Abstract

The unprecedented scale of genomic databases has revolutionized our ability to identify regions in the human genome intolerant to variation—regions often implicated in disease. However, these datasets remain constrained by limited ancestral diversity. Here, we analyze whole-exome sequencing data from 460,551 UK Biobank and 125,748 Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) participants across multiple ancestries to test several key intolerance metrics, including the Residual Variance Intolerance Score (RVIS), Missense Tolerance Ratio (MTR), and Loss-of-Function Observed/Expected ratio (LOF O/E). We demonstrate that increasing ancestral representation, rather than sample size alone, critically drives their performance. Scores trained on variation observed in African and Admixed American ancestral groups show higher resolution in detecting haploinsufficient and neurodevelopmental disease risk genes compared to scores trained on European ancestry groups. Most strikingly, MTR trained on 43,000 multi-ancestry exomes demonstrates greater predictive power than when trained on a nearly 10-fold larger dataset of 440,000 non-Finnish European exomes. We further find that European ancestry group-based scores are likely approaching saturation. These findings highlight the need for enhanced population representation in genomic resources to fully realize the potential of precision medicine and drug discovery. Ancestry group-specific scores are publicly available through an interactive portal: http://intolerance.public.cgr.astrazeneca.com/.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of population-scale sequencing datasets has enabled the identification of regions of the human genome that are intolerant to functional variation due to negative selection1,2,3,4,5. Broadly, intolerance scores provide a quantitative measure of the depletion of variants in a gene compared to a null expectation in the general population. We and others have developed intolerance metrics that quantify the intolerance of genes, genic sub-regions, and non-coding regions2,3,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. These scores have become a cornerstone in prioritizing genetic variants in diagnostic settings, discovering genes and genomic regions underlying human traits, and predicting drug targets13.

Gene-level intolerance metrics provide a valuable resource for studying the functional significance of human genes. For example, we previously introduced the Residual Variance Intolerance Score (RVIS), which uses standing variation in the human population to rank genes based on their tolerance to common functional variation (i.e., missense and protein-truncating variants)1. Other gene-level scores focus on more specific classes of mutations, such as LOF-FDR and LOEUF (loss-of-function intolerance) and missense Z (missense intolerance) (see Supplementary Table 1 for a glossary of abbreviations)4,5,14. While gene-level metrics have proven extremely useful, certain regions of a gene can be more intolerant than other regions within the same gene, motivating the development of intragenic intolerance metrics. One example is the sliding-window missense tolerance ratio (MTR), which identifies genic sub-regions that are intolerant to missense variation using a sliding window9.

As population-level sequencing datasets continue to expand in sample size, the genetic variants observed in these datasets also increase in number. Such an increase in the number of observed variants should, in theory, improve the performance of intolerance metrics. However, current datasets remain disproportionately enriched for individuals of Northern European ancestry. Given that genetic variants and their frequencies differ dramatically across different populations15, we reasoned that the underrepresentation of global ancestries in these datasets not only exacerbates health inequities16,17, but could also limit the resolution of genic intolerance metrics.

In this work, we explored the extent to which ancestral diversity impacts the performance of genic and sub-genic intolerance metrics. Using population-level datasets from the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) and the UK Biobank (UKB), we demonstrate that broad ancestral representation increases the performance of several intolerance metrics in predicting neurodevelopmental disease and haploinsufficient genes. Notably, RVIS and missense tolerance metrics derived from African ancestry cohorts outperformed those computed from predominantly European individuals. These findings underscore the importance of broadening global ancestry representation to achieve equitable genomic research, enhance target discovery, and deepen our understanding of human biology.

Results

gnomAD and UKB cohort characteristics

We leveraged large collections of exome sequence data from gnomAD (v2.1) and the UKB to measure the impact of ancestral diversity on genic and sub-genic intolerance metrics. We used previously existing ancestral group classifications for both these resources14,17. Briefly, these classifications were derived using Principal Component Analysis methods to identify clusters of genetic similarity, which were then labeled based on established reference panels (see Methods).

The gnomAD v2 dataset includes aggregated allele frequency data from 125,748 exomes, among which we analyzed ancestry group-specific allele frequencies from African (n = 8128), South Asian (n = 15,308), Latino (n = 17,296), East Asian (n = 9197), Ashkenazi Jewish (n = 5040), non-Finnish European (n = 56,885), and Finnish populations (n = 10,824). In the UKB, we analyzed exome data from 460,551 individuals. Of these, 437,812 (95.06%) participants were of non-Finnish European ancestry, 8701 (1.89%) were of African ancestry, 2671 (0.58%) were of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, 9217 (2.00%) were of South Asian ancestry, and 2150 (0.47%) were of East Asian ancestry.

As expected, the African ancestry cohorts (AFR) exhibited the most genetic diversity, relative to the current reference genome (hg38), followed by the Admixed American (AMR) and South Asian (SAS) cohorts. This difference was particularly apparent for common (MAF > 0.05%) functional variants (Tables 1, 2). For example, in gnomAD there was a 1.8-fold enrichment of common missense variants in the AFR cohort (n = 141,538 variants among 8,128 individuals) compared to only the NFE cohort (n = 79,200 variants in 56,885 individuals). Similarly, there was a roughly 1.6-fold enrichment of common PTVs in the AFR subset versus the NFE subset (Tables 1, 2). The Finnish European group had the fewest common missense variants and PTVs, in part attributable to the founding bottleneck event that occurred roughly 120 generations ago, which reduced the effective gene pool and thus set their genetic history apart from other European populations18,19.

At current sample sizes, it appears that we have saturated the number of common (MAF > 0.05%) functional variants observed in non-Finnish Europeans. To demonstrate this, we created three subsets of NFE UKB participants: one with 20,000 individuals, one with 43,000, and one with 440,000 individuals. The number of common variants was stable across these three cohorts (Table 2). However, the number of rare variants increased proportionally with sample size, apparent in the NFE subsets as well as the other major ancestral groups (Tables 1, 2). Over 50% of the newly added variants were singletons (Supplementary Fig. 1). Collectively, these results demonstrate that enhancing diversity, in addition to sample size, is critical for better representing standing variation in the global human population.

Deriving ancestry group-specific RVIS

Given the significant differences in the amount of functional variation observed between populations, we hypothesized that lack of genetic diversity could limit the resolution of intolerance metrics. We first investigated this by creating ancestry group-specific versions of RVIS (Supplementary Data 1, 2). RVIS regresses the total number of common missense and PTVs on the total number of protein-coding variants in a gene1. The score is then defined as the studentized residual for each gene, with a negative score indicating that a gene is more intolerant to functional variation.

The use of total number of variants on the x-axis in RVIS serves as an empirical proxy for that gene’s mutational burden. Here, given that the number of observed variants depends heavily on sample size, we replaced the x-axis with genic mutability estimated from trimer mutation rates (see Methods) (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). Genic mutability estimates capture the probability of genetic variants occurring within a specific gene, accounting for factors like sequence context, methylation, and gene length. Encouragingly, genic mutability and total number of variants observed per gene were strongly correlated, consistent with our observations in prior work4 (UKB RVIS: Pearson’s r = 0.93; gnomAD RVIS: Pearson’s r = 0.94) (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b).

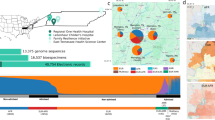

We next calculated ancestry group-specific versions of RVIS in both the gnomAD and UKB datasets, using mutability on the x-axis and common (MAF > 0.05%) functional variants on the y-axis (Fig. 1a, c). To assess differences in performance of these scores, we compared their ability to discriminate between genes that have been reported to be associated with severe disease and the rest of the exome. Specifically, we compiled five gene sets: monoallelic developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE) genes (n = 94), monoallelic developmental delay (DD) genes (n = 435), monoallelic autism spectrum disorder (ASD) genes (n = 190), haploinsufficient genes (n = 390), and mouse essential genes (n = 2454) (Supplementary Data 3).

a Scatter plot illustrating the regression of common (MAF > 0.05%) functional variants on mutability for seven different ancestry groups in gnomAD. The X- and Y-axes are capped to remove outlier genes. b AUC-ROC values of the ancestry group-specific RVIS in gnomAD for predicting five gene lists. c Regression lines of common (MAF > 0.05%) functional variants versus mutability for five different ancestry groups in the UKB. d AUC-ROC values of the ancestry group-specific RVIS in the UKB for predicting the following five gene lists. AFR African, AMR Admixed American, ASJ Ashkenazi Jewish, EAS East Asian, FIN Finnish, NFE non-Finnish European, SAS South Asian, DEE developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, DD developmental delay, ASD autism spectrum disorder.

Across all five gene sets, UKB- and gnomAD-derived RVIS scores that were trained on genetic variation data from the African ancestry cohort consistently achieved the highest area under the ROC curve (Fig. 1b, d). DeLong’s test demonstrated that RVISAFR AUCs were significantly higher than the RVISNFE AUCs for all gene sets excluding haploinsufficient genes (Supplementary Data 4, 5). As expected, RVISAMR and RVISSAS also generally outperformed RVISNFE. A sensitivity analysis demonstrated that this increased performance was robust to different MAF cutoffs for the y-axis (Supplementary Fig. 5). Although the differences in AUC were modest across all, broad genetic representation in population-scale sequencing databases is clearly important in enhancing the resolution of RVIS.

Notably, the AUCs were generally lower for haploinsufficient genes irrespective of ancestry. This is likely because the ClinGen haploinsufficient gene list includes genes associated with a broad spectrum of human disease severities, ranging from phenotypes like dermatitis—which is under relatively modest selective pressure—to those with more substantial health impacts, such as neurodevelopmental disorders. Consistent with this, the distributions of RVIS scores are more variable for haploinsufficient genes compared to neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) genes for each ancestry group (Supplementary Figs. 6, 7).

We next directly compared the score distributions of RVISAFR and RVISNFE for NDD genes (Supplementary Fig. 8). The percentile ranks of these scores were generally well-correlated (Pearson’s r range: 0.71–0.85, see Supplementary Fig. 8). However, there were notable outliers that appeared to have discordant intolerance patterns. For example, SHANK3, a well-established ASD gene, exhibited a much more intolerant RVISAFR score compared to RVISNFE (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results demonstrate how increased genetic diversity can refine estimates of intolerance.

MTR improves with increasing genetic diversity

Whereas RVIS relies on the observation of common variants to quantify intolerance, other metrics are computed based on the total number of variants observed in a gene—irrespective of allele frequency—compared to a null expectation. Since the total number of observed variants correlates with sample size, we used the UKB to create down-sampled datasets of equal size but with varying compositions of ancestral diversity. Specifically, we defined one cohort of 42,739 exomes (“Maximally Diverse (n = 43k)”), which included data from individuals of African (n = 8701), South Asian (n = 9217), East Asian (n = 2150), and Ashkenazi Jewish (n = 2671) ancestry, as well as 20,000 randomly sampled non-Finnish European samples (Table 3). As a comparator, we defined a separate cohort of 42,740 NFE individuals (“NFE (n = 43k)”). We also included two larger cohorts, including one with all 437,812 NFE samples (“NFE (n = 440k)”) and a dataset that included all 460,551 of the above samples (“Full Dataset (n = 460k)”). The “Maximally Diverse (n = 43k)” cohort harbored 3,185,006 missense variants and PTVs compared to 2,132,513 in the “NFE only (n = 43k)” cohort (Table 3).

We then constructed gene-level MTR scores using these four cohorts, as well as the ancestry group-specific cohorts (Supplementary Data 7)9. MTR is calculated by comparing the observed proportion of missense variants compared to an expected proportion given the sequence context of the gene (see Methods). Across all five gene sets, the “Maximally Diverse”-derived MTR scores achieved the best AUC (Fig. 2). Interestingly, this score also outperformed the “Full Dataset”-derived score. One possibility is that the overrepresentation of NFE samples in the full dataset dilutes the signal gained from more genetically diverse cohorts. Furthermore, despite the drastic difference in sample size between the down-sampled (n = 42,740) and entire (n = 437,812) NFE cohorts, the performance of gene-level MTR in these subsets were generally comparable (Supplementary Data 8).

AUC-ROC scores illustrating the ability of each gene-level MTR score to predict five different gene lists. Each score represents a version of the score trained on the pre-defined UKB cohorts. AFR African, ASJ Ashkenazi Jewish, EAS East Asian, SAS South Asian, NFE non-Finnish European, DEE developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, DD developmental delay, ASD autism spectrum disorder.

We previously demonstrated that certain genic subregions can be under differential selection to missense variation using a sliding window version of MTR7,9. We thus next calculated sliding window MTR for each UKB cohort, employing a 31-codon window (Methods). To compare the performance of these scores, we tested the ability of each to distinguish between ClinVar pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants and control variants. To define control variants, we included variants observed in either gnomAD or TOPMed but not the UKB (Fig. 3a, b). We then compared the performance of these scores to predict de novo variants observed in affected probands versus those observed in their unaffected siblings from denovo-db20. AUCs were generally lower for this comparison, as not all de novo variants are necessarily pathogenic. However, this comparison revealed a similar pattern as the ClinVar analysis (Fig. 3c).

a AUC-ROC scores reflecting each score’s ability to distinguish between ClinVar “pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic” variants and control variants from gnomAD. b Same as a, except control variants were derived from TOPMed. c Ability of each score to distinguish between de novo variants observed in probands versus unaffected siblings in denovo-db. Control variants from gnomAD are variants found in gnomAD but not in UKB. Control variants from TOPMed are variants found in TOPMed but not in UKB or gnomAD. ClinVar Pathogenic contains ClinVar variants annotated as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. The box plots show the median (centre line), first and third quartiles (box limits), and 1.5x the interquartile range above and below the third and first quartiles (upper and lower whiskers). AFR African, ASJ Ashkenazi Jewish, EAS East Asian, SAS South Asian, NFE non-Finnish European.

Across all three variant sets, the versions of MTR trained on data from the most diverse cohorts achieved the best performance (i.e., the “Maximally Diverse (n = 43k)” and the “Full Dataset (n = 460k)”). Strikingly, the performance of these two scores was nearly identical, even though the “Maximally Diverse (n = 43k)” cohort comprised of roughly 1/10th the sample size. The remaining scores seemed to show a greater dependence on sample size than the gene-level metrics. This is likely because the region of interest is smaller for this version of the score (31 codon window versus an entire gene). Exemplifying this, the entire non-Finnish European cohort (n = 437,812) outperformed each of the other individual ancestry groups for the three variant sets tested here.

Loss-of-function intolerance

Finally, we examined the effects of genetic diversity on the performance of LOF intolerance metrics. Specifically, we considered our previously described LOF Observed/Expected metric (LOF O/E) and the related LOF-FDR score4 (Supplementary Data 9, 10). The LOF O/E score evaluates the ratio of LOF variants against the expected ratio of LOF variants under neutrality. The LOF-FDR score employs a one-sided binomial exact test with Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate multiple-testing correction to compare the observed to expected values (Methods). Scores trained with the entire NFE cohort (n = 440k) and the complete dataset (n = 460k) consistently outperformed the scores trained using reduced non-Finnish European cohort (n = 42,740) and the maximally diverse cohort (n = 42,739) across all gene sets (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 9). Compared to the prior metrics, sample size generally appeared to be the most important determinant of performance of LOF scores (Supplementary Data 11, 12). The most plausible explanation for this observation is the relative scarcity of protein-truncating variants (PTVs) compared to missense and synonymous variants (Tables 1, 2). PTVs are inherently rarer due to stronger purifying selection against deleterious mutations that disrupt gene function. As a result, even in ancestrally diverse populations, the absolute number of PTVs remains low, and thus larger sample sizes increase the confidence of observed statistics.

AUC-ROC scores illustrating the ability of LOF O/E to predict five different gene lists. Each score represents a version of the score trained on the UKB cohorts composed of different ancestries. AFR African, ASJ Ashkenazi Jewish, EAS East Asian, SAS South Asian, NFE non-Finnish European, DEE developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, DD developmental delay, ASD autism spectrum disorder.

Discussion

Discerning intolerant regions of the human genome is crucial to prioritizing likely disease-causing mutations, facilitating the discovery of new risk genes, and enabling insights into human genome biology more broadly. Here, we performed an extensive study that evaluates the impact of ancestral diversity and sample size have on intolerance metrics using two of the largest population-level exome sequencing databases. Consistent with previous findings, we observed a higher prevalence of common functional variants in non-European ancestry groups compared to European populations. In turn, incorporating more diverse cohorts demonstrably improved the resolution of various intolerance metrics, which has also been previously observed in non-coding intolerance metrics10. These differences were most apparent in RVIS and missense-specific intolerance scores (gene-level MTR and sliding window MTR). In comparison to RVIS and MTR, LOF intolerance metrics seemed more dependent on sample size. This is likely because LOF observations are considerably more sparse than missense and synonymous variants, meaning larger samples are required to achieve meaningful differentiation between test units. Based on improved accuracies across several benchmarks, we recommend users to default to RVIS and missense-specific intolerance scores derived from the African ancestry group and LOF intolerance metric computed from the full dataset. Altogether, our results broadly underscore the importance of achieving broad ancestral representation in sequencing databases.

Our findings have broad implications beyond understanding intolerance to variation in protein coding genes. For example, the FDA’s recent guidance on Diversity Action Plans (2024) reinforces the importance of including underrepresented populations in clinical trials to improve the generalizability of study results. Our findings underscore this need by demonstrating that greater ancestral diversity in genetic studies improves intolerance metrics, which could lead to more equitable and effective precision medicine across populations. Secondly, increasing ancestral diversity in genetic datasets could have significant implications for drug discovery. A recent study demonstrated that genetically supported drug targets exhibit higher success rates in clinical trials21, further emphasizing the importance of incorporating diverse populations in the early stages of therapeutic development. Since the frequency of deleterious and protective alleles may vary across populations, broadening diversity in genomic datasets increases the community’s power to identify and de-risk novel targets to move forward in drug development pipelines. Our work also has implications for understanding the transferability of results across populations. In related work, we and others22,23,24 have demonstrated that polygenic risk score models trained on European populations often perform poorly when applied to non-European groups, underscoring the importance of diversity in genetic research. The development of intolerance metrics that are more generalizable across different populations could potentially improve the portability of models that combine rare alleles and polygenic risk scores to model disease risk.

Although we analyzed data from several ancestral groups, there still remains incomplete representation of many human populations. For example, the intolerance scores defined from AFR cohorts achieved the best performance, but we currently lack representation from majority of the African continent. In addition, the inclusion of diverse populations that have undergone strong demographic bottlenecks or high levels of consanguinity could also improve intolerance metrics25. Because there is an increased rate of homozygous LOFs in these populations, their increased representation would also enable the identification of genes intolerant to recessive variation, which has been notoriously difficult to assess with currently available data. It is also important to note that the human mutation spectrum varies across ancestries26, and the mutability estimates used here are not ancestry-specific. As sample sizes continue to grow and ancestral representation increases, we recommend reverting to the original RVIS method of using the total number of observed variants on the x-axis. Overall, our work adds to the growing evidence that increasing the ancestral diversity of human genome/exome sequencing datasets is imperative for genomic health equity.

Methods

Cohort

The UK Biobank has approval from the North-West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (11/NW/0382), and participants provided written informed consent.

Genetic ancestry groups

Genetic ancestry group is distinct from race and ethnicity as explained by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). While race and ethnicity are sociopolitical constructs based on perceived shared biological characteristics and culture, genetic ancestry refers to the specific paths through family trees where DNA is inherited from specific ancestors. Karczewski et al. describe the methodology gnomAD used to determine genetic ancestry group14. We used previously published labels for the UKB exomes17,27.

Splitting these exomes into geographic cohorts is beneficial in this study because genetic variants are observed with varying frequencies between genetic ancestry groups due to demographic histories, including bottleneck events. We want to underscore, however, that the genetic ancestry stratifications in both the UKB and gnomAD are artificially created and not naturally occurring. We recognize the concern behind genetic ancestry group annotations and their potential to exacerbate the illusion of natural ancestral populations as well as the association between geographic labels and socio-politically constructed concepts including race and ethnicity. Considering this and in accordance with recent guidelines from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), we emphasize that genetic ancestry exists on a spectrum and relates to the family tree where DNA is inherited from specific ancestors. Moreover, genetic ancestry groups are stratified by genetic similarity, and the geographic labels from this study are artificially created.

Estimating coverage-corrected gene size and filtering variants

We used the gnomAD public transcripts as our coding-sequence source data (gnomAD Predicted Constraint Metrics v2.1.1, GRCh38). The data provided a canonical transcript per gene, defined as the longest isoform. If there were multiple canonical transcripts for the same gene, we retained the transcript with the greatest number of observed variants. Additional predicted constraint metrics including observed and expected variants counts per gene, observed/expected ratio, and Z-scores of the observed counts relative to expected were also included in the data. Mutability of missense, synonymous, and LOF variants per gene were also provided. The mutability metrics were retrieved from the gnomAD metrics file, where the authors used a trinucleotide context model as described in the gnomAD publication14. The mutability of LOF variants provided by gnomAD is limited to single nucleotide variants. To calculate the mutability for frameshift variants, we multiplied this mutability rate by 1.255. The sum of these four mutability values was used as the mutability per gene. The UKB variants were annotated with SnpEF28, and we filtered for the canonical transcript in the gnomAD.

Synonymous variants were identified with the function “synonymous”. Missense variants were labeled with the functions “missense”, “in frame insertion”, and “in frame deletion”. Loss-of-function variants were annotated with the functions “frameshift variant”, “stop gained”, “start lost”, “splice acceptor variant”, “splice donor variant”, “stop gained and frameshift variant”, “splice donor variant and coding sequence variant and intron variant”, “splice donor variant and intron variant”, “stop gained and in frame insertion”, “frameshift variant and stop lost”, “frameshift variant and start lost”, “start lost and splice region variant”, “stop gained and protein altering variant”, “stop gained and frameshift variant and splice region variant”, “stop gained and in frame deletion”, and “frameshift variant and stop retained variant”.

Constructing RVIS

RVIS1 scores were calculated using a cohort of 125,748 exomes from the gnomAD (v2.1) and 460,551 exomes from the UKB. Seven sets of ancestry group-specific RVIS were computed from the gnomAD: AFR (n = 8128), SAS (n = 15,308), AMR (n = 17,296), EAS (n = 9197), ASJ (n = 5040), NFE (n = 56,885), and FIN (n = 10,824). Five sets of ancestry group-specific RVIS were derived from the UKB Biobank (UKB): EAS (n = 2150), SAS (n = 9217), ASJ (n = 2671), AFR (n = 8701), and NFE (n = 20k). The number of common functional variants per given gene were determined for each ancestry group. These common functional variants were defined as missense and loss-of-function variants with MAF values greater than 0.05%, which was a cutoff threshold validated by our sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Fig. 5). The number of common functional variants were then regressed against mutability, resulting in seven linear regression models for gnomAD and five models for the UKB. The studentized residuals from these models were computed as the ancestry group-specific RVIS.

Constructing gene-level MTR scores

We generated gene-level MTR scores using the four cohorts and the ancestry group-specific cohorts in the UKB. The formula for computing gene-level MTR was

which compares the ratio of observed fraction of missense variants relative to observed missense and synonymous variants against the expected fraction of missense variants. With the assumption that synonymous variants are evolutionarily neutral and free from selective pressures, the MTR computes the fraction of allowed missense mutations relative to the maximum possible proportion of missense variation in the absence of selective pressure. The gene-level MTR focuses on the cumulative intolerance of the whole gene.

LOF O/E and LOF-FDR

We generated LOF O/E and LOF-FDR scores using the four cohorts and the ancestry group-specific cohorts in the UKB4. Briefly, the expected rate is calculated by taking the mutation rate of LOFs (i.e., PTVs) and dividing that by the sum of mutation rates of all possible mutation effects in the gene, including synonymous, missense, and LOF variants. Mutability estimates were derived from the gnomAD v2.1 metrics file14. To account for frameshift variants, we multiplied the PTV mutability by 1.255.

To calculate LOF-FDR, we computed a one-sided binomial exact test using the number of LOF variants, total number of unique variants, and expected fraction of LOF variants under neutrality and applied Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate multiple-testing correction.

Benchmarking gene-level scores

To test cohort specific gene-level scores in determining disease-causing genes, we performed simple logistic regression models for RVIS, gene-level MTR, LOF O/E, and LOF-FDR (Supplementary Data 4, 5, 8, 11, 12). In these models, the gene-level metric was used as the predictor variable, while a binary variable distinguishing disease-causing genes from the rest of the HGNC genes served as the response variable. For each pairing of test set and gene-level score, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for identifying disease causing genes was computed. DeLong’s test was used to assess for significant difference in the predictive ability between models.

Five gene sets were used as test sets to evaluate performance of the cohort specific gene-level scores. These were monoallelic DEE genes, monoallelic developmental delay (DD) genes, monoallelic autism spectrum disorder (ASD) genes29, haploinsufficient genes30, and mouse essential genes31. The monoallelic ASD gene list was curated by selecting SFARI Tier 1 ASD genes (n = 207) and filtering genes with biallelic mechanism, leaving 190 total monoallelic ASD genes. The monoallelic DD gene list was determined by selecting genes with “Brain/Cognition” and “Definitive” labels from the Developmental Disorder Genotype-Phenotype Database (DD2GP) then filtering for monoallelic genes (n = 218) and combining these genes with 199 genes found to be significant from the Kaplanis et al, culminating in total of 435 genes for the DD monoallelic set32. The monoallelic DEE gene list was created by selecting for “DEE” phenotype genes from Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) and combining these with previously curated gene lists29,33,34,35,36,37. We provided additional information on curating monoallelic DEE, DD, and ASD gene lists in our previous study29.

Sliding window MTR variant-level benchmark

Sliding window MTR scores were calculated as described in Traynelis et al. and Vitsios et al. for every codon position of 18,823 canonical transcripts over a sliding window of 31 codons7,9. We employed variant-level data from nine different cohorts (of single or diverse ancestry groups) derived from the UK Biobank (UKB): EAS (n = 2150), SAS (n = 9217), ASJ (n = 2671), AFR (n = 8701), NFE (n = 20k), NFE (n = 43k), NFE (n = 440k), Maximally Diverse (n = 43k) and Full Dataset (n = 460k). To test MTR’s ability to discriminate pathogenic missense variants from benign, we composed three sets of benign variants and two sets of pathogenic variants. The benign sets we compiled comprise of: i) variants present in gnomAD (v2.1), but not present in UKB, ii) variants present in TOPMed, but not present in UKB or gnomAD (v2.1), and iii) de novo variants from denovo-db present in control individuals from the SSC or non-SSC samples20. As pathogenic variant sets, we used: (i) variants confidently annotated in ClinVar as “Pathogenic” or “Likely pathogenic”, or (ii) de novo variants from denovo-db present in affected individuals from the SSC or non-SSC samples.

To test MTR’s performance, as calculated across the different cohorts, in distinguishing pathogenic missense variants form benign, we used MTR as a measure of probability that a variant is benign: the higher the MTR score, the greater the probability. For each combination of test sets and MTR metrics, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for distinguishing pathogenic from benign variants was calculated. Due to the imbalance in the respective positive and negative test sets, we randomly down-sampled the larger one in each case to match the size of the other set of the pair. Finally, we repeated the down-sampling and calculated AUC scores across 10 iterations for each pair of pathogenic-benign variant sets to include enough data points and increase the robustness of the discrimination tasks.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The Gene-level intolerance scores generated in this study are included in supplementary data, and the sliding window MTR scores are publicly available on FigShare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26049661.v1)38. Scores are also browsable via our publicly available portal: http://intolerance.public.cgr.astrazeneca.com/. The UK Biobank whole-exome sequencing data are publicly available to registered researchers through the UKB data access protocol. Exomes can be found in the UKB showcase portal: https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/label.cgi?id=170. Additional information about registration for access to the data is available at http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/register-apply/. Data for this study were obtained under Resource Application Number 26041 and 65851. gnomAD v2.1.1 data are publicly available through the gnomAD website (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/data#v2). Gene lists are available through GitHub (https://github.com/alhanster/ancestral_diversity/tree/main/data/genelist); denovo-db v1.6.1 data is publicly available through https://denovo-db.gs.washington.edu/denovo-db/; and TOPMed freeze 5 data are publicly available through https://bravo.sph.umich.edu.

Code availability

Code for generating gene-level scores is available at: https://github.com/alhanster/ancestral_diversity and the code for generating sliding-window MTR scores is available at: https://github.com/astrazeneca-cgr-publications/OncMTR/tree/mtr-ancestry-specific. Code is also available via Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/14901599)39.

References

Petrovski, S., Wang, Q., Heinzen, E. L., Allen, A. S. & Goldstein, D. B. Genic intolerance to functional variation and the interpretation of personal genomes. PLOS Genet. 9, e1003709 (2013).

Dhindsa, R. S., Copeland, B. R., Mustoe, A. M. & Goldstein, D. B. Natural selection shapes codon usage in the human genome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 107, 83–95 (2020).

Gussow, A. B. et al. Orion: detecting regions of the human non-coding genome that are intolerant to variation using population genetics. PLOS ONE 12, e0181604 (2017).

Petrovski, S. et al. The intolerance of regulatory sequence to genetic variation predicts gene dosage sensitivity. PLOS Genet. 11, e1005492 (2015).

Samocha, K. E. et al. A framework for the interpretation of de novo mutation in human disease. Nat. Genet. 46, 944–950 (2014).

Vitsios, D., Dhindsa, R. S., Middleton, L., Gussow, A. B. & Petrovski, S. Prioritizing non-coding regions based on human genomic constraint and sequence context with deep learning. Nat. Commun. 12, 1504 (2021).

Dimitrios Vitsios et al. Cancer-driving mutations are enriched in genic regions intolerant to germline variation. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo6371 https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abo6371 (2022).

di Iulio, J. et al. The human noncoding genome defined by genetic diversity. Nat. Genet. 50, 333–337 (2018).

Traynelis, J. et al. Optimizing genomic medicine in epilepsy through a gene-customized approach to missense variant interpretation. Genome Res. 27, 1715–1729 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature 625, 92–100 (2024).

Halldorsson, B. V. et al. The sequences of 150,119 genomes in the UK Biobank. Nature 607, 732–740 (2022).

Havrilla, J. M., Pedersen, B. S., Layer, R. M. & Quinlan, A. R. A map of constrained coding regions in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 51, 88–95 (2019).

Nelson, M. R. et al. The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nat. Genet. 47, 856–860 (2015).

Karczewski, K. J. et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 581, 434–443 (2020).

Auton, A. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

Petrovski, S. & Goldstein, D. B. Unequal representation of genetic variation across ancestry groups creates healthcare inequality in the application of precision medicine. Genome Biol. 17, 157 (2016).

Wang, Q. et al. Rare variant contribution to human disease in 281,104 UK Biobank exomes. Nature 1–9 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03855-y (2021).

Jakkula, E. et al. The genome-wide patterns of variation expose significant substructure in a founder population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 787–794 (2008).

Xue, Y. et al. Enrichment of low-frequency functional variants revealed by whole-genome sequencing of multiple isolated European populations. Nat. Commun. 8, 15927 (2017).

Turner, T. N. et al. denovo-db: a compendium of human de novo variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D804–D811 (2017).

Minikel, E. V., Painter, J. L., Dong, C. C. & Nelson, M. R. Refining the impact of genetic evidence on clinical success. Nature 629, 624–629 (2024).

Moreno-Grau, S. et al. Polygenic risk score portability for common diseases across genetically diverse populations. Hum. Genom. 18, 93 (2024).

Paruchuri, K. et al. Using sex‐specific polygenic risk to prognosticate coronary artery disease in women. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e034946 (2024).

Koyama, S. et al. Decoding genetics, ancestry, and geospatial context for precision health. 2023.10.24.23297096 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.24.23297096 (2023).

Saleheen, D. et al. Human knockouts and phenotypic analysis in a cohort with a high rate of consanguinity. Nature 544, 235–239 (2017).

Harris, K. & Pritchard, J. K. Rapid evolution of the human mutation spectrum. eLife 6, e24284 (2017).

Dhindsa, R. S. et al. Rare variant associations with plasma protein levels in the UK Biobank. Nature 622, 339–347 (2023).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80–92 (2012).

Dhindsa, R. S. et al. Genome-wide prediction of dominant and recessive neurodevelopmental disorder-associated genes. Am J Hum Genet. 112, 693–708 (2025).

Rehm, H. L. et al. ClinGen–the clinical genome resource. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2235–2242 (2015).

Baldarelli, R. M. et al. Mouse genome informatics: an integrated knowledgebase system for the laboratory mouse. Genetics 227, iyae031 (2024).

Kaplanis, J. et al. Evidence for 28 genetic disorders discovered by combining healthcare and research data. Nature 586, 757–762 (2020).

Feng, Y.-C. A. et al. Ultra-rare genetic variation in the epilepsies: a whole-exome sequencing study of 17,606 individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 105, 267–282 (2019).

Dhindsa, R. S., Lowenstein, D. H. & Goldstein, D. B. Molecular architecture and neurobiology of the epilepsies. in Genomics, Circuits, and Pathways in Clinical Neuropsychiatry (eds. Lehner, T., Miller, B. L. & State, M. W.) 601–617 (Academic Press, San Diego, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800105-9.00037-8.

Dugger, S. A. et al. Neurodevelopmental deficits and cell-type-specific transcriptomic perturbations in a mouse model of HNRNPU haploinsufficiency. PLOS Genet. 19, e1010952 (2023).

Motelow, J. E. et al. Sub-genic intolerance, ClinVar, and the epilepsies: a whole-exome sequencing study of 29,165 individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 965–982 (2021).

Dhindsa, R. S., Zoghbi, A. W., Krizay, D. K., Vasavda, C. & Goldstein, D. B. A transcriptome-based drug discovery paradigm for neurodevelopmental disorders. Ann. Neurol. 89, 199–211 (2021).

Dhindsa, R. S. Ancestry-specific MTR scores. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26049661.v1 (2025).

Han, A. & Ravanmehr, V. alhanster/ancestral_diversity: v1.0.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14901599 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in the UK Biobank and gnomAD for their contributions to research (UKB Resource Application Numbers 26041 and 65851). We extend our gratitude to the AstraZeneca Centre for Genomics Research Analytics and Informatics team for processing and analysis of sequencing data. R.S.D. is supported by a Longevity Impetus Grant from Norn Group, Hevolution Foundation, and Rosenkranz Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S.D. and S.P. designed the study. A.L.H., D.M., D.V., and R.S.D. performed analyses and statistical interpretation. Q.W. and F.H. performed bioinformatics processing. A.L.H., C.F.S., D.V., J.C.B., D.M., and R.S.D. performed data visualization. D.M. and D.V. developed the web portal. A.L.H., C.F.S., and R.S.D. wrote the manuscript. A.L.H., C.F.S., D.M., J.C.B., V.R., F.H., E.V.G., N.K., C.D.B., Q.W., S.P., D.V., and R.S.D. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.M., F.H., Q.W., S.P., and D.V. are current employees and/or stockholders of AstraZeneca. R.S.D. is a paid consultant of AstraZeneca. N.K. and C.D.B. are employees of Galatea Bio. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiaolei Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, A.L., Sands, C.F., Matelska, D. et al. Diverse ancestral representation improves genetic intolerance metrics. Nat Commun 16, 2648 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57885-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57885-5