enriched pathways, several were related to the migration, differentiation, and proliferation of leukocytes or T cells. Other top enriched pathways included positive regulation of cell-cell adhesion (FDR = 7.36 × 10−16), cellular response to interferon-gamma (FDR = 2.55 × 10−12), cellular response to interleukin-1 (FDR = 9.73 × 10−11), regulation of tumor necrosis factor production (FDR = 8.22 × 10−6), and positive regulation of NIK/NF-κB signaling (FDR = 1.95 × 10−5).

Mendelian randomization for the DMR-correlated proteins and asthma-related outcomes

Utilizing protein quantitative trait loci (pQTLs) mapped in a recent study in the Icelandic deCODE population19, we conducted a two-sample mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to examine the causal relationship between the DMR-correlated proteins and asthma and lung function (FEV1/FVC) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 1,0). Notably, we found evidence supporting putative causal effects (FDR < 0.05) of plasma ST2 level on both asthma and FEV1/FVC through all MR methods we applied. Our results revealed that a higher plasma ST2 level may decrease the risk of asthma and increase lung function. These results remained robust in the sensitivity analyses when pQTLs derived from a recent UKB study17 were used as the genetic instruments (Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Data 1,0), as well as when an alternative asthma genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics were used in the MR analyses (Supplementary Data 11).

We further investigated whether ST2 may have causal effects on other asthma-related outcomes through MR. We found evidence supporting causal relationships between plasma ST2 level and allergic conditions, including allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis (Supplementary Data 11).

Additionally, our MR analyses suggested potential causal effects of plasma AGRP and CHI3L1 levels on FEV1/FVC when the deCODE pQTLs were used as genetic instruments; however, we did not find same results in the analysis using the UKB pQTLs (Supplementary Data 10).

Associations of DNAm with ST2 protein in infant blood

Given the consistent MR evidence suggesting potential causal effects of plasma ST2 protein level on asthma and related outcomes, we further evaluated the association of DNAm at the ST2 (also known as IL1RL1) locus with ST2 protein level in infant blood (n = 112, Supplementary Data 12). Among 19 CpG sites at this locus included on the EPIC array, DNAm at 6 CpG sites were significantly associated ST2 protein level after adjusting for key covariates (FDR < 0.05). When further adjusting for estimated blood cell types, the positive association between DNAm at cg17738684 (at distal promoter of ST2) and the ST2 protein remained statistically significant (FDR = 3.06 × 10−3). Here we note that DNAm at this CpG site was not associated with childhood asthma or recurrent wheezing outcomes in our study sample (Supplementary Data 12).

Additionally, at 8 DMRs associated with recurrent wheezing and/or asthma, we observed correlations between DNAm and the ST2 protein level in infant blood (FDR < 0.05, Supplementary Data 7). These DMRs are chr1:94057512-94057789 (BCAR3-AS1), chr11:2920052-2920414 (SLC22A18AS), chr11:124622096-124622444 (VSIG2), chr16:66400320-66400599 (CDH5), chr17:2169522-2169852 (SMG6), chr17:6899085-6899758 (ALOX12), chr18:13611190-13611807 (LDLRAD4), and chr22:44568725-44568913 (PARVG).

Discussion

In a multi-ethnic cohort of infants with severe bronchiolitis, we conducted EWAS and identified 61 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) where DNAm levels in infant blood were associated with recurrent wheezing by age 3 years and/or asthma by age 6 years. These DMRs were enriched in the genic enhancer of neutrophils in peripheral blood, and many of them demonstrated cell-type-specific associations in deconvolution analysis. Furthermore, we identified 104 proteins correlated with the DMRs in the same infant blood samples; among these proteins, many also had phenotypic associations with respiratory outcomes. Leveraging pQTLs resources from two recent large proteomics GWASs, we conducted mendelian randomization for the DMR-correlated proteins. We reported putative causal effects of plasma ST2 level on asthma, FEV1/FVC, and allergic conditions that often comorbid with asthma. Lastly, we investigated the potential epigenetic regulation at the ST2 locus and found significant association between ST2 promoter DNAm and ST2 protein level in infant blood.

In this study, we focused on childhood recurrent wheezing and asthma – two respiratory outcomes with substantially higher risk in infants with severe bronchiolitis compared to the general pediatric population3. While these two conditions are different, they share similar symptoms and potentially overlapping pathobiology since early-age recurrent wheezing often elevates the risk of later chronic asthma20. Consistent with prior research in broader pediatric populations21, we identified a DMR spanning the promoter region of ALOX12 that exhibited differential methylation by both recurrent wheezing and childhood asthma in infants with severe bronchiolitis. Additionally, we identified two novel DMRs associated with both recurrent wheezing and asthma, annotated to ZKSCAN8P1 and GNMT, respectively. These three DMRs may offer valuable insights into the shared etiological factors contributing to recurrent wheezing and asthma in children. Of note, the DMR at ZKSCAN8P1 also harbors a genetic variant associated with asthma in prior work22.

The most statistically significant recurrent wheezing DMR was chr18:13611190-13611807 (LDLRAD4; Šidák p = 1.08 × 10−10), where a lower DNAm was associated with an elevated risk, and the effect size was larger among those with rhinovirus infection (Supplementary Data 3; Supplementary Fig. 11). A previous study has linked the gene expression of LDLRAD4, a known negative regulator of TGF-β signaling, to asthma severity23. In fact, existing evidence has suggested that various molecular mechanisms, such as mircoRNA24 and IFN-γ signaling25, regulate the TGF-β response during asthma development. In the current study, we also observed correlation between IFN-γ and later respiratory outcomes, as well as between IFN-γ and LDLRAD4 DNAm in infant blood. It is possible that TGF-β response is the shared biological pathway underlying these observed associations, linking the molecular features to subsequent recurrent wheezing outcome. Future investigations are warranted to elucidate the complex regulatory functions across DNAm, IFN-γ, and TGF-β signaling during infancy that may contribute to later wheezing symptoms, especially among high-risk individuals with rhinovirus bronchiolitis.

We leveraged potential interaction effect of rhinovirus infection in the EWAS and uncovered additional DMRs, including chr8:22132926-22133076 (PIWIL2) and chr12:130822256-130822605 (PIWIL1). Specifically, the association of hypomethylation at PIWIL2 with recurrent wheezing was observed exclusively among those with rhinovirus infection (Supplementary Data 3; Supplementary Fig. 10); this association was likely driven by B cell-specific effects (Supplementary Fig. 5). In contrast, the association between PIWIL1 DNAm and recurrent wheezing seems to have opposite direction of effects between rhinovirus infection status (Supplementary Data 3). Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) is a class of small non-coding RNAs expressed in human germline and somatic cells26. These piRNAs interact with PIWI proteins to form piRNA/PIWI complex, exerting regulatory functions in gene silencing through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms26. Recent studies have linked piRNA to various respiratory diseases26. An experimental study found that PIWIL2 downregulates TGF-β signal transduction and reduces lung fibrosis27; another study reported change in piRNA expression in airway epithelial cells after respiratory virus infection28. In concordance with the existing literature, our results further suggest that DNAm of piRNAs may play a role in host response to rhinovirus infection during infancy, contributing to the development of recurrent wheezing in childhood.

Protein serve as the fundamental unit that executes various biological functions for health and disease development. In this study, we leveraged the correlation between DNAm and circulating protein levels to enhance the interpretation of our EWAS results. A recurrent wheezing DMR (chr17:2169272-2169852) at the promoter region of SMG6 correlated with 51 proteins in infant blood (Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary Data 7). Additionally, an asthma DMR at CDH5 (chr16:66400320-66400599) also displayed correlations with a large number of proteins in infant blood (Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary Data 7). We note here that the number of unique protein correlations for each DMR did not correlate with the number of CpG sites within the DMR (Pearson’s correlation r = 0.09). SMG6 is an endonuclease in the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway, which can degrade erroneous transcripts and perform post-transcriptional regulation29. Cadherin 5 (CDH5) is a calcium-dependent endothelial adhesion molecule with essential functions in initiating Th2 inflammation and mediating airway remodeling30. Evidence has linked CDH5 to endothelial cell autophagy which keeps neutrophil trafficking under control31. Notably, among 37 proteins shared correlations with both the DMR at CDH5 and the DMR at SMG6, many have known functions in neutrophil migration and degranulation. These include Carcinoembryonic Antigen-Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 8 (CEACAM8), Azurocidin (AZU1), Myeloperoxidase (MPO), Myeloblastin (PRTN3), S100 Calcium-binding Protein A12 (S100A12/EN-RAGE), and C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 23 (CCL23)32,33,34. Consistently, the DMRs we discovered were significantly enriched in the enhancer region of neutrophils in peripheral blood (Fig. 2, Supplementary Data 6). Altogether, these findings highlighted that neutrophil activity during infancy may contribute to asthma etiology and this process may be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms.

Leveraging the pQTLs resources from two largest plasma proteomics GWAS to date (deCODE: N = 35,559; UKB: N = 46,595)17,19, we performed MR analyses to explore the potential causal links between the DMR-correlated proteins and asthma-related outcomes. Our investigation, employing various MR methods, consistently indicated that elevated level of circulating ST2 (also called soluble ST2 or interleukin-1 receptor-like 1a, IL1RL1-a) likely reduces the risks of asthma and allergic diseases and improves lung function. We note that in the main MR analyses where pQTLs from the deCODE study were used as instruments, there were no overlapping participants between the outcomes GWASs and the pQTLs GWAS. In the sensitivity analysis where pQTLs from the UKB study were used as instruments, less than 10% of the study population in the outcome GWAS were included in the pQTLs GWAS. However, given this small proportion, the bias in the two-sample MR results due to overlapping UKB participants should be minimal (<1%)35. ST2 is a member of the interleukin-1 superfamily and plays crucial roles in immune responses36. Its soluble isoform binds to extracellular interleukin-33 (IL-33), lowering the concentration of IL-33 available for interacting with the corresponding transmembrane receptor (ST2L, also called IL1RL1-b), thereby attenuating the pro-inflammatory cascade37. Previous research based on a smaller pQTLs GWAS discovery (N = 21,758) reported MR evidence for the protective effects of plasma ST2 against asthma and allergic rhinitis38. Our results provided compelling evidence to corroborate these findings. We emphasize that the MR findings should be interpreted with caution, as this statistical method relies on several assumptions. Downstream validation experiments are necessary to confirm the putative causal relationships suggested by the MR analyses.

Previous genetic studies have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at the IL1RL1(ST2) locus associated with childhood wheezing phenotypes39, as well as correlations between these SNPs and IL1RL1 mRNA and protein expression in the airway epithelium of asthma patients40. The present analyses further revealed novel associations between DNAm at multiple DMRs in relation to childhood respiratory outcomes and circulating ST2 level in infants with severe bronchiolitis. In addition, we identified a CpG site (cg17738684) in the distant promoter of ST2, where DNAm was associated with ST2 protein level in infant blood, independent of key covariates and blood cell type composition. This contrasts with a previous study reporting no such association in children’s blood41. This discrepancy may be explained by differences in population characteristics. Specifically, in our study, all participants were infants experiencing acute bronchiolitis at the time of blood draw, whereas in the prior study, the blood samples were collected from children aged 4–5 years without acute infection41. In fact, we previously reported that DNAm changes related to infant bronchiolitis severity were enriched in interleukin-1 mediated signaling pathway6. Continued research is imperative to elucidate the mechanism and timing through which epigenetics influences the cellular responses related to ST2 and interleukin-1 signaling, and the subsequent effects on asthma development. While genetic data analysis is beyond the scope of the current study, future investigation into whether the differential methylation at ST2 reflects genetic susceptibility to childhood asthma would offer valuable insights into the underlying biological mechanisms. With ongoing clinical trials investigating the efficacy of drugs targeting the ST2-IL33 pathway in treating adult respiratory diseases37, these insights are valuable for identifying and prioritizing high-risk children for preventive and therapeutic interventions in forthcoming studies.

In this study, we adopted a regional-based approach to detect differential methylation, recognizing that methylation levels are generally highly spatially correlated along the DNA sequence as a result of the processivity of DNA methyltransferases and other enzymes modifying the epigenome42. Comparing to analysis detecting differential methylation at individual CpG sites, the regional analysis provided advantages such as reducing the burden of multiple testing by removing spatial redundancy and enhancing the robustness and functional relevance of the results42. In addition, we applied the SmartSVA method43 to address cell type heterogeneity and batch effects. This method has been shown to adequately account for cell type heterogeneity in EWAS, reducing false positive while preserving statistical power43. We conducted additional sensitivity analysis by adjusting for the estimated cell type proportions as covariates and found that the majority of the DMRs remained statistically significant (Supplementary Data 13). This suggests that the SmartSVA approach used in our primary analysis effectively accounted for potential confounding by cell type composition. Future studies should aim to collect direct measurements of blood cell metrics in infants alongside DNAm profiling to better capture cell type heterogeneity across samples, as the DNAm-based blood cell composition estimates are only approximations of the true values. Last, we used a relatively stringent significance threshold (Šidák p-value < 0.01) for calling DMRs to control type I error. Indeed, among the DMRs identified in our study, many are proximal to genes previously associated with asthma etiology, reinforcing the biological relevance of our findings. We performed an ad hoc permutation analysis by randomly shuffling the case/non-case labels for the outcomes. While the number of positive findings in the permuted datasets (6–8 DMRs) was significantly lower than that in our main analysis (20–24 DMRs from linear regression or LRT), it is still not negligible. This suggests that our current statistical models may not yet be optimally calibrated. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that our findings warrant replication in future studies.

This study has potential limitations. First, despite controlling key covariates and cell type heterogeneity in the EWAS, confounding due to unmeasured variables was possible given the observational design. However, since DNAm was measured many years before the respiratory outcomes, our results were less likely to be confounded by exposures after infancy. Second, while several DMRs in our study showed interaction with rhinovirus infection, we were unable to determine if DNAm contributed to infants’ susceptibility in response to rhinovirus exposure, or if DNAm and rhinovirus infection had synergistic effects on asthma risk through independent biological pathways. Third, we were unable to establish temporal relationships between DNAm and protein levels. It is possible that the observed DMR-protein correlations reflect some underlying disease processes that lead to changes in both DNAm and protein levels. This may also explain why only a few DMR-associated proteins had support from MR evidence for their effects on asthma-related outcomes. Since the DMRs associated with proteins were not in the genetic regions coding for the proteins, it is also possible that the DNAm reflects a downstream effect of changes in protein levels. Future studies should collect appropriate data to elucidate these relationships. Last, all our study participants were infants with severe bronchiolitis, which was not representative of the general pediatric population. Moreover, data to distinguish different phenotypes/endotypes of recurrent wheezing and asthma cases was unavailable. Future investigations should evaluate the generalizability of our results to other populations and specific disease subtypes.

In summary, in a multi-ethnic cohort of infants with severe bronchiolitis, we discovered multiple novel genomic regions where DNAm in infant blood was prospectively associated with recurrent wheezing and/or asthma in childhood. By integrating epigenome-wide methylation, proteomics, and existing multi-omics resources, our analyses highlighted biological pathways (e.g., TGF-β signaling) and effector cell types (e.g., neutrophils) that likely play critical roles during the early stages of asthma development. Furthermore, we provided consistent evidence to support potential causal effects of plasma ST2 level on asthma and related traits and reported DNAm changes in infant blood relevant to this emerging therapeutic target. Overall, our findings advance current understanding of asthma etiology and may pave the way for the development of early interventions to prevent asthma.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

The institutional review board at each participating hospital approved the study, with written informed consent obtained from the parent or guardian. Details of the participating hospitals can be found in Supplementary Data 14.

The study design and analysis workflow are summarized in Fig. 1. We conducted analysis using data from the 35th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-35) study44. Detailed information regarding the study design, setting, and participants can be found in the Supplementary Information. Briefly, MARC-35 is a multicenter prospective cohort study enrolling infants (age < 1 year) hospitalized for bronchiolitis (severe bronchiolitis) during three consecutive bronchiolitis seasons, spanning from 2011 to 2014, across 17 medical centers located in 14 U.S. states (Supplementary Data 14). The diagnosis of bronchiolitis was made by attending physicians and defined as an acute respiratory illness characterized by a combination of rhinitis, cough, tachypnea, wheezing, crackles, or retraction, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics bronchiolitis guidelines45. Infants with preexisting heart or lung disease, immunodeficiency, immunosuppression, or a gestational age of <32 weeks were excluded. All enrolled participants received treatment at the discretion of their attending physicians.

A total of 921 infants were enrolled in the longitudinal MARC-35 cohort. For the current analysis, we limited our study population to participants who had data on DNAm in infant blood and at least one of the following outcomes: recurrent wheezing by age 3 years (n = 488, 170 cases, 318 non-cases) or asthma by age 6 years (n = 506, 112 cases, 394 non-cases) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Data and sample collection

Participant’s demographic data, including sex assigned at birth, age, and parent-reported race and ethnicity, as well as clinical data, including family, environmental, and medical history, and details of the acute illness, were collected via structured interview and medical chart reviews using standardized protocol4,45. Following the initial hospitalization at enrollment, trained study personnel initiated telephone interviews with parents/legal guardians at six-month intervals, complemented by medical record evaluations conducted by physicians. All collected data were reviewed at the Emergency Medicine Network (EMNet) Coordinating Center at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA, USA)4. Whole blood samples and nasopharyngeal airway samples were collected within 24 h of hospitalization by trained study personnel at each site following standardized protocols established in previous studies4,6. Details regarding the data and sample collection can be found in the Supplementary Information.

DNA methylation profiling and quality control

Epigenome-wide DNAm was profiled in the blood samples using the Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA). To ensure the quality of the DNAm data, we applied multiple sample-level and probe-level quality control (QC) filters (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2) following the established data preprocessing pipeline in the R/Bioconductor package minfi46. Details of DNA extraction and methylation QC are described in the Supplementary Information and our recent study6. Following the QC steps, we applied the single-sample normal-exponential using out-of-band probes (ssNoob) procedure to correct background and dye bias47. The current analysis was restricted to probes on chromosomes 1–22 and X.

Proteomics data measurement and quality control

Levels of circulating proteins were profiled in infant blood samples using the Olink multiplex platform (Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden). We added internal and external control samples and conducted data QC using the OlinkAnalyze R package48. The expression value of each protein was normalized to a unit on the log2 scale (Normalized Protein eXperssion, NPX value), which is proportional to the protein concentration. Details of proteomics profiling and QC are described in the Supplementary Information and our previous study49. The current analysis included 345 unique proteins measured on four Olink panels: Immune Response, Inflammation, Cardiovascular II, Cardiovascular III. These proteins are relevant to inflammation or immune functions and are considered most relevant to asthma development.

Outcomes

The clinical outcomes of interest are (i) recurrent wheezing by age 3 years and (ii) asthma by age 6 years. Specifically, recurrent wheezing was defined as having at least 2 corticosteroid-requiring exacerbations in 6 months or having at least 4 wheezing episodes in 1 year that last at least 1 day and affect sleep, according to the 2007 National Institutes of Health (NIH) asthma guidelines50. Asthma was defined based on a commonly used epidemiologic definition51: physician diagnosis of asthma by age 6 years with asthma medication use (e.g., inhaled corticosteroids) or asthma-related symptoms (e.g., wheezing, nocturnal cough) in the preceding year.

Identification of Rhinovirus infection

The frozen nasopharyngeal samples were first shipped to Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX, USA) for identification of rhinovirus viruses. Complementary DNA was generated using a rhinovirus-specific primer, and then a two-step real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed. The details of the primer and probe have been described elsewhere52.

Statistical analysis

Identifying differentially methylated regions (DMRs)

The analytical workflow is summarized in Fig. 1. We followed a two-step approach to identify DMRs for recurrent wheezing and asthma outcomes, respectively. For each outcome, we first examined the associations between the outcome and individual CpG sites using linear regression model and an additional likelihood ratio test with 2 degree-of-freedom (LRT-2df) that leveraged interaction effect by rhinovirus infection to increase power. In the linear regression model, we regressed the DNAm M-value (a logit-transformation of the %DNAm level) on the outcome (recurrent wheezing or asthma), adjusting for covariates and surrogate variables. We applied the empirical Bayes approach53 to linear regression to obtain robust estimates of standard error and p-value. The LRT-2df model assessed the overall association of DNAm with the outcome (H0: outcome main effect and outcome×rhinovirus infection interaction are both zero). In both the linear regression and the LRT-2df models, we adjusted the following covariates: participants’ sex, age at hospitalization, race/ethnicity, insurance type, maternal age, maternal asthma, and maternal smoking during pregnancy. Additionally, surrogate variables were estimated using the R package “SmartSVA”43 and were adjusted in both models. SmartSVA conducts robust reference-free adjustment of cell mixture and correction for technical batches in EWAS and can control the type I error well while preserving power43. In the second step, we applied the comb-p method54 to combine spatially correlated p-values and identify genomic regions showing consistent evidence for association with the respiratory outcome across multiple CpG sites (details see Supplementary Information). We provided the p-values at individual CpG sites from the linear regression and the LRT-2df models to the comb-p algorithm, respectively. DMRs were determined as those with a Šidák p < 0.01 (corrected for multiple testing) and at least 5 CpG sites. For DMRs identified by the LRT-2df model, we obtained the nominal p-value for the outcome × rhinovirus interaction at each CpG site.

Annotations for the DMRs were retrieved from the EPIC manifest file and UCSC genome browser (GRCh37/hg19). Evidence for chromatin accessibility was obtained by identifying the overlap between the DMRs and an ATAC-seq peak reference data measured in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a healthy donor55.

Cell-type specific effect through deconvolution

To examine if the associations at the DMRs were driven by specific cell types, we applied the CellDMC algorithm15, which uses a deconvolution approach to detect cell type specific differential methylation. We first inferred the proportions of seven blood cell types (B cells, NK cells, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, monocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils) using the DNAm data and an established reference-based algorithm56, and then estimated the DNAm differences by the outcome status that were specific to each blood cell type. These analyses were conducted using the R package “EpiDISH”57 for 474 CpG sites within the DMRs.

Cell-type specific enrichment in chromatin states

We further investigated the enrichment of the DMRs in specific chromatin states across 15 human peripheral blood cell populations using eFORGE 2.058. For each cell type, we tested the enrichment in 15 chromatin states inferred from histone modification marks and consolidated by the Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium16. In this analysis, we applied a 1-kb proximity filter to the CpG sites within the DMRs and adjusted for the background CpG sites included on the EPIC array (details see Supplementary Information). To address multiple testing, we employed a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold (p = 2.22 × 10−4).

Linking circulating proteins levels to the DNAm in infant blood

In a subset of our study participants with available proteomics data (n = 112), we used linear regression models to examine the association between DNAm and levels of circulating proteins, controlling the same covariates as above. This analysis was run for each CpG-protein pair from the 474 CpG sites (within DMRs) and 347 proteins. False discovery rate (FDR) was calculated using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Proteins correlated with any CpG site with an FDR < 0.05 were considered as DMR-correlated protein and included in downstream analyses.

For these proteins, we used adjusted linear regression to investigate whether the protein levels in infant blood were associated with subsequent recurrent wheezing (n = 107) and asthma (n = 109) outcomes within the MARC-35 cohort. In addition, we compared our findings to a recent publication17 from UKB to explore the relationship between these proteins and prevalent asthma in a larger population.

In addition, we focused on 19 CpG sites at the ST2 locus (chr2:102926502-10296819) on the EPIC array and evaluated the association of DNAm with ST2 protein level in infant blood (details see Supplementary Information).

Protein-proteins interaction (PPI) network and pathway enrichment analysis

We leveraged the publicly available database STRING18 to construct a PPI network for the DMR-correlated proteins based on the following types of existing evidence: (1) PPI from curated databases, (2) experimentally determined PPI, (3) Protein co-expression, and (4) Protein homology.

Furthermore, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment analysis for DMR-correlated proteins using R/Bioconductor package “STRINGdb”18. We calculated Benjamini-Hochberg FDR within each category. Given the Olink protein panel was designed for immune-related functions, we calculated permutation p-values for the enriched pathways to mitigate the impact of proteins selection on the pathway enrichment results. Details of the permutation test are described in Supplementary Information. We restricted pathways with 30–300 background proteins to eliminate pathways with either too specific or too broad functional annotations.

Mendelian randomization (MR) for DMR-correlated proteins

We conducted two-sample MR analysis to investigate the potential causal relationship of all DMR-correlated proteins on asthma59 and FEV1/FVC60 using GWAS summary statistics. Leveraging recent large-scale GWAS for plasma proteomics from deCODE (SomaScan platform)19 and UKB (Olink platform)17, we obtained a list of genome-wide significant cis- and trans-pQTLs as candidates for the genetic instruments. After clumping and selection of instruments (details see Supplementary Information), we applied four MR methods (MR-Egger, inverse variance weighted, weighed median, weighted mode) to proteins with at least 3 pQTLs using R package “TwoSampleMR”61. Benjamini-Hochberg FDR was calculated to correct for multiple testing. Additionally, we conducted two-sample MR analysis to further examine the potential causal relationship of ST2 protein level on other allergy-related traits (allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, serum IgE level)62,63,64,65,66.

All statistical tests included in the current study are two-sided.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw data generated in this study have been deposited to the NIH/NIAID ImmPort database under Accession ID SDY2306 The raw data is available under restricted access to ensure compliance with the informed consent forms of the MARC-35 study and the genomic data sharing plan. Requests for access can be made by directly contacting the corresponding author. The expected timeframe for response and the duration of access is subject to the data sharing policy of the NIH/NIAID ImmPort database. The EWAS summary statistics are available at http://lianglab.rc.fas.harvard.edu/AsthmaWheezingEWAS/. All other data are publicly available through the original studies’ website. The EPIC array manifest file is available at https://support.illumina.com/downloads/infinium-methylationepic-v1-0-product-files.html. Annotation information from UCSC genome browser is available at https://genome.ucsc.edu/. The ATAC-seq peak reference data in human PBMCs can be downloaded from https://www.10xgenomics.com/datasets/pbmc-from-a-healthy-donor-no-cell-sorting-10-k-1-standard-2-0-0. The chromatin states data from the NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Project is available at https://egg2.wustl.edu/roadmap/web_portal/index.html. The STRING protein-protein-interaction data is available at https://string-db.org/. The deCODE pQTLs GWAS summary statistics is available at https://www.decode.com/summarydata/. The UKB pQTLs GWAS summary statistics is available at https://metabolomips.org/ukbbpgwas/. The GWAS summary statistics for asthma, FEV1/FVC, and other outcomes can be downloaded from https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/ (accession numbers: GCST90014325, GCST007431, GCST90018795, GCST005038, GCST90038664, GCST90027161, GCST90027161).

Code availability

The DNA methylation data pre-processing was conducted using the R/Bioconductor package minfi v1.44.0 (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/minfi.html). The epigenome-wide linear regression models were implemented using the R package meffil v1.3.6 (https://github.com/perishky/meffil). The epigenome-wide likelihood ratio tests were conducted using the R package lmtest v0.9.40 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmtest/index.html). The cell type and batch control in EWAS was conducted by the R package SmartSVA v0.1.3 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SmartSVA/index.html). The region-based analyses were performed using comb-p v0.50.6 (https://github.com/brentp/combined-pvalues). The blood cell type deconvolution analysis was performed using the R/Bioconductor package EpiDISH v2.14.1 (https://github.com/sjczheng/EpiDISH/tree/master). The DMR chromate states enrichment analysis was performed using eFORGE v2.0 (https://eforge.altiusinstitute.org/). The proteomics data pre-processing was conducted using R package OlinkAnalyze v3.3.1 (https://github.com/Olink-Proteomics/OlinkRPackage). The protein GO pathway enrichment analysis was performed using R/Bioconductor package STRINGdb v2.10.1 (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/STRINGdb.html). The two-sample mendelian randomization was conducted using R package TwoSampleMR v0.5.10 (https://mrcieu.github.io/TwoSampleMR/).

References

Hasegawa, K., Dumas, O., Hartert, T. V. & Camargo, C. A. Advancing our understanding of infant bronchiolitis through phenotyping and endotyping: clinical and molecular approaches. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 10, 891–899 (2016).

Fujiogi, M. et al. Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States: 2000–2016. Pediatrics 144, e20192614 (2019).

Hasegawa, K., Mansbach, J. M. & Camargo, C. A. Infectious pathogens and bronchiolitis outcomes. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 12, 817–828 (2014).

Hasegawa, K. et al. Association of Rhinovirus C bronchiolitis and immunoglobulin E sensitization during infancy with development of recurrent wheeze. JAMA Pediatr. 173, 544–552 (2019).

Cavalli, G. & Heard, E. Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature 571, 489–499 (2019).

Zhu, Z. et al. Epigenome-wide association analysis of infant bronchiolitis severity: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Nat. Commun. 14, 5495 (2023).

Arathimos, R. et al. Epigenome-wide association study of asthma and wheeze in childhood and adolescence. Clin. Epigenetics 9, 112 (2017).

Reese, S. E. et al. Epigenome-wide meta-analysis of DNA methylation and childhood asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 143, 2062–2074 (2019).

Xu, C.-J. et al. DNA methylation in childhood asthma: an epigenome-wide meta-analysis. Lancet 379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30052-3 (2018).

Krusche, J., Basse, S. & Schaub, B. Role of early life immune regulation in asthma development. Semin. Immunopathol. 42, 29–42 (2020).

Lambrecht, B. N., Hammad, H. & Fahy, J. V. The cytokines of asthma. Immunity 50, 975–991 (2019).

Lukacs, N. W. Role of chemokines in the pathogenesis of asthma. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1, 108–116 (2001).

Zaghlool, S. B. et al. Epigenetics meets proteomics in an epigenome-wide association study with circulating blood plasma protein traits. Nat. Commun. 11, 15 (2020).

Myte, R., Sundkvist, A., Van Guelpen, B. & Harlid, S. Circulating levels of inflammatory markers and DNA methylation, an analysis of repeated samples from a population based cohort. Epigenetics 14, 649–659 (2019).

Zheng, S. C., Breeze, C. E., Beck, S. & Teschendorff, A. E. Identification of differentially methylated cell types in epigenome-wide association studies. Nat. Methods 15, 1059–1066 (2018).

Kundaje, A. et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 518, 317–330 (2015).

Sun, B. B. et al. Plasma proteomic associations with genetics and health in the UK Biobank. Nature 622, 329–338 (2023).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D605–D612 (2020).

Eldjarn, G. H. et al. Large-scale plasma proteomics comparisons through genetics and disease associations. Nature 622, 348–358 (2023).

Tenero, L., Piazza, M. & Piacentini, G. Recurrent wheezing in children. Transl. Pediatr. 5, 31–36 (2016).

Morales, E. et al. DNA hypomethylation at ALOX12 is associated with persistent wheezing in childhood. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 185, 937–943 (2012).

Zhu, Z. et al. Shared genetics of asthma and mental health disorders: a large-scale genome-wide cross-trait analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 54, 1901507 (2019).

Weathington, N. et al. BAL cell gene expression in severe asthma reveals mechanisms of severe disease and influences of medications. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 200, 837–856 (2019).

Zhu, Z. et al. Nasal airway microRNA profiling of infants with severe bronchiolitis and risk of childhood asthma: a multicentre prospective study. Eur. Respir. J. 62, 2300502 (2023).

Zhu Z. et al. Integrated nasopharyngeal airway metagenome and asthma genetic risk endotyping of severe bronchiolitis in infancy and risk of childhood asthma. Eur Respir J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01130-2024 (2024).

Yao, Y. et al. The emerging role of the piRNA/PIWI complex in respiratory tract diseases. Respir. Res. 24, 76 (2023).

Zou, G.-L. et al. The role of Nrf2/PIWIL2/purine metabolism axis in controlling radiation-induced lung fibrosis. Am. J. Cancer Res. 10, 2752–2767 (2020).

Corsello, T., Kudlicki, A. S., Liu, T. & Casola, A. Respiratory syncytial virus infection changes the piwi-interacting RNA content of airway epithelial cells. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 931354 (2022).

Sun, B. & Chen, L. Mapping genetic variants for nonsense-mediated mRNA decay regulation across human tissues. Genome Biol. 24, 164 (2023).

Asosingh, K. et al. Nascent endothelium initiates Th2 polarization of asthma. J. Immunol. 190, 3458–3465 (2013).

Reglero-Real, N., Pérez-Gutiérrez, L. & Nourshargh, S. Endothelial cell autophagy keeps neutrophil trafficking under control. Autophagy 17, 4509–4511 (2021).

Lacy, P. Mechanisms of degranulation in neutrophils. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2, 98 (2006).

Akgun, E. et al. Proteins associated with neutrophil degranulation are upregulated in nasopharyngeal swabs from SARS-CoV-2 patients. PLoS ONE 15, e0240012 (2020).

Rouleau, P. et al. the calcium-binding protein S100A12 induces neutrophil adhesion, migration, and release from bone marrow in mouse at concentrations similar to those found in human inflammatory arthritis. Clin. Immunol. 107, 46–54 (2003).

Burgess, S., Davies, N. M. & Thompson, S. G. Bias due to participant overlap in two-sample Mendelian randomization. Genet. Epidemiol. 40, 597–608 (2016).

Kakkar, R. & Lee, R. T. The IL-33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 827–840 (2008).

Riera-Martínez, L., Cànaves-Gómez, L., Iglesias, A., Martin-Medina, A. & Cosío, B. G. Te role of IL-33/ST2 in COPD and its future as an antibody therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 8702 (2023).

Folkersen, L. et al. Genomic and drug target evaluation of 90 cardiovascular proteins in 30,931 individuals. Nat. Metab. 2, 1135–1148 (2020).

Savenije, O. E. et al. Association of IL33-IL-1 receptor-like 1 (IL1RL1) pathway polymorphisms with wheezing phenotypes and asthma in childhood. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134, 170–177 (2014).

Portelli, M. A. et al. Phenotypic and functional translation of IL1RL1 locus polymorphisms in lung tissue and asthmatic airway epithelium. JCI Insight 5, e132446 (2020).

Dijk, F. N. et al. Genetic regulation of IL1RL1 methylation and IL1RL1-a protein levels in asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 51, 1701377 (2018).

Teschendorff, A. E. & Relton, C. L. Statistical and integrative system-level analysis of DNA methylation data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 129–147 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. Fast and robust adjustment of cell mixtures in epigenome-wide association studies with SmartSVA. BMC Genom. 18, 413 (2017).

Hasegawa, K. et al. Association of nasopharyngeal microbiota profiles with bronchiolitis severity in infants hospitalised for bronchiolitis. Eur. Respir. J. 48, 1329–1339 (2016).

Ralston, S. L. et al. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 134, e1474–e1502 (2014).

Aryee, M. J. et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics 30, 1363–1369 (2014).

Fortin, J. P., Triche, T. J. & Hansen, K. D. Preprocessing, normalization and integration of the Illumina HumanMethylationEPIC array with minfi. Bioinformatics 33, 558–560 (2017).

Nevola, K. et al. OlinkAnalyze: facilitate analysis of proteomic data from Olink. R package version 3.3.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=OlinkAnalyze (2023).

Ooka, T. et al. Proteomics endotyping of infants with severe bronchiolitis and risk of childhood asthma. Allergy 77, 3350–3361 (2022).

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120, S94–S138 (2007).

Raita, Y. et al. Nasopharyngeal metatranscriptome profiles of infants with bronchiolitis and risk of childhood asthma: a multicentre prospective study. Eur. Respir. J. 60, 2102293 (2022).

Lu, X. et al. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for comprehensive detection of human rhinoviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 533–539 (2008).

Smyth, G. K. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3, Article3 (2004).

Pedersen, B. S., Schwartz, D. A., Yang, I. V. & Kechris, K. J. Comb-p: software for combining, analyzing, grouping and correcting spatially correlated P-values. Bioinformatics 28, 2986–2988 (2012).

PBMC from a Healthy Donor - No Cell Sorting (10k). 10x Genomics https://www.10xgenomics.com/datasets/pbmc-from-a-healthy-donor-no-cell-sorting-10-k-1-standard-2-0-0.

Teschendorff, A. E., Breeze, C. E., Zheng, S. C. & Beck, S. A comparison of reference-based algorithms for correcting cell-type heterogeneity in Epigenome-Wide Association Studies. BMC Bioinforma. 18, 105 (2017).

Zheng, S. C. et al. EpiDISH web server: epigenetic dissection of intra-sample-heterogeneity with online GUI. Bioinformatics 36, 1950–1951 (2020).

Breeze, C. E. et al. eFORGE v2.0: updated analysis of cell type-specific signal in epigenomic data. Bioinformatics 35, 4767–4769 (2019).

Valette, K. et al. Prioritization of candidate causal genes for asthma in susceptibility loci derived from UK Biobank. Commun. Biol. 4, 1–15 (2021).

Shrine, N. et al. New genetic signals for lung function highlight pathways and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associations across multiple ancestries. Nat. Genet. 51, 481–493 (2019).

Hemani, G., Tilling, K. & Smith, G. D. Orienting the causal relationship between imprecisely measured traits using GWAS summary data. PLOS Genet. 13, e1007081 (2017).

Ferreira, M. A. et al. Shared genetic origin of asthma, hay fever and eczema elucidates allergic disease biology. Nat. Genet. 49, 1752–1757 (2017).

Dönertaş, H. M., Fabian, D. K., Fuentealba, M., Partridge, L. & Thornton, J. M. Common genetic associations between age-related diseases. Nat. Aging 1, 400–412 (2021).

Sliz, E. et al. Uniting biobank resources reveals novel genetic pathways modulating susceptibility for atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 149, 1105–1112.e9 (2022).

Scepanovic, P. et al. Human genetic variants and age are the strongest predictors of humoral immune responses to common pathogens and vaccines. Genome Med. 10, 59 (2018).

Sakaue, S. et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 53, 1415–1424 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD): R01 AI-148338 (L.L. and K.H.), K01 AI-153558 (Z.Z.), U01 AI-087881 (C.A.C.), R01 AI-114552 (C.A.C.), R01 AI-127507 (C.A.C.), R01 AI-134940 (K.H.), R01 AI-137091 (K.H.), and UG3/UH3 OD-023253 (C.A.C.); Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Emergency Medicine Fellowship/Eleanor and Miles Shore Faculty Development Awards Program (Z.Z.); and the Harvard University William F. Milton Fund (Z.Z.). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank the participants and researchers from the Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC) who significantly contributed or collected data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. conceptualized and designed the study, performed data quality control and statistical analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. Z.Z. critically reviewed and revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. C.A.C. conceptualized and designed the parent study, obtained funding, collected the data, supervised the conduct of parent study, critically reviewed and revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. J.A.E. performed data quality control, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. K.H. conceptualized and designed the study, obtained funding, supervised the conduct of study, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. L.L. conceptualized and designed the study, obtained funding, collected the data, supervised the conduct of study, critically reviewed and revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests. Z.Z. reports grants from National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. C.A.C. reports grants from National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. K.H. reports grants from National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study; grants from Novartis, outside the submitted work. L.L. reports grants from National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks John Holloway and Klaus Bønnelykke for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhu, Z., Camargo, C.A. et al. Epigenomic and proteomic analyses provide insights into early-life immune regulation and asthma development in infants. Nat Commun 16, 3556 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57288-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57288-6