Abstract

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), a common disorder in diabetes, is associated with severe microenvironment imbalance due to immunometabolic stress. However, the underlying mechanistic drivers remain unclear. Here, we generate a single-cell atlas of human peripheral nerves and identify cell-specific transcriptional changes in DPN as well as aberrant amplification of mast cells. Using streptozotocin-induced mouse diabetes models, we further find that glucose uptake mediated by GLUT3 in high-glucose (HG) diabetic milieu upregulates ERK1/2 phosphorylation in mouse mast cells. Sustained HG stimulation also induces aberrant mTOR hyperactivity, resulting in endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial oxidative stress, thereby impairing mitochondrial functions of mast cells. Dysregulated mast cells then degranulate and release histamine, tryptase and inflammatory factors into neural microenvironment to cause neuropathy in diabetic mice. Lastly, mice with mast cell deficiency are protected from the immune imbalance in nerves and progression of neuropathy. Our findings thus implicate dysregulated activation of mast cells as a potential driver in the progression of DPN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) is a major complication in diabetic patients, as more than 60% of them are expected to develop DPN within their lifetime1. DPN significantly impairs quality of life, renders prolonged hospitalization time, and eventually leads to lower extremity amputation2,3. The initial pathological changes of DPN occur at the level of the unmyelinated C fibers, and as the disease course progresses, demyelination and axonal degeneration of myelinated fibers ensue4. Distinct from acute nerve injuries, the pathogenesis of DPN can be viewed as a state of chronic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction, which initiates a tissue-level insult against the peripheral nerve axons supported by glia4,5,6. Upregulation of proteins involved in inflammation and aberrant metabolic processes has been reported in nerve biopsies from DPN patients7. However, few studies have dissected the cell differences within nerve tissues between DPN patients and non-diabetic healthy controls. In this context, little is known about the involvement of different cell types, including the minority cell types, in the pathogenesis of DPN. Although specific anticonvulsants and antidepressants have been mainly used for management in DPN patients, the treatment of DPN lacks effective and disease-modifying therapies4. Understanding the cellular drivers of DPN will help develop cell-specific therapeutics, thus targeting the main drivers of poor outcomes. Given the multitude of cell types affected in DPN, there is a pressing need to understand cell-specific molecular and genomic mechanisms underlying DPN.

Neuronal microenvironment imbalance, a major characteristic of DPN, causes successive damage in neural structure and function. Diabetes-associated metabolic dysfunctions, including hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance, lead to oxidative stress and inflammation in DPN8. Increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and oxidative stress in diabetic tissue contribute to ongoing mitochondrial damage and insufficient energy production in resident cells9. Low-grade inflammation accompanied by increased immune cell infiltration characterizes a pivotal aspect of DPN pathology8,10. Metabolic imbalance within the environment can drive the phenotypic switch of immune cells, and thus produce a “metabolically-activated” phenotype11. In response to metabolic insults of DPN, immune cells in nerve tissues produce a cascade of cytokines and chemokines, including proinflammatory interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-ɑ (TNF-ɑ)4,6. Moreover, activated immune cells adapt their metabolic profiles, shifting from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, to support robust energy demands11,12. This switch in metabolic profile of immune cells leads to the accumulation of metabolic intermediates13,14. These proinflammatory factors and metabolic intermediates further cause successive and irreversible damage to axons and other supporting cells in peripheral nerves. However, present researches on the neuro-immune crosstalk and nerve injuries mainly focus on macrophages15. Relatively few studies have reported how other immune cells affect the homeostasis of the nerve microenvironment. In search of more effective therapeutics in the future without causing non-specific toxicity, it becomes paramount to understand the cell-specific mechanism underlying DPN pathogenesis.

In this study, we first demonstrate that tibial nerve tissues from DPN patients contain more mast cells than those from patients with traumatic limb amputation (TLA patients). Further experiments in diabetic mice confirm that genetic depletion of mast cells attenuates neuroinflammation and neurological deficits following streptozotocin (STZ) injection. In vitro studies establish that a high glucose (HG) environment confers a ‘metabolically activated’ phenotype on mast cells by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2)-mTOR cascades, leading to increased expression of proteases and proinflammatory mediators. Collectively, our data present precedent mechanistic insights into mast cell activities that drive the progression of DPN, and thus provide novel targets for treating DPN.

Results

Cellular heterogeneity in human tibial nerves

We hypothesize that peripheral nerve tissues from DPN patients are characterized by unique molecular signaling and cellular modifications. To determine DPN-related molecular and cellular signatures, we performed 10x Genomics single-cell sequencing on the tibial nerves from 4 DPN and 3 TLA patients (Fig. 1a, b). We obtained a total of 35,137 high-quality single cells from DPN nerve samples and 26,114 cells from TLA nerve samples. Transcriptional analysis revealed distinct gene expression profiles between DPN and TLA nerve samples (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Noteworthy, gene enrichments of DPN samples were significantly increased in gene ontology (GO) terms related to inflammatory response, ERK1/2 related pathway, and leukocyte chemotaxis compared with those of TLA samples (Fig. 1d, e). To determine the identities of these clusters, we overlaid cells in the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot with well-characterized marker genes. The relative levels of expression were shown as a color gradient. This approach identified Schwann cells expressing S100B, PLP1 and CDH19; endothelial cells expressing VWF, PECAM1 and JAM2; mast cells expressing KIT and TPSAB1; B cells expressing MS4A1 and CD79A; T cells expressing CD3D, SKAP1, THEMIS; natural killer (NK) cells expressing NKG7, KLRC1 and KLRD1; neutrophil expressing CSF3R, CXCR1 and CXCR2; fibroblasts expressing sFRP4 and COL1A1; smooth muscle cells/pericytes expressing TAGLN, ACTA2 and MYH11; and macrophages/monocytes expressing CD68 and LYZ. Initial analysis of single-cell sequencing data identified a marked increase of mast cells in the nerve tissue of DPN in comparison with their TLA counterparts (Fig. 1f, g). We found similar proportions for Schwann cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, NK cells, and macrophages between the two groups (Fig. 1f, g). We then examined the expression level of mast cell marker genes. These markers included those commonly-expressed genes in mast cells (e.g., KIT, CMA, TPSAB1, MS4A2, CPA3). As shown in UMAP plots, these markers were expressed in nerve tissues of DPN patients at abundant levels (Fig. 1h, i). Consistent with single-cell sequencing analysis, our quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) data confirmed that nerve tissues of DPN patients expressed higher levels of mast cell genes compared with their TLA counterparts (Fig. 1j).

Samples were collected from the tibial nerves of DPN and neurotrauma patients (TLA control), respectively. a, b UMAP plot of nerve resident cells sorted from the tibial nerves of 4 DPN and 3 TLA patients. DPN, diabetic neuropathy; TLA, traumatic limb amputation. (c) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between DPN and TLA samples. d, e Top-ranked GO pathways of the enriched DEGs between DPN and TLA samples. f, g UMAP visualizations of all cell clusters from tibial nerves of DPN patients (f) and TLA patients (g), identified by colors and associated numbers. h, i Gene expression of KIT, CMA1, TPSAB1, MS4A2, and CPA3 in nerve tissues from DPN (h) and TLA (i) displayed as UMAP plots. CMA1, chymase; TPSAB1, tryptase; CPA3, carboxypeptidase A3. j The qRT-PCR experiments further confirmed that expressions of mast cell-related marker genes, including KIT, CMA1, TPSAB1, MS4A2, and CPA3, significantly increased in DPN nerve tissues compared with TLA control. N = 6 patients in each PCR group. In panel (j), the ‘black dashed line’ symbol represents the median value, and the upper and lower lines of the violin plots represent the 75% and 25% quartiles, respectively. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests.

Mast cells contributed to the pathogenesis of DPN

The pathogenesis of DPN is a complicated process that ultimately leads to peripheral nerve degeneration and limb dysfunction. DPN-induced Schwann cell degeneration and peripheral demyelination may be initiating factors that further lead to neuronal damage16. Given that nerves from DPN patients contained more mast cells than from their TLA counterparts, we hypothesize that mast cells may play a role in the progression of DPN formation. To dissect cell-type-specific mechanisms, we first checked the myelin structure in biopsy samples of tibial nerves from both DPN and TLA patients. Haematoxylin-eosin (HE) and toluidine blue (TB) staining showed that the axon density in DPN patients has robustly decreased, compared with that in TLA patients (Fig. 2a, e). Moreover, transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis witnessed more degenerated axons without myelin wrapping in the nerve sections of DPN patients (Fig. 2b, f). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining also demonstrated that neurofilament 200 (NF200), an axon marker, has lower expression in DPN nerves than that in TLA nerves (Fig. 2c, g). Interestingly, we discovered that the prevalence of myeloid leukocytes (CD45) and mast cells (tryptase) in nerve tissues robustly increased along with the nerve degenerative changes (Fig. 2d, h, i).

a HE and TB staining were performed on patient nerve transections to reveal the neural structure. HE, hematoxylin-eosin; TB, toluidine blue. b Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of transverse nerve sections from TLA and DPN patients. c IHC staining of NF200 was performed on the transverse and longitudinal sections of patient nerves to show the neural structure better. IHC, immunohistochemistry. d Tibial nerve tissue of DPN and TLA patients immunostained for TPSAB1 (green) and CD45 (red). e Quantification of the myelinated axon density based on TB staining in DPN and TLA nerve transections. N = 10 patients in the TLA group and N = 7 patients in the DPN group. f Quantification of demyelinated axons based on TEM analysis. N = 10 patients in the TLA group and N = 7 patients in the DPN group. g Quantification of the neurofilament 200 (NF200) immunostaining area in DPN and TLA nerve transections. N = 10 patients in the TLA group and N = 7 patients in the DPN group. h, i Quantification of CD45 and TPSAB1 expression in nerve tissue sections. N = 10 patients in the TLA group and N = 7 patients in the DPN group. j Schematic diagram of DPN induction process via intraperitoneal STZ injection. STZ, streptozotocin. Panel (j) was created in BioRender. Kong, L. (2025) https://BioRender.com/hk360ua. k Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) of DPN and control mice, based on electrophysiological test. N = 6 mice in each group. l Representative images of murine sciatic nerves co-immunostained by NF200 (green) and S100β (red). m, n Quantification of the percentage of S100β and NF200 staining area. N = 6 mice in each group. o TEM images of transverse nerve sections from DPN and control mice. p, q Quantification of intact myelin sheath and demyelinated axon density in murine sciatic nerves. N = 6 mice in each group. All data were expressed as mean ± SD in Fig. 2. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests in figure (e–i) and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis in figure (k, m, n, p, and q).

To investigate whether increased mast cells account for the demyelination and degeneration in DPN nerves, we established a murine model of DPN using KitW-sh/W-sh mice, which have no mature mast cells because of the inversion mutation of the c-Kit promoter region (Fig. 2j). We performed a single-dose STZ injection to induce diabetes in mice. At 1 and 2 weeks post-STZ injection, blood glucose of the treated mice were measured. In WT mice, non-fasting blood glucose (NFBG) started to rise by 1 week after STZ treatment and reached a mean of 31.1 mmol/L at 2 weeks post-injection (Supplementary Fig. 2a). We found that mast cell-deficient mice had significantly better glucose tolerance than WT mice. Moreover, upon STZ injection, NFBG levels in mast cell-deficient mice increased similarly to that of WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Mice with NFBG exceeding 25 mmol/L at 2 weeks were allowed for the following experiments. We kept monitoring the NFBG of these mice until the end of the animal experiments.

We then examined the nerve conducting velocity (NCV) in diabetic mice. Decreased NCVs were observed in STZ-treated diabetic mice but not in the saline-treated mice (Fig. 2k). Of note, KitW-sh/W-sh mice showed significantly faster NCVs compared to their littermates (Fig. 2k), revealing the alleviated neural damage. We next collected the sciatic nerves at 24 weeks after intraperitoneal STZ injection for histological and TEM analysis. Murine nerve transection samples were chosen from the branching sites of sciatic nerves as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2b, to ensure the least bias in tissue density. The quantification of nerve transection images was based on the regions of interest (ROIs), which were selected within nerve bundles wrapped by perineurium (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Significantly, S100β and NF200 expression were higher in mast cell-deficient DPN mice than WT DPN mice, indicating genetic clearance of mast cells improved the axon density and Schwann cell numbers in DPN nerves (Fig. 2l–n), TEM analysis further witnessed more myelinated axons in nerve tissues harvested from diabetic KitW-sh/W-sh mice than those in diabetic WT mice (Fig. 2o–q). These findings highlighted the pathological role of mast cells in axon degeneration and demyelination.

Mast cell deficiency protected against DPN-induced neuroinflammation

Single-cell sequencing analysis demonstrated increased inflammatory responses in DPN nerves, which could further degenerate nerve structure and remodel the microenvironment. Thus, identifying mechanisms responsible for increased inflammation in the nerve microenvironment is important for understanding DPN development. Mast cells infiltrate diabetic nerve tissues, where they secrete proteins that remodel the microenvironment and initiate neuroinflammation. Here, we discovered that in human patients, both DPN and acutely-injured nerves were infiltrated with macrophages, T cells, and NK cells (Fig. 3a, b). As manifested by immunofluorescence analysis, acutely-injured tibial nerves were infiltrated with more neutrophils than DPN nerves, indicating posttraumatic defensive responses in nerve tissue. DPN nerves were infiltrated with more macrophages than TLA nerves. Moreover, we found higher levels of IL-1β and TNF-ɑ in DPN nerves (Fig. 3c–e), indicating a state of long-term chronic inflammation in DPN nerves. We then figured out the inflammatory state in KitW-sh/W-sh mice. We noticed that mast cell deficiency reduced the infiltration of myeloid leukocytes in nerves (Fig. 3f, g). In addition, mast cell genetic clearance decreased the level of IL-1β and TNF-ɑ in DPN nerves (Fig. 3h, i). Our findings indicated that mast cell deficiency protected against diabetes-induced neuroinflammation in mice.

a Distributions of NK cells, T cells, macrophages, and neutrophils in tibial nerves of DPN and TLA patients. NK, natural killer. b Quantification of immune cell infiltration in DPN and TLA nerve transections. N = 10 patients in the TLA group and N = 7 patients in the DPN group. c, d Quantification of TNFA and IL1B expressions in DPN and TLA nerves, based on qRT-PCR experiments. N = 6 patients in each PCR group. e Gene expression of TNF-ɑ and IL-1β in tibial nerves of DPN and TLA patients displayed as UMAP plots. TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin. f, g Leukocyte infiltration in murine DPN nerves, and related quantification. N = 6 mice in each group. h The TNF-ɑ and IL-1β levels in sciatic nerves of DPN mice, based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis. N = 6 mice in each group. i Double immunostaining of TNF-ɑ (red) and IL-1β (green) on longitudinal nerve sections of DPN mice. In panels (c, d), the ‘black dashed line’ symbol represents the median value, and the upper and lower lines of the violin plots represent the 75% and 25% quartiles, respectively. Data in panels (b, f, h) were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc analysis (b, h) and two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests (c, d, f).

Mast cells degranulated in response to HG exposure

To understand mast cell heterogeneity at the transcriptional level, we reanalyzed mast cell sequencing data and found that mast cells were categorized into 7 heterogeneous subclusters. The signature genes of each subcluster were listed as a heatmap (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Based on the subclustering outcome, we discovered that clusters 6 and 7 represented distinct clusters with a unique transcriptional profile, which only emerged in DPN nerves (Fig. 4a, b). Cluster 6 was marked by HMGB1 and HMGB2, and cluster 7 was marked by CCL5 and IL32. To understand the biological functions of the mast cells in DPN, we performed GO pathway analysis of the coregulated genes in mast cells. GO pathways indicating leukocyte activities, mast cell degranulation, prostaglandin metabolism and oxidative stress were significantly enriched, suggesting an immunomodulatory function for these mast cells during DPN progression (Fig. 4c). KEGG enrichment analysis further indicated that DPN mast cells were significantly enriched in mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MAPK1) signaling (Fig. 4d).

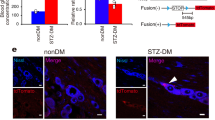

a Subclustering among the mast cell population by UMAP plots revealed 7 subpopulations. b The proportion of each subcluster in mast cell populations. c Top-ranked GO pathways of the enriched genes in DPN mast cells. d KEGG pathways enriched in DPN mast cells. e Schematic diagram of the establishment of in vitro HG environment. Panel (e) was created in BioRender. Kong, L. (2025) https://BioRender.com/1yvzy9d. f Representative immunofluorescence images of mast cell degranulation visualized by avidin (red) staining. g–i Double immunostaining of avidin (red) and CD63 (green) on mast cells and related quantification. N = 6 per group. j TEM images revealed the degranulating phenomenon in mast cells under high glucose (HG) stimulation. k–m Double immunostaining of TPSAB1 (red) and HDC (green) on mast cells and related quantification. HDC, histidine decarboxylase. N = 6 per group. (n–p) Double immunostaining of TNF-ɑ (red) and IL-1β (green) in mast cells and related quantification. N = 6 per group. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests.

Mast cells are bone marrow-derived tissue-dwelling cells that respond to various environmental stimuli by producing a plethora of protease and inflammatory mediators, including eicosanoids, histamine, and cytokines17. Peritoneal fluid-derived mast cells and bone marrow-derived mast cells are commonly used in in vitro studies to partially phenocopy the tissue-resident mast cells in vivo18. Therefore, we cultured bone marrow-derived mast cells in HG medium to recapitulate the activities of mast cells in response to hyperglycemia in vivo (Fig. 4e). We observed an evident degranulating phenomenon after 48 h of culture in HG medium (Fig. 4f, j), suggesting HG exposure as a potential trigger for mast cell activation. Avidin is used as a biomarker for mast cells, and CD63 is expressed on the surface of mast cells upon activation. We found that the HG environment significantly enhanced the granularity and activation of mast cells (Fig. 4g, i). Histamine is a type of bioactive monoamine synthesized in mast cells via histidine decarboxylase (HDC) induction. Consistently, we found that the expression levels of tryptase and HDC were enhanced in mast cells upon HG stimulation (Fig. 4k–m). The expression levels of inflammatory factors, including TNF-ɑ and IL-1β, were also significantly increased in HG-treated mast cells (Fig. 4n–p).

Mast cell degranulation induced cytotoxicity in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons

Having confirmed that HG milieu primed mast cells for cytotoxic attack by increasing the granularity and the release of pre-stored granules, we next examined the effects of HG-primed mast cells on neurons. DRGs can transduce somatosensory stimuli in peripheral nerves and reprogram their transcriptional identity to initiate axon regrowth after nerve injuries19. We next investigated the molecular changes in DRGs provoked by mast cells in DPN. First, we compared the percentage of injured DRG neurons in WT and KitW-sh/W-sh mice. Histological analysis by toluidine blue (TB) staining showed no evident difference in DRGs between WT and KitW-sh/W-sh mice (Fig. 5a). ATF3, a transcriptional factor induced by axon injury, drives transcriptional reprogramming of DRG neurons19. Detection of ATF3+ neurons in DRGs revealed significantly decreased injured DRG neurons in KitW-sh/W-sh mice (Fig. 5b, d). In the progression of DPN, myeloid cells migrate and fuse with DRG neurons, leading to neuronal dysfunction and apoptosis20. Along with the alleviation of injured state in DRG neurons, mast cell deletion inhibited the fusion of myeloid cells and neurons in DRGs (Fig. 5c, e). To determine the neuronal responses exerted by mast cells in different environments, DRG neurons were cocultured directly or indirectly with mast cells in both normal and HG culture medium (Fig. 5f). DRG neuronal monoculture was set as control. After 4 days of in vitro HG culture, DRG neurons were highly susceptible to mast cell-mediated growth suppression (Fig. 5g, h). In normal medium, DRG neurons of mast cell coculture showed no significant difference with DRG neurons of monoculture. This finding supported that the neurotoxic effect of mast cells was induced under an HG environment. We also noticed that DRG neurons showed no significant difference in the direct and indirect coculture with mast cells, indicating that mast cells exerted their suppressing effects mainly through paracrine activities rather than direct cell-cell contacts. Mitochondrial dysfunctions and decline underlie neuronal degeneration in the development of neurodegenerative diseases21. Mitochondrial damage was also seen in neurons cultured in HG medium (Fig. 5i, j). Mast cell coculture further exacerbated HG-induced mitochondrial impairment in DRG neurons. To better characterize the mitochondria morphology, we further performed TEM analysis on DRG neurons isolated from both WT and mast cell-deficient mice. Based on the TEM result, mitochondria of DRG neurons responded to HG stimulation with rounded morphology. Moreover, when cocultured with mast cells in HG medium, mitochondria in DRG neurons exhibited fragmented, swollen morphology and reduction of mitochondrial cristae (Supplementary Fig. 4a). DRG neuronal monoculture from KITwsh/wsh mice also featured impaired mitochondrial structure under HG treatment, but preserved more mitochondrial ridges and morphological integrity (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We next evaluated the effects of mast cells on Schwann cell myelinating capacity. Myelin basic protein (MBP) was used as a marker of myelination. As shown in our results, Schwann cell monoculture from WT mice responded to HG treatment with suppressed myelination potentiation. When cocultured with mast cells in HG medium, Schwann cells showed less MBP expression than their monoculture counterparts. Moreover, Schwann cells isolated from KITwsh/wsh mice appeared to be less affected under HG treatment and preserved more myelinating capacity (Supplementary Fig. 4b). These results suggested that mast cells contributed to axon regrowth retardation and demyelination in HG environment via paracrine signaling.

a TB staining of lumbar 5 DRGs isolated from WT and KitW-sh/W-sh mice. b Double immunostaining of ATF3 (red) and NeuN (green) on DRG sections revealed the injured-state neurons. ATF3, activating transcription factor 3. c Double immunostaining of CD45 (red) and NeuN (green) on DRG sections revealed the myeloid cell-neuron fusion phenomenon (arrows, white). d, e Quantifications of ATF3-positive and CD45-positive neurons related to (b) and (c). N = 6 mice per group. f Schematic diagram of the establishment of DRG monoculture and coculture system. Panel (f) was created in BioRender. Kong, L. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ifr27s0. g, h Detection and analysis of neuron monoculture and mast cell-neuron coculture by calcium phosphate transfection. DRG neurons were transfected with a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing plasmid. N = 6 per group. i, j Double immunostaining of TOMM20 (red) and NeuN (green) in DRG neurons and related quantification. N = 6 per group. All data were expressed as mean ± SD in Fig. 5. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests (d, e) and two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc analysis (h, j).

HG environment impaired mitochondrial activities in mast cells

Immune cell activation is associated with a profound and rapid metabolic reprogramming to meet the increased energy demands for immune responses22,23. Specific metabolic pathways are differentially required for the control of mast cell function. While acutely-activated mast cells rely on increased glycolysis for energy production, MAPK-dependent OXPHOS is required upon longer-term activation16. Given that HG stimulation induced mast cell activation and degranulation, we next explored the effect of the HG environment on the metabolic phenotype of mast cells. A robust decrease of mitochondria quantity was observed in mast cells cultured in an HG environment (Fig. 6a, b). Damaged mitochondria are aberrant sources of intracellular ROS. Therefore, we detected mitochondrial ROS using ROS-sensitive dyes, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) and MitoSOX. The mitochondria-specific probe MitoTracker was also applied to confirm the mitochondrial origin of ROS. Intense red fluorescence of MitoSOX was observed inside mast cells cultured in an HG environment (Fig. 6c, d). Consistently, colocalization of DCF-DA green fluorescence and MitoTracker red fluorescence was robustly increased in mast cells under HG stimulation (Fig. 6e, f). To obtain more information about the activity and metabolism of mitochondria under HG treatment, we evaluated the mitochondrial respiration of mast cells after 24 and 48 h of culture using Seahorse XFe24 analyzer as depicted in Fig. 6g. We found that the increased glucose concentration reduced oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in terms of basal and maximal respiration (Fig. 6h, j), which was indicative of damaged OXPHOS. We also evaluated the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of mast cells upon HG treatment. After 24 and 48 h of culture, a robust increase of ECAR was observed in HG-treated groups, which reflected increased glycolysis level and glycolytic capacity (Fig. 6i, k). Together, these data demonstrated that HG stimulation elevated the level of glycolysis but damaged the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation within mast cells.

a, b Double immunostaining of TPSAB1 (red) and TOMM20 (green) in mast cells and related quantification of TOMM20 staining. N = 6 per group. c, d Detection and analysis of mitochondrial ROS production using the mitochondrial superoxide indicator MitoSOX (red). ROS, reactive oxygen species. N = 6 per group. e, f Detection and analysis of mitochondrial ROS production in mast cells using the mitochondrial probe MitoTracker (red) and ROS-sensitive probe DCF-DA (green). DCF-DA, dichlorofluorescein diacetate. N = 6 per group. g Schematic diagram of OCR and ECAR measurements using a Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer. Panel (g) was created in BioRender. Kong, L. (2025) https://BioRender.com/bdmehyo. h–k Effects of HG exposure (15 and 30 mM) for 24 h and 48 h on the mitochondrial respiration (h and j) and glycolysis (i and k) of mast cells and their key parameters. N = 3 per group. All data were expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests (b, d, and f).

We observed that the mast cells of control groups showed a higher ECAR reading following 2-DG stimulation, indicating that the extracellular acidification was attributed to multiple metabolic processes besides glycolysis. This phenomenon was also consistent to a previous report that highly granulated mast cells could retain ECAR reading after 2-DG injection24. We further found that 2-DG could induce the degranulation of mast cells, which were regranulated at 24 h post 2-DG injection (Supplementary Fig. 5). Therefore, for HG-treated groups, mast cells have undergone repeated bouts of degranulation prior to the glycolytic stress tests, and thus have probably not fully regranulated when 2-DG was given.

HG environment increased mTOR activity and ER stress in mast cells by ERK1/2 cascade

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are important mechanisms of diabetes-related metabolic remodeling25. High glucose in cellular environments can induce ER stress-mitochondrial oxidative stress25. Given that mitochondrial oxidative stress was induced in mast cells upon HG treatment, we next explored the homeostasis in the ER. The increased ER-mitochondria contacts (EMCs) in HG-stimulated mast cells were revealed by TEM (Fig. 7a, b). We then utilized in situ (proximity ligation assay) PLA to detect and quantify ER-mitochondria interaction in mast cells. Two surface proteins, IP3R1 and VDAC1, which are expressed on the ER and mitochondria membranes, respectively, were selected to evaluate the proximity of the two organelles. In this way, we found that HG led to remarkably increased expression of the IP3R1-VDAC1 complex (Fig. 7c, d).

a, b TEM images of ER-mitochondria contacts in mast cells (yellow color depicted the mitochondria; red color depicted the ER) and related quantification. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane. N = 6 per group. c, d In situ PLA monitoring of ER-mitochondria interactions as reflected by genetic modulation of IP3R1-VDAC1 complex and related quantification. The single antibody condition was used as the negative control (NC) of the PLA reaction. PLA, proximity ligation assay; IP3R1, inositol triphosphate receptor 1; VDAC1, voltage-dependent anion channel 1. N = 6 per group. e UMAP plots of DPN and TLA nerve tissues overlaid with GLUT1, GLUT2, GLUT3, and GLUT4 genes. GLUT, glucose transporter. f Double immunostaining of GLUT1 (red) and GLUT3 (green) in mast cells. g, h Relative mRNA expression of GLUT1 and GLUT3 in mast cells, revealed by qPCR. i Double immunostaining of p-ERK1/2 (green) and ERK1/2 (red) in mast cells. ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase. j Western blot (WB) assessment of the expressions of p-ERK1/2, t-ERK1/2, p-mTOR, and t-mTOR in mast cells. mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin. k, l Quantification of P-ERK/T-ERK and P-mTOR/T-mTOR ratio based on the WB results in Fig. 6j. P-ERK refers to the phosphorylated ERK, T-ERK refers to the total ERK, P-mTOR refers to phosphorylated mTOR, and T-mTOR refers to the total mTOR. N = 6 per group. m–o WB assessment and related quantification of GLUT3 expression and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in mast cells. Mast cells were treated with either siRNA-GLUT3 or siRNA-negative control (NC). The protein expression levels of GLUT3 were normalized to GAPDH. N = 3 per group. p, q Relative expression level of CHOP and HSPA5 based on WB results in Fig. 7R. The protein expression levels were normalized to tubulin. CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein; HSPA5, heat-shock-protein family A member 5. N = 6 per group. r Immunoblots of the expression of CHOP and HSPA5 in mast cells. All data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests (b, d, g, h, k, l, p, and q) and one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests (n and o).

Metabolic alterations and ER stress-mitochondrial oxidative stress are strongly associated with the engagement of glucose uptake26. Glucose uptake is efficiently supported by glucose transporters, among which facilitative glucose transporters, including GLUT1, GLUT2, GLUT3, and GLUT4, are indispensable for immune cell activation and inflammatory cytokine production13. Our sequencing data showed that mast cells of DPN patients expressed relatively higher levels of GLUT3 compared to GLUT1 (Fig. 7e). Expressions of GLUT2 and GLUT4 were not detected in DPN patients (Fig. 7e). Immunostaining analysis revealed the strong GLUT3 expression but slight GLUT1 expression in HG-treated mast cells (Fig. 7f). We further validated that the mRNA expression level of GLUT3 was markedly higher than that of GLUT1 in HG-treated mast cells (Fig. 7g, h). Expressions of glucose transporters are modulated by environmental factors, including glucose and oxygen availability22. Therefore, we hypothesized that, upon sensing the HG stimulation in the environment, GLUT3 adapted its expression and mediated increased glucose uptake to dictate intracellular activities of mast cells.

Under the circumstances of ER stress, aberrant hyperactivity of mTOR pathways driven by ERK1/2 cascades, have been reported27. ERK1/2 are the critical components of the MAPK signaling cascade and phosphorylate a diverse range of cytoplasmic and nuclear substrates28. Our single-cell sequencing analysis also indicated that gene expression of DPN mast cells was enriched in the MAPK1 signaling pathway (Fig. 4d). Therefore, we next determined whether an elevation in glucose uptake would induce ERK1/2 cascades in mast cells. Indeed, levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2) were increased in HG-treated mast cells (Fig. 7i, k), accompanied by a substantial rise in p-mTOR levels (Fig. 7j, l). To functionally characterize the role of GLUT3 in HG-induced ERK cascades, GLUT3 siRNA was added into the mast cell culture medium. Immunoblots confirmed the decrease of GLUT3 expression in mast cells following the treatment of GLUT3 siRNA (Fig. 7m, o). Blocking glucose uptake with the GLUT3 siRNA partially reversed the ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 7m, n).

Aberrant mTOR activity leads to the accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins, which subsequently give rise to ER stress29. C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) suppresses the calcium transfer from the ER to mitochondria, thus triggering mitochondrial apoptosis during ER stress30. The molecular chaperone heat shock protein family A member 5 (HSPA5) have multiple functions in relieving ER stress and maintaining cell viability31. Therefore, the two proteins were ideal candidates to indicate for ER stress. Accordingly, we observed that expressions of HSPA5 and CHOP significantly increased in HG-treated mast cells compared with the controls (Fig. 7p-r). Such ER stress phenomenon was alleviated by a specific ERK1/2 antagonist, PD98059, thereby confirming the role of ERK1/2 as the mediator of HG-induced ER stress (Supplementary Fig. 5b–e). PD98059 also protected mast cells against HG-induced degranulation (Supplementary Fig. 5f). Taken together, these findings indicated that, continuous exposure to high glucose led to higher expression of GLUT3, which mediated increased glucose uptake in mast cells. As a result, the activation of ERK1/2/mTOR/ER stress pathway ensued, ultimately aggravating the metabolic dysfunction and degranulation of mast cells.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of DPN is linked with vascular damage, hyperglycemia, hypoxia, and oxidative stress, leading to progressive degeneration of peripheral nerves. Despite the rapid expansion of studies regarding with pathophysiological mechanisms of DPN, the full spectrum of affected cells in DPN and an in-depth understanding of the multicellular responses are still unfolding. Here, we show that the peripheral nerves of DPN patients are featured with robustly increased mast cells in concert with increased infiltration of myeloid leukocytes. By combining the STZ-induced DPN model with genetically determined mast cell deficiency in mice, we find out that activated mast cells contribute to the degenerative changes and inflammatory responses during the progression of DPN (Fig. 8).

Excessive glucose uptake by GLUT3 induces aberrant activation of the ERK-mTOR pathway, which further mediates the ER stress and mitochondrial oxidative stress in mast cells. Dysfunction of mitochondria impairs the OXPHOS process. Mast cells adapt their metabolic profiles, shifting from OXPHOS to glycolysis, to support the robust energy demands of degranulation. Figure 8 was created in BioRender. Kong, L. (2025) https://BioRender.com/qdz158v.

To isolate human DPN nerve tissue, we recruited DPN patients undergoing amputation surgeries for diabetic foot ulcer. Diabetic foot ulcer is the commonest major end-point of diabetic complications and most frequent precursor to amputation32,33. Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) and DPN are the main etiological factors in foot ulceration34. In the pathway to foot ulcer, PVD and DPN may act alone, together, or in combination with other contributory causes, such as decreased mobility and infection susceptibility33. The neuropathic foot ulcer results from the combination of insensitivity, extrinsic factors (e.g., walking barefoot and stepping on a sharp object), and intrinsic factors (development of a callosity and diminished sensation). Tibial nerves are sensorimotor nerves which control the movement and skin sensations to the posterior parts of the feet and lower legs. The formation of diabetic foot ulcer is a sign that damages in tibial nerves have deteriorated severely35. Therefore, we obtained tibial nerve samples for detailed sequencing and morphometric analysis.

Our single-cell atlas of peripheral nerves allowed the detailed understanding of cellular components and cell-specific transcriptional changes in DPN progression. To our knowledge, this is the first single-cell atlas of peripheral nerves from DPN patients to date. Schwann cells and axons are two vital components in peripheral nervous system. Schwann cell degeneration and axon demyelination are major pathological features observed in biopsy samples from DPN patients36. Previous studies have simply focused on the alterations of neural components during DPN progression37. However, nerves contain not only neurons and Schwann cells, but also minority cell types which can sense the injury signal in nerves and orchestrate multicellular remodeling to maintain microenvironment homeostasis. Human nerve bulk-sequencing data have identified that DPN progression is closely associated with inflammatory responses38. Based on scRNA-seq data, we revealed that nerve degeneration in DPN was executed coordinately by immune cells. These data provide a useful resource for understanding the cell-specific nerve transcriptional responses to DPN. Among the nerve-resident immune cells, we observed a robust increase and dysregulated activation of mast cells.

Mast cell is emerging as a pathological factor in the onset and progression of diabetes and related complications39,40. In fact, increased mast cells have also been detected in diabetic nephropathy, wound, white adipose tissue, heart, and vessels, despite the lack of complete understanding of its mechanisms of activation. A previous study reported that an increase in mast cell numbers and degranulation level correlated significantly with tubular interstitial injury40. Topical application of mast cell stabilizers alleviated the local inflammation in diabetic wound and improved wound healing41. Another research reported that infiltrated mast cells are the trigger of small vessel disease and diastolic dysfunction in diabetic mice42. High numbers of mast cells were also observed in the white adipose tissue of type 2 diabetes and exacerbated glucose intolerance by producing inflammatory factors39. Therefore, our research can provide important mechanistic insights into high glucose-induced mast cell activation in diabetes and diabetic complications.

Mast cell-derived mediators and proteases damage the integrity of the extracellular matrix, impede the functions of vascular cells, and interfere with the activity of other immune cells, thus contributing to the pathobiology of diabetic complications43,44. Paclitaxel, a primary chemotherapy agent against diverse solid tumors, has been reported to induce the histamine release of mast cells, thereby causing acute pain and chronic neuropathy45,46. In this regard, antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers are used as premedication of chemotherapy to ameliorate paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy47. Some studies reported that mast cells could be recruited to nerve tissues by aberrant Schwann cells due to the robust release of stem cell factors48,49. In peripheral tissues, mast cells reside near axons and can directly communicate with the peripheral nervous system by rapid degranulation responses or long-term secretion of mediators50,51. In a previous work, single-cell RNA sequencing was performed on the skins of diabetic foot ulcers and demonstrated excessive degranulated mast cells in diabetic skin32. However, the involvement of mast cells in DPN progression remained unclear. Our study confirmed DPN induction resulted in robust expression of inflammatory factors in mast cells, which further led to axonal demyelination and myelin decompaction in mice. Genetic depletion of mast cells significantly reduced the level of neuroinflammation and alleviated the degenerative changes in nerve tissues.

In this study, IL-1β and TNF-ɑ levels in DPN nerves of KITW-sh/W-sh mice were decreased by 1.80 and 1.84 times, respectively, compared with their WT counterparts. This result indicated that mast cells were not the sole cellular source of inflammatory factors in DPN. In fact, a previous article has clarified that macrophages are activated by advanced glycation end products in the pathogenesis of DPN and are polarized to a proinflammatory phenotype expressing TNF-ɑ and iNOS10. They further identify that macrophage-induced local inflammation leads to axonal transport deficits and neuronal atrophy in DPN10. Another study also verified that neutrophils contribute to the neuronal damage in DPN by forming neutrophil extracellular traps and releasing neuroinflammatory mediators under diabetic condition52.

Given that hyperglycemia is the primary event in the onset of DPN, we investigated the response of mast cells toward HG stimulation. We recapitulated the HG environment in DPN by adding 30 mM glucose in cell culture medium. As expected, the HG environment provided a source of chronic stimuli toward mast cells. Histamine, tryptase, and cytokine generation were highly increased, and degranulation was exacerbated in metabolically-activated mast cells. In HG environment, mast cells exacerbated the axon regrowth retardation and mitochondrial impairment in DRG neurons via paracrine signaling. Based on these findings, we proposed that the HG microenvironment in DPN nerve tissue triggered mast cell activation and thus caused the release of histamine, inflammatory factors, and tryptase, finally leading to axon damage.

The functionality of immune cells is empowered by mitochondrial dynamics and modulated by intracellular metabolic pathways53,54,55. A previous study reported the metabolic switch in mast cells during degranulation and regranulation, indicating that release of prestored granules was partially decided by the metabolic phenotype of mast cells56. Consistently, we also noticed that after in vitro culture in HG environment, the level of OXPHOS was downregulated and but the level of glycolysis was elevated, suggesting a switch of metabolic phenotype in mast cells to meet the energy requirements. Impaired mitochondrial structure, disrupted cellular signaling, and increased mitochondrial ROS production were observed. Dysfunctional mitochondria are pathological mediators of diabetic complications, especially in mitochondria-rich organs9. Aberrant metabolic alterations are known as critical contributing factors to axon degeneration21. These findings implicated that high-glucose diabetic milieu evoked immune responses of nerve-resident mast cells by triggering mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic reprogramming.

GLUT is a series of glucose transporter families with specific glucose uptake and glycolysis functions, which further decide the proliferation, differentiation, and functional activities of immune cells57. In this study, GLUT3 was highly expressed by mast cells upon sensing the robust increase in glucose levels. The increased glucose uptake by GLUT3 caused aberrant ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which activated mTOR signaling and induced ER stress (Fig. 8). Furthermore, GLUT3-mediated glucose metabolism preferred glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation to meet the metabolic demands of mast cell activation. This finding is consistent with a previous claim that the increased glycolysis in mast cells results from mTOR activation upon sensing sufficient glucose56.

The most highly studied pathways implicated in DPN pathogenesis include the polyol pathway, hexosamine and PKC pathways, advanced glycation end-products pathway, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) pathway, and insulin pathways4. Given the multiplicity of pathways underlying DPN, our findings further increased the understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms in DPN pathogenesis. As mast cells are multifunctional, the mechanisms of mast cell involvement in DPN are likely to be complicated, which necessitates future work for thorough exploration. Current pharmacological treatments for DPN focus on pain management and are used during the acute exacerbation of pain. The disease-modifying agents, such as alpha-lipoic acid and epalrestat, remain controversial and are not recommended by any guideline37,58. Moreover, these treatments fail to show positive responses in a meaningful number of patients and cause non-specific toxicity to healthy tissues58. Now that we have demonstrated that mast cell metabolic activation in DPN could be mediated by GLUT3-ERK-mTOR cascade, future studies can be designed to develop precise and mast cell-specific therapeutics toward more effective DPN treatment.

Our study has several limitations. First, the pathogenic role of mast cells in the onset of DPN was not demonstrated, and further studies are needed to assess the existence and contribution of mast cells at early stages of DPN. Second, whereas increased mast cells were observed in tibial nerves of DPN patients, the rationale how these cells were recruited to nervous tissue remains unexplored. Third, despite the finding that mast cell depletion halted DPN progression, the potential therapeutic approaches were not further investigated. Mast cell-targeted inhibitors should be developed in future studies so that the findings in this paper can be applied in the clinic.

Methods

Patient selection

This study enrolled 24 subjects at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai, China. Patient demographics were summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Tibial nerves were collected during amputation surgeries in patients suffering from DPN or patients with traumatic limb amputation. Nerve samples isolated from TLA patients were set as the control group. For single-cell RNA sequencing and PCR experiments, tibial nerves from the donor were rapidly frozen on liquid nitrogen in the operating room and transported to a lab to store at − 80 °C refrigerated conditions. For histological experiments, nerve tissue from patients (7 DPN patients, 10 TLA patients) was immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and dehydrated to be embedded for sectioning. This study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (Registration No. ChiCTR2300068077) on March 6, 2023. The Ethics Committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital approved the clinical investigations (Approval number: 2022-KY-200 (K); Trial registration: ChiCTR2300068077), and written informed consents from the patients were obtained prior to participation.

Cell culture

Primary murine mast cells were isolated from bone marrow of mice femurs and cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 4 mM L-glutamine (A2916801, Gibco, USA), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (11140050, Gibco, USA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (111360070, Gibco, USA), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (M3148, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 1 ng/ml recombinant murine interleukin-3 (213-13-10UG, Peprotech, USA) and 20 ng/ml recombinant murine stem cell factor (250-03-100UG, Peprotech, USA). After 4 weeks of culture, mature mast cells were used for subsequent in vitro studies. For metabolic activation, mast cells were treated with a high concentration of glucose (30 mM) for 24 and 48 h to recapitulate the diabetic milieu in DPN. To block the excessive glucose uptake, mast cells were transfected with GLUT3-siRNA (sc-41219, Santa-Cruz, USA) using Lipofectamine 2000 (11668030, Invitrogen, USA) according to the manual.

Primary DRG neurons were derived from L3-L5 DRGs, which were digested in 0.25% collagenase (Collagenase Type 1, LS004194, Worthington, USA) at 37°C for 30 min. Following the termination of digestion and centrifuge procedure, cell pellets were resuspended in neuronal culture media, which included neurobasal media (Gibco, USA), 2% B-27 supplement (Gibco, USA), and 2 mM GlutaMAX™ (Gibco, USA).

For indirect coculture, mast cells were seeded onto the upper chamber of Transwell® coculture plate (3450; Corning) where DRG neurons were cultured in the lower chamber of the plate. For direct coculture, mast cell pellets and DRG neuron pellets were suspended in culture medium together. For HG coculture, 30 mM glucose was added into neuronal culture media. After 4 days of culture, DRG neurons were used for subsequent in vitro studies.

Animal model

All animal experiments were conducted following the policy of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital (Ethical Approval Number: DWLL2023-0547). Adult (aged 10 weeks) male wild-type (C57BL/6) and KitW-sh/W-sh (C57BL/6) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Stock No. 030764). All mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions and kept on in a regular 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle. To construct DPN model, mice were injected with STZ (dissolved in sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.5, S0130, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) intraperitoneally at a dose of 180 mg/kg and fed with Western diet (4.5 kcal/g, 40% of energy from fat and 1.25% cholesterol, D12108C, Research Diets, USA) every day. At the beginning of our in vivo study, a total number of 42 male mice were used in this study, including 6 WT mice treated with saline, 18 WT mice treated with STZ, and 18 KitW-sh/W-sh mice treated with STZ. Mice from different groups were housed and bred separately. STZ intraperitoneal injection led to unexpected lethality in 3 mice. Mice with a nonfasting blood glucose level exceeding 25 mmol/L, measured by tail tip bleeding at 2 w after STZ injection, were used in this study.

Single-cell suspension preparation and single-cell RNA sequencing

Cryopreserved tibial nerves were incubated in a 37 °C waterbath for rapid recovery and washed thrice. We removed much of the epineurium, necrotic foci, hemorrhagic foci, and other fibrous connective tissue in nerve samples. Thereafter, the nerve samples were minced until no visible chunks remained. These procedures were performed as soon as possible to keep the cellular viability. Nerve pieces were then transferred to tubes containing dissociation buffer. Finally, the tissues were made into single-cell suspension using the gentleMACS Dissociator (MiltenyiBiotec). Single-cell RNA sequencing was carried out using Single Cell 3’ Library and Gel Bead Kit V3.1 on the Chromium platform (10X Genomics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were sequenced to a depth of paired-end 150 bp reads using an Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform (performed by CapitalBio Technology, Beijing, China). The 7 human datasets were integrated and then separately analyzed for DPN and TLA clustering and UMAP visualization using the Seurat 4.0 package. Cell types were first annotated using the SingleR (version 1.4.1) R package based on the expression of canonical cell markers and then manually annotated based on the expression of marker genes for endothelial cells, pericytes, smooth muscle cells, Schwann cells, T cells, NK cells, fibroblasts, mast cells, neutrophils, macrophages and B cells59,60.

QRT-PCR experiments

To test and verify the increased mast cell infiltration in DPN, we performed PCR experiments on human tibial nerve tissues and evaluate the gene expression of mast cell markers. The total RNA was extracted from human tibial nerve tissues by Trizol reagent (15596026CN, Invitrogen, USA). To test the GLUT expression of mast cells in response to HG stimulation, we performed PCR experiments on mast cells cultured in vitro. The total RNA was isolated from mast cells to evaluate the gene expression of GLUT1 and GLUT3. The total RNA of different studies was then reversely transcribed into cDNA with the Color Reverse Transcription Kit (with gDNA Remover) (A0010CGQ, EZBioscience, USA) and analyzed by qPCR amplification (Applied Biosystems, USA). The primer sequences of the mast cell marker genes, including KIT, CPA3, MS4A2, CMA1, and TPSAB1, are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Primers of TNFA, IL1B, SLC2A1 (GLUT1), and SLC2A3 (GLUT3) were purchased from Servicebio Technology (China). The relative quantification of gene expression was analyzed with the values of 2-△△Ct, and normalized to the GAPDH expression level. There were 6 samples in each group (n = 6), and all the detections were repeated thrice separately.

Immunohistological and immunocytochemistry (ICC) analysis

Human and murine nerve samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned (6 μm thickness) and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or toluidine blue (TB). For immunofluorescence, the paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, steam-heated and then blocked with 5% serum appropriate to the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Afterwards, primary antibodies were washed off and the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature. Secondary antibodies included goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor® 647 (1:200, ab150115, Abcam), goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor® 647 (1:200, ab150079, Abcam), goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor® 488 (1:200, ab150113, Abcam) and goat anti-mouse Alexa488 (1:500, ab150113, Abcam). Finally, after washing off secondary antibodies, all sections were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, H-1200, Vector Laboratories, USA) and analyzed using a confocal microscope.

For IHC, paraffin-embedded nerve sections were rehydrated and treated with 3% H2O2. Then samples were incubated with primary antibodies overnight and the biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit, 1:500, ab207995, Abcam, USA) for 1.5 h at room temperature and DAB as substrate.

For ICC analysis, mast cells were fixed and permeabilized at room temperature. Then, cell samples were blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 30 min and incubated with primary antibodies overnight. Then, mast cell samples were incubated with above-mentioned secondary antibodies. To visualize the pre-stored granules, mast cells were incubated with 0.2% avidin conjugated with FITC (554057, BD Biosciences, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the nuclei of the cell samples were stained with DAPI solution and observed with a fluorescent microscope. To measure the axon length of DRG neurons, we performed calcium phosphate transfection. The transfection media was prepared with cDNA encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP). DRG neurons were transfected with GFP-expressing plasmid (24402, Addgene, USA).

Primary antibodies included anti-NF200 (rabbit, 1:200, 18934-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-S100 (1:100, 90393S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-NeuN (mouse, 1:250, ab104224, Abcam), anti-TNF-ɑ (rabbit, 1:200, ab183218, Abcam), anti-IL-1β (rabbit, 1:200, ab254360, Abcam), anti-CD45 (mouse, 1:250, Proteintech, 60287-1-Ig), anti-TPSAB1 (rabbit, 1:150, Proteintech, 13343-1-AP), anti-CD68 (rabbit, 1:300, Proteintech, 28058-1-AP), anti-NKG7 (rabbit, 1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, 84835S), anti-MPO (rabbit, 1:50, Cell Signaling Technology, 14569S) and anti-CD3 (rabbit, 1:150, Abcam, ab135372), anti-CD63 (rabbit, 1:200, Proteintech, 25682-1-AP), anti-HDC (rabbit, 1:200, Invitrogen, PA5-102775), anti-GLUT1 (rabbit, 1:100, 73015S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-GLUT3 (rabbit, 1:100, 20403-1-AP, Proteintech), TOMM20 (rabbit, 1:100, 42406S, Cell Signaling Technology).

The intensity and expression level of these measurements were analyzed and calculated by Image J software (version 1.52a). To count the percentage of positive cells, the calculation process was done manually. To measure the intensity of immunosignals and the immunostaining area, the calculation process was done automatically.

Mitochondrial ROS detection

To investigate the generation of mitochondrial ROS, mast cells were first incubated with 200 nM MitoTracker™ Red FM (M22425, Invitrogen, USA) for 30 min at room temperature to label mitochondria. After MitoTracker staining was completed, the MitoTracker staining medium was replaced with fresh Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) buffer. Then, cells were loaded with 5 μM DCF-DA (C2938, Invitrogen, USA) for 30 min at room temperature to detect cellular ROS.

In a separate experiment, mitochondrial ROS imaging was performed using MitoSOX™ (M36008, Invitrogen, USA). Once in the mitochondria, the MitoSOX red reagent is oxidized by superoxide and exhibit bright red fluorescence61. Mast cells were incubated with 500 nM MitoSOX red reagent for 30 min and then imaged in fresh HBSS buffer. In both experiment, quantification of fluorescence signals was performed using confocal microscopy.

Seahorse bioenergetic analysis

Oxygen consumption and extracellular acidification in mast cells were performed using Seahorse XF24 Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, mast cells were plated at 50,000 cells/well on Seahorse XF24 cell culture microplates in high glucose (15 and 30 mM) DMEM/F12 media or normal medium with 5.5 mM glucose for 24 h. OCR was measured by sequentially adding 1 µM oligomycin, 1.5 µM fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP), and 100 nM rotenone plus 1 µM antimycin A (103015-100, Agilent, USA). ECAR was measured following the sequential addition of 10 mM glucose, 1 μM oligomycin, and 100 mM 2-DG (103020-100, Agilent, USA).

TEM analysis

Mast cells were cultured in high-glucose and normal medium as described above. For each group, mast cells were cultured in 6 separate dishes. Nerve tissue samples and cell samples were first fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C overnight. Thereafter, samples were postfixed in 1% osmic acid at 4 °C for 1.5 h. Then, samples were dehydrated and embedded to be cut into sections, which were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and finally imaged using a TEM (Hitachi, Japan).

The distance between the ER and outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) in mast cells was measured by Image J software. ER-OMM apposition with a distance less than 100 nm was considered as an EMC. ER length adjacent to mitochondria in EMCs was measured and normalized by the mitochondria perimeter.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Concentrations of TNF-α and IL-1β in murine sciatic nerves were measured by ELISA kits (MEC1003 and MEC1010, Anogen, Canada) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue homogenates were prepared using bilateral sciatic nerves and assayed using the BCA protein assay kit (P0012, Beyotime, China). Normalization was performed to the analyte concentration to be pg/mg of total protein.

PLA monitoring

To evaluate the proximity and potential interaction between mitochondria and ER, mast cells were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked for the subsequent PLA process. Then, mast cells were incubated with primary antibody pairs, anti-IP3R1 and anti-VDAC1, overnight at 4 °C. The formation of an IP3R1-VDAC1 interaction could generate one fluorescent dot. We set a negative control group in which mast cells were incubated with a single primary antibody. After that, mast cells were incubated with secondary PLA probes for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing thrice, cells were incubated with Duolink ligation mix for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by amplification for 100 min at 37 °C. Antibody hybridizations, proximity ligations, and detection were performed according to the manufacturers’ recommendations (Duo92101, Millipore Sigma, USA). Finally, DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Mast cells were imaged under the fluorescence microscope. Quantification of the PLA signal was performed by counting red fluorescent dots. There were 6 biological replicates (6 wells) for each group. In each well, 6 cells selected from different fields were quantified as technical replicates and generated an average value to represent each biological sample.

Western blot analysis

Mast cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer, and the isolated protein samples were subjected to thorough centrifugation prior to electrophoresis. Thereafter, protein samples were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA), and the PVDF membranes were blocked with goat serum. Then the PVDF membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against ERK1/2 (4695S, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), p-ERK1/2 (9101S, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), mTOR (2972S, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), p-mTOR (2971S, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), CHOP (2895S, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), HSPA5 (3177S, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), GAPDH (10494-1-AP, 1:10000, Proteintech) and Tubulin (14555-1-AP, 1:10000, Proteintech). After that, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies and finally subjected to the addition of enhanced chemiluminescent reagent (Millipore) before visualization. Unprocessed images were provided in this paper (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Statistical analysis

For most experiments, 6 biological samples (N = 6) were quantified, while 6 fields were quantified as technical replicates in each biological replicate. Technical replicates were quantified to generate an average value for each biological sample. For the seahorse test and immunoblotting in Fig. 7m, only 3 biological replicates were performed without technical replicates. The single-cell sequencing data were quantified by 7 biological replicates (4 for DPN and 3 for TLA patients) without technical replicates. The histological analysis for human samples in Figs. 2e–i and 3b was quantified by 17 samples (N = 10 for TLA patients and N = 7 for TLA patients), while 6 fields were quantified as technical replicates in each biological replicate. The PCR analysis in Figs. 1j and 3c, d was quantified using 6 biological samples for each group, with 3 technical replicates for each sample. Data were presented as mean ± SD. We utilized GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software) for statistical analysis. For two-group comparisons, a two-tailed Student’s t test was used. For greater than two-group comparisons, a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s or Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests and two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s or Sidak’s post-hoc analysis were utilized. Differences were regarded as significant at a p-value < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the results of this study are available within the Main Text and Supplementary Information or with the corresponding author on request. The high-throughput datasets of single-cell RNA sequencing have been deposited in NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the accession code GSE266026. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Hur, J., Sullivan, K. A., Callaghan, B. C., Pop-Busui, R. & Feldman, E. L. Identification of factors associated with sural nerve regeneration and degeneration in diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care 36, 4043–4049 (2013).

Selvarajah, D. et al. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: advances in diagnosis and strategies for screening and early intervention. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7, 938–948 (2019).

Xie, Y. K. et al. GPR177 in A-fiber sensory neurons drives diabetic neuropathic pain via WNT-mediated TRPV1 activation. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabh2557 (2022).

Eid, S. A. et al. New perspectives in diabetic neuropathy. Neuron 6273, 00345–00348 (2023).

Yamakawa, I. et al. Inactivation of TNF-α Ameliorates Diabetic Neuropathy in Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 301, E844–E852 (2011).

Vincent, A. M., Calabek, B., Roberts, L. & Feldman, E. L. Biology of diabetic neuropathy. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 115, 591–606 (2013).

Cheng, Y. et al. How inflammation dictates diabetic peripheral neuropathy: An enlightening review. CNS Neurosci Ther. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.14477 (2024).

Feldman, E. L. et al. Diabetic neuropathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 5, 41 (2019).

Forbes, J. M. & Thorburn, D. R. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 14, 291–312 (2018).

Osonoi, S. et al. RAGE activation in macrophages and development of experimental diabetic polyneuropathy. JCI Insight 7, e160555 (2022).

Kratz, M. et al. Metabolic dysfunction drives a mechanistically distinct proinflammatory phenotype in adipose tissue macrophages. Cell Metab. 20, 614–625 (2014).

Handzlik, M. K. et al. Insulin-regulated serine and lipid metabolism drive peripheral neuropathy. Nature 614, 118–124 (2023).

Hochrein, S. M. et al. The glucose transporter GLUT3 controls T helper 17 cell responses through glycolytic-epigenetic reprogramming. Cell Metab. 34, 516–532 (2022).

Nava Lauson, C. B. et al. Linoleic acid potentiates CD8+ T cell metabolic fitness and antitumor immunity. Cell Metab. 35, 633–650 (2023).

Tang, X. et al. Regenerative role of T cells in nerve repair and functional recovery. Front. Immunol. 13, 923152 (2022).

Goretzki, A., Lin, Y. J. & Schülke, S. Immune metabolism in allergies, does it matter?-A review of immune metabolic basics and adaptations associated with the activation of innate immune cells in allergy. Allergy 76, 3314–3331 (2021).

Abraham, S. N. & St John, A. L. Mast cell-orchestrated immunity to pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 440–452 (2010).

Ohmori, S. et al. GATA2 is critical for the maintenance of cellular identity in differentiated mast cells derived from mouse bone marrow. Blood 125, 3306–3315 (2015).

Renthal, W. et al. Transcriptional reprogramming of distinct peripheral sensory neuron subtypes after axonal injury. Neuron 108, 128–144 (2020).

Terashima, T. et al. The fusion of bone-marrow-derived proinsulin-expressing cells with nerve cells underlies diabetic neuropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 12525–12530 (2005).

Traxler, L. et al. Warburg-like metabolic transformation underlies neuronal degeneration in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Metab. 34, 1248–1263 (2022).

Fu, H. et al. The glucose transporter 2 regulates CD8+ T cell function via environment sensing. Nat. Metab. 5, 1969–1985 (2023).

Chi, H. Regulation and function of mTOR signalling in T cell fate decisions. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 325–338 (2012).

Mendoza, R. P., Anderson, C. C., Fudge, D. H., Roede, J. R. & Brown, J. M. Metabolic consequences of IgE- and non-IgE-Mediated mast cell degranulation. J. Immunol. 207, 2637–2648 (2021).

Yuan, M. et al. IP3R1/GRP75/VDAC1 complex mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress-mitochondrial oxidative stress in diabetic atrial remodeling. Redox Biol. 52, 102289 (2022).

Wang, M. & Kaufman, R. J. Protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum as a conduit to human disease. Nature 529, 326–335 (2016).

Panda, D. K. et al. SCF-SKP2 E3 ubiquitin ligase links mTORC1/ER stress/ISR with YAP activation in murine renal cystogenesis. J. Clin. Inves 132, e153943 (2022).

Johnson, G. L. & Lapadat, R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science 298, 1911–1912 (2002).

Costa-Mattioli, M. & Walter, P. The integrated stress response: From mechanism to disease. Science 368, eaat5314 (2020).

Tabas, I. & Ron, D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 184–190 (2011).

Liu, Z. et al. ER chaperone GRP78/BiP translocates to the nucleus under stress and acts as a transcriptional regulator. Proc. Nat Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2303448120 (2023).

Theocharidis, G. et al. Single cell transcriptomic landscape of diabetic foot ulcers. Nat. Commun. 13, 181 (2022).

Sinwar, P. D. The diabetic foot management - recent advance. In J. Surg. 15, 27–30 (2015).

McDermott, K., Fang, M., Boulton, A. J. M., Selvin, E. & Hicks, C. W. Etiology, Epidemiology, and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care 46, 209–221 (2023).

Sarmiento, S., Pierre, J. A. Jr, Dellon, A. L. & Frick, K. D. Tibial nerve decompression for the prevention of the diabetic foot: a cost-utility analysis using Markov model simulations. BMJ Open 9, e024816 (2019).

Guo, J. et al. Blockage of MLKL prevents myelin damage in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Proc. Nat Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2121552119 (2022).

Majd, H. et al. Deriving Schwann cells from hPSCs enables disease modeling and drug discovery for diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Cell Stem Cell 30, 632–647 (2023).

Hur, J. et al. The identification of gene expression profiles associated with progression of human diabetic neuropathy. Brain 134, 3222–3235 (2011).

Liu, J. et al. Genetic deficiency and pharmacological stabilization of mast cells reduce diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Nat. Med. 15, 940–945 (2009).

Zheng, J. M., Yao, G. H., Cheng, Z., Wang, R. & Liu, Z. H. Pathogenic role of mast cells in the development of diabetic nephropathy: a study of patients at different stages of the disease. Diabetologia 55, 801–811 (2012).

Tellechea, A. et al. Topical application of a mast cell stabilizer improves impaired diabetic wound healing. J. Invest. Dermatol. 140, 901–911 (2020).

Guimbal, S. et al. Mast cells are the trigger of small vessel disease and diastolic dysfunction in diabetic obese mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 41, e193–e207 (2021).

Shi, G. P., Bot, I. & Kovanen, P. T. Mast cells in human and experimental cardiometabolic diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 12, 643–658 (2015).

Elieh Ali Komi, D., Shafaghat, F. & Christian, M. Crosstalk between Mast Cells and Adipocytes in physiologic and pathologic conditions. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 58, 388–400 (2020).

Lu, J. et al. Desloratadine ameliorates paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy and hypersensitivity reactions in mice. Acta Pharm. Sin. 45, 2061–2076 (2024).

Rowinsky, E. K. & Donehower, R. C. Paclitaxel (taxol). N. Engl. J. Med. 332, 1004–1014 (1995).

ALMuhizi, F., De Las Vecillas Sanchez, L., Gilbert, L., Copaescu, A. M. & Isabwe, G. A. C. Premedication protocols to prevent hypersensitivity reactions to chemotherapy: A literature review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 62, 534–547 (2022).

Staser, K., Yang, F. C. & Clapp, D. W. Mast cells and the neurofibroma microenvironment. Blood 116, 57–64 (2010).

Yang, F. C. et al. Neurofibromin-deficient Schwann cells secrete a potent migratory stimulus for Nf1+/- mast cells. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1851–1861 (2003).

Alim, M. A. et al. Glutamate triggers the expression of functional ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors in mast cells. Cell Mol. Immunol. 18, 2383–2392 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Nonpeptidergic neurons suppress mast cells via glutamate to maintain skin homeostasis. Cell 184, 2151–2166 (2021).

Thakur, V., Gonzalez, M. A., Parada, M., Martinez, R. D. & Chattopadhyay, M. Role of histone deacetylase inhibitor in diabetic painful neuropathy. Mol. Neurobiol. 61, 2283–2296 (2024).

Buck, M. D. et al. Mitochondrial dynamics controls T cell fate through metabolic programming. Cell 166, 63–76 (2016).

Jha, M. K. et al. Macrophage monocarboxylate transporter 1 promotes peripheral nerve regeneration after injury in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 131, e141964 (2021).

Phong, B., Avery, L., Menk, A. V., Delgoffe, G. M. & Kane, L. P. Cutting edge: Murine mast cells rapidly modulate metabolic pathways essential for distinct effector functions. J. Immunol. 198, 640–644 (2017).

Iskarpatyoti, J. A. et al. Mast cell regranulation requires a metabolic switch involving mTORC1 and a glucose-6-phosphate transporter. Cell Rep. 40, 111346 (2022).

Macintyre, A. N. et al. The glucose transporter Glut1 is selectively essential for CD4 T cell activation and effector function. Cell Metab. 20, 61–72 (2014).

Rafiullah, M. & Siddiqui, K. Pharmacological treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: An update. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 21, 884–900 (2022).

Carr, M. J. et al. Mesenchymal precursor cells in adult nerves contribute to mammalian tissue repair and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 24, 240–256.e9 (2019).

Yadav, A. et al. A cellular taxonomy of the adult human spinal cord. Neuron 111, 328–344 (2023).

Kuznetsov, A. V. et al. Mitochondrial ROS production under cellular stress: comparison of different detection methods. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 400, 2383–2390 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National key R&D Program of China (No. 2021YFC2400801), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82372409 and 824B2072), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (General Program) (No. 2024M762031), and Excellent Youth Cultivation Program of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital (No. ynyq202201). We acknowledge BioRender.com for providing icons of illustrations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q. and C.F. generated the idea, proposed the hypotheses and provided technical support. X.Y. and X.W. conceived the study and carried out most of the experiments. Y.Q., R.Z., and L.K. helped with clinical data and sample collection. X.Y. performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. Y.Q. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Rayaz Malik, Hiroki Mizukami, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, X., Wang, X., Zhang, R. et al. Dysregulated mast cell activation induced by diabetic milieu exacerbates the progression of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in mice. Nat Commun 16, 4170 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59562-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59562-z

This article is cited by

-

Targeted neural stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles loaded with Sinomenine alleviate diabetic peripheral neuropathy via WNT5a/TRPV1 pathway modulation

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2025)

-

Diagnostic value of shear wave elastography for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: comparison between junior radiologists and senior radiologists

BMC Medical Imaging (2025)

-

The role of gut microbiota in neuropathic pain: insights into immune mechanisms

The Journal of Headache and Pain (2025)